Abstract

In this study, we demonstrate that receptor-associated protein 80 (RAP80) interacts with estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) in an agonist-dependent manner. The interaction is specific for ERα as ERβ and several other nuclear receptors tested did not interact with RAP80. Interaction between RAP80 and ERα was supported by mammalian two-hybrid, GST pull-down, and co-immunoprecipitation analyses. The hinge/ligand-binding domain of ERα is sufficient for interaction with RAP80. RAP80 overexpression reduces ERα polyubiquitination, increases the level of ERα protein, and enhances ERα-mediated transactivation. Knockdown of endogenous RAP80 expression by small-interfering RNA (siRNA) reduced ERα protein level and the E2-dependent induction of pS2. In this study, we also demonstrate that RAP80 contains two functional ubiquitin-interaction motifs (UIMs) that are able to bind ubiquitin and to direct monoubiquitination of RAP80. Deletion of these UIMs does not affect the ability of RAP80 to interact with ERα, but eliminates the effects of RAP80 on ERα polyubiquitination, the level of ERα protein, and ERα-mediated transcription. These data indicate that the UIMs in RAP80 are critical for the function of RAP80. Our study identifies ERα as a new RAP80-interacting protein and suggests that RAP80 may be an important modulator of ERα activity.

INTRODUCTION

Estrogens are important for a number of physiological processes that include various reproductive functions and bone metabolism (1–3). The biological actions of estrogens are primarily mediated by two high-affinity nuclear receptors, estrogen receptor α and β (ERα and ERβ) (3,4). In the classical model of nuclear receptor action, ER binding of estrogen releases the receptor from inactive complexes containing heat-shock proteins and immunophilins, followed by dimerization, and binding of ER homodimers to estrogen-response elements (EREs) in the regulatory regions of target genes. Agonist binding induces a conformational change including a repositioning of helix 12 which represents the ligand-inducible activation function AF-2 (3–7). This allows recruitment of co-activator complexes that cause decompactation of chromatin through their histone acetylase activity and transcriptional activation of target genes. In addition to co-activators, a large number of other proteins that interact with ERα and modify its transcriptional activity have been identified (8–12). Moreover, various posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation, sumoylation and ubiquitination, have been reported to modulate ERα activity (9,13–16). Polyubiquitination and degradation of ERα and other nuclear receptors by the ubiquitin–proteasome system is important for regulating nuclear receptor levels and their transcriptional activities (14,16–21). Several components of the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation system, such as PSMC5 (SUG/TRIP1) (22), RSP5/RPF1 (23), UBCH7 (24) and CHIP (16), have been reported to interact with a number of nuclear receptors, including ERα. Recently, sumoylation has been identified as another mechanism that regulates the transcriptional activity of ERα and was shown to involve UBC9, PIAS1 and PIAS3 (9,25). However, our knowledge about the mechanisms by which ubiquitination and sumoylation regulate nuclear receptor level and activity is still far from complete.

We recently described the identification of a novel protein, referred to as receptor-associated protein 80 (RAP80) or ubiquitin interaction motif containing 1 (UIMC1) as approved by the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (26). RAP80 is an acidic nuclear protein of 719 amino acids that contains two Cys-X2-Cys-X11-His-X3-Cys zinc finger-like motifs near the carboxyl terminus. RAP80 is expressed in many tissues, most abundantly in testis. RAP80 was shown to interact with the retinoid-related testis-associated receptor (RTR), also known as germ cell nuclear factor (GCNF) or NR6A1 (26–29). The objective of the current study was to determine the potential role of RAP80 in modulating the activity of other nuclear receptors. Yeast two-hybrid analysis demonstrated that RAP80 interacted with ERα, but not with ERβ or several other nuclear receptors. This interaction required the presence of an agonist, such as estrogen, while antagonists did not induce the interaction. RAP80 was found to contain two putative ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMRAP80) at its amino terminus. UIMs consist of a short-sequence motif of about 20 residues reported to direct (multi)monoubiquitination of proteins that contain this motif. In addition, UIMs have been shown to bind ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like motifs (30–33). UIMs were first identified in the S5a subunit of the 19S proteasome complex (34). UIMs have subsequently been found in a variety of proteins with roles in endocytosis, DNA repair, (de)ubiquitination, replication and transcription (32,33). In this study, we show that the UIMs in RAP80 promote monoubiquitination and are able to bind ubiquitin and, therefore, are functional UIM sequences. Moreover, we demonstrate that RAP80 reduces the polyubiquitination of ERα and increases the level of ERα protein and ERα-mediated transcription. The UIMRAP80 is essential for these effects of RAP80 on ERα. Our study identifies RAP80 as a UIM-containing and ERα-interacting protein and provides evidence for a role of RAP80 as a modulator of ERα-dependent transcriptional activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

The yeast and mammalian two-hybrid vectors pGBKT7, pGBT9, pGADT7, pM, pVP16, and the retroviral vector pLXIN were purchased from BD Biosciences (Palo Alto, CA). The reporter plasmid pFR-Luc, containing 5 copies of the GAL4 upstream-activating sequence (UAS), referred to as (UAS)5-Luc, was obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1(−)Myc-His were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and pCMV–3×FLAG-7.1 from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). PhRL–SV40 encoding the Renilla luciferase was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). To create pGADT7–RAP80ΔN135, the region encoding aa 135 to the carboxyl terminus, was amplified by PCR and the amplified product was inserted into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pGADT7. RAP80ΔN129 and full-length ERα were inserted in-frame into EcoRI and BamHI sites of pM and pVP16, respectively, for use in mammalian two-hybrid assays. The ERE–CAT reporter, in which the CAT reporter is under the control of the natural ERE from the VitA2 promoter, was a gift from Dr Christina Teng (NIEHS). The ERα expression vector pERα and the (ERE)3-Luc reporter were kindly provided by Dr Donald McDonnell (Duke University). The pcDNA3.1–RAP80 was generated by inserting full-length RAP80 into the expression vector pcDNA3.1. pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 was constructed by inserting 3×FLAG–RAP80 into the vector pLXIN. pcDNA3.1–ERα–Myc-His plasmids containing either full-length ERα, ERαΔN180, ERαΔN248 or ERαΔC248 were generated by inserting the corresponding coding regions, obtained by PCR amplification, into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pcDNA3.1(−)Myc-His. The pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 mutants K90R, K112R and K90,112R were generated using a Quickchange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 mutants ΔUIM1, ΔUIM2 and ΔUIM1,2, in which the regions encoding the UIM1, UIM2 or both were deleted, were generated by PCR amplification. The regions up- and down-stream from the UIMs were first amplified by PCR, then ligated at the introduced XhoI sites, and subsequently inserted into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pLXIN–3×FLAG. The pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 deletion mutants, encoding the regions between aa 1-582, 1-524, 1-504, 1-404, 1-304, 1-204,1-122 and 1-78 were generated by PCR amplification and then inserted into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pLXIN–3×FLAG. The pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80ΔC122 mutants A88S, A113S and A88,113S were generated with a Quickchange site-directed mutagenesis kit. PEGFP–UIM1,2 was constructed by inserting the UIMs of RAP80 into EcoRI and BamHI sites of pEGFP-C1. pGEX–UIM1,2 was constructed by inserting the UIMs of RAP80 into BamHI and EcoRI sites of pGEX–5x-3. pCMV–HA–Ub, encoding HA–ubiquitin, and pcDNA3–HA–Nedd8 were gifts from Dr Yue Xiong (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC).

Yeast two-hybrid screening

Briefly, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Y187 (MATα) were transformed with pGADT7–RAP80 (FL) or pGADT7ΔN129 plasmid DNA. pGBT9 plasmid DNAs, encoding the ligand-binding domain or the full-length coding region of various nuclear receptors, were provided by Dr Michael Albers (PheneX-Pharmaceuticals, Heidelberg). pGBT9 plasmids were transformed into S. cerevisiae strain AH109(MATa). After mating, double transformants were selected in minimal Synthetic Dropout medium (SD-Trp-Leu). The transformants were then grown in SD-Leu-Trp-His containing 50 µM 4-methylumbelliferyl α-d-galactopyranoside (4-MuX) (Sigma) in the presence or absence of corresponding ligand. The mixture was incubated for 48 h and fluorescence measured (excitation 360 nm, emission 465 nm wavelength). pGBKT7–p53, encoding GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DBD)–p53, and pGADT7–TD1-1, encoding the GAL4-activation domain fused to the SV40 large T antigen, were used as a positive control in yeast two-hybrid analysis.

