Abstract

Summary Background Data:

Some previous studies demonstrated better survival after transplantation for small hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) compared with resection, but the influence of differences in tumor invasiveness between transplanted and resected patients has not been studied. This study compared the tumor characteristics of patients with HCC within the Milan criteria treated by resection or transplantation, and elucidated their impact on long-term survival.

Patients and Methods:

Tumor characteristics and long-term survival of 204 cirrhotic patients with resection and 43 cirrhotic patients with transplantation for HCC within the Milan criteria were compared. A multivariate analysis was performed to determine the prognostic factors of survival in all patients with resection or transplantation.

Results:

Tumors in the transplanted group were associated with lower incidence of high-grade tumors, microscopic venous invasion, and microsatellite nodules. The overall 5-year survival was better in the transplantation group than the resection group (81% vs. 68%, P = 0.017). However, there were no significant differences in survival between the two groups when stratified according to presence or absence of venous invasion. Multivariate analysis showed that hepatitis C virus serology, tumor size, tumor number, and microscopic venous invasion, but not resection or transplantation, were of prognostic significance.

Conclusions:

There were significant differences in tumor invasiveness in HCC treated by transplantation and resection as a result of selection bias, even in patients with the tumors fulfilling the Milan criteria. When the different tumor invasiveness was taken into account, there was no significant difference in the long-term survival after resection or transplantation.

This study compared the tumor pathologic features and long-term survival of cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) fulfilling the Milan criteria treated by resection or transplantation. The transplantation group appeared to have better survival than the resection group, but the survival of the two groups was similar when corrected for the higher frequency of microscopic venous invasion in the latter group. This study demonstrated the effect of a difference in tumor invasiveness on long-term survival of patients treated by resection or transplantation for apparently similar HCC according to the Milan criteria, highlighting the need to take into account such a difference when comparing survival after resection or transplantation for HCC.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the 5 most common malignancies in the world, and it is associated with cirrhosis related to hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infection in the majority of cases.1 Partial liver resection and liver transplantation are the potentially curative treatments for HCC.2,3 For patients with compensated (Child-Pugh class A) cirrhosis, liver resection used to be the mainstay of treatment. For early HCC associated with severe cirrhosis (Child-Pugh classes B and C), liver transplantation is universally accepted to be the best treatment.3–6 The most well-established criteria for transplantation for HCC are the Milan criteria: solitary tumor ≤5 cm in diameter or 2 or 3 tumor nodules with the largest diameter ≤3 cm, and absence of macroscopic vascular invasion or extrahepatic metastasis.7 Studies have shown that favorable long-term prognosis with 5-year survival of 60% to 80% can be achieved with liver transplantation for patients with HCC fulfilling the Milan criteria.3,8–10 Whether expanded criteria are justified is a controversial issue,10,11 and the Milan criteria remain the most widely used criteria in transplant centers around the world.5,10,12

In recent years, some authors advocated liver transplantation as a first-choice treatment of HCC within the Milan criteria even for patients with compensated cirrhosis and preserved liver function, leading to an intense debate on whether hepatic resection or liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for such patients.13–15 Several studies have reported a 5-year survival rate of 70% to 75% after resection of small transplantable HCC in cirrhotic patients with preserved liver function,16–19 which appeared to be comparable to the 5-year survival reported in transplantation series. Hence, many authors suggested that liver resection should remain the mainstay of treatment of small HCC in cirrhotic patients with well-preserved liver function.3,6,14,20 In the literature, comparison of survival data was often based on resection and transplantation series reported in different studies. Several studies have directly compared the results of transplantation and resection for HCC.13,18,21–29 Some of these studies demonstrated that transplantation achieved better survival,21,28,29 while others reported similar survival between resected and transplanted patients.24,26,27 With few exceptions,18,26,29 these studies included patients beyond the Milan criteria and the two groups of patients were not similar in tumor criteria, making interpretation of the results difficult.

Even when comparing patients with apparently similar tumors according to the Milan criteria, there is a possible bias due to natural selection of biologically favorable tumors in patients who undergo transplantation, as patients with aggressive tumors may drop out of the waiting list as a result of tumor progression.18 There is no such a selection in those who undergo resection. The potential implication of such a difference in tumor biology has not been addressed in previous studies. Hence, we performed a study to evaluate the differences in tumor invasiveness between a group of resected cirrhotic patients and a group of transplanted patients, both with HCC fulfilling the Milan criteria, and to elucidate the influence of such a difference on long-term survival after resection and transplantation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between January 1995 and December 2004, 204 cirrhotic patients with HCC within the Milan criteria underwent hepatic resection, and another 43 cirrhotic patients with HCC within the Milan criteria underwent primary liver transplantation at the Department of Surgery, University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong, China. These patients had HCC within the Milan criteria as confirmed by pathologic examination of the specimens. Patients with incidental finding of HCC in the explants were excluded from this study.

