Abstract

Inclusion body myopathy is a progressive muscle disorder characterized by nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions and vacuolation of muscle fibers. Affected muscle fibers contain deposits of congophilic amyloid, amyloid-β immunoreactive filaments, and paired helical filaments, all of which are pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease in brain. Accumulations of amyloid-β and its precursor are thought to play important roles in the pathogenesis of both inclusion body myopathy and Alzheimer’s disease. Overexpression of mutant forms of β protein precursor in transgenic mice by neuron-specific promoters has been reported to cause amyloid deposits in the brain. Here we report that overexpression in transgenic mice of the signal plus 99-amino acid carboxyl-terminal sequences of β protein precursor, under the control of a cytomegalovirus enhancer/β-actin promoter, resulted in vacuolation and increasing accumulation of the 4-kd amyloid-β and the carboxyl-terminus in skeletal muscle fibers during aging. These deposits in transgenic muscle only rarely showed Congo red birefringence. Thus, overexpression of part of β protein precursor in transgenic mice led to development of some of the characteristic features of inclusion body myopathy. These mice may be a useful model of inclusion body myopathy, which shares a number of pathological markers with Alzheimer’s disease.

Inclusion body myositis (IBM) is the most common progressive muscle disease among people over 50 years of age and patients with IBM show muscle weakness in their arms and legs. 1,2 Muscle biopsies from patients with the sporadic form of IBM (s-IBM) reveal lymphocytic inflammation with abnormal muscle fibers containing vacuoles and characteristic filamentous inclusions in the cytoplasm and nuclei. 1,2 The term hereditary inclusion body myopathy (h-IBM) was introduced by Askanas and Engel 3,4 to describe inherited forms of IBM which are remarkably similar to s-IBM but usually lack the inflammation. 3-5 In both forms vacuolated muscle fibers contain congophilic amyloid and 6–10-nm filaments 6 and the latter can be further identified with antibodies against amyloid-β (Aβ). 7 Aβ, proteolytically produced from β protein precursor (βPP), 8 is a main constituent of amyloid plaques found in the brain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The vacuolated muscle fibers also contain twisted tubulofilament inclusions 15–21 nm in external diameter that are morphologically and immunocytochemically similar to paired helical filaments composing neurofibrillary tangles, another hallmark of AD. 9 Several other proteins, such as apolipoprotein E, 10 α1-antichymotrypsin, 11 ubiquitin, 12 and presenilin 1, 13 which accumulate in amyloid plaques and/or neurofibrillary tangles in AD, also have been identified in the inclusions of IBM. Thus, IBM shares several pathological features with AD.

The pathogenesis of IBM and AD is unknown. In IBM, abnormal accumulation of βPP epitopes including Aβ precedes congophilia and vacuole formation in skeletal muscle fibers. 14 Similarly, accretion of Aβ occurs before amyloid fibril formation and neuron loss in AD. 15,16 Overexpression of βPP in cultured human muscle fibers led to mitochondrial abnormalities, and formation of 6–10-nm amyloid fibrils and 15–21-nm tublofilaments. 17,18 Overexpression of mutant forms of βPP in transgenic mice by neuron-specific promoters caused AD-type Aβ deposits in the brain. 19,20 Thus, βPP and Aβ may have roles in the pathogenesis of both IBM and AD.

We previously reported on four founder lines of transgenic mice that overexpress the signal plus 99-amino acid carboxyl-terminal sequence (SβC) of βPP under the control of a cytomegalovirus enhancer/β-actin promoter. 21 Kawarabayashi et al 22 reported amyloid formation in the pancreas of transgenic mice bearing a transgene similar to ours. Because the levels of transgene expression were especially high in the skeletal muscle of our transgenic mice 21 and because overexpression of βPP in cultured muscle cells induced pathological changes similar to IBM, 17,18 we further investigated the skeletal muscle of our transgenic mice. We found Aβ-immunoreactive deposits in the skeletal muscle of line 13592 progeny derived from one of the four founder lines. The Aβ-immunoreactive deposits and apple green birefringence increased and the muscle fibers became vacuolated during aging of the 13592 mice.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic Mice

Establishment and propagation of the transgenic 13592 and 11430 lines of mice were described previously. 21 In brief, the SβC DNA construct was injected into fertilized eggs produced by mating F1s of C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice. All of the transgenic mice used in this study had been backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice more than 5 generations (B6.13592[N6 to N8] and B6.11430 [N8]; 23 for simplicity, these two lines are hereafter referred to as 13592 and 11430). Segregation of the transgene was determined by Southern blot analysis using cDNA for SβC as described previously. 21 C57BL/6J mice were used as controls. Mice were monitored for the presence of murine pathogens by a comprehensive battery of virus serologies, bacterial cultures, endoparasite and ectoparasite examinations, and histopathology of all major organs, as described previously. 24 Monitored mice were consistently negative for pathogens by these tests.

