Abstract

Mastocytosis represents a clonal proliferation of mast cell hematopoietic progenitors caused by gain-of-function mutations of the c-kit gene. The heterogeneity of c-kit mutations may have contributed to difficulties in characterizing genotype-phenotype correlation of the disease. Our goal was to analyze a set of reported pathogenic c-kit mutations in patients with childhood-onset cutaneous mastocytosis, in comparison with those with adult-onset disease, and to correlate these with clinical presentation. We performed polymerase chain reaction and direct sequencing using genomic DNA samples from 16 nonfamilial Japanese patients with indolent cutaneous mastocytosis (12 with childhood-onset disease and 4 with adult-onset disease) to look for the most common c-kit mutations at codons 816, 560, 820, and 839. A substantial number of patients had missense codon 816 mutations (10 of 12 in the childhood-onset group, 83.3%; and 4 of 4 in the adult-onset group, 100%). The most common mutation was Asp816Val (9 of 16, 64.3%) followed by Asp816Phe (5 of 16, 35.7%). Moreover, children with the Asp816Phe mutation developed cutaneous mastocytosis at an earlier age as compared to those with the Asp816Val mutation (mean age of onset, 1.3 months versus 5.9 months, respectively; P = 0.068). No other mutation variations were found in our cohort. In summary, we confirmed a high incidence of two distinct c-kit mutations, Asp816Val and Asp816Phe, in patients with childhood-onset cutaneous mastocytosis. Our results provide new insights into common c-kit mutations, which may contribute to different clinical courses of the disease.

Mastocytosis (OMIM 154800) is a diverse group of skin and hematological disorders characterized by hyperproliferative condition of mast cells in various organs, including skin, bone marrow, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes.1 Onset of disease is usually in infancy or early adulthood. Although most cases of childhood-onset disease resolve spontaneously by puberty,2 adult-onset disease can be intractable and may be compounded by systemic symptoms, resulting in mortality. Mastocytosis can be classified into four clinical subgroups: cutaneous disease (IA) or systemic involvement (IB), disease associated with hematological abnormalities (II), with aggressive mastocytosis (III), and with aggressive carcinomas (IV). IA and IB are the most common phenotypes. The clinical manifestations and prognosis of mastocytosis are difficult to predict and varies considerably between affected individuals.

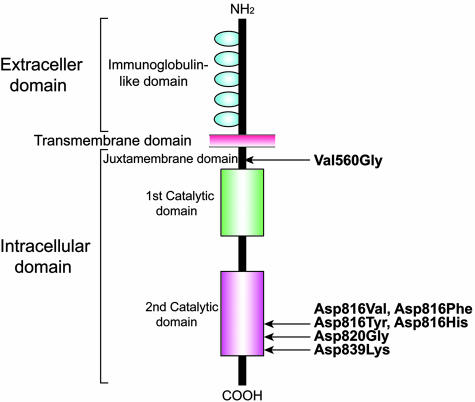

Molecular-based evidence has shown that this condition results from particular mutations in the proto-oncogene c-kit (Figure 1). The gene encodes a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor, Kit, that is activated by the binding of specific ligands, such as mast cell growth factor or stem cell factor.3 Kit is expressed on several cell types and is known to activate cell growth and maturation via a phosphorylation-dependent pathway involving tyrosine kinase.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of Kit protein and location of c-kit gene mutations described previously. The distinct molecular domains comprise three functional structures: NH2-terminal extracellular, transmembrane and COOH-terminal intracellular domains. The extracellular domain contains five immunoglobulin-like repeats and the intracellular domain encodes two tandem repeats of the enzyme catalytic domains. The mutations at codon 560 within the juxtamembrane region and codon 816/820 within the second catalytic domain cause ligand-independent autophosphorylation of Kit receptor protein, whereas the mutation at codon 839 results in loss of receptor function.8 The c-kit mutations reported thus far are shown.

A previous study has shown that there are two major missense changes in the c-kit gene at codons 816 and 560, both of which were first identified in the human mast cell line HMC-1.4 The former mutation mostly substitutes an aspartate for a valine residue (Asp816Val) in a majority of patients with adult-onset disease, whereas the latter mutation substituting a valine for a glycine residue (Val560Gly) can rarely be detected.5 These two missense mutations are also unusual in patients with childhood-onset mastocytosis. Thus, the relationship between the underlining pathogenesis and diverse clinical presentations in mastocytosis may be explained in part by the heterogeneity of c-kit mutations.5,6,7 Notably there are no characteristic c-kit mutations in patients with childhood-onset mastocytosis.

