Abstract

We earlier identified a variant of CD30 (CD30v) that retains only the cytoplasmic region of the authentic CD30. This variant is expressed in alveolar macrophages. CD30v can activate the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) as CD30, and its overexpression in HL-60 induced a differentiated phenotype. To better understand the physiological and pathological functions of CD30v, expression of this variant was examined using a multiple approach to examine 238 samples of human malignant myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms. Screening by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) revealed expression of CD30v transcripts in 52 of 72, 7 of 11, 63 of 90, and 7 of 30 samples of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myeloid blast crisis of myeloproliferative disorders (MBC), and lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) of B- and T-cell origin, respectively. CD30v expression was high in monocyte-oriented AMLs (FAB M4 and M5), B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL), and multiple myeloma (MM). Using the specific antibody HCD30C2, prepared using a peptide corresponding to the nine amino acids of the amino-terminal CD30v, expression of CD30v protein was detected in 10 of 25 and 2 of 10 AML and ALL samples, respectively. In AMLs, immunocytochemical detection of CD30v revealed the presence of loose clusters of CD30v-expressing cells dispersed amid a population of CD30v-negative blasts. Finally, the parallel expression of CD30v mRNA and protein, as evidenced by Northern and Western blotting, was confirmed in selected cases of AMLs and LPDs. A significant correlation was found between expressions of CD30v and CD30 ligand transcripts in AML and LPD (P = 0.02, odds ratio = 3.2). The association of CD30v with signal-transducing proteins, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 2, and TRAF5 was demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation analysis, as was demonstrated for authentic CD30 protein. Expression of transcripts for TRAF1, TRAF2, TRAF3, and TRAF5, as demonstrated by RT-PCR, was noted in leukemic blasts that express CD30v. Collectively, frequent expression of CD30v along with TRAF proteins in human neoplastic cells of myeloid and lymphoid origin provide supportive evidence for biological and possible pathological functions of this protein in the growth and differentiation of a variety of myeloid and lymphoid cells.

CD30 is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily, which comprises a group of cysteine-rich receptor proteins such as TNFRI, TNFRII, CD27, CD40, 4–1BB, OX40, and CD95 (Fas/APO-1). 1-4 The ligand for CD30 (CD30L), a member of a parallel superfamily that includes TNF, lymphotoxin (LT)-α, LT-β, CD27L, 4–1BBL, OX40L, and CD95L/FasL, has effects on CD30-expressing cells, including activation, proliferation, differentiation, and cell death, depending on cell type, stage of differentiation, transformation status, and the presence of other stimuli. 5-7

Expression of CD30 ligand (CD30L) was noted in activated T cells, resting neutrophils, eosinophils, and B cells, as well as in the cells of various human malignant myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms. 5,8-10 Cross-linking of cell-surface CD30L by an antibody or a soluble CD30 (CD30-Fc) can transduce signals leading to gene expression and metabolic activation in granulocytes and T cells. 11 On the other hand, cross-linking CD30 induced Ca2+ influx in T-cell lines, 12 and signals mediated by CD30 were seen to regulate gene expression through activation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). 13,14 We and other investigators have demonstrated that CD30 binds to tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) proteins TRAF1, 2, and 5 in the C-terminal region. 15-20 We recently reported that the C-terminal cytoplasmic region has three independent NF-κB activating subdomains, all of which can function independently. The C-terminally located two subdomains serve as TRAF binding domains, but the most N-terminal subdomain can activate NF-κB, without interacting with TRAF proteins. 21

A variant form of CD30 (CD30v), which retains only the cytoplasmic domain and can mediate signals to activate NF-κB, was identified in our laboratory at the University of Tokyo. 22 CD30v expression was induced by phorbol ester in a human myeloid leukemia cell line HL-60 and is constitutively expressed in alveolar macrophages. Overexpression of the CD30v activated NF-κB and induced NBT reduction activity in HL-60 cells, findings that suggested a role for this molecule in the activation and/or differentiation of myeloid cells.

In the present study, we investigated expression of CD30v mRNA and protein in a broad series of primary human neoplastic cells of myeloid and lymphoid origin, using a combination of reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), Northern blotting, and immunostaining with a specific anti-CD30v polyclonal antibody raised against the amino-terminal peptide of CD30v. CD30v was frequently expressed in malignant cells of myeloid and B-lymphoid phenotypes, whereas a more restricted expression of CD30v was found in T-cell tumors. This distribution significantly correlated with expression of the physiological CD30-specific ligand CD30L. The in vivo interaction of CD30v with TRAF2 and TRAF5, as well as expression of transcripts for TRAF proteins in CD30v-expressing blast cells, was also evident. CD30v may possibly have a role in growth regulation in the case of human malignant myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms.

Materials and Methods

Cell Samples

Our study included cells from peripheral blood (PB) or bone marrow (BM) of 203 patients with acute myeloid leukemias (AMLs) (n = 72), myeloid blast crisis (MBC) of chronic myeloproliferative disorders (n = 11), B- and T-cell lymphoproliferative diseases (n = 120), including B- and T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemias (ALLs), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), prolymphocytic leukemia (PLL), hairy cell leukemia (HCL), high- and low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHLs), multiple myeloma (MM), and adult T-cell leukemia (ATL) caused by HTLV-1. Diagnoses were based on cell morphology, immunophenotyping, enzyme cytochemistry, and clinical parameters, according to guidelines of international consensus. 10,23-25 The cells were either immediately used for RNA extraction or frozen in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and stored at −80°C until use. In addition, 35 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded BM samples from AML patients or ALL patients were also studied.

Cell Lines

The HL-60, 293T, and COS-7 cell lines were obtained through the Japanese Cancer Research Resources Bank (Tokyo, Japan) and Fujisaki Cell Biology Center (Okayama, Japan), and the Hodgkin’s disease (HD)-derived cell lines L428 and KM-H2, as well as the HEL, HUT-102, Karpas 299, and K-562 cell lines, were purchased from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (Braunschweig, Germany). With the exception of 293T and COS-7 cell lines, cultured in Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% FCS, all other cell lines studied were maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS. When indicated, HL-60 cells were treated with 50 ng/ml of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA), as reported. 22

Cell Isolation and Purification

Anticoagulated PB and BM aspirates were collected from leukemia/lymphoma patients before any therapy and after informed consent was obtained. Neoplastic cells were isolated by centrifugation on a Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) gradient and, with the exclusion of T-cell-derived malignancies, were further purified by T-cell depletion with anti-CD2 immunomagnetic beads (Dynabeads; Dynal, Oslo, Norway). 10 In the case of MM, tumor cells were further purified by positive indirect immunoselection with the plasma cell-specific monoclonal antibody BB-4. 26 After purification procedures, all of the samples contained over 95% neoplastic cells.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cell lines and leukemic cell samples with Isogen (Nippon-Gene, Toyama, Japan) or by the guanidinium thiocyanate method. 27 Template cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA with a Ready-To-Go T-Primed First-Strand kit (Pharmacia) or by avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase (Promega Co., Madison, WI) in a 20-μl reaction mix. For each PCR, 2.0 or 2.5 μl was used as the template cDNA. All cDNAs were checked for first-strand synthesis with a primer pair specific for β-actin. The primer pairs for CD30v are specific for CD30v, being the sense primer located within the unique nucleotide sequence of CD30v cDNA. 22 Sequences and nucleotide positions of primers are as follows: CD30v: (sense) 5′-GAGTGTGGGGCGTCTCTGTG-3′ (nucleotide position 27–46) or 5′-AGTGTGGGGCGTCTCTGTGTTC-3′ (nucleotide position 28–49), (antisense) 5′-GTTCTGTCTCCTGCTCGGGGTAGT-3′ (nucleotide position 598–575) or 5′-CGCTCCTCAGCTGCGTTGAG-3′ (nucleotide position 228–247); TRAF1: (sense) 5′-GCCCCTGATGAGAATGAGTT-3′ (nucleotide position 109–128), (antisense) 5′-CTCATGCTCTTGCACAGACT-3′ (nucleotide position 380–399) 28 ; TRAF2: (sense) 5′-ACAAGTGTGAGAAGTGCCAC-3′ (nucleotide position 302–321), (antisense) 5′-GACGCACACATGGAAGTTCT-3′ (nucleotide position 582–601) 28 ; TRAF3: (sense) 5′-TTTGTCCCTGAACAAGGAGG-3′ (nucleotide position 311–330), (antisense) 5′-AACTGCTCTGCACAACCTCT-3′ (nucleotide position 581–600) 29 ; TRAF5: (sense) 5′-GACTTTGAGCCCAGTATAGA-3′ (nucleotide position 130–149) (antisense) 5′-CCCAGAATAACCTTCCCATT-3′ (nucleotide position 403–422) 30 ; β-actin: (sense) 5′-ATGGATGATGATATCGCCGCG-3′ (nucleotide position 42–62), (antisense) 5′-TTCTCCATGTCGTCCCAGTTG-3′ (nucleotide position 272–292). 31 Primer pairs specific for CD30 and CD30L were as reported elsewhere. 10 Hot-start RT-PCR reactions were performed with Hot Wax beads (Invitrogen, Carlsberg, CA) after the condition for each primer set was optimized. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. In the case of CD30v, 10 μl of amplified cDNAs was run on 1.5% agarose gels, blotted onto nylon membranes (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), and hybridized with 2 × 10 6 cpm/ml of 5′-end-labeled oligomer probes. Sequences and nucleotide positions of probes are as follows: CD30v probe 1 (recognizing CD30vl alone): 5′-GTCCAGACCTCCCAGCCCAAG C-3′ (position 175–196 of CD30v); CD30v probe 2 (recognizing both CD30vl and s forms): 53-CCTTCCTGAGCCCCGGGTGTCCA-3′ (position 396–418 of CD30v).

