Abstract

Antibodies generated to the purified dengue type 2 virus (D-2V) nonstructural-1 (NS1) protein in mice and rabbits were compared with those generated to this protein in congeneic (H-2 class II) mouse strains and humans after D-2V infections. Unlike the profiles observed with the rabbits, similar antibody reaction profiles were generated by mice and humans with severe D-2V disease (dengue hemorrhagic fever [DHF]/dengue shock syndrome [DSS]). Many of these epitopes contained the core acidic-hydrophobic-basic (tri-amino-acid; ELK-type) motifs present in the positive or negative orientations. Antibody responses generated to these ELK/KLE-type motifs and the epitope LX1 on this protein were influenced by class II molecules in mice during D-2V infections; but these antibodies cross-reacted with human fibrinogen and platelets, as implicated in DHF/DSS pathogenesis. The core LX1 epitope (113YSWKTWG119), identified by the dengue virus complex-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) 3D1.4, was prepared so that it contained natural I-Ad-binding and ELK-type motifs. This AFLX1 peptide, which appropriately displayed the ELK-type and LX1 epitopes in solid-phase immunoassays, generated a similar, but lower, immunodominant anti-ELK-motif antibody reaction in I-Ad-positive mice, as generated in mice and humans during D-2V infections. These antibody responses were much stronger in the high-responding mouse strains and each of the DHF/DSS patients tested and may therefore account for the association of DHF/DSS resistance or susceptibility with particular class II molecules and autoantibodies, antibody-stimulating cytokines (e.g., interleukin-6), and complement product C3a being implicated in DHF/DSS pathogenesis. These results are likely to be important for the design of a safe vaccine against this viral disease and showed the AFLX1 peptide and MAb 3D1.4 to be valuable diagnostic reagents.

The four serotypes of dengue viruses have spread throughout the tropical and subtropical belts of the world, resulting in a globally increased incidence of the severe dengue viral disease dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF; grades I to IV) (14). Cases of DHF are discriminated from cases of classical dengue fever (DF), in which hemorrhage may also occur, by evidence of vascular leakage (hemoconcentration) (29), where DHF grades III and IV (dengue shock syndrome [DSS]) are characterized by narrowed pulse pressures (hypotension) and undetectable pulse pressures (profound shock), respectively (29). Sequential infections with virulent strains of each dengue virus serotype have been implicated in the pathogenesis of DHF/DSS (15). The correlation of disease severity with the levels of markers of immune activation (e.g., interleukin-6 [IL-6], IL-8, tumor necrosis factor alpha, gamma interferon, and the soluble tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor [p75]), together with altered platelet, dendritic cell, monocyte, and T-cell functions (12, 13, 22), strongly implicates inappropriate immune activation in the pathogenesis of DHF/DSS. Clinically graded dengue viral disease severity has also been found to strongly correlate with reductions in platelets and fibrinogen concentrations, with increased concentrations of vasoactive histamine and complement product C3a, and with the localization of antibodies, complement, and fibrinogen on the vascular endothelia of DHF/DSS patients (2). These results therefore strongly implicate autoantibody reactions in the pathogenesis of DHF/DSS. To account for these findings, a mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb), MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3, which reacted with the nonstructural-1 (NS1) proteins of each dengue virus serotype but none of the other flaviviruses tested (6), defined multiple acidic (E or D)-aliphatic/aromatic (G, A, I, L, or V/F, W, or Y)-basic (K or R) (tri-amino-acid) (ELK-type) motifs present in either orientation (ELK/KLE-type motifs) in linear (sequential) epitopes and functional sites (e.g., RGD motifs) on human blood proteins (e.g., fibrinogen) and integrin/adhesion molecules, such as αIIb on platelets, ICAM-1 on endothelial cells, and β3 on both platelets (αIIbβ3) and endothelial cells (αVβ3) (6). Mice immunized with the dengue type 2 virus (D-2V) NS1 protein generated polyclonal antibodies (PAbs) which showed similar anti-ELK/KLE-type motif specificities as MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 against a set of 174 synthetic peptides sequentially spanning the D-2V NS1 protein and also cross-reacted with human fibrinogen, endothelial cells, and platelets (6). The autoantibodies generated to these ELK/KLE-type motifs during human dengue virus infections were therefore hypothesized to form circulating immune complexes with human blood-clotting proteins and to cause pathological effects on human platelets and endothelial cells which could account for the thrombocytopenia and vascular leakage observed during DHF/DSS (6). Cross-reactive antibodies to fibrinogen (and plasminogen) generated in human DHF/DSS patients could not, however, be detected in immunoassays due to cross-reaction of the labeled secondary antibody with this protein and because they were thought to rapidly fix complement in vivo (6, 7). Their reactions were, instead, confirmed by identifying immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG together with the complement proteins C1q and C3 and high concentrations of fibrinogen as well as lower concentrations of plasminogen, but no dengue virus proteins, in DSS patients' high-molecular-weight circulating immune complexes (7). More recently, higher concentrations of IgM and IgG were found on the surface of platelets from DHF/DSS patients than on those from DF patients (26), and DHF/DSS patients' antibodies were shown to cross-react with human endothelial cells (21). The role of these ELK/KLE-type motifs in the pathogenesis of DHF/DSS, however, still needs to be confirmed by comparing the PAb reactions of DF and DHF/DSS patients against the epitopes defined by MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 and mouse PAbs generated to the D-2V NS1 protein, as performed in other studies of microbial molecular mimicry implicated in human autoimmune diseases (23).

Four other MAbs were shown to define the same 9- to 11-amino-acid sequence (epitope LX1) on the NS1 proteins of each dengue virus serotype by using sets of synthetic peptides (11), and these findings were further supported by the results from competition studies (P. R. Young, personal communication). Although the average immunoblot reaction intensities of these four MAbs with the NS1 proteins of each dengue virus serotype and other flaviviruses were shown for brevity (10), one of them showed a different anti-NS1 protein reaction profile within the dengue virus antigenic complex and only some of them weakly cross-reacted with the NS1 proteins of representatives of flavivirus antigenic complex III (e.g., Japanese encephalitis [JE] virus), while none of them reacted with the NS1 proteins of 13 flaviruses from the other antigenic complexes (complexes I, II, IV, VI, VIII, and U) (10). A MAb from this panel which could react equally strongly with the NS1 proteins of each dengue virus serotype, which now cocirculate in many countries (14, 15), without cross-reacting with the NS1 proteins of any other flaviviruses, which may also cocirculate (e.g., JE, West Nile [WN], or yellow fever [YF] virus), would therefore be very useful for the specific detection of dengue viruses.

Antibody responses to the purified D-2V NS1 protein were influenced by H-2 class II molecules in mice, but all of these PAbs cross-reacted with human fibrinogen, endothelial cells, and platelets, as was observed with MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 (6), and human class II molecules (HLAs) were shown to affect resistance or susceptibility to DHF (20, 24). In this study, (i) the individual reactions of the four MAbs which defined the LX1 epitope against the NS1 proteins of each dengue virus serotype and a panel of other flaviviruses as described previously (6, 10) were compared; (ii) mouse H-2 class II molecules were tested for their abilities to influence PAb responses to the LX1 and ELK/KLE-type epitopes on the NS1 protein after repeated D-2V infections; (iii) the cross-reactions of the PAbs generated in step ii with human fibrinogen and platelets were tested; (iv) a peptide containing the LX1 and ELK-type epitopes was designed, and its potential as an inexpensive diagnostic reagent was tested; and (v) the immunodominance of the LX1 and ELK-type epitopes was tested by using PAbs generated in mice, rabbits, and human patients with DF and DSS. The results from these studies could therefore further support the role of anti-ELK/KLE-type epitope autoantibodies in the pathogenesis of DHF/DSS, and knowledge of the role of these autoantibodies may therefore be important for diagnosis and the design of a suitable safe vaccine against this viral disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Flavivirus growth.

The growth of flaviviruses in mammalian fibroblast (Vero) cells was described previously (6, 10, 11). Briefly, representative viruses from flavivirus antigenic complex I (tick-borne encephalitis [TBE; Neudofl] virus), complex III (JE [strain Nakayama], WN [strain E101], St. Louis encephalitis [SLE; strain MSI-7] viruses), complex VII (dengue type 1 virus [D-1V; strain Hawaii 1944], D-2V [strain TR1751], dengue type 3 virus [D-3V; strain H87], and dengue type 4 virus [D-4V; strain Dominica]), and complex U (unassigned) (YF [strain Asibi] virus) were used to infect 70% confluent Vero cell monolayers maintained in medium 199 (M199; M 0650; Sigma) containing 0.18% (wt/vol) NaHCO3, 3.5% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, and antibiotics (virus growth medium). After incubation at 37°C for 4 to 5 days, the supernatants were harvested and replaced with fresh virus growth medium, and the flasks were incubated for a further 3 to 4 days, when a second supernatant harvest was performed. These supernatants were pooled, clarified by centrifugation, and then stored at −80°C. The virus-infected cell monolayers were homogenized with 0.5% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) containing 330 mM phosphoric acid and 0.71% (wt/vol) Trisma base (pH 6.8) (0.1 ml/cm2 of cell monolayer) (cell lysis buffer), before storage at −40°C. Titers of the live D-2V stocks used to infect the mice were determined by plaque assays with Vero cells, as described previously (5).

Purification of the D-2V NS1 protein.

