Abstract

The Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin causes a severe, often fatal illness (enterotoxemia) characterized by cardiac, pulmonary, kidney, and brain edema. In this study, we examined the activities of two neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against the C. perfringens epsilon-toxin. Both antibodies inhibited epsilon-toxin cytotoxicity towards cultured MDCK cells and inhibited the ability of the toxin to form pores in the plasma membranes of cells, as shown by staining cells with the membrane-impermeant dye 7-aminoactinomycin D. Using an antibody competition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), a peptide array, and analysis of mutant toxins, we mapped the epitope recognized by one of the neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to amino acids 134 to 145. The antibody competition ELISA and analysis of mutant toxins suggest that the second neutralizing monoclonal antibody also recognizes an epitope in close proximity to this region. The region comprised of amino acids 134 to 145 overlaps an amphipathic loop corresponding to the putative membrane insertion domain of the toxin. Identifying the epitopes recognized by these neutralizing antibodies constitutes an important first step in the development of therapeutic agents that could be used to counter the effects of the epsilon-toxin.

The Clostridium perfringens species is divided into five types, A through E, based on production of the four “major toxins,” the alpha-, beta-, epsilon-, and iota-toxins (50). Epsilon-toxin is one of the toxins produced by type B and D strains (44). The epsilon-toxin can lead to a fatal illness (enterotoxemia) in a variety of livestock animals, most frequently in sheep (50). Clinical signs in intoxicated sheep may include colic, diarrhea, and numerous neurological symptoms. Postmortem analysis reveals widespread increases in vascular permeability with cerebral, cardiac, pulmonary, and kidney edema (52, 53). Experimental intoxication of mice and rats with epsilon-toxin causes a rapidly fatal illness and pathological changes similar to those seen in livestock (12, 13, 28, 46). The dose of epsilon-toxin required to kill 50% of mice has been estimated at between 65 and 110 ng per kg (27), which indicates that epsilon-toxin is one of the most potent known bacterial protein toxins (14). Despite reports of epsilon-toxin-producing C. perfringens being isolated from humans, it is unclear whether or not epsilon-toxin causes illness in humans (15, 22, 26, 31, 34, 49). Due to the clear threat posed to livestock and the potential threat to human health, the epsilon-toxin is classified as a category B overlap select agent by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

To protect livestock from epsilon-toxin, both a vaccine (based on formalin-inactivated epsilon-toxin) and an equine-derived antitoxin are available. Due to the rapid progression of the disease among livestock animals, treatment is generally not possible or practical, and the emphasis is placed on prevention either by vaccination or by administration of antitoxin to unvaccinated animals in the event of an outbreak of enterotoxemia within a herd (2). Neither the antitoxin nor toxoid is approved for human use. Thus, both of the existing approaches to combat epsilon-toxin-mediated illness (approved for veterinary use) would be of limited value in response to exposure to weaponized epsilon-toxin. Alternative countermeasures are needed that inhibit the activity of the toxin.

In this study, we characterized the inhibition of epsilon-toxin activity in vitro by two monoclonal antibodies, 4D7 and 5B7 (11, 18). These monoclonal antibodies neutralize the cytotoxic activity of epsilon-toxin in animal models of intoxication (1, 18, 46) and have also been used to study epsilon-toxin activity in vitro (11, 45, 46). Using an antibody competition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), a peptide array, and a mutant recombinant epsilon-toxin, we mapped the epitope(s) recognized by the two neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. The epitope(s) recognized by the two antibodies overlaps the putative membrane insertion domain of the epsilon-toxin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of epsilon-prototoxin from C. perfringens.

C. perfringens type B strain ATCC 3626 (NCTC 13110, NCIMB 10691) was cultured anaerobically using the GasPak system (Becton Dickinson) in TGY medium (30 g per liter tryptone, 20 g per liter yeast extract, 5 g per liter dextrose, 0.5 g per liter cysteine) at 37°C. An overnight culture was used to inoculate sterile TGY medium, and the resulting culture was incubated anaerobically for 7 h. The epsilon-prototoxin was purified by a combination of hydrophobic interaction and ion-exchange chromatography as previously described (29), with modifications. Proteins from filter-sterilized culture supernatant were precipitated with 70% ammonium sulfate, and the precipitated proteins were dissolved in 5 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and adjusted to 1 M ammonium sulfate. The protein sample then was applied to a phenyl-Sepharose column. The column was washed with 0.8 M ammonium sulfate in 5 mM Tris (pH 7.5), and the bound proteins were eluted in a single step with 5 mM Tris (pH 7.5). Residual ammonium sulfate was removed from the sample by ultrafiltration against 5 mM Tris (pH 7.5), using Amicon ultracentrifugal filter devices (10,000-molecular-weight cutoff; Millipore). The sample then was applied to a Q-Sepharose column equilibrated in 5 mM Tris (pH 7.5), and the unbound protein fraction containing epsilon-prototoxin was collected. Protein concentrations were determined using the micro-BCA assay (Pierce).

Trypsin treatment of epsilon-prototoxin.

The purified epsilon-prototoxin was activated with trypsin to form the active epsilon-toxin (37). Trypsin-coated agarose beads (Pierce) were washed and resuspended in 5 mM Tris (pH 7.5). Preparations containing the epsilon-prototoxin were incubated with trypsin-agarose at 37°C for various times, and the trypsin-coated beads were removed by centrifugation. Complete mini-protease inhibitor cocktail (EDTA free; Roche) was added to the supernatant to inhibit residual trypsin in the samples.

Immunological reagents.

Anti-epsilon-toxin antibodies 4D7 and 5B7 are of the immunoglobulin G1 isotype and were provided (as ascites) by Paul Hauer, USDA (11, 18). Anti-RPTPβ (an immunoglobulin G1 mouse monoclonal antibody; BD Transduction Laboratories) was used as a negative control antibody. Antibodies (negative control antibodies, anti-epsilon-toxin 4D7, and anti-epsilon-toxin 5B7) were normalized based on reactivity with anti-mouse-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (data not shown). Other antibodies used were obtained from commercial sources: anti-β-actin (AbCam), anti-mouse-HRP conjugate (Amersham), anti-rabbit-HRP conjugate (Bio-Rad), and anti-His6 (Santa Cruz). To fluorescently label the anti-β-actin antibody, it was incubated with a threefold molar excess of IRDye 800CW NHS ester (Li-Cor) at room temperature for 2 h. The reaction was stopped by the addition of hydroxylamine to a final concentration of 150 mM. The labeled antibody was recovered using Zeba desalting spin columns (Pierce Biotechnology). To biotinylate the 5B7 antibody, the antibody was partially purified from ascites fluid using CM Affi-Gel Blue (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The partially purified antibody then was incubated with EZ-Link NHS biotin (Pierce Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The labeled antibody was recovered using Zeba desalting spin columns (Pierce Biotechnology).