In our unit, liver resection is considered the first line therapy for patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis, and for selected patients with Child-Pugh class B cirrhosis in whom the tumor(s) could be removed by minor resection of 2 segments or fewer.2 The techniques of liver resection and perioperative management in our unit have been described in detail elsewhere.2,30 Liver transplantation is generally reserved for patients with Child-Pugh class B or C cirrhosis whose liver function reserve was not adequate for liver resection, although in some patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis, liver transplantation was offered when the number and site of the tumors precluded safe hepatic resection. In general, only patients younger than 65 years were considered for transplantation, although this was not a strict criterion and the physiologic status of the patients was taken into consideration. Of the 43 patients who underwent liver transplantation, 13 patients (30.2%) received deceased donor liver transplantation and the other 30 patients (69.8%) received live donor liver transplantation using right lobe grafts. Because of the relative shortage of deceased donor liver grafts and the prevalence of HCC in Hong Kong, there was no prioritization of deceased donor liver grafts for patients with HCC in our unit. Details of our preoperative evaluation of live donors and HCC recipients, the techniques of right lobe live donor liver transplantation, and perioperative management including immunosuppressive and antiviral therapies have been described elsewhere.31,32

Data on preoperative host and tumor characteristics, perioperative outcomes, pathologic data, and long-term survival of all patients were prospectively collected in a research database. Presence or absence of microscopic venous invasion was determined based on histologic examination of serial sections of the resected specimens. Histologic tumor differentiation was determined using the Edmonson-Steiner grading.33 Eight patients with deceased donor liver transplantation received transarterial chemoembolization before transplantation as a bridge therapy. Patients with resectable HCC were offered resection immediately after diagnostic workup without any preoperative therapy, except for 2 patients who received transarterial chemoembolization before referral to our center. All patients were regularly followed in the outpatient clinic by the surgical team, with regular surveillance for recurrence by serial alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and helical contrast computed tomography (CT) every 3 months. Intrahepatic tumor recurrences were managed with reresection, transarterial chemoembolization, or radiofrequency ablation according to the tumor status and liver function at the time of recurrence. Follow-up data were complete in all patients, with a median follow-up of 53 months (range, 8–124 months) in the liver resection group and 49 months (range, 8–123 months) in the liver transplantation group by August 31, 2005.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of the tumor characteristics, perioperative and long-term outcomes of the two groups of cirrhotic patients with HCC fulfilling the Milan criteria treated by liver resection and liver transplantation, respectively, were performed based on the prospectively collected data. Comparison of categorical variables was performed using the χ2 test with Yates' correction (or Fisher exact test where appropriate). Continuous variables were expressed as median (range) and compared between groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. Long-term overall and tumor recurrence-free survivals were computed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Hospital mortality, defined as any death within the same hospital admission for the treatment, was included in the overall survival analysis but excluded from the recurrence-free survival analysis. Overall survival was considered the primary treatment outcome for analysis. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of overall survival was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. An intention-to-treat comparison of the overall survival of all patients who had HCC fulfilling the Milan criteria according to preoperative imagings and were listed for resection or liver transplantation during the same period was also performed. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Demographic Data and Tumor Characteristics

Table 1 shows the comparison of baseline demographic data and tumor characteristics of patients with liver resection and those with liver transplantation. Patients in the resection group were significantly older than those in the transplantation group (P = 0.022). The majority of HCCs in both groups were related to hepatitis B virus infection. Most patients in the resection group had Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis, whereas the majority in the transplantation group had Child-Pugh class B or C cirrhosis. A higher proportion of patients in the resection group presented with symptoms (P = 0.033), most commonly pain, whereas in the transplantation group most patients had tumors detected by ultrasound or elevated AFP during regular surveillance. Serum AFP was significantly higher in the resection group (P = 0.037), and tumor size was also significantly larger in the resection group than those in the transplantation group when compared either as a continuous variable (median, 3.0 cm vs. 2.5 cm, P = 0.011) or as a binary variable of ≤3 cm versus >3 cm (P = 0.009). However, the transplantation group had a higher proportion of oligonodular (2 or 3) tumors than the resection group (P = 0.002). All HCCs in the transplantation group were well differentiated or moderately differentiated, whereas 32 patients (15.7%) in the resection group had poorly differentiated HCC. The rate of microscopic venous invasion was significantly higher in the resection group (29.9% vs. 13.9%, P = 0.033). Even when stratified by tumor size, the rate of microscopic venous invasion was higher in the resection group than the transplantation group for both tumors ≤3 cm (25.4% vs. 14.7%) and tumors >3 cm (36.0% vs. 11.1%). Patients in the resection group also had a higher incidence of microscopic satellite nodules (P = 0.047).

