Abstract

Reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) is the gold standard for mRNA quantification. Efficient, rapid, and high-throughput mRNA extraction is a prerequisite to ensure PCR sensitivity and precision, particularly for quantification of low-abundance mRNAs, and for large numbers of samples. Many mRNA extraction methods entail meticulous handling of individual samples, and are not well suited for large sample numbers. To achieve simple separation of mRNA-binding matrix and the medium from which mRNA is to be isolated, oligo (dT)20-coated silica beads were used. Simple centrifugation and decanting steps can be used throughout the extraction procedure to separate supernatant fluids from the silica beads. DNase treatment reduced clumping of sedimented beads, thus facilitating bead resuspension and avoiding repeated agitation. DNase treatment also significantly reduced contaminating DNA, increased mRNA purity, and enhanced mRNA PCR readout by ~5-fold. The number of target transcripts per sample aliquot was higher in DNase-treated mRNA than in non-treated mRNA or in total nucleic acids. Thus, use of DNase-treated mRNA increased sensitivity of detection and quantification of low-copy transcripts. In conclusion, we describe here a simple, rapid, and cost-effective method that facilitates convenient extraction of high-quality mRNA by minimizing cumbersome mechanical disruption and pipetting steps.

Keywords: mRNA Extraction, oligo (dT), silica beads, Dnase, reverse trancriptase PCR

Quantification of gene transcripts by reverse-transcription PCR is widely performed by use of total specimen RNA (1, 3). However, if poly(A)+ RNA is used, both sensitivity and accuracy of transcript detection improve since the number of detected copies increases substantially as compared to total RNA (4). This is particularly pertinent to quantification of rare mRNAs.

The most convenient method for mRNA isolation is direct extraction from homogenized specimens by binding of the poly(A) tail of mRNAs to immobilized oligo (dT)n followed by washing and elution steps. Several types of commercial kits for affinity mRNA purification utilize oligo (dT)n attached to microscopic polystyrene beads (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA; Sigma, Atlanta, GA, USA), magnetic beads (Dynal Biotech LLC, Brown Deer, Wisconsin, USA; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA), or cellulose (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). For physical recovery of oligo (dT)n-bound mRNA, these solid supports are collected by centrifugation or magnetic force, and mRNA is eluted at approximately 65°C. Reduction of specimen viscosity prior to oligo (dT) binding by shearing of chromosomal DNA by repeated passage through a needle is a critical step in these methods. For example, Ramalho et al. (2004) used shearing by consecutive use of 18G, 23G, and 26G needles with increasingly narrow lumens to obtain optimum sample viscosity (4).

Binding of the poly(A) RNA is followed by physical separation of the solid support from the sample buffer, either by magnetic force, filtration, or centrifugal sedimentation. Of these methods, centrifugation is the most convenient for large sample numbers. Sediments of the support matrix in these methods usually can easily be re-suspended for subsequent washing steps, but removal of supernatants requires careful and time-consuming aspiration. Thus, standard commercial mRNA extraction methods entail meticulous handling of individual samples, and are not well suited for large sample numbers.

These shortcomings led us to use oligo (dT)20-coated silica beads (Kisker GbR, Steinfurt, Germany) for mRNA extraction. Due to their high density, these beads sediment easily, and simple centrifugation and decanting steps can be used throughout the extraction procedure to separate supernatant fluids from the beads.

For optimization of mRNA extraction with oligo (dT)20 silica beads we used mouse lung tissue. Frozen lungs were homogenized at room temperature by use of disposable tissue grinders (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) in guanidinium thiocyanate-based RNA/DNA stabilization reagent (Roche Applied Science). Per specimen, 100 μl of 10% lung suspension was mixed with 10 μl oligo (dT)20 silica bead suspension (25 mg/ml in dH2O; 1 μm particle size) diluted in 230 μl dilution buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.2 M LiCl, 20 mM EDTA). For mRNA binding, samples were incubated at 72°C for 3 minutes followed by room temperature for 10 minutes. The silica beads were sedimented by centrifugation at 13,000×g for 2 minutes, supernatants removed by decanting, and the beads resuspended in wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.2 M LiCl, 1 mM EDTA) by vigorous vortexing for 2 minutes. The washing step was repeated twice, and mRNA was eluted by resuspension of the beads in 200 μl DEPC-treated ddH2O followed by incubation at 72°C for 7 minutes, centrifugal sedimentation, and removal of the supernatant mRNA.