Cell culture and cytotoxicity assay.

MDCK cells were cultured in Leibovitz L15 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The cytotoxicity of the purified epsilon-prototoxin and trypsin-activated epsilon-toxin was determined using an MDCK cell culture model, essentially as described previously (4, 29, 30, 37, 38, 40, 41, 47, 48, 51). Using 1 × 104 to 2 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates, epsilon-toxin was added to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Cytotoxicity was determined by staining cells with the metabolic indicator 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Sigma) (32). The toxin dose required to kill 50% of the cell monolayer (CT50) was determined by nonlinear regression analysis (SigmaStat).

Pore formation assay.

Pore formation by epsilon-toxin was assessed based on uptake of cell-impermeant nucleic acid stain as described previously (40, 41, 54), with modifications. Epsilon-toxin was incubated for 1 h at 37°C with medium alone or with medium supplemented with neutralizing or control antibodies. These mixtures then were added to MDCK cells (2 × 104 to 5 × 104 per well) plated in eight-well chamber slides (Becton Dickinson). The cells were incubated at 37°C for 45 min, and then the cells were incubated with the cell-impermeant nucleic acid stain 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) (Molecular Probes) at 37°C for 15 min. In addition to 7-AAD, the ability to detect pore formation by using SytoxGreen or propidium iodide (both from Molecular Probes) (40, 41) was evaluated. Consistently, 7-AAD yielded superior signal-to-noise ratios and was therefore chosen for these studies. Following staining, the medium overlying the cells was removed, the cells were gently washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS at 37°C for 30 min. The cells were washed three times in 150 mM ammonium acetate (5 min for each wash), and then the chambers were removed from the slides and coverslips were applied. Cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

Toxin binding.

Epsilon-toxin was fluorescently labeled with Alexa Fluor 680 succinimidyl ester (Molecular Probes). The purified epsilon-toxin (5 μg per ml) in PBS (pH 8) was incubated with a threefold molar excess of the fluorescent dye at room temperature for 1 h. The reaction was stopped by the addition of hydroxylamine to a final concentration of 150 mM. The labeled protein was recovered using Zeba desalting spin columns (Pierce Biotechnology). Labeled epsilon-toxin (2.5 CT50 units) was incubated for 1 h at room temperature with medium supplemented with neutralizing or control antibodies. These mixtures then were added to 2 × 105 MDCK cells plated in 96-well dishes (to at least five wells each). The cells were incubated at 4°C for 1 h, and the cell monolayers then were washed three times in PBS to remove unbound toxin. The cells were lysed in 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer, and samples from replicate wells were pooled, heated to 95°C for 5 min, and separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). An in-gel Western analysis was performed using anti-β-actin antibody labeled with IRDye 800CW NHS ester. Gels were simultaneously imaged both at 700 nm (to detect Alexa Fluor 680-labeled epsilon-toxin) and at 800 nm (to detect IRDye 800-labeled anti-β-actin), using a Li-Cor Odyssey imager.

Immunological techniques.

An antibody competition ELISA (17) was performed by first adding purified epsilon-toxin to a microtiter dish coated with an anti-epsilon-toxin monoclonal antibody (distinct from 4D7 or 5B7) (Bio-X Diagnostics) and incubating the dish at 37°C for 1 h. The wells were washed three times to remove unbound toxin and then incubated with negative control antibodies, anti-epsilon-toxin antibody 5B7, or anti-epsilon-toxin antibody 4D7 at 37°C for 1 h. The wells were washed three times to remove unbound antibody and then incubated at 37°C for 1 h with biotinylated 5B7 antibody. The wells were washed three times to remove unbound biotinylated antibody, and the bound antibody was detected using HRP-conjugated streptavidin and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (1-Step Turbo TMB-ELISA; Pierce Biotechnology) substrate.

For epitope mapping, 124 overlapping peptides corresponding to the primary amino acid sequence of epsilon-toxin were synthesized on a cellulose membrane (Jerini Peptide Technologies). Each peptide was 12 amino acids long, and each successive peptide overlapped 10 amino acids of the previous peptide. The cellulose membrane was developed according to the manufacturer's instructions, using either a negative control monoclonal antibody or a specific monoclonal antibody directed against epsilon-toxin. Results from immunoblotting and epitope mapping were visualized via enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham).

Cloning, expression, and purification of an inactive recombinant epsilon-prototoxin.

DNA from C. perfringens type B strain ATCC 3626 was used in PCRs with etxB-specific oligonucleotide primers to clone the gene encoding a genetically inactivated (i.e., nonfunctional) epsilon-toxin, Etx-H106P (37). To introduce the inactivating H106P mutation, the etxB gene was PCR amplified in two parts. The first part corresponded to amino acids −13 through 110 and included the H106P mutation; the second part corresponded to amino acids 109 through 298. These two PCR products were ligated together and cloned into the protein expression vector pET22b (Novagen) using standard molecular biological techniques. The resulting protein includes a carboxy-terminal His6 affinity tag. The DNA sequence of the cloned gene was determined, and no mutations other than the H106P substitution were identified.

The Etx-H106P-expressing plasmid was transformed into an Escherichia coli K-12 expression strain, NovaBlue(DE3) (Novagen), along with the plasmid pLysE (encoding bacteriophage T7 lysozyme), and transformants were grown in Terrific broth (containing, per liter, 12 g tryptone, 24 g yeast extract, 4 ml glycerol, 2.31 g KH2PO4, and 12.54 g K2HPO4) supplemented with antibiotics to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.7. Isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) then was added to a final concentration of 1 mM to induce recombinant protein expression, and the culture was grown for another 3 h. The cells were collected, resuspended in 1/20 culture volume of B-PER bacterial protein extraction reagent (Pierce) supplemented with Complete mini-protease inhibitor cocktail (EDTA-free; Roche), and mixed for 10 min at room temperature. The cell debris was pelleted, and the supernatant was recovered. The recombinant epsilon-prototoxin was purified by chromatography on Q-Sepharose followed by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (QIAGEN).

The purified recombinant protein was treated with trypsin and incubated with MDCK cells by the same procedures used to study the epsilon-toxin from C. perfringens. MDCK cells treated with the recombinant protein (200 ng per ml) were indistinguishable from untreated MDCK cells when the cells were stained with MTT (data not shown). Subsequently, a mutation deleting amino acids 134 to 145 [Δ(134-145)] was introduced into the Etx-H106P plasmid by inverse PCR (56).

Regulatory compliance.

