Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to determine the relationship of race and socioeconomic factors and the method used for appendectomies in children (open vs. laparoscopic).

Summary Background Data:

Previous studies have shown racial and insurance-related differences associated with the management of appendicitis in adults. It is not known whether these differences are observed in children.

Methods:

Children (<15 years) undergoing appendectomy from 1996 to 2002 were identified in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Severity of appendicitis and underlying chronic illnesses were determined by ICD-9 codes. Hospital characteristics evaluated included teaching status and location, children’s hospital status, and volume of appendectomies. Hierarchical unadjusted and risk-adjusted logistic regression analyses were performed.

Results:

Among 72,189 children undergoing an appendectomy for appendicitis, 11,714 (16%) underwent a laparoscopic appendectomy. Multivariate analysis showed that whites were more likely to undergo a laparoscopic appendectomy than blacks (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.03–1.25, P = 0.01) but not other races. A significant interaction between payer source and children’s hospital designation was observed, with the odds of children with private insurance undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy being significantly higher than those without private insurance at nonchildren’s hospitals but not at children’s hospitals.

Conclusions:

There are significant racial and insurance-related differences in use of laparoscopic appendectomy in children that are most evident at nonchildren’s hospitals. These findings provide evidence that factors at hospitals dedicated to children may lead to better access to new technologies.

Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample were used to evaluate the effects of race and socioeconomic factors on the method used for appendectomies in children (open vs. laparoscopic). There were significant differences based on race and insurance status in the application of laparoscopic appendectomy that were observed at nonchildren’s hospitals but not children’s hospitals.

Since its introduction in the early 1980s, laparoscopic appendectomy has been performed as an alternative to open appendectomy among adults and children with acute appendicitis. While some studies have shown no clear benefit of laparoscopic appendectomy over open appendectomy, other studies have suggested that laparoscopic appendectomy is associated with shorter hospital stay, less postoperative pain, earlier return to daily activity, and lower cost.1–6 The benefits of laparoscopic appendectomy are also controversial among children.7–10 Although a clear advantage of the laparoscopic approach has not been firmly established, there is evidence that this approach is increasingly being used in all age groups.11

It has been well established that there are racial and socioeconomic differences in the presentation of pediatric appendicitis. Higher rates of appendiceal rupture have been observed among children who are from lower income areas, lack private insurance, or are minorities. Reasons that have been suggested for these observations include delays in seeking care or timeliness of diagnosis by providers that may be attributable to access to and quality of care.12,13 Previous evidence has suggested that there are racial and socioeconomic disparities in the treatment of appendicitis that exist at presentation even when accounting for the severity of disease. In an analysis of patients selected from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), white race and private insurance status were observed to be independent predictors of undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy.14 While this study included adults and children, children were not separately analyzed. In addition, the impact of hospital-related factors on potential treatment disparities was not evaluated.

In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that race and socioeconomic factors are associated with the likelihood of children undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy. In addition to considering patient-related factors, we also considered the impact of hospital characteristics on treatment differences because of potential hospital effects on disparities.15,16

METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Data were obtained from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) NIS from year 1996 to 2002. The NIS contains discharges from a 20% sample of community (non-federal) hospitals in the United States. The database contains information that is found in a typical discharge abstract including diagnosis and procedure codes defined using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9). Children (age <15 years) with an ICD-9 diagnosis code for appendicitis (540.0, appendicitis with generalized peritonitis; 540.1, appendicitis with peritoneal abscess; 540.9, appendicitis without mention of peritonitis; 541, appendicitis, unqualified; 542, other appendicitis) and appendectomy (47.0; appendectomy; 47.01, laparoscopic appendectomy; 47.09, other appendectomy) were identified. The severity of appendicitis was classified as nonperforated appendicitis (540.9, 541, 542), perforated appendicitis with no abscess (540.0) or perforated appendicitis with abscess (540.1). Patients were considered to have undergone a laparoscopic appendectomy if a code for laparoscopic appendectomy (47.01), other laparoscopic procedure (54.21, laparoscopy; 54.51, laparoscopic lysis of peritoneal adhesions), or conversion from a laparoscopic to open procedure (V64.4) was recorded. This definition of laparoscopic appendectomy was based on “intent to treat.” To exclude children undergoing an incidental appendectomy, records were not included if an ICD-9 code for incidental appendectomy (47.1, 47.11, or 47.19) or for another major abdominal procedure was found.