TABLE 1. Demographic Data and Tumor Characteristics

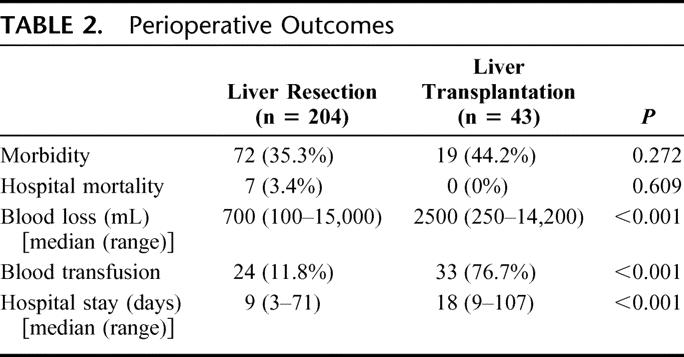

Perioperative Outcomes

Table 2 shows the perioperative outcomes of the two groups. There were no significant differences in hospital mortality and morbidity, but the transplantation group had significantly more operative blood loss, higher transfusion rate, and longer hospital stay.

TABLE 2. Perioperative Outcomes

Long-term Survival

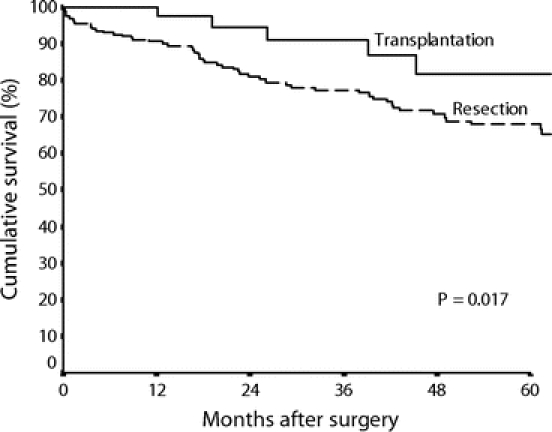

Figure 1 shows the cumulative overall survival curves of the two groups of patients. Patients in the transplantation group had significantly better survival compared with those in the resection group (5-year survival 81% vs. 68%, P = 0.017). However, when stratified by the presence or absence of microscopic vascular invasion, there was no significant difference between the transplantation and resection groups in the overall survival among those without microscopic vascular invasion (5-year survival 82% vs. 77%, P = 0.125, Fig. 2), or those with microscopic vascular invasion (P = 0.342). Within the transplantation group, there was no significant difference in survival between Child-Pugh class A, B, or C patients. By the time of analysis, 52 patients in the resection group had died, including 7 postoperative hospital deaths. Most patients died of tumor recurrence in the long term (n = 37). Three patients died of decompensation of cirrhosis without tumor recurrence, whereas another 5 patients died of other causes. In the transplantation group, 4 patients died of tumor recurrence and 2 patients died of other causes.

FIGURE 1. Cumulative survival curves of the resection group (n = 204) and the transplantation group (n = 43).

FIGURE 2. Cumulative survival curves of patients without microscopic venous invasion in the resection group (n = 143) and the transplantation group (n = 37).

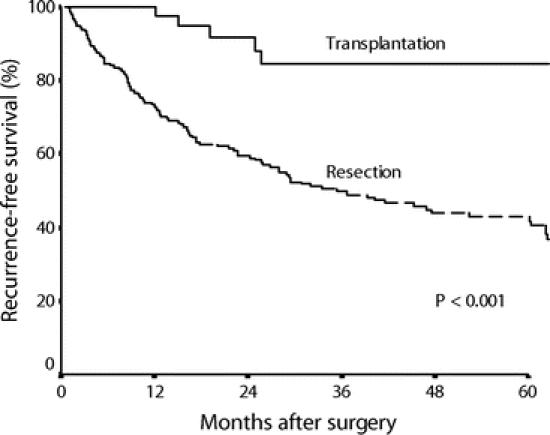

Tumor recurrence-free survival was significantly better in the transplantation group than in the resection group (5-year recurrence-free survival 84% vs. 44%, P < 0.001, Fig. 3). For patients without microscopic venous invasion, there was also a significant difference in recurrence-free survival between the transplantation group and the resection group (5-year recurrence-free survival 85% vs. 49%, P < 0.001).