GST pull-down assay

E. coli BL21 cells (Stratagene) transformed with pGEX or pGEX–RAP80ΔN110 plasmid DNA were grown at 37°C to mid-log phase. Synthesis of GST or GST fusion protein was then induced by the addition of isopropylthiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; 0.5 mM final concentration) at 37°C. After 4 h of incubation, cells were collected, resuspended in BugBuster protein extraction reagent (Novagen, Madison, WI) and processed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cellular extracts were then centrifuged at 15 000 × g, and the supernatants containing the soluble GST proteins were collected. Equal amounts of GST–RAP80ΔN110 protein or GST protein were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads and washed in phosphate-buffered saline. [35S]-methionine-labeled ERα and its deletion mutants were generated using the TNT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation system (Promega). The GST- and GST–RAP80ΔN110-bound beads were then incubated with [35S]-methionine-labeled ERα in 0.5 ml binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 100 mM KCl, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF) in the presence or absence of 1 µM E2. After 1 h incubation at room temperature, beads were washed five times in binding buffer and boiled in 15 µl 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Solubilized proteins were separated by 4–12% SDS-PAGE and the radiolabeled proteins visualized by autoradiography. To analyze ubiquitin binding, 500 ng of a mixture of polyubiquitin chains (Ub2-7) (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA) were incubated with purified GST or GST–UIMRAP80 protein. GST protein complexes were isolated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads and examined by western blot analysis with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (Covance).

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

HeLa cells were transiently transfected with pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 (full-length or mutant) and pcDNA3.1–ERα–Myc-His or pERα, as indicated, using Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested and lysed for 1 h in NP40 lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, 50 mM NaF, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) containing protease inhibitor cocktails I and II (Sigma). The cell lysates were centrifuged at 14 000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatants were then incubated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity resin overnight to isolate FLAG–RAP80 protein complexes. The resin was washed three times with lysis buffer. The bound protein complexes were then solubilized in sample buffer and analyzed by western blot analysis using anti-ERα (Santa Cruz) and anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma) antibodies.

Ubiquitination assay

HeLa cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1–ERα–Myc-His, pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 or pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80ΔUIM1,2 and pCMV–HA–Ub. Forty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with 25 µM MG132 or ethanol for 4 h. Cells were then harvested and lysed for 1 h in modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl2, 5 mM EDTA, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40, 0.3% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide and 0.1% SDS) containing protease inhibitor cocktails. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 14 000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatants were incubated with anti-ERα antibody and protein-G agarose (Sigma) overnight to pull down ERα protein complexes. The agarose was then washed three times with lysis buffer. The bound proteins were solubilized in sample buffer and analyzed by western blot analysis using anti-HA (Sigma) and anti-ERα antibodies.

Reporter gene assay

CHO and MCF-7 cells were maintained in phenol red-free F12 or RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (Sigma). Cells were transfected using Fugene 6 transfection reagent with the reporter plasmids pERE–CAT or (ERE)3-Luc, RAP80 and ERα expression vectors, and the internal standard β-galactosidase expression vector or phRL–SV40, as indicated. Five hours after transfection, the medium was replaced and 16 h later agonists or antagonists (Sigma) were added. After an additional 24 h incubation, cells were harvested in passive lysis buffer (Promega) and the level of luciferase or CAT protein measured using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega) or CAT-ELISA kit (Roche). All analyses were performed in triplicate.

RAP80 knockdown

MCF-7 cells were transfected with scrambled or RAP80 SMARTpool siRNA reagent (Dharmacon) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were maintained in phenol red-free RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (Sigma) for 48 h, followed by a 24 h treatment with E2. Cells were then collected, protein lysates prepared and examined by western blot analysis using antibodies against RAP80 (Bethyl, TX), pS2 (Santa Cruz), ERα and actin.

RESULTS

Identification of ERα as a new RAP80-interacting protein

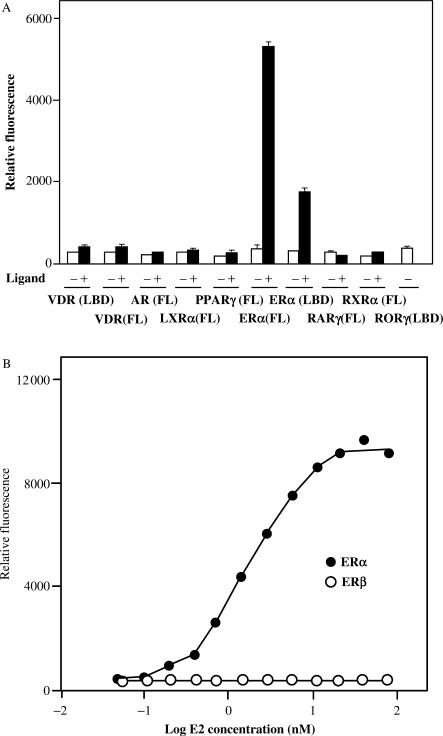

Earlier, we demonstrated that the nuclear protein RAP80 interacts with and modulates the activity of the nuclear orphan receptor RTR/GCNF (26). To determine whether RAP80 was able to interact with other nuclear receptors, we performed yeast two-hybrid analysis using RAP80 as prey and several full-length nuclear receptors or their ligand-binding domains as bait. The yeast strain AH109(MATa) was transformed with pGBT9 plasmids encoding various nuclear receptors and then mated with Y187(MATα) containing pGADT7–RAP80ΔN110. The potential interactions between RAP80 and nuclear receptors were analyzed in the presence or absence of corresponding ligand. This analysis identified ERα as a new RAP80-binding partner and demonstrated that this interaction required the presence of the ERα agonist 17β-estradiol (E2) (Figure 1A). In the presence of E2, RAP80 was able to interact with both full-length ERα and the ligand binding domain of (ERα(LBD)) suggesting that the amino terminus, including the DNA-binding domain (DBD), is not an absolute requirement for the interaction. RAP80 did not show any substantial interaction with the vitamin D receptor (VDR), androgen receptor (AR), liver X receptor α (LXRα), retinoid X receptor α (RXRα), peroxisome proliferator receptor γ (PPARγ), or retinoic acid receptor γ (RARγ) either in the presence or absence of corresponding ligand. The RORγ receptor, which appears to be constitutively active, also did not interact with RAP80.

Figure 1.

RAP80 interacts selectively with ERα. The interaction of RAP80 with different nuclear receptors was analyzed by yeast two-hybrid analysis as described in Materials and Methods. RAP80 was used as bait and several full-length (FL) nuclear receptors or their LBD were used as prey. (A) The interaction of RAP80 with different nuclear receptors was analyzed in the presence (+) or absence (−) of corresponding agonist. The following agonists were used: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (100 nM) for VDR; dihydrotestosterone (100 nM) for AR; T0901317 (1 µM) for LXRα; GW845 (100 nM) for PPARγ; 17β-estradiol (100 nM) for ERα(FL) and ERα(LBD); the RXR-panagonist SR11217 (1 µM); retinoic acid (1 µM) for RARγ. (B) Interaction of ERα(FL) and ERβ(FL) with RAP80 as a function of the estradiol concentration.

As shown in Figure 1B, the interaction of RAP80 with full-length ERα was dependent on the concentration of E2. A concentration as low as 0.2 nM E2 was able to induce the interaction between RAP80 and ERα. The EC50 was calculated to be 1.9 nM E2. RAP80 did not interact with full-length ERβ (Figure 1B) or ERβ(LBD) (not shown) either in the presence or absence of E2. These observations indicate that the interaction of RAP80 with nuclear receptors is highly selective for ERα and is ligand dependent.