Northern and Western Blot Analyses

Levels of the mRNA and protein products expressed from the SβC transgene were determined by Northern and Western blot analyses, respectively. Two mice were euthanized at 3 months of age from each of the 13592, 11430, and non-transgenic C57BL/6J strains with intraperitoneal sodium pentobarbital injection for the collection of tissues. For Northern blotting, tissue RNA was extracted using Trizol reagents (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Twenty-five μg of total RNA from each tissue were electrophoresed thorough a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel, followed by capillary transfer to a nylon membrane. Northern blotting was performed using a radiolabeled human βPP cDNA probe (bp 901–2851) 8 as reported previously. 21 The relative levels of mRNA expression were determined by densitometric scanning (the Bio-Rad Model GS-670 densitometer and Molecular Analyst PC software). Equal loading of the RNA samples was confirmed by probing the stripped membranes with both β-actin and GAPDH cDNAs. For Western blotting, tissues were homogenized in 2× Laemmli buffer (1× = 62.5 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.001% bromophenol blue). Protein concentration was determined by Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Fifty μg of protein from each sample were applied to a 16.5% Tris-Tricine sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Western blotting was done using the 994B antibody and an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) as described previously. 21 The relative concentration of the protein was determined by densitometric scanning. The 994B antibody was developed against the 39 carboxyl-terminal residue of βPP. The carboxyl-terminal peptide was produced using the GST gene fusion system (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) and the purified peptide was used to immunize New Zealand White rabbits. The specificity of the antibody was confirmed by Western blot analysis of cells overexpressing βPP.

Immunocytochemistry and Congo Red Staining

Mice of three different strains were used for immunocytochemical and histochemical analyses. The 13592 mice included two aged 24 months, one aged 19 months, one aged 18 months, one aged 17 months, two aged 15 months, two aged 12 months, one aged 11 months, one aged 9 months, two aged 7 months, and three aged 6 months. The 11430 mice included one 25 months, two 24 months, and two 22 months of age. Four 15-month-old nontransgenic C57BL/6J mice comprised the third group. The mice were sacrificed by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital. The thigh muscles (quadriceps femoris, biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus) were removed, fixed in 10% formaldehyde: 90% alcohol, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm for immunocytochemistry and 10 μm for Congo red staining. The sections were then subjected to the avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase method to detect SβC and its derivatives using Vectastain ABC kit (Vector, Burlingame, CA). Endogenous peroxidase was eliminated by treatment with 3% H2O2 for 30 minutes after deparaffinization of the sections. After washing with distilled water, the sections were treated with 88% formic acid and rinsed with water and 0.1 mol/L Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (pH 7.4). The sections were blocked with 5–15% goat serum in TBS for 60 minutes at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies in 0.1 mol/L TBS containing 5–15% serum (goat serum for rabbit antibodies, horse serum for mouse monoclonal antibodies) for 16 hours at 4°C. The sections were rinsed in 0.1 mol/L TBS containing 1% serum and incubated with appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies for 60 minutes at room temperature. After washing, the sections were incubated with Vectastain ABC reagent for 60 minutes at room temperature. Peroxidase activity was detected by treatment with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Antibodies used for immunocytochemistry were 6E10 (1 μg IgG/ml; a mouse monoclonal antibody raised against amino acid 1–16 of Aβ, Senetek), 4G8 (0.5 μg IgG/ml; a mouse monoclonal antibody raised against amino acid residues 17–24 of Aβ; Senetek, Maryland Heights, MO), rabbit polyclonal anti-Aβ (1:200 working dilution; raised against Aβ, Zymed, San Francisco) and 994B (1:1,000). Tissues also were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for the evaluation of general histology and with Congo red for the detection of amyloid. 25 For each immunostain and Congo red stain, prefrontal cortex tissues from patients with Alzheimer’s disease were used as positive controls.

