Abstract

The mechanism of neovascularization secondary to renal interstitial fibrosis is not well understood. Platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor (PD-ECGF) is known to promote angiogenesis. We examined the expression of PD-ECGF immunohistochemically in 9 normal kidneys and 26 scarred kidneys secondary to urinary tract diseases. To estimate up-regulation of angiogenesis, microvessels were counted by immunostaining endothelial cells for CD34. Immunostaining of PD-ECGF was observed in most Bowman’s capsules, occasional tubules, and some interstitial mononuclear cells in normal kidneys. A remarkable increase of immunostained PD-ECGF was found in the tubules and interstitial mononuclear infiltrates in the scarred kidneys. The predominant cell type in the infiltrate was T cells (CD3+). The microvessel count and mean numbers of PD-ECGF+ tubular and interstitial mononuclear cells increased with increasing interstitial fibrosis. A significant correlation was noted between microvessel count and the number of PD-ECGF+ tubular cells (P = 0.0002) or PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells (P < 0.0001). Immunostaining of endogrin, a marker of endothelial proliferation, increased in the microvessels located in the fibrotic interstitial spaces. These results suggest that angiogenesis may play a critical role in the progression of tubulointerstitial injuries and that up-regulation of PD-ECGF may contribute to neovascularization.

The degree of tubulointerstitial pathology characterized by tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and mononuclear cell infiltration correlates most closely with declining renal function in various renal diseases including classical glomerular diseases. 1-3 The increase of interstitial volume leads to obliteration of the postglomerular peritubular capillary network 4 and consequently induces tubular hypoxia and injury. 5 Previous studies have shown that hypoxia promotes angiogenesis by inducing up-regulation of growth factors and cytokines including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor , and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). 6-11 On one hand, injured tubular cells have been shown to release a variety of growth factors and cytokines that promote peritubular inflammation, scar formation, and possibly vascular formation. 3,12,13 On the other hand, leukocyte recruitment has been shown to precede the formation of new blood vessels, which occurs in a variety of inflammatory processes including wound repair and rheumatoid arthritis. 7,14,15 Mononuclear infiltration has been observed in scarred kidneys secondary to urinary tract diseases. The predominant cell type is T cells, followed by macrophages. 16,17 These cells may promote angiogenesis by releasing angiogenic factors including VEGF, TNF-α, basic fibroblast growth factor, and platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor (PD-ECGF). 14,18-24 The presence of a hypoxic condition and the increase of mononuclear infiltration in scarred kidneys have been suggested to lead to neovascularization. However, the role of angiogenesis in the exacerbation of tubulointerstitial injury remains uncertain.

PD-ECGF is an endothelial cell mitogen originally purified to homogeneity from human platelets. 25 This protein stimulates chemotaxis of endothelial cells in vitro and exhibits an angiogenic activity in vivo. 25 PD-ECGF does not have a signal sequence, 25 and thus it might not be a secretory protein. PD-ECGF is suggested to be important in pathological, but not physiological, angiogenesis. 23 Recently this protein has been shown to be identical to thymidine phosphorylase (TP). 26,27 TP catalyzes the reversible phospholysis of thymidine to 2-deoxy-d-ribose-1-phosphate and thymine. Furthermore, 2-deoxy-d-ribose derived from 2-deoxy-d-ribose-1-phosphate has chemotactic and angiogenic activities. 27 Thymine is metabolized to dihydrothymine, which in turn is converted to β-amino-iso-butyric acid. 28 β-Amino-iso-butyric acid stimulates microvessel formation and elongation in vitro. The enzyme activity appears to be essential for the angiogenic action of PD-ECGF, which may be mediated through readily diffusible metabolites. 27,28 PD-ECGF is important in the progression of human cancers, and its expression is associated with vessel count. 18,24,29-31 Immunostained PD-ECGF has been observed in fibroblasts, macrophages, differentiated lymphocytes, and renal tubules. 22-24

Renal scarring secondary to a variety of urinary tract diseases, such as reflux nephropathy and obstructive nephropathy, is characterized by primary tubulointerstitial pathology with subsequent involvement of the glomerular structure. 12,32,33 This type of renal disease is thought to progress via the formation of atubular glomeruli that have open capillaries but are not connected to normal proximal tubules. 32 We previously demonstrated increases in renin-containing cells in the afferent arterioles and juxtaglomerular apparatus of glomeruli, including atubular ones, located in the fibrotic areas of the scarred kidneys. 34 This indicates that the renin-angiotensin system may be activated in the scarred kidneys. Angiotensin II promotes the accumulation of extracellular matrix and mononuclear infiltrates in the interstitial spaces. 35 This protein also stimulates the production of growth factors and cytokines including angiogenic molecules. 36,37 Scarred kidneys secondary to urinary tract diseases are an appropriate model with which to evaluate the up-regulation of angiogenesis in the interstitial spaces. In this study, we sought to clarify the mechanism of increased formation of new vessels and its contribution to the progression of tubulointerstitial injury in the scarred kidneys and to evaluate the potential role of PD-ECGF in angiogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Samples

Twenty-six renal specimens were obtained from 5 males and 21 females aged 3 to 32 years (average, 12.5 years) who underwent nephrectomy (20 cases) or heminephrectomy (6 cases) due to renal scarring resulting from urinary tract diseases. Severe renal scarring with little function was confirmed by 99 mTc-dimercaptosuccinic acid renal scan, computed tomography (CT), and ultrasonography. The underlying urinary tract diseases were ectopic ureter in 12 cases, vesico-ureteral reflux in 6, ureteropelvic junction stenosis in 6, and ectopic ureterocele in 2. Complete duplication of the ureter was confirmed by a percutaneous antegrade pyelogram in six cases, including ectopic ureter in three cases, ectopic ureterocele in one, vesicoureteral reflux in one, and ureteropelvic junction stenosis draining the upper kidney segment in one. The contralateral kidneys were normal in all cases on CT and 99 mTc-dimercaptosuccinic acid renal scan, and levels of serum creatinine and β2-microglobulin were also within normal ranges. Urinalysis in all patients revealed no proteinuria. The control group consisted of five males and four females aged 5 to 35 years (average, 14.8 years). Sections of normal renal tissues were obtained from five renal biopsy specimens showing minimal changes and five kidneys resected owing to localized tumors.

All tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 3-μm sections. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, and azan-Mallory’ triple stain for routine histological examination.

