Abstract

The genetic stability of tandemly repeated DNAs is affected by repeat sequence, tract length, tract purity, and replication direction. Alterations in DNA methylation status are thought to influence many processes of mutagenesis. By use of bacterial and primate cell systems, we have determined the effect of CpG methylation on the genetic stability of cloned di-, tri-, penta- and minisatellite repeated DNA sequences. Depending on the repeat sequence, methylation can significantly enhance or reduce its genetic stability. This effect was evident when repeat tracts were replicated from either direction. Unexpectedly, methylation of adjacent sequences altered the stability of contiguous repeat sequences void of methylatable sites. Of the seven repeat sequences investigated, methylation stabilized five, destabilized one, and had no effect on another. Thus, although methylation generally stabilized repeat tracts, its influence depended on the sequence of the repeat. The current results lend support to the notion that the biological consequences of CpG methylation may be affected through local alterations of DNA structure as well as through direct protein–DNA interactions. In vivo CpG methylation in bacteria may have technical applications for the isolation and stable propagation of DNA sequences that have been recalcitrant to isolation and/or analyses because of their extreme instability.

[Supplementary material available online at http://www.genome.org.]

The genetic stability of repeated DNA sequences is affected by various factors including the sequence of the repeat, the number of repeats in a given tract, the purity of the repeat tract, and the direction of replication. Repeat tracts are unstable in metazoan, lower eukaryotic, and prokaryotic organisms. In many cases, the genetic instability of repeat sequences is associated with or indeed the cause of several human diseases (de la Chapelle and Peltomaki 1995; Cummings and Zoghbi 2000). With the recent advent of the draft of the human genome it is important to complete the sequence, making it necessary to fill in the gaps (Bork and Copley 2001; Eichler 2001). Many of these gaps have remained unsequenceable because they are unclonable, at least stably. Many of these sequences are composed of repeat sequences. In an attempt to facilitate stable maintenance of cloned repeat tracts, we have considered CpG methylation as a factor that may contribute to repeat stability. Alterations in CpG methylation is a candidate modifier of primate repeat stability because many unstable elements are part of or are embedded within large CpG islands. Furthermore, the instability of certain repeats is restricted to specific loci (Richards et al. 1996), specific tissues (Anvret et al. 1993; Malter et al. 1997), or differentiation status (Burman et al. 1999; Wohrle et al. 2001), or instability occurs only during specific developmental stages (Malter et al. 1997; Martorell et al. 1997). Because CpG methylation is highly regulated in a tissue- and development-specific manner (Razin and Shemer 1995), its alteration may contribute to repeat instability.

In humans, numerous processes of mutagenesis are thought to be influenced by and/or associated with alterations in DNA methylation status. Evidence supporting this notion comes from apparent differences in genetic stability of the methylated and unmethylated expanded (CGG)n repeat of fragile X (Malter et al. 1997; Wohrle et al. 1998; Burman et al. 1999; Wohrle et al. 2001) and the hypermethylation associated with large expansions of the myotonic dystrophy (CTG)n repeat (Steinbach et al. 1998). Hyper- and hypomethylation in certain tumors is associated with microsatellite instabilities (Herman et al. 1998; Toyota et al. 1999) and large deletions (Makos et al. 1993). Hypomethylation induced by drug treatment (Haaf 1995) or by the loss of DNA methyltransferases (Jeanpierre et al. 1993; Chen et al. 1998; Xu, et al. 1999) results in increased rates of mutation and chromosome instability. Methylation of retroelements and satellite repeats is thought to provide a defense against transposition, duplication, and recombination (Doerfler 1996; Yoder et al. 1997; Symer and Bender 2001). Together these associations indicate an intimate relationship between methylation and sequence instability.

We have analyzed the effect of CpG methylation on the genetic stability of various cloned di-, tri-, penta-, and minisatellite repeats using a modified bacterial system. Bacteria do not contain endogenous CpG methylases. Generally, bacterial cells contain restriction enzymes that specifically attack DNAs that are CpG methylated. Genetic ablation of these bacterial methyl-specific restriction systems can avoid DNA degradation and permit cloning of methylated sequences but may not provide ongoing stability. We have established a bacterial system, which permits ongoing in vivo CpG methylation. We find that, depending on the repeat sequence, methylation can significantly enhance or reduce its genetic stability. It is interesting that in a similar fashion, premethylation of some of the templates can modify repeat instability after transfection and SV40-mediated replication within primate cells.

RESULTS

A Bacterial System to Assay the Effect of CpG Methylation on Repeat Stability

We have developed an in vivo bacterial model to test the effect of methylation on the genetic stability of cloned unstable DNA sequences. Plasmids containing various unstable elements were cotransformed into Escherichia coli with pAIT2, a plasmid that expresses the SssI CpG methylase, which de novo methylates the 5 position of cytosine residues at CpG sites (Renbaum et al. 1990). Although E. coli do not possess endogenous CpG methylases, in this in vivo system virtually any plasmid DNA propagated within cells also containing the pAIT2 plasmid will become methylated at almost every CpG site (>90% as assessed by the use of methyl-sensitive restriction enzymes, Fig. 1A; see also Renbaum et al. 1990). We found that expression of the SssI methylase had a minimal effect on the growth of the cells, in agreement with previous observations (Renbaum et al. 1990) that the CpG methylation of the chromosomal DNA (methylated to the extent of 50%) did not interfere with cell physiology. Because the number of cell generations was equivalent in the presence or the absence of in vivo methylation and the yield of plasmid per generation was similar, a direct comparison of stability was possible. Hence, this experimental system can be used to determine the effect of DNA methylation on the genetic instability of specific cloned sequences during growth in living cells.

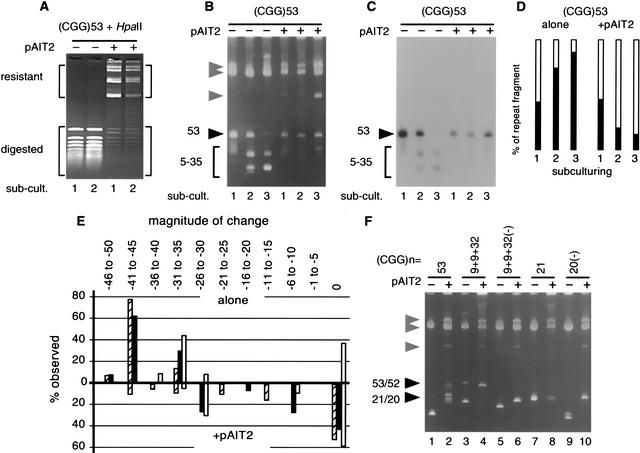

Figure 1.

Effect of methylation on the genetic stability of fragile X (FRAXA) (CGG)n repeats. (A) The pFXA53 plasmid containing (CGG)53 (Table 1) was propagated in Escherichia coli in the absence or presence of the SssI methylase-expressing plasmid pAIT2. The methylation status of the DNAs was monitored by methyl-sensitive HpaII restriction digestion. Shown is the analysis of the first and second subculturings (each representing 25 generations) of pFXA53. (B) After three subculturings, an aliquot of cells was harvested and plasmids were isolated, restriction digested, and analyzed by 4% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and ethidium bromide staining. To test for repeat length changes, DNAs were digested with KpnI and SacI, which liberates the (CGG)n-containing fragments from the pFXA clones, which are resolvable from pAIT2 and vector bands. The starting (CGG)n lengths are indicated by filled arrowheads; all other faster migrating DNAs are products of (CGG)n deletions indicated by vector bands, indicated by shaded arrowheads. This gel is representative of five or more independent experiments. (C) To confirm that products were caused by changes in repeat numbers, the gel shown in panel A was electrotransferred to nylon membrane and hybridized to 32P-labeled (CGG)10 oligonucleotides and exposed for autoradiography. (D) The effect of methylation (±pAIT2) on repeat stability was determined by densitometric analysis of multiple experiments as described (Kang et al. 1995). The open area represents the percentage of material with the starting repeat length, whereas the filled area represents the percentage of deletion products. (E) The magnitude of repeat loss was determined by streaking on plates cells from each subculturing of a test plasmid in the absence or presence of methylation (±pAIT2), isolation of ≥20 single colonies, and analysis of their DNA. The analysis of pFXA53 is shown. Deletion sizes for the first, second, and third subculturings are shown by hollow, filled, and cross-hatched bars, respectively. (F) FRAXA plasmids containing the indicated lengths, purities, and orientations of (CGG)n tracts (Table 1) were propagated through three subculturings in E. coli in the absence or presence of methylation (± pAIT2). After each subculturing, cells were harvested and (CGG)n repeat length changes analyzed as above. The trend through the three subculturings is reflected by the final subculture; hence only the third subculturing is shown for each plasmid. This gel is representative of five or more independent experiments. Products are labeled as in panel B.

