Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the methodologic quality of economic analyses of surgical procedures and to compare quality across publications.

Summary Background Data:

With healthcare resources limited and technologies rapidly advancing across specialties, including surgery, there is increasing demand for evidence of cost-effectiveness.

Methods:

A MEDLINE search identified English-language articles published from 1995 to 2004 that included economic analyses of surgical procedures. Two of the authors reviewed 110 studies and scored each based on compliance with 10 methodologic criteria. Data analyses used Cohen’s kappa statistic, regression models, Mann-Whitney U tests, and Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Results:

The 110 articles appeared in 79 different journals, including 57 articles in 37 surgical journals. Most journals (75%) had only 1 article eligible for inclusion. The average number of criteria met was 4.1, with 10 articles meeting all 10 methodologic standards. Compliance rates for the 5 methodologic criteria most frequently neglected ranged from 34% to 45% in nonsurgical journals and 9% to 14% in surgical journals (P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

While methodologic guidelines for cost-effectiveness analyses have appeared in the medical literature, studies of cost-effectiveness in surgery often do not meet these criteria. As healthcare policy seeks to incorporate information from economic evaluations, it is increasingly important that surgical journals adhere to accepted guidelines and perform quality assurance on these studies. This may be aided by wider promulgation of the methodologic criteria in surgical journals or at surgical meetings.

This study reviews recently published articles in medical journals to examine the methodology used in cost-effectiveness analyses. A total of 110 articles were evaluated by the authors on the basis of 10 criteria. They found that a majority of CEAs do not meet the guidelines set out in medical literature.

Medical care costs have increased steadily over the years, driven in part by the rapid development and expansion of medical technology. National healthcare spending growth in the United States has outpaced economic growth, with annual growth rates of more than 7% during the last several years. Projections indicate that by 2012, healthcare spending will comprise 17.7% of the gross domestic product, up from 14.1% in 2001.1 Insurance companies and businesses, in addition to the government and the public, have placed increasing pressure on the medical community to evaluate the economics surrounding newer technologies. Consequently, there has been rapid growth in the number of published economic analyses over the past several decades, primarily consisting of cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs).

Methodology for economic analyses appeared in the medical literature as early as the 1970s with further refinement over time.2–5 These methods are intended to reduce bias and improve the validity of economic analyses. However, these methodologic principles are used infrequently.6,7 There has been a call to standardize economic analysis methodology and for adherence to these principles in the medical literature.2,7,8 Two prior studies focusing on economic analyses of radiology procedures found that, in general, adherence to methodologic criteria was deficient, with an average of 4.7 of the 10 criteria addressed in articles from radiology journals and an average of 5.4 in articles from all medical journals.6

Research exists assessing the quality of cost-effectiveness in specialties, including gynecologic oncology,9 pharmacoeconomics,10 pediatrics,11 and nuclear medicine.12 These assessments, along with more generalized ones, systematically review studies to verify compliance with methodologic criteria. Studies used various scoring methods; however, many checked compliance with methodologic principles thought to represent the minimum standards for medical economic analysis. A number of task forces and panels have outlined these principles as guidelines for conducting and reporting CEAs.8,13,14 Methods used to assess compliance included a 13-item quality scoring checklist,10,15 utilization of instruments such as the Quality of Health Economic Studies,16 and the Pediatric Quality Appraisal Questionnaire.11 Most of the assessments determined that there were gaps in compliance with these criteria but that there had been some improvements over time.

Standards for economic analysis are essentially uniform across disciplines with no additional criteria specific to a given field. There are essential tenets to which any economic analysis should adhere as described in one of the earliest articles regarding CEAs for medical and health practices in the New England Journal of Medicine.5 Some journals contain guidelines for economic submissions specific to their publications: the British Medical Journal lists 35 criteria7 and the Journal of the American Medical Association similarly lists 38 suggestions.13 After a comprehensive review of medical and health economic analyses, we selected 10 principles that should be addressed in any cost-effectiveness or cost-benefit analysis similar to those listed in other studies of economic analyses.6,9,17 The goal of this study was to evaluate the methodologic quality of economic analyses of surgical procedures based on the methodologic criteria that we identified, which are clearly presented by Blackmore and Smith,6 and to determine how such analyses might be improved.

METHODS

We used MEDLINE searches for the years 1995 to 2004 to identify articles that included economic analyses of surgical procedures. We performed searches with 2 criteria: performance of an economic analysis and evaluation of a surgical procedure. We identified surgery articles using the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms “surgery,” “colorectal surgery,” “plastic surgery,” “thoracic surgery,” and “laser surgery.” We identified economic articles with the MeSH terms “cost-effectiveness” or “cost-benefit analysis.”

