Abstract

We identified a novel missense mutation in the apolipoprotein A-I gene, T2069C Leu174 → Ser, in a patient affected by familial systemic nonneuropathic amyloidosis. The amyloid deposits mostly affected the heart of the proband, who underwent transplantation for end-stage congestive heart failure. Amyloid fibrils of myocardial and periumbilical fat samples immunoreacted exclusively with anti-ApoA-I antibodies. Amyloid fibrils extracted from the heart were constituted, according to amino acid sequencing and mass spectrometry analysis, by an amino-terminal polypeptide ending at Val93 of apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I); no other significant fragments were detected. The mutation segregates with the disease; it was demonstrated in the proband and in an affected uncle and excluded in three healthy siblings. The plasma levels of high-density lipoprotein and apoA-I were significantly lower in the patient than in unaffected individuals. This represents the first case of familial apoA-I amyloidosis in which the mutation is outside the polypeptide fragment deposited as fibrils. Visualization of the mutation in the three-dimensional structure of lipid-free apoA-I, composed of four identical polypeptide chains, indicates that position 174 of one chain is located near position 93 of an adjacent chain and suggests that the amino acid replacement in position 174 is permissive for a proteolytic split at the C-terminal of Val93.

Apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) is the major component of high-density lipoproteins (HDLs), and in the mutated form it represents the amyloidogenic precursor in a few cases of familial systemic amyloidosis. 1 Furthermore, amyloid fibrils constituted by the N-terminal polypeptide of nonmutated apoA-I have been ubiquitously detected in the aortic intima in association with atheromatous plaques in humans 2 and in aged dogs. 3 A variant apoA-I has recently been reported in association with intimal amyloid deposits in a patient. 4 ApoA-I is a 243-amino acid protein synthesized in the liver and small intestine; it binds and transports plasma lipid and increases cholesterol efflux from peripheral tissues in a process called “reverse cholesterol transport.” 5 Approximately 4% of plasma apoA-I is not bound to HDL and circulates as free protein. 6 This exchangeable lipoprotein most likely exhibits different structural conformations in the lipid-free versus the lipid-bound state, and the transition between the two could be extremely important for lipid binding, interaction with a putative receptor, protein catabolism, and pathological misassembly in amyloidosis.

So far, six different mutations in the apoA-I gene have been correlated with various forms of hereditary amyloidosis. Three of these are missense mutations affecting the N-terminal domain of the protein and conferring an extra positive charge on the molecule. 7-12 A further mutation, Leu90 → Pro, apparently does not change the isoelectric point but introduces a more polar residue able to break the helical structure. 13,14 One is a deletion, 11 and one is a deletion/insertion mutation 12 ; both increase the isoelectric point of apoA-I. All amyloidoses associated with known apoA-I mutations as well as all cases in which wild-type apoA-I is deposited in either localized or systemic amyloidosis, share the origin and size of the fibrillar polypeptide. When the primary structure has been studied, it has been shown that the polypeptide isolated from the fibrils starts at the N-terminal of mature apoA-I, and its length ranges from 70 to 100 residues. A further feature shared by all amyloidogenic mutants that cause systemic amyloidosis is the presence of the amino acid replacement inside the polypeptide that accumulates in the amyloid deposits. We have identified a new apoA-I variant associated with hereditary systemic amyloidosis predominantly involving the heart in which the mutation is localized at position 174, outside the 93-residue N-terminal polypeptide that represents the main protein component of the extracted fibrils.

Materials and Methods

Kindred

The family, originating in central Italy, included two affected members, the proband and his maternal uncle, who died at the age of 52. Biopsies of the heart, skin, and gingiva were taken from the uncle and stained with Congo red. The maternal grandfather died at the age of 50 from cardiac failure; pathological documentation is not available. The proband’s parents both died of lung cancer in their fifties. The patient’s brother and two sisters are clinically well, with abdominal fat biopsies negative for amyloid deposits. The only affected living family member is the proband. Maternal relatives underwent clinical evaluation, serum lipid and lipoprotein studies, molecular analysis of the apoA-I gene, and periumbilical fat biopsy for detection and characterization of amyloid deposits. Although the amyloid deposition was systemic, the overall clinical phenotype was dominated by problems related to the massive heart involvement, which was evaluated with cardiac M-mode, 2D, and color-Doppler echocardiogram and by radiolabeled 99Tc aprotinin scintigraphy. 15

Plasma Lipid Studies

Plasma apoA-I and apoB levels were determined in 12-hour fasting samples by immunoturbidimetric methods; high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides were measured by standard clinical chemistry methods.

