Abstract

Intestinal epithelial cells respond to inflammatory extracellular stimuli by activating mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, which mediates numerous pathophysiological effects, including intestinal inflammation. Here, we show that a novel isoform of SPS1-related proline alanine-rich kinase (SPAK/STE20) is involved in this inflammatory signaling cascade. We cloned and characterized a SPAK isoform from inflamed colon tissue, and found that this SPAK isoform lacked the characteristic PAPA box and alphaF loop found in SPAK. Based on genomic sequence analysis the lack of PAPA box and alphaF loop in colonic SPAK isoform was the result of specific splicing that affect exon 1 and exon 7 of the SPAK gene. The SPAK isoform was found in inflamed and non-inflamed colon tissues as well as Caco2-BBE cells, but not in other tissues, such as liver, spleen, brain, prostate and kidney. In vitro analyses demonstrated that the SPAK isoform possessed serine/threonine kinase activity, which could be abolished by a substitution of isoleucine for the lysine at position 34 in the ATP-binding site of the catalytic domain. Treatment of Caco2-BBE cells with the pro-inflammatory cytokine, interferon γ, induced expression of the SPAK isoform. Over-expression of the SPAK isoform in Caco2-BBE cells led to nuclear translocation of an N-terminal fragment of the SPAK isoform, as well as activation of p38 MAP kinase signaling cascades and increased intestinal barrier permeability. These findings collectively suggest that pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling may induce expression of this novel SPAK isoform in intestinal epithelia, triggering the signaling cascades that govern intestinal inflammation.

Keywords: Ste20-Related Protein Kinase, Colonic SPAK isoform, p38 cascades, Caco2-BBE, Intestinal inflammation, Interferon γ

Introduction

Intracellular signaling cascades form the main routes of communication between the plasma membrane and regulatory targets in various intracellular compartments. Protein phosphorylation, which is reversibly mediated by kinases and phosphatases, is considered one of the most fundamentally important events governing cellular signal transduction. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, which is shared among many cellular signaling cascades, plays a significant role in transducing various extracellular stimuli, including growth factors and environmental stresses. Receive of these signals in the nucleus leads to alterations in various cellular processes. such as proliferation, differentiation, development, stress responses and apoptosis. Each of the related signaling cascades seems to consist of up to five levels of protein kinases that sequentially activate each other via phosphorylation.

At least six distinct MAPK pathways have been identified in multicellular organisms. Of them, three (the ERK, JNK and p38 cascades) have been characterized and are known to be involved in diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The three characterized MAPK cascades collectively orchestrate the intestinal inflammatory response, which also involves extensive cross-talk with other inflammatory signaling pathways, including the NF-kB and Janus kinase/STAT cascades (1,2,3). The genes encoding p38α and ERK1 are localized in major IBD susceptibility regions on chromosomes 6 (4) and 16 (5), respectively, and the JNK/p38 inhibitor, CNI-1493, was found to strongly reduce clinical disease activity in Crohn’s disease (CD) patients (6), providing additional evidence that such signaling plays important roles in intestinal inflammation.

The MAP pathways appear to share common upstream mediators, namely the Ste20 family of kinases. Ste20 was originally identified as a component of the pheromone-response pathway in budding yeast, and mammalian homologs have been identified to date (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13). The Ste20 family includes two subfamilies that share basic structural and functional properties. The first subfamily is made up of the p21-activated kinases (PAKs), which are characterized by a C-terminal catalytic domain and an N-terminal binding site for the small G proteins Rac1 and Cdc42. The second family is made up of the germinal center kinases (GCKs), which contain an N-terminal kinase domain and a C-terminal regulatory domain. The GCKs may be divided into 8 subfamilies based on homologies within their C-terminal domains (GCK1-VII). GCK VI contains the related human kinases, OSR1 (oxidation stress response kinase1) and SPAK/PASK (Ste20-related Proline-Alanine-rich Kinase), which share a conserved short C-terminal region (10, 11). OSR1 and SPAK are ubiquitously expressed, while PASK (the rat SPAK homolog) is widely expressed in most mouse tissues, particularly in cells having high ion transport activity (15). Both SPAK and PASK are highly expressed in epithelia and neurons (16), but PASK is found at only negligible levels in liver and skeletal muscle (17). Various studies have suggested that SPAK functions as a stress-responsive scaffolding protein (18) and/or acts to regulate the activity of the Sodium Potassium Chloride co-transporter (NKCC1) (15, 16, 19,20). However, no previous study has evaluated SPAK expression, activity, or signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. Thus, we herein examined the expression and role(s) of the Ste20-related Proline-Alanine-rich Kinase in intestinal epithelial cells.

Materials and methods

Total RNA preparation

Total RNA was prepared from normal and inflamed human colonic tissue and Caco2-BBE cells treated with or without cytokines with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), polyA+ mRNA was purified using the Oligotex Direct mRNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Complementary DNA was synthesized using the cDNA cycle kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Molecular cloning of SPAK

RT-PCR was performed with three degenerate oligonucleotide primers corresponding to three highly conserved amino acid sequences found in the catalytic domain (subdomain I, VIb and VIII) of protein kinases (LGXGSFGKVY, P1 5′ YTN GGN III GGN WSN TTY GGN AAR GTN TA 3′; IHRDLKPXNIL, P2 5′ NAR DAT RTT III NGG YTT NAR RTC NCK RTG DAT 3′; YWMAPEVL, P3 5′ NAR NAC YTC NGG NGC CAT CCA RTA 3′), as previously described by Wilks (21). Degenerate PCR was performed with the platinum Taq DNA polymerase kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using cDNA from inflamed human colonic tissue as the template. The resulting PCR products were cloned into TOPO vectors (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and subjected to nucleotide sequencing (Lark Company, Houston, TX). To obtain a full-length cDNA sequence, 5′ and 3′ Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) amplifications were carried out using a commercial RACE kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and specific primers (5′ RACE, P4 5′ GCC TCT TCC AGA ACT CCA TTC TTG 3′ and P5 5′ GGT CAC TAC GTT GGG ATG GCT GCA 3′; 3′ RACE, P6 5′ CTG TGG TTC AGG CAG CCC TAT GC 3′ and P7 5′ CTA AGT GGA GGT TCA ATG TTG G 3′). Finally the full length colonic SPAK was obtained by PCR with forward primer 5′ATGGCGGAGCCGAGCGGCTCGCCCGTG 3′ and reverse primer 5′GCTGACACTCAACTGAGCAAACCCAAT 3′. The PCR products were cloned and sequenced as described above. The full-length cDNA sequence was subjected to predicted amino acid sequence analysis using PSORT II, CLUSTAL W, and other programs available at the EMBNET, ExPASy or NCBI websites.

PCR amplification of SPAK

We obtained cDNA from Caco2-BBE cells and commercial cDNA from human colon, liver, spleen, brain, prostate and kidney tissues (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). To obtain higher resolution of the PCR products, the RT-PCR was performed with primers in the N-terminal region, forward primer: 5′ ATGGCGGAGCCGAGCGGCTCGCCCGTG 3′ and reverse primer: 5′ TTCTTGTGTTCTCCTCGGTTGACAATG 3′. To check the potential splicing site of SPAK, we performed two genomic PCRs, one is to obtain part of the first exon and first intron with the forward primer in first exon as above and reverse primer in the first intron: 5′ CTGTTGAAGCCAGTAGGCCCCGAAGCCGGC 3′. The other one is to obtain the joint part of the seventh exon and the seventh intron with the primers as followed: forward primer 5′ GCAACAGGAGCAGCGCCTTATCAC 3′, reverse primer 5′ CTATCAACCTCCATCAACCAATCTG 3′. The PCR products were cloned into sequence vector and subjected to sequence analysis. The SPAK genomic sequence was referenced from NCBI GenBank with the accession number: NW_921585.

