Abstract

Interindividual gene copy-number variation (CNV) of complement component C4 and its associated polymorphisms in gene size (long and short) and protein isotypes (C4A and C4B) probably lead to different susceptibilities to autoimmune disease. We investigated the C4 gene CNV in 1,241 European Americans, including patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), their first-degree relatives, and unrelated healthy subjects, by definitive genotyping and phenotyping techniques. The gene copy number (GCN) varied from 2 to 6 for total C4, from 0 to 5 for C4A, and from 0 to 4 for C4B. Four copies of total C4, two copies of C4A, and two copies of C4B were the most common GCN counts, but each constituted only between one-half and three-quarters of the study populations. Long C4 genes were strongly correlated with C4A (R=0.695; P<.0001). Short C4 genes were correlated with C4B (R=0.437; P<.0001). In comparison with healthy subjects, patients with SLE clearly had the GCN of total C4 and C4A shifting to the lower side. The risk of SLE disease susceptibility significantly increased among subjects with only two copies of total C4 (patients 9.3%; unrelated controls 1.5%; odds ratio [OR] = 6.514; P=.00002) but decreased in those with ⩾5 copies of C4 (patients 5.79%; controls 12%; OR=0.466; P=.016). Both zero copies (OR=5.267; P=.001) and one copy (OR=1.613; P=.022) of C4A were risk factors for SLE, whereas ⩾3 copies of C4A appeared to be protective (OR=0.574; P=.012). Family-based association tests suggested that a specific haplotype with a single short C4B in tight linkage disequilibrium with the −308A allele of TNFA was more likely to be transmitted to patients with SLE. This work demonstrates how gene CNV and its related polymorphisms are associated with the susceptibility to a human complex disease.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE [MIM 152700]) is a complex, prototypic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects women of child-bearing age. The hallmark of SLE is the generation of autoantibodies that react with self nuclear and cytoplasmic antigens, culminating in immunologic attacks to body organs.1–3 Although under intense investigations, the genetic basis of human SLE is still not well understood.4–6

Complement component C4 (with isotopes C4A [MIM 120810] and C4B [MIM 120820]) is an effector protein of the immune system. It plays a pivotal role in the activation of the classical and the lectin complement pathways that lead to cytolysis or neutralization of invading microbes, opsonization of targets for phagocytosis, clearance of immune complexes, disposal of apoptotic materials, and reduction of the threshold for activation of B lymphocytes.7–11 The link between the total deficiency of complement component C4 and human SLE was first observed in 1974.12 It is known that complete or homozygous deficiency in any of the early components for the classical activation pathway of the complement system, such as C1q (MIM 120550, 120570, and 120575), C1r (MIM 216950), C1s (MIM 120580), and C4, are among the strongest genetic risk factors associated with human SLE. More than 75% of human subjects completely deficient in C1 or C4 proteins have SLE or lupus-like disease.13,14 Animal studies confirmed that homozygous deficiencies of C1q or C4 in mice can be causative genetic factors for SLE.15–18 However, the prevalence of complete deficiency of C4 or subunit proteins of the C1 complex in humans is extremely rare: only 84 cases have been reported so far.11,14,19,20 Much more common is the low plasma or serum protein levels of these complement proteins, particularly C4 or one of its isotypes, C4A.21,22 These abnormalities are present in 30%–40% of patients with SLE.20,23 Curiously, in many healthy subjects, the low range of C4 plasma protein concentrations overlaps that of patients with SLE. The complex genetics of human C4 has precluded a simple interpretation of the mechanism for low C4 protein levels in health and SLE.

The polymorphic C4 proteins are categorized into two isotypes, C4A and C4B, each with multiple allotypes.10,24,25 The C4A and C4B proteins exhibit marked differences in chemical reactivities to substrates, although they share >99% amino acid sequence identity. The isotype-specific residues are encoded by exon 26 and are located at amino acid residues 1101–1106, which are PCPVLD for C4A and LSPVIH for C4B (differences underlined).26–28 The thioester bond present in the activated C4A has a longer half-life against hydrolysis (∼10 s) than that of C4B (<1 s). The thioester carbonyl group of C4A effectively forms a covalent amide bond with amino group–containing substrates, such as protein antigens. The activated C4B is highly reactive because one of its isotypic residues, His 1106, catalyzes a nucleophilic attack of the thioester carbonyl group on hydroxyl group–containing substrates to form a covalent ester linkage.29–32 Therefore, it is thought that C4A proteins are more important in immunoclearance and that C4B proteins are more relevant in the defense against microbes.

The impetus for the present study is that our earlier work in healthy European Americans revealed an interindividual variation in the C4 gene copy number (GCN) and dichotomies of C4 gene size and C4 protein isotypes.33–38 In the central region of the human major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on each chromosome 6 (fig. 1), there can be 1, 2, 3, or 4 copies of C4 genes. Theoretically, two to eight copies of C4 genes can be present in a diploid genome of a given individual. The C4 gene size has two forms, long and short. The long gene is 21 kb in length, and the short gene is 14.6 kb. The long gene is due to the integration of the endogenous retrovirus HERV-K(C4) into its ninth intron.10,37,42 Our earlier analysis revealed that, among subjects with equal copy numbers of C4 genes, subjects with short genes have C4 plasma protein levels relatively higher than those of subjects with long genes.43 Irrespective of gene size, each C4 gene can code for either an acidic C4A protein or a basic C4B protein.

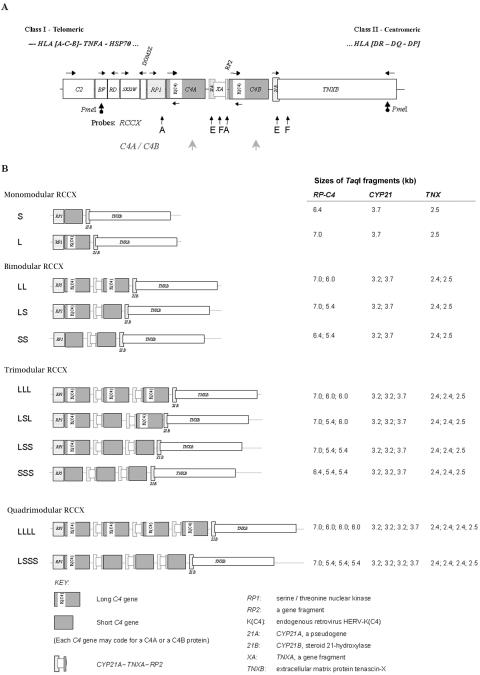

Figure 1. .

CNVs and size variations of complement C4 genes and RCCX modules in the human MHC. A, Map showing the gene organization of the MHC-complement gene cluster with a bimodular LL haplotype for RCCX. Horizontal arrows represent gene transcriptional orientations. The PmeI restriction sites flanking the RCCX modules in BF and TNXB are shown as dotted arrows. Vertical arrows with letters depict the locations and names of DNA probes employed for genomic Southern-blot analyses. B, Structures and configurations of RCCX length variants observed in the white study populations. The fragment sizes of TaqI restriction fragments for RP-C4, CYP21, and TNX are shown on the right.39–41

The duplication or multiplication of C4 genes is discretely modular. The breakpoint(s) of duplication are identical among duplicated modules.33,34 Each duplicated module also includes three genes neighboring C4. In MHC haplotypes with a single C4 gene, there are single and intact genes coding for the nuclear protein kinase RP1 (RP1, also known as “STK19” [MIM 604977]) at the 5′ region, the steroid cytochrome P450 21-hydroxylase (CYP21B, also known as “CYP21A1” [MIM 201910]), and the extracellular matrix protein tenascin-X (TNXB [MIM 600985]) at the 3′ region of C4. In MHC haplotypes with two or more C4 genes, concurrently present with each duplicated C4 gene are a complete sequence for CYP21 and partial sequences for TNX (i.e., TNXA) and RP (i.e., RP2). The duplicated C4 genes are usually functional, and they can code for either a C4A protein or a C4B protein. The additional CYP21 gene can be a nonfunctional CYP21A (also known as CYP21A1P) with multiple sequence alterations, including three deleterious nonsense mutations, or a functional CYP21B gene (see GenBank for entries of sequences of specific genes).33,34,44–46 This phenomenon is referred to as the “RCCX modular duplication.”34,35

To investigate the complex genetic diversity of complement C4, we genotyped the RCCX modules and determined the gene copy-number variation (CNV) of total C4, C4A, C4B, and the long and short C4 genes in patients with SLE, their first-degree relatives, and unrelated healthy controls. The genotype data were independently confirmed by phenotyping experiments that elucidated the C4A and C4B protein polymorphisms in EDTA plasma (i.e., plasma collected in EDTA). Our primary goal was to determine whether total C4 (i.e., C4A plus C4B), C4A, and/or C4B CNVs are genetic risk factors for SLE. The results provide concrete data of gene CNV for an important immune-defense protein in health and disease, suggesting that low copy number is a risk factor for and high copy number is a protective factor against susceptibility to human SLE.

Material and Methods

Study Populations

The protocols for human subject recruitment and study were approved by institutional review boards of the Ohio State University, the Columbus Children’s Hospital, and the University of California–Los Angeles. To avoid confounding factors affecting C4 genetics among different racial and/or ethnic groups, the current report focuses primarily on patients with SLE who are Americans of European ancestry (n=233), their first-degree relatives (n=362), and unrelated healthy European Americans (n=517) residing in central Ohio. The patients all satisfied four or more diagnostic criteria for SLE from the American College of Rheumatology.47 The mean age (±SD) of the female patients with SLE (n=216), female first-degree relatives (n=221), male patients with SLE (n=17), and male first-degree relatives (n=142) was 41.2±14.9 years, 57.7±14.9 years, 38.2±15.4 years, and 58.0±15.6 years, respectively. The mean age of unrelated, healthy, European American female (n=389) and male (n=128) controls was 38.6 ± 11.1 years and 34.3 ± 12.1 years, respectively (table 1).

Table 1. .

Demographic Data of Ohio SLE Cohort[Note]

| Group | No. of Subjects | Agea (years) |

BMIa |

| Female patients with SLE | 216 | 41.2 ± 14.9 | 29.0 ± 7.4 |

| First-degree relatives: | |||

| Female | 221 | 57.7 ± 14.9 | 29.6 ± 8.4 |

| Male | 142 | 58.0 ± 15.6 | 29.2 ± 5.7 |

| Male patients with SLE | 17 | 38.2 ± 15.4 | 29.1 ± 6.6 |

Note.— Cohort also included 517 unrelated, healthy European American controls (389 females and 128 males).