Degree of Interstitial Fibrosis

The degree of interstitial fibrosis was assessed histologically by using azan Mallory’ triple stain sections. Two authors (KS, HS) who were blinded to the immunohistochemical results assessed the sections together by using a double-headed light microscope. Tubulointerstitial changes were graded on an arbitrary scale as follows: grade 1, slight increase in interstitial fibrosis with almost normal tubules and mononuclear infiltrates localized in fibrotic areas; grade 2, an increase in interstitial fibrosis and atrophic tubules with marked interstitial mononuclear infiltrates; and grade 3, a mostly fibrotic cortex with atrophic tubules and intensive interstitial mononuclear infiltrates. In grade 3 fibrosis, mononuclear infiltration was sometimes so intense that germinal centers were observed.

The glomeruli were in general well preserved in grades 1 and 2 fibrosis, although periglomerular fibrosis was occasionally observed in grade 2. The glomeruli in grade 3 fibrosis were mostly obsolescent and were rarely associated with patent capillary loops.

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse anti-human PD-ECGF/TP monoclonal antibody (clone 654–1) was supplied by Nippon Roche (Kamakura, Japan). 31,38 This antibody was produced by immunizing mice with PD-ECGF/TP purified from HCT116 human colon cancer xenografts as previously described. 38 Specificity of the antibody to PD-ECGF/TP was confirmed by using HCT116 colon cancer xenograft and human cancer tissues. 38 In Western blot analyses with extracts of the HCT116 colon cancer xenograft and human cancer tissues, monoclonal antibody 654–1 (1 μg/ml) reacted only with the protein with a molecular mass of 55 kd, which corresponds to PD-ECGF/TP. Mouse anti-human CD34 monoclonal antibody (clone NU-4A1; Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) was used for immunohistochemical detection of vascular endothelial cells. Mouse anti-human endogrin (CD105) monoclonal antibody (clone SN6h; Dako Japan, Kyoto, Japan) was used to detect endogrin, which is a marker of endothelial cell proliferation. 39 Recent studies have indicated that up-regulation of endogrin on vascular endothelial cells in solid tumor and chronic inflammatory disorders is involved in the regulation of angiogenesis in these pathological conditions. 40 Mouse monoclonal antibody to human leukocyte common antigen (CD45; clone 2B11 + PD7/26; Dako Japan) was used to differentiate infiltrating mononuclear cells from other interstitial cells. Mononuclear cell infiltrates were differentiated into T cells, macrophages, and B cells by rabbit polyclonal antibodies against human CD3 (Dako Japan), which is a marker for pan T cells, human CD68 (clone PG-M1: Dako Japan), which is a marker for macrophage, and human CD20/cy (clone L26: Dako Japan), which is a marker for pan B cells.

Immunostaining was performed on serial sections. Three-micron sections from paraffin-embedded specimens were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded ethanol, and placed in 100% methanol with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Because CD3, CD68, and endogrin antibodies gave no or weak reactions with formalin-fixed and wax-embedded sections, the sections were trypsin-predigested for 30 minutes at 37°C. The slides were then incubated for 10 minutes in phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4, containing 10% normal goat serum at room temperature in a moist chamber. The primary antibodies were incubated with the tissue sections overnight at 4°C. Optimal dilutions of the primary antibodies were 1:200 for PD-ECGF, 1:200 for CD3, and 1:10 for endogrin. Primary antibodies for CD34, CD45, CD68, and CD20/cy were provided already diluted to the appropriate concentrations for immunohistochemistry. After washing with 0.05 mol/L Tris-hydrochloric acid buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20, the sections were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Envision+, Dako Japan) for 40 minutes at room temperature. The sections were again washed with 0.05 mol/L Tris-hydrochloric acid buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20, and antigen-antibody complexes were visualized by immersion in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine solution (0.01 mol/L 3,3′-diaminobenzidine, 0.05 mol/L Tris-hydrochloric acid buffer, pH 7.6, 0.01 mol/L sodium azide, 0.006% hydrogen peroxide). Sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin alone or hematoxylin and eosin. Negative control slides stained with normal mouse IgG instead of primary antibodies showed no immunoreactivity.

Tissue sections were double-immunostained for CD34 and PD-ECGF. Sections were first stained with mouse anti-human PD-ECGF monoclonal antibody for 60 minutes at room temperature followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Envision+, Dako Japan) and diaminobenzidine chromogen (brown deposit). After washing twice with 0.1 mol/L glycine-hydrochloric acid buffer, pH 2.2, for 30 minutes to remove the PD-ECGF antibody, sections were incubated with mouse anti-human CD34 monoclonal antibody overnight at 4°C followed by Envision+ and HistoMark Black (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD) as color reagent (black deposit).

Counting of Microvessels, PD-ECGF+ Cells, and T Cells

To estimate the numbers of microvessels, PD-ECGF+ tubular cells, PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells, and T cells, we captured the images of immunostained sections (×20 objective) on a computer by using a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (ProgRes 3012, Kontron Electric, Eching, Germany) attached to an operating light microscope (Axioplan 2, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany), together with a Power Macintosh 9500/120 (Apple Computer, Cupertino, CA) and Adobe Photoshop 3.0J software (Apple Computer). The captured images were printed on A4 paper by using a color printer (Photo-Machjet PM-750C, Epson, Tokyo, Japan). Counting was performed by two authors (RK, MS) using the printed images. They counted 63 prints with grade 1 fibrosis, 48 with grade 2, 41 with grade 3, and 30 prints of normal kidneys. Serial sections were used so that countings were made in the same area in which fibrosis was graded. The numbers of microvessels, PD-ECGF+ tubular cells, PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells, and T cells were assessed. Results are presented as number of microvessels or cells per unit of area of the captured image.

When glomeruli or large vessels were present in the captured image, the areas of these structures were subtracted from the total area of the image. When interobserver differences of >5% were found, the case was re-evaluated by the two authors. The mean values were calculated only in those cases with interobserver differences of <5%.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± SE. Correlations between microvessel count and the numbers of PD-ECGF+ tubular cells, interstitial mononuclear cells, and T cells were examined by Spearman test and simple regression analysis. The differences in the numbers of microvessels, PD-ECGF+ tubular cells, PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells, and T cells between the control and each fibrosis grade were analyzed by Kruscal-Wallis test by ranks, and pairwise comparisons were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were done with StatView for Macintosh (Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA).

