Abstract

Recombinant adenoviruses have emerged as promising agents in therapeutic gene transfer, genetic vaccination, and viral oncolysis. Therapeutic applications of adenoviruses, however, would benefit substantially from targeted virus cell entry, for example, into cancer or immune cells, as opposed to the broad tropism that adenoviruses naturally possess. Such tropism modification of adenoviruses requires the deletion of their natural cell binding properties and the incorporation of cell binding ligands. The short fibers of subgroup F adenoviruses have recently been suggested as a tool for genetic adenovirus detargeting based on the reduced infectivity of corresponding adenovectors with chimeric fibers in vitro and in vivo. The goal of our study was to determine functional insertion sites for peptide ligands in the adenovirus serotype 41 (Ad41) short fiber knob. With a model peptide, CDCRGDCFC, we could demonstrate that ligand incorporation into three of five analyzed loops of the knob, namely, EG, HI, and IJ, is feasible without a loss of fiber trimerization. The resulting adenovectors showed enhanced infectivity for various cell types, which was superior to that of viruses with the same peptide fused to the fiber C terminus. Strategies to further augment gene transfer efficacy by extension of the fiber shaft, insertion of tandem copies of the ligand peptide, or extension of the ligand-flanking linkers failed, indicating that precise ligand positioning is pivotal. Our study establishes that internal ligand incorporation into a short-shafted adenovirus fiber is feasible and suggests the Ad41 short fiber with ligand insertion into the top (IJ loop) or side (EG and HI loops) of the knob domain as a novel platform for genetic targeting of therapeutic adenoviruses.

Recombinant adenoviruses represent promising tools for therapeutic gene transfer, genetic vaccination, and viral oncolysis (2, 6, 24, 48). These applications benefit from the stability of recombinant adenoviruses, from their capacity for large heterologous DNA inserts, from their capability for efficient gene transfer into dividing and nondividing cells, and from established manufacturing technology, which facilitates high-titer virus preparations. Importantly, most gene transfer, genetic vaccination, and oncolysis applications would benefit substantially from—or even require—targeted virus cell entry. This is relevant, for example, for toxin gene transfer and viral oncolysis in cancer therapy or for targeting of dendritic cells in genetic vaccination approaches. Because of the broad tropism that adenoviruses naturally possess, such targeted viruses need to be engineered (30). Moreover, several target cells of interest, such as primary cancer cells or cells of the hematopoietic lineage, lack expression of the receptor CAR (for coxsackie- and adenovirus receptor) specific for the most commonly used adenovirus serotype, adenovirus type 5 (Ad5). This mandates tropism modification of recombinant adenoviruses in order to allow for efficient viral cell entry per se. We previously developed oncolytic adenoviruses that feature highly selective replication in melanoma cells resulting from the expression of both the E1A and E4 genes from optimized tyrosinase promoters (4, 27). Furthermore, we revealed that several primary melanoma cell cultures were resistant to transduction by adenovectors or to killing by oncolytic adenoviruses which contain an Ad5 capsid (28, 43). Importantly, by replacing the Ad5 fiber knob with the fiber knob of subgroup B Ad3, we successfully combined efficient cell entry into primary melanoma cells with highly selective replication potential (32, 43). However, cell entry mediated by the Ad3 fiber knob was also increased for other cell types, including normal fibroblasts. Therefore, we are interested in developing strategies for targeting rather than nonselectively enhancing cell entry of oncolytic adenoviruses in order to further increase their selectivity, potency, and safety.

Targeting cell entry of adenoviruses requires both the ablation of the native adenovirus tropism, especially for hepatocytes, and the incorporation of targeting ligands into the virus capsid. These aims have been achieved by complexing adenoviruses with different types of bispecific adapter molecules (5). Genetic strategies of adenoviral tropism modification, however, are advantageous because they provide a one-component drug and, in the context of viral oncolysis, tropism-modified progeny viruses.

Genetic tropism modification of adenoviruses has been pursued by insertion of peptide ligands, such as RGD peptides, polylysine, or targeting peptides isolated by phage display technology, into the knob domain of the Ad5 fiber protein (14, 29, 46). Note that the insertion of recombinant antibody fragments as targeting ligands into adenovirus capsids is hampered by the improper folding of most antibodies in the cytosol, where adenovirus proteins are produced (as discussed in reference 12). Genetic deletion of the native adenovirus tropism has been pursued by mutating those motifs within the Ad5 fiber knob domain which mediate binding to the primary adenovirus receptor CAR. Ablation of CAR binding resulted in strongly reduced gene transfer efficacy in vitro but had no or only a minimal effect on hepatocyte transduction in vivo in mice, rats, and nonhuman primates (3, 22, 31, 33, 39, 40). Gene transfer efficacy was further reduced in vitro and in some, but not all, studies also in vivo by mutation of the RGD motif of the penton base, which binds to cellular integrins and thereby triggers virus internalization (1, 15, 23, 31, 37). However, ablation of integrin binding also affects postentry steps of the adenoviral life cycle, which might be required for targeted cell entry. These include endosomal release, which is penton dependent (37). Recent reports revealed that the fiber shaft plays an important role in adenovirus cell binding and entry. The mutation of a putative heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG)-binding KKTK motif in the Ad5 shaft resulted in reduced virus transduction in vitro and in vivo (31, 40, 41). Furthermore, replacement of the Ad5 fiber shaft with a short shaft derived from the Ad35 or short Ad40 fiber mediated reduced liver transduction (21, 25). Note that modification of the fiber shaft might affect virus cell binding directly, i.e., by ablation of HSPG binding, or indirectly by preventing the accessibility of the cell binding motif of the knob domain to its receptor (41, 47). In the context of genetic virus targeting, it is therefore important to ensure that ligands inserted into the knob domain retain their target cell binding capacity after modification of the fiber shaft. Finally, in addition to direct interactions between Ad5 and cellular receptors, blood factors have been described to bind to the Ad5 fiber knob and to provide a bridge for indirect cell binding and entry of Ad5 virions (38).

Recently, the short fibers of subgroup F adenovirus serotypes 40 and 41 were suggested as tools for adenovirus targeting (25). These adenovirus serotypes contain two fiber molecules, a long and a short fiber, with the former being responsible for cell binding via CAR. The function of the short fiber is not completely understood to date, and no cellular receptor has been described. Hence, it was hypothesized that it does not mediate cell binding (25, 34). In this regard, several studies observed that adenoviruses with chimeric fibers did not mediate efficient adenoviral gene transfer in vitro and in vivo (25, 31, 34, 35). In conclusion, the short fibers of subgroup F adenoviruses constitute a scaffold of interest for target ligand insertion into adenovirus capsids.

The prime objective of this study was to define insertion sites for targeting peptides in the Ad41 short fiber knob. Heretofore, functional internal ligand insertions have been reported for the long-shafted Ad5 fiber only (14, 29). Towards our goal, we inserted the RGD peptide CDCRGDCFC as a model ligand into five loops of the Ad41 short (Ad41s) fiber knob or fused it via one of two differently sized linkers to the knob's C terminus. Chimeric fibers contained the Ad41 short fiber shaft and Ad5 fiber tail domains. For one construct, we also generated a matching fiber with the Ad41s fiber tail in order to compare the efficiencies of fiber incorporation into Ad5 capsids. Recombinant fiber molecules were analyzed for trimerization and incorporation into Ad5-based virions. The transduction efficacies of the resulting viruses were assessed in melanoma cells and various primary normal cells. Finally, starting from one successful chimeric fiber with an internal peptide insertion site, we generated and characterized three derivatives, featuring a tandem RGD peptide insert, an extended, 83-amino-acid RGD-containing insert, or the long Ad5 fiber shaft with a mutated KKTK motif. We hypothesized that these derivatives might further enhance adenovirus transduction efficacy by improving the accessibility or avidity of the inserted peptide ligands for interaction with cellular integrins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

The human melanoma cell line SK-MEL-28 (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, VA) and 293T cells (kindly provided by G. Fey, Erlangen, Germany), which stably express the simian virus 40 large T antigen, allowing for the amplification of plasmids from the simian virus 40 origin of replication, were cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Primary melanoma cells were purified from skin metastases as previously described (28) and were cultivated in RPMI 1640 (Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium). 633 cells (45; kindly provided by Glen Nemerow and Dan Van Seggern, The Scripps Research Institute, San Diego, CA) complement Ad5 E1- and fiber-deleted adenoviruses and were cultivated in improved minimal essential medium (MEM) with zinc option (Richter's modification; Invitrogen) with 200 μg/ml hygromycin B (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), 200 μg/ml neomycin (Invitrogen), and 300 μg/ml Zeocin (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Media were supplemented with 10% (5% for 293T cells) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (PAA, Cölbe, Germany), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Cambrex). For primary melanoma cell cultures, 10 mM HEPES, 250 ng/ml amphotericin (both from Cambrex), and 0.1 mg/ml gentamicin (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany) were added. Primary normal human keratinocytes (NHK) (kindly provided by L. Chow, T. Broker, and S. Banerjee, Birmingham, AL) were recovered from neonatal foreskins and grown in serum-free keratinocyte medium (Invitrogen). Foreskin-derived primary normal human fibroblasts (NHF) (kindly provided by M. Marschall, Clinical Virology, Erlangen, Germany) were cultivated in Earle's MEM (Invitrogen) with 7.5% fetal bovine serum (PAA), 100 μg/ml gentamicin, and 2.4 mM l-glutamine. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC; a kind gift of C. Garlichs, Erlangen, Germany) were cultured in endothelial growth medium (PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany). All cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Fiber expression plasmids.

