Abstract

Genomic instability can generate chromosome breakage and fusion randomly throughout the genome, frequently resulting in allelic imbalance, a deviation from the normal 1:1 ratio of maternal and paternal alleles. Allelic imbalance reflects the karyotypic complexity of the cancer genome. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that tissues with more sites of allelic imbalance have a greater likelihood of having disruption of any of the numerous critical genes that cause a cancerous phenotype and thus may have diagnostic or prognostic significance. For this reason, it is desirable to develop a robust method to assess the frequency of allelic imbalance in any tissue. To address this need, we designed an economical and high-throughput method, based on the Applied Biosystems AmpFlSTR Identifiler multiplex polymerase chain reaction system, to evaluate allelic imbalance at 16 unlinked, microsatellite loci located throughout the genome. This method provides a quantitative comparison of the extent of allelic imbalance between samples that can be applied to a variety of frozen and archival tissues. The method does not require matched normal tissue, requires little DNA (the equivalent of ∼150 cells) and uses commercially available reagents, instrumentation, and analysis software. Greater than 99% of tissue specimens with ≥2 unbalanced loci were cancerous.

It is widely accepted that genomic instability—the duplication, loss, or structural rearrangement of a critical gene(s)—occurs in virtually all cancers1 and in some instances has diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive significance. Thus, it is not surprising that tumor progression is reflected by allelic losses or gains in genes that regulate aspects of cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, invasion, and, ultimately, metastasis.2,3

There are several technologies available to detect chromosomal copy number changes in tumor cells. For example, chromosome painting techniques can identify chromosomal copy number changes in cytological preparations.4,5 Segmental genomic alterations can be identified by comparative genomic hybridization (CGH). CGH identifies copy number changes by detecting DNA sequence copy variations throughout the entire genome and mapping them onto a cytogenetic map supplied by metaphase chromosomes.6 On the other hand, array CGH maps copy number aberrations relative to the genome sequence by using arrays of bacterial artificial chromosome or cDNA clones as the hybridization target instead of the metaphase chromosomes.7,8,9,10,11 However, these methods cannot identify all cases of allelic imbalance (AI), which is a deviation from the normal 1:1 ratio of maternal and paternal alleles, for instance, in cases with uniparental disomy. In addition, these methods are poorly suited for high-throughput applications, and analysis is limited to a relatively small cellular field, thus increasing potential sampling error.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays can be used for high-resolution genome-wide genotyping and loss of heterozygosity detection.12,13,14 For example, the development of a panel of 52 microsatellite markers that detects genomic patterns of loss of heterozygosity15,16,17 has been used for breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis. However, this approach requires matched referent (normal) DNA, typically blood or buccal samples, and these cancer-type-specific panels may not be informative for other cancers, thus limiting their applicability across multiple tumor types. Larger panels of SNPs may be used for genome-wide analysis, for example, the Affymetrix 10K and 100K SNP mapping arrays.18,19 Likewise, Illumina BeadArrays with a SNP linkage-mapping panel20 allow allelic discrimination directly on short genomic segments surrounding the SNPs of interest, thus overcoming the need for high-quality DNA.14 Lips and colleagues21 have shown that Illumina BeadArrays can be used to obtain reliable genotyping and genome-wide loss of heterozygosity profiles from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) normal and tumor tissues. However, all these approaches, although robust, require costly reagents and specialized equipment, and the sheer amount of data produced from these analyses complicate the interpretation of results.

For these reasons, and as outlined by Davies and colleagues,22 it is desirable to develop a general, economical, and high-throughput method to assess the frequency of AI in any tissue, independent of the nature and composition of the specimen and the availability of matched, normal tissue. To address this need, we developed a method to measure the ratio of maternal and paternal alleles at 16 unlinked, microsatellite short tandem repeat (STR) loci in a single multiplexed polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The assay, which is based on the Applied Biosystems AmpFlSTR Identifiler system, can be performed with only 1 ng of genomic DNA and uses commercially available primers and reagents as well as common instrumentation and analysis software. Thus, it is an attractive alternative to current methods and is readily adaptable to most clinical laboratory environments.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Acquisition