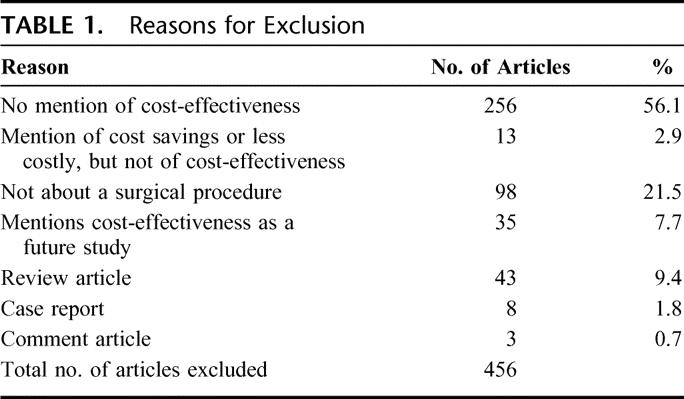

We combined the 2 searches and limited them to studies including adults older than 19 years of age and articles printed in the English language. The preliminary search resulted in 566 articles. We then excluded letters, case reports, review articles, editorials, comment articles, and technical descriptions (Table 1). We also excluded articles that concentrated on cost minimization but did not mention cost-effectiveness or cost-benefit. In addition, articles that mentioned cost-effectiveness as a future study and articles not about surgical procedures were not included in the study.

TABLE 1. Reasons for Exclusion

Two of the authors (L.K., J.E.K.) independently reviewed each article and scored for compliance with the methodologic criteria. We classified each journal as surgical or nonsurgical based on surgical journals identified by MedBioWorld (https://www.medbioworld.com/). We also noted the impact factor for each journal, as reported by the Institute for Scientific Information. Journals were classified by impact as low impact (impact factors <1.0), medium impact (impact factors between 1.0 and 3.0), or high impact (impact factors >3.0). We used Cohen’s kappa statistic to measure the agreement between the reviewers and arrived at final scores used for analysis by consensus. We used the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test to assess differences between groups, and we explored trends in numbers of publications over time with simple linear regression (SPSS for Windows, version 12.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

We assessed the 10 methodologic principles previously presented by Blackmore and Smith.6 We elected to use these principles after a comprehensive review of economic analysis methodology guidelines. We agreed that the outlined principles represented the minimum standards for any medical economic analysis and elected to use them rather than developing a different system. They are similar to guidelines used in several other publications.8–9,14

Description of Comparative Options

Assessment of cost-effectiveness is a comparative exercise. Alternative interventions must be included before reaching any conclusion about the cost-effectiveness of a procedure. We considered a study compliant if it included some description of alternative interventions considered by the analysis.

Statement of Perspective of Analysis

The costs and benefits, or outcomes, of an intervention are different depending on the perspective of the study. For example, the cost to a patient for a dermatologic skin evaluation for skin cancer may include the time missed from work for the appointment if the screening program is a community service, or it might include the portion of cost not covered by insurance. The cost from the provider’s perspective would be the direct medical costs of the examination itself, as well as other potential costs such as biopsies and the costs of treating any persons found to have skin cancer. Depending on which perspective is presented, the cost-effectiveness may be quite different; therefore, it is important that the perspective be explicitly stated in an analysis. We considered a study compliant if it included a statement defining the perspective of the analysis, regardless of appropriateness of the perspective.

Outcome Measure Defined

Common outcome measures in economic analyses include lives saved, deaths prevented, or quality-adjusted life-years gained. We considered a study compliant if it included any measure that describing the impact of the intervention on patient outcomes.

Cost Data Provided

An economic analysis must have included a measure of monetary cost. For this criterion, we accepted any definition of monetary cost of the intervention under evaluation.

Source of Cost Data Provided

Cost most correctly implies direct medical costs, but it may also refer to reimbursements or charges. These data may come from specific cost-accounting exercises or from estimates of average cost or assigned reimbursement. Compliance with this criterion required an explicit statement of the source for included cost data.

Inclusion of Long-term Costs

For some surgical procedures, the total cost includes long-term as well as short-term costs. For instance, restenosis soon after angioplasty might require several repeat angioplasties in the future or a mitral valve replacement may require years of anticoagulation therapy and monitoring. To meet this criterion, studies had to either include long-term costs or contain an explicit statement as to why they excluded long-term costs.

