Abstract

The hypothesis that platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) plays an important role in repair of connective tissue has been difficult to test experimentally, in part because the disruption of any of the PDGF ligand and receptor genes is embryonic lethal. We have developed a method that circumvents the embryonic lethality of the PDGF receptor (R)β−/− genotype and minimizes the tendency of compensatory processes to mask the phenotype of gene disruption by comparing the behavior of wild-type and PDGFRβ−/− cells within individual chimeric mice. This quantitative chimera analysis method has revealed that during development PDGFRβ expression is important for all muscle lineages but not for fibroblast or endothelial lineages. Here we report that fibroblasts and endothelial cells, but not leukocytes, are dependent on PDGFRβ expression during the formation of new connective tissue in and around sponges implanted under the skin. Even the 50% reduction in PDGFRβ gene dosage in PDGFRβ+/− cells reduces fibroblast and endothelial cell participation by 85%. These results demonstrate that the PDGFRβ/PDGF B-chain system plays an important direct role in driving both fibroblast and endothelial cell participation in connective tissue repair, that cell behavior can be regulated by relatively small changes in PDGFRβ expression, and that the functions served by PDGF in wound healing are different from the roles served during development.

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) was first recognized, and later purified, based on its ability to stimulate the proliferation of many connective tissue cell types in culture (reviewed in Ref. 1 ). Platelets release the contents of their storage granules, including PDGF, when they are activated by contact with tissue or basement membrane exposed as a result of injury. This PDGF is proposed to stimulate the proliferation of nearby connective tissue cells and thus contribute to repair of the damage. At later times, PDGF may be delivered largely by macrophages that infiltrate the damaged tissue. Activated macrophages are a rich source of PDGF in culture, 2,3 and PDGF expression by activated macrophages in vivo is demonstrated by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical staining. 4-6 However, the importance of PDGF for wound healing has been difficult to determine experimentally. It has been demonstrated that addition of exogenous PDGF can accelerate healing in diabetic rats, 7 mice, 8 and humans 9,10 and can enhance granulation tissue formation in subcutaneous implants, 11-13 but this type of analysis demonstrates only that exogenous PDGF is capable of enhancing connective tissue cell proliferation in vivo. It does not prove that endogenous PDGF plays a significant role in granulation tissue formation and wound repair and does not distinguish between direct and indirect cell targets of PDGF action.

Mouse embryos that are homozygous for disruption of PDGF B-chain 14 or PDGFR receptor (R)β 15 die at or before birth and cannot be used to determine whether the PDGF B-chain/PDGFRβ system is important for wound healing. However, chimeric mice that are prepared by fusing wild-type and PDGFRβ−/− embryos are viable and develop into normal adults. 16 We have developed a method for using such chimeric mice to quantitate the role of PDGFRβ in vivo. 16 During the development of a chimera composed of a mixture of wild-type and PDGFRβ−/− cells, the PDGFRβ−/− cells are outcompeted by the wild-type control cells in cell lineages that depend on signaling through the PDGF receptor β-subunit. This competitive disadvantage becomes the basis for calculating the magnitude of the role of PDGFRβ in the development of different cell lineages. We found that PDGFRβ−/− cells do not participate efficiently in the formation of any muscle type, including vascular, gastrointestinal, skeletal, and cardiac muscle. However, PDGFRβ−/− cells do not show any detectable disadvantage in contributing to fibroblast, leukocyte, or endothelial cell lineages. The lack of effect of PDGFRβ disruption on fibroblast development is surprising, given that fibroblasts in embryos do express PDGFRβ and that fibroblasts are the most frequently studied cell type for cell culture analysis of signaling through PDGFRβ. Fibroblast proliferation during development must be driven by other factors. A good candidate is PDGF-AA acting through PDGFRα. Fibroblasts express very high levels of PDGFRα early in embryogenesis, and disruption of PDGFRα expression in the Patch mutation results in a reduction in fibroblasts throughout the embryo. 17,18

Is PDGFRβ also unimportant for connective tissue wound healing in adult animals? To determine the role of PDGFRβ expression in a model of wound healing, we implanted surgical sponges subcutaneously into adult chimeras and determined the effect of PDGFRβ genotype on the ability of different cell types to participate in granulation tissue formation within the implants. We found that fibroblasts and endothelial cells (but not leukocytes) were virtually excluded from developing granulation tissue unless they could express normal levels of PDGFRβ. This demonstrates that both fibroblasts and endothelial cells clearly do express PDGFRβ, and respond through it, during granulation tissue formation in adults, even though PDGFRβ expression is not important for fibroblasts or endothelial cells during development. The greatly diminished participation of PDGFRβ+/− cells demonstrates that even relatively small differences (twofold) in PDGFRβ expression level can profoundly affect the ability of cells to respond to PDGF and supports the suggestion that the up-regulation of PDGFRβ expression observed in many pathologies involving connective tissue cell proliferation is an important component of the regulation of connective tissue cell proliferation.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Chimeric Mice

