Abstract

A DNA mutation detection protocol able to identify and characterize a previously unknown change in a given sequence in a rapid, efficient, sensitive, and inexpensive manner is required to take advantage of the resources now available to researchers through the genome sequencing projects. We have developed a method based on base-specific cleavage of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products and then separation of the fragments by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS), which can meet these criteria. Differences are seen as the presence, absence, or mass change of peaks corresponding to fragments affected by the base difference. This technique is shown through the detection of a polymorphism in the 3′ untranslated region of IL12p40 from a double-stranded PCR product, and the detection of a single nucleotide polymorphism between two mouse strains. The sensitivity of the technique can be increased with the use of postsource decay, which enables differentiation of two fragments of identical mass but different sequence. The level of specificity and the rapid sample analysis time lend this technique to the mass screening of individuals for sequence changes and, in combination with MS sequencing methods, could be used to facilitate rapid resequencing of DNA.

DNA mutation detection protocols fall into two major categories: those that are able to identify a previously unknown change in a given sequence and those designed to find known mutations. The first category includes methods such as single-strand conformational polymorphisms (Orita et al. 1989) and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (Lerman et al. 1986)—which are rapid, inexpensive, and useful as screening tools but lack sensitivity when used on longer DNA fragments—and methods such as Sanger sequencing (Orita et al. 1989; Hattori et al. 1993) and chemical cleavage (Cotton et al. 1988), which can characterize the changed base but are expensive and inefficient. Protocols identifying known mutations are now frequently non–gel based and can be automated to give high throughput. These include allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and specific oligonucleotide hybridization (Weber 1990). A rapid, non–gel based method for identifying unknown mutations is required. We describe an approach in which matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) and postsource decay (PSD) fragmentation (Nordhoff et al. 1996) are used to analyze the small oligonucleotides resulting from a complete base-specific cleavage reaction. Mutations appear as changes in mass peaks, and the sequence change can be deduced from the mass of the new peak, the disappearance of the wild-type peak, or sequence analysis of the PSD spectrum. The theoretical sensitivity of the technique approaches that of Sanger sequencing but eliminates the need for gel electrophoresis.

Most MS-based DNA sequencing protocols have focused on developing methods for adapting Sanger sequencing reactions or on protocols for base truncation of large DNA fragments. Although detection of DNA fragments up to 622 bp in length have been reported, large fragments cannot be accurately sized (Liu et al. 1995). To achieve the high mass accuracy required to describe point mutations, very small fragments are required. A technique is therefore needed to reproducibly fragment large DNA molecules. Although restriction endonuclease digestion has been used (Bai et al. 1994), the presence of restriction sites cannot be guaranteed, and the usually large fragments generated preclude accurate detection and characterization of base substitutions. We have developed a mutation detection method that exploits the mass accuracy of MALDI-TOF MS for short oligonucleotides but uses larger DNA fragments as substrates. We have named this method TOFS for tiny oligonucleotide fragment separation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The method we have developed uses a base-specific cleavage reaction to generate the set of all small oligonucleotides bounded by the base cleaved. These fragments are then separated based on mass by MALDI-TOF MS, thus generating a fingerprint of the DNA fragments in which each peak represents the mass of each small cleavage product. A different mass peak is obtained for each oligonucleotide of a given length (up to 14 nucleotides) but different nucleotide composition (Pomerantz et al. 1993). Any nucleotide substitution will result in either a peak shift owing to the mass difference between the cleavage fragments or, if the mutation changes the targeted base, a cleavage product containing a different number of bases. DNA fragments >40 to 50 nucleotides in length are not accurately detected in this system. Therefore, sequences resulting in large fragments after base-specific cleavage, such as those containing large numbers of tandem repeats, may be refractory to analysis with this method.

