Abstract

Aberrant methylation of promoter CpG islands of human genes has been known as an alternative mechanism of gene inactivation and contributes to the carcinogenesis in many human tumors. We attempted to determine the methylation status of 18 genes, or loci known to be frequently methylated in cancers of other organs, in 79 resected intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas and 15 normal bile duct epithelium by methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction and correlated the data with clinicopathological findings. Methylation frequencies of the loci tested in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas were 59.5% for 14-3-3sigma,26.6% for APC, 21.5% for E-cadherin, 17.7% for p16, 11.4% for MGMT, 11.4% for THBS1, 8.9% for p14, 8.9% for TIMP3, 7.6% for DAP-kinase,6.3% for GSTP1, 5.1% for COX-2, 50.6% for MINT12, 40.5% for MINT1, 15.4% for MINT25, 35.4% for MINT32, and 1.3% for MINT31. Sixty-two (78.5%) of the 79 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas had methylation in at least one of these loci. Methylation was not detected in normal bile duct samples. There was a significant correlation between methylation and expressional decrease or loss of p16, E-cadherin, and GSTP1 proteins (P = 0.028, P = 0.044, and P < 0.001, respectively). The overall survival was poorer in the patients with CpG island methylation of APC, p16, and TIMP3 than in the patients without methylation (Kaplan-Meier log-rank test, P = 0.0128, 0.0447, and 0.0137, respectively). Age, gender, tumor stage, gross type, histological type, and differentiation had no correlation with methylation status of the specific gene. These results suggest that methylation is a frequent event in cholangiocarcinomas and contributes to the cholangiocarcinogenesis, and that CpG island methylation of APC, p16, or TIMP-3 may serve as a potential prognostic biomarker of the cholangiocarcinomas.

Aberrant DNA methylation occurs commonly in human cancers in the form of genome-wide hypomethylation 1 and regional hypermethylation. 2 The latter usually occurs in CpG islands located in the promoter regions of the tumor suppressor genes, resulting in gene inactivation. Promoter CpG island hypermethylation acts as an alternative or complementary mechanism to gene mutations causing gene inactivation, and is now recognized as an important mechanism in carcinogenesis. 2 Multiple pathways involved in cell immortalization and transformations are affected by promoter CpG island methylation, including cell cycle regulation (p16 and p15), DNA repair and protection (hMLH1, MGMT, BRCA1, and GSTP1), cell adherence and metastasis process (E-cadherin, TIMP3, DAPK), and the APC/β-catenin route (APC). 3

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is the second most common tumor of primary liver cancers in the adult. Worldwide, it accounts for ∼15% of liver cancers 4 and the incidence has increased in recent years. 5 Despite improved diagnostic and operative techniques, the prognosis of ICC remains very poor. 5,6 Moreover, molecular events involved in the development of ICC are not well understood. The reported genetic alterations in ICC include mutation of K-ras (4.6 to 58%), p53 (10.7 to 33%), p16, and Smad-4 and loss of heterozygosity of APC (23.5%). 7-11 Little is currently known about the role of CpG island methylation in ICC, although a few studies have reported methylation of p16 gene in ICC. 12,13

In this study, to determine the role of aberrant methylation in ICC, 79 ICC samples were examined for the methylation status of CpG islands, in 6 MINT loci, and 12 tumor-related genes that are known to undergo epigenetic inactivation in other human cancers. The tested genes included those involved in cell cycle regulation (p14, p16, 14-3-3 sigma, and COX-2), signal transduction (APC and PTEN), DNA repair or protection (MGMTand GSTP1), apoptosis (DAP-kinase), and angiogenesis (THBS1) and those related to metastasis and invasion (E-cadherin and TIMP-3). In addition, we analyzed the relationship between the methylation status of the specific gene and the clinicopathological findings.

Materials and Methods

Samples and DNA Preparation

Seventy-nine archive samples of ICCs surgically resected at the Seoul National University Hospital between 1994 and 2001 were studied. Fifteen archive samples of hepatolithiasis were also studied as normal control: the median age of the hepatolithiasis patients was 52 years, with a range of 40 to 68 years. After identifying carcinoma on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, portions of carcinoma were scraped from 20-μm-thick paraffin sections. To obtain the normal bile duct epithelial cells in hepatolithiasis samples, microdissection was performed according to the manufacturer’s manual (PALM Laser-MicroBeam Systems; PALM Mikrolaser Technologie GmbH, Bernried, Germany). The materials collected were dewaxed by washing in xylene and then by rinsing in ethanol. The dried tissues were digested with proteinase K and subjected to the traditional method of DNA extraction using phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol and ethanol precipitation.

Methylation-Specific Polymerase Chain Reaction (MSP)

