Abstract

Elite suppressors (ES) are untreated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals who control viremia to levels below the limit of detection of current assays. The mechanisms involved in this control have not been fully elucidated. Several studies have demonstrated that some ES are infected with defective viruses, but it remains unclear whether others are infected with replication-competent HIV-1. To answer this question, we used a sensitive coculture assay in an attempt to isolate replication-competent virus from a cohort of 10 ES. We successfully cultured six replication-competent isolates from 4 of the 10 ES. The frequency of latently infected cells in these patients was more than a log lower than that seen in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy with undetectable viral loads. Full-length sequencing of all six isolates revealed no large deletions in any of the genes. A few mutations and small insertions and deletions were found in some isolates, but phenotypic analysis of the affected genes suggested that their function remained intact. Furthermore, all six isolates replicated as well as standard laboratory strains in vitro. The results suggest that some ES are infected with HIV-1 isolates that are fully replication competent and that long-term immunologic control of replication-competent HIV-1 is possible.

Understanding the factors that affect the rate of disease progression in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals can provide insights that may be critical for the development of vaccines and immunotherapeutic strategies. HIV-1-infected individuals who remain asymptomatic and maintain normal CD4+ T-cell counts without treatment have been labeled long-term nonprogressors (LTNP). Two principal theories have been advanced to explain the LNTP state. One theory holds that LTNP are infected with defective viruses. Several studies of LTNP have detected viruses with gross defects in particular HIV-1 genes (3, 10, 14, 22, 24, 27, 34, 37, 49, 56). The most dramatic example comes from the Sydney Blood Bank Cohort. An HIV-1 isolate with a large deletion in Nef and the U3 region of the LTR was transmitted from an asymptomatic donor to multiple recipients. The donor and all of the recipients became LTNP (14, 29). Analysis of this cohort showed definitively that infection with an attenuated virus could lead to slowly progressive HIV-1 disease.

An alternative theory holds that LTNP have unusually effective immune response to HIV-1. CD8+ T cells from LTNP are very efficient at controlling viral replication in vitro (6, 11) and in vivo (16). More recent studies of cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses in LTNP have shown that, whereas there is no correlation between the frequency of gamma interferon-secreting CD8+ T cells and the viral load (1, 7), the ability of CD8+ T cells to proliferate in response to HIV-1 antigens is associated with long-term nonprogression (40). A similar correlation between proliferative responses of HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cells and long-term nonprogression has been demonstrated (48). Neutralizing antibody responses have also been examined in LTNP, and high-titer responses to lab strains and heterologous primary isolates have been reported (11, 43, 45, 46). However, studies examining neutralization of autologous virus have yielded conflicting results. Bradney et al. reported relatively low titers of antibodies (8), whereas a more recent study suggested that LTNP had higher titers than patients with progressive disease (15).

Initial studies of LTNP focused on the ability of these individuals to maintain relatively normal CD4 counts. When sensitive assays for plasma HIV-1 RNA were developed, it became clear that many LTNP had detectable plasma HIV-1 RNA. However, in a subset of LTNP, there is no clinically detectable viremia. These individuals are termed elite suppressors (ES). Initial studies by Migueles et al. provided striking evidence that many ES carry the HLA-B*57 allele, raising the possibility that CD8+ T-cell responses were involved in the control of viremia (41). However, the finding that some individuals with the same allele have progressive disease suggests that HLA-B*57-restricted CTL responses alone are not sufficient to explain control of viremia (39). The role of neutralizing antibodies in maintaining virologic suppression in ES has been examined in a recent study, which found only very low titers of neutralizing antibodies to contemporaneous, autologous isolates (4).

A major unresolved question regarding the mechanism of virologic suppression in ES is whether these individuals were infected with defective viruses. It has been very difficult to culture virus from these patients, and therefore most virologic studies of ES have been performed by the amplification of viral sequences from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with the PCR. Alexander et al. reported the isolation of replication-competent virus from LTNP, including an ES who had dropping CD4 counts and who was eventually placed on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) (3). A 100-amino-acid deletion in the nef protein was found in virus from this ES. Except for this unusual nef-deleted virus, there are no reports of successful isolation of replication-competent HIV-1 from ES.

Using a sensitive coculture assay, we and others have been able to isolate replication-competent virus from patients on HAART who have suppression of viremia to below the limit of detection (12, 17, 18, 52, 53, 55). Using the same assay, we describe here the successful isolation of replication-competent virus from 4 of 10 ES studied. To look for attenuating mutations in these viruses, we obtained full-length sequences and performed multiple phenotypic assays. The results of the present study strongly suggest that some ES harbor replication-competent HIV-1 which they control immunologically, a conclusion with major implications for the design of therapeutic HIV-1 vaccines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population.

We studied 10 HIV-1-seropositive individuals who maintained viral loads of <50 copies/ml without antiretroviral therapy. The CD4 counts ranged from 610 to 900. Table 1 lists the pertinent clinical characteristics of the ES studied. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Informed consent was obtained before phlebotomy.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of ES in this study

| Patient | Yr of diagnosis | CD4 count (cells/μl) | Viral load (copies/ml) | HLA genotype

|

Replication-competent virus isolated | Infected cell frequencya (IUPM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-A | HLA-B | ||||||

| ES1 | 1999 | 827 | <50 | 24,26 | 14,27 | + | 0.02 |

| ES4 | 1996 | 837 | <50 | 02,30 | 08,44 | + | 0.02 |

| ES8 | 2003b | 610 | <50 | 02,03 | 44,57 | + | 0.02 |

| ES10 | 2002 | 900 | <50 | 24,31 | 44,51 | + | 0.02 |

| ES2 | 1986 | 598 | <50 | 02,31 | 51,57 | - | <0.04c |

| ES3 | 1991 | 677 | <50 | 25,68 | 51,57 | - | <0.02 |

| ES6 | 1992 | 820 | <50 | 23 | 15,57 | - | <0.04 |

| ES7 | 1994 | 1,323 | <50 | 30,32 | 57,81 | - | <0.02 |

| ES9 | 1999 | 800 | <50 | 02,30 | 27,57 | - | <0.02 |

| ES13 | 1992 | 1,280 | <50 | NAd | NA | - | <0.02 |

That is, the frequency of resting CD4+ T cells harboring replication-competent virus in IUPM.

This patient was probably infected between 1996 and 1998.

For those ES from whom virus was not recovered, the maximum IUPM was determined from the number of resting CD4+ T cells placed in culture.

NA, not available.

Quantitation of latently infected cells.

Resting CD4+ T cells were purified from PBMC by bead depletion as previously described (52). Positive selection by flow cytometry was not performed due to the low yield of this step and the need to maximize the number of CD4+ T cells cultured. The resulting CD4+ T-cell populations (25 × 106 to 100 × 106 cells) were then cultured under limiting dilution using a previously described coculture assay (12). Infected cell frequencies were determined by the maximum-likelihood method and are expressed as infectious units per million (IUPM) resting CD4+ T cells.

Growth kinetics assay.

Culture supernatants containing 0.25 μg of p24 antigen were used to infect 3 × 106 CD4+ T-cell lymphoblasts by spinoculation (44). The cells were then washed once and cultured in RPMI medium containing 10 U of interleukin-2/ml. Aliquots of culture supernatant were taken at multiple time points, and p24 levels were measured with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Beckman Coulter).

Sequence analysis.