All tissues were provided by the University of New Mexico Solid Tumor Facility, unless otherwise specified. Buccal cells were collected from oral rinses of volunteers. The Cooperative Human Tissue Network (Western Division, Nashville, TN) provided frozen normal and tumor renal tissues obtained by radical nephrectomy, frozen normal breast tissues obtained by reduction mammoplasty, and normal frozen prostate tissues obtained through autopsy. A set of FFPE prostate tumors obtained by radical prostatectomy was provided by the Cooperative Prostate Cancer Tissue Resource (http://www.cpctr.cancer.gov). Duodenal FFPE tumor tissues were obtained from the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). Pancreatic FFPE normal and tumor tissues were obtained from the Department of Pathology at the University of New Mexico. Frozen endometrial tumor tissues were obtained through the Gynecologic Oncology Group (Philadelphia, PA). All specimens lacked patient identifiers and were obtained in accordance with all federal guidelines, as approved by the University of New Mexico Human Research Review Committee.

DNA Isolation and Quantification

DNA was isolated from all tissue samples using the DNeasy silica-based spin column extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and the manufacturer’s suggested animal tissue protocol. FFPE samples were treated with xylene and washed with ethanol before DNA extraction. DNA concentrations were measured using the Picogreen dsDNA quantitation assay (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) using a λ phage DNA as the standard as directed by the manufacturer’s protocol.

Multiplex PCR Amplification of STR Loci

The AmpFlSTR Identifiler kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used to amplify genomic DNA at 16 different STR microsatellite loci (Amelogenin, CSF1PO, D2S1338, D3S1358, D5S818, D7S820, D8S1179, D13S317, D16S539, D18S51, D19S433, D21S11, FGA, TH01, TPOX, and vWA) in a single multiplexed PCR reaction, according to the supplier’s protocol. Linear amplification of allelic PCR products is a prerequisite for ratiometric determination of AI. Therefore, each PCR reaction was limited to 28 cycles, as determined in preliminary studies. The 16 primer sets are designed and labeled with either 6-FAM, PET, VIC, or NED to permit the discrimination of all amplicons in a single electrophoretic separation. The PCR products were resolved by capillary electrophoresis using an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Fluorescent peak heights were quantified using ABI Prism GeneScan analysis software (Applied Biosystems). Allelic ratios were calculated using the peak height, rather than the peak area, as suggested in previous studies.23,24,25 For simplicity, the allele with the greater fluorescence was always made the numerator, as to always generate a ratio ≥1.0.

Statistical Analysis

A Pearson χ2 test was performed using SAS JMP software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) to examine the relationship between the extent of AI and tissue type, using a significance level of 0.05.

Results

The 16 allelic microsatellite loci amplified by the AmpFlSTR Identifiler primer sets are unlinked and can be used to assess AI simultaneously at multiple heterozygous sites throughout the genome. This is technically possible because each amplicon is labeled with one of four fluorescent dyes (6-FAM, PET, VIC, and NED), each with a unique emission profile, thus allowing the resolution of amplicons of similar size. Figure 1 shows the sizes of VIC-labeled amplicons derived from a representative specimen of matched normal and tumor renal tissue (the fluorescent channels showing the PET-, 6-FAM-, and NED-labeled products are not shown). Within Figure 1A, illustrating the results from the normal tissue specimen, two of the allelic pairs are homozygous (D13S317, D16S539), as indicated by a single peak, and three of the allelic pairs are heterozygous (D3S1358, TH01, D2S1338), as indicated by two peaks. Although the peak heights varied between different loci, ostensibly because of different PCR efficiencies, the peak heights of the paired alleles were similar. Theoretically, the ratio of any two heterozygous alleles is 1.0 in normal tissues. However, differences in PCR efficiency between different length alleles and random experimental variation resulting from instruments, reagents, and personnel may affect the observed ratio of heterozygous alleles. To assess these sources of potential variation, the ratios of paired alleles’ signal intensities were compared at 320 heterozygous loci in buccal cells from 27 healthy individuals. Across all loci, the mean ratio was near 1.0 (mean, 1.15; SD, 0.18). We expect that ∼97.5% of all allelic ratios in normal tissues would fall within 2.5 SD of the mean and therefore operationally defined an allelic ratio of >1.60 (mean +2.5 SD) as a site of AI. Applying this threshold to the 27 analyzed buccal samples, only eight sites of AI were detected of the 320 heterozygous loci, thus representing a mean of 0.30 unbalanced loci per sample. Figure 1B illustrates the results of the tumor tissue matched to the normal sample in Figure 1A. Within this sample, two of the three heterozygous loci in the renal tumor tissue amplified by the VIC-labeled primer sets have peak height ratios of >1.60, identifying them as sites of AI.