To exclude the possibility that CD30v primer pairs amplify from genomic DNA a fragment of the same size as that from cDNA templates, PCR was carried out on genomic DNA templates as well as on non-reverse-transcribed RNA and cDNAs synthesized from TPA-treated HL-60 RNA after treatment with RNase-free DNaseI (Promega).

Northern Blot Analysis

Northern blot analysis was carried out essentially as described. 10 Briefly, 10 μg/lane of total RNA, extracted using the guanidinium thiocyanate method, were size-fractionated on 1% agarose gels containing 6.7% formaldehyde and subsequently blotted onto nylon membranes (Boehringer Mannheim). Filters were hybridized in 1.0 mol/L NaCl and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 68°C with 1.0 × 10 6 cpm/ml of random primed-labeled probes. 10 After washings to a final stringency of 0.2× standard sodium citrate and 0.1% SDS at 65°C, filters were exposed to XAR-5 films (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) at −80°C. The probes used were as follows: a 980-bp CD30-specific cDNA fragment obtained by cloning in pGEM-T vector (Promega), a RT-PCR product from the HD-derived cell line KM-H2, and an 838-bp human β-actin-specific cDNA fragment obtained by cloning in the same vector a RT-PCR product from hemopoietic cell lines.

Preparation of Antiserum

Anti-CD30v polyclonal antibodies were generated essentially as reported. 32 However, at variance with a previously reported antiserum obtained by immunizing rabbits with the whole CD30v molecule expressed as fusion protein, 22 the present antiserum was generated by immunizing rabbits with an oligopeptide (MSQPLMETC) corresponding to the nine N-terminal amino acids of CD30v. Immune sera were affinity-purified over antigen columns prepared with CH Sepharose (Pharmacia); the purified antibody was named HCD30C2.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting experiments using anti-CD30v or anti-CD30 (Ber-H2; DAKO Japan, Kyoto, Japan) antibodies were done as described. 22 Briefly, COS-7 cells transfected with expression vectors for CD30v or CD30 were lysed in SDS-RIPA buffer (0.1% w/v SDS, 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% v/v Nonidet P-40 (NP40), 0.1% w/v sodium deoxycholate, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 10 μg/ml aprotinin) on ice for 10 minutes and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm at 4°C for 20 minutes, and protein concentrations of the supernatants were measured using a Bio-Rad Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Samples of cell lysates (100 μg) were incubated with HCD30C2 or Ber-H2 at 4°C for 60 minutes, and immune complexes were absorbed to protein G-Sepharose (Pharmacia), washed thoroughly with RIPA buffer, boiled with Laemmli’s sample buffer, and separated using an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (PAGE). Then the samples were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA), followed by blocking for 12 hours with 10% w/v skim milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) at 4°C, and then incubated with 5 μg/ml HCD30C2 or Ber-H2 for 1 hour at 4°C. Peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibodies (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, England) were used to detect immunoreactive proteins, using an ECL kit (Amersham). In some cases, cell lysates (100 μg) of primary leukemic samples and HL-60 cells treated with TPA or not, were directly subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and sequentially incubated with the HCD30C2 antiserum and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, as described above.

Indirect Immunofluorescence Cytochemistry and Immunohistochemistry

Indirect immunofluorescence study was done using COS-7 cells transfected with expression vectors for CD30v or CD30, untreated HL-60 cells, and those treated with 50 ng/ml TPA and primary bone marrow-derived leukemic cells. Briefly, cells were grown on Lab-Tek Chamber Slides (Nunc, Naperville, IL) or plated on slide glass coated with poly-l-lysine hydrobromide (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) by Cytospin 2 (Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA) and fixed for 10 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde. After blocking with 10% v/v normal swine serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 minutes, cells were incubated with the primary antibody (HCD30C2 or Ber-H2) for 1 hour at room temperature. After extensive washings in PBS, cells were incubated with fluorescent isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated isotype-matched immunoglobulins (TAGO, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes at room temperature and examined under a Nikon fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunocytochemistry of CD30v was performed using an avidin-biotin-complex technique on BM samples from leukemia patients and normal controls and the HCD30C2 antibody. Sections of 4 μm were prepared from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded specimens, and the glass slides used had been pretreated with poly-l-lysine hydrobromide (Sigma Chemicals), followed by drying at 65°C for 12 hours. Sections were dewaxed in xylene, hydrated in a graded series of ethanol, washed with distilled water, boiled for 10 minutes in 5% urea in a microwave oven, and cooled for 30 minutes before incubation with HCD30C2 or Ber-H2. A Histofine kit (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) was used for color reaction for alkaline phosphatase, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following reagents (all from Dako Japan) were used in this study: biotinylated swine anti-rabbit IgG, biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG, and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptoavidine.

Cell Labeling and Immunoprecipitation

COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with pME-CD30v 22 or an empty vector, and after 40 hours, about 2 × 10 6 cells in semiconfluent culture were washed with PBS (−) and cultured in phosphate-free Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium for 18 hours before the addition of 1 mCi/ml of [32P]orthophosphate (carrier-free; ICN Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, CA). The cells were then incubated for a further 5–6 hours before immunoprecipitation. Cells were lysed as described above, and the cell lysates were first incubated with protein G Sepharose (Pharmacia) at 4°C for 60 minutes. After centrifugation, supernatants were incubated with 2 μg of HCD30C2 at 4°C for 60 minutes and then incubated with protein G Sepharose (Pharmacia) at 4°C for 60 minutes. For competition studies, 2 μg of HCD30C2 was preincubated with 10 μg of the antigen peptide for 30 minutes on ice. The immune complexes absorbed to protein G Sepharose were washed with modified RIPA buffer. The samples were boiled with Laemmli’s buffer for 5 minutes and subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography.

In Vivo Binding Assay

Transient cotransfection and coimmunoprecipitation analyses were made using 293T cells. Expression vectors for mouse TRAF2 and TRAF5 tagged with FLAG were as described. 17,21,22 Cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of an expression plasmid for human CD30v or CD30, and 1 μg of expression vectors for FLAG-tagged TRAF proteins, using Lipofectin reagent (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). The cells were lysed in HNE buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 0.1% Nonidet-P40, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L PMSF, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 mg/ml pepstatin), the lysates were first immunoprecipitated with HCD30C2 or Ber-H2, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Eastman Kodak) and peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody, using an ECL kit (Amersham).

Statistical Analysis

The association between the expression of CD30v and that of CD30L in AMLs and LPDs was statistically assessed by χ 2 test. 33