Plasmid pDV67 (45) was used for expression of the Ad5 fiber. Expression plasmids for the different Ad41 short fiber-derived constructs (see Fig. 1 for an outline) were cloned as follows. The adenovirus serotype 5 tripartite leader (first exon, first intron, and fused second and third exons) of plasmid pDV55 (45) was inserted as a BamHI/BglII fragment into the BamHI site of pcDNA3.1/Hygro+ (Invitrogen) to generate pcDNAtpl. Subsequently, pcDNAtpl was digested with BamHI, blunted, and religated to generate pcDNAtplB−. Open reading frames for the different fiber constructs were inserted into pcDNAtplB− as EcoRI/XbaI fragments by PCR cloning with Ad41 genomic DNA (kindly provided by J. Chroboczek, Grenoble, France). For insertion of RGD peptides, fiber constructs were generated to contain a GGSGG linker in the AB, DE, EG, HI, or IJ loop of the Ad41 short fiber knob. For C-terminal fusion, a (GS)5 linker or GSP(SA)4PGSGS long linker was introduced. The following oligonucleotides were used for PCR cloning: F41sATG_Eco, 5′-GATCGAATTCCACCATGAAAAGAACCAGAATTGAAG; F5ATG_Eco, 5′-GATCGAATTCCACCATGAAGCGCGCAAGACCGTCTG; F5/F41SRevnew, 5′-CTTGAGTGCTAATACCCCAGGGGGACTCTCTTG; F5/F41Sfornew, 5′-CCTGGGGTATTAGCACTCAAGTACACTGACC; F41rev_Xba, 5′-GATCTCTAGATCATTATTGTTCAGTTATGTAGCAAAATAC; F41revlonglink_Xba, 5′-GATCTCTAGAGGATCCGGAGCCGGGCGCGCTG; SBLF41revnew, 5′-CGATTACGTAGGATCCGGAGCCGGGCGCGCTGGCCGACGCGCTGGCGGAGGGAGATCCTTGTTCAGTTATGTAGCAAAATACAG; F41revlink_Xba, 5′-GATCTCTAGAGGATCCCGAGCCACTGCCCGACCCGGAGCCTTGTTCAGTTATGTAGCAAAATAC; F41sIJlinkfor, 5′-GAACCGGGAGGATCCGGAGGGGGAAAACCTTTTCACCCACC; F41sIJlinkrev, 5′-CCCTCCGGATCCTCCCGGTTCGGCTGACCATTTAAAAG; F41sDElinkfor, 5′-TCATCCGGAGGATCCGGAGGGACCTGGCGTTACCAGGAAACC; F41sDElinkrev, 5′-CCCTCCGGATCCTCCGGATGATTCCAAGGCACAG; F41sEGlinkfor, 5′-CCACGAGGAGGATCCGGAGGGAACAAAACCGCTCACCCGGGC; F41sEGlinkrev, 5′-CCCTCCGGATCCTCCTCGTGGATACACTGTACTGTTG; F41sHIlinkfor, 5′-GATAAACGGAGGATCCGGAGGGAGTGGGTATGCTTTTACTTTTAAATG; F41sHIlinkrev, 5′-CCCTCCGGATCCTCCGTTTATCTCGTTGTAGACGACAC; F41sABlinkfor, 5′-CATTTATGGAGGATCCGGAGGGGAAACCCAAGATGCAAACCTATTTC; and F41sABlinkrev, 5′-CCCTCCGGATCCTCCATAAATGGAGCAGTTAGGCGTAG. Subsequently, sequences encoding the CDCRGDCFC peptide were inserted into the BamHI sites of the linkers by oligonucleotide cloning. For internal insertion, oligonucleotides RGDts (5′-GATCGTGTGACTGCAGGGGAGACTGTTTCTGCG) and RGDbs (5′-GATCCGCAGAAACAGTCTCCCCTGCAGTCACAC) were used, and for C-terminal insertion, oligonucleotides RGD_stop_ts (5′-GATCGTGTGACTGCAGGGGAGACTGTTTCTGCTGATAAG) and RGD_stop_bs (5′-GATCCTTATCAGCAGAAACAGTCTCCCCTGCAGTCACAC) were used. An expression plasmid for the Ad5/41s chimeric fiber with the 83-amino-acid RGD-containing loop of the Ad5 penton base (8) in the IJ fiber loop was generated by insertion of a PCR fragment into the BamHI site of the linker, using oligonucleotides PentonRGD_Bglfor (5′-GATCAGATCTACCGAACAGGGCGGGG) and PentonRGD_Bamrev (5′-GATCGGATCCCAGGGGTTTGATCACCGGTTT). A construct encoding a chimeric fiber with the Ad5 tail and shaft containing a mutated heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan binding site (41) and the knob of the Ad41 short fiber with the RGD peptide in the IJ loop was cloned by one step with the oligonucleotides Ad41sAgeIERVfor (5′-GATCACCGGTGATATCTCGCCTACGCCTAACTGC) and F41rev_Xba (see above) and by subsequent two-step PCR with oligonucleotides F5_AgeI_for (5′-TGACACGGAAACCGGTCCTC), KKTKrev (5′-ATGTTTGAGGCTCCGGCTCCGAGAGGTGGGCTCACAGTGG), KKTKfor (5′-GGAGCCGGAGCCTCAAACATAAACCTGGAAATATCTG), and F5shaft_NruI rev (5′-GATCTCGCGACCAAATAGTTAGCTTATCATTATTTTTGTTTC).

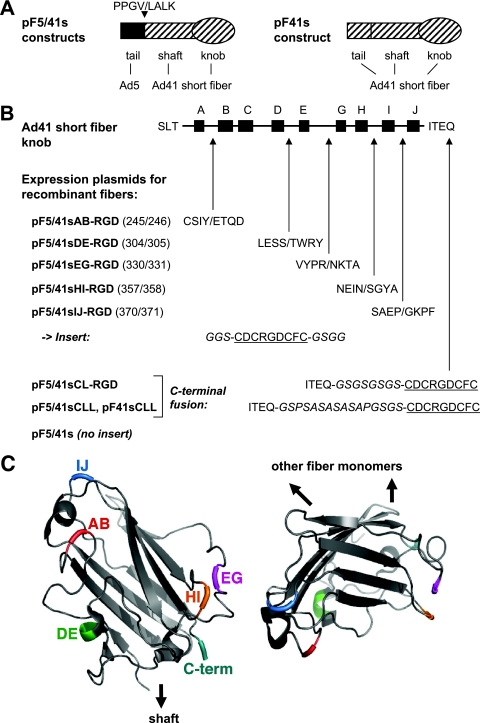

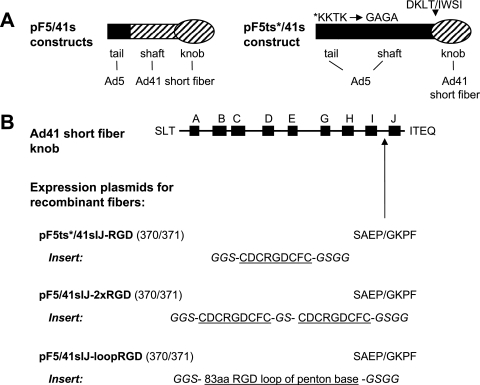

FIG. 1.