CpG Methylation Stabilizes (CGG)n

The genetic instability of the (CGG)n repeat of fragile X (FRAXA) mental retardation syndrome is sensitive to the length, purity, and methylation status of the repeat tract. Tracts >33 pure repeats are unstable. Length heterogeneity is routinely observed in the expanded (n = 200–1000) repeats of FRAXA patients (Wohrle et al. 1998), as well as in premutation individuals (Nolin et al. 1999) and rare cases of length mosaicism within normal range (n = 29–51) that have been reported as having apparent somatic deletions (n = 11–34) (Brown and Nolin 2000; Tzountzouris et al. 2000). “High-functioning” FRAXA patients display high levels of CGG length heterogeneity, with alleles lacking aberrant CpG methylation frequently containing 130 to 300 repeats, whereas longer tracts within the same tissue were methylated (Wohrle et al. 1998). Completely and partially methylated CGG tracts as short as 20 to 100 repeats have also been observed (Allingham-Hawkins et al. 1996; Tassone et al. 1999; Genc et al. 2000). It has been suggested that for both germline and somatic tissues, the absence of CpG methylation may enhance the deletion of (CGG)n repeats (Burman et al. 1999; Helderman-van den Enden et al. 1999; Salat et al. 2000; Wohrle et al. 2001). However, it is not clear how methylation might contribute to CGG instability.

Cloned tracts of CGG repeats are extremely unstable in bacteria and display a strong tendency to delete (Pearson and Sinden 1996; Shimizu et al. 1996; Hirst and White 1998). We took advantage of the bacterial propensity for repeat deletions to test the effect of CpG methylation on the stability of (CGG)n repeats. We used the E. coli in vivo methylation system described above (and in Methods) and a series of FRAXA patient-derived clones with repeat lengths above and below the stability threshold length of 34 repeats (Table 1) (Pearson and Sinden 1996; Pearson et al. 1998). Some clones also contained stabilizing AGG interruptions. Each pFXA plasmid was transformed alone or with the SssI methylase-expressing plasmid, pAIT2. Cells were propagated and subcultured three times (Methods) (Bowater et al. 1996). The stability of the (CGG)n tract from each subculturing was then determined by analyzing the length of the repeat-containing fragment by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). We found that the stability of (CGG)n tracts was increased in the presence of the SssI methylase. A representative experiment is shown in Figure 1, panels B–E. In the absence of methylation, (CGG)53 repeats rapidly deleted through the subculturings incurring deletions of ≥35 to 45 repeats, leaving only minor amounts of starting length material (Fig. 1, B and C). In vivo methylation resulted in increased stability of the (CGG)53 repeat (Fig. 1, B and C, compare third subculture in the presence and absence or pAIT2). This stabilization was manifest as both fewer deletion events (Fig. 1D) and smaller deletion magnitudes (rarely incurring losses of ≥30 repeats) (Fig. 1E). Changes in electrophoretic migration were confirmed to be caused by changes in numbers of repeats by Southern blot hybridization specific for (CGG)n repeats (Fig. 1C) and through DNA sequencing of individual deletion products (not shown). This increased stability was evident only in cotransformations with pAIT2, which expressed the SssI methylase. In the absence of methylation, (CGG)n repeats tended to rapidly delete, with longer pure repeats being more unstable than interrupted or shorter tracts (Fig. 1F, compare lane 1 with 3 and 7). In the absence of methylation, a (CGG)52 tract interrupted with two AGG units (pFXA9 + 9 + 32) displayed a few deletions but was considerably more stable than the similar length pure tract pFXA53 (Fig. 1F, compare lane 3 with 1). In the presence of methylation, however, the interrupted repeat tract of pFXA9 + 9 + 32 showed no deletions, indicating increased genetic stability (Fig. 1F, compare lane 3 with 4). Thus, in addition to repeat tract interruptions, CpG methylation also stabilized the (CGG)n repeats.

Table 1.

Sequences/Clones Analyzed

| Clone name | Repeat length | Repeat configuration | Replication orientation | Effect of methylation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fragile X mental retardation | ||||

| pFXA53 | (CGG)53 | Pure | + | Stabilized |

| pFXA9+9+32 | (CGG)52 | 9+9+32 | + | Stabilized |

| pFXA9+9+32(−) | (CGG)52 | 9+9+32 | − | Stabilized |

| pFXA20 | (CGG)20 | Pure | + | No effect |

| pFXA21(−) | (CGG)21 | Pure | − | Stabilized |

| Myotonic dystrophy | ||||

| pRW3211 | (CTG)17 | Pure | + | No effect |

| pRW2180 | (CTG)30 | Pure | + | No effect |

| pRW3214 | (CTG)83 | Pure | + | Stabilized, exp. |

| pRW3245 | (CTG)100 | Pure | + | Stabilized, exp. |

| pRW3246 | (CTG)100 | Pure | − | Stabilized |

| Dinucleotide repeats | ||||

| p(TC)37 | (TC)37 | Pure | + | Stabilized |

| p(TC)37(−) | (TC)37 | Pure | − | Stabilized |

| p(CA)30 | (CA)30 | Pure | + | No effect |

| p(CA)30(−) | (CA)30 | Pure | − | Stabilized |

| pUC(GC)13 | (GC)13 | Pure | NA | Stabilized, exp. |

| Minisatellite | ||||

| p∝3′HVR.64 (AACAGCGACACGGGGGG)228 | Homogenous | + | Destabilized | |

| Immunological centromeric facial abnormalities | ||||

| pHY10L/DYZ1 | (TTCC/GA)713 | Homogenous | + | No effect |

| pHY10R/DYZ1 | (TTCC/GA)713 | Homogenous | − | No effect |

Characteristics of unstable sequences. The plasmid name, sequence of the repeat units, and the total number of repeats are indicated. The purity of the repeat configuration is also indicated. For the fragile X (FRAXA) clones, the + indicates an AGG interruption (Pearson et al. 1998). The α3′HVR repeat is highly homogenous, with some repeat units differing at the 3′ end (Jarman et al. 1986). Only the major repeat unit variants are shown for the DYZ1 repeat (Nakahori et al. 1986). The cloning orientation of the insert relative to the unidirectional plasmid replication origin is indicated by + and −, reflecting the stable and the unstable orientation, respectively, in bacteria. The repeat sequence shown represents the template strand for leading strand synthesis at the replication fork in the stable orientation (+). Both the pure (CGG)53 and the α3′HVR could be cloned in only one orientation (Jarman et al. 1986; Pearson et al. 1998). Because the sequence in both strands of the (GC)n repeat are identical, cloning orientation and hence replication direction was not relevant; NA refers to not applicable. The effects of in vivo methylation on sequence stability are summarized in the rightmost column. Stability was determined from more than five experiments for each sequence by product analysis after multiple controlled subculturings (for a representative example see Fig. 1). Stabilization refers to fewer deletion events and smaller sizes of deletion, whereas reduced stability refers to increased deletion events and larger deletion sizes. The “exp.” Indicates that methylation permitted the stable propagation of tract lengths larger than starting material, which may be expansion products (see text).