Data are mean ± SD.

An independent replication study was performed using 128 patients with SLE: 99 European American patients (89 females with mean age 37.4±11.6 years; 10 males with mean age 40.9±13.0 years) from Los Angeles and 29 female patients with white European ancestry (mean age 46.6±13.0 years) from the Antiphospholipid Syndrome Registry Collaborative Registry (APSCORE). The APSCORE patients had SLE and antiphospholipid antibodies but did not receive a diagnosis of definite or expanded antiphospholipid syndrome. The clinical characteristics of the patients with SLE who are from Ohio and California are summarized in table 2.

Table 2. .

Clinical Features of Patients with SLE Related to American College of Rheumatology Criteria for Diagnosis of SLE

| Frequency of Criterion(%) |

||

| Diagnostic Criterion | Ohio SLE Study (n=233)a |

California SLE Study (n=99)b |

| Malar rash | 50.9 | 59.6 |

| Discoid rash | 7.63 | 14.3 |

| Photosensitivity | 32.2 | 81.4 |

| Oral ulcer | 31.4 | 42.2 |

| Arthritis | 83.1 | 94.9 |

| Serositis | 31.4 | 55.2 |

| Renal disorder | 36.4 | 31.6 |

| Neurologic disorder | 12.7 | 12.4 |

| Hematologic disorder: | 37.3 | 53.8 |

| Hemolytic anemia | 8.05 | 10.4 |

| Leukopenia | 13.6 | 38.2 |

| Lymphopenia | 9.75 | 30.3 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 14.0 | 18.1 |

| Immunologic disorder: | 43.2 | 74.0 |

| Anti-DNA | 43.6 | 61.1 |

| Anti-Sm | 6.78 | 9.72 |

| Antinuclear antibody | 91.1 | 100 |

Included 17 males and 216 females (males:females 1:12.7).

Included 10 males and 89 females (males:females 1:8.9).

Processing of Blood Samples

EDTA plasma was harvested by centrifugation and was stored at −86°C. Peripheral blood leukocytes were prepared via Ficoll gradient centrifugation for preparation of DNA plugs in low-gelling-temperature agarose and were used for long-range mapping experiments involving pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Genomic DNA samples for RFLP analyses were prepared from whole blood by use of Puregene kits (Gentra Systems).39

Determination of GCN and Gene Size of C4A, C4B, and RCCX Modular Variations

Elsewhere, we have described detailed procedures for genotyping and phenotyping of complement C4.40,41 TaqI genomic RFLP was performed employing specific probes A, E, and F (fig. 1A), corresponding to the genomic regions containing RP, C4, CYP21, and TNX. Results of the TaqI Southern blots yielded information on the GCN and gene size of C4 and the copy numbers of three other constituent genes in the RP-C4-CYP21-TNX (RCCX) modules in the central region of the MHC on chromosome 6p21.3. The relative GCN of C4A and C4B were determined by PshAI-PvuII genomic RFLP that distinguished the C4A and C4B isotypic sites.

Determination of RCCX Haplotype and Number and Size of C4 Genes on Each Chromosome 6 by PFGE of PmeI-Digested DNA

To confirm further the presence of quadrimodular, trimodular, bimodular, and monomodular RCCX structures present in each individual, human genomic DNA trapped in agarose plugs (to avoid shearing and mechanical breakage) was digested with the rare-cutter restriction enzyme PmeI, was subjected to PFGE, and then underwent Southern-blot analysis. The RCCX modular structures were represented as PmeI restriction fragments of the following sizes: monomodular short (S), 107 kb; monomodular long (L), 113 kb; bimodular short-short (SS), 133 kb; bimodular long-short (LS), 139 kb; bimodular long-long (LL), 146 kb; trimodular long-short-short (LSS), 165 kb; trimodular long-short-long (LSL) or long-long-short (LLS), 172 kb; trimodular long-long-long (LLL), 179 kb; quadrimodular long-short-short-short (LSSS), 192 kb; and quadrimodular long-long-long-long (LLLL), 211 kb.41

Determination of C4A and C4B Allotypes and Plasma Protein Concentrations

EDTA plasma samples were digested with neuraminidase and carboxyl peptidase B, followed by (nonreducing) high-voltage agarose-gel electrophoresis.48,49 Complement C4A and C4B allotypes were revealed by immunofixation by use of goat anti-human C4 antibody and staining with Simple Blue dye (Invitrogen). Protein band intensities for C4A and C4B allotypes were quantified by ImageQuant software (Amersham). Plasma protein levels of total C4 were determined by single radial immunodiffusion (The Binding Site). C4A and C4B protein concentrations were calculated from their relative quantities revealed by immunofixation experiments.

Statistical Analyses

χ2 analyses were performed to determine the differences in total C4, C4A, and C4B gene CNV among various groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the gene-copy indices of total C4, C4A, C4B, and long and short C4 across three or more groups; analysis was adjusted for dependence based on data for families with SLE, and Tukey “Honestly Significantly Different” test, performed at the 0.05 significance level, was used to distinguish different clusters of groups. Two-group comparisons for these data were based on post hoc two-sample Student’s t tests. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were calculated by analysis of 2×2 tables, and Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison. Statistical analyses were performed on SAS JMP version 6 (SAS Institute) and SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS) software. Transmission/disequilibrium tests of complement C4A, C4B, and RCCX haplotypes in families with SLE were performed using the computer program FBAT.50

Results

Genetic Mechanisms Leading to Lower Expression of C4A Protein Than of C4B Protein in Families with SLE

The prospective SLE study population consisted entirely of European Americans residing in Ohio. There were 233 patients with SLE, 362 first-degree relatives (parents and siblings) of the patients with SLE, and 517 unrelated healthy controls. The RCCX modular structures and the copy number of long and short C4 genes were elucidated by Southern-blot analyses of PmeI-digested genomic DNA resolved by PFGE and by TaqI genomic RFLP (fig. 1A). The relative GCN of C4A and C4B were determined by genomic PvuII-PshAI RFLP that distinguished C4A and C4B isotypic sequences. The C4A and C4B protein polymorphisms were determined by immunofixation of EDTA plasma resolved by high-voltage agarose-gel electrophoresis.

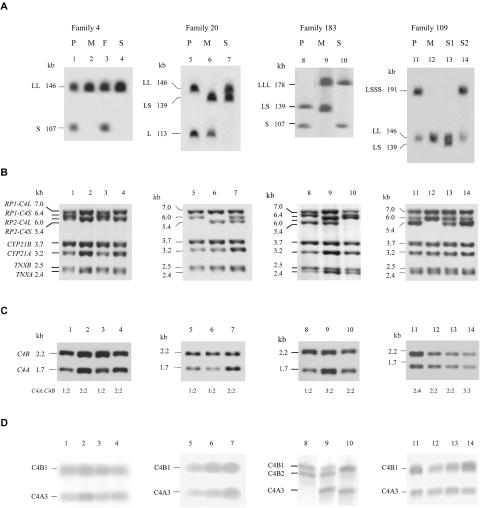

In figure 2 and table 3, we present four examples by which the patient with SLE had a C4A plasma protein level lower than that of C4B, a general phenomenon observed in many European American patients with SLE. The results reveal that, if a subject is heterozygous and one of the RCCX haplotypes is bimodular (containing one C4A gene and one C4B gene), four different scenarios exist for the other haplotype that can lead to a lower effective GCN of C4A than of C4B: (a) monomodular S RCCX with a single, short C4B gene (families 4 and 183), (b) monomodular L RCCX with a single, long C4B gene (family 20), (c) bimodular RCCX haplotype that contains a mutant C4A and a functional C4B (family 183), and (d) multimodular RCCX haplotype with higher GCN for C4B than for C4A (family 109). Detailed results on the CNVs of total C4, C4A, C4B, long C4, short C4, and RCCX modules in all study subjects are summarized in table 4.

Figure 2. .

Different genetic mechanisms leading to lower expression of C4A protein than of C4B protein in four families with SLE. In each family, the RCCX modular structures were determined by PFGE of PmeI-digested genomic DNA, Southern blotting, and hybridization to a C4d-specific probe (A). TaqI genomic RFLP was applied to yield details of genomic structures for the RCCX constituents, including the dichotomies of RP1 and RP2, C4 long and C4 short linked to RP1 or RP2, CYP21B, CYP21A, TNXB, and TNXA (B). PshAI-PvuII RFLP was applied to determine the relative GCNs of C4A and C4B (C). The C4A and C4B protein polymorphisms were elucidated by immunofixation of EDTA plasma resolved by high-voltage agarose-gel electrophoresis (D). P = patient; M = mother; F = father; S = sibling (S1 = sibling 1; S2 = sibling 2).

Table 3. .

Summary of RCCX Modules, Gene CNV, and Protein Polymorphisms of Total C4, C4A, and C4B in Four Selected Families with SLE

| GCN |

Allotypes |

Concentrationa(mg/dl) |

|||||||||

| Family and Subject |

RCCX-1 | RCCX-2 | C4 | C4A | C4B | C4A | C4B | Total C4 | C4A | C4B | C4A Mutationb |

| 4: | |||||||||||

| Patient | LL | S | 3 | 1 | 2 | A3 | B1, B1 | 20.8 | 5.0 | 15.6 | No |

| Mother | LL | LL | 4 | 2 | 2 | A3, A3 | B1, B2 | 51.3 | 25.3 | 28.1 | No |

| Father | LL | S | 3 | 1 | 2 | A3 | B1, B1 | 36.0 | 16.6 | 19.4 | No |

| Sibling | LL | LL | 4 | 2 | 2 | A3, A3 | B1, B1 | 25.4 | 12.6 | 12.8 | No |

| 20: | |||||||||||

| Patient | LL | L | 3 | 1 | 2 | A3 | B1, B1 | 15.0 | 4.9 | 10.0 | No |

| Mother | LS | L | 3 | 1 | 2 | A3 | B1, B1 | 23.6 | 10.7 | 12.8 | No |

| Sibling | LL | LS | 4 | 2 | 2 | A3, A3 | B1, B1 | 38.9 | 18.6 | 20.3 | No |

| 183: | |||||||||||

| Patient | LS | S | 3 | 1 | 2 | AQ0 | B1, B2 | 22.5 | 0 | 22.5 | Yes |

| Mother | LLL | LS | 5 | 3 | 2 | A3, A3, AQ0 | B1, B2 | 34.3 | 17.1 | 17.3 | Yes |

| Sibling | LLL | S | 4 | 2 | 2 | A3, A3 | B1, B1 | 33.5 | 13.7 | 19.8 | No |

| 109: | |||||||||||

| Patient | LSSS | LL | 6 | 2 | 4 | A3, A3 | B1, B1, B1, B1 | 41.4 | 11.8 | 29.6 | No |

| Mother | LL | LL | 4 | 2 | 2 | A3, A3 | B1, B1 | 33.6 | 16.9 | 16.7 | No |

| Sibling 1 | LL | LS | 4 | 2 | 2 | A3, A3 | B1, B2 | 40.8 | 19.0 | 21.7 | No |

| Sibling 2 | LSSS | LL | 6 | 2 | 4 | A3, A3 | B1, B1, B1, B1 | 68.6 | 22.6 | 43.0 | No |

Plasma protein concentrations.