Mammalian two-hybrid analysis

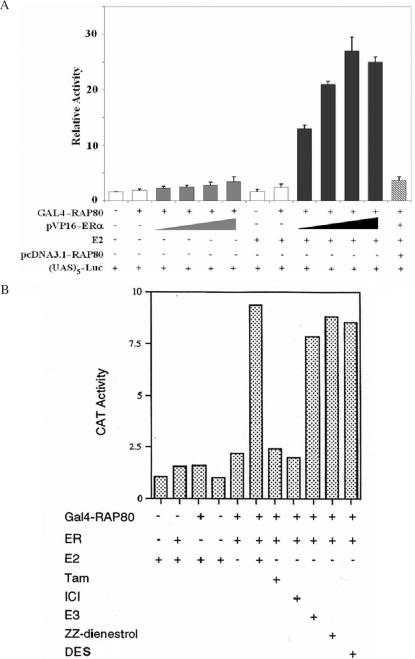

The interaction of RAP80 with ERα was confirmed by mammalian two-hybrid analysis. CHO cells were co-transfected with (UAS)5-Luc reporter, pM–RAP80 and increasing amounts of pVP16–ERα plasmid DNA. As shown in Figure 2A, expression of GAL4(DBD)–RAP80 alone did not enhance transcriptional activation of the (UAS)5-Luc reporter. Co-expression of GAL4(DBD)–RAP80 with pVP16–ERα only slightly increased reporter activity, while addition of E2 greatly induced this reporter activity. Co-transfection with the expression plasmid pcDNA3.1–RAP80 totally abrogated this induction due to competition of RAP80 with GAL4(DBD)–RAP80ΔN129 for ERα binding. These observations support our conclusion that RAP80 interacts with ERα in an E2-dependent manner.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the interaction between RAP80 and ERα by mammalian two-hybrid analysis. (A) CHO cells were co-transfected with (UAS)5-Luc reporter, pM–RAP80, increasing amounts of pVP16–ERα and pcDNA3.1–RAP80 as indicated. Sixteen hours later cells were treated with 100 nM E2 or vehicle. Cells were assayed for reporter activity 24 h after the addition of E2. The relative Luc activity was calculated and plotted. (B) Agonists but not antagonists induce interaction between RAP80 and ERα. CHO cells were co-transfected with pM–RAP80ΔN130, pVP16–ERα and pS5–CAT reporter. Cells were treated with different agonists or antagonists (1 µM) as indicated. Cells were assayed for the reporter activity 24 h after transfection. Ligands used: E2, 17β-estradiol; Tam, tamoxifen; ICI, ICI 182,780; E3, estriol; ZZ-dienestrol; DES, diethylstilbestrol.

We next compared the effect of several ER agonists and antagonists on the interaction of RAP80 with ERα. CHO cells were co-transfected with pM–RAP80ΔN129, pVP16–ERα, and the pS5–CAT reporter plasmid containing five tandem GAL4-binding elements. Sixteen hours later cells were treated with various (ant)agonists. As shown in Figure 2B, all agonists tested, E2, estriol (E3) and diethylstilbestrol (DES), induced the interaction of ERα with RAP80. The weak agonist ZZ-dienestrol also induced the interaction; however, treatment with the antagonists tamoxifen (Tam) and ICI 182,780 (ICI) did not promote the interaction between ERα and RAP80. These results indicate that the interaction of RAP80 with ERα is dependent on the presence of an ERα agonist. Thus, only RAP80 interacts with a transcriptionally active form of ERα.

Co-immunoprecipitation and GST pull-down analysis

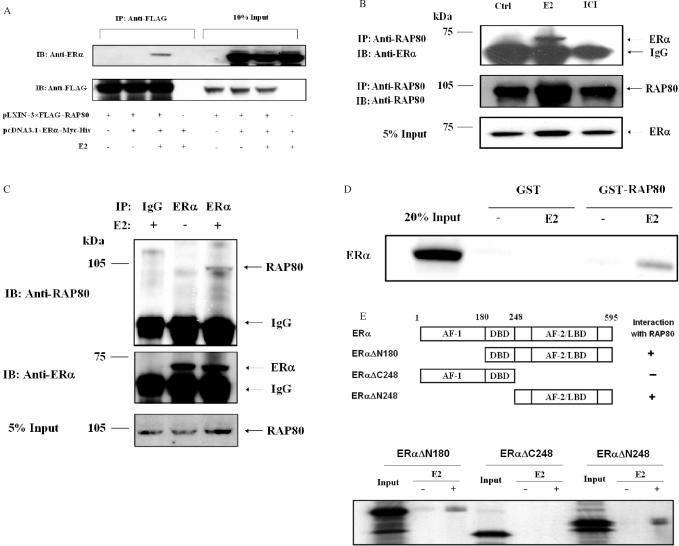

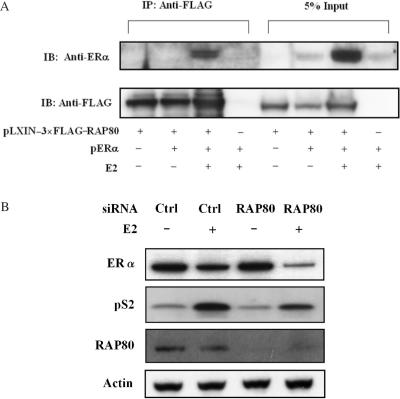

To investigate this interaction further, we performed co-immunoprecipitation analysis. HeLa cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3.1–ERα–Myc-His and pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 expression plasmids, treated with 100 nM E2 or ethanol (vehicle) before cells were harvested and cell lysates prepared. Part of the cell lysates was used directly for western blot analysis while the remaining was incubated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity resin to isolate FLAG–RAP80 protein complexes. As shown in Figure 3A, ERα was immunoprecipitated with FLAG–RAP80 only when E2 was present. These observations are in agreement with the conclusion that RAP80 and ERα interact with each other in an agonist-dependent manner.

Figure 3.

Analysis of the interaction between RAP80 and ERα by co-immunoprecipitation and GST pull-down assays. (A) Co-immunoprecipitation analysis. HeLa cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1–ERα–Myc-His and pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 expression plasmids (1 μg each) and treated with 100 nM E2 or ethanol as indicated. After 24 h, cell lysates were prepared and FLAG–RAP80 protein complexes were isolated using anti-FLAG M2 agarose affinity resin. Proteins in the total cellular lysates and immunoprecipitated (IP) proteins were examined by western blot analysis with anti-FLAG M2 and anti-ERα antibodies. Western blot analysis of IP proteins is shown in the left panel and that of 10% of cell lysates in the right panel. (B) Interaction between endogenous RAP80 and ERα. MCF-7 cells were grown in phenol-red-free medium with 10% charcoal-stripped serum for 2 days and subsequently treated with or without 100 nM E2 or 1 μM ICI 182,780. After 3 h incubation, cells were collected and nuclear lysates prepared. RAP80 protein complexes were immunoprecipitated with an anti-RAP80 antibody and examined by western blot analysis with anti-RAP80 and anti-ERα antibodies. Lower panel shows input ERα. (C) MCF-7 cells were grown and treated with 100 nM E2 as described under (B) before cell lysates were prepared. One part of the lysates was analyzed by western blot analysis using an anti-RAP80 antibody (input RAP80). The remaining lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-ERα antibody or control rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz). The immunoprecipitated ERα protein complexes were then examined by western analysis with anti-RAP80 and anti-ERα antibodies. (D) GST pull-down assay. GST and GST–RAP80Δ110 fusion protein were bound to glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads and then incubated with [35S]-methionine radiolabeled ERα in the presence or absence of 1 μM E2. After 1 h incubation, beads were washed extensively and bound proteins solubilized. Radiolabeled proteins were analyzed by PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. Lane 1: 20% input of radiolabeled ERα. (E) GST pull-down assays were carried out as under (C) using three ERα deletion mutants, ERαΔN248, ERαΔN180 and ERαΔC248.

We next examined whether E2 was able to induce the interaction between endogenous ERα and RAP80. MCF-7 cells were treated with or without E2 or ICI 182,780 for 3 h before nuclear lysates were prepared. RAP80 protein complexes were then immunoprecipitated using an anti-RAP80 antibody and the immunoprecipitated RAP80 protein complexes were examined by western blot analysis with an anti-ERα antibody. Figure 3B shows that endogenous ERα and RAP80 interact with each other. ERα was found in complex with RAP80 only in the presence of E2. The association between ERα and RAP80 was confirmed by analysis of ERα protein complexes immunoprecipitated with an anti-ERα antibody (Figure 3C).

We next examined the interaction of RAP80 with ERα by in vitro pull-down analysis using purified GST–RAP80ΔN110 fusion protein and [35S]-labeled full-length ERα. This analysis showed little interaction between RAP80 and ERα in the absence of E2 (Figure 3D); however, significant binding of ERα to RAP80 was observed in the presence of E2. GST alone did not bind ERα either in the presence or absence of E2. To examine which region of ERα was required for this interaction with RAP80, GST pull-down analysis was performed with three ERα deletion mutants, ERαΔN248, ERαΔN180 and ERαΔC248. As shown in Figure 3E, in the presence of E2, RAP80 was able to bind ERαΔN180 and ERαΔN248, but not ERαΔC248. These results demonstrate that the amino terminus of ERα is unable to bind RAP80 and that the LBD of ERα is required and sufficient for interaction with RAP80. In addition, these observations suggest that RAP80 physically interacts with ERα.