Northern blot

To examine the splice isoform of SPAK in Caco2-BBE cells, northern blot analysis was performed using the North2South Complete Biotin Random Prime Labeling and Detection Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) with three different probes; one probe in the N-terminal of SPAK in colon which does not include PAPA box was obtained by PCR with primer I forward 5′ ATGGCGGAGCCGAGCGGCTCGCCCGTG 3′ and primer I reverse: 5′ TTCTTGTGTTCTCCTCGGTTGACAATG 3′, the template is from Caco2-BBE cells. The second probe was PCR amplified from liver tissue which is the PAPA box with the primer II forward 5′ TGACAGCGGCGGCGGCGGCG 3′, primer II reverse 5′ ATAACCTCCTGCAGCTCGTAC 3′, the template is commercial liver cDNA; The third probe was PCR product with the primer III which contains the sequence including F helix loop and some other junction part forward 5′ AAGGCTGACATGTGGAGTTTTGGA 3′, primer III reverse 5′ ATCTCGTCGTCACTCCACTCCCAG 3′ which is in the C-terminal regulatory domain, the template is also from commercial liver cDNA. The northern blot was performed according to the protocol with the 18s RNA to show same loading of samples.

Plasmid construction

For kinase activity and other functional assays, the full-length cDNA encoding SPAK was inserted into pcDNA3.1/V5 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) such that the V5 tag was fused to the C-terminus of the encoded SPAK protein (pcDNA3.1/V5/SPAK-like), or into pcDNA6 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), such that the Xpress tag was fused to the N-terminal of the encoded SPAK protein (pcDNA6/Xpress/SPAK-like). To generate a kinase-deficient mutant of SPAK, a conserved lysine in the kinase domain (amino acid 34 in the ATP binding domain) was replaced with an isoleucine using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and specific primers (forward 5′ AAG AAC GTG TAG CAA TAA TAC GGA TCA ACT TGG AAA AAT G 3′ and reverse 5′ CAT TTT TCC AAG TTG ATC CGT ATT ATT GCT ACA CGT TCT T 3′). The constructed plasmids were purified using the Qiagen maxiplasmid kit and verified by sequencing.

Quantitative PCR

Caco2-BBE cells were treated with proinflammatory cytokines (20 ng/ml TNF-α, 10 ng/ml TGF-β or 1000U/ml IFN-γ) for 24 hours and real-time PCR was used to quantify SPAK transcript levels. Total RNA was extracted using trizol method (Qiagen, Qiagen, Germantown, MD), and reverse transcribed using the Thermoscript™ RT-PCR System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The resulting cDNAs (50 ng) were PCR amplified using the SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix and the iCycler sequence detection system (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Specific primers were designed using the Primer Express Program (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and had the following sequences: forward, 5′ AAG TGG TCA CCT TCA TAA AAC CG 3′ (nt 903–925) and reverse, 5′ GAT GAG AAG AGC GAA GAA GGG AAA G 3′, (nt 961–985). The cycling conditions consisted of 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. The expression levels of β-actin were used as an internal control, and fold-induction was calculated by the relative standard curve method. For graphical representation of quantitative PCR data, raw cycle threshold values (Ct values) obtained for cytokine-treated cells were deducted from the Ct value obtained for internal β-actin transcript levels, using the ΔΔCt method as follows: ΔΔCT=(Ct,Target − Ct,Actin)treatment − (Ct,Target − Ct,Actin)non-treatment, and the final data were derived from 2−ΔΔCT.

Cell culture and transfection

The Caco2-BBE human intestinal cell line was cultured in OptiMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), with twice weekly changes of medium. Cells were kept in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C. For transfections, 2×105 Caco2-BBE cells were seeded in 6-well plates. At 60–80% confluence (approximately 24 h post-plating), the cells were transfected with 2 μg of the relevant plasmid using the Lipofectin transfection reagent (Invitrogen). Briefly, Lipofectin (6 μl/well) and plasmid DNA were separately suspended in OptiMEM (50 μl/total volume each) and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The suspensions were combined and incubated at room temperature for an additional 20 min (final volume 100 μl/well). The media from the Caco2-BBE cell cultures were then replaced with the Lipofectin-DNA suspensions, and the cultures were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 6 h, the transfection media were replaced with Opti-MEM containing fetal bovine serum, and transfectants were selected in medium containing 1.2 mg/ml G418 (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Clones were viewed under light microscopy, and were selected and trypsinized with cloning rings. Ten selected clones harboring each construct were maintained in 1.2 mg/ml G418 and were expanded.

Staining and confocal microscopic examination of Caco2-BBE cells

Caco2-BBE cells transfected with or without the indicated plasmids were grown on filters (0.4 μm pore size; Costar, Cambridge, MA). At 100% confluence, the cells were washed twice in HBSS, pH 7.4, and then fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in Hank’s balanced salt solution with calcium, pH 7.4 (HBSS+). The cells were then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton for 30 min at 25°C, and the fixed and permeabilized cells were rinsed and incubated with rhodamine-phalloidin (Invitrogen; diluted 1:60) for 40 min. The fixed and permeabilized cells, but not untreated cells, were blocked for 1 h in 0.2% gelatin and 0.08% saponin in HBSS+ and then all monolayers were incubated for 1 h with 1 μg/ml mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for the V5 or Xpress tags (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The monolayers were stained with anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate antibodies (Roche, Indianapolis, IN; diluted 1:1000) and examined with a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) equipped with an MRC600 confocal unit (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The results were analyzed using laser scanning microscope image analysis software (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), as previously described (22).

TNT-based in vitro transcription/translation of colonic SPAK

The TNT T7 Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System (Promega, Madison, WI) was used for in vitro transcription and translation of SPAK and the kinase-deficient mutant; here p38/pcDNA3 acts as a control. Briefly, 40 μl of TNT T7 Quick Master Mix, 2 μl of S35 methionine or unlabeled methionine and 1 μg of the appropriate plasmids were mixed in a total volume of 50 μl, and the reactions were incubated at 30°C for 70 min. The transcribed/translated proteins could be used directly for the following experiments.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then lysed on ice in appropriate volume of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P40) containing 1 mg/ml aprotinin, 1 mM pepstatin and 2 mM serine proteases for 15 min. The lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were subjected to immunoprecipitation or immunoblot (Western blot) analysis. For immunoprecipitation, the supernatants were incubated overnight at 4°C with 50 μl of protein G-Agarose beads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to clear nonspecific proteins and immunoglobulin. The samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 20s, and the supernatants were incubated for 4 hours at 4°C with 1 μg of anti-V5 or -Xpress antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), with gentle rocking. Protein G-Agarose beads (50 μl) were added to each mixture and the samples were incubated overnight at 4°C. The samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 20s, and the beads were collected and washed twice each for 20 min with buffer 1 (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P40), buffer 2 (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Nonidet P40) and buffer 3 (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% Nonidet P40). For immunoprecipitation of the TNT-expressed proteins, 450 μl of lysis buffer was added directly to the expression system, and samples were processed as described above.

