Abstract

Platelet-activating factor (PAF) is a potent lipid autocoid involved in numerous inflammatory processes. Although PAF plays a key role as a mediator of inflammation in acute pancreatitis, the site(s) of action of PAF in the pancreas remains unknown. One of the aims of this study was to identify cell types within the pancreas expressing the PAF receptor using immunohistochemical protocols. Additionally, pancreatic microvascular endothelial cells were isolated and examined for the PAF receptor using immunohistochemistry, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, and intracellular calcium responses to PAF exposure. Immunohistochemical analysis of pancreatic slices using an antibody directed toward the N-terminus of the PAF receptor revealed specific localization to the vascular endothelium with no localization to other pancreatic cell types. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction of RNA isolated from cultured pancreatic islet endothelial cells yielded the predicted amplicon for the PAF receptor. Cultured pancreatic islet endothelial cells responded to PAF as measured by a transient increase in intracellular calcium, which was ameliorated in the presence of a PAF receptor antagonist. The results demonstrate the localization of PAF receptors on the pancreatic vascular endothelium. The presence of PAF receptors on the pancreatic vascular endothelium provides a defined, highly localized target for therapeutic intervention.

Platelet-activating factor (PAF) is a phosphatidylcholine molecule containing a long chain alkyl ether moiety in the sn-1 position that is acetylated at the sn-2 position. 1 The biological activity of PAF occurs though its specific receptor, which is a member of the G-protein-coupled receptor superfamily, and leads to the activation of multiple signaling pathways. 2 This unique phospholipid acts to mediate a host of biochemical activities including angiogenesis, inflammation, and reproduction. 3,4

Elevated levels of PAF have been associated with a variety of pathophysiological conditions including acute pancreatitis (AP). 5,6 Elevated PAF levels have been observed in the pancreas following instigation of AP in several model systems. 7,8 PAF is involved in early inflammatory events of AP and very likely is generated as a consequence of a substantial increase in intracellular calcium leading to a stimulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. 9 Pretreatment with specific PAF receptor antagonists WEB-2170, BN52021, and BB-882 attenuates the severity of AP in animal models 8,10,11 and in fact, BB-882 has shown efficacy in Phase II clinical trials in patients diagnosed with mild episodes of AP. 12 Hence, although it is clear that PAF plays a key role in the course of AP, the precise cellular target for PAF associated with pancreatitis has not been determined.

Identifying tissues and cell types expressing the PAF receptor has been rendered feasible following the generation of specific probes for the PAF receptor. Commonly, the presence of the PAF receptor has been inferred primarily from radioligand binding studies in whole tissues or cultured cells or from the instigation of a signaling response following application of PAF. Following the cloning of the PAF receptor 13 and development of antibodies to it, 14 definitive localization of PAF receptors in several tissues has been reported. 14-16 Recently, an antibody directed against the N-terminus of the PAF receptor was reported to recognize a protein with the apparent molecular weight of 38–39 kd, corresponding to the predicted molecular mass of the PAF receptor. 14 The binding of this antibody to its target protein could be minimized by PAF, suggesting its specificity for the PAF receptor.

In this study, we demonstrated localization of PAF receptors on the vascular endothelium in the pancreas using immunohistochemical techniques, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and PAF-evoked changes in intracellular calcium measurements. This is important information because it allows us to rationalize the efficacy of PAF receptor antagonists in the intervention of inflammatory episodes in the pancreas.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Characterization of Pancreatic Islet Endothelial Cells (PIEC)

Pancreatic endothelial cells were cultured from pancreatic islets isolated from male Sprague-Dawley rats as previously described. 17 Briefly, pancreatic islets were harvested by collagenase digestion, then isolated using centrifugation on a tertiary Ficoll gradient. Isolated whole islets were rinsed, suspended in RPMI-1640 containing 20% fetal calf serum and endothelial cell growth supplement (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and placed in a collagen-coated 24-well culture plate. After 5–8 days, islets were removed from endothelial cell outgrowths and endothelial cells were passaged onto 24-well plates (Falcon Primaria, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). An endothelial cell phenotype was characterized by immunohistochemistry using Ox-2 and von Willebrand factor antibodies.