Two strains of mice were used to prepare the chimeras. The control strain (SWR) was unmarked and PDGFRβ+/+. The experimental strain was C57BI6/J, homozygous for the unlinked pBR322/betaglobin marker (1000 tandem copies of pBR322 and human genomic globin sequence) in chromosome 3 19 and heterozygous for the PDGFRβ allele inactivated by homologous recombination. Mating PDGFRβ+/− heterozygotes generated all three experimental genotypes (PDGFRβ+/+, PDGFRβ+/−, and PDGFRβ−/−) as siblings, all of them homozygous for the pBR322/globin marker. To prepare chimeras, we collected morulae from pregnant experimental and control females at the eight-cell stage, fused control and experimental embryos ex vivo, and implanted them into pseudo-pregnant host females (Swiss Webster). The relative contributions of the two components to the chimeric offspring can be estimated from the coat color mosaicism that is created by colonization of skin by melanocyte precursors from either the C57BL6/J (black) or the SWR (white) components. Apart from coat color mosaicism, we have not observed any gross or histological difference between normal and chimeric adults, irrespective of the genotype of the experimental component (ie, PDGFRβ +/+, +/−, or −/−). To determine the genotype of the experimental component of a chimeric individual, a segment of tail was taken at two weeks after birth for DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction genotyping as described. 16

Identification of the Cells of the Experimental Component and Calculation of the Normalized Ratio (Rn)

This method is described in more detail in Crosby et al. 16 Briefly, we detected the integrated pBR322/globin genomic marker in cells of the experimental component using a pBR322 probe labeled with digoxigenin-conjugated UTP and visualized using diaminobenzidine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) as substrate for anti-digoxigenin-peroxidase using the Genius 1 kit from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN). Nuclei were counterstained with methyl green. Each cell type was scored by counting at least 1000 cells in 10 nonconsecutive sections. To calculate the normalized ratio (Rn), the value for percentage of globin-marked cell type of interest was divided by the value for percentage of globin-marked hepatocytes in the same chimera. This corrects for differences in relative frequency of cells of the experimental and control genotypes that result from random cell allocation events in early embryogenesis. 16 Without this correction, a much larger number of chimeras would need to be analyzed to detect the effect of genotype above the effect of random events.

Sponge Model of Granulation Tissue Formation

Polyvinyl alcohol sponges (IVALON, Unipont Industries, Thomasville, NC) were cut into small discs (5-mm diameter, 3 mm high) and implanted under the skin on the back of adult chimeric mice. Two incisions were made, one anterior and one posterior. Through each incision one sponge was inserted into the left side and another into the right side. The incisions were closed with wound clips. After 1 to 4 weeks, the mice were sacrificed, and the sponges were removed and fixed in methyl Carnoy’s fixative.

Identification of Cell Types

Immunohistochemical staining was performed before the non-isotopic in situ hybridization procedure used to identify the genomic marker. Leukocytes were identified using the pan-leukocyte marker CD45 using rat monoclonal anti-mouse CD45 (clone 30-F11, Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) followed by biotinylated rabbit anti-rat IgG and then Vectastain elite ABC peroxidase (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and visualized using diaminobenzidine. Endothelial cells were identified as flattened cells on the luminal side of the basement membrane identified using rabbit anti-mouse laminin (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA) followed by biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, Vectastain elite ABC peroxidase (Vector), and visualization using diaminobenzidine.

Results

Chimera Analysis of the Role of PDGFRβ in Granulation Tissue Formation

We produced chimeric mice by aggregating two different eight-cell embryos (see Materials and Methods). One component embryo (control component) was wild type and unmarked. The experimental component embryo was either PDGFRβ+/+, PDGFRβ+/−, or PDGFRβ−/− and was homozygous for the presence of the unlinked expression-independent nuclear marker (a large tandem array of pBR322 and promoterless human betaglobin sequences). The chimeras in which the experimental component is PDGFRβ+/+ served as negative controls for possible effects of factors other than the PDGFRβ genotype.

