Abstract

The freshwater pufferfish Tetraodon nigroviridis (TNI) has become highly attractive as a compact reference vertebrate genome for gene finding and validation. We have mapped genes, which are more or less evenly spaced on the human chromosomes 9 and X, on Tetraodon chromosomes using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), to establish syntenic relationships between Tetraodon and other key vertebrate genomes. PufferFISH revealed that the human X is an orthologous mosaic of three Tetraodon chromosomes. More than 350 million years ago, an ancestral vertebrate autosome shared orthologous Xp and Xq genes with Tetraodon chromosomes 1 and 7. The shuffled order of Xp and Xq orthologs on their syntenic Tetraodon chromosomes can be explained by the prevalence of evolutionary inversions. The Tetraodon 2 orthologous genes are clustered in human Xp11 and represent a recent addition to the eutherian X sex chromosome. The human chromosome 9 and the avian Z sex chromosome show a much lower degree of synteny conservation in the pufferfish than the human X chromosome. We propose that a special selection process during vertebrate evolution has shaped a highly conserved array(s) of X-linked genes long before the X was used as a mammalian sex chromosome and many X chromosomal genes were recruited for reproduction and/or the development of cognitive abilities.

[Sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in GenBank and assigned the following accession no: AJ308098.]

The highly compact genomes of the Japanese pufferfish, Fugu rubripes (400 Mb), and the freshwater pufferfish, Tetraodon nigroviridis (380 Mb), are particularly useful for large-scale comparative sequencing to characterize all human genes and to interpret the complex architecture of the human and other vertebrate genomes (Roest Crollius et al. 2000a; Venkatesh et al. 2000). In comparison with Fugu, the small and hardy Tetraodon has the added advantage that it can be maintained easily in the laboratory. However, as neither Fugu nor Tetraodon can be manipulated or bred in captivity, genetic analyses are not possible in these important animal models. Comparative sequencing approaches have shown that gene structure and short-range gene order (within megabase domains) are largely conserved between pufferfish and humans (Miles et al. 1998; Brunner et al. 1999), but the construction of chromosome homology maps has been difficult. A solution to this problem comes from fluorescence in situ hybridization of BACs containing the pufferfish orthologs of known human genes to Tetraodon chromosomes. In this study, we have established the syntenic relationships of human chromosome 9, which represents an ancestral mammalian autosome (Chowdhary et al. 1998), and of the human X chromosome with the pufferfish genome.

The X adopted its function as a sex chromosome ∼240–320 million years ago after divergence of mammals and birds (Lahn and Page 1999). Conservation of the mammalian X in its entirety is thought to be a consequence of X inactivation to ensure dosage compensation for most X-linked genes between males and females (Ohno 1967; Lyon 1972). Only a few genes have been translocated between the X and autosomes during eutherian evolution. For example, CLCN4 maps very close to the pseudoautosomal region of the X in humans and the wild Mediterranean mouse, but to chromosome 7 in the laboratory mouse (Rugarli et al. 1995). Pseudoautosomal genes have active partners on the Y and, therefore, are exempt from Ohno's law. It is plausible that CNCL4, and other genes, which at first glance appear to contravene Ohno's law, was originally pseudoautosomal in an eutherian ancestor and a translocation onto an autosome has occurred in the laboratory mouse (Marshall Graves 1996). Such X to autosome rearrangements are very rare in eutherian mammals, but gene order on the X has been rearranged extensively in many species (Iannuzzi et al. 2000; Kuroiwa et al. 2001).

In contrast, human chromosome 9 segments have been translocated onto nonhomologous chromosomes in a variety of species following the divergence of a common mammalian ancestor, for example, human 9 genes are distributed on four different mouse chromosomes (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Homology). Many genes from human 9pter-q31 have orthologs on the chicken Z sex chromosomes, indicating the common ancestry of human 9 and chicken Z (Nanda et al. 1999, 2000; Schmid et al. 2000), which diverged ∼350 million years ago (Kumar and Hedges 1998). Like the mammalian X, the entire Z appears to be conserved as a single syntenic block in birds (Shetty et al. 1999; Schmid et al. 2000). However, replication of the two Z chromosomes in male birds is not asynchronous (Schmid et al. 1989), and it is not clear whether the majority of Z-linked genes are subject to dosage compensation (Kuroda et al. 2001; McQueen et al. 2001).