DNAs from tumor and normal tissues were subjected to sodium bisulfite modification as described previously. 14 MSP was performed to examine methylation at CpG islands of APC, COX-2, DAP-kinase, E-cadherin, GSTP1, MGMT, MINT1, MINT2, MINT12, MINT25, MINT31, MINT32, p14, p16, PTEN, 14-3-3 sigma, THBS1, and TIMP-3. The primer sequences of each locus, for both methylated and unmethylated reactions, are described in Table 1 ▶ . To amplify the bisulfite-modified promoter sequence of p16, E-cadherin, and COX-2, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mixture containing 1× PCR buffer [10 mmol/L Tris (pH 8.3), 50 mmol/L KCl, and 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2], deoxynucleotide triphosphates (each at 0.2 mmol/L), primers (10 pmol each), and bisulfite-modified DNA (30 to 50 ng) in a final volume of 25 μl was used. For amplification of APC, DAP-kinase, GSTP1, MGMT, MINT1, MINT2, MINT12, MINT25, MINT31, MINT32 clones, p14, PTEN, 14-3-3 sigma, THBS1, and TIMP3, a PCR mixture containing 1× PCR buffer [16.6 mmol/L (NH4)2SO4, 67 mmol/L Tris (pH 8.8), 6.7 mmol/L MgCl2, and 10 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol], deoxynucleotide triphosphates (each at 1 mmol/L), primers (10 pmol each), and bisulfite-modified DNA (30 to 50 ng) in a final volume of 25 μl was used. The reactions were hot-started at 98°C for 5 minutes before the addition of 0.75 U of Taq polymerase (Takara Shuzo Co., Kyoto, Japan). The amplifications were performed in a thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA) for 33 cycles (40 seconds at 95°C, 50 seconds at variable temperatures according to primer, and 50 seconds at 72°C) with a final 10-minute extension. The PCR products underwent electrophoresis on a 2.5% agarose gel, then were visualized under UV illumination using an ethidium bromide stain. Samples showing signals approximately equivalent to that of the size marker (7 ng/μl) were scored as methylated. Samples giving faint positive signals were repeated three times and only those samples with consistent positive signals were scored as methylated.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences and PCR Conditions for MSP Analysis

| Primer name* | Primer sequence (5′-3′) Forward | Primer sequence (5′-3′) Reverse | Product size (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC | m | TATTGCGGAGTGCGGGTC | TCGACGAACTCCCGACGA | 98 | 55 |