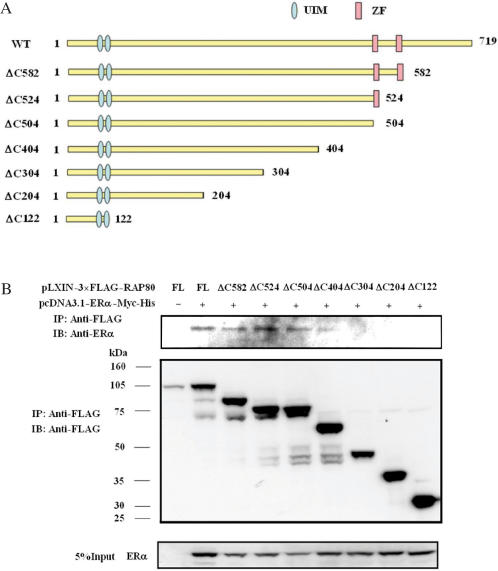

Effect of various deletions in RAP80 on its interaction with ERα

RAP80 contains two putative zinc finger-like motifs at its carboxyl terminus, between aa 505 and 582. To determine which region of RAP80 was important for its interaction with ERα, we constructed a series of carboxyl-terminal deletion mutants (Figure 4A) and examined their ability to interact with ERα by co-immunoprecipitation analysis (Figure 4B). The results demonstrated that carboxyl-terminal deletions up to aa 504 had little effect on the ability of RAP80 to bind ERα, while RAP80ΔC404 was still able to co-immunoprecipitate ERα but less efficiently. In contrast, RAP80ΔC304 and likewise the more severe deletion mutants RAP80ΔC204 and RAP80ΔC122 were unable to interact with ERα. These observations indicate that the region of RAP80 between aa 304 and 404 is critical for the interaction with ERα and that the carboxyl-terminal zinc finger-like motifs are not required. Although several amino-terminal deletions of RAP80 were constructed, none of amino-truncated proteins were expressed in cells. This might be due to improper folding of these mutants and their rapid degradation by the proteasome system.

Figure 4.

Effect of C-terminal deletions on the interaction of RAP80 with ERα. (A) Schematic of RAP80 deletion mutants. UIM and ZF indicate the two ubiquitin-interacting and zinc fingerlike motifs, respectively. (B) HeLa cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3.1–ERα–Myc-His and various pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 plasmids as shown in (A). Cells were treated with E2 (0.1 μM) for 24 h before cell lysates were prepared and FLAG–RAP80 protein complexes isolated using anti-FLAG M2 agarose affinity resin. Proteins in the cellular lysates and immunoprecipitated (IP) proteins were examined by western blot analysis with anti-FLAG M2 and anti-ERα antibodies.

Effect of RAP80 on ERα-mediated transcriptional activation

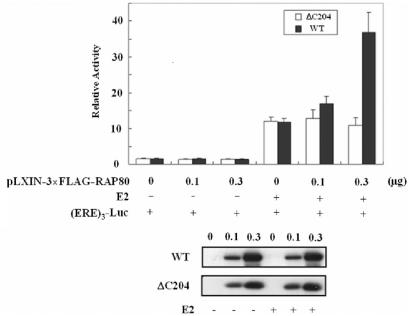

To examine the functional significance of the RAP80–ERα interaction, we determined whether RAP80 had any effect on the transcriptional activity of endogenous ERα. MCF–7 cells were co-transfected with an (ERE)3-Luc reporter and different amounts of RAP80 expression vector, and then treated with or without E2. As demonstrated in Figure 5, RAP80 increased E2-induced transcriptional activation by endogenous ERα. In contrast to full-length RAP80, the deletion mutant RAP80ΔC204, which does not interact with ERα, had no effect on ERα transcriptional activity. An increase in ERα-mediated transactivation was also observed in CHO cells transfected with an ERE–CAT reporter plasmid, and ERα and/or RAP80 expression plasmids (Figure S1A). E2 induced reporter activity in cells transfected with the ERα expression vector, this activation was further increased by 3-fold in cells co-transfected with the RAP80 expression vector. To determine whether this increase was specific for ERα-mediated transactivation or whether RAP80 affected the general transcriptional machinery, the effect of RAP80 on RORE-dependent transcriptional activation by RORγ, a nuclear receptor that does not interact with RAP80, was examined. Figure S1B shows that RAP80 had no effect on RORγ-mediated transactivation.

Figure 5.

Effect of RAP80 on ERα-mediated transcriptional activation. RAP80 increased transcriptional activation by endogeneous ERα. MCF-7 cells were transfected with different amounts of (ERE)3-Luc, pLXIN–3×FLAG-RAP80 or pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80ΔC204 as indicated. Cells were treated with 100 nM E2 or ethanol for 24 h. Cells were then collected and assayed for luciferase activity. RAP80 protein levels were examined by western blot analysis with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (lower panel).

RAP80 expression affects ERα protein levels

To examine whether RAP80 had any effect on the level of ERα protein, HeLa cells were transfected with the expression vector pERα in the presence or absence of pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80. As shown in Figure 6A, the level of ERα protein was very low in HeLa cells transfected with pERα only. In cells co-expressing RAP80 and ERα, the level of total ERα protein was greatly enhanced but only in cells treated with E2. Similar results were obtained with ERα protein co-immunoprecipitated by FLAG–RAP80. These observations suggest that expression of RAP80 enhances the level of ERα protein and that this increase is dependent on the presence of an agonist. This enhancement in ERα protein was not due to an increase in the levels of ERα mRNA by RAP80 since levels of ERα mRNA were very similar between MCF-7 and MCF-7–RAP80 (Figure S2).

Figure 6.

RAP80 expression increases the level of ERα protein. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with 2 μg pERα and 1 μg pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 plasmid DNA. The cells were treated with 100 nM E2 or ethanol for 24 h before cell lysates were prepared and FLAG–RAP80 protein complexes isolated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity resin. The isolated complexes were examined by western blot analysis using anti-FLAG M2 and anti-ERα antibodies. About 5% of the cell lysates were used for direct Western blot analysis. (B) Effect of RAP80 knockdown by RAP80 siRNA on the expression of ERα protein and pS2 induction in MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells transfected with RAP80 or scrambled siRNAs, were grown in phenol-red-free medium with 10% charcoal-stripped serum for 2 days, and subsequently treated for 24 h with or without 100 nM E2. Cell lysates were prepared and examined by western blot analysis with antibodies against ERα, pS2, RAP80, and actin.

We next examined the effect of RAP80 knockdown by RAP80 small-interfering RNA (siRNA) on endogenous ERα protein in MCF-7 cells (Figure 6B). As reported earlier (31,35), treatment with E2 reduced ERα levels (compare lanes 1 and 2), this reduction was more pronounced in cells in which RAP80 was down-regulated (compare lanes 2 and 4). Little difference in ERα levels was observed between untreated cells (lanes 1 and 3). These data are in agreement with our conclusion that RAP80 enhances the level of ERα protein. To analyze the effect of RAP80 knockdown on the transcriptional activity of ERα, we examined its effect on the induction of the ERα target gene pS2. As shown in Figure 6B, the induction of pS2 protein was significantly less in cells in which RAP80 expression was reduced in agreement with our observations that increased RAP80 expression enhances ERα activity.

