Abstract

Burkholderia cenocepacia is a gram-negative, non-spore-forming bacillus and a member of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. B. cenocepacia can survive intracellularly in phagocytic cells and can produce at least one superoxide dismutase (SOD). The inability of O2− to cross the cytoplasmic membrane, coupled with the periplasmic location of Cu,ZnSODs, suggests that periplasmic SODs protect bacteria from superoxide that has an exogenous origin (for example, when cells are faced with reactive oxygen intermediates generated by host cells in response to infection). In this study, we identified the sodC gene encoding a Cu,ZnSOD in B. cenocepacia and demonstrated that a sodC null mutant was not sensitive to a H2O2, 3-morpholinosydnonimine, or paraquat challenge but was killed by exogenous superoxide generated by the xanthine/xanthine oxidase method. The sodC mutant also exhibited a growth defect in liquid medium compared to the parental strain, which could be complemented in trans. The mutant was killed more rapidly than the parental strain was killed in murine macrophage-like cell line RAW 264.7, but killing was eliminated when macrophages were treated with an NADPH oxidase inhibitor. We also confirmed that SodC is periplasmic and identified the metal cofactor. B. cenocepacia SodC was resistant to inhibition by H2O2 and was unusually resistant to KCN for a Cu,ZnSOD. Together, these observations establish that B. cenocepacia produces a periplasmic Cu,ZnSOD that protects this bacterium from exogenously generated O2− and contributes to intracellular survival of this bacterium in macrophages.

Burkholderia cenocepacia (54) is a member of the Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc), a group of closely related gram-negative, non-spore-forming bacilli comprising at least nine species (55). Bcc bacteria are multi-drug-resistant opportunistic pathogens, particularly in patients suffering from cystic fibrosis (27) and chronic granulomatous disease (51). Cystic fibrosis patients infected with Bcc organisms exhibit a significantly greater decline in pulmonary function than noninfected patients (12), and consequently they have increased morbidity and mortality (11). The cystic fibrosis lung is a highly oxidative environment due to the persistent infiltration of massive numbers of neutrophils and the sustained inflammatory response associated with chronic infection (4, 9, 10).

Toxic reactive species, such as superoxide (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH−), are produced during the metabolism of oxygen in aerobic organisms (26). These by-products can be bactericidal due to damage of cellular proteins, membranes, and nucleic acids. Bacteria produce an arsenal of specialized enzymes to combat toxic oxygen intermediates. These enzymes include catalase, catalase-peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase (SOD). SOD detoxifies the O2− anion via a dismutation reaction generating H2O2 and O2 (21) and is a key component of cellular defense against O2−. Several classes of SODs are distinguished by their metal cofactors and cellular locations. SodA and SodB are cytoplasmic SODs containing Mn2+ (MnSOD) and Fe3+ (FeSOD), respectively, while SodC is a periplasmic Cu2+- and Zn2+-containing SOD (Cu,ZnSOD). Experimental evidence indicates that bacterial SODs detoxify O2− only in the intracellular compartment in which they reside (39). MnSOD and FeSODs are differentially regulated but have overlapping roles in protecting bacteria from O2− adventitiously generated inside the cell under aerobic conditions. Inactivation of both the sodB and sodA genes in Escherichia coli leads to enhanced susceptibility to oxidative stress, increased mutation rates, and growth defects on minimal media because O2− inactivates enzymes required for the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids (7). In contrast, Cu,ZnSOD is not required for bacterial growth under laboratory conditions and does not appear to play a role in the detoxification of O2− produced intracellularly (17, 48).

The inability of O2− to cross the cytoplasmic membrane, coupled with the periplasmic location of Cu,ZnSODs, has led to the proposal that periplasmic and membrane-associated SODs most likely protect bacteria from O2− that has an exogenous origin (52). Such a detoxification system would clearly be advantageous for intracellular pathogens. Professional phagocytes produce a range of reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen intermediates. These molecules include nitric oxide, produced by inducible nitric oxide synthase, and superoxide O2−, formed by the phagocytic NADPH oxidase complex. The hypothesis that Cu,ZnSODs play a role pathogenesis is supported by the results of an increasing number of studies in which sodC null mutants of several pathogenic organisms have exhibited attenuated virulence in animal models of infection (1, 14, 16, 17, 22, 48). It is therefore reasonable to predict that periplasmic and membrane-associated SODs could protect periplasmic bacterial targets from superoxide attack in the phagosomal compartment.

Bcc species can persist in amoebae (31, 42), human respiratory epithelial cells (5, 28), a human monocytic cell line (43), and the oxidative environment found within macrophages (30, 46). The mechanisms that allow Bcc to resist the bactericidal activity of macrophages are not well understood yet. Enzymes that detoxify reactive oxygen intermediates are likely to contribute to the ability of Bcc to persist within phagocytic cells. Burkholderia spp. possess a number of antioxidant enzymes, including KatA and KatB, heme-containing catalase-peroxidases, AhpC (an alkyl-hydroperoxide reductase), and at least two SODs (34, 35, 37, 38).

In this study, we identified and characterized a periplasmic Cu,ZnSOD (SodC) from B. cenocepacia K56-2. We created a sodC mutant strain, KEK1, and determined the role of B. cenocepacia SodC in protecting bacterial cells from oxidative damage in vitro and in contributing to intracellular survival in a murine macrophage cell line.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents, bacterial strains, macrophage cell line, and culture conditions.

Chemicals and reagents used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, unless indicated otherwise. Bacterial strains and plasmids are described in Table 1. B. cenocepacia strain K56-2 (formerly B. cepacia complex genomovar III) was originally isolated from a cystic fibrosis patient. E. coli and B. cenocepacia strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. Trimethoprim (50 μg ml−1 for E. coli and 100 μg ml−1 for B. cenocepacia) was added during selection for the SOD mutant. Tetracycline (20 μg ml−1 for E. coli and 100 μg ml−1 for B. cenocepacia) was added during selection of the complementing plasmid pKK21. Gentamicin (50 μg ml−1) was used during triparental mating experiments. Bacterial growth was measured by monitoring the optical density at 600 nm in triplicate cultures. Murine macrophage-like cell line RAW 264.7 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA. Macrophages were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Wisent Inc., St. Bruno, Quebec, Canada).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 ΔgyrA96 relA1 | Laboratory stock |

| SY327 | araD Δ(lac pro) argE(Am) recA56 rifR nalA λ pir | Laboratory stock |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm(λDE3) | Laboratory stock |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia strains | ||

| K56-2 | ET12 clone, cystic fibrosis clinical isolate | BCRRCb |

| KEK1 | K56-2 sodC::pKK2, Tpr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGPΩTp | oriR6K, Tpr | R. Flannagan and M. A. Valvano, unpublished data |

| pRedCm | oripBBR1, Tpr ΩCmr, PDHFR, MRFP1 | R. Flannagan and M. A. Valvano, unpublished data |

| pDA17 | oripBBR1, PDHFR, Tetr | D. Aubert and M. A. Valvano, unpublished data |

| pKK1 | pET28a sodC, Kmr | This study |

| pKK2 | pGPΩTp, 299-bp sodC mutagenesis fragment | This study |

| pKK21 | pDA17 sodCFLAG | This study |

| pKK39 | pUC18 sodCFLAG | This study |

| pKK42 | pUC18 C29G sodCFLAG | This study |

| pKK44 | KEK1 C29G sodCFLAG | This study |

| pRK2013 | RK2 derivative, oriColE1, Kmr, mob+tra+ | 19 |

| pET28a | C- or N-terminal six-His tag, T7 promoter, Kmr | Novagen |

| pUC18 | Apr pMB1 rep, lacZ | Fermentas |

Cm, chloramphenicol; Km, kanamycin; Tet, tetracycline; Tp, trimethoprim.