In contrast to mammals and birds, the pufferfish, like most fish, does not possess heteromorphic sex chromosomes (Grützner et al. 1999), and the genetic mechanism(s) of sex determination is still unclear. It is known, however, that environmental and endocrine factors can strongly influence sex differentiation in fish (Baroiller et al. 1999). Because teleost fish diverged >400 million years ago (Kumar and Hedges 1998), they serve as a useful outgroup to test whether conservation of the mammalian X and avian Z is due to an intrinsic chromosomal property or their sex chromosomal status.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To date, a random Tetraodon DNA sample of 800 Mb (equivalent to approximately two genomes) has been sequenced (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/tetraodon). The pufferfish genome has a highly compact architecture and there is much more pufferfish than zebrafish sequence available for ortholog searches. These are important advantages of comparative mapping of teleost and tetrapod genes, which can help to infer the ancestral state of mammalian chromosomes. Using Exofish (Roest Crollius et al. 2000a), we identified 40 Tetraodon BACs that share orthologous gene sequences with human chromosomes 9 and X (Table 1). No Tetraodon orthologs of the pseudoautosomal region Xp22.3 could be identified. The pseudoautosomal genes were added independently to the sex chromosomes of eutherian mammals and then became subject to progressive degradation (addition-attrition hypothesis) (Marshall Graves 1995; Lahn and Page 1999). To identify segments of conserved chromosomal synteny, Tetraodon BACs orthologous to chromosome segments of the human 9 and X were hybridized in situ to Tetraodon metaphase spreads. All BACs produced discrete hybridization signals on a single Tetraodon chromosome pair, allowing unequivocal chromosomal mapping.

Table 1.

List of Clones Containing Tetraodon Orthologs of Human Genes

| Gene | Human chromosome | Tetraodon chromosome | TNI BAC end sequence EMBL accession no. | Clone name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| band | Mb distance | ||||