FIGURE 3. Recurrence-free survival curves of the resection group (n = 194) and the transplantation group (n = 43).

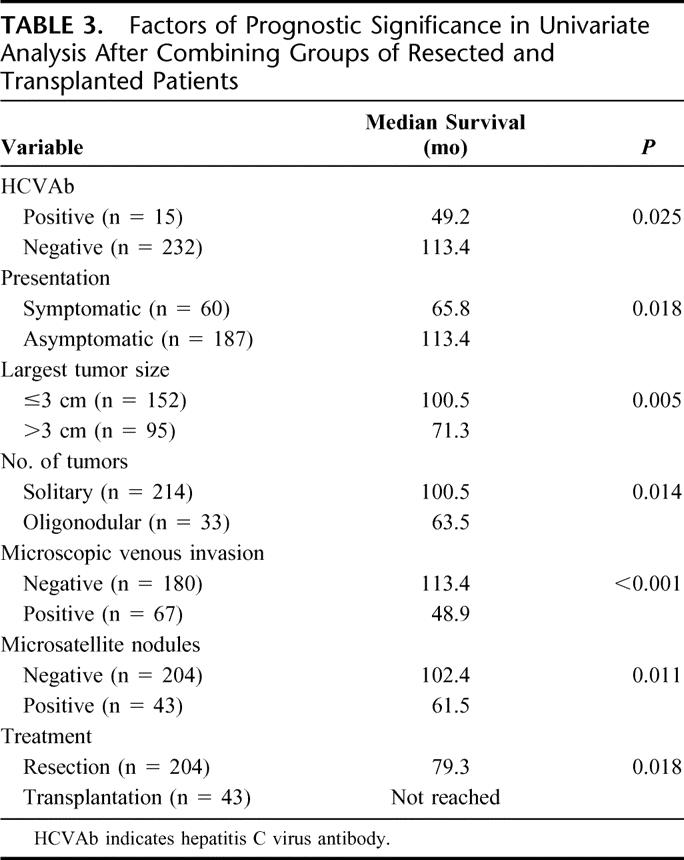

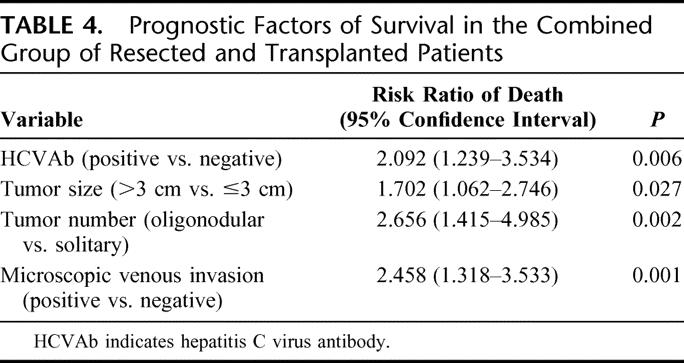

The influence of the factors listed in Table 1 and the treatment group on long-term survival was evaluated after combining the two groups of patients with resection and transplantation. The following factors were associated with worse prognosis on univariate analysis: positive hepatitis C virus antibody, symptomatic presentation, tumor diameter >3 cm, oligonodular tumors, presence of microscopic venous invasion, presence of microsatellite nodules, and treatment by resection (Table 3). Gender, age, hepatitis B surface antigen status, severity of cirrhosis, and tumor differentiation did not have statistically significant prognostic influence, although there was a trend toward better survival in patients with well-differentiated HCC compared with those with moderately or poorly differentiated HCC (P = 0.072 and P = 0.069, respectively). Those significant prognostic factors identified by the univariate analysis were entered into a Cox proportional hazards model, which revealed 4 independent adverse prognostic factors: positive hepatitis C virus antibody, tumor diameter >3 cm, oligonodular tumors, and the presence of microscopic venous invasion (Table 4). The treatment (resection or transplantation) was not a significant prognostic factor of overall survival on multivariate analysis.