BCRRC, B. cepacia Complex Research and Referral Repository for Canadian CF Clinics.

Bioinformatics.

BLAST-X searches of the B. cenocepacia strain J2315 genome were performed using the nucleotide sequences of sod genes from other gram-negative organisms as the query sequences. Putative SODs were then screened for the presence of SOD motifs using the PROSITE protein family and motif database (http://www.expasy.org/prosite/). Amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalW (8).

PCR amplification.

PCR amplification was performed with a PTC-0200 DNA engine (MJ Research) using either Pwo polymerase (Roche) or Taq polymerase (QIAGEN), the Q solution for G+C-rich templates, and Bcc chromosomal DNA as a template. The DNA sequences of oligonucleotide primers are shown in Table 2. The specific PCR conditions were optimized for each primer pair. PCR amplification products were separated on 0.7% agarose gels and were purified using a QiaQuick gel extraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (QIAGEN).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea | Restriction site | Melting temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1702 | AAATCTAGAGTGCGGTGACGTTCGTCGAGCGC | XbaI | 68 |

| 1703 | AAAGAATTCCCAGCGCCGCACGGTTCATCG | EcoRI | 64 |

| 1762 | TTTTTCTAGATCAACGGATCACGCCGCAGGCCAG | XbaI | 68 |

| 1300 | TAACGGTTGTGGACAACAAGCCAGGG | 65 | |

| 2375 | AAAAGAATTCATGAAACAACGACATCACGGCG | EcoRI | 60 |

| 2376 | AAAATCTAGAACGGATCACGCCGCAGGCCAG | XbaI | 67 |

| 1631 | ACTCTCGCATGGGGAGACCC | 66 | |

| 2199 | AAAACCATGGGACAACGACATCACGGCGTG | NcoI | 67 |

| 2200 | AAAGCGGCCGCACGGATCACGCCGCAGGCCAG | NotI | 68 |

| 2602 | GGCCTGCTGGCGCCCGGTACCTCCTTTTCCTCG | 85 | |

| 2603 | CGAGGAAAAGGAGGTACCGCCGGCCAGCAGGCC | 85 | |

| M13rev | AGGAAACAGCTATGACGAT | 56 | |

| T7prom | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG | 43 | |

| T7term | GCTAGTTATTGCTCAGCGG | 44 |

The underlined sequences are restriction sites.

Construction of a sodC mutant of B. cenocepacia.

pGPΩTp, a derivative of pGP704 that carries the Pir-dependent R6K origin of replication and the dhfr gene flanked by terminator sequences, was used to disrupt sodC. A 299-bp internal fragment of the sodC gene of B. cenocepacia K56-2 was amplified by PCR using primers 1702 and 1703. The product was ligated into the EcoRI and XbaI sites of pGPΩTp and transformed into E. coli SY327. Trimethoprim-resistant colonies were screened by restriction digestion and PCR using primers 1300 and 1703 to confirm the presence of the sodC internal fragment. Plasmid pKK2, containing the sodC internal fragment, was transferred to B. cenocepacia K56-2 by triparental mating (13). Exconjugants with pKK2 integrated into the K56-2 genome were selected on LB agar supplemented with trimethoprim and gentamicin (to remove E. coli helper and donor strains). The integration of the suicide plasmid was confirmed by PCR using primers 1300 and 1762 and by Southern blot hybridization using a sodC-specific probe, which allowed identification of the sodC-deficient strain KEK1.

Southern blot hybridization.

The 299-bp amplicon (sodC) probe was labeled directly with digoxigenin-11-UTP using primers 1702 and 1703 and a PCR labeling kit (Roche), as recommended by the manufacturer. B. cenocepacia genomic DNA was isolated and digested with NotI. Briefly, DNA was electrophoresed on a 0.7% agarose gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by capillary action. The membrane was incubated with the sodC probe under high-stringency conditions. Hybridization signals were detected by chemiluminescence with disodium 3-(4-methoxyspiro{1,2-dioxetane-3,2′-(5′-chloro)tricylco[3.3.1.13,7]decan}-4-yl)phenyl phosphate (CSPD) as recommended by the manufacturer (Roche).

Complementation of the sodC mutant.

A PCR fragment carrying the complete coding sequence of the sodC gene was amplified from B. cenocepacia K56-2 chromosomal DNA using forward primer 2375 and reverse primer 2376 containing EcoRI and XbaI restriction sites, respectively. The sodC PCR product was digested with EcoRI and XbaI and ligated into EcoRI- and XbaI-digested pDA17 under control of the dhfr promoter before transformation into E. coli DH5α. The resulting plasmid, pKK21, encoded a SodC protein with a C-terminal FLAG epitope (SodCFLAG). This was verified by DNA sequencing at the York University Core Molecular Biology and DNA Sequencing Facility, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Colony PCR using primers 1631 and 2375, followed by restriction digestion and DNA sequencing, confirmed that the insert was present and that there were no mutations in the PCR-amplified sodC sequence compared to the published sequence of strain J2315 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/B_cenocepacia/).

Site-directed mutagenesis of B. cenocepacia K56-2 SodCFLAG fusion.

pKK21 and pUC18 were digested with XbaI and EcoRI. The sodC insert liberated from pKK21 was gel extracted using a QIAGEN gel extraction kit and ligated into the cut, purified pUC18. The ligation mixture was transformed in E. coli DH5α competent cells. Transformants were screened by colony PCR using primers 2375 and 2376 and by restriction digestion using XbaI and EcoRI, which resulted in a 540-bp product. Plasmid DNA was prepared from the positive clone pKK39 and used as the template DNA in a QuikChange (Stratagene) PCR mutagenesis reaction with primers 2602 and 2603. The mutation of cysteine at position 29 to glycine in pKK42 was confirmed by DNA sequencing using the M13 reverse sequencing primer. pKK42 was digested with XbaI and EcoRI, and the liberated insert was gel extracted and then ligated into XbaI- and EcoRI-cut pDA17. Positive clones were screened by colony PCR and restriction digestion as described above. Plasmid pKK44, which contained the C29G sodC gene, was transferred to B. cenocepacia KEK1 by triparental mating (13).

Localization of the SodCFLAG fusion protein in B. cenocepacia K56-2.

The subcellular localization of the SodCFLAG fusion protein in B. cenocepacia K56-2 was confirmed by Western blotting of culture supernatants and cell fractions, including periplasmic, inner membrane, outer membrane, and cytoplasmic extracts. Briefly, strains expressing SodCFLAG or the pDA17 control were grown overnight at 37°C and then subcultured in 250 ml of LB medium containing the appropriate antibiotics and allowed to grow with aeration for 6 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 11 ml of 25% (wt/vol) sucrose in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) containing the Complete broad-spectrum protease inhibitors (Roche). Cells were then lysed by three passages through a French pressure cell at 10,000 lb/in2. Debris and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 27,200 × g for 15 min, and the clear supernatants were layered on a 60% (wt/wt) sucrose cushion (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4), which was followed by centrifugation at 270,000 × g for 2 h. Cell membranes were collected from the interface of the sucrose cushion, and the protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay using the Bio-Rad protein reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA). All samples were adjusted using 25% (wt/vol) sucrose in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) so that the final protein concentrations were the same. The refractive index of each sample was determined using an Atago R-5000 hand refractometer and was compared to a sucrose standard curve, and the final concentration of sucrose in each sample was adjusted to 60% (wt/wt). Six hundred microliters of each sample was then pipetted into the bottom of a 13.2-ml plastic ultracentrifuge tube, and a sucrose flotation gradient (1.16 ml each of 56, 53, 50, 47, 44, 41, 38, 35, and 32% sucrose) was layered on top of the sample. The samples were centrifuged at 270,000 × g for 48 h at 10°C with the brake off. Fractions (500 μl) were collected and assayed to determine both the protein concentration and the NADH oxidase activity. Briefly, 0.12 mM NADH and 0.2 mM dithiothreitol in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4) were added to each fraction, and the change in absorbance at 340 nm was determined. Twenty micrograms of protein from each subcellular fraction was mixed with 4× protein loading dye and loaded onto a 14% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gel. The proteins were electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane using standard methods. A Western blot analysis was performed using an anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal primary antibody and Alexa Fluor 680 goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) secondary antibody. Images were acquired using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Native gel electrophoresis and SOD activity staining.