Results

Validation of Specific Primer Sets for Investigating CD30v Expression by RT-PCR

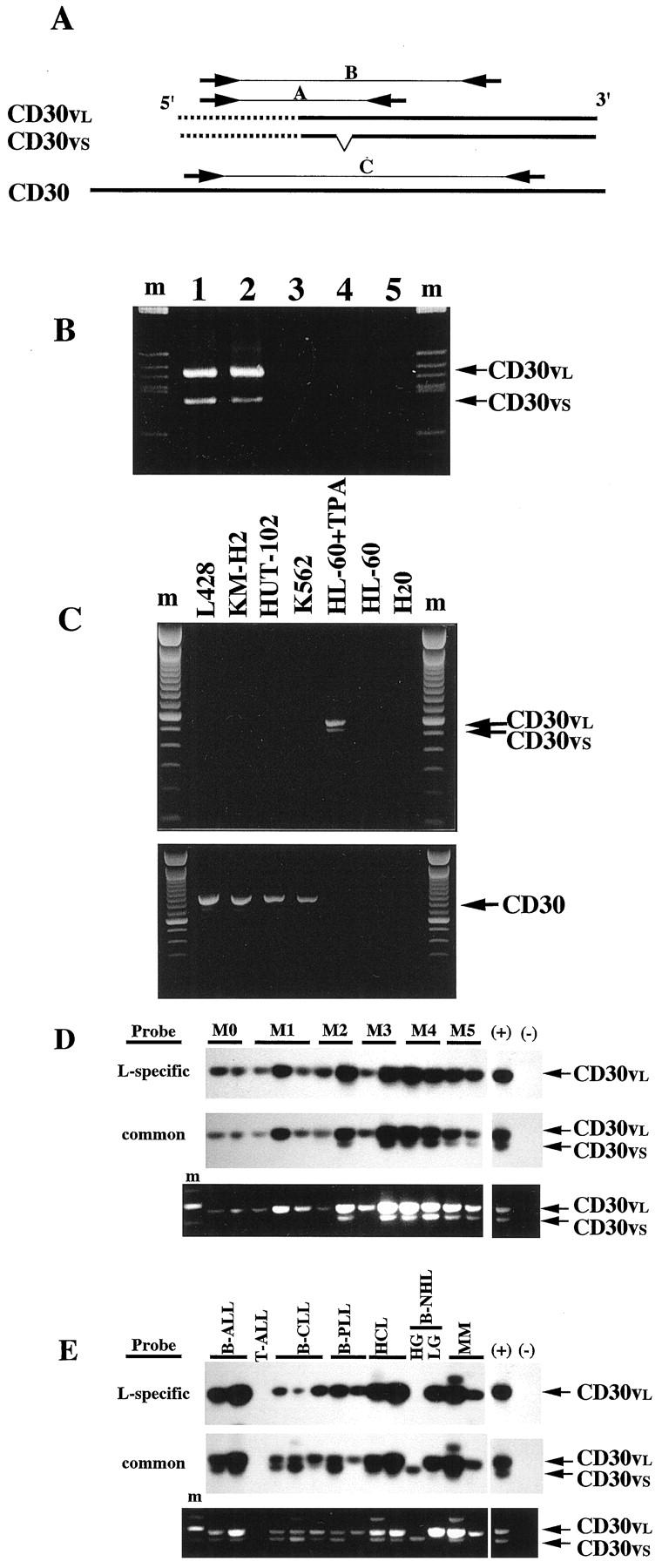

Expression of CD30v transcripts in malignant cells of myeloid and lymphoid origin was investigated by RT-PCR. Because organization of the CD30 gene has yet to be defined, primer pairs cannot be designed to locate in different exons for discrimination between products from cDNA and those from genomic DNA. Therefore, we prepared two sets of primer pairs, whose nucleotide sequences were selected by choosing, in both cases, a sequence within the 5′ unique CD30v sequence (nucleotide position 27–49) for forward primers, and reverse primers localized either upstream of the putative translation initiation codon (nucleotide position 228–247, Figure 1A ▶ , primer pair A) or less than 100 bp upstream of the stop codon (nucleotide position 598–575, Figure 1A ▶ , primer pair B).

Figure 1.

RT-PCR analysis of CD30v transcripts. A: Position of the primer pairs for CD30v and CD30. Common sequences between CD30 and CD30v cDNA are indicated by the bold line. Unique sequences in the CD30v cDNA are indicated by the dotted line. Paired arrows A, B, and C indicate positions of each primer in the sequences. B: Specific amplification of the cDNA template by CD30v primers. PCR was run for 40 cycles in a 50-μl reaction volume, and a 10-μl aliquot was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. Lanes 1 and 2, cDNA samples prepared from RNA, without or with DNase treatment, respectively; lane 3, an RNA sample without reverse transcription; lane 4, a control genomic DNA sample; lane 5, without template. m, molecular weight marker. C: The primer pair for CD30v does not cross-amplify CD30 transcripts. RT-PCR analysis of CD30v (top) and CD30 (bottom) in the CD30-positive cell lines: L428, KMH-2, HUT-102, and K562. m, molecular weight marker. D and E: RT-PCR analysis of CD30v transcripts in myeloid leukemia samples (D) and samples of LPD (E). Representative results of Southern blot analysis of RT-PCR products are shown in the top panels. Probes used for hybridization are indicated on the left. The bottom panel shows the ethidium bromide staining of the agarose gel. Positions for PCR products corresponding to the longer and shorter CD30v transcripts (CD30vs and CD30vl, respectively) are indicated on the right. M0, M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5 indicate FAB classification. ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; PLL, prolymphocytic leukemia; HCL, hairy cell leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; HG, high grade; LG, low grade; MM, multiple myeloma; ATL, adult T-cell leukemia; (+), positive control; (−), negative control.

Before screening studies were carried out, preliminary experiments were done with these two sets of primer pairs to rule out the possibility of amplifying contaminated genomic DNA. For this purpose, we first tested the effect of DNase I treatment of the RNA samples on CD30v-specific amplified products. As shown in Figure 1B ▶ (lanes 1 and 2), the same PCR products were obtained by amplifying with CD30v-specific primers A cDNAs that have been synthesized from RNAs treated with RNase-free DNase I or not. On the other hand, PCR products were never observed with the same primer pair when either non-reverse-transcribed RNA or control genomic DNA from peripheral blood mononuclear cells was used as the template (Figure 1B ▶ , lanes 3 and 4). Similar results were obtained with primer pair B, which amplifies the larger CD30v fragment (sense nucleotide position 27–49; antisense nucleotide position 598–575; data not shown).

In addition, further experiments were designed to rule out the possibility that primer pairs specific for CD30v might cross-amplify CD30 transcripts. When cDNAs from CD30-expressing cell lines 1-6,22 were used, amplification with both CD30v primer pairs failed to produce specific PCR products (Figure 1C ▶ , upper panel, and data not shown). Conversely, CD30 expression in CD30-positive cell lines was confirmed by RT-PCR (Figure 1C ▶ , lower panel), by using primer pairs specific for the full-length form of CD30 (Figure 1A ▶ , primer pair C). On the other hand, the same primer pair did not give rise to specific amplified products when TPA-treated HL-60 cells were tested (Figure 1C ▶ , lower panel). Taken together, these results indicated that RT-PCR products obtained with our CD30v primer pairs specifically derived from CD30v cDNA templates and not from genomic DNA or full-length CD30 cDNA molecules.

Expression of CD30v mRNA in Malignant Cells of Myeloid Origin

Expression of CD30v-specific transcripts was investigated in blast cells purified from 72 AML cases, and 11 cases of MBC evolved from previous chronic myeloproliferative disorders (CMDs). As shown in Table 1 ▶ and Figure 1D, a ▶ broad expression of CD30v mRNA was found in these malignancies. In detail, significant amounts of CD30v mRNA were detected in 52 of 72 (72.2%) AMLs and 7 of 11 (63%) MBC of previous CMDs (Table 1) ▶ . Although not reaching a statistical significance, a higher frequency of CD30v expression (81.8%) was detected in monocytic and myelomonocytic subtypes of AMLs (FAB M4 and M5), as compared to immature-intermediate AML phenotypes (FAB M0, M1, and M2), in which CD30v-positive samples accounted for 66.7% of cases (Table 1) ▶ . Even though RT-PCR procedures were not specifically conditioned to be quantitative, leukemic samples from promyelocytic (FAB M3) and monocytic-oriented leukemias (FAB M4 and M5) appeared to express higher levels of CD30v transcripts overall than did those from M0, M1, and M2 AML subtypes (Figure 1D) ▶ . With regard to the expression of long (CD30vl) and short (CD30vs) forms of CD30v mRNA, 22 almost all cases (50 of 52) showed expression of either the long form (CD30vl) alone (30 cases) or the long form in association with the short form (CD30vs) (20 cases), the latter being expressed in the absence of CD30vl only in two M5 AML samples (Table 1) ▶ .

Table 1.

Expression of CD30v Transcripts in Human Myeloid Hematopoietic Malignancies

| Diagnosis (no. of cases tested) | CD30v-neg. | CD30v-pos. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | l+/s+ | l+/s− | l−/s+ | ||

| AML (72) | 20 | 52 | 20 | 30 | 2 |

| M0 (5) | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | — |

| M1 (17) | 6 | 11 | 4 | 7 | — |

| M2 (11) | 4 | 7 | 2 | 5 | — |

| M3 (4) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | — |

| M4 (18) | 4 | 14 | 6 | 8 | — |

| M5 (15) | 2 | 13 | 4 | 7 | 2 |

| M6 (1) | — | 1 | 1 | — | — |

| M7 (1) | 1 | — | — | — | — |

| MBC (11) | 4 | 7 | 5 | 2 | — |

| CML (9) | 2 | 7 | 5 | 2 | — |

| PV (1) | 1 | — | — | — | — |

| IM (1) | 1 | — | — | — | — |

CD30v mRNA expression was evaluated by RT-PCR. Specificity of amplified products was confirmed by Southern blotting hybridization, with oligomer probes chosen either within the region deleted in the CD30vs form or in a conserved region of both cDNAs. Based on these results, CD30v-positive cases (CD30v-pos.) were divided into three subgroups, i.e., CD30vl+/CD30vs+ (l+/s+), CD30vl+/CD30vs− (l+/s−), and CD30vl−/CD30vs+ (l−/s+).

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MBC, myeloid blast crisis of myeloproliferative disorders; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; PV, polycythemia vera; IM, idiopathic myelofibrosis.