Discounting Used

To adjust for the effect of time, any future value must be discounted. This is particularly important when costs occur at any time outside the study period. Compliance with this criterion required either the discounting of future costs or an explanation of why discounting was not used.

Inclusion of Summary Measure

A summary measure represents the value of an intervention by combining the cost and benefit into a single ratio. When an intervention is both more effective and less costly, it is a “dominant strategy;” however, most interventions result in improvements in health status at extra cost. For this criterion, we accepted the representation of any cost-effectiveness ratio, net monetary benefit calculation, or identification of a dominant strategy.

Incremental Computation of Summary Measure

In CEA, summary ratios for one intervention must be compared with the ratios of other interventions. Incremental cost-effectiveness represents the additional cost and effectiveness obtained by comparing one option to another. This is usually calculated as the difference between the cost of each strategy divided by the difference in effectiveness of the 2 strategies, resulting in the incremental or marginal cost of an intervention (the extra units of outcome per extra dollar spent). For example, although a new surgical procedure might improve a patient’s quality of life, when that procedure is compared with the standard one, the additional benefit obtained may be quite small when compared with the added cost of the new intervention. For a study to meet this comparison, it had to include incremental analysis of cost-effectiveness.

Sensitivity Analysis Performed

The estimates of costs and benefits of health interventions are rarely known with certainty. These estimates come from the published literature, expert opinions, or from defined measurements. To deal with the uncertainty, sensitivity analysis allows testing the stability of a result.18 Sensitivity analyses vary each assumption or estimate over a range of reasonable values. If the basic results or conclusions do not change, confidence in the conclusion is increased. Compliance with this criterion required varying the key assumptions in the analysis and reporting impact on the results.

RESULTS

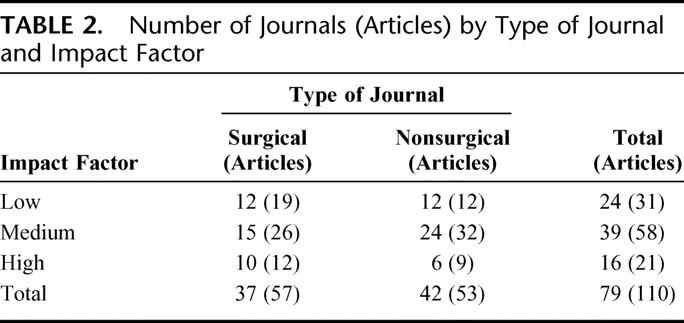

A total of 110 articles met the inclusion criteria and then received formal methodologic review. A bibliography of these articles is available from the authors upon request. There were 79 different journals represented in this study, 37 of which were surgical journals. Fifty-seven of the 110 articles appeared in surgical journals (Table 2). Most journals (75%) had only 1 article that met the eligibility criteria. There was some variation in the number of articles that met eligibility criteria each year. There were no articles in 1995 or in 2004 that were eligible. The greatest number of articles that met eligibility criteria17 appeared in both 1997 and 2002. Despite these variations, there was no statistically significant change in the number of economic analyses of surgical procedures over the study period (P = 0.79).