DNA Amplification and Analysis

Total genomic DNA was isolated from the peripheral blood of the proband, his brother, and two sisters, as well as from 100 control individuals. Three fragments comprising the entire coding region of the apoA-I gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using primers described by Soutar et al. 10 Amplification conditions were 1 minute at 95°C, 50 seconds at 66°C, and 2 minutes at 72°C for 29 cycles.

PCR products were gel purified (QIAQuick gel extraction kit; Qiagen, Chatworth, CA) and sequenced in both directions, using the same oligonucleotides as the primers. Automated sequencing reactions were carried out with an ABI PRISM dye terminator cycle sequencing kit, and the products were analyzed on an ABI 377 DNA sequencer.

To confirm the presence of the mutation, amplified products of exon 4 from the proband and other family members, as well as from 100 controls, were digested with EagI (New England Biolabs), because the mutation creates a new restriction site. Digested products were electrophoresed in a 2.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized with UV light. Genomic DNA from the maternal uncle was extracted from a paraffin-embedded skin biopsy. DNA extraction was performed according to the method of Coates et al. 16 Briefly, 3 × 5 μm slices of the biopsied material were incubated overnight at 55°C in a lysis solution containing proteinase k. Inactivation of proteinase k was achieved by heating at 95°C for 10 minutes, and then the sample was stored at 4°C to facilitate removal of the paraffin layer. PCR amplification of a DNA fragment of 134 bp comprising the mutation site was accomplished by using the same conditions described above and the following primers: 5′GACGCGCTGCGCACGCATCTG3′, 5′CTCAGATGCT-CGGTGGCCTTG3′. The same restriction enzyme, EagI, was used on this purified PCR product to detect the mutation.

Immunohistochemical Studies

Detection of amyloid deposits was carried out through Congo red staining followed by microscopic examination under polarized light. Immunoelectron microscopy was used for in situ characterization of amyloid fibrils, as previously described, 17 using a panel of antibodies purchased from Dako (Copenhagen, Denmark) (anti-k and λ light chains, anti-transthyretin, anti-fibrinogen, anti-lysozyme, anti-amyloid A, anti-β2-microglobulin, and anti-SAP); the rabbit anti-human apoA-I antibody was purchased from Genzyme (San Carlos, CA).

Identification, Isolation, and Characterization of Amyloid Fibrils

Fibrils were isolated from heart tissue by water extraction in the presence of 1.5 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PhMeSO2F) after repeated homogenization in 2 ml of 10 mmol/L Tris/EDTA/140 mmol/L NaCl/0.1% NaN3 (pH 8.0), containing 1.5 mmol/L PhMeSO2F/100 mg of tissue, and centrifugation at 60,000 × g in an ultracentrifuge (Beckman L8–704; Beckman Instruments) for 30 minutes. The yield in fibrils was monitored by the Congo red staining procedure and microscopic analysis of the extracted material.

The extracted fibrils were fractionated by fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) gel filtration on a Superose G12 column (Pharmacia) equilibrated and eluted with 6 mol/L Gdn/HCl and 10 mmol/L sodium phosphate (pH 7.5). The major peak containing the 10-kd band, identified by reduced sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), was dialyzed against distilled water and lyophilized.

The N-terminal sequence of the purified amyloid fibril subunits was determined by adsorptive biphasic column technology, using an HPG1000 A protein sequenator (Hewlett Packard), with the routine 3.0 chemistry procedure and PTH 4 M HPLC method.

The lyophilized amyloid subunit peptide was redissolved in 2% acetic acid/acetonitrile (50:50 v/v) at a concentration of ≅20 pmol/μl and analyzed on an LCQ mass spectrometer (ThermoQuest) by means of electrospray ionization. The sample was introduced at a solvent flow of 3 μl/minute, and data were acquired in a multiple-channel analysis mode at 10 seconds per scan over the m/z range of 500-2000.

