Abstract

The most common cause of new blindness in young patients is retinal neovascularization, and in the elderly is choroidal neovascularization. Therefore, there has been a great deal of attention focused on the development of new treatments for these disease processes. Previous studies have demonstrated partial inhibition of retinal neovascularization in animal models using antagonists of vascular endothelial growth factor or other signaling molecules implicated in the angiogenesis cascade. These studies have indicated potential for drug treatment, but have left many questions unanswered. Is it possible to completely inhibit retinal neovascularization using drug treatment with a mode of administration that is feasible to use in patients? Do agents that inhibit retinal neovascularization have any effect on choroidal neovascularization? In this study, we demonstrate complete inhibition of retinal neovascularization in mice with oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy by oral administration of a partially selective kinase inhibitor that blocks several members of the protein kinase C family, along with vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases. The drug also blocks normal vascularization of the retina during development but has no identifiable adverse effects on mature retinal vessels. In addition, the kinase inhibitor causes dramatic inhibition of choroidal neovascularization in a laser-induced murine model. These data provide proof of concept that pharmacological treatment is a viable approach for therapy of both retinal and choroidal neovascularization.

The retina receives its blood supply from two vascular beds: retinal vessels, which supply the inner two-thirds of the retina, and choroidal vessels, which supply the outer one-third. Damage to retinal blood vessels resulting in closure of retinal capillaries and retinal ischemia occurs in several disease processes, including diabetic retinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity, branch retinal vein occlusion, and central retinal vein occlusion; they are collectively referred to as ischemic retinopathies. Retinal ischemia results in release of one or more angiogenic factors that stimulate neovascularization. The new vessels break through the internal limiting membrane that lines the inner surface of the retina and grow along the outer surface of the vitreous. They recruit many other cells and produce sheets of vessels, cells, and extracellular matrix that exert traction on the retina, often leading to retinal detachment and severe loss of vision. Panretinal laser photocoagulation increases oxygenation in the retina and can result in involution of neovascularization. 1 However, despite the effectiveness of laser photocoagulation, 2 diabetic retinopathy remains the most common cause of severe vision loss in patients less than 60 years of age in developed countries, and therefore additional treatments are needed.

Choroidal neovascularization occurs in several diseases in which there are abnormalities of Bruch’s membrane. The most prevalent disease of this type is age-related macular degeneration, the most common cause of severe vision loss in patients over the age of 60 in developed countries. 3 Neovascularization originating from choroidal vessels grows through Bruch’s membrane into the sub-retinal pigmented epithelial space and sometimes into the subretinal space. The blood vessels leak fluid, which collects beneath the retina causing reversible visual loss, and they bleed and cause scarring that results in permanent loss of central vision. Current treatments are designed to destroy or remove the abnormal blood vessels and do not address the underlying stimuli responsible for neovascularization; therefore, recurrent neovascularization and permanent visual loss occur in the majority of patients who initially have successful treatment. 3 Drug treatment that blocks the stimuli for choroidal neovascularization would be a major advance, but its development is hindered by our poor understanding of pathogenesis.

More is known about the cascade of events leading to retinal neovascularization than that for choroidal neovascularization, because some of the molecular signals involved in the development of retinal neovascularization have been defined. For instance, several lines of evidence suggest that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays an important role in retinal vascularization during development and in pathological neovascularization in ischemic retinopathies. The expression of VEGF is increased by hypoxia, 4,5 which is a prominent feature of both of these processes. Stimulated by VEGF released by the avascular, hypoxic peripheral retina, blood vessels begin to develop at the optic nerve and extend to the periphery of the retina. 6 Likewise, VEGF participates in pathological retinal neovascularization, because its levels are increased in the retina and vitreous of patients 7-10 or laboratory animals 11,12 with ischemic retinopathies, and increased expression of VEGF in retinal photoreceptors of transgenic mice stimulates neovascularization within the retina. 13 The implication of VEGF in retinal neovascularization led to studies investigating VEGF antagonists in models of ischemic retinopathy. Soluble VEGF receptor/IgG fusion proteins or VEGF antisense oligonucleotides each inhibited retinal neovascularization by ∼50% in the murine model of oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy. 14,15 Antibodies to VEGF partially inhibited iris neovascularization in a monkey model of ischemic retinopathy. 16

Although VEGF plays a central role, it is not the only stimulator involved, which might explain why VEGF antagonists are only partially effective. Growth hormone acting through insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I also participates in retinal neovascularization, and decreased IGF-I in genetically engineered mice or antagonism of IGF-I by somatostatin analogs results in approximately a 30% decrease in retinal neovascularization in mice with ischemic retinopathy. 17

Intracellular signaling induced by VEGF is complex, but it has been suggested that protein kinase C (PKC), particularly the PKCβII isoform, plays a prominent role. 18,19 A specific antagonist of PKCβ isoforms partially inhibits retinal neovascularization after laser-induced branch vein occlusion. 20

Integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5 are induced on endothelial cells, including those in the retina, participating in neovascularization. 21,22 Two independent studies using different peptides that antagonize binding to αvβ3 or both αvβ3 and αvβ5 each demonstrated up to 50% inhibition of retinal neovascularization in the murine model of oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy. 22,23

Thus, several different types of agents that work by different mechanisms can cause partial inhibition of retinal neovascularization. This suggests that drug treatment of retinal neovascularization in patients may be feasible, but there are several questions related to this issue that remain. For instance, why is it that 50% inhibition has been the maximal achievable limit with several types of agents given by different routes of administration, including intraocular injections? Is there so much redundancy built into the retinal neovascularization cascade that this is the most that can be attained, and if so, is it sufficient to provide clinical benefit? Would an agent or combination of agents that act on multiple targets in the cascade be more effective? Do any of the molecular signals implicated in retinal neovascularization also play a role in choroidal neovascularization, and are there agents that inhibit both?

PKC consists of a family of at least 10 related serine/threonine kinases. 24 Staurosporine is an alkaloid produced by bacteria that is a potent nonspecific inhibitor of PKC 25 that also inhibits other serine/threonine kinases, such as protein kinase A (PKA), and tyrosine kinases, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). 26 CGP 41251 is a derivative of staurosporine with the chemical name N-benzoyl-staurosporine that was developed as a PKC inhibitor for treatment of cancer. 26 It is a less potent inhibitor of PKC than staurosporine but is more specific because it is a weak inhibitor of PKA and EGFR, and it has been used in several studies to assess the role of PKC in cellular functions. 27-30 Recently, one of the authors (J.M. Wood) determined that CGP 41251 is also a relatively potent inhibitor of VEGF and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor tyrosine kinases (unpublished data). It was also shown to inhibit VEGF-induced angiogenesis in a mouse subcutaneous growth factor implant model. As antagonism of VEGF and inhibition of PKC, each have been demonstrated to partially inhibit retinal neovascularization 14,15,20 and CGP 41251 has both activities, we investigated the effect of CGP 41251 in animal models of retinal and choroidal neovascularization.

