Abstract

To probe the size of the ion channel formed by Pseudomonas syringae lipodepsipeptide syringomycin E, we use the partial blockage of ion current by penetrating poly(ethylene glycol)s. Earlier experiments with symmetric application of these polymers yielded a radius estimate of ~1 nm. Now, motivated by the asymmetric non-ohmic current-voltage curves reported for this channel, we explore its structural asymmetry. We gauge this asymmetry by studying the channel conductance after one-sided addition of differently sized poly(ethylene glycol)s. We find that small polymers added to the cis-side of the membrane (the side of lipodepsipeptide addition) reduce channel conductance much less than do the same polymers added to the trans-side. We interpret our results to suggest that the water-filled pore of the channel is conical with cis- and trans-radii differing by a factor of 2–3 and that the smaller cis-radius is in the 0.25–0.35 nm range. In symmetric, two-sided addition, polymers entering the pore from the larger opening dominate blockage.

Keywords: Syringomycin E, Channel sizing, Polymer exclusion, Lipid bilayers, Poly(ethylene glycol)s

1. INTRODUCTION

Cyclic lipodepsipeptide produced by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae syringomycin E (SRE) forms ion channels in planar lipid bilayers [1–3]. At one (cis-) side SRE addition to the bilayer, the channels are characterized by non-linear and asymmetric current-voltage curves, suggesting an asymmetry of the channel structure [3]. Previously, the method of non-electrolyte exclusion [4–10] was used to estimate the radius of the SRE channel, which was found to be close to 1 nm [11]. However, this estimate, obtained under symmetric application of polymeric non-electrolytes, refers to an effective radius of the pore, leaving the question on the pore asymmetry open.

In this letter we report the results of the pore geometry probing with asymmetric addition of poly(ethylene glycol)s (PEGs). When polymers of varied molecular weight are applied from the different sides of the membrane, the changes in the single channel conductance may reflect upon the sizes of channel cis- or trans-openings and location of the constrictions in the pore lumen [12–15]. We follow the changes in SRE single channel conductance induced by differently sized PEGs added to either cis- or trans-side of the lipid bilayer. We find that polymers added from the trans-side affect the channel conductance much more effectively, suggesting the larger size of the channel opening at the trans-side of the bilayer (opposite to the side of SRE addition). Using available approaches for polymer partitioning [16–19], we build a model to describe the polymer-induced conductance changes in pores of varying diameter. Assuming a simple conical geometry of the SRE pore, we estimate the radii of the cis- and trans- openings as 0.25–0.35 nm and 0.5–0.9 nm, respectively.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

All chemicals were of reagent grade. Synthetic 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (PS), and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (PE) were from Avanti Polar Lipids. Water was deionized and double-distilled. Solutions of 1 M NaCl (J. T. Butler) were buffered with 5 mM MOPS (Sigma), pH 6. Syringomycin E was purified as previously described [20]. The poly(ethylene glycol)s (PEGs) of different molecular weights: PEG200, PEG300, PEG400, PEG600, PEG1000, PEG1500, PEG3400, and PEG4600 were purchased from Sigma and used in 15% w/w concentration. Polymers were added to 1 M NaCl solution in water.

Bilayer lipid membranes were prepared by monolayer-opposition technique on a 50–100 μm diameter aperture in the 10-μm thick Teflon film separating two (cis and trans) compartments of the Teflon chamber [6, 21]. Membranes were made from the equimolar mixture of PS and PE. PEGs of varied molecular weights were added from one side of the membrane, while the impermeant PEG4600 was on the other side. SRE was added to the aqueous phase of the cis-side compartment at the concentration 1–5 μM. Ag/AgCl electrodes with agarose / 2 M KCl bridges were used to apply transmembrane voltage (V) and to measure the single channel current. “Positive voltage" means that the cis-side compartment is positive with respect to the trans-side. All experiments were performed at room temperature.

Current measurements were carried out using Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments) in the voltage clamp mode. Data were filtered by a low-pass 8-pole Bessel filter (Model 9002, Frequency Devices) at 1 kHz and directly recorded into the computer memory with a sampling frequency of 5 kHz. Data were analyzed using pClamp 9.2 (Axon Instruments) and Origin 7.0 (Origin Lab).