Results

The proband presented at the age of 48 with weakness and exertional dyspnea; a testicular biopsy for infertility performed 6 years before had shown the presence of amyloid deposits. Echocardiography performed at presentation revealed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, with a thickened interventricular septum of 18 mm and a partially conserved ejection fraction (40%). Three episodes of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation with syncope developed during the following 2 years and were treated with electrical cardioversion. Recurrence of severe arrhythmias required positioning of a cardiac pacemaker at age 50. The disease progressively evolved through congestive heart failure associated with orthostatic hypotension and mild renal function impairment (serum creatinine approximately 150 μmol/L). Serum lipid studies showed a significant reduction of serum apoA-I and of serum HDL cholesterol in the patient (Table 1) ▶ but not in the unaffected relatives. A diagnosis of amyloidosis was confirmed by positive abdominal fat biopsy staining with Congo red. Radiolabeled 99Tc aprotinin imaging showed marked heart involvement. Congestive heart failure further worsened and became refractory to medical treatment. The patient entered the waiting list for transplantation, which was performed at age 56. Serial myocardial biopsies show no amyloid deposits at 9 months follow-up, and the patient is in excellent condition.

Table 1.

Plasma Lipid and Lipoprotein Levels in the Proband and Unaffected Relatives

| Subject | ApoA-I (110–205 mg/dl) | ApoB (55–220 mg/dl) | Cholesterol (150–200 mg/dl) | HDL cholesterol (≥45 mg/dl) | Triglycerides (40–160 mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proband | 37 | 66 | 110 | 22 | 70 |

| Brother L. | 139 | 103 | 206 | 47 | 107 |

| Sister M.L. | 187 | 76 | 175 | 71 | 116 |

| Sister M.G. | 107 | 71 | 144 | 42 | 59 |

Among the patient’s family relatives, only the maternal uncle had a similar history and outcome with exertional dyspnea and orthopnea at age 47. He was followed up in another center. He was diagnosed with restrictive cardiomyopathy on echocardiographic study. Recurrent supraventricular arrhythmias developed subsequently. Endomyocardial, skin, and gingiva biopsies documented the presence of amyloid deposits, which were not further characterized. He died at age 52 from congestive heart failure.

Molecular Analysis

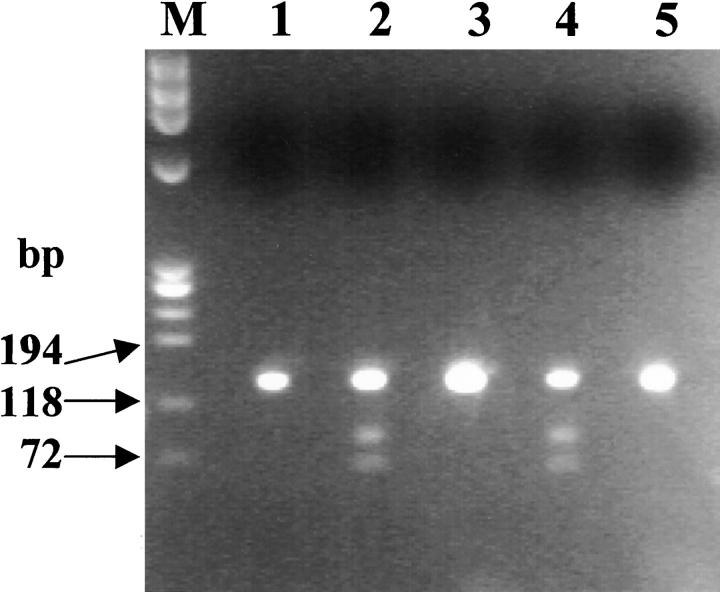

Sequence analysis performed on the entire coding region as well as in the promoter of the apoA-I gene revealed the presence in the proband of a T-to-C transition at nucleotide 2069 of the apoA-1 gene. 18 This mutation produces a Ser for Leu substitution at position 174 of the polypeptide chain. No other point mutations were found in the genomic region analyzed. The T-to-C mutation introduces a new restriction site for the enzyme EagI, which allows confirmation of the point mutation by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. The patient shows the expected fragment of 370 bp (using primers described by Soutar et al 10 ) and two additional fragments of 255 and 115 bp, as would be expected in a heterozygote for the mutated allele. His healthy sisters and brother are not carriers of the mutation, because they possess only the normal fragment. A paraffin-embedded skin biopsy belonging to the maternal uncle, who died of cardiac amyloidosis, was used for the DNA extraction and search for the transition T-to-C in position 2069 of the apoA-1 gene. DNA amplification was accomplished by two primers that delimit a 134-bp sequence that includes the restriction site of EagI created by the mutation. We prepared this short PCR product to avoid the problems created by DNA fragmentation that were expected from the way in which the tissue sample was stored. Digestion of this 134-bp PCR product by EagI confirmed the presence of the mutation in the proband and demonstrated that the mutation was present in the affected uncle (Figure 1) ▶ . The healthy sisters and brother of the proband were all negative.