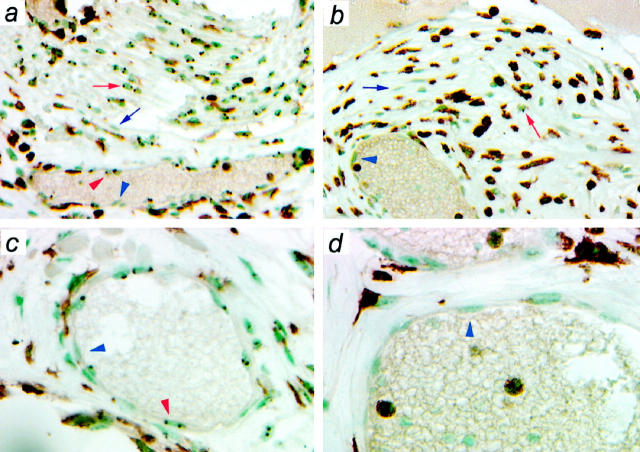

To determine the role of PDGFRβ in stimulating the different cell types involved in connective tissue repair, we evaluated the formation and maturation of granulation tissue in and around surgical sponges implanted under the skin of the back of adult chimeric mice. By 1 week after implantation, the sponges contained a loose extracellular matrix, a mononuclear cell infiltrate, and some capillaries. By 4 weeks, the sponges were filled with a denser connective tissue, which included capillaries, arterioles, venules, fibroblasts, and many leukocytes. The micrographs in Figure 1 ▶ show representative sections from sponges removed 4 weeks after implantation into chimeric adults in which the experimental component was PDGFRβ+/+ (Figure 1, a and c) ▶ or PDGFRβ−/− (Figure 1, b and d) ▶ . The experimental component cells are identified by dark nuclear dot(s) produced by non-isotopic in situ hybridization to the globin marker. In addition, these sections were immunostained for CD45 to identify leukocytes. In the micrograph from the chimera in which the experimental component was PDGFRβ+/+ (Figure 1, a and c) ▶ , nuclei marked by the globin dot(s) are found with equal frequency in all cell types in the section, including CD45-positive leukocytes, CD45-negative fibroblasts, and the CD45-negative endothelial cells lining the blood vessels, and shown at higher magnification in the lower panels. This confirms that the system is behaving as expected; ie, in the absence of a genetic difference between the marked experimental component and the unmarked control component cells, the two components behave indistinguishably. The panels on the right were taken from a sponge implanted into a chimera in which the marked experimental component is PDGFRβ−/−. It is apparent by inspection that the globin-marked PDGFRβ−/− cells are greatly outnumbered, and as described below, calculated values for Rn confirm this.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the two genotypes in connective tissue in sponges implanted in chimeras. Sponges were implanted into chimeras in which the globin-marked experimental component was PDGFRβ+/+ (a and c) or PDGFRβ−/− (b and d). After 4 weeks, the sponges were removed, immunostained for the leukocyte marker CD45, and then processed for in situ hybridization to visualize the genomic marker identifying the experimental component. Nuclei are counterstained with methyl green. a and b show areas of dense connective tissue formation. c and d show higher-magnification micrographs of blood vessels. The blue arrows (fibroblasts) and arrowheads (endothelial cells) indicate representative unmarked nuclei. The red arrows (fibroblasts) and arrowheads (endothelial cells) indicate representative marked nuclei (experimental component). It is difficult to distinguish the globin dots in the immunostained leukocytes in the micrograph but is relatively easy to do so under the microscope as the sections are scored.

Fibroblasts Require PDGFRβ Expression to Participate in Granulation Tissue Formation

