Abstract

In human pregnancy, trophoblasts are the only cells of fetal origin in direct contact with the maternal immune system: syncytiotrophoblasts are in contact with maternal blood, whereas extravillous trophoblasts are in contact with numerous maternal uterine natural killer (NK) cells. Therefore, trophoblasts are thought to play a key role in maternal tolerance to the semiallogeneic fetus, in part through cytokine production and NK cell interaction. Epstein-Barr virus-induced gene 3 (EBI3) encodes a soluble hematopoietin receptor related to the p40 subunit of interleukin-12. Previous studies indicated that EBI3 is expressed in the spleen and tonsils, and at high levels in full-term placenta. To investigate further EBI3 expression throughout human pregnancy, we generated monoclonal antibodies specific for EBI3 and developed an EBI3 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Immunohistochemical experiments with EBI3 monoclonal antibody on first-, second-, and third-trimester placental tissues demonstrated that EBI3 was expressed throughout pregnancy by syncytiotrophoblasts and extravillous trophoblasts (cytotrophoblast cell columns, interstitial trophoblasts, multinucleated giant cells, and trophoblasts of the chorion laeve). EBI3 expression was also induced during in vitro differentiation of trophoblast cell lines. In addition, large amounts of secreted EBI3 were detected in explant cultures from first-trimester and term placentae. Consistent with these data, EBI3 levels were strongly up-regulated in sera from pregnant women and gradually increased with gestational age. These data, together with the finding that EBI3 peptide is presented by HLA-G, suggest that EBI3 is an important immunomodulator in the fetal-maternal relationship, possibly involved in NK cell regulation.

Human pregnancy is a unique immune situation in which the semiallogeneic fetus avoids maternal rejection. Fetal trophoblast cells, which are in direct contact with maternal immune cells, are thought to play a key role in maternal tolerance. Trophoblasts are specialized epithelial cells and are distinguished into several types depending on their stage of differentiation and location at the maternal-fetal interface. Floating villi are composed of two trophoblast layers: an inner layer of mononucleated cytotrophoblast stem cells, and an outer layer of syncytiotrophoblasts resulting from the differentiation and cell fusion of cytotrophoblasts into syncytium. Syncytiotrophoblasts cover the entire surface of the villi and are in direct contact with maternal blood in the intervillous space. These cells, because of their specific location, play a key role in nutrient and gas exchange between the mother and the developing fetus, and may play an important role in peripheral tolerance. At selected sites in the villi, cytotrophoblasts can follow a second differentiation pathway by leaving the villous basement membrane, proliferating, and aggregating into the cytotrophoblast cell column characteristic of anchoring villi. Anchoring villi are attached to the uterine wall, and cytotrophoblasts from these anchoring villi invade the uterus wall. These invasive extravillous trophoblasts comprise a heterogeneous population of interstitial trophoblasts, multinucleated placental bed giant cells, and trophoblast cells that invade the uterine spiral arteries and adopt a vascular phenotype, as assessed by their expression of endothelial cell surface markers. Parallel to trophoblast invasion, the uterine endometrium decidualizes and is infiltrated by a large number of maternal immune cells. These cells are particularly abundant at the site of implantation, the decidua basalis, and are in close contact with invasive extravillous trophoblasts. Maternal uterine natural killer (NK) cells are particularly abundant accounting for up to 70% of the total decidual leukocyte population during early pregnancy. 1,2

The mechanisms by which the fetus escapes the maternal immune response are not fully understood. The expression by extravillous trophoblasts of a nonclassical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I antigen, HLA-G, may play a role by regulating the maternal NK response. 2,3 The local secretion of soluble factors, including hormones and cytokines, may also be involved. Indeed, the expression at the maternal-fetal interface of various cytokines with a Th2 or immunosuppressive phenotype, such as interleukin (IL)-10, IL-13, or transforming growth factor-β, has been described in human pregnancy. 4-7

Previously, we have reported the identification of a novel homologue to IL-12 p40, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-induced gene 3 (EBI3). 8 EBI3 is expressed at a high level by B cell lines transformed in vitro by EBV. In vivo, EBI3 is expressed in lymphoid organs such as tonsil and spleen, and at a very high level in term placenta. EBI3 has 27% amino acid identity to the IL-12 p40 subunit. Like p40, it lacks a membrane-anchoring motif and corresponds to the extracellular portion of a type I cytokine receptor. Also like p40, EBI3 can associate with the p35 subunit of IL-12 to form a heterodimeric hematopoietin, EBI3/p35. 9 Although EBI3 is structurally related to IL-12 p40, its biological activity is expected to be opposite to that of IL-12. IL-12 plays a key role in the cell-mediated immune response by driving the response toward a Th1 type, and by stimulating the activation and proliferation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) and NK cells. 10-12 The high level of EBI3 expression observed in EBV-infected B lymphocytes and at the fetal-maternal interface, two situations in which a dampening of the cytotoxic cell-mediated immune response and of the Th1 response is required, 13-17 is in favor of an immunosuppressive or Th2 function for EBI3 or EBI3/p35. Consistent with this hypothesis, analysis of EBI3 expression in human intestinal diseases has demonstrated that EBI3 and IL-12 display opposite patterns of expression. 18

To investigate further the expression and potential role of EBI3 in the placental-maternal relationship, we generated specific anti-EBI3 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that could be used in immunohistochemical studies on frozen and paraffin-embedded tissues, and developed an EBI3 sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Using these antibodies, we analyzed EBI3 expression throughout human pregnancy, both in situ and in in vitro experiments.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

Plasmid pQE-EBI3 was constructed by polymerase chain reaction amplification of the human EBI3 cDNA amino acids 25 to 229 8 using the 5′ primer (5′-ATCCGAGCTCCCCAGCAGCTCTGACACTG-3′) and the 3′ primer (5′-CCCAAGCTTCTACTTGCCCAGCGTCATT-3′). The polymerase chain reaction product was digested with SacI and HindIII and cloned into the SacI-HindIII sites of plasmid pQE-31 (Qiagen). The resulting plasmid encodes an N-terminal hexahistidine-tagged EBI3 protein deleted for its signal peptide. pSG5-EBI3, pSG5-EBI3-Flag, pSG5-p40-Flag, and pSG5-p35-Flag expression vectors have been previously described. 8,9

Cell Lines, Transfection, and Cell Culture Reagents

BJAB, BL41, and Ramos are EBV-negative Burkitt lymphoma cell lines. IB4 and NC37 are EBV-transformed human B cell lines. Jurkat, Molt-4, and CEM-T are human T cell leukemia lines, and U937 and HL-60 are human myelocytic and myeloblastic cell lines, respectively. BeWo and Jar are human choriocarcinoma cell lines. COS7 is a SV40-transformed monkey kidney cell line. Cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640-Glutamax (all cell lines except COS7) or Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium-Glutamax (COS7) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics. Approximately 10 7 BJAB cells or 4.10 6 COS7 cells were transfected by electroporation on a Biorad electroporator at 210 V and 960 μF in 400 μl of RPMI medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and forskolin were purchased from Sigma and Calbiochem, respectively.

Production and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

For recombinant 6His-EBI3 expression, M15/pREP4 cells (Qiagen) transformed with pQE-EBI3 were induced by incubation with 1 mmol/L isopropylthio-β-d-galactoside for 4 hours. The bacterial cell pellet was lysed in guanidine lysis buffer (6 mol/L guanidine-HCl, 0.1 mol/L NaH2PO4, 0.05 mol/L Tris, pH 8) and sonicated. Lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove debris, and incubated with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose beads (Qiagen) for 1 hour at room temperature. Beads were washed with washing buffer (8 mol/L urea, 0.1 mol/L NaH2PO4, 0.01 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 6.3) and the His-tagged protein was eluted by adding elution buffer (8 mol/L urea, 0.1 mol/L NaH2PO4, 0.01 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 4.5). Fractions containing 6HisEBI3 protein were dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 6HisEBI3 protein concentration was determined using the Pierce Micro bicinchoninic acid protein assay.

Recombinant Flag-tagged EBI3 and Flag-tagged p40 were purified from the culture supernatant of COS7 cells transiently transfected with pSG5-EBI3-Flag or pSG5-p40-Flag, respectively. Sixty to 70 hours after transfection, COS7 cell supernatant was harvested, supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride), and centrifuged to remove cell debris. Supernatants were then incubated for 3 hours at 4°C with M2 anti-Flag affinity gel (Sigma). Beads were washed twice with 1% Nonidet P-40 buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 20 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 3% glycerol, 1.5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), twice with Tris-buffered saline (TBS: 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 150 mmol/L NaCl, pH 7.4), and Flag-tagged proteins were eluted by addition of Flag peptide (250 μg/ml in TBS). p35-associated EBI3 was affinity-purified on M2 anti-Flag affinity gel under the same conditions from the culture supernatant of COS7 cells co-transfected with pSG5- EBI3 and pSG5-p35-Flag. Under these conditions, all of the purified EBI3 was associated with p35-Flag and most of the p35-Flag was associated with EBI3. The concentration of purified EBI3-Flag was determined by titration by M2 anti-Flag Western blot analysis using a C-terminal Flag-tagged BAP protein (Sigma) as a standard. The quantitative results obtained in this assay were similar to those obtained by titration by anti-EBI3 blot analysis using 6His-EBI3 as a standard. The concentration of purified p40-Flag was determined by IL-12 blot analysis using recombinant IL-12 (R&D Systems) as a standard. Soluble CNTF-Rα was purchased from R&D Systems.