Materials and Methods

Measurement of Inhibitory Activity of CGP 41251 in Vitro

The effect of CGP 41251 on the enzymatic activity of several members of the PKC family was measured using purified enzymes and artificial substrates as previously described. 29 The effect of CGP 41251 on phosphorylation of VEGFRs and other tyrosine kinase receptors was measured using purified recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fused kinase domains in the presence of substrate and labeled ATP. 31 The kinase domain-fusion proteins were expressed in baculovirus, purified over glutathione-Sepharose, and diluted in 10 mmol/L Tris/HCl (pH 7.2) based on their specific activity to obtain an activity of 4000 to 6000 cpm above background (<400 cpm). [33P]ATP (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) was used as the phosphate donor, and the polyGluTyr(4:1) peptide (P-275, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was used as the acceptor. CGP 41251 was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 10 mmol/L and then diluted as required so that the final DMSO concentration was 1%. The assay mixture, which was optimized for each kinase (20 mmol/L Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 1 to 10 mmol/L MnCl2, 1 to 10 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 to 8 μmol/L ATP, 0.2 μCi of [33P]ATP, 3 to 8 μg/ml polyGluTyr(4:1)) was incubated with the respective GST-fused kinase with or without CGP 41251 for 10 minutes at room temperature in a total volume of 30 μl. The reaction was stopped by adding 10 μl of 250 mmol/L EDTA. Using a 96-well filter system (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), 20 μl of the reaction mixture was transferred onto an Immobilon-PVDF membrane (IPVH 000 10, Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were washed extensively with 0.5% H3PO4 and soaked in ethanol. After drying, Microscint cocktail (TM-0 6013611, Packard, Meriden, CT) was added, and scintillation counting was performed (Hewlett Packard Top Count). IC50 values were calculated by linear regression analysis of the percentage inhibition by CGP 41251 over a range of different concentrations

Drug Treatment of Mice with Ischemic Retinopathy

Ischemic retinopathy was produced in C57BL/6J mice by a method described by Smith et al. 32 Seven-day-old (P7) mice and their mothers were placed in an airtight incubator and exposed to an atmosphere of 75 ± 3% oxygen for 5 days. Incubator temperature was maintained at 23 ± 2°C, and oxygen was measured every 8 hours with an oxygen analyzer. After 5 days, the mice were removed from the incubator and placed in room air, and drug treatment was begun. Drug was dissolved in DMSO and diluted to final concentrations with water; the maximal concentration of DMSO was 1%. Vehicle (1% DMSO) or vehicle containing various concentrations of drug (volume = 10 μl per gram body weight) was placed in the stomach by gavage once a day. At P17, after 5 days of treatment, mice were sacrificed, and eyes were rapidly removed and frozen in optimal cutting temperature embedding compound (OCT; Miles Diagnostics, Elkhart, IN) or fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Adult C57BL/6J mice were also treated by gavage with drug or vehicle, and after 5 days, they were sacrificed and their eyes were processed for frozen or paraffin sections.

Quantitation of Retinal Neovascularization

Frozen sections (10 μm) of eyes from drug-treated and control mice were histochemically stained with biotinylated griffonia simplicifolia lectin B4 (GSA, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), which selectively binds to endothelial cells. Slides were incubated in methanol/H2O2 for 10 minutes at 4°C, washed with 0.05 mol/L Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.6 (TBS), and incubated for 30 minutes in 10% normal porcine serum. Slides were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with biotinylated GSA, and after rinsing with 0.05 mol/L TBS, they were incubated with avidin coupled to peroxidase (Vector Laboratories) for 45 minutes at room temperature. After being washed for 10 minutes with 0.05 mol/L TBS, slides were incubated with diaminobenzidine to give a brown reaction product. Some slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, and all were mounted with Cytoseal.

To perform quantitative assessments, 10-μm serial sections were cut through one-half of each eye, and sections roughly 50 to 60 μm apart were stained with GSA, providing 13 sections per eye for analysis. GSA-stained sections were examined with an Axioskop microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), and images were digitized using a 3 CCD color video camera (IK-TU40A, Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) and a frame grabber. Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Springs, MD) was used to delineate GSA-stained cells on the surface of the retina, and their area was measured. The mean of the 13 measurements from each eye was used as a single experimental value.

Drug Treatment of Mice during Retinal Vascular Development

Litters of newborn C57BL/6J mice were divided into treatment and control groups that received daily subcutaneous injections of 100 mg/kg drug or vehicle, respectively. At P7 or P10, mice were anesthetized and perfused with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline containing 50 mg/ml fluorescein-labeled dextran (2 × 10 6 average molecular weight; Sigma) as previously described. 33 The eyes were removed and fixed for 1 hour in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin. The cornea and lens were removed and the entire retina was carefully dissected from the eyecup. Radial cuts were made from the edge of the retina to the equator in all four quadrants, and the retina was flat mounted in Aquamount with photoreceptors facing upward. Flat mounts were examined by fluorescence microscopy, and images were digitized using a 3 CCD color video camera and a frame grabber. Image-Pro Plus was used to measure the distance from the center of the optic nerve to the leading front of developing retinal vessels in each quadrant, and the mean was used as a single experimental value.

Drug Treatment of Mice with Laser-Induced Choroidal Neovascularization

Choroidal neovascularization was generated by modification of a previously described technique. 34 Briefly, 4- to 5-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg body weight), and the pupils were dilated with 1% tropicamide. Three burns of krypton laser photocoagulation (100-μm spot size, 0.1-second duration, 150 mW) were delivered to each retina using the slit lamp delivery system of a Coherent model 920 photocoagulator and a hand-held cover slide as a contact lens. Burns were performed in the 9, 12, and 3 o’clock positions of the posterior pole of the retina. Production of a bubble at the time of laser, which indicates rupture of Bruch’s membrane, is an important factor in obtaining choroidal neovascularization, 34 so only mice in which a bubble was produced for all three burns were included in the study. Ten mice were randomly assigned to treatment with vehicle alone, and 10 mice received vehicle containing 400 mg/kg/day of CGP 41251 orally by gavage. After 14 days, the mice were killed with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium, and their eyes were rapidly removed and frozen in OCT.

Quantitative Analysis of the Amount of Choroidal Neovascularization

Frozen serial sections (10 μm) were cut through the entire extent of each burn and histochemically stained with biotinylated GSA as described above. Histomark Red (Kirkegaard and Perry, Gaithersburg, MD) was used as chromogen to give a red reaction product that is distinguishable from melanin. Some slides were counterstained with Contrast Blue (Kirkegaard and Perry).