Results

CD34+ Microvessels in Normal and Scarred Kidneys

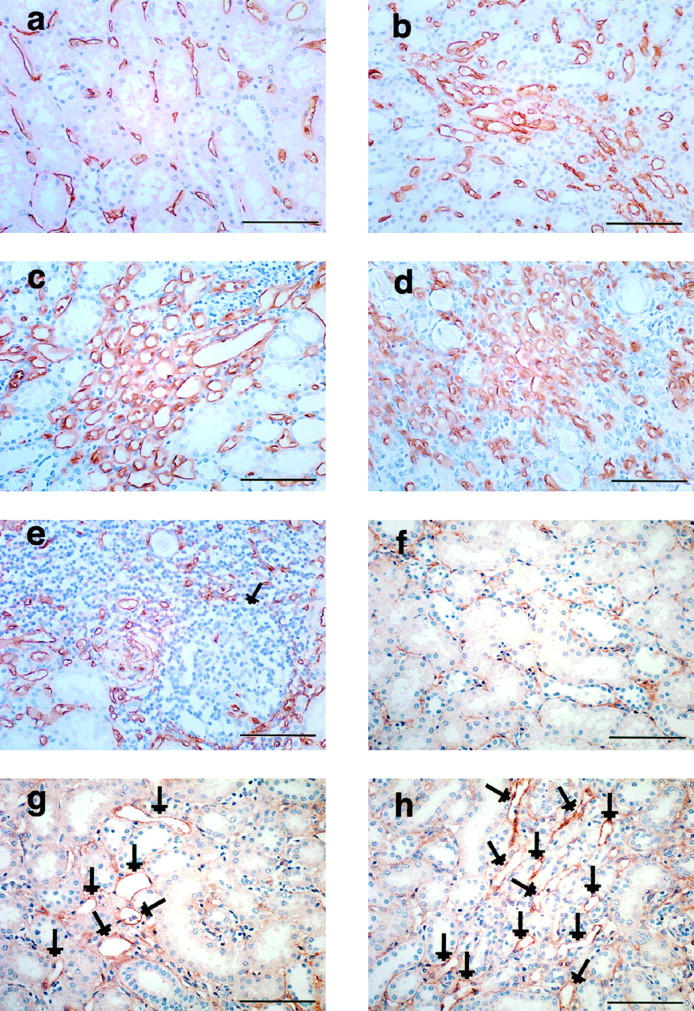

The number of CD34+ microvessels increased remarkably in the fibrotic areas of scarred kidneys compared with normal kidneys (Figure 1, a ▶ -d). However, only a few microvessels were present in intensely scarred areas with grade 3 fibrosis, where tubules and glomeruli were mostly replaced by fibrotic tissues and mononuclear infiltrates (Figure 1e) ▶ . In these areas, we often found germinal centers containing few microvessels. Interstitial fibrosis was distributed heterogeneously in both the cortex and medulla, but predominantly in the medulla. There was no notable difference in microvessel density in the fibrotic areas in the cortex compared with that in the medulla (results not shown). Endogrin, a endothelial cell proliferation marker, was strongly expressed in the microvessels in fibrotic areas containing a high density of microvessels (Figure 1h) ▶ . This protein was also expressed strongly in some microvessels in mildly fibrotic areas with no increase of microvessel density (Figure 1g) ▶ . Weak or no staining was observed in the microvessels in the interstitial space of normal kidneys or in the nonfibrotic areas of scarred kidneys (Figure 1f) ▶ .

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of CD34 (a-e) and endogrin (f-h) in normal and scarred kidneys. a: Interstitial microvessels (brown color deposit) in normal kidney. b and c: Microvessel density increases in the interstitial space with grades 1 (b) and 2 (c) fibrosis. d and e: Interstitial space with grade 3 fibrosis is occupied by many microvessels (d), but only a few microvessels are present in the intensely fibrotic area-containing germinal center (e, arrow). f: Only weak staining of endogrin is observed in the microvessels in the interstitial space of normal kidney. g: In contrast, strong staining of endogrin (arrows) is seen in some vessels in areas of grade 1 fibrosis without hypervascularity. h: Marked increase of endogrin staining (arrows) in up-regulated microvessels in interstitial space with grade 2 fibrosis. Scale bar, 100 μm.

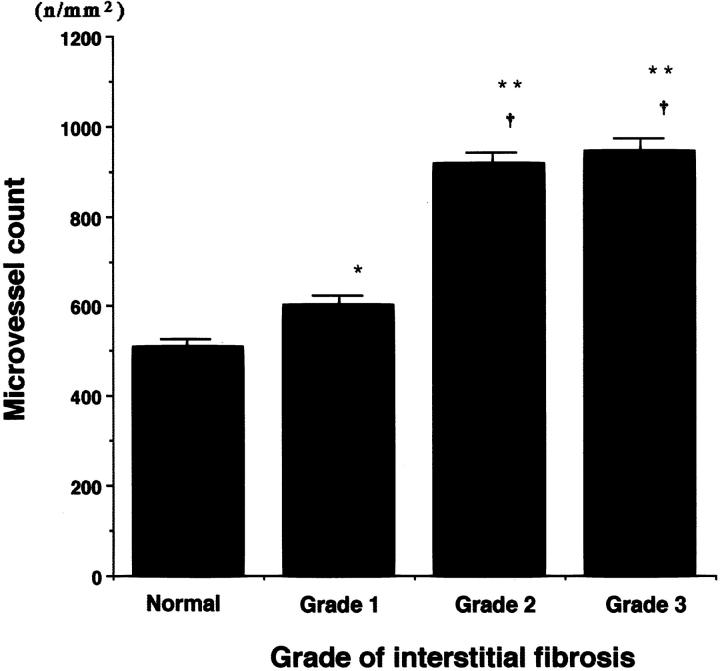

The mean microvessel counts (± SE) were significantly increased in scarred kidneys with grade 1 (601.7 ± 21.8), grade 2 (916.8 ± 24.99), and grade 3 fibrosis (942.9 ± 31.66) compared with normal kidneys (508.7 ± 15.93) (P < 0.05, P < 0.0001, and P < 0.0001, respectively) (Figure 2) ▶ . Significant differences were observed between grade 1 fibrosis and grade 2 (P < 0.0001) or grade 3 fibrosis (P < 0.0001), but no significant difference was found between grade 2 and grade 3 (P > 0.5).

Figure 2.

Microvessel count in normal and scarred kidneys. The numbers of interstitial microvessels were counted morphometrically by using CD34-immunostained sections. All data are presented as mean ± SE (number of microvessels or cells per total area of the captured image (n/mm2)). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.0001 versus normal kidneys; †P < 0.0001 versus grade 1.