Recent investigations have disclosed that both Asp816Val and Val560Gly mutations can elicit constitutive activation of the relevant intracellular Kit signaling, resulting in a clonal proliferation of the affected mast cells.8 In addition, other pathogenic mutations, Asp816Phe, Asp816Tyr,8 Asp816His,9 and Asp820Gly,10 have been shown to induce aberrant autophosphorylation of Kit. However, there is limited information available to understand the functional significance of two c-kit mutations: Phe522Cys within the transmembrane portion11 and the dominant inactive mutation Glu839Lys.8 Despite peripheral blood and bone marrow integration, these c-kit mutations are now considered to be of somatic cell origin.8,12 The exact contribution of c-kit mutations to the clinical course of mastocytosis remains unclear. In this study, we attempt to characterize the c-kit mutation profiles in patients with childhood-onset indolent mastocytosis, and extend genotype-phenotype correlation.

Materials and Methods

Patients

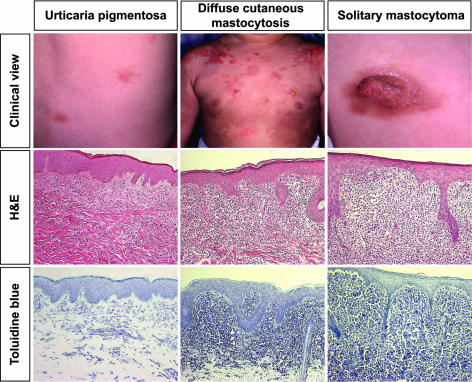

We assessed 16 nonfamilial Japanese patients with cutaneous mastocytosis (Table 1). The cohort included four adults with sporadic disease (one male and three females; mean age of onset, 29 years), nine children with urticaria pigmentosa (eight males and one female; mean age of onset, 5.7 months), two children with solitary mastocytoma (two males; mean age of onset, 0.5 month), and one boy with diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (disease onset at 6 months). The former sporadic group comprised three patients with urticaria pigmentosa and one with diffuse mastocytoma. The details are summarized in Table 1. In all patients the diagnosis was confirmed clinically and histologically (hematoxylin and eosin and toluidine blue staining) (Figure 2). After informed consent, biopsy samples were taken from the lesional skin, cut into small pieces, and stored separately for snap-frozen or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patient | Sex | Age of onset | Clinical diagnosis | Mutation type (codon 816) | Mean dermal mast cell density in lesional skin (number per 500 μm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 1 year | Urticaria pigmentosa | Val | 102 |

| 2 | F | 3 months | Urticaria pigmentosa | Val | 284 |

| 3 | M | 7 months | Urticaria pigmentosa | Val | 204 |

| 4 | M | 3 months | Urticaria pigmentosa | Phe | 145 |

| 5 | M | 1 month | Urticaria pigmentosa | Phe | 550 |

| 6 | M | 5 months | Urticaria pigmentosa | Val | 66 |

| 7 | M | 7 months | Urticaria pigmentosa | Val | 148 |

| 8 | M | 6 months | Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis | Val | 544 |

| 9 | M | Present at birth | Solitary mastocytoma | Phe | 672 |

| 10 | M | 1 month | Solitary mastocytoma | Val | 71 |

| 11 | M | 1 year | Urticaria pigmentosa | None | 350 |

| 12 | M | 1 month | Urticaria pigmentosa | None | 406 |

| 13 | F | 59 years | Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis | Val | 77 |

| 14 | F | 28 years | Urticaria pigmentosa | Val | 70 |

| 15 | M | 16 years | Urticaria pigmentosa | Phe | 74 |

| 16 | F | 13 years | Urticaria pigmentosa | Phe | 47 |

Figure 2.

Clinical and histological findings. Our mastocytosis cohort includes three different clinical subgroups: urticaria pigmentosa (case 12, left column), diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (case 8, middle column), and solitary mastocytoma (case 9, right column). Histology shows marked and dense dermal infiltration of mast cells, although urticaria pigmentosa skin exhibits patchy infiltration in the upper dermis (H&E and toluidine blue staining). Representative clinicopathological features are shown.