Figure 1.

Electropherograms of VIC-labeled amplicons from a matched normal and renal carcinoma sample. PCR was performed and the resulting amplicons resolved as described in Materials and Methods. Only VIC-labeled amplicons are shown. In this particular sample, the D3S1358, THO1, and D2S1338 loci are heterozygous, and D13S317 and D16S539 loci are homozygous. Fluorescence intensity is shown on the y axis, and amplicon size, in bp, is shown on the x axis. The ratios of the fluorescent intensities of each allelic pair of heterozygous loci are shown. Loci with allelic ratios of >1.60 are defined as sites of AI for matched normal (A) or tumor (B) tissue.

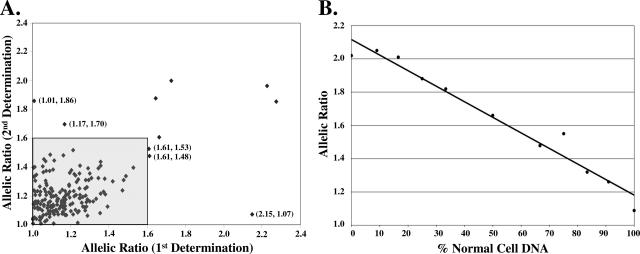

To determine whether AI determinations were reproducible, the assay was repeated within a random subset of the buccal samples. The mean absolute variation of the allelic ratios for the repeated samples was 10% and 193 of the 198 (97.5%) loci measured were correctly categorized on repeating the experiment; however, only five of the 198 (2.5%) loci initially designated as sites of AI could not be confirmed (Figure 2A). Two loci changed from sites without AI (≤1.60) to sites of AI (>1.60), and three loci changed from sites of AI to sites without AI.

Figure 2.

Reproducibility and effect of admixtures of matched normal and renal carcinoma DNA on allelic peak height ratios. A: Allelic peak height ratios were determined for 198 heterozygous loci in 16 normal buccal samples. The plot represents the first determination (x axis) and the second determination (y axis). The region defined by the gray shaded box represents all of the loci that were determined not to be a site of AI on both determinations. The labeled points (allelic peak height ratios for both determinations) represent the five loci that were not correctly identified on repeating the experiment. B: The specified admixtures were generated using DNA from a matched pair of normal renal tissue and renal cell carcinoma as shown in Figure 1. Data from the heterozygous D3S1358 locus are shown. The allelic ratios are 1.09 in the normal renal tissue and 2.02 in the renal carcinoma. The best-fit line was generated by linear regression and has a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.965.

We next confirmed that the differences in AI detected by this approach reflected true differences in the ratio of the alleles, not experimental artifact (eg, differential PCR amplification efficiency). We constructed defined mixtures of DNAs from the paired normal and tumor tissue shown in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 2B for the D3S1358 locus, there was a linear relationship (R2 = 0.965) between the ratio of alleles measured in the assay and the composition of the mixture. Similar results were obtained for each of the other loci exhibiting a site of AI (TH01, R2 = 0.973; VWA, R2 = 0.981; D18S541, R2 = 0.953). In contrast, the composition of the mixture had no effect on the allelic ratios of loci not exhibiting AI (data not shown).

