Abstract

The expression of the ALK1 gene, which encodes cytochrome P450, catalyzing the first step of alkane oxidation in the alkane-assimilating yeast Yarrowia lipolytica, is highly regulated and can be induced by alkanes. Previously, we identified a cis-acting element (alkane-responsive element 1 [ARE1]) in the ALK1 promoter. We showed that a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) protein, Yas1p, binds to ARE1 in vivo and mediates alkane-dependent transcription induction. Yas1p, however, does not bind to ARE1 by itself in vitro, suggesting that Yas1p requires another bHLH protein partner for its DNA binding, as many bHLH transcription factors function by forming heterodimers. To identify such a binding partner of Yas1p, here we screened open reading frames encoding proteins with the bHLH motif from the Y. lipolytica genome database and identified the YAS2 gene. The deletion of the YAS2 gene abolished the alkane-responsive induction of ALK1 transcription and the growth of the yeast on alkanes. We revealed that Yas2p has transactivation activity. Furthermore, Yas1p and Yas2p formed a protein complex that was required for the binding of these proteins to ARE1. These findings allow us to postulate a model in which bHLH transcription factors Yas1p and Yas2p form a heterocomplex and mediate the transcription induction in response to alkanes.

Cytochromes P450 (P450s) constitute a superfamily of ubiquitous heme-containing monooxygenases that catalyze diverse reactions in the metabolism of various endogenous and exogenous hydrophobic compounds (29). Alkanes are one of the most hydrophobic compounds among substrates of P450s. Alkanes are high-energy compounds widespread in the environment, and some prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms have developed P450 oxygenase systems to utilize alkanes as carbon sources (6, 22, 44). Although it has been known for decades that the expression of P450s for alkane utilization is induced by alkanes (6, 22), little is known about the molecular mechanism by which very hydrophobic compounds, such as alkanes, induce P450 expression.

The transcriptional induction of P450 genes by alkanes in alkane-utilizing yeasts such as Candida tropicalis (37, 39, 40), Candida maltosa (31, 32), and Yarrowia lipolytica (17, 18) has been found, but the regulatory mechanism in any yeast has not been elucidated. We have taken advantage of the stable haploid life cycle of Y. lipolytica that makes it favorable for genetic and molecular analyses, in contrast to the Candida species, which are mostly diploid or partially diploid. The property of Y. lipolytica of utilizing hydrophobic compounds efficiently makes this yeast potentially important not only in fundamental research but also in biotechnological applications (4, 12). The entire sequence of the six chromosomes of Y. lipolytica has been determined previously (7, 9), and the genome information is providing us with new insights into the alkane oxidation pathway (12).

The first step in alkane oxidation in alkane-utilizing yeasts is the terminal hydroxylation of alkanes catalyzed by cytochrome P450 ALK products, which are classified into the CYP52 family. We have isolated eight ALK genes (ALK1 to ALK8) encoding P450 ALK products in Y. lipolytica (17, 18). Four more ALK genes have been inferred from the genome information (12; our unpublished results). A single disruption of ALK2, ALK3, ALK4, or ALK6 did not change the growth of Y. lipolytica on alkanes (18). However, the ALK1 gene disruption caused a defect in growth on n-decane, although it did not affect growth on longer-chain alkanes such as n-hexadecane, indicating that ALK1 plays a major role in short-chain alkane assimilation (17). The Δalk1 Δalk2 double mutant grew poorly on both n-decane and n-hexadecane, suggesting that these two genes function coordinately in long-chain alkane oxidation (18).

In accordance with the role of ALK1, the transcription of ALK1 is induced by alkanes, and the induction by n-decane is stronger than that by n-hexadecane (17, 52). Previously, we identified an upstream activating sequence (UAS; CTTGTGNXCATGTG, where N represents any nucleotide and X represents the number of the nucleotides) in the ALK1 promoter and named it the alkane-responsive element 1 (ARE1) (43, 52). The ARE is sufficient to induce transcription in response to alkanes when linked in cis to an alkane-unresponsive promoter (52). ARE1-like sequences are present in other genes that encode enzymes involved in alkane degradation in Y. lipolytica, including the acetoacetyl coenzyme A (CoA) thiolase-encoding gene, PAT1 (51, 52). Similar sequences in the promoters of the P450 ALK and alkane-inducible genes in other alkane-utilizing yeasts were also found, and the conservation of TGTG (or its complementary sequence, CACA) has been suggested previously (52). The presence of CATGTGAA repeats in the promoters of the P450 ALK genes of C. tropicalis was reported previously (39), and repeats of ATGTG (or its complementary sequence, CACAT) were found in some P450 ALK promoters in C. maltosa (31, 32) and Debaryomyces hansenii (50). The TGTG (or CACA) motif was also reported to be present in the alkane-responsive cis-acting promoter elements identified by promoter analysis of the peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase gene in C. tropicalis (19) and the P450 ALK2 gene in C. maltosa (20). Because of the commonly found TGTG motif, the mechanism for the alkane-responsive transcription induction was speculated to be conserved among these yeasts (52).

We identified the YAS1 (yeast alkane signaling) gene from the analysis of a mutant that was defective for ARE1-mediated transcription induction in the presence of alkanes (52). The YAS1 gene encodes a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor that is essential for the alkane-dependent induction of ALK1 transcription. Yas1p in vivo binds to promoters with ARE1, which contains an E box motif (CANNTG), common in the binding sites of bHLH transcription factors (2, 26, 28). However, purified His6-tagged Yas1p alone does not bind to ARE1 in vitro, suggesting that Yas1p requires another factor for its DNA binding (52). The bHLH motif of Yas1p is predicted by a PSI-BLAST search to share highest similarity with that of Ino4p, which is known to form a bHLH heterodimer complex with Ino2p and to regulate the expression of phospholipid biosynthetic genes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae in response to inositol and choline (1, 16, 30, 38; for a review, see reference 15). Neither Ino4p nor Ino2p can form a homodimer, but they do form a heterodimer that interacts with a DNA element called UASINO/ICRE (1, 3, 38). We speculated that Yas1p as well as Ino4p requires another bHLH protein for its DNA binding.

Transcription factors of the HLH family play important roles in many biological processes in organisms from yeasts to mammals (2, 26, 35). More than 240 HLH proteins have been identified to date (2, 26). Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors have two conserved regions for DNA binding and protein-protein interaction (28). First, a basic region allows HLH proteins to recognize and bind to a consensus sequence, CANNTG, called the E box (28, 47). Second, the HLH domain allows these proteins to interact and form homo- and/or heterodimers (28). In this study, we identified a novel bHLH protein, Yas2p, which forms a heterocomplex with Yas1p and binds to ARE1. The YAS2 gene is essential for the induction of ALK1 transcription in response to alkanes and the growth of Y. lipolytica on alkanes. We found that Yas2p has transactivation activity while Yas1p does not have detectable activity. Neither Yas1p nor Yas2p forms a homocomplex, but together they form a heterocomplex that interacts with ARE1. These findings allow us to postulate a model in which these two bHLH transcription factors form a heterocomplex and mediate the transcription induction in response to alkanes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and growth condition.