Conductance-wise SRE channels split into two different populations: “small” and “large” channels, whose relative statistics depend on the experimental conditions [22]. It was shown earlier that the large channels are the clusters of simultaneously opening/closing small channels [2, 11]. Here we focus on the PEG-induced changes in the current of the small SRE-channels. Current transition histograms were generated for each tested voltage. Histogram peaks were fitted with the normal distribution function. Single channel conductance was calculated as the mean single-channel current divided by the applied transmembrane voltage.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

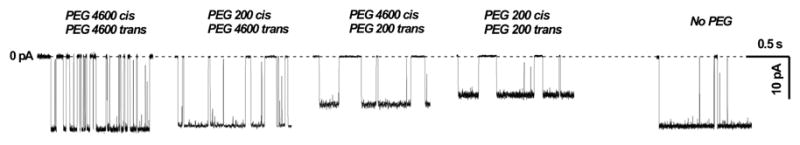

As shown by Kaulin et al. [11], PEG200 penetrates into the SRE channel pore while PEG1500 and heavier PEGs are strongly excluded. Fig. 1 shows the samples of transmembrane current fluctuations corresponding to opening/closure of elementary SRE channels in the presence of permeant PEG200 and impermeant PEG4600 at different sides of the bilayer. The single channel conductance decreases in the following series: PEG4600 cis / PEG4600 trans, PEG200 cis / PEG4600 trans, PEG4600 cis / PEG200 trans, PEG200 cis / PEG200 trans. The decrease of the channel conductance in the presence of PEG is related to polymer partitioning into the channel pore [5–10].

Figure 1.

The effect of cis- and trans-side addition of PEG200 and PEG4600 (15 % w/w) on the current through a single SRE channel in PS/PE bilayer, bathed by 1 M NaCl, pH 6, at V = −200 mV. The decrease of the channel conductance in the presence of PEG is related to its partitioning into the channel pore: PEG4600 is strongly excluded, while PEG200 penetrates the channel pore, displaces the ions, and increases solution viscosity. However, permeating PEG200 affects SRE-channel conductance asymmetrically.

The rightmost sample shows the current through the channel in the absence of polymers. It is somewhat smaller than the current in the presence of the impermeant PEG4600 (the leftmost sample) because of the changing electrolyte activity [6,9].

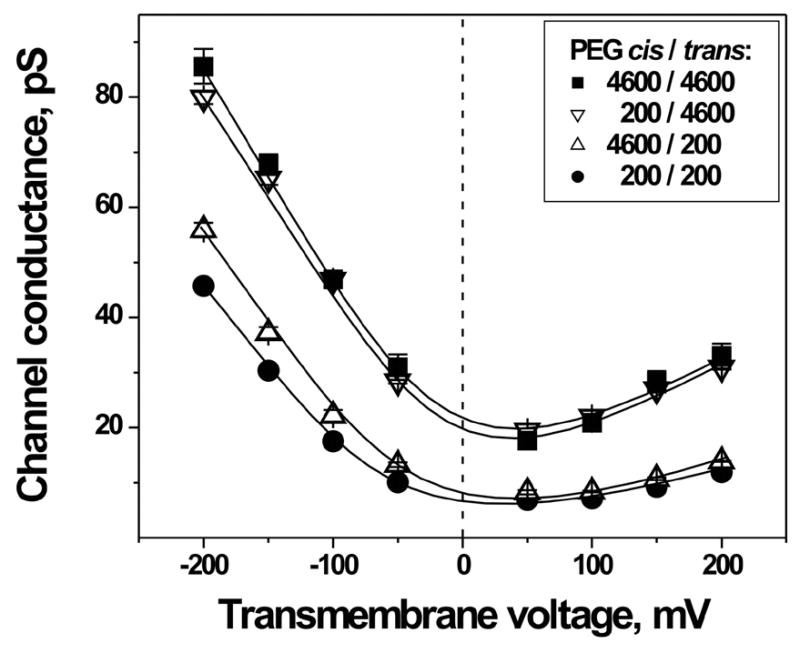

Fig. 2 presents the conductance-voltage characteristics of the SRE channel in the presence of PEGs applied from different sides of the membrane. The channel conductance is pronouncedly reduced by PEG200 applied from the trans-side of the bilayer (opposite the side of SRE addition), but not from the cis-side. These data suggest that the pore constriction is located closer to the cis-opening. One also can see that the effect of symmetric application of PEG200 is a sum of the effects of the cis- and trans-side applications of this non-electrolyte.