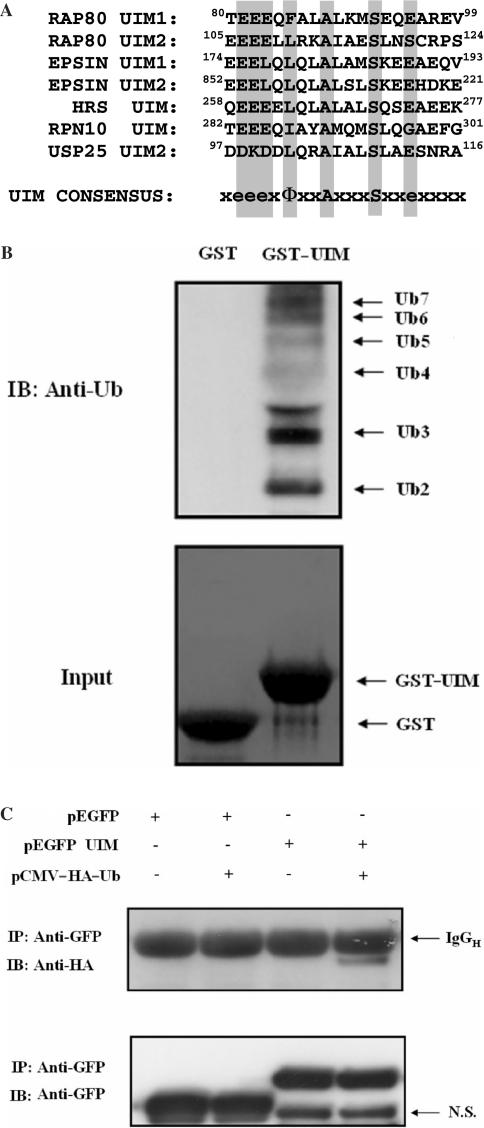

RAP80 contains two functional ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs)

A more extensive analysis of the RAP80 sequence showed that, in addition to the two zinc finger motifs, RAP80 contained two putative ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs) at its amino terminus of RAP80 between aa 79-96 and 104-121, respectively. These UIMs (UIMRAP80) exhibit high homology with the consensus UIM (Figure 7A). UIMs have been reported to bind ubiquitin and to direct (multi)monoubiquitination of proteins that contain them (31,35). Before investigating the role of UIMRAP80 in the interaction of RAP80 with ERα, we examined whether these putative UIMs were functional by determining their ability to bind ubiquitin. As shown in Figure 7B (lane 2), UIMRAP80 was able to bind Ub2-7. To determine whether UIMRAP80 could direct monoubiquitination of proteins that contain this sequence, we analyzed the level of ubiquitination of EGFP and a EGFP–UIMRAP80 chimeric fusion protein in HeLa cells transfected with or without pCMV–HA–Ub, encoding HA-tagged ubiquitin. As shown in Figure 7C, EGFP–UIMRAP80 was ubiquitinated in HeLa cells only when HA–Ub was co-expressed. EGFP was not ubiquitinated either in the presence or absence of HA–Ub expression. These observations suggest that UIMRAP80 is able to direct ubiquitination and, therefore, behaves as a functional UIM.

Figure 7.

RAP80 contains two functional ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs). (A) Sequence comparison of the UIM1 and UIM2 of RAP80 with those of epsin, hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (HGS), the proteasome subunit PSMD4, the ubiquitin-specific peptidase 25 (USP25) and the consensus UIM sequence (Φ is a hydrophobic residue, e is a negatively charged residue and x is any amino acid). (B) UIMRAP80 is able to bind ubiquitin. GST (lane 1) or a GST–UIMRAP80 fusion protein (lane 2) was bound to glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads and then incubated with 500 ng of purified Ub2-7. After 1 h incubation, beads were washed extensively and bound proteins solubilized. Bound proteins were examined by western blot analysis with anti-Ub antibody (upper panel). The input for GST and GST–UIMRAP80 was also shown (lower panel). (C) UIMRAP80 promotes monoubiquitination of EGFP–UIMRAP80. pEGFP or pEGFP–UIMRAP80 was transfected in HeLa cells with or without pCMV–HA–Ub. Forty-eight hours later, the EGFP proteins were isolated with anti-GFP antibody. The proteins were separated with SDS-PAGE and blotted with anti-HA (upper panel) and anti-GFP (lower panel) antibodies respectively. The IgGH and a non-specific band (NS) are indicated.

Role of UIMs on RAP80 ubiquitination

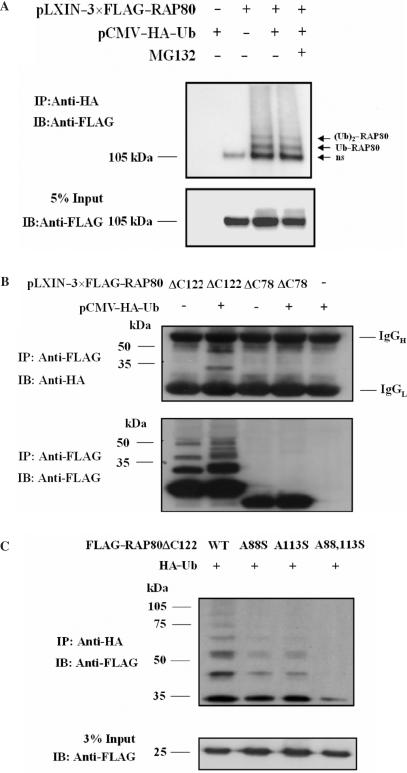

UIM-containing proteins have been reported to become (multi)monoubiquitinated (31,36). To determine whether RAP80 was subject to ubiquitination, we examined the ubiquitination of RAP80 in HEK293 cells treated with and without the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Two major ubiquitinated RAP80 proteins migrating at about 120 and 135 kD and referred to as Ub–RAP80 and (Ub)2–RAP80, were detected (Figure 8A). Previous studies have shown that treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 results in an accumulation of cellular polyubiquitinated proteins that are otherwise rapidly degraded by the proteasome system, whereas MG132 has little effect on monoubiquitinated proteins (21,31,32,37,38). Our data show that MG132 treatment had little effect on RAP80 ubiquitination (Figure 8A) suggesting that RAP80 itself is not polyubiquitinated to a great extent or rapidly degraded by the proteasome. Therefore, the two ubiquitinated RAP80 proteins likely represent RAP80 conjugated to one or two monoubiquitins. The effect of Nedd8, a ubiquitin homolog, was analyzed to further examine the specificity of the ubiquitination of RAP80. These data showed that RAP80 was not neddylated (not shown).

Figure 8.

Role of UIMRAP80 in RAP80 ubiquitination. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80, pCMV–HA–Ub as indicated. After 48 h incubation, cells were treated with or without 25 µM of MG132 for 4 h before cell lysates were prepared. Ubiquitinated proteins were isolated with anti-HA antibody and examined by western blot analysis with anti-FLAG antibody. The input RAP80 is shown in the lower panel. ‘ns’ indicates nonspecific pull-down. (B) UIMRAP80 promotes the ubiquitination of the amino terminus of RAP80. HeLa cells were transfected with pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80ΔC78 or pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80Δ122 with or without pCMV–HA–Ub. Forty-eight hours later, FLAG–RAP80 was isolated with FLAG M2 resin and examined by western blot analysis with anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies. Non-specific staining of IgG is indicated on the right. (C) HEK293 cells were transfected with wild type or mutant pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80ΔC122 and pCMV–HA–Ub as indicated. Cells were treated and processed as described under A.

The UIMs in RAP80 contain two lysine residues (K90 and K112) that are potential ubiquitination sites. To determine whether these sites are important for the multi-ubiquitination of RAP80, the effect of point mutations in these residues on RAP80 multi-ubiquitination was examined. None of the lysine mutants, K90R, K112R, or the double mutant K90,112R, affected the degree of ubiquitination of RAP80 suggesting that K90 and K112 are not substrates of monoubiquitination (Figure S3). Further evidence for the role of UIMRAP80 in the monoubiquitination of RAP80 came from experiments analyzing the ubiquitination of the amino terminus of RAP80. RAP80ΔC122, containing the amino terminus including UIMRAP80, was ubiquitinated whereas RAP80ΔC78, lacking the UIMRAP80, was not suggesting that the UIM is required for RAP80 ubiquitination (Figure 8B). In the absence of exogenous HA–ubiquitin, the anti-FLAG antibody recognized several bands likely representing multi-ubiquitinated RAP80ΔC122 conjugated with endogenous ubiquitin. No such bands were observed with RAP80ΔC78.

A88 and A113 are highly conserved among UIMs of different proteins (Figure 7A), and have been reported to be important for UIM function (39). We, therefore, examined the effect of the A88S, A113S and the A88,113S double mutation on the ubiquitination of RAP80ΔC122. Our data showed that the single mutations diminished RAP80 multiubiquitination, while the double mutant A88,113S caused a more pronounced decrease in ubiquitination (Figure 8C). The results are in agreement with the conclusion that UIMRAP80 is required for the multi-monoubiquitination of the amino terminus of RAP80.

The UIMs of RAP80 are critical for its effects on ERα

Next, we investigated the importance of the UIMRAP80 on the interaction of RAP80 with ERα. First, we examined whether deletion of UIMRAP80 had any effect on the subcellular localization of RAP80. Full-length FLAG–RAP80 or FLAG–RAP80ΔUIM1,2 was transiently expressed in HeLa cells and their subcellular localization examined by confocal microscopy. Figure S4 shows that both FLAG–RAP80 and RAP80ΔUIM1,2 were localized to the nucleus.