Isolation of Whole Pancreas, Isolated Acini, and PIEC RNA and RT-PCR

Whole intact pancreas was excised, quickly rinsed in saline, and immediately frozen using liquid nitrogen-cooled tongs. A small section of pancreas was ground finely with a liquid nitrogen-cooled mortar and pestle and homogenized in ice-cold Trizol (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). Pancreatic acinar cells were isolated as previously described using collagenase digestion. 18,19 Isolated pancreatic acini were pelleted, then homogenized in ice-cold Trizol. Cultured PIEC were bathed with ice-cold Trizol and scraped from the culture dish and the Trizol mixture was pipetted vigorously. All tissue-Trizol mixtures were frozen at −80°C. The Trizol mixtures were thawed and total RNA isolated as described in the manufacturer’s instructions.

cDNA was generated by reverse transcription for 60 minutes at 42°C. The reaction mixture (30 μl) contained 500 ng template RNA, 6 μl 5× 1st Strand Buffer (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), 5 μmol/L dNTPs, 4 μmol/L random hexamers, 6 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 20 U RNAsin, and 30 U Superscript reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). PCR reactions (30 μl) contained 15 μl RT reaction, 1.5 μl 10× PCR Buffer (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA), 50 pmol sense and antisense primers, and 2.5 U AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA). PCR conditions for PAF receptor were 94°C (3 minutes); 94°C (40 seconds), 71°C (40 seconds), and 72°C (40 seconds) for 38 cycles; 72°C (7 minutes); and 4°C hold. PCR conditions for β-actin were 4°C (3 minutes); 94°C (40 seconds), 59°C (40 seconds), 72°C (40 seconds) for 32 cycles; 72°C (7 minutes); 4°C hold. Primers for PAF receptor and β-actin were prepared as previously reported. 15

Immunohistochemistry

A small portion of the head of the pancreas was removed, immersed in cryopreservative OCT (Tissue Tek, Miles, Inc., Elkhart, IN), and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen-chilled isopentane. Slices of pancreas (5 um) were cut using a cryotome, mounted on slides, and immediately fixed in paraformaldehyde-lysine-periodate solution (60 minutes at room temperature). All remaining steps of sample preparation were performed at room temperature.

Samples were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then incubated in PBS containing 0.1 mol/L glycine (30 minutes). Following 3 washes with PBS, pancreatic slices were incubated with normal goat serum in PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (PBS-BSA) for 30 minutes. After rinsing with PBS-BSA (3 × 5 minutes), the samples were incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody directed toward the N-terminus of the PAF receptor (1:250 for 2 hours) (provided by Dr. Dan Predescu, University of California, San Diego). The slices were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:500 for 1 hour), rinsed with PBS-BSA (3 × 5 minutes), and incubated with 0.015% H2O2 + 0.05% diaminobenzidene solution for color development. Following a tap water rinse, all samples were counterstained with hematoxylin and coverslips were mounted. Cultured pancreatic endothelial cells were evaluated by immunohistochemistry using the same procedures described for tissue samples, except for the use of Vector VIP color development reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) instead of diaminobenzidine. Ox-2 (Serotec, Washington, DC) and von Willebrand factor (ICN, Costa Mesa, CA) antibodies were used to identify endothelial cells within the pancreas (1:10 for 4 hours and 1:50 for 45 minutes, respectively).

Measurement of Intracellular Calcium Response

PIEC were cultured on coverslips until confluent. Cells were rinsed twice with loading buffer, then incubated with Fura-2 for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were rinsed three times with loading buffer then kept at room temperature in the dark until use within 30 minutes. Coverslips were mounted in the microscope well chamber, bathed with 1 ml of 37°C buffer, and placed on a heated microscope stage. Following several minutes for equilibration, cells were visualized using an inverted phase microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with a CCD camera attachment (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ) connected to a PC running Image-1/FL software (Universal Imaging Corp., West Chester, PA). The fluorescence intensities at 340 and 380 nm were adjusted to create a 340/380 nm ratio ≤ 1. The cells were exposed to PAF (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) or thrombin (Sigma) and the intensity of the 340/380 nm ratio was recorded. For Lexipafant treatment, cells were bathed with 1 ml of 37°C buffer containing 100 nmol/L Lexipafant (BB-882; British Biotech Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Oxford, UK) followed by addition of PAF, then thrombin.