Initial screening is performed by comparing the cleavage product masses of the wild-type allele to those of test samples. Differences corresponding to base changes will be observed. Accurate mass determination of each of these small fragments is possible, allowing unambiguous assignment of base composition for each oligonucleotide fragment. To detect mutations when both wild-type and mutated fragments are coincident with the masses of other oligonucleotides, quantitation of the number of molecules at that peak must be used. To differentiate between fragments of identical mass but different sequence, PSD is used as the resultant spectrum is based on the sequence of the oligonucleotide. This information allows deduction of the nature of the mutation and, after specific cleavage at different bases and integration of the data, the position of the mutation.

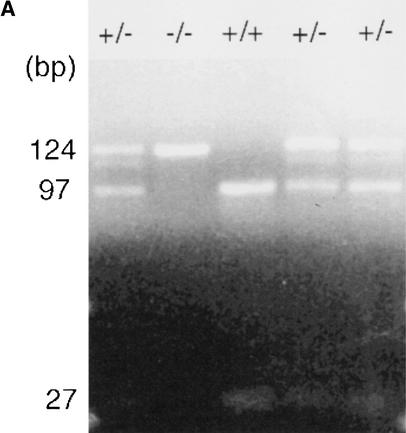

Although a number of methods are available to effect base specific nucleotide cleavage (Maxam and Gilbert 1977; Ambrose and Pless 1987), we have used uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG) to cleave the DNA at uracil residues. Uracil is incorporated into the sequence by replacement of dTTP with dUTP in the PCR (Warner and Duncan 1978; Kwok and Higuchi 1989). The utility of this method is shown by the detection of a sequence polymorphism in the IL-12p40 gene 3′ untranslated region (UTR; Huang et al. 2000). This sequence change results in a TaqI restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) and therefore can be followed by enzymatic digestion of PCR products. A PCR assay was designed to incorporate the mutated region, and the product was then subjected to treatment with UNG. The products were purified and then analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. The sequence of the PCR primers and product, along with the mutation, are shown in Figure 1. The C-to-T change results in a TaqI RFLP, which is seen in the homozygote and heterozygote states in Figure 2. The mass spectra generated by MALDI-TOF are also shown in Figure 2. The expected and observed masses of the cleavage products from both alleles are given in Table 1. The position of the mutation and identity of the changed base can be deduced from this data.

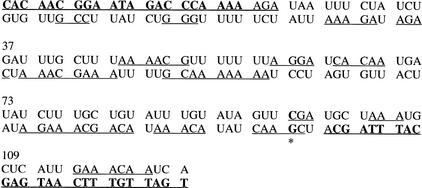

Figure 1.

Sequence of IL12p40 3′ untranslated region (UTR) polymerase chain reaction product used in this experiment. Primers are shown in bold. Expected cleavage products >2 bp are underlined. The polymorphism at position 97 is indicated by an asterisk. The polymorphism is a C-to-T change that results in a change of the cleavage products at that position from CGA to AGA in the forward strand and CAAGC to CAA in the reverse strand. The presence of C at position 97 results in a TaqI site, and this allele is called “+”; the other allele is “−”.

Figure 2.

(A) TaqI restriction digest of IL12 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products from +/− individuals (lanes 1,4,5) a +/+ individual (lane 3) and a −/− individual (lane 2). The 124-bp fragment is cleaved by TaqI (when possible) to produce 97- and 27-bp fragments. (B) Linear matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) spectra of cleavage products. (Left) Spectra showing a mass range of 1000 to 3500; (right) same spectra, but in detail, showing the mass range from 1000 to 1700. Spectra ia and ib are from a −/− individual, spectra ii a and iib are from a +/+ individual, and spectra iiia and iiib are from a +/− individual. Observed masses are indicated above peaks. Arrows indicate the peaks that change between the two alleles.

Table 1.