Extraction and Identification of Amyloid-β

Mice (one 19-month old 13592 and one 15-month old C57BL/6J) were anesthetized by pentobarbital and the posterior femoral muscles removed. The muscles were weighed and homogenized in 10× weight of 10% SDS. The homogenized samples were centrifuged at 100,000× g for 1 hour and the pellets were washed with 0.1 M TBS (pH 7.4). The pellets were resuspended in 89% formic acid using dounce homogenizers and then centrifuged at 100,000× g for 20 minutes. The supernatant was dried using a vacuum concentrator (SpeedVac, Savant). The dried samples were resuspended in SDS buffer (10% SDS, 25% glycerol, 300 mmol/L Tris, pH 6.8, and 100 mmol/L tricine). The samples were boiled for 5 minutes before loading onto a 16.5% Tris/tricine gel. The sample on each lane was derived from 50 mg (wet weight) of thigh muscle. SDS-PAGE and Western blotting were done as described above using the 994B and 6E10 antibodies.

Results

In backcrossing our transgenic mice to C57BL/6J, the segregation of the SβC transgene was verified by Southern blot analysis. The 13592 and 11430 mice had approximately five and three copies of the transgene, respectively. 21 The 13592 mice were distinct from 11430 mice in the Southern blot patterns (data not shown), indicating differences in chromosomal integration sites of the transgene.

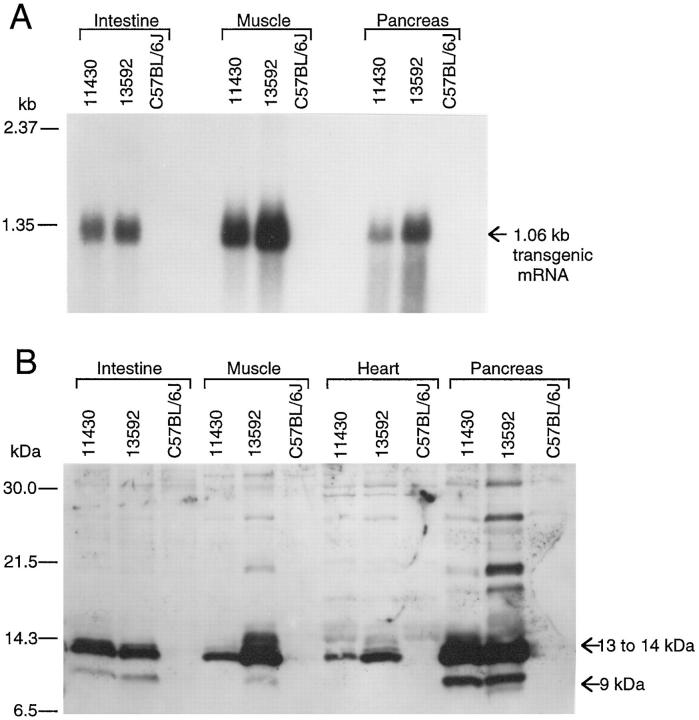

By Northern blotting (Figure 1A) ▶ , high levels of expression of mRNA with the expected size, 1.06 kb, from the SβC transgene were consistently observed in thigh muscles, pancreases, and small intestines of 13592 and 11430 mice. The levels of SβC mRNA in the thigh muscles of 13592 mice were approximately 3 times higher than those in 11430 mice (Figure 1A) ▶ . In contrast, there was little to no difference between the 13592 and 11430 mice in levels of the SβC mRNA in intestine.

Figure 1.

High levels of SβC transgene expression in the thigh muscle of 3-month-old 13592 mice. Northern and Western blotting analyses were performed to determine levels of SβC transgene expression in various tissues of 13592 and 11430 mice. For comparison, nontransgenic C57BL/6J mice were also used. A: The levels of the SβC mRNA in the tissues (intestine, muscle, and panaceas) from 13592 mice are higher than those from 11430 mice with the highest level of expression seen in the thigh muscle. Endogenous mRNA for mouse βPP (2.3 kb) is barely detectable at this washing and exposure condition. B: The 9- to 14-kd fragments produced from the SβC transgene are detected by the 994B antibody in the intestine, thigh muscle, heart, and pancreas (SDS-soluble proteins) from the 13592 and 11430 mice. The amount of 9- and 14-kd fragments in the thigh muscle from the 13592 mice is approximately 5× greater than that of the 11430 mice. The pancreas from the 13592 and 11430 mice have slightly higher levels of SβC protein products than the thigh muscle of the 13592 mice.