Native PAGE was utilized to identify bands of SOD activity, as previously described (3). Ten to 20 μg of protein was loaded into each lane, and electrophoresis was performed using 10% Novex gels at 15 mA for 1.5 h. After electrophoresis the gels were washed twice for 15 min in distilled water and incubated with shaking in the dark for 30 min with a 250 μM nitroblue tetrazolium solution. The gels were washed briefly with distilled H2O and then incubated in a developing solution containing 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.8), 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 20 mM N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethyldiamine, and 30 μM riboflavin in the dark with shaking for 20 min. Bands of SOD activity were visualized by exposing the gels to light for 10 min or until sufficient contrast with the background was obtained. Bands of SOD activity appeared as clear zones on a purple background. FeSOD and MnSOD purified from E. coli and CuZnSOD from bovine erythrocytes were used as positive controls in this assay. Incubation with 0 to 50 mM H2O2 and incubation with 0 to 50 mM KCN for 30 min inhibited FeSOD and Cu,ZnSOD activities, respectively, which allowed us to determine the metal cofactor associated with B. cenocepacia SodC.

In vitro sensitivity to extracellular superoxide.

Assays were performed using a xanthine/xanthine oxidase system to generate extracellular superoxide. Late-stationary-phase culture samples containing 1 × 108 cells ml−1 were incubated with shaking at 37°C in a mixture containing 250 μM xanthine and 0.14 U of xanthine oxidase. Catalase (100 U ml−1) was added to each sample prior to addition of xanthine oxidase to protect cells from the toxicity of any H2O2 produced as a result of the SOD activity. Aliquots were removed at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min and serially diluted in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4). The time-zero aliquots were removed before the addition of xanthine oxidase. Appropriate dilutions were plated in triplicate on LB agar plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. The percentage of survival was calculated as described previously (34).

Disk diffusion assays.

Logarithmic-phase cells were spread on agar plates with a sterile cotton swab, and 6-mm sterile paper disks were applied to the surfaces. Then 8-μl portions of 0 to 100 mM H2O2 or 0 to 10 mM methyl viologen (paraquat) were applied to triplicate disks. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and the zones of inhibition were measured.

Sensitivity to 3-morpholinosydnonimine.

Cells were grown to the logarithmic phase and then diluted to obtain a concentration of 10−5 cells ml−1. Cells were then incubated with rapid shaking at room temperature in the presence of 0.8 mM 3-morpholinosydnonimine or double-distilled H2O as a control. Samples were removed at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min, and serial dilutions were plated on LB agar plates. CFU were counted after incubation overnight at 37°C.

Macrophage infections.

Cell culture reagents were purchased from Wisent Inc., St. Bruno, Quebec, Canada, unless indicated otherwise. Macrophages were trypsinized and seeded into six-well tissue culture plates containing glass coverslips. The cells were incubated overnight at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Plasmid pRedCm (Ron Flanagan) was introduced into wild-type strain K56-2 and SodC mutant strain KEK1 by triparental mating. All strains harboring this plasmid constitutively express monomeric red fluorescent protein. The bacteria were grown overnight and then washed twice with DMEM, and RAW 264.7 macrophage-like cells were then infected with either K56-2(pRedCm) or KEK1(pRedCm) at a multiplicity of infection of 30. Infections were equalized by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 1 min and were allowed to proceed for 4 h. After this the external bacteria were removed by three washes with RPMI prewarmed to 37°C. In some experiments, 10 μM diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) was added at the same time that bacteria were added to the macrophages. Fluorescence and phase-contrast images of the infected macrophage monolayers were then acquired using a Qimaging (Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada) cooled charged-coupled device camera mounted on an Axioscope 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with a ×100/1.3 numerical aperture, a Plan-Neofluor objective, and a 50-W mercury arc lamp. Red filter set 15 (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with an SP 546-nm excitation and LP 590-nm emission was used. Images were digitally processed using the Northern Eclipse version 6.0 imaging analysis software (Empix Imaging, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada).

Cloning B. cenocepacia sodC into pET28a.

The B. cenocepacia K56-2 sodC gene was amplified by PCR using primers 2199 and 2200 with NcoI and NotI restriction sites, ligated into NcoI- and NotI-digested pET28a, and transformed into E. coli DH5α cells, resulting in pKK1. Kanamycin-resistant colonies were screened by restriction digestion and PCR to confirm the presence of sodC. pKK1 was confirmed by DNA sequencing using T7 promoter and terminator primers specific for the pET vectors.

Overexpression and purification of B. cenocepacia sodC in E. coli BL21(DE3).

pKK1 was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3). A single colony was then used to inoculate 5 ml of LB medium containing kanamycin, and the culture was grown overnight with shaking at 37°C. Then 250 ml of LB medium containing kanamycin was inoculated (1:100) with the overnight culture and incubated until the optical density at 600 nm was 0.6 to 0.8. The cells were induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at a final concentration of 0.1 mM and allowed to grow for an additional 6 h before they were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in 1.5% of the original culture volume of cell lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole; pH 8.0). Then 0.75 mg/ml lysozyme was added, and the suspension was incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were lysed by three passages through a French pressure cell at 10,000 lb/in2. Soluble proteins were then harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter. Soluble proteins were applied to a chelating Sepharose column (bed volume, 3 ml) which had been preloaded with cobalt ions and equilibrated with cell lysis buffer as recommended by the manufacturer. The column was washed with 5 column volumes of wash buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole; pH 8.0). Proteins were then eluted in 2 column volumes of elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole; pH 8.0). Eluted fractions containing recombinant B. cenocepacia SodC were identified by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. These fractions were concentrated using a Vivaspin centrifugal concentrator, and the protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein concentration reagent. Purified SodC was then electrophoresed on a native gel and stained to reveal SOD activity.

Production and reconstitution of apo-SodC.

Metal-ion-free water was prepared by adding 5 g of Chelex resin (Bio-Rad) per 100 ml of water and shaking the solution vigorously for 1 h, and the resin was then removed by filtration. All reagents used for preparation of apo-SodC were made using Chelex-treated water. Five hundred microliters of a 5-mg ml−1 solution of purified recombinant SodC was dialyzed against 100 volumes of 30 mM EDTA-20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) using a Pierce Slide-A-Lyser with a 5-kDa cutoff. The buffer was changed twice after 2 h of incubation at 4°C, and this was followed by a final dialysis at 4°C overnight. SodC was then dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) for 2 h to remove excess EDTA. A twofold molar excess of FeCl3, MnCl2, or ZnSO4/CuSO4 was added to 20-μl samples of the apo-SodC and incubated for 20 min at 4°C. Each sample was then dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) to remove the excess metal ions.

