Abstract

We used Drosophila melanogaster macrophage-like Schneider 2 (S2) cells as a model to study cell-mediated innate immunity against infection by the opportunistic fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Transcriptional profiling of S2 cells coincubated with C. albicans cells revealed up-regulation of several genes. One of the most highly up-regulated genes during this interaction is the D. melanogaster translational regulator 4E-BP encoded by the Thor gene. Analysis of Drosophila 4E-BPnull mutant survival upon infection with C. albicans showed that 4E-BP plays an important role in host defense, suggesting a role for translational control in the D. melanogaster response to C. albicans infection.

Candida albicans is a part of normal microbial flora that can be found in mucocutaneous surfaces of the oral cavities, gastrointestinal tracts, and vaginas of many mammals, including humans. Although C. albicans does not normally cause severe disease in immunocompetent hosts, this pathogen can trigger life-threatening systemic infections in immunocompromised individuals. Mammals respond to C. albicans infection through activating both acquired and innate immune responses (3, 30), with the innate immune response as the first defense. Since the innate immune response is evolutionarily highly conserved, Drosophila melanogaster is a promising system for studying virulence characteristics of medically important pathogens such as C. albicans (7, 32). The Drosophila immune response is composed of both humoral and cellular components (2). The innate immune system consists of two major networks defined by the Imd (immune deficiency) and Toll pathways that are activated by fungal and bacterial infections (7). These pathways initiate humoral antimicrobial defenses in the Drosophila fat body, the analog to a mammalian liver. The cellular immune response involves plasmatocytes (blood cells) that can phagocytose microbes and encapsulate parasites; transcription activation of a variety of pathways is necessary for these responses.

In eukaryotes, regulation of gene expression at the translational level is a very complex process. It allows for very rapid adaptive changes in global protein synthesis levels and for selective mRNA translation during the regulation of the cell cycle, development, apoptosis, the response to cell proliferation conditions, and cellular stress conditions, such as infection. During translation initiation, the 40S preinitiation complex is recruited to mRNA by interactions with the cap-binding complex eIF4F (eukaryotic initiation factor 4F). The eIF4F complex consists of 3 subunits: eIF4E, the cap binding protein; eIF4A, a RNA helicase; and eIF4G, a scaffolding protein.

The activity of eIF4E is regulated by the eIF4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs). These repressor proteins inhibit cap-dependent translation by preventing the association of eIF4E with eIF4G and thereby suppressing the formation of the cap-binding complex. The binding of 4E-BPs to eIF4E is modulated by the phosphorylation status of the 4E-BPs at several serine and threonine residues. Under active growth conditions, 4E-BPs are hyperphosphorylated, remain dissociated from eIF4E, and are inactive in blocking cap-dependent translation. However, under conditions that block cell proliferation or induce apoptosis, hypophosphorylated 4E-BPs sequester eIF4E and inhibit cap-dependent, but not cap-independent, translation (9, 13, 15, 34).

Recent studies have shown that Drosophila has a single d4E-BP (21), in contrast to mammals, which express three distinct 4E-BP proteins (24, 26). Drosophila 4E-BP is an effector of cell growth (21). The phosphorylation of d4E-BP is stimulated by insulin via the conserved insulin receptor (dInR-PI3K-Akt-TSC-dTOR) pathway. In starved Drosophila S2 cells, most of the d4E-BP consists of the nonphosphorylated isoform (α), which is active in binding deIF4E. Treatment with insulin induces a shift to another isoform (β), hyperphosphorylated at Thr37 and Thr46, which causes d4E-BP dissociation from deIF4E (20).

Among the first-line defense players of the innate immune system are the macrophages, which can phagocytose pathogens. In the present work, we used S2 cells, which share many characteristics with mammalian macrophage cells, to study pathogen-host interactions. It was recently described by Stroschein-Stevenson et al. (32) that S2 cells engulf C. albicans as early as 30 min after they encounter each other. We showed that phagocytosis of C. albicans cells induces differential expression of immune response genes. Microarray analysis of the host-pathogen interaction identified several genes involved in innate response to C. albicans infection, including Thor, which encodes d4E-BP. Subsequently, we investigated the importance of d4E-BP in vivo and observed an increased sensitivity of d4E-BPnull flies to Candida infection. Our data suggest that d4E-BP is important for fly survival after Candida infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast, bacterial, and Drosophila strains and cell lines.