Expression of CD30v mRNA in Malignant Cells of Lymphoid Origin

CD30v expression was also surveyed in 90 cases of B-cell tumors and 30 cases of T-cell tumors. As was the case for myeloid cells, 70% of B-cell malignancies (63 of 90) expressed CD30v transcripts, and again the great majority (60 of 63) showed either expression of the CD30vl isoform alone (33 cases) or coexpression of CD30vl and CD30vs (27 cases; Table 2 ▶ and Figure 1E ▶ ). About 50–60% of CD30v-expressing cases were observed in B-lineage ALLs, high-grade B-NHLs, B-PLL, HCL, and low-grade B-NHL. Interestingly, a very high rate of CD30v expression was observed in B-CLLs (26 of 27) and in immunopurified BB-4+ malignant plasma cells (6 of 6). In contrast, less than 25% of T-cell malignancies, including ATL caused by HTLV-1, expressed CD30v transcripts.

Table 2.

Expression of CD30v Transcripts in Human Lymphoid Hematopoietic Malignancies

| Diagnosis (no. of cases tested) | CD30v-neg. | CD30v-pos. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | l+/s+ | l+/s− | l−/s+ | ||

| B-cell tumors (90) | 27 | 63 | 27 | 33 | 3 |

| B-lineage ALL (13) | 7 | 6 | 2 | 4 | — |

| B-CLL (27) | 1 | 26 | 12 | 12 | 2 |

| B-PLL (5) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | — |

| HCL (13) | 6 | 7 | 5 | 2 | — |

| B-NHL HG (16) | 6 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| LG (10) | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | — |

| MM (6) | — | 6 | 2 | 4 | — |

| T-cell tumors (30) | 23 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| T-ALL (14) | 11 | 3 | 1 | 2 | — |

| T-PLL (2) | 2 | — | — | — | — |

| T-NHL HG (2) | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| LG (1) | 1 | — | — | — | — |

| ATL (11) | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

CD30v mRNA expression was evaluated by RT-PCR. Specificity of amplified products was confirmed by Southern blot hybridization, with oligomer probes chosen either within the region deleted in the CD30vs form or in a conserved region of both cDNAs. Based on these results, CD30v-positive cases (CD30v-pos.) were divided into three subgroups, i.e., CD30vl+/CD30vs+ (l+/s+), CD30vl+/CD30vs− (l+/s−), and CD30vl−/CD30vs+ (l−/s+).

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; PLL, prolymphocytic leukemia; HCL, hairy cell leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; HG, high grade; LG, low grade; MM, multiple myeloma; ATLL, adult T-cell leukemia.

Detection of Recombinant and Native CD30v Protein by a Specific Anti-CD30v Polyclonal Antibody (HCD30C2)

Because expression of a given gene is not always associated with the actual detection of its protein product, 34 we attempted to survey the expression of CD30v protein in malignant cells of myeloid and lymphoid origin. For this, we generated a rabbit polyclonal antibody, termed HCD30C2, using as the immunogen the amino-terminal peptide of the CD30v. Because this amino acid sequence is shared by CD30 and CD30v proteins (amino acids 464–472 and 1–9, respectively), we first tested the specificity of HCD30C2 reactivity. To do this, immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting experiments were done using COS-7 cells transfected with expression vectors specific for CD30 or CD30v.

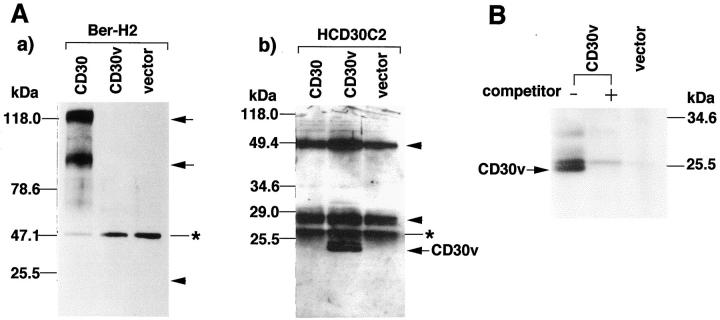

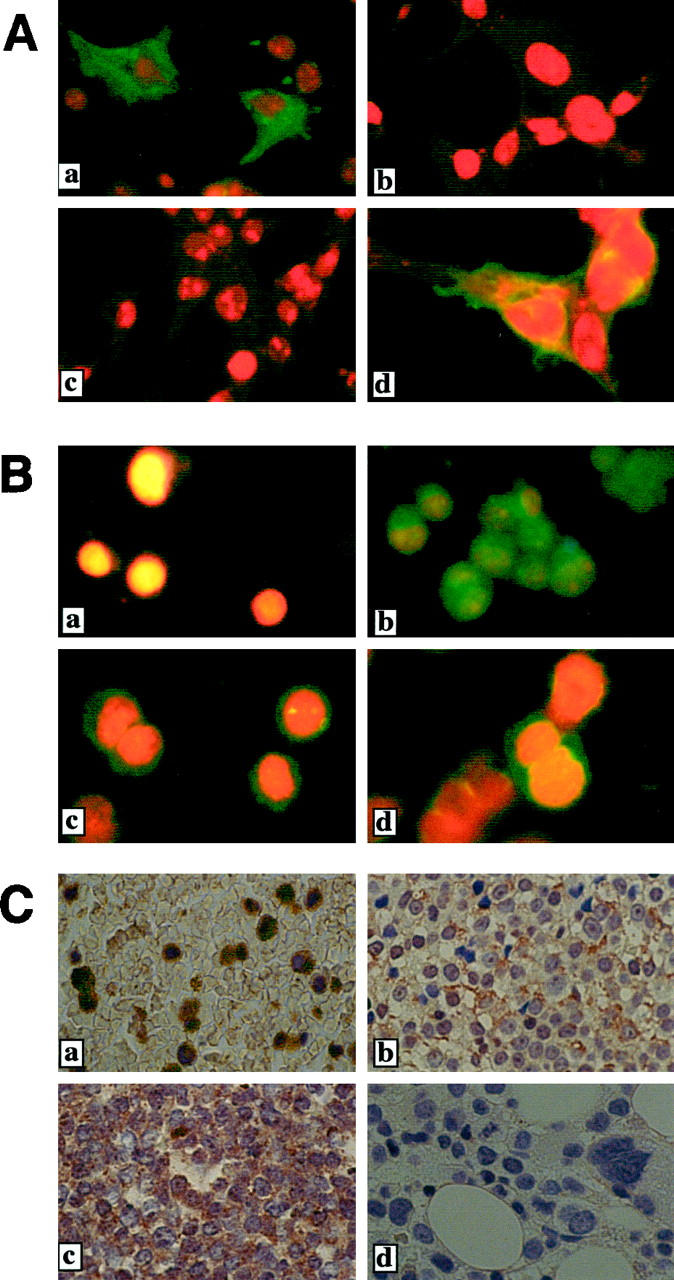

In agreement with previously reported data, 22 HCD30C2 antibodies, while failing to detect CD30 protein in CD30-transfected COS-7 cells (Figure 2A ▶ b), did recognize two closely migrating bands with an apparent molecular mass of about 25 kd, but only in cells transfected with CD30v (Figure 2Ab ▶ ). Some additional bands in most samples had a molecular mass slightly higher than that of bands identified as CD30v-specific (asterisk in Figure 2Ab ▶ ), and this was considered a nonspecific reactivity of HCD30C2 antibodies with some unidentified components of cellular lysates. Conversely, the anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody Ber-H2 strongly reacted with COS-7 cells transfected with the full-length form of CD30, being totally unreactive with cells transfected with CD30v (Figure 2Aa ▶ ).

Figure 2.

Specificity of the peptide antibody. A: Immunoblot analysis of CD30v. a: Immunoblotting with Ber-H2 detected CD30 proteins (arrows) but not CD30v (arrowhead). An asterisk indicates the position of the immunoglobulin heavy chain. The lane labeled “vector” indicates a sample prepared from 293T cells transfected with an empty vector (pME18S). b: HCD30C2 reacted with CD30v proteins (arrow) but not with CD30 proteins. An asterisk to the right of the figure indicates the position of a nonspecific band detected in all samples. Arrowheads indicate the positions of immunoglobulins. B: Competition of CD30v immunoprecipitation by the immunogen peptide. Immunoprecipitation of 32P-labeled 293T cells transfected with CD30v expression vector by HCD30C2, with or without pretreatment with the immunogen (10 μg), as indicated above the figure. Competitor + indicates pretreatment of HCD30C2 with the immunogen.

A specific reaction was also tested by competition studies in immunoprecipitation experiments using the immunogen as a competitor. CD30v-transfected COS-7 cells along with control COS-7 cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate, and cell lysates were prepared. Immunoprecipitation of the lysates was carried out with HCD30C2, with or without preincubation with the immunogen peptide. Preincubation with the immunogen abolished the immunoprecipitation of CD30v protein (Figure 2B) ▶ . Taken together, these results demonstrated that HCD30C2 reacts to CD30v protein but not to CD30 protein.