Virus culture experiments were carried out at limiting dilution, and thus each positive well contained a single HIV-1 isolate. Viral RNA was isolated from 20 to 140 μl of culture supernatants using a QIAGEN viral RNA isolation kit. The One-Step RT-PCR for long templates kit (Invitrogen) was used to amplify the following HIV-1 genes with published primers: the long terminal repeat (LTR) (38), pol (60), env (4), nef (23), and the accessory genes (37). We designed the 5′ primers 5′gagfullouter (5′-CGACGCAGGACTCGGC-3′) and 5′gagfullinner (5′-GCTGAAGCGCGCACGGC-3′) and used them in conjunction with previously described 3′ gag primers (39) to amplify the full-length gene. The region spanning RT-vpu was amplified by one-step reverse transcription-PCR with the 5′RT outer (42) and the accessory gene outer 2 (37) primers, followed by a second round of amplification with the 5′RT inner and accessory gene inner 2 primers using Platinum Taq HIFI (Invitrogen).

PCR products were gel purified by using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and directly sequenced by using an ABI Prism 3700 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Chromatograms were manually examined for the presence of double peaks to confirm that each culture isolate was clonal. Sequences were assembled by using CodonCode Aligner (version 1.3.1) to reconstruct the full-length HIV-1 sequence for each culture isolate. Phylogenetic tree estimation was performed by using the maximum-likelihood method with the HKY85+G model of evolution using PAUP* version 4b10 (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA).

CD4 downregulation.

CD4+ T-cell lymphoblasts were infected with culture supernatants as described above. On day 3, the cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody (Becton Dickinson) and then fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (Becton Dickinson). Intracellular staining for Gag was then performed with phycoerythrin-conjugated-Kc57 antibody (Beckman Coulter).

Functional analysis of the LTR.

The LTR from ES8-43 and from the reference strain NL4-3 were subcloned into the upstream region of the luciferase reporter gene in the plasmid pGL4.11 (Promega). These recombinant reporter plasmids were then transfected into 293T cells. For normalization of transfection efficiency and extract recovery, the transfection included the pCSK-lacZ vector, which constitutively expresses β-galactosidase (47). At 24 h after transfection with the reporter plasmids, 293T cells were stimulated with 10 ng of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α; R&D Systems)/ml. To measure the impact of the point mutation in TAR, 293T cells were also cotransfected with reporter plasmids and an HXB2 Tat expression vector. The luciferase activity was measured by using a luciferase assay system (Promega) and a luminometer (Central LB 960; Berthold) in accordance with the manufacturers' instructions. The β-galactosidase (β-Gal) activity was determined by using a chemiluminescent β-Gal reporter gene assay (Roche) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The degree of stimulation was calculated for each sample by dividing the luciferase activity, normalized to the β-Gal activity, by that observed in the basal-level control sample.

Rate of hypermutation.

Genomic DNA was isolated from resting CD4+ T cells as described previously (4). A 515-bp fragment was amplified from a region spanning env-nef by limiting-dilution nested PCR (31). This region was chosen due to its high rate of G→A hypermutation (57). In order to search for APOBEC3G-mediated deamination, unbiased primers were designed that excluded 5′-GG-3′ sites. The outer reaction was performed with the primers 5′ env out (5′-GAGCCTGTGCCTCTTCAG-3′; HXB2 [positions 8507 to 8524]) and 3′ nef out (5′-GGCTCATAGGGTGTAACAAG-3′; HXB2 [9285-9304]). The inner reaction was performed with primers 5′ env in (5′-CTACCACCGCTTGAGAGACTTA-3′; HXB2 [8525 to 8546]) and 3′ nef in (5′-GTAAGTCATTGGTCTTAAAGGTAC-3′; HXB2 [9016 to 9039]). Platinum PFX (Invitrogen) was used to ensure maximum fidelity. The PCR products were purified by using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN) and directly sequenced using 5′ env in as the sequencing primer. Nonclonal sequences were detected by examining chromatograms for the presence of characteristic double peaks. These sequences were subsequently discarded from the analysis. Sequences were aligned in Bioedit and examined for evidence of hypermutation.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences determined in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers EF363122 to EF363127.

RESULTS

Isolation of replication-competent virus from ES.

To determine whether ES harbor replication-competent virus, we used an enhanced virus culture assay that allows replication-competent virus from patients on HAART who have undetectable viral loads. Although there are no previous reports of the isolation of nondefective, replication-competent HIV-1 from ES, we successfully cultured virus from 4 of 10 ES studied using this approach (Table 1). Two clones each were obtained from patients ES1 and ES8. The median frequency of cells harboring replication-competent virus was approximately 0.02 IUPM resting CD4+ T cells, a frequency that is more than 1.5 logs lower than the average value seen in patients on HAART (52).

Sequence analysis.

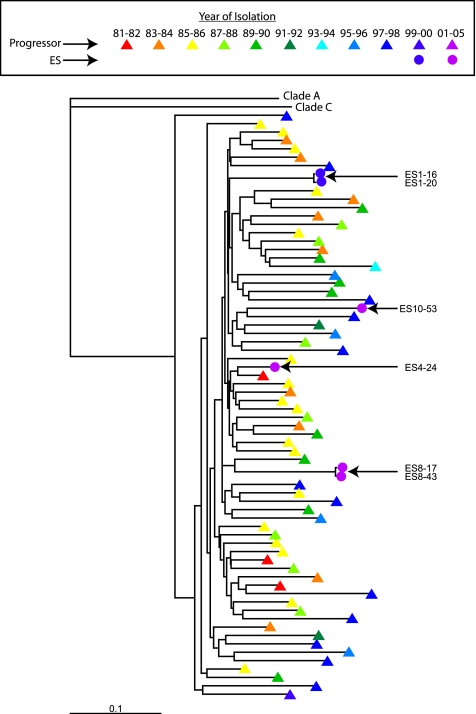

To determine whether the clones of replication-competent virus had any deletions or stop codons in any open reading frames, all six clones were fully sequenced. All six isolates were clade B viruses. A phylogenetic tree of full-length env sequences from each ES is shown in Fig. 1. The sequences from each ES patient are distinct and are separated by long branch lengths from env sequences of other ES isolates and of clade B isolates obtained at various time points from patients in the United States with progressive disease. The env sequence from ES4 clusters with an early U.S. isolate, but other ES isolates do not show this pattern. The gag sequence of both isolates from ES8 closely matched the sequence of multiple clones directly amplified from PBMC (5). In addition, for ES1, two isolates were obtained from different wells, and sequence analysis showed that they were almost identical. The same was true for ES8. This suggests the sequences reported are representative of the latent reservoir.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of ES clones. A phylogenetic tree of env sequences from ES1, -4, -8, and -10 (circles) and from U.S. clade B patients with progressive disease (triangles) was constructed by using a maximum-likelihood method. Colors indicate the year of isolation of each virus. Representative clade A and C env's are included for comparison.