Study Variables

Patient-related variables potentially associated with the performance of laparoscopic appendectomy were identified in the database and included age, gender, race, estimated median household income, payer source, and transfer status (transferred or not transferred from another acute care hospital). Race was designated as “Other” if not identified as Asian/Pacific Islander, black, white, or Hispanic. Household income is estimated in the NIS based on the median income of the patient’s ZIP code of residence derived from projections from the 1990 U.S. Census. Medicaid and Medicare were collapsed into a single-payer source category. Payer sources identified as self-pay, no charge, or other payer types were designated as “Other.” Thirteen categories of chronic disease were identified using ICD-9 codes.17

Hospital-related variables potentially associated with the performance of laparoscopic appendectomy were also identified in the database and included census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), hospital teaching status (nonteaching vs. teaching) and hospital location (urban vs. rural). Children’s hospital designation (a nonchildren’s hospital, a children’s unit in a general hospital, or a children’s general hospital) was obtained from the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions (NACHRI, Alexandria, VA). The volume of pediatric (age <15 years) appendectomies performed in each hospital in each year was determined. Because of skewed distribution, hospital volume of appendectomies was divided into groups based on the cutoffs that best divided hospitals into 5 equal groups (quintiles).

Missing data were observed for several variables including race, estimated household income, payer source, and children’s hospital designation. Among these variables, only race (22% of records) and children’s hospital designation (17% of records) were missing in more than 3% of records. Race was most commonly not available in the database because individual hospitals did not record this variable. Among the 2449 hospitals treating children with appendicitis during the study period, 659 (27%) did not report race in any record. Most records with missing race (87%) were obtained from hospitals with a standard practice of not recording this variable. While these observations suggested that the pattern of missing race was missing completely at random, we also performed multiple imputation to verify that omission of records with missing race did not lead to biased results.18 Several states did not report hospital names preventing assignment of children’s hospital status in 589 (24%) hospitals using NACHRI records. Because children’s hospital designation was missing completely at random, values in this field were allowed to enter the regression models as missing.

Statistical Analysis

Procedure counts were estimated using hospital-specific discharge weight using the survey commands in Stata 8.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). U.S. census population estimates were used to estimate the population-based incidence of appendectomies in each year.19 The impact of patient and hospital characteristics on the binary outcome, approach to appendectomy (open vs. laparoscopic), was modeled using a generalized estimating equation approach (PROC GENMOD, SAS 8.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to control for clustering within hospitals. Both univariate and multivariate analyses were performed. The reference group for each analysis consisted of the largest group for each categorical variable. Estimates of the adjusted regression coefficients and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated. A backward elimination strategy was used to select predictors for the final multivariate model with exclusion if significance was observed at P > 0.05. Interaction terms were also considered and included in the final model when significant at the P < 0.05 level. Interactions considered included age and gender, age and severity of appendicitis, payer source and children’s hospital designation and race and children’s hospital designation.