After centrifugation, it was usually difficult to resuspend the pellet of silica beads. We reasoned that the DNA content of the tissue suspension increased its viscosity, and that a DNA mesh potentially increased the cohesion of the silica beads in the pellet (“sticky pellet”). Real-time PCR for intron sequences of the single-copy porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD) gene confirmed a substantial DNA contamination of the final mRNA eluate (data not shown). In order to remedy this problem without having to use cumbersome mechanical steps for DNA shearing and disruption of the “sticky” silica beads, we examined if DNA removal by DNase treatment of the silica beads improved resuspension. After discarding the supernatant lung suspension following initial sedimentation, we resuspended the silica beads in 100 μl DNase buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 1 M NaCl, 10 mM MnCl2) containing 100 U of RNase-free bovine pancreatic DNase I (Roche Applied Science) and incubated the samples for 15 minutes at room temperature. We found that DNase treatment effectively facilitated silica bead resuspension in the subsequent steps of the mRNA extraction.

To evaluate mRNA yields and purity, 10 mouse lung homogenate samples were used for extraction of total nucleic acids by glass fiber matrix binding (Roche Applied Science), and for mRNA oligo (dT)20 silica bead extraction with or without DNase treatment. For each sample, the total nucleic acid concentration and OD260/OD280 were measured by UV spectroscopy (NanoDrop® ND-1000, NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). The average nucleic acid concentration in the total nucleic acid preparations was 157.58 ng/μl, which was significantly higher than the 48.88 ng/μl of all extracted mRNA preparations (p<0.001, Student’s t-test). The average OD260/OD280 ratio was 1.97 in total nucleic acids, and 2.02 in extracted mRNA (p<0.001), indicating increased purity. Nucelic acid concentrations did not differ significantly for mRNA extracted in the absence or presence of DNase, however the OD260/OD280 ratio was significantly higher in the DNase-treated mRNA than in untreated mRNA (2.03 vs. 1.99; p=0.007), indicating that DNase treatment during mRNA extraction increased the purity of mRNA samples.