| u | GTGTTTTATTGTGGAGTGTGGGTT | CCAATCAACAAACTCCCAACAA | 108 | 55 | |

| COX-2 | m | TTAGATACGGCGGCGGCGGC | TCTTTACCCGAACGCTTCCG | 161 | 61 |

| u | ATAGATTAGATATGGTGGTGGTGGT | CACAATCTTTACCCAAACACTTCCA | 172 | 61 | |

| DAP-kinase | m | GGATAGTCGGATCGAGTTAACGTC | CCCTCCCAAACGCCGA | 98 | 60 |

| u | GGAGGATAGTTGGATTGAGTTAATGTT | CAAATCCCTCCCAAACACCAA | 106 | 60 | |

| E-cadherin | m | TTAGGTTAGAGGGTTATCGCGT | TAACTAAAAATTCACCTACCGAC | 115 | 57 |

| u | TAATTTTAGGTTAGAGGGTTATTGT | CACAACCAATCAACAACACA | 97 | 53 | |

| GSTP1 | m | TTCGGGGTGTAGCGGTCGTC | GCCCCAATACTAAATCACGACG | 91 | 59 |

| u | GATGTTTGGGGTGTAGTGGTTGTT | CCACCCCAATACTAAATCACAACA | 97 | 59 | |

| MGMT | m | TTTCGACGTTCGTAGGTTTTCGC | GCACTCTTCCGAAAACGAAACG | 81 | 59 |

| u | TTTGTGTTTTGATGTTTGTAGGTTTTTGT | AACTCCACACTCTTCCAAAAACAAAACA | 93 | 59 | |

| MINT1 | m | AAAAAAAAACACCTAAAACTCA | CTACTTCGCCTAACCTAACG | 102 | 64 |

| u | GGGGTTGAGGTTTTTTGTTAGT | TTCACAACCTCAAATCTACTTCA | 117 | 64 | |

| MINT2 | m | AATCGAATTTGTCGTCGTTTC | AAATAAATAAATAAAAAAAAACGCG | 88 | 60 |

| u | GGTGTTGTTAAATGTAAATAATTTG | AAAAAAAAACACCTAAAACTCA | 88 | 58 | |

| MINT12 | m | TTGGGAGTTTATTTAGGTCG | ACAACGATCTTCCGAATTTA | 152 | 55 |

| u | TGGGAGTTTATTTAGGTTGG | AAACACAACAATCTTCCAAAT | 155 | 55 | |

| MINT25 | m | GTTCGTTAGAGTAATTTTGCG | TTATAACTAACGAAACACCGC | 128 | 55 |

| u | AGTAATTTTGTGGTGGAAGG | ACTAACAAAACACCACACCC | 114 | 55 | |

| MINT31 | m | TTGAGACGATTTTAATTTTTTGC | AAAACCATCACCCCTAAACG | 100 | 62 |

| u | GAATTGAGATGATTTTAATTTTTTGT | CTAAAACCATCACCCCTAAACA | 105 | 64 | |

| MINT32 | m | GATGTTAGAGGAATTTAGGC | AAAACGAACGAAACGTCCG | 126 | 64 |

| u | GAGTGGTTAGAGGAATTTAGGT | CTAAAAAAACAAACAAAACATCCA | 133 | 62 | |

| p14 | m | GTGTTAAAGGGCGGCGTAGC | AAAACCCTCACTCGCGACGA | 122 | 60 |

| u | TTTTTGGTGTTAAAGGGTGGTGTAGT | CACAAAAACCCTCACTCACAACAA | 132 | 60 | |

| p16 | m | TTATTAGAGGGTGGGGCGGATCGC | GACCCCGAACCGCGACCGTAA | 150 | 65 |

| u | TTATTAGAGGGTGGGGTGGATTGT | CAACCCCAAACCACAACCATAA | 151 | 60 | |

| PTEN | m | TTTTTTTTCGGTTTTTCGAGGC | CAATCGCGTCCCAACGCCG | 134 | 59 |

| u | TTTTGAGGTGTTTGGGTTTTTGGT | ACACAATCACATCCCAACACCA | 124 | 59 | |

| 14-3-3 sigma | m | TGGTAGTTTTTATGAAAGGCGTC | CCTCTAACCGCCCACCACG | 105 | 56 |

| u | ATGGTAGTTTTTATGAAAGGTGTT | CCCTCTAACCACCCACCACA | 106 | 56 | |

| THBS1 | m | TGCGAGCGTTTTTTTAAATGC | TAAACTCGCAAACCAACTCG | 74 | 62 |

| u | GTTTGGTTGTTGTTTATTGGTTG | CCTAAACTCACAAACCAACTCA | 115 | 62 | |

| TIMP3 | m | CGTTTCGTTATTTTTTGTTTTCGGTTTTC | CCGAAAACCCCGCCTCG | 116 | 59 |

| u | TTTTGTTTTGTTATTTTTTGTTTTTGGTTTT | CCCCCAAAAACCCCACCTCA | 122 | 59 |

*m, Methylated sequence; u, unmethylated sequence.

Sequencing Analysis

The MSP products were purified using JET-SORB gel extraction kit (Genomed, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany) and sequenced using ABI Prism Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kits (Perkin-Elmer) and an ABI Prism 377 DNA Sequencer (Perkin-Elmer).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5-μm formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections, using mouse monoclonal anti-p16 (SC1661, at a dilution of 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse monoclonal anti-GSTP1 (clone 3, at a dilution of 1:2000; Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), and mouse monoclonal anti-E-cadherin antibodies (HECD-1, at a dilution of 1:500; Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA). The reaction was visualized with a Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Formalin-fixed paraffin sections of normal human liver were used as positive controls.

Analysis for Clinicopathological Data and Statistics

Clinical and pathological parameters of ICCs, including patient’s age at initial diagnosis, gender, gross type, 15 tumor size, tumor differentiation, and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage 16 and the postoperative survival time, were assessed. Statistical analyses were performed using the chi-square and Fisher’s exact test, for differences between groups, and Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U-tests, for those between means. Overall survival was calculated using Kaplan-Meier log-rank testing.

Results

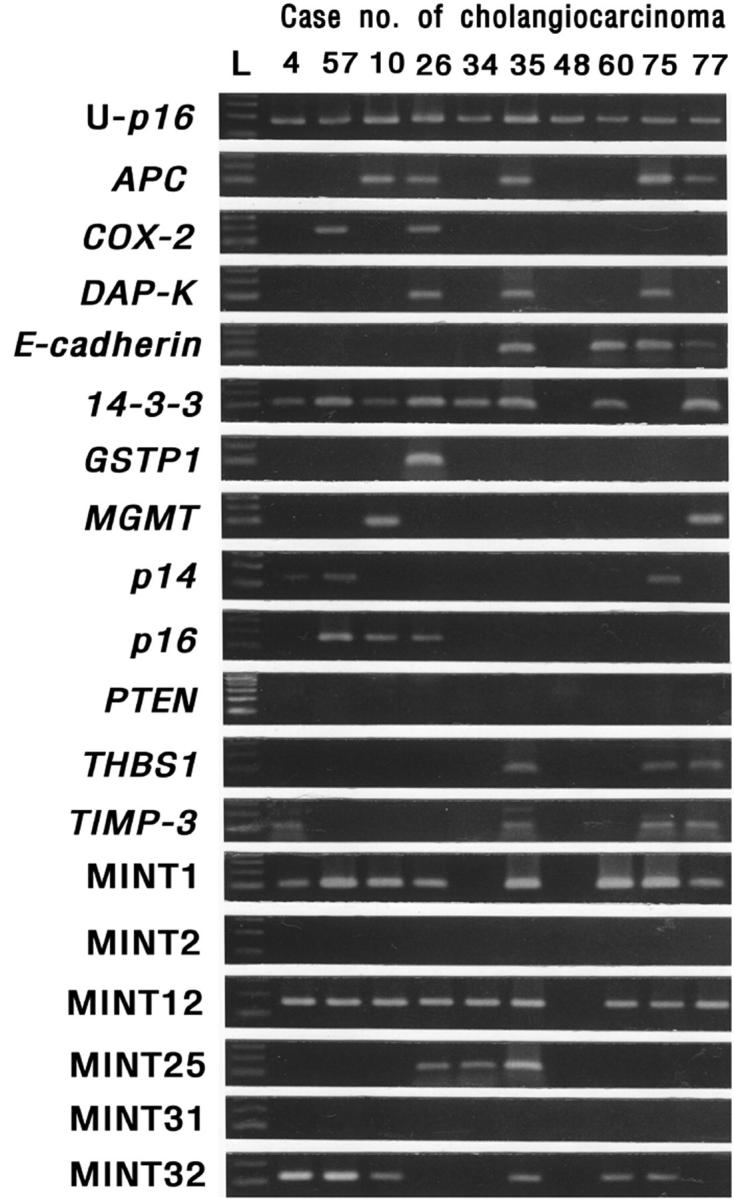

MSP and Sequencing

The results of the MSP for 18 loci are shown in Table 2 ▶ . A total of 62 (78.5%) of the 79 primary ICCs showed methylation in at least one of these loci. DNA hypermethylation was not detected in 17 cases (21.5%). The methylation frequency of each locus varied from 0 to 59.5%. Representative examples of the MSP analyses are shown in Figure 1 ▶ . A high frequency of methylation (>40%) was detected in 14-3-3 sigma (59.5%), MINT12 (50.6%), and MINT1 (40.5%). An intermediate frequency of methylation (15 to 40%) was found in MINT32 (35.4%), APC (26.6%), E-cadherin (21.5%), and p16 (17.7%). The remaining loci showed methylation frequencies of less than 15%, and PTEN and MINT2 showed no methylation at all. The frequency of methylation for multiple loci in a tumor was estimated using the methylation index (the number of loci methylated divided by the total number of loci tested), which ranged from 0 to 0.56, with a mean of 0.18. When DNA from normal bile duct epithelial cells was tested for the 18 loci, there were no positive signals for the normal samples.