The C. albicans strains used in this study were SC5314 (12) and CAI4-GFP, expressing a soluble intracellular green fluorescent protein (GFP) (ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 pAM5.6) (2, 10). These strains were grown in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, 0.05% uridine, pH 5.5) or SD-ura (0.15% dropout uracil, 0.05% uridine, 0.67% yeast nitrogen, 2% dextrose) media, respectively. Drosophila Schneider 2 (S2) cells (Invitrogen) were grown in Schneider's media (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (S-10 medium) according to the supplier's specifications (ATCC). The d4E-BPnull (Thor2), revertant (Thor1Rv1), and Oregon-R wild-type flies are as described previously (5, 6, 33). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain used was MLY40 (17).

Time-lapse microscopy.

The day before introducing the fungal cells, 106 Drosophila S2 cells were seeded in a Bioptechs petri dish. S2 cells were then incubated with live or 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed Candida cells or with 3.53-μm latex beads (Estapor Microspheres). Phase-contrast as well as epifluorescence pictures were taken at a ×400 magnification every 15 min with a DMIRE2 inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems Canada) equipped with a Hamamatsu cooled charge-coupled-device camera, a Bioptechs temperature-controlled stage adapter, and a Ludl motorized stage. Openlab software (Improvision) was used for image acquisition.

Immunofluorescence.

Drosophila S2 cells (107) were seeded in six-well plates (Becton-Dickinson), and Candida cells (strain CAI4-GFP) were added at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. At the indicated incubation time, cells were washed two times in S-10 medium and stained with an anti-Candida antibody as previously described (29), except the secondary antibody was a Rhodamine red-X-conjugated F(ab)′2 donkey anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA) diluted 1:200 in S-10. Epifluorescence was monitored using the appropriate filters, at ×400 magnification.

Total RNA and mRNA extractions.

Total RNA was extracted by the hot phenol extraction method (8). mRNA isolation was performed using the Micro-FastTrack mRNA isolation kit from Invitrogen according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Microarrays.

The microarrays used in this study were purchased from the Drosophila Microarray Center (d12k v1) (23). Transcription profiles for each condition represent the average of at least 4 to 9 independent hybridizations. These include dye swap hybridizations (Cy3/Cy5 and Cy5/Cy3) from at least three independently produced RNA preparations. The DNA microarray slides were scanned with a ScanArray 5000 scanner (version 2.11; GSI Lumonics, then Packard BioScience, now Perkin Elmer-Cetus, Wellesley, CA) at a 10-μm resolution. Quantitation and normalization of DNA microarrays were performed as described previously (22). The resulting 16-bit TIFF files were quantified with QuantArray software (versions 2.0 and 3.0; Perkin Elmer-Cetus). Statistical analysis and visualization were performed with GeneSpring software (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA) as described previously (22).

Northern blot analyses.

The Northern blot analyses were performed as described previously (18). Probes for d4E-BP and RpL4 genes were synthesized as follows. Fragments from the d4E-BP (Thor) gene were amplified by PCR using a forward primer, 5′-TGGGGACGGGCACGCACTTG-3′, and a reverse primer, 5′-GTGGTCCCCTGGTGGTCT-3′. The RpL4 probe was used as an internal control to monitor RNA loading and transfer. Fragments for the RpL4 gene were amplified using a forward primer, 5′-GGCGGCGACCTTCTTCTT-3′, and a reverse primer, 5′-GTGTGCCGACAGCTAGGATT-3′.

Antibodies and Western blot analyses.

Anti-d4E-BP was a generous gift from N. Sonenberg (21). Anti-phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Anti-actin antibodies were obtained from Chemicon/Millipore.

Protein extracts (50 μg) were loaded on a 15% acrylamide gel, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) for Western blot analysis. Membranes were incubated with anti-d4E-BP primary antibody (1:2,000) in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 plus 5% bovine serum albumin or with a 1:2,000 dilution of anti-actin monoclonal antibody, followed by a 1:2,000 dilution of anti-rabbit or anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated immunoglobulin G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The proteins were detected using Lumi-Light Western blotting substrate (Roche).

Drosophila infection.

