Abstract

Quorum sensing (QS) in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) regulates the expression of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE). The LEE contains five major operons named LEE1 through LEE5. QseA was previously shown to be activated through QS and to activate the transcription of LEE1. The LEE1 operon encodes Ler, the transcription activator of all other LEE genes, and has two promoters: a distal promoter (P1) and a proximal promoter (P2). We have previously reported that QseA acts on P1 and not P2. To identify the minimal region of LEE1 that is necessary for QseA-mediated activation, a series of nested-deletion constructs of the LEE1 promoter fused to a lacZ reporter were constructed in both the EHEC and E. coli K-12 backgrounds. In an EHEC background, QseA-dependent activation of LEE1 can be observed for the entire regulatory region (beginning at nucleotide −393 and ending at nucleotide −123). In contrast to what occurred in EHEC, in K-12 there was no QseA-dependent activation of LEE1 transcription between base pairs −393 and −343. These data indicate that a QseA-dependent EHEC-specific regulator is required for the activation of transcription in this region. We also observed QseA-dependent LEE1 activation from nucleotides −218 to −123 in K-12, similar to results of the nested-deletion analysis performed with EHEC. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays established that QseA directly binds to the region of LEE1 from bp −173 to −42 and not to the region from bp −393 to −343. These studies suggest that QseA activates the transcription of LEE1 by directly binding upstream of its P1 promoter region.

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) colonizes the large intestine, where it forms attaching and effacing (A/E) lesions. A/E lesions are characterized by the destruction of the microvilli and the rearrangement of the cytoskeleton to form a pedestal-like structure that cups the bacterium (31, 40, 66). A/E lesions are characteristic of EHEC, enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), rabbit EPEC, and Citrobacter rodentium infections (28). The genes involved in the formation of A/E lesions are encoded within a chromosomal pathogenicity island named the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) (36). The LEE region contains five major operons, LEE1, LEE2, LEE3, LEE5, and LEE4 (8, 11, 38), that encode a type III secretion (TTS) system (24), an adhesin (intimin) (25), that adhesin's receptor (Tir) (29), and effector proteins (9, 27, 30, 37, 65). The LEE-encoded TTS system also translocates effector proteins encoded outside the LEE region (NleA, -B, -C, -D, -E, and -F and EspFu, among others); these other effectors are also important for virulence and pedestal formation (4, 6, 7, 14, 15, 19, 41, 53, 64).

EHEC senses three cell-to-cell signals to activate expression of the LEE genes: one is a bacterial autoinducer (AI-3) produced by the normal human gastrointestinal microbial flora, and the others are the host hormones epinephrine/norepinephrine (NE) produced by the host (61). AI-3 is a quorum-sensing (QS) signal produced by several species of bacteria, including commensal E. coli as well as several other intestinal bacterial species (62, 68). Both epinephrine and NE are present in the gastrointestinal tract. NE is synthesized by the adrenergic neurons within the enteric nervous system (13). Epinephrine is synthesized in the central nervous system and in the adrenal medulla; it acts in a systemic manner after being released into the bloodstream, thereby reaching the intestine (46). AI-3 and epinephrine/NE are agonistic signals, and responses to both signals can be blocked by adrenergic antagonists (5, 61, 69). These signals are sensed by sensor kinases in the membrane of EHEC that relay this information to a complex regulatory cascade, culminating in the activation of flagellum regulon, LEE, and Shiga toxin expression (5, 35). One of these sensors is QseC, which autophosphorylates in response to epinephrine, NE, and AI-3 (5). Further QS regulation of the LEE genes is complex and requires QseA (57, 58), which, in concert with several global regulators in EHEC, ensures the correct kinetics of LEE gene expression.

The LEE pathogenicity island undergoes complex regulation in EHEC and EPEC. Although the LEE is regulated in EHEC and EPEC in similar manners, there are some distinct differences in the ways that they regulate this pathogenicity island. EPEC contains three genes borne by a 70-kb virulence plasmid, perA, perB, and perC (plasmid-encoded regulator), with PerC being involved in the activation of expression of the LEE genes (3, 17, 38). GadX, a positive regulator of the glutamate decarboxylase genes in EPEC, plays a repressive role in the regulation of the transcription of per (54). Although the per locus is absent in EHEC, Iyoda and Watanabe (23) observed that EHEC encodes five PerC homologs, renamed PchA, -B, -C, -D, and -E, which positively regulate the expression of the LEE genes.

Transcription of the LEE genes is silenced by the nucleoid protein H-NS. The LEE1 operon encodes Ler, the LEE-encoded regulator, which was shown to be required for the expression of other operons within the LEE by disrupting H-NS-mediated silencing of transcription (3, 10, 12, 20, 38, 50, 59). Ler was shown to activate the transcription of the LEE2, LEE3, LEE4, and LEE5 operons (3, 10, 12, 20, 38, 50, 59), and there are conflicting reports on whether Ler is involved in the autoregulation of its own promoter (1, 2, 10, 38, 60). In EHEC, the LEE1 operon contains two promoters: P1 and P2 (58). The P1 (distal) transcriptional start site (163 base pairs upstream of the translational start site) is common to EHEC and EPEC, while the P2 (proximal) transcriptional start site (32 base pairs upstream of the translational start site) is present only in EHEC (58, 60). In Citrobacter rodentium, a systematic mutagenesis approach was utilized to understand further the complexity of the LEE genes in this system (7). Mutants with deletions in the LEE genes were analyzed for TTS, LEE gene expression, changes in actin polymerization, and virulence in the mouse model. In this analysis, two important regulators were found, orf10 and orf11. Orf10 was renamed GrlR, for global regulator of LEE repressor, while Orf11 was renamed GrlA, for global regulator of LEE activator. This study suggests that GrlA is involved in the activation of the transcription of ler, while GrlR represses the transcription of ler (7). Additionally, Ler activates the transcription of grlRA (1, 10). GrlR and GrlA form hetero- and homodimers in vitro, and recently, Iyoda and Watanabe observed that the ClpXP protease is involved in the positive regulation of the LEE, possibly through the control of the stability of GrlR (22). Further regulation of the LEE genes involves the RpoS alternative sigma factor (22, 60), the RcsCDB and EvgSA two-component systems (43, 63), and the Hha (52) and integration host factor (12) nucleoid proteins EtrA and EivF (71). Posttranscriptional regulation of the LEE genes has also been reported (47, 48).