The operationally defined threshold for AI was validated by measuring the allelic ratios for 1382 heterozygous loci in an independent test set comprised of 118 normal samples consisting of bone (n = 2), breast (n = 10), buccal (n = 53), lymph node (n = 5), peripheral blood lymphocytes (n = 18), pancreas (n = 6), placenta (n = 3), prostate (n = 4), renal (n = 16), and tonsil (n = 1) tissues (Figure 3A). In this sample set of normal tissues, only 32 of 1382 heterozygous loci were designated sites of AI, thus representing a mean of 0.27 unbalanced loci per sample, comparable with the 0.30 unbalanced loci per sample in the original normal sample set. In summary, 88 (74.6%), 29 (24.6%), and one (0.8%) of the 118 normal tissues specimens contained zero, one, and two loci with AI, respectively.

Figure 3.

Frequency of AI in normal and tumor tissues. The numbers of sites of AI (ie, 0, 1, ≥2) were determined in 118 samples of normal tissue (A) and in 239 samples of tumor tissue (B). The number of specimens in each tissue set (n) is indicated below the set designation. LN, lymph node; PBL, peripheral blood lymphocytes; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; Endo, endometrial. See Materials and Methods for additional details.

It is well established that cancerous tissues have more sites of AI than normal tissues. To validate our assay in this context, we next measured the frequency of AI in 2792 heterozygous loci in a set of 239 frozen or FFPE tumor samples consisting of acute myelogenous leukemia (n = 8), breast (n = 39), chronic myelogenous leukemia (n = 3), duodenal (n = 23), endometrial (n = 78), pancreas (n = 6), prostate (n = 47), and renal (n = 35) tissues. As shown in Figure 3B, 37 (15.5%), 41 (17.2%), and 161 (67.4%) of the 239 tumor tissues specimens contained zero, one, and more than or equal to two loci with AI, respectively. In contrast to the normal tissues, 611 sites of AI were detected, thus representing a mean of 2.56 unbalanced loci per sample, nearly 10 times greater than the frequency in the normal tissues (P < 0.0001). In summary, 162 of 357 tissue specimens had ≥2 unbalanced loci, of which >99% were cancerous.

Discussion

The frequency of AI reflects the karyotypic complexity of the cancer genome and such manifestations are widespread in solid tumors.1 There have been numerous studies of these abnormalities and several techniques, including chromosome painting, array CGH, and SNP arrays, have emerged to analyze these differences between normal and tumor tissues.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 However, these methods are typically costly, time intensive, and need a matched referent (normal) DNA sample for analysis. For this reason, it is desirable to develop general, economical, high-throughput methods to quantify the extent of AI in the genome of any tissue, independent of the nature and composition of the specimen and the availability of matched, normal tissue.

Using our newly developed assay and interpretation scheme to assess the frequency of AI in human tissues, we have shown in a set of 239 samples that 67% of the tumors contained two or more sites of AI, as compared with 0.8% of the normal samples, which represents an almost 84-fold difference. It must be noted that tissue heterogeneity, such as a preponderance of normal cells within the tumor, may quench peak-height ratios below the 1.60 threshold, thus obscuring AI in a particular sample. In addition, the assay cannot discriminate between homozygous alleles and complete loss of heterozygosity in the absence of matched normal tissue. However, the latter limitation is mitigated by the near ubiquitous presence of normal tissue within tumors, which allows for the assessment of AI in samples without requiring analysis of matched normal tissue. This is an important consideration in the potential evaluation of biopsy tissue, which may contain multiple clones of genetically altered cells superimposed on a background of normal stromal and epithelial cells, and obtaining matched normal tissue may be difficult.

Altered gene expression resulting from genomic instability is a cause of cancer progression; therefore, cancerous tissues have more sites of AI than normal tissues. Consistent with this observation, >99% of tissues with ≥2 sites of AI were cancerous. We are currently investigating the possibility that the number of sites of AI in cancer tissue is a reflection of its stage of progression and therefore may correlate with clinical parameters or prognosis.