RESULTS

Identification of SOD genes in the B. cenocepacia J2315 genome.

Examination of the B. cenocepacia strain J2315 genome revealed the presence of two putative SOD genes. One of these genes, BCAL2757 located on chromosome 1, exhibited 98% identity to sodB in Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei. BCAL2757 appears to be the second gene in a four-gene operon, and the upstream gene BCAL2758 codes for a putative DNase VII large subunit. The BCAL2756 and BCAL2757 downstream genes encode putative transposases. The second putative SOD gene, BCAL2643, which is also located on chromosome 1, exhibited homology to sodC genes of other gram-negative bacteria encoding a Cu,ZnSOD. Analysis of the region surrounding sodC suggests that it is the second gene in a putative five-gene operon. Upstream of the putative sodC gene is BCAL2644, which encodes a putative ATP-binding protein. Downstream of sodC are BCAL2642, BCAL2641, and BCAL2640, which encode a dCTP deaminase, a putative ornithine decarboxylase, and a putative exported protein, respectively. The 179-amino-acid polypeptide encoded by the B. cenocepacia sodC gene is characterized by a hydrophobic N-terminal sequence, which is typical of a signal sequence for protein export. Further analysis of the N-terminal region of the SodC protein also revealed the presence of a putative prokaryotic membrane lipoprotein attachment site. This SodC lipoprotein attachment site was previously described for SodC from the gram-positive bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis (15). The predicted 28-amino-acid signal sequence of B. cenocepacia SodC contains the motif Leu-Xaa-Yaa-Cys present in all bacterial lipoproteins, where Xaa and Yaa are the small neutral amino acids alanine and glycine, respectively. The cysteine residue is the putative first residue of the mature lipoprotein and the site where an acylglycerol fatty acid should be attached (50). The bioinformatic prediction for the actual subcellular location of SodC is unclear, as SodC is predicted to be either membrane associated or periplasmic (see below).

The sodC mutant of B. cenocepacia has reduced growth rate.

To evaluate whether a Cu,ZnSOD plays a role in the protection of B. cenocepacia from the toxic effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and from killing in cell culture model systems, a B. cenocepacia mutant with a defective sodC gene was constructed and designated KEK1. KEK1 is an isogenic derivative of K56-2 in which sodC is insertionally inactivated by integration of the suicide plasmid pGPΩTp. The presence of the integrated plasmid was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot hybridization (data not shown). B. cenocepacia strains K56-2 and J2315 are clonally related, as previously demonstrated by macrorestriction and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analyses (40), and the gene organizations of the sodC region in strains K56-2 and J2315 are identical, as determined by PCR analysis (data not shown).

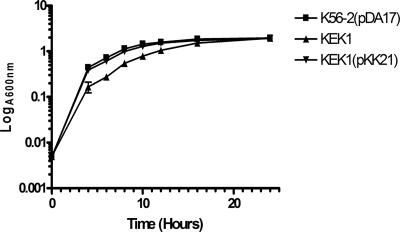

Toxic ROS are routinely generated in cells during aerobic respiration (26). To examine whether SodC is required for the growth of B. cenocepacia in LB medium, we compared the growth rates of KEK1 and parental strain K56-2 containing the plasmid pDA17. This plasmid was used to compare the growth rates of mutant and parental strains in the presence of trimethoprim. Compared to the growth of parental strain K56-2(pDA17), the growth of KEK1 was significantly different at 37°C, as demonstrated by a doubling time for KEK1 of approximately 3.6 h. In contrast, the doubling time of K56-2(pDA17) was 1.9 h. By 24 h, the amount of growth of KEK1 was the same as the amount of growth of K56-2(pDA17). The difference in the growth rates was attributed to the sodC insertional mutation, as this mutation could be complemented by supplying a copy of sodC in trans on plasmid pKK21 in strain KEK1 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Growth defect of the sodC mutant (KEK1) in LB medium can be complemented by transformation with pKK21 containing an intact sodC gene. The symbols and error bars indicate the averages and standard deviations of three replicates. K56-2 was the parental strain, KEK1 was the sodC null strain, and KEK1 was complemented with plasmid pKK21.

B. cenocepacia SodC is a periplasmic protein.

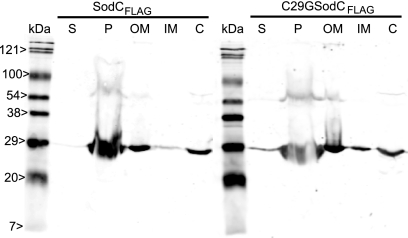

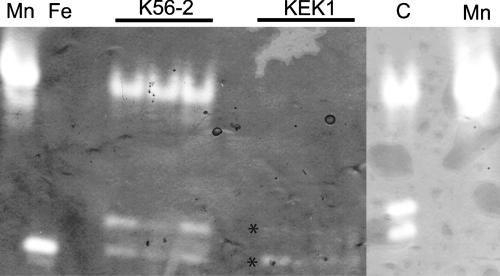

Analysis of the amino acid sequence of B. cenocepacia SodC predicted that this protein was either a secreted membrane-anchored lipoprotein or a periplasmic protein. To distinguish between these possibilities, we constructed a C29G replacement derivative of SodC (encoded by plasmid pKK44). This mutation disrupted the putative lipoprotein signal sequence. Subcellular fractions were prepared for B. cenocepacia K56-2(pDA17), B. cenocepacia KEK1(pKK21), and B. cenocepacia KEK1(pKK44), and the protein concentrations of these fractions were determined. Equivalent amounts of total protein were loaded on a 14% SDS-PAGE gel and then electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Proteins were detected by Western blotting using an anti-FLAG antibody. No FLAG-tagged proteins were detected in extracellular, periplasmic, or membrane extracts of the control strain, B. cenocepacia K56-2(pDA17) (data not shown). SodCFLAG has a predicted molecular mass of 23 kDa, while the bands identified by Western blotting were located at 27 and 54 kDa. The higher-molecular-weight band was consistent with formation of a SodCFLAG dimer. In both KEK1(pKK21) and KEK1(pKK44) SodCFLAG was detected as two bands in both the periplasmic and outer membrane fractions and as a single band in the inner membrane and cytosolic fractions (Fig. 2). However, approximately 75% of SodCFLAG was present in the periplasmic fraction of both KEK1(pKK21) and KEK1(pKK44), confirming that SodCFLAG is a periplasmic protein and that the C29G mutation had no effect on the subcellular location of SodCFLAG. Native gel analysis of periplasmic extracts from K56-2 showed that there were three bands of SOD activity, a major slowly migrating band and a faster-migrating minor doublet. Comparison with periplasmic extracts of KEK1 showed that the major slowly migrating band of SOD activity was absent and that the amounts of the minor doublet were smaller. Analysis of periplasmic extracts of the complemented strain, KEK1(pKK21), demonstrated that the slowly migrating major band of SOD activity was present and that the amount of the doublet was increased (Fig. 3). The fast-migrating doublet that was observed in all extracts, including the KEK1 extract, is consistent with the banding pattern of crude cell extracts. The amount of the fast-migrating species varied depending on the level of cell lysis that occurred during preparation of the periplasm sample. Together, these results indicate that B. cenocepacia SodC is truly a periplasmic protein and is not a periplasmic lipoprotein anchored to the plasma membrane, as suggested by the presence of the LXXC lipoprotein signal peptide motif.

FIG. 2.

