Abstract

The INK4A gene, a candidate tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 9p21, encodes two protein products, p16 and p19ARF. p16 is a negative cell cycle regulator capable of arresting cells in the G1 phase by inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinases 4 (Cdk4) and 6 (Cdk6), thus preventing pRB phosphorylation. p19ARF prevents Mdm2-mediated neutralization of p53. Loss of INK4A is a frequent molecular alteration involved in the genesis of several neoplasms, including tumors of neuroectodermal origin. This study investigated the frequency of INK4A gene alterations in a series of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) and neurofibromas (NFs). INK4A gene and the p19ARF-specific exon 1β were studied in 11 MPNST samples from 8 patients and 7 neurofibromas. Presence of INK4A deletions was assessed by Southern blotting hybridization and by a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (mPCR). INK4A point mutations were examined by single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) and sequencing. The p16 promoter methylation status was determined by PCR amplification of bisulfite-treated DNA. Homozygous deletions of exon 2, thus affecting both p16 and p19ARF, were identified in MPNSTs from 4 of 8 patients. Deletions, mutations, or silencing by methylation were not identified in the neurofibromas analyzed. Based on our results, we conclude that INK4A deletions are frequent events in MPNSTs and may participate in tumor progression. Silencing of p16 by methylation, which occurs often in several tumor types, is uncommon in MPNSTs.

The INK4 family of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) includes p16, 1 p15, 2 p18, 3 and p19. 4 INK4A gene, also known as CDKN2A gene, is located on the short arm of chromosome 9 (9p21), 5 and its coding sequence consists of three exons with two alternative first exons, E1α and E1β. Splicing of E1α with exons 2 and 3 encodes a 1.5845-kd protein known as p16. p16 complexes with and inactivates cyclin-dependent kinases 4 (Cdk4) and 6 (Cdk6), thus preventing phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (pRB) and subsequent exit from the G1 phase of the cell cycle. If E1β is used instead, the resulting protein product is entirely different due to alternative reading frame and has been designated p19ARF. 6 p19ARF interacts with Mdm2 and prevents Mdm2-mediated degradation of p53. 7,8

INK4A gene alterations, namely point mutations, deletions, and gene silencing by methylation of the 5′ CpG island of the p16 promoter region, have been identified in several tumor types, 5,9-14 including neural crest-derived neoplasms such as melanoma, 15-16 gliomas, 17-20 and neuroblastoma. 21

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) are soft tissue tumors with a generally poor prognosis, thought to arise from Schwann cells and, therefore, to be of neuroectodermal origin. 22 A frequent origin is malignant transformation of a neurofibroma (NF), 23-25 which is the precursor of an estimated two-thirds of MPNSTs. 22 The molecular alterations contributing to MPNST tumorigenesis are at present largely undetermined. Deletions and mutations affecting the p53 gene locus 26,27 as well as overexpression of p53 protein 28-30 have been identified in MPNSTs, but such alterations are absent in NFs. We recently studied p21WAF1 expression, a downstream factor of the p53 pathway, and found no significant differences between MPNSTs and NFs. We also examined factors involved in the RB pathway and, although no significant alterations of pRB were noted in MPNSTs, we observed loss of p27 and overexpression of cyclin E in MPNSTs. 30 The absence of such alterations in NFs suggests that these cell cycle regulators may participate in MPNST tumorigenesis. To further investigate the mechanisms involved in the G1-to-S phase transition, we conducted the present study to examine the frequency of the INK4A gene alterations in MPNSTs and NFs.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Tissue Samples

MPNST samples from eight patients operated on at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) between 1986 and 1997, as well as 3 and 4 NFs resected, respectively, at MSKCC and Mayo Clinic between 1988 and 1999, were examined. Two MPNSTs and four NFs were from patients with family history of neurofibromatosis (NF1). Criteria for the diagnosis of MPNST were the same as those specified in an earlier study. 24 All of the MPNSTs were spindle cell tumors and none were epithelioid in type. Seven tumors were high grade, and one patient (H) had a low grade MPNST arising in a NF (Table 1) ▶ .