Results

Numerous mammalian cells that participate in inflammatory sequences have been shown to possess PAF-signaling capabilities. The pancreas is no exception; in fact, the pancreas is one of the most PAF-sensitive tissues. 20 Despite this condition, nothing is known about the precise localization of PAF receptors in the various cells of the pancreas. This turns out to be an important question, especially when considering therapeutic interventions that involve PAF receptor antagonists.

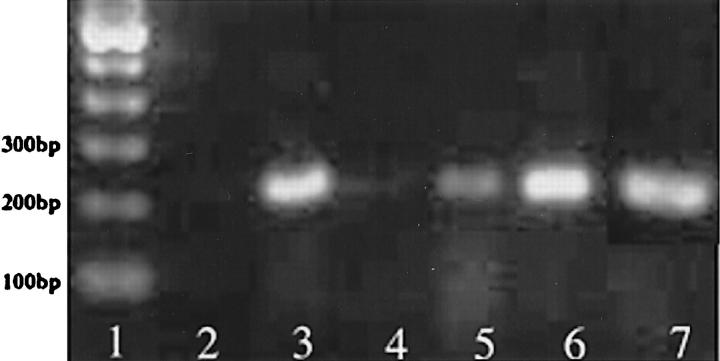

Expression of PAF receptors was accomplished using RT-PCR of total RNA isolated from whole pancreas, freshly isolated acinar cells, and cultured PIEC. PIEC generated the predicted 224-bp amplicon for the PAF receptor, but the intensity of the amplicon for whole pancreas and freshly isolated acinar cells was nearly undetectable using equivalent amounts of total RNA for RT-PCR (Figure 1) ▶ . The identity of the amplicon as the PAF receptor was confirmed by sequence and Southern blot analysis (data not shown). PCR of β-actin was performed as a measure of RNA quality. All samples showed strong β-actin amplicons after PCR (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel of RT-PCR using primers for PAF receptor. Lane 1: 100-bp ladder; Lane 2: water; Lane 3: PIEC; Lane 4: AR42J; Lane 5: freshly isolated dispersed acini; Lane 6: kidney; Lane 7: pancreas.

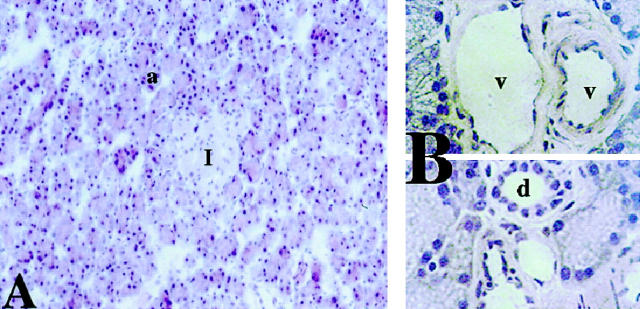

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of normal rat pancreas distinguished clearly among the various pancreatic cell types (Figure 2, A ▶ -C). Acinar cells are identified by their triangular morphology as part of a hexagonal acinar unit, whereas islets appear as distinct pinkish circular regions (Figure 2A) ▶ . At higher magnification, vascular endothelial cells can be visualized as a distinct monolayer lining blood vessels (Figure 2B) ▶ and ductal cells are distinguished by cuboidal morphology (Figure 2C) ▶ .

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of rat pancreas. A: 40× magnification showing acinar cell unit (a) and islet (I). B, upper panel: 100× magnification showing pancreatic microvessels (v) with endothelial cell lining (ec); lower panel : 100× magnification showing pancreatic duct (d).

