Abstract

The diagnosis of chronic Chagas' disease is generally made by detecting antibodies to Trypanosoma cruzi. Most conventional serological tests are based on lysates of whole parasites or semipurified antigen fractions from T. cruzi epimastigotes grown in culture. The occurrence of inconclusive and false-positive results has been a persistent problem with the conventional assays, and there is no universally accepted gold standard for confirmation of positive test results. We describe here an immunoblot assay for detecting antibodies to T. cruzi in which four chimeric recombinant antigens (rAgs), designated FP3, FP6, FP10, and TcF, are used as target antigens. Each of these rAgs is composed of several antigenically distinct regions and includes repetitive as well as nonrepetitive sequences. Each rAg is coated as a discrete line on a nitrocellulose strip. Assay sensitivity was assessed by testing 345 specimens known to be positive for antibodies to T. cruzi. All 345 of these samples showed two to four reactive test bands in addition to the three on-board control bands that are on each strip. Assay specificity was determined by testing 500 specimens from random U.S. blood donors, all of which gave negative results. Based on the results obtained in this study, we propose the following scheme for interpretation of test results: (i) no bands or a single test band = a negative result; (ii) two or more test bands with at least one band showing intensity of 1+ or higher = a positive result; and (iii) multiple faint test bands (±) = indeterminate result. Based on this scheme, the prototype immunoblot assay showed sensitivity of 100% (n = 345) and specificity of 100% (n = 500). Additionally, all 269 potentially cross-reacting and T. cruzi antibody-negative specimens tested negative in our immunoblot assay. The rAg-based immunoblot assay has potential as a supplemental test for confirming the presence of antibodies to T. cruzi in blood specimens and for identifying false-positive results obtained with other assays.

Trypanosoma cruzi, the protozoan parasite that causes Chagas' disease, or American trypanosomiasis, is endemic in Central and South America as well as in Mexico. Most infected persons, after a mild acute phase, enter the life-long indeterminate phase that is characterized by a lack of symptoms, low parasitemia levels, and antibodies to a variety of T. cruzi antigens. Approximately 10% to 30% of persons with chronic T. cruzi infections, however, develop cardiac or gastrointestinal dysfunction as a consequence of the persistent presence of the parasite. Chemotherapy is parasitologically curative in a substantial proportion of congenitally infected infants and children, but it is largely ineffective in persons with long-standing chronic infections (21). Roughly 25,000 of the estimated 12 million people in the countries in which the infection is endemic who are chronically infected with T. cruzi die of the illness each year, typically due to cardiac rhythm disturbances or congestive heart failure (10).

In areas where T. cruzi is endemic, the parasite is transmitted mainly by blood-sucking triatomine insects. Transmission can also occur by transfusion of blood donated by chronically infected persons, and historically in the countries where the parasite is endemic this route of transmission was important prior to the implementation of blood-screening programs (23). There is no vaccine for preventing transmission of T. cruzi. During the last few decades emigration to the United States from countries where Chagas' disease is endemic has increased markedly. Approximately 13 million such immigrants now live in the United States, and an estimated 80,000 to 120,000 of these persons are infected with T. cruzi (12). Their presence creates a risk of transfusion-related transmission of the parasite in the United States. Five instances of transfusion-related Chagas' disease have already been reported in the United States, and blood bank authorities agree that a much larger number of undiagnosed cases have occurred (14, 28). Currently the U.S. blood supply is not screened for T. cruzi, as no blood-screening assay has been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration. Hence, T. cruzi infection is a threat to the U.S. blood supply. T. cruzi can also be transmitted by transplantation of organs obtained from chronically infected persons. Numerous instances of such transmission have been reported in the countries in which the parasite is endemic, and five cases have occurred in the United States (18, 29).

Laboratory diagnosis of chronic T. cruzi infection is complex. Demonstration of the presence of the parasite by hemoculture or xenodiagnosis is time consuming, insensitive, and expensive. In contrast, serologic assays for antibodies to T. cruzi are well suited for rapid and inexpensive diagnosis of the infection. Conventional tests, such as the indirect hemagglutination assay, indirect immunofluorescence assay, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), are used widely in the countries in which the infection is endemic. Most are based on the use of whole or semipurified antigenic fractions from T. cruzi epimastigotes grown in axenic culture. A persistent problem with the conventional assays has been the occurrence of inconclusive and false-positive results (2, 12, 15). There is no consensus on which parasite antigen preparation is best for detecting antibodies to T. cruzi. The Pan American Health Organization and other expert groups have recommended that donated blood be tested by at least two different methods run in parallel (3, 23). This approach carries with it an enormous logistical and economic burden for blood banks.

There is a compelling need for a supplemental assay for use in clinical laboratories and blood banks. No assay has been uniformly accepted as the gold standard for the serologic diagnosis of T. cruzi infection. PCR-based assays lack the sensitivity necessary for this role (7). The radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA), which is a highly sensitive and specific test with easily interpreted results, was developed nearly two decades ago and has been suggested for use as a confirmatory test in the United States (11). Although the RIPA has been used as a confirmatory assay in more than 20 research projects reported to date (12, 13), its sensitivity and specificity have not been systematically validated. Moreover, the complexity of the RIPA would make its widespread use outside of research settings difficult (15).