Western blot analysis

Treated and untreated cells were lysed in 200 μl lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St Louis, MO), 1 mM PMSF, 1 μm leupeptin, 1 mM Na3VO4 and 20 mM β-glycerophosphate on ice for ~30 min. The samples were centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatants were collected, and protein concentrations were determined using a SmartSpec 3000 (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Proteins (40 μg) were suspended in 3X protein loading buffer (BioRad, Hercules, CA), boiled for 5 min, and resolved by SDS-PAGE. The resolved proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a semi-dray transfer cell (BioRad), and the membranes were blocked for 1 h with PBS containing 5% skim milk and Tween-20. The appropriate primary antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 1% skim milk, and incubated with the membranes overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then washed 3 times for 5 min each in PBST, the blots were detected with HRP-labeled anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ; 1:20,000) for 1 h, washed 3 times for 5 min each in PBST, and visualized by ECL (Denville Scientific Inc, South Plainfield, NJ).

Immune complex kinase assay

For assays of exogenous substrate phosphorylation, immune complexes were prepared as described above, washed 3 times with lysis buffer, and washed twice with kinase buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 12.5 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM Na3VO4 and 1 mM PMSF). The substrate, myelin basic protein (MBP; 3 μg; Upstate, Charlottesville, VA) was added to immune complexes in the presence of Mg2+/ATP (diluted with cold ATP to a final concentration of 200 μM) in kinase buffer (final reaction volume, 30 μl), and samples were incubated at 30°C for 30 min in a water bath. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 10 μl of 3×SDS-PAGE buffer, the samples were resolved by 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE, and the resolved proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for phosphorylated MBP. For detection of MAPK activity, the samples were prepared and blotted as described above, and then detected with antibodies against Xpress (Invitrogen), Erk, JNK, p38, phospho-Erk, phospho-JNK and phospho-p38 (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). As positive control, we treated the Caco2-BBE cells with EGF (10 ng/ml, 2hr) (Peprotech, Rocky hill, NJ) or IL-1 (2 ng/ml, 20 minutes) (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN), then probed with relevant antibodies.

Electrophysiological studies

Caco2-BBE cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and allowed to grow to confluence on filters (1 cm2 Snapwell polyester filters, Corning Costar, Corning, NY). Transepithelial Resistance (TER) was measured on day 8 post-plating. Briefly, the filter rings were detached and mounted in Ussing chambers that had been pre-incubated in KREBS solution (138 mM NaCl, 0.3 mM Na2HPO4, 0.4 MgSO4.7H2O, 0.5 mM MgCL2.6H2O, 5 mM KCL, 0.3 mM KH2PO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) at 37°C, with continuous bubbling of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The fluid volume on each side of the filter was maintained at 5 ml. Voltage-sensing electrodes (Ag/AgCl pellets) and current-passing electrodes (silver wire) were connected by agar bridges containing 3 M KCl, and interfaced via head-stage amplifiers to a microcomputer-controlled voltage/current clamp (DM-MC6 and VCC-MC6, respectively; Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA). The voltage-sensing electrodes were matched to within 1 mV asymmetry and corrected by an offset-removal circuit. The current between the two compartments (values reported are with reference to the apical side) was monitored and recorded at 5s intervals, and the voltage was clamped to zero. The total resistance between the apical and basal compartments was determined at the start and at intervals throughout each experiment, using the voltage evoked by a 5 μA bipolar current pulse in Ringer’s solution. The background resistance was determined with blank filters (representing the sum of the filter resistances), and the TER was determined by subtracting the resistance of the fluid in the chambers, current-passing electrodes and bridges from the total resistance measured with filters containing attached cell monolayers. For each experiment, the TER was collected after a 20 min equilibrium period; the TER was maintained within 10% of its baseline value for at least 1 h, whereas the duration of an experiment was typically ~10 min. The reported TER value for each experiment is the average of the TER values collected at 5s intervals over 10 min. Each experiment was repeated at least 4 times. The results are expressed as means ± SD, and the statistical significance was determined using ANOVA with Tukey’s Post-hoc test (Graph Pad InStat3; Graph Pad, San Diego, CA).

Results

Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of a colonic SPAK isoform

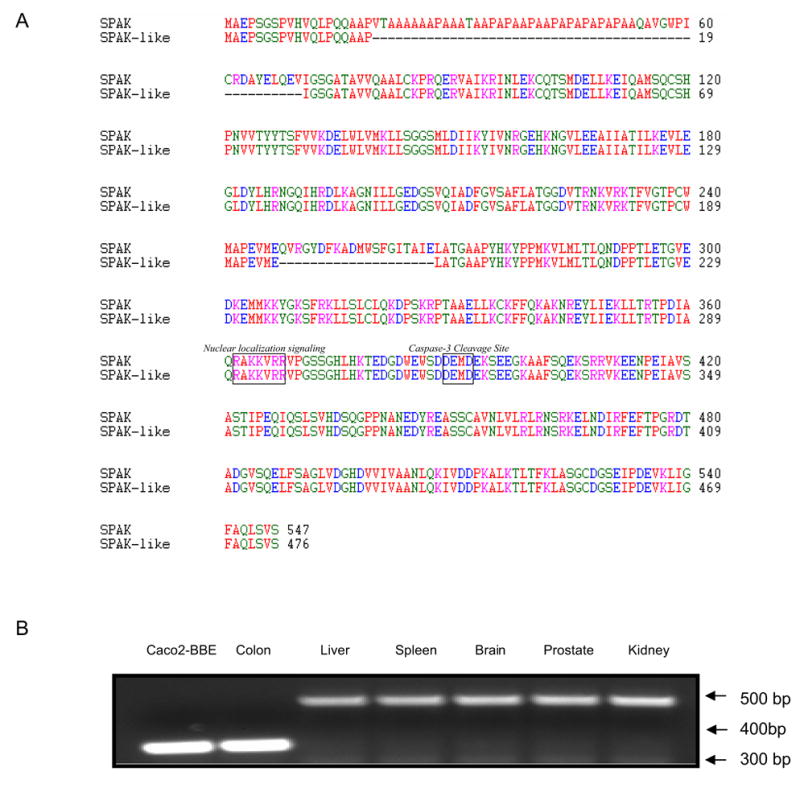

In an effort to clone a serine/threonine kinase cDNA from inflamed human colon tissue, we designed primers P1, P2 and P3 corresponding to conserved regions in the middle of human protein kinase genes. Screening with degenerate RT-PCR from inflamed human colon tissue yielded one out of 8 randomly chosen clones which had an identical sequence. Sequencing allowed us to identify a single 350 bp fragment having high homology to members of the Ste20-like kinase family. Both 5′ and 3′ RACE resulted in a single product, same as above, 8 random clones were picked to sequence for both 5′ and 3′ RACE. A PCR was performed to isolate the full-length transcript of 1431 bp with a 138 bp UTR before the translation start site (ATG) and ends with stop codon TGA. The transcript encodes a predicted protein of 476 amino acids (Figure 1A) with a calculated molecular weight of about 52.6 kDa and a pI of 6.51. The predicted protein exhibited the closest homology to members of the Ste20-like kinase family such as STK39 (NP_037365): 92%, LOK-like (AAN72832): 31%, SLK (AF006640): 46% and we thus designated the isolated protein colonic SPAK or ‘SPAK-like’ (GenBank accession number: AY629298). The isolated colonic SPAK isoform transcript contained the expected N-terminal serine/threonine kinase domain and C-terminal regulatory domain. Alignment of the predicted sequence with those of other kinases such as SLK, LOK-like and STK39 revealed that the kinase domain contains 10 highly conserved subdomains with the exception of the domain IX (F alpha-helix loop) (Figure 1A). In addition, unlike other STK39 molecules (Serine Threonine Kinase), the SPAK sequence does not contain a PAPA box. However, we did identify a potential caspase-3 cleavage site (DEMD) between the kinase and regulatory domains, as well as a nuclear localization signal (RAKKVRR) in the regulatory domain (Figure 1A). PSORT II- and kNN-based predictions of cytoplasmic/nuclear localization indicated that SPAK should be located in the nucleus (reliability = 94.1).