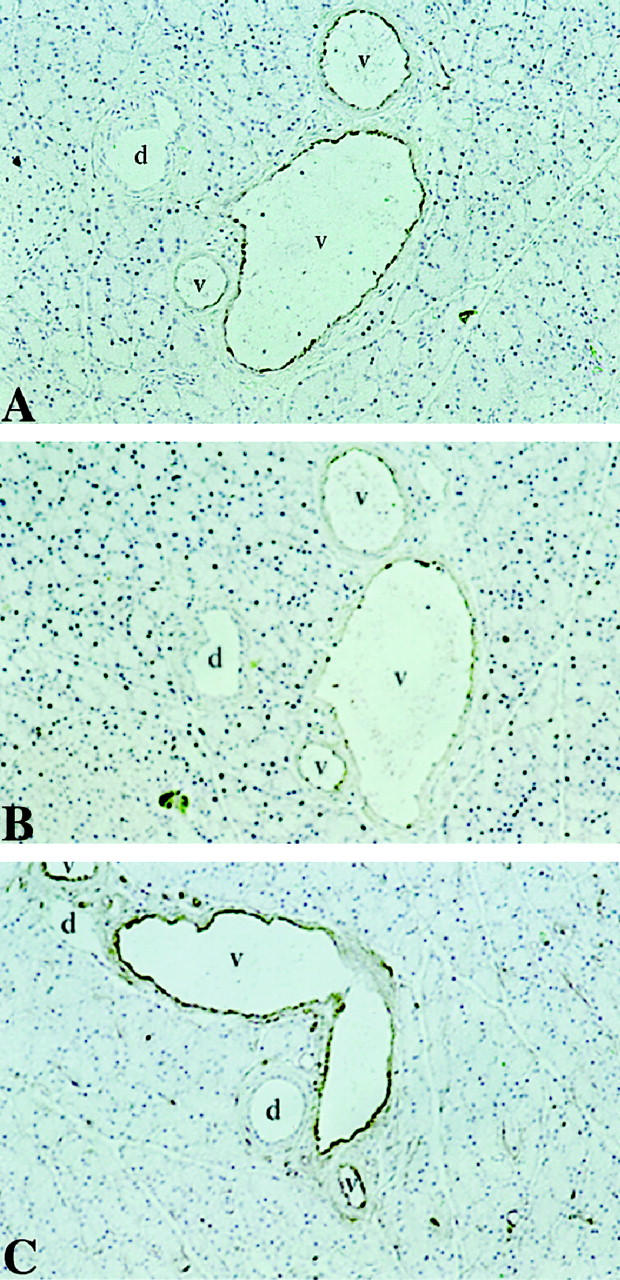

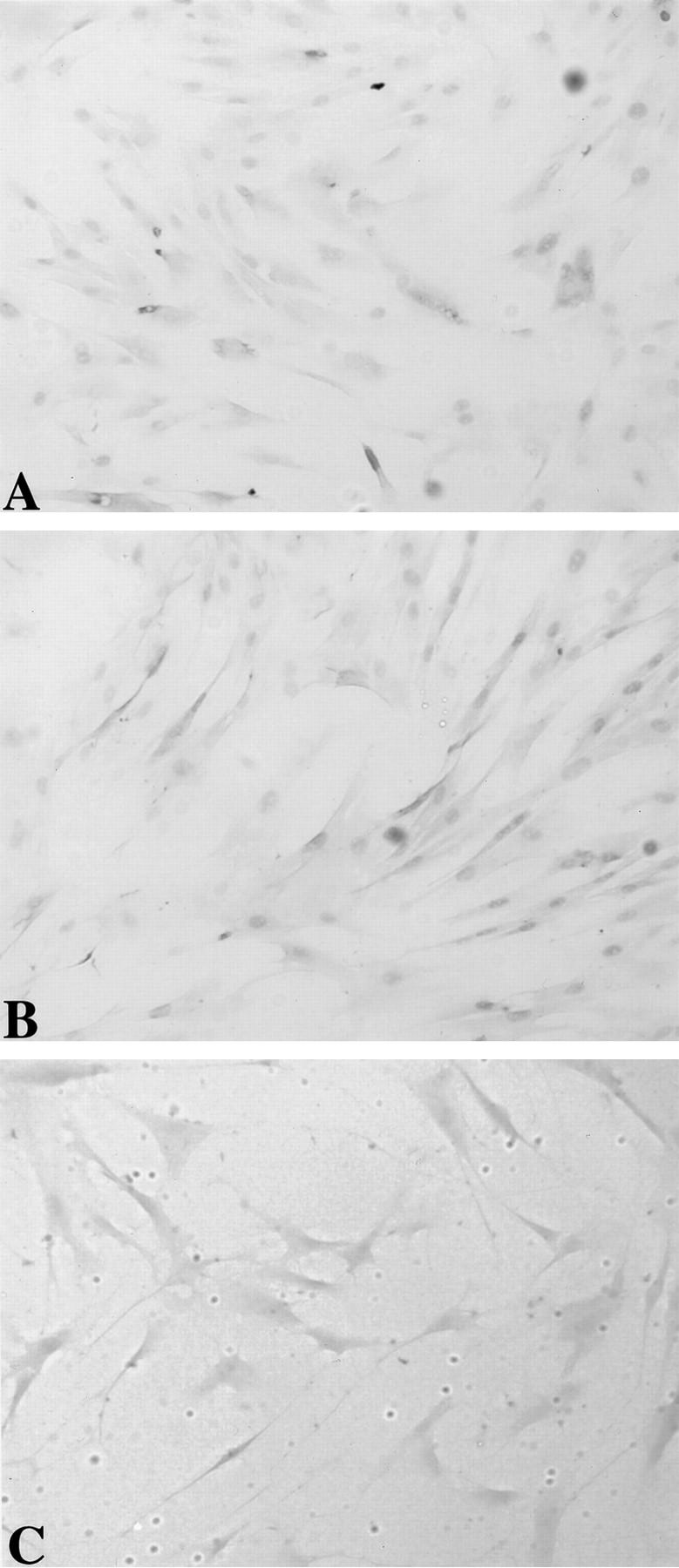

The availability of antibodies specific for the PAF receptor allowed us to develop an immunocytochemical approach for defining cellular target(s) of PAF in the pancreas. Immunohistochemical analysis using the N-terminal PAF receptor antibody localized the PAF receptor to the endothelium in intact pancreas slices and cultured pancreatic endothelial cells (Figures 3A and 4A ▶ ▶ , respectively). Pancreatic cell types such as acinar, ductal, and β (islet) cells do not demonstrate reactivity with the PAF receptor antibody in whole pancreas. The endothelial cell-specific antibodies von Willebrand factor and Ox-2 also localized to the vascular endothelium of the intact pancreas and cultured endothelial cells, clearly the same target cells as observed for the PAF receptor antibody (Figures 3, B and C and 4 ▶ ▶ , B and C, respectively).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry of rat pancreas using PAF receptor antibody (A), von Willebrand factor antibody (B), and Ox 2 antibody (C). Antibody-associated HRP activity visualized using diaminobenzidine and tissue counterstained with hematoxylin.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of rat PIEC using PAF receptor antibody (A), von Willebrand factor antibody (B), and Ox 2 antibody (C). Antibody-associated HRP activity visualized using Vector VIP.