Multiple imputation was used to construct 8 imputed datasets from the data. Race was imputed using values of all other variables. The logistic regression analyses were then repeated on each of the 8 imputed datasets and combined to give the final result. Multiple imputation was performed using SAS 8.2 (PROC MI and PROC MIANALYZE, SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Overview of Data

From 1996 to 2002, 72,189 appendectomies performed for appendicitis in children were recorded in the NIS, yielding a total national estimate of 356,961 procedures during this period. These procedures included an estimate of 46,157 appendectomies performed in 1996, 46,946 in 1997, 47,824 in 1998, 53,717 in 1999, 53,801 in 2000, 55,446 in 2001, and 53,068 in 2002. The national rate of appendectomies among children <15-year-old increased from 80 procedures per 100,000 in 1996 to 90 procedures per 100,000 population in 2002. Overall, 16% of procedures were performed laparoscopically, increasing from 6% in 1996 to 24% in 2002 (P < 0.001).

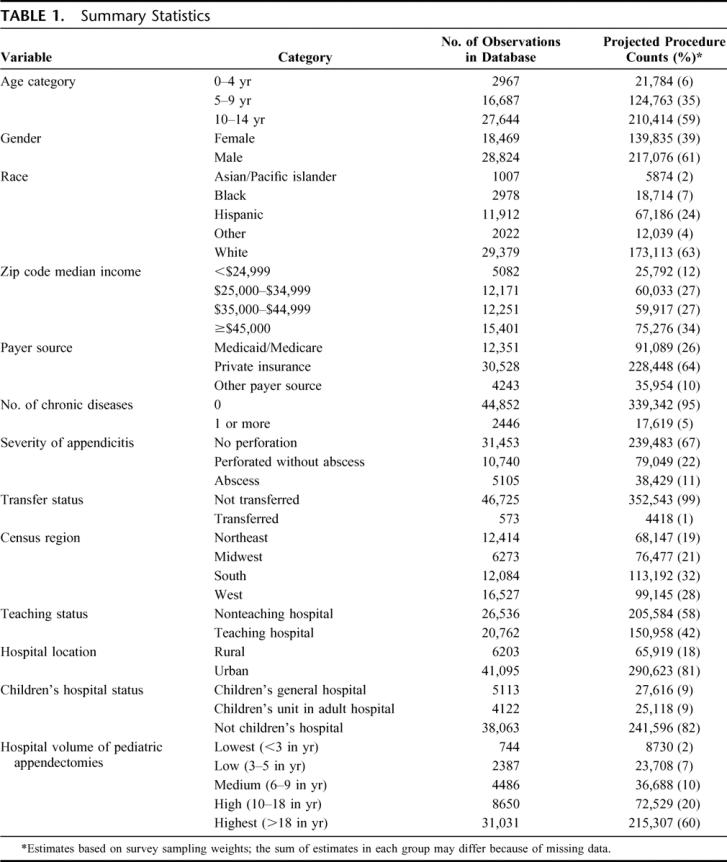

A summary of projected procedure counts is shown in Table 1. The largest group of children was those age 10 to 14 years. Most patients were male, white, from areas with the highest median income, and had private insurance. Underlying chronic diseases were uncommon. More children had nonperforated appendicitis than other types of appendicitis. More children were treated at nonteaching hospitals, urban hospitals, and nonchildren hospitals. Children most commonly underwent appendectomy at hospitals with the highest volume.

TABLE 1. Summary Statistics

Among the 2449 hospitals included in the database, most were nonteaching (n = 1953, 80%) and located in an urban setting (n = 1518, 62%). Among the 1860 hospitals with a children’s hospital designation, 1800 (97%) were nonchildren’s hospitals, 40 (2%) were children’s units in adult general hospitals, and 20 (1%) were children’s general hospitals.