Development of Anti-EBI3 mAbs

Mouse mAbs specific for human EBI3 were obtained by immunizing mice with a N-terminal hexahistidine-tagged EBI3 fusion protein (6His-EBI3) purified from bacteria. Mice immunization and hybridoma production were performed through Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium) mAb production customer service. Briefly, four BALB/c mice were immunized by three injections of purified 6His-EBI3 (50 μg per injection) on days 0, 21, and 42. Sera of immunized mice collected on days 14, 35, and 56 after immunization were tested by indirect ELISA for reactivity against the immunogen. The best responding mouse was given a final Ag injection and selected for the fusion. Spleen lymphocytes were fused to the Sp2/O-Ag14 cell line using polyethylene glycol, and the hybridomas were seeded in hypoxanthine-aminopterin-thymidine medium in 96-well plates. IgG-positive hybridoma supernatants were screened by indirect ELISA for reactivity against the following antigens: a hexahistidine peptide (negative control), purified bacterial 6His-EBI3, and purified COS7 cell-derived EBI3-Flag. Hybridoma supernatants giving positive results in these assays were further tested by Western blotting and by indirect immunofluorescence staining of pSG5 or pSG5-EBI3-Flag-transfected BJAB cells. Clones of interest were then subcloned by limiting dilution, and the subclones were tested as described above for the parental clones. Two of the subclones, 2G4H6 and 1A1B2H3, were selected for this study. The 2G4H6 mAb was determined to be an IgG2a, kappa, and the 1A1B2H3 mAb an IgG1, kappa. Both hybridomas were submitted to ascite production in BALB/c mice, and mAbs were purified from ascite by chromatography on Protein G-Sepharose. The 2G4H6 mAb was biotinylated using the biotin labeling kit from Boehringer Mannheim, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

EBI3 ELISA

Microtitration plates (96-well, Linbro; Flow Laboratories Inc., Virginia) were coated with 100 μl of 1A1B2H3 mAb at 5 μg/ml in 0.05 mol/L carbonate buffer, pH 9.6, overnight at 4°C, washed with PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), and blocked with 200 μl of PBS-5% bovine serum albumin for 2 hours at room temperature. Test samples (100 μl) were added to the wells and incubated for 18 hours at 4°C. After washing with PBS-T, biotinylated 2G4H6 mAb was added at a 1:200 dilution in PBS-T (∼4 μg/ml) and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing with PBS-T, 100 μl of PBS containing streptavidin linked to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham) diluted 1:2000 was added and the plates incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Wells were further washed with PBS-T, and the reaction was developed by adding 200 μl of ortho-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride solution (Sigma). After 30 minutes, the reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl of 3 mol/L HCl and optical density was read at 490 nm. Recombinant Flag-tagged EBI3 purified from the culture supernatant of transfected COS7 cells was used as a standard. The sensitivity limit was ∼0.5 to 1 ng/ml and only values more than 1 ng/ml were considered as positive.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Cell lines or transfected cells were washed in cold PBS and lysed for 1 hour on ice in ice-cold Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 20 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 3% glycerol, 1.5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C and total protein concentration was determined using the Pierce Micro bicinchoninic acid protein assay. For immunoprecipitation, cell lysates were precleared with GammaBindPlus-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) for 1 to 2 hours at 4°C. Cleared lysates were incubated with M2 anti-Flag antibody (Sigma) or EBI3 mAbs for 2 hours at 4°C, and then with GammaBindPlus-Sepharose for 1 hour at 4°C. Beads were washed four times with 1 ml of lysis buffer and protein complexes were recovered by boiling in sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer. Immunoprecipitated material was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblotting. On blots, EBI3 was detected using 2G4H6 mAb, and IL-12 p40 was detected using goat affinity-purified anti-IL-12 polyclonal antibodies (R&D Systems). Binding of antibodies was detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG antibodies (1:5000 dilution, Amersham), or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-goat antibodies (1:5000 dilution, Santa Cruz) and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Pierce).

Human Tissues and Sera

Eighteen placentae were analyzed by immunohistochemistry. For each placenta, frozen and/or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues were analyzed. Frozen tissues were collected from placentae at 6, 9, 10, 17, 29, 33, 36, and 41 weeks of pregnancy, and paraffin-embedded tissues were prepared from placentae collected at 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 17, 20, 27, 33, 35, 38, and 39 weeks of pregnancy. Tissues collected at 17 and 33 weeks of gestation corresponded to placentae for which both frozen and paraffin-embedded tissues were prepared and analyzed. First-trimester placentae were obtained from voluntary pregnancy termination performed by vacuum suction (all but one case) or RU486 administration (4-week placenta). Second- and third-trimester placentae were obtained from therapeutic termination (n = 1), miscarriage (n = 1), cesarean section delivery (n = 2), or natural delivery (n = 6). In all cases, placentae were selected for the absence of abnormality on macroscopic and histological examination. Villi maturation was in accordance with gestational age, and no lesions, in particular no vascular lesions indicative of pre-eclampsia, and no infection were observed.

Sera from 10 women with normal pregnancies, collected at various times during pregnancy (five to eight sera per individual) for serological diagnosis, were used in this study. Sera from nonpregnant women (n = 10) and men (n = 4) were used as controls.

Placental Explant Culture

For placental explant culture, first-trimester placentae (n = 7) were obtained after 6 to 7.5 weeks of pregnancy by voluntary pregnancy termination initiated by RU486 administration and term placentae (n = 12) were obtained from cesarean section delivery. In all cases, placental villi were isolated, minced, washed three times in Hanks’ balanced salt solution and a total of 3 g of placenta villi was cultured in 20 ml of RPMI 1640-Glutamax supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, antibiotics, and 1% sodium bicarbonate. After various times of culture, culture supernatants were harvested, spun at 2000 × g to remove debris and stored at −80°C.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunochemistry was performed on either cytospin preparation, frozen tissue sections fixed in acetone, or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections.

For cytospin preparation, transfected cells were washed in PBS, cytocentrifuged, air-dried, fixed in cold acetone/methanol (1:1), and stored at −80°C.

For immunostaining of frozen sections or cytospin samples, slides were rehydrated in PBS, incubated for 5 minutes with a peroxidase-blocking solution (DAKO), washed, and saturated in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum and 20% normal human serum. Slides were then incubated with the primary mAb diluted in PBS-2% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour. Binding of mAbs was detected using an indirect avidin-biotin peroxidase kit (Biogenex). The peroxidase reaction was developed with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma) and sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin.

For immunostaining of paraffin sections, sections were first deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in successive ethanol baths and PBS. Ag was retrieved by microwave heat pretreatment in citrate buffer. Slides were saturated by incubation with PBS containing 5% normal goat serum (DAKO) for 10 minutes at room temperature. They were then incubated with the primary antibody for 30 minutes, followed by an indirect avidin-biotin peroxidase technique (DAKO StreptABComplex/horseradish peroxidase duet). The peroxidase reaction was developed with 3′-diaminobenzidine (Immunotech) and sections were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin.

EBI3 was detected using 2G4H6 mAb at 2 μg/ml. IL-12 p35 was detected using G161-566 p35 mAb (IgG1, PharMingen) at 1.6 μg/ml. This mAb was verified to react specifically with p35 by immunostaining, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting performed with transfected cells or cell lysates. CD56 mAb (IgG1, Novocastra Laboratories Ltd.) was used at a 1:25 dilution. Anti-cytokeratin mAb (KL1, IgG1; Immunotech) was used at a 1:50 dilution, anti-vimentin mAb (V9, IgG1; BioGenex) was used at a 1:100 dilution, and rabbit anti-human placental lactogen polyclonal antibodies (DAKO) were used at a 1:1000 dilution. RPC5 (IgG2a, kappa; Cappel, Durham, NC) and MOPC21 (IgG1, kappa; Sigma) were used as negative controls.

Photomicrographs were taken on a Leica DMLB microscope using a 3 CCD color video camera (Sony Power HAD) and analyzed with Thunder software. Identical settings were used when scanning serial sections.