Figure 1. Colonic SPAK is a SPAK isoform that appears to be colon-specific.

A) Amino acid sequence comparison of SPAK and colonic SPAK. Both SPAK and colonic SPAK isoform contain a potential caspase-3 cleavage site (DEMD) located between the kinase and regulatory domains, as well as a nuclear localization signal (RAKKVRR). Unlike other SPAK, colonic SPAK does not contain a PAPA box within its amino acid sequence. B) cDNAs obtained from Caco2-BBE cells, colon, liver, spleen, brain, prostate and kidney were subjected to PCR with primers specific to N-terminal part of SPAK. Caco2-BBE cells and colon tissues yielded a single ~330 bp product, while liver, spleen, brain, prostate and kidney samples yielded a single ~500 bp product.

Colonic SPAK is a colon-specific SPAK isoform

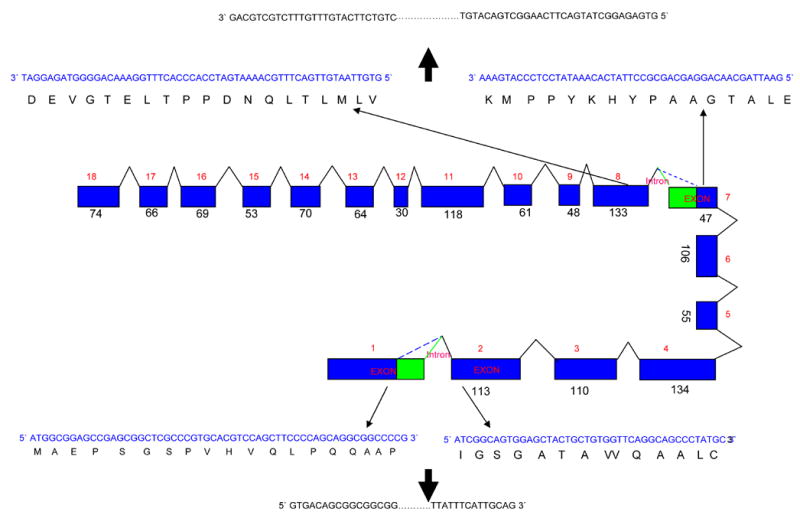

We then investigated the presence of SPAK in Caco2-BBE cells and non-inflamed colon, as well as liver, spleen, brain, prostate and kidney tissues. As shown in Figure 1B, the SPAK specific primers generated a single 335 bp product in Caco2-BBE and colon tissue samples, but yielded a single 488bp product in the other tissues. Sequence analysis revealed that the SPAK product from Caco2-BBE cells and colon tissues were identical to the larger SPAK product in the other tissues, with the exception that the colon-associated SPAK isoform lacked the characteristic PAPA box. This isoform was not observed in the other tested tissues, suggesting that it may be colon-specific. Since it was very intriguing that the colon SPAK does not have PAPA box and F alpha-helix loop, we analyzed the SPAK genomic sequence. On the one hand we performed alignment of colonic SPAK cDNA sequence with genomic sequence obtained from GenBank (Figure 2A); on the other hand we cloned the joint part genomic sequence of the first exon and first intron, seventh exon and seventh intron, from Caco2-BBE cell line (Figure 2B). From the alignment and genomic sequence, the SPAK gene is composed of 18 exons spanning 184 kb of the long arm of chromosome 2 (Figure 2A). The joint part sequence of the first exon and the first intron showed that the universally conserved GT nucleotides are present in the 5′ junction sequence. Interestingly there are GT nucleotides after GCCCCG (amino acids AP) (Figure 2A), from the genomic sequence provided by GenBank. We found in the 3′ junction sequence, all the SPAK share the common AG nucleotides as the end of the first intron. Exactly the same unusual splicing event occurs around the F helix loop in the IX subdomain, the GT nucleotides after the nucleotides ATGAAA (Amino acid MK) (Figure 2A). We found in the 3′ junction part from GenBank genomic sequence the universally conserved AG nucleotides as the end of the seventh intron. Those above indicated the potential mechanism of the splicing of colonic SPAK. Furthermore with the northern blot analysis (Figure 2B), we found only one transcript present in Caco2-BBE cells (lane 1 and lane 3), while the northern blot with the probe just containing the PAPA box did not show any hybridized band (lane 2).

Figure 2. Colonic SPAK is unusual splice single transcript isoform.

A) Schematic representation of the SPAK gene intron-exon structure. The SPAK gene is composed of 18 exons spanning 184 kb long. In the exon 1 and 7, there are at the same time two unusual splice forms, in both the highly conserved GT nucleotides in the exon become the start of new and unusual intron, and they share the same end of intron nucleotides AG. The blue rectangle represents exons, the digits besides them are the size of it and order of the exon, and the triangles are introns with their respective number. The blue color sequence is the sequence in the exon, the black sequence is the predicted amino acid sequence. The outer black sequence is the related intron sequence start with GT and end with AG. B) Northern blot of the colonic SPAK. Lane 1 and lane 3, Caco2-BBE RNA were probed with probes exists in both colon and non-colon tissue. The lane 2 was probed with fragment of PAPA box which only in the non-colon tissue. The lane in the bottom represents the same loading control with 18 s RNA.