Univariate Analysis

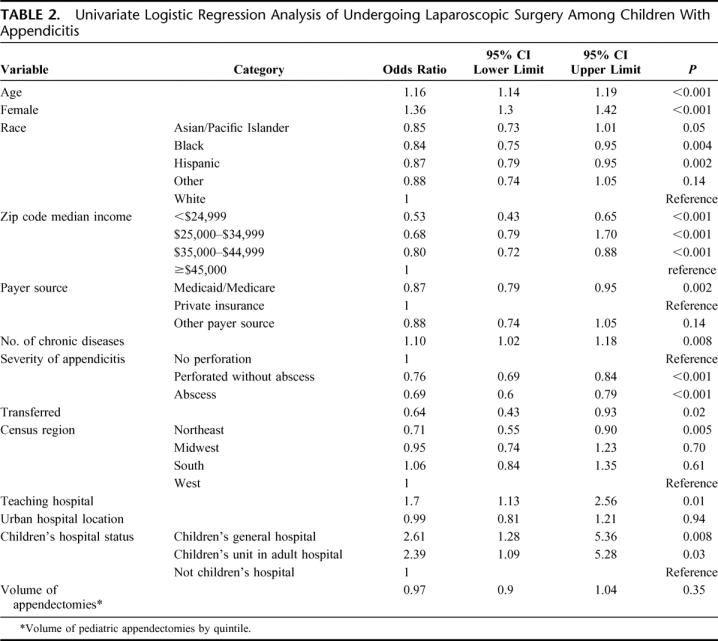

Univariate logistic regression identified several factors associated with laparoscopic surgery (Table 2). The odds of undergoing a laparoscopic procedure were higher as age increased and was higher in females than in males. Blacks and Hispanics were less likely to undergo a laparoscopic procedure compared with whites. With increasing estimated income, laparoscopic appendectomy was more frequent than open appendectomy. Children with Medicaid or Medicare had lower odds of undergoing laparoscopic surgery than those with private insurance. While laparoscopy was less likely among children with complicated appendicitis, the presence of a chronic disease was associated with higher odds of undergoing laparoscopy. Children who were transferred from another hospital were less likely to undergo laparoscopic appendectomy than those treated at only one hospital. A laparoscopic appendectomy was more commonly performed among those treated at teaching hospitals or at a children’s hospital.

TABLE 2. Univariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Undergoing Laparoscopic Surgery Among Children With Appendicitis

Multivariate Analysis

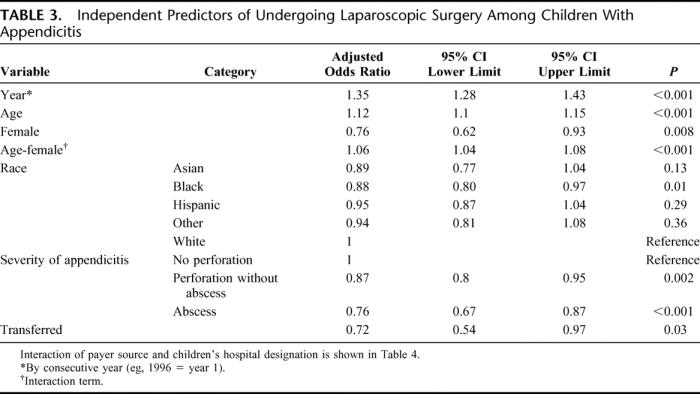

An initial multivariate regression model was constructed to identify independent predictors of undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy (Tables 3, 4). Procedures performed in later calendar years had higher odds of being done by a laparoscopic than an open approach. A significant interaction between age and gender was observed in this model, with laparoscopic appendectomy being more likely with increasing age in females than in males. Both increasing age and female gender were independently associated with laparoscopic appendectomy when the model was run without the interaction term. In contrast to findings in the univariate analyses, blacks but not Hispanics had lower odds of undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy than whites. Children with evidence of perforation were less likely to undergo laparoscopic appendectomy than those with uncomplicated appendicitis as were those transferred from another hospital (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Independent Predictors of Undergoing Laparoscopic Surgery Among Children With Appendicitis

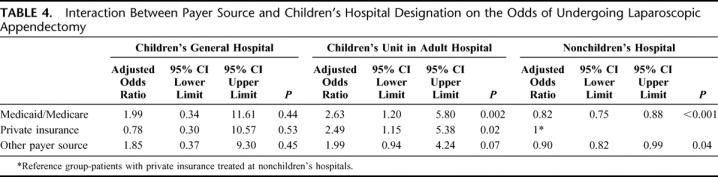

TABLE 4. Interaction Between Payer Source and Children’s Hospital Designation on the Odds of Undergoing Laparoscopic Appendectomy