2-bp insertion at codon 1213 in exon 29 of C4A (C4AQ0, mutant C4A without a protein product).

Table 4. .

CNV of C4 and RCCX Modules among European American Female and Male Controls (FC and MC, respectively), Female and Male First-Degree Relatives (FF and MF, respectively), Female Patients with SLE from Ohio Study (FP), and Female Patients with SLE from a Replication Study (SP)

| FC |

MC |

FF |

MF |

FP |

SP |

|||||||

| Genes or Haplotypes and Group |

No. | Frequency | No. | Frequency | No. | Frequency | No. | Frequency | No. | Frequency | No. | Frequency |

| Total C4 genes: | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 6 | .015 | 1 | .008 | 14 | .063 | 10 | .07 | 20 | .093 | 3 | .025 |

| 3 | 105 | .27 | 30 | .234 | 68 | .308 | 48 | .338 | 71 | .329 | 45 | .381 |

| 4 | 231 | .594 | 81 | .633 | 120 | .543 | 71 | .5 | 112 | .519 | 62 | .525 |

| 5 | 41 | .105 | 12 | .094 | 15 | .068 | 13 | .092 | 11 | .051 | 4 | .034 |

| ⩾6 | 6 | .015 | 4 | .031 | 4 | .018 | 0 | 0 | 2 | .009 | 4 | .033 |

| Total | 389 | … | 128 | … | 221 | … | 142 | … | 216 | … | 118 | … |

| C4A genes: | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 5 | .013 | 0 | 0 | 6 | .027 | 6 | .043 | 14 | .065 | 3 | .025 |

| 1 | 70 | .182 | 19 | .148 | 53 | .241 | 37 | .262 | 57 | .264 | 39 | .331 |

| 2 | 218 | .566 | 71 | .555 | 121 | .55 | 77 | .546 | 112 | .519 | 63 | .534 |

| 3 | 81 | .21 | 30 | .234 | 32 | .145 | 20 | .142 | 24 | .111 | 11 | .093 |

| 4 | 9 | .023 | 8 | .063 | 8 | .036 | 1 | .007 | 8 | .037 | 1 | .008 |

| 5 | 2 | .005 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .005 | 1 | .008 |

| Total | 385 | … | 128 | … | 220 | … | 141 | … | 216 | … | 118 | … |

| C4B genes: | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 9 | .023 | 5 | .039 | 5 | .023 | 5 | .035 | 6 | .028 | 3 | .025 |

| 1 | 99 | .257 | 39 | .305 | 52 | .236 | 27 | .191 | 49 | .227 | 16 | .136 |

| 2 | 250 | .649 | 75 | .586 | 158 | .718 | 102 | .723 | 153 | .708 | 90 | .763 |

| 3 | 26 | .068 | 9 | .07 | 4 | .018 | 7 | .05 | 7 | .032 | 6 | .051 |

| ⩾4 | 1 | .003 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .005 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .005 | 3 | .025 |

| Total | 385 | … | 128 | … | 220 | … | 141 | … | 216 | … | 118 | … |

| Long C4 genes: | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 4 | .01 | 0 | 0 | 5 | .023 | 3 | .021 | 10 | .046 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 26 | .067 | 5 | .039 | 18 | .082 | 18 | .127 | 20 | .093 | 9 | .101 |

| 2 | 100 | .257 | 29 | .227 | 60 | .273 | 37 | .261 | 63 | .292 | 30 | .337 |

| 3 | 145 | .373 | 46 | .359 | 78 | .355 | 58 | .408 | 68 | .315 | 30 | .337 |

| 4 | 98 | .252 | 44 | .344 | 53 | .241 | 22 | .155 | 51 | .236 | 17 | .191 |

| 5 | 14 | .036 | 3 | .023 | 5 | .023 | 4 | .028 | 3 | .014 | 2 | .022 |

| 6 | 2 | .005 | 1 | .008 | 1 | .005 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .005 | 1 | .011 |

| Total | 389 | … | 128 | … | 220 | … | 142 | … | 216 | … | 89a | … |

| Short C4 genes: | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 130 | .334 | 51 | .398 | 64 | .291 | 35 | .246 | 70 | .324 | 20 | .225 |

| 1 | 170 | .437 | 59 | .461 | 109 | .495 | 69 | .486 | 96 | .444 | 47 | .528 |

| 2 | 80 | .206 | 11 | .086 | 42 | .191 | 36 | .254 | 43 | .199 | 19 | .213 |

| 3 | 8 | .021 | 7 | .055 | 4 | .018 | 2 | .014 | 6 | .028 | 1 | .011 |

| 4 | 1 | .003 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .005 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .005 | 2 | .022 |

| Total | 389 | … | 128 | … | 220 | … | 142 | … | 216 | … | 89a | … |

| RCCX haplotypes: | ||||||||||||

| L | 33 | .042 | 14 | .055 | 31 | .07 | 21 | .074 | 32 | .074 | 5 | .028 |

| S | 88 | .113 | 20 | .078 | 55 | .125 | 43 | .151 | 73 | .169 | 28 | .157 |

| LL | 387 | .497 | 139 | .543 | 205 | .466 | 117 | .412 | 199 | .461 | 76 | .427 |

| LS | 208 | .267 | 60 | .234 | 123 | .28 | 85 | .299 | 105 | .243 | 54 | .303 |

| SS | 1 | .001 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .002 | 1 | .004 | 4 | .009 | 0 | 0 |

| LSL | 11 | .014 | 3 | .012 | 7 | .016 | 5 | .018 | 6 | .014 | 2 | .011 |

| LSS | 25 | .032 | 8 | .031 | 7 | .016 | 6 | .021 | 5 | .012 | 6 | .034 |

| LLL | 24 | .031 | 11 | .043 | 10 | .023 | 6 | .021 | 7 | .016 | 6 | .034 |

| SSS | 0 | 0 | 1 | .004 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LSSS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .002 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .002 | 0 | 0 |

| LLLL | 1 | .001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .006 |

| Total | 778 | … | 256 | … | 440 | … | 284 | … | 432 | … | 178a | … |

Copy numbers of long C4, short C4, and RCCX haplotypes in SP were calculated from California SLE cohort.

C4 GCN in Female European American Patients with SLE, Female First-Degree Relatives, and Unrelated Healthy Female Controls

Because our patients with SLE are predominantly female (females:males 12.7:1), our primary analyses were focused on female subjects.51–53 We first examined the CNV for total C4 genes. In the unrelated female controls (n=389), the variation of C4 GCN showed a pattern close to normal distribution. The majority (59.4%) had four copies of C4 genes. The frequencies of subjects with two, three, five, and six copies of C4 genes were 1.5%, 27.0%, 10.5%, and 1.5%, respectively (table 4 and fig. 3A).

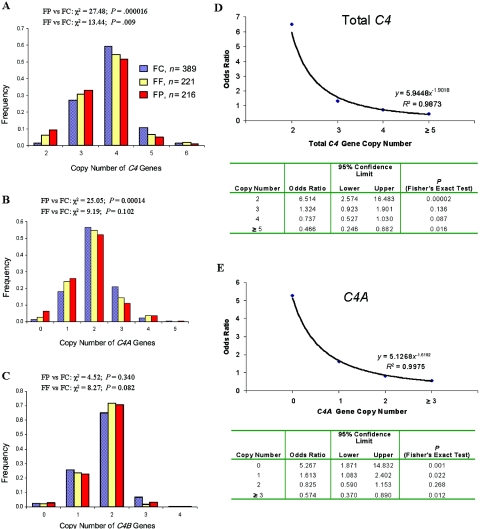

Figure 3. .

C4 gene CNVs in female patients with SLE, first-degree relatives, and unrelated healthy subjects. A–C, Distribution patterns of total C4, C4A and C4B GCN groups among white female patients with SLE (FP [red bars]), their female first-degree relatives (FF [yellow bars]), and unrelated female controls (FC [blue bars]). D and E, GCN-dependent variation in OR and SLE disease susceptibility for total C4 (D) and C4A (E).

In female European American patients with SLE (n=216), a shift of the C4 GCN distribution to the low gene-dosage side was observed (χ2=27.5; df=4; P=.000016). Slightly more than half the patients (51.9%) had four copies of C4 genes. The frequency of subjects with two and three copies of C4 genes increased to 9.3% and 32.9%, respectively. By contrast, the frequencies of subjects with five and six C4 genes decreased to 5.1% and 0.9%, respectively. In comparison with female controls, the OR of patients with SLE who have only two copies of C4 genes is 6.51 (95% CI 2.57–16.5; P=.00002); the OR of patients with SLE with five or six copies of C4 genes is 0.466 (95% CI 0.25–0.88; P=.016) (fig. 3D).

We define gene-copy index as the mean copy number of a gene that manifests interindividual gene CNV in a selected population. The gene-copy index of C4 was highest in the unrelated controls (3.81), lowest in the female patients (3.56; P<.0001 for FP vs. FC), and intermediate in the female first-degree relatives (3.67; P=.036 for FF vs. FC).

Low C4A GCN in Female European Americans with SLE

The reduction of C4 GCN in patients with SLE can be the result of a decrease in C4A, C4B, or both. Therefore, we examined the distribution patterns of C4A and C4B among the female patients, first-degree relatives, and unrelated controls (figs. 3B and 3C).