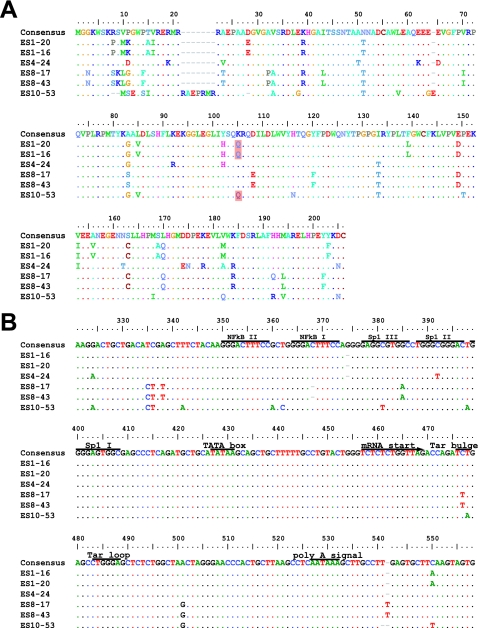

Although other studies have described large deletions in nef in ES and LTNP, we did not find stop codons or large deletions in nef (Fig. 2A) or in any other viral genes (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Most of the observed insertions and deletions were small and occurred in regions of length polymorphism. Isolate ES10-53 has a seven-amino-acid insertion and two small in-frame deletions in nef (Fig. 2A). These occurred within areas of known length polymorphism among clade B isolates (Table 2). A novel single nucleotide deletion in one of the two NF-κB binding sites in the LTR was seen in both isolates from ES8 (Fig. 2B). A C→T mutation in the Tat binding region of the LTR was also found in both of these isolates (Fig. 2B). Although this substitution has not been described in clade B viruses, it is seen in other clades. No obviously deleterious mutations were seen in the LTRs of the other four isolates. Viruses from ES1 had a two amino acid insertion in Vif at a position where similar insertions have been seen in some LTNP (Table 2 and Fig. 3) (2, 22).

FIG. 2.

Nef and LTR sequences of replication-competent viruses from ES. Sequences are aligned with the clade B consensus sequence. Dots indicate identity with the consensus sequence. Dashes indicate gaps. Numbering is by HXB2 coordinates. Polymorphisms detected in at least two of four ES and at least one third of ES clones but less than 10% of clade B sequences from the Los Alamos database are shaded in pink. (A) Nef sequences from ES show no stop codons or major deletions. The virus from ES10 had a two-amino-acid deletion (positions 9 and 10) that is also seen in 3 to 12% of sequences in the database and a seven-amino-acid tandem duplication resulting in an insertion at position 21 where there are insertions in 37% of clade B sequences. ES10 virus also had a single amino acid insertion after position 64. This same glutamic acid insertion is also seen in 17% of clade B sequences. Clones from ES1 and ES10 had a K→Q polymorphism at position 115 that was seen in <10% of clade B sequences in the database. None of these insertions, deletions, or polymorphisms affected Nef function as assessed by CD4 downregulation (see Fig. 2C). (B) Critical regions of the LTR are conserved in viruses from ES. LTR sequences appear normal with the exception that both clones from ES8 had a single nucleotide deletion in one of the two NF-κB binding sites. In addition, they had a C→T mutation in the Tar bulge region which is not seen in clade B viruses but which has been observed in other clades. There was also a single nucleotide insertion in the 5′ untranslated region of the mRNA in these isolates. These polymorphisms did not appear to affect the activation of transcription by NF-κB or Tat (see Fig. 2D).

TABLE 2.

Features of viral clones from ES

| Genetic feature and gene | ES with feature | Residue(s)a (nucleotide or amino acid) | Position(s)b (nucleotide or amino acid) | Frequency of feature among ES clones | Frequency of feature in clade Bc | Comment(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deletion | ||||||

| LTR | ES8 | C | 368 | 0.33 | 0.00 | Novel single nucleotide deletion in NF-κB site I |

| ES10 | T | 541 | 0.17 | 0.00 | Novel single nucleotide deletion in R region | |

| Gag | ES10 | T | 371 | 0.17 | 0.05 | Single-codon deletion in region of length polymorphism in p2 |

| Nef | ES10 | RS | 8, 9 | 0.17 | 0.03, 0.12 | Two-codon deletion in region of length polymorphism |

| D | 28 | 0.17 | 0.01 | Single-codon deletion at position of rare length polymorphism | ||

| Insertion | ||||||

| LTR | ES8, ES10 | G | 374 | 0.50 | 0.33 | Common insertion between NF-κB and Sp1 sites |

| ES8 | T | 541 | 0.33 | 0.00 | Single-nucleotide insertion in R region | |

| Gag | ES10 | AAAN | 117 | 0.17 | 0.14 | Located in region of length polymorphism between matrix and capsid, 14 amino acids upstream of protease cleavage site |

| ES8 | PSA | 457 | 0.33 | 0.09 | Located at site of length polymorphism in p6 between PTAP motif and first helical region | |

| ES8 | LID | 478 | 0.33 | 0.05 | Located in a region of length polymorphism in p6 between the helical regions | |

| Vif | ES1 | DN | 61 | 0.33 | <0.01 | Located in region of rare length polymorphism; reported polymorphisms are in LTNP |

| Vpu | ES1 | DRL | 4 | 0.33 | 0.02 | Located in region of length polymorphism upstream of the beginning of the transmembrane α-helix |

| ES1, ES8 | V | 64 | 0.67 | 0.03 | Located in region of length polymorphism near C terminus | |

| ES10 | GQLEM | 67 | 0.17 | 0.03 | Located in region of length polymorphism near C terminus | |

| Env | ES1, ES8 | W | 10 | 0.67 | 0.03 | Located in region of length polymorphism in signal peptide |

| ES10 | SWRWG | 14 | 0.17 | 0.09 | Located in region of length polymorphism in signal peptide | |

| Nef | ES10 | RAEPRMR | 21 | 0.17 | 0.37 | Located in a region of common length polymorphism |

| E | 64 | 0.17 | 0.17 | Located in a region of common length polymorphism in acid cluster | ||

| Recurrent polymorphismd | ||||||

| LTR | ES1, ES10 | A→C | 24 | 0.50 | 0.043 | Located in U3; results in rare K‡Q mutation in Nef |

| ES8, ES10 | A→C | 119 | 0.50 | 0.021 | Located in U3; silent in Nef | |

| ES1, ES8 | T→C | 252 | 0.67 | 0.064 | Located in U3; silent in Nef | |

| Gag | ES1, ES4, ES10 | D→N | 121 | 0.67 | 0.016 | Located in flexible region between matrix and capsid, 12 amino acids upstream of protease cleavage site |

| Pol | ES8, ES10 | K→R | 535 | 0.50 | 0.027 | Located in RT, residue 281 |

| Vif | ES1, ES8 | T→I | 67 | 0.67 | 0.047 | |

| Vpr | ES1, ES8 | I→T | 37 | 0.50 | 0.093 | Polymorphism at position of substantial variability |

| Tat | ES8, ES10 | F→Y | 32 | 0.50 | 0.056 | Conserved hydrophobic residue |

| ES1, ES10 | D→N | 80 | 0.50 | 0.028 | Located in second exon | |

| Tat | ES1, ES10 | R→T | 93 | 0.50 | 0.028 | Located in second exon |

| ES1, ES10 | D→A | 101 | 0.50 | 0.062 | Located in second exon | |

| Env | ES8, ES10 | K→M | 4 | 0.50 | 0.065 | Located in signal peptide |

| ES1, ES8 | L→W | 10 | 0.67 | 0.100 | Located in signal peptide | |

| Nef | ES1, ES10 | K→Q | 105 | 0.50 | 0.09 |

Residue(s) in clade B consensus sequence affected.

Position of the feature in HXB2 coordinates. Insertions occur after the indicated nucleotide or amino acid position in the reference HXB2 sequence. Gag numbering is from the first Met of Gag open reading frame. Env numbering is from the first Met in the Env open reading frame.