Results

Characterization of EBI3 mAbs

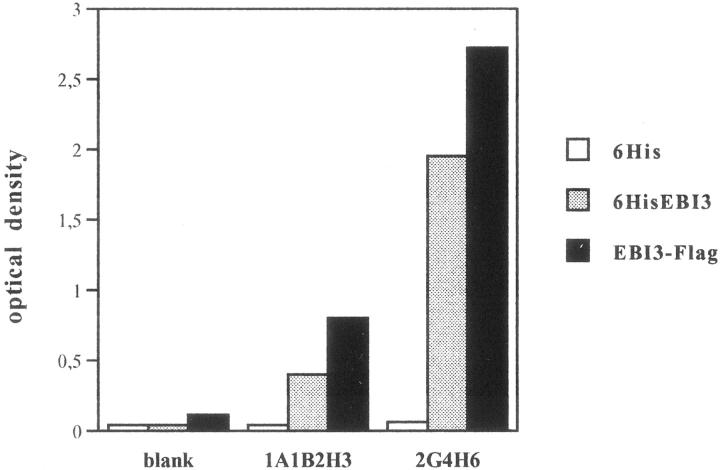

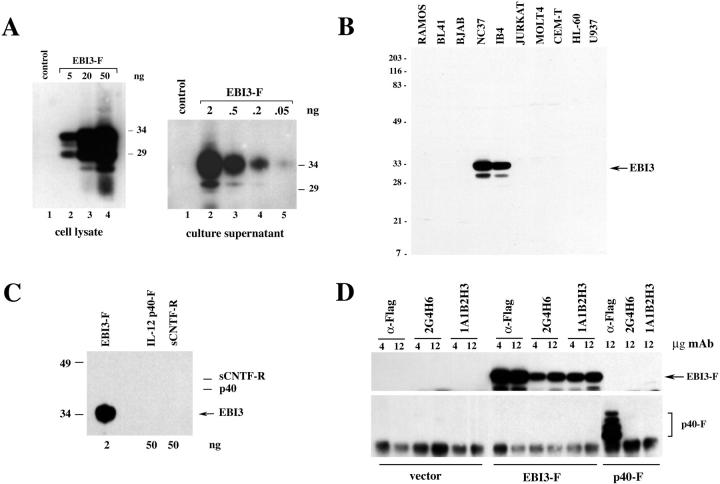

Mouse mAbs specific for human EBI3 were obtained by immunizing mice with a N-terminal hexahistidine-tagged EBI3 fusion protein (6His-EBI3) purified from bacteria. Two of the hybridomas obtained, the 2G4H6 (IgG2a, kappa) and the 1A1B2H3 (IgG1, kappa) mAbs, were used for this study. As shown in Figure 1 ▶ , both clones recognized Escherichia coli-derived 6HisEBI3, as well as COS7 cell-derived EBI3, in indirect ELISA, with 2G4H6 mAb showing a stronger reactivity than 1A1B2H3 mAb. The specificity of the two clones was further analyzed by Western blotting, immunoprecipitation, and immunostaining. First, two cell lines that do not express EBI3, the EBV-negative Burkitt lymphoma BJAB cell line and COS7 cells, were transiently transfected with pSG5-EBI3-Flag or pSG5 control vector, and cell lysates or cell culture supernatants were analyzed by immunoblotting with EBI3 mAbs. On blots, intracellular EBI3 is detected as a 33-kd protein together with smaller degradation products (26 to 29 kd), and the secreted form is detected as a 34-kd protein. 8,9 By 2G4H6 mAb immunoblotting, a strong EBI3 signal was detected in the cell lysate from EBI3-Flag-expressing BJAB cells, but no signal was observed in the lysate from control vector-transfected cells (Figure 2 ▶ A, left). Also, a major 34-kd EBI3-Flag protein, together with a 30-kd degradation product, were detected in the culture supernatant from pSG5-EBI3-Flag-transfected COS7 cells, whereas no signal was observed in the culture supernatant from vector-transfected cells (Figure 2A ▶ , right). 2G4H6 mAb recognized EBI3 with very high sensitivity because as little as 0.2 ng of secreted EBI3-Flag was readily detected by immunoblot analysis, and a faint signal was observed when 0.05 ng of EBI3 was used (Figure 2A ▶ , right). 2G4H6 mAb also recognized natural EBI3 in cell lysates of two EBV-transformed B cell lines, IB4 and NC37, but failed to give any signal in cell lysates of various cell lines that have been previously shown not to express EBI3 (Figure 2B) ▶ . 8,9 By immunoblotting, 2G4H6 mAb did not cross-react with IL-12 p40 or soluble CNTF-R, the two type 1 cytokine receptors most homologous to EBI3 (Figure 2C) ▶ . Also, 2G4H6 mAb specifically immunoprecipitated EBI3-Flag from the lysate of transfected COS7 cells, but did not immunoprecipitate IL-12 p40-Flag (Figure 2D) ▶ . On immunoblots, 1A1B2H3 mAb also recognized EBI3, albeit with low sensitivity (data not shown). As observed for 2G4H6 mAb, 1A1B2H3 mAb specifically immunoprecipitated EBI3-Flag, but not IL-12 p40-Flag, from the lysate of transfected COS7 cells (Figure 2D) ▶ .

Figure 1.

Reactivity of EBI3 mAbs with EBI3 fusion proteins in indirect ELISA. The reactivity of 1A1B2H3 and 2G4H6 hybridoma culture supernatants was tested by indirect ELISA using microwell plates coated with a control hexahistidine peptide (6His), N-terminal hexahistidine-tagged EBI3 fusion protein produced in bacteria (6HisEBI3), or COS7 cell-derived EBI3-Flag (EBI3-F) (250 ng/well).

Figure 2.

Specificity of EBI3 mAbs analyzed by Western blotting and immunoprecipitation. A: BJAB (left) or COS7 (right) cells were transfected with pSG5 (control) or pSG5-EBI3-Flag (EBI3-F), and cell lysates (left) or culture supernatants (right) were analyzed by Western blotting with 2G4H6 hybridoma supernatant. Before 2G4H6 blotting, the amount of EBI3-Flag present in the cell lysate or culture supernatant was determined by titration by M2 anti-Flag Western blot analysis using BAP-Flag protein as a standard, and the amount of EBI3-Flag in the volume of cell lysate or cell supernatant loaded is indicated at the top of the lane. Molecular weight markers (in kd) are indicated on the right. B: Cell lysates (1% Nonidet P-40 extracts, 100 μg per lane) from the cell lines indicated at the top of each lane were tested by Western blotting with 2G4H6 hybridoma supernatant. Molecular weight markers (in kd) are indicated on the left. C: The indicated amounts of purified COS7-derived recombinant EBI3-Flag, COS7-derived recombinant IL-12 p40-Flag, or soluble CTNF-α receptor, were analyzed by immunoblotting with 2G4H6 hybridoma supernatant. The positions of IL-12 p40-Flag and soluble CTNF-α receptor are indicated on the right. D: COS7 cells were transfected with pSG5, pSG5-EBI3-Flag, or pSG5-p40-Flag, and cells were lysed 24 hours after transfection in 1% Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer. Cleared lysates were submitted to immunoprecipitation with various amounts of M2 anti-Flag antibody, 2G4H6 mAb, or 1A1B2H3 mAb as indicated above the lanes. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with 2G4H6 mAb (top) or IL-12 polyclonal antibodies (bottom).

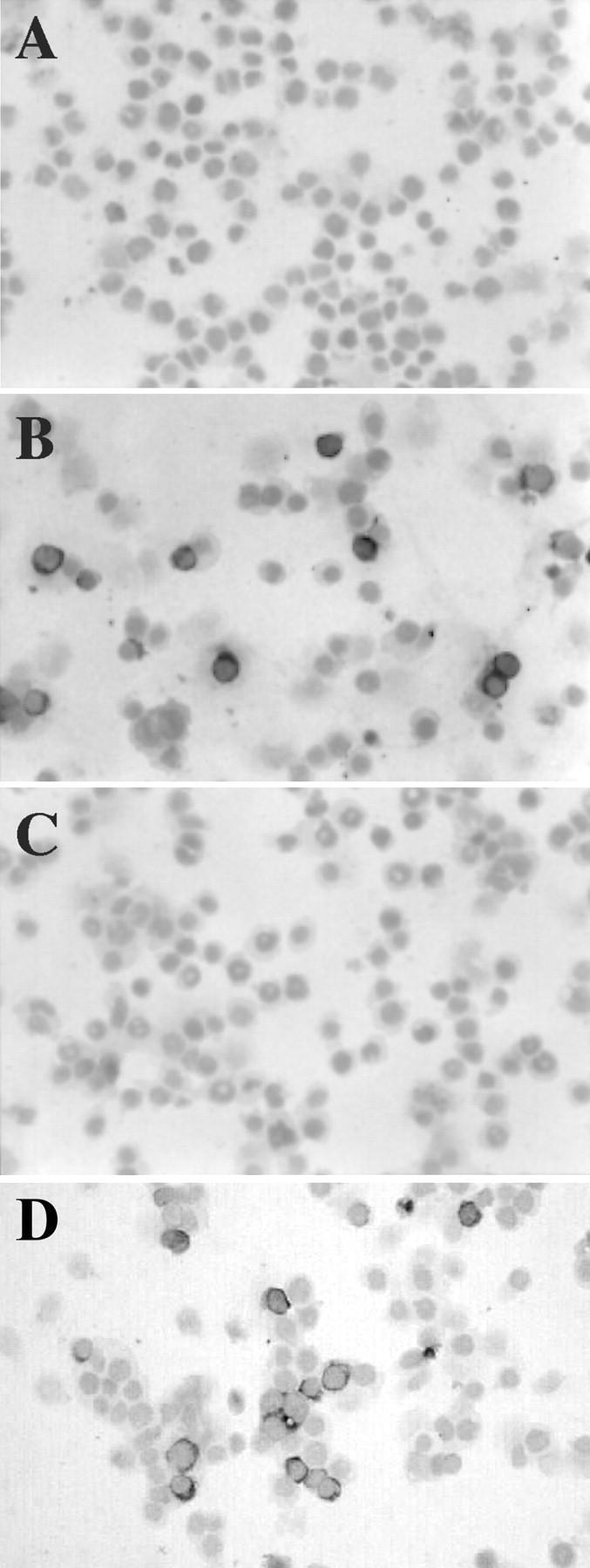

Next, we tested the 2G4H6 mAb for immunostaining (Figure 3) ▶ . BJAB cells were transfected with pSG5 control vector, pSG5EBI3-Flag, or pSG5p40-Flag, and were stained with 2G4H6 mAb, or anti-p40 control mAb. As expected from the previous results, 2G4H6 mAb specifically stained pSG5EBI3-Flag-transfected cells, but did not react with control vector- or pSG5-p40-Flag-transfected cells.