Several immunoblot assays based on T. cruzi lysates or recombinant antigens (rAgs) have been described previously (20-22, 27). None of them have been adopted as a confirmatory test, however, and none are available commercially. In this report we describe an immunoblot assay for detecting antibodies to T. cruzi in which four rAgs, designated FP3, FP6, FP10, and TcF, are used as target antigens (8, 9). Each of these rAgs is composed of several distinct domains (Table 1). This assay showed high levels of sensitivity and specificity, and it is potentially suitable for use as a confirmatory test for clinical and blood bank specimens that are borderline or reactive in screening assays.

TABLE 1.

Recombinant antigens used in the Abbott immunoblot assay

| Recombinant antigen and antigenic domain | Descriptione |

|---|---|

| FP10 | |

| SAPAa | Shed acute-phase antigen |

| MAPa | Microtubule-associated protein |

| FP6 | |

| TcR39a | Cytoskeleton-membrane protein |

| FRAb | Flagellar repetitive protein |

| FP3 | |

| TcR27c | Cytoplasmic protein |

| FCaBPd | Flagellar calcium-binding protein |

| TcF | |

| PEP-2b | GDKPSPFQA AA GDKPSPFGQA |

| TcDb | AEPKS AEPKP AEPKS |

| TcEb | KAAIAPA KAAAAPA KAATAPA |

| TcLo1.2b | SSMP S GTSEEGSRGGSSMPA |

N-terminal, repeat, and C-terminal segments included.

Comprised entirely of repeats.

N-terminal and repeat segments included.

Full-length, nonrepetitive protein.

Underlining indicates repetitive sequences reported by others. Italics indicate protein segments fused into the recombinant antigen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Immunostrip preparation.

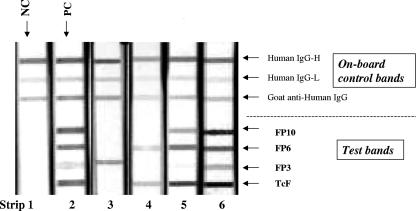

Solutions of human immunoglobulin G (IgG)-high concentration (IgG-H), human IgG-low concentration (IgG-L), and goat anti-human IgG (the three on-board control bands), as well as of FP10, FP6, FP3, and TcF (the four test bands), were jetted onto nitrocellulose membrane sheets (Whatman Schleicher & Schell, Keene, NH) (0.45 micron, 5 by 30 cm) in parallel lines in the relative positions depicted in Fig. 1, strip 6. After drying, the membrane was blocked with 1% casein in phosphate-buffered saline, washed several times in phosphate-buffered saline, and again air dried. As a final step, the membrane sheet was cut into 4-mm-wide strips. The loading of the proteins was adjusted so that the negative-control specimen (strip 1) did not show any test bands and the positive-control specimen (strip 2) showed four test bands whereas in both cases the three control bands were reactive. A panel of reactive samples (strips 3 to 6) showed one to four test bands in addition to the three control bands.

FIG. 1.

Typical results obtained with the Abbott immunoblot assay. Strip 1, negative control, showing three bands in the on-board control section (top); strip 2, T. cruzi antibody-positive control, showing four test bands (bottom) in addition to the three on-board control bands; strips 3 to 6, samples showing one to four test bands in addition to the on-board control bands.

Control specimens.

The negative control was recalcified normal human plasma that tested negative in assays for HBsAg and for antibodies to hepatitis B virus core antigen, hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and human T-cell leukemia virus. The T. cruzi antibody-positive control was from a pool of several plasma units drawn from blood donors diagnosed with Chagas' disease. The positive plasma result was confirmed by several T. cruzi antibody tests, including ELISA-I (a lysate-based test commercially available in Latin America), ELISA-II [an FDA 510(k)-cleared test based on recombinant antigens], and RIPA.

Test procedure.

Positive- and negative-control specimens were included with each run. Previously frozen serum or plasma samples were processed using a microcentrifuge (12,000 rpm, 5 min) in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes prior to testing to remove particulate matter; never-frozen samples were not centrifuged. Diluent (1 ml) and an immunostrip were placed in each trough of an immunoblot reaction tray (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and incubated for 5 min. During each incubation step the contents of the troughs were gently mixed on a rocker. A 20-μl sample was added to each trough containing a strip in diluent and incubated at ambient temperature for 2 h followed by aspiration and three washes with a Tris buffer (pH 8.0 20 mM Tris, 0.15% Tween 20, and 0.1% sodium azide). One milliliter of an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG solution was added to each trough. After a 1-h incubation, each trough was aspirated and washed three times. Following this, 0.7 ml BCIP-Nitro Blue tetrazolium substrate solution (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate-Nitro Blue tetrazolium; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (1 tablet in 20 ml distilled water) was added to each well and incubated at ambient temperature for 10 min for color development. This was followed by aspiration and three washes with distilled water to stop color development. Subsequently, the strips were removed from the troughs and air dried for visual reading. The total assay time was about 4 h.