For insertions and deletions, this value reflects the frequency of any insertion or deletion at this position in all clade B sequences in the Los Alamos HIV Database.

Only polymorphisms found in at least two of four ES studied but in <10% of clade B isolates in the Los Alamos database are listed.

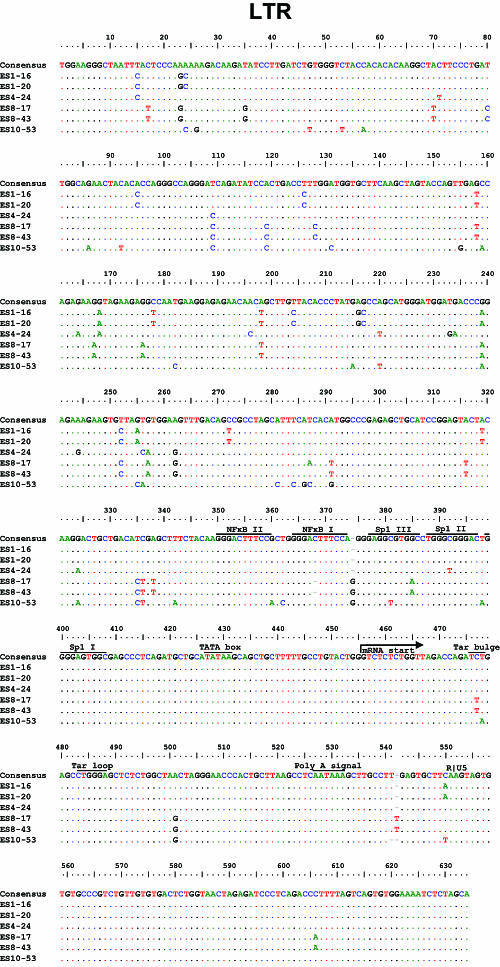

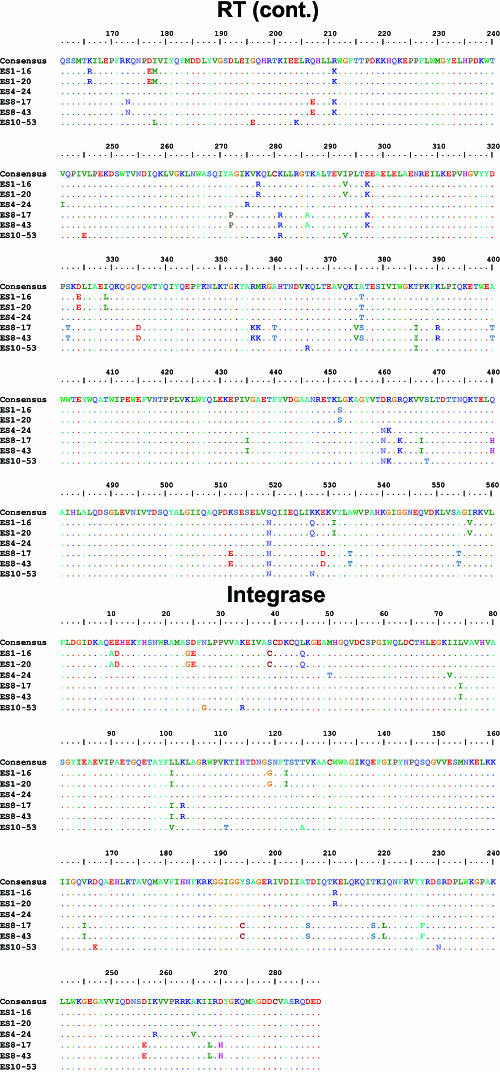

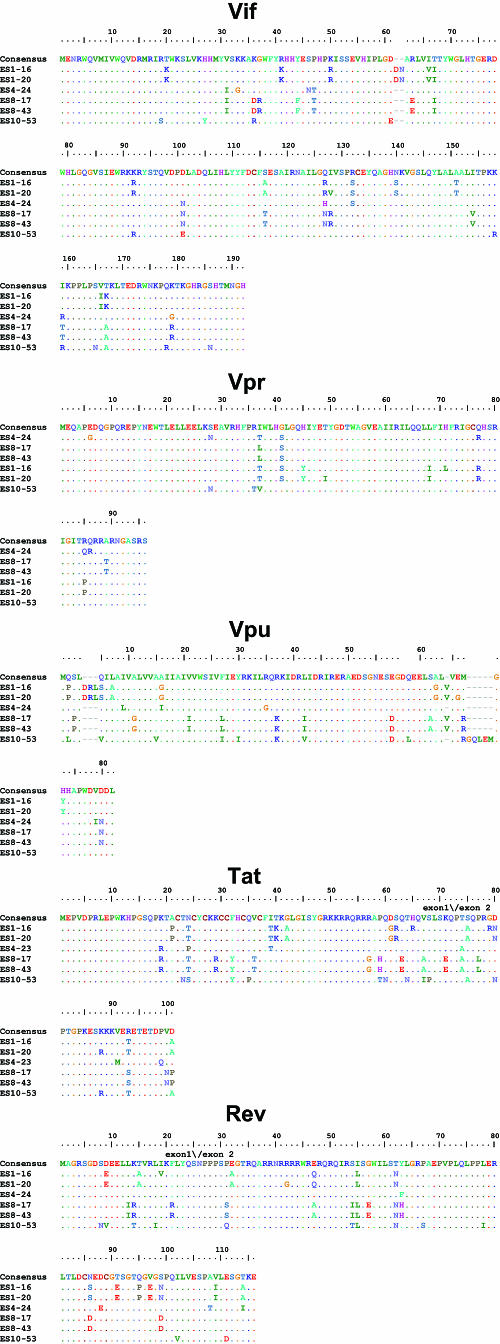

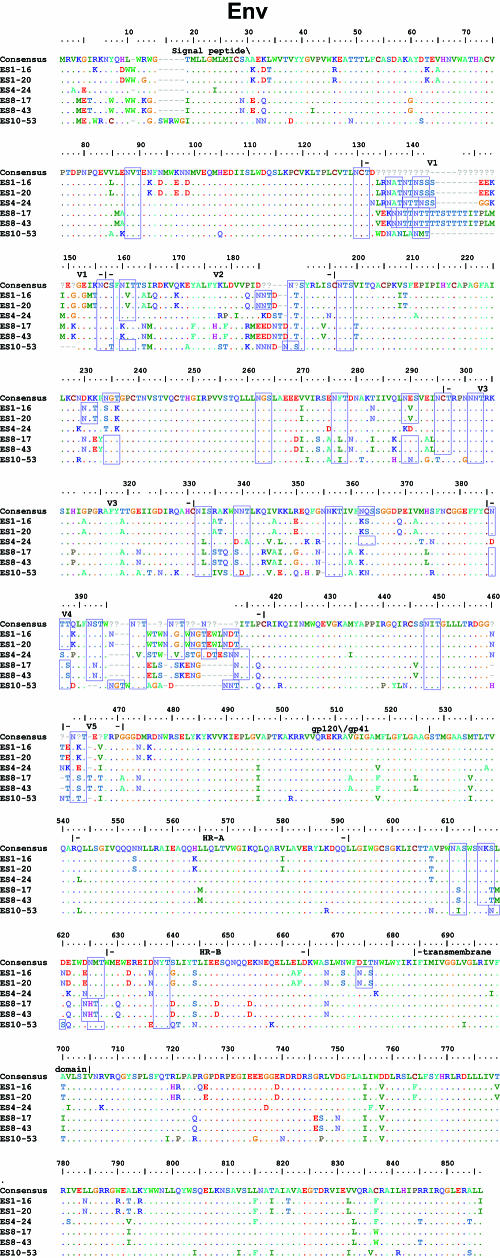

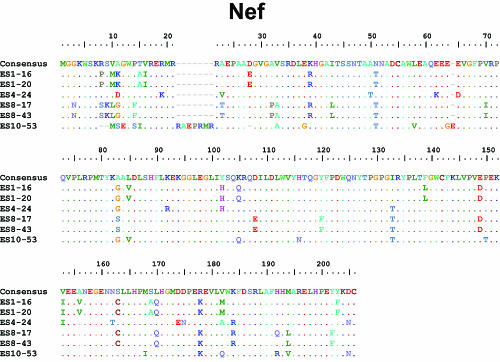

FIG. 3.