Figure 2.

The conductance-voltage characteristics of SRE-channel in the presence of PEG200 and PEG4600 added from the different sides of the membrane. PEG200 reduces the channel conductance to a larger extent when applied from the trans-side.

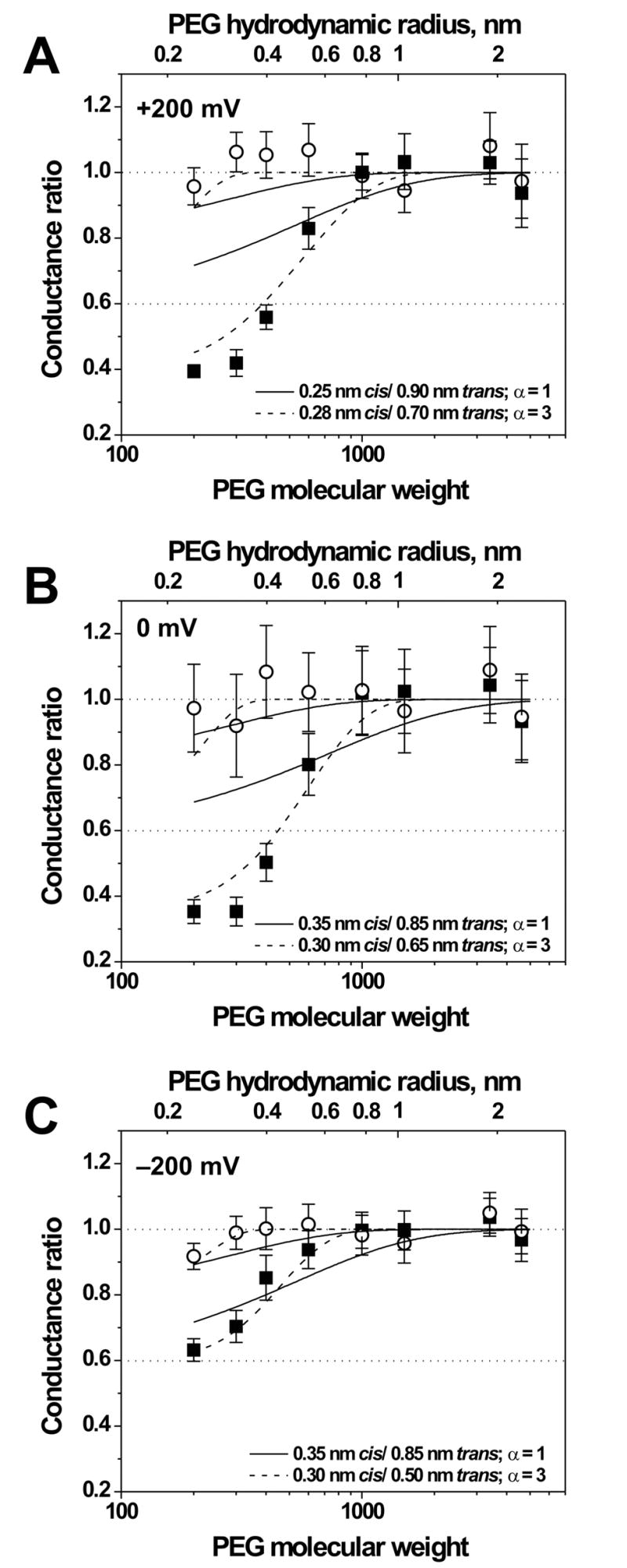

We measured the channel conductance in the presence of differently sized polymers applied from either cis- or trans-side of the membrane with the impermeant PEG4600 on the opposite side. Fig. 3 summarizes our results for V = +200 mV, V → 0 mV, and V = −200 mV (Fig. 3 A, B, and C, respectively). To compare the degree to which these non-electrolytes permeate the channel pore from cis- or trans-side of the bilayer, in Fig. 3 we plot the ratio of the channel conductance in the presence of a given PEG to the mean channel conductance in the presence of impermeant PEGs (PEG1500, PEG3400, PEG4600). From the results in Fig. 3 one can see that the effect of PEG addition to the cis-side of the bilayer (open circles) is pronouncedly different from that of the trans-side addition (solid squares). At the cis-side PEG application there are no significant changes in the channel conductance in the whole range of PEG molecular weight for V = 0 mV and V = +200 mV (Fig; 3 A, B); only for the case of V = −200 mV, application of PEG200 produces a reliable conductance decrease indicating partial partitioning of this PEG into the channel pore (Fig. 3 C). With the trans-side polymer application, the channel conductance decrease is observed for all PEGs with molecular weight smaller than 1000. For the case of V = 0 mV and V = +200 mV, the channel conductance ratio decreases from 1.0 to 0.4 with the decrease of PEG molecular weight from 1000 to 300; subsequent decrease of PEG molecular weight to 200 does not affect the channel conductance (Fig. 3, A, B). Note that PEG200, PEG300, and PEG400 decrease the channel conductance more effectively than bulk conductivity (dotted line at 0.6), suggesting polymer accumulation in the channel pore. For V = −200 mV (Fig. 3 C) the dependence of the channel conductance ratio on PEG molecular weight is similar, however the decrease of molecular weight from 1000 to 200 results in a gradual reduction of the conductance ratio from 1.0 to 0.6.

Figure 3.

The relative changes in SRE-channel conductance as functions of the PEG molecular weight. Hydrodynamic radii of the polymer [30] are denoted on the top axis. Open circles and solid squares correspond to the cis- and trans-side side application of polymer of varying molecular weight, respectively (the impermeant PEG4600 was on the opposite side). The dotted line at 0.6 corresponds to the ratio of bulk solution conductivities with and without polymers. Panels A, B, and C show changes of the conductance ratio at V = +200 mV, 0 mV, and −200 mV, respectively. The solid lines in all three panels present the best-fit predictions based on the scaling law (Eqs. (1), (2), (4), and (5)) for the given pair of cis and trans-side channel radii; the dashed lines are the best fits using α = 3 (see text) and χ as an adjustable parameter.