To determine whether the UIMs play a role in the interaction between RAP80 and ERα, HeLa cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3.1–ERα–Myc-His and pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 expression plasmids encoding either full-length RAP80 or several UIM deletion mutants of RAP80. Co-immunoprecipitation analysis showed that deletion of a single UIM or both UIMs did not abrogate the interaction between RAP80 and ERα (Figure S5).

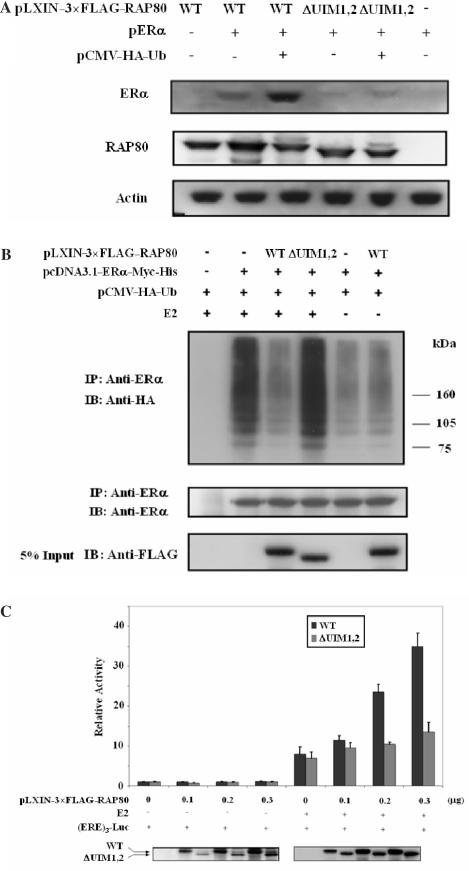

To determine whether UIMRAP80 was required for the observed increase in the level of ERα protein by RAP80, the effects of RAP80 and RAP80UIM1,2 on the level of ERα protein were compared. HeLa cells expressing pERα only contained low levels of ERα protein. RAP80 significantly enhanced ERα levels (Figure 9A), whereas RAP80UIM1,2 only slightly increased the level of ERα protein. Expression of HA–Ub caused a further increase in the level of ERα protein. These data suggest that the UIMRAP80 is required for the increase in ERα protein level induced by RAP80.

Figure 9.

Role of UIMRAP80 on the interaction of RAP80 with ERα. (A) UIM is required for the RAP80-induced increase in the level of ERα protein. HeLa cells were transfected with pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80, pERα and pCMV–HA–Ub. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were collected and protein cell lysates examined by western blot analysis using anti-ERα, anti-FLAG M2 and anti-actin antibodies. (B) Effect of RAP80 on ERα polyubiquitination. HeLa cells were transfected with pcDNA3–ERα–Myc-His, wild type pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 or FLAG–RAP80ΔUIM1,2 and pCMV–HA–Ub for 48 h and treated with or without E2 for 24 h. The cells were treated with MG132 for 4 h before collection and ERα proteins immunoprecipitated with an anti-ERα antibody. Western blot was performed with an anti-HA or anti-ERα antibody to detect ERα ubiquitination and the level of immunoprecipitated ERα, respectively. The level of FLAG–RAP80 expression was determined with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (lower panel). (C) UIM is required for the RAP80-induced increase in ERα-mediated transactivation. MCF-7 cells were transfected with different amounts of pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 or pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80ΔUIM1,2 and then treated with 100 nM E2 or ethanol for 24 h. Cells were collected and assayed for luciferase activity. The relative Luc activity was calculated and plotted. RAP80 expression was also detected with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (lower panels).

Previous studies have shown that ERα is degraded by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (14,16,20). Since UIMs have been implicated in ubiquitin binding and in the modulation of ubiquitination (31), this raised the question of whether RAP80 affected ERα ubiquitination. To examine this, HeLa cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1–ERα–Myc-His, pCMV–HA–ubiquitin and pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 or pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80ΔUIM1,2. Cells were treated with MG132 for 4 h before protein extracts were prepared and protein complexes immunoprecipitated with an anti-ERα antibody. The protein complexes were subsequently examined by western blot analysis with anti-HA antibody to detect ERα ubiquitination. In agreement with previous studies (16), the presence of E2 enhanced polyubiquitination of ERα (Figure 9B). Expression of RAP80 strongly inhibited ERα polyubiquitination whereas RAP80ΔUIM1,2 had little effect. These results suggest that the observed increase in the level of ERα protein induced by RAP80 (Figure 6) may involve reduced polyubiquitination and degradation of ERα. Reduced ERα protein levels were not observed in the experiment described in Figure 10C and may be due to the high expression of ERα induced by pcDNA3.1–ERα–Myc-His. RAP80 did not affect ERα ubiquitination in the absence of E2 (Figure 9B) or in the presence of tamoxifen (data not shown). The latter is in agreement with the demonstration that interaction of RAP80 with ERα is dependent on the presence of an agonist.

We next examined whether UIMRAP80 was required for the modulation of ERα-mediated transcriptional activation by RAP80. MCF-7 cells were co-transfected with an ERE-Luc reporter plasmid and different amounts of pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80 or pLXIN–3×FLAG–RAP80ΔUIM1,2. In the absence of E2, both RAP80 and RAP80ΔUIM1,2 had little effect on Luc reporter activity. Addition of E2 induced ERE-mediated transcriptional activation by endogenous ERα; this activation was enhanced by increased expression of RAP80. In contrast, expression of the RAP80ΔUIM1,2 mutant did not augment ERα-mediated activation of the reporter (Figure 9C). These results indicate that UIMRAP80 is critical for the modulation of ERα activity by RAP80.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identify ERα as a new RAP80-interacting protein. The interaction of RAP80 with nuclear receptors is very selective since a number of receptors, including ERβ, PPARγ, RORγ and ERRα were unable to interact with RAP80 either in the presence or absence of their corresponding ligand. The interaction of RAP80 with ERα is dependent on the presence of an ERα agonist, as E2 and E3, promoted this interaction whereas the antagonists ICI 182,780 and tamoxifen did not. Previous studies have shown that binding of an agonist to the ligand-binding pocket of ERα induces a conformational change in the receptor. This involves a repositioning of helix 12 that allows recruitment of co-activators that subsequently mediate the transcriptional activation of ERα target genes by ERα (3,6,40). Binding of an antagonist induces a conformational change that results in the recruitment of co-repressors rather than co-activators. The dependency of the interaction of RAP80 with ERα on agonist binding indicates that RAP80 interacts with the transcriptionally active conformation of ERα.

The interaction between RAP80 and ERα was confirmed by mammalian two-hybrid analysis and co-immunoprecipitation. In vitro pull-down analysis with GST–RAP80 protein demonstrated that RAP80 interacted with full-length ERα, ERαΔN180 (containing the DBD, hinge domain and LBD), and with ERαΔN248 (containing the hinge and LBD), but did not interact with ERαΔC248 (containing the amino terminus, including the DBD). These observations suggest that RAP80 and ERα physically interact with each other and indicate that the amino terminus and DBD of ERα are not an absolute necessity for this interaction. The requirement of the LBD of ERα is in agreement with our observation that the interaction is ligand dependent. Thus, ligand-induced changes could unmask binding motifs in ERα required for its interaction with RAP80.

To determine which domain in RAP80 is required for its interaction with ERα, the effect of various mutations in RAP80 on this interaction was examined. Analysis of a series of carboxyl-terminal deletions showed that the zinc finger motifs are not required for the interaction of RAP80 with ERα, but that the region between aa 304 and 404 is essential. A number of transcriptional mediators have been reported to interact with the LBD of agonist-bound ERα through a sequence containing an LXXLL consensus motif (3,41–43). RAP80 contains two related sequences 296ILCQL and 625LLSFL. However, deletion of 625LLSFL or mutation of 296ILCQL into 296ISCQL did not affect the interaction of RAP80 with ERα (not shown) suggesting that the interaction of RAP80 with ERα involves a different sequence.