Y. lipolytica strain CXAU/A1 (ura3 ade1::ADE1) (52) was used as a wild-type strain. The yas2Δ strain was obtained by replacing the open reading frame (ORF) with the ADE1 gene. The YAS2 deletion cassette (described below) was introduced into the CXAU1 strain (ura3 ade1) (17), and Ade+ transformants were analyzed for correct integration by Southern blot analysis. DMU112 is one of the strains isolated by UV mutagenesis from CXUZ1 (ura3::ALK1 promoter-lacZ-ADE1 ade1) as mutants defective for the alkane-dependent induction of ALK1 transcription.

An appropriate carbon source was added to YNB (0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids; Difco) as follows: 2% (wt/vol) glucose, 2% (wt/vol) glycerol, 2% (vol/vol) n-decane, 2% (vol/vol) n-hexadecane, and 2% (vol/vol) oleic acid. Uracil (24 mg/liter) was added, if necessary. For solid medium, 2% agar was added. n-Alkanes in the vapor phase were supplied to YNB solid medium; a piece of filter paper was soaked with n-alkanes and placed in the lid of a petri dish, which was sealed and kept upside down. Growth was at 30°C. The growth curve was obtained with the automatically recording incubator TN1506 (Advantec).

To test inositol auxotrophy, SD medium without inositol (2% glucose, 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 20 μg of biotin/liter, 2 mg of calcium pantothenate/liter, 2 μg of folic acid/liter, 400 μg of niacin/liter, 200 μg of p-aminobenzoic acid/liter, 400 μg of pyridoxine-HCl/liter, 200 μg of riboflavin/liter, 400 μg of thiamine-HCl/liter, 500 μg of H3BO3/liter, 40 μg of CuSO4/liter, 100 μg of KI/liter, 200 μg of FeCl3/liter, 400 μg of MnSO4/liter, 200 μg of Na2MoO4/liter, 400 μg of ZnSO4/liter, 0.85 g of KH2PO4/liter, 0.15 g of K2HPO4/liter, 0.5 g of MgSO4/liter, 0.1 g of NaCl/liter, and 0.1 g of CaCl2/liter) was used with appropriate supplements (24 mg of histidine-HCl/liter, 100 mg of leucine/liter, 20 mg of methionine/liter, 24 mg of uracil/liter, and 48 mg of adenine-HCl/liter) and 2% agar. For SD medium with inositol, 10 mg of inositol/liter was added. As an inositol auxotroph control, the S. cerevisiae ino1Δ strain (BY4741 ino1Δ::kanMX4) was chosen from the S. cerevisiae haploid single-deletion strain collection obtained from EUROSCARF (Frankfurt, Germany). The genotype of the wild-type strain, BY4741, is MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0.

Plasmids.

The YALI0E32417g (YAS2) gene with its flanking region from strain CXAU1 total DNA was PCR amplified with primers 5′-TCGACCGATCTCCGATCTCC-3′ and 5′-AGGCTTGAAGCTCTGCCTAC-3′. The amplified fragment was cloned into the EcoRV site of pBluescript II SK(+) (Stratagene) and into the pGEM-T vector (Promega) to obtain pBS-YAS2 and pT-YAS2, respectively. The KpnI-SpeI fragment from pBS-YAS2 was inserted between the KpnI and SpeI sites of pSUT5 (51) to generate pSYAS2, a plasmid expressing Yas2p from its own promoter in Y. lipolytica.

The YAS2 deletion cassette was constructed as described below. pT-YAS2 was digested with StuI and ClaI to remove most of the YAS2 ORF, blunted, and ligated with the ADE1-carrying BamHI fragment (blunt ended) of pSAT4 to obtain pT-dyas2. The YAS2 deletion cassette was liberated by the digestion of pT-dyas2 with SpeI and SacII.

To express Yas1p and Yas2p fusion proteins with the Gal4 DNA binding domain (Gal4BD), the pBD-GAL4 Cam phagemid vector (Stratagene) was used. For the construction of pBD-YAS1, a PCR was performed with the primer pair YAS1-EcoRI-F (5′-TTCGACGAATTCATGGATTCCCGATCA-3′; underlining in primer sequences indicates restriction enzyme sites) and YAS1-SmaI-R (5′-ATTCGGCCCGGGCTAGACCGGAGACTC-3′) by using plasmid p28-1 (52) as a template. The fragment was digested with EcoRI and SmaI and inserted between the EcoRI and SmaI sites of the pBD-GAL4 Cam phagemid vector. For the construction of pBD-YAS2, a PCR was performed with the primer pair YAS2-EcoRI-F (5′-GCTGAATTCATGCACCTTTCCCACCCACA-3′) and YAS2-SmaI-R (5′-ATTGCCCGGGTTACTCATCAATCTTGGGA-3′) by using plasmid pBS-YAS2 as a template. The fragment was cut with EcoRI and SmaI and inserted between the EcoRI and SmaI sites of the pBD-GAL4 Cam phagemid vector.

To express a protein comprising a fusion between Yas2p and the Gal4 transcription activation domain (Gal4AD), the pAD-GAL4-2.1 phagemid vector (Stratagene) was used. To obtain pAD-YAS2, a PCR was performed with the primer pair YAS2-EcoRI-F and YAS2-PstI-R (5′-GGTGATTGCTGCAGTTACTCATCAATCTTGGGA-3′) by using plasmid pBS-YAS2 as a template. The fragment was cut with EcoRI and PstI and cloned into the corresponding sites in the pAD-GAL4-2.1 phagemid vector.

For His6-tagged-protein expression, the pET-15b vector (Novagen) was used. To construct pET-YAS1, a DNA fragment was PCR amplified with the primer pair YAS1-NHis-NdeI-F (5′-CGACAGCCATATGGATTCCCGATCAG-3′) and YAS1-NHis-BamHI-R (5′-CGGGGATCCCTAGACCGGACACTC-3′) by using p28-1 as a template, cut with NdeI and BamHI, and ligated into NdeI-BamHI-digested pET-15b. To construct pET-YAS2, a DNA fragment was PCR amplified with the primer pair YAS2-NHis-XhoI-F (5′-GCTCTCGAGATGCACCTTTCCCACCCACAG-3′) and YAS2-NGST/His-XhoI-R (5′-TTGCTCGAGTTACTCATCAATCTTGGGAGG-3′) by using pBS-YAS2 as a template, digested with XhoI, and inserted into the XhoI site of pET-15b.

For the expression of GST fusion proteins, the pGEX-4T-3 vector (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences [formerly Amersham Biosciences]) was used. To obtain pGEX-YAS1, a DNA fragment was PCR amplified with the primer pair YAS1-NGST-BamHI-F (5′-ACGGATCCATGGATTCCCGATCAG-3′) and YAS1-NGST-SalI-R (5′-GAGATTCGGGTCGACCTAGACCGGAGACTC-3′) by using p28-1 as a template, cut with BamHI and SalI, and cloned into the corresponding sites in pGEX-4T-3. To obtain pGEX-YAS2, a DNA fragment was PCR amplified with the primer pair YAS2-NGST-EcoRI-F (5′-CCGAATTCCATGCACCTTTCCCACCCACAG-3′) and YAS2-NGST/His-XhoI-R by using pBS-YAS2 as a template, cut with EcoRI and XhoI, and cloned into the corresponding sites in pGEX-4T-3.

After PCR amplification, the DNA fragments were checked by sequence analysis.

Transformation of Y. lipolytica.