Infection of flies (1- to 3-day-old virgin females or males; 30 per experimental group) was performed as described previously (16) with a thin needle dipped in a concentrated cell pellet containing 200 optical density of the yeast cells used in our study. The inoculum size was evaluated at approximately 103 cells per fly. Following infection, flies were maintained at 25°C on regular fly medium. Infection experiments were performed at least three independent times, and standard deviations were calculated.

RESULTS

Phagocytosis of Candida albicans by S2 cells.

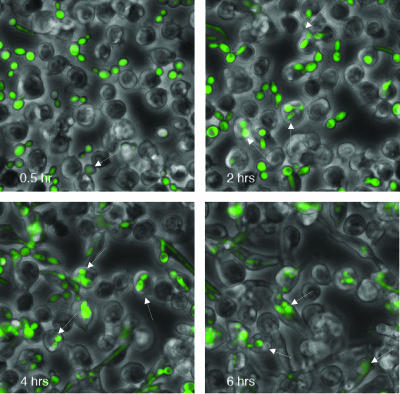

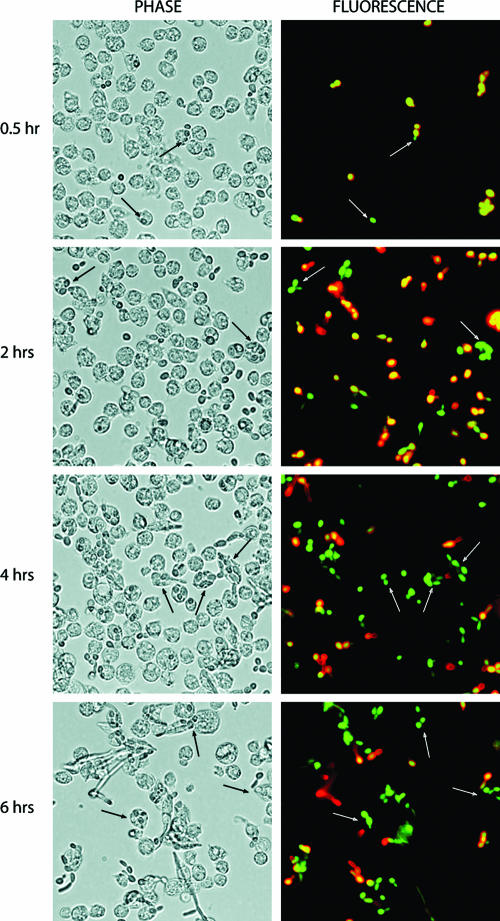

Drosophila plasmatocytes are responsible for the phagocytosis and destruction of apoptotic cells and microorganisms (11, 19). The plasmatocytes share several properties with mammalian macrophages at the structural and molecular levels (1, 25). In this study, we used S2 cells to analyze cell-mediated innate immunity and phagocytosis. This cell line, which is derived from Drosophila embryos, expresses macrophage-like genes (croquemort, dSR-CI, and PGRP-LC) and possesses macrophage-like phagocytic properties (25, 28, 32). The goal of the present work was to analyze the effect of the internalized Candida on S2 cells. To establish whether S2 cells phagocytize C. albicans, we monitored the internalization of GFP-labeled C. albicans CAI4 cells (CAI4-GFP) in coincubation experiments with S2 cells for up to 6 h (Fig. 1). The results indicated that C. albicans cells were indeed engulfed by S2 cells. We also took a double-labeling approach to distinguish between C. albicans cells internalized versus attached to the surface. Figure 2 shows that Candida cells associated with S2 cells are efficiently internalized, with the percentage of engulfed Candida increasing with the incubation time. It is noteworthy that S2 cells are loosely adherent and many cells are lost during the immunofluorescence procedure.

FIG. 1.

Interaction of Drosophila S2 cells with Candida strain CAI4-GFP. Drosophila S2 cells were incubated at 25°C with Candida at an MOI of 1 and monitored by time-lapse microscopy at ×400 magnification for the indicated times (bottom left, in hours). Arrows point to representative Candida cells engulfed by the S2 cells.

FIG. 2.