Sequences of HIV-1 clones from ES. Full-length sequences of six HIV-1 clones from ES were aligned with clade B consensus sequences. An alignment of nucleotides sequences is shown for the LTR. For coding regions, alignments of the amino acid sequences are shown. Dots indicate identity to the consensus sequence. Dashes indicate gaps. Numbering is by HXB2 coordinates. Potential N-linked glycosylation sites (N-X-S/T, where “X” is any amino acid except praline) in Env are indicated with blue boxes.

Analysis of full-length sequences of viral clones from ES did not reveal any signature mutations that were present in all ES viruses but rare or absent in viruses from progressors (Table 2). Of note, isolates from two of the four ES contained the Vpr R77Q mutation that has been previously linked to slow progression (Table 2 and Fig. 3) (32). This substitution is also seen in 36% of patients with progressive disease (32) and cannot by itself explain the control of viral replication in ES. The I78L Rev mutation was found in the isolate ES10-53. This mutation has also been previously been linked to slow progression (24). However, we recently found that this mutation did not revert to wild type after virological escape occurred in an ES (J. Bailey et al., unpublished data); hence, it is unlikely that this mutation alone can explain complete viral suppression in this patient.

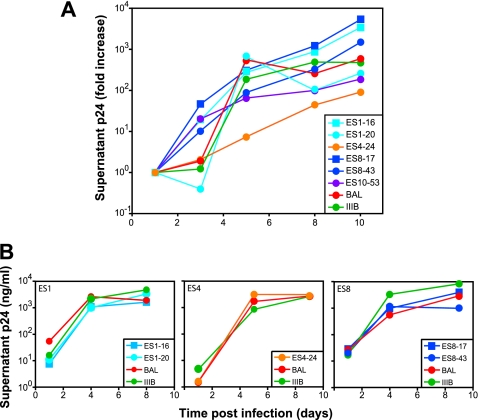

In vitro growth characteristics of HIV-1 isolated from ES.

Isolates from ES were obtained using a limiting-dilution culture assay in which viruses released from individual infected cells are expanded over the course of 2 to 3 weeks until a sufficient level of viral antigen is present in culture supernatants to allow detection by ELISA. Thus, only viruses capable of enormous in vitro expansion are isolated. To further characterize the growth properties of these viruses, we infected primary CD4+ T-cell lymphoblasts from normal donors with equal amounts of the six ES isolates or with BAL, a CCR5-tropic reference strain, or IIIB, a CXCR4-tropic reference virus. As seen in Fig. 4A, all six isolates replicated vigorously, and the levels of p24 protein increased by 2 to 4 logs over a 10-day period. Thus, relative to standard reference HIV-1 isolates, these ES viruses have no substantial defect in ability to replicate in primary CD4+ T cells. We also infected CD4+ T cells from ES1, ES4, and ES8 with either autologous virus or with reference strains (Fig. 4B). In each case, the viruses replicated vigorously, ruling out the possibility that the ES cells were intrinsically resistant to viral replication. All of the patient's isolates were R5 viruses since they failed to replicate in the highly susceptible MT-2 cell line which expresses CD4 and CXCR4 but not CCR5 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Functional activity of HIV-1 clones isolated from ES. (A) Growth kinetics of six clones from ES compared to the BA-L and IIIB reference strains. (B) Growth kinetics of reference strains and autologous HIV-1 isolates in CD4+ T-cell lymphoblasts from ES1, ES4, and ES8.

Functional characterization of viruses from ES.

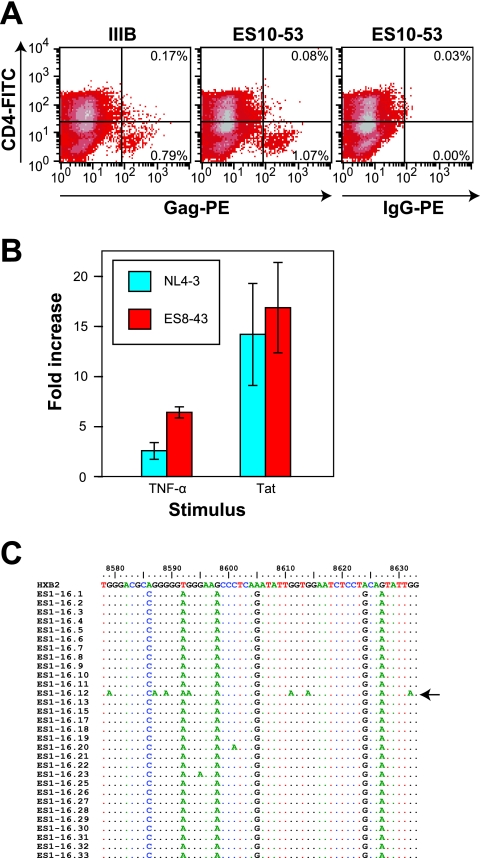

Taken together, these results suggest that some ES harbor viruses that are fully competent for in vitro replication. We examined the functional effects of the minor sequence abnormalities detected in the genomic sequences. To assess the effect of the seven-amino-acid insertion in ES10-53 Nef, we measured CD4 downregulation, the most extensively characterized function of Nef. CD4+ lymphoblasts were infected with either ES10-53 and or IIIB. As seen in Fig. 5A, cells infected with either ES10-53 or IIIB (Gag-positive cells) showed equally efficient downregulation of surface CD4. The insertion was not in the region of Nef that plays a role in major histocompatibility complex downregulation, and thus this function was not assessed.

FIG. 5.

Functional activity of HIV-1 genes with mutations. (A) CD4 downregulation in lymphoblasts infected with either ES10-53 or the IIIB reference strain. Infected cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibodies to CD4 and then fixed, permeabilized, and stained for intracellular HIV-1 Gag antigen. The numbers indicate the percentage of infected (Gag positive) cells that have either normal or downregulated levels of CD4 on their surface. (B) Functional activity of the LTR from ES8-43 (red) and the reference clone NL4-3 (blue). The fold increase in transcriptional activity in response to TNF-α or Tat stimulation is shown. (C) Functional activity of Vif from clone ES1-16 grown in PBMC. A region of the genome that is subject to a high rate of hypermutation in the absence of Vif was amplified from the DNA of lymphoblasts infected with ES1-16 by using limiting dilution PCR. 30 independent clones were sequenced. Only a single clone (arrow) had evidence of G-to-A hypermutation.