Table 2.

Summary of MSP Results and Concordance Tests of Each Locus in Cholangiocarcinoma Samples

| Locus | Frequency of methylation (n = 79) | Concordance*† | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14-3-3 sigma | 47 (59.5%) | + | <0.001 |

| APC | 21 (26.6%) | + | <0.001 |

| E-cadherin | 17 (21.5%) | + | 0.002 |

| p16 | 14 (17.7%) | + | 0.002 |

| MGMT | 9 (11.4%) | + | 0.036 |

| THBS1 | 9 (11.4%) | + | 0.003 |

| p14 | 7 (8.9%) | +/− | NS‡ |

| TIMP3 | 7 (8.9%) | + | 0.001 |

| DAP-kinase | 6 (7.6%) | + | <0.001 |

| GSTP1 | 5 (6.3%) | + | 0.038 |

| COX-2 | 4 (5.1%) | + | 0.019 |

| PTEN | 0 | n/a§ | n/a |

| MINT1 | 32 (40.5%) | + | <0.001 |

| MINT12 | 40 (50.6%) | + | <0.001 |

| MINT25 | 12 (15.4%) | + | 0.023 |

| MINT31 | 1 (1.3%) | +/− | NS |

| MINT32 | 28 (35.4%) | + | <0.001 |

| MINT2 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

*Mann-Whitney U-test was used for concordance with methylation at any other locus.

†+, Statistically significant association with methylation at the other loci; +/−, an increased association with methylation at the other loci but the levels did not reach significance.

‡Not significant.

§Not applicable.

Figure 1.

MSP analysis of APC, COX-2, DAP kinase, E-cadherin, 14-3-3 sigma, GSTP1, MGMT, p14, p16, PTEN, THBS1, TIMP3, and the MINT1, 2, 12, 25, 31, and 32 clones. DNA extracted from cholangiocarcinomas was amplified with primers specific to the unmethylated (U) or the methylated CpG islands of each gene after modification with sodium bisulfite. L, molecular weight marker. U-p16, PCR results for unmethylated sequence of p16.

The genomic sequencing of representative PCR products of all of the tested loci showed that all cytosines, at non-CpG sites, were converted to thymine. This excluded the possibility that successful amplification could be attributable to incomplete bisulfite conversion. Representative PCR products for each locus showed 100% methylation of the CpG sites located inside the amplified genomic fragments. The results for the MSP and bisulfite sequencing analyses were consistent, indicating it is appropriate to draw inferences from the results of MSP regarding the methylation status of the gene promoters.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

The methylation status was correlated with the protein expression in p16, E-cadherin, and GSTP1, for the 79 ICC samples, using immunohistochemistry. We defined the expression status as positive or reduced for ≥80%, or <80% of tumor cells with positive staining, respectively. Table 3 ▶ shows the results for the immunohistochemistry of three proteins and their relationship with the MSP results. A close correlation was noted between methylation of p16, E-cadherin, and GSTP1 and reduced expression of the corresponding protein (Fisher’s exact test; P = 0.028, 0.044, and <0.001, respectively).

Table 3.

Correlation of MSP Results with Protein Expression in Cholangiocarcinoma Samples

| Protein | Expression status | MSP results | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | |||

| p16 | + | 2 | 28 | 0.028 |

| − | 11 | 26 | ||

| E-cadherin | + | 2 | 24 | 0.044 |

| − | 15 | 38 | ||

| GSTP1 | + | 0 | 65 | <0.001 |

| − | 5 | 6 | ||

*Fisher’s exact test.