Detection of SodC in periplasmic extracts of KEK1(pKK21) and KEK1(pKK44). Identical amounts (15 μg) of samples from the culture supernatant (S), periplasm (P), outer membrane (OM), inner membrane (IM), and cytosolic (C) fractions were loaded. Samples were prepared from KEK1(pKK21) and KEK1(pKK44), separated by SDS-PAGE, and electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Western blotting was performed using an anti-FLAG antibody.

FIG. 3.

Mutation of SodC results in loss of the major band of SOD activity in periplasmic extracts and can be complemented by pKK21. Equal amounts (20 μg) of protein were loaded for all samples. The controls were E. coli MnSOD (lane Mn) and E. coli FeSOD (lane Fe). Three independent samples of K56-2 and KEK1 were examined to determine their SodC activities. Lane C contained the sample from KEK1(pKK21). All extracts were separated by native PAGE and then stained to reveal the SOD activity. The asterisks indicate the locations of the fast-migrating doublet of SOD activity in KEK1 samples.

B. cenocepacia sodC mutant is sensitive to exogenous superoxide.

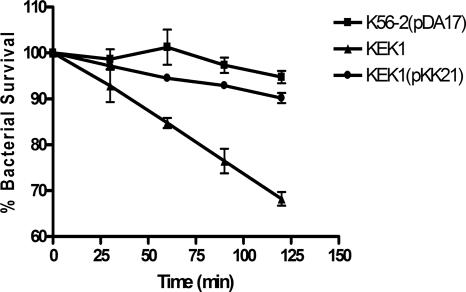

Based on the proposed function and periplasmic location of SodC, we predicted that KEK1 would be sensitive to exogenous superoxide. The sensitivities of KEK1, KEK1(pKK21), and K56-2(pDA17) to intracellular superoxide and to extracellular superoxide were determined using paraquat and xanthine/xanthine oxidase, respectively. Xanthine oxidase converts xanthine to urate, and O2− is generated as a by-product of this reaction (20). Xanthine oxidase cannot cross the bacterial membrane, and consequently, the xanthine oxidase reaction has been used to generate extracellular O2− in a number of eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. After 120 min of exposure to xanthine/xanthine oxidase-generated O2−, there was an approximately 30% reduction in the survival of KEK1, in contrast to 6 and 10% reductions in the survival of the parental strain and the complemented sodC mutant KEK1(pKK21), respectively (Fig. 4). No killing was observed when K56-2 and KEK1 were exposed to either 0.8 mM 3-morpholinosydnonimine or 10 mM paraquat. Together, these results confirm that SodC protects against exogenously generated O2− but cannot protect against O2− in the cytoplasm.

FIG. 4.

KEK1 is susceptible to killing by extracellular O2−: resistance of B. cenocepacia K56-2(pDA17), KEK1, and KEK1(pKK21) to killing by O2− generated by the xanthine/xanthine oxidase reaction. The error bars indicate standard deviations for the percentage of surviving bacteria obtained from triplicate plates at each time.

SodC contributes to the survival of B. cenocepacia in macrophages.

We have previously demonstrated that in contrast to classical intracellular pathogens, Bcc strains survive intracellularly without replication in amoeba (42) and murine macrophages (46). The production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species by macrophages is a major component of the host's antimicrobial defenses. A major difficulty with cell infection assays using B. cenocepacia isolates is the inability to effectively kill extracellular bacteria with antibiotics. B. cenocepacia is extraordinarily resistant to antimicrobials that are commonly employed to kill extracellular bacteria in classical invasion assays (30, 41, 46). Previous studies in our laboratory demonstrated that live Burkholderia cells expressing either enhanced green fluorescent protein or monomeric red fluorescent protein 1 (mRFP1) retain fluorescence in the bacterial cytoplasm, whereas heat-killed bacteria, which retain fluorescence if they are kept in buffer, leak fluorescence into the vacuolar space once they are phagocytosed (30, 31, 41). Thus, dispersal of the fluorescent protein throughout the phagosomal lumen can be used as an indication of disruption of the bacterial cell envelope. To determine whether SodC plays a role in the intracellular survival of B. cenocepacia after phagocytosis, microscopic single-cell analyses were performed to assess the intactness of mutant strain KEK1 containing plasmid pRedCm, which expresses mRFP1. A quantitative analysis was performed by counting on average 15 to 20 macrophage cells per field of view in a blinded fashion, and a total of 21 fields of view were observed for each replicate. The total number of B. cepacia-containing vacuoles was determined, and the percentage of the cells in which mRFP1 had diffused throughout the phagosomal lumen was calculated. At 4 h postinfection, 51.3% ± 2.5% (P = <0.001) of the vacuoles with KEK1(pRedCm) bacteria had fluorescence in the lumen, whereas 21.3% ± 1.6% of the lumina of phagosomes containing parental strain K56-2 (pRedCm) were fluorescently labeled. DPI, an inhibitor of flavoproteins, including NADPH oxidase, was added at the same time as KEK1, and the assay was repeated. At 4 h postinfection, 33.5% ± 2.3% of the lumina of phagosomes containing KEK1 in DPI-treated cells were fluorescently labeled (P = <0.0017). This experiment suggested that inhibition of the oxidative burst by DPI reduces the loss of envelope integrity of the intracellular sodC-defective mutants. Collectively, our results indicate that SodC is required for intracellular survival of B. cenocepacia and plays a role in the protection against bacterial damage from ROS that are generated in the phagosome.

B. cenocepacia SodC is a Cu,ZnSOD with unusual resistance to inhibition by KCN.

SODs can contain Fe3+, Mn2+, or Cu2+/Zn2+ cofactors. To determine the B. cenocepacia K56-2 SodC metal cofactor, studies were performed using a variety of inhibitors with known effects on SODs containing various metal cofactors. The Cu,ZnSODs are inhibited by 2 to 5 mM KCN, while the manganese and iron forms are not inhibited under these conditions (24). Iron-containing SODs are generally completely inactivated by incubation with 5 mM H2O2, which has been demonstrated for FeSODs from Alcaligenes faecalis and Bacillus fragilis (25, 44), while MnSODs are resistant to inhibition. Periplasmic protein extracts from B. cenocepacia K56-2 were incubated with concentrations of KCN ranging from 0 to 50 mM, and there were no detectable differences in SOD activity, as judged by native PAGE, suggesting that SodC does not contain Cu,Zn cofactors (Fig. 5B). As a control, Cu,ZnSOD from bovine erythrocytes was incubated with different concentrations (0 to 50 mM) of KCN (Fig. 5C), and the activity was eliminated at a KCN concentration of 5 mM. Incubation with concentrations of H2O2 ranging from 0 to 50 mM also resulted in no detectable differences, suggesting that SodC does not contain an iron cofactor (Fig. 5A). This indirect evidence suggests that SodC could in fact be either unusually resistant to inhibition by KCN or contain a manganese cofactor.

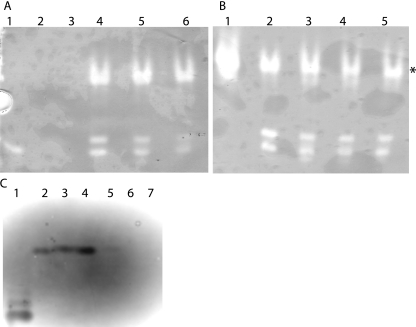

FIG. 5.