Phagocytosis of Candida strain CAI4-GFP by Drosophila S2 cells. Drosophila S2 cells were incubated at 25°C with Candida CAI4-GFP at an MOI of 1 for the indicated time. They were then stained with an anti-Candida polyclonal antibody (in red), as described in Materials and Methods. Engulfed Candida, protected from primary antibody binding, remained green, whereas nonphagocytosed Candida became yellow-red.

Endpoint dilution analysis of Candida interaction with Drosophila S2 cells.

To assess the antifungal activity of Drosophila S2 cells, we conducted an endpoint survival assay where we monitored the survival of Candida SC5314 and GFP-labeled CAI4 strains in the presence of Drosophila S2 cells. Survival was measured as the number of colonies in the presence of S2 cells divided by the number of colonies in the absence of the S2 cells. In the presence of Drosophila S2 cells, the number of colonies formed was 57.4% ± 9.2% lower in the case of strain SC5314 and 61.3% ± 4.5% lower in the case of strain CAI4-GFP than the number of Candida cells in the absence of S2 cells.

Transcriptional analysis of S2 cells' response to the presence of C. albicans.

We used high-density microarrays representing 10,500 Drosophila genes to study global gene expression changes of the S2 cells in response to C. albicans infection. Drosophila S2 cells were coincubated with the C. albicans wild-type strain SC5314, at a starting MOI of 1, in Schneider medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 25°C. A comparison of mRNA levels at 3 h and 6 h after infection, respectively, revealed relatively few changes in gene expression. In Table 1, we show a list of 27 genes differentially regulated by the presence of C. albicans in S2 cells (with a cut-off of 1.5-fold at 6 h postinfection). Among the translational repressors, Thor was one of the most strongly induced genes in the presence of C. albicans (5.6-fold after a 6-h treatment). A representative of secreted proteins, lox (lysyl-oxydase like or dLOXL-1) was observed to be induced 4.5-fold at the same time point. A member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, the Impl2 (CG15009) gene was also induced 2.6-fold as well as the fok gene (3.3-fold). A negative regulator of translation, poly(A)-binding protein-interacting protein 2a (4, 31), was also induced 1.5-fold after a 6-h Candida infection. Attacin A, encoding an antibacterial peptide, showed a 1.6-fold up-regulation. Among detoxification or stress-related proteins in S2 cells infected with C. albicans, the Hph gene was up-regulated 1.6-fold. We also observed the up-regulation of genes involved in sterol and lipid metabolism, such as Fpps (2.2-fold) and ifc (1.6-fold). Four genes were down-regulated upon Candida infection of S2 cells. The String gene involved in the mitotic cell cycle was down-regulated 1.8-fold in 6 h upon infection. A myoblast fusion gene, rolling stone, was also down-regulated 1.7-fold, along with an exonuclease-like gene and an unknown gene, CG30457 (down-regulated 1.6- and 1.5-fold, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Genes regulated in S2 cells in the presence of Candida albicans strain SC5314a

| CG no. | FlyBase | Full name | Gene product | Avg fluorescence ratio at time (h):

|

P value (6 h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 6 | |||||

| CG8846 | Thor | d4E-BP1 | eIF4E binding protein | 2.8 | 5.6 | 2.07E−05 |

| CG11335 | lox | Lysyl oxidase | Lysyl oxidase and Scavenger receptor cysteine-rich (SRCR) domains | 1.7 | 4.5 | 0.00532 |

| CG10746 | fok | Fledgling of Kpl38B | 129-amino-acid peptide | 1.7 | 3.3 | 0.0118 |

| CG15009 | ImpL2 | Ecdysone-inducible gene L2 | Cell adhesion, extracellular | 1.5 | 2.6 | 0.00308 |

| CG1600 | Zinc-containing alcohol dehydrogenase superfamily | 1.5 | 2.5 | 0.000133 | ||

| CG7224 | 118-amino-acid peptide | 1.2 | 2.4 | 0.00494 | ||

| CG12389 | Fpps | Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase | Cholesterol metabolism (EC 2.5.1.1) | 1.5 | 2.2 | 0.000256 |

| CG12818 | 288-amino-acid peptide | 1.5 | 2.1 | 0.00132 | ||

| CG4427 | cbt | Cabut | Transcriptional activator/JNK cascade/autophagy cell death | 1.3 | 1.7 | 0.00253 |