Interpretation of test results.

T. cruzi antibody reactivity in a test specimen is determined by visual comparison of the intensities of the four test bands with the intensities of the two IgG control bands at the top of the strip, using a scale of 0 to 4+. The reading is defined as 0 when no band is visible, and the intensities of the IgG-L and IgG-H control bands are defined as 1+ and 3+, respectively. With these landmarks in mind, a test band with an intensity result comparable to that seen with the human IgG-L control would be deemed 1+; a band with intensity between that of the IgG-L control and that of the IgG-H control would be rated 2+; a band with intensity comparable to that of the IgG-H control would be judged 3+; and a band intensity higher than that of the IgG-H control would be called 4+. Finally, a faint band with intensity weaker than that of the IgG-L control would be rated ±.

Other serologic assays.

The PRISM Chagas' disease assay was performed as described previously (5, 24) with the cutoff set as the mean chemiluminescence reading (in relative luminescent units) of a negative calibrator + (0.13 × the mean relative luminescent unit reading of a positive calibrator). ELISA-I and ELISA-II were performed as described in the package inserts. The cutoff is set as 0.35 × (the mean A450 reading of a positive control + the mean A450 reading of a negative control) in ELISA-I; and the cutoff is set as the mean A450 reading of a negative control + 0.3 in ELISA-II. The RIPA was carried out as outlined earlier (11, 12), and all RIPA testing was done in blinded fashion.

Chagasic specimens.

A total of 345 T. cruzi antibody-positive human serum or plasma specimens were obtained from the American Red Cross, Antibody Systems (Hurst, TX), BioClinical Partners (Franklin, MA), Biocollections Worldwide, Inc. (Miami, FL), Boston Biomedica, Inc. (West Bridgewater, MA), Goldfinch Diagnostics Inc. (Iowa City, IA), Teragenix Corp. (Ft. Lauderdale, FL), and the Federal University of Bahia (Salvador, Bahia, Brazil). These specimens were came from persons with T. cruzi in most of the Central and South American countries as well as from Mexico and the United States (Table 2). All of the specimens were positive in two or three conventional T. cruzi immunoassays (indirect hemagglutination assay, indirect immunofluorescence assay, and ELISA) and also in the RIPA.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of T. cruzi antibody-positive specimens (n = 345) by country of origin

| Country of origin | No. of samples |

|---|---|

| Argentina | 40 |

| Bolivia | 53 |

| Brazil | 126 |

| Chile | 5 |

| Colombia | 1 |

| Ecuador | 1 |

| El Salvador | 12 |

| Honduras | 4 |

| Mexico | 17 |

| Nicaragua | 16 |

| Surinam | 1 |

| United States | 4a |

| Venezuela | 21 |

| Unknown | 44 |

The blood donors from whom these specimens were obtained were probably Hispanic.

Random donor population.

A total of 500 specimens (sera [n = 150] and EDTA plasma [n = 350]) from randomly selected donors were obtained from the Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center (Houston, TX). These unlinked specimens were collected from random donors, and no specimens were eliminated from this group because of positive results in any of the six routine tests done on donated units. All specimens were tested within 10 days of collection in both the immunoblot assay and the PRISM Chagas' disease assay, which also is currently under development (5). All reactive samples with signal-to-cutoff-ratio (S/CO) values of 0.90 or greater in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay were tested in ELISA-I, ELISA-II, and RIPA.

Potentially problematic specimens.

A total of 271 archived serum or plasma specimens, serologically positive for other diseases or containing potentially interfering substances, were run in the immunoblot assay. This group included specimens from persons with cytomegalovirus infection (n = 4), Epstein-Barr virus infection (n = 14), hepatitis A virus infection (n = 10), helminth or intestinal protozoan infection (n = 5), HIV infection (n = 10), herpes simplex virus infection (n = 15), leprosy (n = 15), rubella (n = 10), syphilis (n = 10), toxoplasmosis (n = 5), tuberculosis (n = 3), Saccharomyces cerevisiae infection (n = 10), varicella-zoster virus infection (n = 10), hemolysis (n = 20), hyper-IgG (n = 10), hyper-IgM (n = 10), hyperbilirubinemia (n = 10), hypertriglyceridemia (n = 15), influenza virus vaccination (n = 15), multiple myeloma (n = 15), multiple sclerosis (n = 5), rheumatoid factor (n = 15), human anti-mouse antibodies (n = 15), systemic lupus erythematosis (n = 11), and leishmaniasis (n = 9). The specimens were purchased from various vendors, including New York Biologicals (New York, NY), ProMedDx (Norton, MA), Boston Biomedica, Inc., and Teragenix. These 271 samples were tested in the immunoblot assay and the prototype PRISM Chagas' disease assay. All specimens that were repeatedly reactive in the latter were tested in the ELISA-I and ELISA-II and then confirmed further with RIPA.