The direction of replication affects the genetic stability of (CGG)n repeats in bacteria (Samadashwily et al. 1997) and yeast (White et al. 1999). To determine whether the stabilizing effect of CpG methylation was altered by the direction of replication, we analyzed the stability of pFXA9 + 9 + 32(−), which has a repeat length and configuration identical to pFXA9 + 9 + 32 but is cloned in the opposite orientation (Table 1). In the absence of methylation, pFXA9 + 9 + 32(−) is extremely unstable, rapidly giving rise to large deletions (Fig. 1F, compare lane 5 with 3). The increased instability of pFXA9 + 9 + 32(−) relative to its sister pFXA9 + 9 + 32 is more striking in early subcultures but is also evident in the third subculture. In the presence of methylation, the pFXA9 + 9 + 32(−) repeat is stabilized, consistently showing fewer deletion events and tending to delete fewer repeats (losing ≤30 repeats) (Fig. 1F, compare lane 5 with 6). In this manner, methylation diminished the instability caused by the unfavorable direction of replication. The effect of methylation on the stabilization of two shorter pure repeats (CGG)20 and (CGG)21, replicated in opposite directions, yielded similar results, stabilizing the repeat and abolishing the destabilizing effect of replication direction (Fig. 1F, compare lanes 7–10). Thus, in this system in vivo CpG methylation correlated with stabilized the (CGG)n repeats, whereas in the absence of methylation the repeats showed a strong propensity to delete.

The altered genetic stability of repeats in all test plasmids was dependent on the presence of the SssI CpG methylase. Cotransformation of test plasmids with the pAIT2 vector (pACM184) without the SssI gene did not alter the genetic stability of any plasmids (not shown). Therefore, the modification of genetic stability must be attributable to the in vivo expression of the SssI CpG methylase and/or to the methylation status of the DNA. Because in vitro methylation of test plasmids before transformation did not alter their genetic stability when propagated in the absence of SssI methylase (not shown), the effects of methylation appear to be transmitted by ongoing in vivo methylation. The effects of methylation were specific to the cloned unstable elements, because copropagation of the vectors pUC19 and pBluescript, along with pAIT2, did not result in any insertions or deletions in their sequences (not shown).

CpG Methylation Mildly Stabilizes (CTG)n

The results described above indicate that the methylation status of the (CGG)n repeat in bacteria can alter its genetic stability. To understand whether methylation of adjacent sequences could affect the stability of repeats lacking methylatable CpG sequences, we extended our analysis to the unstable (CTG)n repeat of myotonic dystrophy (DM1). In humans, the stability of this repeat is sensitive to repeat length such that tracts >50 repeats are unstable. Within and between tissues of DM1 patients, the expanded repeats display length heterogeneity because of high levels of both expansions and deletions. Although (CTG)n does not contain the CpG methylase recognition site, some DM1 cells with large CTG expansions (≥1000–1830 repeats) were found to be hypermethylated at the CpG island 5′ of the CTG repeat (Steinbach et al. 1998). However, a contribution of methylation to DM1 CTG instability is not clear.

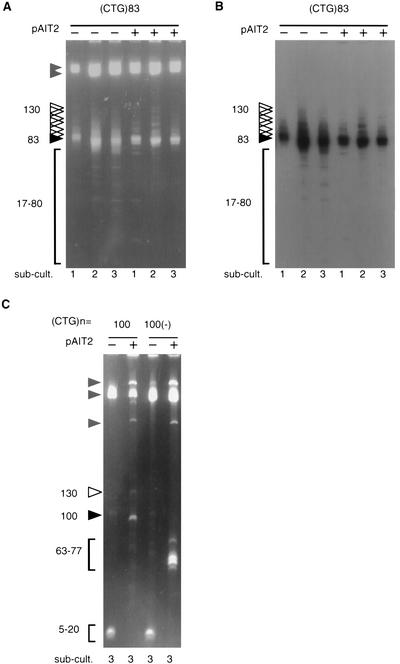

Cloned tracts of CTG repeats are unstable in bacteria, displaying predominantly deletions with only rare instances of expansion (Kang et al. 1995). To test the effect of CpG methylation on the genetic stability of (CTG)n repeats, we used a series of DM1 patient-derived clones (Pearson and Sinden 1996) in our in vivo methylation system (Table 1). The DM1 clones have repeats above and below the genetically unstable range. DM1 clones were propagated alone or in the presence of pAIT2, expressing SssI. A representative experiment is shown in Figure 2, in which DNAs observed by ethidium bromide (Fig. 2A) and changes in electrophoretic migration were confirmed as changes in repeat numbers by CTG-specific hybridization (Fig. 2B) and by sequencing (see below). Clones harboring (CTG)17 or (CTG)30 were not unstable; however, in the absence of methylation through the course of three subculturings, the (CTG)83 repeats yielded some products of large deletions and starting length material (Fig. 2, A and B). After culture in the presence of in vivo methylation, these deletion products were not observed, indicating that methylation stabilized the (CTG)n repeats by reducing the number of large deletion events. Furthermore, in vivo methylation led to a slight increase in the amount of distinct products larger than (CTG)83 evident as distinct bands. These larger products were also observed in the absence of methylation as a “smear” migrating slower than the starting (CTG)83; however, the amount of any given product is less in the absence of methylation. Thus, it seems unlikely that methylation induced expansion— a more plausible interpretation is that methylation enhanced the stable propagation of rare larger repeat tracts already present in the parental DNA preparation. Sequence analysis of products larger than the starting (CTG)83 revealed increases of integral numbers of pure repeats ranging from +27 to +111 repeats (not shown). Methylation also enhanced the propagation of products longer than starting (CTG)100 (see below). Both the reduction in large deletions and the stable propagation of larger repeats were evident only in cotransformations with the SssI methylase-expressing plasmid, pAIT2. These results indicate that in vivo CpG methylation of flanking sequences had a mild stabilizing effect on long (CTG)n repeats.

Figure 2.

Effect of methylation on the genetic stability of DM1 (CTG)n repeats. (A) The DM1 plasmid containing (CTG)83 repeats (Table 1) was propagated in E. coli in the absence or presence of the SssI methylase-expressing plasmid pAIT2. After three subculturings (each representing 25 generations), an aliquot of cells was harvested and plasmids isolated, restriction digested, and analyzed by 4% PAGE and ethidium bromide staining. To test for repeat length changes, DNAs were digested with SacI and PstI, which liberates the (CTG)n repeat-containing fragments from the DM1 clones, which are resolvable from pAIT2 and vector bands (indicated by brackets). The starting lengths of (CTG)n are indicated by filled arrowheads, products with larger-than-starting material lengths are indicated by open arrowheads, and (CTG)n deletion products are indicated by brackets. This gel is representative of five or more independent experiments. (B) To confirm that products were caused by changes in repeat numbers, the gel shown in panel A was electrotransferred to nylon membrane and hybridized to 32P-labeled (CTG)15 oligonucleotides and exposed for autoradiography. (C) Plasmids containing 100 CTG repeats cloned in the stable [(CTG)100] and unstable [(CTG)100(−)] orientations (Table 1) were subcultured three times in the absence or presence of methylation (± pAIT2) and (CTG)n repeat length changes analyzed as above. Although the deleterious effect of replication orientation on this long tract is not evident in the third subculturing (Bowater et al. 1996; Kang et al. 1995), the stabilizing effect of methylation is (see text); thus only the third subculturing is shown. Products are labeled as in panel A. This gel is representative of five or more independent experiments.