| CG31543 | Hph | HIF prolyl hydroxylase | Oxygen sensor | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.000776 |

| CG11652 | Diptaminde synthesis domain/diphtheria toxin resistance | 1.3 | 1.6 | 5.03E−05 | ||

| CG17836 | HMG-1, HMGY DNA binding domain/transcription regulation | 1.3 | 1.6 | 0.0286 | ||

| CG9078 | ifc | Infertile crescent | Sphingolipid delta-4 desaturase | 1.3 | 1.6 | 0.0272 |

| CG7741 | Similar to yeast Cwfj/RNA splicing | 1.2 | 1.6 | 2.93E−05 | ||

| CG12317 | JhI-21 | l-Amino acid transporter | 1.3 | 1.6 | 0.00682 | |

| CG10146 | AttA | Attacin-A | Antimicrobial peptide | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.0322 |

| CG3424 | path | Pathetic | Amino acid/polyamine transporter | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.0289 |

| CG12358 | Paip2 | Poly(A)-binding protein-interacting protein 2 | Negative regulator of translation | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.00815 |

| CG3767 | JhI-26 | Juvenile hormone-inducible protein 26 | Putative CHK domain (choline kinase) | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.0103 |

| CG1882 | Alpha/beta hydrolase flod/aromatic compound metabolism | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.0106 | ||

| CG17534 | GstE9 | Glutathione S-transferase E9 | Glutathione transferase (EC 2.5.1.18) | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.0225 |

| CG17533 | GstE8 | Glutathione S-transferase E8 | Glutathione transferase (EC 2.5.1.18) | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.0608 |

| CG5729 | Dgp-1 | GTP binding domain/putative translation factor | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.0227 | |

| CG1395 | stg | String | Tyrosine/serine/threonine phosphatase (EC 3.1.3) | −1.3 | −1.8 | 0.000200 |

| CG7670 | 3′-5′ exonuclease and RNase H-like domains | −1.1 | −1.7 | 0.00103 | ||

| CG9552 | rost | Rolling stone | Myoblast fusion | −1.1 | −1.6 | 0.00548 |

| CG30457 | −1.3 | −1.5 | 0.0344 | |||

Genes whose expression was either up-regulated (positive values) or down-regulated (negative values) in Candida-treated cells compared to the Candida-free S2 cells at indicated time points.

d4E-BP mRNA and protein levels increase upon C. albicans infection.

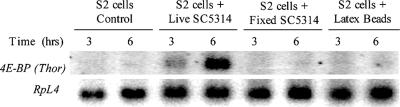

Northern blot analyses were performed to confirm the induction of d4E-BP detected by the microarray analyses. As shown in Fig. 3, d4E-BP mRNA levels increase in the presence of live C. albicans; up-regulation of d4E-BP expression is not detected with coincubation with latex beads or with fixed C. albicans cells. Therefore, the induction of d4E-BP expression appears specific to the immune function in S2 cells and not to the phagocytosis of fixed pathogen or latex particles.

FIG. 3.

Northern blot analysis of Thor gene induction in S2 cells. Lanes from left to right: S2 cells (control), S2 cells infected with live wild-type C. albicans (SC5314), S2 cells in the presence of paraformaldehyde-fixed C. albicans, and S2 cells ingesting latex beads, for 3 and 6 h.

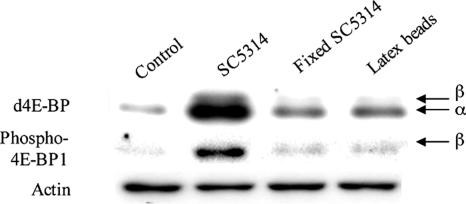

We also analyzed the presence of the d4E-BP protein in total extracts from S2 cells and C. albicans-coincubated cells (Fig. 4). Consistent with our microarray and Northern blot results, we observed increased levels of d4E-BP protein after a 6-h coincubation with live C. albicans. Using a phosphospecific antibody, we found that most of the increased d4E-BP was in the hypophosphorylated (α), active form, although a small increase in the hyperphosphorylated (β) form of d4E-BP was also observed. These results establish that, in S2 cells in the presence of live C. albicans, active d4E-BP protein is present at a higher level.

FIG. 4.