RESULTS

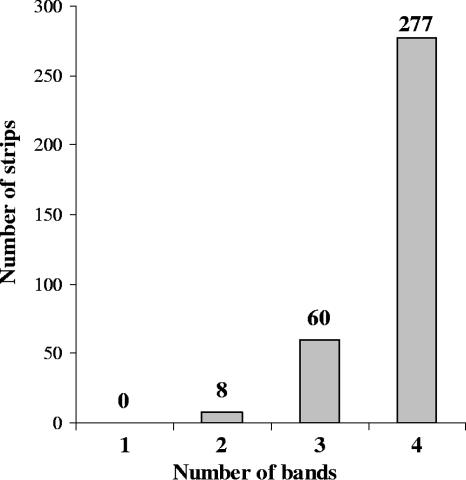

Typical results obtained with the prototype immunoblot assay are shown in Fig. 1, where the locations of the three on-board control bands and the four rAg test bands are clearly evident. All 345 T. cruzi antibody-positive specimens showed two or more test bands in the immunoblot assay, and the distribution in terms of the number of bands that appeared on each strip is shown in Fig. 2. A total of 277 of these specimens showed four test bands, 60 showed three bands, and 8 showed two bands; of note, none showed a single band or was entirely negative. Most test bands with the positive samples showed intensity equal to or higher than that of the IgG-L control band (1+). Moreover, all 345 specimens were reactive in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay and in ELISA-II. In contrast, 6 of the 272 specimens in this group of 345 that were tested in ELISA-I gave negative results, although all 6 had above-baseline S/CO values ranging from 0.60 to 0.89 (Table 3). These discordant samples were confirmed as weak positives in RIPA and showed two or three test bands in the immunoblot assay, with at least one band intensity of 1+ or higher. Due to the lower detection level of ELISA-I observed in testing the first 272 positive specimens, we dropped ELISA-I from further sensitivity comparisons with other assays of newly acquired chagasic samples, although we did continue to use it to cross-check repeatedly reactive samples from the PRISM Chagas' disease assay.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of readings, in terms of the number of positive test bands present, obtained by testing 345 T. cruzi antibody-positive specimens in the Abbott immunoblot assay.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of results obtained by testing six discordant chagasic samples in five assays for antibodies to T. cruzia

| Sample | S/CO

|

No. of test bands present in immunoblot assay | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRISM Chagas' disease assay | ELISA-I (lysate) | ELISA-II (rAg) | ||

| Rag-40218 | 4.40 | 0.66 | 2.62 | 2 |

| Rag-40224 | 3.86 | 0.77 | 3.56 | 3 |

| RR04 | 1.52 | 0.83 | 3.02 | 3 |

| RR52 | 2.07 | 0.83 | 3.56 | 3 |

| RR115 | 1.50 | 0.60 | 3.53 | 2 |

| RR334 | 2.37 | 0.89 | 3.35 | 2 |

All six samples gave weakly positive results in the RIPA. For all samples, the immunoblotting results were interpreted as positive.

The 500 random donor specimens were tested in the immunoblot assay and also in the prototype PRISM Chagas' disease assay. In the immunoblot assay, one specimen gave a single 1+ test band and two others showed a faint (±) test band. None of these samples was reactive in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay or in either of the two ELISAs; hence, they were not sent for RIPA. In view of the negative results obtained with these three specimens in the three comparison assays, the limited reactivity seen in the immunoblot assay would appear to be nonspecific.

Of the 271 specimens with various disease states or potentially interfering substances tested in the immunoblot assay, 265 showed no test bands, 4 gave a single 1+ band, and 2 showed three test bands. The four specimens with a single test band were nonreactive in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay. However, both specimens showing three test bands were also reactive in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay, ELISA-I, and ELISA-II and were confirmed as positive in the RIPA (Table 4). Of note, as shown in the table, three specimens that gave S/CO values above 0.90 in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay were not confirmed by RIPA and showed no test bands in the immunoblot assay.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of results obtained by testing five potentially cross-reacting, discordant specimens in five assays for antibodies to T. cruzi

| Samplea | S/CO

|

RIPA | Immunoblot

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRISM Chagas' disease assay | ELISA-I (lysate) | ELISA-II (rAg) | No. of test bands present | Interpretation | ||

| Protozoan,b 2e03 | 9.55 | 3.02 | 2.82 | Positive | 3 | Positive |

| Leprosy,c 3b10 | 9.96 | 2.36 | 2.92 | Positive | 3 | Positive |

| HAMA, no. 1 | 11.92 | 0.32 | 1.10 | Negative | 0 | Negative |

| HSV-1, no. 2 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.15 | Negative | 0 | Negative |

| HSV-2, no. 4 | 4.01 | 0.65 | 0.26 | Negative | 0 | Negative |

HAMA, human anti-mouse antibodies; HSV-1, herpes simplex virus type 1; HSV-2, herpes simplex virus type 2.

Brazilian donor; tested positive for intestinal protozoan.

Brazilian donor.