The direction of replication affects the genetic stability of (CTG)n repeats in bacteria (Kang et al. 1995; Samadashwily et al. 1997) and yeast (Freudenreich et al. 1998). To determine whether the stabilizing effect of CpG methylation was altered by the direction of replication, we analyzed the stability of two (CTG)100 tracts cloned in the stable [(CTG)100] and unstable [(CTG)100(−)] orientations. After three subculturings in the absence of methylation, both (CTG)100 and (CTG)100(−) tracts were extremely unstable, resulting in mostly large deletions leaving only 5 to 20 repeats and minimal amounts of starting-length material (Fig. 2C). The increased instability of long (CTG)100(−) relative to its sister (CTG)100 has previously been noted to occur earlier in subcultures (Kang et al. 1995; Bowater et al. 1996). Methylation stabilized the (CTG)100 clone such that the majority of the material was starting length displaying a minimum of deletion products and a minor population of larger (n = 130) products. The effect of methylation on the (CTG)100(−) was not as strong. Although deletion products predominated, the deleterious effect of replication direction was diminished to the extent that the magnitude of deletions was smaller, rarely losing ≥40 repeats, than in the absence of methylation (Fig. 2C). Thus, in this system in vivo methylation correlated with stabilized (CTG)n repeats, manifested by reducing large deletions and permitting stable propagation of longer repeats. Although the stabilizing effect of CpG methylation on (CTG)n was milder than that observed on (CGG)n repeats, these results indicate that the methylation status of adjacent sequences can affect the genetic stability of a contiguous sequence.

What was the density of CpG sites flanking the cloned CTG repeats? With the same parameters used to identify mammalian CpG islands (Gourdon et al. 1997; Brock et al. 1999), sequence analysis of the cloning vectors (including pBR322, pBluescript, pUC8, pUC19, and pSP64) revealed that each were highly enriched with CpG sites and contained from three to four CpG islands (227–1237 nt) in critical regions (Supplementary Fig. 1, available online at http://www.genome.org). In most cases, the CpG islands encompassed or flanked regions that were necessary for proper plasmid function (i.e., replication origins and promoters of antibiotic resistance genes). The methylation status of these vector CpG islands, which in our system are >90% methylated (Fig. 1A), may alter the genetic stability of the cloned unstable elements. However, we were unable to test the requirement of the plasmid-borne CpG islands in modifying repeat instability because their deletion impaired plasmid function. Notably, in the human context many of the unstable elements we have investigated, including the DM1 locus, are contained within or proximal to CpG islands (Gourdon et al. 1997; Brock et al. 1999). On the basis of this observation and the fact that flanking sequences must contribute to repeat instability (Richards et al. 1996), it has been suggested that the methylation status of these CpG islands may alter the genetic stability of adjacent repeats (Brock et al. 1999; Gourdon et al. 1997). Our results are in agreement with this notion.

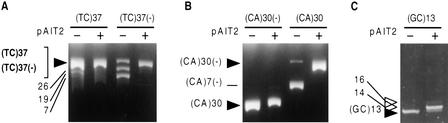

CpG Methylation Stabilizes Dinucleotide Repeats

Certain Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) tumors display both a methylator phenotype—site-specific hypermethylation, as well as a mutator phenotype—manifest as genome-wide microsatellite instabilities (Toyota et al. 1999). Although down-regulation of mismatch repair genes by promoter hypermethylation can indirectly enhance the mutation rates (Herman et al. 1998), it is not known if altered methylation directly contributes to the instability. For unclear reasons, different loci of dinucleotide repeat tracts with the same sequence display varying degrees of instability (Dietmaier et al. 1997). Using our in vivo methylation system, we tested the effect of CpG methylation on the genetic stability of plasmids containing (TC)37, (CA)30, or (GC)13, the latter containing the recognition site CpG (Table 1). These repeats display length instability in humans, yeast, and bacteria (Freund et al. 1989). In the absence of methylation, the stability of both (TC)37 and (CA)30 was sensitive to their orientation relative to the replication origin (Fig. 3, A and B) and over multiple subculturings tended to rapidly delete in the (−) orientation. Similarly, the (GC)13 plasmid also tended to delete (Fig. 3C). In the presence of in vivo methylation, each of the dinucleotides (TC)37, (TC)37(−), (CA)30, (CA)30(−), and (GC)13 were stabilized and displayed no deletion products, effectively eliminating the deleterious effect of replication orientation. Moreover, in the presence of methylation, the (GC)13 plasmid displayed products of expansion events (Fig. 3C). The stabilization (TC)n and (CA)n repeats by methylation, in addition to (CTG)n repeats, showed that methylation of adjacent sequences can alter the stability of contiguous sequences void of methylatable sites (Supplementary Fig. 1, available online at http://www.genome.org). From these results we conclude that in this system, in vivo CpG methylation correlated with stabilization of each of the dinucleotide repeats.

Figure 3.

Effect of methylation on the genetic stability of dinucleotide repeats. Plasmids containing the indicated dinucleotides (TC)37, (CA)30, and (GC)13, cloned in both orientations; plasmids (Table 1) were propagated in E. coli for three subculturings (each representing 25 generations) in the absence or presence of the SssI methylase plasmid. Cells were harvested and plasmids isolated, restriction digested, and analyzed by PAGE and ethidium bromide staining. The trend through the three subculturings is reflected by the final subculture; hence only the third subculturing is shown for each plasmid. The starting length of each repeat is indicated by filled arrowheads, slower migrating repeat expansion products are indicated by open arrowheads, and all other faster migrating DNAs are products of deletion events. (GC)n expansions are indicated by open arrowheads. For each experiment, repeat length changes of individual expansion and deletion products were confirmed by DNA sequencing. (A) (TC)37 and (TC)37(−) digested with BamHI/NdeI analyzed on 8% PAGE. (B) (CA)30 and (CA)30(−) digested with BamHI/HindIII analyzed on 8% PAGE. (Because of the opposite cloning orientation and the polylinker, the (CA)30 restriction fragments migrate faster than their sister (CA)30(−) restriction fragments. (C) (GC)13 digested with BamHI/HindIII analyzed on 20% PAGE. Gels in panels A, B, and C are representative of five or more independent experiments.

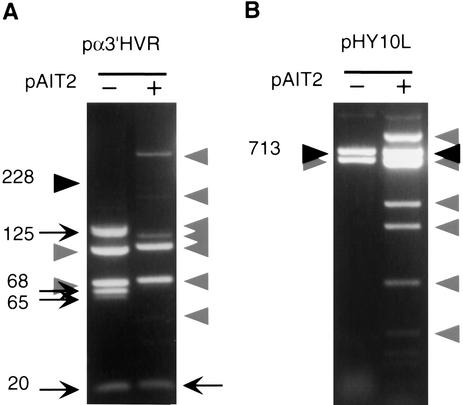

CpG Methylation Destabilizes a Minisatellite

The effect of CpG methylation on genetic stability may vary for longer repeat units. To understand whether methylation affected the stability of longer repeat units in bacteria, we extended our analysis to the hypervariable α3′HVR minisatellite (Jarman et al. 1986). The α3′HVR has a 17-base repeat unit containing two CpG sites (Table 1); the pα3′HVR.64 clone contains 228 tandem copies of this repeat (Jarman et al. 1986). In some human populations, this repeat is highly polymorphic with heterozygosities approaching 100%, and in this plasmid it is extremely unstable during propagation in bacteria (Jarman et al. 1986). Propagation of this plasmid in bacteria in the presence or absence of SssI had a striking effect on the stability of this repeat (Fig. 4A). Restriction digests of the starting material containing all 228 repeats resulted in a 4-kb band, but after subculture this fragment had deleted to several discrete lengths (Fig. 4A). In the presence of SssI methylase, this repeat was consistently more unstable, rapidly and completely deleting down to a single size of only 20 repeats (Fig. 4A). Thus, in this system, in vivo methylation reduced the stability of the α3′HVR repeat.