Total absence of C4A genes (homozygous C4A deficiency) had a frequency of 6.5% in female patients with SLE, compared with 1.3% in unrelated controls (OR=5.27; 95% CI 1.87–14.8; P=.001). Of the patients, 26% had only one copy of the C4A gene (i.e., heterozygous C4A deficiency), compared with 18.2% of unrelated controls (OR=1.61; 95% CI 1.1–2.4; P=.022). Conversely, high C4A GCN (i.e., three, four, or five copies of C4A genes) was observed in 15.3% of the patient group, compared with 23.8% of the control group (OR=0.57; 95% CI 0.37–0.89; P=.012). Overall, the pattern of C4A GCN distribution in female patients with SLE was significantly different from that in unrelated healthy controls (χ2=25.1; df=5; P=.00014). Similar to total C4, the distribution pattern of C4A GCN for the female first-degree relatives was also between the patterns for patients with SLE and unrelated controls (fig. 3B).

The gene-copy index of C4A among female unrelated controls, first-degree relatives, and patients with SLE was 2.05, 1.92 (P=.05 for FF vs. FC), and 1.81 (P=.0005 for FP vs. FC), respectively (table 5).

Table 5. .

Comparison of Gene-Copy Indices for Total C4, C4A, C4B, Long C4, and Short C4 among Patients with SLE, Their First-Degree Relatives, and Unrelated Healthy Controls[Note]

| Gene-Copy Index ± SD |

||||||

| Cohort and Group or Variable |

n | Total C4 | C4A | C4B | Long C4 | Short C4 |

| Ohio SLE Cohort: | ||||||

| FC | 389 | 3.81 ± .75 | 2.05 ± .79 | 1.77 ± .61 | 2.91 ± 1.03 | .93 ± .80 |

| FF | 221 | 3.67 ± .77 | 1.92 ± .80 | 1.74 ± .55 | 2.80 ± 1.07 | .93 ± .75 |

| FP | 216 | 3.56 ± .77 | 1.81 ± .89 | 1.76 ± .58 | 2.66 ± 1.14 | .94 ± .82 |

| MC | 128 | 3.83 ± .83 | 2.21 ± .77 | 1.65 ± .68 | 3.11 ± .94 | .80 ± .82 |

| MF | 141 | 3.62 ± .75 | 1.81 ± .76 | 1.79 ± .58 | 2.63 ± 1.05 | 1.04 ± .75 |

| MP | 17 | 3.53 ± .72 | 1.71 ± .77 | 1.82 ± .53 | 2.53 ± 1.07 | 1.00 ± .87 |

| P value: | ||||||

| FP vs. FC | … | .0001 | .0005 | … | .005 | … |

| FF vs. FC | … | .036 | .05 | … | NS | … |

| MP vs. MC | … | NS | .015 | … | .033 | … |

| MF vs. MC | … | .05 | .0002 | … | .001 | … |

| MC vs. FC | … | NS | .045 | … | NS | … |

| Overall | … | .002 | .0001 | NS | .002 | NS |

| Replication cohort: | ||||||

| SP | 118 | 3.68 ± .77 | 1.75 ± .76 | 1.92 ± .66 | 2.73 ± 1.03 | 1.08 ± .83 |

| P value: | ||||||

| SP vs. FC | … | NS | .0007 | .015 | NS | NS |

| SP vs. FP | … | NS | NS | .019 | .04 | .009 |

| Overalla | … | .0003 | .0001 | .035 | .001 | .04 |

Note.— Gene-copy index is the mean copy number of a specific gene in a selected population. FC = female unrelated controls; FF = first-degree female relatives of patients with SLE; FP = female patients with SLE; MC = male unrelated controls; MF = first-degree male relatives of patients with SLE; MP = male patients with SLE; NS = not significant; SP = female patients with SLE in the replication study.

The overall P value was determined by the ANOVA F test after dependence adjustment. Student’s post hoc t test was used to calculate P values for each individual pair.

Unlike C4A, no significant differences in C4B GCN distribution patterns were observed among female patients, their first-degree relatives, and unrelated controls. Among the patients with SLE, 70.8% had the medium C4B gene dosage, with two copies of C4B genes (fig. 3C). The C4B gene-copy index in all three groups was similar (range 1.74–1.77) (table 3). Therefore, the main cause for the low GCN of total C4 in European American patients with SLE was the low GCN of C4A.

CNV of Long and Short C4 Genes and Their Correlations with C4A and C4B

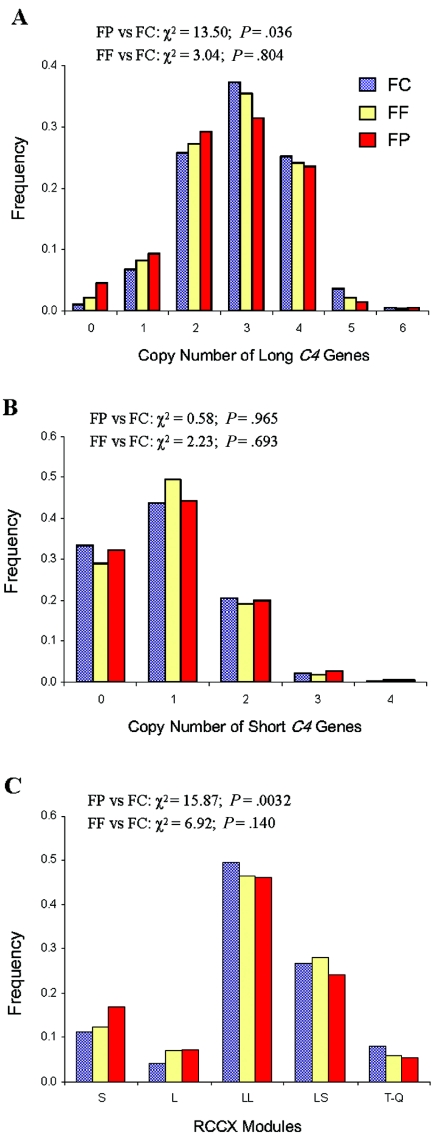

We then examined the variations of long and short C4 genes. In all three groups of female subjects, the copy number of long genes varied from 0 to 6, whereas that of short genes varied from 0 to 4. Three copies of long C4 genes and one copy of a short C4 gene were the most prevalent counts among all study groups (figs. 4A and 4B). The gene-copy index of long C4 was 2.66 in patients with SLE and 2.91 in unrelated controls (P=.006, by Student’s t test) (table 5). No significant difference was observed for the gene-copy index of short C4, which was 0.94 in patients with SLE and 0.93 in unrelated female controls.

Figure 4. .

Distribution patterns of long and short C4 genes and RCCX haplotype structures among female patients with SLE (FP [red bars]), their female first-degree relatives (FF [yellow bars]), and unrelated female controls (FC [blue bars]). A, Gene CNV of long C4. B, Gene CNV of short C4. C, Haplotype variation of RCCX structures. T-Q = trimodular and quadrimodular.

The next question we asked was about the degree of correlation between long or short C4 genes and C4A or C4B (table 6). Among three female population groups, the Pearson’s coefficients of correlation (R) between long C4 genes and C4A were 0.77, 0.69, and 0.64 for patients with SLE, female first-degree relatives, and unrelated female controls, respectively. The overall correlation coefficient between long genes and C4A was 0.70 (P<.0001). The Pearson’s coefficient of correlation between short C4 genes and C4B was 0.48, 0.38, and 0.44 for the patients with SLE, female first-degree relatives, and female unrelated controls, respectively. The overall coefficient of correlation between short genes and C4B was 0.44 (P<.0001).

Table 6. .

Pearson Coefficient of Correlation (R) of Long and Short C4 Genes with C4A and C4B in Female Patients with SLE, Female First-Degree Relatives, and Unrelated Female Controls

| Female Patients with SLE(n=216) |

Female First-Degree Relatives(n=220) |

Unrelated Female Controls(n=387) |

All Three Groups(n=823) |

|||||

| Correlation | R | P | R | P | R | P | R | P |

| Long C4 with: | ||||||||

| C4A | .765 | <.0001 | .688 | .688 | .642 | <.0001 | .695 | <.0001 |

| C4B | −.230 | .0007 | −.028 | −.028 | −.135 | .0079 | −.133 | .0001 |

| Short C4 with: | ||||||||

| C4A | −.435 | <.0001 | −.285 | −.285 | −.301 | <.0001 | −.335 | <.0001 |

| C4B | .482 | <.0001 | .380 | .380 | .442 | <.0001 | .437 | <.0001 |

Inverse correlations between long genes and C4B and between short genes and C4A were observed in most groups. Such inverse correlations implied that the greater the copy number of long C4 genes in an individual, the less likely there will be an increase in copy number of C4B, and the greater the number of short C4 genes, the less likely there will be an increase in the copy number of C4A.

Increase in Monomodular RCCX and Decrease in Bimodular and Trimodular RCCX in SLE

The PmeI-PFGE and the TaqI genomic RFLP data allowed us to examine the constituents of the RCCX haplotypes and the configurations of long and short C4 genes in the RCCX. Seven common (L, S, LL, LS, LSL, LSS, and LLL; frequency for each haplotype >1%) and four rare (SS, SSS, LSSS, and LLLL; frequency for each haplotype <1%) RCCX length variants were detected (fig. 1B and table 4).

The frequencies of monomodular haplotypes with a single short C4 gene or a single long C4 gene was 15.5% in unrelated female controls and 24.3% in female patients with SLE (χ2=14.0; P=.0002). By contrast, the frequency with trimodular/quadrimodular RCCX haplotypes was 7.8% in the unrelated control group compared with 4.4% in the patient group (χ2=5.33; P=.02). Overall, the distributions of RCCX haplotypes between patients with SLE and unrelated controls were significantly different (χ2=15.9; P=.0032), but those between female first-degree relatives and unrelated controls were not (χ2=6.92; P=.14) (fig. 4C).

Bimodular LL and bimodular LS were the most common RCCX haplotypes among all European American subjects. A modest difference in the frequency of bimodular structures between patients with SLE (70.4%) and controls (76.5%) was observed (χ2=5.43; P=.02).