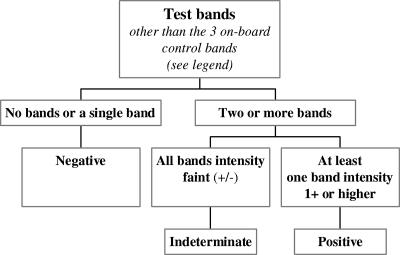

Based on the results obtained by testing these three groups of specimens, which totaled 1,116, we propose the following scheme for interpreting the patterns of test bands that appear on the immunostrips: (i) no band or a single band = a negative result; (ii) two or more bands of which at least one band shows an intensity of 1+ or higher = a positive result; and (iii) multiple faint bands (±) = an indeterminate result (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Algorithm for interpreting readings in the Abbott immunoblot assay. The bands referred to in the chart are the test bands, which are comprised of the recombinant antigens listed in Table 1. For each individual assay to be valid, the three on-board control bands must be present.

When this scheme is applied to the patterns of test bands obtained with the 345 T. cruzi antibody-positive specimens, all are deemed positive, thus giving a sensitivity of 100% (345/345). With the 500 random donor specimens, 497 showed no test bands, two showed a single 1+ band, and 1 showed a faint band (±); thus, all are negative results, and the resolved specificity was 100% (500/500). Finally, based on the proposed interpretation scheme, the immunoblot assay showed a resolved specificity of 100% (269/269) in the 271 specimens with disease states or interfering substances.

During the development of the PRISM Chagas' disease assay (5), we tested approximately 39,000 unlinked serum and plasma specimens from U.S. random donors and archived 19 that were repeatedly reactive or in the gray zone (i.e., showed S/CO values between 0.90 and 0.99). Four specimens in the latter group were reactive in ELISA-I and ELISA-II and were confirmed as positive by RIPA (Table 5). Three of these four specimens showed three or four test bands in the immunoblot assay and thus were interpreted as positive. The fourth specimen in this group, specimen 5060, could not be tested in the immunoblot assay because it was depleted before development of the latter was begun. The remaining 15 PRISM Chagas' disease assay-reactive specimens, most of which had relatively low S/COs, were all negative by RIPA (Table 6). All were negative in ELISA-I; of note, two were reactive and two were in the gray zone in ELISA-II. In the immunoblot assay, 8 of these 15 specimens showed no test bands and the other 7 showed a single band; included among these was specimen 1660, which showed a single FP3 band (strip 3 in Fig. 1). Thus, all 15 were resolved as representing negative results when the interpretation scheme proposed above was applied.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of results obtained by testing six chagasic specimens, identified in U.S. population studies, in five assays for antibodies to T. cruzi

| Sample | S/CO

|

RIPA | Immunoblota

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRISM Chagas' assay | ELISA-I (lysate) | ELISA-II (rAg) | No. of test bands present | Interpretation | ||

| 437 | 10.9 | 3.58 | 2.31 | + | 4 | Positive |

| 5060 | 6.78 | 2.64 | 7.27 | + | NT | NA |

| S2712 | 2.90 | 1.46 | 5.00 | + (weak) | 3 | Positive |

| S108677 | 1.53 | 1.13 | 2.74 | + | 3 | Positive |

| 161 | 7.85 | 2.89 | 8.10 | + | 4 | Positive |

| P91 | 7.92 | 2.53 | 3.20 | + | 4 | Positive |

NT, not tested due to insufficient sample volume. NA, not applicable.

TABLE 6.

Comparison of results obtained by testing 15 specimens that were repeatedly reactive in the PRISM Chagas assay in four other assaysa

| Sample | S/CO

|

Test band present in immunoblot assay | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRISM Chagas' assay | ELISA-I (lysate) | ELISA-II (rAg) | ||

| P1497 | 2.92 | 0.26 | 2.23 | None |

| P1660 | 2.64 | 0.42 | 2.75 | Single FP3 (2+) band |

| P1705 | 1.50 | 0.45 | 0.13 | None |

| P1788 | 1.05 | 0.37 | 0.13 | Single TcF faint (±) band |

| P2171 | 1.66 | 0.47 | 0.14 | None |

| P3881 | 1.61 | 0.23 | 0.12 | Single TcF faint (±) band |

| P6257 | 2.13 | 0.47 | 0.14 | None |

| P6817 | 2.65 | 0.88 | 0.58 | Single FP10 faint (±) band |

| P7087 | 1.00 | 0.29 | 0.14 | Single FP6 faint (±) band |

| P7957 | 2.25 | 0.56 | 0.90 | None |

| P8956 | 0.90 | 0.77 | 0.18 | Single TcF faint (±) band |

| P9026 | 1.12 | 0.42 | 0.16 | None |

| P9228 | 1.81 | 0.24 | 0.17 | None |

| P9807 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.34 | Single FP6 band |

| S108760 | 1.83 | 0.64 | 0.95 | None |

All 15 samples gave negative results in the RIPA. For all samples, the immunoblotting results were interpreted as negative.

Another 2,500 specimens were tested during in early development of the immunoblot assay; two specimens (specimens 161 and P91; Table 5) were identified as positive. These two specimens were reactive in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay, ELISA-I, and ELISA-II; the results were confirmed by RIPA.