A significant interaction between payer source and children’s hospital designation was observed (Table 4). Children with either Medicaid/Medicare or other payers who were treated at a nonchildren’s hospital had lower odds of undergoing a laparoscopic procedure than those with private insurance. The odds of a laparoscopic procedure among children treated at a children’s general hospital was not significantly different regardless of payer source when compared with those with private insurance treated at a nonchildren’s hospital. In contrast, children treated in a children’s unit of an adult hospital with either Medicare/Medicaid or private insurance had a higher odds of undergoing a laparoscopic procedure (Table 4). No significant association between estimated household income and odds of undergoing a laparoscopic appendectomy was observed even when race or payer source was not included in the model. Other variables excluded from the final model because of lack of significance included the number of chronic diseases, hospital teaching status, hospital location, hospital region, and volume of appendectomies.

The reference group used for calculating the odds ratios in the interaction between children’s hospital designation and payer source was then changed to facilitate comparisons at each type of children’s hospital. When the reference group was changed to children with private insurance treated at children’s general hospitals, those with Medicaid/Medicare treated at these hospitals were observed to have significantly higher odds of undergoing a laparoscopic procedure (odds radio [OR], 1.12; 95% CI, 1.01–1.26, P = 0.04) than those with private insurance, while the odds of those with other payer sources treated at these hospitals was not significantly different than those with private insurance (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.76–1.42, P = 0.79). When the reference group was changed to children with private insurance treated at children’s units in adult general hospitals, those with Medicaid/Medicare treated at these hospitals did not have significantly different odds of undergoing a laparoscopic procedure (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.91–1.24, P = 0.47) than those with private insurance, while the odds of those with other payer sources (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66–0.97, P = 0.02) was significantly lower than those with private insurance.

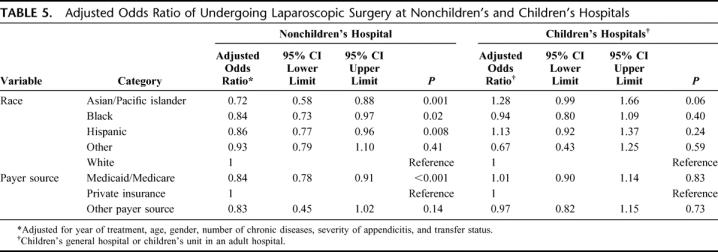

Separate risk-adjusted analyses were then performed using only records of children treated at nonchildren’s hospitals or at children’s hospitals (either children’s general hospitals or children’s units in adult general hospitals). At nonchildren’s hospitals, Asian/Pacific Islander, black, and Hispanic children had significantly lower odds of undergoing a laparoscopic appendectomy compared with white children. Children with Medicaid/Medicare but not other payer sources had significantly lower odds of undergoing a laparoscopic procedure compared with those with private insurance (Table 5). At children’s hospitals, no significant differences were observed in the odds of undergoing laparoscopy between white children and those of other races or between children with private insurance and those with other insurance types (Table 5). When children from children’s general hospitals and children’s units in adult general hospitals were analyzed separately, no significant differences were observed in odds of laparoscopic surgery based on either race or payer source.