By Western blotting, using 16.5% Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE and the 994B antiserum, approximately 9- to 14-kd fragments of βPP were observed in the muscles, intestines, pancreases, and hearts of both 13592 and 11430 transgenic mice, but none was found in control C57BL/6J mice (Figure 1B) ▶ . The amount of the 9- to 14-kd fragments in 13592 muscle was approximately 5 times greater than that in 11430 muscle and approximately 3 times greater than that in 13592 intestine (Figure 1B) ▶ . However, there was little to no difference between the 13592 and 11430 transgenic mice in the amount of the carboxyl-terminal fragments in intestine. The amount of the 9- to 14-kd fragments in 13592 and 11430 pancreas were slightly greater than that in 13592 muscle (Figure 1B) ▶ . The brains, lungs, kidneys, and spleens of 13592 and 11430 mice expressed the 9- to 14-kd fragments much less than the muscles and hearts (data not shown). While the 9- to 14-kd fragments were visualized by the 994B antiserum, the 6E10 antibody failed to detect the 9-kd fragment but not the 13- to 14-kd fragments (data not shown), suggesting that the 9-kd fragment was produced by α-secretase cleavage.

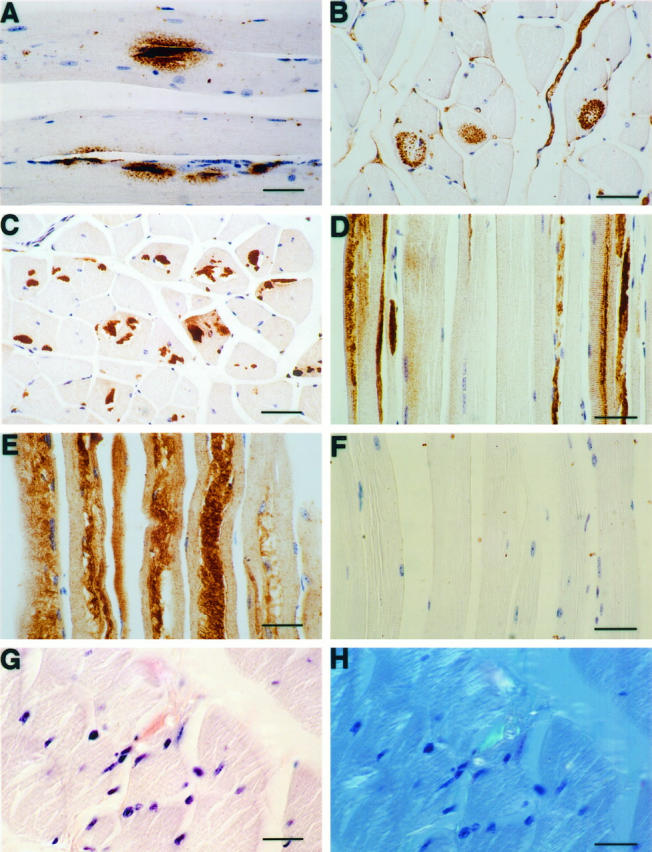

Immunocytochemical analyses were performed using the 994B antiserum and 3 other Aβ-specific antibodies (6E10, 4G8, and anti-Aβ). Aβ-immunoreactive granular deposits in thigh muscle from 13592 mice occurred in different patterns and increased during aging, although the number and size of the deposits varied between mice. At the younger age of 7 to 16 months, there were small (<2 μm) immunoreactive patches located in the subsarcolemmal zone and much larger (10–100 μm long) zones of granular immunoreactivity located centrally in fibers (Figure 2, A and B) ▶ . The three Aβ-specific antibodies revealed similar staining patterns in 13592 muscles. However, the granular deposits were not immunoreactive to the 994B antiserum, suggesting that the deposits consisted of Aβ proteolytically derived from SβC. In 18-, 19-, and 24-month-old 13592 mice, the Aβ-immunoreactive deposits appeared as longitudinal threads and columns (50–400 μm in length and 5–40 μm in diameter) in the sarcoplasm (Figure 2, C and D) ▶ ▶ . Affected areas of fibers were often accompanied by vacuoles (Figure 2, C, D, and E) ▶ . In contrast to smaller granular deposits seen in 13592 mice younger than 16 months of age, the thread-like and columnar deposits in 18- to 24-month-old 13592 mice were strongly immunoreactive to 994B antiserum (Figure 2E) ▶ . All seven 13592 mice older than 12 months had Aβ-immunoreactive deposits in thigh muscle compared to only three of nine 13592 