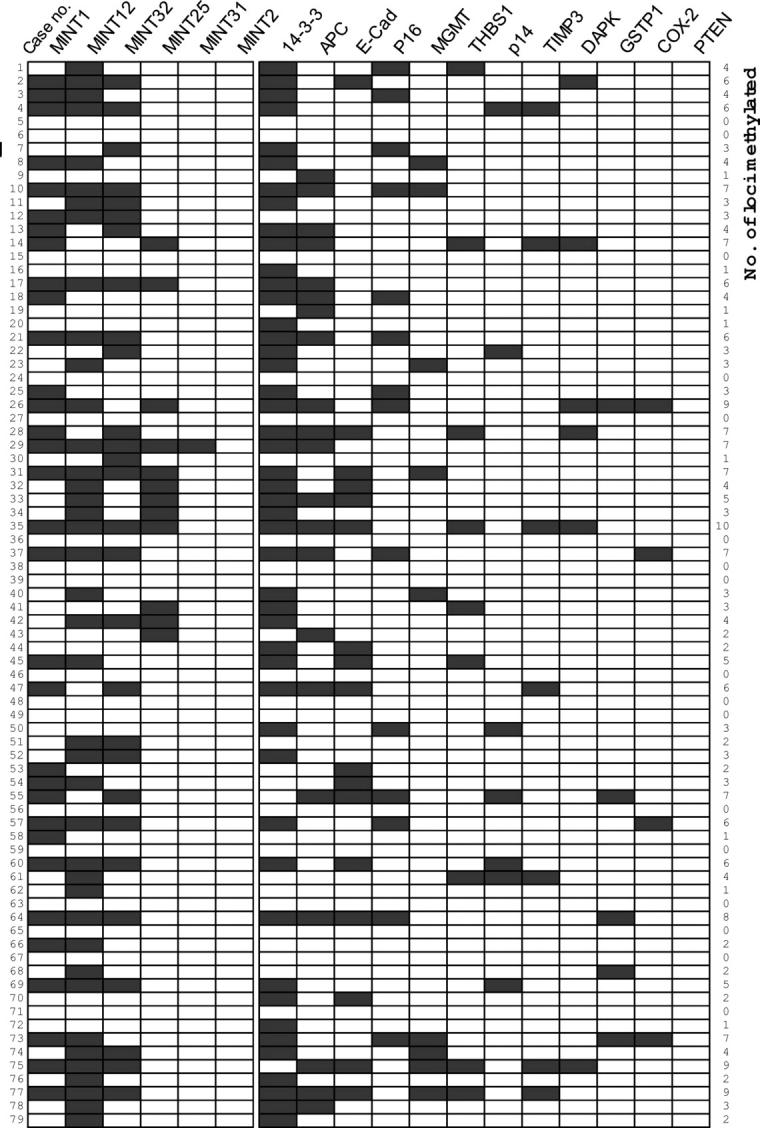

Analysis of Methylation Distribution and CpG Island Methylator Phenotype (CIMP)

CpG island hypermethylation tended to be clustered in specific cases (Figure 2) ▶ . To determine the coordination of methylation at multiple loci, we compared the frequency with which other loci were methylated when a specific locus was either methylated or not. Methylation at each locus was associated with higher methylation frequency at the other loci. Fourteen loci except for p14 and MINT31, which were methylated at a frequency less than 9%, exhibited a statistically significant association with tumors showing methylation of at least one other locus (Table 2) ▶ .

Figure 2.

Summary of methylation analysis of APC, COX-2, E-cadherin, DAP-kinase, GSTP1, MGMT, p14, p16, PTEN, 14-3-3 sigma, THBS1, TIMP3, and MINT1, 12, 25, 31, 32, and 2 clones in 79 cholangiocarcinoma samples. A filled box indicates the presence of methylation and an open box indicates the absence of methylation. 14-3-3, 14-3-3 sigma; E-cad, E-cadherin; DAPK, DAP-kinase.

To determine CIMP in ICCs, six MINT loci that were frequently methylated in colorectal and gastric cancers were selected for analysis. Four MINT loci were methylated at a frequency more than 15%, with MINT2 not being methylated at all, and MINT31 methylated only once (Table 2) ▶ . Methylation at each of these MINT loci exhibited significant concordance with methylation at three or more loci other than MINT clones (data not shown). Tumors with methylation at three or more of the five MINT loci, except for MINT2, were defined as CIMP+. CIMP− tumors were defined as those with methylation at less than three MINT loci. Eighteen (22.8%) of the 79 cases were classed as CIMP+ tumors. When we analyzed the relationship between CIMP status and methylation of the 12 tumor-related genes, CIMP+ tumors showed a greater number of methylated genes than those for CIMP− tumors; CIMP + tumors exhibited an average of 3.4 methylated genes per 12 genes tested, whereas CIMP-negative tumors (n = 61) exhibited an average of 1.3 per 12 genes (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001). With respect to clinicopathological factors, no significant association with CIMP was found, except for the histological type (Table 4) ▶ . All of the ICCs of the papillary type (n = 10) were CIMP− tumors, and showed lower than average methylation index, 0.11, the average methylation index of the other histological types was 0.19 (P = 0.064). These cases were identical to the ICCs of intraductal growth type on macroscopic classification.

Table 4.

Relationship between CIMP and Clinicopathological Data

| CIMP+ (n = 18) | CIMP− (n = 61) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male:female ratio | 14:4 | 48:13 | NS |

| Mean age (years) | 59.7 | 58.3 | NS |

| pTNM stage | NS | ||

| I (n = 2) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.4%) | |

| II (n = 3) | 1 (5.6%) | 2 (3.4%) | |

| III (n = 34) | 7 (38.9%) | 27 (46.6%) | |

| IV (n = 37) | 10 (55.6%) | 27 (46.6%) | |

| Gross type* | NS | ||

| ID (n = 11) | 0 (0%) | 11 (18.0%) | |

| MF (n = 39) | 13 (72.2%) | 26 (42.6%) | |

| PI (n = 22) | 4 (22.2%) | 18 (29.5%) | |

| Mixed MF & PI (n = 7) | 1 (5.6%) | 6 (9.8%) | |

| Differentiation† | NS | ||

| WD (n = 6) | 0 (0%) | 6 (10.0%) | |

| MD (n = 53) | 11 (61.1%) | 42 (70.0%) | |

| PD (n = 19) | 7 (38.9%) | 12 (20.0%) | |

| Histologic type | 0.013 | ||

| Tubular or tubulopapillary (n = 64) | 16 (88.9%) | 48 (78.7%) | |

| Papillary (n = 10) | 0 (0%) | 10 (16.4%) | |

| Sarcomatoid (n = 2) | 2 (11.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Unclassified (n = 3) | 0 | 3 (4.9%) | |

| Average no. of genes methylated (n = 12) | 3.4 | 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Average postoperative survival time (months) | 14.1 | 20.7 | NS |

*ID, Intraductal growth type; MF, mass-forming type; PD, periductal-infiltrating type.