In a subsequent series of experiments, we examined the potential of HCD30C2 to recognize CD30v protein in viable cells fixed by paraformaldehyde and in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded samples. We first asked if CD30v protein in paraformaldehyde-fixed cells could be detected by indirect immunofluorescence cytochemistry. Cytoplasmic reactivity was clearly observed in CD30v-transfected COS-7 cells but not in CD30-transfected COS-7 cells by HCD30C2 (Figure 3A, a and c) ▶ . Conversely, Ber-H2 specifically reacted to COS-7 cells transfected with CD30 but not to those transfected with CD30v, as expected (Figure 3A, b and d) ▶ . Consistently, HCD30C2 reacted to cytoplasmic antigen only in the TPA-treated HL-60 cells, not in untreated HL-60 cells (Figure 3B, a and b) ▶ . Similarly, HCD30C2 antibodies recognized both recombinant and native CD30v protein, as expressed in CD30v-transfected COS-7 cells and TPA-treated HL-60 cells, respectively, in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded preparations (data not shown).

Figure 3.

CD30v protein in cells detected with the use of a specific antibody. A: Indirect immunofluorescence cytochemistry of transfected cell lines. COS-7 cells transfected with pME-CD30v (a and b) or pME-CD30 (c and d) were examined using HCD30C2 (a and c) or Ber-H2 (b and d). B: Indirect immunofluorescence cytochemistry of HL-60 and AML samples. Cells were examined using HCD30C2 antibody. a, untreated HL-60; b, TPA-treated HL-60; c and d, AML samples. C: Immunohistochemistry of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded bone marrow samples. CD30v protein was evident in leukemia cells but not in normal bone marrow samples. a–c, bone marrow samples of leukemia patients (AML M3, AML M4, and ALL L2, respectively); d, a normal bone marrow sample.

Collectively, these results demonstrated that HCD30C2 can specifically recognize CD30v but not CD30 proteins in immunoblots, immunoprecipitation, and indirect immunofluorescence on paraformaldehyde-fixed cells, as well as in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded specimens.

Expression of CD30v Protein in Acute Leukemia Cells of Myeloid and Lymphoid Origin

Using the CD30v-specific polyclonal antibody HCD30C2, we next surveyed the expression of CD30v protein in 35 BM samples from patients affected by acute leukemias of myeloid or lymphoid origin, by indirect immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry (Figure 3B, c and d ▶ , Figure 3C ▶ , and Table 3 ▶ ). Indirect immunofluorescence studies of paraformaldehyde-fixed bone marrow samples from six AML patients revealed CD30v protein in the cytoplasm in two of six samples (Figure 3B, c and d ▶ , and Table 3 ▶ ). In addition, immunohistochemical studies with HCD30C2 revealed a significant expression of CD30v in 8 of 19 AML cases and 2 of 10 ALLs. As shown in Figure 3C ▶ , cytoplasmic expression of CD30v was detectable in leukemic blasts, whereas no staining was observed in normal bone marrow specimens. In particular, whereas in some cases CD30v-expressing blasts were seen as loose clusters interspersed among a population of CD30v-negative cells (Figure 3Ca ▶ ), in other samples expression of CD30v was characterized by a disperse granular staining of the cytoplasm, in the majority of blasts (Figure 3C, b and c) ▶ . Thus immunological screening for CD30v protein expression in acute leukemia samples revealed CD30v-expressing cases in 10 of 25 AML samples and 2 of 10 ALL samples (Table 3) ▶ . Finally, in agreement with reported data, 10 all leukemic samples lacked expression of CD30 antigens, as investigated by immunostaining with anti-CD30 mAb Ber-H2 antibody (data not shown).

Table 3.

Expression of CD30v Protein in Human Acute Leukemias

| Diagnosis (no. of cases tested) | CD30v-neg. | CD30v-pos. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | IHC | IF | ||

| AML (25) | 15 | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| M1 (2) | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| M2 (4) | 2 | 2 | 2 | — |

| M3 (5) | 3 | 2 | 2 | — |

| M4 (9) | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| M5 (4) | 3 | 1 | — | 1 |

| M6 (1) | — | 1 | 1 | — |

| ALL (10) | 8 | 2 | 2 | — |

| L1 (3) | 2 | 1 | 1 | — |

| L2 (2) | 2 | — | — | — |

| UC (5) | 4 | 1 | 1 | — |

CD30v expression was evaluated, using the anti-CD30v-specific polyclonal antibody HCD30C2, by immunohistochemistry (IHC) or by indirect immunofluorescence (IF) on BM specimens of patients with acute leukemia of myeloid or lymphoid origin.

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; UC, unclassified.

Combined Analysis of CD30v Expression in Human Malignant Myeloid and Lymphoid Neoplasms by Northern Blotting and Immunoblotting

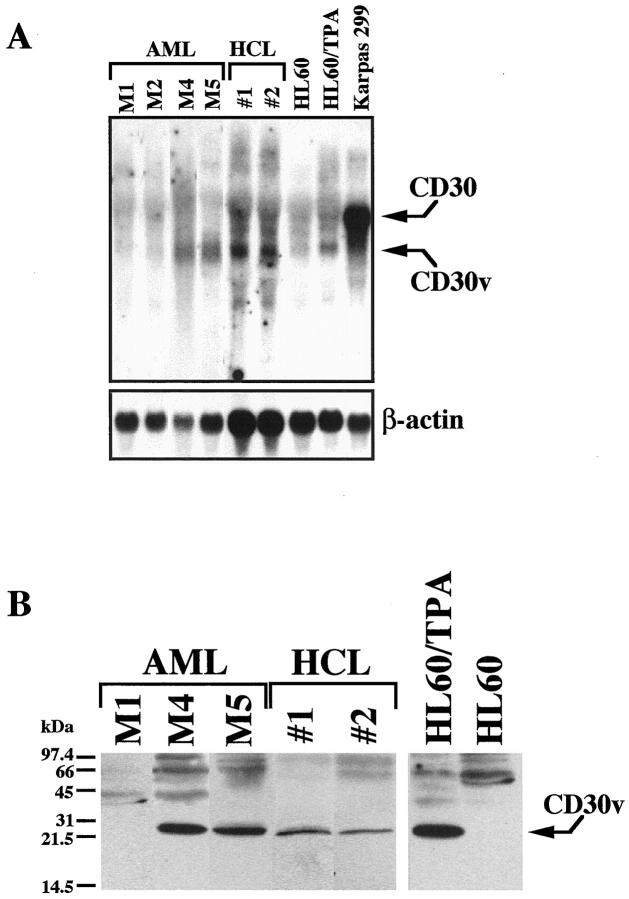

Screening by RT-PCR with a specific primer pair for CD30v and immunostaining with HCD30C2 showed frequent expression of CD30v in human malignant myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms. For further confirmation, we examined the parallel expression of CD30v transcripts and protein in four AML cases (M1, M2, M4, and M5 subtypes) and two HCL cases by Northern blotting and immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 4A ▶ , Northern blot analysis revealed a 2.3-kb signal corresponding to CD30v transcripts 22 in two of four AMLs (M4 and M5 subtypes) and in the HCL cases tested, which were all documented as CD30v-positive by RT-PCR. Consistently, no specific bands were detected in two AML cases (M1 and M2 subtypes) that lacked expression of CD30v mRNA by RT-PCR. Finally, a specific CD30v transcript was also clearly detected in TPA-treated HL-60, but not in HL-60 cells (Figure 4A) ▶ , used as positive and negative controls, respectively. 22 Immunoblotting experiments with HCD30C2 antibodies confirmed the presence of a 25-kd CD30v-specific band in those cases, ie, two AMLs, two HCLs, and TPA-treated HL-60, expressing significant amount of CD30v transcripts by RT-PCR and Northern blotting, but not in a CD30v mRNA-negative case (M1 or unstimulated HL-60) (Figure 4B) ▶ .

Figure 4.

Combined analysis of CD30v expression with Northern blot and immunoblot. A: Expression of CD30v gene in hematopoietic neoplasms. Total RNA (10 μg/lane) from AML (M1, M2, M4, and M5 phenotype) and HCL (two cases) was analyzed by Northern blotting with a CD30 probe. Untreated or TPA-treated HL-60 cells served as negative and positive controls for CD30v expression, respectively. The Karpas 299 cell line, derived from a CD30+ large anaplastic lymphoma, was used as a positive control for CD30 expression. Positions for CD30 and CD30v mRNAs are indicated on the right. The same blot was also probed using a specific β-actin cDNA fragment (bottom). B: Detection of CD30v protein in cell lysates from three AML (M1, M4, and M5) and two HCL cases by immunoblot with the HCD30C2 antiserum. Positions for CD30v protein and molecular weight markers are indicated on the far right and left of the figure, respectively.

