Abstract

Intact human pregnancy can be regarded as an immunological paradox in that the maternal immune system accepts the allogeneic embryo without general immunosuppression. Because dendritic cell (DC) subsets could be involved in peripheral tolerance, the uterine mucosa (decidua) was investigated for DC populations. Here we describe the detailed immunohistochemical and functional characterization of HLA-DR-positive antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in early pregnancy decidua. In contrast to classical macrophages and CD83+ DCs, which were found in comparable numbers in decidua and nonpregnant endometrium, only decidua harbored a significant population of HLA-DR+/DC-SIGN+ APCs further phenotyped as CD14+/CD4+/CD68+/−/CD83−/CD25−. These cells exhibited a remarkable proliferation rate (9.2 to 9.8% of all CD209+ cells) by double staining with Ki67 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Unique within the DC-family, the majority of DC-SIGN+ decidual APCs were observed in situ to have intimate contact with CD56+/CD16−/ICAM-3+ decidual natural killer cells, another pregnancy-restricted cell population. In vitro, freshly isolated CD14+/DC-SIGN+ decidual cells efficiently took up antigen, but could not stimulate naive allogeneic T cells at all. Treatment with an inflammatory cytokine cocktail resulted in down-regulation of antigen uptake capacity and evolving capacity to effectively stimulate resting T cells. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis confirmed the maturation of CD14+/DC-SIGN+ decidual cells into CD25+/CD83+ mature DCs. In summary, this is the first identification of a uterine immature DC population expressing DC-SIGN, that appears only in pregnancy-associated tissue, has a high proliferation rate, and a conspicuous association with a natural killer subset.

In successful human pregnancy, the balance between active immunity and tolerance at the site of contact between mother and child, which is the decidua, is of critical importance. Although it is essential that effective immunity is maintained to protect the mother from invasion by harmful pathogens, it is of utmost importance that no immune response is mounted against fetal antigens. The way in which fetal antigens are processed and presented to T cells is likely to be one of the critical factors in determining how the decidual immune system handles foreign antigens. Like other mucosal surfaces, the decidua is seeded with a large population of HLA-DR+ antigen-presenting cells (APCs) including a subset of mature CD83+ dendritic cells (DCs) recently described by us. 1

DCs are a heterogeneous population of bone marrow-derived cells present at minute numbers scattered all over the body, yet are the most potent of APCs. 2 In tissues, immature DCs function as sentinels of the immune system. 3 DCs take up antigens and process them into peptides that are presented in the context of MHC class I and class II molecules as ligands for antigen-specific T-cell receptors. 4 The expression of additional co-stimulatory and adhesion molecules is essential for the activation of naive T cells by DCs. 5 In addition to their significant stimulatory capacity, DCs have an important regulatory role. In particular, DCs exhibit considerable plasticity in their ability to skew Th responses. There is evidence that DCs can be converted to Th2-skewing cells when treated with anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-10 6,7 or dexamethasone. 8 In the mouse and rat model, DCs isolated from Peyer’s patches in the gut elicit Th2 responses, 9,10 whereas those from spleen induce Th1 responses. 11 There is further evidence that DCs in mucosal surfaces of the intestine are responsible for oral tolerance of antigens. 12 This may reflect a special tolerance-inducing DC subpopulation associated with mucosal surfaces. Thus, such a population could be responsible for maternal tolerance against fetal antigens in the mucosal decidua.

Recently, a novel DC-specific adhesion receptor DC-SIGN (dendritic cell-specific ICAM-grabbing nonintegrin, classified as CD209) has been identified that binds with high affinity to ICAM-2 and ICAM-3. 13,14 In vivo, DC-SIGN is expressed by immature DCs in peripheral tissue as well as mature DCs in lymphoid tissues. 15 Originally this type II mannose-binding C-type lectin DC-SIGN was cloned from a placenta library through its capacity to bind to the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. 16 Herein, we report that in contrast to normal endometrium a huge subpopulation of APCs in the decidua express DC-SIGN. These cells are found in situ in close contact to decidual large granular lymphocytes (LGLs) and exhibit a high proliferative activity. Directly after isolation, DC-SIGN+ APCs show functional features of immature DCs, but can be efficiently matured to potent immunostimulatory CD83+/CD25+ DCs.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Specimens

All investigations were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Würzburg, Germany, all patients gave informed consent for tissue collection.

Decidual tissue (decidua basalis and parietalis) was obtained from 15 healthy women undergoing legal therapeutic abortion of an intact, normally progressing pregnancy with documented fetal heart activity at weeks 7 to 8 of gestation after the last menstrual period. All specimens contained embryonic components as verified by macroscopic and histological examination. Decidual tissue was taken from each specimen to be snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for histological examination and immunohistochemical staining. The remainder was kept for no more than 30 minutes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before subsequent cell isolation. Endometrial tissues from 17 women at fertile age undergoing hysterectomy because of uterus myomatosus and placental bed biopsies from 10 women during caesarian section at term were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