TABLE 5. Adjusted Odds Ratio of Undergoing Laparoscopic Surgery at Nonchildren’s and Children’s Hospitals

Each multivariate analysis was repeated using multiple imputation to evaluate the effect of missing race on the final results. None of the conclusions differed when records with missing data were included using imputed values for race.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed significant differences in the application of laparoscopy for the treatment of appendicitis in children based on both race and payer source. Overall, whites were more likely to undergo a laparoscopic appendectomy than blacks. When analyzed by children’s hospital designation, white children were observed to be more likely to undergo laparoscopy at nonchildren’s hospitals than children of other races, while no racial differences were observed at children’s hospitals. Children with Medicaid or Medicare were less likely overall to undergo a laparoscopic appendectomy than children with private insurance. Analysis using an interaction term between payer source and children’s hospital designation as well as separate analyses based on children’s hospital designation showed that this finding was observed at nonchildren’s hospitals but not at children’s hospitals.

Differences in treatment based on racial and socioeconomic factors have recently been described for a variety of conditions requiring surgical care in addition to appendicitis in adults including cardiac disease, cancer, joint disease, vascular disease, and renal failure.20–24 Potential disparities have also been observed in the surgical treatment of congenital heart disease and the access to cochlear implantation for hearing loss in children.25–27 Disparities in surgical treatment are likely to be multifactorial and related to disease- and region-specific factors. Factors that may contribute to differential access to surgical treatment options may include provider bias, patient education, cultural beliefs, geographic factors limiting access to care, and access to health insurance.

The implications of choosing either open or laparoscopic appendectomy for the treatment of appendicitis are fundamentally different than choosing treatment options for other diseases. To date, an unequivocal benefit of laparoscopic appendectomy approach has not been shown, potentially due to only a small incremental advantage of laparoscopy. While it may be argued that the cosmetic appearance of the abdomen after a laparoscopic appendectomy may be better, many children, particularly those who are very thin, have a very acceptable postoperative appearance with a small right lower quadrant incision. Regardless of whether an open or laparoscopic approach is used, the primary goal of treatment is achieved with both: removal of the inflamed appendix. In contrast, the decision to perform other procedures such as a joint replacement for degenerative joint disease or a kidney transplant for end-stage renal disease has more profound implications for the well-being of the patient. Nevertheless, our findings that differences in treatment of appendicitis relate to nonmedical factors remain important and need additional study.

There are several limitations of this study that should be considered. While analyzing a large, nationally representative database has advantages, there are well-known limitations to the use of a large administrative dataset such as the NIS. Diagnosis and procedure coding may have inaccuracies when used for risk-stratification or for record inclusion or exclusion. In particular, we used diagnosis codes to establish the severity of appendicitis because we could not use more accurate operative report descriptions or pathology reports. Because severity of appendicitis has been shown to be an important factor affecting the surgeon’s decision to perform a laparoscopic procedure,28 stratification by severity using administrative codes was required. Other studies have also used administrative data for stratifying the severity of appendicitis and have the same limitation.11,14,29

While we have considered several patient-related factors for stratification, there may be other factors related to race or insurance type that more directly account for our findings. One such factor that should be considered is obesity. It has been shown that obesity is increasing in Hispanic and black children and among children in lower socioeconomic groups.30,31 Because obesity is a factor considered by many surgeons when determining the approach used for appendectomy, addition of body mass index to our analyses may have altered our findings. Nevertheless, because obesity may lead many surgeons to choose a laparoscopic approach, addition of this factor could be predicted to strengthen rather than diminish effects of race and insurance type.

We also were unable to determine the reasons for hospital-related differences in the application of laparoscopy using available data in the NIS. In particular, we could not evaluate the effects of surgeon experience or training on surgical approach.28 While differential access to laparoscopy may explain the observed disparities, we could not exclude the possibility that surgeon-related factors also contributed. These factors are important to consider because it is primarily the surgeon who determines the approach used. The NIS contains physician identifiers that have been used in previous studies to track the operative experience of individual surgeons and to assess each surgeon’s area of specialization.32,33 Because several states do not report physician identifiers that are unique to each physician, the NIS has limited usefulness when used for these purposes. It is likely that surgeons operating at children’s hospitals will have specialty training in pediatric surgery, while it is likely that most at nonchildren’s hospitals do not have this added training. Because of these trends, children’s hospital designation may be a surrogate measure of surgeon training or for ongoing experience treating children. In this way, differences in application of laparoscopy may not be directly related to the type of hospital but to the type of surgeons who operate at each type of hospital. Referral practices within hospitals could also direct patients to surgeons who are more or less likely to perform a laparoscopic appendectomy based on nonmedical factors. Finally, because surgeons at children’s hospitals are more likely to be early adopters of laparoscopy for children, the absence of disparities at children’s hospitals may be due to wider availability of laparoscopy at these institutions. This hypothesis is supported by recent data showing that differences in care may be directly linked to the availability of treatment options at hospitals chosen by different racial groups rather than to race itself.15,16