Correlation between the Expression of CD30v and CD30L mRNAs in Malignant Cells of Myeloid and Lymphoid Origin

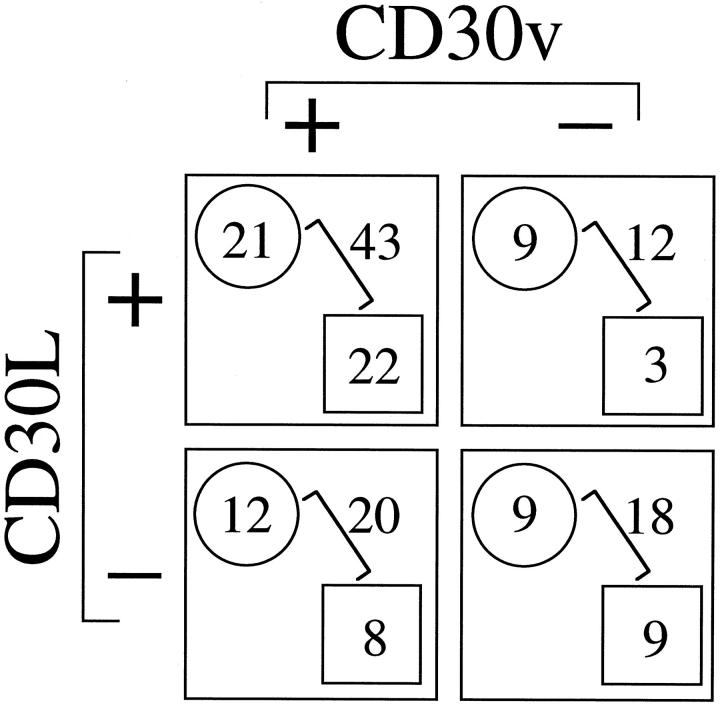

Based on the data we accumulated, CD30v was expressed frequently in malignant cells of myeloid and lymphoid origin. Because we earlier reported the frequent expression of CD30L in human hematopoietic malignancies, 10 it was of interest to analyze the parallel expression of CD30v and CD30L transcripts in tumor cells from 42 AMLs and 51 LPDs in our series. In agreement with earlier findings, 10 a high rate of CD30L-expressing cases was observed both in myeloid and lymphoid malignancies (Figure 5) ▶ , as opposed to CD30 mRNA that was detected only in 2 of 42 AML cases and 4 of 51 LPDs (not shown). A statistically significant correlation was found between the expression of CD30L mRNA and the presence on malignant cells of specific transcripts for CD30v. As shown in Figure 5 ▶ , χ 2 analysis performed by combining results of CD30v and CD30L expression in AMLs and LPDs revealed a P value of 0.02 and an odds ratio of 3.22, thus indicating a more than threefold higher possibility that CD30v-expressing cells coexpress CD30L, as compared to tumor cells lacking CD30v expression.

Figure 5.

Correlation between expressions of CD30v and CD30L. Expression of transcripts for CD30v and CD30L, as detected by RT-PCR in myeloid (square) and lymphoid (circle) hematopoietic malignancies was compared. Figures in squares or circles represent numbers of cases, within the whole group of myeloid (squares) or lymphoid (circles) hematopoietic malignancies, expressing a given combination of CD30v and CD30L mRNAs. Sums are reported as unframed figures for each combination of CD30v and CD30L mRNA expression. The χ 2 test used for these latter figures revealed a P value of 0.02 and an odds ratio of 3.22.

In Vivo Interaction of CD30v with TRAF2 and TRAF5 and Expression of Transcripts for TRAF Proteins in Leukemic Cells

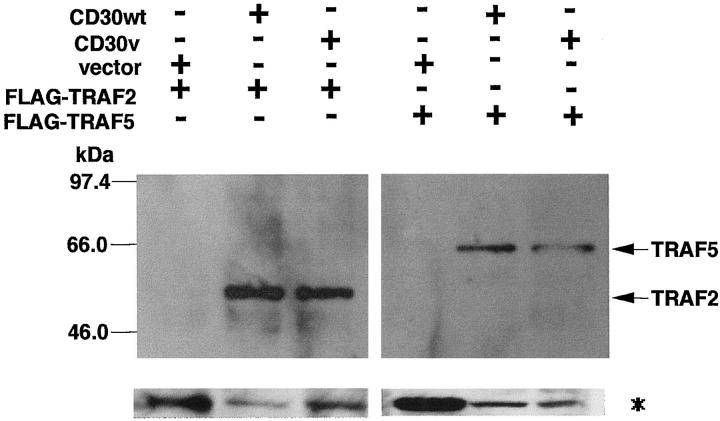

We reported that signals emanating from CD30 can activate NF-κB through interactions of TRAF2 and TRAF5 proteins with specific domains localized in the C-terminal region of CD30. 17,21 Because CD30v protein retains these TRAF-binding domains and can activate NF-κB, as the authentic CD30 protein, 22 interactions between CD30v and TRAF proteins were examined in coimmunoprecipitation experiments, using expression vectors for CD30v or CD30 and FLAG-tagged TRAF2 or TRAF5 proteins (Figure 6) ▶ . When the CD30v was expressed along with TRAF2 or TRAF5 in 293T cells, coimmunoprecipitation of CD30v with TRAF2 or TRAF5 was clearly demonstrated (Figure 6) ▶ , indicating in vivo interactions between CD30v and TRAF proteins. Because we observed that the cytoplasmic region of CD30 interacts with the corresponding CD30v (unpublished observation), these results suggest that aggregation of CD30v protein itself may result in NF-κB activation by recruiting TRAF proteins.

Figure 6.

In vivo association of CD30v protein with TRAF2 and TRAF5. Cell lysates of 293T cells transfected with expression vectors indicated above the figure were immunoprecipitated with HCD30C2 or anti-CD30 mAb Ber-H2, and immune complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (top). Positions of the FLAG-tagged TRAF2 and TRAF5 are indicated on the right, and those of molecular weight markers on the left. Expression of FLAG-tagged TRAF2 and TRAF5 was detected by M2 antibody, using whole cell lysates (*, bottom).

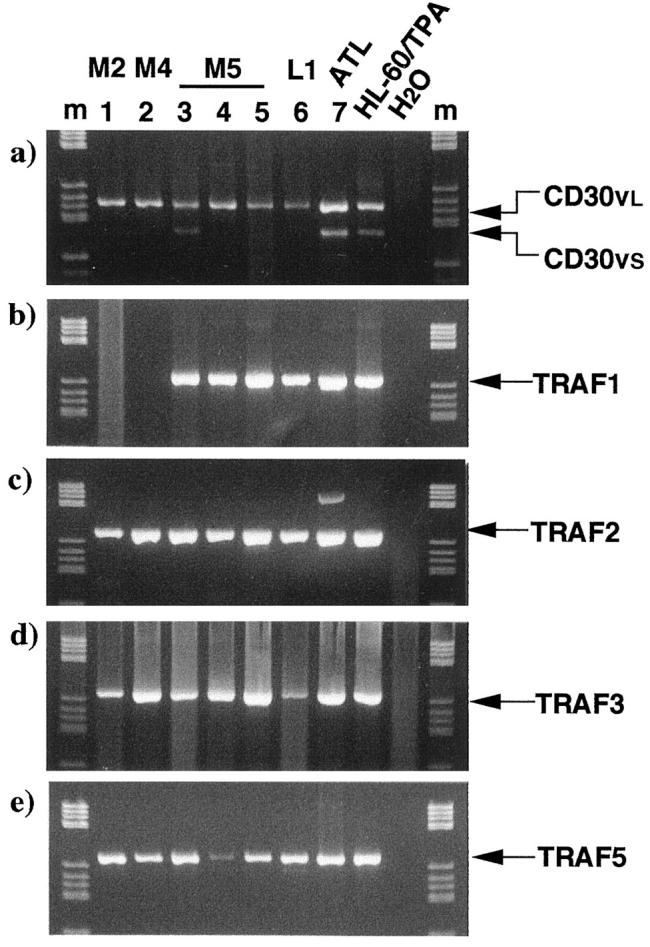

We then asked if interactions between CD30v and TRAF proteins can also occur in blast cells from leukemic samples, and for this purpose we surveyed the expression of transcripts for TRAF proteins in a series of CD30v-expressing samples, using RT-PCR with primer pairs for each TRAF protein that was confirmed to specifically amplify the cDNA templates, as described above. As shown in Figure 7 ▶ , blast cells from all seven cases analyzed expressed significant amounts of transcripts for TRAF1, TRAF2, TRAF3, and TRAF5 proteins, except for two cases lacking TRAF1 expression (Figure 7b) ▶ . Although the expression of transcripts specific for TRAF proteins was not exclusively confined to CD30v-positive cases (the expression was also found in CD30v-negative malignancies; data not shown), our present results do indicate that CD30v may interact in vivo with the NF-κB-activating proteins TRAF2 and TRAF5, the specific transcripts of which are significantly expressed in CD30v-expressing leukemic blasts.

Figure 7.