Y. lipolytica was transformed by electroporation as previously described (17).

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA was prepared with the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN), and 1 μg of total RNA from each sample was analyzed. Hybridization and detection were performed using digoxigenin-labeled DNA with a CSPD system (Roche Diagnostics). A PstI-EcoRV fragment from pSAT4-ALK1 (17) was used as a probe for ALK1.

One-hybrid and two-hybrid analyses.

S. cerevisiae YRG-2 (Matα ura3-52 his3-200 ade2-101 lys2-801 trp1-901 leu2-3,112 gal4-542 gal80-538, with HIS3 and lacZ reporter gene constructs LYS2::UASGAL1-TATAGAL1-HIS3 [a fusion of the UAS of GAL1 and the TATA portion of the GAL1 promoter with HIS3] and URA3::UASGAL4 17mers(×3)-TATACYC1-lacZ [a fusion of three copies of the GAL4 17-mer consensus sequence and the TATA portion of the iso-1-cytochrome c promoter with lacZ]; Stratagene) was used as a host strain. To assay HIS reporter expression, cells were plated onto 10 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT)-containing medium. For the β-galactosidase assay, cells were harvested at an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.8, washed, and disrupted in Z buffer (43) by vortexing with glass beads. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min, and the resultant supernatant was incubated with ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside). One unit of β-galactosidase activity was defined as 1 nmol of o-nitrophenyl produced per minute.

In vitro protein-protein interaction assay.

“Epicurian coli” BL21(DE3) (Stratagene) was transformed with appropriate plasmids, and a culture was grown to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼1.0 at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl). Following 4 h of incubation with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), cells were harvested and lysed by using a multibead shocker (YASUI KIKAI, Osaka, Japan) in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl at pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5% NP-40 plus protease inhibitors composed of 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg leupeptin ml−1, aprotinin, antipain, and chymostatin). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min twice. Fusion proteins were prepared as crude bacterial lysates. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) for 2 h at 4°C with constant rotation. The beads were washed with lysis buffer to remove unbound protein. Glutathione-Sepharose beads coupled with ∼6 μg of GST fusion protein were incubated with ∼6 μg of His6-tagged protein for 2 h at 4°C with constant rotation. The beads were washed eight times with lysis buffer. Bound proteins were eluted by boiling in 60 μl of 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-sample buffer (125 mM Tris-Cl [pH 6.8], 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.0005% bromophenol blue), and 10 or 20 μl was subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) followed by immunoblotting. Ten percent or 15% polyacrylamide gel was used. His6-tagged proteins were detected with anti-T7-His monoclonal antibody (Novagen) at 1:5,000. GST and GST fusion proteins were detected with anti-GST monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:5,000. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000; Cell Signaling Technology) and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) were used to visualize the resolved proteins.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

Complex formation among the recombinant proteins (6 μg of crude extract) and 100 fmol of 32P-end-labeled DNA was performed in 18 μl of 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1.25 mM dithiothreitol, 0.05% NP-40, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 μg of poly(dI-dC)-poly(dI-dC). The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5 min and subjected to 5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at 120 V in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the YAS2 gene has been submitted to the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank databases under accession number AB212950.

RESULTS

Identification of a protein with a bHLH motif similar to that of Yas1p.

As the bHLH transcription factor Yas1p alone does not bind to DNA element ARE1 in vitro (52), we speculated that Yas1p requires another bHLH protein for its function. To identify the binding partner of Yas1p, we searched the Y. lipolytica genome database with the BLAST program provided by the Génolevures project (http://cbi.labri.fr/Genolevures/BLAST/index.php; 7, 9, 42) by using the bHLH motif of Yas1p as a query. The highest score, 36.6 bits, was calculated for the YALI0B13354g translation product, followed by 34.7 bits for YALI0E32417g, 32.7 bits for YALI0D24167g, 28.1 bits for YALI0C03564g, and 24.6 bits for YALI0C13178g. A Pfam search predicted a bHLH motif in all of these five translation products (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Pfam/; 13).

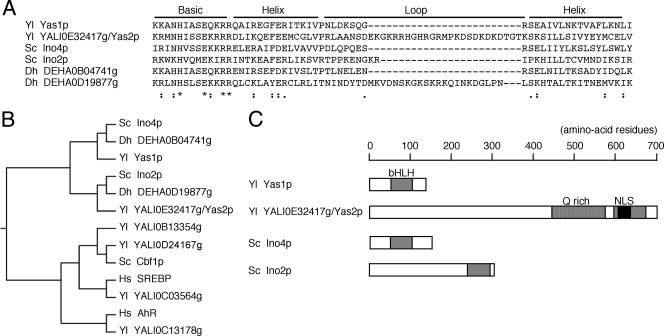

The bHLH motifs of the translation products were aligned and compared (Fig. 1A and B). The bHLH motif of Yas1p has the highest similarity to that of Ino4p (Fig. 1B) (52). Ino4p is known to form a bHLH heterodimer complex with Ino2p and functions in the activation of phospholipid biosynthetic gene transcription (1, 15, 16, 30, 38). A phylogenetic tree of bHLH motifs suggested that the YALI0E32417g translation product has a relatively close relationship to Ino2p, Ino4p, and Yas1p compared to other bHLH proteins (Fig. 1B). This relationship prompted us to pursue the possibility that the YALI0E32417g translation product may be a heterodimer partner of Yas1p, and we named the YALI0E32417g gene YAS2. Yas2p is a 700-amino-acid protein, and it has a bHLH motif in its carboxy-terminal region with 20.5% identity to the motif of Yas1p (Fig. 1A and C). The bHLH motif alignment showed that Yas2p has a unique 25-amino-acid stretch that is not present in Yas1p, Ino2p, or Ino4p (Fig. 1A). Regions of Yas2p other than the bHLH motif do not share a high level of homology with regions of known proteins, but Yas2p has a potential nuclear localization signal (amino acids 601 to 630) (8) and a glutamine-rich domain (amino acids 445 to 574; 47 glutamine residues) with remarkable polyglutamine stretches (Fig. 1C). The glutamine-rich domains and polyglutamine stretches are reported to be involved in transcriptional activation in organisms ranging from yeasts to humans (10, 14, 33).

FIG. 1.

Relationship of YALI0E32417g/Yas2p with other bHLH proteins. (A) Alignment of the bHLH motifs. Sequences were aligned by the CLUSTALW program (45) on the website of the Kyoto University Bioinformatics Center by using the slow/accurate mode and default parameters (http://clustalw.genome.jp/). Amino acids identical among the six proteins are shown by asterisks, and conserved amino acids are indicated by dots. (B) Phylogenetic relatedness of the YALI0E32417g/Yas2p bHLH motif to other bHLH proteins. Shown is a dendrogram reconstructed using CLUSTALW methods (http://clustalw.genome.jp/). (C) Schematic diagrams of bHLH proteins. The bHLH motifs are indicated by gray boxes. The glutamine-rich (Q rich) region and the potential nuclear localization signal (NLS) are shown as striped and filled boxes, respectively. The first two letters in the protein labels indicate the species of origin: Yl, Y. lipolytica; Sc, S. cerevisiae; Dh, D. hansenii; Hs, Homo sapiens. Swiss-Prot accession numbers are as follows: S. cerevisiae Ino4p, P13902; S. cerevisiae Ino2p, P26798; S. cerevisiae Cbf1p, P17106; Homo sapiens SREBP1, P36956; and Homo sapiens AhR, P35869. For Y. lipolytica and D. hansenii ORF products, ordered locus names as designated in the Génolevures project are indicated. See the text for discussion about DEHA0B04741g and DEHA0D19877g.