We characterized the functional effects of the single-base deletion in the LTR of virus from ES8. The deletion occurred in one of the two binding sites for the transcription factor NF-κB. It was thus possible that transcriptional activation mediated by this critical host factor was impaired. The C-to-T substitution in the TAR bulge region could also potentially affect the binding of HIV-1 Tat and the stimulation of transcriptional elongation. To assess these potential defects, the LTRs from ES8 and the reference strain NL4-3 were cloned into a luciferase-expressing reporter vector, and 293T cells were transfected with the resulting constructs. The cells were then stimulated with TNF-α, a cytokine known to induce NF-κB-mediated transcriptional activation. Other cells were transfected with constructs that contained a functional Tat gene from NL4-3, as well as the LTR reporter constructs. Figure 5B shows that the ES8-43 LTR responded as well as that of the reference strain to both TNF-α and Tat stimulation, suggesting that this LTR was still functional in spite of the deletion in one of the two NF-κB sites and the C→T substitution in TAR. The fact that ES8-17 and ES8-43 both replicated vigorously in culture is further evidence that the LTR was functional.

We next addressed the effect of the two-amino-acid insertion in Vif. Interestingly, clones isolated from two LTNP had similar insertions at the same position in Vif (2, 21). Although these clones replicated very poorly in vitro, both clones from ES1 replicated as well as the reference HIV-1 strains (Fig. 2A and B). Vif has been shown to play an important role in pathogenesis via its ability to induce degradation of the host protein APOBEC3G and thereby prevent APOBEC3G-mediated hypermutation of HIV-1 (20, 30, 33, 35, 50, 51, 54, 58, 59). We therefore looked for evidence of increased hypermutation in proviral DNA of cells infected with replication-competent virus isolated from ES1. As is shown in Fig. 5C, only 1 of 30 env/nef clones independently amplified from CD4+ T-cell lymphoblasts that were infected in vitro with clone ES1-16 showed evidence of “G→A” hypermutation in the region of the genome that is most susceptible to hypermutation (33). Thus, Vif appeared to be functional in spite of this insertion. This conclusion is consistent with the fact that viruses isolated from ES1 grow normally in primary CD4+ T cells, which are nonpermissive for Vif-minus mutants (19).

DISCUSSION

We have isolated and characterized six clade B, R5 isolates from four ES. We sequenced the entire genome of these isolates and performed multiple functional studies to assess the replication capacity of the isolates. This is the first time that full-length sequence analysis has been performed on HIV-1 isolates obtained from multiple ES. We were not able to isolate virus from all of the ES studied. This could be a reflection of the difference in frequency of latently infected cells in ES. The ES from whom replication competent virus was obtained were generally infected for shorter periods of time than those patients from whom no virus was recovered. In contrast to prior studies where major deletions were seen in different genes in LTNP (3, 10, 14, 22, 24, 27, 34, 37, 49, 56), we found no insertions or deletions in virus cultured from ES4 and only minor alterations in some genes of the other isolates. Because of the enormous propensity of HIV-1 to accumulation sequence changes, any given HIV-1 isolate, including ones isolated from patients with progressive disease, will show some differences relative to a clade consensus sequence. The minor insertions and deletions and the small number of unique polymorphisms seen in these viruses were not unexpected. Of note, we recently sequenced the entire genome of HIV-1 isolated from an ES before and after virologic breakthrough (Bailey et al., unpublished). Interestingly, all of the insertions and deletions that were present in isolates obtained when the patient had an undetectable viral load were retained in plasma clones analyzed after breakthrough when his viral load was 13,000 copies/ml. Thus, it appears that these mutations may not be the cause of nonprogression. Furthermore, the changes present in the isolates of the 4 ES described here did not measurably affect the function of the relevant genes. It thus appears that all six isolates are fully replication competent, and all isolates grew normally in primary CD4+ T lymphoblasts.

The finding that ES harbor replication-competent viruses strongly suggests that host factors may be playing a key role in the control of viral replication in ES. The fact that primary isolates as well as reference HIV-1 strains replicated well in ES CD4+ T cells suggests that these patients do not have an intrinsic factor that inhibits HIV replication. We have previously shown that ES4, ES8, and ES10 have low titers of neutralizing antibodies to autologous virus (4). Thus, humoral immunity is probably not the explanation for the nonprogression in these patients. ES1 and ES8 are positive for the HLA-B*27 and HLA-B*57 allele groups, which are over-represented in LTNP (9, 13, 25, 26, 28, 36) and ES (41). HLA-B*44 has not been associated with slow progression, but three of the four ES had this allele. Interestingly, the gag genes of both replication-competent isolates from ES8 did not contain any escape mutations in HLA-B*57-restricted epitopes that were present in every sequence amplified from the free virus in the plasma of this individual (5). Thus, both isolates should be fully susceptible to HLA B*57-restricted CTL present in this patient (5). Taken together, it appears that in some cases, host factors such as CTL responses can control viral replication. Further study may shed light into the mechanisms involved in this control. Our results suggest that long-term immunologic control of fully pathogenic HIV-1 is possible.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jie Xu for excellent technical assistance and other members of the laboratory and Suzanne Gartner for helpful discussions.

