Summary

Glycosylasparaginase (GA) plays an important role in asparagine-linked glycoprotein degradation. A deficiency in the activity of human GA leads to a lysosomal storage disease named aspartylglycosaminuria. GA belongs to a superfamily of N-terminal nucleophile hydrolases that autoproteolytically generate their mature enzymes from inactive single chain protein precursors. The side-chain of the newly exposed N-terminal residue then acts as a nucleophile during substrate hydrolysis. By taking advantage of mutant enzyme of F. meningosepticum GA with reduced enzymatic activity, we have obtained a crystallographic snapshot of a productive complex with its substrate (NAcGlc-Asn), at 2.0 Ǻ resolution. This complex structure provided us an excellent model for the Michaelis complex to examine the specific contacts critical for substrate binding and catalysis. Substrate-binding induces a conformational change near the active site of GA. To initiate catalysis, the side-chain of the N-terminal Thr152 is polarized by the free α-amino group on the same residue, mediated by the side-chain hydroxyl group of Thr170. Cleavage of the amide bond is then accomplished by a nucleophilic attack at the carbonyl carbon of the amide linkage in the substrate, leading to the formation of an acyl-enzyme intermediate through a negatively charged tetrahedral transition-state.

Keywords: catalytic mechanism, glycosylasparaginase, Michaelis complex, N-terminal nucleophile hydrolase, productive enzyme-substrate complex

Abbreviations: AGU, aspartylglucosaminuria; GA, glycosylasparaginase; NAcGlc, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine; NAcGlc-Asn, N4-(β-N-acetylglucosaminyl)-L-asparagine; Ntn, N-terminal nucleophile; r.m.s.d., root mean square deviation

Introduction

Glycosylasparaginase (GA) is a lysosomal amidase involved in the ordered degradation of Asn-linked glycoproteins 1. It belongs to a superfamily of enzymes called N-terminal nucleophile (Ntn) hydrolases, that catalytically use a processed N-terminal threonine, serine, or cysteine as both a polarizing base and a nucleophile to act on a variety of substrates 2. Several crystal structures of mature Ntn enzymes have been reported, including glutamine 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate amidotransferase 3;4, proteasome β-subunits 5–7, penicillin acylases 8–11, glucosamine 6-phosphate synthase 12, cephalosporin acylases 13;14, isoaspartyl aminopeptidase 15;16, Taspase1 17, plant asparaginase 18, as well as GAs 19–21. Despite a limited sequence homology and a wide variety of substrate specificities, the Ntn hydrolases share a common core stucture of an αββα sandwich 22, with the N-terminal threonine, serine, or cysteine residue situated at the catalytic center. The polar side-chain of this N-terminal residue is thought to act as a nucleophile during substrate hydrolysis. However, no histidine or other basic amino acid is present in the active sites of these enzymes, suggesting a unique class of amide hydrolyzing enzymes exists that is different from the four previously described classical proteinase families 23, among which the serine and cysteine proteases, whose hydroxyl or thiol groups serve as the active-site nucleophile, and the metalloproteases and acidic proteases, where the critical nucleophile is a bound water molecule. A distinctive mechanism has been proposed for the catalytic reaction of the Ntn hydrolase family: the free α-amino group on the N-terminal threonine, serine, or cysteine acts as the base required to enhance the nucleophilicity of its own side-chain nucleophile 2;5;8. This intra-residue base on the threonine or serine replaces the well characterized histidine base in the hydrogen-bonded triad that is present in the active-site of many serine proteases 24.

From bacteria to eukaryotes, GAs are conserved in amino acid sequences, tertiary structures, and activation of amidase activity by intramolecular autoproteolysis 25;26. To generate the catalytically critical N-terminal nucleophile, F. meningosepticum GA undergoes a process of intramolecular autoproteolysis from a single chain precursor to a mature/active enzyme with a 17-kDa α- and a 15-kDa β-subunit, and exposes the active site threonine at the newly generated N-terminal end of the β-subunit to process Asn-linked glycoproteins. Structural and biochemical studies indicate that this autoproteolysis is driven by conformational constraints at the scissile peptide bond 27–29.

Enabled by autoproteolysis, GA cleaves the β-N-aspartylglucosylamine bond that connects the carbohydrate chain to asparagine side-chains of proteins and is thus essential for metabolic turnover of Asn-linked glycoproteins 30;31. It can effectively hydrolyze a variety of glycoasparagines that contain L-asparagine, including its natural substrate N4-(β-N-acetylglucosaminyl)-L-asparagine (NAcGlc-Asn) (Figure 1). This enzyme requires both free α-amino and α-carboxyl groups on the asparagine, and that the 6 position of N-acetylglucosamine be free of fucose 32. These requirements on substrates lead to hydrolysis of the aspartylglucosylamine bonds after complete release of the glycosylated-asparagine from the polypeptide chain and the removal of inner fucose 33. The lack of GA activity causes accumulation of unprocessed metabolite glycoasparagines (mainly aspartylglucosamine) in the lysosomes of all cell types, and thus results in the lysosomal storage disease aspartylglycosaminuria (AGU) 34–37. AGU has been reported worldwide, with a high prevalence in the Finnish population due to a founder effect 33;38;39.

Figure 1. Hydrolysis reaction catalyzed by GA amidase.

GA cleaves the β-N-aspartylglucosylamine bond (indicated by the bold arrow) of its natural substrate NAcGlc-Asn during proteolytic processings of asparagine-linked glycoproteins, resulting in the release of apartic acid and aminoglycan. The latter product is then further hydrolyzed non-enzymatically to release ammonia and oligosaccharide.

It has been proposed that GA also utilizes the novel mechanism of intra-residue base-nucleophile for hydrolyzing the amide bond of glycoasparagines. Nonetheless, several key questions remain to be addressed about the detailed mechanism of GA hydrolysis. Substitution of serine for the catalytic threonine dramatically reduces hydrolase activity 40;41, suggesting that precise positioning of the hydroxyl group in the Michaelis (enzyme-substrate) complex is critical for GA catalysis. In addition, the interactions between the enzyme and the oligosaccharide part of the ligand remains to be seen. It is conceivable that solvent molecules or ions might be involved in the catalysis, and in the polarization of the nucelophile by the α-amino group of the N-terminal threonine. Furthermore, the detailed mechanism of the intra-residue base-nucleophile interactions has been controversial. Recently, based on hydrogen-bonding patterns in the crystal structure of isoaspartyl aminopeptidase-product complex, some concerns have been raised to question the intra-residue base-nucleophile polarization through a direct hydrogen bond 16. To address these issues, we have determined high-resolution crystal structures of a productive GA-substrate complex. Based on the current studies, a modified model of intra-residue base-nucleophile catalysis is proposed.