Histomorphometric Analysis

Density of mast cells in each skin sample was assessed by toluidine blue.5 The number of the mast cells was examined at ×400 magnification (Zeiss, Wetzlar, Germany) and was expressed as the mean cell count per 500 μm2 from three different grids (Table 1).

DNA Samples

Genomic DNA was extracted from either fresh frozen or formalin-fixed skin sections by a standard proteinase K digestion and subsequent phenol/chloroform extraction method.13 The DNA samples were obtained just before the mutation detection procedure.

Mutation Screening

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for DNA amplification. Based on the previously published data,14 the primers used were designed specifically for exons 11, 17, and 18 of the c-kit gene (Table 2). The amplification conditions were 94°C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing temperature (Table 2) for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds with a final extension for 10 minutes at 72°C. The reaction mixture contains 0.5 ng of individual genomic DNA as a template, 20 pmol of the primers, 2.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L dNTPs, and 1 U of Taq polymerase (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Aliquots (5 μl) were purified with a Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and then sequenced directly with an automated DNA sequencer CEQ2000XL (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) using both the sense and anti-sense primers. To avoid the possibility of introducing PCR errors, both sense and anti-sense readings were repeated at least twice. As a control, archival DNA samples were randomly chosen from unrelated normal patients, and sequenced using the same procedure.

Table 2.

Primer Sequences for DNA Amplification

| Primer name | Sequence* | Position | Detection site (amino acid) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codon 816/820-F | 5′-TGTATTCACAGAGACTTGGC-3′ | Exon 17 | Codons 816 and 820 | 58 | 217 |

| Codon 816/820-R | 5′-GGATTTACATTATGAAAGTCAC-3′ | Exon 17 | |||

| Codon 560-F | 5′-TCTCTCCAGAGTGCTCTAATGA-3′ | Exon 11 | Codon 560 | 62 | 155 |

| Codon 560-R | 5′-GGAAGTTGTGTTGGGTCTATGTA-3′ | Exon 11 | |||

| Codon 839-F | 5′-TTCTATTACAGGCTCGACTACCT-3′ | Exon 18 | Codon 839 | 60 | 188 |

| Codon 839-R | 5′-GACACCAATGAAACTTCAAGATGC-3′ | Exon 18 |

Sequence of the primers was designed according to the previous report (GenBank accession number L04143).

Statistics

Data were analyzed by Student’s unpaired t-test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Identification of Two Common Missense Mutations in c-kit

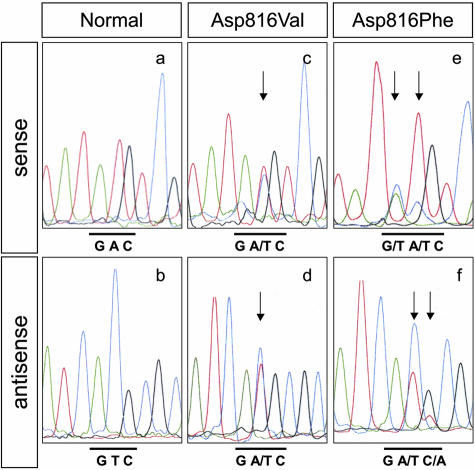

Assessment by histomorphometry analysis using toluidine blue staining showed that the mast cell density in the lesional skin varied considerably among disease phenotypes (Table 1). However, the minimal cell density (case 16) was sufficient for detecting the mutated c-kit allele, thus suggesting adequate amounts of targeting mast cells for the following mutation experiment. For DNA analysis, we designed a new set of PCR primers targeting four independent hot spot c-kit mutations reported elsewhere (Table 2). Direct sequencing of amplified DNA from the lesional skin samples identified just two distinct mutations located at the same site in exon 17 (Figure 1); an A>T substitution at nucleotide 2468 that changes an aspartate residue (GAC) to valine (GTC), Asp816Val, and a doublet transition GA>TT at nucleotides 2467 and 2468 that converts an aspartate residue (GAC) to phenylalanine (TTC), Asp816Phe. Both mutations were heterozygous. None of these patients had other variations of c-kit mutations, such as Asp820Gly, Val560Gly, and Glu839Lys. To avoid the possibility of nonpathogenic polymorphisms, it was established that the two codon 816 alterations were absent in 50 ethnically matched control DNA from the Japanese population. As previous reports revealed,8,15 we reconfirmed that this was certainly a mutation.