TABLE 3. Factors of Prognostic Significance in Univariate Analysis After Combining Groups of Resected and Transplanted Patients

TABLE 4. Prognostic Factors of Survival in the Combined Group of Resected and Transplanted Patients

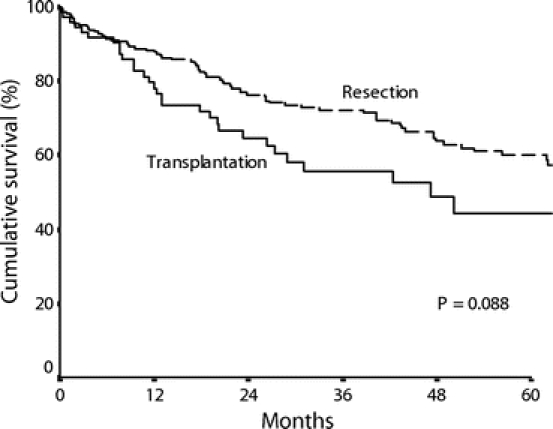

Figure 4 shows an intention-to-treat comparison of survival of patients who had HCC compatible with the Milan criteria according to preoperative imagings and were listed for resection (n = 228) or transplantation (n = 85) during the study period. There was no significant difference in survival between the two groups (5-year survival 60% vs. 44%, P = 0.088). Among the 228 patients listed for resection, 226 patients successfully underwent resection, including 22 patients found to have HCC beyond the Milan criteria on pathologic examination of the resected specimens. Two patients were found to have unresectable disease after laparoscopy or laparotomy. Among the 85 patients listed for transplantation, 50 patients underwent transplantation, but 7 were found to have HCC beyond the Milan criteria on pathologic examination of the explants. Thirty-five patients (41.2%) dropped out of the waiting list for transplantation. Tumor progression was the reason for dropout in the majority of cases (n = 21). The median waiting time until dropout in this group of patients was 12.5 months, whereas the median waiting time of the patients who received liver transplantation was 1 month. Of the 35 patients who dropped out of the transplantation list, 7 were initially assessed for live donor liver transplantation but were subsequently put on the deceased donor graft waiting list because the potential live donors were not suitable, whereas the other patients were listed for deceased donor liver transplantation from the outset. Fifteen of the 35 patients received transarterial chemoembolization and 5 patients received local ablative therapies with either ethanol injection or radiofrequency ablation for control of the tumors while they were in the transplantation waiting list.

FIGURE 4. Cumulative survival curves of all patients listed for resection (n = 228) or transplantation (n = 85) for HCC within the Milan criteria from the time they were put on list by intention-to-treat analysis.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we compared the tumor characteristics and survival results of 2 cohorts of cirrhotic patients with HCC strictly within the Milan criteria who underwent partial liver resection and liver transplantation, respectively. The two groups were different with respect to the severity of underlying cirrhosis as a result of our selection policy for liver transplantation. Because of severe graft shortage in Hong Kong, we restricted liver transplantation mainly to patients with Child-Pugh B or C cirrhosis in whom resection is contraindicated. The degree of cirrhosis may affect the perioperative outcomes. Nonetheless, there were no significant differences in hospital morbidity and mortality between the resection and transplantation groups, and there was no hospital mortality in the transplantation group. The difference in the severity of cirrhosis between the two groups may not have a significant effect on the long-term survival of the patients. In the transplantation group, long-term prognosis mainly depends on recurrence of tumors or immunosuppression-related complications rather than the preoperative severity of cirrhosis. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that Child-Pugh class was not a significant prognostic factor of survival after transplantation.24,34

Tumor recurrence is the main cause of death after both liver resection and liver transplantation for HCC, as demonstrated by data from this study and other studies.19,24,29,34,35 Hence, it is important to elucidate the tumor characteristics when comparing liver resection and transplantation for small HCC. In the literature, the relative efficacy of resection and transplantation for small HCC was often extrapolated from comparison between published results of each treatment of HCC fulfilling the Milan criteria, assuming that tumors smaller than 5 cm are early HCCs with similar tumor biology between resected patients and transplanted patients. However, it has been argued by some authors that the seemingly better results with transplantation versus liver resection may simply reflect the more stringent selection of patients,17 although no study has specifically addressed this issue thus far. This study demonstrated that, even though only tumors fulfilling the Milan criteria according to pathologic assessment were included in the analysis, there were significant differences in tumor invasiveness in the patients treated by resection and those treated by transplantation.