Outline of RGD peptide insertions into various positions of the Ad41s fiber knob. (A) Expression plasmids based on pF5/41s encode recombinant fiber proteins with the Ad5 fiber tail (amino acids 1 to 46) fused to the Ad41s fiber shaft and knob (starting with amino acid 45), resulting in the fusion site sequence PPGV/LALK. Plasmid pF41sCLL-RGD is based on a construct that encodes a recombinant fiber protein with the tail, shaft, and knob domains of the Ad41s fiber. (B) A CDCRGDCFC peptide with the indicated linkers (italic) was inserted into the AB, DE, EG, HI, or IJ loop of the Ad41s fiber knob (illustrated at the top), generating pF5/41sAB-RGD, pF5/41sDE-RGD, pF5/41sEG-RGD, pF5/41sHI-RGD, and pF5/41sIJ-RGD, respectively (numbers in parentheses refer to the amino acid positions of the Ad41s fiber that flank the insertion site; amino acids that flank the insertion site are shown in single-letter code). Fusion of the peptide via a short linker and a long linker to the C terminus of the Ad41s fiber knob resulted in pF5/41sCL-RGD and pF5/41sCLL-RGD, respectively. Plasmid pF41sCLL-RGD is identical to pF5/41sCLL-RGD but contains the tail domain of the Ad41s fiber. (C) Structure of the Ad41s fiber knob (36), with positions chosen for insertion of the RGD peptide indicated in color. (Left panel) Knob monomer seen from the side (its position relative to the fiber shaft is indicated); (right panel) knob monomer seen from the top (positions of interacting monomers in the trimeric molecule are indicated). Structures were visualized using the program PyMOL (13).

Generation of adenoviruses.

Adenovirus Ad5.βgal.ΔF (44) was propagated on 633 cells (45), which were treated with 0.3 μM dexamethasone for 24 h prior to and during infection. Ad5.βgal.ΔF is an E1-, E3-, and fiber-deleted adenovirus vector that contains a β-galactosidase (β-Gal) reporter cassette in the E1 region. During propagation in 633 cells, the Ad5 fiber protein is complemented, thus generating Ad5.βgal.ΔF/F+, which contains the wild-type Ad5 fiber but no fiber gene. Mutated fiber proteins were incorporated into adenoviral particles by using a transient transfection/infection system (modified by the method of Jakubczak et al. [18]). For each virus preparation, four T175 tissue culture flasks of 80% confluent 293T cells were transfected with fiber expression plasmids, using either Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) or Nanofectin (PAA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 100 μg DNA in 2 ml OptiMEM (Invitrogen) was mixed with 300 μl Lipofectamine in 2 ml OptiMEM and incubated for 20 min. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and subsequently, 10 ml OptiMEM and 1 ml transfection mix were added to each flask. The transfection mix was replaced by 28 ml growth medium after 4 h of incubation. For Nanofectin transfections, 100 μg DNA in 5 ml 150 mM NaCl and 200 μl Nanofectin in 5 ml 150 mM NaCl were mixed by adding the Nanofectin solution to the DNA solution and were then incubated for 20 min. The medium on the cells was replaced by 10 ml fresh growth medium and 2.5 ml transfection mixture, added dropwise to each flask. After 4 h of incubation, 18 ml of growth medium was added. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were infected with 2e11 viral particles (VP)/flask of Ad5.βgal.ΔF/F+ in infection medium (similar to growth medium, but with 2% fetal calf serum [FCS]). Cells were carefully agitated for 1 h, and after further incubation for 2 h, the infection medium was replaced by growth medium. The medium was replaced by fresh medium the next day, and cells were harvested at 2 days postinfection, when complete cytopathic effect was observed. All viruses were purified by two rounds of cesium chloride equilibrium density gradient ultracentrifugation. Verification of adenovirus preparations and exclusion of wild-type contamination were performed by PCR. Physical particle concentrations (VP/ml) were determined by reading the optical density at 260 nm for Ad5.βgal.ΔF/F+ and for viruses produced by Lipofectamine transfection. Physical particle concentrations for viruses produced by Nanofectin transfection were determined by real-time PCR. The infectious particle concentration was determined for Ad5.βgal.ΔF/F+ by a 50% tissue culture infective dose assay on 633 cells, and the VP/50% tissue culture infective dose ratio was 60.

Transient transfection assays.

For plasmid transfection, 5 × 105 293T cells were seeded per well in a six-well plate. Cells were transfected the next day with 2 μg of plasmid per well, using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Seventy-two hours after transfection, cells were lysed in 100 μl radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer for immunoblot analysis.

Adenoviral gene transfer assays.

Cells were seeded in 48-well plates at a concentration of 1.5 × 104 cells (HUVEC) or 2 × 104 cells (NHK, NHF, and melanoma cells) in 0.5 ml of medium per well and grown overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. The following day, the medium was removed from cell monolayers, and the cells were transduced in triplicate with adenoviruses in 0.1 ml medium containing 2% FCS. After 4 h, 0.5 ml of growth medium was added. For peptide blocking experiments, cells were incubated for 30 min on ice with 2 mg/ml GRGDS or GRGES peptide (EMC Microcollections, Tübingen, Germany) in medium containing 2% FCS or with medium only. Subsequently, viruses were added in triplicate in 50 μl of medium containing 2% FCS. After incubation for 1.5 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, peptides and viruses were removed, cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline, and 0.5 ml of growth medium was added. Cells were harvested for β-Gal assay at 2 days postinfection. All experiments were repeated at least once and gave similar results. Data for representative experiments are shown.

Immunoblotting.

Cell lysates with 30 μg of protein, boiled or unboiled, or 8 × 108 VP of CsCl-purified virus (boiled) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in 10% gels and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher und Schuell, Dassel, Germany). Membranes were probed with a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for monomeric or trimeric fibers (clone 4D2, which binds to the Ad5 fiber tail; Biomeda, Eching, Germany). As a loading control, membranes were probed with a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for β-actin (for cell lysates) (clone AC-74; Sigma) or a rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for hexon (for viruses) (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Bound antibodies were detected with a secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Promega, Madison, WI) and enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany).

β-Gal assay.

β-Galactosidase activity after virus transduction was quantified using a Tropix Galacto Light Plus chemiluminescent reporter gene assay system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and were subsequently lysed in 100 μl lysis solution. Twenty microliters of lysate and 70 μl of substrate buffer were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After the addition of 100 μl of accelerator solution, samples were applied for quantification of luminescence in a Victor 1420 multilabel counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland).

RESULTS

Generation of recombinant fiber expression plasmids.

Towards our goal, the definition of insertion sites for peptide ligands in the Ad41s fiber knob that facilitate adenovirus tropism modification, we generated expression plasmids for modified fibers as outlined in Fig. 1. In consideration of sequence comparisons between the short fiber knob domain of Ad41 and the knob domains of Ad5 and other serotypes and of hydrophobicity and surface probability analyses, we decided to investigate peptide insertions into the AB, DE, EG (note that there is no F β-strand in the Ad41 short fiber knob), HI, and IJ loops. In addition, we sought to analyze C-terminal peptide fusions with an eight-amino-acid linker (CL) or a 16-amino-acid long linker (CLL). We chose to use the integrin-binding CDCRGDCFC peptide as a model ligand for our purpose because this peptide has successfully been incorporated internally (HI loop) and C-terminally into the Ad5 fiber knob domain (14, 46). Moreover, this peptide allows for analysis of the resulting fiber-modified adenoviruses in a wide panel of cell types. All F5/41s fiber constructs contained the tail domain of the Ad5 fiber (amino acids 1 to 46) fused to the shaft (starting from amino acid 45) and modified knob domain of the Ad41 short fiber. To investigate effects of the tail domain on fiber incorporation into virus particles, we also generated a fiber construct that matched F5/41sCLL-RGD but contained the tail domain of the Ad41 short fiber (F41sCLL-RGD). Fiber expression plasmids (pF) were cloned to contain the cytomegalovirus promoter, exons 1 to 3 and intron 1 of the Ad5 tripartite leader, and the recombinant fiber cDNA (see Materials and Methods for detailed cloning procedures).

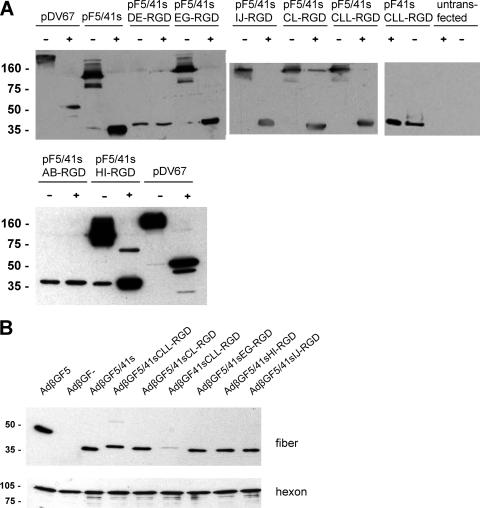

Analysis of trimerization of recombinant fiber molecules containing the Ad41s fiber knob with RGD peptide insertions.