Results and Discussion

Cryocrystallographic approach to stabilize the enzyme-substrate complex

To visualize the structure of a pre-catalysis Michaelis (hydrolase-substrate) complex, one would need to prepare complex crystal with a hydrolyzable substrate but trap/stabilize it in the intact form during the entire course of diffraction data collection. This used to be done by using polychromatic or Laue X-rays generated by a synchrotron radiation source to look at a reaction intermediate in the sub-millisecond time range 42. During the past decade an alternative strategy has emerged, by combining rate-reduction (slower but still active mutants) with physical-trapping (cryocrystallography), and thus allowing diffraction data collection with a conventional monochromatic X-ray source 43;44. For such a strategy to work, the reaction rate needs to be reduced to a half-life (t1/2) in a range of minutes-to-hours. With a kcat of 16 per second to hydrolyze its natural substrate NAcGlc-Asn in solution 41, the wild type F. meningosepticum GA is apparently too fast for the cryocrystallographic approach. Thus, to study the Michaelis complex of GA with its natural substrate we chose a kinetically slower GA mutant, with the nucleophile Thr152 substituted with a cysteine (T152C). This mutant is still capable of autoproteolysis to generate an active hydrolase, which has a catalytic kcat of 1.5*10−4 s−1 for the natural substrate 41, and thus with an apparent t1/2 of about an hour assuming a first order reaction 25;41. We had previously shown that the structure of the T152C mature enzyme is essentially identical to that of the wild type enzyme, with an r.m.s.d. of 0.22 Å and 0.25 Å for all the main-chain atoms and active site atoms, respectively 20;28. Thus, the T152C mutant enzyme is suitable for a cryocrystallographic snapshot of GA catalysis.

To prepare productive enzyme-substrate complexes, we start with growing unliganded crystals of the T152C mutant enzyme in its mature form, which crystallizes under the same condition with the same crystal form as the wild type protein 45. Crystals were then soaked in various concentrations of substrate for different lengths of time at low temperature (4oC), and complexes were then stabilized in the crystal by cryocrystallography techniques for data collection. We have collected many diffraction data sets from crystals treated with various combinations of soaking time and substrate concentrations to increase substrate occupancy, but without ligand conversion into reaction intermediate and/or products. We found the optimal crystal preparation to capture a relatively homogeneous enzyme-substrate complexes is by soaking the preformed T152C crystals in a modified well solution containing 30 mM substrate NAcGlc-Asn solution for three minutes followed by flash-cooling at 100 K. Any other combinations of treatments, even though some better resolved diffraction data, resulted in either lower substrate occupancy or ambiguous electron density at the catalytic site, presumably due to an electron density averaged from a mixture of intact substrate, reaction intermediate and products (see below). For example, shortening the soaking time resulted in a dramatic reduction of the occupancies of the substrate at both sites, whereas soaking the crystals for longer time led to more substrate hydrolysis and thus more complicated images at the substrate sites. From the optimally treated complex crystal, there is clear electron density to fit the intact substrate in the catalytic site (Figure 2), indicating an essentially homogeneous population of substrate with substantial occupancy. Crystallographic statistics for this data collection and processing as well as model refinement are summarized in Table 1. The crystal structure of this GA-substrate complex has been determined at 2.0 Å resolution and refined to an Rfree of 21.5% and Rcryst of 17.0%.

Figure 2. Stereoview of extra electron density at the active site A of the T152C GA-substrate complex.

The cyan map is the Fo−Fc SA-omit map at 2.0 Å resolution, contoured at 2.5 σ. The map was calculated without any model in the substrate site or Cys152. The NAcGlc-Asn substrate molecule (carbons shown in cyan), omitted in the map calculation, is displayed in the extra density for reference. Side-chains of a few key active site residues are shown by atom type: yellow for carbons, blue for nitrogens, red for oxygens, and green for the sulfur atom of Cys152.

Table 1.

Crystallographic Statistics of the GA-Substrate Complex

| Statistics of Data Collection and Processing

| |

| Resolution (Å), overall (final shell) | 100–2.00 (2.07–2.00) |

| Space group | P21 |

| Cell axes (Å) | 46.1, 96.7, 62.0 |

| Cell angle (deg.): β | 90.6 |

| Reflection (total/unique) | 107,899/36,727 |

| Rsym a (%), overall (final shell) | 7.4 (30.1) |

| Completeness (%), overall (final shell) | 99.7 (99.4) |

| I/σI, overall (final shell)

|

14.7 (3.7)

|

| Statistics of Model Refinement

| |

| Nonhydrogen atoms | |

| Proteinb | 4,348 |

| Water | 377 |

| Ligandc | 69 |

| Rcrystd (%) | 17.0 |

| Rfreee (%) | 21.5 |

| R.m.s.d.f | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.014 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.58 |

| NCS (Ǻ) | 0.15 |

| Averaged B values (Å2) | |

| GA Main-chain | 17.6 |

| GA Side-chain | 21.0 |

| Substrate | 28.7 |

| Water | 27.9 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Most favored | 93.2 |

| Additional | 6.8 |

Rsym = ∑h∑i|Ihi−Ih|/∑h∑iIhi for the intensity (I) of i observations of reflection h.

All residues with alternative conformations are counted only once.

The number of atoms includes two substrate molecules and one acyl intermediate molecule. All of them were refined with partial occupancy.

Rcrys = ∑|Fobs − Fcalc|/∑|Fobs|, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

Rfree was calculated as Rcryst, but with 8% of the amplitudes chosen randomly and omitted throughout the refinement.

R.m.s.d. is root mean square deviation from ideal geometry, or deviation for all main-chain atoms between the two molecules in the asymmetric unit (residues with alternative conformations were excluded for NCS comparison).