Our study showed that the resection group had a significantly higher proportion of tumors with microscopic venous invasion than the transplantation group. The resection group had larger tumor size, which was associated with a higher incidence of microscopic venous invasion.36 However, even when stratified according to tumor size ≤3 cm or >3 cm, the proportion of tumors with microscopic venous invasion was still significantly higher in the resection group. Tumors in the resection group also had a higher proportion of poorly differentiated HCC and a higher rate of microsatellite nodules. There are two likely explanations for such differences in tumor aggressiveness. First, patients who received transplantation for HCC had undergone a natural selection process in which patients with more aggressive tumor phenotypes such as the presence of microvascular invasion and microscopic metastasis had dropped out of the waiting list because of tumor progression. Such a selection process did not occur in patients who were listed for resection. Second, a higher proportion of patients in the transplantation group had HCC detected by regular screening rather than symptomatic presentation compared with the resection group. Tumors detected by regular screening may represent earlier tumors in terms of biologic aggressiveness compared with patients detected after symptomatic presentation. Regular surveillance with ultrasound and serum AFP level can detect early well-differentiated HCC in cirrhotic livers, which frequently arises from dysplastic nodules.37,38 Indeed, there was a higher proportion of well-differentiated HCC in the transplantation group. Most of the patients in the transplantation group had Child-Pugh class B or C cirrhosis, and they were more likely to be already under the care of physicians with regular surveillance for HCC, whereas Child-Pugh class A patients were less likely to have regular surveillance because they were asymptomatic before the development of HCC.

Microscopic venous invasion has been shown by numerous studies to be the most important adverse prognostic factor for both liver resection and transplantation for HCC.8,25,35,36,39 Our study showed a significant impact of the difference in the rate of microscopic venous invasion between resected and transplanted patients on the long-term survival. The overall survival of patients in the transplantation group was significantly better than that of patients in the resection group, as shown by the 5-year survival of 81% and 68%, respectively. Without special reference to tumor characteristics, this result seems to confirm that transplantation is superior to liver resection. However, when stratified according to the presence or absence of microscopic venous invasion, there was no significant difference in the survival result between the transplantation group and the resection group. To evaluate whether treatment with resection or transplantation had a significant independent effect on long-term survival in the whole group of patients, a multivariate analysis was performed, which revealed that tumor factors, but not treatment, were the factors that determined the prognosis. Tumor size, tumor number, and microscopic venous invasion were the independent prognostic factors of overall survival. These factors have been shown to have prognostic significance after resection or transplantation for small HCC.19,26,40,41 Hepatitis C virus infection was another independent adverse prognostic factor. Previous studies have shown that patients with HCV infection have worse prognosis compared with those with HBV infection after resection because they are prone to a higher risk of multicentric tumor recurrence.42,43 Furthermore, the higher incidence of recurrent hepatitis C after transplantation compared with recurrent hepatitis B lowers patient survival independent of tumor recurrence.4

Tumor recurrence-free survival was significantly better after liver transplantation than after resection, even when patients without microscopic venous invasion were analyzed separately. In liver transplantation, the whole cirrhotic liver and hence the risk of multicentric tumor recurrence are removed. A major argument for the recommendation of liver transplantation over resection for patients with early HCC associated with compensated cirrhosis is the lower tumor recurrence rate. However, liver transplantation is associated with other long-term problems such as graft rejection, recurrent viral hepatitis, or immunosuppression-related complications, which may cause mortality. This explains a similar overall survival after resection and transplantation for HCC observed in some studies despite the higher tumor recurrence rate after resection.13,26,27 Because of the different nature of treatments and the associated long-term problems, overall survival rather than tumor recurrence-free survival should be considered the primary outcome in comparison of the two treatments, as it is the gold standard endpoint of any cancer treatment.