Figure 1.

RFLP analysis of a 134-bp PCR product from exon 4 of the apoA-1 gene. The samples were digested with EagI. Lane M, marker φX174 HaeIII; Lanes 1, 3, 5, proband’s healthy siblings; Lane 2 proband’s maternal uncle; Lane 4, proband. The PCR product of 134 bp is split into two fragments of 81 and 53 bp only in the presence of the transition T to C in position 2069.

Characterization of the Amyloid Fibril Subunit Protein

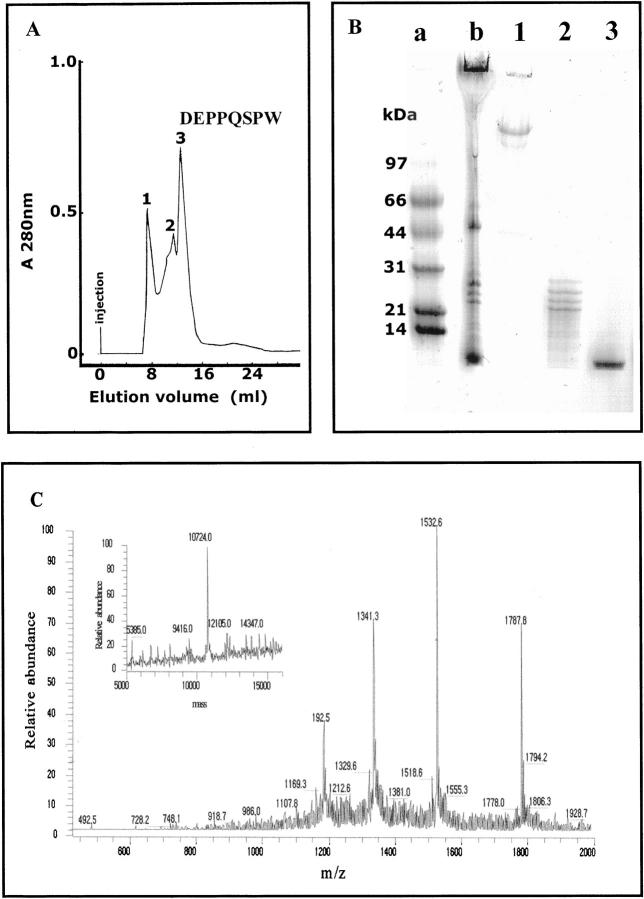

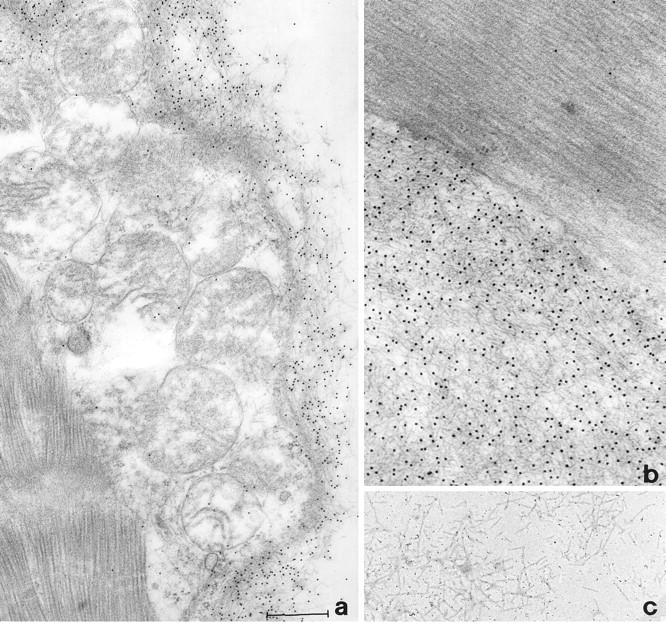

The heart excised at transplantation was grossly enlarged (1.030 kg in weight) and heavily infiltrated by amyloid fibrils (Figure 2) ▶ . The amyloid material isolated from the heart was analyzed by EM and appeared to be constituted by pure straight and rigid fibrils with a diameter of approximately 9 nm; minimal amorphous protein aggregate was associated with the fibrils (Figure 2c) ▶ . The material was separated by gel filtration as reported in Figure 3A ▶ , and the content of the chromatographic fractions was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Figure 3B) ▶ . The main component of the fibrils, represented by the polypeptide eluted in fraction 3 of gel filtration and lane 3 of SDS-PAGE, was analyzed for N-terminal sequence and molecular mass. The sequence of the first 20 N-terminal residues, the first eight of which are indicated at the top of the peak of fraction 3, demonstrates its identity with the N-terminal of mature apoA-I. Determination of the peptide mass showed the presence in fraction 3 of gel filtration of a single polypeptide species of 10,724 ± 2 Da, which is consistent with the 93-residue N-terminal (expected mass 10,720) of mature apoA-I (Figure 3C) ▶ .

Figure 2.