QseA is a member of the LysR family of regulators and has been shown to activate the transcription of LEE1 and, consequently, the other LEE operons (58). Members of the LysR family of regulators contain a characteristic helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain at the amino terminus, typically within amino acid residues 1 to 65 (51). These proteins also regulate the expression of linked genes from divergent promoters, but this is not always the case, as many activate the expression of unlinked virulence genes (51). LysR proteins have been shown to bind the promoter in proximity to the bacterial RNA polymerase (RNAP) (51). Many members of the LysR family of regulators have also been identified as regulators of virulence factors in pathogenic bacteria. For example, PtxR positively regulates the production of exotoxin A in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (70). AphB, of Vibrio cholerae, is involved in the QS cascade and regulation of the ToxR regulon (32-34). Here we show that QseA activates the transcription of LEE1 and, consequently, ler by two means: by directly binding upstream of the P1 promoter and indirectly binding through a yet-unidentified EHEC-specific factor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The wild-type (WT) EHEC (strain 86-24) (18), an isogenic qseA mutant (strain VS145), and complemented strain VS151 were previously described (58). The E. coli K-12 MC4100 qseA mutant (named FS02) was constructed by allelic exchange using the vector pVS143 (qseA::cat cloned into the R6K plasmid pCVD442), and the mutants were selected on media containing chloramphenicol and 5% sucrose as previously described (58). The qseA mutant (FS02) was complemented with plasmid pVS150 (58), generating strain FS76. All E. coli strains were grown aerobically in LB medium or Dulbecco modified Eagle medium at 37°C. Selective antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin, 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 30 μg ml−1 tetracycline, and 30 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DH5α | Host E. coli strain for cloning experiments | Stratagene |

| TOP10 | Host E. coli strain for pCR Blunt II TOPO | Invitrogen |

| 86-24 | Stx2+ EHEC strain (serotype O157:H7) | 18 |

| VS145 | 86-24 qseA mutant strain | 58 |

| VS151 | VS145 with plasmid pVS150 | 58 |

| MC4100 | araD139 Δ(araABC-leu)7679 galU galK Δ(lac)X74 rpsL thi | 55 |

| FS02 | MC4100 qseA mutant strain | This study |

| FS76 | FS02 with plasmid pVS150 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRS551 | lacZ reporter gene fusion vector | 56 |

| pVS143 | qseA::cat cloned into pCVD442 | 58 |

| pBADMycHis | C-terminal Myc-His tag cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pBlueScriptII | Cloning vector | Stratagene |

| pVS241 | qseA in pBADMycHisA | 57 |

| pVS150 | qseA in pACYC177 | 58 |

| pVS232Z | LEE1::lacZ in pRS551, base pairs −393 to +323 | 60 |

| pVS200 | ler::lacZ in pRS551, base pairs −393 to −42 | This study |

| pVS204 | ler::lacZ in pRS551, base pairs −343 to +86 | This study |

| pVS206 | ler::lacZ in pRS551, base pairs −218 to +86 | This study |

| pVS224 | ler::lacZ in pRS551, base pairs −173 to +86 | This study |

| pVS225 | ler::lacZ in pRS551, base pairs −123 to +86 | This study |

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Standard methods were used to perform plasmid purification, PCR, ligation, restriction digestion, transformation, and DNA gel electrophoresis (49). All oligonucleotide primers are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Oligonucleotide (5′-3′) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| orf1 F | CGGAATTCATGTGCTGCGACTGCGTTCG | 60 |

| ler 2F | CGGAATTCCTGGGGATTCACTCGCTTGC | This study |

| ler 4F | CGGAATTCCGCTTAACTAAATGGAAATGC | This study |

| ler 5F | CGGAATTCAGATGATTTTCTTCCATTTAAT | This study |

| ler 6F | CGGAATTCGATTTTTTTGTTGAGACACAT | This study |

| ler R1 | CGGGATCCTCTATCAAATTAGGACACAT | This study |

| ler R2 | CGGGATCCGTATGGACTTGTTGTATGTG | This study |

| ler R3 | CGGGATCCGTCGGCCTACGCCCGACC | This study |

| ler −173F | CGGGATCCCGATGATTTTCTTCTATATCATTG | This study |

| ler −42R | CGGAATTCCGCGACCTTATCAGGAAGGACC | This study |

| ApR | CGGGATCCGGTGAGCAAAAACAGGAAGG | This study |

| ApF | GGAATTCGAAAGGGCCTCGTG ATA CGC | This study |

Construction of LEE1 or ler deletion lacZ operon fusion constructs.

Transcriptional fusion constructs with the promoterless lacZ gene were made by amplifying regions of the ler promoter using Pfx DNA polymerase, using the primers listed in Table 2, and cloning them into the EcoRI-BamHI restriction sites of plasmid pRS551, which contains a promoterless lacZ cassette (56). This generated plasmids pVS232Z, pVS204, pVS206, pVS224, pVS225, and pVS200, listed in Table 1 (see also Fig. 3). Plasmid pVS232Z was constructed by amplifying the regulatory region of LEE1 from bp −393 to +323 using primers orf1 F and ler R3 and has been described previously (60). Plasmid pVS204 was constructed by amplifying the regulatory region of LEE1 from bp −343 to +86 using primers ler 2F and ler R2. Plasmid pVS206 was constructed by amplifying the regulatory region of LEE1 from bp −218 to +86 using primers ler 4F and ler R2. Plasmid pVS224 was constructed by amplifying the regulatory region of LEE1 from bp −173 to +86 using primers ler 5F and ler R2. Plasmid pVS225 was constructed by amplifying the regulatory region of LEE1 from bp −123 to +86 using primers ler 6F and ler R2. Plasmid pVS200 was constructed by amplifying the regulatory region of LEE1 from bp −393 to −42 using primers orf1 F and ler R1 (see Fig. 3A).