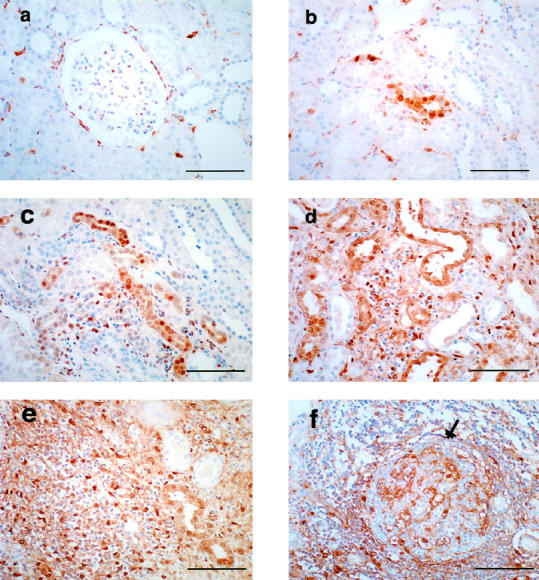

Immunohistochemical Staining for PD-ECGF

In normal kidneys, PD-ECGF immunostaining was detected in the Bowman’s capsules in most glomeruli, in occasional tubules, and in some interstitial mononuclear cells (Figure 3, a and b) ▶ . Remarkable increases of PD-ECGF+ tubular cells and interstitial mononuclear cells were noted in the fibrotic areas of scarred kidneys (Figure 3, c ▶ -e). However, PD-ECGF staining was reduced in intensely scarred areas with grade 3 fibrosis (Figure 3f) ▶ . As mentioned above, germinal centers were often observed in these areas which contained only a few PD-ECGF+ mononuclear cells. We observed strong immunostaining of PD-ECGF in some tubular cells in grade 1 fibrosis, in which microvessel density and PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells were not increased (Figure 1c) ▶ . Immunostaining of PD-ECGF was observed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus as previously reported. 22

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of PD-ECGF in normal (a and b) and scarred kidneys (c-f). a and b: Immunostaining of PD-ECGF (brown deposit) is observed in Bowman’s capsule (a), tubular cells (b), and interstitial mononuclear cells (a and b) of normal kidneys. c-e: Immunostaining of PD-ECGF in grade 1 (c), grade 2 (d), and grade 3 (e) fibrosis. An increase of PD-ECGF immunostaining is observed in tubular cells and interstitial mononuclear cells in fibrotic areas (e). f: Immunostaining of PD-ECGF decreases notably in intensely fibrotic area-containing germinal center (arrow). Scale bar, 100 μm.

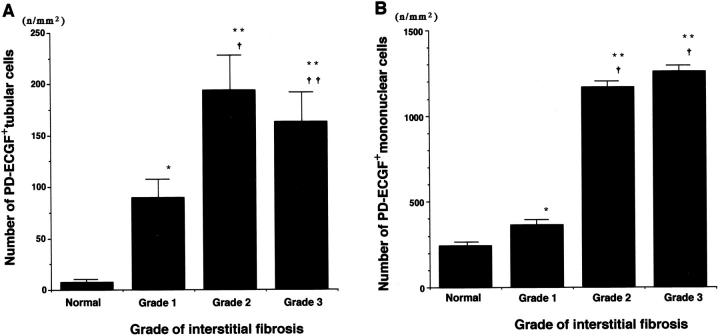

The mean numbers of PD-ECGF+ tubular cells were significantly increased in scarred kidneys with grade 1 (89.1 ± 20.94), grade 2 (193.7 ± 35.37), and grade 3 fibrosis (162.8 ± 28.07), compared with normal kidneys (6.9 ± 3.95) (P < 0.005, P < 0.0001, and P < 0.0001, respectively; Figure 4A ▶ ). Significant increases were noted in grade 2 or grade 3 fibrosis compared with grade 1 (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0002, respectively), but no significant difference was found between grade 2 and grade 3 (P > 0.5).

Figure 4.

Numbers of PD-ECGF+ tubular cells (A) and interstitial mononuclear cells (B) in normal and scarred kidneys. The numbers of PD-ECGF+ tubular cells and interstitial mononuclear cells were measured morphometrically, using PD-ECGF immunostained sections. All data are presented as mean ± SE (number of microvessels or cells per total area of the captured image (n/mm2)). A: *P < 0.005; **P < 0.0001 versus normal kidneys; †P < 0.0001; ††P = 0.0002 versus grade 1. B: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.0001 versus normal kidneys; †P < 0.0001 versus grade 1.

The mean numbers of PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells were significantly increased in scarred kidneys with grade 1 (363.9 ± 27.82), grade 2 (1167.3 ± 69.98), and grade 3 fibrosis (1258.4 ± 51.02), compared with normal kidneys (243.8 ± 19.21) (P < 0.05, P < 0.0001, and P < 0.0001, respectively) (Figure 4B) ▶ . Significant increases were noted in grade 2 or grade 3 fibrosis compared with grade 1 (P < 0.0001 and P < 0.0001, respectively), but no significant difference was observed between grade 2 and grade 3 (P > 0.1).

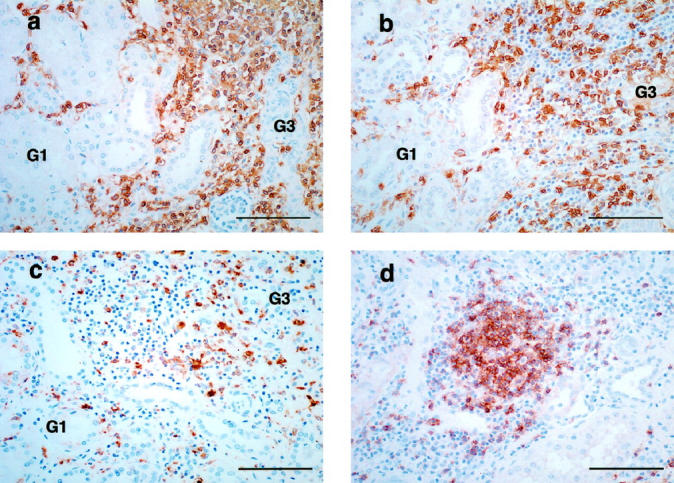

Interstitial Leukocyte Infiltration

A significant increase in interstitial CD45+ leukocytes was seen in scarred kidneys (Figure 5a) ▶ . The predominant cell type was T cells (CD3+) (Figure 5b) ▶ . These cells were observed in the interstitial spaces not only in fibrotic areas but also in nonfibrotic areas of scarred kidneys. Macrophages (CD68+) accumulated in the interstitial spaces in scarred kidneys, but they were less populous than T cells (Figure 5c) ▶ . Although B cells (CD20/cy+) also infiltrated the interstitial space in scarred kidneys, these cells accumulated predominantly in and around germinal centers (Figure 5d) ▶ .