Association of TNFA −308G→A Polymorphism with SLE, Secondary to the Monomodular S RCCX Haplotypes with Absence of C4A

The −308A allele (also known as “TNF2”) of the human tumor necrosis factor-α gene (TNFA) has been suggested to be associated with autoimmune diseases, including SLE.54–56 Because TNFA is located 403.5 kb telomeric to complement C4 in the MHC class III region, we compared the frequencies of TNF2 among female European American patients with SLE, their female first-degree relatives, and healthy female controls. Overall, the allelic frequency of TNF2 was 0.17 in unrelated healthy controls and 0.231 in the patients with SLE (χ2=4.5; P=.039; OR=1.48).

The roles of TNF2 and low C4A GCN as risk factors of SLE are compared by two methods. First, we categorized the study subjects according their C4A GCN—low (GCN of zero or one), medium (GCN of two), or high (GCN of three, four, five, or six)—and then compared the frequency of TNF1 and TNF2 in each group. Second, we segregated the study subjects into TNF1 (−308GG) and TNF2 (−308GA or −308AA) carriers and then compared the frequencies of low, medium, and high C4A GCN in each group (table 7). When the C4A GCN groups were controlled for, there was no consistent increase in the frequency of TNF2 in the patients with SLE. No significant difference was observed for the distribution of the TNF1- and TNF2-carrier frequencies between the healthy controls and the patients with SLE among the subjects with low, medium, or high C4A GCN. When TNF1 and TNF2 carriage was controlled for, there was a consistent increase in the frequencies of low C4A GCN and a consistent decrease in the frequencies of high C4A GCN in the patients with SLE, compared with controls. In particular, a great difference in frequencies of low C4A GCN was observed between the control group (39.6%) and the patients with SLE (70.1%) among the subjects who are TNF2 carriers (χ2=16.0; P=.0003), suggesting that low C4A GCN is a strong risk factor for SLE among the subjects who are TNF2 carriers. Of equal importance is the substantial reduction in the frequency of subjects with high C4A GCN (8.05%) in patients with SLE, compared with healthy controls (30.2%). These analyses suggest that C4A gene CNV is likely a more important risk factor for human SLE than is the TNFA −308G→A polymorphism.

Table 7. .

CNV of C4A and the TNFA −308 G→A Polymorphism in European American Female Patients with SLE and Controls

| No. (%) of |

|||||

| Factor | Female Controls | Female Patients | χ2 | P | OR (95% CI) |

| TNF2 and TNF1 | |||||

| TNF2 allele | 58 (17.0) | 100 (23.1) | 4.501 | .039 | 1.48 (1.03–2.11) |

| TNF1 allele | 284 (83.0) | 332 (76.9) | |||

| Total | 342 (100) | 432 (100) | |||

| TNF2 carriers | 53 (31.2) | 87 (40.3) | 3.41 | .07 | 1.49 (.98–2.27) |

| TNF1 only | 117 (68.8) | 129 (59.7) | |||

| Total | 170 (100) | 216 (100) | |||

| C4A GCN: | … | … | 14.5 | .0002 | 2.59 (1.57–4.28) |

| Low C4A (<2) | 27 (15.9) | 71 (32.9) | |||

| Medium/high C4A (⩾2) | 143 (84.1) | 145 (67.1) | |||

| Total | 170 (100) | 216 (100) | |||

| Controlling for C4A GCN: | |||||

| Low C4A (<2): | … | … | .95 | .366 | |

| TNF1 | 6 (22.2) | 10 (14.1) | |||

| TNF2 carrier | 21 (77.8) | 61 (85.9) | |||

| Total | 27 (100) | 71 (100) | |||

| Medium C4A (2): | … | … | 0 | 1.000 | |

| TNF1 | 78 (83.0) | 93 (83.0) | |||

| TNF2 carrier | 16 (17.0) | 19 (17.0) | |||

| Total | 94 (100) | 112 (100) | |||

| High C4A (>2): | … | … | 1.28 | .321 | |

| TNF1 | 33 (67.4) | 26 (78.8) | |||

| TNF2 carrier | 16 (32.7) | 7 (21.2) | |||

| Total | 49 (100) | 33 (100) | |||

| Controlling for TNFA polymorphism: | |||||

| TNF2 carrier: | … | … | 16.0 | .0003 | |

| Low C4A | 21 (39.6) | 61 (70.1) | |||

| Medium C4A | 16 (30.2) | 19 (21.8) | |||

| High C4A | 16 (30.2) | 7 (8.05) | |||

| Total | 53 (100) | 87 (100) | |||

| TNF1 only | … | … | 2.57 | .277 | |

| Low C4A | 6 (5.13) | 10 (7.75) | |||

| Medium C4A | 78 (66.7) | 93 (72.1) | |||

| High C4A | 33 (28.2) | 26 (20.2) | |||

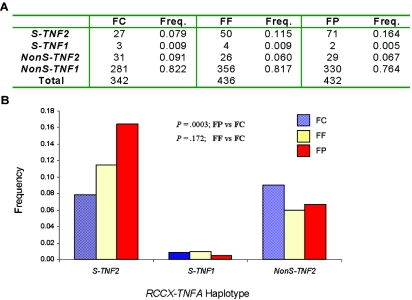

Among the TNF2 alleles in the unrelated control group, slightly less than half were linked to the monomodular S haplotype of RCCX with the presence of a single short C4B gene (i.e., with the absence of a C4A gene). This haplotype is abbreviated as S-TNF2. A segregation analysis of TNF2 haplotypes in the S-TNF2 group and the nonS-TNF2 group revealed two relevant features (fig. 5). First, the frequency of the S-TNF2 group in the patients with SLE was 2.1 times greater than that in the healthy controls (patients with SLE 0.164; controls 0.079). Second, the frequency of the nonS-TNF2 group in the patients with SLE was less than that in the healthy controls (patients 0.067; controls 0.091) (χ2=13.7; P=.003). This observation further underscores the importance of complement C4A deficiency as a primary genetic risk factor in the MHC class III region associated with SLE.

Figure 5. .

Significant increase in the frequency of monomodular S RCCX haplotype with C4A deficiency linked to the −308A allele of the TNFA gene (S-TNF2) in SLE. A, Number and frequency (Freq.) of each haplotype in unrelated female controls (FC), female first-degree relatives (FF), and female patients with SLE (FP). B, Differences between the three groups. NonS-TNF2 = TNF2 allele not linked to monomodular S haplotype of RCCX; NonS-TNF1 = −308G allele of the TNFA gene not linked to monomodular S haplotype of RCCX.

Family-Based Association Test (FBAT) Reveals Monomodular S RCCX C4B with C4A Deficiency and TNFA Promoter Polymorphism as Risk Factors and C4A6 as a Protective Factor for SLE

FBAT was applied, to analyze whether haplotypes with specific RCCX length variants, C4A and C4B protein allotypes, and TNFA promoter polymorphisms are genetic risk factors for SLE. It is anticipated that a SLE risk factor would be transmitted more frequently from parents to offspring who develop SLE. The analytical technique FBAT works robustly against the bias caused by genetic admixture and stratification.50

As shown in table 8, the monomodular RCCX structures with either a long or short C4 gene had a higher-than-expected frequency of transmission to the patient population, with a P value of .014. Further analysis demonstrates a highly significant increase in the transmission of the monomodular S haplotype to the patient (P=.005).

Table 8. .

FBAT for RCCX, C4, and TNFA Haplotypes in the Ohio SLE Cohort[Note]

| Haplotype | Frequency | No. of Families | Observed Score | Expected Score | P |

| RCCX: | |||||

| S and L | .209 | 105 | 82 | 68.4 | .014 |

| S | .127 | 81 | 61 | 47.7 | .005 |

| C4: | |||||

| B1 | .129 | 82 | 61 | 48.1 | .005 |

| A6B1 | .041 | 31 | 11 | 17.1 | .03 |

| AQ0X | .164 | 98 | 75 | 62.0 | .013 |

| TNFA: | |||||

| TNF2 | .191 | 88 | 109 | 118 | .078 |

| RCCX(C4)-TNFA: | |||||

| S(C4B1)-TNF2 | .112 | 58 | 54 | 42.5 | .004 |

| LS(C4A6B1)-TNF1 | .032 | 25 | 8.5 | 14.8 | .011 |

Note.— All markers as a group—including RCCX, C4, TNFA, and RCCX(C4)-TNFA but not TNFA—were statistically significant. The individual haplotypes in each marker group were then tested and are summarized above. AQ0X represents bimodular RCCX structure with a mutant C4A gene with a 2-bp insertion in exon 29 (C4AQ0) and a functional C4B gene that can code for a C4B1 or C4B2 protein.

There were 46 different combinations of C4A and C4B protein allotypes in the Ohio SLE families. Among them, 12 haplotypes each had a frequency >1%. C4 protein haplotypes without a C4A protein (i.e., C4B1, C4AQ0-B1, and C4AQ0-B2) were more frequently transmitted to patients (P=.013), supporting a probable role of C4A deficiency as a risk factor for SLE development. In addition, the haplotype with C4A6-B1 was less frequently transmitted to patients (P=.03), suggesting a possible protective role of C4A6 against SLE disease susceptibility.

We further analyzed the transmission of specific RCCX haplotypes, C4 protein phenotypes, and the TNFA promoter polymorphism −308G→A to patients with SLE. The most common RCCX haplotype with a C4A deficiency, monomodular S coding for C4B1 in linkage to the TNF2 allele (i.e., S(C4B1)-TNF2), was significantly increased in transmission to the patients with SLE (P=.004). By contrast, C4A6-B1 linked to bimodular LS of RCCX and TNF1 allele (i.e., LS(C4A6-B1)-TNF1) was significantly decreased from the expected transmission frequency in the patient population (P=.011). These results are consistent with results observed in case-control studies suggesting that C4A deficiency is a risk factor for SLE. On the other hand, RCCX haplotypes coding for C4A6 appear to be protective.

Gene CNV of Complement C4 in an Independent European American Patient Population with SLE

To validate the association of low GCN of total C4 and/or C4A deficiency with SLE in European Americans, we examined gene CNV of C4 in an independent group of patients with SLE. These patients were recruited from two sources. The first source was from Southern California, consisting of 99 European American patients (89 females and 10 males). C4 genotyping experiments were performed by genomic Southern-blot analyses that allowed elucidation of copy numbers for total C4, C4A, C4B, long C4 genes, short C4 genes, and the RCCX modules. The second source was APSCORE, providing 29 female patients with SLE who were not symptomatic for thrombosis or recurrent spontaneous abortions. A novel series of real-time PCR strategies were applied to determine the GCNs of total C4, C4A, and C4B (Y.L.W., S.L.S., Y.Y., B.Z., B.H.R., D.J.B., H.N.N., L.A.H., and C.Y.Y., unpublished data). The C4 gene CNV results for these patients with SLE were compared with those of unrelated, healthy female controls from Ohio (n=389).