The YAS2 gene is essential for transcription induction in response to alkanes.

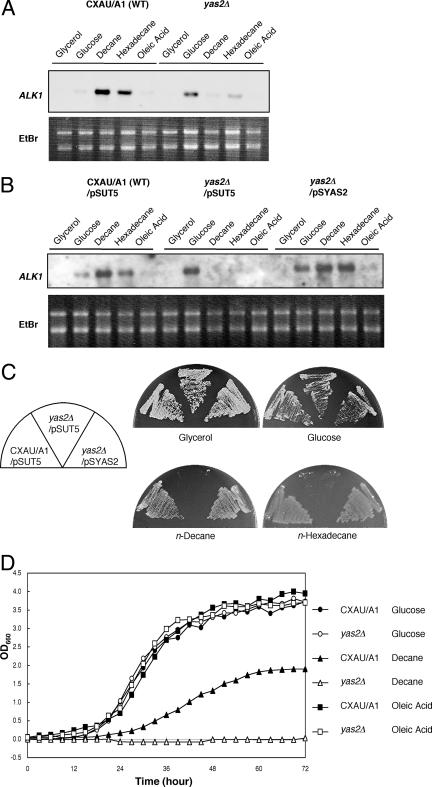

To study the function of the YAS2 gene, we constructed the YAS2 deletion mutant (yas2Δ). We performed Northern blot analysis to assess whether or not the YAS2 gene is required for the alkane-dependent induction of ALK1 transcription by using wild-type and yas2Δ cells (Fig. 2A). Yeast cells were cultured in glycerol-containing medium and transferred to medium with glycerol, glucose, n-decane, n-hexadecane, or oleic acid. Glycerol is a carbon source that represses the expression of ALK1 (17). After 1 h of incubation with n-decane or n-hexadecane, ALK1 mRNA induction was clearly detected in the wild-type cells but at only faint levels in the yas2Δ strain (Fig. 2A). This defect was eliminated by expressing YAS2 from a low-copy-number centromere/autonomous replication sequence vector (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that the YAS2 gene is required for the induction of ALK1 transcription in response to alkanes. For an unknown reason, the amount of ALK1 mRNA in the yas2Δ cells incubated with glucose was larger than that in the wild-type cells (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Requirement of the YAS2 gene for alkane-dependent transcription induction and growth on alkanes. (A) ALK1 gene expression was not induced by n-decane and n-hexadecane in the YAS2 deletion mutant. Cells were grown in glycerol-containing medium, transferred to minimal media containing glycerol, glucose, n-decane, n-hexadecane, or oleic acid, and cultured for 1 h. One microgram of total RNA was loaded. WT, wild type; EtBr, ethidium bromide. (B) The defect in alkane-responsive transcription induction in the YAS2 deletion mutant was abolished by the introduction of the YAS2-carrying plasmid pSYAS2. pSUT5 is an empty vector. Culture and RNA loading conditions are described in the legend to panel A. (C) The YAS2 deletion mutant carrying vector pSUT5 did not grow on n-decane and n-hexadecane, but pSYAS2 restored growth. (D) The YAS2 deletion mutant did not grow in liquid medium with n-decane, but it did grow with oleic acid. Two percent glucose or 1% oleic acid was added to minimal medium. Two percent n-decane was added initially, followed by supplementation with 1% n-decane every 24 h. OD660, optical density at 660 nm.

The yas2Δ mutant is defective for growth on alkanes.

We examined whether or not the YAS2 gene is required for growth on alkanes, as is the YAS1 gene (Fig. 2C and D) (52). On solid medium, where n-decane or n-hexadecane was added as vapor, the yas2Δ strain did not grow (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, on glycerol- or glucose-containing medium, it grew as well as the wild-type strain (Fig. 2C). The defect in the growth of the yas2Δ strain on alkanes was eliminated by the introduction of the YAS2-carrying plasmid pSYAS2 (Fig. 2C). The yas2Δ strain was also unable to proliferate in liquid medium containing n-decane as the sole carbon source (Fig. 2D). Although alkanes are metabolized via conversion to fatty acids, the yas2Δ cells were able to grow on medium containing oleic acid as the carbon source (Fig. 2D). These results indicate that YAS2 is essential for alkane utilization but not for fatty acid utilization. The requirement for YAS2 for the alkane-responsive induction of ALK1 and for alkane utilization is identical to that for YAS1, which suggests that YAS1 and YAS2 function in the same pathway.

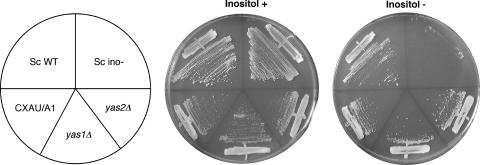

Dispensability of Yas1p-Yas2p for inositol biosynthesis.

S. cerevisiae Ino2p and Ino4p are required for the expression of INO1, which encodes an enzyme necessary for the de novo synthesis of inositol (15). Therefore, ino4 and ino2 mutants require inositol for growth. To examine whether Yas1p and Yas2p are involved in the inositol biosynthesis pathway, the growth of the yas1Δ and yas2Δ strains in the presence or absence of inositol was analyzed (Fig. 3). Both of the yas1Δ and yas2Δ strains were able to grow on the medium without inositol as well as on the inositol-supplemented medium, while S. cerevisiae inositol auxotroph mutant cells showed clear defects in growth in the absence of inositol (Fig. 3). In spite of the feasibility of a close relationship between the Ino4p-Ino2p and Yas1p-Yas2p systems, neither the yas1Δ nor the yas2Δ strain showed inositol auxotrophy. From these results, we speculate that the major function of Yas1p-Yas2p is different from that of Ino4p-Ino2p.

FIG. 3.

Inositol prototrophy of yas1Δ and yas2Δ strains. The growth of yas1Δ and yas2Δ mutants in the presence (inositol +) or absence (inositol −) of inositol was compared to that of the wild-type CXAU/A1 strain. S. cerevisiae wild-type (Sc WT) and inositol auxotroph mutant (Sc ino-) strains were used as controls.

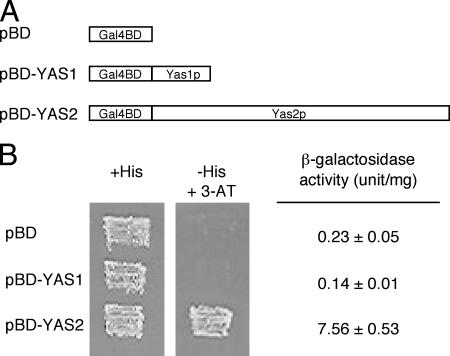

Yas2p has a transactivation function.

To determine whether Yas1p or Yas2p has transactivation activity, we performed a one-hybrid assay with S. cerevisiae. Full-length Yas1p or Yas2p was fused with Gal4BD to create chimeric transcription factors that were dependent on Yas1p or Yas2p for transcriptional activation but not for DNA binding (Fig. 4A). The plasmids expressing Gal4BD-Yas1p or Gal4BD-Yas2p were introduced into S. cerevisiae YRG-2, which has two reporter genes, UASGAL1- TATAGAL1-HIS3 and UASGAL4 17mers(×3)-TATACYC1-lacZ. We tested for the transcriptional activation of these genes by measuring the growth of the plasmid-carrying strains on plates containing 10 mM 3-AT and by quantifying their β-galactosidase activities, respectively (Fig. 4B). Gal4BD-Yas2p expression supported growth on 3-AT-containing medium and increased β-galactosidase activity, but Gal4BD-Yas1p expression did neither (Fig. 4B). The presence of Gal4BD-Yas1p was detectable by Western blot analysis using Gal4BD antibody (data not shown). These results suggest that Yas2p but not Yas1p has transactivation activity.