Delineation of Pathogenic c-kit Mutations in Childhood-Onset Mastocytosis

As listed in Table 1, DNA analysis of individual patients disclosed a high incidence of either of two c-kit mutations, Asp816Val or Asp816Phe (14 of 16, 87.5%). Of the 12 patients with urticaria pigmentosa, 6 (50%) carried the Asp816Val mutation, 4 (33.3%) the Asp816Phe mutation, and 2 (16.7%) had no hot spot mutations in the c-kit gene. One of the two patients with solitary mastocytoma carried the mutation Asp816Val whereas the other carried the mutation Asp816Phe. In contrast, both patients with diffuse cutaneous disease carried Asp816Val. Apart from diffuse disease, there was no significant correlation between particular c-kit mutations and phenotypes of mastocytosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Identification of the c-kit gene mutation within exon 17. By using genomic DNA from lesional skin, the exon 17 fragment was amplified and sequenced using both sense and anti-sense primers. Representative results from cases 8 and 9 are shown. Sequences of the mutated allele revealed either a substitution from aspartate to valine, Asp816Val (c and d), or from aspartate to phenylalanine, Asp816Phe (e and f), but the normal allele did not (a and b). Arrows indicate the nucleotide substitutions.

We further assessed the disease onset on the basis of the two distinct c-kit missense mutations, Asp816Val and Asp816Phe. Among 12 patients with childhood-onset disease, 10 (83.3%) exhibited a codon 816 mutation. Of these patients, seven (70%) had the mutation Asp816Val and three (30%) carried the mutation Asp816Phe. More importantly, the presence of the Asp816Phe mutation correlated with earlier disease onset. Patients with the Asp816Phe mutation developed mastocytosis at a younger age compared to those with the Asp816Val mutation (mean age of onset, 1.3 ± 1.5 months versus 5.9 ± 3.5 months, respectively). However, there was no statistically significant difference between these two groups (P = 0.068). In contrast, all four patients with adult-onset disease had codon 816 mutations, two with the mutation Asp816Val and two others with the mutation Asp816Phe (50% in each codon 816 mutation).

Discussion

In this study, we have characterized the common pathogenic c-kit mutations in Japanese patients with childhood-onset cutaneous mastocytosis. By using genomic DNA from the lesional skin sites, mutation screening of 16 nonfamilial patients revealed that irrespective of disease phenotype most mastocytosis patients have either Asp816Val or Asp816Phe missense mutations (14 of 16, 87.5%). More importantly, the codon 816 mutations were detectable in most patients with childhood-onset disease (10 of 12, 83.3%). In addition, the mutation Asp816Val, as opposed to Asp816Phe, was predominant among these patients (7 of 10, 70%). In contrast, patients with the Asp816Phe mutation tend to develop cutaneous mastocytosis at earlier age. These findings suggest the pathogenic relevance of the Asp816Phe c-kit mutation in the early onset mastocytosis. Likewise, a series of molecular studies may provide a genetic overview of characteristic c-kit mutations in cutaneous mastocytosis, as well as the prognostic implications by detection of particular mutations. Nevertheless, we did not identify any c-kit mutation variants other than codon 816 in our cohort. Taking into account accumulated data thus far, our results suggest strategies for mutation detection. We propose an initial screening of codon 816 and then the remainder of common c-kit mutations in any new patient with childhood-onset cutaneous mastocytosis (particularly in patients 11 and 12 without any hot spot mutations; Table 1). Although our control study includes relatively small number of patients (n = 50), they never had polymorphism sequences at codons 816, 820, 560, and 839 in the c-kit gene. Furthermore, a series of large cohort studies have demonstrated that these four sites within the c-kit gene do not account for polymorphisms.8,15,16,17 Considering these, the possibility for polymorphism at these particular sites can be at least excluded.