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical staining of CD45 (a), CD3 (b), CD68 (c), and CD20/cy (d). a: Interstitial spaces with grade 3 fibrosis (G3) are mostly occupied by CD45+ leukocytes. Leukocytes also infiltrate the interstitial space with grade 1 fibrosis (G1). b: The predominant cell type infiltrating the interstitial space in scarred kidneys is T cells (CD3+). These cells are present not only in severely fibrotic areas (G3) but also in the less fibrotic areas (G1). c: Macrophages (CD68+) accumulate in the interstitial spaces of the scarred kidneys, but are less populous than T cells. d: B cells (CD20/cy+) infiltrate in the scarred kidneys, but these cells mainly accumulate in and around the germinal center. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Macrophages, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts are the possible sources of PD-ECGF in the interstitial space. Fibroblasts may not be the dominant source in scarred kidneys because fibrotic areas were mostly occupied by infiltrating leukocytes (Figure 5a) ▶ . Immunohistochemical staining of PD-ECGF, CD3, and CD68 by using serial sections demonstrated that T cells (CD3+) were the main PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells in the scarred kidneys (Figure 6) ▶ . Because T cells were the predominant cells infiltrating in scarred kidneys and are the most probable candidate as a source of PD-ECGF in the mononuclear infiltrates, we compared the numbers of interstitial T cells in normal and scarred kidneys with different grades of fibrosis.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemical staining of PD-ECGF (a), CD3 (b), and CD68 (c), using serial sections. Intense immunostaining of PD-ECGF was found in the tubules and the interstitial mononuclear cells in the fibrotic areas (a). Immunostaining of serial sections with CD3 (b) and CD68 (c) indicated that most of the PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells were CD3-positive (T cells). Scale bar, 100 μm.

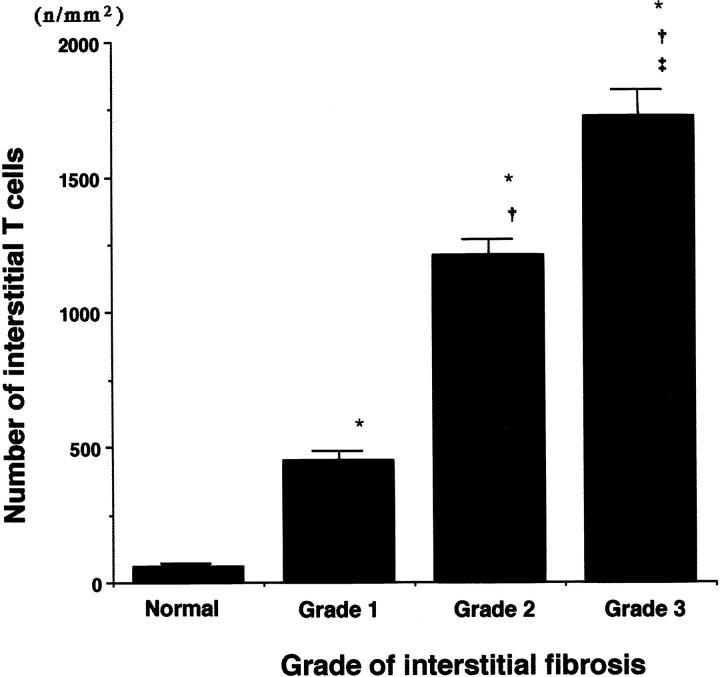

The mean T cell counts in the interstitial space were significantly higher in scarred kidneys with grade 1 (452.2 ± 36.73), grade 2 (1211.7 ± 83.05), and grade 3 fibrosis (1723.9 ± 120.22), compared with normal kidneys (58.3 ± 6.13) (P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001, and P < 0.0001, respectively) (Figure 7) ▶ . A significant increase was observed in grade 2 fibrosis compared with grade 1 (P < 0.0001) and in grade 3 compared with grade 1 or 2 (P < 0.0001, P = 0.0005, respectively).

Figure 7.

Numbers of T cells in interstitial spaces in normal and scarred kidneys. The number of T cells was measured morphometrically by using CD3-immunostained sections. All data are presented as mean ± SE (number of microvessels or cells per total area of the captured image (n/mm2)). *P < 0.0001 versus normal kidneys; †P < 0.0001 versus grade 1; ‡P = 0.0005 versus grade 2.

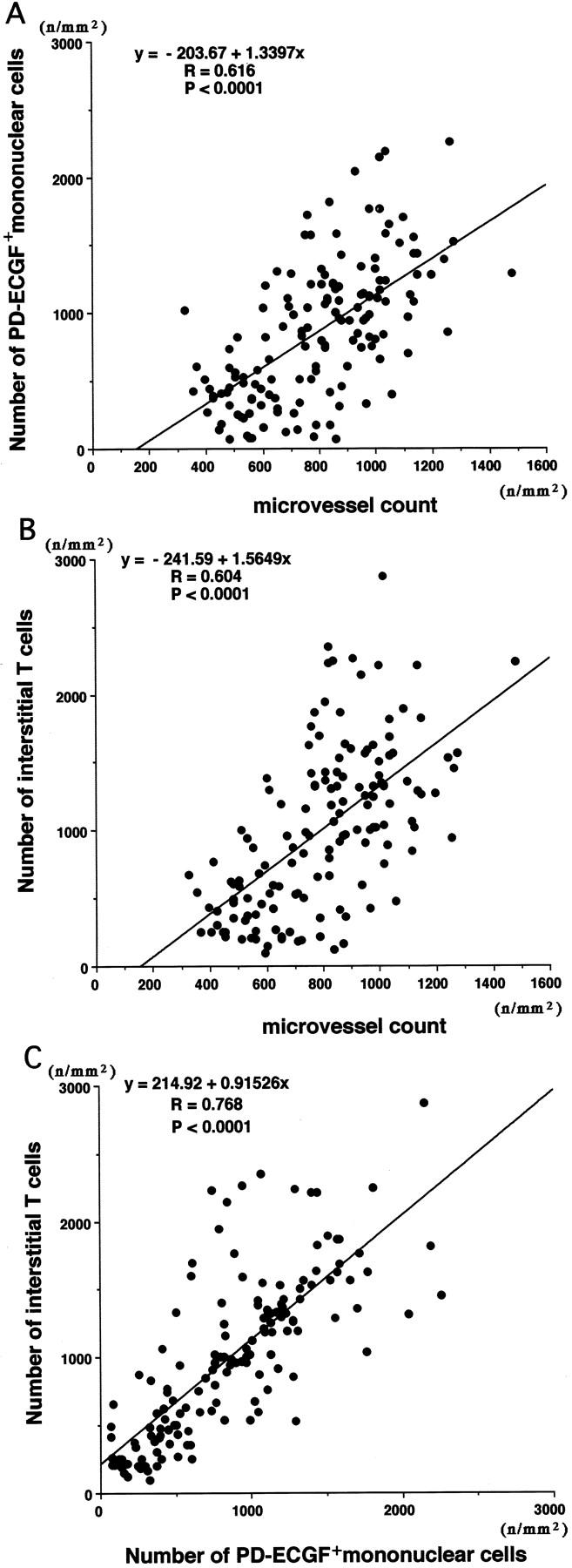

Relationship between PD-ECGF Expression, Interstitial T-Cell Accumulation, and Microvessel Count