Figure 3.

Specificity of 2G4H6 mAb analyzed by immunostaining. BJAB cells were transfected with pSG5 (A), pSG5-EBI3-Flag (B), or pSG5-p40-Flag (C and D). Approximately 20 hours after transfection, cells were cytospun and subjected to immunostaining with 2G4H6 mAb (A–C), or with IL-12 p40 mAb (D) to control for transfection efficiency and p40 protein expression. Original magnifications, ×200.

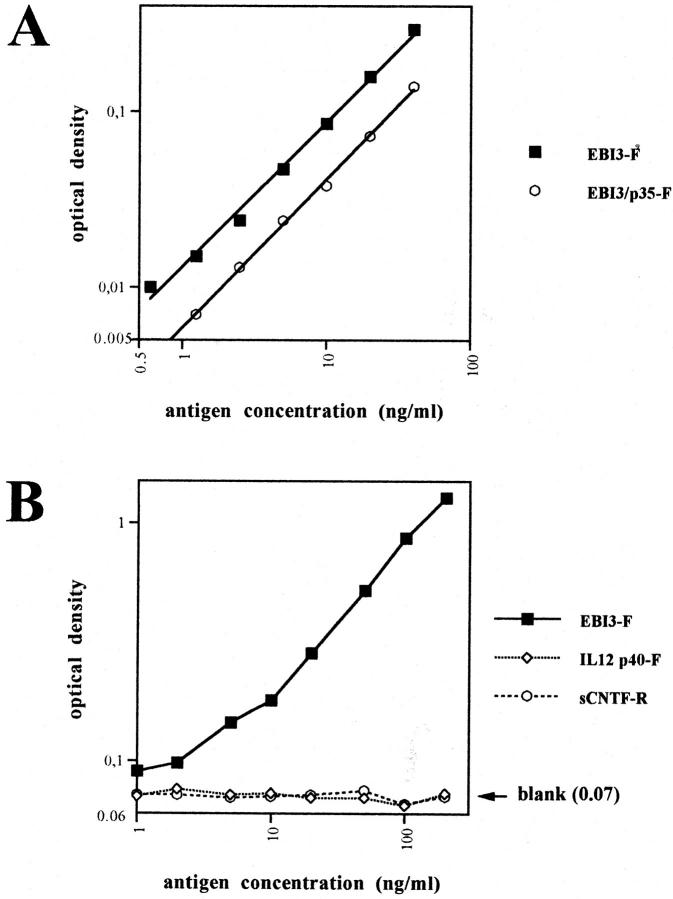

To have an assay to quantify the amount of soluble EBI3 present in serum or culture supernatant, we developed a sandwich ELISA for EBI3, by using 1A1B2H3 mAb as a capture mAb in combination with biotinylated 2G4H6 mAb as a detection mAb (Figure 4, A and B) ▶ . No cross-reactivity with IL-12 p40 or soluble CNTF-R was observed in this assay, even when large amounts of these two molecules were used (up to 200 ng/ml) (Figure 4B) ▶ . In this ELISA, both EBI3 and EBI3/p35 were detected, although reactivity against EBI3/p35 was approximately twofold lower (Figure 4A) ▶ .

Figure 4.

EBI3 sandwich ELISA. A: Detection of EBI3 by sandwich ELISA using 1A1B2H3 mAb as a capture mAb, and biotinylated 2G4H6 as a detection mAb. The assay detects both free EBI3 and EBI3 associated with p35, although the sensitivity is approximately twofold less for the latter. The assay was linear between 0.5 to 40 ng/ml (r = 0.997 for EBI3, and 0.999 for EBI3/p35). The limit of detection for EBI3 was calculated to be 1 ng/ml. B: No cross-reactivity with IL-12 p40 or sCNTF-Rα was observed. Data are represented on a log by log scale (A and B). On B, the mean blank value was not subtracted from the values obtained when recombinant cytokines were used, and is indicated on the right.

Immunohistochemical Analysis of EBI3 and p35 Expression throughout Pregnancy

In a previous study, Northern blot analysis indicated that the EBI3 gene is expressed at a very high level in human placenta tissue. In situ hybridization and immunofluorescence staining with affinity-purified polyclonal rabbit EBI3 antibodies showed that EBI3 was expressed by syncytiotrophoblasts in full-term placentae. 8 EBI3 expression in placentae before term and in the decidua had not been investigated. To further delineate EBI3 expression throughout human pregnancy, tissue sections from first-, second-, and third-trimester placentae were analyzed by immunohistochemistry using the 2G4H6 mAb. Placentae ranging from 4 to 41 weeks of gestation from 18 different women were analyzed. In each case, immunohistochemistry was performed on frozen (n = 6) or paraffin-embedded (n = 10) tissues, or both (n = 2). In each case, an isotype-matched control mAb was used in parallel. EBI3 was detected in all cases and a similar pattern of staining was obtained on frozen and paraffin-embedded tissues. No signal was observed with the control mAb (Figure 5A ▶ , and data not shown). Also, for all cases of frozen placental tissue, EBI3 expression was confirmed by Western blotting with EBI3 mAb (data not shown).

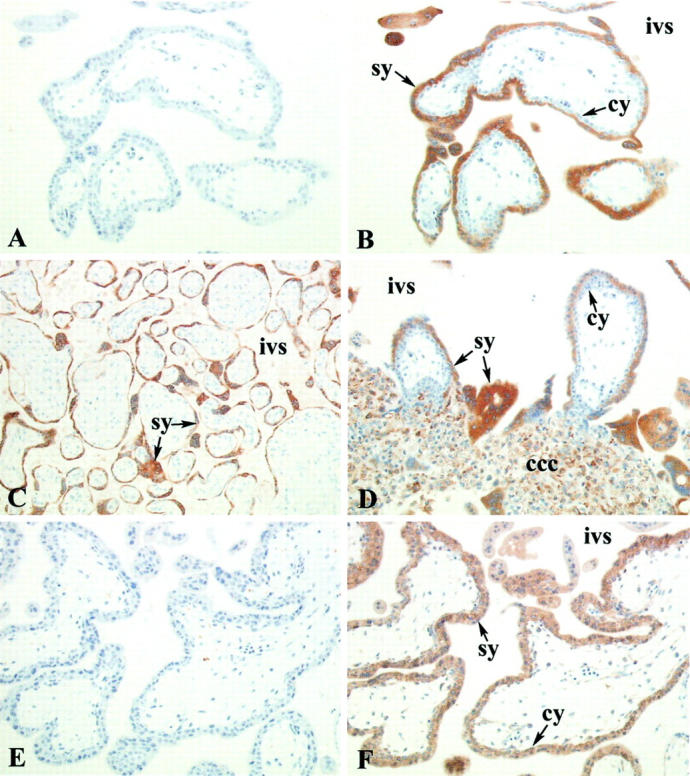

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical analysis of EBI3 and p35 expression in placental villi. Immunostaining of paraffin-embedded sections. Serial sections from floating villi of a 4-week-old placenta stained with isotype-matched control mAb (A) or 2G4H6 mAb (B) showed that syncytiotrophoblasts were specifically labeled with EBI3 mAb, whereas cytotrophoblasts were negative. A similar pattern of EBI3 staining was observed in term placenta (C). Anchoring villi from a 4-week-old placenta stained with EBI3 mAb (D); note that cytotrophoblast cell columns are positive for EBI3. Serial sections from floating villi of a 7-week-old placenta stained with isotype-matched control mAb (E) or p35 mAb (F) indicated that both cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts were specifically labeled with p35. Abbreviations: cy, cytotrophoblast; sy, syncytiotrophoblast; ivs, intervillous space; ccc, cytotrophoblast cell column. Original magnifications: ×250 (A and B); ×200 (C–F).

Immunohistochemical analysis indicated that EBI3 expression was restricted to differentiated trophoblasts. In floating villi, EBI3 expression was primarily restricted to syncytiotrophoblast cells. Regardless of the term, syncytiotrophoblasts were always found to be positive for EBI3, whereas villous cytotrophoblasts were consistently negative (Figure 5, B and C) ▶ . Fetal endothelial cells in the villi were negative in all cases. In two cases, weak staining was observed in Hofbauer cells, the placental macrophages present in chorionic villi. However, because this staining was observed only when immunohistochemistry was performed on frozen sections, and was not detected when immunostaining was performed on paraffin sections from the same placenta, the specificity of this staining was uncertain.