| AK3 | 9p24 | n.a.* | 1 | AL352756 | C0AB028O11 |

| GLDC | 9p24 | 3.3 | 9 | AL340373 | C0AA037I03 |

| TYRP1 | 9p23 | 9.3 | 11 | AL339713 | C0AB047I11 |

| DMRT1 | 9p23 | 14.5 | 8 | AL329663 | C0AA052C14 |

| CNTFR | 9p21 | 33.5 | 8 | AL333197 | C0AA051P16 |

| ANXA1 | 9q21 | 65 | 10 | AL317970 | C0AA051J11 |

| GCNT1 | 9q21 | 68 | 8 | AL329563 | C0AA039H15 |

| HNRPK | 9q21 | 76.2 | 12 | AL349127 | C0AA017N19 |

| HSD17B3 | 9q22 | 87.9 | 7 | AL321714 | C0AB002N22 |

| TMOD | 9q22.3 | 89.2 | 13 | AL337508 | C0AB012I03 |

| EPB72 | 9q33 | 115 | 14 | AL350810 | C0AB008H21 |

| PTGS1 | 9q33 | 116.5 | 8 | AL351240 | C0AA007A13 |

| PBX3 | 9q33 | 120 | 15 | AL340899 | C0AA030I07 |

| AK1 | 9q34 | 121.6 | 16 | AL341655 | C0AA050J03 |

| ENG | 9q34 | 121.6 | 17 | AL346287 | C0AA043F14 |

| ASS | 9q34 | 124.8 | 10 | AL344332 | C0AB011P19 |

| ABL1 | 9q34 | 124 | 10 | AL350025 | C0AA031E21 |

| ISPK1 | Xp22 | n.a. | 1 | AL321584 | C0AA033J23 |

| PIGA | Xp22 | 13.0 | 1 | AL306766 | C0AB026J12 |

| PHKA2 | Xp22 | 17.5 | 7 | AL336707 | C0AA025A16 |

| PDHA1 | Xp22.1 | 17.9 | 7 | AL342845 | C0AB001P05 |

| SMS | Xp22.1 | 19.6 | 7 | AL351833 | C0AB025D12 |

| SAT | Xp22.1 | 21.3 | 7 | AL338831 | C0AA019A15 |

| POLA | Xp22.3 | 21.8 | 6 | AL333304 | C0AA017E04 |

| OTC | Xp11.4 | 34.5 | 2 | AL339149 | C0AA010L18 |

| EXLM1 | Xp11 | n.a. | 2 | AL344211 | C0AB046K20 |

| MAOB | Xp11.3 | 40.2 | 2 | AL305902 | C0AB020J13 |

| PCTK1 | Xp11 | 44.5 | 7 | AL325789 | C0AA046M22 |

| P2RY4 | Xq13 | 64.6 | 1 | AL318925 | C0AA020M21 |

| K1F4A | Xq13 | 64.7 | 7 | AL306871 | C0AB032I13 |

| HOPA | Xq13 | 65.6 | 1 | AL334883 | C0AB014D21 |

| GJB1 | Xq13 | 65.7 | 1 | n.a. | C0AA019L09 |

| TAF2A | Xq13.1 | 65.9 | 7 | AL340618 | C0AA022A22 |

| PGK 1 | Xq21.1 | 72.2 | 7 | AL330772 | C0AA032P18 |

| LOC170240 | Xq22 | 97.5 | 1 | AL334745 | C0TB001K13 |

| BTK** | Xq22 | 96.5 | 1 | AJ308098 | ICRFp551C0473Q6 |

| GK | Xq22 | 96.9 | 2 | AL311483 | C0AB006D09 |

| MID2 | Xq22 | 103.4 | 1 | AL323465 | C0AB023P08 |

| UBE2A | Xq24 | 113.2 | 1 | AL344408 | C0AA048M20 |

| GRIA3 | Xq25 | 119 | 7 | AL347790 | C0AA015K14 |

| IDS | Xq28 | 145 | 1 | n.a. | C0AA040L12 |

Not available

cDNA clone

History of the Mammalian X Chromosome

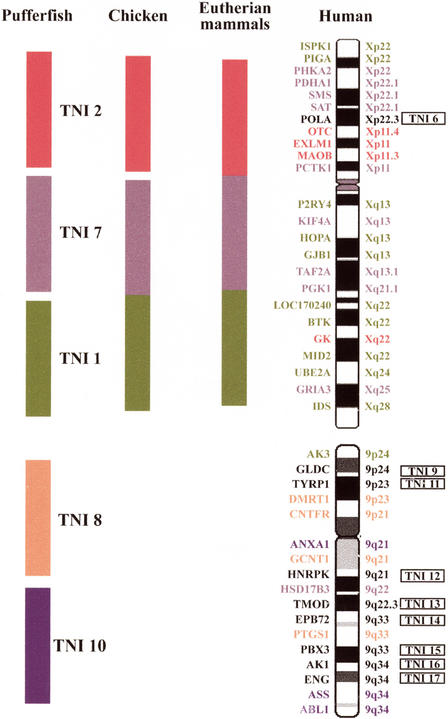

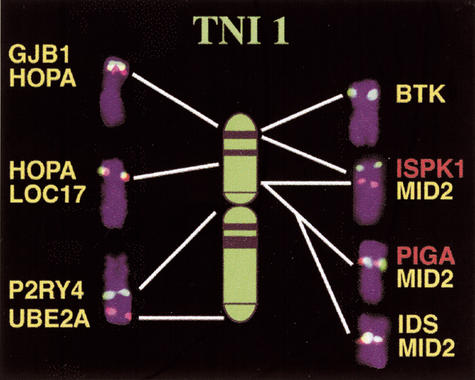

In this study, 10 X chromosomal genes were found to have orthologs on TNI 1, 4 on TNI 2 and 9 on TNI 7 (Fig. 1). Only 1 of 24 tested X orthologs, POLA, did not map to these 3 syntenic blocks. Hybridization of a TNI 1-specific microdissection DNA library revealed that TNI 1 corresponds to two smaller metacentric Fugu chromosomes. This explains the higher chromosome number (2n = 44) in Fugu, compared with Tetraodon (2n = 42) (data not shown). However, this split of TNI 1 does not affect the conservation of human X synteny. As 9 of 10 X orthologous genes on TNI 1 map to the short arm and the pericentromeric region (Fig. 2), we conclude that only these parts share homology with the human X. UBE2A was moved to the distal long arm of TNI 1 after the fusion of two ancestral pufferfish chromosomes (Grützner et al. 1999). This hypothesis is consistent with evidence that all TNI 1 orthologs tested map to the same small metacentric Fugu chromosome (data not shown). By comparing the relative position of orthologous genes on TNI 1 and human X (Fig. 2), it is evident that although large blocks of chromosomal synteny are conserved between pufferfish and humans, the gene order within the conserved blocks has changed. This indicates that intrachromosomal rearrangements occur much more frequently than interchromosomal rearrangements. This is also the case in the zebrafish (Barbazuk et al. 2000; Postlethwait et al. 2000; Woods et al. 2000) and chicken genomes (Burt et al. 1999; Schmid et al. 2000).