A significant correlation was noted between microvessel count and the number of PD-ECGF+ tubular cells (P = 0.0002) or the number of PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells (P < 0.0001) by Spearman’s test (Table 1) ▶ . A significant correlation was also observed between the number of T cells and microvessel count (P < 0.0001), and between the number of T cells and the number of PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells (P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Relationship between Numbers of PD-ECGF+ Tubular Cells, PD-ECGF+ Interstitial Mononuclear Cells, Interstitial T Cells, and Microvessels

| Microvessel count | Interstitial T cells | |

|---|---|---|

| PD-ECGF+ tubular cells | P = 0.0002 | — |

| PD-ECGF+ mononuclear cells | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 |

| Interstitial T cells | P < 0.0001 | — |

P values were obtained by Spearman test.

Microvessel count increased with increasing numbers of PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells or interstitial T cells (Figure 8, A and B) ▶ . Furthermore, the number of PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells increased in proportion to the number of interstitial T cells (Figure 8C) ▶ .

Figure 8.

Relationship between microvessel count and number of PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells (A) or number of interstitial T cells (B), and between number of PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells and number of interstitial T cells (C). Values were obtained by simple regression analysis.

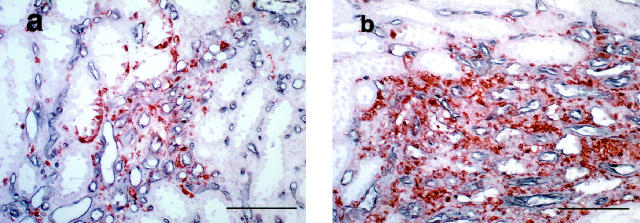

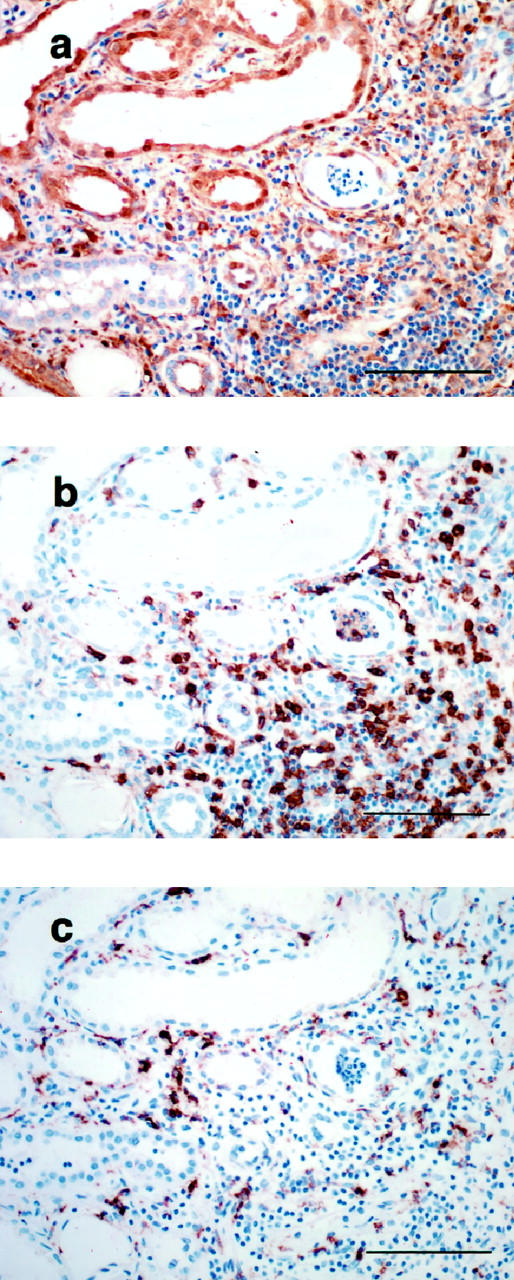

By double staining with CD 34 and PD-ECGF antibodies, we observed a remarkable increase of PD-ECGF immunostaining on tubular cells and interstitial mononuclear cells in fibrotic areas with hypervascularity (Figure 9, a and b) ▶ .

Figure 9.

Double staining of CD34 (black color deposit) and PD-ECGF (brown color deposit). a: Grade 1 fibrosis. b: Grade 2 fibrosis. PD-ECGF+ tubules and mononuclear cells are observed around the up-regulated microvessels in areas with grade 1 and grade 2 fibrosis. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Discussion

Two pathways have been advocated in relation to the progression of chronic renal diseases. 32 Diseases that are primarily glomerular may deteriorate owing to progressive glomerulosclerosis. Diseases that are mainly tubulointerstitial may progress via interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and interstitial mononuclear cell infiltration. In recent years, particular attention has been paid to tubulointerstitial pathology, and the severity of renal dysfunction is thought to correlate more closely with tubulointerstitial changes than glomerular lesions even in primary glomerular disease. 2,3,5,12 An increase of interstitial volume through up-regulation of interstitial extracellular matrix obliterates the postglomerular capillary network and results in local ischemia and tubular injury. 4,5 In tumor growth, wound healing and chronic inflammation, hypoxia, and/or inflammatory cell infiltration appear to be the common events preceding neovascularization. 6-7,9-11,15,41,42 Although angiogenesis is assumed to play a critical role in the progression of tubulointerstitial injury, the mechanism of new vessel formation secondary to renal interstitial fibrosis is not well defined. Previous studies that examined mainly primary glomerular diseases have shown that the number of intertubular capillaries is reduced in areas with interstitial fibrosis, and a significant negative correlation is noted between the number of interstitial capillaries and serum creatinine levels. 2,4 We selected scarred kidneys secondary to a variety of urinary tract diseases as a model to assess up-regulation of angiogenesis in interstitial space and to evaluate its role in the progression of tubulointerstitial injury, because tubulointerstitial pathology is the primary lesion in these kidneys, and interstitial fibrosis and mononuclear infiltration are more intense than in primary glomerular diseases.