RT-PCR analysis of transcripts for TRAF1, 2, 3, and 5 in leukemic blasts. CD30v-expressing samples were used for the study. After 40 cycles of PCR in a 50-μl reaction volume, a 10-μl aliquot was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. Among the TRAF proteins, those reported to interact with CD30 were examined. The expected size for each PCR product is indicated on the right. a: CD30v; b: TRAF1; c: TRAF2; d: TRAF3; e: TRAF5; M2, M4, M5, FAB classification. ATL, adult T-cell leukemia; HL-60/TPA, TPA-treated HL-60; H2O, PCR without template cDNA; m, molecular weight marker.

Discussion

In our work, we identified a variant of CD30 (CD30v) that is induced by phorbol ester in HL-60 and is expressed in alveolar macrophages. 22 Screening of CD30v expression in other normal tissues, including bone marrow, failed to reveal this expression. 22 In the present study, we used a multiple approach, which included RT-PCR and Northern blotting, as well as immunoblotting and immunocytochemical detection of CD30v protein; a high rate of CD30v expression in malignant cells of myeloid and lymphoid origin was noted. In addition, a significantly correlated expression of CD30v and CD30L was evident. The evidence for interaction of TRAF2 and TRAF5 with CD30v in vivo and expression of transcripts for TRAF proteins provide support for the notion that CD30v may be involved in cellular growth and/or differentiation of leukemia cells, possibly by mediating NF-κB activating signals. Interestingly, such a frequent expression of CD30v seems to be exclusively confined to human malignant myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms, because a survey of CD30v expression in a wide panel of cell lines originating from extrahematopoietic tumors overall failed to detect specific CD30v transcripts (V. Gattei et al, unpublished observations). Screening of CD30v transcripts by RT-PCR in 83 myeloid and 120 lymphoid malignancies demonstrated a frequent expression of CD30v—71% and 58% in myeloid and lymphoid malignancies, respectively. In the myeloid series, we observed that CD30v is more frequently expressed in cases classified in FAB M4 and M5 than in those in M0, M1, and M2. Frequent and higher levels of CD30v expression in promyelocytic and monocyte-oriented leukemias are in accord with our earlier observations that CD30v is expressed in alveolar macrophages. 22 In the lymphoid series, B-lineage tumors showed a higher rate of CD30v expression than did T-lineage tumors (70% versus 23%), with almost 100% of CD30v-expressing cases found in B-CLL and multiple myeloma. It remains to be investigated whether CD30v expression is related to differentiation or transformation of B cells.

Detection of both CD30v transcripts and protein by combined analysis, using Northern blot and immunoblot analyses for cases positive by RT-PCR, provided further evidence for expression of CD30v in human malignant myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms. These results also provide strong support for the notion that results from RT-PCR represent expression of CD30v, at a significant level (Figure 4) ▶ .

We also noted the presence of the long (CD30vl) and short (CD30vs) forms of CD30v transcripts, which are probably generated by alternative splicing. 22 Both forms of CD30v transcripts were found in malignant cells of myeloid and lymphoid origin (Tables 1 and 2) ▶ ▶ . However, in 123 of 129 CD30v-expressing cases, CD30vl is expressed alone or in association with CD30vs, whereas CD30vs expression in the absence of CD30vl was found in only six cases (Tables 1 and 2) ▶ ▶ . Alternatively, CD30vs was detected in 60 of 129 CD30v-positive cases. It was not clear whether the lower detection rate of CD30vs is due to preferential expression of CD30vl, to lower levels of CD30vs transcripts, or to differences in the amplification efficiency in RT-PCR. The lower level of expression of the shorter transcripts is favored because the magnitude of amplification of the shorter transcripts was always lower than that of the larger one when both transcripts were detected.

An interesting correlation between expressions of CD30v and CD30L became evident in analyses of 42 AMLs and 51 LPDs (Figure 5) ▶ . Coexpression of these molecules may result from a common regulatory mechanism of transcription. Although the molecular mechanisms of transcriptional regulation have yet to be determined, CD30L expression in lymphocytic cell lines and peripheral blood monocytes and T cells may be induced by activating agents such as CD27 ligand, phorbol ester, and Staphylococcus aureus Cowan antigen. 35 The regulation of CD30v expression has yet to be characterized, and mechanisms explaining the coexpression between CD30v and CD30L remain to be determined. However, our data are of some interest because the simultaneous expression of CD30v and CD30L has been noted, in the absence of CD30, in normal peripheral blood T cells from patients affected by helminthic infections. 36 Moreover, the parallel up-regulation of CD30v- and CD30L-specific transcripts was also observed after in vitro activation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy donors by helminthic antigens. 36 Finally, high levels of constitutive CD30v and CD30L mRNA and protein were noted in normal peripheral blood neutrophils (Gattei et al, unpublished observation). 10 Interestingly, reverse signaling via CD30L was observed in freshly isolated neutrophils and T cells suboptimally stimulated by anti-CD3, leading to production of interleukin-8 and a rapid oxidative burst, or to an increased metabolic activity, proliferation, and production of interleukin-6, respectively. 11 It will be of interest to determine whether CD30v plays a role as a cytoplasmic signal transducer in processes of reverse signaling through CD30L, in these cell types, by interacting with the cytoplasmic N-terminus of CD30L. Experiments designed to test this possibility are now under way in our laboratory.

The rabbit antibody HCD30C2 raised against the N-terminal peptide of CD30v protein discriminated CD30v from the authentic CD30 in immunoblot analysis and immunoprecipitation. In addition, as shown in immunofluorescence studies, HCD30C2 reacted specifically with cytoplasmic antigens in TPA-stimulated HL-60 and COS-7 cells that express CD30v protein, indicating minimal or no reactivity of HCD30C2 with other antigens in the cells. Although the sequence of the antigen peptide of this antibody is shared by CD30v and CD30, this selective reactivity probably depends on the positive charge of the α-amino group in the N-terminus of the CD30v protein, which is the only difference compared with CD30. Similarly, antibodies that selectively recognize the forms of protein kinase C α have been developed with the use of peptide immunogens. 37,38

As observed in immunoblot experiments, HCD30C2 seems to recognize two closely migrating bands with an apparent molecular mass of about 25 kd. As previously suggested, 22 these two bands may be caused by an alternative translation initiation from two closely located ATG codons or may be the result of an unidentified posttranslational modification of the CD30v protein.

In addition to the CD30v protein, HCD30C2 also reacted nonspecifically with a band in immunoblot analysis. A similar but less evident nonspecific band was also observed in immunoprecipitation experiments. Pretreatment of the antibody with the immunogen resulted in a significant reduction in intensity of the band, suggesting that this protein has an epitope recognized by HCD30C2 (Figure 2B ▶ and data not shown). Notwithstanding these results, reactivity of HCD30C2 appeared specific in immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry, as mentioned above. These observations provide the basis for using HCD30C2 to detect CD30v expression in tissues.

The detection rate of CD30v expression in myeloid (10 of 25) and lymphoid (2 of 10) leukemia samples by immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence cytochemistry was lower than that in RT-PCR analyses (Table 3) ▶ ; the difference is probably the result of a lower sensitivity of immunological detection compared to that of RT-PCR, because it is more frequently detected in AML than in ALL. In most CD30v-expressing cases, CD30v-positive cells were noted among CD30v-negative blasts. It remains to be determined whether this finding actually reflects a smaller number of CD30v-expressing cells among CD30v-negative blasts or is the result of selective detection of highly expressing cells among many CD30v-expressing blasts. These possibilities can be defined by studies with a more sensitive method of immunohistochemistry and/or a sensitive detection of CD30v transcripts, using in situ hybridization. Studies of the function and regulation of the cryptic promoter for CD30v transcripts will also provide clues to how CD30v expression is regulated in leukemia cells.

Demonstration of interaction between CD30v and TRAF proteins and expression of transcripts for TRAF proteins provide the basis for assuming functional roles of CD30v in leukemia cells. We and other investigators found that NF-κB activation is mediated by interaction of TRAF2 and TRAF5 with the C-terminal region of the CD30 cytoplasmic domain, 15-20 which is retained in CD30v. Thus NF-κB activation by CD30v is likely to be mediated by interaction with these TRAF proteins.

Although NF-κB activation in CD30v-expressing leukemia cells, as compared with CD30v-negative ones, was not examined directly, the expression of TRAF-specific transcripts by malignant cells of CD30v-positive cases strongly favors the view that a CD30v-mediated NF-κB activation in CD30v-positive cells may play a role in the growth and/or differentiation of these cells.

In summary, we demonstrated the frequent expression of CD30v as well as transcripts for CD30v-associated signal transducer proteins in leukemic blasts, a finding that suggests roles for CD30v in growth and/or differentiation of these cells. Further studies of the mechanism underlying selective activation of the cryptic promoter for CD30v and direct examination of NF-κB activation in CD30v-positive cells are expected to provide insight into the biological effects caused by CD30v protein in CD30v-positive cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Ohara for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. T. Watanabe, Department of Pathology, Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo, 4-6-1 Shirokanedai, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8639, Japan. E-mail: tnabe@ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Supported in part by a Grant in Aid for Scientific Research and a Grant in Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan (to T. W.); the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (to R. H.); and grants from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (A.I.R.C.), Milan, Italy; the Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie (A.I.L.) “Trenta ore per la vita,” Italy; and the Ministero della Sanità, Ricerca Finalizzata I.R.C.C.S., Rome, Italy.