The purification of the native, dimeric form of the D-2V NS1 glycoprotein was described previously (9). Briefly, the clarified supernatants from D-2V (strain TR1751)-infected Vero cells were adjusted to 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM EDTA (TNE buffer) containing 0.02% (wt/vol) NaN3 and a mixture of protease inhibitors (Sigma). These supernatants were then passed through an immunoaffinity column containing MAb 3D1.4. After the mixture was washed with TNE buffer containing protease inhibitors, the bound D-2V NS1 protein was eluted with TNE buffer containing 20 mM diethylamine (pH 11.2), and 0.5-ml fractions were immediately neutralized with 0.1 ml of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.2). The concentration of the D-2V NS1 protein in each fraction was determined by a bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce) with standard bovine serum albumin concentrations.

Production of MAbs and PAbs in mice and rabbits.

The generation of mouse and rabbit PAbs and the production of mouse MAbs were performed under a personal animal procedures license (PIL 70/6903) issued by the Home Office of the United Kingdom. Blood samples from the retroorbital sinus were obtained from mice by using sterile fine-bore Pasteur pipettes after anesthesia with 3% (vol/vol) halothane (Rhone Merieux, Ireland) in oxygen at 1 dm3/min.

The production of mouse MAbs to the D-2V (strain PR159) NS1 protein and their immunoblot reactions with the NS1 proteins of the dengue viruses and other flaviviruses were described previously (6, 10, 11). The mapping of epitopes LD2, 24A, LX1, 24B, and 24C and multiple ELK/KLE-type epitopes on the dengue virus NS1 proteins with 174 overlapping nonapeptide sequences spanning the entire D-2V NS1 protein sequence and peptides containing the corresponding sequences from the NS1 proteins of the other dengue virus serotypes was also described (6, 7, 10, 11). The production of PAbs in outbred Tyler's original and congeneic (H-2 class II) mouse strains and outbred rabbits (New Zealand White) to the purified D-2V NS1 protein was described previously (6, 10). Briefly, outbred Tyler's original or congeneic (B10.G, I-Aq; B10.RIII, I-Ar, I-Er; B10.M, I-Af; B10.S, I-As; C57BL/BJ, I-Ab; B10.BR, I-Ak, I-Ek; B10.A, I-Ak; and B10.D2N: I-Ad, I-Ed) mouse strains (Harlan-Olac, United Kingdom) were immunized by a combination of the subcutaneous (s.c.) and the intraperitoneal (i.p.) routes with 10 μg of the purified dimeric D-2V (strain TR1751) NS1 protein emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant and were boosted 2 weeks later by the same routes and with the same antigen dose contained in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Blood samples were obtained from the retroorbital sinus 2 weeks later, and the sera were stored at −80°C. New Zealand White rabbits were immunized s.c. at multiple sites with a total of 50 μg of the D-2V NS1 protein emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant. Three weeks later, they were boosted by the same route with the same antigen dose emulsified in Freund's incomplete adjuvant. A final immunization with the same antigen dose in PBS was given 3 weeks later by the intramuscular route, 30 to 40 ml of blood was obtained from their marginal ear veins 2 weeks later, and the sera were stored at −80°C.

In this study, 3-week-old mice of the same congeneic mouse strains (see above) (three mice/strain) were infected with 3.2 × 105 PFU of D-2V (strain TR1751) contained in 0.5 ml of virus growth medium by the combined s.c. and i.p. routes and were boosted with the same dose of live D-2V by the same routes 2 weeks later. Blood samples were collected 2 weeks after the first and second infections, and the sera were stored at −80°C.

Serum samples from dengue virus-infected patients.

Paired serum samples from patients classified with DF or DSS by using the WHO guidelines (29) were provided by S. K. Lam from the WHO Virus Reference Laboratory, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Acute secondary dengue virus infections were confirmed by observing high dengue virus-specific IgG antibody titers in these patients' acute-phase serum samples that increased by greater than fourfold in their convalescent-phase serum samples, collected 2 to 14 days later, as determined by using an IgG-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), as described previously (8). D-2V infections were confirmed by virus isolation in C6/36 cell culture and subsequent serotype identification with dengue virus serotype-specific MAbs, as described previously (8).

Immunoassays.

The optimization and use of the indirect ELISAs with the purified D-2V NS1 protein, human fibrinogen, human platelets, human serum albumin, and chicken egg albumin were described previously (6, 7, 10, 11). For these assays, ELISA plates (Immulon 2; Dynatech, United Kingdom) were coated at 10 μg/ml (50 μl/well) with the purified antigens in sodium carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.8). After the plates were washed with PBS, they were blocked with 1% (wt/vol) gelatin in PBS. Serial three- to fourfold dilutions of the mouse MAbs or mouse, rabbit, or human PAbs were prepared in PBS containing 0.02% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (PBS/T; P 1379; Sigma) with 0.25% (wt/vol) gelatin (PBS/T/G), and the plates were incubated at 25°C for 2 h. These plates were then washed with PBS/T; a 1/1,000 dilution of peroxidase-labeled goat anti-human (109-035-088), anti-mouse (115-035-062), or anti-rabbit (111-035-144) IgG (heavy and light chains; Jackson ImmunoResearch) in PBS/T/G was added; and the mixture was incubated at 25°C for 2 h. After the plates were washed with PBS/T, the bound antibodies were detected by the addition of 0.04% (wt/vol) o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (P 1526; Sigma) with 0.003% (vol/vol) H2O2 in citrate/phosphate buffer (pH 5.0) (50 μl/well), the reaction was stopped with 0.2 M H2SO4 (25 μl/well), and the absorbance values were recorded at dual wavelengths of 490 nm and 630 nm (MRX; Dynex).

To purify human platelets, venous blood from a healthy human was collected in 2 mg/ml (wt/vol) sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and centrifuged at 200 × g for 20 min at 25°C, and the platelets were collected from the upper layer. These cells were washed four times in 0.34% (wt/vol) sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid in PBS (pH 7.2) by centrifugation at 1,000 × g and were then added to 96-well plates (3599; Costar) at 1 × 107 cells/well. After treatment of these cells with M199 (pH 7.4) containing 0.02% (wt/vol) NaN3, serial threefold dilutions of mouse sera prepared in M199 (M 0650; Sigma) containing 0.25% gelatin (M199/G) in other 96-well plates were gently transferred to the bound platelets. These plates were then processed as described for the other ELISAs, except that they were gently washed with M199 (pH 7.4) and the second antibody was prepared in M199/G.

The immunoblot (Western blot) assays with nonreduced flavivirus-infected cell lysates were described previously (6, 9, 10). Since no flavivirus group epitopes on the NS1 proteins have been identified by using either MAbs or PAbs (10), the replication of each flavivirus was tested with MAb 4G2 and a pool of human PAbs which reacted with the flavivirus group epitopes on the envelope proteins of these viruses (5, 10). The relative volumes (1 to 8 μl) of each flavivirus-infected cell lysate could then be adjusted to give a similarly high immunoblot color reaction (10). In this way, similar quantities of each flavivirus NS1 protein could be simultaneously analyzed on preparative immunoblot strips with the MAbs or PAbs to ensure that quantitative reaction differences could be appropriately identified (6, 10, 11). These flavivirus-infected cell lysates were heated at 100°C for 3 min in cell lysis buffer (see above) without 2-mercaptoethanol and were subjected to electrophoresis on a 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide resolving gels at 20 mA/gel, electroblotted at 160 mA/gel for 30 min onto 0.2-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membranes, and then processed as described below. For the immunoblot assays with the AFLX1 peptide, 10- and 2.5-μg samples of the peptide were heated at 100°C for 3 min in cell lysis buffer with and without 1% (vol/vol) 2-mercaptoethanol and were subjected to electrophoresis on 15% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide resolving gels at 7 mA/gel. The peptides were then electroblotted onto 0.2-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose (Schleicher & Schuell, Germany) or nylon (Hybond; Amersham, United Kingdom) membranes.

These immunoblot membranes were blocked with 2% milk powder (Marvel; Cadbury's, United Kingdom) in PBS and were then washed with PBS/T. The MAbs and PAbs, diluted to 1/250 to 1/500 and 1/50 to 1/125, respectively, in PBS/T containing 2% milk powder, were then reacted with the membranes at 25°C for 2 h. After the membranes were washed with PBS/T, the peroxidase-labeled second antibody (see above) was reacted with these membranes. After the membranes were washed with PBS/T and then with PBS, the bound antibodies were detected with 0.02% (wt/vol) 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and 0.06% (wt/vol) 4-chloro-1-naphthol (D 5637 and C 8890, respectively; Sigma) containing 0.006% (vol/vol) H2O2 in PBS.

Preparation and use of synthetic peptides.

The preparation and use of synthetic peptides on 60 to 64 nM “pins/gears” (Chiron Mimetopes, United Kingdom) and the preparation of peptides at the 10 to 30 μM scale with a simultaneous (robotic) multiple peptide synthesizer (SMPS 350; Zinsser Analytic, Germany) and their purification were described previously (5, 6, 11). Briefly, overlapping duplicate sets of 9-mer peptides sequentially moving 2-amino-acid residues along the entire sequence of the D-2V (strain PR159S1) NS1 protein, the region spanning the AFLX1 peptide sequence (amino acids 110 to 129), and a set of peptides serially truncated from the amino and carboxyl termini of the LX1 epitope sequence were prepared on polypropylene pins/gears by using activated 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl (Fmoc) amino acid esters (Novabiochem, United Kingdom); the final peptides were acetylated; and the protective groups were removed (see below). These peptides were used in 96-well microtiter plates with 100-μl reagent volumes following the ELISA reaction steps (see above) with MAbs and PAbs diluted to 1/250 to 1/500 and 1/75 to 1/125, respectively. After each ELISA reaction, these peptides were recycled by immersion in disruption buffer (0.1% [wt/vol] SDS in 0.1 M NaHPO4/NaOH [pH 7.2]) at 58°C in an ultrasonic water bath for 20 min before they were washed with hot water (58°C) and boiling methanol. Because the numbers of recycles of these peptide-coated pins/gears were limited, pools of mouse, rabbit, and human DSS patient sera were initially tested. Pools of PAbs rather than individual PAbs generated in congeneic mice were also tested against these peptide-coated pins/gears since the individual serum samples from each group of congeneic mice showed only minor variations either in their ELISA titers against the purified D-2V NS1 protein or in their immunoblot reaction profiles against the NS1 proteins of each dengue virus serotype (6). The reactions of these PAb pools against the LX1 and ELK-type epitopes were then subsequently compared to those obtained with individual serum samples from panels of patients with DF or DSS.