Table 1.

Deletion Analysis of INK4A Gene in MPNSTs from Southern Blot Hybridization and Comparative Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay Data

| Patient | Sample no. | INK4A gene deletion analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p16 Southern blot | Exon 2 mPCR | Exon 1β mPCR | ||

| A | 1 | Del | Hom. Del | Hom. Del |

| B* | 2I | Del | Hom. Del | N |

| B* | 2II | Del | Hom. Del | N |

| C | 3 | N | N | N |

| D† | 4 | Del | n/a | Hom. Del |

| E | 5 | N | N | N |

| F† | 6 | N | N | N |

| G | 7 | Del | Hom. Del | Hom. Del |

| G | 9 | Del | Hom. Del | Hom. Del |

| G | 10 | n/a | Hom. Del | Hom. Del |

| G* | 14I | Del | Hom. Del | Hom. Del |

| G* | 14II | Del | Hom. Del | Hom. Del |

| H | 8 | N | N | n/a |

mPCR, comparative multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay; Del, deletion; Hom. Del, homozygous deletion; N, Normal; n/a, not available.

* Same tumor samples.

† NF1 patient.

There were 11 tumor samples representing tissue from 8 primary MPNSTs and 3 recurrences (Table 1) ▶ . Samples were embedded in a cryopreservative solution (OCT Compound, Miles Laboratories, Elkhart, IN), snap-frozen in isopentane precooled in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C. Representative hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections of each frozen block were examined microscopically to confirm the presence of tumor, and only lesions with >70% neoplastic cells were included in the study.

Southern Blot Analysis

A 0.5-kb (kb) complementary DNA (cDNA) fragment containing the human p16 sequence was used as probe to assess deletion and rearrangement of the INK4A gene. A cDNA fragment containing glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) sequences was used as a control probe for DNA quality and quantity. In general, Southern blot analysis was performed as described previously. 10 Briefly, DNA was extracted by a non-organic method (Oncor, Gaithersburg, MD) from the tumor samples. Extracted DNA (7.5-μg aliquots) was digested with TaqI restriction enzyme, and the digested DNA was subjected to electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gels and blotted onto nylon membranes. The membranes were prehybridized with Hybrisol I (Oncor) at 42°C for 1 hour and then incubated overnight at 42°C with probes labeled to high specific activity using α[32P]dCTP (Dupont NEN Research Products, Boston, MA). Hybridized membranes were washed with 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS at 70°C and subjected to autoradiography using intensifying screens at −70°C for 24 to 48 hours. The intensity of the specific INK4A gene and control bands was measured by a phosphoimager (Bas 1000-Mac, Bio Imaging System, Fujix, Fuji). Relative amounts of the INK4A gene present were determined by comparing gene-specific hybridization signals with those obtained using the control probe. 10 Tumor samples presenting <30% of the relative INK4A/control ratio were considered as homozygously deleted.

Polymerase Chain Reaction-Single Stranded Conformation Polymorphism (PCR-SSCP) and Comparative Multiplex PCR Analyses