Figure 1.

Syntenic relationships of human chromosomes X and 9 with the Tetraodon genome and an evolutionary model for the mammalian X. The top shows the common phylogenetic origin of pufferfish chromosomes TNI 1, TNI 2, and TNI 7 and the human X. At left, the three Tetraodon blocks of conserved synteny are depicted as green (TNI 1), red (TNI 2), and purple (TNI 7) bars. At right is shown the mosaic synteny of human X and the chromosomal localizations of the comparatively mapped genes. The gene order is based on genomic sequence data (http://www.genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway December 2001). The POLA gene, indicated in black, maps to a different Tetraodon chromosome (TNI 6) and, thus, does not belong to the delineated synteny groups. The two central schematic drawings represent hypothetical ancestral X chromosomes. Because human X orthologous genes from TNI 1 and TNI 7 are linked in chicken, we conclude that an ancestral X autosome contained these two sets of Xp and Xq genes even before the avian-mammalian split. Because the human X orthologs belonging to the TNI 2 block are autosomal in marsupials and monotremes, they represent a recent addition to the eutherian sex chromosomes. For simplicity, the three X syntenic Tetraodon chromosomes are depicted as blocks on the hypothetical X ancestors. However, this does not reflect the real gene order, which may differ significantly from both the order in the three Tetraodon chromosomes and in the human X. At bottom is shown a much lower degree of synteny conservation for human chromosome 9 in the pufferfish than for the X. Comparative mapping of human 9 orthologous genes reveals two syntenic blocks on TNI 8 (orange) and TNI 10 (blue). One gene each reside on TNI 1 (green) and TNI 7 (purple), respectively. The genes indicated in black all map to different TNI chromosomes.

Figure 2.

Localization of human Xp (indicated by red gene symbols) and Xq (green) orthologous genes on a TNI 1 ideogram. TNI 1 chromosomes with representative FISH signals of 10 genes were cut out from different metaphases.

Comparative gene mapping data in different vertebrate species suggest that a sequence of fusion events has occurred (Fig. 1). Two X orthologous genes from TNI 1, BTK and UBE2A, and two X orthologous genes from TNI 7, PHKA2 and PGK1, are syntenic on chicken chromosome 4 (Schmid et al. 2000). PGK1 has also been mapped on the marsupial X (Watson et al. 1990). Therefore, we conclude that the chromosomal ancestors of TNI 1 and TNI 7 were fused before the avian-mammalian split. This ancestral vertebrate XA, which evolved as an autosome >350 million years ago, already contained most genes (79% of the tested orthologs) from the present-day mammalian X, including many genes from the human X short arm. One X ortholog from TNI 7, PDHA1, is autosomal in marsupials (Fitzgerald et al. 1993). The most likely explanation for this is that the TNI 1 and TNI 7 syntenic groups fused to form the chromosome represented by the marsupial X and small segments of the ancestral XA were translocated to a marsupial autosome(s), whereas most of the chromosome formed the X. It is plausible that genes that are syntenic in pufferfish and humans (PDHA1 belongs to a group of 9 X orthologs on TNI 7) were linked in the last common ancestor of teleosts and tetrapods. In contrast, the autosomal localization of OTC and MAOB in monotremes and marsupials (Spencer et al. 1991) indicates that the TNI 2 block was added to the mammalian X after divergence of the eutherian, metatherian, and prototherian lineages ∼170 million years ago. Consistent with this model and with one notable exception (GK was inverted onto the long arm), all TNI 2 orthologs map close to the putative fusion point in human Xp11 of the mammalian X-autosomal rearrangement (Wilcox et al. 1996). In addition, OTC maps to chicken chromosome 1 (Schmid et al. 2000) and is not syntenic with the chicken orthologs of TNI 1 and TNI 7 genes.

Comparative gene mapping in marsupials and monotremes (Watson et al. 1990; Spencer et al. 1991; Wilcox et al. 1996) has suggested that the human X long arm corresponds to the ancestral mammalian X, whereas most of the short arm was added in the eutherian lineage. In the pufferfish, many human Xp and Xq genes are syntenic on TNI 1 and TNI 7. In addition, zebrafish linkage groups (LGs) 9 and 23 are also endowed with both human Xp (CXORF5 and ASMTL in LG 9; EBP in LG 23) and Xq orthologs (API5L1 in LG9; L1CAM, IDH3G, and SSR4 in LG 23). One possible interpretation of these findings is that most of the human X short arm was part of the ancestral XA and does not represent a recent addition to the eutherian X. However, due to the lack of mapping data in species that are intermediate between fish and mammals, we cannot rule out that genes located on the short arm were separated from those on the long arm in mammalian ancestors during evolution.