Overview of the GA-substrate Complex Structure

In the asymmetric unit of the crystal, GA forms a homodimer with the two catalytic sites facing away from the dimer interface. These two crystallographically unique sites were designated as site A and B with the nucleophile Cys152 and Cys452, respectively. We have also previously shown that GA exists as a homodimer in solution 28. Between the two GA complexes in the crystal, the overall structures of GA are essentially identical, with an r.m.s.d. of 0.15 Å for all the main-chain atoms. The GA structures in the complexes are also very similar to the structures of the unliganded enzyme 20, with an r.m.s.d. of 0.29 Å for all the main-chain atoms. For each enzyme complex, the α- and β-subunits of GA together form a four-layer αββα-sandwich structure, like other N-terminal nucleophile hydrolases. All inter-layer loops cluster at one side of the structure, on the surface far from the dimer interface (Figure 3a). These loops provide functional groups for the active site, including the side-chains of residues Trp11, Ser50, Cys152, Arg180, Asp183 and Ser184, which are highly conserved throughout GA of all species. In addition, residues Thr170 from the strand bS2, Thr203 and Gly204 from the strand bS4, and Gly206 from the helix bH1 (Figure 3b) have also been proposed to participate in catalysis 20.

Figure 3. Stereoviews of the Michaelis (GA-substrate) complex structure.

(a) Overview of the complex structure. For clarity, only one GA molecule (with the active site A) from the dimer of GA-substrate complexes is shown with its α-subunit in cyan and β-subunit in green. All the active site residues are shown in blue and the bound substrate molecule NAcGlc-Asn in red. (b) Conformational change of GA at the active site A after substrate-binding. The active site residues before (“open” conformation) and after substrate-binding (“closed” conformation) are shown in grey and colors, respectively.

A Michaelis (Enzyme-Substrate) Complex

In the catalytic site of one complex (site A), the electron density map clearly shows the presence of predominantly uncleaved substrate molecule NAcGlc-Asn (Figure 2). The occupancy of the substrate was estimated to be 80% based on the electron density maps. The refined B factors for the substrate (average 28.7 Å2) are close to those for protein side-chain atoms (21.0 Å2). In this model, 20% of the GA active sites A remain empty. Interestingly, for residues Thr203 and Gly204 that form the catalytic site, two alternative conformations were observed with estimated occupancy of 80% versus 20%. The minor conformation looks very similar to the “open” conformation of the unliganded GA structure 20, with an r.m.s.d. for all the active site atoms of 0.28 Å, indicating an essentially identical conformation. On the other hand, the major conformation appears to adopt the “closed” conformation observed in the GA-product complex 19.

In the catalytic site of the second complex (site B), a bifurcated density with a well-defined α-carboxylate end interacting with Arg180 (supplemental Figure 6a) appears to derive from a mixture of aspartylated-enzyme intermediate and the uncleaved substrate, both have their carboxylate groups. Refinement of the structure with a combination of substrate and acyl-enzyme intermediate was attempted (supplemental Figure 6b), but the maps at this resolution could not model this with confidence. Nonetheless, the electron density does suggest that significant amount of substrate at the sites B inside the crystal has been converted into other species, likely the reaction intermediates and/or products. This observation lends further support for the appropriateness of using the T152C mutant enzyme to study a productive enzyme-substrate complex.

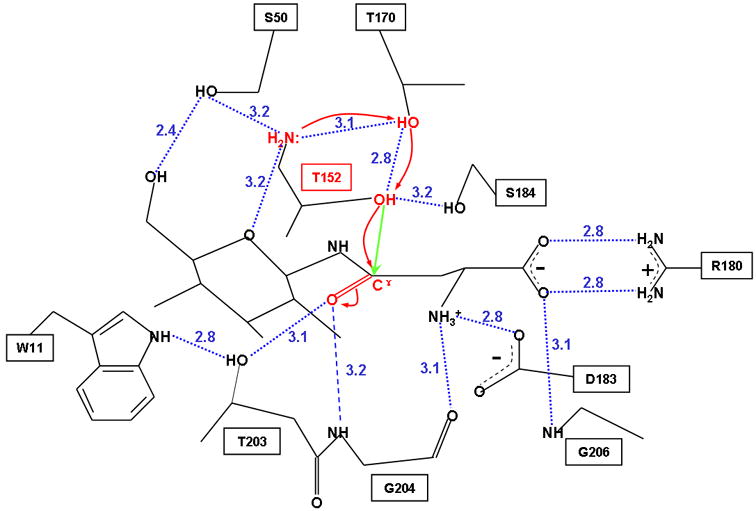

Atomic Interactions between GA and Substrate

The Michaelis complex structure at site A shows that the key residues involved in substrate-binding are conserved residues Trp11, Ser50, Cys152 (or Thr152 in the wild type enzyme), Arg180, Asp183, Thr203, Gly204 and Gly206. The interactions involve mainly several hydrogen-bonding interactions, two salt bridges, and multiple van der Waals contacts (Figure 4). Upon binding, the L-asparagine part of the substrate is placed into a narrow pocket which is formed by the side-chains of residues Cys152, Thr170, Arg180, Asp183, Ser184, Thr203 and the main-chains of residues Gly204 and Gly206 (Figures 3b and 4). The negatively charged α-carboxyl group of the substrate forms a salt bridge with the positively charged side-chain of Arg180. The α-carboxyl group of the substrate can also form two hydrogen bonds with the side-chain of Arg180, and another one with the main-chain nitrogen atom of Gly206. The free α-amino group of the substrate is hydrogen-bonded to the main-chain carbonyl oxygen of Gly204, and it also interacts with the side-chain of Asp183 through a salt bridge. These interactions are consistent with the requirement of free α-amino and α-carboxyl groups on the asparagine substrate 32. Residues Arg180, Asp183 and Gly206 are located far away from the scissile bond, and thus they are unlikely to be involved directly in the catalysis. Instead, they could serve as a docking device for the substrate binding and help maintain the conformation of the substrate molecule for better interactions with other active site residues. Mutagenesis of either Arg180 or Asp183 affected both the KM and kcat values, and the enzyme specificity was reduced by 200 to 106-fold 41.