Electron micrographs showing 10-nm immunogold labeling with anti-apoA-I antibody of myocardial amyloid fibrils (a and b) and fibrillar material obtained through the water extraction procedure (c). Bar scale: a, 0.6 μm; b, 0.4 μm; c, 0.5 μm.

Figure 3.

Isolation and characterization of fibril components. A: FPLC gel permeation in Superose G 12 column conducted in 6 mol/L GdnHCl. B: SDS-PAGE of content of chromatographic fractions 1–3. Lane a: Molecular weight markers; Lane b: gel permeation starting material. C: Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry of the polypeptide isolated in fraction 3 of gel filtration. The inset shows the deconvoluted spectrum.

Discussion

This case represents the seventh mutation of the apoA-I gene associated with systemic amyloidosis and the first mutation affecting amino acids outside the N-terminal peptide that self-aggregates into amyloid fibrils. The mutation segregates with the disease, inasmuch as it was present in the maternal uncle, who died of a cardiac amyloidosis, but was absent in nonaffected relatives and in 100 controls. The fibrils were principally localized in the heart, but the disease appeared to be systemic, involving also the kidney and testes. As reported in other cases of apoA-I amyloidosis (reviewed by Genschel et al 1 ), the patient presented with low plasma levels of apoA-I and HDL. Accelerated plasma clearance due to increased catabolism of apoA-I Arg26 variant, both purified from patients and recombinant, has been well documented in humans and in rabbits by Rader et al 19 and Genschel et al, 1 respectively. However, after plasma clearance the extravascular catabolism of variant apoA-I was significantly slower than that of the wild type, indicating possible sequestration in the amyloid deposits. 19