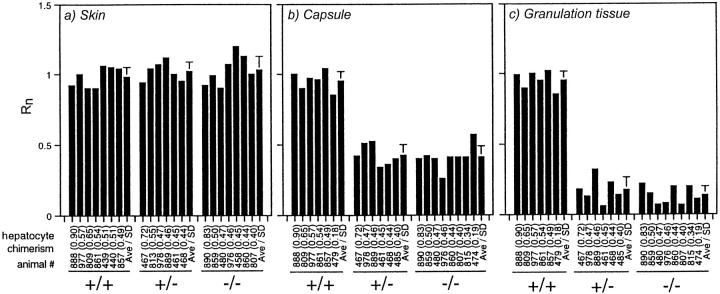

Figure 2 ▶ summarizes the data from chimera analysis of fibroblast participation in sponge granulation tissue. Data from individual chimeras are presented, along with the mean ± SD, to demonstrate that the results do not depend on the degree of chimerism and to illustrate the inter-individual consistency of this normalized measurement. In the unaffected skin distant from the sponges, the calculated Rn was 1.0 for fibroblasts of all experimental genotypes, including PDGFRβ−/−. This means that PDGFRβ expression is not necessary for dermal fibroblast proliferation during the development of the skin. This extends our earlier report that PDGFRβ expression does not affect the development of fibroblasts in the adventitia of blood vessels or in tendon. 16 However, the calculated Rn dropped to 0.40 for PDGFRβ−/− fibroblasts in the fibrous capsule that develops around the sponge; ie, there were only 40% as many PDGFRβ−/− fibroblasts as would be expected if PDGFRβ expression were unimportant. The calculated Rn dropped to 0.15 for PDGFRβ−/− fibroblasts within the sponge. Fibroblasts thus require signaling through PDGFRβ for formation of granulation tissue in adults even though they do not use this pathway during the initial formation of dermis during development.

Figure 2.

Participation of fibroblasts in granulation tissue formation as a function of PDGFRβ genotype. Sponges and segments of adjacent unaffected skin were collected 4 weeks after implantation, and the value of Rn was determined for fibroblasts in the unaffected skin (a), in the dense capsule surrounding the sponge (b), and within the sponge (c). Fibroblasts were identified as elongated cells that were negative for CD45 expression and were not within a blood vessel wall. Each bar without SD bars represents the value of Rn for one chimera. Below the bar are noted the animal number (to allow comparison with Rn determined for other tissues or cell types within a single chimera) and, in parentheses, the extent of chimerism as determined for hepatocytes and used in the calculation of Rn. The final bar in each group shows the average and the standard deviation.

The dose response for the effect of PDGFRβ expression level on fibroblast participation in granulation tissue formation is remarkably steep. Reducing PDGFRβ expression by 50% (in the PDGFRβ+/− cells) resulted in as great a reduction in granulation tissue participation as did complete elimination of expression (in the PDGFRβ−/− cells). By contrast, the effect of PDGFRβ expression level on participation of cells in muscle lineages during embryogenesis is graduated, with Rn = 0.5 for PDGFRβ+/−, and Rn = 0.15 for PDGFRβ−/−. 16

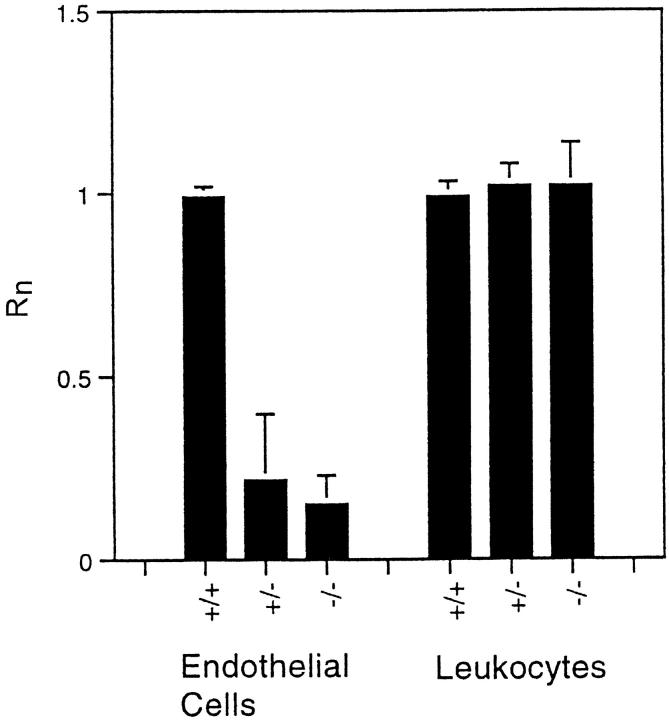

Vascular Endothelial Cells Require PDGFRβ Expression to Participate in Granulation Tissue Formation

There is little consensus in the literature as to whether, or under what circumstances, endothelial cells express PDGFRβ in vivo. Quantitative chimera analysis does not answer this question directly, but it does answer a more important question: is PDGFRβ expression by endothelial cells important for endothelial cells function in vivo? Chimera analysis allows this to be determined directly, at least for responses that change cell number or location, eg, migration and proliferation. In normal adult chimeras, PDGFRβ−/− endothelial cells are not under-represented in the endothelium of brain capillaries, which form by angiogenesis, or in the endothelium of the aorta, which forms by vasculogenesis. 16 This indicates that if endothelial cells do express PDGFRβ during embryogenesis, this PDGFRβ expression is not important for endothelial cell proliferation, migration, or survival. By contrast, Figure 3 ▶ demonstrates that PDGFRβ expression is very important for endothelial cell participation in angiogenesis during granulation tissue formation. The absence of PDGFRβ expression reduced endothelial cell participation by 85%, from Rn = 1.0 for endothelial cells in normal adult dermis to Rn = 0.15 for endothelial cells within the sponge. This reduction is as great as the reduction in fibroblast participation. It is thus clear that PDGFRβ plays a major role in endothelial cell participation in wound healing. Because chimera analysis measures the cell-autonomous effects of differences in gene expression, this also demonstrates that the endothelial cells themselves (or possible endothelial cell precursors) must express PDGFRβ during adult angiogenesis, and PDGF must be stimulating angiogenesis directly, and not by stimulating other cell types, to produce secondary angiogenic factors that then act on the endothelial cells.