To perform quantitative assessments, GSA-stained sections were examined with an Axioskop microscope, and images were digitized using a 3 CCD color video camera and a frame grabber. Image-Pro Plus software was used to delineate and measure the area of GSA-stained blood vessels in the subretinal space. For each lesion, area measurements were made for all sections on which some of the lesion appeared and added together to give the integrated area measurement. Only lesions in which good sections were obtained through the entire lesion, so that a valid area measurement could be made on each, were included in the analysis. There appeared to be little variability among lesions in individual mice, and all excluded lesions were qualitatively similar in size to included lesions and were excluded solely due to inability to obtain an accurate measurement because of poor quality of some sections. Values were averaged to give one experimental value per mouse. A two-sample t-test for unequal variances was performed to compare the log mean integrated area between treated and control mice.

Results

Characterization of in Vitro Activity of CGP 41251

Table 1 ▶ shows the kinase inhibitory profile of CGP 41251. The IC50 for several subtypes of PKC as well as the KDR tyrosine kinase of human VEGF receptor-2 and the tyrosine kinase of human PDGF receptor-β are in the same range (20 to 100 nmol/L). At approximately 10-fold higher concentrations, CGP 41251 inhibits Flk-1, the tyrosine kinase of the mouse VEGF receptor corresponding to human KDR, and Flt-1, the tyrosine kinase of human VEGF receptor-1. The IC50s for other receptor tyrosine kinases, such as Tie 2, fibroblast growth factor receptor-1, or epidermal growth factor receptor, are 3 μmol/L or above.

Table 1.

Kinase Inhibition Profile of CGP 41251

| Kinase | IC50 (μmol/L) |

|---|---|

| PKCα | 0.022 ± 0.008 |

| PKCβI | 0.030 ± 0.018 |

| PKCβII | 0.031 ± 0.016 |

| PKCγ | 0.024 ± 0.006 |

| PKCδ | 0.33 ± 0.071 |

| PKCζ | 465 ± 49 |

| PKCɛ | 1.25 ± 1.06 |

| PKCη | 0.16 ± 0.095 |

| KDR | 0.086 ± 0.04 |

| Flt-1 | 0.912 ± 0.244 |

| Flk-1 | 1.013 ± 0.261 |

| PDGFR-β | 0.02 |

| Tie2 | >10.00 |

| FGFR1 | >10.00 |

| EGFR | 3.025 |

| PKA | 2.425 |

Each value represents the mean ± SEM calculated from at least three experimental values from at least two independent experiments.

CGP 41251 Inhibits Retinal Neovascularization in Mice with Ischemic Retinopathy

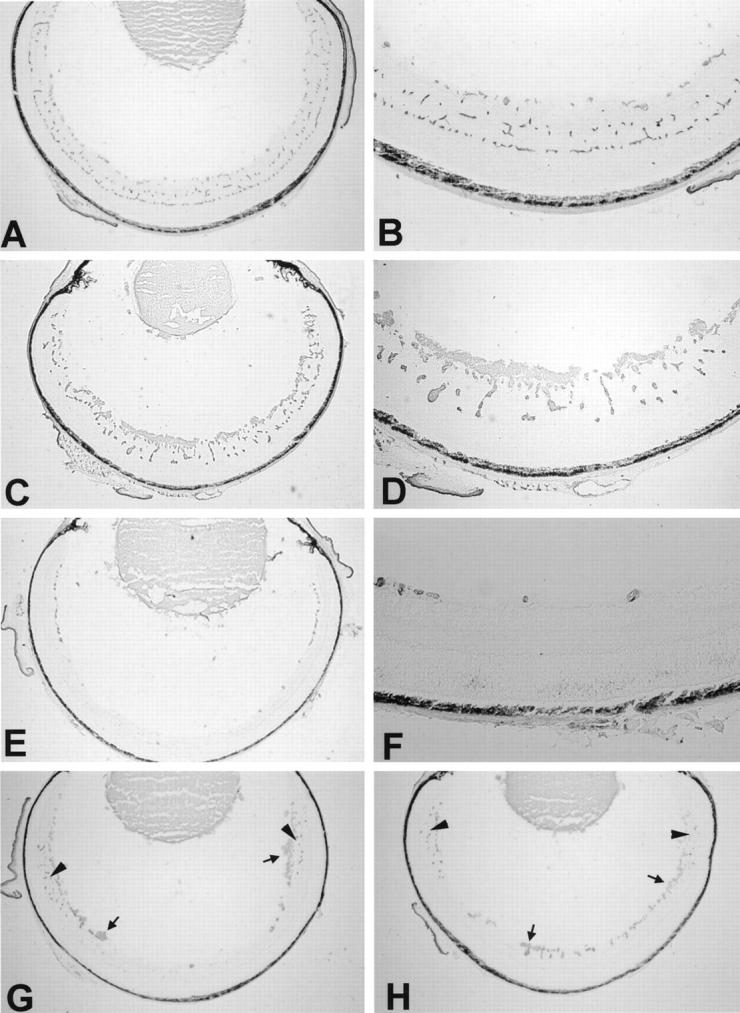

Retinas of nonischemic P17 mice stained with GSA show normal vessels in the superficial and deep capillary beds with a few connecting vessels (Figure 1, A and B) ▶ . P17 mice with ischemic retinopathy treated with vehicle show a marked increase in the area of endothelial cell staining throughout the retina with large clumps of cells on the retinal surface (Figure 1, C and D) ▶ , not seen in nonischemic retinas. P17 mice with ischemic retinopathy given 600 mg/kg CGP 41251 once a day for 5 days by gavage have a dramatic decrease in endothelial cell staining on the surface and within the retina (Figure 1, E and F) ▶ compared with vehicle-treated mice. In fact, the endothelial cell staining within the retina is less than that seen in nonischemic P17 mice. High magnification shows that there are no identifiable endothelial cells on the surface of the retina, indicating that there is complete inhibition of neovascularization (Figure 1F) ▶ . There is also a striking absence of endothelial cell staining in the inner nuclear layer and outer plexiform layer where the deep capillary beds are normally located. P17 mice with ischemic retinopathy given 300 mg/kg (Figure 1G) ▶ or 60 mg/kg (Figure 1H) ▶ CGP 41251 once a day by gavage show some clumps of neovascularization on the surface of the retina (arrows) that are less than those seen in vehicle-treated controls. They also show some decrease in endothelial staining within the retina, but there is some present (arrowheads). Image analysis demonstrates that mice treated once a day with 600, 60, or 6 mg/kg CGP 41251 show a statistically significant dose-dependent decrease in endothelial cell staining on and in the retinas compared with vehicle-treated mice (P < 0.001 by analysis of variance (ANOVA); Figure 2 ▶ ).

Figure 1.