These studies were performed with guidance from the Vanderbilt University Institutional Biosafety Committee. The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) establishes requirements for the possession, use, and transfer in the United States of select agents and toxins. Nonfunctional (based on the plain meaning of the term) overlap toxins, such as Etx-H106P, are excluded from the requirements of 42 CFR Part 73, “Possession, Use, and Transfer of Select Agents and Toxins,” [as specified in §73.4(d.2)]. Approval to clone the gene encoding the nonfunctional Etx-H106P mutant protein was granted by the Institutional Biosafety Committee. At no time was the gene encoding wild-type, functional epsilon-prototoxin PCR amplified, cloned into a recombinant vector, or otherwise extracted from the C. perfringens DNA preparation.

The maximum amount of epsilon-toxin (either as active toxin or as prototoxin) in possession at any time during this study was less than 3 mg and thus was excluded from the requirements of 42 CFR Part 73 [as specified in §73.4(d.3)].

RESULTS

Neutralization of epsilon-toxin cytotoxicity.

The epsilon-prototoxin was purified from C. perfringens broth culture supernatant by using hydrophobic interaction and ion-exchange chromatography (Fig. 1A). The identification of the epsilon-prototoxin in the purified sample was confirmed by immunoblotting with an epsilon-toxin-specific monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1B) (18). A smaller protein copurified with the epsilon-prototoxin, and an additional gel-filtration chromatography step failed to separate the two proteins (Fig. 1A and data not shown). As discussed below, this protein did not interfere with subsequent assays of epsilon-toxin activity.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of epsilon-toxin cytotoxicity. The C. perfringens epsilon-prototoxin was purified using a combination of hydrophobic interaction chromatography (phenyl-Sepharose) and anion-exchange chromatography (Q Sepharose) as described in Materials and Methods. A. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining. The positions of molecular mass markers are shown. Lane 1, culture supernatant; lane 2, proteins eluted from phenyl-Sepharose; lane 3, unbound (flowthrough) material from Q Sepharose. An arrowhead indicates the position of the epsilon-prototoxin. B. Immunoblot, using epsilon-toxin-specific monoclonal antibody 5B7 (11, 18), of the same samples analyzed in panel A. The positions of molecular mass markers are shown. C. Purified epsilon-prototoxin from C. perfringens was treated with trypsin as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were removed at 10-min intervals, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by immunoblotting with epsilon-toxin-specific monoclonal antibody 5B7. The positions of molecular mass markers are shown. D. Trypsin-treated epsilon-prototoxin from C. perfringens (6.25 to 200 ng per ml) was added to the medium overlying MDCK cells in 96-well plates, and the cytotoxicity was assessed by staining cells with the metabolic indicator MTT as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the means and standard deviations for triplicate samples and are expressed relative to the staining of cells not treated with toxin.

The epsilon-toxin is expressed and secreted as a precursor (prototoxin) (19). This prototoxin is activated upon cleavage of short peptides from both the amino and the carboxy termini by proteases such as trypsin, chymotrypsin, or C. perfringens λ-protease to form the active toxin (7, 27, 55). Preparations containing the epsilon-prototoxin were incubated with trypsin-agarose at 37°C for various times and analyzed by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 1C, treatment of the epsilon-prototoxin yielded fragments consistent with the well-characterized sites of trypsin cleavage (7, 19). Trypsin treatment of the C. perfringens preparation eliminated the copurifying protein as determined by silver staining of samples separated by SDS-PAGE (data not shown).

The cytotoxicity of the trypsin-activated epsilon-toxin was determined using an MDCK cell culture model followed by staining cells with the metabolic indicator MTT (4, 29, 30, 37, 38, 40, 41, 47, 48, 51). To determine the dose of epsilon-toxin needed to kill 50% of the MDCK cells (CT50), the cells were incubated with serial dilutions of the trypsin-treated epsilon-prototoxin (Fig. 1D). The CT50 was calculated by nonlinear regression analysis of the data presented in Fig. 1D and determined to be 19 ng per ml, in agreement with previously published determinations (38). The MTT staining of MDCK cells treated with epsilon-prototoxin (200 ng per ml) was indistinguishable from the staining of untreated control cells (data not shown).

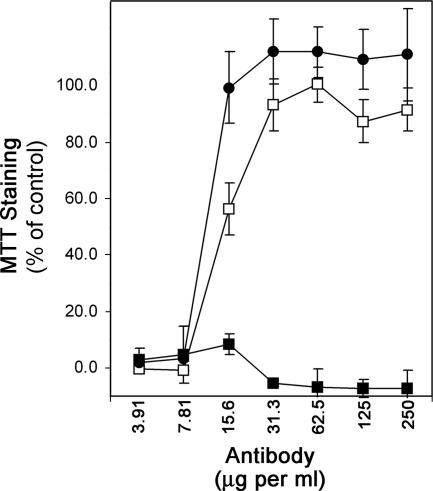

Previous studies showed that the cytotoxic activity of epsilon-toxin can be inhibited by neutralizing antibodies (38). To study this phenomenon in further detail, we examined two mouse monoclonal antibodies (4D7 and 5B7) that are reported to have neutralizing activity (11, 18). Trypsin-activated toxin was incubated with serial dilutions of the neutralizing antibodies or a negative control antibody for 1 hour before being added to MDCK cell monolayers. Following incubation with the toxin, cells were stained with the metabolic indicator MTT. As expected, both the 4D7 and 5B7 antibodies inhibited epsilon-toxin-mediated cytotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2). In contrast, the negative control antibody did not inhibit cytotoxicity at any dose tested.

FIG. 2.

Antibody neutralization of epsilon-toxin cytotoxicity. Epsilon-toxin (2.5 CT50 units) was incubated for 1 h at 37°C with serial dilutions of negative control antibodies (▪), anti-epsilon-toxin 4D7 (□), or anti-epsilon-toxin 5B7 (•). The toxin-antibody mixtures then were added to MDCK cell monolayers and incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Cytotoxicity was assessed by staining cells with the metabolic indicator MTT as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the means and standard deviations for triplicate samples and are expressed relative to the staining of cells not treated with toxin.

The cell death caused by epsilon-toxin is attributed to the formation by the toxin of large pores in the target cell plasma membrane (39-41). In vitro, this pore-forming activity can be detected by monitoring the entry into cells of fluorescent dyes to which cells are normally impermeable (40, 41). To examine the abilities of the neutralizing antibodies to inhibit pore formation by the epsilon-toxin, toxin-treated MDCK cells were stained with the membrane-impermeant nucleic acid-binding dye 7-AAD. The nuclei of MDCK cells are resistant to staining by 7-AAD unless the plasma membrane has been made permeable to the dye; in contrast, the nuclei of cells treated with epsilon-toxin are readily stained with the dye, consistent with pore formation by the toxin (data not shown). To determine whether the neutralizing antibodies inhibit the ability of epsilon-toxin to form pores, toxin was incubated with control antibody or with the neutralizing antibodies, and these mixtures then were added to MDCK cell monolayers. Cells then were treated with 7-AAD and were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Both neutralizing antibodies, but not the negative control antibody, inhibited cell staining by 7-AAD, indicating that the neutralizing antibodies block the ability of epsilon-toxin to form pores (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Pore formation by epsilon-toxin. Neutralizing or negative control antibodies (Ab) (12.5 μg per ml) were incubated with epsilon-toxin (2.5 CT50 units) for 1 h. The toxin-antibody mixtures then were added to MDCK cell monolayers and incubated at 37°C for 45 min. Cells were stained with 7-AAD for 15 min, washed, fixed, and visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

Binding of epsilon-toxin.