PCR-SSCP assays were performed on all tumors using a slight modification 10 of the method described by Orita et al. 31 The primers used to amplify the exons 1α (one fragment) and 2 (three overlapping fragments) of the INK4A gene were published by Hussussian et al. 15 For exon 1β the following primer pairs were used: INK4A, exon 1β (440-bp fragment) 5′-TCC CAG TCT GCA GTT AAG G-3′ forward, 5′-GTC TAA GTC GTT GTA ACC CG-3′ reverse; INK4A, exon 1β (160 bp fragments) 5′-AAC ATG GTG CGC AGG TTC-3′ forward, 5′-AGT AGC ATC AGC ACG AGG G-3′ reverse; 3) INK4A exon 2 (set A) 5′- AGC TTC CTT TCC GTC ATG C-3′ forward, 5′- GCA GCA CCA CCA GCG TG-3′ reverse; INK4A exon 2 (set B) 5′-AGC CCA ACT GCG CCG AC-3′ forward, 5′-CCA GGT CCA CGG GCA GA-3′ reverse; INK4A exon 2 (set C) 5′- TGG ACG TGC GCG ATG C-3′ forward, 5′-GGA AGC TCT CAG GGT ACA AAT TC-3′ reverse. DNA was amplified in 28 to 30 cycles of PCR using a thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Foster City, CA) and conditions that have been previously described. 10 Briefly, these PCR reactions were performed in 10-μl volumes containing 80 to 100 ng of template DNA, 2.2 μCi of α[32P]dCTP (Dupont NEN Research Products) or α[33P]dCTP (Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, IL), 3 mmol/L MgC12, 100 μmol/L dNTPs, 3% dimethylsulfoxide, 0.6 U of TaqI polymerase, and 1× PCR buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). The annealing temperatures ranged from 53° to 63°C. For the SSCP analysis of the exon 1β (fragment 1), the PCR product was digested with NarI and EheI restriction enzymes for 2 hours at 37°C. In general, both digested and nondigested products were analyzed by SSCP. The PCR products were denatured and loaded onto a nondenaturing 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 10% glycerol and subjected to electrophoresis at room temperature for 12 to 16 hours at 10 to 12 W. After electrophoresis, the gels were dried and exposed to X-ray film at −70°C for 4 to 24 hours.

An independent DNA amplification was performed for the comparative multiplex PCR assay. Simultaneous amplification of genomic DNA was performed using two sets of primers, one to the target gene sequence under study and the other to an internal control gene sequence. The GAPDH and ANDRR genes were used as internal controls for DNA quality and loading. The primers used for the GAPDH and ANDRR genes can be summarized as follows: GAPDH gene, 5′ TGG TAT CGT GGA AGG ACT CAT GAC 3′ forward, 5′ ATG CCA GTG AGC TTC CCG TTC AGC 3′ reverse; ANDRR gene, 5′ GTG CGC GAA GTG ATC CAG AA 3′ forward, 5′ TCT GGG ACG CAA CCT CTC TC 3′ reverse. The concentration and quality of each DNA template was determined by densitometry and by comparison with mass markers on an agarose gel (Gibco BRL). Each PCR reaction tube contained 50 to 100 ng of genomic DNA, 1× PCR buffer (Promega), 3.2 mmol/L MgCl2, 130 μmol/L dNTP, 5% dimethylsulfoxide, 0.4 μmol/L of each p16 exon 1β primer, 0.4 μmol/L of each ANDRR primer, 0.5 U Taq Polymerase (Promega), and 1 μCi of α[33P]dCTP. Samples were preheated at 95°C for 5 minutes and amplified for 25 cycles with annealing temperatures ranging from 59° to 53°C, followed by an extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. PCR products were run in nondenaturing 6 to 7% polyacrylamide minigels at 1000V for 1 to 1.5 hours. Gels were dried and exposed to sensitive film and to a phosphoimage plate. The presence of the INK4A exons was expressed as the ratio (target-band signal)/(control-band signal). All experiments were conducted at least twice, and to rule out false negative results due to partial DNA degradation, the control selected was longer than the target sequence. To establish potential INK4A allelic losses in the tumor DNA samples, tumor DNA samples characterized previously by the lack of INK4A sequences 10 were used as control DNAs, validating the quantitative nature of the multiplex PCR method. Briefly, varying mixtures of tumor DNA and normal genomic DNA were co-amplified. These tumor-to-normal DNA mixtures represented a range of the INK4A exons content, varying from 0% of target (tumor sample control) to 100% of target (normal DNA counterpart). Samples presenting <20% of the control signal were considered homozygously deleted, and those presenting <50% as heterozygously deleted for exon 1β.