Treatment with CGP 41251 blocks retinal neovascularization in a dose-dependent manner in mice with ischemic retinopathy. P7 mice were put in high oxygen for 5 days and then removed to room air and given CGP 41251 or vehicle by gavage for 5 days. Retinal frozen sections were histochemically stained with the endothelial cell-selective lectin griffonia simplicifolia I using the peroxidase-antiperoxidase technique. Retinal blood vessels within the retina and neovascularization on the surface are stained with reaction product. A: Normal retinal vessels in a nonischemic P17 mouse. B: High magnification of normal retinal vessels in P17 mouse. C: A P17 mouse with ischemic retinopathy treated by gavage for 5 days with vehicle alone shows extensive neovascularization on the surface of the retina. D: High magnification of retina from C showing prominent neovascularization. E: A P17 mouse with ischemic retinopathy treated by gavage with 600 mg/kg CGP 41251 once a day for 5 days shows essentially complete absence of endothelial cells in the posterior retina, and there are only a few clumps of endothelial cells in the superficial part of the anterior retina with striking absence of the deep retinal capillary bed. F: High magnification of the anterior retina from E shows only a few clumps of endothelial cells in the superficial part of the retina with no neovascularization on the surface and no deep capillaries. G: A P17 mouse with ischemic retinopathy treated by gavage with 300 mg/kg CGP 41251 once a day for 5 days shows essentially complete absence of endothelial cells in the posterior retina, but in midperipheral and peripheral retina, there are retinal vessels and a few patches of neovascularization (arrows). The deep capillary bed is present in the periphery of the retina (arrowheads). H: A P17 mouse with ischemic retinopathy treated by gavage with 60 mg/kg CGP 14251 once a day for 5 days shows retinal vessels throughout the anterior and posterior retina, but the deep capillary bed is more evident in the periphery (arrowheads). Small patches of neovascularization are also seen on the surface of the posterior and anterior retina (arrows).

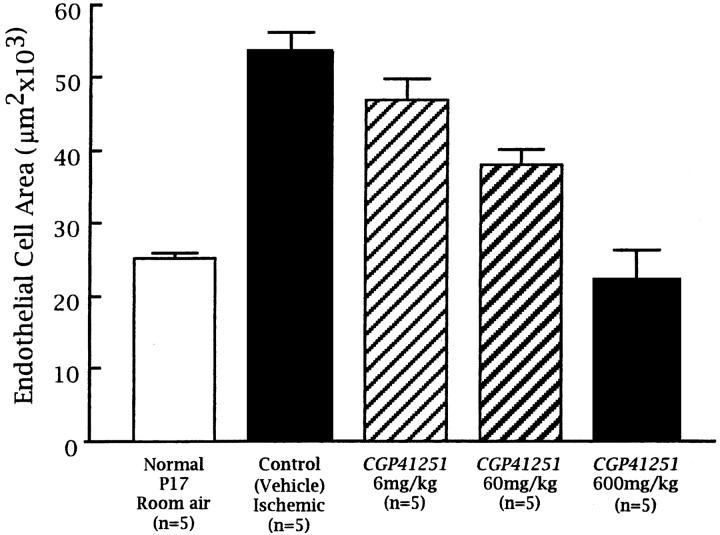

Figure 2.

Quantitation of the area of endothelial cell staining in retinal sections of mice with ischemic retinopathy treated for 5 days by gavage with vehicle or vehicle containing various concentrations of CGP 41251. Total area of endothelial cell staining in retinal sections was determined by image analysis as described in Materials and Methods. There was a statistically significant difference between the control group and the three treated groups (P < 0.001 by ANOVA).

CGP 41251 Inhibits Retinal Vascular Development

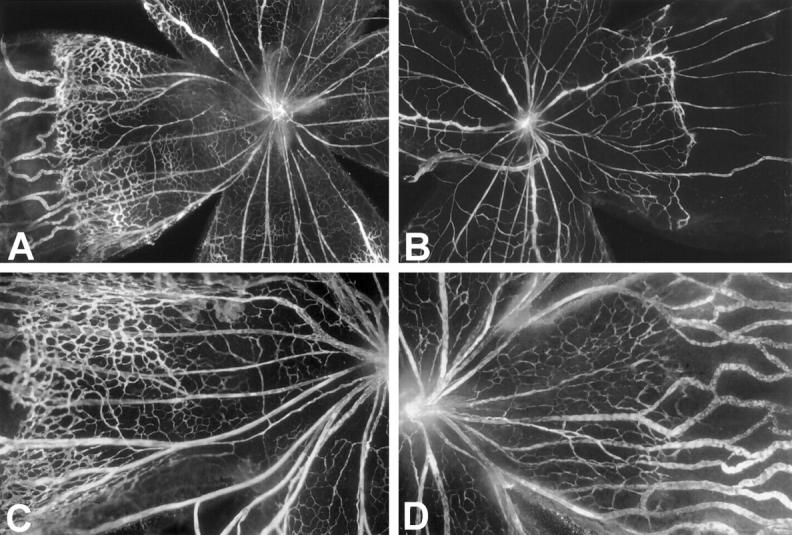

The decrease in endothelial staining in the inner nuclear layer of the retinas of CGP-41251-treated mice suggests that there might be some inhibition of retinal vascular development, because the time of treatment (P12 to P17) corresponds to the period of development of the deep capillary bed. 35 To test this, neonatal mice were treated with subcutaneous injections of 100 mg/kg CGP 41251 or vehicle alone starting on P0, and on P7 or P10 they were perfused with fluorescein-labeled dextran and retinal whole mounts were prepared. At P7, retinal vessels in vehicle-treated mice have almost reached the peripheral edge of retina (Figure 3, A and C) ▶ , but in CGP-41251-treated mice, the retinal vessels have extended only slightly more than halfway to the periphery (Figure 3, B and D) ▶ . At P10, in vehicle-treated mice, the superficial capillary bed is complete and extends all of the way to the peripheral edge of the retina, and the deep capillary bed is partially developed. But in CGP-41251-treated mice, the superficial capillary bed has not yet reached the edge of the retina (not shown). The distance from the optic nerve to the vascular front was calculated by image analysis, and the differences between treated and control mice at P7 and P10 were statistically significant (Figure 4) ▶ . This indicates that CGP 41251 inhibits normal retinal vascular development as well as pathological retinal neovascularization.

Figure 3.

Treatment with CGP 41251 inhibits development of retinal blood vessels. Mice were given daily subcutaneous injections of vehicle (A and C) or vehicle containing 100 mg/kg CGP 41251 (B and D) starting on postnatal day 1 (P1) and were sacrificed on P7 by perfusion with fluorescein-labeled dextran. Fluorescence microscopy shows a leading front of developing retinal vessels extending further from the optic nerve in vehicle-treated retinas compared with retinas treated with CGP 41251. The large vessels are primary hyaloidal vessels that have not yet involuted. C: High magnification of control retina showing extensive development of retinal capillaries. D: High magnification of retina from CGP-41251-treated mouse showing marked inhibition of retinal capillary development.