This study was supported by NIH grant K08 AI51191 and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 December 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Addo, M. M., X. G. Yu, A. Rathod, D. Cohen, R. L. Eldridge, D. Strick, M. N. Johnston, C. Corcoran, A. G. Wurcel, C. A. Fitzpatrick, M. E. Feeney, W. R. Rodriguez, N. Basgoz, R. Draenert, D. R. Stone, C. Brander, P. J. Goulder, E. S. Rosenberg, M. Altfeld, and B. D. Walker. 2003. Comprehensive epitope analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific T-cell responses directed against the entire expressed HIV-1 genome demonstrate broadly directed responses, but no correlation to viral load. J. Virol. 77:2081-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander, L., M. J. Aquino-DeJesus, M. Chan, and W. A. Andiman. 2002. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication by a two-amino-acid insertion in HIV-1 Vif from a nonprogressing mother and child. J. Virol. 76:10533-10539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander, L., E. Weiskopf, T. C. Greenough, N. C. Gaddis, M. R. Auerbach, M. H. Malim, S. J. O'Brien, B. D. Walker, J. L. Sullivan, and R. C. Desrosiers. 2000. Unusual polymorphisms in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 associated with nonprogressive infection. J. Virol. 74:4361-4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey, J. R., K. G. Lassen, H. C. Yang, T. C. Quinn, S. C. Ray, J. N. Blankson, and R. F. Siliciano. 2006. Neutralizing antibodies do not mediate suppression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in elite suppressors or selection of plasma virus variants in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 80:4758-4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey, J. R., T. M. Williams, R. F. Siliciano, and J. N. Blankson. 2006. Maintenance of viral suppression in HIV-1-infected HLA-B*57+ elite suppressors despite CTL escape mutations. J. Exp. Med. 203:1357-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker, E., C. E. Mackewicz, G. Reyes-Teran, A. Sato, S. A. Stranford, S. H. Fujimura, C. Christopherson, S. Y. Chang, and J. A. Levy. 1998. Virological and immunological features of long-term human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals who have remained asymptomatic compared with those who have progressed to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Blood 92:3105-3114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betts, M. R., D. R. Ambrozak, D. C. Douek, S. Bonhoeffer, J. M. Brenchley, J. P. Casazza, R. A. Koup, and L. J. Picker. 2001. Analysis of total human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses: relationship to viral load in untreated HIV infection. J. Virol. 75:11983-11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradney, A. P., S. Scheer, J. M. Crawford, S. P. Buchbinder, and D. C. Montefiori. 1999. Neutralization escape in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected long-term nonprogressors. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1264-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brettle, R. P., A. J. McNeil, S. Burns, S. M. Gore, A. G. Bird, P. L. Yap, L. MacCallum, C. S. Leen, and A. M. Richardson. 1996. Progression of HIV: follow-up of Edinburgh injecting drug users with narrow seroconversion intervals in 1983-1985. AIDS 10:419-430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calugi, G., F. Montella, C. Favalli, and A. Benedetto. 2006. The entire genome of a nef-deleted strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 recovered 20 years after primary infection: large pool of env-deleted proviruses. J. Virol. 80:11892-11896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao, Y., L. Qin, L. Zhang, J. Safrit, and D. D. Ho. 1995. Virologic and immunologic characterization of long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:201-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun, T. W., L. Carruth, D. Finzi, X. Shen, J. A. DiGiuseppe, H. Taylor, M. Hermankova, K. Chadwick, J. Margolick, T. C. Quinn, Y. H. Kuo, R. Brookmeyer, M. A. Zeiger, P. Barditch-Crovo, and R. F. Siliciano. 1997. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature 387:183-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costello, C., J. Tang, C. Rivers, E. Karita, J. Meizen-Derr, S. Allen, and R. A. Kaslow. 1999. HLA-B*5703 independently associated with slower HIV-1 disease progression in Rwandan women. AIDS 13:1990-1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deacon, N. J., A. Tsykin, A. Solomon, K. Smith, M. Ludford-Menting, D. J. Hooker, D. A. McPhee, A. L. Greenway, A. Ellett, C. Chatfield, V. A. Lawson, S. Crowe, A. Maerz, S. Sonza, J. Learmont, J. S. Sullivan, A. Cunningham, D. Dwyer, D. Dowton, and J. Mills. 1995. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science 270:988-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deeks, S. G., B. Schweighardt, T. Wrin, J. Galovich, R. Hoh, E. Sinclair, P. Hunt, J. M. McCune, J. N. Martin, C. J. Petropoulos, and F. M. Hecht. 2006. Neutralizing antibody responses against autologous and heterologous viruses in acute versus chronic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: evidence for a constraint on the ability of HIV to completely evade neutralizing antibody responses. J. Virol. 80:6155-6164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Quiros, J. C., W. L. Shupert, A. C. McNeil, J. C. Gea-Banacloche, M. Flanigan, A. Savage, L. Martino, E. E. Weiskopf, H. Imamichi, Y. M. Zhang, J. Adelsburger, R. Stevens, P. M. Murphy, P. A. Zimmerman, C. W. Hallahan, R. T. Davey, Jr., and M. Connors. 2000. Resistance to replication of human immunodeficiency virus challenge in SCID-Hu mice engrafted with peripheral blood mononuclear cells of nonprogressors is mediated by CD8+ T cells and associated with a proliferative response to p24 antigen. J. Virol. 74:2023-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finzi, D., J. Blankson, J. D. Siliciano, J. B. Margolick, K. Chadwick, T. Pierson, K. Smith, J. Lisziewicz, F. Lori, C. Flexner, T. C. Quinn, R. E. Chaisson, E. Rosenberg, B. Walker, S. Gange, J. Gallant, and R. F. Siliciano. 1999. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat. Med. 5:512-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finzi, D., M. Hermankova, T. Pierson, L. M. Carruth, C. Buck, R. E. Chaisson, T. C. Quinn, K. Chadwick, J. Margolick, R. Brookmeyer, J. Gallant, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. D. Richman, and R. F. Siliciano. 1997. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278:1295-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabuzda, D. H., K. Lawrence, E. Langhoff, E. Terwilliger, T. Dorfman, W. A. Haseltine, and J. Sodroski. 1992. Role of vif in replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 66:6489-6495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris, R. S., K. N. Bishop, A. M. Sheehy, H. M. Craig, S. K. Petersen-Mahrt, I. N. Watt, M. S. Neuberger, and M. H. Malim. 2003. DNA deamination mediates innate immunity to retroviral infection. Cell 113:803-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassaine, G., I. Agostini, D. Candotti, G. Bessou, M. Caballero, H. Agut, B. Autran, Y. Barthalay, and R. Vigne. 2000. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vif gene in long-term asymptomatic individuals. Virology 276:169-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, Y., L. Zhang, and D. D. Ho. 1998. Characterization of gag and pol sequences from long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Virology 240:36-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang, Y., L. Zhang, and D. D. Ho. 1995. Biological characterization of nef in long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 69:8142-8146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iversen, A. K., E. G. Shpaer, A. G. Rodrigo, M. S. Hirsch, B. D. Walker, H. W. Sheppard, T. C. Merigan, and J. I. Mullins. 1995. Persistence of attenuated rev genes in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected asymptomatic individual. J. Virol. 69:5743-5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaslow, R. A., M. Carrington, R. Apple, L. Park, A. Munoz, A. J. Saah, J. J. Goedert, C. Winkler, S. J. O'Brien, C. Rinaldo, R. Detels, W. Blattner, J. Phair, H. Erlich, and D. L. Mann. 1996. Influence of combinations of human major histocompatibility complex genes on the course of HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 2:405-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keet, I. P., J. Tang, M. R. Klein, S. LeBlanc, C. Enger, C. Rivers, R. J. Apple, D. Mann, J. J. Goedert, F. Miedema, and R. A. Kaslow. 1999. Consistent associations of HLA class I and II and transporter gene products with progression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in homosexual men. J. Infect. Dis. 180:299-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirchhoff, F., T. C. Greenough, D. B. Brettler, J. L. Sullivan, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1995. Brief report: absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein, M. R., I. P. Keet, J. D'Amaro, R. J. Bende, A. Hekman, B. Mesman, M. Koot, L. P. de Waal, R. A. Coutinho, and F. Miedema. 1994. Associations between HLA frequencies and pathogenic features of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in seroconverters from the Amsterdam cohort of homosexual men. J. Infect. Dis. 169:1244-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Learmont, J. C., A. F. Geczy, J. Mills, L. J. Ashton, C. H. Raynes-Greenow, R. J. Garsia, W. B. Dyer, L. McIntyre, R. B. Oelrichs, D. I. Rhodes, N. J. Deacon, and J. S. Sullivan. 