Figure 4. Stereoview of the atomic interactions between GA and substrate.

Displayed are interactions between GA and the bound substrate molecule NAcGlc-Asn at the active site A. The active side-chain conformation of residue Cys152 is shown in magenta and the switch between its inactive trans- and active gauche(+) conformations is indicated by the magenta double arrow. Nucleophilic attack is indicated by the green straight arrow. A candidate water molecule to protonate the leaving group is also shown (W). The green dotted lines indicate possible hydrogen-bonding interactions between Cys152 and the surrounding residues. The blue dotted lines denote other hydrogen bonds involved in enzyme-substrate binding. Also shown is a hydrogen bond (a black dotted line) between side-chains of Trp11 and Thr203. Key active site residues are shown by atom type: yellow for carbons, blue for nitrogens, red for oxygens, and green for Cys152 sulfur atom. The salt bridge is indicated by the positive and the negative charges.

On the other end of the substrate, the oligosaccharide part is stabilized by two hydrogen bonds and various van der Waals contacts formed between GA and the substrate (Figure 4). The free α-amino group of Cys152 interacts with the oxygen atom at the 5-position of the substrate. In addition, the hydroxyl group at the 6-position of the substrate is located right between the side-chains of residues Trp11 and Ser50, and forms a hydrogen bond to the side-chain hydroxyl group of the latter (Figure 4), in line with the requirement that the 6-position of the glycan part be free of fucose. The aromatic side-chain of Trp11 was generally believed to play a role in carbohydrate-binding 46, involving mainly van der Waals contacts. It appears that the aromatic ring of Trp11 and the oligosaccharide part of the substrate are staggered with respect to each other (Figure 4), which is important in stabilizing the oligosaccharide 46. GA binds asparagine with a KM value 7-fold higher when compared to the NAcGlc-Asn substrate 41. However, only a small part of the glycan is located in the substrate-binding pocket and interacts with the active site residues. The majority of the glycan part extends outward into the bulk solvent (Figures 3B and 4). This may explain why GA allows variations in the oligosaccharide part of its substrate.

Conformational movements upon binding of substrate

Substrate-binding induces small but significant shifts of a few secondary structural elements around the active site. Previously we reported that the active site of the unliganded enzyme adopts an “open” conformation 20. As a result of substrate-binding, a closed conformation of the active site is adopted to grasp the substrate molecule (Figure 3b), similar to the conformation of a GA-product complex 19. This conformational change involves mainly residues 203–204 from bS4 as well as residues 237–256 from bH3, bH4, bS5 and the loops between them. The r.m.s.d. for main-chain atoms of these shifted secondary structural elements is 0.64 Å, whereas the deviation for all other residues is 0.23 Å. These movements are all toward the active site for binding substrate, with the Cα atom of residue Thr203 moving by 0.8 Å. Furthermore, the occupancy of the “closed” GA conformation approximates that of the intact substrate molecule, consistent with the notion that about 80% of this active site is substrate-occupied, while the other 20% is empty. The distance between the Cβ atom of the nucleophile Cys152 and the hydroxyl oxygen of Thr203, involved in the oxyanion hole (see below), is 6.5 Å in the “open” conformation versus 4.3 Å in the “closed” conformation. Therefore, the side-chain hydroxyl oxygen of Thr203 moves closer to the side-chain of Cys152 by 2.2 Å.

After substrate-binding, the side-chain of cysteine 152 in the T152C mutant does not immediately assume the rotamer conformer required for catalysis (Figure 2). Instead, it remains as the inactive conformation observed in the unliganded enzyme structure of the same mutant, with a trans position 20. In the wild type enzyme structure, this trans position of the threonine side-chain is taken by the methyl group, and the hydroxyl group takes the gauche(+) conformation that is suitable to initiate a nucleophilic attack at the substrate 20. The calculated (averaged) electron density at the catalytic site A of the T152C mutant clearly indicates that the inactive trans- rotamer conformation is the predominant conformation (Figure 2), suggesting that the active gauche(+) conformation only exists transiently for the T152C mutant. However, to form the acyl-enzyme intermediate (supplemental Figure 6), the thiol group would need to rotate into a productive position similar to that of wild type nucleophilic hydroxyl group of Thr152 20. Such a requirement of side-chain switch to activate the hydrolase activity was also found in another Ntn hydrolase, the glutaminase domain of glucosamine 6-phosphate synthase, in which a cysteine is the wild-type nucleophile 12.

Active site residues and comparisons with other Ntn hydrolases

The structure of the productive T152C GA-substrate complex has enabled us to analyze the catalytic roles of active site residues (Figure 4). To this end, we have modeled into the complex structure the active gauche(+) conformation for the thiol group, aided by the previously determined structure of the wild-type enzyme. In addition to the N-terminal nucleophile, conserved residues across species at the catalytic site have been proposed to play various roles during catalysis 20. We have now provided the structural basis to analyze their catalytic roles in detail:

In its active rotamer conformation, the nucleophilic thiol group of Cys152, 3.2 Å away from the targeted carbonyl carbon atom of the substrate, is stabilized by hydrogen-bond interactions with the side-chain hydroxyl groups of Thr170 and Ser184 (Figure 4). The line connecting the thiol group of Cys152 and the targeted carbon is almost perpendicular to the targeted carbonyl plane of the substrate, which is the optimal orientation for orbital overlap of the nucleophile and the targeted carbonyl carbon atom 47. In addition, the side-chain hydroxyl group of Thr170 also forms a hydrogen bond with the free α-amino group of Cys152 (Figure 4). This α-amino group is believed to act as the base during the catalysis process 2;19;20. Thus, the side-chain of Thr170 appears to be involved in the polarization of the nucelophile of the Cys152 side-chain by the free α-amino group, by bridging the α-amino group and the side-chain nucleophile on the same N-terminal residue. For Ser184, structural equivalent was also found in other Ntn hydrolases: Ser211 in isoaspartyl peptidase 16 and Thr225 in plant asparaginase 18. The hydroxyl groups of these side-chains could thus play a similar role in stabilizing the catalytic nucleophiles.