Existing alternative methods identify AI as a difference in the allelic ratios in the sample of interest (eg, tumor) relative to the allelic ratios in a patient-matched referent DNA. These methods allow for the distinction between complete loss of heterozygosity and a constitutive homozygous allele and are able to control for PCR efficiency differences of alleles of dissimilar length. In contrast, the present method identifies AI as a deviation from a 1:1 ratio between alleles within the sample of interest only. Thus, the assay described herein can be performed on specimens for which a reliable referent sample is not available. In addition, we have determined that the mean absolute variation of the allelic ratios for all microsatellite loci in our panel is ∼15% in normal tissues. This variation represents the combined effects of 1) random experimental error resulting from instruments, reagents, and personnel; 2) copy number polymorphisms; and 3) inherent differences in the PCR efficiencies of microsatellite alleles of dissimilar lengths. Based on replicate experiments of the same sample (Figure 2A), we have determined that random experimental variation resulting from instruments, reagents, and personnel accounts for ∼10% of the overall variation. Therefore, variation resulting from differences in PCR efficiencies is ∼5%. Although the latter variation is excluded by comparison to a referent DNA, the requirement for two determinations (sample of interest and referent), each with an average variation of at least 10%, minimizes the benefit gained by controlling for PCR efficiency.

In conclusion, we describe here a simple method for assessing the extent of AI throughout the genome. This method has a number of significant advantages over existing technologies, such as chromosome painting, array CGH, and SNP arrays and, as a molecular-based assay, may be used clinically in conjunction with histological techniques. The advantages of this method are that 1) it is robust, reproducible, and provides a quantitative basis for comparing the extent of AI between samples; 2) it does not require matched normal tissue; 3) it utilizes commercially available reagents, instrumentation, and analysis software;, 4) it can be applied to a variety of fresh, frozen, and archival tissues; 5) it requires very little DNA (the equivalent of ∼150 cells); and 6) >99% of tissues with ≥2 sites of AI were cancerous.

Acknowledgments

We thank Terry Mulcahy and Phillip Enriquez III, from the DNA Research Services of the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center for gel capillary analysis; and Dr. Artemis Chakerian from the University of New Mexico Experimental Pathology Laboratory for tissue sectioning.

Footnotes

Supported by the Department of Defense (Breast Cancer Research Program: DAMD17-02-1-0514, W81XWH-05-1-0273, and W81XWH-04-1-0370; Prostate Cancer Research Program: W81XWH-04-1-0831 and W81XWH-06-1-0120) and the National Institutes of Health (grant RR0164880).

