Abstract

Young people in their teens constitute the largest age group in the world, in a special stage recognized across the globe as the link in the life cycle between childhood and adulthood. Longitudinal studies in both developed and developing countries and better measurements of adolescent behavior are producing new insights. The physical and psychosocial changes that occur during puberty make manifest generational and early-childhood risks to development, in the form of individual differences in aspects such as growth, educational attainment, self-esteem, peer influences, and closeness to family. They also anticipate threats to adult health and well-being. Multidisciplinary approaches, especially links between the biological and the social sciences, as well as studies of socioeconomic and cultural diversity and determinants of positive outcomes, are needed to advance knowledge about this stage of development.

Young people aged 10 to 19 currently constitute a demographic bulge. They are the largest age group in the world, making up close to 20% of the 6.5 billion world population estimated in 2005 (1), 85% of whom live in developing countries and account for about one-third of those countries' national populations. Adolescence has also been described as “demographically dense”: a period in life during which a large percentage of people experience a large percentage of key life-course events (2). These include leaving or completing school, bearing a child, and becoming economically productive. They also include experiences, more common in this age group than in others, that are capable of substantially altering life trajectories: nonconsensual sex, alcohol and drug abuse, self-harm and interpersonal violence, and getting into trouble with the law. Diet and activity patterns, friendships, educational achievement, and civic involvement all affect current health, schooling, and family life, but they also have long-term effects on well-being in adulthood and even on future generations.

Adolescence was long thought to be an American cultural invention, a by-product of industrialization; a personally and socially problematic period created by the dependence of young people on their parents after leaving school and waiting to find work (3). However, investigations of hundreds of societies confirm that adolescence is a universally recognized life stage, starting around or just after puberty, although with different markers, behavioral manifestations, and social attributions (4-7). In most societies, the onset of adolescence is celebrated through rituals associated with prospective adult roles, such as reproduction, responsibility, and work; or with religious ceremonies, often differentiated by gender. In highly industrialized societies, the rites of passage are less public and more variable, but the period between childhood and adulthood may be bridged by changes in schooling, changes in family rules about autonomy, “first-time” experiences such as drinking alcohol, or inauguration into a group (8, 9).

After the publication in 1904 of a widely influential book by Hall (10), there was a pervasively held opinion that the “raging hormones” of puberty inevitably led to rebellion, conflict with parents and other authorities, etc. This simplistic idea has been shown to be false (9). Most adolescents don't go through a period of “sturm und drang.” Rather, the period of transition to adulthood—largely a socially designated period, with an onset that is generally precipitated by apparent physical changes associated with puberty—involves multiple interactions between biology and culture (or the set of social institutions and relationships prevalent at the time). Unidirectional models that assume that hormones cause behavior (for example, that testosterone causes aggression) or that behaviors cause hormone change (for example, that stress increases cortisol levels) have given way to models of hormone/behavior interactions and theories that take context into account (10). For example, poor attachment, family discord, and low investment in children are believed to affect the timing of puberty onset (11). In turn, the combination of these stressors and early puberty contributes to conflict with parents (12), lower self-esteem (13), and associations with deviant peers (14). Neurophysiological and brain imaging studies have demonstrated brain reorganization during adolescence coincident with the onset of puberty, which may make adolescents more sensitive to experiences that affect their judgement (15).

New Designs, New Methods

Time is an important dimension in understanding all developmental stages; at the individual level, in the interaction between individuals and changing sociocultural institutions and practices, and in unfolding historical events. In 1974, Glen Elder published Children of the Great Depression, a seminal work based on archival data from the 1920s (16). His analysis demonstrated how the growing independence of adolescent boys from their families cushioned the blow of economic shocks on their households. Other longitudinal studies, such as the 1946 British National Birth Cohort Follow-Up Study (17), the 1956 New York Longitudinal Study (18), and the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health in the USA (www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth) (2), have similarly shown the value of a life-course approach to understanding the development of young people.

Costly as they are to maintain and complex as the data are to analyze, prospective longitudinal designs are ideally suited to studying human development, especially for understanding processes of change and the temporal ordering of events that are used as one proxy of causality. Follow-up of young people across their life span, as they interact with family, school, peers, and the wider social world, enables understanding that goes much deeper than the snapshot provided by measurement at a single point in time. There are now several large-scale birth cohort studies in developing countries, including Brazil and South Africa, revealing information about long-term and generational effects of nutrition and family life, considered against the backdrop of the demographic and health transitions underway in these countries (19, 20).