In the “closed” conformation, the side-chain hydroxyl oxygen of Thr203 is hydrogen-bonded to the side-chain carbonyl oxygen of the substrate (Figure 4). However, this interaction does not appear to be critical for substrate binding, since replacement of Thr203 with either cysteine or alanine does not affect the KM values substantially 41. Instead, it is likely that this interaction plays some role in stabilizing the negatively charged tetrahedral transition-state and thus is part of the so-called oxyanion hole 19;20. However, mutation of Thr203 to Ala203 reduced the kcat value by only 10-fold 41, suggesting that there is another component of the oxyanion hole. The distance from the main-chain nitrogen atom of Gly204 to the side-chain carbonyl oxygen of the substrate is 3.2 Å (Figure 4), although the angular geometry is not optimal for them to form a hydrogen bond. However, during the negatively charged tetrahedral transition-state, the carbonyl carbon of the substrate becomes sp3-hybridized, which would rotate the Cγ-Oδ1 bond clockwise around the Cβ-Cγ bond to adopt a slightly different orientation from that observed in the uncleaved substrate (Figure 4). This geometric adjustment could allow the main-chain nitrogen atom of Gly204 to interact and stabilize the oxyanion group of the tetrahedral transition-state. Collapse of this tetrahedral intermediate leads to breakage of the covalent β-N-aspartylglucosylamine bond, release of the oligosaccharide part of the substrate, and formation of an acyl-enzyme intermediate. This decomposition process is likely facilitated by a neighboring water molecule. A candidate water molecule is identified at the active site A (Figure 4), which is hydrogen-bonded to the amino group at the 1-position of the substrate and located 4.4 Å away from the base during the initial substrate-binding, but conformational change at the active site during formation of the tetrahedral intermediate could bring this water molecule closer to the base for action.

The aromatic side-chain of Trp11 plays important roles both in binding to the glycan part of the substrate and in catalysis. When Trp11 was mutated to Ser11, the kcat value for the natural substrate was reduced remarkably (500-fold) 41. This large reduction cannot be explained by loss of the hydrogen-bonding interaction between the side-chains of Trp11 and Thr203, because mutagenesis of Thr203 did not reduce the kcat value substantially. Instead, it appears that the interactions between the aromatic side-chain of Trp11 and the oligosaccharide part of the substrate not only facilitate substrate binding, but also maintain an optimal conformation of the substrate for catalysis. With the substrate properly bound, the nucleophilic Sγ atom of Cys152 (in its active conformation) points at the targeted carbonyl carbon of the substrate at a direction that is perpendicular to the carbonyl plane of the substrate, with a distance of 3.2 Å, suitable for a nucleophilic attack (Figure 4). If Trp11 is mutated to Ser11, loss of the van der Waals contacts and the stacking interactions between the side-chain of Trp11 and the glycan part of the substrate may lead to a conformational change of the substrate. This conformational change, although small, may result in large reduction in the catalysis. A well-characterized example is isocitrate dehydrogenase, for which small conformational changes of the substrate have been shown to alter the reaction rates remarkably 47. On the other hand, a substitution of Trp11 with a phenylalanine results in an inactive enzyme, due to the failure of autoproteolysis for enzyme activation 27,41.

Structural comparisons with enzyme-ligand complexes of other Ntn hydrolases have provided hints about their differences in substrate specificity. In isoaspartyl aminopeptidase, an insertion of over 20 amino acids fill out the space into which the carbohydrate moiety of GA substrate would bind and interact with the Trp11 of GA 16. As a result, these inserted residues reduce the size and hydrophobicity of the catalytic site in isoaspartyl aminopeptidase, and may explain why it cannot hydrolyze glycosylated asparagines substrates, in contrast to the function of GA. The substrate specificity differences between GA and Taspase1 are even more dramatic. GA requires a free α-carboxylate end on the substrates and act as an amidase to cleave the carbohydrate moiety off the asparagine side-chain. Taspase1, however, acts as an endopeptidase to cleave the peptide bond C-terminal to an aspartate residue 48. Structural comparisons reveal that the catalytic site of Taspases1 is larger due to a different side-chain conformation of Arg262 17, which is equivalent to the GA residue Arg180 involved in anchoring the free α-carboxylate group of substrate. This pocket enlargement appears to allow Taspase1 to bind the substrate in a different mode, by anchoring the β-carboxylate group of an aspartate side-chain to Arg262. Thus the side-chain conformational difference of Arg262 may contribute to the endopeptidase function of Taspase1, in contrast to the amidase function of GA.

Catalytic Mechanism of GA hydrolase

To analyze the catalytic mechanism of the native GA, we modeled the wild type Michaelis complex based on the T152C GA-substrate complex structure. To this end, we built in a threonine side-chain to replace the Cys152 in the complex, aided by the side-chain conformation previously determined for the wild type enzyme 20, followed by a 20-cycle overall energy minimization 49. In this model, the nucleophilic hydroxyl group of Thr152, stabilized by the side chain hydroxyl group of Ser184, aims at the targeted carbonyl carbon atom of the substrate with a distance of 3.0 Å (Figure 5). In general, the catalytic mechanism of GA is similar to classic serine proteases and thus utilizes a cycle of enzymatic acylation and deacylation 20;41. Thus, during GA catalysis, the key elements involved are the nucleophiles, the oxyanion hole and the base. The main difference between GA and serine proteases is the general base. Here, based on the productive GA-substrate structure, we analyze the detailed mechanisms of the side-chain hydroxyl group of Thr152 to serve as the nucleophile, and the free α-amino group on the same N-terminal residue to act as the base required to enhance the nucleophilicity20.

Figure 5. Proposed nucleophilic activation mechanism of GA.

The side-chain hydroxyl group of Thr152 serves as the nucleophile, and the free α-amino group on the same residue acts as the base. Polarization of the nucleophile by the base to enhance its nucleophilicity is mediated by the side-chain hydroxyl group of Thr170. The polarized nucleophile can then attack (indicated by a green straight arrow) the carbonyl carbon of the substrate, leading to electron-pair rearrangements (shown by red curved arrows) and formation of a tetrahedral transition-state. This negatively charged transition-state is stabilized by an oxyanion hole, consisting of the Oγ atom of Thr203 and the main-chain nitrogen atom of Gly204. Atoms and bonds involved in the nucleophilic activation are shown in red. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by blue dotted lines with the distances (in Å) labeled. The N-acetyl group of the substrate is not shown here for clarity.