For examination of recombinant fiber expression and trimerization, pF plasmids were transfected into 293T cells. Both untransfected cells and cells transfected with plasmid pDV67, which encodes the Ad5 fiber (45), were included as controls. At 3 days posttransfection, cell lysates, boiled or unboiled, were analyzed by immunoblot analysis with mouse monoclonal antibody clone 4D2, which binds to the Ad5 fiber tail (Fig. 2A). For various adenovirus fibers, it has been shown that trimers are not dissolved in SDS-polyacrylamide if protein samples are not boiled. Our results showed that fiber constructs with the RGD peptide inserted into the EG, HI, or IJ loop or fused to the C terminus of the Ad41s fiber knob were expressed and retained their capacity for trimerization. Fibers with the RGD peptide inserted into the AB or DE loop were not able to trimerize and also were expressed at lower concentrations. The anti-Ad5 fiber tail antibody we used bound to the monomer of recombinant F41sCLL-RGD. However, for this construct, we were unable to detect the trimeric version in unboiled lysates.

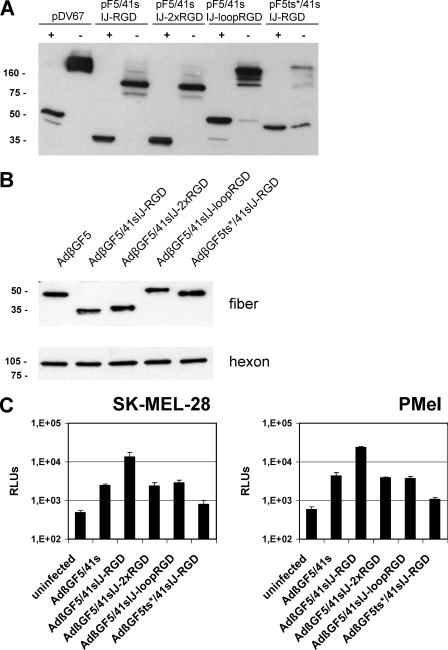

FIG. 2.

Trimerization of recombinant Ad41s fibers and incorporation into virus particles. (A) 293T cells were transfected with the indicated expression plasmids. Cells were lysed at 72 h posttransfection and were analyzed for recombinant fiber expression and trimerization by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting using monoclonal antibody clone 4D2, which binds to the Ad5 fiber tail. Lysates with 30 μg of protein were boiled (+) or not boiled (−) before being loaded in order to reveal fiber trimerization. Plasmid pDV67 encodes the Ad5 fiber. As a loading control, membranes were probed with a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for human β-actin (not shown). (B) Purified adenoviruses (8 × 108 VP) were boiled and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting with antibody 4D2 (upper panel) or with an anti-hexon antibody (lower panel) as a loading control. AdβGF5 contains the Ad5 fiber; AdβGF− is fiberless. Numbers indicate molecular masses in kDa. The calculated molecular mass of the F5/41s recombinant fiber monomer is 42 kDa.

Analysis of incorporation of recombinant fiber molecules containing the Ad41s fiber knob with the RGD peptide into virus particles.

To assess the incorporation of recombinant fiber molecules into virus particles and to investigate viral transduction mediated by the modified fibers, we generated adenoviruses with the β-Gal reporter gene by a transient transfection/infection protocol. Therefore, 293T cells were transfected with pF expression plasmids or with pDV67, using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). pF expression plasmids for fiber constructs that showed trimerization after plasmid transfection and pF41sCLL-RGD were used. At 1 day posttransfection, cells were infected with 1,000 VP/cell of Ad5.βgal.ΔF/F+. Ad5.βgal.ΔF is an E1-, E3-, and fiber gene-deleted adenovirus vector that contains a β-Gal reporter cassette in the E1 region (44). Ad5.βgal.ΔF/F+ was produced in the E1- and fiber-complementing cell line 633 (45) and thus contained a capsid with Ad5 fiber molecules. Adenoviruses, which potentially incorporated the expression plasmid-encoded modified fiber, were harvested at 2 days postinfection. The resulting viruses were AdβGF5/41sEG-RGD, AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD, and AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD, with internal RGD insertions into the F5/41s fiber; AdβGF5/41sCL-RGD, AdβGF5/41sCLL-RGD, and AdβGF41sCLL-RGD, with C-terminal fusions of the RGD peptide to the F5/41s or F41s fiber; AdβGF5/41s, without peptide insertion into the F5/41s fiber; AdβGF5, with the Ad5 fiber (transfection of pDV67); and fiberless AdβGF− (mock transfection). The incorporation of fiber molecules into virus particles and, thus, trimerization were analyzed by Western blot analysis of purified virus particles (Fig. 2B). We observed the incorporation of all recombinant fiber molecules for which trimerization was shown after plasmid transfection, with similar efficiency. Interestingly, we detected a weak band for the fiber with the Ad41s fiber tail, indicating that this fiber can trimerize and thus be incorporated into Ad5 particles, but with a low efficiency. The same results were obtained with a second set of virus preparations that were generated with a different transient transfection/infection protocol using Nanofectin (PAA) instead of Lipofectamine (not shown). However, this method resulted in lower virus titers that required quantification by real-time PCR.

We concluded from our data that insertion of the CDCRGDCFC peptide into the EG, HI, or IJ loop of the Ad41s fiber knob or fusion of this peptide via differently sized linkers to the knob C terminus is feasible without a loss of the fibers' capacity for trimerization and incorporation into virus particles. Furthermore, fiber molecules with the Ad41s fiber tail were incorporated into Ad5 particles, but with a low efficiency. In contrast, peptide insertion into the AB or DE loop of the Ad41s fiber knob was detrimental to fiber trimerization.

Transduction efficacies of adenoviruses containing Ad41s fiber-derived molecules with RGD peptide insertions in the knob domain.

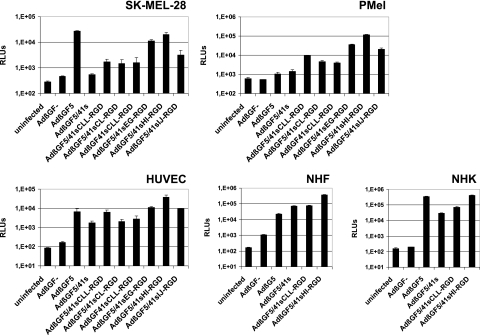

To determine adenovirus tropism modification by the various peptide insertion strategies, we next analyzed the gene transfer efficacies of adenoviruses with modified fibers by means of a β-Gal assay 2 days after virus transduction. Established (SK-MEL-28) or primary (PMel) melanoma cells, primary fibroblasts (NHF), primary keratinocytes (NHK), and primary endothelial cells (HUVEC) were transduced with adenoviruses AdβGF5/41sEG-RGD, AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD, AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD, AdβGF5/41sCL-RGD, AdβGF5/41sCLL-RGD, and AdβGF41sCLL-RGD or with control viruses AdβGF5/41s, AdβGF5, and AdβGF−. Our data (Fig. 3) revealed the highest gene transfer efficiencies for viruses with internal insertion of the RGD peptide into the Ad41s fiber knob. The virus with the HI loop insertion always gave the highest readings. In CAR-negative PMel cells, transduction by these viruses was enhanced by 1 to 2 orders of magnitude relative to that by both AdβGF5/41 and AdβGF5 (AdβGF5/41sEG-RGD, 25.7-fold and 34.0-fold, respectively; AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD, 83.7-fold and 110.9-fold, respectively; and AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD, 14.2-fold and 18.8-fold, respectively). CAR-positive SK-MEL-28 cells showed the highest reporter activity after transduction with AdβGF5, but readings for AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD were only minimally lower (1.4-fold). In these cells, transduction efficiencies of AdβGF5/41sEG-RGD, AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD, and AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD were 20.5-fold, 36.2-fold, and 5.9-fold higher than that of AdβGF5/41s. In normal cells, transduction by AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD was superior (HUVEC and NHF) or similar (NHK) to that by AdβGF5. Adenoviruses with C-terminal fusion of the RGD peptide caused better transduction in melanoma cells than did AdβGF5/41s but had lower transduction efficiencies than viruses with internal RGD peptide insertions. In SK-MEL-28 cells, transduction by AdβGF5/41sCL-RGD, AdβGF5/41sCLL-RGD, and AdβGF41sCLL-RGD resulted in similar β-Gal activities, whereas AdβGF5/41sCLL-RGD was superior to AdβGF5/41sCL-RGD and AdβGF41sCLL-RGD in PMel cells and HUVEC. In HUVEC and NHK, but not in NHF, transduction by AdβGF5/41sCLL-RGD was more efficient than that by AdβGF5/41s. However, whereas AdβGF5/41s mediated minimal gene transfer into melanoma cells, considerable transduction of normal cells was observed (1 to 2 orders of magnitude more than that by AdβGF−). In fibroblasts, AdβGF5/41s was even more efficient than AdβGF5.

FIG. 3.