In addition to the two zinc finger motifs, we identified two putative UIMs at the amino terminus of RAP80 that exhibit high homology to the consensus UIM eeexΦxxAxxxSxxexxxx (in which Φ is a hydrophobic residue, e is a negatively charged residue and x is any amino acid) (Figure 7A) (31,32). Several studies have shown that UIMs often mediate the monoubiquitination of proteins that contain these sequences (31,35,36,44). In addition, UIMs have been reported to bind ubiquitin and as such mediate intra- or intermolecular interactions by interacting with ubiquitinated target proteins or proteins containing a ubiquitin-like domain (30,31,35,37,45). Analysis of the UIMRAP80 demonstrated that RAP80 was able to bind polyubiquitin chains of different lengths and to varying degrees. In addition, UIMRAP80 was able to promote the monoubiquitination of a chimeric EGFP–UIMRAP80 protein and the amino terminus of RAP80 while no ubiquitination was observed when the UIMRAP80 was deleted. In addition, point mutations in A88 and A113, alanines that are highly conserved among UIMs, greatly diminish ubiquitination of RAP80 (Figure 8C) in agreement with previous observations (39). Although the UIMRAP80 contains two lysines, mutations of these lysines had little effect on RAP80 ubiquitination suggesting that they are not substrates for monoubiquitination. This is in agreement with reports indicating that lysines within UIMs are generally not monoubiquitinated (31). Based on the calculated size of ubiquitinated RAP80 (Figure 8A), it was concluded that several lysines may become monoubiquitinated. These observations support the conclusion that the UIMRAP80 domain in RAP80 is functional and able to guide monoubiquitination of RAP80 and, in addition, is able to bind ubiquitin. We propose that the UIMRAP80 domain mediates a signal that is critical to the function of RAP80.

Although the mechanisms of protein polyubiquitination and their role in targeting proteins to proteasomes for degradation has been intensively studied, the role of (multi)monoubiquitination is not as well understood (21,32,33,46). Monoubiquitination functions as a signal that affects the structure, activity or localization of the target protein, thereby regulating a broad range of cellular functions, including membrane protein trafficking, histone function, transcriptional regulation, DNA repair and replication. UIMs are required for the (multi)monoubiquitination of several proteins, such as epsin, Eps15, and Eps15R, involved in receptor endocytosis (33,37,44,47). These proteins play a critical role in the recruitment of plasma membrane receptor proteins to clathrin-coated pits and their internalization. Deletion or mutation in these UIMs greatly impacts the internalization of membrane receptors (48). A recent study provided evidence for an intramolecular interaction between monoubiquitin and the UIM in Eps15 and Hrs that prevents them to interact with ubiquitinated membrane receptors, thereby affecting their trafficking (37). Since RAP80 is a nuclear protein, it is likely not involved in membrane receptor endocytosis. Monoubiquitination has been reported to be involved in the regulation of several nuclear functions. For example, monoubiquitination of histones does not target them for degradation but has a role in the regulation of chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation (49,50). Monoubiquitination is also critical in DNA repair (51). For example, the subunit S5a (Rpn10) of the 19S proteosomal regulatory complex contains two UIMs that interact with the ubiquitin-like (Ubl) domain of RAD23B (HR23B), a protein that targets several proteins to the proteasome, including the excision repair factor XPC (30,32).

Monoubiquitination can also affect the localization of proteins (30,52). However, deletion of the UIMs in RAP80 does not affect its nuclear localization. In addition, our data show that the UIMs are not required for the interaction of RAP80 with ERα, but are critical to the effects of RAP80 on ERα function. Since several UIM-containing proteins have been reported to be involved in ubiquitination or ubiquitin metabolism, we examined whether RAP80 had any effect on the ubiquitination of ERα. Our results demonstrate that increased expression of RAP80 decreases the ubiquitination of ERα. Although the UIMs were not required for the interaction of RAP80 with ERα, deletion of UIMRAP80 eliminates RAP80's capacity to inhibit ERα ubiquitination suggesting that the UIMRAP80 is essential for the effect of RAP80 on ERα ubiquitination. What the functions of ubiquitination of nuclear receptors are, is still controversial and not yet completely understood (21). Ubiquitination of ERα appears to have multiple functions and can affect ERα protein levels and turnover and ERα-mediated transcriptional regulation at different steps in the ERα signaling pathway (14,16,53). One function of ERα polyubiquitination is related to targeting misfolded, unliganded ERα for degradation by the proteasome system. This involves binding of the Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP) which, through its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, ubiquitinates ERα (16,54). Another role of ERα ubiquitination relates to transcriptional regulation. Several studies have shown that in the presence of agonist, ERα is rapidly degraded by the proteasome system (14,17,20). This turnover of ERα appears to be important for efficient ERα-dependent transcriptional activation. Such a coupling between protein degradation and transactivation might be an integral part of nuclear receptor function. However, overexpression of proteasome 26S subunit PSMC5 (SUG1) enhances the ubiquitination of ERα in the presence of agonist and inhibited transcriptional activation (55). In addition, Fan et al. (56) reported that inhibition of proteasome degradation by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 enhanced ERα-mediated transcriptional activation. These studies suggest that there is a delicate balance between level of ERα protein and transcriptional activation.

Our results show that expression of RAP80 enhances ERα-mediated transcriptional activation possibly by causing an increase in ERα protein levels. The latter may be related to the reduced ERα ubiquitination and degradation. We show that the effects of RAP80 on ERα were dependent on UIMRAP80, supporting our hypothesis that this domain is critical to the function of RAP80. The effects of RAP80 on ERα are very similar to those recently reported for MUC1 (8). MUC1 was shown to stabilize ERα by inhibiting its ubiquitination (8). The carboxyl-terminal subunit of MUC1 was shown to associate with ERα complexes on estrogen-responsive promoters and to stimulate ERα-mediated transcription. MUC1 mediates this action by directly binding to the DBD of ERα in an agonist-dependent manner. These different findings indicate the complex role of ubiquitination in the regulation of ERα function (14,53).