Although it has been generally accepted that the N-terminal α-amino group is a candidate to act as the general base, the detailed mechanism to abstract proton from the nucleophilic side-chain is controversial. Previously two models have been proposed for the mechanism of nucleophilic activation by the free α-amino group. One model proposes that a tightly bound water molecule is recruited to mediate the nucleophilic activation in order to avoid unfavorable geometry of the direct intra-residue hydrogen bond 6;8. Another model, based on a structure of penicillin acylase complexed with a substrate analog, proposes a direct proton abstraction through an intra-residue hydrogen bond because of its close proximity and no nearby water molecule available to mediate the proton relays 11. In the present GA-substrate complex, there is no water molecule in the vicinity to mediate the nucleophilic activation. In addition, the free α-amino group is unlikely to directly polarize its own side-chain nucleophile due to an unfavorable geometry to form a direct intra-residue hydrogen bond. Instead, we found that in the GA-substrate complex the free α-amino group and the side-chain nucelophile are bridged by hydrogen bonds through the side-chain hydroxyl group of the conserved Thr170 with distances of 2.8–3.1 Å (Figure 5). It is conceivable that a dynamic motion during the reaction could modulate this hydrogen-bonding network to an even better geometry for the nucleophilic activation. Thus, it appears that the side-chain hydroxyl group of Thr170 mediates the polarization process for activation. Consistent with this model, mutation of Thr170 to Cys does not affect substrate binding significantly, but the kcat values of the mutants T170C and T170A were reduced by more than 700 and 3000-fold, respectively 41. In addition, the oxygen atom at the 5-position of the substrate may also play a role in stabilizing the base by formation of a hydrogen bond with the free α-amino group (Figure 5). Consistent with this notion, when asparagine was used as the substrate instead of NAcGlc-Asn, the kcat decreases 13-fold, indicating that the glycan part of the substrate also contributes to catalysis 41.

To investigate whether this nucleophilic activation of Thr-152 by Thr170-mediated mechanism is also applicable to other Ntn hydrolases, we compared the GA complex structure with that of other Ntn members (complexed with a substrate analog, reaction product, or ion). Specifically we searched, within the asparaginase family (including GAs) of the Ntn superfamily, for active-site residues equivalent to the T152/T170 pair in GA with the same spatial disposition relative to the ligand. The conserved threonine pair was found in other complex structures, including human GA (T183/T201) 19, isoaspartyl peptidase (T179/T197) 16, and plant asparaginase (T193/T211)18, as well as human Taspase1 in which the equivalent pair is T234/S252 17 and therefore the functional hydroxyl groups are also conserved. Thus we propose that, at least for the asparaginase family of the Ntn superfamily, the nucleophilic activation by the N-terminal α-amino group is mediated through the conserved side-chain hydroxyl group of a threonine or serine. Furthermore, with the substrate bound, this nucleophilic activation network is shielded from exposure to solvent. This might explain how the N-terminal α-amino group of the GA nucleophilic residue can remain in the unprotonated state which is necessary for its role as a general base, even in an acidic environment of lysosomes.

Concluding Remarks

Glycosylasparaginase is a well-known lysosomal amidase. The physiological importance of GA was revealed by identification of a human genetic disease, aspartylglucosaminuria (AGU). GA utilizes the free α-amino group of the N-terminal residue as the general acid/base to either polarize the nucleophile or depolarize the leaving group throughout the catalysis process. This is consistent with the observation that human GA has an optimum pH range of 7–9 50, at which a significant population of the N-terminal α-amino group is uncharged and free to act as the base. This has also raised the possibility that GA might have functions outside of lysosomes, for example, involvement in the myelination of the brain neurons 51. Nonetheless, the detailed mechanism of the nucleophilic activation by the α-amino group of the N-terminal residue has been controversial. In this study, we have described the crystal structure of a productive enzyme-substrate complex to address this issue. Instead of taking microsecond-resolution snapshots of a crystallized macromolecule as it undergoes catalytic turnover, we took advantage of the slow catalytic rate of a T152C mutant enzyme and cryocrystallography techniques. We found that when we soaked the crystals of the mutant for about three minutes with a high concentration of the substrate, substrate hydrolysis has already occurred at one site of the dimeric complex, although the substrate is mostly intact at the other site. The difference between the two catalytic sites is likely due to differences in microenvironment and substrate diffusion rate inside the crystals. Thus this complex is capable of hydrolyzing the natural GA substrate and is an excellent system to study GA catalysis. We found that the activation of the nucleophile by the α-amino group is mediated through a side-chain hydroxyl group of a conserved threonine, as opposed to the previously suggested activation via a water molecule mediation or via a direct hydrogen bond. Structural comparisons reveal that this conserved pair of hydroxyl groups with the same spatial disposition relative to the ligand also exists in other asparaginases within the Ntn hydrolase superfamily. Thus the structure of a productive GA-substrate complex presented here not only improves our understanding of the catalytic mechanism of GA, but also sheds new light on the catalytic mechanism of other Ntn enzymes.

Materials and Methods

Crystal Preparation

Overexpression, purification, and crystallization of autoproteolyzed F. meningosepticum GA protein (T152C mutant) were described previously 45. Microseeding was routinely used to improve crystal quality. Shortly before data collection, crystals of the T152C mutant were harvested into a modified well solution containing 10% glycerol for 3 minutes, and then harvested into another modified well solution containing 20% glycerol and 30 mM substrate (NAcGlc-Asn) for another 3 minutes followed by flash-cooling.

Data Collection and Processing

Diffraction data were collected from crystals flash-cooled at 100K using X-ray source from a Rigaku generator equipped with an R-Axis IV++ detector, then indexed and scaled using the HKL suite 52, and finally converted to structure factors using TRUNCATE from the CCP4 software package 53. The statistics of data collection and processing are shown in Table 1.

Structure Determination and Refinement

The complex structure was phased by the previously published structure of unliganded GA as the starting model 20. Each asymmetric unit contains two T152C GA complexes. To avoid model bias, a small part of the unliganded GA structure around the active sites was omitted in the initial phase calculations. Based on previous studies, residues Trp11, Cys152, Thr170, Arg180, Asp183, Thr203, and Gly204 are potential active site residues and were omitted in both non-crystallographic symmetry [NCS]-related molecules (2–3% of the structure). This partial model was further subject to rigid body, simulated annealing, grouped and individual temperature factor refinements as well as energy minimization before being used to calculate MR phases in CNS 49.