The AFLX1 peptide (amino acids 110 to 129 of the D-2V [strain PR159S1 and TR1751] NS1 protein) was altered from that described previously (6) by the addition of the natural carboxyl-terminal histidine residue. This peptide was prepared at a 20 μM scale on 200- to 400-mesh Fmoc-cysteine (trityl) Wang resin by using Fmoc amino acids activated with o-benzotriazol-1-yl-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate/di-isopropylethylamne and coupled at an eightfold excess. The peptide was then cleaved by using 2% (wt/vol) phenol, 2% (vol/vol) 1,2-ethanedithiol, 2% (vol/vol) H2O, 1.5% (vol/vol) anisole, and 1.2% (vol/vol) triisobutylsilane in trifluoroacetic acid (Fluka, Switzerland). The cleaved peptide was then repeatedly washed in cold peroxide-free diethyl ether (BDH, United Kingdom), pelleted by centrifugation at 250 × g, and finally dried under argon gas. After resuspension in 5 ml of 5% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in H2O, this peptide was purified on a preparative C18 reverse-phase column (Vydac) by using a 5 to 95% (vol/vol) acetonitrile-H2O gradient containing 0.1% (wt/vol) trifluoroacetic acid, the main peak was detected at 215 nm (Beckman System Gold), and the purified peptide was lyophilized.

Structural predictions of D-2V NS1 protein.

The amino acid sequence of the D-2V (strain PR159S1) NS1 protein was analyzed by using eight different computer algorithms (DPM, DSC, GOR4, HNNC, PHD, Predator, SIMPA96, and SOPM), and a consensus structural prediction of the alpha-helix, 310-helix, Pi-helix, β-bridge, extended-strand, β-turn, bend region, random-coil, or ambiguous states was assigned to each amino acid by using the Pole Bio-Informatique Lyonnais database (http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr). The amino acid sequences of the flavivirus NS1 proteins used in this study were obtained from the NCBI database (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

RESULTS

Reactions of mouse MAbs and mouse, rabbit, and human PAbs against flavivirus NS1 glycoproteins.

To identify MAbs which may be useful for the specific diagnosis of dengue virus infections, the reactions of the four MAbs which defined the LX1 epitope (11) and MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3, which defined multiple ELK/KLE-type motifs (6), were compared by using the NS1 proteins of each dengue virus serotype and other flaviviruses, as described previously (10). Some of these flaviviruses (e.g., JE, WN, and YF viruses) cocirculate in areas where dengue virus is endemic. For this study, representatives of flavivirus antigenic complexes I (TBE virus), III (JE, WN, and SLE viruses), VII (D-1V, D-2V, D-3V, and D-4V), and U (YF virus) were chosen. Since no common flavivirus group epitopes have been identified on the NS1 proteins, the replication of each virus was assessed by using MAb 4G2 and human PAbs which defined flavivirus group epitopes on the envelope proteins. By this method, all of these flaviviruses were found to have adequately replicated in the mammalian cells, and therefore, only minor adjustments in these flavivirus-infected cell lysate volumes were required to obtain similar strong immunoblot reactions. This method therefore ensured that high concentrations of each flavivirus NS1 protein were also present on these immunoblot strips (10). In this study, three of the MAbs (MAbs 1A12.3, 3D1.4, and 3A5.4) which defined epitope LX1 reacted with the D-2V NS1 protein in the ELISA in both the nonreduced and the reduced forms and displayed equal immunoblot reaction intensities against the nonreduced NS1 proteins of each dengue virus serotype (Table 1). MAb 4H3.4, which also defined the LX1 epitope, however, displayed an immunoblot reaction profile of D-1V = D-4V > D-2V = D-3V. MAbs 1A12.3, 4H3.4, and 3A5.4, but not MAb 3D1.4, also showed weaker cross-reactions with the NS1 proteins of one or more of the three antigenic complex III viruses tested (JE, WN, and SLE viruses); but none of these MAbs cross-reacted with the NS1 proteins of either the TBE or the YF virus, which are from other flavivirus antigenic complexes, as shown previously (10). In contrast, MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3, which defined multiple ELK/KLE-type motifs on the dengue virus NS1 proteins, displayed a D-2V > D-4V > D-1V > D-3V immunoblot reaction profile (6) and was nonreactive with the NS1 proteins of the other flaviviruses, as shown previously (6). The control MAb (MAb 1H7.4), which defined the LD2 epitope (11), reacted only with the NS1 protein of D-2V among this group of flaviviruses (Table 1). This MAb reaction was, however, abrogated by a reduction of this protein in the ELISA, unlike that observed in immunoblot assays (10, 11).

TABLE 1.

Reactions of MAbs and PAbs generated to the D-2V NS1 with the NS1 proteins of the dengue viruses and other flaviviruses

| Antibodya | Specificityb (epitope) | ELISA titerc against the nonreduced (reduced) D-2V NS1 glycoprotein | Immunoblot reaction against nonreduced flavivirus NS1 glycoproteinsd

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBE virus | JE virus | WN virus | SLE virus | D-1V | D-2V | D-3V | D-4V | YF virus | |||

| MAb | |||||||||||

| 1H7.4 | D-2V NS1 (LD2) | 6.1 (1.3) | +++ | ||||||||

| 1A12.3 | D-1V to D-4V NS1 (LX1) | 3.0 (2.1) | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ||||

| 3D1.4 | D-1V to D-4V NS1 (LX1) | 5.0 (4.1) | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||

| 4H3.4 | D-1V to D-4V NS1 (LX1) | 4.3 (3.4) | + | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | |||

| 3A5.4 | D-1V to D-4V NS1 (LX1) | 5.2 (4.7) | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||

| 1G5.4-A1-C3 | D-1V to D-4V NS1 (MLT) | 5.1 (3.8) | ++ | ++++ | + | +++ | |||||

| PAb | |||||||||||

| Rabbit | D-1V to D-4V NS1 (MLT) | 5.3 (4.4) | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | |

| Mouse | D-1V to D-4V NS1 (MLT) | 4.6 (2.8) | ++ | ++++ | + | +++ | |||||

| Human | D-1V to D-4V NS1 (MLT) | 4.4 (3.3) | + | ++ | ++++ | + | +++ | ||||

MAbs generated to the D-2V NS1 protein or pools of PAbs generated to purified D-2V NS1 protein in outbred mice and rabbits and in human DSS patients during live D-2V infections.

D-2V serotype-specific (D-2V NS1) or dengue virus complex reactive (D-1V to D-4V NS1) anti-dengue virus NS1 protein MAbs with the epitope name (in parentheses) or the reaction of a MAb or PAbs with multiple epitopes (MLT) on the dengue virus NS1 proteins.

The reciprocal log10 t50 against the nonreduced (reduced) D-2V NS1 protein.

Immunoblot (Western blot) reactions against the nonreduced NS1 proteins of TBE virus, JE virus, WN virus, SLE virus, D-1V, D-2V, D-3V, D-4V, and YF virus, gauged by color intensities on an arbitrary scale ranging from negative (blank) to ++++.

The PAbs to the purified D-2V NS1 protein generated in outbred rabbits displayed an immunoblot reaction profile of D-2V = D-4V > D-1V = D-3V and also displayed weak to moderate immunoblot cross-reactions with the NS1 proteins of the JE, WN, and SLE viruses from the antigenic complex III flaviviruses, as well as with that of YF virus. These patterns were therefore unlike any of the MAb reaction patterns with these viruses. The PAbs generated to the purified D-2V NS1 protein by mice and by human DSS patients, however, showed the same virus immunoblot reaction profile (D-2V > D-4V > D-1V > D-3V) to that of MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3. In addition, with the single exception of the weak cross-reaction of the human PAbs with the NS1 protein of JE virus, these mouse and human PAbs were also nonreactive with the NS1 proteins of the JE, WN, and SLE viruses, as observed with MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3. MAb 3D1.4, which defined the LX1 epitope, therefore strongly reacted with the NS1 proteins of each dengue virus serotype but did not react with any of the other flaviviruses. This MAb may therefore be useful for the specific diagnosis of dengue virus infection in areas where these other flaviviruses also cocirculate.

Reactions of mouse, human, and rabbit PAbs generated to the D-2V NS1 protein with linear (sequential) epitopes on this protein.