References

- Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature. 1998;396:643–649. doi: 10.1038/25292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne SR, Kemp CJ. Tumor suppressor genetics. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:2031–2045. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundle SD, Sokolova I. Clinical implications of advanced molecular cytogenetics in cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2004;4:71–81. doi: 10.1586/14737159.4.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JW, Collins C. Genome changes and gene expression in human solid tumors. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:443–452. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallioniemi A, Kallionemi OP, Sudar D, Rutovitz D, Gray JW, Waldman F, Pinkel D. Comparative genomic hybridization for molecular cytogenic analysis of solid tumors. Science. 1992;258:818–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1359641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas-Toldo S, Lampel S, Stilgenbauer S, Nickolenko J, Benner A, Dohner H, Cremer T, Lichter P. Matrix-based comparative genomic hybridization: biochips to screen for genomic imbalances. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 1997;20:399–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkel D, Segraves R, Sudar D, Clark S, Poole I, Kowbel D, Collins C, Kuo WL, Chen C, Zhai Y, Dairkee SH, Ljung BM, Gray JW, Albertson DG. Quantitative high resolution analysis of DNA copy number variation in breast cancer using comparative genomic hybridization to DNA microarrays. Nat Genet. 1998;20:207–211. doi: 10.1038/2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack JR, Perou CM, Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Pergamenschikov A, Williams CF, Jeffrey SS, Botstein D, Brown PO. Genome-wide analysis of DNA copy-number changes using cDNA microarrays. Nat Genet. 1999;23:41–46. doi: 10.1038/12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders AM, Nowak N, Segraves R, Blackwood S, Brown N, Conroy J, Hamilton G, Hindle AK, Huey B, Kimura K, Law S, Myambo K, Palmer J, Ylstra B, Yue JP, Gray JW, Jain AN, Pinkel D, Albertson DG. Assembly of microarrays for genome-wide measurement of DNA copy number. Nat Genet. 2001;29:263–264. doi: 10.1038/ng754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertson DG. Profiling breast cancer by array CGH. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;78:289–298. doi: 10.1023/a:1023025506386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch A, Ruschendorf F, Huang J, Trautmann U, Becker C, Thiel C, Jones KW, Reis A, Nurnberg P. Molecular karyotyping using an SNP array for genomewide genotyping. J Med Genet. 2004;41:916–922. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.022855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Li C, Paez JG, Chin K, Janne PA, Chen TH, Girard L, Minna J, Christiani D, Leo C, Gray JW, Sellers WR, Meyerson M. An integrated view of copy number and allelic alterations in the cancer genome using single nucleotide polymorphism arrays. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3060–3071. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan JB, Oliphant A, Shen R, Kermani BG, Garcia F, Gunderson KL, Hansen M, Steemers F, Butler SL, Deloukas P, Galver L, Hunt S, McBride C, Bibikova M, Rubano T, Chen J, Wickham E, Doucet D, Chang W, Campbell D, Zhang B, Kruglyak S, Bentley D, Haas J, Rigault P, Zhou L, Stuelpnagel J, Chee MS. Highly parallel SNP genotyping. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2003;68:69–78. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2003.68.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth RE, Ellsworth DL, Lubert SM, Hooke J, Somiari RI, Shriver CD. High-throughput loss of heterozygosity mapping in 26 commonly deleted regions in breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;129:915–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth DL, Ellsworth RE, Love B, Deyarmin B, Lubert SM, Mittal V, Hooke JA, Shriver CD. Outer breast quadrants demonstrate increased levels of genomic instability. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:861–868. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth RE, Ellsworth DL, Deyarmin B, Hoffman LR, Love B, Hooke JA, Shriver CD. Timing of critical genetic changes in human breast disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:1054–1060. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.03.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Mok SC, Chen Z, Li Y, Wong DT. Concurrent analysis of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and copy number abnormality (CNA) for oral premalignancy progression using the Affymetrix 10K SNP mapping array. Hum Genet. 2004;115:327–330. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaburn E, Butcher LM, Schalkwyk LC, Plomin R. Genotyping pooled DNA using 100K SNP microarrays: a step towards genomewide association scans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e27. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SS, Oliphant A, Shen R, McBride C, Steeke RJ, Shannon SG, Rubano T, Kermani BG, Fan JB, Chee MS, Hansen MS. A highly informative SNP linkage panel for human genetic studies. Nat Methods. 2004;1:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nmeth712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips EH, Dierssen JW, van Eijk R, Oosting J, Eilers PH, Tollenaar RA, de Graaf EJ, van’t Slot R, Wijmenga C, Morreau H, van Wezel T. Reliable high-throughput genotyping and loss-of-heterozygosity detection in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumors using single nucleotide polymorphism arrays. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10188–10191. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JJ, Wilson IM, Lam WL. Array CGH technologies and their applications to cancer genomes. Chromosome Res. 2005;13:237–248. doi: 10.1007/s10577-005-2168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson TG, Galipeau PC, Reid BJ. Loss of heterozygosity analysis using whole genome amplification, cell sorting, and fluorescence-based PCR. Genome Res. 1999;9:482–491. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medintz IL, Lee CC, Wong WW, Pirkola K, Sidransky D, Mathies RA. Loss of heterozygosity assay for molecular detection of cancer using energy-transfer primers and capillary array electrophoresis. Genome Res. 2000;10:1211–1218. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.8.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skotheim RI, Diep CB, Kraggerud SM, Jakobsen KS, Lothe RA. Evaluation of loss of heterozygosity/allelic imbalance scoring in tumor DNA. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001;127:64–70. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(00)00433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]