R. H. and V. G. contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Falini B, Pileri S, Pizzolo G, Dürkop H, Flenghi L, Stirpe F, Martelli MF, Stein H: CD30 (Ki-1) molecule: a new cytokine receptor of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily as a tool for diagnosis and immunotherapy. Blood 1995, 85:1-14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dürkop H, Latza U, Hummel M, Eitelbach F, Seed B, Stein H: Molecular cloning and expression of a new member of the nerve growth factor receptor family that is characteristic for Hodgkin’s disease. Cell 1992, 68:421-427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith CA, Farrah T, Goodwin RG: The TNF receptor superfamily of cellular and viral proteins: activation, costimulation, and death. Cell 1994, 76:959-962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazzoni F, Beutler B: The tumor necrosis factor ligand and receptor families. N Engl J Med 1996, 334:1717-1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith CA, Grüss HJ, Davis T, Anderson D, Farrah T, Baker E, Southerland GR, Branann CI, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Grabstein KH, Gliniak B, McAlister IB, Fanslow W, Alderson M, Falk B, Gimpel S, Gillis S, Din WS, Goodwin RG, Armitage RJ: CD30 antigen, a marker for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, is a receptor whose ligand defines an emerging family of cytokines with homology to TNF. Cell 1993, 73:1349-1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruss HJ, Boiani N, Williams DE, Armitage RJ, Smith CA, Goodwin RG: Pleiotropic effects of the CD30 ligand on CD30-expressing cells and lymphoma cell lines. Blood 1994, 83:2045-2056 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horie R, Watanabe T: CD30: expression and function in health and disease. Semin Immunol 1998, 10:457-470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Younes A, Consoli U, Zhao S, Snell V, Thomas E, Gruss HJ, Cabanillas F, Andreeff M: CD30 ligand is expressed on resting normal and malignant B lymphocytes. Br J Haematol 1996, 93:569-571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto A, Aldinucci D, Gloghini A, Zagonel V, Degan M, Importa S, Juzbasic S, Todesco M, Perin V, Gattei V, Hermann F, Gruss HJ, Carbone A: Human eosinophils express functional CD30 ligand and stimulate proliferation of a Hodgkin’s disease cell line. Blood 1996, 88:3299-3305 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gattei V, Degan M, Gloghini A, De Iuliis A, Improta S, Rossi FM, Aldinucci D, Perin V, Serraino D, Babare R, Zagonel V, Gruss HJ, Carbone A, Pinto A: CD30 ligand is frequently expressed in human hematopoietic malignancies of myeloid and lymphoid origin. Blood 1997, 89:2048-2059 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiley SR, Goodwin RG, Smith CA: Reverse signaling via CD30 ligand. J Immunol 1996, 157:3635-3639 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis TM, Simms PE, Slivnick DJ, Jäck H-M, Fisher RI: CD30 is a signal-transducing molecule that defines a subset of human activated CD45RO+ T cells. J Immunol 1993, 151:2380-2389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biswas P, Smith CA, Goletti D, Hardy EC, Jackson RW, Fauci AS: Cross-linking of CD30 induces HIV expression in chronically infected T cells. Immunity 1995, 2:587-596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maggi E, Annunziato F, Manetti R, Biagiotti R, Giudizi MG, Ravina A, Almerigogna F, Boiani N, Alderson M, Romagniani S: Activation of HIV expression by CD30 triggering in CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected individuals. Immunity 1995, 3:251-255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishida T, Tojo T, Aoki T, Kobayashi N, Oishi T, Watanabe T, Yamamoto T, Inoue J: TRAF5, a novel tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor family protein, mediates CD40 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:9437-9442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakano H, Oshima H, Chung W, Williams-Abott L, Ware CF, Yagita H, Okumura K: TRAF5, an activator of NF-kappaB, and putative signal transducer for the lymphotoxin-β receptor. J Biol Chem 1996, 271:14661-14661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aizawa S, Nakano H, Ishida T, Horie R, Nagai M, Ito K, Yagita H, Okumura K, Inoue J, Watanabe T: Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 5 and TRAF2 are involved in CD30-mediated NF-kB activation. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:2042-2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SY, Lee SY, Kandala G, Liou M-L, Choi Y: CD30/TNF receptor-associated factor interaction: NF-kappa B activation and binding specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:9699-9703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gedrich RW, Gilfillan MC, Ducket CS, Van Dongen JL, Thompson CB: CD30 contains two binding sites with different specificities for members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor family of signal transducing proteins. J Biol Chem 1996, 271:12852-12858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boucher L-M, Marengere LEM, Lu Y, Thurkral S, Mak TM: Binding sites of cytoplasmic effectors TRAF1, 2, and 3 on CD30 and other members of the TNF receptor superfamily. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997, 233:592-600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horie R, Aizawa S, Nagai M, Ito K, Higashihara M, Ishida T, Inoue J, Watanabe T: A novel domain in the CD30 cytoplasmic tail mediates NF-κB activation. Int Immunol 1998, 10:203-210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horie R, Ito K, Tatewaki M, Nagai M, Aizawa S, Higashihara M, Ishida T, Inoue J, Takizawa H, Watanabe T: A variant CD30 protein lacking extracellular and transmembrane domains is induced in HL-60 by tetradecanoylphorbol acetate and is expressed in alveolar macrophages. Blood 1996, 88:2422-2432 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothe G, Schmitz G, : Working Group on Flow Cytometry and Image Analysis: Consensus protocol for the flow cytometry immunophenotyping of hematopoietic malignancies. Leukemia 1996, 10:877-895 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.: The Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Pathologic Classification Project: National Cancer Institute sponsored study of classifications of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Summary and description of a working formulation for clinical usage. Cancer 1982, 42:2112-2135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, Banks PM, Chan JKC, Cleary ML, Delsol G, De Wolf-Peters C, Falini B, Gatter KC, Grogan TM, Isaacson PG, Knowles DM, Mason DY, Muller-Hemerlink HK, Pileri S, Piris MA, Ralfkiaer E, Warnke RA: A revised European American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 1994, 84:1361-1392 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Zaanen HC, Vet RJ, de Jong CM, von dem Borne AE, van Oers MH: A simple and sensitive method for determining plasma cell isotype and monoclonality in bone marrow using flow cytometry. Br J Haematol 1995, 91:55-59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chomczynsky P, Sacchi N: Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 1987, 162:156-159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosialos G, Birkenbach M, Yalamanchili R, van Arsdale T, Ware C, Kief E: The Epstein-Barr virus transforming protein LMP1 engages signaling proteins for the tumor necrosis factor receptor family. Cell 1995, 80:389-399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng G, Cleary AM, Ye ZS, Hong DI, Lederman S, Baltimore D: Involvement of CRAF1, a relative of TRAF, in CD40 signaling. Science 1995, 267:1494-1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizushima S, Fujita M, Ishida T, Azuma S, Kato K, Hirai M, Otsuka M, Yamamoto T, Inoue J: Cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding human homolog of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 5. Gene 1998, 207:135-140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ponte P, Ng SY, Engel J, Gunning P, Kedes L: Evolutionary conservation in untranslated regions of actin mRNAs: DNA sequence of a human β-actin cDNA. Nucleic Acids Res 1984, 12:1687-1696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuroda M, Ishida T, Takanashi M, Satoh M, Machinami R, Watanabe T: Oncogenic transformation and inhibition of adipocytic conversion of preadipocytes by TLS/FUS-CHOP type II chimeric protein. Am J Pathol 1997, 151:735-744 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armitage P, Berry G: Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1987. Blackwell Scientific, London

- 34.Sonenberg N: mRNA translation: influence of the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1994, 4:310-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gruss HJ, DaSilva N, Hu ZB, Uphoff CC, Goodwin RG, Drexler HG: Expression and regulation of CD30 ligand and CD30 in human leukemia-lymphoma cell lines. Leukemia 1994, 8:2083-2094 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kilwinski J, Berger T, Mpalaskas J, Reuter S, Flick W, Kern P: Expression of CD30 mRNA, CD30L mRNA and a variant form of CD30 mRNA in restimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of patients with helminthic infections resembling a Th2 disease. Clin Exp Immunol 1999, 115:114-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kikuchi H, Imajo-Ohmi S: Antibodies specific for proteolyzed forms of protein kinase Cα. Biochim Biophys Acta 1995, 1269:253-259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kikuchi H, Imajo-Ohmi S: Activation and possible involvement of calpain, a calcium-activated cysteine protease, in down-regulation of apoptosis of human monoblast U937 cells. Cell Death Differ 1995, 2:195-199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]