TABLE 2. Number of Journals (Articles) by Type of Journal and Impact Factor

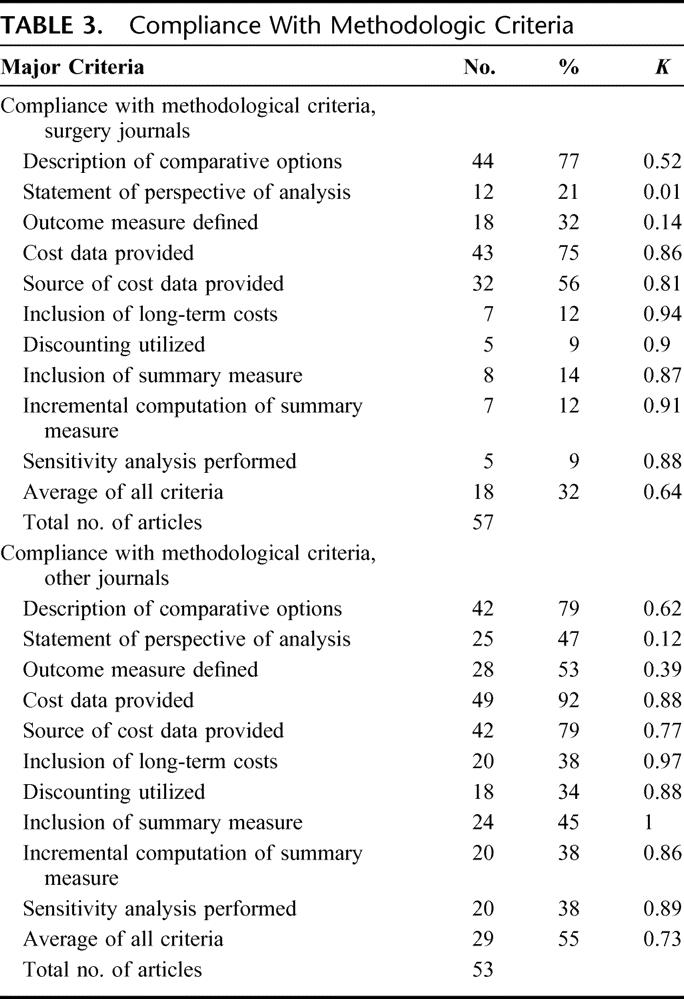

The mean number of criteria met by all 110 articles was 4.1 out of the possible 10. There was a difference between the mean criteria met in surgical journals compared with nonsurgical journals (3.0 vs. 5.3, P < 0.001). The range of compliance with the individual criteria within surgical journals was as high as 77% and as low as 9% (Table 3). In nonsurgical journals, the overall range was higher, but less wide, with the highest compliance at 92% and the lowest at 34%. Overall agreement between abstracters for all criteria within the surgical journals was 32% with kappa = 0.64 (range, 0.01–0.94). Overall agreement for all criteria within nonsurgical journals was higher at 55% with kappa = 0.73 (range, 0.12–1.0). There was evidence of significant deficits in the quality of analysis in most economic evaluations, particularly in the surgical journals. The 5 methodologic criteria most frequently neglected had a compliance ranging from 34% to 45% in nonsurgical journals, but in surgical journals that compliance was much lower, ranging from 9% to 14% (P < 0.001).