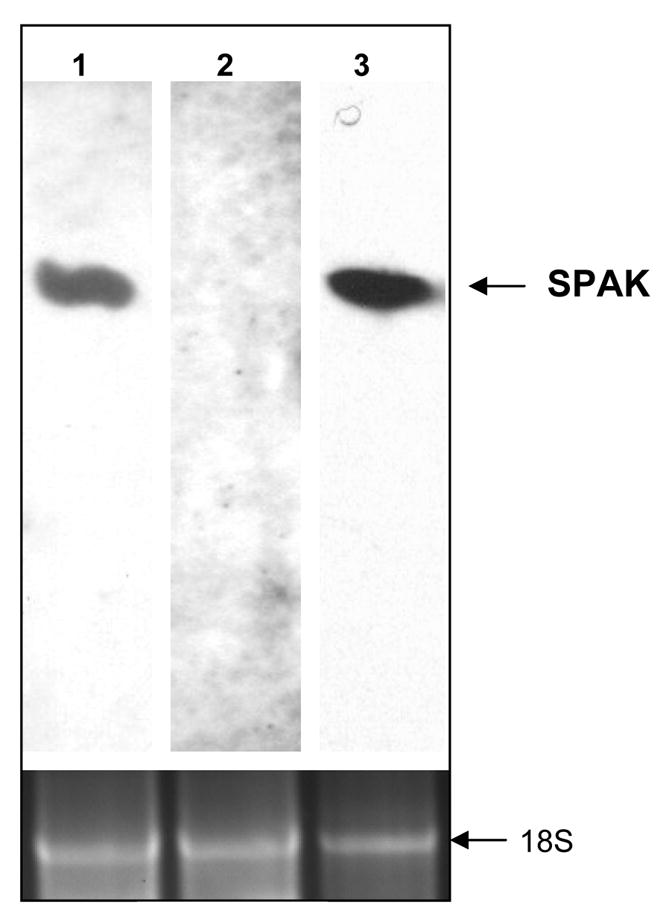

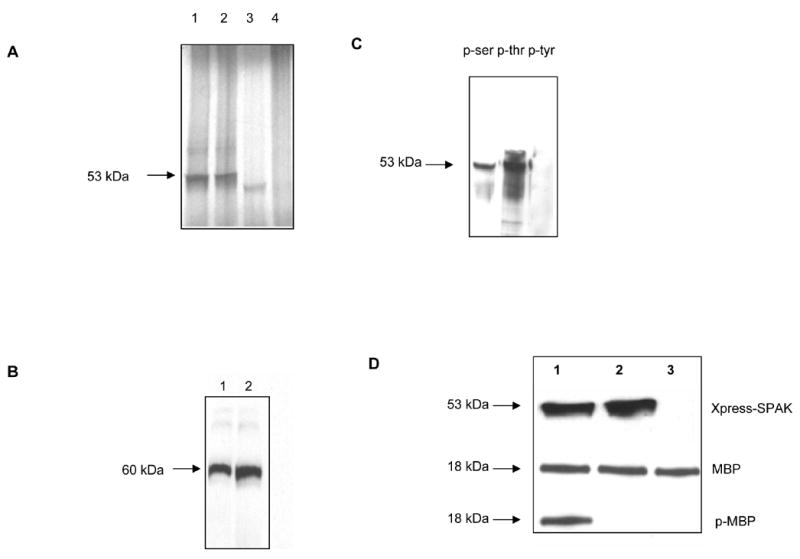

Colonic SPAK isoform possesses serine/threonine kinase activity

Next, we assessed the functionality of SPAK protein. In vitro transcribed/translated SPAK (Figure 3A, lane 1) and kinase-deficient mutant SPAK (Figure 3A, lane 2) could be visualized as a 53 kDa band, whereas expression of the same proteins in Caco2-BBE yielded products with an apparent molecular size of ~60 kDa (Figure 3B). The molecular size difference between SPAK expressed in vitro and SPAK expressed in vivo likely represents different phosphorylation forms of the proteins. We then analyzed whether the SPAK protein had serine/threonine kinase activity. Our kinase assays revealed that immunoprecipitated in vitro transcribed/translated Xpress-tagged SPAK immunoprecipitates could autophosphorylate at ser and thr but not tyr residues (Figure 3C). In addition, immunoprecipitated Xpress-tagged SPAK could phosphorylate the test substrate, myelin basic protein, while the kinase-deficient mutant could not (Figure 3D). The latter observation indicates that the observed kinase activity is directly attributed to SPAK rather than other co-immunoprecipitated molecules.

Figure 3. Colonic SPAK isoform has serine/threonine kinase activity.

A) In vitro transcribed/translated SPAK or kinase-deficient SPAK mutant proteins each had an apparent molecular weight of 53 kDa (lanes 1 and 2, respectively), while no protein was transcribed/translated from the Xpress vector alone (lane 4), lane 3 is the plasmid p38/pcDNA3 as control (43 kDa). B) Caco2-BBE cells expressing Xpress-tagged SPAK (lane 1), Xpress-tagged kinase-deficient SPAK mutant (lane 2) or Xpress vector alone were lysed, total proteins (40 μg/lane) were resolved by 4–20% SDS-PAGE, and blots were immunostained with an anti-Xpress antibody, which revealed an expressed protein with an apparent molecular weight of 60 kDa in Caco2-BBE cells expressing SPAK or kinase-deficient mutant SPAK-like. C) Anti-Xpress antibodies were used to immunoprecipitate in vitro transcribed/translated SPAK-like, the immunoprecipitates were subjected to 4–20% SDS-PAGE, and the blots were immunostained with mouse anti-phospho-ser (lane 1), anti phospho-thr (lane 2) or anti phospho-tyr (lane 3). Bands (~53 kDa) were detected with anti-phosphoser and anti-phospho-thr, but not anti-phospho-tyr, indicating that SPAK has the ability to autophosphorylate at ser and thr but not tyr. D) Protein kinase assays of immunoprecipitated in vitro transcribed/translated SPAK (lane 1), kinase-deficient SPAK (lane 2), or vector control (lane 3) were incubated with MBP for 30 minutes at room temperature and resolved by 4–20% SDS-PAGE. Blots were probed with anti-Xpress (Xpress-SPAK), anti-MBP (MBP) and anti-phosphorylated MBP (p-MBP).

Colonic SPAK isoform activates p38 MAP kinase cascades in intestinal epithelial cells

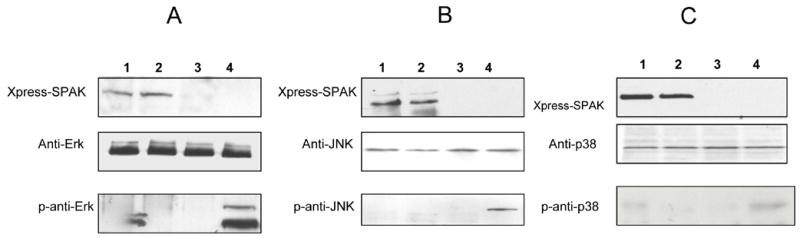

Since many of the Ste20 family members have been shown to activate the JNK/SAPK MAP kinase and/or the p38 MAPK signaling cascades, we analyzed whether SPAK could activate ERK, JNK/SAPK, and p38. Caco2-BBE cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding Xpress-tagged SPAK or the kinase-deficient mutant, and Western blotting was used to examine activation (phosphorylation) of ERK (Figure 4A), JNK (Figure 4B) and p38 (Figure 4C). Our results revealed that Xpress-tagged SPAK did not phosphorylate ERK or JNK. In contrast, p38 was phosphorylated in Caco2-BBE cells expressing Xpress-tagged SPAK-like, but not those expressing the kinase-deficient mutant or vector alone. These findings indicate that SPAK may have the ability to activate p38 MAPK cascades in Caco2-BBE cells.

Figure 4. Colonic SPAK isoform activates p38 MAP kinase signaling in intestinal epithelial cells.

Total proteins from Caco2-BBE cells expressing Xpress-tagged SPAK (lane 1), Xpress-tagged kinase-deficient SPAK (lane 2), Xpress vector alone (lane 3) or relevant positive control treated cells (EGF for Erk, and Il-1 for JNK and p38) (lane 4) were lysed, and total proteins (40 μg/lane) were resolved by 4–20% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were immunostained with antibodies against Xpress (Xpress-SPAK), ERK (ERK), phospho-ERK (p-ERK), JNK (JNK), phospho-JNK (p-JNK), p38 (p38) and phospho-p38 (p-p38).