FIG. 4.

Transcriptional activation by Yas2p. (A) Schematic diagrams of Gal4BD fusion proteins. The pBD-GAL4 Cam phagemid vector (pBD) producing Gal4BD, pBD-YAS1 producing the Gal4BD-Yas1 fusion protein, or pBD-YAS2 producing the Gal4BD-Yas2 fusion protein was introduced into S. cerevisiae YRG-2. (B) Yas2p has a transactivation function. Transcriptional activation of the reporter genes UASGAL1-TATAGAL1-HIS3 and UASGAL4-TATACYC1-lacZ was detected by using a plate containing 10 mM 3-AT (−His + 3-AT) and by using a β-galactosidase assay (+His), respectively. The results shown are the averages ± the standard errors of the means of results from six independent experiments.

Yas2p interacts with Yas1p.

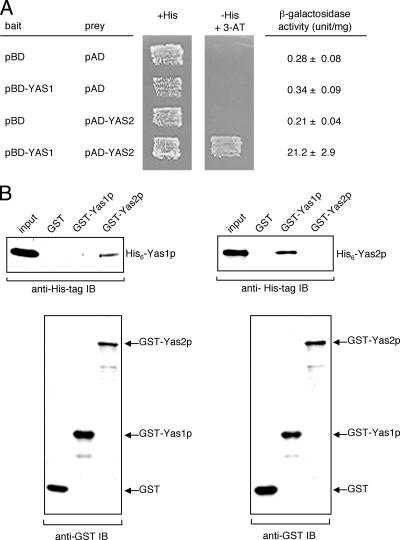

To determine whether or not Yas2p interacts with Yas1p, we carried out a two-hybrid assay with S. cerevisiae YRG-2 cells. Because Gal4BD-Yas2p had transcription activity, it could not be used as bait. We therefore expressed Gal4BD-Yas1p as bait and a fusion protein comprising Gal4AD and Yas2p as prey. Specific interaction between Gal4BD-Yas1p and Gal4AD-Yas2p was detected by assessing the activation of the HIS3 and lacZ reporter genes on a 3-AT-containing plate and by measuring the β-galactosidase activity, respectively (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Interaction between Yas1p and Yas2p. (A) Positive interaction between Yas1p and Yas2p in a yeast two-hybrid assay. Bait plasmids pBD-GAL4 Cam (pBD) and pBD-YAS1 are described in the legend to Fig. 4. Prey plasmids pAD-GAL4-2.1 phagemid vector (pAD), producing Gal4AD, and pAD-YAS2, producing the Gal4AD-Yas2 fusion protein, were introduced into S. cerevisiae YRG-2. Specific interaction was detected by assessing the activation of the reporter genes, UASGAL1-TATAGAL1-HIS3 and UASGAL4-TATACYC1-lacZ, by using a 3-AT-containing plate (−His + 3-AT) and β-galactosidase activity (+His), respectively. The results shown are the averages ± the standard errors of the means of results from six independent experiments. (B) Specific interaction of recombinant Yas1p and Yas2p in vitro. Bacterially expressed GST or GST fusion proteins were immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads and then incubated with extracts containing His-tagged Yas1p or Yas2p. After washing of the beads, bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting (IB). Immunoblotting with anti-His tag antibody detected the presence of His6-Yas1p (left upper panel) or His6-Yas2p (right upper panel). Immunoblotting with anti-GST antibody demonstrated the binding of GST, GST-Yas1p, and GST-Yas2p to the beads (lower panels).

To further confirm the direct interaction between Yas1p and Yas2p, we performed in vitro binding assays with recombinant proteins. Bacterially expressed GST, GST-Yas1p, or GST-Yas2p protein was immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads and then incubated with extracts containing His-tagged Yas1p. Bound protein complexes were eluted from the beads, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with anti-His tag antibody. We found that His-tagged Yas1p bound to GST-Yas2p, while we could not detect any binding to GST alone or to GST-Yas1p (Fig. 5B, left panels). His-tagged Yas2p bound to GST-Yas1p but not to GST or GST-Yas2p (Fig. 5B, right panels). These findings suggest that Yas1p and Yas2p interact with each other and form a heterocomplex and that neither Yas1p nor Yas2p makes a homocomplex.

Yas1p-Yas2p association is required for DNA binding.

To evaluate the DNA binding properties of the Yas1p-Yas2p complex, we performed an electrophoretic mobility shift assay using ARE1-containing DNA as a probe (Fig. 6A). Neither bacterially expressed Yas1p nor Yas2p alone bound efficiently to the radiolabeled DNA fragment (Fig. 6B). In the presence of both Yas1p and Yas2p, however, the DNA-protein complex was recognized (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that interaction between Yas1p and Yas2p is required for the direct binding of these proteins to ARE1.

FIG. 6.

Formation of Yas1p-Yas2p complex on ARE1. (A) The nucleotide sequence of a probe used for the electrophoretic mobility shift assay. ARE1 (CTTGTGNXCATGTG) is underlined. (B) Binding of the Yas1p-Yas2p heterocomplex to ARE1. Bacterial cell extracts containing GST, GST-Yas1p, or His6-Yas2p were incubated with 32P-labeled probe. The DNA-protein complex was resolved on a 5% polyacrylamide gel. +, present; −, absent.

Identification of mutant allele yas2-1.

The phenotypes of yas1Δ and yas2Δ mutants were indistinguishable from that of DMU112, a strain isolated in our laboratory as a mutant defective for alkane-dependent transcription induction and growth on alkanes. The introduction of YAS1 into DMU112 did not complement its defect in growth on alkane, but the introduction of YAS2 did (data not shown). We determined the nucleotide sequence of the YAS2 coding region of DMU112. We found that DMU112 carries a yas2 mutant allele, yas2-1, which lacks the 835th nucleotide residue T, causing a frameshift. These results suggested that DMU112 has lost the alkane response due to the mutation in the YAS2 gene. This finding supports our conclusion that Yas2p is an essential factor for the alkane response of, and assimilation by, Y. lipolytica.