Figure 4.

Effect of methylation on the genetic stability of minisatellite and satellite 3 repeats. Plasmids pα3′HVR and pHY10L containing the minisatellite 3′ of the α1-globin gene and the DYZ1 satellite 3 repeat, respectively (Table 1), were propagated for three subculturings in E. coli in the absence or presence of the SssI methylase-expressing plasmid pAIT2. Cells were harvested and plasmids isolated, restriction digested, and analyzed by 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. The trend through the three subculturings is reflected by the final subculture; hence only the third subculturing is shown for each plasmid. (A) pα3′HVR digested with BamHI/HindIII/ScaI is suitable to test for repeat length changes as it liberates the minisatellite-containing fragments, each of which are resolvable from vector and pAIT2 and vector restriction fragments (indicated by shaded arrowheads). The starting length of the 228 repeats is indicated by a filled arrowhead; all other faster migrating DNAs are products of deletion events, indicated by arrows. (B) Plasmid pHY10L digested with SspI/HindIII is suitable to test for repeat length changes as it liberates the satellite-containing fragment, which is resolvable from pAIT2 and restriction fragments (indicated by shaded arrowheads). The starting length of the 713 repeats is indicated by a filled arrowhead. The sister clone pHY10R, which is identical but cloned in the opposite orientation, yielded identical results (not shown). Gels in panels A and B are representative of five or more independent experiments.

CpG Methylation Does Not Affect an Immunodeficiency, Centromeric Instability, and Facial Abnormalities (ICF)-Associated Repeat

Individuals with ICF have mutations within the de novo methylase gene DNMT3a and abnormal hypomethylation of various repeat sequences (Xu et al. 1999). The satellite 3 sequence DYZ1, which is normally hypomethylated in early development and methylated in differentiated tissues, remains aberrantly hypomethylated in patients with ICF (Jeanpierre et al. 1993; Xu et al. 1999). With our bacterial assay, we tested the effect of methylation on the stability of the DYZ1 repeat harbored in the pHY10 clones (Nakahori et al. 1986) (Table 1), which contain 713 repeats of the pentanucleotide base unit. In the absence or presence of in vivo methylation, the DYZ1 repeat was remarkably stable and was unaffected by the direction of replication (Fig. 4B). Thus, in this system, in vivo methylation did not affect the genetic stability of this long repeat tract.

CpG Methylation Stabilizes (CGG)n in a Primate System

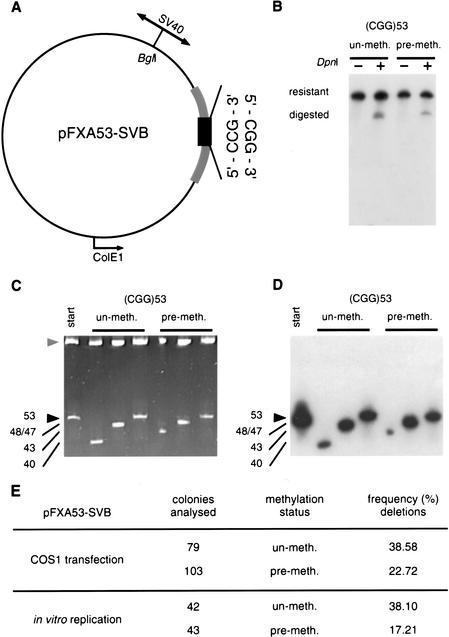

The stability of repeat tracts may be different in primate cells than in bacteria. To determine the effect of CpG methylation on repeat stability in primate cells, we used the SV40 viral replication system. We inserted the SV40 replication origin into the pFXA53 clone (Fig. 5A), allowing it to replicate either within primate (COS1) cells expressing T-antigen (TAg) (Cereghini and Yaniv 1984) or in vitro in the presence of primate cell extracts and TAg (Stillman 1986; Roberts and Kunkel 1988; Panigrahi et al. 2002). In the pFXA53-SVB template, the CGG repeat is replicated in the predictably unstable orientation with respect to primate SV40-directed replication and in the stable bacterial orientation (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Effect of methylation on the genetic stability of (CGG)n repeats in a primate system. (A) The replication origin-containing SphI-HindIII fragment of the SV40 virus was cloned into the BglI site of pFXA53 (Table 1). The circular plasmid is drawn to scale. The location of the SV40-ori relative to the CGG tract defined the direction of mammalian replication. (B) The similar efficiency of replication of premethylated (SssI) and unmethylated templates in transfected COS1 cells (48 hr) or in vitro was confirmed by DpnI-resistance. Shown is a Southern blot of post-transfection KpnI/SacI digested DNAs hybridized with a 32P-labeled (CGG)10 oligonucleotide. (C) Replication products were analyzed for their repeat length alterations. Transfected or in vitro replication products were digested with DpnI (only DNAs that are products of mammalian replication are resistant to DpnI). DpnI-resistant replication products were transformed into E. coli and DNAs were prepared from individual bacterial colonies, each derived from an individual product of mammalian replication. DNAs were analyzed for repeat changes by acrylamide gel electrophoresis. (D) Changes were confirmed to be the result of alterations in repeat numbers by electrotransfer and hybridization with a 32P-labeled (CGG)10 oligonucleotide. Shown is a representative gel with three single-colony/individual replication products of methylated (+) and unmethylated (−) templates. Individual products were also analyzed by DNA sequencing. (E) Frequencies of deletion events were scored. Background was subtracted from the mammalian mutation frequencies essentially as described (Panigrahi et al. 2002) (see Methods for details). Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference between the stability of methylated and unmethylated templates either in living cells (P = .014, χ2) or in vitro (P = .00088, χ2). These results are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Premethylated (SssI) and unmethylated forms of pFXA53-SVB were transfected into primate cells and replicated as chromatin-assembled templates (Cereghini and Yaniv 1984). As determined by DpnI resistance (Fig. 5B), the premethylated pFXA53-SVB replicated with similar efficiency as its unmethylated form, confirming previous findings (Graessmann et al. 1983). Mutation analysis (Fig. 5, C and D) of the mammalian-replicated DNAs revealed that the (CGG)n tract in the methylated pFXA53-SVB was significantly more stable, experiencing fewer deletion events relative to the unmethylated form (P = .014, χ2) (Fig. 5E).

Methylated DNAs, including the FRAXA CGG repeats, are known to form different chromatin structures (Wang and Griffith 1996; Bird and Wolffe 1999; Coffee et al. 1999). To investigate whether the difference in genetic stability between the methylated and unmethylated templates was attributable to chromatin packaging, we replicated the DNAs in vitro in the presence of cytoplasmic extracts and TAg, in which chromatin does not form (Stillman 1986). Similar to the transfection results, the stability of the in vitro replicated (CGG)n tract in the methylated template was more stable compared with its unmethylated form (P = .00088, χ2) (Fig. 5E). Thus, in this system it seems unlikely that the effect of methylation on (CGG)n stability is mediated by chromatin packaging. This finding cannot exclude the contribution of a methyl-specific protein factor (Bird and Wolffe 1999).

DISCUSSION

We have used bacterial and primate cell systems to directly investigate the effect of methylation on the genetic stability of unstable di-, tri, penta- and minisatellite repeat sequences. Our results indicate that there is a basic mechanism that we can learn here: The genetic stability of various repeat sequences can be modified by the CpG methylation status both within and near the unstable sequence. As summarized in Table 1, depending on the sequence, methylation significantly increased or reduced genetic stability. Of the seven repeat sequences investigated, methylation stabilized five, destabilized one, and had no effect on another. Thus, although methylation generally stabilized repeat tracts, its influence depended on the sequence of the repeat. Our results provide strong support for the notion that altered CpG methylation status can modify the genetic stability of cloned repeated sequences. Thus, in addition to repeat sequence, tract length, tract purity, and replication direction, one must now consider regional CpG methylation as a determinant of genetic instability.