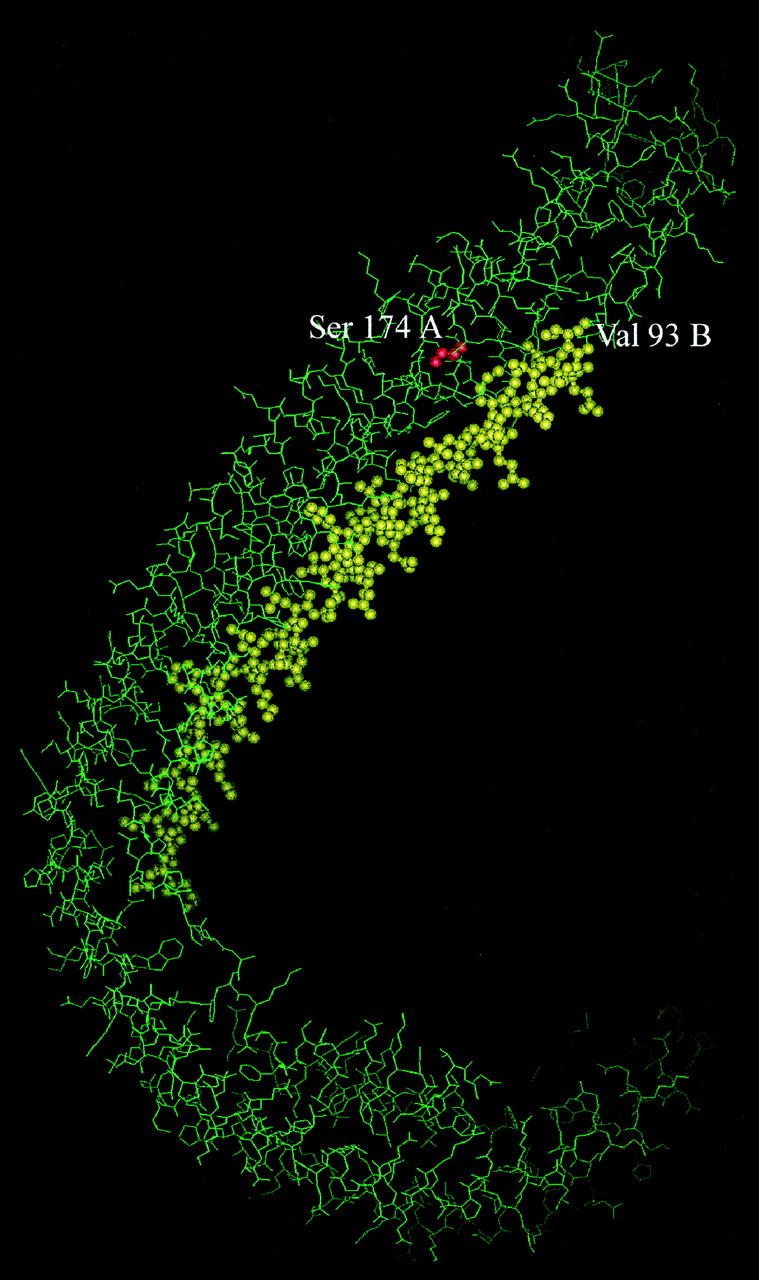

Chemical analysis of the fibril constituents demonstrated the presence of one main fragment consisting of sequence 1–93 of normal apoA-I. This finding emphasizes the amyloidogenic potential of the N-terminal domain of wild-type apoA-I and points to future investigation of the proteolytic event that releases the N-terminal polypeptide from the full-length protein. The compartment in which this putative proteolytic event takes place and the enzyme involved are not known, despite the fact that high susceptibility to cleavage by thrombin near residue 100 has been documented. 20 This apoA-I variant Leu174 → Ser appears to be particularly sensitive to a limited and particularly selective proteolytic event able to release a 93-residue polypeptide. The currently available molecular model of wild-type apoA-I was determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis at 4-Å resolution (Protein Data Bank ID code 1AV1). 21 The limited resolution does not at present allow a detailed analysis of interactions at atomic levels; the following discussion must be considered preliminary, and a better definition of the molecular structure must await more thorough interpretation of our data. However, available 3D structural data offer an important tool for the interpretation of the peculiar pathological pathway of this apoA-I variant. The protein is composed of four identical polypeptide chains, designated A to D, each displaying an α-helical conformation. The four chains run antiparallel to each other in such a way that chains A and B display identical interactions with respect to C and D. Consequently, in our variant the mutated residue 174 in chain A (hereafter referred to as Leu174A) presents an atomic environment that is slightly different from that of residue 174 in chain B. Identical observations can be made for chains C and D. With the present identification system, chain A is equivalent to C and chain B to D. In all cases the mutated residue 174 is relatively close to position 93 (Figure 4) ▶ , which corresponds to the site of proteolytic cleavage: the Cα-Cα distance is 12.9 Å between Leu174A and Val93B, and 12.8 Å between Leu174B and Val93A. The shorter distance between side-chain atoms of the two residues is about 10 Å. In contrast, a different environment is observable around position 174 in the two cases: the side chain of Leu174A in fact interacts with Cγ and Sδ of MetB86 (3.6 Å and 3.5 Å), Cδ of Arg177A (3.9 Å), and Oγ of Ser52C (3.7 Å). On the other hand, Leu174B is close to two other leucines, Leu178B (3.5 Å) and Leu211C (4.3 Å). The effect of the mutation Leu174 → Ser could consequently have contrasting effects in the two cases: in fact, the replacemenmt of a Leu by a Ser in a hydrophobic environment, as in chain B, could be slightly destabilizing for the surrounding residues, and a long-range effect could be transmitted to residues 93–94, making them more exposed to proteolytic cleavage. However, the same mutation on chain A could stabilize the interaction with chain C, because a H bond could be formed between Ser174A and Ser52C. Furthermore, the formation of this new interaction between chains A and C could in some way modify or destabilize the relationship between chains A and B. An important fact nevertheless can be clearly stated from the protein model: a mutation in chain B (or A) should produce the peptide 1B-93B (or 1A-93A), respectively.