Transduction of established and primary melanoma cells and of normal cells with fiber-modified adenoviruses. A human melanoma cell line (SK-MEL-28), primary human melanoma cells (PMel), primary human endothelial cells (HUVEC), primary normal human fibroblasts (NHF), and primary normal human keratinocytes (NHK) were transduced with the indicated viruses at 104 (HUVEC), 2.5 × 104 (NHF and NHK), 5 × 104 (SK-MEL-28 cells), or 105 (PMel cells) VP/cell in triplicate. At 2 days postinfection, cells were lysed, and β-galactosidase activities of the lysates were determined with a luminescence assay. Columns show mean RLU values; error bars show standard deviations. Uninfected cells were analyzed to show the background activity of β-galactosidase.

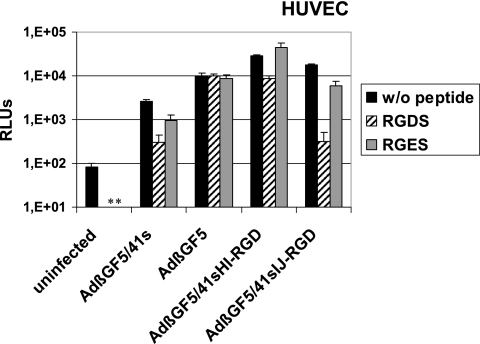

For AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD and AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD, representing highly efficient tropism-modified viruses with an RGD peptide insertion into either the side (HI) or top (IJ) of the Ad41s fiber knob, we next performed competition experiments with soluble RGD peptide to further investigate the contribution of the RGD peptide to virus transduction. Therefore, we preincubated HUVEC with 2 mg/ml GRGDS peptide before infection with AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD, AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD, or control viruses AdβGF5/41s and AdβGF5. As further controls, cells were preincubated with 2 mg/ml GRGES or with medium without peptide. The resulting β-Gal activities (Fig. 4) demonstrated that transduction of HUVEC by AdβGF5 could not be inhibited by preincubation with the GRGDS peptide. In contrast, transduction by AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD, AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD, and AdβGF5/41s was inhibited by GRGDS. No or significantly less inhibition was observed after GRGES preincubation. For AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD and AdβGF5/41s, inhibition of gene transfer by GRGDS preincubation was 55.6-fold and 8.8-fold, respectively, resulting in similarly low-level transduction (about 300 relative light units [RLUs], compared to 80 RLUs for uninfected cells). Inhibition of transduction by GRGDS was significant but less drastic for AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD (3.6-fold). The results of peptide inhibition experiments with NHF cells (not shown) were very similar to the data shown in Fig. 4, but in these experiments the cells had to be handled very carefully due to cell detachment after preincubation with the GRGDS peptide. We were unable to perform competition experiments with melanoma cells or NHK because these cells detached easily after preincubation with the GRGDS peptide.

FIG. 4.

Competition of transduction by fiber-modified adenoviruses with soluble RGD peptide. HUVEC were preincubated with the indicated peptides at 2 mg/ml in medium or with medium alone at 4°C for 30 min and were subsequently infected with the indicated viruses at 105 VP/cell for 90 min in triplicate. β-Galactosidase activity was determined at 2 days postinfection. Columns show mean RLU values; error bars show standard deviations. Uninfected cells were analyzed to show the background activity of β-galactosidase. *, not determined.

The overall conclusion from these transduction data is that RGD peptide insertion into the EG, HI, or IJ loop or RGD peptide fusion via differently sized linkers to the C terminus of the Ad41 short fiber knob mediates tropism modification of adenovirus vectors, as determined for various cell types. The magnitude of infectivity enhancement by RGD peptide insertion varied depending on the insertion site. For further discussion of transduction and competition data, see below.

Fiber trimerization and adenovirus transduction by F5/41sIJ-RGD derivatives with a long fiber shaft, tandem copies of the peptide insert, or a longer peptide insert.

Next, we pursued strategies for further augmentation of F5/41sRGD fiber-mediated adenoviral cell entry. These strategies were (i) extension of the length of the fiber shaft, (ii) insertion of multiple copies of the peptide insert, or (iii) extension of the linker length on both sides of the RGD peptide. We hypothesized that these strategies would increase the accessibility and/or affinity of the peptide ligand in the fiber for its cellular receptor. With the third approach, we also sought to assess if the insertion of large inserts into Ad41s fiber knob loops is feasible. With these goals, we cloned three different pF expression plasmids encoding derivatives of the fiber construct F5/41sIJ-RGD (Fig. 5A and B). This modified fiber mediated a decent, but not yet optimal, gene transfer efficacy in the previous experiments. For strategy i, we replaced the Ad41s fiber shaft (12 repeat motifs) with the long shaft of the Ad5 fiber (22 repeat motifs) in which the KKTK motif was mutated, resulting in plasmid pF5ts*/41sIJ-RGD. We chose to mutate the putative HSPG-binding KKTK motif to exclude nonspecific, fiber shaft-mediated cell binding of the resulting virus (41). Strategy ii was investigated by inserting two copies of the CDCRGDCFC peptide in tandem, separated by a GS linker, into the IJ loop, generating pF5/41sIJ-2xRGD. Finally, for strategy iii, we inserted a sequence encoding 83 amino acids with a centered RGD peptide derived from the RGD-containing loop of the Ad5 penton base into the F5/41s IJ loop, generating pF5/41sIJ-loopRGD. By transient transfection of plasmids pF5ts*/41sIJ-RGD, pF5/41sIJ-2xRGD, and pF5/41sIJ-loopRGD, and as controls, the parental plasmids pF5/41sIJ-RGD and pDV67 and by immunoblot analysis, we could demonstrate trimerization of all three new recombinant fibers (Fig. 6A). For F5ts*/41sIJ-RGD, protein expression and trimerization were somewhat reduced compared to those for all other constructs. We then generated the three corresponding adenoviruses, AdβGF5ts*/41sIJ-RGD, AdβGF5/41sIJ-2xRGD, and AdβGF5/41sIJ-loopRGD, by the transfection/infection protocol. Incorporation of similar amounts of recombinant fibers into virus particles was shown by Western blotting (Fig. 6B). Note that the F5ts*/41sIJ-RGD fiber monomer (but not the trimer) (Fig. 6A) migrated faster than F5/41sIJ-loopRGD in the polyacrylamide gel, although the calculated molecular masses are 60 kDa and 50 kDa, respectively. Finally, we transduced SK-MEL-28 cells and PMel cells with viruses AdβGF5ts*/41sIJ-RGD, AdβGF5/41sIJ-2xRGD, and AdβGF5/41sIJ-loopRGD or with virus AdβGF5/41s or AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD as a control and determined β-Gal activities at 2 days postinfection (Fig. 6C). Surprisingly, in both cell types, β-Gal activities for AdβGF5/41sIJ-2xRGD and AdβGF5/41sIJ-loopRGD were not increased relative to those for AdβGF5/41s and were thus much weaker than those for AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD. Even lower RLUs were detected for AdβGF5ts*/41sIJ-RGD. Repeat experiments with a new set of virus preparations showed identical results. We concluded that the extension of shaft length, multiple copies of the peptide ligand, or extension of the linkers on both sites of the peptide ligand in the context of RGD peptide insertion into the IJ loop of F5/41s allowed for fiber trimerization and incorporation into virus but abolished peptide-dependent tropism modification. Therefore, these strategies are not generally suitable for enhancing (or even retaining) peptide-mediated adenovirus cell binding and entry.

FIG. 5.

Outline of pF5/41sIJ-RGD derivatives with two copies of the RGD peptide insert in tandem, an extended RGD-containing peptide insert, or a long fiber shaft. (A) Expression plasmid pF5ts*/41sIJ-RGD is based on a construct that encodes a recombinant fiber protein with the Ad5 fiber tail and shaft domains (amino acids 1 to 400; the asterisk indicates mutation of the potential HSPG-binding site of the shaft) fused to the Ad41 short fiber knob (starting with amino acid 233), resulting in the fusion site sequence DKLT/IWSI. (B) For plasmid pF5ts*/41sIJ-RGD, a CDCRGDCFC peptide with the indicated linkers (in italics) was inserted into the IJ loop of the Ad41s fiber knob (illustrated at the top). For pF5/41sIJ-2xRGD, two copies of the CDCRGDCFC peptide with the indicated spacer and linkers (in italics) were inserted into the IJ loop of the Ad41 short fiber knob. For pF5/41sIJ-loopRGD, an 83-amino-acid loop of the Ad5 penton base with a centered RGD motif and the indicated linkers (in italics) was inserted into the IJ loop of the Ad41s fiber knob.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of pF5/41sIJ-RGD derivatives with two copies of the RGD peptide insert in tandem, an extended RGD-containing peptide insert, or a long shaft. (A) Cell lysates of 293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were analyzed for recombinant fiber expression and trimerization by gel electrophoresis and Western blotting as described in the legend to Fig. 2A. (B) Purified adenoviruses (8 × 108 VP) generated with the transfection/infection technology were analyzed by gel electrophoresis and Western blotting for recombinant fiber incorporation as described in the legend to Fig. 2B. (C) SK-MEL-28 and PMel cells were transduced with the indicated adenoviruses at 105 VP/cell in triplicate. At 2 days postinfection, cells were lysed, and β-galactosidase activities of the lysates were determined with a luminescence assay. Columns show mean RLU values; error bars show standard deviations. Uninfected cells were analyzed to show the background activity of β-galactosidase.