In comparison with the pufferfish, the conservation of X chromosomal synteny appears to be relatively low in zebrafish (at least in current zebrafish maps). The human X chromosome genes are distributed on eight zebrafish LGs, each containing several orthologs and an additional three LGs with at least one X gene (Barbazuk et al. 2000; Postlethwait et al. 2000; Woods et al. 2000). However, because there is little overlap between the gene sets that have been analyzed in zebrafish and pufferfish, it is not possible to establish syntenic relationships between these two teleost models. In addition, the prevalence of duplicated chromosome segments in the zebrafish genome may confuse the results of zebrafish–human synteny mapping.

Disruption of Human Chromosome 9 Synteny

Comparative mapping of 17 human chromosome 9 orthologous BACs showed a considerably lower degree of conserved chromosomal synteny in pufferfish, compared with human X genes (Fig. 1). Four human 9 orthologous genes, including the evolutionarily conserved sex-determining gene DMRT1 (Nanda et al. 1999; Raymond et al. 1999), are syntenic on TNI 8. Three other human 9 orthologs are linked on TNI 10. Numerous cohybridization experiments revealed that the remaining 10 (59%) human 9 genes tested are all distributed on different Tetraodon chromosomes. For example, AK3 (from human 9p24) and HSD17B3 (9q22) were colocalized with X orthologous BACs on TNI 1 and TNI 7, respectively. In the course of this study, we have identified marker clones for 17 of the 21 Tetraodon chromosomes (Table 1), which serve as in situ hybridization probes for anchoring linkage groups and sequenced contigs in the pufferfish map.

Because the zebrafish LG 5 contains 18 putative huan 9 orthologs including DMRT1 (Barbazuk et al. 2000; Postlethwait et al. 2000; Woods et al. 2000), it has been speculated that a common ancestor of human 9 and chicken Z may have already existed before the split of zebrafish and tetrapods, possibly functioning as a cryptic sex chromosome. Although our in situ hybridization results suggest disruption of human 9 and zebrafish LG 5 orthologous blocks in the pufferfish (i.e., ANXA1 and ASS from LG 5 are syntenic on TNI 10, whereas DMRT1 is on TNI 8), this does not exclude the possibility that DMRT1 plays a crucial role in sex determination in fish. In addition, zebrafish LGs 21 and 25 show synteny of 6 and 15 human 9 orthologs, respectively.

Evolutionary Implications

The observed disruption of human chromosome 9 and chicken Z synteny in pufferfish suggests that, despite an excess of evolutionary inversions, interchromosomal changes must also have occurred in the teleost lineage. The extraordinary conservation of X synteny could be due to intrinsic chromosomal properties that confer selective pressure on large parts or the entire X to conserve its synteny. One such factor may be the enrichment for genes with a similar functional spectrum and/or expression pattern. The human X is known to contain an (approximately fourfold) excess of genes that are associated with general cognitive abilities (Marshall Graves and Delbridge 2001; Zechner et al. 2001). Many of these genes are expressed in both brain and testis and seem to be related to reproduction (Saifi and Chandra 1999). In evolutionary terms, these genes are usually highly conserved and engaged in basic cellular mechanisms, such as mRNA stabilization, cytoskeleton organization, and signaling cascades (First International Workshop on Comparative Genome Organization 1996; Lahn and Page 1999). We propose that this highly conserved X-linked array(s) of functionally important genes was already selected before the mammalian sex chromosomes evolved. This implies that many of these conserved genes must have acquired new or additional (brain and testis) functions that exert the so-called large X chromosome effect on general intelligence (Zechner et al. 2001) and fertility (Wu and Davis 1993; Turelli and Orr 1995) in humans.