Analysis of Methylation

The methylation status of the 5′CpG island in the promoter region of the p16 gene was determined with the CpG WizTM p16 Methylation kit (Oncor). Briefly, 0.5 to 1 μg of DNA was denatured with NaOH 3 mol/L at 50°C for 10 minutes and treated with sodium bisulfite following manufacturer’s protocol. After completion of the DNA modification, the DNA was purified by precipitation. The dissolved DNA was amplified by PCR using primers specific for the methylated (M) or unmethylated (U) sequences. Two to 3 μl of template (corresponding to treated DNA, positive control for methylated DNA, positive control for unmethylated sequences, and dH2O as negative control) were amplified in presence of 10× Universal PCR buffer, 2.5 mmol/L dNTP mix, U or M primers, and AmpliTaq Gold (Perkin Elmer), under the following conditions: preheating at 95°C for 12 minutes, followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 45 seconds, at 66°C for 45 seconds, and at 72°C for 1 minute. The PCR product was analyzed on a 2% agarose gel. DNA methylation was determined by the presence of a 145-bp fragment in those samples amplified with the M primers.

Results

Deletion Analysis of the INK4A Gene in MPNSTs and NFs

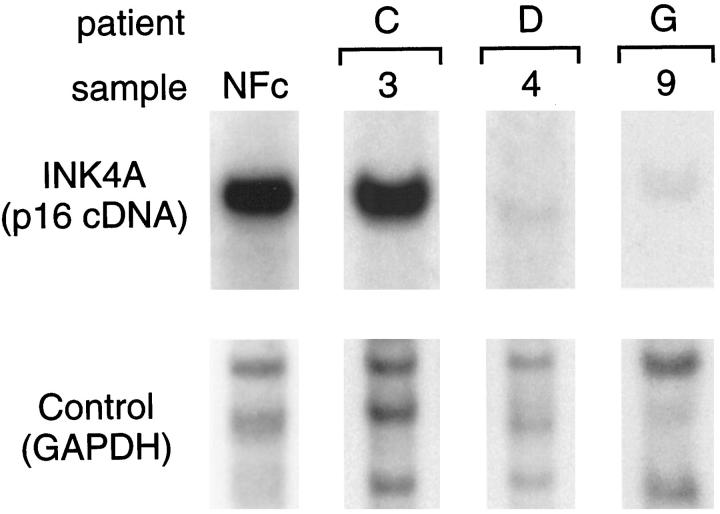

Table 1 ▶ summarizes the results of the deletion analyses. Homozygous deletions affecting the INK4A gene were identified in 6 of 10 (60%) MPNST samples from 4 of 8 patients studied by Southern blotting. Recurrent tumors from one case also showed INK4A homozygous deletions. Southern blot analysis of DNA extracted from seven NFs identified normal INK4A gene bands in all cases. Fig. 1 ▶ illustrates normal and altered INK4A band patterns in representative MPNSTs and NFs.

Figure 1.

Southern blot analysis of the INK4A gene in MPNSTs. Genomic DNA was digested with the restriction enzyme TaqI. Southern blot was performed using a specific p16 complementary-DNA probe, as described in Materials and Methods. A control probe (GAPDH) for DNA loading was used in the analysis. The INK4A p16-specific signals shown in this figure correspond to bands of 3.7 kb (kb). The control probe signal shown corresponds to 3.7- to 5.0-kb bands. A NF sample (NFc) and a MPNST sample 3 depict a normal band pattern. MPNST samples 4 and 9 illustrate a homozygous deletion of the INK4A-p16 gene. NF, neurofibroma; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase.