Products from cleavage of IL 12 polymerase chain reaction product with uracil-N-glycosylase.

| Expected fragmentsa | Expected mass (da) | Allele in which fragment is seen | Observed mass (Da) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | +/− | −/− | |||

| GCC | 1005.6 | +/− | 1007.38 | 1004.93 | 1006.13 |

| CAA | 1013.6 | − | N/O | 1012.41 | 1014.22 |

| CGA | 1029.6 | + | 1028.69 | 1028.57 | N/O |

| AAA | 1037.6 | +/− | 1035.85 | 1036.69 | 1037.89 |

| AGA | 1053.6 | − | N/O | 1053.69 | 1055.88 |

| GGG | 1085.6 | +/− | 1085.97 | 1084.61 | 1088.01 |

| AGAC | 1342.8 | +/− | 1343.55 | 1340.09 | 1343.63 |

| AGGA | 1382.8 | +/− | 1379.17 | 1382.13 | 1383.46 |

| CACAA | 1616.0 | +/− | 1615.27 | 1615.74 | 1617.10 |

| CAAGC | 1632.0 | + | 1629.59 | 1632.72 | N/O |

| AAACA | 1640.0 | +/− | 1636.75 | 1639.14 | 1640.87 |

| AAAGA | 1680.0 | +/− | 1679.71 | 1678.97 | 1680.74 |

| AAAACG | 1969.2 | +/− | 1965.75 | 1969.36 | 1971.46 |

| GAAACAA | 2282.4 | +/− | 2284.10 | 2285.29 | 2282.65 |

| AAACGAAA | 2595.6 | +/− | 2591.63 | 2594.18 | 2597.34 |

| GCAAAAAAA | 2908.8 | +/− | 2906.31 | 2912.22 | 2908.53 |

| AGAAACGACA | 3214.0 | +/− | 3210.34 | 3211.75 | 3216.05 |

Fragments >2 bp, excluding primer fragments. N/O = not observed.

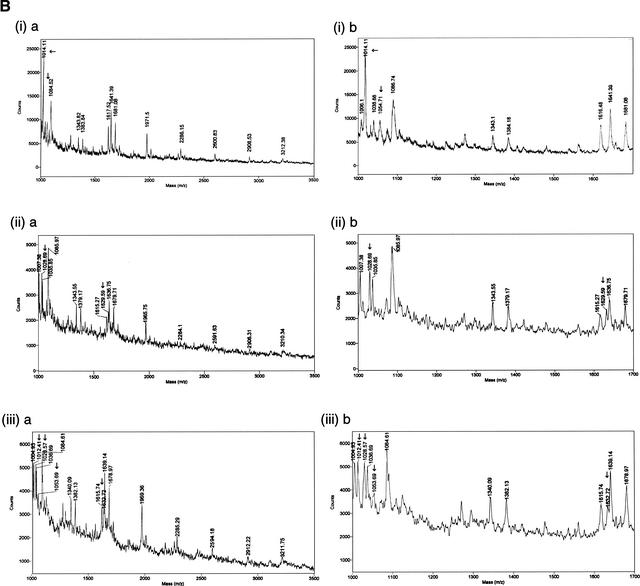

To decrease the complexity of the spectra produced by the cleavage of double-stranded PCR products, a protocol for cleavage of only one strand was also devised. Magnetic streptavidin beads were used to bind PCR products containing a biotin moiety attached 5′ to the forward strand. The PCR product spans a known single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), and the predicted molecular weight of the digest fragment containing the SNP can be seen in Table 2. Incubation with NaOH results in the elution and removal of the unbiotinylated reverse strand. The bound forward strand of the PCR product can then be digested using UNG. Spectra showing both forms of the polymorphism can be seen in Figure 3. The removal of the reverse strand to produce a single-stranded PCR product reduces the number of potential fragments generated by UNG digestion that complicate spectra and analysis. A second pair of reactions with biotin incorporated into the reverse strand will then allow analysis of that strand to produce the complementary spectra (data not shown). This will add to the sensitivity of this technique.

Table 2.