†WD, well differentiated; MD, moderately differentiated; PD, poorly differentiated.

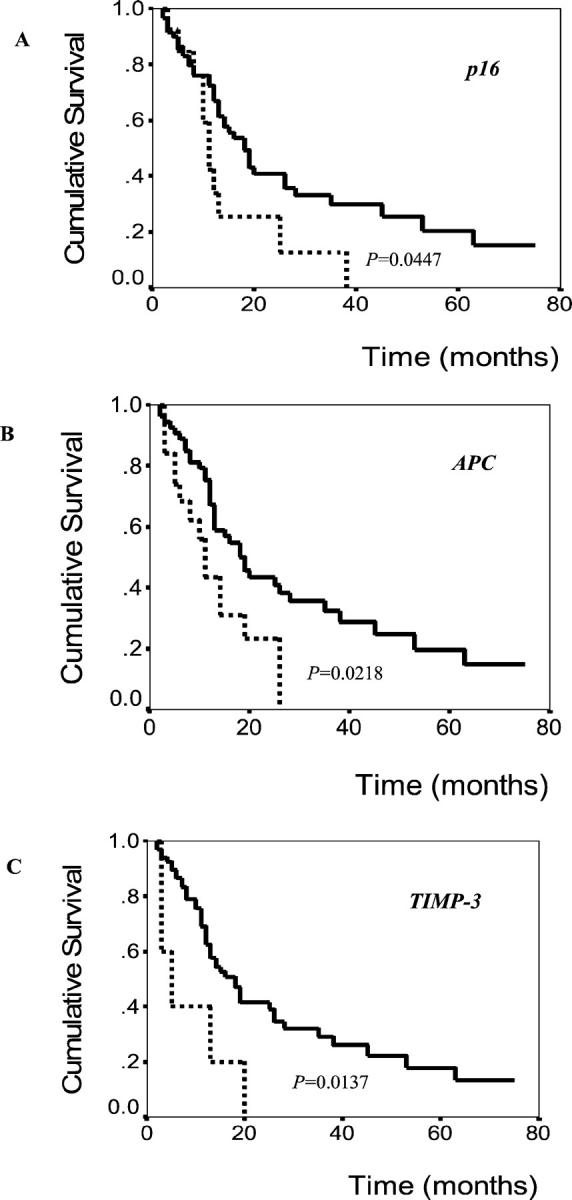

Clinicopathological Correlations with Methylation Status of Genes

Regardless of the type of loci tested, the patients with methylation of a specific gene or locus tended to be older than those without, although these differences were not statistically significant. Only 14-3-3 sigma was morefrequently methylated in female patients than in male (82.4% and 53.2%, respectively; Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.049). Survival tended to be poorer in patients with methylation of a specific gene than those patients without, although statistically significance results were observed in APC, p16, and TIMP3 with P = 0.0128, 0.0447, and 0.0137, respectively, via Kaplan-Meier log-rank tests (Figure 3) ▶ . With respect to other clinicopathological factors such as tumor size, tumor differentiation, gross type, and pTNM stage, there was no significant association with methylation status of each locus.

Figure 3.

Overall survival of cholangiocarcinoma patients according to methylation status of p16 (A), APC (B), and TIMP3 (C) genes. Solid line, patients without methylation of examined gene; dotted line, patients with methylation of examined gene.

When the methylation data on genes only (with exclusion of data on MINT loci) were analyzed, the number of methylated genes in each case ranged from zero to six in a spectrum. When ICCs were divided into two groups, ICCs with methylation at four or more genes and ICCs with methylation at less than four genes, a significant prognostic difference was found. The former group showed worse survival than the latter group (median survival, 5 months versus 18 months, respectively; P = 0.0062, Kaplan-Meier log-rank test). However, other clinicopathological findings do not show significant differences between two groups.

Discussion

In this study, a large collection of ICC samples was analyzed for their methylation status of a panel of genes or loci, found to be frequently methylated in other human cancer tissue and cancer cell lines. ICC samples (78.5%) were methylated in one or more loci, and the number of methylated locus averaged 3.3 per 18 tested loci, ranging from 0 to 10. Thirteen cases (16.5%) showed concordant methylation of seven or more loci. In contrast, normal bile duct epithelium samples did not show methylation at any tested loci. The data indicates that aberrant CpG island methylation is a frequent and tumor-related change in ICC.