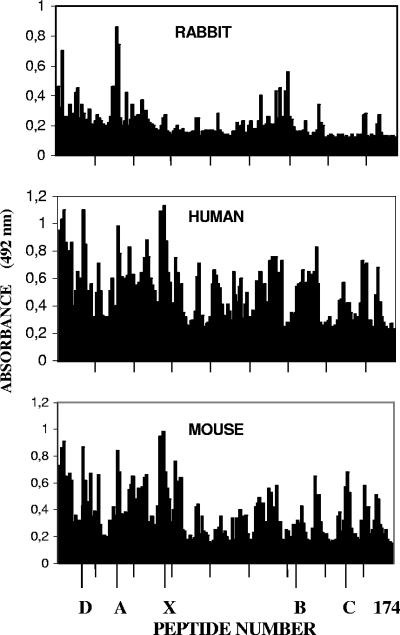

To further compare the profiles of the PAb reaction to the purified D-2V NS1 protein generated in mice, rabbits, and human DSS patients, these PAbs were reacted with 174 overlapping 9-amino-acid peptides sequentially spanning the D-2V (strain PR159S1) NS1 protein sequence (Figure 1). In this study, both the mouse and the human PAbs strongly reacted with many epitopes previously identified by mouse MAbs (6, 7, 11) and showed antipeptide reaction profiles similar to those previously described by the use of MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 (6). The following epitopes and peptides were all strongly identified by both the mouse and human PAbs: epitope LD2 (peptide 13, 25VHTWTEQYK33); epitope 24A (peptide 31, 61TRLENLMWK69); three peptide sequences (peptides 53, 54, and 55, 105RPQPTELRY113, 107QPTELRYSW115, and 109TELRYSWKT117, respectively) that were located immediately amino-terminally to epitope LX1, that contained the ELK-type motif (underlined), and that were previously located by using MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 (6); and three other peptides (peptides 1, 2, and 3, 1DSGCVVSWK9, 3GCVVSWKNK11, and 5VVSWKNKEL13, respectively). These mouse and human PAbs also showed moderately strong reactions against epitope LX1 (peptide 56, 111LRYSWKTWG119). The human PAbs, however, reacted more strongly with other epitopes in the carboxy-terminal region of this protein, such as epitope LX2/1 (peptide 105, 209TWKIEKASF217), epitope LX2/2 (peptide 134, 267PWHLGKLEM275), and epitope LX2/3 (peptide 166, 331YGMEIRPLK339), which also contained ELK/KLE-type motifs (underlined), and epitope 24B (peptide 125, 249GPVSQHNNR257), all of which were defined previously (6, 7). The mouse PAbs, on the other hand, reacted more strongly with epitope 24C (peptides 150 and 151, 299RTTTASGKL307 and 301TTASGKLIT309, respectively) (11) than the human PAbs did. Thus, the mouse and human PAbs generated to the NS1 protein showed reaction profiles in the immunoblot assays (Table 1) and with the 174 overlapping D-2V NS1 peptide sequences (Figure 1) similar to that defined by MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 (6), suggesting that the ELK/KLE-type motifs in the dengue virus NS1 proteins are immunodominant in both mice and humans.

FIG. 1.

Reactions of rabbit, mouse, and human antibodies generated to the D-2V NS1 glycoprotein against 174 overlapping synthetic peptides sequentially spanning the D-2V NS1 protein sequence. Pools of antisera generated to purified D-2V NS1 protein in outbred strains of mice and rabbits or during live D-2V infections in human DSS patients were diluted and reacted with 174 overlapping synthetic (9-amino-acid) peptides sequentially spanning the entire D-2V (strain PR159S1) NS1 protein sequence. The results are expressed as ELISA absorbance (492 nm); the peptides are marked at intervals of 20; and the locations of the linear (sequential) epitopes LD2 (D; peptide 13), 24A (A; peptide 31), LX1 (X; peptides 56 and 57), 24B (B; peptide 125), and 24C (C; peptides 150 and 151) are marked.

In contrast, despite the strong reactions of the rabbit PAbs with the D-2V NS1 protein in the ELISA and the immunoblot assay (Table 1), they displayed much weaker reactions against most of the peptide sequences identified by the mouse or human PAbs (Figure 1). The rabbit PAbs did, however, strongly react with peptide 3 (5VVSWKNKEL13), epitope 24A (peptide 31, 61TRLENLMWK69), and peptide 32 (63LENLMWKQI71).

Antibody responses to the D-2V NS1 protein generated in congeneic mice after infection with live D-2V.

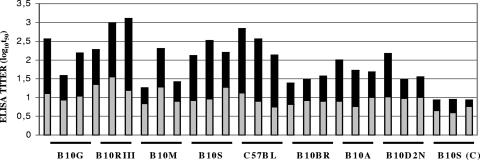

The ELK/KLE-type epitopes appeared to be immunodominant in both the outbred mice and human DSS patients, but unlike those of the outbred mice, these human PAbs were generated to live D-2V infections. The titers of the PAbs to the ELK/KLE-type motifs in mice immunized with the purified D-2V NS1 protein were dependent upon major histocompatibility complex (H-2) class II molecules (6). The ability of these H-2 molecules to also affect the PAb responses to the D-2V NS1 protein during repeated infections with live D-2V in mice was therefore tested. In this study, three mice of each congeneic strain (strain B10.G, I-Aq; strain B10.RIII, I-Ar, I-Er; strain B10.M, I-Af; strain B10.S, I-As; strain C57BL/BJ, I-Ab; strain B10.BR, I-Ak, I-Ek; strain B10.A, I-Ak; and strain B10.D2N, I-Ad, I-Ed) were infected twice with live D-2V and the sera were collected 2 weeks after the first and second infections (Figure 2). When a 50% endpoint ELISA cutoff titer (log10 t50) of 1.0 was applied to each serum sample obtained after the first D-2V infection, only the strain B10.RIII mice were identified to be high responders (for all mice, log10 t50 > 1.0), while the strain B10.BR and B10.A mice were identified to be low responders (for all mice, log10 t50 < 1.0). When a log10 t50 of 2.0 was applied to each serum sample collected after the second D-2V infection, the B10.RIII (I-Ar, I-Er), B10.S (I-As), and C57BL/BJ (I-Ab) mouse strains were identified to be high responders (for all mice, log10 t50 > 2.0), while the B10.BR (I-Ak, I-Ek) and B10.A (I-Ak) mice were again identified to be low responders (for all mice, log10 t50 < 2.0). The antibody responses generated to the D-2V NS1 protein during live D-2V infections were therefore influenced by H-2 class II molecules, and the same high- and low-responder class II haplotypes were identified in response to live D-2V infections as to immunizations with the purified D-2V NS1 protein (6).

FIG. 2.

Antibody responses of congeneic mouse strains to the D-2V NS1 glycoprotein after repeated infections with live D-2V. Three mice of each congeneic strain (strains B10.G, B10.RIII, B10.M, B10.S, C57BL/BJ, B10.BR, B10.A, and B10.D2N) were immunized twice with live D-2V or virus-free medium [B10.S(C) (control)], and the reciprocal log10 t50 values against the nonreduced form of the purified D-2V NS1 protein were determined by using sera collected from each mouse 2 weeks after the first (gray bars) and second (black bars) immunizations. Strains that were high and low responders were identified when the log10 t50 ELISA titers of each mouse/group were >1.0 and 2.0 or <1.0 and 2.0 after the first and second infections, respectively.

Cross-reaction of PAbs generated to live D-2V in congeneic mice with human platelets and fibrinogen.

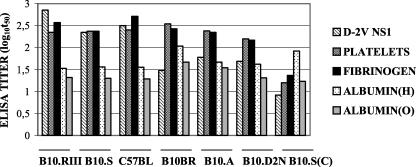

Since MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 and PAbs generated in mice immunized with the purified D-2V NS1 protein cross-reacted with human fibrinogen and integrin/adhesion molecules on human platelets (6), the PAb pools generated in mouse strains that were high (strains B10.RIII, B10.S, and C57BL/BJ), moderate (strains B10.D2N), and low (strains B10.BR and B10.A) responders to the live D-2V infections according to their ELISA titers were also tested against these human antigens (Figure 3). Even though they displayed different ELISA titers against the D-2V NS1 protein, the PAbs from all of these mouse strains had similar ELISA titers against human platelets and fibrinogen, while they only weakly cross-reacted with human serum and chicken egg albumins. The strains that were moderate (strain B10.D2N) and low (strains B10.BR and B10.A) responders therefore generated higher (hetero-specific) ELISA titers against human platelets and fibrinogen than against the D-2V NS1 protein, while antibodies from the control B10.S mice [B10.S(C)] immunized with virus-free growth medium, poorly cross-reacted with these human proteins. Live D-2V infections in mice therefore generated strongly cross-reactive PAbs against epitopes on human fibrinogen and platelets, as was observed after immunizations of mice with the purified D-2V NS1 protein (6) and MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 (6).

FIG. 3.

Cross-reactions of PAbs generated to live D-2V in congeneic mice with human platelets and fibrinogen. The reciprocal log10 t50 values for pools of sera from congeneic mouse strains B10.RIII, B10.S, C57BL/BJ, B10.BR, B10.A, and B10.D2N, infected twice with live D-2V or with virus-free medium [B10.S(C) (control)], against the nonreduced forms of the purified D-2V NS1 protein, human platelets, human fibrinogen, human serum albumin [ALBUMIN (H)], or chicken egg albumin [ALBUMIN (O)] were determined.

Precise mapping of dengue virus complex epitope LX1 on D-2V NS1 protein using mouse MAbs.

Because the four MAbs which defined the LX1 epitope showed different reaction patterns with the NS1 proteins of different flaviviruses (Table 1), precise mapping was performed to identify the minimum core LX1 amino acid sequence that was specifically defined by each of these MAbs. MAbs 1A12.3, 3D1.4, 4H3.4, and 3A5.4, which reacted with peptides 56 and 57 among the 174 overlapping synthetic peptides spanning the D-2V NS1 protein sequence, as reported previously (11), were further tested by using a set of sequential peptides spanning this immunodominant region (amino acids 105 to 129) of the protein and a set of sequentially truncated LX1 peptides (Table 2). In this study, MAbs 4H3.4 and 3A5.4 reacted the most strongly with peptide 56 (111LRYSWKTWG119), while MAbs 1A12.3 and 3D1.4 reacted the most strongly with peptide 57 (113YSWKTWGKA121). In contrast, MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 reacted with peptides 53, 54, and 55, which were also strongly identified by the outbred mice and human DSS patients (Figure 1), each of which contained the 110ELR112 sequence (ELK-type motif) (Table 2). Of these three peptides, peptide 55 (109TELRYSWKT117) was the most strongly identified by this MAb.