Western blot of d4E-BP protein in S2 cells. Lanes from left to right: S2 cells alone (control), S2 cells infected with live C. albicans (SC5314), S2 cells in the presence of paraformaldehyde-fixed C. albicans, and S2 cells ingesting latex beads for 6 h. Identical amounts of total protein (30 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting with 1868 antibody to d4E-BP or phospho-4E-BP1 (thr37/46). α, active, nonphosphorylated isoform; β, hyperphosphorylated isoform; actin, loading control.

Response of d4E-BPnull flies to infection by C. albicans.

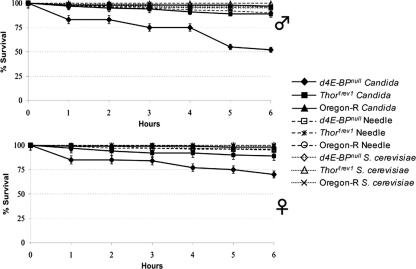

To determine whether d4E-BP contributes to antifungal immunity, we analyzed the survival of Drosophila 4E-BPnull mutant flies following their infection with C. albicans. In separate experiments, 1- to 3-day-old male and female virgin flies were pricked with a very thin needle coated with concentrated C. albicans SC5314 or S. cerevisiae strain pellets or with a sterile needle as a negative control. We measured the survival of Oregon-R, revertant (Thor1rev1), and d4E-BPnull (Thor2) flies 6 h after infection (Fig. 5). We found that d4E-BPnull mutant flies are about 50% less resistant to Candida infection than controls, indicating that d4E-BP is involved in conferring immunity to this fungal species. Although d4E-BPnull mutant flies showed a decreased resistance to Candida infection in both sexes, it is noteworthy that female flies showed a higher resistance than the males. In contrast, the d4E-BPnull mutation had no effect on survival after infection with S. cerevisiae.

FIG. 5.

Survival of D. melanogaster infected with C. albicans strain SC5314 is affected by the 4E-BP mutation. Survival of needle-pricked d4E-BPnull virgin flies was compared to the Oregon-R (wild type) and Thor1rev1 (revertant) flies. (A) The d4E-BPnull male mutant flies were approximately two times more susceptible to the infection with C. albicans during the first 6 h than the wild-type and revertant flies. (B) The d4E-BPnull virgin female flies were 1.5 times more sensitive to the Candida infection than the wild-type and revertant female flies. As a control, d4E-BPnull, Oregon-R, and Thor1rev1 flies of both genders were pricked with a sterile needle or with a needle coated with S. cerevisiae, which had no effect on the survival rate of Drosophila flies. Survival rates did not change significantly after 6 h. Each data point represents the mean of results from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

We used hemocyte-like Drosophila S2 cells, in coculture experiments with C. albicans, as a model representing cell-mediated innate immunity against infection by this pathogen. The transcriptional profiling of the S2 cells during the phagocytosis of C. albicans revealed a number of differentially expressed Drosophila genes in response to the pathogen. Eight of these genes were up-regulated more than 2-fold after 6 h of infection, and the remaining 19 genes were up- or down-regulated at least 1.5-fold. Among the differentially expressed genes, there were known immune-related genes, such as AttA or Thor, and several new candidates for genes involved in cell-based immunity. However, the relatively small number of genes modulated by the interaction with C. albicans indicates that Drosophila S2 cells do not rapidly regulate the transcription of a large number of genes in response to the presence of this fungus. In particular, several known immune-related genes, such as those encoding the antifungal peptides Drosomycin and Metchnikowin or other components of the Toll pathway, are not represented in this profile. Either their regulation might have occurred at times outside the scope of our experiments, or S2 cells lack the capacity to transcriptionally regulate them. Interestingly, the strong and rapid induction of the d4E-BP (Thor) gene suggests that regulation of translation could be a significant mechanism in Drosophila cell-based immunity. Drosophila 4E-BP is homologous to 4E-BPs from other species, and the phosphorylation sites in mammalian 4E-BP1 are conserved in d4E-BP (21). Recent studies have shown that Drosophila has a single d4E-BP (21), in contrast to mammals, which express three distinct 4E-BP proteins (24, 26). This makes Drosophila an excellent model to study the function of 4E-BP in the immune response to pathogens.