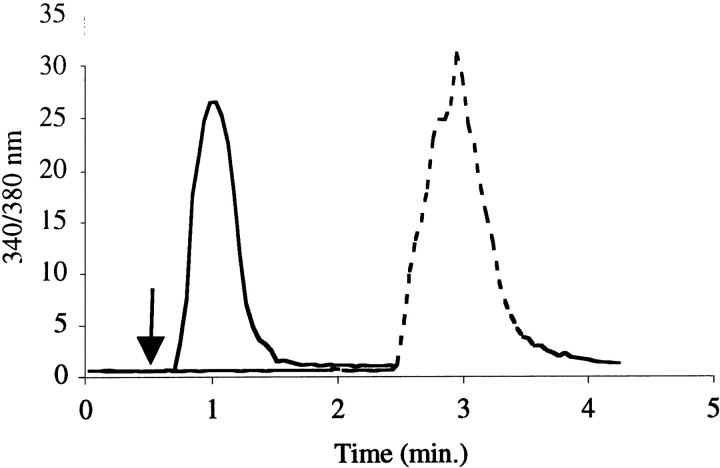

To generate evidence supportive of this in situ localization of PAF receptors, functional evidence of PAF-evoked signaling was sought in cultured pancreatic endothelial cells. Pancreatic endothelial cells isolated from cultured islets responded to PAF as indicated by an increase in intracellular calcium, measured using the fluorescent calcium-chelating probe Fura-2 (Figure 5) ▶ . These experiments indicated that pancreatic endothelial cells responded to PAF at low nanomolar concentrations. The use of the PAF receptor antagonist Lexipafant ameliorated the intracellular calcium response to PAF by pancreatic endothelial cells (Figure 5) ▶ . Pancreatic endothelial cells treated with Lexipafant maintained the ability to generate an intracellular calcium signal, as indicated by their response to thrombin.

Figure 5.

Intracellular calcium measurements in rat PIEC following exposure to PAF (100 nmol/L). Solid line represents intracellular calcium change in PIEC exposed to PAF. Dotted line represents intracellular calcium change in PIEC preincubated with Lexipafant and exposed to PAF, followed by thrombin stimulation.