In vivo CpG methylation in bacteria may have technical applications. The general increased stability of cloned unstable elements in bacteria expressing SssI methylase indicated an application of in vivo CpG methylation for the isolation and stable propagation of DNA sequences that have been recalcitrant to isolation and/or analyses because of their extreme instability. This may facilitate the identification of genomic “blind-spots” (Bork and Copley 2001; Eichler 2001). Furthermore, the production of novel recombinant clones (through deletions and expansions) might be facilitated by taking advantage of the altered genetic stabilities caused by the presence or absence of ongoing CpG methylation.

The mechanism through which CpG methylation alters repeat stability is complex and its transmission is likely to involve numerous factors, including DNA structure and proteins (Bird and Wolffe 1999). In a FRAXA methylation mosaic, multiple differentiated tissues displayed either CGG length heterogeneity or distinct length products; the apparent instability or stability was tightly correlated with methylation status (Taylor et al. 1999). In cultured primary human fibroblasts derived from methylation mosaics, CGG instability depended on the lack of methylation (Burman et al. 1999; Salat et al. 2000). However, in one study (Burman et al. 1999) but not another (Wohrle et al. 2001), CGG instability in a transferred human chromosome in human–mouse hybrid cells was dependent on cell differentiation and not methylation. Together, these results indicate that methylation can affect CGG stability in only specific tissues/differentiation states, indicating a requirement for trans-acting factors, possibly a protein that is sensitive to the methyl status of the DNA (Muller-Hartmann et al. 2000). This conclusion is in agreement with proposals indicating that methylation modifies repeat stability through processes of methylation-sensitive DNA repair (Wohrle et al. 1995; Smith and Crocitto 1999). Such repair processes may be active in only specific tissues and/or during specific stages of development.

CpG methylation of a sequence may affect its propensity to form mutagenic intermediates. The comparable results obtained in bacterial and primate cells may indicate a general effect of CpG methylation on genetic stability and shed light on one possible mechanism through which methylation may modify repeat stability. The similar effect of methylation on genetic stability in such evolutionarily divergent cells, which have different proteins for methylation, replication, repair, and chromatin packaging, indicates that the effect of methylation may be transmitted through a factor that is common to each system: the methylation status of the DNA. The biophysical attributes of the methylated DNA, specifically its increased melting temperature (Zacharias 1993), may affect both the rate and fidelity of DNA polymerase synthesis. Methylation status may favor or disfavor the formation of mutagenic intermediates such as slipped structures during replication. Notably, DNA methylation can enhance or impair the ability of certain sequences to form non-B-DNA structures such as melted DNA, cruciforms, Z-DNA, and triplex-DNA (Hodges-Garcia and Hagerman 1992). The effects of methylation on DNA structure are both sequence- and context-dependent and its effects can extend beyond the methylated region (Hodges-Garcia and Hagerman 1992; Zacharias 1993); the latter may explain the modified genetic stability of unmethylatable sequences flanked by methylated DNAs. Long-range effects of a neighboring sequence on the structural and biological properties of another contiguous sequence have previously been reported (Wang and Giaever 1988). The nucleotide composition of one segment can strongly influence the extrusion of cruciforms (Sullivan and Lilley 1986), Z-DNA (Rajagopalan et al. 1990), triplex DNA (Kang et al. 1992), or thermal melting (Burd et al. 1975) of remote DNA segments. This transmission along the DNA, or “telestability” (Burd et al. 1975), can occur over distances as long as 100 bp (Sullivan and Lilley 1986). The idea that methylation within or around an unstable element may influence its ability to form mutagenic intermediates is attractive. This mechanism is in agreement with current models of repeat instability whereby altered in vivo DNA replication of repeat sequences may be mediated by unusual DNA structures (Samadashwily et al. 1997), which are known to alter genetic instability (Freund et al. 1989). Thus, both cis- and trans-acting factors may contribute to the methylation-mediated modification of repeat instability. Although other explanations are possible, it is clear that we have observed striking association of methylation status with differences in the stability of various repeat sequences in bacterial and primate cells. The degree to which the results from our model systems can be extrapolated to the associated instabilities in humans is unknown; however, our results highlight this as a promising area for future research.

The epigenetic effect of altered CpG methylation may act as a signal for a mutation “hot spot.” We propose that methylation status may contribute to locus-specific repeat instabilities. Rather than solely the result of trans-acting factors such as repair/recombination proteins, which have genome-wide effects on genetic stability, one might expect that cis-acting factors (such as sequence) or epigenetic alterations could predispose to site-specific instability. This may involve the interaction of sequence- and methyl-sensitive proteins (Muller-Hartmann et al. 2000). Such epigenetic modification of mutation disposition would have broad implications for genome stability.

METHODS

E. coli-Based In Vivo Methylation System

The SssI expressing plasmid, pAIT2, contains a p15 replication origin and resistance to kanamycin, whereas each of the test plasmids used in this study contain a ColE1 replication origin and resistance to ampicillin. The use of different replication origins and the two selection systems obviates plasmid incompatibility and permits selective growth of cells containing both or only one of the two plasmids. Plasmids harboring unstable elements were transformed or cotransformed with pAIT2 into E. coli and propagated as described (Bowater et al. 1996). Transformations were performed with an excess number of cells to DNA molecules favoring transformation of a single cell by an individual plasmid, or plasmids in the case of cotransformations, using 10 ng of DNA with 100 μL of competent cells. Midway through this study we found that competent cells containing the pAIT2 plasmid could be transformed by test plasmids without altering the results. Because expression of the SssI methylase had a minimal effect on the growth rate of the cells, as previously observed (Renbaum et al. 1990), cultures were rigorously maintained in log phase (monitored by optical density [O.D.600 = 1.0]). Subculturing was performed by inoculating fresh media with a 107 dilution of the previous culture. Each subculturing represented 25 generations. As the number of generations giving rise to plasmid DNA was equivalent in the presence or the absence of in vivo methylation, a direct comparison of stability was possible. The yield of plasmid per generation was similar whether cultured in the presence or absence of the methylase. After each subculturing, the remaining cells were harvested and plasmids purified by Magic Mini Preparation (PROMEGA) with the inclusion of a proteinase K digestion (1 μL of 20 mg/mL). The genetic stability of test clones was determined by performing a suitable restriction digestion and analyzing the length of the repeat-containing fragment by PAGE or agarose gel electrophoresis. The CpG methylation status of all test plasmids that were cotransformed with pAIT2 were monitored by methyl-sensitive restriction digestion (AciI and HpaII) and found to be almost fully methylated at every CpG site (>90%, Fig. 1A; see also Renbaum et al. 1990). All experiments presented were performed with both ER1821 and XL1-Blue MR; each was deficient in the methyl-specific restriction systems mcrA, mcrCB, and mrr. The results were similar between bacterial strains.

SV40-Based Replication in Primate Cells and In Vitro

COS1 monkey cells expressing T-antigen (Cereghini and Yaniv 1984) were transfected with 5 μg of plasmid DNA according to the manufacturers protocol (STRATAGENE). Episomal DNAs were extracted 48 hr later. SV40 T-antigen dependent in vitro replication was performed essentially as described (Roberts and Kunkel 1988; Panigrahi et al. 2002) with 150 ng of DNA template, HeLa cell cytoplasmic extracts, 1μg TAg (CHIMERX), creatine phosphate (ROCHE; 40 mM), and creatine kinase (ROCHE; 100 μg/μL), and final concentrations of dATP, dGTP, dTTP, and dCTP (100 μM), CTP, GTP, and UTP (200 μM), ATP (4 mM). Reactions were incubated for 4 hr at 37°C and replication products purified.