DISCUSSION

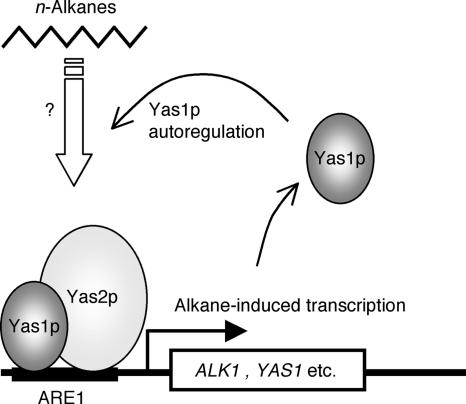

Our results suggest that two yeast bHLH transcription factors, Yas1p and Yas2p, make a heterocomplex that can bind to ARE1 (CTTGTGNXCATGTG) of the ALK1 gene and that this complex mediates the transcription induction in response to alkanes (Fig. 7). ARE1-like sequences are found in the promoters of other genes involved in alkane oxidation, including PAT1 (51, 52). The in vivo association of Yas1p with ALK1 and PAT1 gene promoters was shown in our previous report (52). Yas1p also binds to its own promoter, and YAS1 transcription is induced by alkanes, suggesting an autoregulatory loop of Yas1p (Fig. 7) (52). The crystal structures of some bHLH proteins, such as Max (11) and MyoD (25), in the presence of their target DNA sites were determined, indicating that bHLH proteins bind as a dimer to their recognition sequences by direct contact. Although the data presented in this paper do not allow us to distinguish between the Yas1p-Yas2p heterodimer and higher-order structures, the Yas1p-Yas2p complex is likely a heterodimer in its active form, based on the analogy to other bHLH proteins of known molecular structures. However, this possibility remains to be clarified, together with the precise DNA target sequence of the complex.

FIG. 7.

Model for the alkane-dependent transcription induction by the Yas1p-Yas2p heterocomplex. The potential bHLH heterodimer complex of Yas1p and Yas2p binds to ARE1 (CTTGTGNXCATGTG) in the ALK1 promoter, and it induces the transcription of ALK1 in the presence of alkanes. The Yas1p-Yas2p complex also binds the promoters of other genes involved in the alkane utilization, including the acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase gene and the YAS1 gene itself. The positive autoregulatory feedback loop of Yas1p makes it possible to induce massive changes in gene expression in response to alkanes and to adapt quickly to exposure to alkanes.

bHLH motifs similar to that of Yas1p and Yas2p found in D. hansenii.

Because ARE-like sequences are commonly found in the 5′ upstream regions of alkane-inducible genes in other alkane-utilizing yeasts, the conservation of the alkane-responsive transcription induction mechanism has been speculated (52). To explore this possibility, we tested if we could find Yas1p and Yas2p homologues from other yeasts. D. hansenii is an alkane-assimilating yeast, and its complete genome sequence, as well as that of Y. lipolytica, has been determined by the Génolevures project (9, 23, 42). The P450 ALK genes in D. hansenii have been isolated, and ARE1-like ATGTG repeats in their promoter sequences were reported (50). We searched the D. hansenii genome by BLAST analysis using bHLH motifs and the full-length amino acid sequences of Yas1p and Yas2p. In all four cases, the highest scores were calculated for DEHA0B04741g (110 amino acids) and DEHA0D19877g (371 amino acids). Both translation products were predicted by Pfam searching to have a bHLH motif (13). A phylogenetic analysis grouped the bHLH motifs of DEHA0B04741g and DEHA0D19877g into the Ino4p-Yas1p and Ino2p-Yas2p clusters, respectively (Fig. 1B). The functional analysis of these D. hansenii proteins is required, but it should be noted that the bHLH domain of DEHA0D19877g has a long loop, as seen in Yas2p (Fig. 1A). We believe our findings will provide a clue to elucidate the alkane response mechanism not only in Y. lipolytica but also in other alkane-utilizing yeasts.

Furthermore, we demonstrated in this paper that neither Yas1p nor Yas2p is essential for inositol biosynthesis in spite of their close relationship to S. cerevisiae Ino4p and Ino2p. These results suggested the distinct physiological functions of Yas1p-Yas2p and Ino4p-Ino2p. Analyses of bHLH proteins from other alkane-assimilating yeasts might provide novel insight into the evolutionary origin of the alkane-responsive transcription induction mechanism.

Possible alkane-sensing mechanisms.

Previously, we showed that Yas1p localizes to the nucleus independently of alkanes (52). First, one of the attractive molecular mechanisms for alkane-dependent transcription induction is the alkane-dependent nuclear localization of Yas2p. To test this possibility, we expressed C-terminally myc-tagged Yas2p (Yas2p-myc) in the yas2Δ strain. The expression of Yas2p-myc abolished the defects in the growth of yas2Δ cells on alkanes (data not shown), indicating that the tagged protein is functional. However, we have not succeeded in visualizing Yas2p-myc by immunofluorescence microscopy with anti-myc antibody. We also found that the intact Yas2p-myc was hard to detect by Western blot analysis with the usual methods. When we prepared cell extract by disrupting cells mechanically in liquid nitrogen to avoid protein degradation, we could recognize a band for Yas2p-myc of the predicted size (data not shown). These results suggested that Yas2p-myc is an unstable protein and that the instability makes it difficult to detect this protein by immunofluorescence. Second, another possible mechanism for the alkane-responsive transcription induction is the alkane-dependent activation of transcription factors Yas1p and/or Yas2p. Because Yas2p showed a transactivation function in S. cerevisiae cells even in the absence of alkanes (Fig. 4), this mechanism is less attractive. However, we cannot deny the possibility that the transactivation activity of Yas1p and/or Yas2p is regulated directly by alkanes or alkane derivatives in Y. lipolytica cells. Finally, the other possibility is that some proteins regulate the transactivation activity of Yas1p and/or Yas2p. We identified a gene encoding a Y. lipolytica homologue of S. cerevisiae Opi1p, and we found that the deletion of the gene caused an increase of ALK1 mRNA expression in the absence of alkanes (our unpublished results). Opi1p functions as a negative regulator of Ino4p-Ino2p-dependent phospholipid biosynthetic gene expression (48, 49). It has been proposed that Opi1p is inactivated by binding phosphatidic acid on the endoplasmic reticulum in the absence of inositol and that Opi1p translocates into the nucleus and inhibits Ino2p-Ino4p in response to the consumption of phosphatidic acid induced by inositol (24). Hydrophobic compounds like alkanes are known to accumulate into lipid bilayers (41). It is an attractive idea that the Opi1 homologue in Y. lipolytica senses alkanes, alkane derivatives, or other membrane components. However, how alkanes are recognized in the yeast is still an open question.

Transactivation activity of Yas2p.

The transcription activation activity of Yas2p in S. cerevisiae was recognized, whereas Yas1p showed no detectable activity toward the activation of transcription in the S. cerevisiae one-hybrid assay. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that Yas1p also has transactivation activity in Y. lipolytica, we postulate that Yas1p contributes to transcription activation by forming a heterocomplex with Yas2p. This relationship reminds us of that of the mammalian Myc oncoprotein and Max protein, where Myc has a transactivation function but requires heterodimer formation with Max for its DNA binding (36). It has also been reported that Ino2p has a transcriptional activation function but that its ability to bind DNA depends on dimerization with Ino4p (38). Ino4p was suggested not to have a transcriptional activation function (38), but another group reported that Ino4p also has weak transcription activation activity (34).

According to their amino acid compositions, eukaryotic transactivation domains (TADs) have been classified mainly into three types: acidic, proline-rich, and glutamine-rich domains (27, 46). Ino2p has two TADs in its N terminus region, neither of which is glutamine rich (38). Among HLH family proteins, the glutamine-rich domain is found in the TAD of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and it is critical for the human AhR transactivation function (21). It remains to be determined whether or not the highly glutamine-rich domain (47 glutamine residues in a region of 130 amino acids) of Yas2p fulfills some specific functions.

Possible involvement in glucose repression.