The first map was calculated at 2.1 Å resolution for model building in the program O 54. During refinement, tight NCS restraints were applied, exclusive of residues that were involved in crystal contacts or in nonstructural loops. After a few rounds of model rebuilding and automated refinement, clear electron density was seen for all residues in the final model, as well as a continuous electron density for the substrate molecule at the active site A. The models for the omitted residues were then built into the electron density one by one except residues Cys152, Thr203, Cys452 and Thr503. When the Rfree appeared to reach a minimum, resolution was extended to 2.0 Å. Several rounds of model rebuilding and refinement were performed, and then the NCS restraints were loosened little by little until the Rfree appeared to reach a minimum. Structural geometries were then optimized to reduce Rfree. Water molecules outside of the active sites were added and the structure was subject to another round of simulated annealing, temperature factor refinement, energy minimization, and manual rebuilding.

For residue Thr203 of chain B (forms active site A) and residue Thr503 of chain D (forms active site B), two alternative conformations can be identified. Residues Gly202 to Gly204 of chain B and residues Gly502 to Gly504 of chain D were then refined with two conformations to alleviate structural constraints with the occupancy 80% versus 20%, and 75% versus 25%, respectively (Figure 3B). The improved difference electron density at the active sites indicated an abundance of the uncleaved substrate molecule NAcGlc-Asn at the active site A (Figure 2) and a superposition of the uncleaved substrate molecule and presumably an enzyme-acyl intermediate at the active site B (supplemental Figure 6). A substrate molecule NAcGlc-Asn was then manually built in at the active site A with an estimate occupancy of 80%. In the final model, there are 10 and 8 residues missing, due to a lack of electron density, at the C-terminus of the α subunit of molecule A (residues 142–151) and B (residues 444–451), respectively. The final model quality was evaluated by PROCHECK 55. For residues with alternative conformations, only their major conformations were used in statistics calculations (Table 1).

Secondary Structure Assignment

The secondary structure of the refined GA-substrate complex was assigned by using the STRIDE web server 56 and compared to that of the unliganded GA structure assigned by the same software.

Structural Comparisons

All superimpositions between different structures were conducted using either LSQKAB from the CCP4 package 53 or MolMol 57. When the r.m.s.d. values for all the active site atoms were calculated, residues Trp11, Ser50, Cys152, Thr170, Arg180, Asp183, Ser184, Thr203, Gly204 and Gly206 from complex A(chains A/B) or their equivalents from complex B (chains C/D) were superimposed. When the overall r.m.s.d. values were calculated, all the main-chain atoms of the equivalent residues were compared.