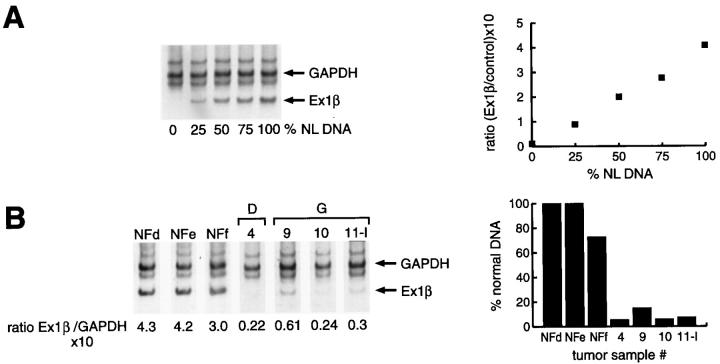

Comparative multiplex PCR analysis for exon 2 of the INK4A gene confirmed homozygous deletions of this locus in 6 of 10 different MPNST samples, corresponding to 3 of 4 patients with INK4A gene deletion by Southern blotting. The fourth sample could not be successfully analyzed due to limited tissue. The status of the p19ARF exon 1β was successfully analyzed by comparative multiplex PCR in 10 tumors from 7 patients. Homozygous deletion of exon 1β was detected in 6 of 10 different MPNST samples, three primary tumors and three tumor recurrences (Figure 2) ▶ . The samples were from tumors showing concomitant loss of the exon 2 of the INK4A gene, as well as p16 deletion by Southern blotting. Exon 1β was preserved in one case displaying INK4A gene and exon 2 loss. One sample, showing no deletion of the INK4A gene or exon 2, could not be successfully analyzed by multiplex PCR for exon 1β.

Figure 2.

Deletion analysis of the INK4A-exon 1β gene in MPNSTs and NFs. A: the standardization of the assay by incremental amplification of INK4A-exon 1β with an increasing normal DNA target. To the right, the control curve was constructed with the relative INK4A/control ratios and the amount of normal DNA included in each sample. B: absence of INK4A-exon 1β in MPNST samples 4, 9, 10, and 11-I, with retention in the three neurofibroma samples (NFd, NFe, NFf). To the right, the ratios (INK4A/control) obtained for the tumor samples are compared to those obtained for normal control DNA. Note the reduction in the ratios (expressed as a percentage of normal DNA) in the same cases. Samples 9, 10, and 11-I correspond to the same patient (G). NL, normal.

Mutation Analysis of Exons 1α, 1β, and 2 of the INK4A Gene

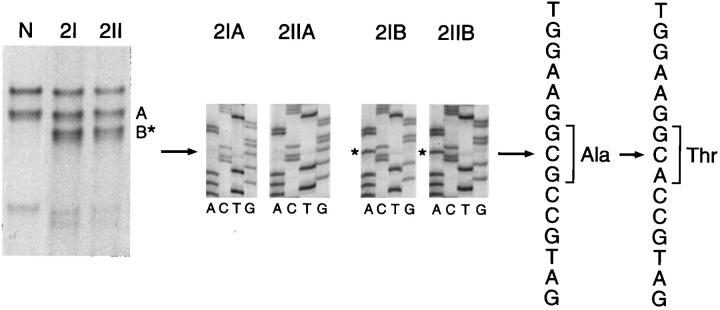

The analysis by PCR-SSCP for exons 1α, 1β, and 2 of the INK4A gene identified altered fragment mobility shifts involving exon 2 in one MPNST case. Sequencing disclosed the presence of a polymorphism associated with G→A transversion at codon 148 (Ala→Thr; Figure 3 ▶ ). In another MPNST case, a double silent transition at codon 83 CAC→CAT (His→His) and codon 84 GAC→GAT (Asp→Asp) was also observed.

Figure 3.

INK4A point mutations analysis in MPNSTs. The left panel illustrates the band pattern obtained for the tumor samples 2I and 2II (2I and 2II derived from the same tumor), by PCR-SSCP analysis. Additional INK4A bands (B*) were identified in the tumor samples 2I and 2II. Direct sequencing results of the PCR products obtained from the elution of normal (A) and abnormal (B*) bands from the same cases are shown in the middle panel, corresponding to the forward sequences. The asterisks indicate the base change. The single base substitution (G→A, arrow) produces the polymorphism (Ala→Thr), as indicated in the forward sequence.

Methylation Analysis of the INK4A Gene Promoter

In all samples analysis of the methylation status of the p16 promoter was performed. Methylation-specific fragments were absent in all MPNST and NF samples (data not shown).

Discussion

MPNSTs are rare neoplasms in the general population. 23 However, they develop with increased frequency in the setting of neurofibromatosis type 1 and are strongly associated with a pre-existing NF. 23-25 This observation implies that NFs and MPNSTs participate in a model of multistage tumor progression analogous to the colonic adenoma-carcinoma sequence.