The Birth to Twenty (Bt20) study in South Africa enrolled a cohort of more than 3000 children in Soweto-Johannesburg in early 1990. Nicknamed “Mandela's Children,” this study has collected data from before birth to age 15 (and the study is planned to continue to age 20) among the children (born immediately after Nelson Mandela's release from prison) and among their families. The second generation, children of the cohort, have started to be born, with the youngest mother only 14 years old when she delivered her baby. This group of young people is the first generation of children to live in a democratic South Africa, and the study aims to portray the development of individuals and groups of individuals as they make their life transitions across a particular historical period (21).

What Are We Learning?

A small group of children can be distinguished in the first 2 years of life whose adjustment difficulties, mainly in the form of problems relating to peers, persist for much of childhood. These problems are fairly well predicted by a combination of physiological (low birth weight), social (single parenthood), and economic (poverty) factors (22). Father absence is very high in southern Africa, largely because of migrant labor practices (23). Single-parent female-headed households are poorer than others; and men who are not married to the mother, either legally or traditionally, at the time of a child's birth, give progressively less financial support and time to their offspring as they grow older (24).

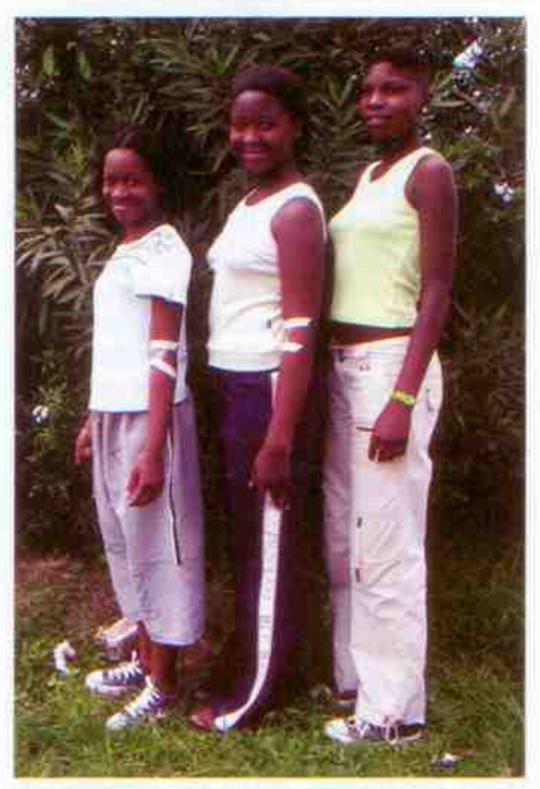

Marked differences occur between young people in all domains, most apparently in physical growth, both in childhood and adolescence (Fig. 1). However, it is not only individual differences that can be studied across time but also the patterns produced by the clustering of personal profiles, conditions, and contexts (25). Young people with different characteristics of physical growth or event onset such as puberty or sexual activity can be investigated with respect to the antecedents, consequences, and correlates of particular patterns. For example, children who show signs of rapid “catch-up” weight gain during infancy tend to have greater fat mass, poorer glucose tolerance, and increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in later life (26). Boys and girls in Bt20 who were in a more advanced stage of puberty at 13 years of age were more likely to be engaging in a variety of activities, such as smoking, experimenting with drugs, and sexual activity, than were their less developed peers.

Fig. 1.

Differences in growth and maturation between young women in Bt20, among young women living in the same city and born within 7 weeks of one another in 1990. (The young women and their caregivers gave consent for the photographs to appear in scholarly journals.)

Like other developmental stages, puberty has considerable individual variability. Pubertal staging is influenced by a number of generational, social, and biological factors. The age at which young people enter puberty has declined all over the world, largely as a result of improvements in socioeconomic conditions and nutrition (27). In South Africa, for example, menarche has decreased by 0.73 years per decade among girls in urban environments, with the last reported mean age being 13.2 years (28), still a whole year later than among African-American girls in the United States (29). At the same time, pubertal timing and related physical and psychosocial factors are also strong determinants of risks for adult outcomes, including poor sexual and reproductive health (30), social problems (31), and chronic diseases in later life (32). For example, early menarche is associated with initiation of sexual activity, both early and late puberty are coupled with changes in self-esteem among boys and girls, and weight gain among girls in puberty is related to later risk of hypertension and diabetes.