Figure 3.

Participation of endothelial cells and leukocytes in granulation tissue formation as a function of PDGFRβ genotype. Values for Rn were determined from the same sponges used for Figure 2 ▶ . Only the average and standard deviations are plotted.

Leukocytes Are Not Affected by PDGFRβ Expression

Leukocytes, particularly macrophages, are abundant during granulation tissue formation and in the foreign body reaction. Figure 3 ▶ shows that Rn = 1.0 for leukocytes of all genotypes; ie, the appearance of leukocytes within the sponge is not affected by their ability to express PDGFRβ. This indicates that the increased number of leukocytes that has been observed in response to addition of exogenous PDGF 8,20 is probably not a direct effect of PDGF on leukocytes acting via PDGFRβ. Direct action via PDGFRα is a formal possibility, but there is no evidence that leukocytes can express this PDGF receptor. The increased numbers of leukocytes may be secondary consequences of the increased vascularity of the tissue or up-regulation of adhesion molecules or chemokine release from the increased numbers of activated endothelial cells, leukocytes, and fibroblasts.

Discussion

PDGFRβ Plays a Different Role in Granulation Tissue Formation from That in Development

The process of connective tissue wound healing results, when all goes well, in the re-establishment of normal adult tissue architecture. The quantitative chimera analysis above demonstrates, however, that the relative importance of factors that drive this process can be quite different from those that established the tissue architecture during development. PDGFRβ appears to play an important role in adult granulation tissue (this report) but not in the formation of connective tissue during development. 16 The difference could be due to greater availability of alternative growth factor/receptor systems during development, and/or to increased expression or availability of PDGFRβ and/or PDGF-BB in granulation tissue. In support of the second possibility, two pre-eminent sources of PDGF-BB, platelets and macrophages, are likely to play more important roles in response to injury, and in the foreign body reaction, than during development. The platelets that degranulate within the sponge implantation site, and the macrophages that subsequently enter and cover the sponge matrix, may act as local sources of PDGF-BB to recruit endothelial cells and fibroblasts from the surrounding loose connective tissue. The sequence during development appears to be different. The initial endothelial cell tubes appear to be established by other ligand/receptor systems (reviewed in Refs. 21 and 22 ), and these in turn recruit smooth muscle cells via production of PDGF-BB. 16,23,24 The fibroblasts/mesenchymal cells that surround the smooth muscle cell layer are relatively far from the endothelial cells and may be responding primarily to PDGF-AA produced by the smooth muscle cells or, in other tissues, by epithelial cells. 17 During development, fibroblasts express relatively high levels of PDGFRα, the obligate receptor for PDGF-AA, 25 and disruption of PDGFRα, but not PDGFRβ, leads to a severe deficiency in fibroblasts. 17,18 In adult connective tissues, by contrast, PDGFRα expression has decreased dramatically, but PDGFRβ expression is still easily detectable, and PDGFRβ expression is up-regulated in many pathological states.

PDGF Acts Directly on Fibroblasts and Endothelial Cells but Not on Leukocytes

A second question about the role of PDGF is whether it directly stimulates the different cell types that participate in granulation tissue formation or whether some cell types are affected indirectly via PDGF-induced production of other growth factors or cytokines. Fibroblasts are the most commonly studied PDGF-responsive cell type. For cultured fibroblasts, PDGF is clearly active as a direct mitogen and chemotactic agent, 1,26,27 and it is reasonable to propose that PDGF acts directly on this cell type in vivo. Other cell types are more problematic. Leukocytes are not generally found to express detectable PDGF receptors, but there are reported exceptions. Monocytes/macrophages have been reported to express PDGFRβ 28,29 and to be chemotactically attracted to PDGF. 30-32 Chimera analysis demonstrates that expression of PDGFRβ (if it does occur) is not necessary for normal development of leukocyte lineages during development 16 or for leukocyte participation in granulation tissue formation.