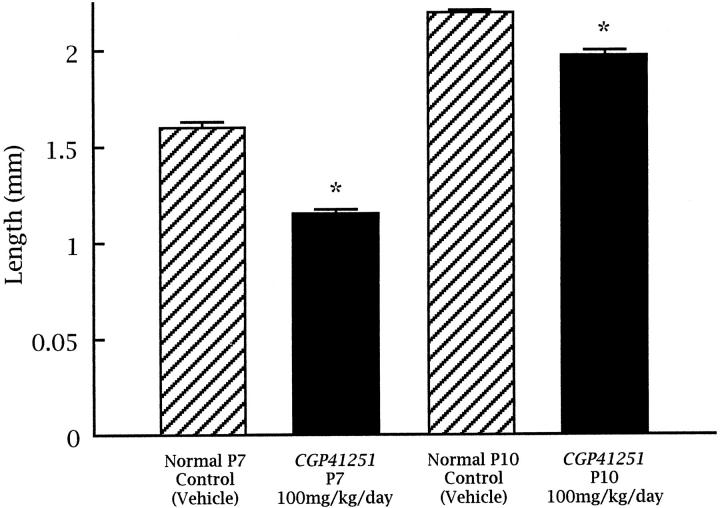

Figure 4.

Quantitation of retinal vascular development in neonatal control and CGP 41251-treated mice. Retinal whole mounts were examined by fluorescence microscopy, and the distance from the optic nerve to the leading front of developing retinal capillaries was measured in all four quadrants to give an average value for each retina. For each group, n = 5. P < 0.001 for a dose-dependent decrease in CGP-41251-treated mice compared with age-matched controls by ANOVA.

CGP 41251 Has No Identifiable Effect on Retinal Vessels in Adult Mice

Adult mice were given 600 mg/kg CGP 41251 by gavage once a day for 5 days, the highest dose used in the model of oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy. There was no difference in the total area of endothelial staining in the retina or the appearance of retinal vessels in CGP-41251-treated mice compared with vehicle-treated mice (Figure 5, A and B) ▶ . Image analysis shows no difference in the amount of retinal endothelial cell staining between CGP-41251- and vehicle-treated mice. This suggests that CGP 41251 is not toxic to endothelial cells of mature vessels.

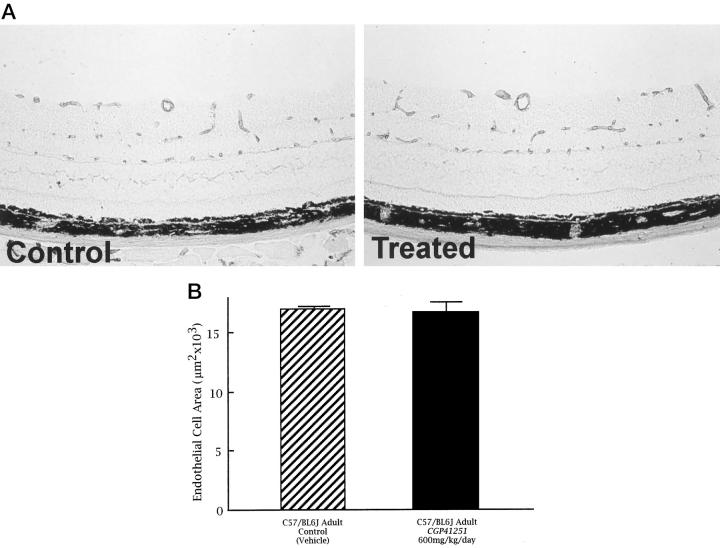

Figure 5.

Treatment with CGP 41251 shows no identifiable toxicity to mature retinal blood vessels. A: Adult mice were treated by gavage for 5 days with vehicle or vehicle containing 600 mg/kg CGP 41251. Retinal frozen sections were histochemically stained with the endothelial-cell-selective lectin griffonia simplicifolia I using the peroxidase-antiperoxidase technique. There is no difference in the number or appearance of retinal blood vessels in treated versus control retinas. B: Quantitation of the total area of endothelial cell staining by image analysis shows no difference between control (n = 5) and CGP-41251-treated (n = 5) retinas (P = 0.8489 by paired t-test).

CGP 41251 Inhibits Choroidal Neovascularization in Mice with Laser-Induced Rupture of Bruch’s Membrane

Two weeks after laser photocoagulation, all lesions in both groups of mice showed a discontinuity in Bruch’s membrane with roughly equivalent damage to the overlying retina. All mice treated with vehicle alone showed large areas of choroidal neovascularization at the site of each laser-induced rupture of Bruch’s membrane (Figure 6, A and C) ▶ . There was proliferation of retinal pigmented epithelial cells along the margin of the new vessels. Retinal blood vessels stained with GSA were seen in the overlying retina. In contrast, all mice given 400 mg/kg/day CGP 41251 by gavage had very little if any choroidal neovascularization at the site of each laser-induced rupture of Bruch’s membrane. In many instances, there was no identifiable GSA-stained neovascular tissue throughout the entire burn (Figure 6D) ▶ , but some burns contained regions in which there were thin disks of GSA-stained tissue (Figure 6B) ▶ . There was mild proliferation of retinal pigmented epithelial cells. Despite the marked decrease in choroidal neovascularization in the eyes of treated mice, the overlying retinal vessels appeared normal. This was best seen in sections with no counterstain (Figure 6B) ▶ .

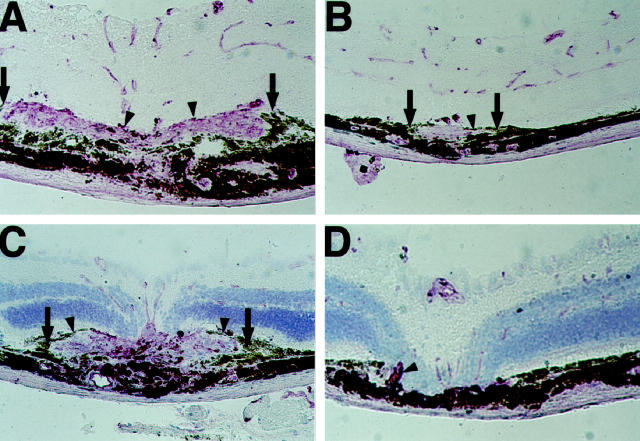

Figure 6.

Oral administration of CGP 41251 inhibits the development of choroidal neovascularization. Mice given vehicle alone by gavage have extensive choroidal neovascularization 14 days after laser-induced rupture of Bruch’s membrane. A: Histochemistry with griffonia simplicifolia lectin (GSA) and no counterstain shows a large area of staining in the subretinal space due to choroidal neovascularization and small focal areas of staining in the retina due to retinal blood vessels. C: A laser burn in another control mouse stained with GSA and counterstained with contrast blue shows prominent choroidal neovascularization. Mice given 400 mg/kg CGP 41251 have minimal choroidal neovascularization 14 days after laser-induced rupture of Bruch’s membrane. B: GSA staining without counterstaining shows minimal choroidal neovascularization, and the overlying retinal vessels are normal in appearance. D: A laser burn in another CGP-41251-treated mouse shows essentially no choroidal neovascularization and normal retinal blood vessels in the overlying retina, which is counterstained with contrast blue.