Because of the smaller patient sample size for the replication study, we categorized the C4 GCN groups into low, medium, and high. The results showed that 40.6% of the female replication patients with SLE had low copy number of total C4 (i.e., two or three copies), which was similar to the 42.2% of patients in the Ohio SLE study (tables 4 and 9). The OR for low C4 gene dosage in female replication patients was 1.67 (95% CI 1.09–2.55; P=.024). The OR for high total C4 gene dosage (i.e., five, six, or seven copies of total C4) in female replication patients was 0.52, although the difference from controls was not statistically significant.

Table 9. .

Replication Study to Validate Low GCN of Total C4 or C4A as Risk Factor for and High GCN as Protective Factor against SLE in European Americans

| Gene, Patients, and GCN |

OR (95% CI) | Pa |

| Total C4: | ||

| Ohiob: | ||

| 2 or 3 | 1.823 (1.287–2.583) | .001 |

| 4 | .737 (.527–1.030) | .087 |

| 5 or 6 | .466 (.246–.882) | .016 |

| SPc: | ||

| 2 or 3 | 1.666 (1.087–2.554) | .024 |

| 4 | .783 (.518–1.184) | .289 |

| 5 or 6 | .520 (.239–1.132) | .129 |

| C4A: | ||

| Ohiob: | ||

| 0 or 1 | 2.024 (1.384–2.959) | .0003 |

| 2 | .825 (.590–1.153) | .268 |

| 3, 4, or 5 | .574 (.370–.890) | .012 |

| SPc: | ||

| 0 or 1 | 2.121 (1.352–3.326) | .001 |

| 2 | .926 (.612–1.400) | .752 |

| 3, 4, or 5 | .391 (.210–.729) | .002 |

P value calculated by Fisher’s exact test.

Prospective European American patients with SLE who are from Ohio.

Independent European American patients with SLE who were part of a replication study.

The frequency of subjects with homozygous or heterozygous C4A gene deficiency (i.e., zero or one copy of the C4A gene) was 35.6% in the female replication patients with SLE, which was similar to the 32.5% in Ohio patients with SLE. The OR for low C4A GCN was 2.12 (95% CI 1.35–3.33; P=.001), and the OR for high C4A GCN was 0.39 (95% CI 0.21–0.73; P=.002) in female replication patients. The OR in the Ohio SLE cohort for low C4A GCN was 2.02 (95% CI 1.38–2.96; P=.0003) and, for high C4A GCN, was 0.57 (95% CI 0.37–0.89; P=.012) (table 9).

The gene-copy indices for total C4 and C4A were 3.68 and 1.75, respectively, in the female replication patients with SLE. In the Ohio SLE cohort, the corresponding gene-copy indices were 3.56 and 1.81 (in healthy controls, gene-copy indices were 3.81 for total C4 and 2.05 for C4A) (table 5). These results are consistent with the notion that low total C4 or low C4A GCNs are more prevalent, whereas high C4A GCN is less frequent in both groups of patients with SLE.

Discussion

Two recent genome-scan meta-analyses identified similar genomic regions—namely, 6p21.1-6p22.3 and 6p21.1-6q15—that have the most consistent evidence of linkage with human SLE.6,57 The human MHC (also known as “HLA”) is implicated as an SLE susceptibility locus in both studies. Indeed, multiple linkage or association studies have suggested that HLA haplotypes with DR3, DR2 (i.e., DRB1*1501) (HLA-DRB1 [MIM 142857]), or B8 (HLA-B [MIM 142830]); deficiencies of MHC class III gene complement C4A or complement C2; and the promoter polymorphism of TNFA (−308G→A) are risk factors for SLE.19,53,58–60 A limitation for most epidemiologic studies on MHC and associated diseases is that, although polymorphic variants, SNPs, or microsatellites of MHC identified yield consistent results to establish linkage or identify haplotypes with higher risk of disease susceptibility, they do not necessarily provide insights on the causative allele(s). The strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) of MHC class I, II, and III alleles in many MHC ancestral haplotypes59,61 imposes great difficulty for identifying which candidate gene or genes are the most relevant in MHC-associated diseases, including SLE. In addition, there had been a lack of accurate data on the gene CNVs of complement C4A and C4B in healthy controls and patients with SLE. There is also no knowledge of microsatellites or tagging SNPs that can serve as surrogates of C4 gene CNVs. The recent advance of the International HapMap Project has yielded large quantities of information on the SNPs and LD blocks in human genomes from three racial groups, including those in the MHC.62,63 This information will provide a foundation for future deliberate analyses of causal variants in MHC-associated disease.64 Through a preliminary analysis of LD blocks of SNPs in the MHC in European Americans from the centromeric class II DR region through the central class III region to the telomeric class I region, it appears that the RCCX modules with complement C4A and C4B are present in different major LD blocks from the class II DR region and the TNFA region close to the class I genes (UCSC Genome Browser).

To date, complete DNA sequences for three HLA consanguineous cell lines corresponding to haplotypes A1-B8-Cw7-DR3-DQ2 (cell line COX),65 A3-B7-Cw7-DR15-DQ6 (cell line PGF),65 and A26-B18-Cw5-DR3-DQ2 (cell line QBL)66 have been published (MHC Haplotype Project). Two regions in the human MHC are confirmed to have gene CNVs. The first CNV region is in the class II region between DRB1 (a functional gene) and DRB9 (a nonfunctional gene segment) that houses zero or one additional DRB functional gene (DRB3, DRB4, or DRB5), and zero, one, or two copies of DRB pseudogenes (DRB2, DRB6, DRB7, or DRB8). The second CNV region is the RCCX modular variation at the class III region, as described in the present article. Similar to our observations of family C008 published elsewhere,36 the A1-B8-Cw7-DR3-DQ2 haplotype has DRB2 (pseudogene) and DRB3 (functional gene) between DRB1 and DRB9 in the class II region and monomodular S RCCX with a single short C4B gene in the class III region; the A3-B7-Cw7-DR15-DQ6 haplotype has DRB5 and DRB6 (pseudogene) between DRB1 and DRB9 in the class II region and a bimodular long-long (LL) RCCX haplotype coding for C4B1-A3 in the class III region.36 Intriguingly, the order of C4A and C4B genes with respect to C2/factor B and DR are reversed (i.e., C4B-C4A instead of C4A-C4B) in this B7-DR15 haplotype.65 For the A26-B18-Cw5-DR3-DQ2 haplotype, DRB2 and DRB3 are present in the class II region, and the monomodular L with a single C4A gene is present in the class III region. The presence of three different RCCX/C4 GCN and length variants in three HLA haplotypes underscores the structural complexity of complement C4A and C4B.

In the present study, we establish strong correlations of gene CNV of complement C4 (total C4) and its associated polymorphisms (C4A and long C4 genes) with human SLE. Typical of many susceptibility genes associated with an autoimmune disease, the risk factor (i.e., low copy number of total C4 or C4A) is present in the general population, but the prevalence is significantly increased in the patient population (with SLE). Importantly, a dose-dependent phenomenon from increased SLE disease risk at low GCN to protection against disease susceptibility at high GCN is observed for both total C4 and C4A. The RCCX modular variation reflects differences in the copy number and configurations of long and short C4A or C4B genes in a haplotype. This study shows that monomodular RCCX structure with a short C4B gene and the absence of C4A is a relatively common haplotype among European American patients with SLE. By contrast, trimodular RCCX haplotypes with three functional C4 genes are less frequent among patients with SLE.

We employ the concept of gene-copy index (i.e., the mean copy number of a specific gene in a selected population) to facilitate a quantitative comparison of gene CNV among groups. The results provide a quantitative basis for gene CNV of total C4 or C4A as a risk factor for or a protective factor against SLE disease susceptibility. The gene-copy indices of total C4 and C4A in the female first-degree relatives are lower than those in unrelated healthy controls but are higher than those in patients with SLE. This suggests that first-degree relatives of patients with SLE are harboring some genetic risk factor for autoimmune disease, but most of them are healthy probably because of the weak penetrance of genetic risk factors involved in complex diseases and/or because their milieus of genetic and environmental risk factors have not reached the threshold to initiate the disease process. Nevertheless, the lower total C4 and C4A GCNs in first-degree relatives than in unrelated healthy controls would offer a logical explanation for the higher incidence and clustering of autoimmune diseases in family members of patients with SLE.1,4 A replication study involving an independent patient cohort reaffirmed the role of low total C4 and C4A GCNs in increased risk of SLE susceptibility.

Besides the SLE disease activities, our data also revealed that gene CNV of C4 is the predominant genetic factor that mediates the plasma or serum C4 protein concentrations23,43 (Y.Y., Y.L.W., H.N.N., B.H.R., D.J.B., L.A.H., and C.Y.Y., unpublished data). Therefore, a comprehensive elucidation of the C4 gene CNV and quantitative variations of plasma or serum C4 protein levels plus their activation and/or inactivation split products (C4a and/or C4d) would yield highly relevant information to help diagnose and manage SLE.21,23,67,68

Historically, interindividual gene CNV has not been considered to be a source of inherent genetic diversity. However, recent advances in global genomewide analysis have revealed multiple and variable segmental duplications of genomic regions among different individuals.69–71 A public database on human genome diversity lists 3,463 possible loci, including complement C4, that can have CNV (Human Genome build 35, Database of Genomic Variants). The data source was mainly derived from varying fluorescence intensities on microarray chips after comparative hybridization with labeled genomic DNA from different human subjects. More-refined studies will be necessary to elucidate the distribution patterns of interindividual and interpopulation gene CNVs, their related polymorphisms, and possible physiologic roles in health and disease.72–74 This is because, although duplicated genomic segments involved in CNVs are highly homologous, they may not be totally identical in DNA sequences. Case-by-case examination often reveals secondary genetic events that yield new markers or polymorphisms and sometimes add novel functions to existing gene products. Although sequence exchanges among variants of duplicated sequences promote diversity, they can also carry a genetic burden by harboring deleterious mutations. Of the RCCX modules, multiple mutations accumulated in the CYP21A can be transferred to CYP21B, which can become allelic when a monomodular RCCX pairs with a bimodular RCCX and thus abolishes or diminishes the enzymatic activity of the steroid 21-hydroxylase. Mutations or the absence of CYP21B are the main cause of congenital adrenal hyperplasia.34,35,75 Moreover, the acquisition of the 120-bp deletion from the TNXA gene fragment by the intact tenascin-X gene TNXB is responsible for a form of Ehlers-Danlo syndrome (MIM 130020).76

For complement C4, secondary genetic diversifications led to the emergence of two forms of C4 genes (long and short) and two isotypes of C4 proteins (C4A and C4B). C4A is probably a newly evolved protein that acquires a novel function by binding effectively to amino groups of protein substrates or immune complexes, thereby enhancing immune-complex clearance that would otherwise promote autoimmunity. Gene CNV permits the coexistence and quantitative variation of C4A and C4B proteins and the emergence of new protein variants or allotypes in each group. C4A6 is a variant allotype that dissociates the lytic pathway from the classical or lectin activation pathway of the complement system, as the R458W polymorphism in C4A6 disables the binding of C5 and abrogates the C5 convertase activity of C4b2a3b.77,78 This study suggests that C4A6 could be a protective factor against SLE. One possibility is that this allotype could attenuate the deleterious effects of complement lytic pathway–mediated tissue injury during an autoimmune process.