DISCUSSION

Serologic testing for specific antibodies to T. cruzi antigens is the most commonly employed approach for diagnosing chronic infection with this protozoan parasite in clinic patients as well as in blood donors. As is the case with many commonly used tests for antibodies to other infectious agents, serological assays for T. cruzi infection occasionally give false-positive, false-negative, and inconclusive results. No assay has been universally accepted as the gold standard for the serologic diagnosis of T. cruzi infection, and likewise no assay is viewed as a definitive confirmatory test. Thus, as mentioned above, there is a persistent need for a supplemental assay that would serve as the second stage of an accurate two-stage process for diagnosing chronic T. cruzi infection.

Immunoblotting has been used successfully as a technical approach for confirming the presence of antibodies to several infectious agents, such as HIV (17), Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme borreliosis) (1), and HCV (25). Although the visual scoring of band intensity in immunoblot assays may be somewhat subjective and may also differ a bit from person to person, assays of this type are widely accepted as confirmatory tools. Immunoblot assays have also been studied as supplemental tests for antibodies to T. cruzi. Some years ago an immunoblot assay based on a T. cruzi protein antigen fraction from epimastigotes bound to a nitrocellulose membrane was proposed as a supplemental test for diagnosis of Chagas' disease (19). A similar role has been proposed for an immunoblot assay based on a trypomastigote excreted-secreted antigen fraction produced in cultures of T. cruzi-infected mammalian cells (4, 27). The biohazard inherent in manipulating cultures of live parasites and the difficulty of producing these complex antigen mixtures with lot-to-lot consistency are major disadvantages of assays based on antigens from culture such as these two. To our knowledge, neither of these assays is being developed commercially.

The use of synthetic peptides and recombinant proteins as target antigens in diagnostic assays such as immunoblotting is an alternative to the use of native antigens. A major advantage of this approach is that with today's technologies, relatively large amounts of these compounds can be produced in highly purified form, and this facilitates the production of testing materials that give consistent performance. General inferences that can be drawn from studies reported to date are that T. cruzi antibody tests based on recombinant proteins can be more specific than those based on mixtures of native antigens derived from parasite lysates and that assays based on an antigenically diverse group of recombinant proteins can have high levels of sensitivity (5, 6, 9, 20, 22, 26).

The use of synthetic peptides and recombinant antigens in strip formats for Chagas' disease diagnosis has been described previously (16, 20, 22). This approach is attractive from a manufacturing perspective, because the antigens can be applied onto a protein-absorbing membrane quickly and in a highly controlled manner. One test in this group that merits comment is the INNO-LIA Chagas' disease antibody assay (20, 22), which consists of seven T. cruzi single-domain test bands on a plastic strip. The fact that only seven distinct recombinant antigens are present on the strip could be a limiting factor in terms of its sensitivity, but at the same time having seven test bands complicates the interpretation protocol.

By contrast, the Abbott immunoblot Chagas' disease assay described here presents 14 distinct antigenic domains, including repetitive as well as nonrepetitive segments, in only four test bands (Table 1). This arrangement holds the potential for markedly reducing the risk of false-negative reactions while at the same time allowing for the simple interpretation scheme presented in Fig. 3. This protocol was developed by analyzing the results obtained by testing in our immunoblot assay the three groups of positive and negative specimens described above. It is noteworthy that these results indicate clearly that reactivity in two test bands is required for a positive interpretation. The adoption of an interpretation scheme in which two reactive test bands are required for confirmation of the presence of anti-T. cruzi antibodies is in line with the interpretation of the Western blots used to confirm HIV (17) and Lyme borreliosis (1) and with the recombinant immunoblot assay for antibodies to HCV (25), all three of which require more than one reactive test band for confirmation of positivity. Despite the fact that visual scoring of band intensity in immunoblot assays may be somewhat subjective and may also differ a bit from person to person, assays of this type are widely accepted as confirmatory tools.

Several aspects of the results obtained with the Abbott immunoblot Chagas' disease assay merit comment. As indicated, in the group of 345 specimens known to be positive for antibodies to T. cruzi the sensitivity of the assay was 100%. This result was particularly noteworthy given the geographic diversity of the specimens (Table 2) and the fact that there was no preselection for high titers. All specimens in this group were reactive in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay and the recombinant ELISA-II, but 6 of the 272 specimens tested in the lysate-based ELISA-I gave negative results. All six gave weak positive results in the RIPA, and these results support the idea that a broad range of reactivity with T. cruzi antigens was present in the group of 345 positives and that the immunoblot assay is capable of detecting low-titer positives.