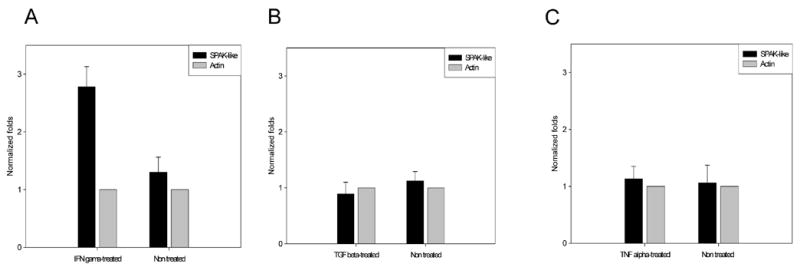

IFN-γ treatment up-regulates colonic SPAK isoform mRNA expression in Caco2-BBE cells

To investigate whether SPAK could be up-regulated in inflamed intestinal epithelial cells, we used real-time RT-PCR to examine the effects of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, IFN-γ (1000U/ml), TGF-β (10 ng/ml) and TNF-α (20 ng/ml), on SPAK mRNA levels in Caco2-BBE cells over 24 h. As shown in Figure 5, ~2.5-fold greater levels of SPAK transcript were observed in IFN-γ-treated cells versus untreated cells, whereas cells treated with TGF-β and TNF-α did not show significant changes in the levels of SPAK transcripts.

Figure 5. IFN-γ can increase SPAK mRNA expression in Caco2-BBE cells.

Caco2-BBE cells were transfected with vectors encoding SPAK-like, and then treated with or without IFN-γ (1000 U/ml), TGF-β (10 ng/ml) or TNF-α (20 ng/ml) for 24 hours. For graphical representation of quantitative PCR data, the raw cycle threshold values (Ct values) obtained from the experimental groups were deducted from the Ct value obtained from the control group using the ΔΔCt method, and the data were normalized using 2−ΔΔCt, with β-actin gene levels serving as the internal standard. Values are normalized as fold-differences relative to transcript levels in the untreated controls. The presented results are representative of three different experiments.

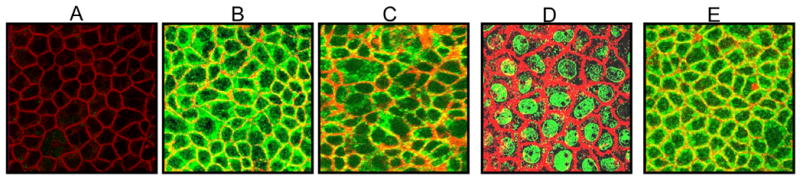

Colonic SPAK isoform can undergo nuclear translocation

Since the predicted SPAK sequence contains a caspase-3 cleavage site and a nuclear localization signal, we investigated the cellular localization of SPAK in Caco2-BBE cells. SPAK and the kinase-deficient mutant were cloned into eukaryotic vectors to generate C-terminal V5- and N-terminal Xpress-tagged proteins (pcDNA3.1/V5 and pcDNA6/Xpress, respectively). Caco2-BBE cells transfected with the various constructs were immunostained with anti-V5 or -Xpress antibodies and examined by confocal microscopy. Control Caco2-BBE cells stained with anti-V5 did not show detectable fluorescence, demonstrating that the V5 antibody does not cross-react with any endogenous epitopes (Figure 6A). Consistent with the known diffuse expression of the V5 epitope, diffuse staining was observed in pcDNA3.1/V5 vector-transfected Caco2-BBE cells (Figure 6B). Caco2-BBE cells expressing pcDNA3.1/SPAK-like/V5 showed positive staining in the cytoplasm and membrane (Figure 6C). To determine whether this indicated localization of the full-length protein or the caspase-3-cleaved C-terminus, we examined the localization of SPAK in Caco2-BBE cells transfected with pcDNA6/Xpress/SPAK-like, wherein the Xpress epitope was fused to the N-terminus. Strong anti-Xpress staining was observed in the nucleus of expressing Caco2-BBE cells (Figure 6D), indicating that the cleaved N-terminal region of SPAK could be translocated to the nucleus. In contrast, Caco2-BBE cells expressing Xpress-tagged kinase-deficient mutant SPAK showed staining in the cytoplasm and membrane (Figure 6E), indicating that the inactive mutant does not undergo nuclear translocation.

Figure 6. Cleaved N-terminal region of Colonic SPAK-isoform can translocate to the nucleus.

Caco2-BBE cells were left untransfected (A), or were transfected with pcDNA3.1/V5 (vector tag alone; B), SPAK-pcDNA3.1/V5 (SPAK fused to a C-terminal V5 tag; C), SPAK-pcDNA6/Xpress (SPAK fused to an N-terminal Xpress tag; D) and kinase-deficient SPAK-pcDNA6/Xpress (kinase-deficient SPAK fused to an N-terminal Xpress tag; E), and then immunostained with anti-V5 (green), anti-Xpress (green), or rhodamine phalloidin (actin, red). The presented images represent horizontal sections (xy) taken from below the apical plasma membrane of transfected polarized Caco2-BBE monolayers.

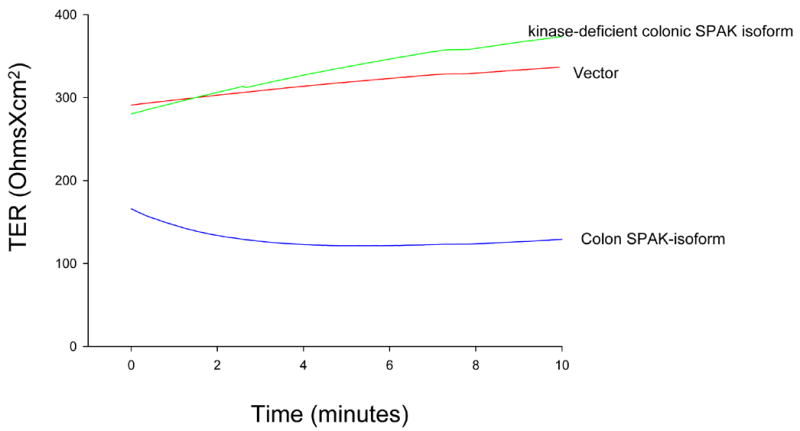

Colonic SPAK isoform over-expression decreases barrier function in intestinal epithelial cells

To investigate the functional role of the SPAK in intact monolayers, Caco2-BBE cells transfected with vectors encoding SPAK or kinase-deficient SPAK, or empty pcDNA6/Xpress vector were grown to confluency on filter, and changes in transepithelial resistance (TER) were monitored. Caco2-BBE cells monolayers that over-expressed SPAK had a significantly lower TER versus control vector-transfected monolayers (120 ± 25 Ohms/cm2 vs. 280 ± 75 Ohms/cm2, respectively). In contrast, kinase-deficient SPAK-like-expressing monolayers showed TER values similar to those of control monolayers (290 ± 22 Ohms/cm2 vs. 280 ± 75 Ohms/cm2, respectively), indicating that the observed decrease in TER requires expression of active SPAK-like.