Capillaries and small blood vessels are the third prominent component of granulation tissue. Published data do not agree as to whether/when vascular endothelial cells express PDGFRβ. A few cultured endothelial cell lines do express PDGF receptors, 33,34 and PDGF receptors have been reported to be expressed in vivo by endothelial cells in areas of active capillary formation, including tumor angiogenesis, 35 inflammation, 36 and the developing placenta. 23 Addition of PDGF-BB to the chick chorioallantoic membrane stimulates increased vessel density without accompanying inflammation, indicating that the increase is not an indirect effect mediated via recruitment of leukocytes. 37 When endothelial cell tube formation was studied in vitro, as a model for angiogenesis, large-vessel endothelial cells were reported to express PDGFRβ only when participating in tube formation, and the process of tube formation was inhibited by neutralizing antibodies to PDGF-BB. 38 When studied using cultured microvascular endothelial cells, PDGFRβ was reported to be expressed in monolayer but not three-dimensional culture. 34 A consensus view of published studies of PDGF receptor expression by endothelial cells might be that endothelial cells can, under some circumstances, express PDGFRβ. The results of chimera analysis demonstrate that PDGFRβ expression by endothelial cells is not important for the formation of the endothelium of vessels during development but is important for driving the formation of new vessels in granulation tissue.

Regulation of PDGFRβ Expression Level Is an Effective Regulator of Cell Responsiveness in Culture and in Vivo

A role for PDGFRβ in proliferation of connective tissue cells in adult pathologies has been suggested by many immunohistochemical studies demonstrating that expression of PDGFRβ is up-regulated in pathological or reactive states that are accompanied by connective tissue cell proliferation. For example, expression of PDGFRβ by dermal fibroblasts increases in skin wounds 39 and in disorders with significant fibroblast proliferation. 40,41 Expression of PDGFRβ by stromal cells increases in rheumatoid arthritis 42 and renal transplants. 43 As increased PDGFRβ expression correlates with cell proliferation in vivo, it has been proposed that the up-regulation of PDGF receptor expression is an important permissive factor for this proliferation. However, the relationship between level of PDGFR expression and responsiveness to PDGF has been difficult to establish experimentally. When cultures of human fibroblasts were incubated with increasing concentrations of blocking anti-PDGFRβ antibody, mitogenic responsiveness and available receptor number decreased in parallel. 44 This supports the hypothesis that the level of PDGFR expression can limit/regulate responsiveness to PDGF in culture, but it does not provide information about the relationship between PDGFR expression level and responsiveness in vivo. We can use the behavior of PDGFRβ+/+, PDGFRβ+/−, and PDGFRβ−/− fibroblasts in chimeras to generate a three-point dose-response curve in vivo: 100%, 50%, and 0% of normal PDGFRβ expression. The measured Rn values for fibroblasts within the sponge demonstrate that reducing PDGFRβ expression by 50% is sufficient to reduce fibroblast participation to a baseline value. This means that fibroblast behavior is remarkably sensitive to relatively small changes in PDGFRβ expression level and that the changes in PDGFRβ expression observed in various disease states could be sufficient to regulate cell response to PDGF, just as two-fold changes in PDGFRβ expression level during development are sufficient to affect the proliferation of muscle and muscle-like cells during development. 16

The results of chimera analysis thus demonstrate that the role of PDGFRβ expands from involvement in muscle cell proliferation/migration during development to motivation of fibroblast and endothelial cell participation in connective tissue repair in adult disease and that even relatively small changes in PDGFRβ expression in vivo, well within the range observed in disease, are capable of significantly affecting the ability of cells to participate in these processes.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Daniel F. Bowen-Pope, University of Washington, Department of Pathology, Box 357470, Seattle, WA 98195-7470. E-mail: bp@u.washington.edu.

Supported by NIH grant HL03174.