Forward strand polymerase chain reaction product digest

| Strain | Predicted (Da) | Observed (Da) |

|---|---|---|

| SJL | 3560.42 | 3559.84 |

| C57B1/6 | 3576.42 | 3578.05 |

Figure 3.

Partial spectra of uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG) digest of the forward strand of polymerase chain reaction product amplified using mouse genomic DNA from strains SJL (top) and C57BL/6 (bottom) showing digest fragment spanning single nucleotide polymorphism site with an ∼16 Da difference in fragment size owing to the difference in molecular weight between the bases “A” 313.21 Da and “G” 329.21 Da.

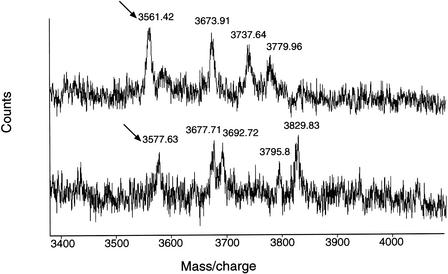

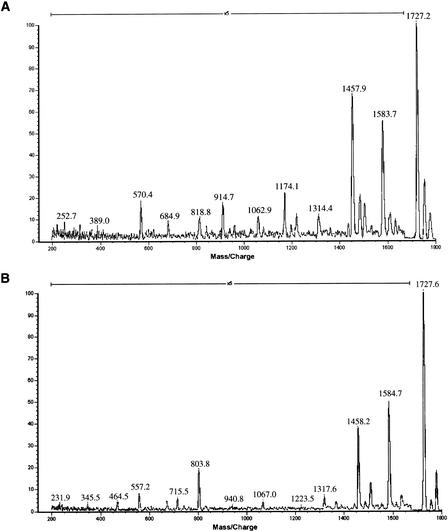

The utility of MALDI-TOF analysis coupled with PSD is shown in Figure 4, in which the mass spectra of two oligonucleotides of identical nucleotide composition (and therefore identical MALDI-TOF profile) are presented. The resulting PSD spectra are quite distinguishable and are based on the characteristic fragmentation of each of the oligonucleotides. As the sequence determination of small oligonucleotides is feasible using molecular dissociation methods (Nordhoff et al. 1996), the extrapolation of this mutation detection protocol into an accurate resequencing protocol seems possible.

Figure 4.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) postsource decay (PSD) mass spectrum of oligonucleotides of identical nucleotide composition. Spectrum A is of a 6-mer of sequence CATCCT; spectrum B, a 6-mer of sequence CACCTT. Both have parent ion mass of 1727.2 Da. Observed masses are shown above the peaks. Fragments of PSD are shown at an intensity magnification of five.

The level of specificity possible using this technique and the rapid sample analysis time lend this technique to the mass screening of individuals for sequence changes. In combination with MS-based sequencing, it is likely that this technique could be used to resequence kilobase lengths of DNA. Before this happens, sample purification needs to be refined and automated, and the fragmentation patterns of short oligonucleotides need to be better understood.