The impact of parental influence and choice on the method of appendectomy is an additional factor that cannot be analyzed using this dataset. The availability of new technologies such as laparoscopy may serve to bring out disparities in care related to the socioeconomic status of parents. Reasons that may lead to more rapid utilization of new treatments among patients of higher socioeconomic status include improved access to medical information, greater influence on providers, and better social connection with similarly treated peers.34 While most parents will not be aware of the controversies surrounding the use of laparoscopic appendectomy, it is likely that many will be aware of the general benefits of laparoscopy. Because the incremental benefit of laparoscopic appendectomy is likely to be small if it exists, parental influence may prove to be an additional factor tipping the decision for or against laparoscopic appendectomy in some settings.

Finally, the use of administrative data to evaluate race-related effects should also be viewed with caution. Because race is not used for reimbursement, this variable is not included in the most commonly used format for collecting discharge data, the Uniform Bill for Hospitals (UB-92). Because of its potential importance, most states have included race as part of their discharge data collection. In states that collect data on race, this variable is usually collected on admission by administrative staff. While race may be self-reported, some hospitals allow staff to record this variable when it is clearly evident (HCUP Technical Assistance, e-mail communication, September 22, 2005). The effect of these collection methods on the accuracy of race designation is not known.

CONCLUSION

Our study suggests that there are disparities associated with nonmedical factors in the treatment of appendicitis, one of the most common diseases requiring surgery in children. While our study does not directly prove that racial and economic factors led to variable utilization of laparoscopy, our findings are consistent with recent studies showing the association between nonmedical factors and the rate of diffusion of new technologies into a population.16,35 Our findings also provide additional evidence for a strong effect of hospital-related factors on treatment disparities and the need to include hospital-level variables in these types of analyses.15,16 The existence of disparities in treatment of appendicitis suggests a need to identify differences in access to care for other diseases in children that may require surgical treatment. The goal of these efforts should be to reduce inequities and improve care for all children using available technologies.

Footnotes

Presented at the Surgical Forum, American College of Surgeons 91st Annual Clinical Congress, San Francisco, CA, October 18, 2005.