TABLE 3. Compliance With Methodologic Criteria

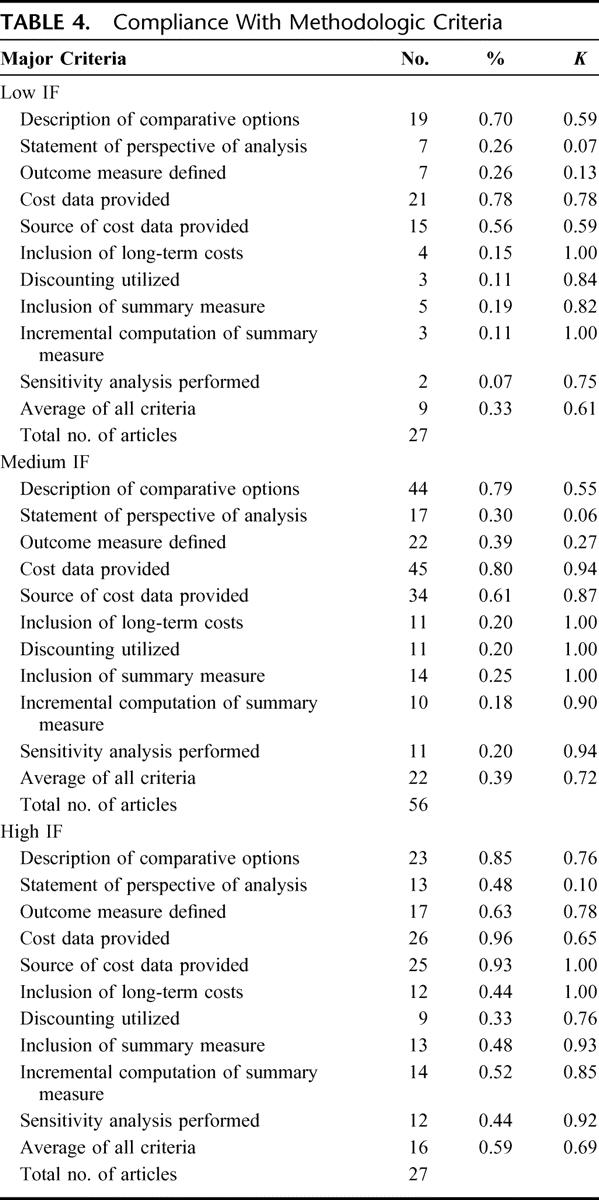

There were also differences in meeting criteria across impact factor categories. Articles in high impact factor journals fulfilled more criteria than those in journals with low or medium impact factors (5.70 vs. 3.26 vs. 3.75, P > 0.01). Compliance with the individual criteria was higher in the high impact factor journals as well, ranging from 33% to 96% (Table 4). Journals with low impact factors had the lowest compliance with the individual criteria (7%–78%), which was similar to the range of compliance within surgical journals. The overall agreement between abstracters for all criteria within the low impact factor journals was 33% with kappa = 0.61 (range, 0.07–1.00). Overall agreement for all criteria within medium impact factor journals was slightly higher at 39% with kappa = 0.72 (range, 0.06–1.00) and was highest for high impact factor journals at 59% with kappa = 0.69 (range, 0.10–1.00). The same 5 methodologic criteria most frequently neglected in the surgical journals also had low compliance among the low and medium impact factor journals, ranging from 7% to 19% in the low impact factor journals and 18% to 25% in the medium impact factor journals. However, in the high impact factor journals, the compliance was much greater, ranging from 33% to 52% (P < 0.01).

TABLE 4. Compliance With Methodologic Criteria

Ten articles from 10 different journals met all 10 methodologic standards. Two of these articles were from surgical journals. Since none of the journals had more than 1 article meeting all 10 criteria, it was not possible to determine whether a particular journal had a higher compliance to methodologic criteria than other journals. Nor was it possible to perform any subgroup analyses on any of the journals due to the low number of articles from any single journal.

DISCUSSION

Our review indicates that published economic evaluations of surgical procedures in general do not follow accepted methodologic standards, with less than half of the basic principles met by any given analysis. A comparison of nonsurgical versus surgical journals demonstrated a significant difference in compliance with methodologic criteria, with much lower compliance in surgical journals. The average proportion of criteria met in the nonsurgical journals was slightly more than half, whereas in the surgery journals it was less than one third. The surgical journals were also consistently lower in compliance with each individual criterion as compared with the nonsurgical journals, with 5 criteria failing to reach 20% compliance.

Compliance in journals with low and medium impact factors was lower than in journals with high impact factors. The low and medium impact factor journals were similar to the surgical journals in terms of average criteria met and overall compliance. Finally, of 10 articles that met all 10 criteria, only 2 were from surgical journals. This calls attention to the fact that CEAs of surgical procedures and interventions could be significantly improved, particularly those published in surgical journals. Other reports have shown that published economic evaluations fall short of adhering to basic methodologic criteria,6,17,19 with a lower quality in evaluations published in specialty journals.2

Over the past 2 decades, the availability and use of economic evaluations has increased, making this a dynamic and evolving field.20 In the current healthcare environment, decisions regarding the allocation of healthcare resources rely in part on cost-effectiveness information, with economic evaluations used increasingly as tools in decision-making. These economic tools can improve physicians’ choices regarding the use of individual and societal resources for clinical interventions with the ultimate goal of improving health. Technologic advances in surgical procedures provide more options for patients but frequently at an increased cost. New or existing diagnostic and treatment therapies must show improved healthcare outcomes in addition to clinical utility for the increased cost to be acceptable. If we attempt to base medical decisions on health and monetary considerations, it is important to have reliable information. However, the value of economic analysis is compromised if quality is poor.

We found that “cost-effective” is a term frequently used with no documentation of relevant cost and outcome data, a misuse of terminology that was commented on over 2 decades ago.7 Some authors have advocated that “cost-effective” should apply only when a procedure/intervention has an additional benefit that is worth the additional cost.5,7 In general, a strategy is cost-effective if it is less costly and has an equal or better outcome than an alternative therapy, or if it is more effective and more costly with the added benefit worth the extra cost.

If the results of CEAs are to be valid and generalizable, the models and assumptions behind these evaluations have to be reliable. Several studies have shown confusion in the design, description, and interpretation of economic evaluations, with wide variability in reporting.2,6,17,19 The relatively low kappa values reported in this study point toward a need for improved clarity in the reporting and writing of economic evaluations. Several consensus panels and task forces have convened over time to improve accurate reporting of economic evaluations.8,13,14 However, few medical journals have guides for CEAs or use peer reviews of economic evaluations for quality control.8,19 Not only should authors who are conducting economic evaluations be familiar with basic methodologic criteria, but so should journal reviewers. Likewise, readers need to be familiar with the methodologic principles to be able to interpret accurately the results of CEAs.