Discussion

It has been well established that elevated PAF levels are associated with numerous pathophysiological conditions. 21,22 Experimental evidence has shown the importance of PAF in episodes of acute pancreatitis; in fact, PAF itself induces acute pancreatic inflammation. 23 In a secretagogue-hyperstimulation model, an increased PAF level in pancreatic tissue occurs on exposure to pathophysiological doses of cerulein. 8 The severity of cerulein-induced AP in rats has been minimized by the administration of PAF receptor antagonists. Our laboratory has shown the efficacy of WEB-2170 pretreatment in reducing pancreatic edema, leukocyte infiltration, and vascular permeability in cerulein-induced AP. 8 BN52021 and BB-882 have been shown to ameliorate the intensity of the inflammatory response in the secretagogue-hyperstimulation model of AP. 7,24 BB-882 has demonstrated the most potential in ameliorating mild, edematous AP in humans, as reflected by its current use in Phase III clinical trials. 6

The sequence of inflammatory events during acute pancreatitis remains unclear. Relatively little is known about PAF metabolism and its mechanism(s) of action on pancreatic cell types. In vitro and in vivo evidence indicate that pancreatic acini synthesize PAF in response to secretagogue hyperstimulation. 7,8,25 Elevated intracellular calcium levels evoked after initiation of acinar trauma by secretagogue hyperstimulation activate cytosolic calcium-dependent phospholipase A2, which hydrolizes membrane ether phospholipids generating 2-lyso-PAF necessary for PAF synthesis via the remodeling pathway. 8,26 Whether duct and/or endocrine cells of the pancreas synthesize PAF is unknown. Potential cellular targets of PAF include pancreatic cells (endocrine and exocrine), vascular cells, and circulating immune cells. In numerous models of inflammation, PAF has been shown to act through its specific receptor on target cells, leading to elevated intracellular calcium levels followed by production of additional mediators and to changes in vascular permeability characteristic of the inflammatory involvement of the tissue. 27-29

In general terms, the involvement of the vascular endothelium in inflammatory responses has been carefully and extensively defined. 30 Endothelial cells have been shown to respond to a variety of stimuli leading to the synthesis and expression of regulators critical to recruitment of circulating immune cells to inflamed tissues. Endothelial cells both respond to and synthesize PAF. Endothelial cells bind PAF, resulting in increased intracellular calcium, inositol phosphate production, and protein kinase C activity. 31-33 PAF synthesis by endothelial cells is elicited by a variety of inflammatory mediators including PAF itself, thrombin, and interleukin-1. 34,35

The effect of PAF on the recruitment and activation of circulating inflammatory cells is well documented. 36-39 A strong argument can be made for the importance of neutrophils or neutrophil-derived mediators in regulating PAF catabolism and synthesis in the pancreas. A recent study demonstrated increased basal and cerulein-hyperstimulated pancreatic PAF levels in neutrophil-depleted rats compared to control rats. 7 The same study demonstrated a shift from necrosis to apoptosis in acinar cells in neutrophil-depleted rats subject to cerulein-induced AP.

Our study provides new information regarding the role of PAF in pancreatic inflammation. The localization of PAF receptors in the pancreas provides compelling evidence that the microvascular endothelium is a primary site of PAF action in inflammatory events. The presence of PAF receptors on the pancreatic endothelium is similar to PAF receptor localization in microvascular beds of numerous organs including heart, kidney, and lung. 14 The absence of PAF receptors on acinar, ductal, and islet β cells suggests that these pancreatic cell types may not be involved as primary targets in the initial response to excess PAF synthesis. The lack of PAF receptors on pancreatic acini implies that PAF is not involved directly in the regulation of PAF synthesis in acinar cells.

The experimental focus of modulating PAF signaling responses in pancreatitis has thus far emphasized utilization of PAF receptor antagonists to minimize various indices of pancreatic insult in AP. The level and regulation of PAF receptor expression during AP has not been studied in detail. Understanding the cellular regulatory mechanisms involved in expression of the PAF receptor may lead to insights crucial to the development of more efficacious therapeutic agents and/or interventions.