We next sought to determine whether the neutralizing antibodies inhibit the ability of epsilon-toxin to interact with MDCK cells. To detect epsilon-toxin in the presence of MDCK cells, trypsin-activated toxin was labeled with Alexa Fluor 680. Serial dilutions of labeled and unlabeled epsilon-toxin were added to MDCK cell monolayers, and the cells then were stained with MTT. No loss in cytotoxic activity was detected following the labeling of the epsilon-toxin with the fluorescent dye, and both 4D7 and 5B7 antibodies were able to neutralize the cytotoxic activity of the labeled toxin (data not shown). To further assess the functionality of the labeled toxin, we examined the ability of fluorescently labeled toxin to bind to cells. Analysis of Alexa Fluor 680-labeled toxin revealed that the toxin bound to MDCK cells at 4°C and that this binding could be inhibited by an excess of unlabeled toxin (data not shown).

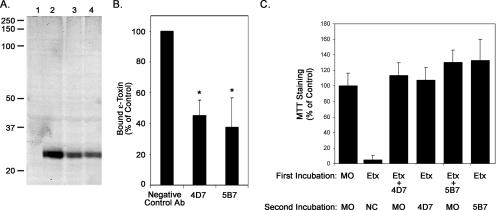

To examine the effect of the neutralizing antibodies on binding of epsilon-toxin to MDCK cells, Alexa Fluor 680-labeled toxin was incubated with neutralizing or control antibody preparations for 1 hour before being added to MDCK cell monolayers. Toxin-treated cells were incubated at 4°C for 1 hour, and the cells then were washed to remove unbound toxin. Cell extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was imaged using a Li-Cor Odyssey imager. In comparison to the negative control antibody, both of the neutralizing antibody preparations reduced the amount of epsilon-toxin bound to cells (Fig. 4, A and B). However, the modest reduction in the amount of epsilon-toxin bound to cells in the presence of the neutralizing antibodies might not be sufficient to account for the lack of cytotoxicity.

FIG. 4.

Binding of epsilon-toxin to MDCK cells. A. Binding of Alexa Fluor 680-labeled epsilon-toxin to MDCK cells at 4°C was assessed as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, MDCK cells alone; lane 2, MDCK cells incubated with the mixture of negative control antibody and epsilon-toxin; lane 3, MDCK cells incubated with the mixture of neutralizing antibody 4D7 and epsilon-toxin; lane 4, MDCK cells incubated with the mixture of neutralizing antibody 5B7 and epsilon-toxin. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated. A representative gel is shown. B. In-gel Western analyses of gels similar to that shown in panel A were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Quantitative analysis was performed using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). Signals were normalized based on the levels of β-actin, and the relative amount of epsilon-toxin bound to MDCK cells was determined. Results represent the means and standard deviations from triplicate gels and are expressed relative to the amount of epsilon-toxin bound in the presence of the negative control antibody (Ab). Data were analyzed by analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. Asterisks denote results significantly different from the control (P < 0.05). C. Antibody neutralization of epsilon-toxin bound to cells. During a first incubation, epsilon-toxin (2.5 CT50 units) (Etx) or mixtures of epsilon-toxin and either of the neutralizing antibodies were added to MDCK cell monolayers at 4°C and left for 1 hour. Cells then were washed three times in 150 mM sodium chloride to remove unbound toxin. During a second incubation, cells that were initially incubated with epsilon-toxin alone now were treated with the negative control antibody (NC) or either of the neutralizing antibodies. In contrast, cells that were initially incubated with toxin-antibody mixtures now were treated with medium only (MO). This second incubation was at 4°C for 1 hour. Cells then were incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Cytotoxicity was assessed by staining cells with the metabolic indicator MTT as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the means and standard deviations for triplicate samples and are expressed relative to the staining of cells not treated with toxin. Differences between cells treated with neutralizing antibody during the first incubation and cells treated with neutralizing antibody during the second incubation were not statistically significant (Student's t test, P > 0.65).

To determine whether the neutralizing antibodies inhibit an event following epsilon-toxin binding to cells, we examined the ability of antibodies 4D7 and 5B7 to inhibit the cytotoxicity of epsilon-toxin previously bound to MDCK cells at 4°C. MDCK cell monolayers were treated with toxin alone at 4°C for 1 hour. Cells then were washed to remove unbound toxin, and the medium overlying the cells was replaced with ice-cold medium containing the negative control or neutralizing antibodies. The cells were incubated at 4°C for 1 hour and then shifted to 37°C for 16 h. The neutralizing antibodies, but not the negative control antibody, inhibited the cytotoxic activity of epsilon-toxin that was first bound to cells in the absence of antibody (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that both neutralizing antibodies inhibited the cytotoxicity of cell-bound epsilon-toxin by blocking an event that occurs after binding of the toxin to cells.

Epitope mapping.

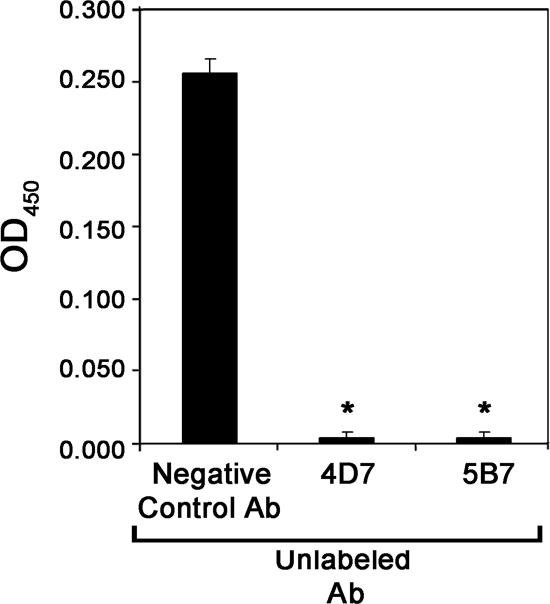

To determine whether the neutralizing monoclonal antibodies 4D7 and 5B7 recognized distinct or overlapping epitopes, an antibody competition experiment was performed (15). In this assay, a microtiter dish coated with anti-epsilon-toxin antibodies was used to bind epsilon-toxin. The wells containing captured epsilon-toxin then were preincubated with control antibodies or with the neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (4D7 and 5B7), and then the ability of biotinylated 5B7 antibody to recognize the toxin was assessed. As expected, preincubation of wells containing the bound epsilon-toxin with unlabeled 5B7 antibody inhibited the binding of the biotinylated 5B7 antibody compared to preincubation with negative control antibody (Fig. 5). More importantly, preincubation of wells containing the bound epsilon-toxin with antibody 4D7 also inhibited the binding of biotinylated 5B7 antibody, suggesting that the epitopes recognized by the two neutralizing antibodies (4D7 and 5B7) are in close proximity to one another. Alternatively, antibody 4D7 bound to epsilon-toxin might sterically hinder binding of antibody 5B7 to a more distant site on the toxin molecule.