In summary, in this study we identify ERα as a new RAP80-interacting protein and show that this interaction is dependent on ERα agonist binding. We demonstrate that RAP80 is a UIM-containing protein with two functional UIMs that are able to bind ubiquitin and direct monoubiquitination. These UIMs are not required for its interaction with ERα but appear necessary for the decrease in ERα polyubiquitination and the increase in ERα-mediated transcriptional activation induced by RAP80. Our observations show that the UIMRAP80 is critical for the function of RAP80 and suggests that RAP80 is an important modulator of ERα.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data is available at NAR Online.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Drs Bonnie Deroo, John Couse, and Erica Allen for their valuable comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIEHS, NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hewitt SC, Korach KS. Oestrogen receptor knockout mice: roles for oestrogen receptors alpha and beta in reproductive tissues. Reproduction. 2003;125:143–149. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1250143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace OB, Richardson TI, Dodge JA. Estrogen receptor modulators: relationships of ligand structure, receptor affinity and functional activity. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2003;3:1663–1682. doi: 10.2174/1568026033451727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilsson S, Makela S, Treuter E, Tujague M, Thomsen J, Andersson G, Enmark E, Pettersson K, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Mechanisms of estrogen action. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:1535–1565. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez R, Nguyen D, Rocha W, White JH, Mader S. Diversity in the mechanisms of gene regulation by estrogen receptors. Bioessays. 2002;24:244–254. doi: 10.1002/bies.10066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu L, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1999;9:140–147. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruff M, Gangloff M, Wurtz JM, Moras D. Estrogen receptor transcription and transactivation: structure-function relationship in DNA- and ligand-binding domains of estrogen receptors. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:353–359. doi: 10.1186/bcr80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKenna NJ, Xu J, Nawaz Z, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coactivators: multiple enzymes, multiple complexes, multiple functions. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999;69:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(98)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei X, Xu H, Kufe D. MUC1 oncoprotein stabilizes and activates estrogen receptor alpha. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi S, Shibata H, Yokota K, Suda N, Murai A, Kurihara I, Saito I, Saruta T. FHL2, UBC9, and PIAS1 are novel estrogen receptor alpha-interacting proteins. Endocr. Res. 2004;30:617–621. doi: 10.1081/erc-200043789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norris JD, Fan D, Sherk A, McDonnell DP. A negative coregulator for the human ER. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002;16:459–468. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.3.0787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu L, Wu Y, Gathings B, Wan M, Li X, Grizzle W, Liu Z, Lu C, Mao Z, Cao X. Smad4 as a transcription corepressor for estrogen receptor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15192–15200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandes I, Bastien Y, Wai T, Nygard K, Lin R, Cormier O, Lee HS, Eng F, Bertos NR, Pelletier N, Mader S, Han VK, Yang XJ, White JH. Ligand-dependent nuclear receptor corepressor LCoR functions by histone deacetylase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:139–150. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poukka H, Aarnisalo P, Karvonen U, Palvimo JJ, Janne OA. Ubc9 interacts with the androgen receptor and activates receptor-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:19441–19446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nawaz Z, Lonard DM, Dennis AP, Smith CL, O'Malley BW. Proteasome-dependent degradation of the human estrogen receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:1858–1862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henrich LM, Smith JA, Kitt D, Errington TM, Nguyen B, Traish AM, Lannigan DA. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 7, a regulator of hormone-dependent estrogen receptor destruction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:5979–5988. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.5979-5988.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tateishi Y, Kawabe Y, Chiba T, Murata S, Ichikawa K, Murayama A, Tanaka K, Baba T, Kato S, Yanagisawa J. Ligand-dependent switching of ubiquitin-proteasome pathways for estrogen receptor. EMBO J. 2004;23:4813–4823. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lonard DM, Nawaz Z, Smith CL, O'Malley BW. The 26S proteasome is required for estrogen receptor-alpha and coactivator turnover and for efficient estrogen receptor-alpha transactivation. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:939–948. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang M, Nilsson BO. Proteasome-dependent degradation of ERalpha but not ERbeta in cultured mouse aorta smooth muscle cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2004;224:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nirmala PB, Thampan RV. Ubiquitination of the rat uterine estrogen receptor: dependence on estradiol. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;213:24–31. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reid G, Hubner MR, Metivier R, Brand H, Denger S, Manu D, Beaudouin J, Ellenberg J, Gannon F. Cyclic, proteasome-mediated turnover of unliganded and liganded ERalpha on responsive promoters is an integral feature of estrogen signaling. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:695–707. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinyamu HK, Chen J, Archer TK. Linking the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to chromatin remodeling/modification by nuclear receptors. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;34:281–297. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JW, Ryan F, Swaffield JC, Johnston SA, Moore DD. Interaction of thyroid-hormone receptor with a conserved transcriptional mediator. Nature. 1995;374:91–94. doi: 10.1038/374091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imhof MO, McDonnell DP. Yeast RSP5 and its human homolog hRPF1 potentiate hormone-dependent activation of transcription by human progesterone and glucocorticoid receptors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:2594–2605. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verma S, Ismail A, Gao X, Fu G, Li X, O'Malley BW, Nawaz Z. The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBCH7 acts as a coactivator for steroid hormone receptors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:8716–8726. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8716-8726.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sentis S, Le Romancer M, Bianchin C, Rostan MC, Corbo L. Sumoylation of the estrogen receptor alpha hinge region regulates its transcriptional activity. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:2671–2684. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan Z, Kim YS, Jetten AM. RAP80, a novel nuclear protein that interacts with the retinoid-related testis-associated receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32379–32388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lei W, Hirose T, Zhang LX, Adachi H, Spinella MJ, Dmitrovsky E, Jetten AM. Cloning of the human orphan receptor germ cell nuclear factor/retinoid receptor-related testis-associated receptor and its differential regulation during embryonal carcinoma cell differentiation. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 1997;18:167–176. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0180167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen F, Cooney AJ, Wang Y, Law SW, O'Malley BW. Cloning of a novel orphan receptor (GCNF) expressed during germ cell development. Mol. Endocrinol. 1994;8:1434–1444. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.10.7854358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirose T, O'Brien DA, Jetten AM. RTR: a new member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that is highly expressed in murine testis. Gene. 1995;152:247–251. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00656-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujiwara K, Tenno T, Sugasawa K, Jee JG, Ohki I, Kojima C, Tochio H, Hiroaki H, Hanaoka F, Shirakawa M. Structure of the ubiquitin-interacting motif of S5a bound to the ubiquitin-like domain of HR23B. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:4760–4767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller SL, Malotky E, O'Bryan JP. Analysis of the role of ubiquitin-interacting motifs in ubiquitin binding and ubiquitylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:33528–33537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Fiore PP, Polo S, Hofmann K. When ubiquitin meets ubiquitin receptors: a signalling connection. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;4:491–497. doi: 10.1038/nrm1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katzmann DJ, Odorizzi G, Emr SD. Receptor downregulation and multivesicular-body sorting. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;3:893–905. doi: 10.1038/nrm973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young P, Deveraux Q, Beal RE, Pickart CM, Rechsteiner M. Characterization of two polyubiquitin binding sites in the 26 S protease subunit 5a. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:5461–5467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oldham CE, Mohney RP, Miller SL, Hanes RN, O'Bryan JP. The ubiquitin-interacting motifs target the endocytic adaptor protein epsin for ubiquitination. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1112–1116. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00900-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klapisz E, Sorokina I, Lemeer S, Pijnenburg M, Verkleij AJ, van Bergen en Henegouwen PMP. A ubiquitin-interacting motif (UIM) is essential for Eps15 and Eps15R ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:30746–30753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoeller D, Crosetto N, Blagoev B, Raiborg C, Tikkanen R, Wagner S, Dikic I. Regulation of ubiquitin-binding proteins by monoubiquitination. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:163–169. doi: 10.1038/ncb1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hofmann K, Falquet L. A ubiquitin-interacting motif conserved in components of the proteasomal and lysosomal protein degradation systems. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:347–350. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01835-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirano S, Kawasaki M, Ura H, Kato R, Raiborg C, Stenmark H, Wakatsuki S. Double-sided ubiquitin binding of Hrs-UIM in endosomal protein sorting. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:272–277. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brzozowski AM, Pike AC, Dauter Z, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Engstrom O, Ohman L, Greene GL, Gustafsson JA, Carlquist M. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature. 1997;389:753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang C, Norris JD, Gron H, Paige LA, Hamilton PT, Kenan DJ, Fowlkes D, McDonnell DP. Dissection of the LXXLL nuclear receptor-coactivator interaction motif using combinatorial peptide libraries: discovery of peptide antagonists of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:8226–8239. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shibata H, Spencer TE, Onate SA, Jenster G, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Role of co-activators and co-repressors in the mechanism of steroid/thyroid receptor action. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 1997;52:141–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gangloff M, Ruff M, Eiler S, Duclaud S, Wurtz JM, Moras D. Crystal structure of a mutant hERalpha ligand-binding domain reveals key structural features for the mechanism of partial agonism. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:15059–15065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009870200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polo S, Sigismund S, Faretta M, Guidi M, Capua MR, Bossi G, Chen H, De Camilli P, Di Fiore PP. A single motif responsible for ubiquitin recognition and monoubiquitination in endocytic proteins. Nature. 2002;416:451–455. doi: 10.1038/416451a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hicke L, Schubert HL, Hill CP. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;6:610–621. doi: 10.1038/nrm1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang S, Weissman AM. A field guide to ubiquitylation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004;61:1546–1561. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4129-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shih SC, Prag G, Francis SA, Sutanto MA, Hurley JH, Hicke L. A ubiquitin-binding motif required for intramolecular monoubiquitylation, the CUE domain. EMBO J. 2003;22:1273–1281. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barriere H, Nemes C, Lechardeur D, Khan-Mohammad M, Fruh K, Lukacs GL. Molecular basis of oligoubiquitin-dependent internalization of membrane proteins in mammalian cells. Traffic. 2006;7:282–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nickel BE, Davie JR. Structure of polyubiquitinated histone H2A. Biochemistry. 1989;28:964–968. doi: 10.1021/bi00429a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun ZW, Allis CD. Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast. Nature. 2002;418:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature00883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang TT, D'Andrea AD. Regulation of DNA repair by ubiquitylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;7:323–334. doi: 10.1038/nrm1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nabhan JF, Ribeiro P. The 19S proteasomal subunit POH1 contributes to the regulation of c-Jun ubiquitination, stability and subcellular localization. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:16099–16107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512086200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang H, Sun L, Liang J, Yu W, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Li R, Sun X, Shang Y. The catalytic subunit of the proteasome is engaged in the entire process of estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. EMBO J. 2006;25:4223–4233. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fan M, Park A, Nephew KP. CHIP (carboxyl terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein) promotes basal and geldanamycin-induced degradation of estrogen receptor-alpha. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:2901–2914. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Masuyama H, Hiramatsu Y. Involvement of suppressor for Gal 1 in the ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated degradation of estrogen receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12020–12026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fan M, Nakshatri H, Nephew KP. Inhibiting proteasomal proteolysis sustains estrogen receptor-alpha activation. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004;18:2603–2615. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.