Close similarity of the dependence of the channel conductance ratio on PEG molecular weight at the cis and trans-side polymer application for V = 0 mV and V = +200 mV (Fig. 3 A, B) suggests that in the indicated voltage range the channel geometry is preserved. The cis-side addition of PEG at V = −200 mV (Fig. 3 C) is also close to the dependencies observed at V = 0 mV and V = +200 mV. However, there is a difference of the trans-side PEG partitioning in the channel pore at V = −200 mV (Fig. 3 C) and at V = 0, V = +200 mV (Fig. 3 A, B). The smaller effect at V = −200 mV can be tentatively attributed to the electro-osmotic water flow from the cis- to the trans-side of the channel [23] induced by its anion selectivity [1, 2, 11]. This flow can decrease partitioning of the permeating PEGs applied from the trans-side of the bilayer. For this reason, the actual channel geometry may be the same as in the 0, +200 mV voltage range. However, still another possibility is the voltage-dependent changes in the SRE channel geometry.

We consider the decrease of the channel conductance to be a result of PEG partitioning into the SRE channel. For simplicity we assume that the geometry of the channel water-filled pore can be approximated by a regular cone. Indeed, given the channel length L, this geometry can be described by two parameters only: by the radii of the cis- and trans-openings.

We also assume that the pore conductance can be written in the form:

| (1) |

where χ(w, x) is the averaged local electrolyte conductivity, which depends on PEG molecular weight (w) and coordinate along the pore axis (x); R(x) is the local pore radius. To calculate the integral in Eq. (1) for a particular geometry, one should define χ(w, x).

It was shown that conductivity of electrolyte solutions decreases approximately linearly with the increasing monomeric content of PEG up to nearly 25% w/w concentration [24]. Based on this observation, for the averaged local electrolyte conductivity in the channel we write:

| (2) |

where χ0 is the solution conductivity in the absence of PEG in the channel (85 mS/cm), χ is the solution conductivity in the presence of fully permeant PEG, and p(w,x) − polymer partition coefficient, the ratio of the monomer density inside the channel to that in the outside solution. For completely excluded polymers χ(w, x) = χ0 , since their partition coefficient is equal to zero, while for PEGs that easily access the entire channel volume, χ(w, x) = χ.