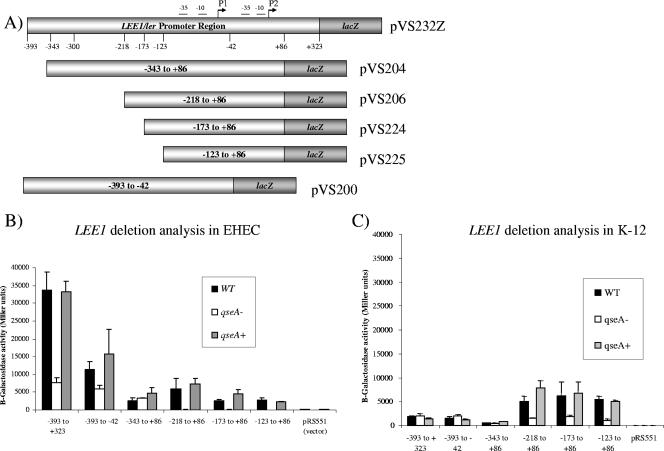

FIG. 3.

(A) Schematic of nested-deletion analysis. The numbering of the bases (−393 to +323) is based on the P2 transcriptional start site. (B) Deletion analysis of the LEE1 promoter in EHEC. Fragments of the LEE1 promoter were electroporated into 86-24 (WT), VS145 (qseA mutant), and VS151 (qseA complemented) and assessed for β-galactosidase activity. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (C) Deletion analysis of the LEE1 promoter in E. coli K-12. Fragments of the LEE1 promoter were transformed into MC4100 (WT), FS02 (qseA mutant), and FS76 (qseA complemented) and assessed for β-galactosidase activity. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

These transcriptional-fusion amplicons were each electroporated into 86-24 (WT EHEC), VS145 (qseA isogenic mutant in 86-24), and VS151 (VS145 with pVS150) for the EHEC deletion analysis. The transcriptional-fusion amplicons were separately transformed into MC4100 (WT K-12), FS02 (qseA isogenic mutant of MC4100), and FS76 (FS02 with pVS150) for the E. coli K-12 deletion analysis (Table 1).

β-Galactosidase activity assay.

The strains containing the transcriptional lacZ fusions were grown in LB in the appropriate selective antibiotic at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0. These cultures were diluted 1:10 in Z buffer (60 mM Na2HP04·7H2O, 40 mM NaH2PO4·H2O, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and assayed for β-galactosidase activity by using o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside as a substrate as previously described (39).

Purification of QseA.

Plasmid pVS241 was constructed by amplifying the qseA gene with Pfx polymerase (Invitrogen) and cloning this amplicon into pBADMycHisA (Invitrogen) digested with XhoI/HindIII (57). To purify the QseA-Myc-His protein, the E. coli strain containing pVS241 was grown at 37°C in LB to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.7, at which point the expression of the protein was induced with 0.2% arabinose for 3 h at 37°C, and subsequently the protein was purified using nickel affinity chromatography under native conditions according to the manufacturer's instructions (QIAGEN).

EMSAs.

In order to study the direct binding of QseA to the promoter of ler, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed using the purified QseA-Myc-His protein and PCR-amplified DNA probes. Taq DNA polymerase was used to amplify the ler promoter base pairs −393 to −42, −173 to −42, and −393 to −300 for a DNA probe from EHEC using primers orf1 F/ler R1, Ler promoter −173F/Ler promoter −42R, and orf1 F/ler R3, respectively. Additionally, the bla region, which served as the negative control, was amplified from pBR322 using primers ApR and ApF. DNA probes were then end labeled using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen). End-labeled probes were run on a 6% polyacrylamide gel, excised, and purified using the QIAGEN PCR purification kit.

EMSAs were performed by adding purified QseA-Myc-His protein (0 to 5 μg) to end-labeled probes (10 ng) at increasing concentrations equivalent to 2 to 15 kcpm per reaction with 5× band shift buffer [5× transcription buffer (60 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 3 mM dithiothreitol, 300 mM KCl, 25 mM MgCl2), 50 ng/μl poly(dI-dC), 500 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (NEB)] and water for 20 min at 4°C. A 5× Ficoll loading buffer (5% Ficoll, 0.1% bromphenol blue) was added to reaction mixtures and immediately loaded onto a 5% polyacrylamide gel that was prerun for 1 h at 50 V and 4°C. The gels were electrophoresed, dried, and exposed within a phosphorimage cassette.

RESULTS

Deletion analysis of the LEE1 operon.