SodC from B. cenocepacia is resistant to inhibition by H2O2 and KCN. Identical amounts (20 μg) of K56-2 periplasmic protein extracts were separated by native PAGE and then stained to reveal SOD activity. Samples were pretreated with different concentrations of H2O2 (A) and KCN (B) for 30 min at room temperature to inactivate FeSOD activity and Cu,ZnSOD activity, respectively. (A) Lane 1, E. coli FeSOD-positive control; lane 2, E. coli FeSOD plus 25 mM H2O2; lane 3, E. coli FeSOD plus 50 mM H2O2; lane 4, K56-2 protein extract; lane 5, K56-2 protein extract plus 25 mM H2O2; lane 6, K56-2 protein extract plus 50 mM H2O2. (B) Lane 1, E. coli MnSOD-positive control; lane 2, K56-2 protein extract; lane 3, K56-2 protein extract plus 5 mM KCN; lane 4, K56-2 protein extract plus 25 mM KCN; lane 5, K56-2 protein extract plus 50 mM KCN. (C) Lane 1, E. coli FeSOD-positive control; lane 2, K56-2 protein extract; lane 3, K56-2 protein extract plus 50 mM KCN; lane 4, bovine erythrocyte Cu,ZnSOD; lane 5, bovine erythrocyte Cu,ZnSOD plus 5 mM KCN; lane 6, bovine erythrocyte Cu,ZnSOD plus 25 mM KCN; lane 7, bovine erythrocyte Cu,ZnSOD plus 50 mM KCN. The color is inverted in panel C to aid visualization of the bands of activity.

To distinguish between these possibilities, purified B. cenocepacia SodC was produced by cloning sodC into pET28a, creating plasmid pKK1, which expresses SodC with a C-terminal six-histidine tag. This plasmid was introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3), and SodC production was induced by addition of IPTG. IPTG concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0 mM were tested to optimize the levels of SodC expression in the soluble fraction. The greatest yields of soluble SodC were observed when the cells were induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. The effect of temperature on expression was also determined. Incubation at 22, 30, and 37°C resulted in no differences in the yields of soluble SodC (data not shown). SodC was purified using a chelating Sepharose column charged with cobalt ions. Purification was also assessed using a nickel-charged column; however, the level of purity obtained with the cobalt column was much greater and was used for further studies. Elution fractions were pooled and concentrated to obtain a final concentration of 5 mg/ml, and then the purity was checked by SDS-PAGE and the activity was checked by native PAGE (data not shown).

Purified recombinant SodC was dialyzed against 30 mM EDTA to strip the metal ion cofactor, producing an apo form of the enzyme that had no associated SOD activity (Fig. 6, lane 2). After excess EDTA was removed by dialysis, a molar excess of iron, manganese, or copper/zinc was added to the apo enzyme, and the SOD activities of the reconstituted enzymes were assessed by native PAGE. Addition of either iron or manganese did not restore SOD activity (Fig. 6, lane 5, and data not shown), but SOD activity was restored to apo-SodC by addition of both copper and zinc (Fig. 6, lane 4). These results demonstrate that B. cenocepacia SodC does in fact contain copper and zinc cofactors and does not contain a manganese cofactor as suggested by the KCN inhibition studies.

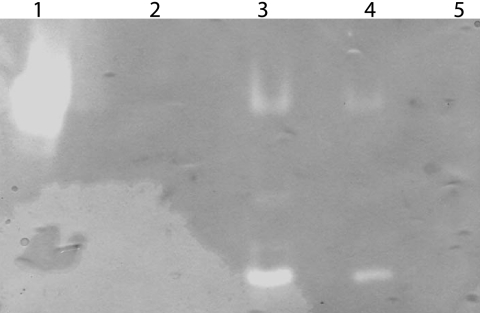

FIG. 6.

Determination of SodC metal cofactor. Recombinant B. cenocepacia SodC was purified from E. coli BL21(DE3), and then all metal ions were stripped from the molecule before reconstitution with either Mn2+ or Cu,Zn2+. Identical amounts of protein were loaded on native PAGE gels and stained to reveal SOD activity. Lane 1, E. coli MnSOD-positive control; lane 2, B. cenocepacia apo-SodC; lane 3, purified B. cenocepacia SodC; lane 4, apo-SodC preincubated with Cu and Zn2+; lane 5, apo-SodC preincubated with Mn2+.

DISCUSSION

B. cenocepacia tolerates the highly oxidative environment in the cystic fibrosis lung, where the inflammatory response is dominated by neutrophils (29). Also, Bcc strains isolated from cystic fibrosis patients, especially B. cenocepacia strains, have high levels of SOD activity (34). In this work, we identified and functionally characterized the B. cenocepacia sodC (BCAL2643) gene encoding a Cu,ZnSOD. A previous study in our laboratory (34) provided preliminary information about the role of SODs in the resistance of Burkholderia spp. to ROS in vitro. An FeSOD was detected in crude cell lysates, but a Cu,ZnSOD was not identified. Due to the subcellular location of Cu,ZnSOD, crude cell lysates would not be predicted to contain this periplasmic SOD, suggesting that the FeSOD described previously (34) corresponds to the protein encoded by BCAL2757 (sodB).

Cu,ZnSODs have been found in a wide range of bacteria, including Haemophilus (47), Neisseria (56), Escherichia (23), Legionella (53), Salmonella (6), and Mycobacterium (45) species. In some pathogenic bacteria, such as Salmonella and Neisseria species, it has been demonstrated that sodC was horizontally acquired, which often resulted in the presence of more than one copy of the gene. The following three SodC proteins have been found in Salmonella: SodC2, which exhibits significant sequence similarity to SodC from Brucella abortus (6), and SodC1 and SodC3, which were acquired on the lysogenic bacteriophages Gifsy-2 and Fels-1, respectively (17, 18). In many other pathogens, including B. cenocepacia, there are no anomalies in the bacterial sequence surrounding the sodC gene, implying that sodC was not horizontally acquired in these organisms. Previous studies have shown that the majority of Cu,ZnSOD proteins are not required for bacterial growth under laboratory conditions, as they do not play an apparent role in the detoxification of the superoxide anion intracellularly (17, 48). However, when KEK1 is grown in LB medium, its growth is retarded compared to the growth of parental strain K56-2. A similar phenotype was reported for a strain of Aeromonas hydrophila deficient in a periplasmic MnSOD (33).

B. cenocepacia SodC has a putative signal peptidase II cleavage site allowing cleavage of the 28-amino-acid signal sequence and attachment of SodC via the first cysteine residue to an acylglycerol fatty acid, thus anchoring SodC to the membrane. The vast majority of SodC proteins from gram-negative bacteria contain a predicted classical signal peptidase I cleavage site, indicating that the mature protein is soluble in the periplasm (15). Western blotting of culture supernatants, periplasmic extracts, inner and outer membrane extracts, and cytosolic proteins from both B. cenocepacia expressing SodC from plasmid pKK21 and B. cenocepacia expressing SodC from pKK44 clearly demonstrated that SodC was periplasmic and present in both a monomeric form and a dimeric form. The C29 mutation in the L-X-X-C signal peptidase II motif had no effect on the subcellular location of SodC expressed from pKK44, indicating that SodC is periplasmic.

The finding that B. cenocepacia SodC was active in the periplasm was consistent with the results of the functional analysis of resistance to killing by oxidative damage. KEK1 was susceptible to superoxide generated in the extracellular milieu by the xanthine/xanthine oxidase reaction, but it was resistant to inhibition by paraquat, which generates intracellular superoxide. This survival defect of KEK1 in the presence of extracellular superoxide is less than the survival defect observed for other sodC mutants. During the xanthine/xanthine oxidase experiment in this study, catalase was added to the media to convert any H2O2 that was generated as a by-product of the reaction into H2O and O2. The presence of exogenous H2O2 generated during the reaction could cause the formation of other, more potent ROS and reactive nitrogen species that could potentially cause growth reductions that are not specifically caused by extracellular superoxide. Thus, a direct comparison of these results with some of the previously described results is not possible as catalase was not included in the reaction mixture.