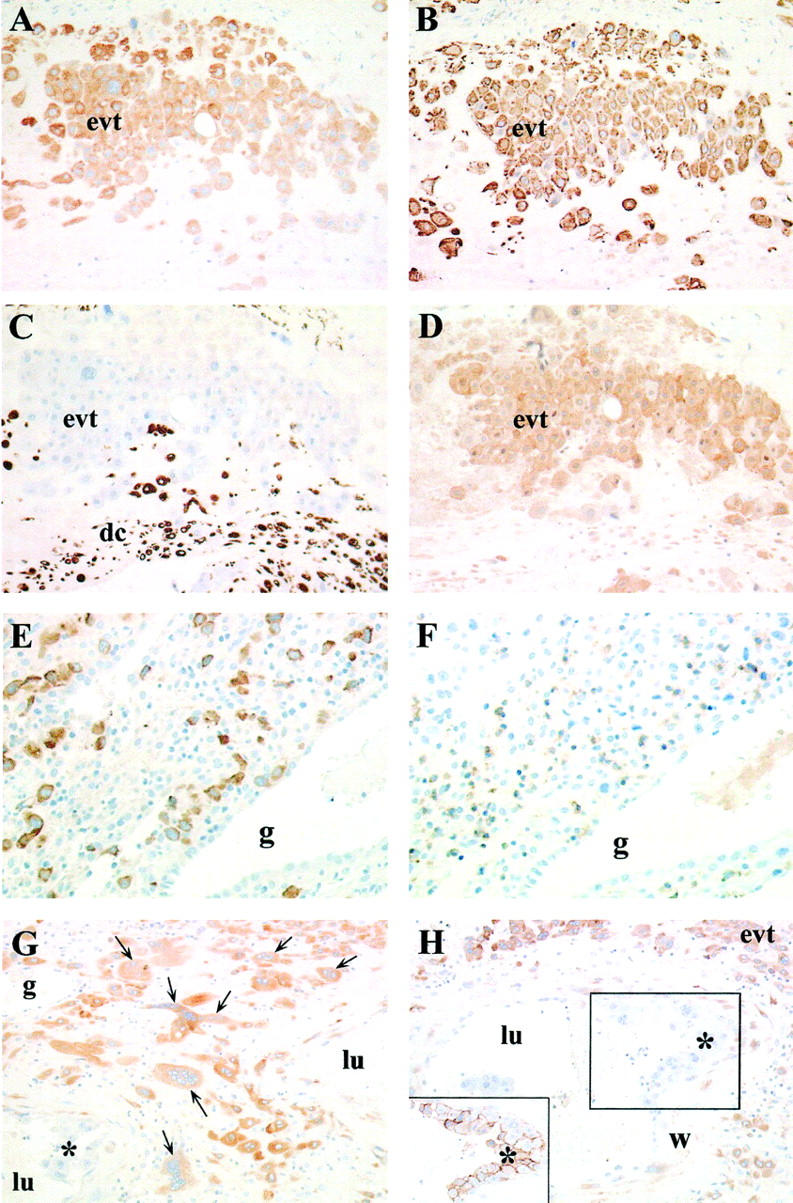

Extravillous trophoblasts showed a heterogeneous pattern of staining with EBI3 mAb. In anchoring villi, cytotrophoblast cell columns showed moderate EBI3 staining (Figure 5D) ▶ . In the decidua, many EBI3-positive cells were detected. These cells had a morphology and location characteristic of extra-villous trophoblasts. To confirm the phenotype of these cells and discriminate trophoblast cells from decidual cells, serial sections were stained with EBI3 mAb, cytokeratin mAb (a marker of trophoblast cells), or vimentin mAb (a marker of decidual cells). Data indicated that EBI3-positive cells expressed cytokeratin, but failed to express vimentin (Figure 6 ▶ ; A to C), providing further evidence that these cells correspond to extra-villous trophoblasts. Similar data were obtained when anti-human placental lactogen antibodies were used as a marker of trophoblast cells (data not shown). These EBI3-positive extravillous trophoblasts were in contact with a large number of maternal CD56-positive NK cells (Figure 6, E and F) ▶ . Multinucleated giant cells were also labeled with EBI3 mAb (Figure 6G) ▶ . Interestingly, whereas invasive trophoblasts surrounding or infiltrating the wall of maternal uterine arteries were positive for EBI3, invasive trophoblasts that had further differentiated into CD56-positive endovascular trophoblasts 19 and were located within the lumen of the arteries showed no or very weak EBI3 expression (Figure 6H) ▶ . No EBI3 staining was observed in the other cell populations present in the decidua, including decidual cells, infiltrating leukocytes, and endometrial glands. Recently, mature dendritic cells have been shown to express EBI3 gene at a high level, 20 and dendritic cells have been identified in the human decidua, where they are predominantly associated with endometrial glands. 21 However, the morphology of EBI3-positive cells in the decidua does not suggest that decidual dendritic cells express EBI3.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemical analysis of the decidua. Immunostaining of paraffin-embedded tissues. Staining of serial sections from the decidua of a 39-week-old placenta with anti-EBI3 mAb (A), anti-cytokeratin mAb (B), anti-vimentin mAb (C), or anti-p35 mAb (D) demonstrated that EBI3- or p35-positive cells are labeled with cytokeratin mAb, but not with vimentin mAb. Staining of serial sections from a 7-week-old placenta with anti-EBI3 mAb (E) or anti-CD56 mAb (F) showed that EBI3-positive interstitial trophoblasts are in close contact with numerous CD56-positive NK cells. G and H: EBI3 staining of the decidua of a 17-week-old placenta. Placental bed multinucleated cells (arrows) are positive for EBI3 (G). Intra-arterial trophoblasts characterized by CD56 expression (inset) are negative for EBI3 (H). Abbreviations: evt, extra-villous trophoblasts; dc, decidual cells; g, uterine gland; w, wall of spiral artery; lu, lumen of spiral artery. Asterisk: intra-arterial trophoblast cells. Original magnifications: ×200 (A–D, G, and H); ×250 (E and F).

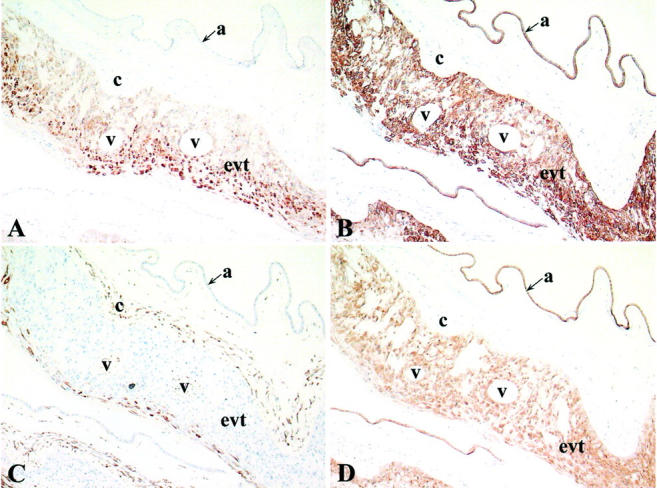

Extra-villous trophoblasts are also present in the chorion laeve of fetal membranes. To investigate whether this peculiar trophoblast population expresses EBI3, paraffin sections from fetal membranes corresponding to four of the placentae studied here (term: 17, 35, 38, and 39 weeks) were analyzed for EBI3 expression (Figure 7) ▶ . In all cases, numerous EBI3-positive cells were observed in the chorion laeve. Serial section analysis indicated that EBI3-positive cells also express cytokeratin, but failed to react with vimentin antibody, consistent with these cells corresponding to trophoblast cells (Figure 7) ▶ . In all cases (villi, decidua, or membranes), EBI3 staining was cytoplasmic. In some interstitial trophoblasts, cytoplasmic staining with strong plasma membrane reinforcement was observed.

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemical analysis of fetal membranes. Serial sections (paraffin-embedded tissues) of fetal membranes collected at delivery (term, 38 weeks) were labeled with anti-EBI3 mAb (A), anti-cytokeratin mAb (B), anti-vimentin mAb (C), or anti-IL-12 p35 mAb (D). EBI3- or p35-positive cells expressed cytokeratin, but failed to express vimentin. Abbreviations: a, amnion epithelium; c, chorionic connective tissue; evt, extra-villous trophoblast cells; v, atrophic ghost villi. Original magnifications, ×100.

Because EBI3 can associate with IL-12 p35, we next investigated whether the trophoblast cell populations found to express EBI3 also expressed p35. Paraffin sections from eight of the placentae previously analyzed for EBI3 expression and representative of first-, second-, and third-trimester placentae (7-, 8-, 17-, 27-, 33-, 35-, 38-, and 39-week placentae) were analyzed for p35 expression by immunohistochemistry using a commercially available specific p35 mAb, G161-566 mAb. In each case, the specificity of staining was verified by using an isotype-matched control mAb in parallel. Immunostaining with p35 mAb showed a broader distribution than immunostaining with EBI3 mAb. Regardless of the placenta term, all subpopulations of villous and extravillous trophoblasts were found to be positive for p35, with a weak to moderate staining intensity. In chorionic villi, both cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts were specifically stained with p35 mAb (Figure 5, E and F) ▶ . In the decidua, all types of extravillous trophoblasts, including cytotrophoblast cell columns, interstitial trophoblasts, multinucleated giant cells, and endovascular trophoblasts were labeled with p35 mAb (Figure 6D ▶ , and data not shown). Extravillous trophoblasts of the chorion laeve were also found to express p35 (Figure 7D) ▶ . Therefore, all of the cell types positive for EBI3 were also positive for p35. However, in contrast to EBI3 expression, p35 expression was not restricted to trophoblast cells, and other cell populations such as fetal endothelial cells, epithelial cells of uterine glands and amnion epithelial cells were labeled with p35 mAb (data not shown and Figure 7D ▶ ).