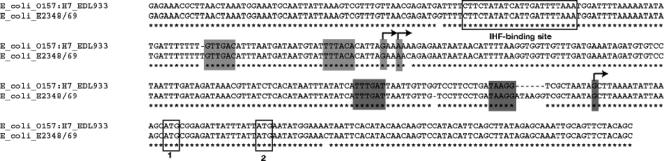

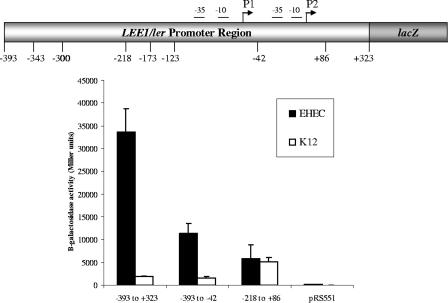

The LEE1 operon encodes Ler, which is the activator of the LEE genes (38). Consequently, environmental regulation of the LEE is thought to occur primarily with the transcriptional control of LEE1. We have previously reported using primer extension experiments to show that the EHEC LEE1 operon has two transcriptional start sites and, consequently, two promoters. The distal P1 promoter is present in both EPEC and EHEC, while the proximal P2 promoter is present only in EHEC (58) (Fig. 1). To validate further these primer extension data, we constructed several LEE1::lacZ transcriptional fusion genes and assessed their levels of transcription within both an EHEC and an E. coli K-12 background. The full-length LEE1 fusion construct from bp −393 to +323 (nucleotides were numbered in relation to the transcriptional start site of P2) yielded 35,000 Miller units of β-galactosidase activity within an EHEC background, but its transcription was highly repressed (by 17.5-fold) in E. coli K-12, yielding 1,989 Miller units (Fig. 2). There was a threefold decrease in the basal-level transcription of LEE1 within an EHEC background with the fusion construct with bp −393 to −42, compared to the level obtained with the construct with bp −393 to +323 (the fragment from bp −393 to −42 lacks the P2 promoter of LEE1). These data corroborate our previous primer extension data (58). The transcription of the fusion construct from bp −393 to −42 is also repressed in E. coli K-12 compared to its transcription in EHEC (Fig. 2). This repression observed in K-12 is relieved only with the fusion construct with bp −218 to +86, suggesting that a repressor present in K-12 acts through the region from bp −393 to −218 of LEE1. Either this repressor is absent in EHEC or an EHEC-specific activator acting through the region from bp −393 to −218 counteracts this repression.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the sequences of the LEE1 regulatory region of EHEC and EPEC. Lightly shaded areas correspond to the distal promoter (P1); darkly shaded areas correspond to the EHEC-specific proximal promoter (P2). Unshaded box 1 corresponds to the assigned ATG based on a longer reading frame; unshaded box 2 corresponds to the ATG that is associated with a putative ribosome binding sequence.

FIG. 2.

Transcription of LEE1::lacZ reporter fusion constructs within an EHEC and an E. coli K-12 background. β-Galactosidase activities are depicted in Miller units, and the numbering of base pairs is in relation to the P2 (proximal) LEE1 promoter transcriptional start site.

We have previously reported, using primer extensions, that QseA acts on P1 and not P2 (58). In order to identify the minimal regulatory region of LEE1 that is necessary for QseA-mediated activation, a series of constructs with nested deletions in the LEE1 promoter was generated (Fig. 3A). These deletion constructs were then fused to a promoterless lacZ cassette and used for nested-deletion analysis of the WT, qseA mutant, and complemented strains in both the EHEC and K-12 backgrounds (Fig. 3A).

In an EHEC background, the transcription of LEE1::lacZ is decreased in the qseA mutant, compared to levels of transcription in the WT and complemented strains, in the promoter fusion constructs with base pairs −218 to +86, −173 to +86, and −123 to +86 (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that the transcription activation of the LEE1 promoter between base pairs −218 and +86 is QseA dependent. Importantly, QseA-dependent activation of P1 can be observed up to nucleotide −123 (which corresponds to nucleotide −50 in P1) (Fig. 3B). This proximity to the promoter suggests that QseA may directly interact with RNAP in P1, which would be consistent with the mechanism of transcriptional regulation reported for other LysR transcriptional regulators (51). Additionally, we observed QseA-dependent regulation of the entire promoter region, as seen using the fusion construct with bp −393 to +323 (Fig. 3B). As mentioned above, there is a threefold decrease in the basal level of transcription of LEE1 in the WT strain with the fusion gene with base pairs −393 to −42 compared to the level in the construct with base pairs −393 to +323, although activation of the fragment from base pairs −393 to −42 is still dependent on QseA. These data further suggest that QseA activates the transcription of the LEE1 operon through the P1 promoter in EHEC (58).

Results of the nested-deletion analysis of E. coli K-12 are shown in Fig. 3C. Using the mutant qseA in K-12 and the complemented strain, we were able to determine whether the levels of regulation of the LEE1 promoter are different between E. coli K-12 and EHEC. In contrast to what occurred in EHEC, QseA-dependent activation of LEE1 transcription was not observed between base pairs −393 and −343 in E. coli K-12 (Fig. 3C). These data indicate that a QseA-dependent EHEC-specific regulator is required for the transcription activation of this region. Transcription of the gene with base pairs −343 to +86 was repressed and QseA independent in both the EHEC and K-12 backgrounds (Fig. 3B and C), suggesting that a conserved, common repressor acts on this region. Hence, the EHEC-specific transcription activator may act through the region at bp −393 to −343 to counteract repression by this common repressor. The transcription of LEE1::lacZ was restored to 5,000 Miller units (levels similar to the ones in EHEC) in the fusion construct with bp −218 to +86 (Fig. 3B and C). We also observed QseA-dependent LEE1 activation from nucleotides −218 and −123 (Fig. 3C), similar to the results of the nested-deletion analysis performed with EHEC (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that QseA may directly bind to the LEE1 promoter between base pairs −123 and −42.

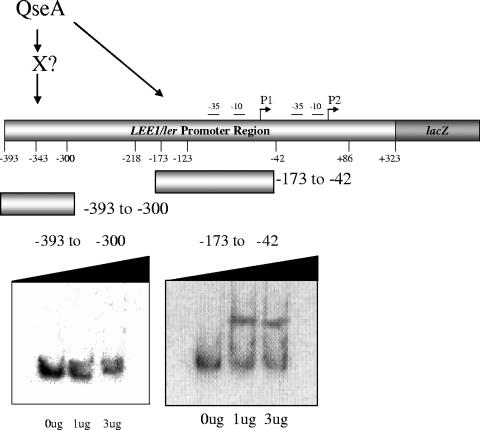

QseA directly binds to LEE1.

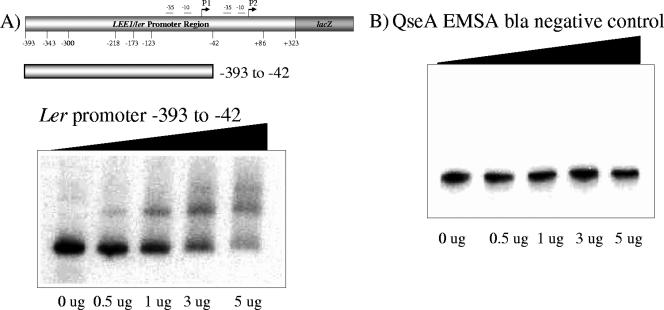

In order to assess whether QseA directly interacts with the LEE1 regulatory region, we performed EMSAs with QseA purified under native conditions. The qseA gene was cloned into the pBADMycHis vector (Invitrogen) to generate a C-terminal Myc-His fusion construct under the control of the araC (pBAD) promoter. The C-terminal fusion was chosen because the helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif of QseA is in the N terminus. QseA was expressed from the resulting vector, pVS241, using 0.2% arabinose and purified using a nickel affinity column under native conditions (Fig. 4A). Plasmid pVS241 has previously been shown to complement QseA-dependent phenotypes in a qseA mutant (57), indicating that the QseA-Myc-His fusion protein is functional.