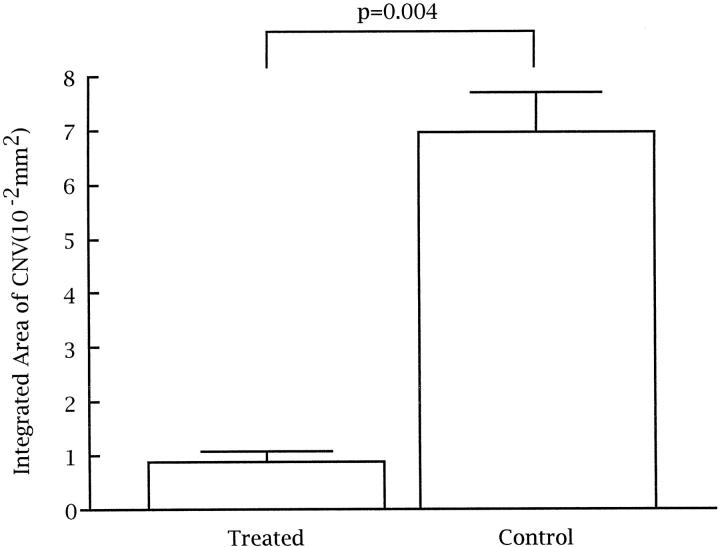

Quantitation of the integrated area of GSA staining per lesion showed a dramatic decrease in mice treated with CGP 41251 compared with lesions in mice treated with vehicle alone. Table 2 ▶ shows the measurements for each of the lesions in which intact, adequately stained sections were obtained all of the way through the lesion, allowing measurement of the area of neovascularization on each section. In all but four mice, high quality, well stained inclusive sections were obtained for at least four of six lesions (two mice in the treated group and one in the control group had three measurable lesions, and one control mouse had two measurable lesions). Qualitatively, all of the lesions in an individual were very similar in size, with no systematic differences between included and excluded lesions except for the inability to obtain accurate quantitative assessment for excluded lesions. The mean of the measurements made in each individual mouse constituted a single experimental value. The mean integrated area of choroidal neovascularization in 10 CGP 41251 mice was 0.0090182 ± 0.0017540 mm 2 compared with 0.0695621 ± 0.0073960 mm 2 in 10 control mice, nearly an eightfold difference. This difference was highly statistically significant (P = 0.004; Figure 7 ▶ ).

Table 2.

Integrated Area of Choroidal Neovascularization at Sites of Laser-Induced Rupture of Bruch’s Membrane in CGP-41251-Treated and Control Mice

| Integrated area of measurable lesions | Average (mm2 × 102) | |

|---|---|---|

| Treated mice | ||

| 1 | 1.34171, 2.01748, 1.97958 | 1.77959 |

| 2 | 1.28591, 0.57824, 1.13829, 0.81061, 1.19101 | 1.00081 |

| 3 | 1.50637, 0.79469, 0.50504, 0.46116 | 0.81681 |

| 4 | 1.54149, 1.09383, 0.92532, 1.71000 | 1.31766 |

| 5 | 0.11757, 0.05995, 0.04629, 0.05880 | 0.07065 |

| 6 | 0.73828, 1.21054, 1.00888, 0.81879, 1.15301 | 0.98590 |

| 7 | 0.87055, 0.90481, 2.91152, 1.12572, 1.99885 | 1.56229 |

| 8 | 1.59527, 0.29388, 1.46979, 0.08462, 0.38570 | 0.76585 |

| 9 | 0.07497, 1.04742, 0.84053, 0.20836 | 0.54282 |

| 10 | 0.24489, 0.10767, 0.17489 | 0.17581 |

| Mean | 0.90182 | |

| Control mice | ||

| 1 | 2.13169, 17.43091, 12.11940, 9.81230 | 10.37357 |

| 2 | 4.48336, 7.91262, 6.34613, 6.15369 | 6.22395 |

| 3 | 5.83853, 6.23603 | 6.03728 |

| 4 | 12.03223, 7.15583, 12.29029, 5.91466, 9.73981 | 9.42656 |

| 5 | 5.61468, 4.35111, 5.15342, 7.23744, 3.46248 | 5.16383 |

| 6 | 2.49107, 4.39638, 12.67973 | 6.52239 |

| 7 | 19.92445, 7.28564, 3.70144, 4.20451, 11.51673, 6.16789 | 8.80011 |

| 8 | 9.67250, 8.48616, 7.39480, 17.01920, 5.59292, 6.82986 | 9.16591 |

| 9 | 4.57032, 2.30611, 4.93298 | 3.93647 |

| 10 | 3.42368, 3.69508, 3.32311, 4.30905, 4.80916 | 3.91202 |

| Mean | 6.95621 |

Figure 7.

Quantitation of choroidal neovascularization in control and CGP-41251-treated mice with laser-induced rupture of Bruch’s membrane shows a significantly smaller integrated area of choroidal neovascularization in CGP-41251-treated mice (P = 0.004 by two-sample t-test for unequal variances).

Discussion

Retinal neovascularization is a major cause of visual morbidity and blindness and often affects young people in their most productive years. 36 Although panretinal photocoagulation is clearly beneficial, there are many patients in whom it cannot be delivered or is not sufficient. Also, panretinal photocoagulation has side effects, including production or exacerbation of macular edema, decreased night vision, and decreased visual fields. For these reasons, a great deal of effort has been directed toward development of drug treatment for retinal neovascularization.

Previous studies have demonstrated that several pharmacological agents with different mechanisms of action are capable of partially inhibiting retinal neovascularization. Antagonism of VEGF by soluble VEGF receptors coupled to IgG heavy chains 14 or by antisense oligonucleotides 15 or blockade of integrin αvβ3 by two different cyclic peptides 22,23 each inhibit retinal neovascularization in the murine model of oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy by as much as 50%. In this study, using the same model, we have demonstrated for the first time that it is possible to achieve essentially complete inhibition of retinal neovascularization by drug treatment. This provides strong support for the feasibility of using drugs to treat retinal neovascularization in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy or other blinding ischemic retinopathies. It is particularly encouraging that this dramatic treatment effect was achieved with oral administration, the preferred route of administration in patients.