Additionally, all patients with diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis carried the Asp816Val mutation (2 of 2, 100%), although there was no statistically significant association between the codon 816 mutations and individual phenotypes. This is in agreement with previous reports showing difficulties in genotype-phenotype correlation, particularly in the heterogeneous observations between human mastocytosis and experimental mice models. A number of reports have demonstrated germline mutations within exon 11 of c-kit in mastocytosis with multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors.16,18 In contrast, Sommer and colleague19 have failed to reproduce any of clinical phenotypes of cutaneous mastocytosis by introducing the same c-kit heterozygous mutation (Val558X) into mice. Further experimental mouse studies may need to be performed to elucidate the relationship between particular c-kit mutations and disease phenotypes in mastocytosis.

It should be noted that in our study a relatively higher percentage of patients with childhood-onset mastocytosis carried the Asp816Phe mutation as compared to a previous report.8 One possible explanation for this discrepancy is the different procedures used in DNA analysis, ie, direct sequencing, cDNA subcloning and colony sequencing, or restriction enzyme digestion of the amplified PCR products. A more likely reason would be differences in the sample templates or cell sources, such as bulk genomic DNA or c-kit cDNA synthesized from lesional skin biopsies, bone marrow aspirates, oral epithelial cells, and peripheral blood cells.7,8,17 Furthermore, because c-kit mutations in cutaneous mastocytosis are normally a heterozygous state, the detection sensitivity of the particular mutations may depend on the substantial number of local mast cells with the mutated alleles and the amplification rate of the mutated alleles during the initial nonspecific amplification step in PCR. In our study, however, all four adult patients had the codon 816 mutation and specifically, children with the Asp816Phe mutation developed cutaneous mastocytosis at earlier onset than those with the Asp816Val mutation. Therefore, it is conceivable that the codon 816 mutation is not directly related to the particular clinical subtype but perhaps is responsible for earlier onset mastocytosis (particularly less than 1 year) or the prognosis (indolent and transient clinical course).

Although the precise pathogenic relevance of the missense mutation in Kit receptor protein functions are unknown, a number of studies have demonstrated that constitutive autophosphorylation of the Kit signaling pathway by c-kit mutations contributes to clonal proliferation of the affected mast cells. This evidence may strengthen the argument for the value of new therapeutic targets relevant to the particular c-kit mutations. A potential inhibitor for the Kit signaling, STI-571, prevents the phosphorylation cascade induced by gene mutations within the juxtamembrane domains, such as the Val560Gly mutation, but did not efficiently block the effects of mutations within the enzymatic domains such as the Asp816Val mutation.20,21 However, it has been reported that the SIT-571 partially inhibits aberrant phosphorylation caused by other mutations, such as Asp816Phe and Asp816Tyr.20 Given these therapeutic advances, accurate mutation detection may be valuable for evaluating the treatment efficacies and management of patients with mastocytosis.

In this study, we have elucidated the molecular basis of cutaneous mastocytosis in 16 nonfamilial Japanese patients. Our data are the first documentation providing the significance of codon 816 c-kit mutations in childhood-onset cutaneous mastocytosis, particularly with indolent and transient clinical course. These findings highlight the fundamental importance of the mutation detection strategy to expand the mutation spectrum in the c-kit gene in childhood-onset disease. From the clinical perspective, further investigations regarding a large cohort multicenter study for the identification of pathogenic gene mutations and a longitudinal observation of well-characterized patients are now needed to understand as a yet unidentified disease mechanism in mastocytosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tomoko Inoue (Master of Agriculture, Department of Dermatology, Fukushima Medical University Graduate School of Medicine) for her helpful laboratory work in this study.

Footnotes

Supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan (grants NO 16790651, KN 14570817, and KN 16591107).