While Northern blot analyses clearly showed that the YAS1 and YAS2 genes are essential for the alkane-dependent induction of ALK1 gene transcription, we also noticed that the amount of ALK1 mRNA in the yas1Δ and yas2Δ strains was always larger than that in the wild-type strain when the strains were incubated with glucose (Fig. 2A) (52). On the other hand, the amount of ALK1 mRNA in the yas1Δ and yas2Δ strains remained as small as that in the wild type when the cells were cultivated with glycerol (Fig. 2A) (52). In Y. lipolytica cells, glucose has weak transcription-repressive activity whereas glycerol has strong repressive activity (17, 18, 52). The higher level of the ALK1 mRNA in the yas1Δ and yas2Δ cells incubated with glucose suggests that Yas1p and Yas2p might be involved in the glucose repression of the ALK1 genes. Some transcription factors, including HLH proteins, are known to demonstrate both transactivation and transrepression functions by interacting with different sets of proteins (5). The identification of proteins that interact with Yas1p and Yas2p will clarify these mechanisms.

Other bHLH proteins in Y. lipolytica.

The Yas1p-Yas2p system seems to resemble the Ino4p-Ino2p and Max-Myc systems in S. cerevisiae and mammals, respectively. Yas1p, Ino4p, and Max are all small bHLH proteins, from 137 to 160 amino acid residues (5, 16, 52), and each forms a heterocomplex with its respective partner, Yas2p, Ino2p, or Myc, which is larger and carries major transactivation activity in the complex. It is well studied that Max can form multiple heterodimer complexes with Myc, Mad, and Mxi1 to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation (5, 36). The heterodimer between Ino4p and Ino2p is well known, but it was also reported that Ino4p can interact with four other bHLH proteins: Pho4p, Rtg1p, Rtg3p, and Sgc1p (34). It has been suggested that Ino4p may serve as a central component of multiple heterodimer complexes in various biological processes (34). The multiple dimer combinations will allow the expansion of possible target sequences and a variety of transcription regulatory activities.