FIG. 5.

Antibody competition. Epsilon-toxin was bound to the wells of a microtiter dish coated with anti-epsilon-toxin antibodies. The wells were washed and then incubated with an unlabeled antibody (Ab) (the negative control antibody, the neutralizing antibody 4D7, or the neutralizing antibody 5B7). Unbound antibody was removed by washing, the wells were incubated with biotinylated-5B7 antibody followed by streptavidin-HRP conjugate, and the plate was developed with 1-Step Turbo TMB-ELISA substrate (Pierce Biotechnology). Results represent the means and standard deviations for triplicate samples and were analyzed by analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. Asterisks denote results significantly different from the reaction performed with the negative control antibody (P < 0.05). OD450, optical density at 450 nm.

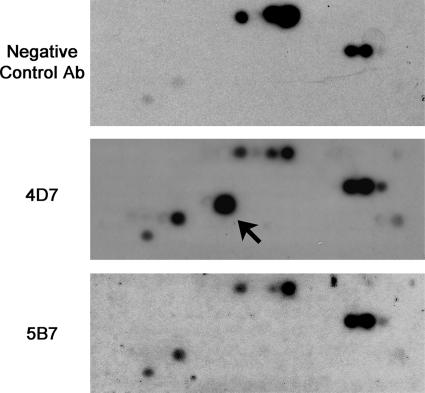

Both neutralizing antibodies recognize epsilon-toxoid in immunoprecipitation experiments (data not shown), suggesting that the antibodies recognize surface-displayed epitopes on the epsilon-toxin in solution. Both neutralizing antibodies also react with denatured epsilon-toxin in immunoblots (Fig. 1 and data not shown), suggesting that linear epitopes are recognized. Based on these observations, we designed an array of 124 overlapping 12-amino-acid peptides corresponding to the amino acid sequence of the epsilon-toxin. These peptides were synthesized on a cellulose membrane, and the membrane was probed sequentially with a negative control antibody, anti-epsilon-toxin antibody 4D7, and anti-epsilon-toxin antibody 5B7. The membrane was stripped between each successive probing to remove bound antibody. The monoclonal antibody 4D7 recognized a unique spot compared with the negative control antibody (Fig. 6). The peptide recognized by antibody 4D7 corresponded to amino acids 134 to 145 (amino acid sequence SFANTNTNTNSK).

FIG. 6.

Epsilon-toxin peptide array. A peptide array consisting of 124 overlapping 12-amino-acid-long peptides corresponding to epsilon-toxin was probed with negative control antibody (Ab), with anti-epsilon-toxin antibody 4D7, or with anti-epsilon-toxin antibody 5B7. The arrow highlights a peptide uniquely recognized by anti-epsilon-toxin antibody 4D7. Two additional spots (in the lower left of the array) are recognized by all three antibody preparations, though the signal when probed with the negative control antibody is much weaker than that when probed with either neutralizing monoclonal antibody.

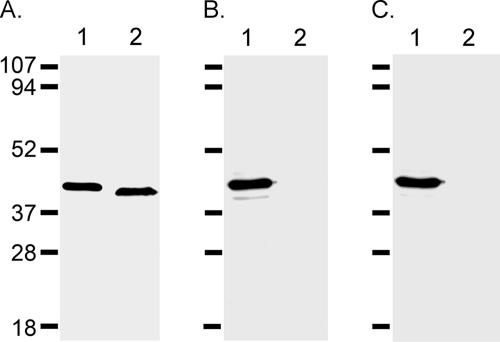

To support the conclusion that antibody 4D7 recognized an epitope within amino acids 134 to 145, we expressed a genetically inactive (i.e., nonfunctional) His6-tagged recombinant epsilon-prototoxin (Etx-H106P [37]) and a mutant derivative in which the recognized peptide sequence was deleted [Etx-H106P Δ(134-145)]. As shown in Fig. 7A, an anti-His6 antibody recognized both recombinant proteins. In contrast, antibody 4D7 recognized Etx-H106P but did not recognize Etx-H106P Δ(134-145) (Fig. 7B). Antibody 5B7 also recognized Etx-H106P but did not recognize Etx-H106P Δ(134-145) (Fig. 7C). The last result is consistent with the conclusion that the epitopes recognized by 4D7 and 5B7 are in close proximity (Fig. 5). The results of these experiments suggest that the neutralizing antibody 4D7 (and possibly 5B7) recognizes an epitope within the amino acid sequence SFANTNTNTNSK.

FIG. 7.

Antibody recognition of mutant epsilon-toxin. E. coli lysates containing recombinant His6-tagged Etx-H106P (lane 1) and recombinant His6-tagged Etx-H106P Δ(134-145) (lane 2) were immunoblotted with anti-His6 (A), with anti-epsilon-toxin 4D7 (B), or with anti-epsilon-toxin 5B7 (C).

DISCUSSION

More than a century ago, Behring and Kitasato demonstrated passive immunity against toxin-mediated diseases (5, 6). To this day, antitoxin antibody therapy is used to treat exposure to some of the most potent bacterial toxins (21). In the case of epsilon-toxin-mediated enterotoxemia, administration of toxin-neutralizing antiserum is used prophylactically to treat unvaccinated animals in the event of an outbreak of enterotoxemia (2). Epitopes recognized by antibodies that neutralize the activities of several select agent toxins have been mapped and provide valuable information that may be used in the development of novel antitoxin therapies (3, 8, 16, 24, 42, 43, 57, 58).