In this study we demonstrated a significant increase in microvessel density and interstitial mononuclear infiltration in areas with interstitial fibrosis in the scarred kidneys. Microvessels located in these areas strongly expressed endogrin, a marker of vascular proliferation and a putative promoter of neovascularization. 40 Immunostaining of endogrin also increased in microvessels located in the interstitial space in areas with grade 1 fibrosis, where microvessel density was not significantly increased. In previous studies, angiogenesis has been used to describe vascular changes in chronic inflammation that involve endothelial cell proliferation without new vessel formation. 42,43 These studies indicate that angiogenesis appears to be up-regulated in the early stage of tubulointerstitial injury.

The new blood vessels observed in the scarred kidneys probably did not contribute to renal function because these vessels were predominantly located in the fibrotic areas, where there were fewer normal tubules and more atubular glomeruli than in normal or less fibrotic areas. Microvessel counts diminished remarkably in the intensely scarred areas, where normal renal components were almost completely replaced by fibrotic tissue. We suggest that the new vessels play a critical role in sustaining the interstitial inflammatory process as in a variety of chronic inflammations, 44 and that vascular regression occurs after the glomeruli and tubules are almost completely destroyed and replaced by extracellular matrix as in the process of wound healing. 41

In a variety of inflammatory disorders, leukocyte recruitment precedes the formation of new vessels. 6,7,15 Recent studies have shown that macrophages and T cells have a potential to produce angiogenic molecules including VEGF, TNF-α, basic fibroblast growth factor, and PD-ECGF. 14,18-24 We observed infiltration of T cells, macrophages, and B cells in fibrotic areas of the scarred kidneys. B cells accumulated mainly in and around germinal centers that were found in the interstitial space with grade 3 fibrosis. An increase of macrophage infiltration was observed in the interstitial areas with grades 2 and 3 fibrosis, but these macrophages were less populous than T cells. The predominant cell type infiltrating the interstitial space in the scarred kidney was T cells. These cells were also found in interstitial spaces with grade 1 fibrosis, in which macrophages were scarcely present. We observed a significant correlation between microvessel count and the number of interstitial T cells. These results suggest that T cells are the main infiltrating mononuclear cells that promote the formation of new blood vessels.

Various growth factors and cytokines have an angiogenic activity. 6,7 PD-ECGF is one of the potent promoters of angiogenesis in pathological conditions. 23,25 In human breast cancer cells, hypoxia up-regulates the expression of PD-ECGF proteins in vitro and in vivo. 45 PD-ECGF expression is assumed to be elevated in areas of interstitial fibrosis in scarred kidneys because local oxygen supply is most likely to be diminished in these areas owing to obliteration of the postglomerular capillary network, and tubules, fibroblasts, and mononuclear infiltrates are able to produce PD-ECGF. 22-24 Immunostaining of PD-ECGF increased remarkably on tubular cells, including the atrophic tubules located in fibrotic areas of the scarred kidneys. In addition, a significant correlation was noted between the number of PD-ECGF+ tubular cells and microvessel count. PD-ECGF was also expressed in the interstitial mononuclear cells. Immunohistochemical examinations showed that T cells were the predominant cells accumulated in the scarred kidneys. The number of T cells correlates significantly with that of PD-ECGF+ interstitial mononuclear cells. These results indicate that T cells may be the main interstitial mononuclear cells that express PD-ECGF. Our observations suggest that injured tubules and interstitial inflammatory infiltrates with a predominance of T cells may play an important role in angiogenesis through the production of angiogenic molecules including PD-ECGF, 3,12,13,18-24 and formation of new vessels in scarred kidneys may be one of the critical factors in the progression of tubulointerstitial injury. On the other hand, PD-ECGF expression decreases in the interstitial spaces of intensely scarred areas where microvessel density is reduced.

In theory, production of PD-ECGF and PD-ECGF-mediated angiogenic activity should increase during the accumulation of extracellular matrix and mononuclear infiltrates in the interstitial spaces and then decrease when these spaces are completely replaced by fibrosis tissue. Microvessel density should follow the same trend.

In conclusion, we suggest from our observations that angiogenesis may play a critical role in the progression of tubulointerstitial injury in scarred kidneys and that PD-ECGF produced by tubular cells and mononuclear infiltrates is one of the important contributors to new vessel formation. The exact mechanisms by which angiogenesis affects the progression of tubulointerstitial injury are unknown, but up-regulated microvessel formation may contribute either to sustain chronic inflammation and stimulate extracellular matrix accumulation by producing growth factors, cytokines, and adhesion molecules or to exacerbate the tubulointerstitial injury by invading normal interstitial space as in rheumatoid arthritis. Our current knowledge indicates that angiogenesis results from complex interactions between positive and negative regulators of endothelial cell differentiation, proliferation, migration, and maturation. 6,7 PD-ECGF is one of the positive angiogenic factors. Normally, growth factors that promote angiogenesis are counterbalanced by endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis. Because an imbalance between positive and negative angiogenic factors can induce angiogenesis, further studies are needed to evaluate the changes of negative regulators of angiogenesis, such as thrombospondin or angiostatin.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Ryuichiro Konda, M.D., Department of Urology, Tohoku University School of Medicine, 1–1 Seiryomachi, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8574, Japan. E-mail: r-konda@uro.med.tohoku.ac.jp.

Supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture (No. 10470328).