In addition to the Northern blots confirming the activation of d4E-BP in S2 cells “infected” by live C. albicans (Fig. 3), Western blot analysis (Fig. 4) confirmed the increase in d4E-BP protein level. We have shown that this protein also remains mostly in its active α form in the S2 cells in the presence of live C. albicans. Such an increase in the level of the active hypophosphorylated d4E-BP protein would compete with the formation of the cap-binding complex and inhibit cap-dependent translation.

To date, the only transcription factor known to regulate the transcription of d4E-BP is dFOXO, which is negatively regulated by insulin and positively regulated by different cellular stresses, through the forkhead response element in the d4E-BP gene promoter (14, 33). However, an additional signaling pathway might target d4E-BP in response to infection in flies, since our transcriptional analysis also failed to detect a change in expression of the FOXO gene (the gene was up-regulated by a maximum of 1.1-fold at 6 h post-Candida infection) as well as dInr, the insulin receptor gene positively regulated by FOXO (27) (Table 1).

In this work, we have established the S2 cell line as a model for the study of gene expression during host-Candida interaction. We used transcriptional profiling to identify several candidates for new immune-related genes in Drosophila and placed d4E-BP as an important player in defense against C. albicans infection. In further studies, the signaling pathway directing the expression and phosphoregulation of d4E-BP in the Drosophila immune response should be of particular interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Sonenberg for the anti-d4E-BP antibodies.

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant to M.W. and D.Y.T. A.L. gratefully acknowledges a Canadian Government Laboratory Visiting Fellowship.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 February 2007.