In the present study, we characterized two monoclonal antibodies (4D7 and 5B7) previously shown to neutralize the cytotoxic activity of epsilon-toxin, both in vitro and in vivo (1, 11, 18, 45, 46). In addition to showing that the antibodies neutralized the cytotoxic effects of the epsilon-toxin towards MDCK cells (Fig. 2), we observed that the two neutralizing antibodies inhibited the pore-forming activity of the epsilon-toxin (Fig. 3) and reduced the amount of epsilon-toxin bound to MDCK cells at 4°C (Fig. 4A and B). The bound toxin represented in Fig. 4A may include toxin bound to a receptor through a reversible ligand-receptor interaction as well as toxin that is irreversibly associated with the cell following insertion of the toxin into the plasma membrane. Results from previous studies suggest that the epsilon-toxin does not insert into the membrane to form pores at 4°C (33, 40), making it unlikely that the neutralizing antibodies exhibit a direct inhibitory effect on membrane insertion by the toxin at 4°C. Rather, it appears that the neutralizing antibodies inhibit the interaction between the epsilon-toxin and a receptor (9, 35, 36), either because the epitope(s) recognized by the neutralizing antibodies is directly involved in receptor interaction or because binding of the neutralizing antibodies to the toxin sterically hinders receptor recognition by a separate and distinct receptor-binding domain. However, the reduction in bound toxin in the presence of the neutralizing antibodies (to ∼40% of the control value) does not appear to be sufficient to account for the inhibition of cytotoxicity observed. As illustrated in Fig. 1D, reducing the concentration of toxin from 2.5 CT50 units (47.5 ng per ml) to 19 ng per ml would be expected to reduce the MTT staining only to 50% of the control value. This suggests that, in addition to reducing the amount of toxin bound to cells, the neutralizing antibodies block some step that follows binding. As further evidence of this, we observed that both neutralizing antibodies inhibited the cytotoxicity of epsilon-toxin that had already bound to cells (Fig. 4C). These observations suggest that the neutralizing antibodies inhibit an event that follows the presumed toxin-receptor interaction (e.g., oligomerization or membrane insertion at 4°C).

We mapped the epitope recognized by the neutralizing anti-epsilon-toxin monoclonal antibody 4D7 to an epitope within the peptide sequence SFANTNTNTNSK (amino acids 134 to 145 of the epsilon-toxin). The neutralizing antibody 4D7 recognized a peptide corresponding to amino acids 134 to 145 on a peptide array and failed to recognize a recombinant toxin in which these amino acids had been deleted. Though the neutralizing antibody 5B7 did not recognize a specific peptide on the array, the ability of biotinylated 5B7 antibody to bind epsilon-toxin could be inhibited by prior incubation of the toxin with antibody 4D7. Additionally, antibody 5B7 did not recognize a mutant form of recombinant epsilon-toxin in which amino acids 134 to 145 were deleted. Together, these results suggest that antibody 5B7 might also recognize an epitope within (or overlapping) amino acids 134 to 145. We cannot, however, rule out the possibility that conformational changes within the recombinant Etx-H106P Δ(134-145) protein might account for the failure of the 4D7 and 5B7 antibodies to recognize this mutant protein. It is unclear why the neutralizing antibody 5B7 did not recognize the peptide corresponding to amino acids 134 to 145 (or any other unique peptide) on the peptide array. We speculate that the 5B7 antibody might recognize a conformational epitope and that the conformations adopted by the peptides on the array were not compatible with binding of the 5B7 antibody. Such differences between the folding of isolated peptides and of the toxin molecule may also account for the failure of antibody 4D7 to recognize more than one of the overlapping peptides on the array.

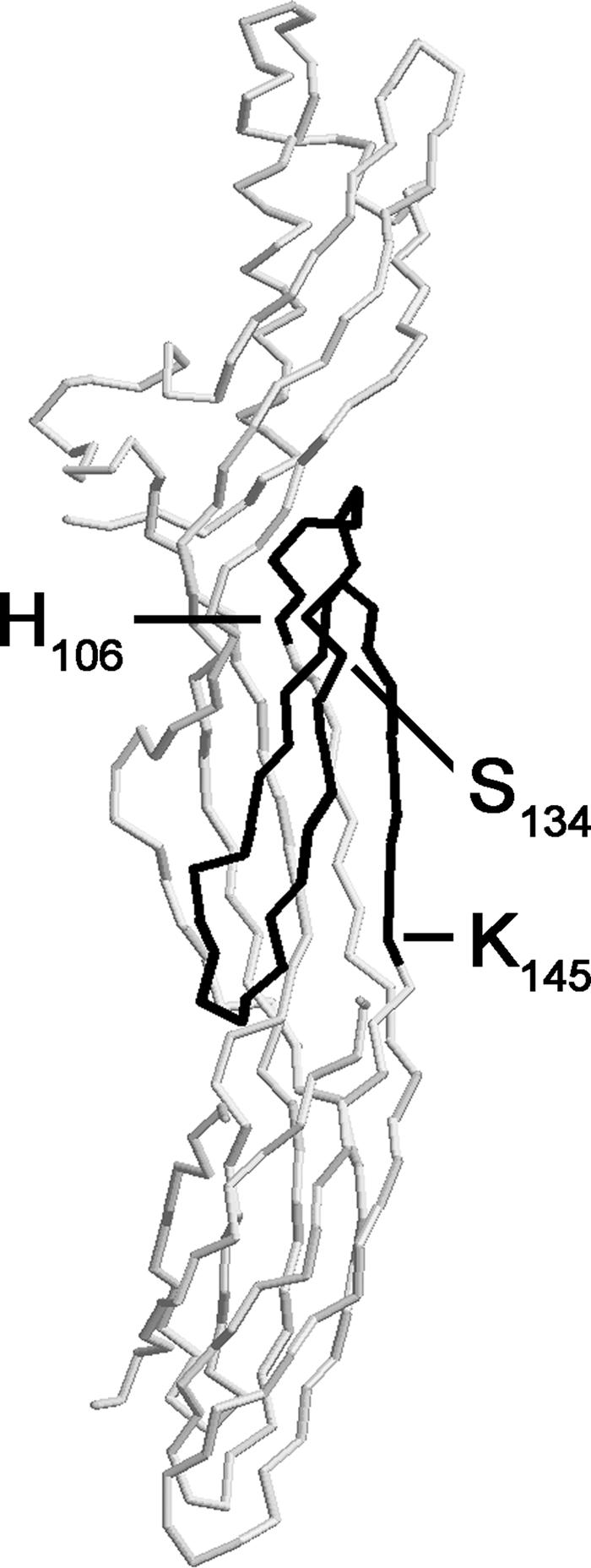

As shown in Fig. 8, the epitope (within or overlapping amino acids 134 to 145) recognized by neutralizing monoclonal antibody 4D7 (and possibly by antibody 5B7) overlaps an amphipathic loop (amino acids 111 to 139). This amphipathic loop is preceded by the histidine at amino acid position 106. Replacement of this histidine by proline renders the toxin inactive (37). Together, these results suggest that the region between amino acids 106 and 145 is important for toxin activity. A similar loop region is found in the structurally related aerolysin family of toxins and in the hemolytic lectin LslA (10, 23). In both aerolysin and the homologous alpha-toxin of Clostridium septicum, this amphipathic loop has been implicated as the membrane-inserting β-hairpin that forms the β-barrel pore in the toxin oligomer (20, 25). Thus, the results of the present study, indicating that the 4D7 and 5B7 antibodies inhibit an event that follows binding of the toxin to cells, block the pore-forming activity of the toxin, and bind to the loop region of the epsilon-toxin, are consistent with a role for the loop region of epsilon-toxin in membrane insertion and pore formation.