TABLE 2.

Precise mapping of the LX1 epitope of the dengue-2 virus NS1 protein with MAbs

| Peptide sequence | ELISA reaction (A492) to MAba:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A12.3 | 3D1.4 | 4H3.4 | 3A5.4 | 1G5.4-A1-C3 | |

| RPQPTELRY | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.15 |

| QPTELRYSW | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.04 |

| TELRYSWKT | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 1.24 |

| LRYSWKTWG | 0.19 | 1.42 | 1.37 | 1.70 | 0.74 |

| YSWKTWGKA | 1.73 | 1.75 | 0.82 | 1.29 | 0.42 |

| WKTWGKAKM | 0.79 | 0.87 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.16 |

| TWGKAKMLS | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| GKAKMLSTE | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| AKMLSTELH | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| YSWKTWGK | 0.14 | 1.09 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.19 |

| YSWKTWG | 0.21 | 2.49 | 2.10 | 1.83 | 0.16 |

| YSWKTW | 0.15 | 1.92 | 0.54 | 1.22 | 0.18 |

| YSWKT | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.14 |

| SWKTWGKA | 0.47 | 1.19 | 0.98 | 1.05 | 0.20 |

| WKTWGKA | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.18 |

| KTWGKA | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.17 |

| TWGKA | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

MAbs, which defined either the LX1 epitope (MAbs 1A12.3, 3D1.4, 4H3.4, and 3A5.4) or multiple ELK/KLE-type motifs (MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3), were diluted to 1/250 to 1/500 and reacted with overlapping synthetic peptides sequentially spanning amino acids 105 to 129 of the D-2V (strains PR159S1 and TR1751) NS1 protein and a set of peptides in which the LX1 epitope (113YSWKTWGKA121) was sequentially truncated. A492 values of >1.00 for each MAb are underlined, and the peak reactions against each overlapping and truncated synthetic peptide set are shown in boldface.

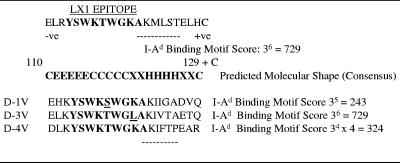

When MAbs 3D1.4, 4H3.4, and 3A5.4 were reacted with a set of sequentially truncated peptides within the 113- to 121-amino-acid sequence, these MAbs showed stronger reactions against the core 7-amino-acid sequence (113YSWKTWG119) than either of the longer peptides (peptides 56 and 57), while MAbs 1A12.3 and 1G5.4-A1-C3 reacted poorly with these truncated peptides. MAb 1A12.3 therefore required the full 9-amino-acid sequence of peptide 57 (113YSWKTWGKA121) for optimal binding. The core 7-amino-acid LX1 sequence (113YSWKTWG119) was conserved in the NS1 proteins of both D-3V and D-4V, but the corresponding NS1 protein sequence of D-1V (113YSWKSWG119) contained a replacement of 116T by S that was shown to be antigenically silent (11) (Figure 4). The corresponding NS1 protein sequences from the TBE (VSWKSWG), JE and WN (MGWKAWG), SLE (YGWKKWG), and YF (YGWKTWG) viruses contained other amino acid substitutions (underlined). The lack of cross-reaction of these mouse MAbs with the NS1 protein of TBE virus was therefore possibly due to the replacement of 113Y by V. The corresponding NS1 sequences of JE and WN viruses were, however, identical. These core 7-amino-acid sequences per se could not therefore account for the weak reaction of MAb 4H3.4 with the NS1 protein of JE virus but not that of WN virus (Table 1). These core 7-amino-acid sequences could also not account for the inability of MAb 4H3.4 to react with the NS1 protein of YF virus but its weak reaction with the NS1 protein of SLE virus, which contained two amino acid substitutions in its sequence, one of which was also present in the NS1 proteins of YF, JE, and WN viruses. In contrast, MAb 3A5.4 showed moderately strong reaction intensities against the NS1 proteins of both JE and WN viruses but not SLE virus, in which amino acid 117T was replaced by the large basic amino acid lysine. Thus, MAb 3A5.4 cross-reacted with the NS1 proteins of JE and WN viruses, while MAb 3D1.4 did not, but both of these MAbs most strongly reacted with the same 7-amino-acid core LX1 epitope sequence.

FIG. 4.

Design of AFLX1 peptide. The AFLX1 peptide contained the 110- to 129-amino-acid sequence of the D-2V (strain PR159S1 and TR1751) NS1 protein, with the LX1 epitope (shown in boldface), the 121AKMLST126 sequence predicted to be an H-2 I-Ad binding motif (cumulative score, >400) (27), a natural glutamic acid (E) (negative [-ve] charge) residue at the amino terminus and natural histidine (H) (positive [+ve] charge), and an unnatural cysteine (C) residue at the carboxy terminus. The molecular shape (C, random coil; H, alpha helix; E, extended strand; X, no consensus), predicted by using a consensus of eight computer algorithms, is shown. The amino acid substitutions which occur within the LX1 epitope from the NS1 proteins of D-1V, D-3V, and D-4V are underlined, and the cumulative I-Ad binding scores in their corresponding 6-amino-acid sequences are shown.

Design of AFLX1 peptide.

The abilities of the LX1 and ELK-type epitopes in this immunodominant region of the protein to be faithfully represented within a synthetic peptide when it was bound in solid-phase immunoassays and to also generate antibody responses in mice when the appropriate H-2 class II (T-helper) epitope was included were tested. For this study, epitope LX1 containing the flanking 6-amino-acid sequence 121AKMLST126 was prepared. The 121AKMLST126 sequence was predicted to strongly bind to the H-2 (class II) I-Ad molecule because of its maximum cumulative amino acid score of 729 (27) (Figure 4). This AFLX1 peptide was capped by a natural glutamic acid (110E) residue at the amino terminus to include the ELR sequence (ELK-type motif) with a natural histidine (129H) and an unnatural cysteine residue at the carboxyl terminus to allow cysteine-bridged dimer formation. By using the consensus results from eight computer algorithms, the LX1 epitope region (111LRYSWKTWG119) was predicted to contain amino acid residues in extended-strand and random-coil arrangements, while the putative I-Ad binding sequence was predicted to be in an alpha-helical conformation. An I-Ad binding motif was also predicted in the corresponding sequence of the D-3V NS1 protein (121AKIVTA126) because of its maximal cumulative score of 729, but such a motif was not predicted for the corresponding sequences of the D-1V and D-4V NS1 proteins (cumulative scores, <400).

Immunoblot (Western blot) assay and ELISA with the AFLX1 peptide.

The ability of the AFLX1 peptide to optimally display the LX1 and ELK-type epitopes was tested in an ELISA and an immunoblot assay. The predicted molecular mass of the AFLX1 peptide was 2.506 kDa, but it could also exist as a cysteine-bridged homodimer. Immunoblot assays showed that this peptide was present in both the monomeric and dimeric forms, and it could more efficiently be detected on nylon membranes rather than on nitrocellulose membranes when it was nonreduced (Figure 5). At optimal nonreduced AFLX1 peptide concentrations of 8 μg for the immunoblot assay and an 8-μg/ml coating concentration determined for the ELISA, the four MAbs which defined epitope LX1 and MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3, which defined ELK-type motifs, all strongly reacted with this peptide in both of these assays (Table 3). MAb 1A12.3, which required the entire 9-amino-acid sequence of peptide 57 for optimal binding (Table 2), uniquely had a slightly higher ELISA titer (4.0 times) against the AFLX1 peptide (log10 t50, 3.6) than the native, dimeric D-2V NS1 protein (log10 t50, 3.0) (Table 3). MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 showed similar titers against both the AFLX1 peptide (log10 t50, 4.9) and the native NS1 protein (log10 t50, 5.1), while the other three MAbs, which defined the core 7-amino-acid LX1 epitope sequence (Table 2), all had slightly lower ELISA titers (3.2 times) against the AFLX1 peptide than the D-2V NS1 protein (Table 3). The control, MAb 1H7.4, which defined epitope LD2, was, as expected, nonreactive with the AFLX1 peptide in the ELISA and the immunoblot assay. Both the LX1 and the ELK-type epitopes were therefore suitably displayed in the AFLX1 peptide when it was bound in both of these solid-phase immunoassays.

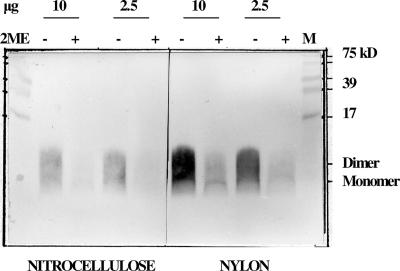

FIG. 5.

Immunoblot of the nonreduced and reduced AFLX1 peptide on nitrocellulose and nylon membranes. Two concentrations (10 and 2.5 μg) of the AFLX1 peptide were nonreduced (lanes −) or reduced (lanes +) with 2-mercaptoethanol (2ME), subjected to 15% (wt/vol) SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, electroblotted onto nitrocellulose or nylon membranes, and detected with MAb 3D1.4. The locations of the monomer (2.5-kDa) and dimer (5.0-kDa) forms of the peptide are shown.

TABLE 3.