This is National Research Council publication 47513.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrams, J. M., A. Lux, H. Steller, and M. Krieger. 1992. Macrophages in Drosophila embryos and L2 cells exhibit scavenger receptor-mediated endocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:10375-10379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alarco, A. M., A. Marcil, J. Chen, B. Suter, D. Thomas, and M. Whiteway. 2004. Immune-deficient Drosophila melanogaster: a model for the innate immune response to human fungal pathogens. J. Immunol. 172:5622-5628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashman, R. B., and J. M. Papadimitriou. 1995. Production and function of cytokines in natural and acquired immunity to Candida albicans infection. Microbiol. Rev. 59:646-672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berlanga, J. J., A. Baass, and N. Sonenberg. 2006. Regulation of poly(A) binding protein function in translation: characterization of the Paip2 homolog, Paip2B. RNA 12:1556-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernal, A., and D. A. Kimbrell. 2000. Drosophila Thor participates in host immune defense and connects a translational regulator with innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6019-6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernal, A., R. Schoenfeld, K. Kleinhesselink, and D. A. Kimbrell. 2004. Loss of Thor, the single 4E-BP gene of Drosophila, does not result in lethality. Drosoph. Inf. Serv. 87:81-84. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan, C. A., and K. V. Anderson. 2004. Drosophila: the genetics of innate immune recognition and response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22:457-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson, M., and D. Botstein. 1982. Two differentially regulated mRNAs with different 5′ ends encode secreted with intracellular forms of yeast invertase. Cell 28:145-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemens, M. J. 2001. Translational regulation in cell stress and apoptosis. Roles of the eIF4E binding proteins. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 5:221-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonzi, W. A., and M. Y. Irwin. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franc, N. C., P. Heitzler, R. A. Ezekowitz, and K. White. 1999. Requirement for croquemort in phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in Drosophila. Science 284:1991-1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillum, A. M., E. Y. Tsay, and D. R. Kirsch. 1984. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol. Gen. Genet. 198:179-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gingras, A. C., S. P. Gygi, B. Raught, R. D. Polakiewicz, R. T. Abraham, M. F. Hoekstra, R. Aebersold, and N. Sonenberg. 1999. Regulation of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation: a novel two-step mechanism. Genes Dev. 13:1422-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junger, M. A., F. Rintelen, H. Stocker, J. D. Wasserman, M. Vegh, T. Radimerski, M. E. Greenberg, and E. Hafen. 2003. The Drosophila forkhead transcription factor FOXO mediates the reduction in cell number associated with reduced insulin signaling. J. Biol. 2:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleijn, M., G. C. Scheper, M. L. Wilson, A. R. Tee, and C. G. Proud. 2002. Localisation and regulation of the eIF4E-binding protein 4E-BP3. FEBS Lett. 532:319-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemaitre, B., J. M. Reichhart, and J. A. Hoffmann. 1997. Drosophila host defense: differential induction of antimicrobial peptide genes after infection by various classes of microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14614-14619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorenz, M. C., and J. Heitman. 1997. Yeast pseudohyphal growth is regulated by GPA2, a G protein alpha homolog. EMBO J. 16:7008-7018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martchenko, M., A. M. Alarco, D. Harcus, and M. Whiteway. 2004. Superoxide dismutases in Candida albicans: transcriptional regulation and functional characterization of the hyphal-induced SOD5 gene. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:456-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meister, M., and M. Lagueux. 2003. Drosophila blood cells. Cell. Microbiol. 5:573-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miron, M., P. Lasko, and N. Sonenberg. 2003. Signaling from Akt to FRAP/TOR targets both 4E-BP and S6K in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:9117-9126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miron, M., J. Verdu, P. E. Lachance, M. J. Birnbaum, P. F. Lasko, and N. Sonenberg. 2001. The translational inhibitor 4E-BP is an effector of PI(3)K/Akt signalling and cell growth in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:596-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nantel, A., D. Dignard, C. Bachewich, D. Harcus, A. Marcil, A. P. Bouin, C. W. Sensen, H. Hogues, M. van het Hoog, P. Gordon, T. Rigby, F. Benoit, D. C. Tessier, D. Y. Thomas, and M. Whiteway. 2002. Transcription profiling of Candida albicans cells undergoing the yeast-to-hyphal transition. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:3452-3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neal, S. J., M. L. Gibson, A. K. So, and J. T. Westwood. 2003. Construction of a cDNA-based microarray for Drosophila melanogaster: a comparison of gene transcription profiles from SL2 and Kc167 cells. Genome 46:879-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pause, A., G. J. Belsham, A. C. Gingras, O. Donze, T. A. Lin, J. C. Lawrence, Jr., and N. Sonenberg. 1994. Insulin-dependent stimulation of protein synthesis by phosphorylation of a regulator of 5′-cap function. Nature 371:762-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearson, A. M., K. Baksa, M. Ramet, M. Protas, M. McKee, D. Brown, and R. A. Ezekowitz. 2003. Identification of cytoskeletal regulatory proteins required for efficient phagocytosis in Drosophila. Microbes Infect. 5:815-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poulin, F., A. C. Gingras, H. Olsen, S. Chevalier, and N. Sonenberg. 1998. 4E-BP3, a new member of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 273:14002-14007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puig, O., M. T. Marr, M. L. Ruhf, and R. Tjian. 2003. Control of cell number by Drosophila FOXO: downstream and feedback regulation of the insulin receptor pathway. Genes Dev. 17:2006-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramet, M., P. Manfruelli, A. Pearson, B. Mathey-Prevot, and R. A. Ezekowitz. 2002. Functional genomic analysis of phagocytosis and identification of a Drosophila receptor for E. coli. Nature 416:644-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocha, C. R., K. Schroppel, D. Harcus, A. Marcil, D. Dignard, B. N. Taylor, D. Y. Thomas, M. Whiteway, and E. Leberer. 2001. Signaling through adenylyl cyclase is essential for hyphal growth and virulence in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:3631-3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romani, L., and S. H. Kaufmann. 1998. Immunity to fungi: editorial overview. Res. Immunol. 149:277-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy, G., M. Miron, K. Khaleghpour, P. Lasko, and N. Sonenberg. 2004. The Drosophila poly(A) binding protein-interacting protein, dPaip2, is a novel effector of cell growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:1143-1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stroschein-Stevenson, S. L., E. Foley, P. H. O'Farrell, and A. D. Johnson. 2006. Identification of Drosophila gene products required for phagocytosis of Candida albicans. PLoS Biol. 4:e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tettweiler, G., M. Miron, M. Jenkins, N. Sonenberg, and P. F. Lasko. 2005. Starvation and oxidative stress resistance in Drosophila are mediated through the eIF4E-binding protein, d4E-BP. Genes Dev. 19:1840-1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von der Haar, T., J. D. Gross, G. Wagner, and J. E. McCarthy. 2004. The mRNA cap-binding protein eIF4E in post-transcriptional gene expression. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:503-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]