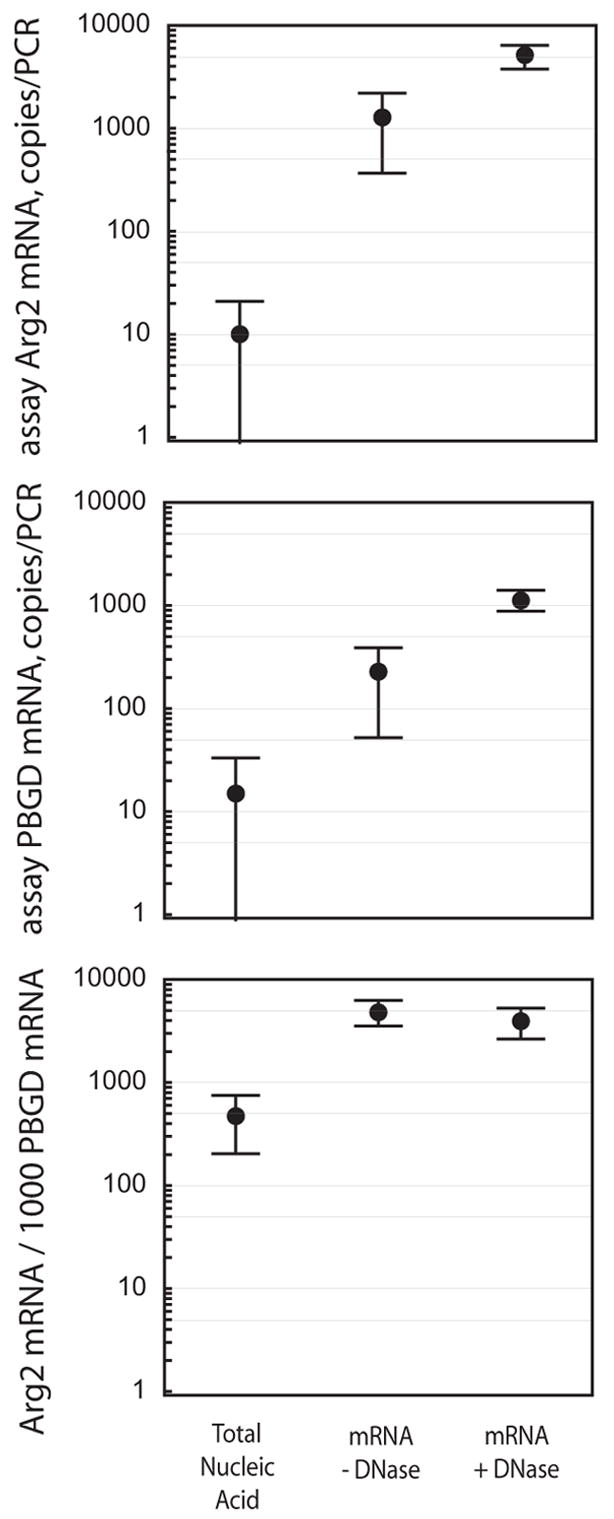

We further evaluated the overall efficiency of mRNA extraction, with and without addition of DNase, by quantifying the amount of Arginase 2 gene and PBGD reference gene mRNAs with an intron-spanning duplex one-step RT-PCR that detects only mRNA, but not genomic DNA (5). For comparison we extracted total nucleic acids, using identical sample and elution volumes. The mean copy numbers of Arginase 2 mRNA per RT-PCR reaction were 13, 1285, and 5095 in 5 μl of total nucleic acids, and in mRNA samples extracted without or with DNase treatment, respectively (Figure 1). Thus, the mRNA concentrations detectable by RT-PCR increased from 11-fold (PBGD, total nucleic acids vs. mRNA without DNase) to 390-fold (Arginase 2, total nucleic acids vs. mRNA with DNase) (p<0.001, Student’s t test). The high variation of the increase in mRNA levels is due to the inherently inaccurate target quantification at the low levels found in total nucleic acid preparations (Poisson sampling error). DNase-treatment increased mRNA recovery by 4- to 5-fold (p<0.001), but did not influence the Arginase 2/1000 PBGD mRNA ratio (p=0.24). In contrast, the ratio in the total nucleic acid preparations (479) differed significantly from the mRNA preparations (4913, 3958; p<0.001), presumably due to the inaccurate target copies determined in total nucleic acids.

Figure 1.

Quantification of Arginase 2 and PBGD mRNAs by duplex one-step RT-qPCR. Total nucleic acids, or poly (A)+ mRNA in absence or presence of DNase were extracted from mouse lungs (n=10) as described. Error bars show the 95% confidence interval.

DNase treatment during mRNA extraction not only reduced “stickyness” of sedimented silica beads, but simultaneously reduced the number of mouse genomes per 5 μl sample volume from more than 105 to less than 30 copies (data not shown), and increased the RNA purity for better PCR quantification. Complete elimination of genomic DNA by longer incubation or use of more DNase (2) would make the extracted mRNA usable in RT-PCRs that do not discriminate between mRNA and genomic DNA target sequence. In conclusion, we describe here a rapid, simple, and low-cost method that facilitates convenient extraction of high-quality mRNA by minimizing cumbersome mechanical disruption and pipetting steps of the protocol.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant AI-47202 from the Public Health Service to B.K.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ho SB, Hyslop A, Albrecht R, Jacobson A, Spencer M, Rothenberger DA, Niehans GA, D’Cunha J, Kratzke RA. Quantification of colorectal cancer micrometastases in lymph nodes by nested and real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis for carcinoembryonic antigen. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10:5777–5784. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai JP, Yang JH, Douglas SD, Wang X, Riedel E, Ho WZ. Quantification of CCR5 mRNA in human lymphocytes and macrophages by real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay. Clinical Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 2003;10:1123–1128. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.6.1123-1128.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moniotte S, Vaerman JL, Kockx MM, Larrouy D, Langin D, Noirhomme P, Balligand JL. Real-time RT-PCR for the detection of beta-adrenoceptor messenger RNAs in small human endomyocardial biopsies. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2001;33:2121–2133. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramalho AS, Beck S, Farinha CM, Clarke LA, Heda GD, Steiner B, Sanz J, Gallati S, Tzetis M. Methods for RNA extraction, cDNA preparation and analysis of CFTR transcripts. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 2004;3:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C, Gao D, Vaglenov A, Kaltenboeck B. One-step duplex reverse transcription PCRs simultaneously quantify analyte and housekeeping gene mRNAs. Biotechniques. 2004;36:508–519. doi: 10.2144/04363RN06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]