DISCUSSION

We herein report the cloning and characterization of a Ste20-related protein kinase from inflamed colon tissue. Our analyses revealed that this Ste20-related protein kinase, which was found in Caco2-BBE cells and inflamed and non-inflamed colon tissues but not in the other tested tissues, was a unique isoform of SPAK. Accordingly, we designated this 476 amino acid kinase colonic SPAK. Sequence analysis revealed that SPAK belongs to the GCK IV subfamily, unlike the other SPAK proteins described in human and mouse (SPAK) and rat (PASK), which belong to Ste20 protein Kinases (STK39). The N-terminus of colonic SPAK lacks the PAPA box found in human and mouse SPAK homologs, as well as in the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p57Kip2 (23), and myosin light chain kinase (24). The PAPA box has been implicated in protein-protein interactions, and has been shown to target the myosin light chain kinase to actin (25). In PASK, the conserved C-terminal (CCT) domain can interact with an RFXV (Arg-Phe-Xaa-Val) motif present in the substrate NKCC1, leading to increase of NKCC1 activity (20). The lack of the PAPA box seems to suggest that colonic SPAK may not interact with actin and/or NKCC1 in colonic epithelial cells. Alignment analysis found that this SPAK also misses subdomain IX, which is F helix loop in catalytic domain. The F helix loop, as a signal integration motif (SIM), does not contact substrate or peptide directly but it appears to serve as a conduit to communicate MgATP binding from the active site to the distal peptide-binding site via the Trp-Phe network of interactions and substrate binding. Trp, in particular, stabilizes the activation loop, which is important for ATP and substrate binding, and appears to communicate ATP binding to the peptide binding F-to-G helix loop (26, 27,28). Asp hydrogen in F helix loop bonds to the catalytic loop through the amide hydrogen atoms of Tyr and Arg in the catalytic loop and help F helix loop plays a role in eukaryotic protein kinase signal integration (27, 28). Mutation of the F-helix aspartate to alanine in cAMP protein kinase failed to abolish catalytic activity, suggesting that it fails to play an important catalytic role which suggests a regulatory role for the F-helix aspartate (28, 29). Whether the absence of the F helix loop was always correlating with the absence of the PAPA box is to be defined, coincidently, the recently submitted SPAK sequence to GenBank (accession number XP_001102205) from rhesus monkey is 98% identical in protein level, same as colonic SPAK, STK39 homologous in rhesus monkey does not have PAPA box and F helix loop, showing that the SPAK is highly conserved during the evolution. In another parallel study of regulation of colonic SPAK′s expression and function, primer extension and RACE for the transcription start site also showed single products and sequencing did not show the existence of PAPA box (data not shown).

Consistent with previous findings about SPAK/PASK proteins (31,32,33), colonic SPAK isoform was capable of autophosphorylation at ser and thr but not tyr residues, indicating that colonic SPAK isoform possesses serine/threonine kinase activity. Additional experiments in Caco2-BBE cells revealed that SPAK was capable of activating components in the p38 signaling pathway, but not those of the Erk and JNK pathways. These findings are consistent with previous studies in SPAK protein (33). It means that without PAPA box and F helix loop, SPAK can still have activity, autophosphorylation and phosphorylate the substrate p38, it strongly suggested that F helix loop did not abolish the kinase activity, neither did PAPA box, consistent with Gaqnon et al (30) who found that absence of the PAPA box did not affect SPAK autophosphorylation or transphosphorylation of GST-NKCC1. In addition, it has been reported that mutation of the F-helix failed to abolish catalytic activity, suggesting that it fails to play an important catalytic role (28, 29)

Although the details of SPAK-associated signaling have not yet been elucidated, some components are known. For example, a binding interaction between SPAK and the TNF receptor RELT, a new member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily that is selectively expressed in TNF receptor-expressing hematopoietic tissues, can mediate the activation of p38 and JNK signaling (33). Colonic epithelial cells do not express RELT, suggesting that this receptor does not account for SPAK signaling. Thus, future work will be required to identify the SPAK receptors and signaling molecules in colonic epithelial cells. Many important external inflammatory signals, such as bacterial infection, allergen, cytokines and growth factors, can activate intracellular kinases via binding to transmembrane receptors on responsive cells (33). In addition, cytokines may act intracellularly to increase kinase transcription levels. Consistent with these modes of action, our pro-inflammatory cytokine treatment experiments revealed that IFN-γ, but not TNF-α or TGF-β, stimulated the transcription of SPAK in Caco2-BBE cells. We recently isolated a 5′-flanking fragment containing the promoter region (−1390 to +1 relative to the A of the start ATG) of colonic SPAK isoform (#DQ519080). This promoter region contains Interferon Response Elements (IREs), supporting the notion that IFN-γ may induce transcription of SPAK, and providing additional evidence that SPAK may be involved in epithelial cell signaling during intestinal inflammation.

The nuclear translocation could be explained by the possible cleavage at the putative caspase cleavage site, and to assess the nuclear translocation of the N-terminal fragment, which contained a putative nuclear localization signal in the regulatory domain (RAKKVRR), we transfected Caco2-BBE cells with expression vectors encoding N- or C-terminally tagged SPAK, and examined the resulting localizations of these proteins. Our results suggest that SPAK is cleaved between the catalytic and regulatory domains, possibly at the caspase cleavage site. This cleavage appeared to affect the subcellular localization of SPAK, as the catalytic domain was mostly located in the cytoplasm and membrane, while the regulatory domain was translocated to the nucleus where it might affect gene expression. Furthermore, the kinase-deficient mutant failed to translocate to the nucleus, suggesting that SPAK isoform activity is required for cleavage and translocation.

During intestinal inflammation, multiple kinases function to increase intestinal barrier permeability, leading to decreased intestinal barrier function (34). Over-expression of WNK4, an upstream kinase of SPAK, was shown to increase the permeability of Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cell monolayers (35, 36), suggesting the possible involvement of SPAK in this process. In the present study, we found that over-expression of SPAK decreased the overall membrane permeability of intestinal epithelial cell monolayers, indicating that this protein may be involved in inflammation-associated changes in intestinal barrier function.

In sum, we herein report the cloning and characterization of SPAK, a Ste20-related protein kinase that appears to be specifically expressed in colonic epithelial cells. Our results suggest the following model: in response to external inflammatory signals, SPAK is up-regulated, cleaved and translocated to the nucleus, where it triggers p38 MAP kinase signaling and subsequent changes in gene expression, leading to decreased intestinal barrier permeability. While future studies will be required to assess these possibilities in detail, the present work identifies a potential new intestinal inflammation-associated signaling molecule and provides evidence for its involvement in p38 MAP kinase signaling.

Figure 7. Colonic SPAK-isoform over-expression decreases the barrier function in intestinal epithelium.