FIG. 4.

(A) EMSA of the LEE1 promoter fragment containing bp −393 to +42 with increasing amounts of QseA. (B) EMSA of the bla promoter fragment with QseA (negative control).

To determine whether QseA interacts directly with the LEE1 promoter, we initially generated a probe harboring base pairs −393 to −42 of the LEE1 promoter. This region was shown to be important in the QseA-dependent regulation of the LEE1 promoter (Fig. 3). This probe was PCR amplified and end labeled using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen). The constitutive bla promoter fragment was used as a negative control. With the addition of increasing concentrations of the His-tagged QseA protein, a shift of LEE1 promoter region base pairs −393 to −42 was observed (Fig. 4B). The negative-control bla gene did not shift with the addition of increasing concentrations of QseA protein (Fig. 4B), suggesting that QseA binding is specific to the LEE1 promoter (Fig. 4B).

We also performed EMSAs using probes harboring base pairs −393 to −300 and −173 to −42 of LEE1 (Fig. 5). These EMSAs established that QseA directly binds to the region from bp −173 to −42 of LEE1 but not to the region from bp −393 to −300. The region from bp −393 to −300 has been shown to be activated by QseA in EHEC but not in K-12 (Fig. 3). Of note, we also observed that the transcription of LEE1 in the WT EHEC strain with bp −393 to +323 decreased sevenfold relative to that with the fragment from bp −218 to +86 (Fig. 3B), further suggesting that there is another yet-unidentified transcriptional activator acting in the region between bp −393 and −300. These studies allowed us to conclude that QseA activates the transcription of LEE1 by directly binding upstream of its P1 promoter region. In EHEC, QseA also activates the larger transcripts in the region between bp −393 to −300 indirectly, through an unknown activator that is present in EHEC and is absent in E. coli K-12.

FIG. 5.

EMSA of the LEE1 promoter fragments containing bp −393 to −300 and −173 to −42 with increasing amounts of QseA.

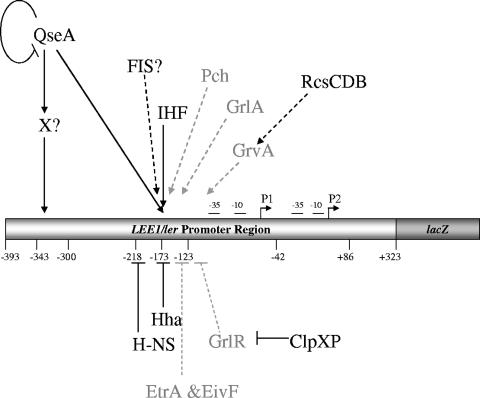

DISCUSSION

QseA is an intermediary transcription factor within the AI-3/epinephrine/NE signaling cascade, which controls virulence gene expression in EHEC (61). QseA was previously described as a transcriptional activator of the LEE through the activation of the LEE1 promoter (58), which encodes the Ler regulator, which is essential for virulence (72). Consequently, an EHEC qseA mutant revealed a striking reduction in TTS compared to that in the WT (58). In addition, using in vivo-induced-antigen technology, John et al. (26) reported that QseA expression is induced during human infection, further underscoring the importance of QseA-mediated regulation for EHEC pathogenesis.

This study aimed to investigate the molecular mechanisms by which QseA activates the transcription of LEE1. Through nested-deletion analyses of the LEE1 promoter within the EHEC and E. coli K-12 backgrounds, a region between base pairs −123 and +86 (numbered according to the P2 transcriptional start site) was shown to be essential for the QseA-dependent transcriptional activation of the ler promoter (Fig. 3). QseA has previously been shown (using primer extension) to control the transcription of LEE1 through the distal (P1) promoter (58). Our nested-deletion analyses of EHEC and K-12 confirmed these previous observations. These studies also showed that transcription of the longer LEE1 constructs is highly repressed within an E. coli K-12 background (Fig. 2 and 3), consequently masking the ability to observe the P1- or P2-dependent transcription of LEE1 in this background (Fig. 2). However, within an EHEC background, we could readily observe a threefold decrease in the transcription of LEE1 in the absence of P2 (Fig. 2), corroborating our previous primer extension data mapping both promoters in LEE1 (58). The transcription repression of the longer LEE1 fusion genes within E. coli K-12 may account for the contrasting results reported by Porter et al. (45) concerning transcription through the LEE1 P2 promoter. Porter et al. used LEE1::lacZ transcription fusion constructs within an E. coli K-12 background starting 362 bp upstream from the LEE1 translational start site, which corresponds to our fusion construct beginning at −343 bp, which is highly repressed in K-12 (Fig. 3). Of note, there is also conflicting information in the literature related to the LEE1 (ler is the first gene within LEE1) translational start site. Elliott et al. (10) assigned the translational start site to the first predicted methionine of ler. In contrast, Perna et al. (44), also taking into consideration the presence of a ribosome binding site consensus sequence upstream of the ATG, assigned the translational start site to the second predicted methionine of ler.

EMSA experiments demonstrated that QseA directly interacts with the region between base pairs −173 and −42 (Fig. 5). We also observed QseA-dependent transcriptional activation at base pairs as close as −123 to +86 of the LEE1 promoter (Fig. 3). The −123 nucleotide corresponds to −50 in relation to the −35 region of the P1 promoter. These data suggest that QseA, a member of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators, binds in close proximity to the P1 promoter and may interact with the RNAP in a fashion similar to that of other LysR-like proteins (42, 51).