Comparative ELISA and immunoblot reactions of mouse MAbs against the purified D-2V NS1 protein and the AFLX1 peptide

| MAb | Epitopea | ELISA titer (log10t50)b

|

Immunoblot reactionc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS1 protein | AFLX1 peptide | NS1 protein | AFLX1 peptide | ||

| 1A12.3 | LX1 | 3.0 | 3.6 | +++ | +++ |

| 3D1.4 | LX1 | 5.0 | 4.5 | +++ | +++ |

| 4H3.4 | LX1 | 4.3 | 3.4 | ++ | ++ |

| 3A5.4 | LX1 | 5.2 | 4.3 | +++ | +++ |

| 1G5.4-A1-C3 | MULTIPLE | 5.1 | 4.9 | +++ | +++ |

| 1H7.4 (control) | LD2 | 6.1 | <1.5 | +++ | |

Epitope name (LD2 or LX1) or reaction with multiple (MULTIPLE) epitopes on the D-2V NS1 protein.

Reciprocal log10 t50 against the purified D-2V NS1 protein and the AFLX1 peptide.

Immunoblot color reaction intensities of the MAbs against the nonreduced forms of the purified D-2V NS1 protein and the AFLX1 peptide, gauged on an arbitrary scale ranging from negative (blank) to +++.

Immunogenicity and antigenicity of the AFLX1 peptide and the epitopes within its sequence.

Since both the LX1 and ELK-type epitopes were adequately exposed in the AFLX1 peptide, their relative immunodominances were compared in congeneic mouse strains. The immunogenicity of this peptide was tested in I-Ad-positive mice, for which the AFLX1 peptide contained a binding motif, and I-As-positive (control) mice. The PAb responses of these mice were then compared by using the same congeneic mouse strains immunized with the purified D-2V NS1 protein or with live D-2V by using the overlapping and truncated sets of peptides used to map the LX1 epitope (Table 2), the AFLX1 peptide, and the purified D-2V NS1 protein. The number of recycles of these peptide-coated pins/gears was, however, limited, and individual serum samples from each group of congeneic mice showed only minor variations in either their ELISA titers against the purified D-2V NS1 protein or their immunoblot reaction profiles against the NS1 proteins of each dengue virus serotype (6). These reactions were therefore performed by using pools of PAbs from these congeneic mice before these PAb and MAb (Table 2) reactions were compared with those of individual serum samples from panels of DF and DSS patients. In this study, strain B10.D2N (I-Ad, I-Ed) and strain B10.S (I-As) mice were immunized with 50 μg of the AFLX1 emulsified in adjuvant and boosted with the same dose. Pools of PAbs from these B10.D2N mice developed a moderately high antibody ELISA titer (log10 t50, 2.9) against the AFLX1 peptide, but they were only weakly reactive against the native, dimeric D-2V NS1 protein (log10 t50, 1.7) (Table 4). Although they were of lower absorbance intensities, the antibody reaction profiles of these B10.D2N mice against the set of overlapping peptides covering the AFLX1 peptide sequence were similar to those generated in the mouse strains that were medium (strain B10.D2N) and high (strain B10.S) responders either to the purified D-2V NS1 protein or to live D-2V infections. The strongest antibody reaction of these mouse PAbs was against peptides 53, 54, and 55, which contained the 110ELR112 (ELK-type motif), with the peak reaction being against peptide 55 (109TELRYSWKT117), as observed with MAb 1G5.4-A1.C3 (Table 2). No reaction against the core LX1 epitope sequence (113YSWKTWG119) was, however, observed by using these B10.D2N mouse PAbs (Table 4). Thus, even though these antibodies generated a high ELISA titer (log10 t50, 2.9) against the AFLX1 peptide in these mice, the antibodies were predominantly not directed against these sequential epitopes within this peptide. In contrast, AFLX1 was nonimmunogenic in the B10.S mice, as well as C57BL/BJ (H-2 class II, I-Ab) mice (data not shown), and, therefore, the I-Ad-binding motif identified in the AFLX1 peptide sequence accounted for its immunogenicity in these B10.D2N (H-2 class II, I-Ad) mice.

TABLE 4.

Antibody reactions generated in congeneic mice to either the AFLX1 peptide, the purified D-2V NS1 protein, or repeated infections with D-2V against overlapping and truncated sets of synthetic peptides within the AFLX1 sequence, the AFLX1 peptide, and the purified D-2V NS1 protein

| AFLX1 peptide sequencea |

A492 for sera from mouse strains immunized with the following immunogenb:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFLX1 peptide

|

D-2V NS1

|

Live D-2V

|

||||

| B10.D2N | B10.S | B10.D2N | B10.S | B10.D2N | B10.S | |

| 110ELRYSWKTWGKAKMLSTELHC | ||||||

| RPQPTELRY | 0.57 | 0.37 | 0.96 | 1.35 | 0.70 | 1.03 |

| QPTELRYSW | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.91 | 1.31 | 0.65 | 0.94 |

| TELRYSWKT | 0.68 | 0.34 | 1.19 | 1.41 | 0.79 | 1.14 |

| LRYSWKTWG | 0.43 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 1.06 | 0.36 | 0.48 |

| YSWKTWGKA | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 0.41 |

| WKTWGKAKM | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.25 | 0.35 |

| TWGKAKMLS | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.53 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| GKAKMLSTE | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.23 |

| AKMLSTELH | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.56 | 0.88 | 0.37 | 0.45 |

| YSWKTWGK | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.72 | 0.28 | 0.34 |

| YSWKTWG | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.43 | 1.26 | 0.35 | 0.68 |

| YSWKTW | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.73 | 0.22 | 0.43 |

| YSWKT | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.64 | 0.18 | 0.22 |

| SWKTWGKA | 0.2 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| WKTWGKA | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.31 |

| KTWGKA | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.37 |

| TWGKA | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.46 | 0.88 | 0.21 | 0.66 |

| Anti-D-2V NS1 ELISA titer (log10t50) | 1.7 | 1.2 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 2.3 |

| Anti-AFLX1 peptide ELISA titer (log10t50) | 2.9 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 2.1 |

| Immunoblot against the AFLX1 peptide | + | ++ | + | |||

Peptide sequences of a set of overlapping 9-amino-acid synthetic peptides sequentially spanning the AFLX1 peptide sequence and a set of sequentially truncated (5- to 8-amino-acid) peptides. The ELK-type motifs are underlined, and the LX1 epitope and the two 9-amino-acid peptides containing the LX1 epitope and the core 7-amino-acid LX1 epitope are shown in boldface.

Pools of sera from congeneic mice (strain B10.D2N, I-Ad; strain B10.S, I-As) immunized with either the AFLX1 peptide, the purified D-2V NS1 protein, or live D-2V were reacted with the sets of synthetic peptides at 1/75 to 1/125 dilutions, the purified D-2V NS1 protein in an ELISA, and the AFLX1 peptide in an ELISA and in an immunoblot assay at 1/50 dilutions. The results with the overlapping and truncated peptides are expressed as A492, values of >1.00 are underlined, and the peak reactions with each of these peptide sets are shown in boldface. The ELISA results are expressed as the reciprocal log10 t50, and the immunoblot color reaction intensities are gauged on an arbitrary scale ranging from negative (blank) to +++ for comparison with the results in Table 5.

B10D2N and B10.S mice immunized with the purified D-2V NS1 protein generated high ELISA titers against the D-2V NS1 protein (log10 t50s, 4.0 and 4.7, respectively), and their peak reactions against peptide 55 (109TELRYSWKT117), which contained the ELK-type motif (underlined) and the core LX1 peptide (113YSWKTWG119), were reflected in their ELISA titers (log10 t50s, 2.4 and 2.9, respectively) and immunoblot reactions (color intensities, + and ++, respectively) against the AFLX1 peptide. Because these B10.D2N mice generated only a weak reaction against the core LX1 epitope (absorbance, 0.43), their antibody reactions against the AFLX1 peptide in the immunoassays were therefore predominantly due to their reaction with the immunodominant ELR sequence (ELK-type motif).

Pools of PAbs from B10D2N and B10.S mice repeatedly infected with live D-2V showed the same peak reactions against peptide 55 and the core LX1 epitope, but the reactions were lower than those generated by the same congeneic mouse strains immunized with the purified D-2V NS1 protein. Thus, these peak antibody reactions of the B10.D2N mice with peptide 55 and the core LX1 epitope sequence were both below an absorbance of 1.0, while only the reaction of the B10.S mouse sera with peptide 55 was above this value. These results were reflected in their lower ELISA titers against the purified D-2V NS1 protein in the ELISA (log10 t50s, 1.7 and 2.3, respectively) and the AFLX1 peptide sequence in both the ELISA (log10 t50s, 1.6 and 2.1, respectively) and the immunoblot assay (color intensities, negative and +, respectively).

The ELK-type motifs present in peptides 53, 54, and 55 were therefore immunodominant in all of these mice. These mouse PAbs and MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 therefore defined the same ELK/KLE-type epitopes that were observed with the PAbs generated in outbred mice to the purified D-2V NS1 protein and in human DSS patients (Figure 1), which probably accounted for their cross-reactions with human fibrinogen and platelets (Figure 3) (6).

Antigenicity of the AFLX1 peptide and the epitopes within its sequence using human PAbs.

To further support the role of anti-ELK/KLE-type antibodies in the pathogenesis of DHF/DSS, quantitative and qualitative differences against these epitopes were tested by using PAb samples from patients with mild (DF) and severe (DSS) disease. In this study, individual serum samples from panels of patients with DF (n = 3) and DSS (n = 3) showed similar reaction profiles, with the strongest reactions being against peptides 53, 54, and 55 and with the peak reaction being against peptide 55 (Table 5), as shown by MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 (Table 2) and the mouse PAbs generated to either the purified D-2V NS1 protein or live D-2V (Table 4). These antibody reactions were, however, stronger in each of the patients with DSS (absorbances, 1.43, 1.49, and 1.72) than DF (absorbances, 0.82, 0.87, and 0.91) (Table 5). In addition, peptides 56 and 57, which contained the LX1 epitope as well as the core LX1 epitope sequence (113YSWKTWG119), were much more strongly identified by the PAbs from each of the DSS patients than by those from the DF patients. These differences were also reflected in their reactions against the purified D-2V NS1 protein in the ELISA (for the DF patients, log10 t50s of 3.5, 3.6, and 3.6; for the DSS patients, log10 t50s of 4.4, 4.6, and 4.6) and against the AFLX1 peptide in both the ELISA (for the DF patients, log10 t50s of 1.6, 1.7, and 1.9; for the DSS patients, log10 t50s of 2.4, 2.6, and 2.8) and the immunoblot assay (all DF patients were immunoblot negative; for the DSS patients, color intensities of ++, ++, and +++).