Mutation Analysis of Mammalian Replicated DNAs

Mutation analysis was performed as described in detail (Panigrahi et al. 2002). Briefly, transfection or in vitro replication products were digested with DpnI. DpnI-resistant replication products were transformed into E. coli and DNAs were prepared from individual bacterial colonies, each derived from an individual product of mammalian replication. DNAs were analyzed for repeat changes by gel electrophoresis (a representative example is shown in Fig. 5, C and D). Analysis of 40 to 100 colonies yielded mammalian frequencies of expansions and deletions (Fig. 5E). Precautions were taken to minimize instability introduced by the bacteria during retransformation: (1) In the SV40 construct, the trinucleotide repeats were cloned in the stable ColE1 bacterial orientation; and (2) the number of bacterial cell generations required for mini-plasmid preparation is 4 to 6, far fewer than the 25 to 75 required to observe bacterial induced repeat instability (see Fig. 1A). Under these conditions, the background instability contributed by bacteria was minimal. The frequency of deletions generated by mammalian replication was calculated by subtracting the background frequency observed in bacteria, as described (Panigrahi et al. 2002). The background level was determined by bacterial transformation of starting template DNA and analysis of single colonies (>60). For example, after mammalian replication, the frequency of deletion events was calculated as 38.58% = 48.10% (observed) – 9.52% (background bacterial deletions).

CpG Island Analysis

CpG island analysis of vector sequences (Supplementary Fig. 1 available online) was performed on CpGPlot using default parameters (Brock et al. 1999; Gourdon et al. 1997).

Acknowledgments

pAIT2, pACM184, and ER1821 were kindly provided by W.E. Jack (NEW ENGLAND BIOLABS). pHY10 clones were kindly provided by Y. Nakahori. pα3′HVR was kindly provided by L.W. Coggins, originally from A.R. Higgs. Plasmids containing (CA)30 and (TC)37, respectively, were kindly provided by B. Johnston, originally from F. Strauss and A. Efstratiadis, respectively. p(GC)13 was kindly provided by R.P. Fuchs and M. Bichara. We acknowledge R.P. Bowater for assisting us in the subculturing of E. coli. We thank B. Muskat and L. Zaifman (Hospital for Sick Children Bioinformatics Supercomputing Center) for CpG island analyses and Gagan Panigrahi for performing the in vitro replication reactions. We are also indebted to M. Buchwald, R. McInnes, L.-C. Tsui, S. Meyn, and our laboratory members for their constructive criticisms of the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR grant FRN-15462). C.E.P. is a CIHR Scholar and a Canadian Genetic Disease Network Scholar.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL cepearson@genet.sickkids.on.ca.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.74502. Article published online before print in July 2002.