References

- 1.Ross R, Raines EW, Bowen-Pope DF: The biology of platelet-derived growth factor. Cell 1986, 46:155-169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinet Y, Bitterman PB, Mornex JF, Grotendorst GR, Martin GR, Crystal RG: Activated human monocytes express the c-sis proto-oncogene and release a mediator showing PDGF-like activity. Nature 1986, 319:158-160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimokado K, Raines EW, Madtes DK, Barrett TB, Benditt EP, Ross R: A significant part of macrophage-derived growth factor consists of at least two forms of PDGF. Cell 1985, 43:277-286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mornex JF, Martinet Y, Yamauchi K, Bitterman PB, Grotendorst GR, Chytil-Weir A, Martin GR, Crystal RG: Spontaneous expression of the c-sis gene and release of a platelet-derived growth factor-like molecule by human alveolar macrophages. J Clin Invest 1986, 78:61-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross R, Masuda J, Raines EW, Gown AM, Katsuda S, Sasahara M, Malden LT, Masuko H, Sato H: Localization of PDGF-B protein in macrophages in all phases of atherogenesis. Science 1990, 248:1009-1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraiss LW, Raines EW, Wilcox JN, Seifert RA, Barrett TB, Kirkman TR, Hart CE, Bowen-Pope DF, Ross R, Clowes AW: Regional expression of the platelet-derived growth factor and its receptors in a primate graft model of vessel wall assembly. J Clin Invest 1993, 92:338-348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grotendorst GR, Martin GR, Pencev D, Sodek J, Harvey AK: Stimulation of granulation tissue formation by platelet-derived growth factor in normal and diabetic rats. J Clin Invest 1985, 76:2323-2329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenhalgh DG, Sprugel KH, Murray MJ, Ross R: PDGF and FGF stimulate wound healing in the genetically diabetic mouse. Am J Pathol 1990, 136:1235-1246 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knighton DR, Ciresi KF, Fiegel VD, Austin LL, Butler EL: Classification and treatment of chronic nonhealing wounds: successful treatment with autologous platelet-derived wound healing factors (PDWHF). Ann Surg 1986, 204:322-330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierce GF, Tarpley JE, Tseng J, Bready J, Chang D, Kenney WC, Rudolph R, Robson MC, Vande Berg J, Reid P, Kaufman P, Farrell CL: Detection of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-AA in actively healing human wounds treated with recombinant PDGF-BB and absence of PDGF in chronic nonhealing wounds. J Clin Invest 1995, 96:1336-1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeGrand EK, Senter LH, Gamelli RL, Kiorpes TC: Evaluation of PDGF-BB, PDGF-AA, bFGF, IL-1, and EGF dose responses in polyvinyl alcohol sponge implants assessed by a rapid histologic method. Growth Factors 1993, 8:315-329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lepisto J, Laato M, Niinikoski J, Lundberg C, Gerdin B, Heldin CH: Effects of homodimeric isoforms of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF-AA and PDGF-BB) on wound healing in rat. J Surg Res 1992, 53:596-601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royce PM, Kato T, Ohsaki K, Miura A: The enhancement of cellular infiltration and vascularisation of a collagenous dermal implant in the rat by platelet-derived growth factor BB. J Dermatol Sci 1995, 10:42-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leveen P, Pekny M, Gebre-Medhin S, Swolin B, Larsson E, Betsholtz C: Mice deficient for PDGF B show renal, cardiovascular, and hematological abnormalities. Genes Dev 1994, 8:1875-1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soriano P: Abnormal kidney development and hematological disorders in PDGF beta-receptor mutant mice. Genes Dev 1994, 8:1888-1896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crosby JR, Seifert RA, Soriano P, Bowen-Pope DF: Chimaeric analysis reveals role of Pdgf receptors in all muscle lineages. Nature Genet 1998, 18:385-388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orr-Urtreger A, Lonai P: Platelet-derived growth factor-A and its receptor are expressed in separate, but adjacent cell layers of the mouse embryo. Development 1992, 115:1045-1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schatteman GC, Morrison-Graham K, van Koppen A, Weston JA, Bowen-Pope DF: Regulation and role of PDGF receptor alpha-subunit expression during embryogenesis. Development 1992, 115:123-131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo CW, Coulling M, Kirby C: Tracking of mouse cell lineage using microinjected DNA sequences: analyses using genomic Southern blotting and tissue-section in situ hybridizations. Differentiation 1987, 35:37-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lepisto J, Kujari H, Niinikoski J, Laato M: Effects of heterodimeric isoform of platelet-derived growth factor PDGF-AB on wound healing in the rat. Eur Surg Res 1994, 26:267-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folkman J, D’Amore PA: Blood vessel formation: what is its molecular basis? Cell 1996, 87:1153-1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanahan D: Signaling vascular morphogenesis and maintenance. Science 1997, 277:48-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmgren L, Glaser A, Pfeifer-Ohlsson S, Ohlsson R: Angiogenesis during human extraembryonic development involves the spatiotemporal control of PDGF ligand and receptor gene expression. Development 1991, 113:749-754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirschi KK, Rohovsky SA, Pa DA: PDGF, TGF-beta, and heterotypic cell-cell interactions mediate endothelial cell-induced