There were several limitations to our study. Our search technique relied on MeSH key words and terms, which may not have been comprehensive. We think that all surgical fields such as trauma, transplant, or oncology were included in the general term “surgery.” The 2 reviewers were not blinded to journal authors, titles, or years of publication. However, we applied the basic methodologic standards systematically to each article and designed them to be objective avoiding potential bias. Additionally, none of the authors had any involvement with the articles reviewed. There was lack of agreement between the 2 reviewers particularly regarding the criteria “perspective” and “outcome data.” We think that a significant proportion of the lack of agreement was due to the unclear writing in many of the studies. Since one reader is an epidemiologist/health services researcher and the other a physician, there may have been differences in “reading between the lines” when the writing was unclear. To address this issue, we resolved all discrepancies in scoring by consensus to determine a final result.

Our study evaluated each article for adherence to 10 basic methodologic principles rather than adherence to a more rigorous checklist including reporting of model assumptions, methods for obtaining estimates, and critiques of data quality. Yet we think that these 10 principles should be the very minimum to be addressed in each CEA. If authors thought a given principle was not appropriate to their analysis, such as the inclusion of long-term costs or discounting for a paper focused on short-term analysis, we required an explicit statement within the article stating that the principle did not apply. Articles received full marks if authors either incorporated or addressed all 10 principles. Adherence to these criteria does not imply that an analysis is sufficient to be used in policy or decision-making.

To defend the use of surgical interventions and treatment strategies in an environment that is becoming progressively more cost-conscious, it is of increasing importance to have quality data. There needs to be an increased awareness of methodologic standards of those performing analyses in surgical areas so that the quality of surgical economic evaluations can improve, especially those within surgical journals. Wider promulgation of the methodologic criteria in surgical journals or at surgical meetings may significantly improve the quality of economic analysis published in surgical journals or concerning surgical interventions.

Footnotes

Reprints: Seema S. Sonnad, PhD, Department of Surgery, University of Pennsylvania, 4 Silverman, 3400 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104. E-mail: seema.sonnad@uphs.upenn.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heffler S, Smith S, Keehan MK, et al. Health care spending projections for 2002–2012. Health Aff. 2003;(suppl Web Exclusives):W3:54–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Jefferson T, Demicheli V, Vale L. Quality of systematic reviews of economic evaluations in health care. JAMA. 2002;287:2809–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Detsky AS, Naglie GM. A clinician’s guide to cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberg JM. Clinical economics: a guide to the economic analysis of clinical practices. JAMA. 1989;262:2879–2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein MC, Stason WB. Foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis for health and medical practices. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:716–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackmore CC, Smith WJ. Economic analyses of radiological procedures: a methodological evaluation of the medical literature. Eur J Radiol. 1998;27:123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doubilet P, Weinstein MC, McNeil BJ. Use and misuse of the term ‘cost effective’ in medicine. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:253–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drummond MF, Jefferson TO. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to BMJ. BMJ. 1996;13:275–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manuel MR, Chen LM, Caughey AB, et al. Cost-effectiveness analyses in gynecologic oncology: methodological quality and trends. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iskedjian M, Trakas K, Bradley CA, et al. Quality assessment of economic evaluations published in PharmacoEconomics: the first four years (1992 to 1995). PharmacoEconomics. 1997;12:685–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ungar WJ, Santos MT. Quality appraisal of pediatric health economic evaluations. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gambhir SS, Schwimmer J. Economic evaluation studies in nuclear medicine: a methodological review of the literature. Q J Nucl Med. 2000;44:121–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel JE, Weinstein MC, Russell LB, et al. Recommendations for reporting cost-effectiveness analyses. JAMA. 1996;276:1339–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anonymous. Economic analysis of health care technology: a report on principles. Task Force on Principles for Economic Analysis of Health Care Technology. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:61–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Bradley CA, Iskedjian M, Lanctot KL, et al. Quality assessment of economic evaluations in selected pharmacy, medical, and health economic journals. Ann Pharmacother. 1995;29:681–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ofman JJ, Sulivan SD, Neumann PJ, et al. Examining the value and quality of health economic analyses: implications of utilizing the QHES. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9:53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subak LL, Leslee L, Caughey AB. Measuring cost-effectiveness of surgical procedures: a critique of new gynecologic surgical procedures. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;43:551–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sox HC Jr, Blatt MA, Higgins MC, et al. Medical Decision Making. Boston: Butterworths, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann PJ, Stone PW, Chapman RH, et al. The quality of reporting in published cost-utility analyses, 1976–1997. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:964–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonnad SS, Greenberg D, Rosen AB, et al. Diffusion of published cost-utility analyses in the field of health policy and practice. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]