In the previous studies with asymmetric polymer application [12–15] a so called “filling factor”, Φ(w) , was introduced by assuming that for a cone-shaped pore at polymer application from the wider opening the partition coefficient is:

| (3) |

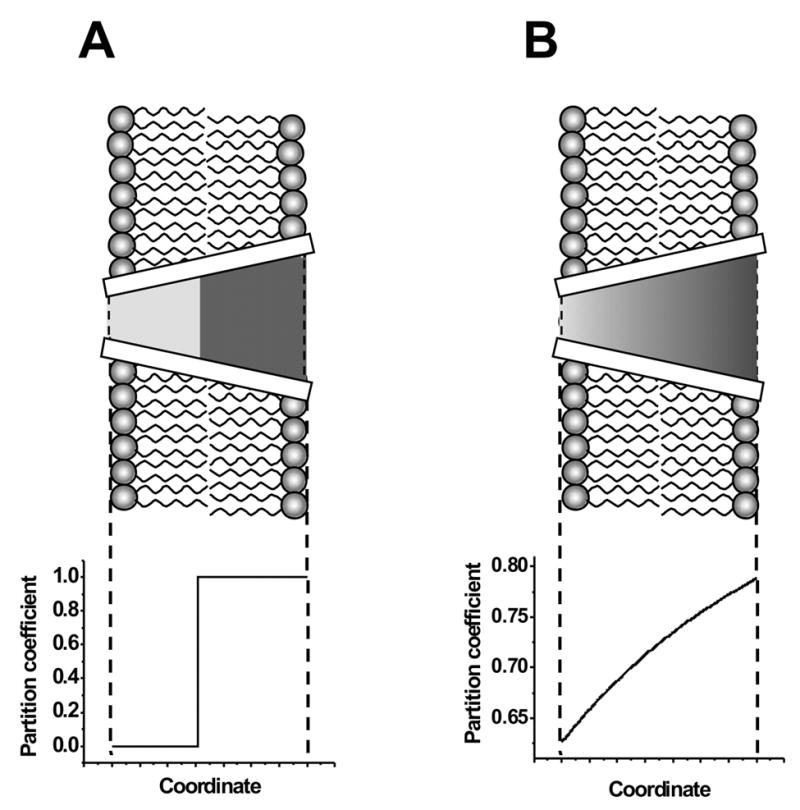

where Φ(w) describes the ratio of the pore length accessible to a polymer of a given molecular weight to the total pore length. Fig. 4 A shows the profile of the partition coefficient given by Eq. (3). This simple approximation (see discussion in ref. [13]) proved to be useful in a number of studies aimed at probing structural asymmetry of ion channels [12–15].

Figure 4.

The comparison of the partition coefficient profiles along the axis of a cone-shaped channel, which are given by Eq. (3) (panel A), and Eq. (4), (panel B). The permeating polymer is applied from the side of the larger channel opening, which corresponds to the trans-side in the case of the SRE channel.

More realistic picture of polymer partitioning should not involve a step function in polymer distribution along the pore of variable radius. Be it hard spheres or “soft” polymer particles, their partitioning is always a smooth function of pore radius [9, 13, 25, 26]. Here, as an improved, but still crude, approximation we assume that the functional dependence is given by the scaling theory [17, 18] if penetrating polymers are applied from the wider opening of the channel. According to this approach, the free energy cost of polymer partitioning into a cylindrical pore is proportional to polymer length and, therefore, to its molecular weight ΔF (w) ∝ w . Unfortunately, the scaling arguments do not give the numerical value of the proportionality coefficient which is necessary for the size estimation. To obtain this coefficient, we use results obtained earlier for other channels [9, 26]. According to these studies, the free energy of polymer confinement by the channel equals 1kT when the hydrodynamic radius of a PEG molecule is close to 1.68 of the channel radius. We designate this empirical parameter as γ . At this polymer size the partition coefficient reduces e times compared to equi-partitioning ( p = 1.0).

Taking into account these considerations and also keeping in mind that water for PEG is a good solvent, i.e., r (w) ∝ w3/5 , for polymer partitioning from the wider channel opening we assume:

| (4) |

where r (w) is the hydrodynamic radius of the polymer, and γ = 1.68 as explained above. Equation (4) describes equilibrium partitioning. Therefore, for the one-sided (asymmetric) application of polymers, which corresponds to non-equilibrium conditions it should be used with caution. We assume that in the case of a conical geometry with a significant difference in radii, the non-equilibrium effects are small if penetrating polymers are applied from the side of the larger radius (trans-side of the SRE channel). As illustrated in Fig. 4 B, for a polymer of a given molecular weight Eq. (4) predicts a gradual increase of p (w, x) with the increase of the channel radius along the x-coordinate.