Accurate measurement of pubertal staging in community-based studies in non-Western societies, particularly Africa, has only recently become possible, with careful validation of self-assessment of hair growth and breast and gonad development against established criteria, such as Tanner's Sexual Maturation Scale (33). Relating pubertal staging to risk behaviors also requires that the latter be accurately assessed. Questions about behaviors that are unlawful or socially sanctioned (such as sex, drug use, and truancy) have the greatest potential to be underreported. New methods are becoming available to estimate these behaviors and correct these problems. These include the use of biological markers of behavior, such as the detection of salivary cotinine or thiocyanate to determine underreporting of smoking (34). Because cotinine, manufactured in the body, is a by-product of nicotine, cotinine measures are a good proxy for ingestion of or exposure to nicotine. Besides cotinine, we are also using urinary leukocyte esterase (ULE) tests in Bt20, in addition to the consistency of reports over time, as a screen for HIV risk and to estimate underreporting of sexual activity among young adolescents (35). ULE tests are more sensitive in females than males and require confirmatory microscopy. Furthermore, urinary tract infections can be acquired in ways other than through sexual intercourse. Nonetheless, at age 13 years, positive ULE tests were found in twice the number of girls who reported having been sexually active and in an additional 50% of girls who reported having had sex at 14 and 15 years of age. Positive ULE tests were associated with subsequent information indicating the likelihood of early sexual activity in 16% of adolescents at 13 years of age and in 21% at 14 who reported that they were not sexually active.

Also important are efforts to improve the accuracy of adolescent self-reports of potentially sensitive information. Recent technological developments have given rise to audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI). Adolescents read questions on the screen or listen to them through headphones in a language of their choice and enter their responses directly through a standard or modified keyboard. Studies in Bt20. Zimbabwe, and Kenya indicate that respondents prefer the privacy afforded, and some young people rate themselves as being more honest in their replies. User problems with the technology are still challenges, awaiting easier-to-use options before its application among adolescents with low levels of education can be expanded (36). Other experimental techniques include the presentation of and response to sensitive questions through personal digital assistants and mobile phones.

We are now entering a period where we can build on new capabilities for gathering data. Reliable and valid measurement, especially of data derived from young people's self-reports, is the essential foundation for rigorous evaluation of programs to improve conditions for optimal adolescent development. For the next 5 years of the Bt20 program, we are concentrating on measures of outcomes; achieving in school or dropping out, having an unwanted teenage pregnancy or completing school, weight gain, high diabetes indicators, conflict with the law, and so on. We are also starting to enroll the next generation—young Bt20 boys and girls are starting to have babies—and this gives us an excellent opportunity to study intergenerational advantages and disadvantages.

Bt20 and other longitudinal studies offer insights into predisposing conditions for beneficial and adverse outcomes in the adolescent years. Many of the findings of these studies emphasize the importance of early and systemic intervention. A good start in life, affectionate and stable family relationships, school and neighborhood support for young people's development, and the like, all predict good outcomes for young people in terms of school achievement, adjustment, civic engagement, and future aspirations. However, there are still reasons for optimism even when children are exposed to extremely dysfunctional circumstances (37, 38). For example, three decades ago, Garmezy and his colleagues found that although having a parent with schizophrenia did increase children's risk for the illness, 90% of the chidren they studied had “good peer relations, academic achievement, commitment to education and to purposive life goals, early and successful work histories” [(37), p. 114]. This is also true of conditions of poverty, conflict and violence, and parental substance abuse and criminality; most children exposed to these conditions grow up to lead successful lives as adults, with the capacity to love and work (38). Self-stabilizing tendencies enable many children and young people growing up in difficult circumstances to take advantage of even slender opportunities to participate in social activities with others, achieve at what they do and be valued, and contribute to the well-being of those they care about. Opportunity niches can be created by winning a race, being selected for a team or cast in a school play, or having a supportive family member even if not a parent, including a teacher who shows interest. All of these can change how a child sees him- or herself and how others see and treat him or her.

We have been surprised by the extent to which this is true in the Bt20 cohort. Of the 2300 children followed up to age 16, over 50% lived in very poor conditions (less than $1 per day per person), 20% frequently went to bed hungry during their early years, more than 40% had direct or vicarious experience of community or family violence, and only two out of five children had ever lived with their fathers (23). Despite these conditions, we currently estimate that only about 5% of the children showed persistent behavioral difficulties in their preschool and early school years, had started smoking or carrying a weapon by age 14, or been in conflict with the law. However, as young people enter into their teen years, travel further away from home to school, are subject to less parental monitoring and supervision, and are increasingly exposed to peers who engage in risky behavior behavior, the rates of potentially problematic behaviors increase. For example, although only 1.6% of 13-year-olds (3.3% of boys and 0.8% of girls) have had sexual intercourse, this rate rises to close to 20% at 15 years of age (27% among boys and 12% among girls). A composite risk score, combining rates of smoking, alcohol and drug use, foreplay, and weapon carrying, shows a significant increase with increased pubertal development and the transition from primary to secondary schooling. Young people most likely to be taking risks in their early teens are those who are advanced in their pubertal development for their age and in environments where they are exposed to older adolescents, without monitoring and supervision by caring adults.