TABLE 5.

Antibody reactions generated in human patients with DF and DSS against sets of overlapping and truncated synthetic peptides within the AFLX1 sequence, the AFLX1 peptide, and the purified D-2V NS1 protein

| AFLX1 peptide sequencea |

A492 for sera from three patients each withb:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF

|

DSS

|

|||||

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

| 110ELRYSWKTWGKAKMLSTELHC | ||||||

| RPQPTELRY | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 1.13 | 1.25 | 1.45 |

| QPTELRYSW | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 1.11 | 1.21 | 1.48 |

| TELRYSWKT | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 1.43 | 1.49 | 1.72 |

| LRYSWKTWG | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 1.16 | 1.33 |

| YSWKTWGKA | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 1.01 | 1.06 | 1.22 |

| WKTWGKAKM | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 1.02 |

| TWGKAKMLS | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.73 | 0.87 | 0.95 |

| GKAKMLSTE | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 0.83 |

| AKMLSTELH | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.77 | 0.96 | 1.27 |

| YSWKTWGK | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 1.12 |

| YSWKTWG | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.48 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.03 |

| YSWKTW | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.95 |

| YSWKT | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.41 | 0.55 | 0.81 |

| SWKTWGKA | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.95 |

| WKTWGKA | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.97 |

| KTWGKA | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.88 |

| TWGKA | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.54 | 0.87 | 0.64 | 1.05 |

| Anti-D-2V NS1 ELISA titer (log10t50) | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| Anti-AFLX1 peptide ELISA titer (log10t50) | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.8 |

| Immunoblot against the AFLX1 peptide | ++ | ++ | +++ | |||

Peptide sequences of a set of overlapping 9-amino-acid synthetic peptides sequentially spanning the AFLX1 peptide sequence and a set of sequentially truncated (5- to 8-amino-acid) peptides. The ELK-type motifs are underlined, and the two 9-amino-acid peptides containing the LX1 epitope and the core 7-amino-acid LX1 epitope are shown in boldface.

Individual serum samples, obtained 4 to 6 days after the onset of symptoms from patients with either DF (n = 3) or DSS (n = 3), were reacted with the sets of synthetic peptides at 1/75 to 1/125 dilutions, the purified D-2V NS1 protein in an ELISA, and the AFLX1 peptide in an ELISA and an immunoblot assay at 1/50 dilutions. The results with the overlapping and truncated peptides are expressed as A492, values of >1.00 are underlined, and the peak reactions with each of these peptide sets are shown in boldface. The ELISA results are expressed as the reciprocal log10 t50, and the immunoblot color reaction intensities are gauged on an arbitrary scale ranging from negative (blank) to +++.

In conclusion, both mice and humans generated immunodominant antibody responses to the ELK/KLE-type motifs in the D-2V NS1 protein during live D-2V infections, but these were much stronger in each of the patients with DSS than in those with DF.

DISCUSSION

The immunodominance of the ELK/KLE-type epitopes accounted for the similar antibody reaction profiles of MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 and the PAbs generated in mice and humans against peptides spanning the immunodominant region of the D-2V NS1 protein and the D-2V > D-4V > D-1V > D-3V reaction patterns observed against the NS1 proteins of each dengue virus serotype (6, 10). It was previously shown that rabbits, unlike humans and mice, generated antibodies to the carboxy-terminal region of a recombinant D-2V NS1 protein (25). While the rabbit sera used in this study reacted only weakly with some of the short peptide sequences in the carboxy-terminal region of the D-2V NS1 protein sequence, these epitopes may be partially or totally dependent upon the protein conformation. The results from the other study (25) may have, however, accounted for the greater sensitivity of rabbit anti-dengue virus NS1 protein sera in a dengue virus NS1 capture ELISA with mouse MAbs with defined epitopes (e.g., MAbs LD2, 24A, and LX1) at the amino-terminal region of the protein (30) than in the assay with mouse PAbs (1), which would also have reacted with these immunodominant amino-terminal epitopes on the protein. In the latter study (1), increased sensitivity was achieved by using mouse PAbs for both the capture and the detection of the dengue virus NS1 protein. The results from this study, however, suggest that such an assay with either mouse or human PAbs could be used only with patient serum samples, from which the blood-clotting factors, such as fibrinogen, were completely removed. All of the problems of these dengue virus NS1 protein capture assays were, however, readily circumvented by using a simple and sensitive dot blot assay with MAb 3D1.4, coupled with a method to disrupt the patients' immune complexes containing the dengue virus NS1 protein (18). MAb 3D1.4 was unique among the four MAbs which defined the LX1 epitope, since it strongly reacted with the NS1 proteins of each dengue virus serotype, which cocirculate in many countries in the world, but not with the NS1 proteins of any of the three antigenic complex III flaviviruses (e.g., JE, WN, and SLE viruses) tested in this study or with the Murray Valley encephalitis, Usutu, and Kunjin viruses, which are also from this antigenic complex (data not shown). MAb 3D1.4 will therefore be very useful for the specific detection of dengue viruses in areas where these other flaviviruses also cocirculate, preferably by the use of such a simple dot blot assay (18).

Although the dengue virus NS1 protein was not found to be an immunodominant protein during dengue virus infections of humans compared with the immunodominance of other viral proteins (e.g., the main envelope protein [E] and NS3 proteins) in immunoblot assays (3), the antibody responses to the dengue virus NS1 protein were detected during primary dengue virus infections in humans by using isotype-capture ELISAs (28). Similar results were obtained with mice in this study, since the IgG antibody responses generated to the D-2V NS1 protein, particularly in the congeneic mouse strains that were high responders (e.g., strain B10.RIII), could be detected 2 weeks after the primary D-2V infection. Most of these congeneic mouse strains, however, generated much lower titers of antibodies to the D-2V NS1 protein after live D-2V infections than with the purified D-2V NS1 protein administered in adjuvant (6). Strain B10.RIII (I-Ar, I-Er) mice, which possessed both the I-A and the I-E molecules, however, generated a mean antibody ELISA titer to the D-2V NS1 protein after two live D-2V infections that was only eightfold lower (mean log10 t50, 2.8) than that after immunizations with the purified D-2V NS1 protein (mean log10 t50, 3.7) (6). These mice therefore generated particularly high antibody responses to this protein after live D-2V infections, as was found by the use of the DSS patients' PAbs. Further studies are needed to identify whether these results were due to either the I-Ar or the I-Er molecule or to both of these H-2 class II molecules. In contrast, the strain B10.BR (I-Ak, I-Ek) mice, which also possessed both I-A and I-E molecules, generated lower antibody responses to the D-2V NS1 protein after live D-2V infections than the strain B10.A (I-Ak) mice, which expressed only the I-A molecule. While either the I-E or the I-A molecule has been shown to suppress the generation of autoantibodies to different antigens (4, 16), these B10.BR mice still generated highly cross-reactive antibody ELISA titers to the human platelets and fibrinogen after live D-2V infections (Figure 3) or immunizations with the purified D-2V NS1 protein (6). The HLA-DR4 molecule, positively selected in the Latin American populations, was associated with DHF resistance (20), while the HLA-DQ1 molecule provided DHF resistance in Brazilian populations (24). During a large DHF epidemic in Cuba, some diseases known to be associated with particular HLA class II haplotypes, such as bronchial asthma, were identified as DHF risk factors (15). Further studies are therefore needed to confirm these likely HLA class II haplotype associations with DHF/DSS, for which the AFLX1 peptide, which adequately displayed both the ELK-type and LX1 epitopes, may be a useful inexpensive diagnostic antigen.

The reaction of the human and mouse PAbs with the three peptides (amino acids 1 to 9, 3 to 11 and 5 to 13) at the amino terminus of the D-2V NS1 protein was consistent with the report that the amino acid sequence 1DSGCVVSWKNKELKC15 is immunodominant in humans (17). In this study, stronger human and mouse antibody reactions were, however, observed against the three overlapping peptides (peptides 53, 54, and 55) which contained the immunodominant ELR (ELK-type motif). MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3, which defined the ELK/KLE-type motifs, identified similar antipeptide reaction peaks as those of human DSS patients and mice repeatedly infected with D-2V. This MAb produced intraperitoneal hemorrhage in mice and cross-reacted with human fibrinogen, platelets, and endothelial cells (6), while the PAbs to live D-2V infections generated in the mice also cross-reacted with human fibrinogen and platelets. The similar results obtained between the mouse and the human PAbs and MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 are therefore likely to account for the ability of DHF/DSS patients' PAbs to cross-react with human platelets (26) and endothelial cells (21) and the identification of IgG, IgM, and complement proteins with fibrinogen as a major autoantigen in DSS patients' high-molecular-weight circulating immune complexes (2, 7). This would further account for the correlation of clinically graded dengue viral disease severity with the levels of the vasoactive compounds C3a and histamine (2) and the antibody-stimulating cytokine IL-6 (12, 13) and the inverse correlation with the plasma fibrinogen concentrations (2).