For the partitioning of polymers applied from the side of the smaller radius (cis-side), the non-equilibrium distribution dominates. We assume that at the cis-opening the concentration can be calculated using Eq. (4), while for the rest of the channel the Fick-Jacobs approximation [27] is valid. This approximation accounts for particle diffusion in irregularly shaped pores, including the case of increasing radius toward the trans-side:

| (5) |

where x is the distance along the channel axis measured from the cis-opening.

The solid lines in Fig. 3 show the fitting of Eqs. (1), (2), (4), and (5) to the obtained data. The fitting is poor because, as in the case of other channels studied so far [9, 13, 26, 28] the dependence of partitioning on polymer size is much stronger than the scaling theory prediction. Following these studies, we introduce an empirical parameter α that sharpens the transition between excluded and penetrating polymers by assuming ΔF (w) ∝ wα. The physical meaning of the deviation of this parameter from unity is not clear. This can be related to both channel-polymer [9] and polymer-polymer interactions in the confinement of the channel [29]. In addition, the effect of small polymers (panels A and B) on the channel conductance is greater than that on the bulk solution conductivity, suggesting PEG partitioning to an excess of its bulk concentration. To account for this, we use χ in Eq. (2) as an additional adjustable parameter. As in the case of alpha-Hemolysin channel, fittings with α = 3 (χ = 34, 30, and 50 mS/cm for Fig. 3, panels A, B, and C, respectively) shown by the dashed lines demonstrates much better agreement (compare with Fig. 5 of [9] and Fig. 8 of [26]). The results of the best fittings for both procedures for all the voltages give the following ranges of the cis- and trans- channel radii: 0.25–0.35 nm and 0.5–0.9 nm, respectively.

To conclude, our polymer partitioning study reveals a pronounced asymmetry of the SRE channel, with its cis-opening being much narrower than the trans-opening. Thus, the presumably lipidic trans-part of the channel structure [3] is considerably wider than the peptide part. It is worth mentioning that the obtained results agree with the data on symmetric application of PEGs [11]. In the case of symmetric addition, partitioning of polymers from the trans-side dominates channel blockage, thus leading to a radius estimate close to 1 nm.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Adrian Parsegian and Sasha Berezhkovskii for fruitful discussions and to Jon Takemoto for the generous gift of SRE. This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, grant # 06-04-48860, grant SS-4904.2006.4 and Program “Molecular and Cell Biology” RAS.