In conclusion, the results of the present study provide new and important information concerning our understanding of PAF signaling in acute pancreatitis. Our experiments allow us to predict that an initial injury to the pancreas causes acinar cells to generate and release excess PAF, causing activation of the surrounding microvascular endothelium and/or circulating inflammatory cells. Thereafter, inflammatory cells of various types are recruited to the pancreas, promoting more extensive tissue injury. Further investigation will be required to understand the importance of specific interactions between PAF, its receptor, and the pancreatic microvasculature during episodes of AP.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Merle S. Olson, University of Texas Health Science Center, Department of Biochemistry, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78284-7760. E-mail: olson@bioc02.uthscsa.edu.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK-33558. BDF was supported by National Institutes of Health postdoctoral fellowship DK-09540.

References

- 1.Hanahan DJ, Demopoulos CA, Liehr J, Pinckard RN: Identification of platelet activating factor isolated from rabbit basophils as acetyl glyceryl ether phosphorylcholine. J Biol Chem 1980, 255:5514-5516 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chao W, Olson MS: Platelet-activating factor: receptors and signal transduction. Biochem J 1993, 292:617-629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camussi G, Montrucchio G, Lupia E, De Martino A, Perona L, Arese M, Vercellone A, Toniolo A, Bussolino F: Platelet-activating factor directly stimulates in vitro migration of endothelial cells and promotes in vivo angiogenesis by a heparin-dependent mechanism. J Immunol 1995, 154:6492-6501 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frenkel RA, Muguruma K, Johnston JM: The biochemical role of platelet-activating factor in reproduction. Prog Lipid Res 1996, 35:155-168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayala A, Chaudry IH: Platelet activating factor and its role in trauma, shock, and sepsis. New Horiz 1996, 4:265-275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kingsnorth AN: Platelet-activating factor. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1996, 219:28-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandoval D, Gukovskaya A, Reavey P, Gukovsky S, Sisk A, Braquet P, Pandol SJ, Poucell-Hatton S: The role of neutrophils and platelet-activating factor in mediating experimental pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1996, 111:1081-1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou W, Levine BA, Olson MS: Platelet-activating factor: a mediator of pancreatic inflammation during cerulein hyperstimulation. Am J Pathol 1993, 142:1504-1512 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shukla SD: Platelet-activating factor receptor and signal transduction mechanisms. FASEB J 1992, 6:2296-2301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dabrowski A, Gabryelewicz A, Chyczewski L: The effect of platelet activating factor antagonist (BN 52021) on acute experimental pancreatitis with reference to multiorgan oxidative stress. Int J Pancreatol 1995, 17:173-180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galloway SW, Kingsnorth AN: Lung injury in the microembolic model of acute pancreatitis and amelioration by lexipafant (BB-882), a platelet-activating factor antagonist. Pancreas 1996, 13:140-146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kingsnorth AW, Galloway SW, Formela LJ: Randomized, double-blind phase II trial of Lexipafant, a platelet-activating factor antagonist, in human acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 1995, 82:1414-1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honda Z, Nakamura M, Miki I, Minami M, Watanabe T, Seyama Y, Okado H, Toh H, Ito K, Miyamoto T: Cloning by functional expression of platelet-activating factor receptor from guinea-pig lung. Nature 1991, 349:342-346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Predescu D, Ihida K, Predescu S, Palade GE: The vascular distribution of the platelet-activating factor receptor. Eur J Cell Biol 1996, 69:86-98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asano K, Taniguchi S, Nakao A, Watanabe T, Kurokawa K: Distribution of platelet activating factor receptor mRNA along the rat nephron segments. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996, 225:352-357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bito H, Honda Z, Nakamura M, Shimizu T: Cloning, expression, and tissue distribution of rat platelet-activating-factor-receptor cDNA. Eur J Biochem 1994, 221:211-218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suschek C, Fehsel K, Kroncke K-D, Sommer A, Kolb-Bachofen V: Primary cultures of rat islet capillary endothelial cells. Constitutive and cytokine-inducible macrophagelike nitric oxide synthases are expressed and activities regulated by glucose concentration. Am J Pathol 1994, 145:685-695 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hootman SR, Picado-Leonard TM, Burnham DB: Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor structure in acinar cells of mammalian exocrine glands. J Biol Chem 