Figure 4.

Molecular model of apoA-I (1AV1 of PDB), 21 with the mutation Leu174 → Ser on chain A in red and the peptide from 43B to 93B in yellow.

The possibility that a binding site for a putative protease can be created by two parallel chains is not unlikely. Data obtained through studies of apoA-I epitope mapping with anti apoA-I monoclonal antibodies have demonstrated the presence of several noncontinuous epitopes created by two antiparallel polypeptide chains 22 and therefore encourage the hypothesis that the binding site for a putative protease could be created by two different chains. Furthermore, investigation of apoA-I immunoreactivity has shown that modifications in cholesterol and phospholipid content can induce conformational changes in the quaternary structure and affect the antibody-protein interaction. 23 A similar effect could be exerted by lipids in modulating the interaction between apoA-I and a putative protease. Further studies of limited proteolysis with a lipid-bound and lipid-free apoA-I (wild-type and variant) will be necessary to verify such hypothesis. It is worth noting that the creation of a proteolytic site at the interface of two chains in which at least one presents the Leu174 → Ser mutation would imply that the polypeptide 1–93 could derive from either the wild-type or the variant. To our knowledge this represents a new mechanism able to prime the amyloidogenic process; the contact between wild-type and mutant may also favor the release of amyloidogenic polypeptide from the wild-type, and in vitro studies are in progress to verify this hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Furio Silvestri, head of the Human Pathology Institute, University Hospital, Trieste, Italy, for kindly providing us with the paraffin-embedded skin biopsy of the proband’s maternal uncle; to Dr. Andrea Pilotto and to Dr. Maurizia Grasso, Department of Human Pathology, University Hospital, Pavia, Italy, for processing the skin biopsy sections and extracting the DNA; and to Dr. Carmelina Cardaciotto, Biotechnology Research Laboratories, University Hospital San Matteo, Pavia, Italy, for her valuable help in the molecular studies.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Giampaolo Merlini, Biotechnology Research Laboratories, University Hospital IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, P. le Golgi, 2–27100 Pavia, Italy.

Supported by grants from Telethon (grant n.E.793), European Community Biomed 2 Programme no. BMH4-CT 98-3689, the Italian Ministry of Health, University Hospital IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Probetto d’Ateneo University of Pavia, and MURST.