METHODS

Tetraodon Probes

The construction and sequencing of Tetraodon BAC libraries were described previously (Roest Crollius et al. 2000b). The selection of BAC clones for in situ hybridization followed a forward-reverse similarity search strategy on the basis of end sequences. This ensured that the Tetraodon BAC probes contained orthologs of the desired human genes within the limits of known sequences from the human and Tetraodon genomes. In the forward experiment, a database of 734 partial and complete protein sequences from genes of human chromosomes 9 (107 genes) and X (627 genes) was compiled by combining information from SWISSPROT (Bairoch and Apweiler 2000) and Refseq (Wheeler et al. 2002). The set of human proteins was compared by use of Exofish (Roest Crollius et al. 2000a) to 951,256 Tetraodon whole genome shotgun sequences, including 47,599 BAC and 903,657 plasmid end sequences. This dataset represents more than two equivalents of the Tetraodon genome in randomly distributed single reads, or ∼87% genome coverage. A total of 96 Tetraodon BAC end sequences were identified as matching one of the 734 human genes with Exofish criteria in addition to numerous additional plasmid end sequences. Each of the 96 human protein sequences was then aligned to the BAC and plasmid end sequences using the Smith-Waterman algorithm (Smith and Waterman 1981). Alignments were inspected manually to identify where the human protein sequence aligns best to a BAC end sequence as opposed to a plasmid end sequence. By use of these criteria, seven BAC end sequences were rejected for X chromosome genes. In the reverse experiment, each of the 89 remaining Tetraodon sequences was compared by use of the Smith-Waterman algorithm to the human International Protein Index (Apweiler et al. 2001) to verify that no other human protein sequence aligns better to the Tetraodon BAC end than the gene of interest from human chromosome 9 or X. Of 89 Tetraodon sequences, 40 found the original gene (17 on human 9 and 23 on X) in this reverse experiment. These 40 pairs of Tetraodon BAC ends and human genes were considered orthologs on the basis of a global screen between the available 24,147 entries in the human International Protein Index and ∼87% of the Tetraodon genome sequence.

Clone ICRFp551C0473Q6 was isolated by hybridization of a microdissected TNI 1 library to arrayed Tetraodon cDNA clones (RZPD library no. 551). Sequencing and sequence comparisons revealed that it is the Tetraodon ortholog of human BTK (GenBank accession no. AJ308098).

Chromosomal Mapping (PufferFISH)

Metaphase spreads were prepared from primary Tetraodon fibroblast cultures, as described elsewhere (Grützner et al. 1999). For FISH, the slides were treated with 100 μg/mL RNase A in 2× SSC (pH 7.0), at 37°C for 30 min and with 0.01% pepsin in 10 mM HCl at 37°C for 10 min. After refixing for 10 min in 1× PBS, 50 mM MgCl2, 1% formaldehyde, the preparations were dehydrated in an ethanol series. Slides were denatured for 1 min at 90°C in 70% formamide, 2× SSC (pH 7.0), and again dehydrated.

BAC DNAs and BTK cDNA were labeled with either biotin-16-dUTP or digoxigenin-11-dUTP by nick translation. For hybridization of one slide, 400 ng of biotinylated and/or digoxigenated probe DNA was coprecipitated with 50–100 μg sheared Tetraodon genomic DNA (as competitor), and 10–20 μg sheared human placental DNA (as carrier), and redissolved in 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 2× SSC. The hybridization mixture was denatured for 10 min at 80°C. Preannealing of repetitive DNA sequences was carried out for 30 min at 37°C. Next, the hybridization mixture was applied to each slide and sealed under a coverslip. The slides were hybridized for at least 3 d in a moist chamber at 37°C. The slides were then washed three times for 5 min in 50% formamide, 2× SSC at 42°C and once for 5 min in 0.1× SSC (pH 7.0), at 60°C and blocked with 4× SSC, 3% BSA, and 0.1% Tween 20 at 37°C for 30 min. Probes were detected with FITC-conjugated avidin and Cy3-conjugated anti-digoxin antibody. Chromosomes and cell nuclei were counterstained with 1 μg/mL DAPI in 2× SSC for 1 min and mounted in 90% glycerol, 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 2.3% DABCO.

Images were taken with a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope equipped with a thermoelectronically cooled CCD camera (Photometrics CH250), which was controlled by an Apple Macintosh computer. Vysis imaging software was used to capture gray scale images and to superimpose the source images into a color image.

WEB SITE REFERENCES

http://www.genome.ucsc.edu/Human Genome Browser Gateway. This site provides access to the sequence of the human genome. The December 2001 version of the human genome was used to determine the gene order on human chromosomes 9 and X.

http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/tetraodon; Tetraodon nigroviridis genomic resources. This site provides access to a variety of genomic resources, in particular to the whole shotgun sequence of Tetraodon nigroviridis.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Homology; human-mouse homology map. This site provides access to various comparative maps between human and mouse chromosomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Margaret Delbridge for critically reading the manuscript. This study was supported by research grant HA 1374/5–2 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL Haaf@humgen.klinik.uni-mainz.de; FAX 49-6131-175690.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.222402. Article published online before print in August 2002.