FIG. 8.

Mapping of the neutralizing epitope. The structure of the epsilon-toxin is shown (10). The region from the histidine at amino acid position 106 (37) through the predicted membrane-inserting loop (amino acids 111 to 139) (10, 23) to the epitope recognized by neutralizing monoclonal antibodies 4D7 and 5B7 (amino acids 134 to 145) is highlighted.

In future studies, the region of the epsilon-toxin that we have identified as being recognized by the neutralizing antibody 4D7 (and possibly 5B7), and perhaps the extended region from amino acid 106 through 145, may be targeted for the development of new anti-epsilon-toxin reagents that can neutralize toxin activity. For example, humanized antibodies, phage-displayed peptides, or aptamers that specifically recognize this peptide could be selected and examined for the ability to inhibit epsilon-toxin cytotoxicity.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Vanderbilt University Institutional Biosafety Committee for guidance and Paul Hauer (USDA Center for Veterinary Biologics) for providing monoclonal antibodies 4D7 and 5B7.

This work was supported by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Discovery Grant Program (M.S.M.), the National Institutes of Health (grant R21 AI065435 to M.S.M.) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (T.L.C.).

Editor: D. L. Burns

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 January 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson, R. H., J. C. Ly, M. Fernandez-Miyakawa, S. Ochi, J. Sakurai, F. Uzal, and F. E. Curry. 2005. Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin increases permeability of single perfused microvessels of rat mesentery. Infect. Immun. 73:4879-4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiello, S. E. (ed.). 2003. Merck veterinary manual, 8th ed. Merck and Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ.