Study of the genetic alterations contributing to such evolution includes the analysis of the p53 26-30 and RB pathways. 30 Mutations of the p53 gene 26,27 as well as p53 overexpression 28-30 have been described in MPNSTs, whereas they are absent in NFs. Underexpression of p27 and overexpression of cyclin E appear also to be involved in the MPNST tumor progression scheme. 30

In the present series, we identified homozygous deletions of the INK4A gene in 60% of the MPNST samples analyzed, derived from 4 of 8 patients. The Southern blot hybridization findings were confirmed by comparative multiplex PCR, identifying homozygous deletion of exon 2 of the INK4A gene in all of the successfully analyzed cases. Findings in tumors from patients with and without NF1 did not differ. By contrast, none of the seven NF samples analyzed displayed INK4A gene deletion.

In these cases we also analyzed the p19ARF-related exon 1β. We identified homozygous deletions in 6 of 11 MPNST samples derived from 3 patients. All three cases displayed concomitant INK4A gene deletion. On the other hand, exon 1β was preserved in one patient showing p16 deletion. Cases showing normal p16 gene status also displayed normal exon 1β.

PCR-SSCP analysis and sequencing of INK4A gene exons 1α, 1β, and 2 did not identify tumor-specific point mutations, but revealed two polymorphisms involving exon 2. The first, in codon 148, has been already described, 32-35 and the second is a double silent transition involving codons 83 and 84 of exon 2. Similarly, we did not detect de novo methylation of the exon 1α promoter. Absence of tumor-specific point mutations and methylation of the INK4A promoter were also observed in a large cohort of soft tissue malignancies. 14

Although the series is small, these data suggest that INK4A gene deletions are frequent events in MPNSTs, occurring in 50% of the patients. The frequency of INK4A gene deletion in MPNSTs is particularly high, because it exceeds the previously reported occurrence of p16 deletion in other tumor types such as soft tissue sarcomas. 14 Notably, within that series of soft tissue malignant neoplasms the incidence of INK4A/INK4B deletions was highest in MPNSTs (40%). 14 The significance of this finding is further emphasized by the absence of INK4A gene deletion in NFs. These findings in concert suggest that deletion of the INK4A gene is an important step in the process of malignant transformation of NF.

Moreover, the concomitant loss of exons 1β and 2 suggests concurrent molecular abnormalities in p16 and p19ARF proteins. p16 functions as a negative cell cycle regulator through the CDK4/cyclin D1/pRB pathway. On the other hand, p19ARF has been reported to interact with Mdm2 protein and to interfere with Mdm2-mediated degradation of p53. Therefore, a single genetic event involving INK4A gene in chromosome 9p21 may simultaneously eliminate two tumor suppressor proteins, p16 and p19ARF, affecting both pRB and p53 pathways. The concomitant inactivation of both pRB and p53 is considered critical in the process of tumorigenesis. 14,36,37 In addition to p16 and p19ARF deletion, we have previously identified p27 underexpression and cyclin E overexpression in MPNSTs but not in NFs. 30 These alterations likely act in concert to facilitate the G1-to-S progression of the cell cycle in MPNSTs and appear to participate in the tumor progression of the NF-MPNST sequence.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Carlos Cordon-Cardo, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021. E-mail: cordon-c@mskcc.org.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA 47179.

This work was presented in part at the 1999 Annual Meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, March 20–26, San Francisco.