References

- 1.Mackensen-Haen S, Bader R, Grund KE, Bohle A: Correlation between renal cortical interstitial fibrosis, atrophy of proximal tubules and impairment of the glomerular filtration rate. Clin Nephrol 1981, 4:167-171 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohle A, Muler GA, Wehrmann M, Mackensen-Haen S, Xiao JC: Pathogenesis of chronic renal failure in the primary glomerulopathies, renal vasculopathies, and chronic interstitial nephritides. Kidney Int 1996, 49:s2-s9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eddy AA: Experimental insights into the tubulointerstitial disease accompanying primary glomerular lesions. J Am Soc Nephrol 1994, 5:1273-1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohle A, Gise HV, Machensen-Haen S, Stark-Jakob B: The obliteration of the postglomerular capillaries and its influence upon the function of both glomeruli and tubuli. Klin Wochenschr 1981, 59:1043-1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ong ACM, Fine LG: Loss of glomerular function and tubulointerstitial fibrosis: cause or effect. Kidney Int 1994, 45:345-351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folkman J, Shing Y: Angiogenesis. J Biol Chem 1992, 16:10931-10934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folkman J: Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nat Med 1995, 1:27-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shweiki D, Ition A, Soffer D, Keshet E: Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature 1992, 359:843-845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandner P, Wolf K, Bergmaier U, Gess B, Kurtz A: Induction of VEGF and VEGF receptor gene expression by hypoxia: divergent regulation in vivo and in vitro. Kidney Int 1997, 51:448-453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arras M, Ito WD, Scholz D, Winkler B, Schaper J, Schaper W: Monocyte activation in angiogenesis and collateral growth in the rabbit hindlimb. J Clin Invest 1998, 101:40-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaper W, Ito WD: Molecular mechanisms of coronary collateral vessel growth. Circ Res 1996, 79:911-919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eddy AA: Molecular insights into renal interstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 1996, 7:2495-2508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein-Oakley AN, Maguire JA, Dowling J, Perry G, Thomson NM: Altered expression of fibrogenic growth factor in IgA nephropathy and focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 1997, 51:195-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin P: Wound healing: aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science 1997, 276:75-81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrara N: Missing link in angiogenesis. Nature 1995, 376:467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshioka K, Takemura T, Matsubara K, Miyamoto H, Akano N, Maki S: Immunohistochemical studies of reflux nephropathy: the role of extracellular matrix, membrane attack complex, and immune cells in glomerular sclerosis. Am J Pathol 1987, 129:223-231 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konda R, Sakai K, Ota S, Takeda A, Chida N, Sato H, Orikasa S: Soluble interleukin-2 receptor in children with reflux nephropathy. J Urol 1998, 159:535-539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman MR, Schneck FX, Gagnon ML, Corless C, Soker S, Niknejad K, Peoples GE, Klagsbrun M: Peripheral blood T lymphocytes and lymphocytes infiltrating human cancers express vascular endothelial growth factor: a potential role for T cells in angiogenesis. Cancer Res 1995, 55:4140-4145 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiong M, Elson G, Legarda D, Leibovich SJ: Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by murine macrophages: regulation by hypoxia, lactate, and the inducible nitric oxide synthase pathway. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:587-598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leibovich SJ, Polverini PJ, Shepard HM, Wiseman DM, Shively V, Nuseir N: Macrophage-induced angiogenesis is mediated by tumor necrosis factor-α. Nature 1987, 329:630-632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nathan CF: Secretory products of macrophages. J Clin Invest 1987, 79:319-326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshimura A, Kuwazuru Y, Furukawa T, Yoshida H, Yamada K, Akiyama S: Purification and tissue distribution of human thymidine phosphorylase; high expression in lymphocytes, reticulocytes and tumors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1990, 1034:107-113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox SB, Moghaddam A, Westwood M, Turley H, Bicknell R, Gatter KC, Harris AL: Platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor/thymidine phosphorylase expression in normal tissues: an immunohistochemical study. J Pathol 1995, 176:183-190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi Y, Bucana CD, Liu W, Yoneda J, Kitadai Y, Cleary KR, Ellis LM: Platelet-derived endothelial growth factor in human colon cancer angiogenesis: Role of infiltrating cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996, 88:1146-1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishikawa F, Miyazono K, Hellman U, Drexler H, Wernstedt C, Hagiwara K, Usui K, Takaku F, Risau W, Heldin CH: Identification of angiogenic activity and the cloning and expression of platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor. Nature 1989, 338:557-562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sumizawa T, Furukawa T, Haraguchi M, Yoshimura A, Takeyasu A, Ishizawa M, Yamada Y, Akiyama S: Thymidine phosphorylase activity associated with platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor. J Biochem 1993, 114:9-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haraguchi M, Miyadera K, Uemura K, Sumizawa T, Furukawa T, Yamada K, Akiyama S, Yamada Y: Angiogenic activity of enzyme. Nature 1994, 368:198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevenson DP, Milligan SR, Collins WP: Effect of platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor/thymidine phosphorylase, substrate, and products in a three-dimensional model of angiogenesis. Am J Pathol 1998, 152:1641-1646 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imazono Y, Takebayashi Y, Nishiyama K, Akiba S, Miyadera K, Yamada Y, Akiyama S, Ohi Y: Correlation between thymidine phosphorylase expression and prognosis in human renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1997, 15:2570-2578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takebayashi Y, Akiyama S, Akiba S, Yamada K, Miyadera K, Sumizawa T, Yamada Y, Murata F, Aikou T: Clinicopathologic and prognostic significance of an angiogenic factor, thymidine phosphorylase, in human colorectal carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996, 88:1110-1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toi M, Inada K, Hoshina S, Suzuki H, Kondo S, Tominaga T: Vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor are frequently coexpressed in highly vascularized human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 1995, 1:961-964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcussen N: Biology of disease: atubular glomeruli and the structural basis for chronic renal failure. Lab Invest 1992, 66:265-284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker GJ, Kincaid-Smith P: Reflux nephropathy: the glomerular lesion and progression of renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol 1993, 7:365-369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konda R, Orikasa S, Sakai K, Ota S, Kimura N: The distribution of renin containing cells in scarred kidneys. J Urol 1996, 156:1450-1454 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson RJ, Alpers CE, Yoshimura A, Lombardi D, Pritzl P, Floege J, Schwartz SM: Renal injury from angiotensin II-mediated hypertension. Hypertension 1992, 19:464-474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolf G, Neilson EG: Angiotensin II as a renal cytokine. News Physiol Sci 1994, 9:40-42 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klahr S, Ishidoya S, Morissey J: Role of angiotensin II in the tubulointerstitial fibrosis of obstructed nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 1995, 26:141-146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishida M, Hino A, Mori K, Matsumoto T, Yoshikubo T, Ishitsuka H: Preparation of anti-human thymidine phosphorylase monoclonal antibodies useful for detecting the enzyme levels in tumor tissues. Biol Pharm Bull 1996, 19:1407-1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haruta Y, Seon BK: Distinct human leukemia-associated cell surface glycoprotein GP160 defined by monoclonal antibody SN6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1986, 83:7898-7902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burrows FJ, Derbyshire EJ, Tazzari PL, Amlot P, Gazdar AF, King SW, Letarte M, Vitettaa ES, Thorpe PE: Up-regulation of endogrin on vascular endothelial cells in human solid tumors: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Clin Cancer Res 1995, 1:1623-1634 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nissen NN, Polverini PJ, Koch AE, Volin MV, Gamelli RL, DiPietro LA: Vascular endothelial growth factor mediates angiogenic activity during the proliferative phase of wound healing. Am J Pathol 1998, 152:1445-1452 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thurston G, Murphy TJ, Baluk P, Lindsey JR, McDonald DM: Angiogenesis in mice with chronic airway inflammation. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:1099-1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolf JEJ: Angiogenesis in normal and psoriatic skin. J Clin Invest 1989, 61:139-142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Majno G: Chronic inflammation: links with angiogenesis and wound healing. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:1035-1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griffiths L, Dachs GU, Bicknell R, Harris AL, Stratford IJ: The influence of oxygen tension and pH on the expression of platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor/thymidine phosphorylase in human breast tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res 1997, 57:570-572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]