In this paper, we showed that Yas1p-Yas2p plays a major role in the alkane-responsive transcription induction. However, it remains to be elucidated whether Yas1p and/or Yas2p can interact with other HLH proteins to function in alkane response or in other pathways. We identified Y. lipolytica novel genes encoding bHLH proteins by BLAST searching (Fig. 1). The analysis of these bHLH proteins will provide new information to answer the question of interaction. The two-hybrid system established here will also be a powerful tool to screen additional HLH proteins that may interact with Yas1p and Yas2p.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Horiuch for helpful discussion and support. This work was performed using the facilities of the Biotechnology Research Center at the University of Tokyo.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambroziak, J., and S. A. Henry. 1994. INO2 and INO4 gene products, positive regulators of phospholipid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, form a complex that binds to the INO1 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 269:15344-15349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atchley, W. R., and W. M. Fitch. 1997. A natural classification of the basic helix-loop-helix class of transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:5172-5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachhawat, N., Q. Ouyang, and S. A. Henry. 1995. Functional characterization of an inositol-sensitive upstream activation sequence in yeast. A cis-regulatory element responsible for inositol-choline mediated regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 270:25087-25095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barth, G., and C. Gaillardin. 1997. Physiology and genetics of the dimorphic fungus Yarrowia lipolytica. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 19:219-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baudino, T. A., and J. L. Cleveland. 2001. The Max network gone mad. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:691-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardini, G., and P. Jurtshuk. 1970. The enzymatic hydroxylation of n-octane by Corynebacterium sp. strain 7E1C. J. Biol. Chem. 245:2789-2796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casaregola, S., C. Neuveglise, A. Lepingle, E. Bon, C. Feynerol, F. Artiguenave, P. Wincker, and C. Gaillardin. 2000. Genomic exploration of the hemiascomycetous yeasts. 17. Yarrowia lipolytica. FEBS Lett. 487:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cokol, M., R. Nair, and B. Rost. 2000. Finding nuclear localization signals. EMBO Rep. 1:411-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dujon, B., D. Sherman, G. Fischer, P. Durrens, S. Casaregola, I. Lafontaine, J. De Montigny, C. Marck, C. Neuveglise, E. Talla, N. Goffard, L. Frangeul, M. Aigle, V. Anthouard, A. Babour, V. Barbe, S. Barnay, S. Blanchin, J. M. Beckerich, E. Beyne, C. Bleykasten, A. Boisrame, J. Boyer, L. Cattolico, F. Confanioleri, A. De Daruvar, L. Despons, E. Fabre, C. Fairhead, H. Ferry-Dumazet, A. Groppi, F. Hantraye, C. Hennequin, N. Jauniaux, P. Joyet, R. Kachouri, A. Kerrest, R. Koszul, M. Lemaire, I. Lesur, L. Ma, H. Muller, J. M. Nicaud, M. Nikolski, S. Oztas, O. Ozier-Kalogeropoulos, S. Pellenz, S. Potier, G. F. Richard, M. L. Straub, A. Suleau, D. Swennen, F. Tekaia, M. Wesolowski-Louvel, E. Westhof, B. Wirth, M. Zeniou-Meyer, I. Zivanovic, M. Bolotin-Fukuhara, A. Thierry, C. Bouchier, B. Caudron, C. Scarpelli, C. Gaillardin, J. Weissenbach, P. Wincker, and J. L. Souciet. 2004. Genome evolution in yeasts. Nature 430:35-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escher, D., M. Bodmer-Glavas, A. Barberis, and W. Schaffner. 2000. Conservation of glutamine-rich transactivation function between yeast and humans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2774-2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferre-D'Amare, A. R., G. C. Prendergast, E. B. Ziff, and S. K. Burley. 1993. Recognition by Max of its cognate DNA through a dimeric b/HLH/Z domain. Nature 363:38-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fickers, P., P. H. Benetti, Y. Wache, A. Marty, S. Mauersberger, M. S. Smit, and J. M. Nicaud. 2005. Hydrophobic substrate utilisation by the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica, and its potential applications. FEMS Yeast Res. 5:527-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finn, R. D., J. Mistry, B. Schuster-Bockler, S. Griffiths-Jones, V. Hollich, T. Lassmann, S. Moxon, M. Marshall, A. Khanna, R. Durbin, S. R. Eddy, E. L. Sonnhammer, and A. Bateman. 2006. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:D247-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerber, H. P., K. Seipel, O. Georgiev, M. Hofferer, M. Hug, S. Rusconi, and W. Schaffner. 1994. Transcriptional activation modulated by homopolymeric glutamine and proline stretches. Science 263:808-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg, M. L., and J. M. Lopes. 1996. Genetic regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 60:1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoshizaki, D. K., J. E. Hill, and S. A. Henry. 1990. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae INO4 gene encodes a small, highly basic protein required for derepression of phospholipid biosynthetic enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 265:4736-4745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iida, T., A. Ohta, and M. Takagi. 1998. Cloning and characterization of an n-alkane-inducible cytochrome P450 gene essential for n-decane assimilation by Yarrowia lipolytica. Yeast 14:1387-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iida, T., T. Sumita, A. Ohta, and M. Takagi. 2000. The cytochrome P450ALK multigene family of an n-alkane-assimilating yeast, Yarrowia lipolytica: cloning and characterization of genes coding for new CYP52 family members. Yeast 16:1077-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanai, T., A. Hara, N. Kanayama, M. Ueda, and A. Tanaka. 2000. An n-alkane-responsive promoter element found in the gene encoding the peroxisomal protein of Candida tropicalis does not contain a C6 zinc cluster DNA-binding motif. J. Bacteriol. 182:2492-2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kogure, T., M. Takagi, and A. Ohta. 2005. n-Alkane and clofibrate, a peroxisome proliferator, activate transcription of ALK2 gene encoding cytochrome P450alk2 through distinct cis-acting promoter elements in Candida maltosa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 329:78-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar, M. B., P. Ramadoss, R. K. Reen, J. P. Vanden Heuvel, and G. H. Perdew. 2001. The Q-rich subdomain of the human Ah receptor transactivation domain is required for dioxin-mediated transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276:42302-42310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebeault, J. M., E. T. Lode, and M. J. Coon. 1971. Fatty acid and hydrocarbon hydroxylation in yeast: role of cytochrome P-450 in Candida tropicalis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 42:413-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lepingle, A., S. Casaregola, C. Neuveglise, E. Bon, H. Nguyen, F. Artiguenave, P. Wincker, and C. Gaillardin. 2000. Genomic exploration of the hemiascomycetous yeasts. 14. Debaryomyces hansenii var. hansenii. FEBS Lett. 487:82-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loewen, C. J., M. L. Gaspar, S. A. Jesch, C. Delon, N. T. Ktistakis, S. A. Henry, and T. P. Levine. 2004. Phospholipid metabolism regulated by a transcription factor sensing phosphatidic acid. Science 304:1644-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma, P. C., M. A. Rould, H. Weintraub, and C. O. Pabo. 1994. Crystal structure of MyoD bHLH domain-DNA complex: perspectives on DNA recognition and implications for transcriptional activation. Cell 77:451-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massari, M. E., and C. Murre. 2000. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:429-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell, P. J., and R. Tjian. 1989. Transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Science 245:371-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murre, C., G. Bain, M. A. van Dijk, I. Engel, B. A. Furnari, M. E. Massari, J. R. Matthews, M. W. Quong, R. R. Rivera, and M. H. Stuiver. 1994. Structure and function of helix-loop-helix proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1218:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson, D. R., L. Koymans, T. Kamataki, J. J. Stegeman, R. Feyereisen, D. J. Waxman, M. R. Waterman, O. Gotoh, M. J. Coon, R. W. Estabrook, I. C. Gunsalus, and D. W. Nebert. 1996. P450 superfamily: update on new sequences, gene mapping, accession numbers and nomenclature. Pharmacogenetics 6:1-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikoloff, D. M., P. McGraw, and S. A. Henry. 1992. The INO2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a helix-loop-helix protein that is required for activation of phospholipid synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohkuma, M., S. Muraoka, T. Tanimoto, M. Fujii, A. Ohta, and M. Takagi. 1995. CYP52 (cytochrome P450alk) multigene family in Candida maltosa: identification and characterization of eight members. DNA Cell Biol. 14:163-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohkuma, M., T. Tanimoto, K. Yano, and M. Takagi. 1991. CYP52 (cytochrome P450alk) multigene family in Candida maltosa: molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the two tandemly arranged genes. DNA Cell Biol. 10:271-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Remacle, J. E., G. Albrecht, R. Brys, G. H. Braus, and D. Huylebroeck. 1997. Three classes of mammalian transcription activation domain stimulate transcription in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J. 16:5722-5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson, K. A., J. I. Koepke, M. Kharodawala, and J. M. Lopes. 2000. A network of yeast basic helix-loop-helix interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:4460-4466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson, K. A., and J. M. Lopes. 2000. SURVEY AND SUMMARY: Saccharomyces cerevisiae basic helix-loop-helix proteins regulate diverse biological processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1499-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan, K. M., and G. D. Birnie. 1996. Myc oncogenes: the enigmatic family. Biochem. J. 314:713-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanglard, D., C. Chen, and J. C. Loper. 1987. Isolation of the alkane inducible cytochrome P450 (P450alk) gene from the yeast Candida tropicalis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 144:251-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwank, S., R. Ebbert, K. Rautenstrauss, E. Schweizer, and H. J. Schuller. 1995. Yeast transcriptional activator INO2 interacts as an Ino2p/Ino4p basic helix-loop-helix heteromeric complex with the inositol/choline-responsive element necessary for expression of phospholipid biosynthetic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:230-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seghezzi, W., C. Meili, R. Ruffiner, R. Kuenzi, D. Sanglard, and A. Fiechter. 1992. Identification and characterization of additional members of the cytochrome P450 multigene family CYP52 of Candida tropicalis. DNA Cell Biol. 11:767-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seghezzi, W., D. Sanglard, and A. Fiechter. 1991. Characterization of a second alkane-inducible cytochrome P450-encoding gene, CYP52A2, from Candida tropicalis. Gene 106:51-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sikkema, J., J. A. de Bont, and B. Poolman. 1995. Mechanisms of membrane toxicity of hydrocarbons. Microbiol. Rev. 59:201-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Souciet, J., M. Aigle, F. Artiguenave, G. Blandin, M. Bolotin-Fukuhara, E. Bon, P. Brottier, S. Casaregola, J. de Montigny, B. Dujon, P. Durrens, C. Gaillardin, A. Lepingle, B. Llorente, A. Malpertuy, C. Neuveglise, O. Ozier-Kalogeropoulos, S. Potier, W. Saurin, F. Tekaia, C. Toffano-Nioche, M. Wesolowski-Louvel, P. Wincker, and J. Weissenbach. 2000. Genomic exploration of the hemiascomycetous yeasts. 1. A set of yeast species for molecular evolution studies. FEBS Lett. 487:3-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sumita, T., T. Iida, S. Yamagami, H. Horiuchi, M. Takagi, and A. Ohta. 2002. YlALK1 encoding the cytochrome P450ALK1 in Yarrowia lipolytica is transcriptionally induced by n-alkane through two distinct cis-elements on its promoter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 294:1071-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka, A., and S. Fukui. 1989. The yeast, 2nd ed., vol. 3, p. 261-287. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Triezenberg, S. J. 1995. Structure and function of transcriptional activation domains. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 5:190-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voronova, A., and D. Baltimore. 1990. Mutations that disrupt DNA binding and dimer formation in the E47 helix-loop-helix protein map to distinct domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4722-4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wagner, C., M. Dietz, J. Wittmann, A. Albrecht, and H. J. Schuller. 2001. The negative regulator Opi1 of phospholipid biosynthesis in yeast contacts the pleiotropic repressor Sin3 and the transcriptional activator Ino2. Mol. Microbiol. 41:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.White, M. J., J. P. Hirsch, and S. A. Henry. 1991. The OPI1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a negative regulator of phospholipid biosynthesis, encodes a protein containing polyglutamine tracts and a leucine zipper. J. Biol. Chem. 266:863-872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yadav, J. S., and J. C. Loper. 1999. Multiple p450alk (cytochrome P450 alkane hydroxylase) genes from the halotolerant yeast Debaryomyces hansenii. Gene 226:139-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamagami, S., T. Iida, Y. Nagata, A. Ohta, and M. Takagi. 2001. Isolation and characterization of acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase gene essential for n-decane assimilation in yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 282:832-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamagami, S., D. Morioka, R. Fukuda, and A. Ohta. 2004. A basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor essential for cytochrome P450 induction in response to alkanes in yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. J. Biol. Chem. 279:22183-22189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]