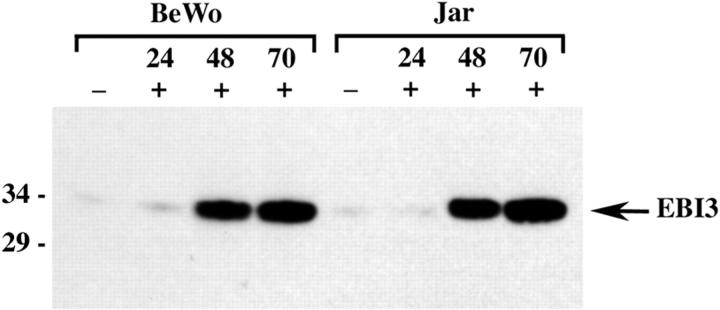

EBI3 Expression Is Up-Regulated during Differentiation in Choriocarcinoma Cell Lines

Immunohistochemical data suggested that EBI3 expression was induced during the differentiation of trophoblast cells. BeWo is a human choriocarcinoma cell line with a cytotrophoblastic phenotype that has been used as a model of trophoblast differentiation in vitro. Stimulation with forskolin has been shown to induce differentiation of the BeWo cell line toward a syncytiotrophoblastic phenotype within 48 to 72 hours of culture. 22 Treatment with PMA was also shown to induce the expression of differentiation markers. 23 Unstimulated BeWo were found to express low amounts of EBI3. Stimulation with forskolin and PMA, alone or in combination, resulted in clear up-regulation of EBI3 expression after 48 hours of stimulation, which was maintained after 70 hours of stimulation, as shown by Western blotting. Similar data were obtained with another choriocarcinoma cell line, the Jar cell line (Figure 8 ▶ , and data not shown). Therefore, as observed in vivo, the in vitro differentiation of trophoblast cells resulted in EBI3 induction.

Figure 8.

Induction of EBI3 expression in choriocarcinoma cell lines. BeWo or Jar cells were left unstimulated (−) or were stimulated (+) with PMA (5.10−8 mol/L for BeWo, and 10−7 mol/L for Jar cells) and forskolin (5.10−6 mol/L for BeWo and 10−5 mol/L for Jar cells) for the time indicated. Cell lysates (50 μg per lane) were then analyzed by immunoblotting with 2G4H6 mAb.

EBI3 Is Secreted from Trophoblast Cells in Vitro and Is Present at High Levels in the Sera of Pregnant Women

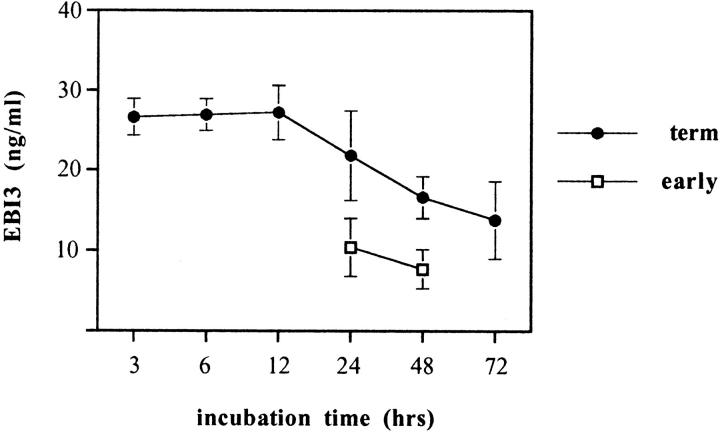

We next investigated whether EBI3 was secreted from trophoblast cells. To this end, we measured by ELISA the amount of EBI3 present in the culture supernatant of placental explants. Supernatants from in vitro explant cultures of first-trimester placentae (n = 7) and term placentae (n = 12) were tested after various times of culture. For both early and term placentae, results were found to be homogeneous between individuals. As shown on Figure 9 ▶ , in the culture supernatant from term placenta explants, large amounts of EBI3 (mean 26.6 ± 2.3 ng) were detected after only 3 hours of culture. These levels were maintained throughout the first 12 hours of culture, and then progressively declined throughout time. EBI3 was also secreted from early placenta explants, although the amount was approximately half the one observed for term placentae (mean of 10.4 ng/ml for early placentae versus 21.8 ng/ml for term placentae at 24 hours of culture, and 7.7 ng/ml versus 16.6 ng/ml at 48 hours of culture). Addition of RU486 to the culture had no effect on EBI3 secretion by trophoblasts in vitro, suggesting that this difference was not because of the different mode by which early and term placentae were obtained (data not shown). Most likely, the larger amount of secreted EBI3 in culture explants from term placentae reflected the higher proportion of syncytiotrophoblasts in villi from term placentae than in villi from early placentae. Altogether, these dataconfirm that EBI3 is secreted by trophoblast cells from both early and term placenta villi.

Figure 9.

EBI3 is secreted by placental explants. Culture supernatants from early (n = 7) or term (n = 12) placentae were harvested at various times of culture and tested by EBI3 ELISA. The mean value (±SD) is represented. Because of the limited amount of material obtained for early placentae, only two time points (24 and 48 hours) were performed.

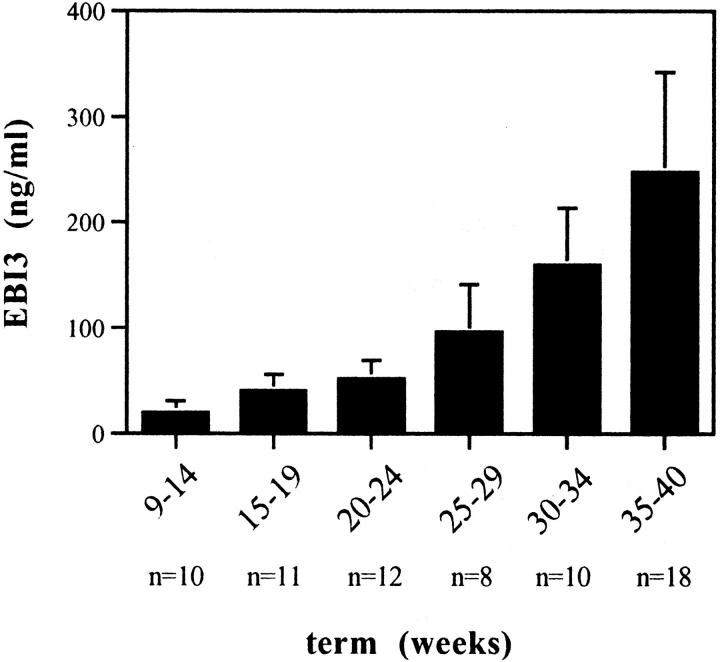

Because EBI3 is continuously expressed in vivo by syncytiotrophoblasts, which are in direct contact with maternal blood, we expected the EBI3 secreted by these cells to be released into and present in maternal blood circulation throughout pregnancy. To verify this hypothesis, we monitored the level of EBI3 in the serum of 10 different pregnant women, collected at various times during pregnancy (from 9 to 40 weeks of pregnancy). As a control, sera from nonpregnant women (n = 10) and men (n = 4) were tested. For the control group, levels of serum EBI3 were below the limit of sensitivity of the assay in 11 cases (all men and 8 of the 10 nonpregnant women), and ranged between 1.3 to 2.8 ng/ml in the other two cases. As shown in Figure 10 ▶ , serum EBI3 concentration had already significantly increased after 2 months of pregnancy (20 ± 11 ng/ml as a mean during the third month of pregnancy), and it continued to increase gradually during pregnancy, reaching levels ranging from 117 to 446 ng/ml in the last 2 months of pregnancy. EBI3 could also be detected by ELISA in urine from pregnant women (data not shown).

Figure 10.

Maternal serum EBI3 levels during normal pregnancy. Sera from 10 different pregnant women, collected at various times during pregnancy, were tested by EBI3 ELISA. The mean value (±SD) is represented. The number of sera tested for each time point is indicated below the graph.

Because our EBI3 ELISA detects both EBI3 and EBI3/p35, we tried to determine the amount of secreted EBI3 associated with p35 in the samples tested above by developing an EBI3/p35-specific ELISA. Using G161-566 p35 mAb or an isotype-matched control mAb as a capture mAb and biotinylated 2G4H6 as a detection mAb, we could specifically detect recombinant EBI3/p35 (detection limit, 0.2 ng/ml). When sera from pregnant women or culture supernatants from placenta explants were tested in this assay, 1 to 5% of the EBI3 (mean, 3.5 ± 2.1) bound nonspecifically to the well coated with the control capture antibody and we could not detect significant amounts of EBI3/p35 heterodimer above the background level observed in this test (data not shown). Therefore, it seems that less than 5%, if any, of the secreted EBI3 present in the serum of pregnant women or in the culture supernatant from placenta explants, is associated with p35 under the experimental conditions used here.