QseA was unable to bind in EMSA experiments in the region between base pairs −393 to −300 (Fig. 5), which is activated only in a QseA-dependent fashion in EHEC. These data suggest that QseA regulation of this region is indirect and involves another as-yet-unidentified transcriptional regulator that is absent in E. coli K-12. Given the transcriptional repression observed in the longer fusions (base pairs +393 to −232) in K-12 (Fig. 3C), one possibility is that this EHEC-specific transcription factor counteracts the action of a repressor. The transcriptional regulation of LEE1 is very complex and involves factors shared between EHEC and E. coli K-12, as well as regulators specific to EHEC (some of these are also shared with EPEC and/or C. rodentium). Common regulators with E. coli K-12 include QseA (58), FIS (16), integration host factor (12, 67), H-NS (1, 67), Hha (52), ClpXP (22), and RcsCDB (63) (Fig. 6). There are several transcription factors in EHEC that are absent in E. coli K-12 (as mentioned above, some are shared with EPEC and C. rodentium). These include the Pch regulators (23, 45), GrlA and GrlR (1, 7, 21, 22), GrvA (63), and EtrA and EivF (71) (Fig. 6). However, only the Pch regulators and GrlA (encoded within the LEE region by the grlRA operon) have been shown to activate the transcription of LEE1 (7, 21, 23). Gene array studies (M. Kendall and V. Sperandio, unpublished results) demonstrated that none of the pch genes are regulated by QseA. Using a grlRA::lacZ transcription fusion construct, we established that QseA activates the transcription of GrlR and GrlA (R. Russell and V. Sperandio, unpublished studies). However, direct binding to LEE1 by GrlA has not been demonstrated, and GrlA activates the transcription of LEE1 through the −40 region of P1 (corresponding to the −123 region for P2 in our studies) (1). The EHEC-specific QseA-dependent factor that activates the transcription of LEE1 acts through the region from bp −393 to −300 (Fig. 3); consequently, this factor is also not likely to be GrlA.

FIG. 6.

Schematic depiction of LEE regulation. Factors shown in gray are present in both E. coli K-12 and EHEC (and also in EPEC), while regulators shown in black are specific to EHEC (some are shared with EPEC, e.g., GrlR, GrlA, and Ler). Solid lines represent regulators whose direct interactions with the target promoter have been biochemically defined, and dashed lines represent interactions which occur indirectly or have not yet been shown to bind to the target gene. IHF, integration host factor.