DISCUSSION

With the present study, we establish the feasibility of peptide ligand insertions into the Ad41s fiber knob domain resulting in molecules that retain both fiber/capsid integrity and the potency of the inserted peptide to bind its cellular receptor. Our study represents, to the best of our knowledge, the first report on internal and functional ligand insertions into an adenovirus fiber other than the Ad5 fiber and into loops different from the HI loop. A previous effort for functional insertion of the CDCRGDCFC ligand into the HI loop of the adenovirus serotype 3 fiber (in the context of the long Ad5 shaft and tail domains) was unsuccessful (10), demonstrating structural constraints of adenovirus fiber molecules for internal peptide insertions. With our data, we could also demonstrate that functional insertion of a ligand into loops of short shafted adenovirus fibers is feasible.

The realization of selective adenovirus cell entry into target cells represents a critical step towards the implementation of adenoviral therapeutics in gene transfer, vaccination, and oncolysis. This goal requires the development, in parallel, of two modifications to the tropism of the most commonly used adenovirus serotype, i.e., serotype 5. First, cell entry into normal, nontargeted cells that express the Ad5 receptor CAR, most prominently hepatocytes, needs to be abolished. Second, targeting ligands need to be incorporated into the virus capsid without a loss of ligand function or deleterious effects to the virus structure. Recently, the replacement of the Ad5 fiber with the short fiber of subgroup F adenovirus Ad40 or Ad41 has been shown to achieve substantially reduced transduction of the liver and other organs after intravenous injection into mice and rats (25, 31). Therefore, the short fibers of Ad40 and Ad41 represent promising “detargeted” platforms for retargeting of adenovirus cell entry by insertion of peptide ligands.

Our study shows that peptide insertion into the EG, HI, or IJ loop, but not into the AB or DE loop, of the Ad41s fiber knob retains the fiber's essential properties of trimerization and incorporation into adenovirus capsids. Notably, these results demonstrate that it is possible to insert peptides into the Ad41s fiber knob in such a way that they face the top (IJ loop) or the side (EG and HI loops) of the fiber molecule (Fig. 1C). In this regard, it is important that adenoviruses can bind to their cellular receptors either via residues in the side (Ad5) (19) or via residues in the top (Ad37/Ad19p) (11) of their fiber molecules. The inability of F5/41s with a DE loop insertion to form trimers can be explained by direct steric hindrance of the inserted amino acids, because this loop is located at the interface of fiber monomers. Also, according to the crystal structure of the short Ad41 fiber knob (36), which was published after we designed and produced our constructs, the DE region contains an alpha-helix, not a flexible loop. In contrast, the AB loop is located on the fiber surface. The AB loop of the Ad5 fiber is involved in CAR binding but is structurally different in the Ad41s fiber knob (33, 36). We hypothesize that the insertion of peptides into the AB loop of the Ad41s fiber knob interferes with folding of the fiber monomer and thus, indirectly, with fiber trimerization. We found that C-terminal fusion of peptide ligands to the Ad41s fiber knob via differently sized linkers (8 or 16 amino acids) does not interfere with fiber trimerization. This result is in line with previous studies that show the feasibility of C-terminal extensions of the Ad5, Ad3, and Ad40s fiber knobs (25, 42, 46).

All of our recombinant fibers, with the exception of F41sCLL-RGD, contained the Ad5 fiber tail and the Ad41 short fiber shaft. Thereby, we sought to guarantee the incorporation of recombinant fibers into Ad5 capsids but also to retain a short-shafted fiber. To detect fiber molecules in Western blots, we used the monoclonal anti-fiber antibody clone 4D2 (16), which binds to a highly conserved N-terminal motif (17) of adenovirus fiber molecules that is also found in the Ad41 short fiber. Although we were unable to detect trimeric F41sCLL-RGD in Western blots of cell lysates after transient transfection, we observed a weak band for this fiber in Western blots of purified AdβGF41sCLL-RGD. Together with the transduction data for this virus, our results indicate that the F41sCLL-RGD fiber can trimerize and is incorporated into virus particles, but with less efficiency than fibers with the Ad5 fiber tail. These results were not expected in light of the sequence homology between the Ad41 short fiber and Ad5 fiber tail domains and considering our data that show no interference of the CLL-RGD fusion with trimerization of the F5/41s fiber. Moreover, previous reports showed the incorporation of a fiber chimera with Ad40s tail and shaft domains fused to the Ad5 knob into the Ad5 capsid (25) and more efficient incorporation of the Ad41 short fiber than the Ad41 long fiber into Ad5 particles (34). Our results argue for the conservation of the Ad5 fiber tail in pseudotyped, Ad5-derived adenoviruses.

The virus transduction experiments of our study demonstrate that tropism modification of Ad5 by insertion of a peptide ligand into short-shafted adenovirus fibers, in this case the F5/41s fiber, is feasible. This is important especially in consideration of the negative charge of Ad5 hexon molecules in the virus capsid and the potentially resulting repulsion from cell surfaces. In melanoma cells, all modified RGD-containing fibers that were incorporated into virus particles mediated enhanced adenovirus cell entry relative to that of the RGD-less control virus. In SK-MEL-28 cells, all viruses with C-terminal RGD showed similar transduction efficacies, and AdβGF5/41sCLL-RGD was superior to AdβGF5/41sCL-RGD and AdβGF41sCLL-RGD in primary melanoma cells and HUVEC. Different expression levels of different integrins might be responsible for these intercellular variations. Still, a long linker might be advantageous for C-terminally fused peptide ligands. The lower transduction efficiency for the virus with the Ad41s fiber tail might be explained by reduced fiber incorporation into Ad5 virions (as discussed above). Importantly, we show that internal insertion of RGD peptides into different loops of the Ad41s fiber knob results in transduction efficiencies that are superior to those of C-terminal RGD fusions. Either better peptide positioning or a superior peptide conformation (loop-like versus linear) might be responsible for these results. In this regard, it is important that (i) the C terminus of the Ad41s fiber, like the C terminus of the Ad5 fiber, points towards the virus capsid rather than to the outside (36); and (ii) the CDCRGDCFC peptide, which was originally selected from a cyclic peptide phage library (20), is not able to circularize per se in the reducing milieu of the cytoplasm and nucleoplasm where viruses are produced. However, the peptide might be forced into a circular conformation when incorporated into a loop of the Ad41s fiber knob. The highest transduction efficiencies in all cell types were obtained for the virus that contained the RGD peptide in the HI loop, followed by the virus with the EG loop insertion. Note that both loops are located on the side of the Ad41s fiber knob, indicating that this might be a favorable locale for insertion of targeting ligands.

The CDCRGDCFC peptide mediated adenovirus cell entry at any of the positions at the tip of the EG, HI, or IJ loop or at the C terminus of the Ad41s fiber. However, our transduction results with AdβGF5/41s-2xRGD and AdβGF5/41s-loopRGD clearly show that the precise peptide position within a loop is critical for its ability for tropism modification. Even a slight change of the RGD peptide position in the IJ loop, as represented by AdβGF5/41sIJ-2xRGD, ablates its ability to redirect adenovirus transduction. Also, AdβGF5/41sIJ-loopRGD did not show an enhanced transduction efficacy compared to AdβGF5/41s. For this virus, in addition to the length of the whole insert, the amino acids that directly flank the RGD peptide are different from the CDCRGDCFC peptide insert in AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD. However, this loop insert mediated efficient cell entry when inserted into the HI loop of the Ad5 fiber (8). Our transduction results for AdβGF5ts*/41sIJ-RGD indicate that the mutant long fiber shaft of Ad5 is not compatible with adenovirus tropism modification by ligand peptide insertion into the Ad41s fiber knob, at least for peptide insertions into the IJ loop. The rationale for developing this construct was to improve virus transduction by extending the distance between the peptide ligand and the virus surface. By this means, we sought to reduce potentially harmful repulsive effects resulting from the negative charge of the Ad5 fiber capsid. In light of our results for the long fiber shaft virus, it is even more important that peptide-mediated adenoviral transduction in the context of the short Ad41 fiber shaft is feasible. From our data, we conclude that the length and structure of the fiber shaft critically influence the ability of peptide ligands inserted into the fiber knob to interact with their cellular receptors. Interestingly, a recent publication indicates that mutation of the KKTK motif reduces transduction efficacy mediated by a ligand inserted into the HI loop of an Ad5 fiber (7). Further investigations are warranted to clarify the influence of the KKTK mutation on both virus detargeting and ligand-mediated retargeting of viruses with the Ad41s fiber knob.