METHODS

Genomic DNA from human volunteers of each possible genotype of the IL-12p40 3′-UTR polymorphism (i.e., +/+, +/−, and −/−, in which + is the presence of the Taq restriction site) were isolated using standard methods. PCRs were performed in 20 μL reactions in 192-well plates in a Corbett thermocycler with the following reaction mixture: 50 mM KCl; 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3); 2.5 mM MgCl2; 0.15 mM dATP, dCTP, and dGTP (Promega); 5 mM dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim GmBH); 0.5 U AmpliTaq Gold (Perkin Elmer); and 0.4 μM primers (Bresatec; sequence shown in Fig. 1). After an initial 15-min incubation at 95°C, the reactions were cycled for 15 sec at 95°C, for 35 sec at 58°C, and for 35 sec at 72°C for 40 cycles. Seven reactions were pooled for the homozygotes; nine reactions, for the heterozygote. One unit of AmpErase UNG (Perkin Elmer) was added to each pool, and the reaction was incubated for 1 h at 50°C, followed by 30 min at 105°C. The extent of completion of the cleavage reaction was monitored by the absence of the full-length band on an agarose gel. The cleavage products were purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromography on a 100 × 2.1-mm-internal-diameter C8 aquapore RP300 column (Applied Biosystems). The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min, and absorbance was monitored at 254 nm. The sample was loaded onto the column, washed with 0.1 M triethylammoniumacetate (TEAA), and eluted using 0.1 M TEAA/60% acetonitrile. The fraction with absorbance at 254 nm was collected and evaporated to dryness using a Savant Speedivac. The residue was resuspended in 100 μL distilled deionized water, evaporated to dryness, and then resuspended in 1 μL water; 0.5 μL of this was mixed with 0.5 μL 3-hydroxypicolinic acid (saturated solution in 50% acetonitrile) and 0.5 μL NH4+ ion-exchange beads (BioRad, 50W-X4; mesh size, 100 to 200 μm) on the MALDI-TOF sample slide. A Voyager BioSpectrometry workstation equipped with delayed extraction ionization from PerSeptive Biosystems was used to characterize the reaction products. One hundred twenty-eight laser pulses at power 1800 (arbitrary value) were averaged. Samples were calibrated externally using oligonucleotides of known molecular weight.

Genotypes were confirmed by showing the presence or absence of the TaqI restriction site by digesting PCR products with TaqI restriction enzyme (GIBCO BRL) and analyzing the products by agarose electrophoresis. DNA bands were stained with ethidium bromide.

To reduce the number of fragments generated by UNG digestion of double-stranded (DS) PCR products, Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads were used to remove the reverse strand. Two hundred–bp PCR products were amplified using genomic mouse DNA from two strains, SJL and C57BL/6, with the PCR product spanning a SNP located on chromosome 9, which is “A” in SJL and “G” in C57BL/6.

One hundred microliters of PCRs were performed in 96-well plates using a M.J. Research PTC 200 thermal cycler with the reaction mixture of 50 mM KCl; 20 mM Tris; 2.5 mM MgCl2; 0.15 mM dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dUTP (Pharmacia); and 1.0 U Taq polymerase (Perkin Elmer) plus 5 μM of biotinylated forward primer (biotin 5′-GCACCATCAGAGCTGTCAAACCCAT-3′) and 5 μM of reverse primer (5′-AGTATCCACCCCCAGAGCTTGTTAA-3′; Sigma). After an initial incubation for 2 min at 94°C, the reactions were cycled for 20 sec at 94°C, for 30 sec at 60°C, and for 1.30 min at 72°C for 30 cycles; 10 × 100 μL PCRs for each strain were pooled, and ethanol precipitated. The PCR products were further purified using QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen), as instructed, to remove excess biotinylated primers.

The PCR products were resuspended in 1 mL bead binding buffer (1 M NaCl, 5 mM Tris, and 0.5 mM EDTA; Sigma) and coupled to 20 μL of streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (Scipac 10 mg/mL) for 1 h at room temperature. The beads were washed with 0.2 M NaOH (Sigma) for 5 min to remove the unbound reverse strand, followed by repeated washing (×5) with water and resuspension in 100 μL of UNG buffer (MBI). The beads with the remaining bound forward strand were digested using 5 U UNG overnight at 37°C.

After digestion, 5 μL of NH4OH (Aldrich) was added, and the sample was heated for 5 min at 95°C to induce strand fragmentation. The sample beads were precipitated using a magnet (Dynal), and the supernatant was collected in a new tube. The beads were washed once with 50 μL of water and pooled with the digest supernatant. The digest mix was dried down in a rotary evaporator (Christ α RCV) to remove excess water and NH4OH. The dried sample was suspended in ∼10 μL of water and further purified using an A.B. Nucleic Acid Purification kit for Sequazyme™ (courtesy of Applied Biosystems).