Studies thus far of the intricate regulation of QS in EHEC have shown that many factors are involved in the activation and repression of virulence genes. Here we showed that QseA activates the expression of LEE1 (ler) by binding to a region of DNA in close proximity to the promoter P1, close to the binding site of RNAP. The P1 promoter of LEE1 is present in both EHEC and EPEC. Hence, the observation that QseA activates expression through this promoter is consistent with previous studies indicating that QseA activates the expression of the LEE genes in both EHEC and EPEC (57, 58). This activation by QseA leads to the Ler activation of other genes in the LEE pathogenicity island, which are necessary for TTS and A/E lesion formation. The concerted action of QseA with a plethora of other transcription factors to modulate LEE1 transcription may ensure the correct kinetics of LEE gene expression during infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Rasko and Melissa Kendall for their critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI053067 and an Ellison Medical Foundation award.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barba, J., V. H. Bustamante, M. A. Flores-Valdez, W. Deng, B. B. Finlay, and J. L. Puente. 2005. A positive regulatory loop controls expression of the locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded regulators Ler and GrlA. J. Bacteriol. 187:7918-7930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berdichevsky, T., D. Friedberg, C. Nadler, A. Rokney, A. Oppenheim, and I. Rosenshine. 2005. Ler is a negative autoregulator of the LEE1 operon in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187:349-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bustamante, V. H., F. J. Santana, E. Calva, and J. L. Puente. 2001. Transcriptional regulation of type III secretion genes in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: Ler antagonizes H-NS-dependent repression. Mol. Microbiol. 39:664-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campellone, K. G., D. Robbins, and J. M. Leong. 2004. EspFU is a translocated EHEC effector that interacts with Tir and N-WASP and promotes Nck-independent actin assembly. Dev. Cell 7:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke, M. B., D. T. Hughes, C. Zhu, E. C. Boedeker, and V. Sperandio. 2006. The QseC sensor kinase: a bacterial adrenergic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:10420-10425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahan, S., S. Wiles, R. M. La Ragione, A. Best, M. J. Woodward, M. P. Stevens, R. K. Shaw, Y. Chong, S. Knutton, A. Phillips, and G. Frankel. 2005. EspJ is a prophage-carried type III effector protein of attaching and effacing pathogens that modulates infection dynamics. Infect. Immun. 73:679-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng, W., J. L. Puente, S. Gruenheid, Y. Li, B. A. Vallance, A. Vazquez, J. Barba, J. A. Ibarra, P. O'Donnell, P. Metalnikov, K. Ashman, S. Lee, D. Goode, T. Pawson, and B. B. Finlay. 2004. Dissecting virulence: systematic and functional analyses of a pathogenicity island. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:3597-3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elliott, S. J., S. W. Hutcheson, M. S. Dubois, J. L. Mellies, L. A. Wainwright, M. Batchelor, G. Frankel, S. Knutton, and J. B. Kaper. 1999. Identification of CesT, a chaperone for the type III secretion of Tir in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 33:1176-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott, S. J., E. O. Krejany, J. L. Mellies, R. M. Robins-Browne, C. Sasakawa, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. EspG, a novel type III system-secreted protein from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli with similarities to VirA of Shigella flexneri. Infect. Immun. 69:4027-4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott, S. J., V. Sperandio, J. A. Girón, S. Shin, J. L. Mellies, L. Wainwright, S. W. Hutcheson, T. K. McDaniel, and J. B. Kaper. 2000. The locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator controls expression of both LEE- and non-LEE-encoded virulence factors in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 68:6115-6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott, S. J., L. A. Wainwright, T. K. McDaniel, K. G. Jarvis, Y. K. Deng, L. C. Lai, B. P. McNamara, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1998. The complete sequence of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli E2348/69. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedberg, D., T. Umanski, Y. Fang, and I. Rosenshine. 1999. Hierarchy in the expression of the locus of enterocyte effacement genes of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 34:941-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furness, J. B. 2000. Types of neurons in the enteric nervous system. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 81:87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garmendia, J., and G. Frankel. 2005. Operon structure and gene expression of the espJ-tccP locus of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 247:137-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garmendia, J., A. D. Phillips, M. F. Carlier, Y. Chong, S. Schuller, O. Marches, S. Dahan, E. Oswald, R. K. Shaw, S. Knutton, and G. Frankel. 2004. TccP is an enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 type III effector protein that couples Tir to the actin-cytoskeleton. Cell. Microbiol. 6:1167-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg, M. D., M. Johnson, J. C. Hinton, and P. H. Williams. 2001. Role of the nucleoid-associated protein Fis in the regulation of virulence properties of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 41:549-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gómez-Duarte, O. G., and J. B. Kaper. 1995. A plasmid-encoded regulatory region activates chromosomal eaeA expression in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 63:1767-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin, P. M., S. M. Ostroff, R. V. Tauxe, K. D. Greene, J. G. Wells, J. H. Lewis, and P. A. Blake. 1988. Illnesses associated with Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. A broad clinical spectrum. Ann. Intern. Med. 109:705-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruenheid, S., I. Sekirov, N. A. Thomas, W. Deng, P. O'Donnell, D. Goode, Y. Li, E. A. Frey, N. F. Brown, P. Metalnikov, T. Pawson, K. Ashman, and B. B. Finlay. 2004. Identification and characterization of NleA, a non-LEE-encoded type III translocated virulence factor of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1233-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haack, K. R., C. L. Robinson, K. J. Miller, J. W. Fowlkes, and J. L. Mellies. 2003. Interaction of Ler at the LEE5 (tir) operon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 71:384-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iyoda, S., N. Koizumi, H. Satou, Y. Lu, T. Saitoh, M. Ohnishi, and H. Watanabe. 2006. The GrlR-GrlA regulatory system coordinately controls the expression of flagellar and LEE-encoded type III protein secretion systems in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188:5682-5692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iyoda, S., and H. Watanabe. 2005. ClpXP protease controls expression of the type III protein secretion system through regulation of RpoS and GrlR levels in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187:4086-4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iyoda, S., and H. Watanabe. 2004. Positive effects of multiple pch genes on expression of the locus of enterocyte effacement genes and adherence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 to HEp-2 cells. Microbiology 150:2357-2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarvis, K. G., J. A. Giron, A. E. Jerse, T. K. McDaniel, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1995. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli contains a putative type III secretion system necessary for the export of proteins involved in attaching and effacing lesion formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7996-8000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jerse, A. E., J. Yu, B. D. Tall, and J. B. Kaper. 1990. A genetic locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli necessary for the production of attaching and effacing lesions on tissue culture cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:7839-7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.John, M., I. T. Kudva, R. W. Griffin, A. W. Dodson, B. McManus, B. Krastins, D. Sarracino, A. Progulske-Fox, J. D. Hillman, M. Handfield, P. I. Tarr, and S. B. Calderwood. 2005. Use of in vivo-induced antigen technology for identification of Escherichia coli O157:H7 proteins expressed during human infection. Infect. Immun. 73:2665-2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanack, K. J., J. A. Crawford, I. Tatsuno, M. A. Karmali, and J. B. Kaper. 2005. SepZ/EspZ is secreted and translocated into HeLa cells by the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli type III secretion system. Infect. Immun. 73:4327-4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaper, J. B., J. P. Nataro, and H. L. Mobley. 2004. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:123-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenny, B., R. DeVinney, M. Stein, D. J. Reinscheid, E. A. Frey, and B. B. Finlay. 1997. Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell 91:511-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenny, B., and M. Jepson. 2000. Targeting of an enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) effector protein to host mitochondria. Cell. Microbiol. 2:579-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knutton, S., M. M. Baldini, J. B. Kaper, and A. S. McNeish. 1987. Role of plasmid-encoded adherence factors in adhesion of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to HEp-2 cells. Infect. Immun. 55:78-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovacikova, G., W. Lin, and K. Skorupski. 2004. Vibrio cholerae AphA uses a novel mechanism for virulence gene activation that involves interaction with the LysR-type regulator AphB at the tcpPH promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 53:129-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovacikova, G., W. Lin, and K. Skorupski. 2003. The virulence activator AphA links quorum sensing to pathogenesis and physiology in Vibrio cholerae by repressing the expression of a penicillin amidase gene on the small chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 185:4825-4836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovacikova, G., and K. Skorupski. 1999. A Vibrio cholerae LysR homolog, AphB, cooperates with AphA at the tcpPH promoter to activate expression of the ToxR virulence cascade. J. Bacteriol. 181:4250-4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyte, M., B. P. Arulanandam, and C. D. Frank. 1996. Production of Shiga-like toxins by Escherichia coli O157:H7 can be influenced by the neuroendocrine hormone norepinephrine. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 128:392-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDaniel, T. K., K. G. Jarvis, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1995. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1664-1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNamara, B. P., and M. S. Donnenberg. 1998. A novel proline-rich protein, EspF, is secreted from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli via the type III export pathway. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 166:71-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mellies, J. L., S. J. Elliott, V. Sperandio, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1999. The Per regulon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: identification of a regulatory cascade and a novel transcriptional activator, the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator (Ler). Mol. Microbiol. 33:296-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 40.Moon, H. W., S. C. Whipp, R. A. Argenzio, M. M. Levine, and R. A. Giannella. 1983. Attaching and effacing activities of rabbit and human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pig and rabbit intestines. Infect. Immun. 41:1340-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mundy, R., C. Jenkins, J. Yu, H. Smith, and G. Frankel. 2004. Distribution of espI among clinical enterohaemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:1145-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muraoka, S., R. Okumura, N. Ogawa, T. Nonaka, K. Miyashita, and T. Senda. 2003. Crystal structure of a full-length LysR-type transcriptional regulator, CbnR: unusual combination of two subunit forms and molecular bases for causing and changing DNA bend. J. Mol. Biol. 328:555-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nadler, C., Y. Shifrin, S. Nov, S. Kobi, and I. Rosenshine. 2006. Characterization of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli mutants that fail to disrupt host cell spreading and attachment to substratum. Infect. Immun. 74:839-849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perna, N. T., G. F. Mayhew, G. Pósfai, S. Elliott, M. S. Donnenberg, J. B. Kaper, and F. R. Blattner. 1998. Molecular evolution of a pathogenicity island from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 66:3810-3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porter, M. E., P. Mitchell, A. J. Roe, A. Free, D. G. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2004. Direct and indirect transcriptional activation of virulence genes by an AraC-like protein, PerA from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1117-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Purves, D., D. Fitzpatrick, S. M. Williams, J. O. McNamara, G. J. Augustine, L. C. Katz, and A. LaMantia. 2001. Neuroscience, 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, MA.