Inhibition studies performed with K56-2 confirmed that B. cenocepacia SodC did not contain an iron cofactor, as SOD activity was observed at H2O2 concentrations of 50 mM and the control E. coli FeSOD activity was completely eliminated by preincubation with 25 mM H2O2. Cu,ZnSODs are normally inhibited by KCN at concentrations of 2 to 5 mM. The control bovine erythrocyte Cu,ZnSOD was inhibited by preincubation with 5 mM KCN. B. cenocepacia SodC was not inhibited by preincubation with up to 50 mM KCN. Currently, no specific inhibitor for MnSODs is known. To accurately determine the metal cofactor associated with B. cenocepacia SodC, we took a biochemical approach. Recombinant B. cenocepacia SodC was overproduced and purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) for metal cofactor studies. Apo-SodC was produced by dialysis against EDTA as previously described (50). Addition of either Fe3+ or Mn2+ to recombinant apo-SodC had no effect on SOD activity, and the enzyme remained inactive. Upon addition of Cu,Zn2+, SOD activity was observed, thus conclusively proving that B. cenocepacia SodC is a Cu,ZnSOD that is unusually resistant to KCN inhibition.

The relationship between Cu,ZnSOD and virulence is unclear. In some pathogenic bacteria, sodC null mutants exhibit attenuated virulence in animal models (2). However, a sodC mutant of the swine pathogen Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae was not attenuated in an intratracheal model of infection (49), and conflicting results were reported concerning attenuation of a sodC mutant of B. abortus (22, 32). This suggests that that role of CuZnSODs during infection depends on a variety of factors, including the host, the route of infection, the site of infection, and the infecting organism. We used our macrophage infection model to probe the function of sodC in B. cenocepacia. Cell infection assays with B. cenocepacia isolates cannot be performed using standard methods as it is difficult to effectively kill the extracellular bacteria (41, 42, 46). Therefore, we performed a single-cell microscopic analysis to examine the release of bacterially encoded mRFP1 into the lumen of the phagocytic vesicles as an indication of disruption of the bacterial cell envelope. Our results show that intracellular sodC null bacteria have indications of compromised cell envelope integrity, as shown by a higher frequency of release of cytosolic mRFP1 into the lumina of the bacterium-containing vacuoles. Addition of DPI, a known inhibitor of flavoproteins, including NADPH oxidase (36), resulted in a significant reduction in the leakage of mRFP1 by intracellular bacteria to levels comparable to those of the parental strain. These results suggest that the defect in SodC activity can be corrected by blocking the oxidative response in macrophages, thus suggesting that SodC neutralizes ROS in the phagocytic vacuole. Our results agree with previous observations made with Salmonella enterica serovar Choleraesuis (1, 48), B. abortus (22), and M. tuberculosis (45), which showed that the ability of all sodC null mutants to survive in macrophages was impaired.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that SodC is a periplasmic antioxidant protein containing Cu,Zn2+ cofactors that has unusual resistance to KCN inhibition. SodC protects B. cenocepacia K56-2 from exogenously generated O2− in vitro and contributes to resistance to killing by oxidative products produced by macrophages.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ron Flannagan, Daniel Aubert, and all members of the Valvano lab for providing plasmids and for useful discussions, Roger Y. Tsien for providing mRFP1, and Julian Parkhill for providing access to the draft annotation of B. cenocepacia J2315.