Our results show a clear correlation of methylation for three genes with the expressional decrease or loss of the corresponding gene products. However, 2 (15%) of the 13 cases with p16 methylation and 2 (12%) of the 17 cases with E-cadherin methylation, showed no reduced expression of the corresponding protein despite the presence of promoter hypermethylation of the specific genes. This can be explained by the heterogeneity of the methylation status of tumor cell clones. Some tumor cells had aberrant methylation of specific CpG islands, which was amplified by MSP, whereas most of the tumor cells had no methylation of the specific CpG islands. Another possibility is that methylation did not occur in the critical site for gene silencing. By contrast, 26 (48%) of the 54 cases with no p16 methylation and 38 (61%) of the 62 cases with no E-cadherin methylation showed reduced expression or loss of p16 or E-cadherin protein, respectively. This may be because of inactivation of the gene by genetic alterations such as mutation, or deletion, of genes, instead of epigenetic change. In a previous study, 17 we analyzed 36 samples of ICCs, for loss of heterozygosity by PCR amplification of three microsatellite markers located at 9p21-22, and found that 13 (68.4%) of the 19 informative ICCs examined showed loss of heterozygosity for at least one of the markers in this region. The data suggests that in ICC, genetic alteration, such as allelic loss, may be a dominant mechanism for p16 inactivation rather than p16 hypermethylation. Our present and previous results, on genetic or epigenetic change of p16 gene, are in contrast to those of Tannapfel and colleagues 12 that demonstrated that p16 hypermethylation in ICC was found in 83% of cases, whereas homozygous deletion and loss of heterozygosity of p16 were detected in 5% and 20%, respectively. The frequency of p16 hypermethylation in the study of Tannapfel and colleagues 12 differs markedly from the results of other authors (25%) in cholangiocarcinoma. 13 Esteller and colleague’s 3 study, which analyzed promoter hypermethylation of p16 and other 11 genes in 15 major human tumor types, found that the frequency of p16 hypermethylation ranged from 1 to 48% in the 15 types of tumor.

A recent study 18 demonstrated that hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) had a high frequency of aberrant methylation of multiple genes. To compare the methylation frequency and tumor-type-specific methylation profile between HCC and ICC, we studied the methylation status of eight genes (APC, COX-2, DAP-kinase, E-cadherin, GSTP1, p14, p16, 14-3-3 sigma) in 40 cases of HCC (data not shown). The methylation frequency of the eight genes ranged from 14.3 to 94.9%. HCC showed greater methylation frequency of APC, E-cadherin, GSTP1, p16, and 14-3-3 sigma than ICCs (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P = 0.001, and P = 0.001, respectively). The average number of methylated genes per eight genes tested was 3.9 and 0.7 for HCC and ICC, respectively (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001). These results show tumor-type-specific difference for methylation tendency within the same organ. The higher frequency of aberrant methylation shown in HCCs compared to that in ICCs seems to be related to the difference of cell of origin or etiological factors. However, the former is unlikely because both hepatocytes and bile duct epithelial cells are presumed to be derived from common progenitor (stem) cells. 19 In this study, 85% of the cases of HCC were positive for hepatitis B or C virus, whereas only 15% of the cases of ICC were. The relationship between aberrant methylation tendency and virus-related human cancers has been demonstrated in Epstein-Barr virus-positive gastric carcinoma, 20 Simian virus 40-positive mesothelioma, 21 and a lymphoma cell line infected by retrovirus. 22

Significant associations, between adverse survival of patients, and promoter hypermethylation of the specific genes, have been reported in human cancers. APC hypermethylation in tumor, or serum, was reported to be associated with inferior survival in non-small-cell lung cancer, 23 or esophageal adenocarcinoma, 24 respectively. p16 hypermethylation was also reported to be associated with poor survival in colon cancer. 25 Our data demonstrated that hypermethylation of APC, p16, or TIMP-3 was significantly associated with a worse clinical outcome. However, the prognostic significance of TIMP-3 hypermethylation in human cancers has not been reported yet. Although underlying mechanisms for such association are unclear, the present findings may add important biomarkers to a few known prognostic factors of ICC, including TNM staging and gross type. 26,27 Additional studies will be required to assess the clinical importance of the present findings.

The current evidence supports that subsets of colorectal and gastric cancers harbor the CIMP+ tumors, 28,29 even though their clinicopathological significance has not yet been clarified. In this study, we determined CIMP+ ICCs in 22.8% (18 of 79) of cases. However, the CIMP status did not show any significant correlation with clinicopathological parameters, with the exception of histological or gross types. All ICC of the papillary or intraductal growth type were CIMP− tumors, showed lower methylation index, and a more favorable prognosis than other gross types (data not shown). CpG island methylation does not seem to be an important mechanism in the carcinogenesis of ICC of the intraductal growth type. Genetic mechanisms other than CpG island hypermethylation may be involved in its carcinogenesis.

In conclusion, we addressed the issue of CpG island methylation in ICCs by studying methylation status of 18 CpG islands using MSP. We found that CpG island methylation is a frequent and cancer-specific change, and a statistically significant correlation exists between outcome and methylation status of APC, p16, or TIMP-3. These results suggested that DNA methylation might be a potential prognostic marker in ICC and an important mechanism contributing to carcinogenesis of ICC.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Gyeong Hoon Kang, M.D., Department of Pathology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 28 Yongon-dong, Chongno-gu, Seoul, 110-744, Korea. E-mail: ghkang@snu.ac.kr.

Supported in part by a research grant from the Cancer Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, and by a BK21 project for Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmacy, Seoul, Korea.