In the two groups of presumably T. cruzi antibody-negative specimens, the specificity of the immunoblot assay was 100% when the interpretative scheme presented in Fig. 3 was applied. The 500 random donor specimens from Texas, all of which were negative in the immunoblot assay, were also negative in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay and the two ELISAs and thus were not tested in the RIPA. The results obtained by testing the 271 potentially cross-reacting specimens were interesting. Two Brazilian specimens, from a patient with leprosy and a patient with an intestinal protozoan infection, were positive in the immunoblot assay (three test bands) and were also clearly positive in the other assays, including RIPA, thus suggesting that they represent true positives (Table 4). The results obtained with three U.S. specimens in this group merit comment. They were reactive in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay, and one was reactive by ELISA-II, but all were negative in ELISA-I and RIPA. Importantly, none showed any test bands in the immunoblot assay, thus suggesting that the latter is a useful tool for resolving specimens that are discordant in other assays. Overall, the resolved specificity of the immunoblot assay in this challenging group of specimens was 100% (269/269).

Study of a final group of specimens also sheds light on the usefulness of the immunoblot assay as a confirmatory test. As explained above, in previous studies of approximately 42,000 unlinked U.S. random donors, 21 specimens were originally reactive in either the PRISM Chagas' disease assay or the immunoblot assay. Six of the samples in this group were globally positive, and the five for which there was sufficient volume remaining were clearly positive in the immunoblot assay, showing three or four test bands (Table 5). More interesting are the results obtained with the other 15 in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay (Table 6). As shown in that table, all these specimens had relatively low S/CO values in the PRISM Chagas' disease assay and were somewhat reactive but ultimately negative in the ELISA-I. Four of the 15 were reactive in ELISA-II. Importantly, all 15 were negative in the RIPA, and again it merits mention that all RIPA testing was done in blinded fashion. Finally, all 15 were also negative in the immunoblot assay. As is evident in the table, about half of the specimens showed some reactivity, but none gave positive results when the interpretation scheme portrayed in Fig. 3 was applied. Taking into consideration that these 15 specimens were perhaps the most challenging in the total group of 42,000 tested, it is truly impressive that they were all resolved by the immunoblot assay in a manner that was 100% concordant with the results of the RIPA. In conclusion, these findings and those generated by testing the other groups of specimens studied in this project strongly support the concept that the Abbott immunoblot assay holds the promise of fulfilling the need for an accurate test for the serological confirmation of chronic T. cruzi infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roberto Badaró and Eduardo Martins Netto of Bahia University, Bahia, Brazil, for suggestions and for acquiring specimens. We also thank Alla S. Haller and Joshua S. Jarvis for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguero-Rosenfeld, M. E., G. Wang, I. Schwartz, and G. P. Wormser. 2005. Diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:484-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida, I. C., D. T. Covas, L. M. T. Soussumi, and L. R. Travassos. 1997. A highly sensitive and specific chemiluminescent enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of active Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Transfusion 37:850-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. 2002. Control of Chagas disease. Technical report ser. 905. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed]

- 4.Berrizbeitia, M., M. Ndao, J. Bubis, M. Gottschalk, A. Ache, S. Lacouture, M. Medina, and B. J. Ward. 2006. Purified excreted-secreted antigens from Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes as tools for diagnosis of Chagas' disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:291-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, C. D., K. Y. Cheng, L. Jiang, V. A. Salbilla, A. S. Haller, A. W. Yem, J. D. Bryant, L. V. Kirchhoff, D. A. Leiby, G. Schochetman, and D. O. Shah. 2006. Evaluation of a prototype Trypanosoma cruzi antibody assay with recombinant antigens on a fully automated chemiluminescence analyzer for blood donor screening. Transfusion 46:1737-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.da Silveira, J. F., E. Umezawa, and A. O. Luquetti. 2001. Chagas disease: recombinant Trypanosoma cruzi antigens for serological diagnosis. Trends Parasitol. 17:286-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomes, M. L., L. M. C. Galvao, A. M. Macedo, S. D. J. Pena, and E. Chiari. 1999. Chagas' disease diagnosis: comparative analysis of parasitologic, molecular, and serologic methods. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 60:205-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoft, D. F., K. S. Kim, K. Otsu, D. R. Moser, W. J. Yost, J. H. Blumin, J. E. Donelson, and L. V. Kirchhoff. 1989. Trypanosoma cruzi expresses diverse repetitive protein antigens. Infect. Immun. 57:1959-1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houghton, R. L., D. R. Benson, L. D. Reynolds, P. D. McNeill, P. R. Sleath, M. J. Lodes, Y. A. W. Skeiky, D. A. Leiby, and S. G. Reed. 1999. A multi-epitope synthetic peptide and recombinant protein for the detection of antibodies to Trypanosoma cruzi in radioimmunoprecipitation-confirmed and consensus-positive sera. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1226-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirchhoff, L. V. 2006. American trypanosomiasis (Chagas' disease), p. 1082-1094. In R. L. Guerrant, D. H. Walker, and P. F. Weller (ed.), Tropical infectious diseases: principles, pathogens, and practice. Churchill Livingstone, New York, NY.