1999. Immunologic and virologic status after 14 to 18 years of infection with an attenuated strain of HIV-1: a report from the Sydney Blood Bank Cohort. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:1715-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lecossier, D., F. Bouchonnet, F. Clavel, and A. J. Hance. 2003. Hypermutation of HIV-1 DNA in the absence of the Vif protein. Science 300:1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, S. L., A. G. Rodrigo, R. Shankarappa, G. H. Learn, L. Hsu, O. Davidov, L. P. Zhao, and J. I. Mullins. 1996. HIV quasispecies and resampling. Science 273:415-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lum, J. J., O. J. Cohen, Z. Nie, J. G. Weaver, T. S. Gomez, X. J. Yao, D. Lynch, A. A. Pilon, N. Hawley, J. E. Kim, Z. Chen, M. Montpetit, J. Sanchez-Dardon, E. A. Cohen, and A. D. Badley. 2003. Vpr R77Q is associated with long-term nonprogressive HIV infection and impaired induction of apoptosis. J. Clin. Investig. 111:1547-1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mangeat, B., P. Turelli, G. Caron, M. Friedli, L. Perrin, and D. Trono. 2003. Broad antiretroviral defense by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts. Nature 424:99-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mariani, R., F. Kirchhoff, T. C. Greenough, J. L. Sullivan, R. C. Desrosiers, and J. Skowronski. 1996. High frequency of defective nef alleles in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 70:7752-7764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marin, M., K. M. Rose, S. L. Kozak, and D. Kabat. 2003. HIV-1 Vif protein binds the editing enzyme APOBEC3G and induces its degradation. Nat. Med. 9:1398-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNeil, A. J., P. L. Yap, S. M. Gore, R. P. Brettle, M. McColl, R. Wyld, S. Davidson, R. Weightman, A. M. Richardson, and J. R. Robertson. 1996. Association of HLA types A1-B8-DR3 and B27 with rapid and slow progression of HIV disease. QJM 89:177-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michael, N. L., G. Chang, L. A. d'Arcy, P. K. Ehrenberg, R. Mariani, M. P. Busch, D. L. Birx, and D. H. Schwartz. 1995. Defective accessory genes in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected long-term survivor lacking recoverable virus. J. Virol. 69:4228-4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michael, N. L., L. D'Arcy, P. K. Ehrenberg, and R. R. Redfield. 1994. Naturally occurring genotypes of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat display a wide range of basal and Tat-induced transcriptional activities. J. Virol. 68:3163-3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Migueles, S. A., A. C. Laborico, H. Imamichi, W. L. Shupert, C. Royce, M. McLaughlin, L. Ehler, J. Metcalf, S. Liu, C. W. Hallahan, and M. Connors. 2003. The differential ability of HLA B*5701+ long-term nonprogressors and progressors to restrict human immunodeficiency virus replication is not caused by loss of recognition of autologous viral gag sequences. J. Virol. 77:6889-6898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Migueles, S. A., A. C. Laborico, W. L. Shupert, M. S. Sabbaghian, R. Rabin, C. W. Hallahan, D. Van Baarle, S. Kostense, F. Miedema, M. McLaughlin, L. Ehler, J. Metcalf, S. Liu, and M. Connors. 2002. HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell proliferation is coupled to perforin expression and is maintained in nonprogressors. Nat. Immunol. 3:1061-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Migueles, S. A., M. S. Sabbaghian, W. L. Shupert, M. P. Bettinotti, F. M. Marincola, L. Martino, C. W. Hallahan, S. M. Selig, D. Schwartz, J. Sullivan, and M. Connors. 2000. HLA B*5701 is highly associated with restriction of virus replication in a subgroup of HIV-infected long-term nonprogressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:2709-2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monie, D., R. P. Simmons, R. E. Nettles, T. L. Kieffer, Y. Zhou, H. Zhang, S. Karmon, R. Ingersoll, K. Chadwick, H. Zhang, J. B. Margolick, T. C. Quinn, S. C. Ray, M. Wind-Rotolo, M. Miller, D. Persaud, and R. F. Siliciano. 2005. A novel assay allows genotyping of the latent reservoir for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the resting CD4+ T cells of viremic patients. J. Virol. 79:5185-5202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montefiori, D. C., G. Pantaleo, L. M. Fink, J. T. Zhou, J. Y. Zhou, M. Bilska, G. D. Miralles, and A. S. Fauci. 1996. Neutralizing and infection-enhancing antibody responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in long-term nonprogressors. J. Infect. Dis. 173:60-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Doherty, U., W. J. Swiggard, and M. H. Malim. 2000. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 spinoculation enhances infection through virus binding. J. Virol. 74:10074-10080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pantaleo, G., S. Menzo, M. Vaccarezza, C. Graziosi, O. J. Cohen, J. F. Demarest, D. Montefiori, J. M. Orenstein, C. Fox, and L. K. Schrager. 1995. Studies in subjects with long-term nonprogressive human immunodeficiency virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:209-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pilgrim, A. K., G. Pantaleo, O. J. Cohen, L. M. Fink, J. Y. Zhou, J. T. Zhou, D. P. Bolognesi, A. S. Fauci, and D. C. Montefiori. 1997. Neutralizing antibody responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in primary infection and long-term-nonprogressive infection. J. Infect. Dis. 176:924-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pomerantz, J. L., E. M. Denny, and D. Baltimore. 2002. CARD11 mediates factor-specific activation of NF-κB by the T-cell receptor complex. EMBO J. 21:5184-5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenberg, E. S., J. M. Billingsley, A. M. Caliendo, S. L. Boswell, P. E. Sax, S. A. Kalams, and B. D. Walker. 1997. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T-cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science 278:1447-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salvi, R., A. R. Garbuglia, A. Di Caro, S. Pulciani, F. Montella, and A. Benedetto. 1998. Grossly defective nef gene sequences in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-seropositive long-term nonprogressor. J. Virol. 72:3646-3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheehy, A. M., N. C. Gaddis, J. D. Choi, and M. H. Malim. 2002. Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418:646-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheehy, A. M., N. C. Gaddis, and M. H. Malim. 2003. The antiretroviral enzyme APOBEC3G is degraded by the proteasome in response to HIV-1 Vif. Nat. Med. 9:1404-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siliciano, J. D., J. Kajdas, D. Finzi, T. C. Quinn, K. Chadwick, J. B. Margolick, C. Kovacs, S. J. Gange, and R. F. Siliciano. 2003. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat. Med. 9:727-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siliciano, J. D., and R. F. Siliciano. 2005. Enhanced culture assay for detection and quantitation of latently infected, resting CD4+ T cells carrying replication-competent virus in HIV-1-infected individuals. Methods Mol. Biol. 304:3-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stopak, K., C. de Noronha, W. Yonemoto, and W. C. Greene. 2003. HIV-1 Vif blocks the antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by impairing both its translation and intracellular stability. Mol. Cell 12:591-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong, J. K., M. Hezareh, H. F. Gunthard, D. V. Havlir, C. C. Ignacio, C. A. Spina, and D. D. Richman. 1997. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science 278:1291-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamada, T., and A. Iwamoto. 2000. Comparison of proviral accessory genes between long-term nonprogressors and progressors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Arch. Virol. 145:1021-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu, Q., R. Konig, S. Pillai, K. Chiles, M. Kearney, S. Palmer, D. Richman, J. M. Coffin, and N. R. Landau. 2004. Single-strand specificity of APOBEC3G accounts for minus-strand deamination of the HIV genome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:435-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu, X., Y. Yu, B. Liu, K. Luo, W. Kong, P. Mao, and X. F. Yu. 2003. Induction of APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation by an HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-SCF complex. Science 302:1056-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang, H., B. Yang, R. J. Pomerantz, C. Zhang, S. C. Arunachalam, and L. Gao. 2003. The cytidine deaminase CEM15 induces hypermutation in newly synthesized HIV-1 DNA. Nature 424:94-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang, H., Y. Zhou, C. Alcock, T. Kiefer, D. Monie, J. Siliciano, Q. Li, P. Pham, J. Cofrancesco, D. Persaud, and R. F. Siliciano. 2004. Novel single-cell-level phenotypic assay for residual drug susceptibility and reduced replication capacity of drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 78:1718-1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]