recruitment of 10T1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate [published erratum appears in J Cell Biol 1998 Jun 1;141(5): 1287]. J Cell Biol 1998, 141:805-814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seifert RA, Hart CE, Phillips PE, Forstrom JW, Ross R, Murray MJ, Bowen-Pope DF: Two different subunits associate to create isoform-specific platelet-derived growth factor receptors. J Biol Chem 1989, 264:8771-8778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seppa H, Grotendorst G, Seppa S, Schiffmann E, Martin GR: Platelet-derived growth factor in chemotactic for fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 1982, 92:584-588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senior RM, Griffin GL, Huang JS, Walz DA, Deuel TF: Chemotactic activity of platelet alpha granule proteins for fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 1983, 96:382-385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inaba T, Shimano H, Gotoda T, Harada K, Shimada M, Ohsuga J, Watanabe Y, Kawamura M, Yazaki Y, Yamada N: Expression of platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor on human monocyte-derived macrophages and effects of platelet-derived growth factor BB dimer on the cellular function. J Biol Chem 1993, 268:24353-24360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan XQ, Brady G, Iscove NN: Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) activates primitive hematopoietic precursors (pre-CFCmulti) by up-regulating IL-1 in PDGF receptor-expressing macrophages. J Immunol 1993, 150:2440-2448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Senior RM, Huang JS, Griffin GL, Deuel TF: Dissociation of the chemotactic and mitogenic activities of platelet-derived growth factor by human neutrophil elastase. J Cell Biol 1985, 100:351-356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams LT, Antoniades HN, Goetzl EJ: Platelet-derived growth factor stimulates mouse 3T3 cell mitogenesis and leukocyte chemotaxis through different structural determinants. J Clin Invest 1983, 72:1759-1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deuel TF, Senior RM, Huang JS, Griffin GL: Chemotaxis of monocytes and neutrophils to platelet-derived growth factor. J Clin Invest 1982, 69:1046-1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beitz JG, Kim IS, Calabresi P, Frackelton AR, Jr: Human microvascular endothelial cells express receptors for platelet-derived growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991, 88:2021-2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marx M, Perlmutter RA, Madri JA: Modulation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor expression in microvascular endothelial cells during in vitro angiogenesis. J Clin Invest 1994, 93:131-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermansson M, Nister M, Betsholtz C, Heldin CH, Westermark B, Funa K: Endothelial cell hyperplasia in human glioblastoma: coexpression of mRNA for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) B chain and PDGF receptor suggests autocrine growth stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988, 85:7748-7752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reuterdahl C, Tingstrom A, Terracio L, Funa K, Heldin CH, Rubin K: Characterization of platelet-derived growth factor beta-receptor expressing cells in the vasculature of human rheumatoid synovium. Lab Invest 1991, 64:321-329 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Risau W, Drexler H, Mironov V, Smits A, Siegbahn A, Funa K, Heldin CH: Platelet-derived growth factor is angiogenic in vivo. Growth Factors 1992, 7:261-266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Battegay EJ, Rupp J, Iruela-Arispe L, Sage EH, Pech M: PDGF-BB modulates endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis in vitro via PDGF beta-receptors. J Cell Biol 1994, 125:917-928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krane JF, Murphy DP, Gottlieb AB, Carter DM, Hart CE, Krueger JG: Increased dermal expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptors in growth-activated skin wounds and psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 1991, 96:983-986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klareskog L, Gustafsson R, Scheynius A, Hallgren R: Increased expression of platelet-derived growth factor type B receptors in the skin of patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 1990, 33:1534-1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smits A, Funa K, Vassbotn FS, Beausang-Linder M, af Ekenstam F, Heldin CH, Westermark B, Nister M: Expression of platelet-derived growth factor and its receptors in proliferative disorders of fibroblastic origin. Am J Pathol 1992, 140:639-648 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubin K, Tingstrom A, Hansson GK, Larsson E, Ronnstrand L, Klareskog L, Claesson-Welsh L, Heldin CH, Fellstrom B, Terracio L: Induction of B-type receptors for platelet-derived growth factor in vascular inflammation: possible implications for development of vascular proliferative lesions. Lancet 1988, 1:1353-1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fellstrom B, Klareskog L, Heldin CH, Larsson E, Ronnstrand L, Terracio L, Tufveson G, Wahlberg J, Rubin K: Platelet-derived growth factor receptors in the kidney upregulated expression in inflammation. Kidney Int 1989, 36:1099-1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barrett TB, Seifert RA, Bowen-Pope DF: Regulation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor expression by cell context overrides regulation by cytokines. J Cell Physiol 1996, 169:126-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]