In addition to C4A deficiency, we have also examined two other genetic risk factors in MHC class III region—namely, the deficiency of complement C279,80 and the −308A allele of TNFA (i.e., the TNF2 allele)—as susceptibility factors for SLE.81–83 Complement C2 deficiency appeared infrequently in our patients with SLE, since only one homozygous and four heterozygous C2 deficiencies were present among 233 Ohio patients with SLE. On the other hand, a significant increase in the frequency of TNF2 in SLE was observed (patients 0.231; controls 0.170; OR=1.48; P=.039). In healthy subjects, close to half of the TNF2 alleles are linked to monomodular S of RCCX, S-TNF2. In SLE, the increase of TNF2 frequency appeared to be secondary to the increase of monomodular S with C4A deficiency, which had a haplotype frequency of 0.164 in patients with SLE and 0.079 in unrelated healthy controls. By contrast, the frequency of TNF2 alleles not associated with monomodular S (i.e., nonS-TNF2) was reduced in patients with SLE (patients 0.067; controls 0.091). The relevance of the S-TNF2 haplotype in SLE was further substantiated by FBAT analysis.

The strength of this work lies on the high resolution and the comprehensiveness by which the diversities of C4A and C4B genotypes and phenotypes in healthy subjects and in patients with SLE are elucidated. Recently, association between gene CNV and human disease has been documented in three other incidences: an increased risk of HIV infection and progression to severe disease for individuals with low GCN of CCL3L1,84 low copy number of beta-defensin 2 in inflammatory bowel disease,85 and possibly low GCN of immunoglobulin receptor FCGR3B in glomerulonephritis.86 Further detailed analysis of gene CNV and associated genetic diversities in human populations promises to increase our understanding of complex diseases and quantitative genetic traits.87,88

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the blood donors, patients with SLE, and family members for their contributions to this work. We gratefully acknowledge many rheumatologists and nephrologists who referred their patients to us; Dr. Carlos Alvarez for helpful discussion; Dr. Natalie Jacobsen-Longman, Denise Yu, and Jennifer Kohout for their assistance; and Dr. Shili Lin for help in the early design of the prospective genetic study.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants 5P01 DK55546, 1R01 AR050078, R01 AR43814, K23 HL70823, K12 HD43372, and M01 RR00034; the Lupus Clinical Trials Consortium; the Pittsburgh Supercomputer Center, through NIH Center for Research Resources Cooperative Agreement grant 1P41 RR06009; the Antiphospholipid Syndrome Collaborative Registry (NIH contract N01-AR-2248); and the General Clinical Research Centers Program (NIH grant RR00046).

Web Resources

Accession numbers and URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

- Database of Genomic Variants, http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/ (for human genomic loci with possible gene CNV [build 36])

- GenBank, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/ (for human C4A coding sequence [accession number NM_007293], human C4B coding sequence [accession number NM_001002029], human endogenous retrovirus in long C4 gene, HERV-K(C4) [accession number U07856], monomodular S RCCX coding for C4B [accession number AL662849], monomodular L RCCX coding for C4B [accession number NG_005163], and bimodular LL RCCX coding for C4B-C4A [accession number AL64592])

- International HapMap Project, http://www.hapmap.org/cgi-perl/gbrowse/hapmap_B35/

- MHC Haplotype Project, http://www.sanger.ac.uk/HGP/Chr6/MHC/

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/ (for SLE, C4A, C4B, C1q, C1r, C1s, STK19, CYP21A1, TNXB, HLA-DRB1, HLA-B, and Ehlers-Danlo syndrome)

- UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTracks (for the RCCX region in the human MHC, chromosome 6, position 32040000–32220000)