To show peptide-mediated cell binding and entry of tropism-modified adenoviruses, competition experiments with soluble peptide are frequently performed. However, such experiments for RGD-modified viruses are complicated by the fact that RGD peptides can also interfere with binding of the Ad5 penton base to cellular integrins via its RGD motif. This interaction is required for internalization of cell-bound Ad5 particles. We previously reported that preincubation of HUVEC with circularized CDCRGDCFC peptide inhibits transduction by adenoviruses containing the Ad5 capsid (26). In the present study, the transduction of HUVEC by AdβGF5 was not inhibited by the GRGDS peptide. This result suggests that the interaction with integrins is weaker for this peptide than for the circular peptide and thus insufficient to block virus internalization in the context of the Ad5 fiber-CAR interaction. Interestingly, we observed reduced transduction of HUVEC by AdF5/41s after preincubation of the cells with the GRGDS peptide. We concluded that transduction by this virus was at least partially dependent on the penton-integrin interaction. Similar results were reported for viruses with the Ad40s fiber (25). In this case, transduction of primary hepatocytes was inhibited by preincubation of cells with a recombinant penton base. Note that penton bases of subgroup F adenoviruses Ad40 and Ad41 do not contain the RGD motif. After GRGDS peptide preincubation, HUVEC transduction by AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD was reduced to a level similar to that by AdβGF5/41s, demonstrating that transduction was completely RGD dependent. Transduction of HUVEC by AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD was also significantly reduced by GRGDS preincubation. However, this inhibition was less dramatic than that for AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD. This result could be explained by partially RGD-independent transduction. However, we suggest that the interaction between the HI-RGD and cellular integrins is stronger than that for the IJ insertion site and cannot be completely inhibited by the linear GRGDS peptide. Other groups have reported quantitatively similar or even less inhibition of RGD-modified Ad5 viruses by RGD peptides or penton base protein (9, 14). Moreover, our result that AdβGF5/41sHI-RGD showed a higher transduction efficacy than AdβGF5/41sIJ-RGD, while incorporating a similar quantity of fiber molecules, is also supportive of this hypothesis.

Our observation that primary normal cells were readily transduced by AdβGF5/41s without peptide ligand insertion is a novel and striking finding. Previous reports demonstrated strongly reduced transduction of healthy organs in vivo and of rat hepatocytes, rat endothelial cells, or primary human hepatocytes in vitro for Ad5-derived viruses with the Ad41s or Ad40s shaft and knob relative to that of viruses with the Ad5 fiber (25, 31). To date, a receptor for the Ad41s fiber has not been described. Because the transduction of HUVEC by AdβGF5/41s was RGD dependent, we hypothesize that cell entry of Ad5/41s is mediated, at least in part, by binding of the penton base via its RGD motif to cellular integrins. Thus, unwanted transduction by Ad5-derived viruses with the Ad41s fiber shaft and knob might be abolished by additional mutation of the penton base RGD motif.

In summary, we identified functional insertion sites for peptide ligands in the short-shafted Ad41 fiber knob. Internal insertion into both the top and side surfaces of the knob domain was feasible, mediated enhanced adenoviral transduction, and was superior to C-terminal peptide fusion, as shown with the CDCRGDCFC peptide. Hence, we (i) established that peptides inserted into a short-shafted fiber can mediate cell binding and (ii) defined sites for genetic insertion of targeting peptides into the Ad41s fiber knob. We suggest recombinant fibers with Ad41s fiber shaft and knob domains and peptide insertions in the EG, HI, or IJ loop as a novel platform for genetic targeting of adenovirus cell entry. This platform can now be exploited for the insertion of targeting peptides derived, for example, by various display technologies. Furthermore, we report that the precise positioning of a peptide ligand in the knob domain and also the position of the modified knob in the virus capsid, i.e., the length and structure of the fiber shaft, are critical determinants for the receptor binding capacity of the ligand peptide. Therefore, our results open new avenues for the future development of improved recombinant adenoviruses for therapeutic gene transfer, genetic vaccination, and viral oncolysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG (NE 832/3 and SFB 643; Teilprojekt A5), the Deutsche Krebshilfe e.V. (grant 10-2186-Ne 1), the Wilhelm Sander Stiftung (grant 2003.118.1), and the Helmholtz Gemeinschaft (Helmholtz-University Group grant) to D.M.N.

Adenovirus Ad5.βgal.ΔF was kindly provided by AdVec Inc., Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, and G. Nemerow of the Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, and Ad41 was provided by J. Chroboczek, Institut de Biologie Structurale Jean-Paul Ebel, Grenoble, France. We are grateful to G. Nemerow and D. Van Seggern, the Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, for providing plasmids pDV55 and pDV67 and 633 cells. We thank G. Fey, C. Garlichs, and M. Marschall, University of Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany, and L. Chow, T. Broker, and S. Banerjee, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, for providing cells. We thank A. Steinkasserer and G. Schuler for their constant support and for providing an inspiring work environment. We are grateful to T. Johnson, Heidelberg University Hospital, for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 December 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyama, M., S. Thorne, D. Kirn, P. W. Roelvink, D. A. Einfeld, C. R. King, and T. J. Wickham. 2004. Ablating CAR and integrin binding in adenovirus vectors reduces nontarget organ transduction and permits sustained bloodstream persistence following intraperitoneal administration. Mol. Ther. 9:218-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alemany, R., C. Balague, and D. T. Curiel. 2000. Replicative adenoviruses for cancer therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:723-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alemany, R., and D. T. Curiel. 2001. CAR-binding ablation does not change biodistribution and toxicity of adenoviral vectors. Gene Ther. 8:1347-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee, N. S., A. A. Rivera, M. Wang, L. T. Chow, T. R. Broker, D. T. Curiel, and D. M. Nettelbeck. 2004. Analyses of melanoma-targeted oncolytic adenoviruses with tyrosinase enhancer/promoter-driven E1A, E4, or both in submerged cells and organotypic cultures. Mol. Cancer Ther. 3:437-449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett, B. G., C. J. Crews, and J. T. Douglas. 2002. Targeted adenoviral vectors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1575:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basak, S. K., S. M. Kiertscher, A. Harui, and M. D. Roth. 2004. Modifying adenoviral vectors for use as gene-based cancer vaccines. Viral Immunol. 17:182-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayo-Puxan, N., M. Cascallo, A. Gros, M. Huch, C. Fillat, and R. Alemany. 2006. Role of the putative heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan-binding site of the adenovirus type 5 fiber shaft on liver detargeting and knob-mediated retargeting. J. Gen. Virol. 87:2487-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belousova, N., V. Krendelchtchikova, D. T. Curiel, and V. Krasnykh. 2002. Modulation of adenovirus vector tropism via incorporation of polypeptide ligands into the fiber protein. J. Virol. 76:8621-8631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biermann, V., C. Volpers, S. Hussmann, A. Stock, H. Kewes, G. Schiedner, A. Herrmann, and S. Kochanek. 2001. Targeting of high-capacity adenoviral vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 12:1757-1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borovjagin, A. V., A. Krendelchtchikov, N. Ramesh, D. C. Yu, J. T. Douglas, and D. T. Curiel. 2005. Complex mosaicism is a novel approach to infectivity enhancement of adenovirus type 5-based vectors. Cancer Gene Ther. 12:475-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burmeister, W. P., D. Guilligay, S. Cusack, G. Wadell, and N. Arnberg. 2004. Crystal structure of species D adenovirus fiber knobs and their sialic acid binding sites. J. Virol. 78:7727-7736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cattaneo, A., and S. Biocca. 1999. The selection of intracellular antibodies. Trends Biotechnol. 17:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeLano, W. L. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA.