The first two named authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Serrano M, Hannon GJ, Beach D: A new regulatory motif in cell cycle control causing specific inhibition of cyclin D/CDK4. Nature 1993, 366:704-707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannon GJ, Beach D: p15INK4B is a potential effector of TGFb-induced cell cycle arrest. Nature 1994, 371:257-261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan KL, Jenkins CW, Li Y, Nichols MA, Wu X, O’Keefe CL, Matera AG, Xiong Y: Growth suppression by p18, a p16 INK4A/MTS1 and p14 INK4A/MTS2-related CDK6 inhibitor, correlates with wild-type pRb function. Genes Dev 1994, 8:2939-2952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan FKM, Zhang J, Cheng L, Shapiro DN, Winoto A: Identification of human and mouse p19, a novel CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitor with homology to p16 INK4. Mol Cell Biol 1995, 15:2682-2688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamb A, Gruis NA, Weaver-Feldhaus J, Qingyun L, Harshman, Tavtigian SV, Stockert E, Day RS, Johnson BE, Skolnick MH: A cell cycle regulator potentially involved in genesis of many tumor types. Science 1994, 264:436-440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quelle DE, Zindy F, Ashmun RA, Sherr CJ: Alternative reading frames of the INK4A tumor suppressor gene encode two unrelated proteins capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cell 1995, 83:993-1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pomerantz J, Schreiber-Agus N, Liegeois N, Silverman A, Alland L, Chin L, Potes J, Chen K, Orlow I, Lee HW, Cordon-Cardo C, De Pinho RA: The INK4A tumor suppressor gene product, p19ARF, interacts with MDM2, and neutralizes MDM2’s inhibition of p53. Cell 1998, 92:713-723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yarbrough WG: ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF-INK4A locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppressor pathways. Cell 1998, 92:725-734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nobori T, Miura K, Wu DJ, Lois A, Takabayashi K, Carson DA: Deletions of cyclin-dependent kinase-4 inhibitor gene in multiple human cancers. Nature 1994, 368:753-756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orlow I, Lacombe L, Hannon GJ, Serrano M, Pellicer I, Dalbagni G, Reuter VE, Zhang ZF, Beach D, Cordon-Cardo C: Deletion of p16 and p15 genes in human bladder tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995, 87:1524-1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geradts J, Wilson PA: High frequency of aberrant p16(INK4A) expression in human breast cancer. Am J Pathol 1996, 149:15-20 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovar H, Jug G, Aryee DN, Zoubek A, Ambros P, Gryber B, Windhager R, Gadner H: Among genes involved in RB dependent cell cycle regulatory cascade, the p16 tumor suppressor gene is frequently lost in the Ewing family of tumors. Oncogene 1997, 15:2225-2232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider-Stock R, Radig K, Roessner A: Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 9q21 (p16 gene) uncommon in soft tissue sarcomas. Mol Carcinog 1997, 18:63-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlow I, Drobnjak M, Zhang ZF, Lewis J, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF, Cordon-Cardo C: Alterations of the INK4A and INKF4B genes in adult soft tissue sarcomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999, 91:73-79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hussussian CJ, Struewing JP, Goldstein AM, Higgins PA, Ally DS, Sheahan MD, Clark WH, Jr, Tucker MA, Dracopoli NC: Germline p16 mutations in familial melanoma. Nat Genet 1994, 8:15-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartkova J, Lukas J, Guldberg P, Alsner J, Kirkin AF, Zeuthen J, Bartek J: The p16-cyclin D/Cdk4-pRb pathway as a functional unit frequently altered in melanoma pathogenesis. Cancer Res 1996, 56:5475-5483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jen J, Harper JW, Bigner SH, Papadopoulos N, Markowitz S, Wilson JK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B: Deletion of p16 and p15 genes in brain tumors. Cancer Res 1994, 54:6353-6358 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt EE, Ichimura K, Reinfenberger G, Collins P: CDKN2 (p16/MTS1) gene deletion or CDK4 amplification occurs in the majority of glioblastomas. Cancer Res 1994, 54:6321-6324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker DG, Duan W, Popovic EA, Kaye AH, Tomlinson FH, Lavin M: Homozygous deletions of the multiple tumor suppessor gene 1 in the progression of human astrocytomas. Cancer Res 1995, 55:20-23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fueyo J, Gomez-Manzano C, Bruner JM, SaitoY, Zhang B, Zhang W, Levin VA, Yung WK, Kyritsis AP: Hypermethylation of the CpG island of p16/CDKN2A correlates with gene inactivation in gliomas. Oncogene 1996, 13:1615–1619 [PubMed]