The sample was dried down to 1 μL and then mixed with 1 μL of MALDI-TOF matrix 2,4,6-trihydroxyacetophenone monohydrate (THAP) 10 mg/mL dissolved in 50% acetonitrile in water; 1 μL of sample plus matrix was spotted on a sample plate and analyzed using a Perseptive Biosystems Voyager-DE Pro MALDI-TOF MS. Spectra were obtained in linear mode using negative ions with delayed extraction of 650 ns, with up to 256 averaged 377-nm laser pulses. Samples were calibrated externally using oligonucleotides of known molecular weight.

PSD spectra were obtained using a Kratos Kompact MALDI4 TOF MS equipped with a 377-nm laser and a curved field reflector in positive ion mode. Matrix and sample preparation were as outlined above. After obtaining a mass spectrum in linear mode, PSD fragmentation was performed by setting an ion gate width of ∼100 Da around the ion of interest (m/z 1727.2) in reflectron mode. Two hundred profiles were acquired at a rate of five laser shots per profile. Spectra were calibrated externally using a 1 pmole/μL solution of human angiotensin I (m/z 1297.5) and a matrix-derived ion (m/z 173.2) with the ion gate switched off.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of the Wellcome Trust (SF), Bruce Kemp, Ken Mitchelhill, Grant Morahan, Dexing Huang, Sue Forrest, Eric Reynolds, and Vikki Marshall.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL foote@wehi.edu.au; FAX +613 9347-0852.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.157802. Article published online before print in August 2002.

REFERENCES

- Ambrose BJ, Pless RC. DNA sequencing: Chemical methods. Methods Enzymol. 1987;52:522–538. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J, Liu YH, Lubman DM, Siemieniak D. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry of restriction enzyme-digested plasmid DNA using an active Nafion substrate. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1994;8:687–691. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1290080904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton RG, Rodrigues NR, Campbell RD. Reactivity of cytosine and thymine in single-base-pair mismatches with hydroxylamine and osmium tetroxide and its application to the study of mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:4397–4401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori M, Shibata A, Yoshioka K, Sakaki Y. Orphan peak analysis: A novel method for detection of point mutations using an automated fluorescence DNA sequencer. Genomics. 1993;15:415–417. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Cancilla MR, Morahan G. Complete primary structure, chromosomal localization, and definition of polymorphisms of the gene encoding the human interleukin-12 p40 subunit. Genes Immun. 2000;1:515–520. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok S, Higuchi R. Avoiding false positives with PCR. Nature. 1989;339:237–238. doi: 10.1038/339237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman LS, Silverstein K, Grinfeld E. Searching for gene defects by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1986;1:285–297. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1986.051.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YH, Bai J, Zhu Y, Liang X, Siemieniak D, Venta PJ, Lubman DM. Rapid screening of genetic polymorphisms using buccal cell DNA with detection by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1995;9:735–743. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1290090905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxam AM, Gilbert W. A new method for sequencing DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1977;74:560–564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordhoff E, Kirpekar F, Roepstorff P. Mass spectrometry of nucleic acids. Mass Spectrom Rev. 1996;15:67–138. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2787(1996)15:2<67::AID-MAS1>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orita M, Iwahana H, Kanazawa H, Hayashi K, Sekiya T. Detection of polymorphisms of human DNA by gel electrophoresis as single-strand conformation polymorphisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86:2766–2770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz S, Kowalak J, McCloskey J. Determination of oligonucleotide composition from mass spectrometrically measured molecular weight. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1993;4:204–209. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(93)85082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner HR, Duncan BK. In vivo synthesis and properties of uracil-containing DNA. Nature. 1978;272:32–34. doi: 10.1038/272032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber JL. Human DNA polymorphisms and methods of analysis. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1990;1:166–171. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(90)90026-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]