REFERENCES

- Allingham-Hawkins DJ, Brown CA, Babul R, Chitayat D, Krekewich K, Humphries T, Ray PN, Teshima I E. Tissue-specific methylation differences and cognitive function in fragile X premutation females. Am J Med Genet. 1996;64:329–333. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960809)64:2<329::AID-AJMG19>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anvret M, Ahlberg G, Grandell U, Hedberg B, Johnson K, Edstrom L. Larger expansions of the CTG repeat in muscle compared to lymphocytes from patients with myotonic dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:1397–1400. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.9.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird AP, Wolffe AP. Methylation-induced repression—belts, braces, and chromatin. Cell. 1999;99:451–454. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork P, Copley R. The draft sequences: Filling in the gaps. Nature. 2001;409:818–820. doi: 10.1038/35057274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowater RP, Rosche WA, Jaworski A, Sinden RR, Wells RD. Relationship between Escherichia coli growth and deletions of CTG.CAG triplet repeats in plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:82–96. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock GJ, Anderson NH, Monckton DG. Cis-acting modifiers of expanded CAG/CTG triplet repeat expandability: Associations with flanking GC content and proximity to CpG islands. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WT, Nolin SL. Apparent FMR1 allele instability in non-fragile X males. Genet Test. 2000;4:241–242. doi: 10.1089/10906570050501443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd JF, Wartell RM, Dodgson JB, Wells RD. Transmission of stability (telestability) in deoxyribonucleic acid. Physical and enzymatic studies on the duplex block polymer d(C15A15) - d(T15G15) J Biol Chem. 1975;250:5109–5113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman RW, Popovich BW, Jacky PB, Turker MS. Fully expanded FMR1 CGG repeats exhibit a length- and differentiation-dependent instability in cell hybrids that is independent of DNA methylation. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2293–2302. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.12.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereghini S, Yaniv M. Assembly of transfected DNA into chromatin: Structural changes in the origin-promoter-enhancer region upon replication. Embo J. 1984;3:1243–1253. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01959.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RZ, Pettersson U, Beard C, Jackson-Grusby L, Jaenisch R. DNA hypomethylation leads to elevated mutation rates. Nature. 1998;395:89–93. doi: 10.1038/25779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffee B, Zhang F, Warren ST, Reines D. Acetylated histones are associated with FMR1 in normal but not fragile X-syndrome cells. Nat Genet. 1999;22:98–101. doi: 10.1038/8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings CJ, Zoghbi HY. Fourteen and counting: Unraveling trinucleotide repeat diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:909–916. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.6.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Chapelle A, Peltomaki P. Genetics of hereditary colon cancer. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:329–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.001553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietmaier W, Wallinger S, Bocker T, Kullmann F, Fishel R, Ruschoff J. Diagnostic microsatellite instability: Definition and correlation with mismatch repair protein expression. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4749–4756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerfler W. A new concept in (adenoviral) oncogenesis: Integration of foreign DNA and its consequences. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1288:F79–99. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler EE. Segmental duplications: What's missing, misassigned, and misassembled—and should we really care? Genome Res. 2001;11:653–656. doi: 10.1101/gr.188901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenreich CH, Kantrow SM, Zakian VA. Expansion and length-dependent fragility of CTG repeats in yeast. Science. 1998;279:853–856. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund AM, Bichara M, Fuchs RP. Z-DNA-forming sequences are spontaneous deletion hot spots. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86:7465–7469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genc B, Muller-Hartmann H, Zeschnigk M, Deissler H, Schmitz B, Majewski F, von Gontard A, Doerfler W. Methylation mosaicism of 5′-(CGG)(n)-3′ repeats in fragile X, premutation and normal individuals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2141–2152. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.10.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourdon G, Dessen P, Lia AS, Junien C, Hofmann-Radvanyi H. Intriguing association between disease associated unstable trinucleotide repeat and CpG island. Ann Genet. 1997;40:73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graessmann M, Graessmann A, Wagner H, Werner E, Simon D. Complete DNA methylation does not prevent polyoma and simian virus 40 virus early gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1983;80:6470–6474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.21.6470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaf T. The effects of 5-azacytidine and 5-azadeoxycytidine on chromosome structure and function: Implications for methylation-associated cellular processes. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;65:19–46. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helderman-van den Enden AT, Maaswinkel-Mooij PD, Hoogendoorn E, Willemsen R, Maat-Kievit JA, Losekoot M, Oostra BA. Monozygotic twin brothers with the fragile X syndrome: Different CGG repeats and different mental capacities. J Med Genet. 1999;36:253–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JG, Umar A, Polyak K, Graff JR, Ahuja N, Issa JP, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Hamilton SR, Kinzler KW, et al. Incidence and functional consequences of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in colorectal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:6870–6875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst MC, White PJ. Cloned human FMR1 trinucleotide repeats exhibit a length- and orientation-dependent instability suggestive of in vivo lagging strand secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2353–2358. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.10.2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges-Garcia Y, Hagerman PJ. Cytosine methylation can induce local distortions in the structure of duplex DNA. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7595–7599. doi: 10.1021/bi00148a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman AP, Nicholls RD, Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB, Higgs DR. Molecular characterisation of a hypervariable region downstream of the human alpha-globin gene cluster. Embo J. 1986;5:1857–1863. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanpierre M, Turleau C, Aurias A, Prieur M, Ledeist F, Fischer A, Viegas-Pequignot E. An embryonic-like methylation pattern of classical satellite DNA is observed in ICF syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:731–735. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.6.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Wohlrab F, Wells RD. GC-rich flanking tracts decrease the kinetics of intramolecular DNA triplex formation. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19435–19442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Jaworski A, Ohshima K, Wells RD. Expansion and deletion of CTG repeats from human disease genes are determined by the direction of replication in E. coli. Nat Genet. 1995;10:213–218. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makos M, Nelkin BD, Reiter RE, Gnarra JR, Brooks J, Isaacs W, Linehan M, Baylin SB. Regional DNA hypermethylation at D17S5 precedes 17p structural changes in the progression of renal tumors. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2719–2722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malter HE, Iber JC, Willemsen R, de Graaff E, Tarleton JC, Leisti J, Warren ST, Oostra BA. Characterization of the full fragile X syndrome mutation in fetal gametes. Nat Genet. 1997;15:165–169. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorell L, Johnson K, Boucher CA, Baiget M. Somatic instability of the myotonic dystrophy (CTG)n repeat during human fetal development. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:877–880. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.6.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Hartmann H, Deissler H, Naumann F, Schmitz B, Schroer J, Doerfler W. The human 20-kDa 5′-(CGG)(n)-3′-binding protein is targeted to the nucleus and affects the activity of the FMR1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6447–6452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahori Y, Mitani K, Yamada M, Nakagome Y. A human Y-chromosome specific repeated DNA family (DYZ1) consists of a tandem array of pentanucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:7569–7580. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.19.7569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolin SL, Houck GE, Jr, Gargano AD, Blumstein H, Dobkin CS, Brown WT. FMR1 CGG-repeat instability in single sperm and lymphocytes of fragile-X premutation males. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:680–688. doi: 10.1086/302543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi GB, Cleary JD, Pearson CE. In vitro (CTG)(CAG) expansions and deletions by human cell extracts. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13926–13934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CE, Sinden RR. Alternative structures in duplex DNA formed within the trinucleotide repeats of the myotonic dystrophy and fragile X loci. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5041–5053. doi: 10.1021/bi9601013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CE, Eichler EE, Lorenzetti D, Kramer SF, Zoghbi HY, Nelson DL, Sinden RR. Interruptions in the triplet repeats of SCA1 and FRAXA reduce the propensity and complexity of slipped strand DNA (S-DNA) formation. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2701–2708. doi: 10.1021/bi972546c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan M, Rahmouni AR, Wells RD. Flanking AT-rich tracts cause a structural distortion in Z-DNA in plasmids. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17294–17299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razin A, Shemer R. DNA methylation in early development. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1751–1755. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.suppl_1.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renbaum P, Abrahamove D, Fainsod A, Wilson GG, Rottem S, Razin A. Cloning, characterization, and expression in Escherichia coli of the gene coding for the CpG DNA methylase from Spiroplasma sp. strain MQ1(M.SssI) Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1145–1152. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.5.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards RI, Crawford J, Narahara K, Mangelsdorf M, Friend K, Staples A, Denton M, Easteal S, Hori TA, Kondo I, et al. Dynamic mutation loci: Allele distributions in different populations. Ann Hum Genet. 1996;60:391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1996.tb00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JD, Kunkel TA. Fidelity of a human cell DNA replication complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:7064–7068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat U, Bardoni B, Wohrle D, Steinbach P. Increase of FMRP expression, raised levels of FMR1 mRNA, and clonal selection in proliferating cells with unmethylated fragile X repeat expansions: A clue to the sex bias in the transmission of full mutations? J Med Genet. 2000;37:842–850. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.11.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samadashwily GM, Raca G, Mirkin SM. Trinucleotide repeats affect DNA replication in vivo. Nat Genet. 1997;17:298–304. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M, Gellibolian R, Oostra BA, Wells RD. Cloning, characterization and properties of plasmids containing CGG triplet repeats from the FMR-1 gene. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:614–626. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS, Crocitto L. DNA methylation in eukaryotic chromosome stability revisited: DNA methyltransferase in the management of DNA conformation space. Mol Carcinog. 1999;26:1–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199909)26:1<1::aid-mc1>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach P, Glaser D, Vogel W, Wolf M, Schwemmle S. The DMPK gene of severely affected myotonic dystrophy patients is hypermethylated proximal to the largely expanded CTG repeat. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:278–285. doi: 10.1086/301711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman B. Chromatin assembly during SV40 DNA replication in vitro. Cell. 1986;45:555–565. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan KM, Lilley DM. A dominant influence of flanking sequences on a local structural transition in DNA. Cell. 1986;47:817–827. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symer DE, Bender J. Genomic stability. Hip-hopping out of control. Nature. 2001;411:146–147. doi: 10.1038/35075692. , 149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Longshore J, Zunich J, Steinbach P, Salat U, Taylor AK. Tissue-specific methylation differences in a fragile X premutation carrier. Clin Genet. 1999;55:346–351. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.550508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AK, Tassone F, Dyer PN, Hersch SM, Harris JB, Greenough WT, Hagerman RJ. Tissue heterogeneity of the FMR1 mutation in a high-functioning male with fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84:233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:8681–8686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzountzouris J, Kennedy D, Skuterud M, Connolly-Wilson M, Holden JJ, Lin CC, Mak-Tam E, Somerville MJ, Summers AM, Allingham-Hawkins DJ. Apparently unstable normal FMR1 alleles in nine developmentally delayed patients: Implications for molecular diagnosis of the fragile X syndrome. Genet Test. 2000;4:235–239. doi: 10.1089/10906570050501434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JC, Giaever GN. Action at a distance along a DNA. Science. 1988;240:300–304. doi: 10.1126/science.3281259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YH, Griffith J. Methylation of expanded CCG triplet repeat DNA from fragile X syndrome patients enhances nucleosome exclusion. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22937–22940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PJ, Borts RH, Hirst MC. Stability of the human fragile X (CGG)(n) triplet repeat array in Saccharomyces cerevisiae deficient in aspects of DNA metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5675–5684. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohrle D, Kennerknecht I, Wolf M, Enders H, Schwemmle S, Steinbach P. Heterogeneity of DM kinase repeat expansion in different fetal tissues and further expansion during cell proliferation in vitro: Evidence for a casual involvement of methyl-directed DNA mismatch repair in triplet repeat stability. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1147–1153. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.7.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohrle D, Salat U, Glaser D, Mucke J, Meisel-Stosiek M, Schindler D, Vogel W, Steinbach P. Unusual mutations in high functioning fragile X males: Apparent instability of expanded unmethylated CGG repeats. J Med Genet. 1998;35:103–111. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohrle D, Salat U, Hameister H, Vogel W, Steinbach P. Demethylation, reactivation, and destabilization of human fragile x full-mutation alleles in mouse embryocarcinoma cells. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:504–515. doi: 10.1086/322739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu GL, Bestor TH, Bourc'his D, Hsieh CL, Tommerup N, Bugge M, Hulten M, Qu X, Russo JJ, Viegas-Pequignot E. Chromosome instability and immunodeficiency syndrome caused by mutations in a DNA methyltransferase gene. Nature. 1999;402:187–191. doi: 10.1038/46052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder JA, Walsh CP, Bestor TH. Cytosine methylation and the ecology of intragenomic parasites. Trends Genet. 1997;13:335–340. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias W. Methylation of cytosine influences the DNA structure. EXS. 1993;64:27–38. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9118-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]