- 21.Takita J, Hayashi Y, Kohno T, Yamaguchi N, Hanada R, Yamamoto K, Yokota J: Deletion map of chromosome 9 and p16 (CDKN2A) gene alterations in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res 1997, 57:907-912 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodruff JM: Pathology of major peripheral nerve sheath neoplasms. Weiss SW Brooks JSJ eds. Soft Tissue Tumors. 1996, :pp 129-161 Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ducatman BS, Scheithauer BW, Piepgras DG, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM: Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 120 cases. Cancer 1986, 57:2006-2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hruban RH, Shiu MH, Senie RT, Woodruff JM: Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the buttock and lower extremity: a study of 43 cases. Cancer 1990, 66:1253-1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kourea HP, Bilsky MH, Leung DH, Lewis JJ, Woodruff JM: Subdiaphragmatic and intrathoracic paraspinal malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 25 patients and 26 tumors. Cancer 1998, 82:2191-2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menon AG, Anderson KM, Riccardi VM, Chung RY, Whaley JM, Yandell DW, Farmer GE, Freiman RN, Lee JK, Li FP, Barker DF, Ledbetter DH, Kleider A, Martuza RL, Gusella JF, Seizinger BR: Chromosome 17p deletions, and p53 gene mutations associated with the formation of malignant neurofibrosarcomas in von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990, 87:5435-5439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Legius E, Dierick H, Wu R, Hall BK, Marynen P, Cassiman JJ, Glover TW: TP53 mutations are frequent in malignant NF1 tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1994, 10:250-255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kindblom LG, Ahlden M, Meis-Kindblom JM, Stenman G: Immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of p53, MDM2, proliferating cell nuclear antigen and Ki67 in benign and malignant nerve sheath tumors. Virchows Arch 1995, 427:19-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halling KC, Scheithauer BW, Halling A, Nascimento AG, Ziesmer SC, Roche PC, Wollan PC: p53 expression in neurofibroma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: an immunohistochemical study of sporadic, and NF1-associated tumors. Am J Clin Pathol 1996, 106:282-288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kourea HP, Cordon-Cardo C, Dudas M, Leung D, Woodruff JM: Expression of p27kip and other cell cycle regulators in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibromas. The emerging role of p27Kip in malignant transformation of neurofibromas. Am J Pathol 1999, 155:1885-1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orita M, Suzuki Y, Sekiya T, Hayashi K: Rapid and sensitive detection of point mutations and DNA polymorphisms using the polymerase chain reaction. Genomics 1989, 5:874-879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang SY, Klein-Szanto AJ, Sauter ER, Shafarenko M, Mitsunaga S, Nobori T, Carson DA, Ridge JA, Goodrow TL: Higher frequency of alterations in the p16/CDKN2 gene in squamous cell carcinoma cell lines than in primary tumors of the head and neck. Cancer Res 1994, 54:5050-5053 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen W, Weghorst CM, Sabourin CL, Wang Y, Wang D, Bostwick DG, Stoner GD: Absence of p16/MTS1 gene mutations in human prostate cancer. Carcinogenesis 1996, 17:2603-2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato K, Schauble B, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H: Infrequent alterations of the p15, p16, CDK4 and cyclin D1 genes in non-astrocytic human brain tumors. Int J Cancer 1996, 66:305-308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castresana JS, Gomez L, Garcia-Miguel P, Queizan A, Pestana A: Mutational analysis of the p16 gene in human neuroblastomas. Mol Carcinog 1997, 18:129-133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams BO, Remington L, Albert DM, Mukai S, Bronson RT, Jacks T: Cooperative tumorigenic effects of germline mutations in Rb and p53. Nat Genet 1994, 7:480-484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cordon-Cardo C, Zhang ZF, Dalbagni G, Drobjnak M, Charytonowicz E, Hu SX, Xu HJ, Reuter VE, Benedict WF: Cooperative effects of p53 and pRB alterations in primary superficial bladder tumors. Cancer Res 1997, 57:1217-1221 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]