1985, 260:4186-4194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheikh SP, Roach E, Fuhlendorff J, Williams JA: Localization of Y1 receptors for NPY and PYY on vascular smooth muscle cells in rat pancreas. Am J Physiol 1991, 260:G250-G257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sirois MG, Jancar S, Braquet P, Plante GE, Sirois P: PAF increases vascular permeability in selected tissues: effect of BN52021 and L-656,240. Prostaglandins 1988, 36:631-644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tetta C, Mariano F, Buades J, Ronco C, Wratten ML, Camussi G: Relevance of platelet-activating factor in inflammation and sepsis: mechanisms and kinetics of removal in extracorporeal treatments. Am J Kidney Dis 1997, 30:S57-S65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsukioka K, Matsuzaki M, Nakamata M, Kayahara H, Nakagawa T: Increased plasma level of platelet-activating factor (PAF) and decreased serum PAF acetylhydrolase (PAFAH) activity in adults with bronchial asthma. J Invest Allerg Clin Immunol 1996, 6:22-29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emanuelli G, Montrucchio G, Gaia E, Corvettii G, Gubatta L: Experimental acute pancreatitis induced by platelet-activating factor in rabbits. Am J Pathol 1989, 134:315-326 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis LD: Lexipafant (BB-882), a potent PAF antagonist in acute pancreatitis. Adv Exp Med Biol 1996, 416:361-363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solig HD, Fest W: Synthesis of 1-o-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycer-3-phosphocholine (platelet-activating factor) in exocrine glands and its control by secretagogues. J Biol Chem 1986, 261:13916-13922 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou W, Shen F, Miller JE, Han Q, Olson MS: Evidence for altered cellular calcium in the pathogenetic mechanism of acute pancreatitis in rats. J Surg Res 1996, 60:147-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tonnesen MG: Neutrophil-endothelial cell interactions: mechanisms of neutrophil adherence to vascular endothelium. J Invest Dermatol 1989, 93:53S-58S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kubes P, Ibbotson G, Russell J, Wallace JL, Granger DN: Role of platelet-activating factor in ischemia/reperfusion-induced leukocyte adherence. Am J Physiol 1990, 259:G300-G305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Z, Wolf MB: Platelet activating factor-induced microvascular permeability increases in the cat hindlimb. Circ Shock 1993, 41:8-18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill GE, Whitten CW: The role of the vascular endothelium in inflammatory syndromes, atherogenesis, and the propagation of disease. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 1997, 11:316-321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brock TA, Gimbrone MA, Jr: Platelet activating factors alters calcium homeostasis in cultured vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol 1986, 250:H1086-H1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grigorian GY, Ryan US: Platelet-activating factor effects on bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Circ Res 1987, 61:389-395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bussolino F, Silvagno F, Garbarino G, Costamagna C, Sanavio F, Arese M, Soldi R, Aglietta M, Pescarmona G, Camussi G, Bosia A: Human endothelial cells are targets for platelet-activating factor (PAF). Activation of α and β protein kinase C isozymes in endothelial cells stimulated by PAF. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:2877-2886 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heller R, Bussolino F, Ghigo D, Garbarino G, Pescarmona G, Till U, Bosia A: Human endothelial cells are target for platelet activating factor. II. Platelet-activating factor induces platelet-activating factor synthesis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Immunol 1992, 149:3682-3688 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bussolino F, Camussi G, Baglioni C: Synthesis and release of platelet-activating factor by human vascular endothelial cells treated with tumor necrosis factor of interleukin 1a. J Biol Chem 1988, 263:11856-11861 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elstad MR, La Pine TR, Cowley FS, McEver RP, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA: P-selectin regulates platelet-activating factor synthesis and phagocytosis by monocytes. J Immunol 1995, 155:2109-2122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coughlan AF, Hau H, Dunlop LC, Berndt MC, Hancock WW: P-selectin and platelet-activating factor mediate initial endotoxin-induced neutropenia. J Exp Med 1994, 179:329-334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmerman BJ, Holt JW, Paulson JC, Anderson DC, Miyasaka M, Tamatani T, Todd RF, Rusche JR, Granger DN: Molecular determinants of lipid mediator-induced leukocyte adherence and emigration in rat mesenteric venules. Am J Physiol 1994, 266:H847-H853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder F: Platelet-activating factor and related acetylated lipids as potent biologically active cellular mediators. Am J Physiol 1990, 259:C697-C708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]