- 3.Bavari, S., D. D. Pless, E. R. Torres, F. J. Lebeda, and M. A. Olson. 1998. Identifying the principal protective antigenic determinants of type A botulinum neurotoxin. Vaccine 16:1850-1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beal, D. R., R. W. Titball, and C. D. Lindsay. 2003. The development of tolerance to Clostridium perfringens type D epsilon-toxin in MDCK and G-402 cells. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 22:593-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behring, E. 1890. Untersuchungen ueber das Zustandekommen der Diphtherie-Immunitat bei Thieren. Dtsche. Med. Wochenschr. 16:1145-1148. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behring, E., and S. Kitasato. 1890. Ueber das Zustandekommen der Diphtherie-Immunitat und der Tetanus-Immunitat bei thieren. Dtsche. Med. Wochenschr. 16:1113-1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhown, A. S., and A. F. Habeerb. 1977. Structural studies on epsilon-prototoxin of Clostridium perfringens type D. Localization of the site of tryptic scission necessary for activation to epsilon-toxin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 78:889-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brossier, F., M. Levy, A. Landier, P. Lafaye, and M. Mock. 2004. Functional analysis of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen by using neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Infect. Immun. 72:6313-6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buxton, D. 1976. Use of horseradish peroxidase to study the antagonism of Clostridium welchii (Cl. perfringens) type D epsilon toxin in mice by the formalinized epsilon prototoxin. J. Comp. Pathol. 86:67-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole, A. R., M. Gibert, M. Popoff, D. S. Moss, R. W. Titball, and A. K. Basak. 2004. Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin shows structural similarity to the pore-forming toxin aerolysin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:797-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebert, E., V. Oppling, E. Werner, and K. Cussler. 1999. Development and prevalidation of two different ELISA systems for the potency testing of Clostridium perfringens beta and epsilon-toxoid containing veterinary vaccines. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 24:299-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finnie, J. W. 1984. Histopathological changes in the brain of mice given Clostridium perfringens type D epsilon toxin. J. Comp. Pathol. 94:363-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finnie, J. W. 1984. Ultrastructural changes in the brain of mice given Clostridium perfringens type D epsilon toxin. J. Comp. Pathol. 94:445-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill, D. M. 1982. Bacterial toxins: a table of lethal amounts. Microbiol. Rev. 46:86-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gleeson-White, M. H., and J. J. Bullen. 1955. Clostridium welchii epsilon toxin in the intestinal contents of man. Lancet 268:384-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gubbins, M. J., J. D. Berry, C. R. Corbett, J. Mogridge, X. Y. Yuan, L. Schmidt, B. Nicolas, A. Kabani, and R. S. Tsang. 2006. Production and characterization of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies that recognize an epitope in domain 2 of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 47:436-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harlow, E., and D. Lane. 1988. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 18.Hauer, P. J., and N. E. Clough. 1999. Development of monoclonal antibodies suitable for use in antigen quantification potency tests for clostridial veterinary vaccines. Dev. Biol. Stand. 101:85-94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunter, S. E., I. N. Clarke, D. C. Kelly, and R. W. Titball. 1992. Cloning and nucleotide sequencing of the Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin gene and its expression in Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 60:102-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iacovache, I., P. Paumard, H. Scheib, C. Lesieur, N. Sakai, S. Matile, M. W. Parker, and F. G. van der Goot. 2006. A rivet model for channel formation by aerolysin-like pore-forming toxins. EMBO J. 25:457-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller, M. A., and E. R. Stiehm. 2000. Passive immunity in prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:602-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohn, J., and G. H. Warrack. 1955. Recovery of Clostridium welchii type D from man. Lancet 268:385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancheno, J. M., H. Tateno, I. J. Goldstein, M. Martinez-Ripoll, and J. A. Hermoso. 2005. Structural analysis of the Laetiporus sulphureus hemolytic pore-forming lectin in complex with sugars. J. Biol. Chem. 280:17251-17259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGuinness, C. R., and N. J. Mantis. 2006. Characterization of a novel high-affinity monoclonal immunoglobulin G antibody against the ricin B subunit. Infect. Immun. 74:3463-3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melton, J. A., M. W. Parker, J. Rossjohn, J. T. Buckley, and R. K. Tweten. 2004. The identification and structure of the membrane-spanning domain of the Clostridium septicum alpha toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 279:14315-14322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller, C., S. Florman, L. Kim-Schluger, P. Lento, J. De La Garza, J. Wu, B. Xie, W. Zhang, E. Bottone, D. Zhang, and M. Schwartz. 2004. Fulminant and fatal gas gangrene of the stomach in a healthy live liver donor. Liver Transplant. 10:1315-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minami, J., S. Katayama, O. Matsushita, C. Matsushita, and A. Okabe. 1997. Lambda-toxin of Clostridium perfringens activates the precursor of epsilon-toxin by releasing its N- and C-terminal peptides. Microbiol. Immunol. 41:527-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyamoto, O., J. Minami, T. Toyoshima, T. Nakamura, T. Masada, S. Nagao, T. Negi, T. Itano, and A. Okabe. 1998. Neurotoxicity of Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin for the rat hippocampus via the glutamatergic system. Infect. Immun. 66:2501-2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyata, S., O. Matsushita, J. Minami, S. Katayama, S. Shimamoto, and A. Okabe. 2001. Cleavage of a C-terminal peptide is essential for heptamerization of Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin in the synaptosomal membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 276:13778-13783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyata, S., J. Minami, E. Tamai, O. Matsushita, S. Shimamoto, and A. Okabe. 2002. Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin forms a heptameric pore within the detergent-insoluble microdomains of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells and rat synaptosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 277:39463-39468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morinaga, G., T. Nakamura, J. Yoshizawa, and S. Nishida. 1965. Isolation of Clostridium perfringens type D from a case of gas gangrene. J. Bacteriol. 90:826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosmann, T. 1983. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 65:55-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagahama, M., H. Hara, M. Fernandez-Miyakawa, Y. Itohayashi, and J. Sakurai. 2006. Oligomerization of Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin is dependent upon membrane fluidity in liposomes. Biochemistry 45:296-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagahama, M., K. Kobayashi, S. Ochi, and J. Sakurai. 1991. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for rapid detection of toxins from Clostridium perfringens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 68:41-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagahama, M., and J. Sakurai. 1991. Distribution of labeled Clostridium perfringens epsilon toxin in mice. Toxicon 29:211-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagahama, M., and J. Sakurai. 1992. High-affinity binding of Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin to rat brain. Infect. Immun. 60:1237-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oyston, P. C., D. W. Payne, H. L. Havard, E. D. Williamson, and R. W. Titball. 1998. Production of a non-toxic site-directed mutant of Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin which induces protective immunity in mice. Microbiology 144:333-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Payne, D. W., E. D. Williamson, H. Havard, N. Modi, and J. Brown. 1994. Evaluation of a new cytotoxicity assay for Clostridium perfringens type D epsilon toxin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 116:161-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petit, L., M. Gibert, D. Gillet, C. Laurent-Winter, P. Boquet, and M. R. Popoff. 1997. Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin acts on MDCK cells by forming a large membrane complex. J. Bacteriol. 179:6480-6487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petit, L., M. Gibert, A. Gourch, M. Bens, A. Vandewalle, and M. R. Popoff. 2003. Clostridium perfringens epsilon toxin rapidly decreases membrane barrier permeability of polarized MDCK cells. Cell. Microbiol. 5:155-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petit, L., E. Maier, M. Gibert, M. R. Popoff, and R. Benz. 2001. Clostridium perfringens epsilon toxin induces a rapid change of cell membrane permeability to ions and forms channels in artificial lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 276:15736-15740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pless, D. D., E. R. Torres, E. K. Reinke, and S. Bavari. 2001. High-affinity, protective antibodies to the binding domain of botulinum neurotoxin type A. Infect. Immun. 69:570-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rivera, J., A. Nakouzi, N. Abboud, E. Revskaya, D. Goldman, R. J. Collier, E. Dadachova, and A. Casadevall. 2006. A monoclonal antibody to Bacillus anthracis protective antigen defines a neutralizing epitope in domain 1. Infect. Immun. 74:4149-4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rood, J. I. 1998. Virulence genes of Clostridium perfringens. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:333-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosskopf-Streicher, U., P. Volkers, and E. Werner. 2004. Control of Clostridium perfringens vaccines using an indirect competitive ELISA for the epsilon toxin component—examination of the assay by a collaborative study. Pharmeuropa Biol. 2003:91-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sayeed, S., M. E. Fernandez-Miyakawa, D. J. Fisher, V. Adams, R. Poon, J. I. Rood, F. A. Uzal, and B. A. McClane. 2005. Epsilon-toxin is required for most Clostridium perfringens type D vegetative culture supernatants to cause lethality in the mouse intravenous injection model. Infect. Immun. 73:7413-7421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimamoto, S., E. Tamai, O. Matsushita, J. Minami, A. Okabe, and S. Miyata. 2005. Changes in ganglioside content affect the binding of Clostridium perfringens epsilon-toxin to detergent-resistant membranes of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Microbiol. Immunol. 49:245-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shortt, S. J., R. W. Titball, and C. D. Lindsay. 2000. An assessment of the in vitro toxicology of Clostridium perfringens type D epsilon-toxin in human and animal cells. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 19:108-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sidorenko, G. I. 1967. Data on the distribution of Clostridium perfringens in the environment of man. Communication 1. J. Hyg. Epidemiol. Microbiol. Immunol. 11:171-177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith, L. D. S., and B. L. Williams. 1984. The pathogenic anaerobic bacteria, 3rd ed. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, IL.

- 51.Soler-Jover, A., J. Blasi, I. G. de Aranda, P. Navarro, M. Gibert, M. R. Popoff, and M. Martin-Satue. 2004. Effect of epsilon toxin-GFP on MDCK cells and renal tubules in vivo. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 52:931-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Songer, J. G. 1996. Clostridial enteric diseases of domestic animals. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:216-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uzal, F. A., W. R. Kelly, W. E. Morris, J. Bermudez, and M. Baison. 2004. The pathology of peracute experimental Clostridium perfringens type D enterotoxemia in sheep. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 16:403-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walev, I., E. Martin, D. Jonas, M. Mohamadzadeh, W. Muller-Klieser, L. Kunz, and S. Bhakdi. 1993. Staphylococcal alpha-toxin kills human keratinocytes by permeabilizing the plasma membrane for monovalent ions. Infect. Immun. 61:4972-4979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Worthington, R. W., and M. S. Mulders. 1977. Physical changes in the epsilon prototoxin molecule of Clostridium perfringens during enzymatic activation. Infect. Immun. 18:549-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wren, B. W., J. Henderson, and J. M. Ketley. 1994. A PCR-based strategy for the rapid construction of defined bacterial deletion mutants. BioTechniques 16:994-996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu, H. C., C. T. Yeh, Y. L. Huang, L. J. Tarn, and C. C. Lung. 2001. Characterization of neutralizing antibodies and identification of neutralizing epitope mimics on the Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin type A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3201-3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang, J., J. Xu, G. Li, D. Dong, X. Song, Q. Guo, J. Zhao, L. Fu, and W. Chen. 2006. The 2beta2-2beta3 loop of anthrax protective antigen contains a dominant neutralizing epitope. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 341:1164-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]