Abbreviations

- SRE

syringomycin E

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PS

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine

- PE

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Feigin AM, Takemoto JY, Wangspa R, Teeter JH, Brand JG. Properties of voltage-gated ion channels formed by syringomycin E in planar lipid bilayers. J Membr Biol. 1996;149:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s002329900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schagina LV, Kaulin YA, Feigin AM, Takemoto JY, Brand JG, Malev VV. Properties of ionic channels formed by the antibiotic syringomycin E in lipid bilayers: dependence on the electrolyte concentration in the bathing solution. Membr Cell Biol. 1998;12:537–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malev VV, Schagina LV, Gurnev PA, Takemoto JY, Nestorovich EM, Bezrukov SM. Syringomycin E channel: a lipidic pore stabilized by lipopeptide? Biophys J. 2002;82:1985–1994. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75547-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerberg J, Parsegian VA. Polymer inaccessible volume changes during opening and closing of a voltage-dependent ionic channel. Nature. 1986;323:36–39. doi: 10.1038/323036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krasilnikov OV, Sabirov RZ, Ternovsky VI, Merzliak PG, Muratkhodjaev JN. A simple method for the determination of the pore radius of ion channels in planar lipid bilayer membranes. FEMS Microbiol Immunol. 1992;5:93–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bezrukov SM, Vodyanoy I. Probing alamethicin channels with water-soluble polymers. Effect on conductance of channel states. Biophys J. 1993;64:16–25. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81336-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korchev YE, Bashford CL, Alder GM, Kasianowicz JJ, Pasternak CA. Low conductance states of a single ion channel are not “closed”. J Membr Biol. 1995;147:233–239. doi: 10.1007/BF00234521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parsegian VA, Bezrukov SM, Vodyanoy I. Watching small molecules move: interrogating ionic channels using neutral solutes. Biosci Rep. 1995;15:503–514. doi: 10.1007/BF01204353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bezrukov SM, Vodyanoy I, Brutyan RA, Kasianowicz JJ. Dynamics and free energy of polymers partitioning into a nanoscale pore. Macromolecules. 1996;29:8517–8522. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai SA, Rosenberg RL. Pore size of the malaria parasite's nutrient channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2045–2049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaulin YA, Schagina LV, Bezrukov SM, Malev VV, Feigin AM, Takemoto JY, Teeter JH, Brand JG. Cluster organization of ion channels formed by the antibiotic syringomycin E in bilayer lipid membranes. Biophys J. 1998;74:2918–2925. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77999-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krasilnikov OV, Da Cruz JB, Yuldasheva LN, Varanda WA, Nogueira RA. A novel approach to study the geometry of the water lumen of ion channels: colicin Ia channels in planar lipid bilayers. J Membr Biol. 1998;161:83–92. doi: 10.1007/s002329900316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merzlyak PG, Yuldasheva LN, Rodrigues CG, Carneiro CM, Krasilnikov OV, Bezrukov SM. Polymeric nonelectrolytes to probe pore geometry: application to the alpha-toxin transmembrane channel. Biophys J. 1999;77:3023–3033. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77133-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuldasheva LN, Merzlyak PG, Zitzer AO, Rodrigues CG, Bhakdi S, Krasilnikov OV. Lumen geometry of ion channels formed by Vibrio cholerae EL Tor cytolysin elucidated by nonelectrolyte exclusion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1512:53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carneiro CM, Merzlyak PG, Yuldasheva LN, Silva LG, Thinnes FP, Krasilnikov OV. Probing the volume changes during voltage gating of Porin 31BM channel with nonelectrolyte polymers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1612:144–153. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casassa EF. Equilibrium distribution of flexible polymer chains between a macroscopic solution phase and small voids. Polymer Lett. 1967;5:773–778. [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Gennes P-G. Scaling concepts in polymer physics. Cornell University Press; Ithaca. New York: 1979. pp. 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grosberg A Yu, Khokhlov AR. Statistical physics of macromolecules. American Institute of Physics, AIP Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teraoka I. An introduction to physical properties. A John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2001. Polymer solutions; pp. 156–157. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bidwai AP, Zhang L, Bachmann RC, Takemoto JY. Mechanism of action of Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxin, syringomycin: stimulation of red beet plasma membrane ATPase activity. Plant Physiol. 1987;83:39–43. doi: 10.1104/pp.83.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montal M, Mueller P. Formation of bimolecular membranes from lipid monolayers and a study of their electrical properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972;69:3561–3566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.12.3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostroumova OS, Malev VV, Kaulin YA, Gurnev PA, Takemoto JY, Schagina LV. Voltage-dependent synchronization of gating of syringomycin E ion channels. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5675–5679. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu LQ, Cheley S, Bayley H. Electroosmotic enhancement of the binding of a neutral molecule to a transmembrane pore. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15498–15503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2531778100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stojilkovic KS, Berezhkovskii AM, Zitserman V Yu, Bezrukov SM. Conductivity and microviscosity of electrolyte solutions containing polyethylene glycols. J Chem Phys. 2003;119:6973–6978. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colton CK, Satterfield CN. Diffusion and partitioning of macromolecules within finely porous glass. AIChE J. 1975;21:289–298. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rostovtseva TK, Nestorovich EM, Bezrukov SM. Partitioning of differently sized poly(ethylene glycol)s into OmpF porin. Biophys J. 2002;82:160–169. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75383-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zwanzig R. Diffusion past an entropy barrier. J Phys Chem. 1992;96:3926–3930. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nestorovich EM, Sugawara E, Nikaido H, Bezrukov SM. Pseudomonas aeruginosa porin OprF: properties of the channel. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16230–16237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600650200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krasilnikov OV, Bezrukov SM. Polymer partitioning from non-ideal solutions into protein voids. Macromolecules. 2004;37:2650–2657. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuga SJ. Pore size distribution analysis of gel substances by size exclusion chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1981;206:449–461. [Google Scholar]