Discussion

This work provides the first detailed analysis of EBI3 expression in human pregnancy. Altogether, our data indicate that EBI3 is expressed at high levels throughout normal pregnancy. Immunohistochemical analysis of placenta and placenta bed sections from various terms, from 4 weeks of pregnancy to the term, demonstrated that EBI3 is expressed at all gestational ages. EBI3 expression was restricted to differentiated trophoblast cells. Both villous syncytiotrophoblasts and extravillous cytotrophoblasts, including cytotrophoblast cell columns, interstitial trophoblasts, multinucleated placental bed giant cells, and trophoblasts of the chorion laeve were found to express EBI3. Consistent with these in vivo observations, trophoblast cell lines were shown to up-regulate EBI3 expression after differentiation in vitro. Interestingly, whereas trophoblasts invading the wall of uterine spiral arteries expressed EBI3, intra-arterial trophoblast cells had down-regulated EBI3 expression. These data indicate that EBI3 expression by trophoblast cells in vivo is tightly regulated.

Our data also provide the first evidence that EBI3 is secreted under physiological conditions. In previous studies, secreted EBI3 was detected only in the culture supernatant from transfected cells overexpressing EBI3. 8,9 In this work, we showed by ELISA that placental explants secreted large amounts of EBI3, with mean values of 26.6 to 27.2 ng/ml during the first 12 hours of culture for term placenta explants. For comparison, EBV-transformed B cell lines, which were identified by Northern blot and immunoblot analysis among the cell lines expressing the largest amounts of EBI3, secreted 2.2 ng/ml as a mean (n = 6) (OD and FC, unpublished results). We also showed that very high levels of EBI3 were present in peripheral blood from pregnant women, and that EBI3 serum levels gradually increased with gestational age. To our knowledge, no cytokine or soluble cytokine receptor, specifically up-regulated during pregnancy, has been detected at such high levels in maternal blood. The gradual increase in the amount of EBI3 in maternal blood most likely reflects the increase in placenta size and the morphological changes resulting in an increase in the proportion of syncytiotrophoblasts in chorionic villi during the course of pregnancy.

In contrast to EBI3 and IL-12 p40, the expression of which is inducible and tissue-specific, IL-12 p35 has been reported to be constitutively expressed at low levels in most cell types. 24 Immunohistochemistry showed that all of the cell types positive for EBI3 were also positive for p35. However, despite the in situ detection of p35 in trophoblast cells, we did not detect significant levels of secreted EBI3/p35 above the background level observed in our ELISA, in placental culture explants or in the sera from pregnant women. This may be because of a small amount of EBI3 complexed with p35 and excess free EBI3 secretion, as has been reported for IL-12 p40 that is produced both in vitro and in vivo in a large excess over the p35/p40 heterodimer (5-fold to 1000-fold excess over the amount of IL-12 heterodimer). 10 Alternatively, it may be because of a lower stability and shorter half-life of the heterodimer than of the free form. Also, because EBI3 was previously found not to be efficiently secreted when expressed alone, EBI3 may be associated with another, as yet unidentified, partner. Recently, IL-12 p40 was shown to associate not only with p35, but also with a p19 protein to form a novel heterodimeric cytokine, p19/p40 (IL-23). 25 Similarly, EBI3 may associate with a second cytokine partner.

Successful pregnancy has been associated with a Th2-type of cytokine production, 14-17 and the high level of EBI3 expression in normal pregnancy suggests that this molecule is associated with a Th2 response. Previous analysis of EBI3 expression in vivo suggested that its expression pattern contrasted with that of IL-12. 18 Similarly, in pregnancy, EBI3 and IL-12 or IL-12 p40 seem to be differentially regulated. Whereas large amounts of EBI3 are present in normal pregnancy, no significant amounts of IL-12 or IL-12 p40 have been detected. Indeed, no IL-12 was detected in explant cultures from early or term placentae 26 similarly, IL-12 p40 was primarily undetectable in explant cultures from early and term placentae (low levels were detected in only 1 of 19 cases, OD and FC, unpublished data). Also, in sera from women with normal pregnancies, IL-12 or IL-12 p40 levels are very low or undetectable, whereas they are up-regulated in pathological pregnancies such as severe pre-eclampsia or hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet counts (HELLP) syndrome. 27

Our data indicate that EBI3 is expressed at high levels by extravillous cytotrophoblasts infiltrating the uterine decidua. These cells do not express HLA-A and HLA-B, but instead express high levels of HLA-G, a nonclassical class I molecule, 28,29 and are in contact with a large number of NK cells that have infiltrated the decidua in response to trophoblast invasion. Local interaction between NK cells and invasive extravillous trophoblasts has been assumed to contribute to maternal tolerance. In this line, HLA-G expression has been shown to protect cells from NK cell-mediated lysis, via HLA-G interaction with specific receptors on NK cells. 2 Decidual NK cells differ in morphology and phenotype from peripheral NK cells, and express a specific set of inhibitory receptors that bind MHC class I antigens. They notably express two inhibitory NK cell receptors that can directly interact with HLA-G: ILT2/LIR1 and KIR2DL4. 30-34 KIR2DL4 is a member of the KIR family that exclusively interacts with HLA-G, 31 whereas ILT2 interacts with several HLA class I molecules. 30,35 Both ILT2 and KIR2DL4 are expressed by a subset of decidual NK cells during the first trimester of pregnancy, and are expressed on the majority of NK cells in term placenta. 33 In addition, ILT2 expression on peripheral blood maternal NK cells is up-regulated during pregnancy. 33 Both KIR2DL4 and ILT2 have been shown to protect cells expressing HLA-G from NK cell lysis. 30,31,33,35 HLA-G displays limited polymorphism but, like conventional MHC class I molecules, is capable of binding peptides and is expressed at the cell surface as a trimolecular complex composed of HLA-G associated with β2-microglobulin and a 9-amino acid peptide. 36,37 It can also exist as a soluble form, and data indicate that soluble HLA-G molecules are produced by trophoblasts and are detected in maternal blood during pregnancy. 38-40 Using EBV-transformed B cell lines stably expressing HLA-G, peptides complexed with membrane-bound and soluble forms of HLA-G have been purified and sequenced. 36,37 Interestingly, EBI3 was identified among the most abundant peptides presented by both soluble and membrane-bound HLA-G molecules. 36 Given that extravillous trophoblasts, like EBV-transformed B cells, express high levels of EBI3 and the evidence that the peptides eluted from transfectants are representative of the peptides presented in vivo, 36 EBI3 peptides are likely to be presented in vivo by trophoblast HLA-G. The recognition of MHC class I complex by KIR molecules and the subsequent inhibition of NK cells have been shown to be peptide-dependent. 41-43 Therefore, EBI3 peptide may be involved in HLA-G/NK cell receptor interaction in the decidua or in maternal peripheral blood and may contribute to maternal tolerance.

Functions other than cytotoxicity can also be regulated by NK/trophoblast cell interaction, including cytokine production, proliferation, and regulation of trophoblast differentiation and invasion. 2,3,44,45 The role of EBI3 in these effects remains to be established.

Another important function of invasive extravillous trophoblasts is to invade the walls of the maternal uterine spiral arteries and replace maternal endothelial cells. This vascular transformation converts vessels into larger vessels with a low resistance, which can therefore provide efficient oxygenated maternal blood supply to the intervillous space and to the developing placenta and fetus. Defective trophoblast invasion and vascular transformation are responsible for a number of types of pathological pregnancies including pre-eclampsia and unexplained intrauterine growth retardation. Several cytokines expressed by trophoblasts, such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β3, have been shown to display an abnormal expression in pre-eclampsia, and have been linked to development of the disease. 46,47 Because EBI3 expression by extravillous trophoblasts seems to be tightly regulated, the role of EBI3 in these pathological conditions needs to be investigated.

Identification of the function of EBI3 and investigation of its possible deregulated expression in pathological pregnancies should elucidate the role of EBI3 in human pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gérard Chaouat for critical review of the manuscript; Prof. René Frydman and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Hôpital Antoine Béclère) for placentae; Dr. Liliane Keros (Hôpital Antoine Béclère) for sera; and Laurent Berthier for providing excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Odile Devergne, CNRS UMR 8603, Hôpital Necker, 161 rue de Sèvres, 75 015 Paris, France. E-mail: devergne@necker.fr.

Supported in part by a grant from the Association de Recherche contre le Cancer (to O. D.).