mice (33%) younger than 13 months (Table 1) ▶ . The Aβ-immunoreactive deposits in 13592 mice increased in size and number during aging and all three 13592 mice older than 18 months developed Aβ-immunoreactive deposits with vacuoles (Figure 2, C–E) ▶ . All the immunoreactions described above were abolished when the primary antibodies were replaced by control sera (data not shown). A small portion (1% or less) of the Aβ-immunoreactive thread-like or columnar deposits was positive for Congo red staining, giving apple green birefringence when examined with polarization optics (Figure 2, G and H) ▶ , indicating amyloid fibril formation in the skeletal muscles of 13592 mice.

Figure 2.

Aβ-immunoreactive and Congo red-positive deposits in the thigh muscle of 13592 transgenic mice. The thigh muscles of 13592 and 11430 transgenic mice were stained with various antibodies using the avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase method. A: Aβ-immunoreactive granular deposits (10–100 μm) surrounded by much smaller granular deposits (<2 μm) in the posterior femoral muscle from a 7-month-old 13592 mouse, detected by the anti-Aβ antibody. B: Aβ-immunoreactive granular deposits in a cross section of the posterior femoral muscle of a 16-month-old 13592 mouse, detected by the 4G8 antibody. C and D: Aβ-immunoreactive deposits appears as threads and columns in the quadriceps muscle of a 24-month-old 13592 mouse, detected by the 4G8 antibody. E: The thread-like/columnar deposits react strongly with the 994B antibody in the posterior femoral muscle of a 24-month-old 13592 mouse. F: The posterior femoral muscle of a 24-month-old 11430 mouse is not immunoreactive to the 4G8 antibody. G and H: The posterior femoral muscle of a 24-month-old 13592 mouse was stained with Congo red. The section is observed under a regular light in G. Only a few deposits immunoreactive to Aβ antibodies show apple green birefringence under a polarized light in H. Scale bars, 49 μm, 43 μm (E and F), and 28 μm (G and H).

Table 1.

Aβ-Immunoreactive Deposits in Thigh Muscle of 13592 Mice

| Age (months) | 6 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 15 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 24 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of 13592 mice examined | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 16 |

| with Aβ-deposits | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| without Aβ-deposits | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

All four antibodies (994B, 4G8, 6E10, and anti-Aβ) failed to detect any deposits in the thigh muscles of 11430 mice up to 25 months of age or C57BL/6J mice up to 15 months (Figure 2) ▶ .