REFERENCES

- Apweiler R, Biswas M, Fleischmann W, Kanapin A, Karavidopoulou Y, Kersey P, Kriventseva EV, Mittard V, Mulder N, Phan I, et al. Proteome analysis database: Online application of InterPro and CluSTr for the functional classification of proteins in whole genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:44–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairoch A, Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:45–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbazuk WB, Korf I, Kadavi C, Heyen J, Tate S, Wun E, Bedell JA, McPherson JD, Johnson SL. Syntenic relationship of the zebrafish and human genomes. Genome Res. 2000;10:1351–1358. doi: 10.1101/gr.144700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroiller J-F, Guiguen Y, Fostier A. Endocrine and environmental aspects of sex chromosome differentiation in fish. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:910–931. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner B, Todt T, Lenzner S, Stout K, Schulz U, Ropers H-H, Kalscheuer V. Genomic structure and comparative analysis of nine Fugu genes: Conservation of synteny with human chromosome Xp22.2-p22.1. Genome Res. 1999;9:437–448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt DW, Bruley C, Dunn IC, Jones CT, Ramage A, Law AS, Morrice DR, Paton IR, Smith J, Windsor D, et al. The dynamics of chromosome evolution in birds and mammals. Nature. 1999;402:411–413. doi: 10.1038/46555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary BP, Raudsepp T, Frönicke L, Scherthan H. Emerging patterns of comparative genome organization in some mammalian species as revealed by Zoo-FISH. Genome Res. 1998;8:577–589. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.6.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First International Workshop on Comparative Genome Organization. Comparative genome organization of vertebrates. Mamm Genome. 1996;7:717–734. doi: 10.1007/s003359900222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J, Wilcox SA, Graves JA, Dahl HH. A eutherian X-linked gene, PDHA1, is autosomal in marsupials: A model for the evolution of a second testis-specific variant in eutherian mammals. Genomics. 1993;18:636–642. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grützner F, Lütjens G, Rovira C, Barnes DW, Ropers H-H, Haaf T. Classical and molecular cytogenetics of the pufferfish Tetraodon nigroviridis. Chrom Res. 1999;7:655–662. doi: 10.1023/a:1009292220760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannuzzi L, Di Meo GP, Perucatti A, Incarnato D, Schibler L, Cribiu EP. Comparative FISH mapping of bovid X chromosomes reveals homologies and divergences between the subfamilies bovinae and caprinae. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2000;89:171–176. doi: 10.1159/000015607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Hedges B. A molecular timescale for vertebrate evolution. Nature. 1998;392:917–920. doi: 10.1038/31927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda Y, Arai N, Arita M, Teranishi M, Hori T, Harata M, Mizuno S. Absence of Z-chromosome inactivation for five genes in male chicken. Chrom Res. 2001;9:457–468. doi: 10.1023/a:1011672227256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroiwa A, Tsuchiya K, Watanabe T, Hishigaki H, Takahashi E, Namikawa T, Matsuda Y. Conservation of the rat X chromosome gene order in rodent species. Chrom Res. 2001;9:61–67. doi: 10.1023/a:1026795717658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahn BT, Page DC. Four evolutionary strata on the human X chromosome. Science. 1999;286:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon MF. X-chromosome inactivation and developmental patterns in mammals. Biol Rev. 1972;47:1–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1972.tb00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall Graves JA. The origin and function of the mammalian Y chromosome and Y-borne genes: An evolving understanding. BioEssays. 1995;17:311–320. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall Graves JA. Breaking laws and obeying rules. Nat Genet. 1996;12:121. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-121a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall Graves JA, Delbridge ML. The X - a sexy chromosome. BioEssays. 2001;23:1091–1094. doi: 10.1002/bies.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen HA, McBride D, Miele G, Bird AP, Clinton M. Dosage compensation in birds. Curr Biol. 2001;11:253–257. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles C, Elgar G, Coles E, Kleinjan D-J, van Heyningen V. Complete sequencing of the Fugu WAGR region from the WT1 to PAX 6: Dramatic compaction and conservation of synteny with human chromosome 11p13. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:13068–13072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda I, Shan Z, Schartl M, Burt DW, Koehler M, Nothwang HG, Grützner F, Paton IR, Windsor D, Dunn I, et al. 300 million years of conserved synteny between chicken Z and human chromosome 9. Nat Genet. 1999;21:258–259. doi: 10.1038/6769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda I, Zend-Ajusch E, Shan Z, Grützner F, Schartl M, Burt DW, Koehler M, Fowler VM, Goodwin G, Schneider WJ, et al. Conserved synteny between the chicken Z sex chromosome and human chromosome 9 includes the male regulatory gene, DMRT1: A comparative (re)view on avian sex determination. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2000;89:67–78. doi: 10.1159/000015567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S. Chromosomes and sex linked genes. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Postlethwait JH, Woods IG, Ngo-Hazelett P, Yan YL, Kelly PD, Chu F, Huang H, Hill-Force A, Talbot WS. Zebrafish comparative genomics and the origins of vertebrate chromosomes. Genome Res. 2000;10:1890–1902. doi: 10.1101/gr.164800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond CS, Shamu CE, Shen MM, Seifert KJ, Hirsch B, Hodgkin J, Zarkower D. Evidence for evolutionary conservation of sex-determining genes. Nature. 1999;391:691–695. doi: 10.1038/35618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roest Crollius H, Jaillon O, Bernot A, Dasilva C, Bouneau L, Fischer C, Fizames C, Wincker P, Brottier P, Quétier F, et al. Estimate of human gene number provided by genome-wide analysis using Tetraodon nigroviridis DNA sequence. Nat Genet. 2000a;25:235–238. doi: 10.1038/76118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roest Crollius H, Jaillon O, Dasilva C, Ozouf-Costaz C, Fizames C, Fischer C, Bouneau L, Billault A, Quétier F, Saurin W, et al. Characterization and repeat analysis of the compact genome of the freshwater pufferfish Tetraodon nigroviridis. Genome Res. 2000b;10:939–949. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.7.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugarli EI, Adler DA, Borsani G, Tsuchiya K, Franco B, Hauge X, Disteche C, Chapman V, Ballabio A. Different chromosomal localization of the Clcn4 gene in Mus spretus and C57BL/6J mice. Nat Genet. 1995;10:466–471. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saifi GM, Chandra HS. An apparent excess of sex- and reproduction-related genes on the human X chromosome. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1999;226:203–209. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Enderle E, Schindler D, Schempp W. Chromosome banding and DNA replication patterns in bird karyotypes. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1989;52:139–146. doi: 10.1159/000132864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Nanda I, Guttenbach M, Steinlein C, Hoehn H, Schartl M, Haaf T, Weigend S, Fries R, Buerstedde J-M, et al. First report on chicken genes and chromosomes 2000. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2000;90:169–218. doi: 10.1159/000056772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty S, Griffin DK, Marshall Graves JA. Comparative painting reveals strong chromosome homology over 80 million years of bird evolution. Chrom Res. 1999;7:289–295. doi: 10.1023/a:1009278914829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Waterman M. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J Mol Biol. 1981;147:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JA, Sinclair AH, Watson JM, Marshall Graves JA. Genes on the short arm of the human X chromosome are not shared with the marsupial X. Genomics. 1991;11:339–345. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turelli M, Orr HA. The dominance theory of Haldane's rule. Genetics. 1995;140:389–402. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.1.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh B, Gilligan P, Brenner S. Fugu: A compact vertebrate reference genome. FEBS Lett. 2000;476:3–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01659-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JM, Spencer JA, Riggs AD, Marshall Graves JA. The X chromosome of monotremes shares a highly conserved region with the eutherian and marsupial X chromosome despite the absence of X chromosome inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1990;87:7125–7129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DL, Church DM, Lash AE, Leipe DD, Madden TL, Pontius JU, Schuler GD, Schriml LM, Tatusova TA, Wagner L, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information: 2002 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:13–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox SA, Watson JM, Spencer JA, Marshall Graves JA. Comparative mapping identifies the fusion point of an ancient mammalian X-autosomal rearrangement. Genomics. 1996;35:66–70. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods IG, Kelly PD, Chu F, Ngo-Hazelett P, Yan YL, Huang H, Postlethwait JH, Talbot WS. A comparative map of the zebrafish genome. Genome Res. 2000;10:1903–1914. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.12.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CI, Davis AW. Evolution of postmating reproductive isolation: The composite nature of Haldane's rule and its genetic bases. Am Nat. 1993;142:187–212. doi: 10.1086/285534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechner U, Wilda M, Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Vogel W, Fundele R, Hameister H. A high density of X-linked genes for general cognitive ability: A run-away process shaping human evolution. Trends Genet. 2001;17:697–701. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02446-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]