The shortage of donor organs is another factor that should be taken into account in considering whether liver resection or transplantation should be offered for HCC fulfilling the Milan criteria in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Previous studies have demonstrated a high dropout rate of 20% or more among patients with HCC on liver transplantation list if the waiting time is greater than 6 months.15,18 Even in countries where patients with HCC fulfilling the Milan criteria are given priority in the transplant waiting list, dropout is still common.4 Because of the severe shortage of deceased donor organs in Hong Kong, we do not give priority to HCC patients, and our dropout rate is even higher because of the long waiting time of greater than 1 year. To evaluate the impact of dropout on overall survival of patients listed for liver transplantation or resection, intention-to-treat analysis is necessary.18,44 Hence, in this study, we also performed an intention-to-treat analysis of patients listed for resection or transplantation who had HCC fulfilling the Milan criteria based on preoperative imagings. Indeed, the survival of the group of patients listed for transplantation was worse than that of the group of patients listed for resection (5-year survival, 44% vs. 60%) because of the high dropout rate in the transplantation group, although the difference was not statistically significant. The dropout rate from the waiting list in our center was high despite the application of live donor liver transplantation in a large proportion of transplanted patients. The use of live donor liver grafts expands the application of liver transplantation for HCC.45,46 However, the impact of live donor liver transplantation on the management of HCC remains limited.3 A recent study from our group has demonstrated that only about half of our HCC patients evaluated for live donor liver transplantation eventually received the transplantation because a suitable live donor was not available in the other patients.32 The risk to the donor is also a major concern in live donor liver transplantation for HCC.

The ideal study to resolve the debate of resection or transplantation for small HCC in cirrhotic patients is a prospective randomized trial with overall long-term survival as the primary endpoint. However, it is practically impossible to conduct such a trial because the option of transplantation is limited by the shortage of deceased donor liver grafts. Hence, the appraisal of the relative benefit of transplantation versus resection depends on a critical analysis of long-term survival outcome of cohorts of patients treated with transplantation and resection, respectively. The importance of intention-to-treat analysis to include the survival outcome of patients who are put on transplantation waiting list but eventually do not receive transplantation because of tumor progression has been emphasized by previous studies comparing liver transplantation and resection for small HCC.18,44 The dropout of patients with aggressive tumors while waiting for transplantation could also result in a bias in tumor characteristics in favor of transplanted patients when comparing patients who do receive transplantation and those treated by resection for apparently similar tumors according to the Milan criteria. This is an important bias that needs to be taken into account when comparing the results of transplantation and resection for small HCC, but the impact of such a bias has not been addressed by previous studies. To our knowledge, this study was the first one to evaluate the impact of difference in tumor aggressiveness on long-term survival in resected patients and transplanted patients with HCC fulfilling the Milan criteria. Our data showed that the 5-year overall survival after transplantation and resection was similar when difference in tumor pathologic features such as microscopic vascular invasion was taken into account, and the treatment itself was not a significant prognostic factor of survival in the multivariate analysis. Hence, we recommended liver resection as the first-line therapy for HCC fulfilling the Milan criteria in patients with compensated cirrhosis, especially in places where the shortage of deceased donor liver grafts is a severe problem.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that there was a significant difference in pathologic features of tumor aggressiveness among patients who underwent resection and those who underwent liver transplantation for HCC fulfilling the Milan criteria. When adjusted for the presence or absence of microscopic venous invasion, there was no significant difference in overall survival after resection and transplantation. This bias in tumor characteristics in favor of transplanted patients as a result of selection while waiting in the transplantation list should be taken into account when comparing survival after resection and transplantation for small HCC.

Footnotes

Supported by the Sun C.Y. Research Foundation for Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery of the University of Hong Kong.

Reprints: Ronnie T. P. Poon, MS, Department of Surgery, University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, 102 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China. E-mail: poontp@hkucc.hku.hk.