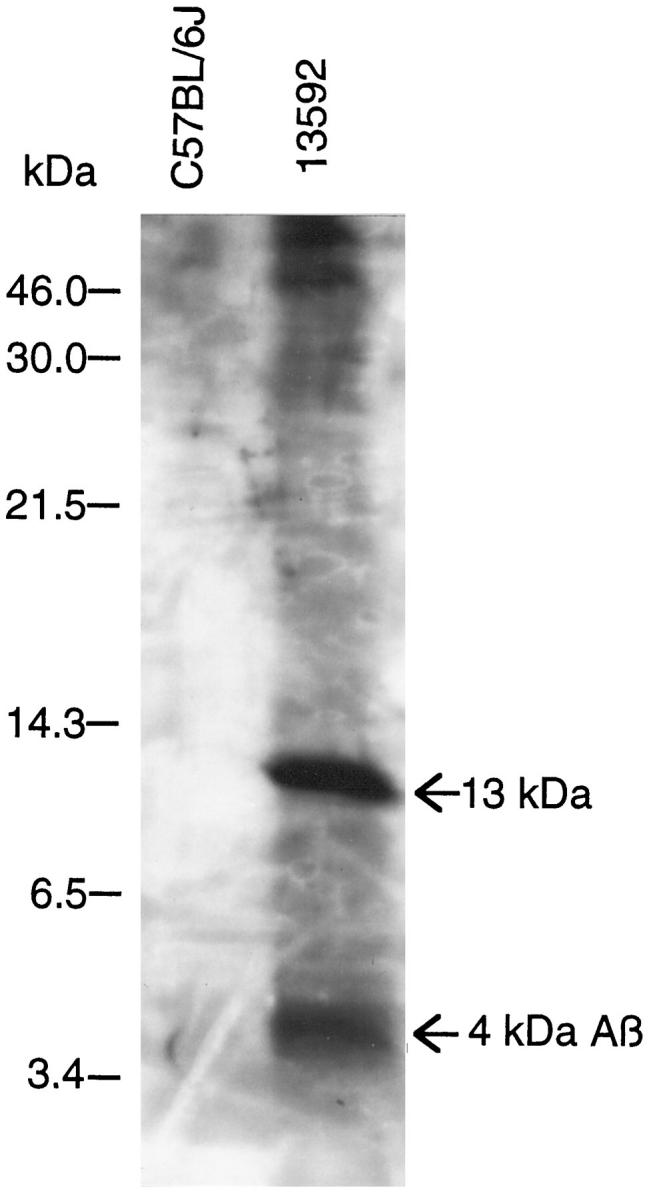

Since Aβ amyloid fibrils in AD brain are insoluble in SDS but soluble in formic acid, we extracted a formic acid soluble/SDS insoluble fraction from the thigh muscle of a 19-month-old 13592 mouse and analyzed the extract by Western blotting. One 4-kd fragment, one fragment of ∼13 kd, and fragments greater than 46 kd were visualized using the 6E10 antibody (Figure 3) ▶ . The 994B antiserum detected the ∼13-kd fragment but not the 4-kd fragment (data not shown). The SDS-soluble fraction of the same skeletal muscle contained the 13- to 14-kd fragments visualized by both 6E10 and 994B antibodies but neither 6E10 nor 994B antibodies detected the 4-kd fragment in the SDS-soluble fraction (data not shown). No comparable fragments were found in a nontransgenic 15-month-old C57BL/6J mouse (Figure 3) ▶ . These results indicate that the 4-kDa and 13-kDa fragment are Aβ and the 99-amino acid carboxyl-terminus of βPP, respectively.

Figure 3.

The 4-kd fragment immunoreactive to Aβ antibody in the SDS-insoluble/formic acid-soluble fraction from the thigh muscle of a 15-month-old 13592 mouse. The precipitates of the thigh muscle in 10% SDS were solubilized in 89% formic acid. The solubilized protein is visualized by the 6E10 antibody after separating the protein by 16.5% Tris-tricine SDS-PAGE. Each lane corresponds to 50 mg (wet weight) of the thigh muscle.

Discussion

Two lines of transgenic mice overexpressing the SβC transgene were studied. Only one of the lines (13592) consistently developed Aβ-immunoreactive deposits within the skeletal muscle fibers after 6 to 12 months of age. The muscle fibers with Aβ-immunoreactive deposits increased and became vacuolated with age. Only a few deposits showed Congo red birefringence. A SDS insoluble/formic acid soluble fraction from the muscle fibers contained both the 4-kd Aβ and the 13-kd carboxyl-terminal fragment of βPP.

The etiology of IBM is unknown. Suggested causative mechanisms include abnormal βPP metabolism, altered immune function, myonuclear alterations, mitochondrial abnormalities, inheritance, and viral infection. 1,2,26 Because the level of SβC transgene expression in 13592 muscle was much higher (∼threefold for mRNA and ∼fivefold for protein) than that in 11430 muscle and because overexpression of βPP induced Aβ-immunoreactive deposits and vacuoles in cultured muscle cells, 17,18 it is more likely that the observed muscular changes in 13592 mice were caused by overexpression of SβC than by altered endogenous gene expression by integration of the SβC. This suggests that SβC may play an important role in the etiology of IBM. It also is possible that the differences in genetic background between 13592 and 11430 mice influenced development of amyloid deposition in skeletal muscle in some manner, such as the reported genetic predisposition to development of AD associated with apolipoprotein E4 allele. 27,28 Association of IBM with the E4 allele is controversial 29-31 and remains to be clarified, however.