References

- 1.Genschel J, Haas R, Propsting MJ, Schmidt HHJ: Apolipoprotein A-I induced amyloidosis. FEBS Lett 1998, 430:145-149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westermark P, Mucchiano G, Marthin T, Johnson KH, Sletten K: Apolipoprotein A1-derived amyloid in human aortic atherosclerotic plaques. Am J Pathol 1995, 147:1186-1192 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson KH, Sletten K, Hayden DW, O’Brien TD, Roertgen KE, Westermark P: Pulmonary vascular amyloidosis in aged dogs: a new form of spontaneously occurring amyloidosis derived from apolipoprotein AI. Am J Pathol 1992, 141:1013-1019 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amarzguioui M, Mucchiano G, Haggqvist b, Westermark P, Kavlie A, Sletten K, Prydz H: Extensive intimal apolipoprotein A1-derived amyloid deposits in a patient with an apolipoprotein A1 mutation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998, 242:534-539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glomset JA: The plasma lecithins: cholesterol acyltransferase reaction. J Lipid Res 1968, 9:155-167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishida BY, Frolich J, Fielding CJJ: Prebeta-migrating high density lipoprotein: quantitation in normal and hyperlipidemic plasma by solid phase radioimmunoassay following electrophoretic transfer. Lipid Res 1987, 28:778-786 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nichols WC, Gregg RE, Brewer HB, Benson MD: A mutation in apolipoprotein AI in the Iowa type of familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Genomics 1990, 8:318-323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vigushin DM, Gough J, Allan D, Alguacil A, Penner B, Pettigrew NM, Quinonez G, Bernstein K, Booth SE, Booth DR, Soutar AK, Hawkins PN, Pepys MB: Familial nephropathic systemic amyloidosis caused by apolipoprotein AI variant Arg 26. Q J Med 1994, 87:149-154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booth DR, Tan SY, Booth SE, Hsuan JJ, Totty NF, Nguyen O, Hutton T, Vigushin DM, Tennent GA, Hutchinson WL, Thomson N, Soutar AK, Hawkins PN, Pepys MB: A new apolipoprotein AI variant, Trp50Arg, causes hereditary amyloidosis. Q J Med 1995, 88:695-702 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soutar AK, Hawkins PN, Vigushin DM, Tennent GA, Booth SE, Hutton T, Nguyen O, Totty NF, Feest TG, Hsuan JJ, Pepys MB: Apolipoprotein AI mutation Arg 60 causes autosomal dominant amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992, 89:7389-7393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Persey MR, Booth DR, Booth SE, Van Zyl Smit R, Adam BK, Fattaar AB, Tennent GA, Hawkins PN, Pepys MB: Hereditary nephropathic systemic amyloidosis caused by a novel variant apolipoprotein AI. Kidney Int 1998, 53:276-281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Booth DR, Tan SY, Booth SE, Tennent GA, Hutchinson WL, Hsuan JJ, Totty NF, Truong O, Soutar AK, Hawkins PN, Bruguera M, Caballeria J, Sole M, Campistol JM, Pepys MB: Hereditary hepatic and systemic amyloidosis caused by a new deletion/insertion mutation in the apolipoprotein AI gene. J Clin Invest 1996, 97:2714-2721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asl LH, Liepnieks JJ, Asl KH, Uemichi T, Moulin G, Desjoyaux E, Loire R, Delpech M, Grateau G, Benson MD: Hereditary amyloid cardiomyopathy caused by a variant apolipoprotein A1. Am J Pathol 1999, 154:221-227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh MT: A novel amyloidogenic variant of apolipoprotein AI. Implications for a conformational change leading to cardiomyopathy. Am J Pathol 1999, 1:11-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aprile C, Marinone G, Saponaro R, Bonino C, Merlini G: Cardiac and pleuropulmonary AL amyloid imaging with technetium-99 m labelled aprotinin. Eur J Nucl Med 1995, 22:1393-1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coates PJ, D’Ardenne AJ, Khan G, Kangro HO, Slavin G: Simplified procedure for applying the polymerase chain reaction to routinely fixed paraffin wax. J Clin Pathol 1991, 44:115-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arbustini E, Morbini P, Verga L, Concardi M, Porcu E, Pilotto A, Zorzoli I, Garini P, Anesi E, Merlini G: Light and electron microscopy immunohistochemical characterization of amyloid deposits. Amyloid 1997, 4:157-170 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoulders CC, Kornblihtt AR, Munro BS, Baralle FE: Gene structure of human apolipoprotein A1. Nucleic Acids Res 1983, 9:2827-2837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rader DJ, Gregg RE, Meng MS, Schaefer JR, Zech LA, Benson MD, Brewer HB, Jr: In vivo metabolism of a mutant apolipoprotein, apoA-I Iowa, associated with hypoalphalipoproteinemia, and hereditary systemic amyloidosis. J Lipid Res 1992, 33:755-763 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fielding CJ, Fielding PE: Molecular physiology of reverse cholesterol transport. J Lipid Res 1995, 36:211-228 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borhani DW, Rogers DP, Engler JA, Brouillette CG: Crystal structure of truncated human apolipoprotein A-I suggests a lipid-bound conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997, 94:12291-12296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcel YL, Provost PR, Koa H, Raffai E, Dac NV, Fruchart JC, Rassart E: The epitopes of apolipoprotein A-I define distinct structural domains including a mobile middle region. J Biol Chem 1991, 266:3644-3653 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergeron J, Frank PG, Scales D, Meng QH, Castro G, Marcel YL: Apolipoprotein A-I conformation in reconstituted discoidal lipoproteins varying in phospholipid and cholesterol content. J Biol Chem 1995, 27:27429-27438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]