REFERENCES

- 1.el-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2001;5:87–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Improving survival results after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study of 377 patients over 10 years. Ann Surg. 2001;234:63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet JM, Schwartz M, Mazzaferro V. Resection and liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:181–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz M. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 suppl 1):268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurtovic J, Riordan SM, Williams R. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:147–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song TJ, Ip EW, Fong Y. Hepatocellular carcinoma: current surgical management. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 suppl 1):248–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benckert C, Jonas S, Thelen A, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: prognostic parameters. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1693–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lohe F, Angele MK, Gerbes AL, et al. Tumour size is an important predictor for the outcome after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;[Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Ravaioli M, Ercolani G, Cescon M, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: further considerations on selection criteria. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1195–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of the proposed UCSF criteria with the Milan criteria and the Pittsburgh modified TNM criteria. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hertl M, Cosimi AB. Liver transplantation for malignancy. Oncologist. 2005;10:269–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Figueras J, Jaurrieta E, Valls C, et al. Resection or transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: outcomes based on indicated treatment strategy. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:580–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCormack L, Petrowsky H, Clavien PA. Surgical therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarasin FP, Giostra E, Mentha G, et al. Partial hepatectomy or orthotopic liver transplantation for the treatment of resectable hepatocellular carcinoma? A cost-effectiveness perspective. Hepatology. 1998;28:436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Long-term prognosis after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis B-related cirrhosis. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1094–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cha CH, Ruo L, Fong Y, et al. Resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients otherwise eligible for transplantation. Ann Surg. 2003;238:315–321; discussion 321–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J. Intention-to-treat analysis of surgical treatment for early hepatocellular carcinoma: resection versus transplantation. Hepatology. 1999;30:1434–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Long-term survival and pattern of recurrence after resection of small hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with preserved liver function: implications for a strategy of salvage transplantation. Ann Surg. 2002;235:373–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esquivel CO. Is liver transplantation justified for the treatment of HCC in Child's A patients? Not always. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:521–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bismuth H, Chiche L, Adam R, et al. Liver resection versus transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Ann Surg. 1993;218:145–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vargas V, Castells L, Balsells J, et al. Hepatic resection or orthotopic liver transplant in cirrhotic patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:1243–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan KC, Rela M, Ryder SD, et al. Experience of orthotopic liver transplantation and hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma of less than 8 cm in patients with cirrhosis. Br J Surg. 1995;82:253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michel J, Suc B, Montpeyroux F, et al. Liver resection or transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma? Retrospective analysis of 215 patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1997;26:1274–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Philosophe B, Greig PD, Hemming AW, et al. Surgical management of hepatocellular carcinoma: resection or transplantation? J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otto G, Heuschen U, Hofmann WJ, et al. Survival and recurrence after liver transplantation versus liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective analysis. Ann Surg. 1998;227:424–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto J, Iwatsuki S, Kosuge T, et al. Should hepatomas be treated with hepatic resection or transplantation? Cancer. 1999;86:1151–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Carlis L, Sammartino C, Giacomoni A, et al. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: resection or transplantation? Results of a multivariate analysis. Chir Ital. 2001;53:579–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bigourdan JM, Jaeck D, Meyer N, et al. Small hepatocellular carcinoma in Child A cirrhotic patients: hepatic resection versus transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Improving perioperative outcome expands the role of hepatectomy in management of benign and malignant hepatobiliary diseases: analysis of 1222 consecutive patients from a prospective database. Ann Surg. 2004;240:698–708; discussion 708–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, et al. Determinants of hospital mortality of adult recipients of right lobe live donor liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2003;238:864–869; discussion 869–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, et al. The role and limitation of living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:440–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edmonson HA SP. Primary carcinoma of the liver: a study of 100 cases among 48,900 necropsies. Cancer. 1954;7:462–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamura S, Kato T, Berho M, et al. Impact of histological grade of hepatocellular carcinoma on the outcome of liver transplantation. Arch Surg. 2001;136:25–30; discussion 31. [PubMed]

- 35.Shimoda M, Ghobrial RM, Carmody IC, et al. Predictors of survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis C. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1478–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pawlik TM, Delman KA, Vauthey JN, et al. Tumor size predicts vascular invasion and histologic grade: implications for selection of surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kojiro M, Roskams T. Early hepatocellular carcinoma and dysplastic nodules. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murakami T, Mochizuki K, Nakamura H. Imaging evaluation of the cirrhotic liver. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Intrahepatic recurrence after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term results of treatment and prognostic factors. Ann Surg. 1999;229:216–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iwatsuki S, Dvorchik I, Marsh JW, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a proposal of a prognostic scoring system. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:389–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikai I, Arii S, Kojiro M, et al. Reevaluation of prognostic factors for survival after liver resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in a Japanese nationwide survey. Cancer. 2004;101:796–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakai T, Shirai Y, Yokoyama N, et al. Hepatitis viral status affects the pattern of intrahepatic recurrence after resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang YH, Wu JC, Chen CH, et al. Comparison of recurrence after hepatic resection in patients with hepatitis B vs. hepatitis C-related small hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus endemic area. Liver Int. 2005;25:236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yao FY, Bass NM, Nikolai B, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of survival according to the intention-to-treat principle and dropout from the waiting list. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:873–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaihara S, Kiuchi T, Ueda M, et al. Living-donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplantation. 2003;75(suppl 3):37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gondolesi GE, Roayaie S, Munoz L, et al. Adult living donor liver transplantation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: extending UNOS priority criteria. Ann Surg. 2004;239:142–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]