- 14.Dmitriev, I., V. Krasnykh, C. R. Miller, M. Wang, E. Kashentseva, G. Mikheeva, N. Belousova, and D. T. Curiel. 1998. An adenovirus vector with genetically modified fibers demonstrates expanded tropism via utilization of a coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor-independent cell entry mechanism. J. Virol. 72:9706-9713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Einfeld, D. A., R. Schroeder, P. W. Roelvink, A. Lizonova, C. R. King, I. Kovesdi, and T. J. Wickham. 2001. Reducing the native tropism of adenovirus vectors requires removal of both CAR and integrin interactions. J. Virol. 75:11284-11291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong, J. S., and J. A. Engler. 1991. The amino terminus of the adenovirus fiber protein encodes the nuclear localization signal. Virology 185:758-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong, S. S., and P. Boulanger. 1995. Protein ligands of the human adenovirus type 2 outer capsid identified by biopanning of a phage-displayed peptide library on separate domains of wild-type and mutant penton capsomers. EMBO J. 14:4714-4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakubczak, J. L., M. L. Rollence, D. A. Stewart, J. D. Jafari, D. J. Von Seggern, G. R. Nemerow, S. C. Stevenson, and P. L. Hallenbeck. 2001. Adenovirus type 5 viral particles pseudotyped with mutagenized fiber proteins show diminished infectivity of coxsackie B-adenovirus receptor-bearing cells. J. Virol. 75:2972-2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirby, I., E. Davison, A. J. Beavil, C. P. Soh, T. J. Wickham, P. W. Roelvink, I. Kovesdi, B. J. Sutton, and G. Santis. 2000. Identification of contact residues and definition of the CAR-binding site of adenovirus type 5 fiber protein. J. Virol. 74:2804-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koivunen, E., B. Wang, and E. Ruoslahti. 1995. Phage libraries displaying cyclic peptides with different ring sizes: ligand specificities of the RGD-directed integrins. Biotechnology (New York) 13:265-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koizumi, N., H. Mizuguchi, F. Sakurai, T. Yamaguchi, Y. Watanabe, and T. Hayakawa. 2003. Reduction of natural adenovirus tropism to mouse liver by fiber-shaft exchange in combination with both CAR- and αv integrin-binding ablation. J. Virol. 77:13062-13072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leissner, P., V. Legrand, Y. Schlesinger, D. A. Hadji, M. van Raaij, S. Cusack, A. Pavirani, and M. Mehtali. 2001. Influence of adenoviral fiber mutations on viral encapsidation, infectivity and in vivo tropism. Gene Ther. 8:49-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin, K., A. Brie, P. Saulnier, M. Perricaudet, P. Yeh, and E. Vigne. 2003. Simultaneous CAR- and alpha V integrin-binding ablation fails to reduce Ad5 liver tropism. Mol. Ther. 8:485-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McConnell, M. J., and M. J. Imperiale. 2004. Biology of adenovirus and its use as a vector for gene therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 15:1022-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura, T., K. Sato, and H. Hamada. 2003. Reduction of natural adenovirus tropism to the liver by both ablation of fiber-coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor interaction and use of replaceable short fiber. J. Virol. 77:2512-2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nettelbeck, D. M., D. W. Miller, V. Jerome, M. Zuzarte, S. J. Watkins, R. E. Hawkins, R. Muller, and R. E. Kontermann. 2001. Targeting of adenovirus to endothelial cells by a bispecific single-chain diabody directed against the adenovirus fiber knob domain and human endoglin (CD105). Mol. Ther. 3:882-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nettelbeck, D. M., A. A. Rivera, C. Balague, R. Alemany, and D. T. Curiel. 2002. Novel oncolytic adenoviruses targeted to melanoma: specific viral replication and cytolysis by expression of E1A mutants from the tyrosinase enhancer/promoter. Cancer Res. 62:4663-4670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nettelbeck, D. M., A. A. Rivera, J. Kupsch, D. Dieckmann, J. T. Douglas, R. E. Kontermann, R. Alemany, and D. T. Curiel. 2004. Retargeting of adenoviral infection to melanoma: combining genetic ablation of native tropism with a recombinant bispecific single-chain diabody (scDb) adapter that binds to fiber knob and HMWMAA. Int. J. Cancer 108:136-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicklin, S. A., D. J. Von Seggern, L. M. Work, D. C. Pek, A. F. Dominiczak, G. R. Nemerow, and A. H. Baker. 2001. Ablating adenovirus type 5 fiber-CAR binding and HI loop insertion of the SIGYPLP peptide generate an endothelial cell-selective adenovirus. Mol. Ther. 4:534-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicklin, S. A., E. Wu, G. R. Nemerow, and A. H. Baker. 2005. The influence of adenovirus fiber structure and function on vector development for gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 12:384-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicol, C. G., D. Graham, W. H. Miller, S. J. White, T. A. Smith, S. A. Nicklin, S. C. Stevenson, and A. H. Baker. 2004. Effect of adenovirus serotype 5 fiber and penton modifications on in vivo tropism in rats. Mol. Ther. 10:344-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rivera, A. A., J. Davydova, S. Schierer, M. Wang, V. Krasnykh, M. Yamamoto, D. T. Curiel, and D. M. Nettelbeck. 2004. Combining high selectivity of replication with fiber chimerism for effective adenoviral oncolysis of CAR-negative melanoma cells. Gene Ther. 11:1694-1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roelvink, P. W., G. Mi Lee, D. A. Einfeld, I. Kovesdi, and T. J. Wickham. 1999. Identification of a conserved receptor-binding site on the fiber proteins of CAR-recognizing adenoviridae. Science 286:1568-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoggins, J. W., J. G. Gall, and E. Falck-Pedersen. 2003. Subgroup B and F fiber chimeras eliminate normal adenovirus type 5 vector transduction in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 77:1039-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoggins, J. W., M. Nociari, N. Philpott, and E. Falck-Pedersen. 2005. Influence of fiber detargeting on adenovirus-mediated innate and adaptive immune activation. J. Virol. 79:11627-11637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seiradake, E., and S. Cusack. 2005. Crystal structure of enteric adenovirus serotype 41 short fiber head. J. Virol. 79:14088-14094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shayakhmetov, D. M., A. M. Eberly, Z. Y. Li, and A. Lieber. 2005. Deletion of penton RGD motifs affects the efficiency of both the internalization and the endosome escape of viral particles containing adenovirus serotype 5 or 35 fiber knobs. J. Virol. 79:1053-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shayakhmetov, D. M., A. Gaggar, S. Ni, Z. Y. Li, and A. Lieber. 2005. Adenovirus binding to blood factors results in liver cell infection and hepatotoxicity. J. Virol. 79:7478-7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith, T., N. Idamakanti, H. Kylefjord, M. Rollence, L. King, M. Kaloss, M. Kaleko, and S. C. Stevenson. 2002. In vivo hepatic adenoviral gene delivery occurs independently of the coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor. Mol. Ther. 5:770-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith, T. A., N. Idamakanti, J. Marshall-Neff, M. L. Rollence, P. Wright, M. Kaloss, L. King, C. Mech, L. Dinges, W. O. Iverson, A. D. Sherer, J. E. Markovits, R. M. Lyons, M. Kaleko, and S. C. Stevenson. 2003. Receptor interactions involved in adenoviral-mediated gene delivery after systemic administration in non-human primates. Hum. Gene Ther. 14:1595-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith, T. A., N. Idamakanti, M. L. Rollence, J. Marshall-Neff, J. Kim, K. Mulgrew, G. R. Nemerow, M. Kaleko, and S. C. Stevenson. 2003. Adenovirus serotype 5 fiber shaft influences in vivo gene transfer in mice. Hum. Gene Ther. 14:777-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uil, T. G., T. Seki, I. Dmitriev, E. Kashentseva, J. T. Douglas, M. G. Rots, J. M. Middeldorp, and D. T. Curiel. 2003. Generation of an adenoviral vector containing an addition of a heterologous ligand to the serotype 3 fiber knob. Cancer Gene Ther. 10:121-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volk, A. L., A. A. Rivera, A. Kanerva, G. Bauerschmitz, I. Dmitriev, D. M. Nettelbeck, and D. T. Curiel. 2003. Enhanced adenovirus infection of melanoma cells by fiber-modification: incorporation of RGD peptide or Ad5/3 chimerism. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2:511-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Von Seggern, D. J., C. Y. Chiu, S. K. Fleck, P. L. Stewart, and G. R. Nemerow. 1999. A helper-independent adenovirus vector with E1, E3, and fiber deleted: structure and infectivity of fiberless particles. J. Virol. 73:1601-1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Von Seggern, D. J., S. Huang, S. K. Fleck, S. C. Stevenson, and G. R. Nemerow. 2000. Adenovirus vector pseudotyping in fiber-expressing cell lines: improved transduction of Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B cells. J. Virol. 74:354-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wickham, T. J., E. Tzeng, L. N. Shears, P. W. Roelvink, Y. Li, G. M. Lee, D. E. Brough, A. Lizonova, and I. Kovesdi. 1997. Increased in vitro and in vivo gene transfer by adenovirus vectors containing chimeric fiber proteins. J. Virol. 71:8221-8229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu, E., L. Pache, D. J. Von Seggern, T. M. Mullen, Y. Mikyas, P. L. Stewart, and G. R. Nemerow. 2003. Flexibility of the adenovirus fiber is required for efficient receptor interaction. J. Virol. 77:7225-7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, W. W. 1999. Development and application of adenoviral vectors for gene therapy of cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 6:113-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]