This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. K.E.K. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. M.A.V. holds a Canada Research Chair in Infectious Diseases and Microbial Pathogenesis.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ammendola, S., M. Ajello, P. Pasquali, J. S. Kroll, P. R. Langford, G. Rotilio, P. Valenti, and A. Battistoni. 2005. Differential contribution of sodC1 and sodC2 to intracellular survival and pathogenicity of Salmonella enterica serovar Choleraesuis. Microbes Infect. 7:698-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battistoni, A. 2003. Role of prokaryotic Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase in pathogenesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:1326-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beauchamp, C., and I. Fridovich. 1971. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 44:276-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brockbank, S., D. Downey, J. S. Elborn, and M. Ennis. 2005. Effect of cystic fibrosis exacerbations on neutrophil function. Int. Immunopharmacol. 5:601-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns, J. L., M. Jonas, E. Y. Chi, D. K. Clark, A. Berger, and A. Griffith. 1996. Invasion of respiratory epithelial cells by Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia. Infect. Immun. 64:4054-4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canvin, J., P. R. Langford, K. E. Wilks, and J. S. Kroll. 1996. Identification of sodC encoding periplasmic [Cu,Zn]-superoxide dismutase in Salmonella. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 136:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlioz, A., and D. Touati. 1986. Isolation of superoxide dismutase mutants in Escherichia coli: is superoxide dismutase necessary for aerobic life? EMBO J. 5:623-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chenna, R., H. Sugawara, T. Koike, R. Lopez, T. J. Gibson, D. G. Higgins, and J. D. Thompson. 2003. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3497-3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chmiel, J. F., M. Berger, and M. W. Konstan. 2002. The role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of CF lung disease. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 23:5-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conese, M., E. Copreni, S. Di Gioia, P. De Rinaldis, and R. Fumarulo. 2003. Neutrophil recruitment and airway epithelial cell involvement in chronic cystic fibrosis lung disease. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corey, M., and V. Farewell. 1996. Determinants of mortality from cystic fibrosis in Canada, 1970-1989. Am. J. Epidemiol. 143:1007-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courtney, J. M., K. E. Dunbar, A. McDowell, J. E. Moore, T. J. Warke, M. Stevenson, and J. S. Elborn. 2004. Clinical outcome of Burkholderia cepacia complex infection in cystic fibrosis adults. J. Cyst. Fibros. 3:93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craig, F. F., J. G. Coote, R. Parton, J. H. Freer, and N. J. Gilmour. 1989. A plasmid which can be transferred between Escherichia coli and Pasteurella haemolytica by electroporation and conjugation. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135:2885-2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Groote, M. A., U. A. Ochsner, M. U. Shiloh, C. Nathan, J. M. McCord, M. C. Dinauer, S. J. Libby, A. Vazquez-Torres, Y. Xu, and F. C. Fang. 1997. Periplasmic superoxide dismutase protects Salmonella from products of phagocyte NADPH-oxidase and nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13997-14001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Orazio, M., S. Folcarelli, F. Mariani, V. Colizzi, G. Rotilio, and A. Battistoni. 2001. Lipid modification of the Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem. J. 359:17-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang, F. C., M. A. DeGroote, J. H. Foster, A. J. Baumler, U. Ochsner, T. Testerman, S. Bearson, J. C. Giard, Y. Xu, G. Campbell, and T. Laessig. 1999. Virulent Salmonella typhimurium has two periplasmic Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7502-7507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrant, J. L., A. Sansone, J. R. Canvin, M. J. Pallen, P. R. Langford, T. S. Wallis, G. Dougan, and J. S. Kroll. 1997. Bacterial copper- and zinc-cofactored superoxide dismutase contributes to the pathogenesis of systemic salmonellosis. Mol. Microbiol. 25:785-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Figueroa-Bossi, N., S. Uzzau, D. Maloriol, and L. Bossi. 2001. Variable assortment of prophages provides a transferable repertoire of pathogenic determinants in Salmonella. Mol. Microbiol. 39:260-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fridovich, I. 1970. Quantitative aspects of the production of superoxide anion radical by milk xanthine oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 245:4053-4057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fridovich, I. 1995. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:97-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gee, J. M., M. W. Valderas, M. E. Kovach, V. K. Grippe, G. T. Robertson, W. L. Ng, J. M. Richardson, M. E. Winkler, and R. M. Roop II. 2005. The Brucella abortus Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase is required for optimal resistance to oxidative killing by murine macrophages and wild-type virulence in experimentally infected mice. Infect. Immun. 73:2873-2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gort, A. S., D. M. Ferber, and J. A. Imlay. 1999. The regulation and role of the periplasmic copper, zinc superoxide dismutase of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 32:179-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haffner, P. H., and J. E. Coleman. 1973. Cu(II)-carbon bonding in cyanide complexes of copper enzymes. 13C splitting of the Cu(II) electron spin resonance. J. Biol. Chem. 248:6626-6629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodgson, E. K., and I. Fridovich. 1975. The interaction of bovine erythrocyte superoxide dismutase with hydrogen peroxide: inactivation of the enzyme. Biochemistry 14:5294-5299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imlay, J. A., and S. Linn. 1988. DNA damage and oxygen radical toxicity. Science 240:1302-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isles, A., I. Maclusky, M. Corey, R. Gold, C. Prober, P. Fleming, and H. Levison. 1984. Pseudomonas cepacia infection in cystic fibrosis: an emerging problem. J. Pediatr. 104:206-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keig, P. M., E. Ingham, P. A. Vandamme, and K. G. Kerr. 2002. Differential invasion of respiratory epithelial cells by members of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 8:47-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konstan, M. W., K. A. Hilliard, T. M. Norvell, and M. Berger. 1994. Bronchoalveolar lavage findings in cystic fibrosis patients with stable, clinically mild lung disease suggest ongoing infection and inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 150:448-454. (Erratum, 151:260, 1995.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamothe, J., K. K. Huynh, S. Grinstein, and M. A. Valvano. 2007. Intracellular survival of Burkholderia cenocepacia in macrophages is associated with a delay in the maturation of bacteria-containing vacuoles. Cell. Microbiol. 9:40-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamothe, J., S. Thyssen, and M. A. Valvano. 2004. Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates survive intracellularly without replication within acidic vacuoles of Acanthamoeba polyphaga. Cell. Microbiol. 6:1127-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Latimer, E., J. Simmers, N. Sriranganathan, R. M. Roop, 2nd, G. G. Schurig, and S. M. Boyle. 1992. Brucella abortus deficient in copper/zinc superoxide dismutase is virulent in BALB/c mice. Microb. Pathog. 12:105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leclere, V., M. Bechet, and R. Blondeau. 2004. Functional significance of a periplasmic Mn-superoxide dismutase from Aeromonas hydrophila. J. Appl. Microbiol. 96:828-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lefebre, M., and M. Valvano. 2001. In vitro resistance of Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates to reactive oxygen species in relation to catalase and superoxide dismutase production. Microbiology 147:97-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lefebre, M. D., R. S. Flannagan, and M. A. Valvano. 2005. A minor catalase/peroxidase from Burkholderia cenocepacia is required for normal aconitase activity. Microbiology 151:1975-1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, Y., and M. A. Trush. 1998. Diphenyleneiodonium, an NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor, also potently inhibits mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 253:295-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loprasert, S., W. Whangsuk, R. Sallabhan, and S. Mongkolsuk. 2004. DpsA protects the human pathogen Burkholderia pseudomallei against organic hydroperoxide. Arch. Microbiol. 182:96-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loprasert, S., W. Whangsuk, R. Sallabhan, and S. Mongkolsuk. 2003. Regulation of the katG-dpsA operon and the importance of KatG in survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei exposed to oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 542:17-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynch, R. E., and I. Fridovich. 1978. Effects of superoxide on the erythrocyte membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 253:1838-1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahenthiralingam, E., T. Coenye, J. W. Chung, D. P. Speert, J. R. Govan, P. Taylor, and P. Vandamme. 2000. Diagnostically and experimentally useful panel of strains from the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:910-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maloney, K. E., and M. A. Valvano. 2006. The mgtC gene of Burkholderia cenocepacia is required for growth under magnesium limitation conditions and intracellular survival in macrophages. Infect. Immun. 74:5477-5486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marolda, C. L., B. Hauröder, M. A. John, R. Michel, and M. A. Valvano. 1999. Intracellular survival and saprophytic growth of isolates from the Burkholderia cepacia complex in free-living amoebae. Microbiology 145:1509-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin, D. W., and C. D. Mohr. 2000. Invasion and intracellular survival of Burkholderia cepacia. Infect. Immun. 68:24-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayer, B. K., and J. O. Falkinham III. 1986. Superoxide dismutase activity of Mycobacterium avium, M. intracellulare, and M. scrofulaceum. Infect. Immun. 53:631-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piddington, D. L., F. C. Fang, T. Laessig, A. M. Cooper, I. M. Orme, and N. A. Buchmeier. 2001. Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis contributes to survival in activated macrophages that are generating an oxidative burst. Infect. Immun. 69:4980-4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saini, L., S. Galsworthy, M. John, and M. A. Valvano. 1999. Intracellular survival of Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates in the presence of macrophage cell activation. Microbiology 145:3465-3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.San Mateo, L. R., K. L. Toffer, P. E. Orndorff, and T. H. Kawula. 1999. Neutropenia restores virulence to an attenuated Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase-deficient Haemophilus ducreyi strain in the swine model of chancroid. Infect. Immun. 67:5345-5351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sansone, A., P. R. Watson, T. S. Wallis, P. R. Langford, and J. S. Kroll. 2002. The role of two periplasmic copper- and zinc-cofactored superoxide dismutases in the virulence of Salmonella choleraesuis. Microbiology 148:719-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheehan, B. J., P. R. Langford, A. N. Rycroft, and J. S. Kroll. 2000. [Cu,Zn]-superoxide dismutase mutants of the swine pathogen Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae are unattenuated in infections of the natural host. Infect. Immun. 68:4778-4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spagnolo, L., I. Toro, M. D'Orazio, P. O'Neill, J. Z. Pedersen, O. Carugo, G. Rotilio, A. Battistoni, and K. Djinovic-Carugo. 2004. Unique features of the sodC-encoded superoxide dismutase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a fully functional copper-containing enzyme lacking zinc in the active site. J. Biol. Chem. 279:33447-33455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Speert, D. P., M. Bond, R. C. Woodman, and J. T. Curnutte. 1994. Infection with Pseudomonas cepacia in chronic granulomatous disease: role of non-oxidative killing by neutrophils in host defense. J. Infect. Dis. 170:1524-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steinman, H. M. 1993. Function of periplasmic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 175:1198-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.St. John, G., and H. M. Steinman. 1996. Periplasmic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase of Legionella pneumophila: role in stationary-phase survival. J. Bacteriol. 178:1578-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vandamme, P., B. Holmes, T. Coenye, J. Goris, E. Mahenthiralingam, J. J. LiPuma, and J. R. Govan. 2003. Burkholderia cenocepacia sp. nov.—a new twist to an old story. Res. Microbiol. 154:91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vermis, K., T. Coenye, E. Mahenthiralingam, H. J. Nelis, and P. Vandamme. 2002. Evaluation of species-specific recA-based PCR tests for genomovar level identification within the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:937-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilks, K. E., K. L. Dunn, J. L. Farrant, K. M. Reddin, A. R. Gorringe, P. R. Langford, and J. S. Kroll. 1998. Periplasmic superoxide dismutase in meningococcal pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 66:213-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]