References

- 1.Davidson A, Diamond B (2001) Autoimmune diseases. N Engl J Med 345:340–350 10.1056/NEJM200108023450506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsokos GC, Gordon C, Smolen JS (2007) Systemic lupus erythematosus: a companion to rheumatology. 1st ed. Mosby-Elsevier, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petri M (2006) Systemic lupus erythematosus and related diseases: clinical features. In: Rose NR, Mackay IR (eds) The autoimmune diseases. 4th ed. Elsevier Academic Press, St Louis, pp 351–356 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsao BP (2003) The genetics of human systemic lupus erythematosus. Trends Immunol 24:595–602 10.1016/j.it.2003.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croker JA, Kimberly RP (2005) Genetics of susceptibility and severity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol 17:529–537 10.1097/01.bor.0000169360.15701.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forabosco P, Gorman JD, Cleveland C, Kelly JA, Fisher SA, Ortmann WA, Johansson C, Johanneson B, Moser KL, Gaffney PM, et al (2006) Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage studies of systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun 7:609–614 10.1038/sj.gene.6364338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll MC (1998) The role of complement and complement receptors in induction and regulation of immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 16:545–568 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walport MJ (2001) Complement: first of two parts. N Engl J Med 344:1058–1066 10.1056/NEJM200104053441406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walport MJ (2001) Complement: second of two parts. N Engl J Med 344:1140–1144 10.1056/NEJM200104123441506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu CY, Chung EK, Yang Y, Blanchong CA, Jacobsen N, Saxena K, Yang Z, Miller W, Varga L, Fust G (2003) Dancing with complement C4 and the RP-C4-CYP21-TNX (RCCX) modules of the major histocompatibility complex. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 75:217–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manderson AP, Botto M, Walport MJ (2004) The role of complement in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. Annu Rev Immunol 22:431–456 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauptmann G, Grosshans E, Heid E (1974) Lupus erythematosus syndrome and complete deficiency of the fourth component of complement. Boll Ist Sieroter Milan Suppl 53:228 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis MJ, Botto M (2006) Complement deficiencies in humans and animals: links to autoimmunity. Autoimmunity 39:367–378 10.1080/08916930600739233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu CY, Hauptmann G, Yang Y, Wu YL, Birmingham DJ, Rovin BH, Hebert LA (2007) Complement deficiencies in human systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and SLE nephritis: epidemiology and pathogenesis. In: Tsokos GC (ed) Systemic lupus erythematosus: a companion to rheumatology. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 203–213 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prodeus AP, Goerg S, Shen LM, Pozdnyakova OO, Chu L, Alicot EM, Goodnow CC, Carroll MC (1998) A critical role for complement in maintenance of self-tolerance. Immunity 9:721–731 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80669-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z, Koralov SB, Kelsoe G (2000) Complement C4 inhibits systemic autoimmunity through a mechanism independent of complement receptors CR1 and CR2. J Exp Med 192:1339–1351 10.1084/jem.192.9.1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Botto M, Dell’Agnola C, Bygrave AE, Thompson EM, Cook HT, Petry F, Loos M, Pandolfi PP, Walport MJ (1998) Homozygous C1q deficiency causes glomerulonephritis associated with multiple apoptotic bodies. Nat Genet 19:56–59 10.1038/ng0598-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook HT, Botto M (2006) Mechanisms of disease: the complement system and the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2:330–337 10.1038/ncprheum0191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson JP, Schneider PM (2004) Genetic susceptibility and class III complement genes. In: Lahita RG (ed) Systemic lupus erythematosus. 4th ed. Elsevier-Academic Press, San Diego, pp 153–201 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y, Chung EK, Zhou B, Lhotta K, Hebert LA, Birmingham DJ, Rovin BH, Yu CY (2004) The intricate role of complement C4 in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Dir Autoimmun 7:98–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schur PH, Sandson J (1968) Immunologic factors and clinical activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 278:533–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fielder AHL, Walport MJ, Batchelor JR, Rynes RI, Black CM, Dodi IA, Hughes GRV (1983) Family study of the major histocompatibility complex in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: importance of null alleles of C4A and C4B in determining disease susceptibility. Br Med J 286:425–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu YL, Higgins GC, Rennebohm RM, Chung EK, Yang Y, Zhou B, Nagaraja N, Birmingham DJ, Rovin BH, Hebert LA, et al (2006) Three distinct profiles of serum complement C4 proteins in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients: tight associations of complement C4 and C3 protein levels in SLE but not in healthy subjects. Adv Exp Med Biol 586:227–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mauff G, Luther B, Schneider PM, Rittner C, Strandmann-Bellinghausen B, Dawkins R, Moulds JM (1998) Reference typing report for complement component C4. Exp Clin Immunogenet 15:249–260 10.1159/000019079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanchong CA, Chung EK, Rupert KL, Yang Y, Yang Z, Zhou B, Yu CY (2001) Genetic, structural and functional diversities of human complement components C4A and C4B and their mouse homologs, Slp and C4. Int Immunopharmacol 1:365–392 10.1016/S1567-5769(01)00019-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belt KT, Yu CY, Carroll MC, Porter RR (1985) Polymorphism of human complement component C4. Immunogenetics 21:173–180 10.1007/BF00364869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu CY, Belt KT, Giles CM, Campbell RD, Porter RR (1986) Structural basis of the polymorphism of human complement component C4A and C4B: gene size, reactivity and antigenicity. EMBO J 5:2873–2881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu CY, Campbell RD, Porter RR (1988) A structural model for the location of the Rodgers and the Chido antigenic determinants and their correlation with the human complement C4A/C4B isotypes. Immunogenetics 27:399–405 10.1007/BF00364425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isenman DE, Young JR (1984) The molecular basis for the differences in immune hemolysis activity of the Chido and Rodgers isotypes of human complement component C4. J Immunol 132:3019–3027 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Law SKA, Dodds AW, Porter RR (1984) A comparison of the properties of two classes, C4A and C4B, of the human complement component C4. EMBO J 3:1819–1823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dodds AW, Ren X-D, Willis AC, Law SKA (1996) The reaction mechanism of the internal thioester in the human complement component C4. Nature 379:177–179 10.1038/379177a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carroll MC, Fathallah DM, Bergamaschini L, Alicot EM, Isenman DE (1990) Substitution of a single amino acid (aspartic acid for histidine) converts the functional activity of human complement C4B to C4A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:6868–6872 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen L, Wu L-C, Sanlioglu S, Chen R, Mendoza AR, Dangel AW, Carroll MC, Zipf WB, Yu CY (1994) Structure and genetics of the partially duplicated gene RP located immediately upstream of the complement C4A and the C4B genes in the HLA class III region: molecular cloning, exon intron structure, composite retroposon, and breakpoint of gene duplication. J Biol Chem 269:8466–8476 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Z, Mendoza AR, Welch TR, Zipf WB, Yu CY (1999) Modular variations of HLA class III genes for serine/threonine kinase RP, complement C4, steroid 21-hydroxylase CYP21 and tenascin TNX (RCCX): a mechanism for gene deletions and disease associations. J Biol Chem 274:12147–12156 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanchong CA, Zhou B, Rupert KL, Chung EK, Jones KN, Sotos JF, Rennebohm RM, Yu CY (2000) Deficiencies of human complement component C4A and C4B and heterozygosity in length variants of RP-C4-CYP21-TNX (RCCX) modules in Caucasians: the load of RCCX genetic diversity on MHC-associated disease. J Exp Med 191:2183–2196 10.1084/jem.191.12.2183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung EK, Yang Y, Rennebohm RM, Lokki ML, Higgins GC, Jones KN, Zhou B, Blanchong CA, Yu CY (2002) Genetic sophistication of human complement C4A and C4B and RP-C4-CYP21-TNX (RCCX) modules in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). Am J Hum Genet 71:823–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dangel AW, Mendoza AR, Baker BJ, Daniel CM, Carroll MC, Wu L-C, Yu CY (1994) The dichotomous size variation of human complement C4 gene is mediated by a novel family of endogenous retroviruses which also establishes species-specific genomic patterns among Old World primates. Immunogenetics 40:425–436 10.1007/BF00177825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu CY (1991) The complete exon-intron structure of a human complement component C4A gene: DNA sequences, polymorphism, and linkage to the 21-hydroxylase gene. J Immunol 146:1057–1066 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu CY, Blanchong CA, Chung EK, Rupert KL, Yang Y, Yang Z, Zhou B, Moulds JM (2002) Molecular genetic analyses of human complement components C4A and C4B. In: Rose NR, Hamilton RG, Detrick B (eds) Manuals of clinical laboratory immunology. 6th ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp 117–131 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung EK, Wu YL, Yang Y, Zhou B, Yu CY (2005) Human complement components C4A and C4B genetic diversities: complex genotypes and phenotypes. In: Coligan JE, Bierer BE, Margulis DH, Shevach EM, Strober W (eds) Current protocols in immunology. John Wiley & Sons, Edison, NJ, pp 13.8.1–13.8.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung EK, Yang Y, Rupert KL, Jones KN, Rennebohm RM, Blanchong CA, Yu CY (2002) Determining the one, two, three or four long and short loci of human complement C4 in a major histocompatibility complex haplotype encoding for C4A or C4B proteins. Am J Hum Genet 71:810–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider PM, Witzel-Schlomp K, Rittner C, Zhang L (2001) The endogenous retroviral insertion in the human complement C4 gene modulates the expression of homologous genes by antisense inhibition. Immunogenetics 53:1–9 10.1007/s002510000288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang Y, Chung EK, Zhou B, Blanchong CA, Yu CY, Füst G, Kovács M, Vatay A, Szalai C, Karádi I, et al (2003) Diversity in intrinsic strengths of the human complement system: serum C4 protein concentrations correlate with C4 gene size and polygenic variations, hemolytic activities and body mass index. J Immunol 171:2734–2745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gitelman SE, Bristow J, Miller WL (1992) Mechanism and consequences of the duplication of the human C4/P450c21/gene X locus. Mol Cell Biol 12:2124–2134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higashi Y, Yoshioka H, Yamane M, Gotoh O, Fujii-Kuriyama Y (1986) Complete nucleotide sequence of two steroid 21-hydroxylase genes tandemly arranged in human chromosome: a pseudogene and a genuine gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83:2841–2845 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White PC, Grossberger D, Onufer BJ, New MI, DuPont B, Strominger J (1985) Two genes encoding steroid 21-hydroxylase are located near the genes encoding the fourth component of complement in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82:1089–1093 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, Schaller JG, Talal N, Winchester RJ (1982) The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 25:1271–1277 10.1002/art.1780251101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sim E, Cross S (1986) Phenotyping of human complement component C4, a class III HLA antigen. Biochem J 239:763–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Awdeh ZL, Alper CA (1980) Inherited structural polymorphism of the fourth component of human complement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77:3576–3580 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laird NM, Lange C (2006) Family-based designs in the age of large-scale gene-association studies. Nat Rev Genet 7:385–394 10.1038/nrg1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weiss LA, Pan L, Abney M, Ober C (2006) The sex-specific genetic architecture of quantitative traits in humans. Nat Genet 38:218–222 10.1038/ng1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mackay TF (2004) The genetic architecture of quantitative traits: lessons from Drosophila. Curr Opin Genet Dev 14:253–257 10.1016/j.gde.2004.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu CY, Whitacre CC (2004) Sex, MHC and complement C4 in autoimmune diseases. Trends Immunol 25:694–699 10.1016/j.it.2004.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jacob CO, Fronek Z, Lewis GD, Koo M, Hansen JA, McDevitt HO (1990) Heritable major histocompatibility complex class II-associated differences in production of tumor necrosis factor a: relevance to genetic predisposition to systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:1233–1237 10.1073/pnas.87.3.1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hajeer AH, Hutchinson IV (2001) Influence of TNFα gene polymorphisms on TNFα production and disease. Hum Immunol 62:1191–1199 10.1016/S0198-8859(01)00322-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vatay A, Yang Y, Chung EK, Zhou B, Blanchong CA, Kovacs MK, Karadi I, Fust G, Romics L, Varga L, et al (2003) Relationship between complement components C4A and C4B diversities and two TNFA promoter polymorphisms in two healthy Caucasian populations. Hum Immunol 64:543–552 10.1016/S0198-8859(03)00036-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee YH, Nath SK (2005) Systemic lupus erythematosus susceptibility loci defined by genome scan meta-analysis. Hum Genet 118:434–443 10.1007/s00439-005-0073-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thorsby E (1997) HLA associated diseases. Hum Immunol 53:1–11 10.1016/S0198-8859(97)00024-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dawkins R, Leelayuwat C, Gaudieri S, Tay G, Hui J, Cattley S, Martinez P, Kulski J (1999) Genomics of the major histocompatibility complex: haplotypes, duplication, retroviruses and disease. Immunol Rev 167:275–304 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1999.tb01399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Graham RR, Ortmann WA, Langefeld CD, Jawaheer D, Selby SA, Rodine PR, Baechler EC, Rohlf KE, Shark KB, Espe KJ, et al (2002) Visualizing human leukocyte antigen class II risk haplotypes in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Hum Genet 71:543–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Awdeh ZL, Raum D, Yunis EJ, Alper CA (1983) Extended HLA/complement allele haplotypes: evidence for T/t-like complex in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 80:259 10.1073/pnas.80.1.259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Bakker PI, McVean G, Sabeti PC, Miretti MM, Green T, Marchini J, Ke X, Monsuur AJ, Whittaker P, Delgado M, et al (2006) A high-resolution HLA and SNP haplotype map for disease association studies in the extended human MHC. Nat Genet 38:1166–1172 10.1038/ng1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miretti MM, Walsh EC, Ke X, Delgado M, Griffiths M, Hunt S, Morrison J, Whittaker P, Lander ES, Cardon LR, et al (2005) A high-resolution linkage-disequilibrium map of the human major histocompatibility complex and first generation of tag single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet 76:634–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.The International HapMap Consortium (2005) A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature 437:1299–1320 10.1038/nature04226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stewart CA, Horton R, Allcock RJ, Ashurst JL, Atrazhev AM, Coggill P, Dunham I, Forbes S, Halls K, Howson JM, et al (2004) Complete MHC haplotype sequencing for common disease gene mapping. Genome Res 14:1176–1187 10.1101/gr.2188104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Traherne JA, Horton R, Roberts AN, Miretti MM, Hurles ME, Stewart CA, Ashurst JL, Atrazhev AM, Coggill P, Palmer S, et al (2006) Genetic analysis of completely sequenced disease-associated MHC haplotypes identifies shuffling of segments in recent human history. PLoS Genet 2:e9 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schur PH (1977) Complement testing in the diagnosis of immune and autoimmune diseases. Am J Clin Path 68:647–659 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Manzi S, Navratil JS, Ruffing MJ, Liu CC, Danchenko N, Nilson SE, Krishnaswami S, King DE, Kao AH, Ahearn JM (2004) Measurement of erythrocyte C4d and complement receptor 1 in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 50:3596–3604 10.1002/art.20561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Redon R, Ishikawa S, Fitch KR, Feuk L, Perry GH, Andrews TD, Fiegler H, Shapero MH, Carson AR, Chen W, et al (2006) Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature 444:444–454 10.1038/nature05329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stranger BE, Forrest MS, Dunning M, Ingle CE, Beazley C, Thorne N, Redon R, Bird CP, de GA, Lee C, et al (2007) Relative impact of nucleotide and copy number variation on gene expression phenotypes. Science 315:848–853 10.1126/science.1136678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]