References

- 1.Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B: Hypomethylation distinguishes genes of some human cancers from their normal counterparts. Nature 1983, 301:89-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baylin SB, Herman JG, Graff JR, Vertino PM, Issa JPJ: Alterations in DNA methylation—a fundamental aspect of neoplasia. Adv Cancer Res 1998, 72:141-196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esteller M, Corn PG, Baylin SB, Herman JG: A gene hypermethylation profile of human cancer. Cancer Res 2001, 61:3225-3229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen MF: Peripheral cholangiocarcinoma (cholangiocellular carcinoma): clinical features, diagnosis and treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999, 14:1144-1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel T: Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology 2001, 33:1353-1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isaji S, Kawarada Y, Taoka H, Tabata M, Suzuki H, Yokoi H: Clinicopathological features and outcome of hepatic resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat 1999, 6:108-116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang YK, Kim WH, Lee HW, Lee HK, Kim Y: Mutation of p53 and K-ras, and loss of heterozygosity of APC in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Lab Invest 1999, 79:477-483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiba T, Tsuda H, Pairojkul C, Inoue S, Sugimura T, Hirohashi S: Mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene and the ras gene family in intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinomas in Japan and Thailand. Mol Carcinog 1993, 8:312-318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirohito M, Tomoko I, Yoshihiro N, Yuriko A, Hiroshi O, Seiji S, Yoshinobu T, Eiichi S, Kanichi N, Peer F, Masayuki Y, Yasuyuki S, Yoshio Y, Manabu F: Microsatellite instability and alternative genetic pathway in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol 2001, 35:235-244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida S, Todoroki T, Ichikawa Y, Hanai S, Suzuki H, Hori M, Fukao K, Miwa M, Uchida K: Mutations of p16Ink4/CDKN2 and p15Ink4B/MTS2 genes in biliary tract cancers. Cancer Res 1995, 55:2756-2760 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn SA, Bartsch D, Schroers A, Galehdari H, Becker M, Ramaswamy A, Schwarte-Waldhoff I, Maschek H, Schmiegel W: Mutations of the DPC4/Smad4 gene in biliary tract carcinoma. Cancer Res 1998, 58:1124-1126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tannapfel A, Benicke M, Katalinic A, Uhlmann D, Kockerling F, Wittekind C: Frequency of p16 (INK4A) alterations and K-ras mutation in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma of the liver. Gut 2000, 47:721-727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahrendt SA, Eisenberger CF, Yip L, Rashid A, Chow JT, Pitt HA, Sidransky D: Chromosome 9p21 loss and p16 inactivation in primary sclerosing cholangitis-associated cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Res 1999, 84:88-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermans JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB: Methylation-specific PCR. A novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:9821-9826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.: The Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan: Macroscopic classification for cholangiocellular carcinoma (intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma). The General Rules for the Clinical and Pathological Study of Primary Liver Cancer (Suppl). 1994. Kanehara, Tokyo

- 16.Hermanek P, Hutter RVP, Sobin LH, Wagner G, Wittekind CH: TNM Atlas, UICC, ed 4 1997:pp 115-123 Springer, Berlin

- 17.Kang YK, Kim YI, Kim WH: Alleotype analysis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 2000, 13:627-631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondo Y, Kanai Y, Sakamoto M, Mizokami M, Ueda R, Hirohashi S: Genetic instability and aberrant methylation in chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis—a comprehensive study of loss of heterozygosity and microsatellite instability at 39 loci and DNA hypermethylation on 8 CpG islands in microdissected specimens from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2000, 32:970-979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haruna Y, Saito K, Spaulding S, Nalesnik MA, Gerber MA: Identification of bipotential progenitor cells in human liver development. Hepatology 1996, 23:476-481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang GH, Lee S, Kim WH, Lee HW, Kim JC, Rhyu MG, Ro JY: EBV-positive gastric carcinoma demonstrates frequent aberrant methylation of multiple genes and constitutes CpG island methylator phenotype-positive gastric carcinoma. Am J Pathol 2002, 160:787-794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toyooka S, Pass HI, Shivapurkar N, Fukuyama Y, Maruyama R, Toyooka KO, Gilcrease M, Farinas A, Minna JD, Gazdar AF: Aberrant methylation and simian virus 40 tag sequences in malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Res 2001, 61:5727-5730 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang JY, Mikovits JA, Bagni R, Petrow-Sadowski CL, Ruscetti FW: Infection of lymphoid cells by integration-defective human immunodeficiency virus type 1 increases de novo methylation. J Virol 2001, 75:9753-9761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brabender J, Usadel H, Danenberg KD, Metzger R, Schneider PM, Lord RV, Wickramasinghe K, Lum CE, Park J, Salonga D, Singer J, Sidransky D, Holscher AH, Meltzer SJ, Danenberg PV: Adenomatous polyposis coli gene promoter hypermethylation in non-small cell lung cancer is associated with survival. Oncogene 2001, 20:3528-3532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawakami K, Brabender H, Lord RV, Groshen S, Greenwald BD, Krasna MJ, Yin J, Fleisher AS, Abraham JM, Beer DG, Sidransky D, Huss HT, Demeester TR, Eads C, Laird PW, Ilson DH, Kelsen DP, Harpole D, Moore MB, Danenberg KD, Danenberg PV, Meltzer SJ: Hypermethylated APC DNA in plasma and prognosis of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000, 92:1805-1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esteller M, Gonzalez S, Risques RA, Marcuello E, Mangues R, Germa JR, Herman JG, Capella G, Peinado MA: K-ras and p16 aberrations confer poor prognosis in human colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001, 19:299-304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isa T, Kusano T, Shimoji H, Takeshima Y, Muto Y, Furukawa M: Predictive factors for long-term survival in patients with intrahepatic ICC. Am J Surg 2001, 181:507-511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suh KS, Roh HR, Koh YT, Lee KU, Park YH, Kim SW: Clinicopathologic features of the intraductal growth type of peripheral cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2000, 31:12-17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toyota M, Ahuja N, Suzuki H, Itoh F, Ohe-Toyota M, Imai K, Baylin SB, Issa JP: Aberrant methylation in gastric cancer associated with the CpG island methylator phenotype. Cancer Res 1999, 59:5438-5442 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JP: CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:8681-8686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]