Conclusion

The adolescent years, and especially puberty, link the impact of generational and early-childhood factors to adult outcomes. Longitudinal studies are demonstrating that it is also an age of opportunity: Good nutrition and healthy lifestyle, positive family and school influences, and access to supportive services, among other factors, can help young people break early patterns leading to ill health and poor social adjustment, with benefits for adult well-being and the next generation of children and youth. New methods are increasing the accuracy and validity of data collected from young people, and developments in both the biological and social sciences are providing unprecedented opportunities (39). However, we still know a lot more about what goes wrong in adolescence and why, and a lot less about how to prevent problems and how to get young people back on track, especially in those areas of the world in which young people face the greatest challenges. New knowledge is being driven by the need to develop and test interventions to promote the physical and psychological well-being of young people and counteract the risks associated with this developmental stage. This is especially true in a world in which many adolescents face the same threats—incomplete or poor-quality education, limited prospects for satisfying work, marginalization, HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections, substance abuse, violence, anxiety and depression—without the same opportunities for help and support.

References

- 1. See http://esa.un.org/unup/

- 2.Rindfuss R. Demography. 1991;28:493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kett J. Rites of Passage: Adolescence in America, 1790 to the Present. New York: Basic Books; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown B, Larson W, Saraswathi T. The World's Youth—Adolescence in Eight Regions of the Globe. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dasen P. Int. J. Group Tensions. 2000;29:17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlegel A, Barry H. Adolescence: An Anthropological Enquiry. New York: Free Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs E. Youth in a Changing World. New York: Free Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delaney C. Adolescence. 1995;30:891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoover J. Reaching Today's Youth. 1998;3:2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Susman E. J. Res. Adolescence. 1997;7:283. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belsky J, Steinberg L, Draper P. Child Dev. 1991;62:647. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinberg L, Hill J. Dev. Psychol. 1978;14:683. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams J, Currie C. J. Early Adolescence. 2000;20:129. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haynie D. Social Forces. 2003;82:355. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blakemore SJ, Choudhury S. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2006;47:296. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elder G. Children of the Great Depression: Social Change in Life Experience. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadsworth M. The Imprint of Time. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas A, Chess S, Birch H. Temperament and Behaviour Disorders in Children. New York: New York Univ. Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Victora C, Barros F. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2006;35:237. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richter L, Norris S, De Wet I. Paediatric Perinatal Epidemiol. 2004;18:572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbarin O, Richter L. Mandela's Children: Growing up in Post-Apartheid South Africa. New York: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richter L, Griesel R, Barbarin O. In: International Perspectives on Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Singh N, Leung J, Singh A, editors. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000. pp. 159–182. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richter L, Morrell R. Baba: Men and Fatherhood in South Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richter L. Psychosocial Studies in Birth to Twenty: Focusing on Families. Johannesburg, South Africa: Birth to Twenty; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galambos N, Leadbeater B. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2000;24:289. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crowther N, Trusler J, Cameron N, Toran N, Gray I. Diabetologia. 2000;43:978. doi: 10.1007/s001250051479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herman-Giddens ME, Bourdony C, Slara E, Wasserman R. Pediatrics. 2001;107:609. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cameron N, Wright C. S. Afr. Med. J. 1990;78:536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellis B. Psychol. Bull. 2004;130:920. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Udry J. J. Biol. Sci. 1979;11:411. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ge X, Conger R, Elder G. Dev. Psychol. 2001;37:404. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berkey C, Gardner A, Colditz G. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000;152:446. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.5.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norris S, Richter L. J. Res. Adolescence. 2005;15:609. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bauman K, Koch G, Bryan E, Haley N, Downton M, Orlandi M. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1989;130:327. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marrazzo J, White C, Krekeler B, Celum C, Laffery W, Stamm W, Handsfield H. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997;127:796. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mensch B. Demography. 2003;40:247. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garmezy N. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 1971;41:101. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1971.tb01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luthar SS, Zigler E. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 1991;61:6. doi: 10.1037/h0079218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Susman E. J. Res. Adolescence. 1997;7:283. [Google Scholar]