- 47.Roe, A. J., S. W. Naylor, K. J. Spears, H. M. Yull, T. A. Dransfield, M. Oxford, I. J. McKendrick, M. Porter, M. J. Woodward, D. G. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2004. Co-ordinate single-cell expression of LEE4- and LEE5-encoded proteins of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol. Microbiol. 54:337-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roe, A. J., H. Yull, S. W. Naylor, M. J. Woodward, D. G. E. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2003. Heterogeneous surface expression of EspA translocon filaments by Escherichia coli O157:H7 is controlled at the posttranscriptional level. Infect. Immun. 71:5900-5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 50.Sánchez-SanMartín, C., V. H. Bustamante, E. Calva, and J. L. Puente. 2001. Transcriptional regulation of the orf19 gene and the tir-cesT-eae operon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:2823-2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schell, M. A. 1993. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:597-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma, V. K., and R. L. Zuerner. 2004. Role of hha and ler in transcriptional regulation of the esp operon of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Bacteriol. 186:7290-7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shaw, R. K., K. Smollett, J. Cleary, J. Garmendia, A. Straatman-Iwanowska, G. Frankel, and S. Knutton. 2005. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli type III effectors EspG and EspG2 disrupt the microtubule network of intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 73:4385-4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shin, S., M. P. Castanie-Cornet, J. W. Foster, J. A. Crawford, C. Brinkley, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. An activator of glutamate decarboxylase genes regulates the expression of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence genes through control of the plasmid-encoded regulator, Per. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1133-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silhavy, T. J., and J. R. Beckwith. 1985. Uses of lac fusions for the study of biological problems. Microbiol. Rev. 49:398-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simons, R. W., F. Houman, and N. Kleckner. 1987. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene 53:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sircili, M. P., M. Walters, L. R. Trabulsi, and V. Sperandio. 2004. Modulation of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence by quorum sensing. Infect. Immun. 72:2329-2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sperandio, V., C. C. Li, and J. B. Kaper. 2002. Quorum-sensing Escherichia coli regulator A: a regulator of the LysR family involved in the regulation of the locus of enterocyte effacement pathogenicity island in enterohemorrhagic E. coli. Infect. Immun. 70:3085-3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sperandio, V., J. L. Mellies, R. M. Delahay, G. Frankel, J. A. Crawford, W. Nguyen, and J. B. Kaper. 2000. Activation of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) LEE2 and LEE3 operons by Ler. Mol. Microbiol. 38:781-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sperandio, V., J. L. Mellies, W. Nguyen, S. Shin, and J. B. Kaper. 1999. Quorum sensing controls expression of the type III secretion gene transcription and protein secretion in enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:15196-15201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sperandio, V., A. G. Torres, B. Jarvis, J. P. Nataro, and J. B. Kaper. 2003. Bacteria-host communication: the language of hormones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:8951-8956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tannock, G. W., S. Ghazally, J. Walter, D. Loach, H. Brooks, G. Cook, M. Surette, C. Simmers, P. Bremer, F. Dal Bello, and C. Hertel. 2005. Ecological behavior of Lactobacillus reuteri 100-23 is affected by mutation of the luxS gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8419-8425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tobe, T., H. Ando, H. Ishikawa, H. Abe, K. Tashiro, T. Hayashi, S. Kuhara, and N. Sugimoto. 2005. Dual regulatory pathways integrating the RcsC-RcsD-RcsB signalling system control enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli pathogenicity. Mol. Microbiol. 58:320-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tobe, T., S. A. Beatson, H. Taniguchi, H. Abe, C. M. Bailey, A. Fivian, R. Younis, S. Matthews, O. Marches, G. Frankel, T. Hayashi, and M. J. Pallen. 2006. An extensive repertoire of type III secretion effectors in Escherichia coli O157 and the role of lambdoid phages in their dissemination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:14941-14946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tu, X., I. Nisan, C. Yona, E. Hanski, and I. Rosenshine. 2003. EspH, a new cytoskeleton-modulating effector of enterohaemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 47:595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tzipori, S., I. K. Wachsmuth, C. Chapman, R. Birden, J. Brittingham, C. Jackson, and J. Hogg. 1986. The pathogenesis of hemorrhagic colitis caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7 in gnotobiotic piglets. J. Infect. Dis. 154:712-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Umanski, T., I. Rosenshine, and D. Friedberg. 2002. Thermoregulated expression of virulence genes in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiology 148:2735-2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walters, M., M. P. Sircili, and V. Sperandio. 2006. AI-3 synthesis is not dependent on luxS in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188:5668-5681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Walters, M., and V. Sperandio. 2006. Autoinducer 3 and epinephrine signaling in the kinetics of locus of enterocyte effacement gene expression in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 74:5445-5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williams, S. C., E. K. Patterson, N. L. Carty, J. A. Griswold, A. N. Hamood, and K. P. Rumbaugh. 2004. Pseudomonas aeruginosa autoinducer enters and functions in mammalian cells. J. Bacteriol. 186:2281-2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang, L., R. R. Chaudhuri, C. Constantinidou, J. L. Hobman, M. D. Patel, A. C. Jones, D. Sarti, A. J. Roe, I. Vlisidou, R. K. Shaw, F. Falciani, M. P. Stevens, D. L. Gally, S. Knutton, G. Frankel, C. W. Penn, and M. J. Pallen. 2004. Regulators encoded in the Escherichia coli type III secretion system 2 gene cluster influence expression of genes within the locus for enterocyte effacement in enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 72:7282-7293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu, C., S. Feng, T. E. Thate, J. B. Kaper, and E. C. Boedeker. 2006. Towards a vaccine for attaching/effacing Escherichia coli: a LEE encoded regulator (ler) mutant of rabbit enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is attenuated, immunogenic, and protects rabbits from lethal challenge with the WT virulent strain. Vaccine 24:3845-3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]