It is not clear why only a limited number of Aβ-immunoreactive deposits showed Congo red birefringence in spite of their strong immunoreactivity in older 13592 mice. Such an example in the brains of patients with AD is diffuse plaques that are Congo red-negative and immunocytochemically recognized by antibodies against Aβ. 32 Another possibility is that, as demonstrated for IBM, amyloid in skeletal muscle is difficult to detect by conventional Congo red staining methods. 33

Congophilic material in IBM is thought to consist of 6- to 10-nm filaments immunoreactive to antibodies against Aβ, although the true identity, molecular weight, and amino acid sequence of the filaments remain to be determined. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of the 4-kd Aβ-immunoreactive fragment in skeletal muscle. Because the 4-kd Aβ-immunoreactive fragment was found in a SDS insoluble/formic acid soluble fraction from a 13592 mouse and because 11430 and C57BL/6J mice did not have congophilic amyloid, Aβ-immunoreactive deposits, and the 4-kd Aβ-immunoreactive fragment, we speculate that Aβ is a primary constituent of the amyloid filaments in 13592 mice. These results support the hypothesis that the congophilic filaments in IBM are composed of Aβ.

Because these transgenic mice develop some of the characteristic features of inclusion body myopathy and because the main pathological features of IBM overlap with those of AD, these mice may provide a unique model system for investigation of the mechanisms engendering Aβ deposition in AD as well as in IBM.

Acknowledgments

We thank T.K. Hinds and K. Kamino for providing the 994B antibody; L.E. Harrell and G. Zhang for providing Alzheimer’s disease brain tissues through the Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the University of Alabama at Birmingham; and A. Smith, J. Hosmer, and M. Shackelford for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Ken-ichiro Fukuchi, Department of Comparative Medicine, Schools of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 402 Volker Hall, 1670 University Boulevard, Birmingham, AL 35294-0019. E-Mail: cmed037@uabdpo.dpo.uab.edu.

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (RR11105, RR07003, and AG12850).

References

- 1.Askanas V, Engel WK: New advances in the understanding of sporadic inclusion-body myositis and hereditary inclusion-body myopathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1995, 7:486-496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griggs RC, Askanas V, DiMauro S, Engel A, Karpati G, Mendell JR, Rowland LP: Inclusion body myositis and myopathies. Ann Neurol 1995, 38:705-713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Askanas V, Engel WK: New advances in inclusion-body myositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1993, 5:732-741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Askanas V: New developments in hereditary inclusion body myopathies. Ann Neurol 1997, 41:421-422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sivakumar K, Semino-Mora C, Dalakas MC: An inflammatory, familial, inclusion body myositis with autoimmune features and a phenotype identical to sporadic inclusion body myositis. Brain 1997, 120:653-661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendell JR, Sahenk Z, Gales T, Paul L: Amyloid filaments in inclusion body myositis: Novel findings provide insight into nature of filaments. Arch Neurol 1991, 48:1229-1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Askanas V, Alvarez RB, Engel WK: Abnormal accumulation of β-amyloid precursor epitopes in muscle fibers of inclusion body myositis. Ann Neurol 1993, 34:551-560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Muller-Hill B: The precursor of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature 1987, 352:733-736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Askanas V, Engel WK, Bilak M, Alvarez R, Selkoe DJ: Twisted tubulofilaments of inclusion body myositis muscle resemble paired helical filaments of Alzheimer brain and contain hyperphosphorylated tau. Am J Pathol 1994, 144:177-187 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Askanas V, Mirabella M, Engel WK, Alvarez RB, Weisgraber KH: Apolipoprotein E immunoreactive deposits in inclusion-body muscle diseases. Lancet 1994, 343:364-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilak M, Askanas V, Engel WK: Strong immunoreactivity of alpha 1-antichymotrypsin co-localizes with β-amyloid protein and ubiquitin in vacuolated muscle fibers of inclusion-body myositis. Acta Neuropathol 1993, 85:378-382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Askanas V, Serdaroglu P, Engel WK, Alvarez RB: Immunolocalization of ubiquitin in muscle biopsies of patients with inclusion body myositis and oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Neurosci Lett 1991, 130:73-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Askanas V, Engel WK, Yang CC, Alvarez RB, Lee VM, Wisniewski T: Light and electron microscopic immunolocalization of presenilin 1 in abnormal muscle fibers of patients with sporadic inclusion-body myositis and autosomal-recessive inclusion-body myopathy. Am J Pathol 1998, 152:889-895 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Askanas V, Engel WK, Alvarez RB: Light and electron microscopic localization of β-amyloid protein in muscle biopsies of patients with inclusion-body myositis. Am J Pathol 1992, 141:31-36 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selkoe DJ: Alzheimer’s disease: genotypes, phenotypes, and treatments. Science 1997, 275:630-631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Younkin SG: Evidence that Aβ 42 is the real culprit in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 1995, 37:287-288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Askanas V, McFerrin J, Baque S, Alvarez RB, Sarkozi E, Engel WK: Transfer of β-amyloid precursor protein gene using adenovirus vector causes mitochondrial abnormalities in cultured normal human muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:1314-1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Askanas V, McFerrin J, Alvarez RB, Baque S, Engel WK: βAPP gene transfer into cultured human muscle induces inclusion-body myositis aspects. Neuroreport 1997, 8:2155-2158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Games D, Adama D, Alessrini R, Barbour R, Berthelette P, Blackwell C, Carr T, Clemens T, Donaldson F, Gillesple T, Guido S, Hagopian K, Johnson-Wood K, Khan J, Lee M, Leibowitz P, Lieberburg I, Little S, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Montoya-Zavala M, Mucke L, Paganini L, Penniman E, Power M, Schenk D, Seubert P, Snyder B, Soriano F, Tan H, Vitale J, Wadsworth S, Wolozin B, Zhao J: Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F β-amyloid precursor protein. Nature 1995, 373:523-527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G: Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science 1996, 274:99-102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuchi K, Ho L, Younkin SG, Kunkel DD, Ogburn CE, Wegiel J, Wisniewski HM, LeBoeuf RC, Furlong CE, Deeb SS, Nochlin D, Sumi SM, Martin GM: High levels of β-amyloid protein in peripheral blood do not cause cerebral β-amyloidosis in transgenic mice. Am J Pathol 1996, 149:219-227 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawarabayashi T, Shoji M, Sato M, Sasaki A, Ho L, Eckman CB, Prada CM, Younkin SG, Kobayashi T, Tada N, Matsubara E, Iizuka T, Harigaya Y, Kasai K, Hirai S: Accumulation of β-amyloid fibrils in pancreas of transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging 1996, 17:215-222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silver LM: Mouse Genetics. 1995:pp 45-51 Oxford University Press, Oxford