While antibodies generated to the purified D-2V NS1 protein cross-reacted with a human endothelial cell line in vitro, their reaction was reduced by a low concentration (50 μg/ml) of human fibrinogen (6). Thus, at the normal blood concentrations of human fibrinogen (1,600 to 4,200 μg/ml) and other blood proteins also containing ELK-type epitopes (6), these cross-reactions with epitopes on human endothelial cell integrin/adhesion molecules (e.g., αVβ3 and ICAM-1) (6) would be dramatically reduced or possibly abrogated. In a subsequent study, PAbs generated to the dengue virus NS1 protein were shown to cross-react with human endothelial cells and to cause apoptosis (21). These reactions were, however, also performed in vitro with human cell lines under nonphysiological conditions. Similarly, while dengue virus infected human endothelial cells and caused damage in vitro, there is no evidence of this type of vascular damage in DHF/DSS patients (2). An animal model is therefore urgently required to more adequately confirm the roles of these autoantibodies in vascular leakage. A model for dengue virus antibody-enhanced disease in vivo was developed in mice. In that model, greater than 100,000 times antibody-enhanced replication of dengue virus was demonstrated (7), and in that model, these immunodominant anti-ELK/KLE-type epitope autoantibodies and other components of inappropriate immune activation implicated in DHF/DSS pathogenesis (2, 12, 13, 15) can be more relevantly studied. The results from these studies therefore suggest that the dengue virus NS1 proteins would be unsuitable for use as a vaccine against the dengue viruses, as originally proposed, and that a suitable live attenuated vaccine or subunit vaccine containing any of the other dengue virus proteins must never generate either autoantibodies to these immunodominant ELK/KLE-type motifs or an antibody-enhanced replication of these viruses (7). Further work is required to assess whether MAb 1G5.4-A1-C3 can generate enhanced disease by enhancing the replication of these viruses in vivo and also differentiate between virulent and less virulent strains of each dengue virus serotype.

Since hetero-specific antibodies to human autoantigens may be generated during dengue virus infections, as shown in this study, antibody reactions to the dengue virus NS1 proteins or the AFLX1 peptide per se may be unsuitable for use for the identification of dengue virus-infected patients during the early acute phase of disease who subsequently develop DHF/DSS. Such an assay was described previously (7) and is being further tested.

Acknowledgments

This work received financial support from the Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Trust and the Instituto Colombiano para el Desarrollo de la Ciencia y la Technologia Francisco Jose de Caldas (COLCIENCIAS) (grant 1215-04-14364).

I thank M. A. Miles (LSH&TM, United Kingdom) and Claudia M. E. Romero-Vivas (Uninorte, Colombia) for helpful advice.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcon, S., A Talarmin, M. Debruyne, A. Falconar, V. Deubel, and M. Flamand. 2002. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay specific to dengue virus type 1 nonstructural protein NS1 reveals circulation of the antigen in the blood during the acute phase of disease in patients experiencing primary or secondary infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:376-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhamarapravati, N. 1997. Pathology of dengue infections, p. 115-132. In D. J. Gubler and G. Kuno (ed.), Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. CAB International, New York, NY.

- 3.Churdboonchart, V., N. Bhamarapravati, S. Peampramprecha, and S. Sirinavin. 1991. Antibodies against dengue viral proteins in primary and secondary dengue hemorrhagic fever. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 44:481-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creech, E. A., D. Nakul-Aguaronne, E. A. Reap, R. L. Cheek, P. A. Wolthusen, P. L. Cohen, and R. A. Eisenburg. 1996. MHC genes modify systemic autoimmune disease. The role of the I-E locus. J. Immunol. 156:812-817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falconar, A. K. I. 1999. Identification of an epitope on the dengue virus membrane (M) protein defined by cross-reactive monoclonal antibodies: design of an improved epitope sequence based on common determinants present in both envelope (E and M) proteins. Arch. Virol. 144:2313-2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falconar, A. K. I. 1997. The dengue virus nonstructural-1 protein (NS1) generates antibodies to common epitopes on human blood clotting, integrin/adhesion proteins and binds to human endothelial cells: potential implications in haemorrhagic fever pathogenesis. Arch. Virol. 142:897-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falconar, A. K. I. 1999. The potential role of antigenic themes in dengue viral pathogenesis, p. 437-447. In S. G. Pandalai (ed.), Recent research developments in virology, vol. 1, part II. Transworld Research Network, Kerala, India. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falconar, A. K. I., E. de Plata, and C. M. E. Romero-Vivas. 2006. Altered enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay immunoglobulin M (IgM)/IgG optical density ratios can correctly classify all primary and secondary dengue virus infections 1 day after the onset of symptoms, when all of these viruses can be isolated. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13:1044-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falconar, A. K. I., and P. R. Young. 1990. Immunoaffinity purification of the native dimer forms of the flavivirus non-structural protein, NS1. J. Virol. Methods 30:323-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falconar, A. K. I., and P. R. Young. 1991. Production of dimer-specific and dengue group cross-reactive mouse monoclonal antibodies to the dengue 2 virus nonstructural glycoprotein. J. Gen. Virol. 72:961-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falconar, A. K. I., P. R. Young, and M. A. Miles. 1994. Precise location of sequential dengue virus subcomplex and complex B cell epitopes on the nonstructural-1 glycoprotein. Arch. Virol. 137:315-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink, J., F. Gu, and S. G. Vasudevan. 2006. Role of T cells, cytokines and antibody in dengue fever and dengue haemorrhagic fever. Rev. Med. Virol. 16:263-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green, S., and A. Rothman. 2006. Immunopathological mechanisms in dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 19:429-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gubler, D. J. 1998. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:480-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halstead, S. B. 1997. Epidemiology of dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever, p. 23-44. In D. J. Gubler and G. Kuno (ed.), Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. CAB International, New York, NY.

- 16.Hanley, G. A., J. Schiffenbauer, and E. S. Sobel. 1997. Class II haplotype differentially regulates immune response in HgCl2-treated mice. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 84:328-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, J.-H., J.-J. Wey, Y.-C. Sun, C. Chin, L.-C. Chien, and Y.-C. Wu. 1999. Antibody responses to an immunodominant synthetic peptide in patients with dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever. J. Med. Virol. 57:1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koraka, P., C. P. Burghoorn-Mass, A. Falconar, T. E. Setiati, K. Djamiatun, J. Groen, and A. D. Osterhaus. 2003. Detection of immune-complex-dissociated nonstructural-1 antigen in patients with acute dengue virus infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4154-4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurane, I., and F. A. Ennis. 1997. Immunopathogenesis of virus infection, p. 273-290. In D. J. Gubler and G. Kuno (ed.), Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. CAB International, New York, NY.

- 20.LaFleur, C., J. Granados, G. Vargas-Alarcon, J. Ruiz-Morales, C. Villarreal-Garza, L. Higuera, G. Hernadez-Pacheco, T. Cutido-Moguel, H. Rancel, R. Figueroa, M. Acosta, E. Lazcono, and C. Ramos. 2002. HLA-DR antigen frequencies in Mexican patients with dengue virus infection: HLA-DR4 as a possible genetic resistance factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever. Hum. Immunol. 63:1039-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin, C.-F., H.-Y. Lei, A.-L. Shiau, C.-C. Liu, H.-S. Liu, T.-M. Yeh, S.-H. Chen, and Y.-S. Lin. 2003. Antibodies from dengue patient sera cross-react with endothelial cells and induce damage. J. Med. Virol. 69:82-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mongkolsapaya, J., W. Dejnirattisai, X. N. Xu, S. Vasanawathana, N. Tangthawornchaikul, A. Chairunsri, S. Sawasdivorn, T. Duangchinda, T. Dong, S. Rowland-Jones, O. T. Yenchitsomanus, A. McMichael, P. Malasit, and G. Screaton. 2003. Original antigenic sin and apoptosis in the pathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Nat. Med. 9:820-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oldstone, M. B. 2005. Molecular mimicry, microbial infection, and autoimmune disease: evolution of the concept. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 296:1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polizer, J. R., D. Bueno, J. E. Visentainer, A. M. Sell, S. D. Borelli, L. T. Tsuneto, M. M. Dalalio, M. T. Coimbra, and R. A. Moliterno. 2004. Association of human leukocyte antigen DQ1 and dengue fever in a white Southern Brazilian population. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 99:559-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Putnak, J. R., P. C. Charles, R. Padmanabhan, K. Irie, C. H. Hoke, and D. S. Burke. 1988. Functional and antigenic domains of the dengue-2 virus non-structural glycoprotein NS1. Virology 163:93-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saito, M., K. Oishi, S. Inoue, E. M. Dimaano, M. T. Alera, A. M. Robles, B. D. Estrella, Jr., A. Kuamtori, K. Moji, M. T. Alonzo, C. C. Buerano, R. R. Matias, F. F. Natividad, and T. Nagatake. 2004. Association of increased platelet-associated immunoglobulins with thrombocytopenia and the severity of disease in secondary dengue virus infections. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 138:299-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sette, A., S. Buus, E. Appella, J. A. Smith, R. Chestnut, C. Miles, S. M. Colon, and H. M. Grey. 1989. Prediction of major histocompatibility complex binding regions of protein antigens by sequence pattern analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3296-3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shu, P.-Y., L.-K. Chen, S.-F. Chang, Y.-Y. Yueh, L. Chow, L.-J. Chien, C. Chin, T.-H. Lin, and J.-H. Huang. 2000. Dengue NS1-specific antibody responses: isotype distribution and serotyping in patients with dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever. J. Med. Virol. 62:224-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. 1997. Dengue haemorrhagic fever: diagnosis, treatment, and control, 2nd ed. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 30.Young, P. R., P. A. Hilditch, C. Bletchly, and W. Halloran. 2000. An antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reveals high levels of the dengue virus protein NS1 in the sera of infected patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1053-1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]