Protein Data Bank accession codes

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited at the RCSB Protein Data Bank with accession code 2GL9.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. C.J. McKnight for critical reading and comments on the manuscript. We also appreciate all members of the lab for helpful suggestions and C. Guan for assistance on protein purification. This work was supported by Grant DK053893 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aronson NN, Jr, Kuranda MJ. Lysosomal degradation of Asn-linked glycoproteins. FASEB J. 1989;3:2615–22. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.14.2531691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brannigan JA, Dodson G, Duggleby HJ, Moody PCE, Smith JL, Tomchick DR, Murzin AG. A protein catalytic framework with an N-terminal nucleophile is capable of self-activation. Nature. 1995;378:416–9. doi: 10.1038/378416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JL, Zaluzec EJ, Wery JP, Niu L, Switzer RL, Zalkin H, Satow Y. Structure of the allosteric regulatory enzyme of purine biosynthesis. Science. 1994;264:1427–33. doi: 10.1126/science.8197456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muchmore CR, Krahn JM, Kim JH, Zalkin H, Smith JL. Crystal structure of glutamine phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase from Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 1998;7:39–51. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowe J, Stock D, Jap B, Zwickl P, Baumeister W, Huber R. Crystal structure of the 20S proteasome from the archaeon T. acidophilum at 3.4 A resolution. Science. 1995;268:533–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7725097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groll M, Ditzel L, Lowe J, Stock D, Bochtler M, Bartunik HD, Huber R. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 1997;386:463–71. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bochtler M, Ditzel L, Groll M, Huber R. Crystal structure of heat shock locus V (HslV) from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6070–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duggleby HJ, Tolley SP, Hill CP, Dodson EJ, Dodson G, Moody PC. Penicillin acylase has a single-amino-acid catalytic centre. Nature. 1995;373:264–8. doi: 10.1038/373264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suresh CG, Pundle AV, SivaRaman H, Rao KN, Brannigan JA, McVey CE, Verma CS, Dauter Z, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG. Penicillin V acylase crystal structure reveals new Ntn-hydrolase family members. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:414–6. doi: 10.1038/8213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonough MA, Klei HE, Kelly JA. Crystal structure of penicillin G acylase from the Bro1 mutant strain of Providencia rettgeri. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1971–81. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.10.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McVey CE, Walsh MA, Dodson GG, Wilson KS, Brannigan JA. Crystal structures of penicillin acylase enzyme-substrate complexes: structural insights into the catalytic mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:139–50. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isupov MN, Obmolova G, Butterworth S, Badet-Denisot MA, Badet B, Polikarpov I, Littlechild JA, Teplyakov A. Substrate binding is required for assembly of the active conformation of the catalytic site in Ntn amidotransferases: evidence from the 1.8 A crystal structure of the glutaminase domain of glucosamine 6-phosphate synthase. Structure. 1996;4:801–10. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y, Yoon K, Khang Y, Turley S, Hol WG. The 2.0 A crystal structure of cephalosporin acylase. Structure. 2000;8:1059–68. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00505-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JK, Yang IS, Rhee S, Dauter Z, Lee YS, Park SS, Kim KH. Crystal structures of glutaryl 7-aminocephalosporanic acid acylase: insight into autoproteolytic activation. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4084–93. doi: 10.1021/bi027181x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prahl A, Pazgier M, Hejazi M, Lockau W, Lubkowski J. Structure of the isoaspartyl peptidase with L-asparaginase activity from Escherichia coli. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:1173–6. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904003403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michalska K, Brzezinski K, Jaskolski M. Crystal structure of isoaspartyl aminopeptidase in complex with L-aspartate. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28484–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504501200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan JA, Dunn BM, Tong L. Crystal Structure of Human Taspase1, a Crucial Protease Regulating the Function of MLL. Structure (Camb) 2005;13:1443–52. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michalska K, Bujacz G, Jaskolski M. Crystal structure of plant asparaginase. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oinonen C, Tikkanen R, Rouvinen J, Peltonen L. Three-dimensional structure of human lysosomal aspartylglucosaminidase. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:1102–8. doi: 10.1038/nsb1295-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo HC, Xu Q, Buckley D, Guan C. Crystal structures of Flavobacterium glycosylasparaginase: an N- terminal nucleophile hydrolase activated by intramolecular proteolysis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20205–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xuan J, Tarentino AL, Grimwood BG, Plummer TH, Jr, Cui T, Guan C, Van Roey P. Crystal structure of glycosylasparaginase from Flavobacterium meningosepticum. Protein Sci. 1998;7:774–81. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oinonen C, Rouvinen J. Structural comparison of Ntn-hydrolases. Protein Sci. 2000;9:2329–37. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.12.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldberg AL. Functions of the proteasome: the lysis at the end of the tunnel. Science. 1995;268:522–3. doi: 10.1126/science.7725095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett AJ, Rawlings ND. Families and clans of serine peptidases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;318:247–50. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guan C, Cui T, Rao V, Liao W, Benner J, Lin CL, Comb D. Activation of glycosylasparaginase. Formation of active N-terminal threonine by intramolecular autoproteolysis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1732–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tikkanen R, Riikonen A, Oinonen C, Rouvinen R, Peltonen L. Functional analyses of active site residues of human lysosomal aspartylglucosaminidase: implications for catalytic mechanism and autocatalytic activation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2954–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Q, Buckley D, Guan C, Guo HC. Structural insights into the mechanism of intramolecular proteolysis. Cell. 1999;98:651–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Guo HC. Two-step dimerization for autoproteolysis to activate glycosylasparaginase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3210–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian X, Guan C, Guo HC. A dual role for an aspartic acid in glycosylasparaginase autoproteolysis. Structure. 2003;11:997–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makino M, Kojima T, Yamashina I. Enzymatic cleavage of glycopeptides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1966;24:961–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(66)90344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahadevan S, Tappel AL. Beta-aspartylglucosylamine amido hydrolase of rat liver and kidney. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:4568–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarentino AL, Plummer TH, Jr, Maley F. The isolation and structure of the core oligosaccharide sequences of IgM. Biochemistry. 1975;14:5516–23. doi: 10.1021/bi00696a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aronson NN., Jr Aspartylglycosaminuria: biochemistry and molecular biology. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1455:139–54. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(99)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haltia M, Palo J, Autio S. Aspartylglycosaminuria: a generalized storage disease. Morphological and histochemical studies. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1975;31:243–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00684563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arstila AU, Palo J, Haltia M, Riekkinen P, Autio S. Aspartylglucosaminuria. I. Fine structural studies on liver, kidney and brain. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1972;20:207–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00686902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palo J, Riekkinen P, Arstila AU, Autio S, Kivimaki T. Aspartylglucosaminuria. II. Biochemical studies on brain, liver, kidney and spleen. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1972;20:217–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00686903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maury CP. Accumulation of glycoprotein-derived metabolites in neural and visceral tissue in aspartylglycosaminuria. J Lab Clin Med. 1980;96:838–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mononen T, Mononen I, Matilainen R, Airaksinen E. High prevalence of aspartylglycosaminuria among school-age children in eastern Finland. Hum Genet. 1991;87:266–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00200902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saarela J, Laine M, Oinonen C, Schantz C, Jalanko A, Rouvinen J, Peltonen L. Molecular pathogenesis of a disease: structural consequences of aspartylglucosaminuria mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:983–95. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.9.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fisher KJ, Klein M, Park H, Vettese MB, Aronson NN., Jr Post-translational processing and Thr-206 are required for glycosylasparaginase activity. FEBS Lett. 1993;323:271–5. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, Guan C, Aronson NN., Jr Site-directed mutagenesis of essential residues involved in the mechanism of bacterial glycosylasparaginase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9688–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moffat K. Laue diffraction. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:433–47. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petsko GA, Ringe D. Observation of unstable species in enzyme-catalyzed transformations using protein crystallography. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2000;4:89–94. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoddard BL. Trapping reaction intermediates in macromolecular crystals for structural analyses. Methods. 2001;24:125–38. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cui T, Liao PH, Guan C, Guo HC. Purification and crystallization of precursors and autoprocessed enzymes of Flavobacterium glycosylasparaginase: an N-terminal nucleophile hydrolase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:1961–4. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999011798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vyas NK. Atomic features of protein-carbohydrate interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1991;1:732–40. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mesecar AD, Stoddard BL, Koshland DE., Jr Orbital steering in the catalytic power of enzymes: small structural changes with large catalytic consequences. Science. 1997;277:202–6. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsieh JJ, Cheng EH, Korsmeyer SJ. Taspase1: a threonine aspartase required for cleavage of MLL and proper HOX gene expression. Cell. 2003;115:293–303. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00816-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54 ( Pt 5):905–21. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaartinen V, Williams JC, Tomich J, Yates JR, 3rd, Hood LE, Mononen I. Glycosaparaginase from human leukocytes. Inactivation and covalent modification with diazo-oxonorvaline. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5860–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uusitalo A, Tenhunen K, Heinonen O, Hiltunen JO, Saarma M, Haltia M, Jalanko A, Peltonen L. Toward understanding the neuronal pathogenesis of aspartylglucosaminuria: expression of aspartylglucosaminidase in brain during development. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;67:294–307. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–26. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.CCP4 (Collaborative Computational Project N.4.) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–3. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47 ( Pt 2):110–9. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK; a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–91. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heinig M, Frishman D. STRIDE: a web server for secondary structure assignment from known atomic coordinates of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W500–2. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:51–5. 29–32. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.