- 11.Kirchhoff, L. V., A. A. Gam, R. D. Gusmao, R. S. Goldsmith, J. M. Rezende, and A. Rassi. 1987. Increased specificity of serodiagnosis of Chagas' disease by detection of antibody to the 72- and 90-kilodalton glycoproteins of Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Infect. Dis. 155:561-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirchhoff, L. V., P. Paredes, A. Lomeli-Guerrero, M. Paredes-Espinoza, C. Ron-Guerrero, M. Delgado-Mejia, and J. G. Pena-Munoz. 2006. Transfusion-associated Chagas' disease (American trypanosomiasis) in Mexico: implications for transfusion medicine in the United States. Transfusion 46:298-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leiby, D. A., R. M. Herron, Jr., E. J. Read, B. A. Lenes, and R. J. Stumpf. 2002. Trypanosoma cruzi in Los Angeles and Miami blood donors: impact of evolving donor demographics on seroprevalence and implications for transfusion transmission. Transfusion 42:549-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leiby, D. A., B. A. Lenes, M. A. Tibbals, and M. T. Tames-Olmedo. 1999. Prospective evaluation of a patient with Trypanosoma cruzi infection transmitted by transfusion. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:1237-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leiby, D. A., S. Wendel, D. T. Takaoka, R. M. Fachini, L. C. Oliveira, and M. A. Tibbals. 2000. Serologic testing for Trypanosoma cruzi: Comparison of radioimmunoprecipitation assay with commercially available indirect immunofluorescence assay, indirect hemagglutination assay, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:639-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luquetti, A. O., C. Ponce, E. Ponce, J. Esfandiari, A. Schijman, S. Revollo, N. Anez, B. Zingales, R. Ramgel-Aldao, A. Gonzalez, M. J. Levin, E. S. Umezawa, and d. S. Franco. 2003. Chagas' disease diagnosis: a multicentric evaluation of Chagas Stat-Pak, a rapid immunochromatographic assay with recombinant proteins of Trypanosoma cruzi. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 46:265-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maldarelli, F. 2005. Diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus infection, p. 1506-1527. In G. L. Mandell, J. E. Bennett, and R. Dolin (ed.), Principles and practice of infectious diseases. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

- 18.Mascola, L., B. Kubak, S. Radhakrishna, T. Mone, R. Hunter, D. A. Leiby, M. Kuehnert, A. Moore, F. Steurer, G. Lawrence, and H. Kun. 2006. Chagas disease after organ transplantation—Los Angeles, California, 2006. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 55:798-800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendes, R. P., S. Hoshino-Shimuzu, A. M. da Silva, I. Mota, R. A. G. Heredia, A. O. Luquetti, and P. G. Leser. 1997. Serological diagnosis of Chagas' disease: a potential confirmatory assay using preserved protein antigens of Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1829-1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oelemann, W., B. O. Vanderborght, G. C. Verissimo Da Costa, M. G. Teixeira, J. Borges-Pereira, J. A. De Castro, J. R. Coura, E. Stoops, F. Hulstaert, M. Zrein, and J. M. Peralta. 1999. A recombinant peptide antigen line immunoassay optimized for the confirmation of Chagas' disease. Transfusion 39:711-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriques Coura, J., and S. L. de Castro. 2002. A critical review on Chagas disease chemotherapy. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 97:3-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saez-Alquézar, A., E. C. Sabino, N. Salles, D. F. Chamone, F. Hulstaert, H. Pottel, E. Stoops, and M. Zrein. 2000. Serological confirmation of Chagas' disease by a recombinant and peptide antigen line immunoassay: INNO-LIA chagas. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:851-854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmunis, G. A., and J. R. Cruz. 2005. Safety of the blood supply in Latin America. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:12-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah, D. O., and J. Stewart. 2001. Automated panel analyzers: Prism, p. 297-303. In D. Wild (ed.), The immunoassay handbook. Nature Publishing, London, United Kingdom.

- 25.Tobler, L. H., S. R. Lee, S. L. Stramer, J. Peterson, R. Kochesky, K. Watanabe, S. Quan, A. Polito, and M. P. Busch. 2000. Performance of second- and third-generation RIBAs for confirmation of third-generation HCV EIA-reactive blood donations. Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study. Transfusion 40:917-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Umezawa, E. S., S. F. Bastos, J. R. Coura, M. J. Levin, A. Gonzalez, R. Rangel-Aldao, B. Zingales, A. O. Luquetti, and J. F. da Silveira. 2003. An improved serodiagnostic test for Chagas' disease employing a mixture of Trypanosoma cruzi recombinant antigens. Transfusion 43:91-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Umezawa, E. S., M. S. Nascimento, N. Kesper, Jr., J. R. Coura, J. Borges-Pereira, C. V. Junqueira, and M. E. Camargo. 1996. Immunoblot assay using excreted-secreted antigens of Trypanosoma cruzi in serodiagnosis of congenital, acute, and chronic Chagas' disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2143-2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young, C., P. Losikoff, A. Chawla, L. Glasser, and E. Forman. Transfusion-acquired Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Transfusion 2007. 47:540-544. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Zayas, C. F., C. Perlino, A. Caliendo, D. Jackson, E. J. Martinez, P. Tso, T. G. Heffron, J. L. Logan, B. L. Herwaldt, A. C. Moore, F. J. Steurer, C. Bern, and J. H. Maguire. 2002. Chagas disease after organ transplantation—United States, 2001. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:210-212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]