References

- Metcalfe DD. Classification and diagnosis of mastocytosis: current status. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:2S–4S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azana JM, Torrelo A, Mediero IG, Zambrano A. Urticaria pigmentosa: a review of 67 pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:102–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1994.tb00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor ML, Metcalfe DD. Kit signal transduction. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14:517–535. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furitsu T, Tsujimura T, Tono T, Ikeda H, Kitayama H, Koshimizu U, Sugahara H, Butterfield JH, Ashman LK, Kanayama Y, Matsuzawa Y, Kitamura Y, Kanakura Y. Identification of mutations in the coding sequence of the proto-oncogene c-kit in a human mast cell leukemia cell line causing ligand-independent activation of c-kit product. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1736–1744. doi: 10.1172/JCI116761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner C, Henz BM, Welker P, Sepp NT, Grabbe J. Identification of activating c-kit mutations in adult-, but not in childhood-onset indolent mastocytosis: a possible explanation for divergent clinical behavior. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:1227–1231. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longley BJ, Metcalfe DD. A proposed classification of mastocytosis incorporating molecular genetics. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14:697–701. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worobec AS, Semere T, Nagata H, Metcalfe DD. Clinical correlates of the presence of the Asp816Val c-kit mutation in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with mastocytosis. Cancer. 1998;83:2120–2129. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981115)83:10<2120::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longley BJ, Jr, Metcalfe DD, Tharp M, Wang X, Tyrrell L, Lu SZ, Heitjan D, Ma Y. Activating and dominant inactivating c-KIT catalytic domain mutations in distinct clinical forms of human mastocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1609–1614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullarkat VA, Pullarkat ST, Calverley DC, Brynes RK. Mast cell disease associated with acute myeloid leukemia: detection of a new c-kit mutation Asp816His. Am J Hematol. 2000;65:307–309. doi: 10.1002/1096-8652(200012)65:4<307::aid-ajh10>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignon JM, Giraudier S, Duquesnoy P, Jouault H, Imbert M, Vainchenker W, Vernant JP, Tulliez M. A new c-kit mutation in a case of aggressive mast cell disease. Br J Haematol. 1997;96:374–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.d01-2042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akin C, Fumo G, Yavuz AS, Lipsky PE, Neckers L, Metcalfe DD. A novel form of mastocytosis associated with a transmembrane c-kit mutation and response to imatinib. Blood. 2004;103:3222–3225. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vliagoftis H, Worobec AS, Metcalfe DD. The protooncogene c-kit and c-kit ligand in human disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:435–440. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LG, Dibner MD, Batte JF. New York: Elsevier,; Basic Methods in Molecular Biology. 1986:44–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmer K, Corless CL, Fletcher JA, McGreevey L, Haley A, Griffith D, Cummings OW, Wait C, Town A, Heinrich MC. KIT mutations are common in testicular seminomas. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:305–313. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63120-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longley BJ, Tyrrell L, Lu SZ, Ma YS, Langley K, Ding TG, Duffy T, Jacobs P, Tang LH, Modlin I. Somatic c-KIT activating mutation in urticaria pigmentosa and aggressive mastocytosis: establishment of clonality in a human mast cell neoplasm. Nat Genet. 1996;12:312–314. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, Hirota S, Taniguchi M, Hashimoto K, Isozaki K, Nakamura H, Kanakura Y, Tanaka T, Takabayashi A, Matsuda H, Kitamura Y. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumours with germline mutation of the KIT gene. Nat Genet. 1998;19:323–324. doi: 10.1038/1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata H, Okada T, Worobec AS, Semere T, Metcalfe DD. c-kit mutation in a population of patients with mastocytosis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1997;113:184–186. doi: 10.1159/000237541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beghini A, Tibiletti MG, Roversi G, Chiaravalli AM, Serio G, Capella C, Larizza L. Germline mutation in the juxtamembrane domain of the kit gene in a family with gastrointestinal stromal tumors and urticaria pigmentosa. Cancer. 2001;92:657–662. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010801)92:3<657::aid-cncr1367>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer G, Agosti V, Ehlers I, Rossi F, Corbacioglu S, Farkas J, Moore M, Manova K, Antonescu CR, Besmer P. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in a mouse model by targeted mutation of the Kit receptor tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6706–6711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037763100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Zeng S, Metcalfe DD, Akin C, Dimitrijevic S, Butterfield JH, McMahon G, Longley BJ. The c-KIT mutation causing human mastocytosis is resistant to STI571 and other KIT kinase inhibitors; kinases with enzymatic site mutations show different inhibitor sensitivity profiles than wild-type kinases and those with regulatory-type mutations. Blood. 2002;99:1741–1744. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zermati Y, De Sepulveda P, Feger F, Letard S, Kersual J, Casteran N, Gorochov G, Dy M, Ribadeau Dumas A, Dorgham K, Parizot C, Bieche Y, Vidaud M, Lortholary O, Arock M, Hermine O, Dubreuil P. Effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 on the kinase activity of wild-type and various mutated c-kit receptors found in mast cell neoplasms. Oncogene. 2003;22:660–664. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]