The drug used in this study, CGP 41251, is an inhibitor of several PKC isoforms, including PKCβII, which has been implicated in diabetic complications, including neovascularization in the retina. 19,20 CGP 41251 is also an inhibitor of phosphorylation by VEGF and PDGF receptors. As previous studies with agents that specifically block PKCβ isoforms or specifically antagonize VEGF have resulted in only partial inhibition of retinal neovascularization, it may be that the greater efficacy of CGP 41251 is due to an additive effect of these different activities. However, it is also possible that the inhibitory effect on retinal neovascularization occurs predominantly through one of these activities and the greater efficacy of CGP 41251 compared with the more specific agents is due to a difference in pharmacokinetics or a difference in mechanism of action. For instance, it could be that blockade of VEGF receptor phosphorylation is a more effective way to block VEGF signaling than attempting to limit the amount of VEGF available to bind to the receptor. 14,15 In any case, this study demonstrates that it is possible to achieve much better inhibition of retinal neovascularization by pharmacological means than was previously demonstrated, and additional work is needed to determine the mechanism through which this occurs so that additional effective drugs can be designed. Identification and testing of drugs with different kinase inhibitory activities may help to accomplish this goal.

Our data also indicate that CGP 41251 inhibits normal retinal vascular development in addition to pathological retinal neovascularization. Although we were surprised by this finding initially, because it was not reported to occur from treatment with other VEGF antagonists in the same model, 14,15 its occurrence is understandable, because VEGF has been demonstrated to be a critical stimulator of normal retinal vascular development. 6 Down-regulation of VEGF during development by hyperoxia arrests vascular development and causes vaso-occlusion. 37 When hyperoxia-induced blockade is followed by pharmacological blockade of VEGF signaling (as well as PDGF and PKC signaling), it is not surprising that parts of the retina never develop retinal vessels.

More is known regarding the molecular signals involved in retinal neovascularization than those involved in choroidal neovascularization. This and lack of an inexpensive animal model in which it is possible to precisely measure the amount of choroidal neovascularization have hindered identification of agents that inhibit choroidal neovascularization. We have recently adapted to mice 34 a model of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization that was first developed in primates. 38 In this study, we report a technique of quantitatively assessing the amount of choroidal neovascularization, providing a means to objectively assess drug effects. Using this approach, we showed that oral administration of 400 mg/kg CGP 41251 dramatically inhibits choroidal neovascularization. This suggests that activation of PKC and/or VEGF signaling and/or PDGF signaling are involved in development of choroidal neovascularization in this model. By using drugs with different, but overlapping in vitro activities, it should be possible to further define the molecular signals involved in choroidal neovascularization.

The results of this study are encouraging in two other respects. CGP 41251 is the first drug identified to have a strong inhibitory effect on both retinal and choroidal neovascularization. Perhaps inhibitory activity in models of retinal neovascularization will have some predictive value for treatment of choroidal neovascularization. Additional correlative studies are needed to determine whether this is actually the case, but if so, it will simplify screening of drugs for ocular neovascularization. Second, although CGP 41251 is the first kinase inhibitor to be evaluated for its effect on retinal and choroidal neovascularization, and other agents in this class of drugs need to be evaluated and could possibly be more potent, the effects with CGP 41251 are dramatic and suggest that it may be useful for treatment of patients with retinal or choroidal neovascularization. The inhibitory effect of CGP 41521 on normal retinal vascular development may preclude its use in infants with retinopathy of prematurity, but the results of our study predict that CGP 41251 is a good candidate for treatment of adults with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and other ischemic retinopathies or choroidal neovascularization due to macular degeneration, ocular histoplasmosis, or a host of other diseases. Toxicity studies in animals have not identified any adverse systemic effects of orally administered CGP 41251 (unpublished data), and phase I clinical trials are underway in cancer patients. This study suggests that clinical trials in patients with retinal or choroidal neovascularization should also be considered.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yolanda Barrons, M.S., of the Wilmer Institute Biostatistics Core Laboratory for her assistance with statistical analysis supported by NIH core grant EYO1765.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Peter A. Campochiaro, Maumenee 719, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 600 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21287-9277. E-mail: pcampo@jhmi.edu.

Supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants EY05951 and EY2609 and core grant P30EY1765 from the National Eye Institute, a Lew R. Wasserman Merit Award (P.A. Campochiaro) and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., a Juvenile Diabetes Foundation fellowship grant (N. Okamoto), a grant from CIBA Vision, Inc., a Novartis Company, the Rebecca P. Moon, Charles M. Moon, Jr., and Dr. P. Thomas Manchester Research Fund, a grant from Mrs. Harry J. Duffey, a grant from Dr. and Mrs. William Lake, a grant from Project Insight, and a grant from the Association for Retinopathy of Prematurity and Related Diseases. P.A. Campochiaro is the George S. and Dolores D. Eccles Professor of Ophthalmology and Neuroscience.

CIBA Vision provided partial funding of the study reported in this article. P.A. Campochiaro is a consultant to CIBA Vision. The terms of this arrangement are being managed by The Johns Hopkins University in accordance with the conflict of interest policies.

M.S. Seo and N. Kwak contributed equally to the manuscript.

M.S. Seo’s current address: Chonnam National University Medical School and Hospital, Kwangju, Korea.