References

- 1.Loke YW, King A: Immunological aspects of human implantation. J Reprod Fertil 2000, 55(Suppl):S83-S90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Bouteiller P, Solier C, Pröll J, Aguerre-Girr M, Fournel S, Lenfant F: Placental HLA-G protein expression in vivo: where and what for? Human Reprod 1999, 5:223-233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King A, Hiby SE, Gardner L, Joseph S, Bowen JM, Verma S, Burrows TD, Loke YW: Recognition of trophoblast HLA class I molecules by decidual NK cell receptors. A review. Placenta 2000, 14(Suppl A):S81-S85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roth I, Corry DB, Locksley RM, Abrams JS, Litton MJ, Fisher SJ: Human placental cytotrophoblasts produce the immunosuppressive cytokine interleukin 10. J Exp Med 1996, 184:539-548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dealtry GB, Clark DE, Sharkey A, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith SK: Expression and localization of the Th2-type cytokine interleukin-13 and its receptor in the placenta during human pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol 1998, 40:283-290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selick CE, Horowitz GM, Gratch M, Scott RT, Navot D, Hofmann GE: Immunohistochemical localization of transforming growth factor-beta in human implantation sites. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994, 78:592-596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jokhi PP, King A, Loke YW: Cytokine production and cytokine receptor expression by cells of the human first trimester placental-uterine interface. Cytokine 1997, 9:126-137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devergne O, Hummel M, Koeppen H, Le Beau M, Nathanson EC, Kieff E, Birkenbach M: A novel interleukin-12 p40 related protein induced by latent Epstein-Barr virus infection in B lymphocytes. J Virol 1996, 70:1143-1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devergne O, Birkenbach M, Kieff E: Epstein-Barr virus induced gene 3 and the p35 subunit of interleukin 12 form a novel heterodimeric hematopoietin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997, 94:12041-12046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trinchieri G: Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 1995, 13:251-276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szabo SJ, Jacobson NG, Dighe AS, Gubler U, Murphy KM: Developmental commitment to the Th2 lineage by extinction of IL-12 signaling. Immunity 1995, 2:665-675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magram J, Connaughton SE, Warrier RR, Carvajal DM, Wu CY, Ferrante J, Stewart C, Sarimiento U, Faherty DA, Gately MK: IL-12 deficient mice are defective in IFN-γ production and type 1 cytokine responses. Immunity 1996, 4:471-481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rickinson AB, Moss DJ: Human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to Epstein-Barr virus infection. Annu Rev Immunol 1997, 15:405-431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wegmann TG, Lin H, Guilbert L, Mossman TR: Birectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a Th2 phenomenon? Immunol Today 1993, 14:353-356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill JA, Polgar K, Anderson DJ: T-helper 1-type immunity to trophoblast in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. J Am Med Assoc 1995, 273:1933-1936 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piccinni MP, Beloni L, Livi C, Maggi E, Scarselli G, Romagnani S: Defective production of both leukemia inhibitory factor and type 2 T-helper cytokines by decidual T cells in unexplained recurrent abortions. Nat Med 1998, 4:1020-1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill JA, Choi BC: Maternal immunological aspects of pregnancy success and failure. J Reprod Fertil 2000, 55(Suppl):S91-S97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christ AD, Stevens AC, Koeppen H, Walsh S, Omata F, Devergne O, Birkenbach M, Blumberg RS: An interleukin 12-related cytokine is up-regulated in ulcerative colitis but not in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 1998, 115:307-313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proll J, Blaschitz A, Hartmann M, Thalhamer J, Dohr G: Human first-trimester placenta intra-arterial trophoblast cells express the neural cell adhesion molecule. Early Pregnancy 1996, 2:271-275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto SI, Suzuki T, Nagai S, Yamashita T, Toyoda N, Matsushima K: Identification of genes specifically expressed in human activated and mature dendritic cells through serial analysis of gene expression. Blood 2000, 96:2206-2214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kämmerer U, Schoppet M, McLellan AD, Kapp M, Huppertz HI, Kämpgen E, Dielt J: Human decidua contains potent immunostimulatory CD83+ dendritic cells. Am J Pathol 2000, 157:159-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wice B, Menton D, Geuze H, Schwartz AL: Modulators of cyclic AMP metabolism induce syncytiotrophoblast formation in vitro. Exp Cell Res 1990, 186:306-316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamawaki T, Toyoda N: Human chorionic gonadotrophin secretion and protein phosphorylation in chorionic tissue. Endocr J 1994, 41:509-516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Andrea A, Rengaraju M, Valiante NM, Chemini J, Kubin M, Aste M, Chan SH, Kobayashi M, Young D, Nickbarg E, Chizzonite R, Wolf SF, Trinchieri G: Production of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (interleukin 12) by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Exp Med 1992, 176:1387-1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oppmann B, Lesley R, Blom B, Timans JC, Xu Y, Hunte B, Vega F, Yu N, Wang J, Singh K, Zonin F, Vaisberg E, Churakova T, Liu M, Gorman D, Wagner J, Zurawsky S, Liu YJ, Abrams JS, Moore KW, Rennick D, de Waal-Malefyt R, Hannum C, Bazan JF, Kastelein RA: Novel p19 protein engages IL-12 p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity 2000, 13:715-725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moussa M, Roques P, Fievet N, Menu E, Maldonado-Estrada JF, Brunerie J, Frydman R, Fritel X, Hervé F, Chaouat G: Placental cytokine and chemokine production in HIV-1 infected women: trophoblast cells show a different pattern compared to cells from HIV-negative women. Clin Exp Immunol 2001, 125:455-464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudley DJ, Hunter C, Mitchell MD, Varner MW, Gately M: Elevations of serum interleukin-12 concentrations in women with severe-preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome. J Reprod Immunol 1996, 31:97-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMaster MT, Librach CL, Zhou Y, Lim KH, Janatpour MJ, DeMars R, Kovats S, Damsky C, Fisher SJ: Human placental HLA-G expression is restricted to differentiated cytotrophoblasts. J Immunol 1995, 154:3771-3778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loke YW, King A, Burrows T, Gardner L, Bowen M, Hiby S, Howlett S, Holmes S, Jacob D: Evaluation of trophoblast HLA-G antigen with a specific monoclonal antibody. Tissue Antigens 1997, 50:135-146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colonna M, Navarro F, Bellon T, Llano M, Garcia P, Samaridis J, Angman L, Cella M, Lopez-Botet M: A common inhibitory receptor for major histocompatibility complex class I molecules on human lymphoid and myelomonocytic cells. J Exp Med 1997, 186:1809-1818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajagopalan S, Long EO: A human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-G-specific receptor expressed on all natural killer cells. J Exp Med 1999, 189:1093-1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navarro F, Llano M, Bellon T, Colonna M, Geraghty DE, Lopez-Botet M: The ILT2(LIR1) and CD94/NKG2A NK cell receptors respectively recognize HLA-G1 and HLA-E molecules co-expressed on target cell. Eur J Immunol 1999, 29:277-283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponte M, Cantoni C, Biassoni R, Tradori-Cappai A, Bentivoglio G, Vitale C, Bertone S, Moretta A, Moretta L, Mingari MC: Inhibitory receptors sensing HLA-G1 molecules in pregnancy: decidua-associated natural killer cells express LIR-1 and CD94/NKG2A and acquire p49, an HLA-G1-specific receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:5674-5679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lanier LL: Natural killer cells fertile with receptors for HLA-G? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:5343-5345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vitale M, Castriconi R, Parolini S, Pende D, Hsu ML, Moretta L, Cosman D, Moretta A: The leukocyte Ig-like receptor (LIR)-1 for the cytomegalovirus UL18 protein displays a broad specificity for different HLA class I alleles: analysis of LIR-1 + NK cell clones. Int Immunol 1999, 11:29-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee N, Malacko AR, Ishitani A, Chen MC, Bajorath J, Marquardt H, Geraghty DE: The membrane-bound and soluble forms of HLA-G bind identical sets of endogenous peptides but differ with respect to TAP association. Immunity 1995, 3:591-600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diehl M, Münz C, Keilholz W, Stevanovic S, Holmes N, Loke YW, Rammensee HG: Nonclassical HLA-G molecules are classical peptide presenters. Curr Biol 1996, 6:305-314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chu W, Fant ME, Geraghty DE, Hunt JS: Soluble HLA-G in human placentas: synthesis in trophoblasts and interferon-gamma-activated macrophages but not placental fibroblasts. Hum Immunol 1998, 59:435-442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hunt JS, Jadhav L, Chu W, Geraghty DE, Ober C: Soluble HLA-G circulates in maternal blood during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000, 183:682-688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puppo F, Costa M, Contini P, Brendi S, Cevasco E, Ghio M, Norelli R, Bensussan A, Capitanio GL, Indiveri F: Determination of soluble HLA-G and HLA-A, -B, and -C molecules in pregnancy. Transplant Proc 1999, 31:1841-1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malnati MS, Peruzzi M, Parker KC, Biddison WE, Ciccone E, Moretta A, Long EO: Peptide specificity in the recognition of MHC class I by natural killer cell clones. Science 1995, 267:1016-1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peruzzi M, Parker KC, Long EO, Malnati MS: Peptide sequence requirements for the recognition of HLA-B*2705 by specific natural killer cells. J Immunol 1996, 157:3350-3356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajagopalan S, Long EO: The direct binding of a p58 killer cell inhibitory receptor to human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw4 exhibits peptide selectivity. J Exp Med 1997, 185:1523-1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loke YW, King A: Decidual natural-killer-cell interaction with trophoblast: cytolysis or cytokine production? Biochem Soc Trans 2000, 28:196-198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bischof P, Meisser A, Campana A: Paracrine and autocrine regulators of trophoblast invasion—a review. Placenta 2000, 14(Suppl A):S55-S60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hennessy A, Pilmore HL, Simmons LA, Painter DM: A deficiency of placental IL-10 in preeclampsia. J Immunol 1999, 163:3491-3495 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caniggia I, Grisaru-Gravnosky S, Kuliszewsky M, Post M, Lye SJ: Inhibition of TGF-β3 restores the invasive capability of extravillous trophoblasts in preeclamptic pregnancies. J Clin Invest 1999, 103:1641-1650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]