Reprints: Randall S. Burd, MD, PhD, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Department of Surgery, Division of Pediatric Surgery, One Robert Wood Johnson Place, PO Box 19, New Brunswick, NJ 08903. E-mail: burdrs@umdnj.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Minne L, Varner D, Burnell A, et al. Laparoscopic vs open appendectomy: prospective randomized study of outcomes. Arch Surg. 1997;132:708–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long KH, Bannon MP, Zietlow SP, et al. Laparoscopic Appendectomy Interest Group. A prospective randomized comparison of laparoscopic appendectomy with open appendectomy: clinical and economic analyses. Surgery. 2001;129:390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ignacio RC, Burke R, Spencer D, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: what is the real difference? Results of a prospective randomized double-blinded trial. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:334–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katkhouda N, Mason RJ, Towfigh S, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: a prospective randomized double-blind study. Ann Surg. 2005;242:439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olmi S, Magnone S, Bertolini A, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in acute appendicitis: a randomized prospective study. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1193–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moberg AC, Berndsen F, Palmquist I, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy for confirmed appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2005;92:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavonius MI, Liesjarvi S, Ovaska J, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in children: a prospective randomized study. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2001;11:235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little DC, Custer MD, May BH, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy: an unnecessary and expensive procedure in children?. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oka T, Kurkchubasche AG, Bussey JG, et al. Open and laparoscopic appendectomy are equally safe and acceptable in children. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lintula H, Kokki H, Vanamo K, et al. The costs and effects of laparoscopic appendectomy in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:34–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen NT, Zainabadi K, Mavandadi S, et al. Trends in utilization and outcomes of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy. Am J Surg. 2004;188:813–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guagliardo MF, Teach SJ, Huang ZJ, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric appendicitis rupture rate. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1218–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smink DS, Fishman SJ, Kleinman K, et al. Effects of race, insurance status, and hospital volume on perforated appendicitis in children. Pediatrics. 2005;115:920–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guller U, Jain N, Curtis LH, et al. Insurance status and race represent independent predictors of undergoing laparoscopic surgery for appendicitis: secondary data analysis of 145,546 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnato AE, Lucas FL, Staiger D, et al. Hospital-level racial disparities in acute myocardial infarction treatment and outcomes. Med Care. 2005;43:308–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groeneveld PW, Laufer SB, Garber AM. Technology diffusion, hospital variation, and racial disparities among elderly Medicare beneficiaries: 1989–2000. Med Care. 2005;43:320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silber JH, Gleeson SP, Zhao H. The influence of chronic disease on resource utilization in common acute pediatric conditions: financial concerns for children’s hospitals. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.http://www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p25-1130/p251130.pdf, Accessed on October 31, 2005.

- 20.Bertoni AG, Goonan KL, Bonds DE, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in cardiac catheterization for acute myocardial infarction in the United States, 1995–2001. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:317–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Underwood W 3rd, Jackson J, Wei JT, et al. Racial treatment trends in localized/regional prostate carcinoma: 1992–1999. Cancer. 2005;103:538–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feinglass J, Rucker-Whitaker C, Lindquist L, et al. Racial differences in primary and repeat lower extremity amputation: results from a multihospital study. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:823–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Churak JM. Racial and ethnic disparities in renal transplantation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:153–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jha AK, Fisher ES, Li Z, et al. Racial trends in the use of major procedures among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milazzo AS Jr, Sanders SP, Armstrong BE, et al. Racial and geographic disparities in timing of bidirectional Glenn and Fontan stages of single-ventricle palliation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94:873–878. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez PC, Gauvreau K, Demone JA, et al. Regional racial and ethnic differences in mortality for congenital heart surgery in children may reflect unequal access to care. Pediatr Cardiol. 2003;24:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stern RE, Yueh B, Lewis C, et al. Recent epidemiology of pediatric cochlear implantation in the United States: disparity among children of different ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horstmann R, Tiwisina C, Classen C, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: which factors influence the decision between the surgical techniques? [in German]. Zentralbl Chir. 2005;130:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guller U, Hervey S, Purves H, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: outcomes comparison based on a large administrative database. Ann Surg. 2004;239:43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patterson ML, Stern S, Crawford PB, et al. Sociodemographic factors and obesity in preadolescent black and white girls: NHLBI’s Growth and Health Study. J Natl Med Assoc. 1997;89:594–600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, et al. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1728–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cowan JA Jr, Dimick JB, Thompson BG, et al. Surgeon volume as an indicator of outcomes after carotid endarterectomy: an effect independent of specialty practice and hospital volume. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:814–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dimick JB, Cowan JA Jr, Stanley JC, et al. Surgeon specialty and provider volumes are related to outcome of intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the United States. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:739–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mechanic D. Policy challenges in addressing racial disparities and improving population health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:335–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferris TG, Kuhlthau K, Ausiello J, et al. Are minority children the last to benefit from a new technology? Technology diffusion and inhaled corticosteroids for asthma. Med Care. 2006;44:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]