N. Kwak’s current address: Department of Ophthalmology, the Catholic University of Korea School of Medicine.

H. Ozaki’s current address: Fukuoka University School of Medicine, Fukuoka, Japan.

References

- 1.Pournaras CJ, Tsacopoulos M, Strommer K, Gilodi N, Leuenberger PM: Scatter photocoagulation restores tissue hypoxia in experimental vasoproliferative microangiopathy in miniature pigs. Ophthalmology 1990, 97:1329-1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.: The Diabetic Retinopathy Research Study Group: Photocoagulation treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy: clinical application of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DRS) findings, DRS Report Number 8. Ophthalmology 1981, 88:583-600 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.: Macular Photocoagulation Study Group: Argon laser photocoagulation for neovascular maculopathy: five year results from randomized clinical trials. Arch Ophthalmol 1991, 109:1109-1114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forsythe JA, Jiang B-H, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, Semenza G: Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol 1996, 16:4604-4613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy AP, Levy NS, Wegner S, Goldberg MA: Transcriptional regulation of the rat vascular endothelial growth factor gene by hypoxia. J Biol Chem 1995, 270:13333-13340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone J, Itin A, Alon T, Pe’er J, Gnessin H, Chan-Ling T, Keshet E: Development of retinal vasculature is mediated by hypoxia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression by neuroglia. J Neurosci 1995, 15:4738-4747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamis AP, Miller JW, Bernal M-T, D’Amico DJ, Folkman J, Yeo T-K, Yeo K-T: Increased vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the vitreous of eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1994, 118:445-450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiello LP, Avery RL, Arrigg PG, Keyt BA, Jampel HD, Shah ST, Pasquale LR, Thieme H, Iwamoto MA, Park JE, Nguyen MS, Aiello LM, Ferrara N, King GL: Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N Engl J Med 1994, 331:1480-1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malecaze F, Clamens S, Simorre-Pinatel V, Mathis A, Chollet P, Favard C, Bayard F, Plouet J: Detection of vascular endothelial growth factor messenger RNA and vascular endothelial growth factor-like activity in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1994, 112:1476-1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pe’er J, Shweiki D, Itin A, Hemo I, Gnessin H, Keshet E: Hypoxia-induced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor by retinal cells is a common factor in neovascularizing ocular diseases. Lab Invest 1995, 72:638-645 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller JW, Adamis AP, Shima DT, D’Amore PA, Moulton RS, O’Reilly MS, Folkman J, Dvorak HF, Brown LF, Berse B, Yeo T-K, Yeo K-T: Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor is temporally and spatially correlated with ocular angiogenesis in a primate model. Am J Pathol 1994, 145:574-584 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierce EA, Avery RL, Foley ED, Aiello LP, Smith LEH: Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor expression in a mouse model of retinal neovascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:905-909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okamoto N, Tobe T, Hackett SF, Ozaki H, Vinores MA, LaRochelle W, Zack DJ, Campochiaro PA: Transgenic mice with increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in the retina: a new model of intraretinal and subretinal neovascularization. Am J Pathol 1997, 151:281-291 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aiello LP, Pierce EA, Foley ED, Takagi H, Chen H, Riddle L, Ferrara N, King GL, Smith LEH: Suppression of retinal neovascularization in vivo by inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) using soluble VEGF-receptor chimeric proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:10457-10461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson GS, Pierce EA, Rook SL, Foley E, Webb R, Smith LES: Oligodeoxynucleotides inhibit retinal neovascularization in a murine model of proliferative retinopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:4851-4856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adamis AP, Shima DT, Tolentino MJ, Gragoudas ES, Ferrara N, Folkman J, D’Amore PA, Miller JW: Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor prevents retinal ischemia-associated iris neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol 1996, 114:66-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith LEH, Kopchick JJ, Chen W, Knapp J, Kinose F, Daley D, Foley E, Smith RG, Schaeffer JM: Essential role of growth hormone in ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization. Science 1997, 276:1706-1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoguchi T, Battan R, Handler R, Sportsman JR, Heath W, King GL: Preferential elevation of protein kinase C isoform β II and diacylglycerol levels in the aorta and heart of diabetic rats: differential reversibility to glycemic control by islet cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992, 89:11059-11063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aiello LP, Bursell S-E, Clermont A, Duh E, Ishii H, Takagi C, Mori F, Ciulla TA, Ways K, Jirousek M, Smith LEH, King GL: Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced retinal permeability is mediated by protein kinase C in vivo and suppressed by an orally effective β-isoform-selective inhibitor. Diabetes 1997, 46:1473-1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danis RP, Bingaman DP, Jirousek M, Yang Y: Inhibition of intraocular neovascularization caused by retinal ischemia in pigs by PKCβ inhibition with LY 333531. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1998, 39:171-179 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooks P, Clark R, Cheresh D: Requirement of vascular integrin α-v β-3 for angiogenesis. Science 1994, 264:569-571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luna J, Tobe T, Mousa SA, Reilly TM, Campochiaro PA: Antagonists of integrin α-v β-3 inhibit retinal neovascularization in a murine model. Lab Invest 1996, 75:563-573 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammes H, Brownlee M, Jonczyk A, Sutter A, Preissner K: Subcutaneous injection of a cyclic peptide antagonist of vitronectin receptor-type integrins inhibits retinal neovascularization. Nature Med 1996, 2:529-533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishizuka Y: The molecular heterogeneity of protein kinase C and its implications for cellular regulation. Nature 1988, 334:661-665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamaoki T, Hisayo N, Takahashi I, Kato Y, Morimoto M, Tomita F: Staurosporine, a potent inhibitor of phospholipid/Ca++ dependent protein kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1986, 135:397-402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer T, Regenass U, Fabbro D, Alteri E, Rosel J, Muller M, Caravatti G, Matter A: A derivative of staurosporin (CGP 41 251) shows selectivity for protein kinase C inhibition and in vitro anti-proliferative as well as in vivo anti-tumor activity. Int J Cancer 1989, 43:851-856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miggli V, Keller H: On the role of protein kinases in regulating neutrophil actin association with the cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem 1991, 266:7927-7932 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung DL, Brandt-Rauf PW, Weinstein IB, Nishimura S, Yamaizumi Z, Murphy RB, Pincus MR: Evidence that the ras oncogene-encoded p21 protein induces oocyte maturation via activation of protein kinase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992, 89:1993-1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marte BM, Meyer T, Stabel S, Standke GJR, Jaken S, Fabbro D, Hynes NE: Protein kinase C and mammary cell differentiation: involvement of protein kinase C α in the induction of β-casein expression. Cell Growth Differ 1994, 5:239-247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh LYS, Goodyer CG, Olivier A, Yong VW: The promoting effects of bFGF and astrocyte extracellular matrix on process outgrowth by adult human oligodendrocytes are mediated by protein kinase C. Brain Res 1997, 757:236-244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meggio F, Donella-Deana A, Ruzzene M, Brunati AM, Cesaro L, Guerra B, Meyer T, Mett H, Fabbro D, Furet P, Dobrowolska G, Pinna LA: Different susceptibility of protein kinases to staurosporine inhibition: kinetic studies and molecular bases for the resistance of protein kinase CK2. Eur J Biochem 1995, 234:317-322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith LEH, Wesolowski E, McLellan A, Kostyk SK, D’Amato R, Sullivan R, D’Amore PA: Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1994, 35:101-111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tobe T, Okamoto N, Vinores MA, Derevjanik NL, Vinores SA, Zack DJ, Campochiaro PA: Evolution of neovascularization in mice with overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor in photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1998, 39:180-188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tobe T, Ortega S, Luna L, Ozaki H, Okamoto N, Derevjanik NL, Vinores SA, Basilico C, Campochiaro PA: Targeted disruption of the FGF2 gene does not prevent choroidal neovascularization in a murine model. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:1641-1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanks JC, Johnson LV: Vascular atrophy associated with photoreceptor degeneration in mutant mice. LaVail MM Hollyfield JG Anderson RE eds. Retinal Degeneration: Experimental and Clinical Studies. 1985, :pp 189-207 Alan R Liss, New York [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klein R, Klein B: Vision disorders in diabetes. Diabetes in America, ed 2. Edited by National Diabetes Data Group. Washington, DC, National Institutes of Health, 1995, p 294

- 37.Alon T, Hemo I, Itin A, Pe’er J, Stone J, Keshet E: Vascular endothelial growth factor acts as a survival factor for newly formed retinal vessels and has implications for retinopathy of prematurity. Nature Med 1995, 1:1024-1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan SJ: Subretinal neovascularization: natural history of an experimental model. Arch Ophthalmol 1982, 100:1804-1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]