- 24.Faulkner CB, Simecka JW, Davidson MK, Davis JK, Schoeb TR, Lindsey JR, Everson MP: Gene expression and production of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1, interleukin 6, and gamma interferon in C3H/HeN and C57BL/6N mice in acute Mycoplasma pulmonis disease. Infect Immun 1995, 63:4084-4090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luna LG: Manual of Histologic Staining Methods of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. 3rd ed. 1968, :p 153 McGraw-Hill, New York [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpenter S: Inclusion body myositis, a review. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1996, 55:1105-1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strittmatter WJ, Saunders AM, Schmechel D, Pericak-Vance M, Enghild J, Salvesen GS, Roses AD: Apolipoprotein E: high-avidity binding to β-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 1993, 90:1977-1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA: Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science 1993, 261:921-923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garlepp MJ, Tabarias H, van Bockxmeer FM, Zilko PJ, Laing B, Mastaglia FL: Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 in inclusion body myositis. Ann Neurol 1995, 38:957-959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrington CR, Anderson JR, Chan KK: Apolipoprotein E type epsilon 4 allele frequency is not increased in patients with sporadic inclusion-body myositis. Neurosci Lett 1995, 183:35-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Askanas V, Engel WK, Mirabella M, Weisgraber KH, Saunders AM, Roses AD, McFerrin J: Apolipoprotein E alleles in sporadic inclusion-body myositis and hereditary inclusion-body myopathy. Ann Neurol 1996, 40:264-265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamaguchi H, Hirai S, Morimatsu M, Shoji M, Harigaya Y: Diffuse type of senile plaques in the brains of Alzheimer-type dementia. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1988, 77:113-119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Askanas V, Engel WK, Alvarez RB: Enhanced detection of congo-red-positive amyloid deposits in muscle fibers of inclusion body myositis and brain of Alzheimer’s disease using fluorescence technique. Neurology 1993, 43:1265-1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]