TER was measured in Caco2-BBE cells transfected with colonic SPAK-isoform-pcDNA6/Xpress (colonic SPAK isoform), pcDNA6/Xpress vector alone (vector) and kinase-deficient SPAK-like-pcDNA6/Xpress (kinase-deficient colonic SPAK isoform). The trace represents TER values collected at 5s intervals for 10 minutes after a 20 minute equilibrium period, and is representative of six experiments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases under a center grant (R24-DK-064399), RO1-DK061941-02 (to D. Merlin), RO1-DK55850 (S. Sitaraman). Y. Yan is a recipient of a research fellowship award from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Waetzig GH, Seegert D, Rosenstiel P, Nikolaus S, Schreiber S. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is activated and linked to TNF-alpha signaling in inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol. 2002;168:5342–5351. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brigitta MN, Brinkman JB, Telliez AR, Schievella LL, Lin AE, Goldfeld AA. Engagement of Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Receptor 1 Leads to ATF-2- and p38 Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase-dependent TNF- Gene Expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30882–30886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffmeyer A, Grosse-Wilde A, Flory E, Neufeld B, Kunz M, Rapp UR, Ludwig S. Different Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Signaling Pathways Cooperate to Regulate Tumor Necrosis Factor α Gene Expression in T Lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4319–4327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hampe J, Shaw SH, Saiz R, Leysens N, Lantermann A, Mascheretti S, Lynch NJ, MacPherson AJ, Bridger S, van Deventer S, Stokkers P, Morin P, Mirza MM, Forbes A, Lennard-Jones JE, Mathew CG, Curran ME, Schreiber S. Linkage of inflammatory bowel disease to human chromosome 6p. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:647–1655. doi: 10.1086/302677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hugot JP, Laurent-Puig P, Gower-Rousseau C, Olson JM, Lee JC, Beaugerie L, Naom I, Dupas JL, Van Gossum A, Orholm M, Bonaiti-Pellie C, Weissenbach J, Mathew CG, Lennard-Jones JE, Cortot A, Colombel JF, Thomas G. Mapping of a susceptibility locus for Crohn’s disease on chromosome 16. Nature. 1996;379:772–773. doi: 10.1038/379821a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hommes D, van den Blink B, Plasse T, Bartelsman J, Xu C, Macpherson B, Tytgat G, Peppelenbosch M, Van Deventer S. Inhibition of stress-activated MAP kinases induces clinical improvement in moderate to severe Crohn’s disease. Inhibition of stress-activated MAP kinases induces clinical improvement in moderate to severe Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:633–634. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dan I, Watanabe NM, Kusumi A. The Ste20 group kinases as regulators of MAP kinase cascades. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:220–230. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01980-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strange K, Denton J, Nehrke K. Ste20-type kinases: evolutionarily conserved regulators of ion transport and cell volume. hysiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:61–68. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00139.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su YC, Treisman JE, Skolnik EY. The Drosophila Ste20-related kinase misshapen is required for embryonic dorsal closure and acts through a JNK MAPK module on an evolutionarily conserved signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2371–2380. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen W, Yazicioglu M, Cobb MH. Characterization of OSR1, a member of the mammalian Ste20p/germinal center kinase subfamily. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11129–11136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ushiro H, Tsutsumi T, Suzuki K, Kayahara T, Nakano K. Molecular cloning and characteriwation of a novel ste20-related protein kinase enriched in neurons and transporting epithelia. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;355:233–240. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denton J, Nehrke K, Yin X, Morrison R, Strange K. GCK-3, a newly identified Ste20 kinase, binds to and regulates the activity of a cell cycle-dependent ClC anion channel. J Gen Physiol. 2005;125:113–125. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gagnon KB, England R, Delpire E. Characterization of SPAK and OSR1, regulatory kinases of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:689–698. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.2.689-698.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moriguchi T, Urushiyama S, Hisamoto N, Iemura S, Uchida S, Natsume T, Matsumoto K, Shibuya H. WNK1 regulates phosphorylation of cation-chloride-coupled cotransporters via the STE20-related kinases, SPAK and OSR1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42685–42693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowd BF, Forbush B. PASK (proline-alanine-rich STE20-related kinase), a regulatory kinase of the Na-K-Cl co transporter (NKCC1) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27347–27353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piechotta K, Garbarini N, England R, Delpire E. Characterization of the interaction of the stress kinase SPAK with the Na+-K+-2Cl- cotransporter in the nervous system: evidence for a scaffolding role of the kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52848–522856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miao NN, Fung B, Sanchez J, Lydon D, Barker, Pang K. Isolation and expression of PASK, a serine/threonine kinase, during rat embryonic development, with special emphasis on the pancreas. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:11391–1400. doi: 10.1177/002215540004801009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsutsumi H, Ushiro T, Kosaka T, Kayahara K, Nakano K. Proline- and alanine-rich Ste20-related kinase associates with F-actin and translocates from the cytosol to cytoskeleton upon cellular stresses. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9157–9162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vitari AC, Thastrup J, Rafiqi F, Deak M, Morrice NA, Karlsson H, Alessi DR. Functional interactions of the SPAK/OSR1 kinases with their upstream activator WNK1 and downstream substrate NKCC1. Biochem J. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060220. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piechotta K, Lu J, Delpire E. Cation chloride cotransporters interact with the stress-related kinases Ste20-related proline-alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) and oxidative stress response 1 (OSR1) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50812–50819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilks AT. Two putative protein-tyrosine kinases identified by application of the polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:1603–1607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buyse M, Sitaraman SV, Liu X, Bado A, Merlin D. Luminal leptin enhances CD147/MCT-1-mediated uptake of butyrate in the human intestinal cell line Caco2-BBE. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28182–28190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MH, Reynisdottir I, Massague J. Cloning of p57Kip2, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor with unique domain structure and tissue distribution. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:639–649. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank G, Weeds AG. The amino-acid sequence of the alkali light chains of rabbit skeletal-muscle myosin. Eur J Biochem. 1974;44:317–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiao L, Jablonsky PP, Elliott J, Williamson RE. A 170 kDa polypeptide from mung bean shares multiple epitopes with rabbit skeletal myosin and binds ADP-agarose. Cell Biol Int. 1994;18:1035–1047. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1994.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson DA, Akamine P, Radzio-Andzelm E, Madhusudan M, Taylor SS. Dynamics of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2243–2270. doi: 10.1021/cr000226k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madhusudan PA, Wu J, Xuong N, Ten Eyck LF, Taylor SS. Dynamic features of cAMP-dependent protein kinase revealed by apoenzyme crystal structure. J Mol Biol. 2003;327:159–171. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibbs CS, Zoller MJ. Rational scanning mutagenesis of a protein kinase identifies functional regions involved in catalysis and substrate interactions. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8923–8931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson A, Akamine P, Radzio-Andzelm E, Madhusudan M, Taylor SS. Dynamics of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2243–2270. doi: 10.1021/cr000226k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gagnon KB, England R, Delpire E. Characterization of SPAK and OSR1, regulatory kinases of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:689–98. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.2.689-698.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gagnon KG, England R, Delpire E. Volume sensitivity of cation-Cl- cotransporters is modulated by the interaction of two kinases: Ste20-related proline-alanine-rich kinase and WNK4. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C134–1C142. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00037.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vitari AC, Deak M, Morrice NA, Alessi DR. The WNK1 and WNK4 protein kinases that are mutated in Gordon’s hypertension syndrome phosphorylate and activate SPAK and OSR1 protein kinases. Biochem J. 2005;391:17–24. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston AM, Naselli G, Gonez LJ, Martin RM, Harrison LC, DeAizpurua HJ. SPAK, a STE20/SPS1-related kinase that activates the p38 pathway. Oncogene. 2000;19:4290–4297. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polek TC, Talpaz M, Spivak-Kroizman T. The TNF receptor, RELT, binds SPAK and uses it to mediate p38 and JNK activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blair SA, Kane SV, Clayburgh DR, Turner JR. Epithelial myosin light chain kinase expression and activity are upregulated in inflammatory bowel disease. Lab Invest. 2006;86:191–201. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamauchi K, Rai T, Kobayashi K, Sohara E, Suzuki T, Itoh T, Suda S, Hayama A, Sasaki S, Uchida S. Disease-causing mutant WNK4 increases paracellular chloride permeability and phosphorylates claudins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4690–4694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306924101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]