The antibodies applied in this study are listed in Table 1 ▶ . Serial frozen sections of decidua, endometrium, and placental bed biopsies were cut at 5 μm and placed onto APES (3-amino-propyltriethoxy-silane; Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany)-coated slides, air-dried overnight, fixed in acetone for 10 minutes, and rehydrated in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 25 mmol/L Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 137 mmol/L NaCl, 2.7 mmol/L KCl). In proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) staining, sections were immediately (without drying) transferred into a methanol solution, fixed in 4% buffered formalin, and rehydrated in Tris-buffered saline (5 minutes each) before double stainings. For double/triple-immunohistochemical staining procedures of different cells or proliferating cells, respectively, sections were incubated with two to three cycles of: first, the monoclonal antibody at appropriate dilutions; second, the horseradish-peroxidase-labeled rabbit anti-mouse-specific secondary antibody (dilution 1:100; DAKO, Hamburg, Germany); and third, the detection reaction followed by 10 minutes of air-drying. The first detection reaction was developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), the second with the Vector VIP peroxidase substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and the third with Vector SG substrate kit (Vector Laboratories) or HistoGreen substrate kit (Linaris, Wertheim, Germany), respectively. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (Sigma) or not.

Table 1.

Antibodies Used for Immunohistochemistry

| Antigen | Clone | Isotype | Major specificity | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 | RPA-T4 | IgG1 | Helper/inducer T cells, monocyte subsets | Pharmingen |

| CD14 | UCHM1 | IgG2a | Monocytes, macrophages, granulocytes | Serotec |

| CD34 | QBEnd 10 | IgG1 | Capillaries, endothelial cells | Cymbus Biotech. |

| CD56 | NCAM16.2 | IgG2b | Natural killer-cells, T-cell subsets | Becton Dickinson |

| CD68 | KP 1 | IgG1 | Macrophages, activated platelets | DAKO |

| CD83 | HB15A | IgG2b | Mature DCs | Immunotech |

| DC-SIGN | AZ1-D1 | IgG1 | DC-SIGN, DC-specific ICAM-3 receptor, does not detect L-SIGN/DC-SIGN-R | Geijtenbeek et al. |

| HLA-DR | DDII | IgG1 | Monocytes, macrophages, DCs, B lymphocytes | Dianova |

| Ki-67 | MIB-1 | IgG1 | Ki67 antigen | DAKO |

| PCNA | PC10 | IgG2a | Proliferating nuclear antigen | DAKO |

For blue-red double-immunohistochemical staining of co-localized antigens, sections were first incubated with the DC-SIGN-specific monoclonal antibody at appropriate dilution followed by biotin-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (dilution 1:100, DAKO) and then alkaline phosphatase-labeled streptavidin (dilution 1:300, Sigma) for 30 minutes each. Second the sections were incubated with the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled specific antibody against the antigen of interest, followed by incubation of the peroxidase-labeled rabbit anti-FITC antibody (DAKO). Before substrate application, endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity was blocked with 0.1% levamisole (Sigma) in TBS, pH 8.2. As substrates for the enzymes, first the alkaline phosphatase-detecting APIII-Kit (blue, Vector Laboratories) and then the horseradish peroxidase-specific AEC+ (red, DAKO) were applied. Sections were not counterstained and were embedded in aqueous mounting media (Aquatex, Sigma).

For purple-green immunohistochemical staining of co-localized antigens, the DC-SIGN antibody was detected by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-labeled rabbit anti-mouse-specific secondary antibody (DAKO) and the detection reaction (very short incubation time) with the Vector VIP (Vector Laboratories). After blocking with mouse-IgG, remaining horseradish peroxidase activity was blocked by 10 minutes of air-drying. Second the sections were incubated with the FITC-labeled specific antibody against the antigen of interest, followed by incubation of the peroxidase-labeled rabbit anti-FITC antibody. Second detection reaction was performed with the HistoGreen substrate kit.

To evaluate the average density value of APCs in human first pregnancy decidua and endometrium, DC-SIGN+, CD14+, CD68+, and CD83+ cells were counted at the 100-fold magnification in 30 single fields of 1.008 mm2 (=30.24 mm2) for each of two sections per patient per antibody by two independent observers in 11 decidual and 17 endometrial samples. Fields were randomly selected over the entire cryosection and completely filled with nonnecrotic cells.

Single Cell Isolation

For isolation of decidual cells in 10 cases, specimens were dissected free of products of conception and washed twice in PBS. The total decidual tissue (4 to 10 g) was then minced into fragments of ∼1 mm3 and digested for 20 minutes at 37°C under slight agitation in PBS with 200 U/ml of hyaluronidase (Sigma), 1 mg/ml collagenase type IV (Seromed, Berlin, Germany), 0.2 mg/ml DNase I (2500 Kunitz U/mg, Sigma), and 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin/fraction V (Sigma). The cell suspension obtained was filtered through sterile stainless steel 50-μm wire mesh and washed once in PBS. The mononuclear cell population was then separated by centrifugation over a Histopaque-1077 density gradient (Sigma), washed twice in PBS, and used immediately for subsequent cell isolation or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis.

For positive selection of CD14+ cells the cells were labeled with anti-CD14 Microbeads (clone Leu-M3; Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions in PBS supplemented with 10% human immunoglobulin (PBS/IgG, Beriglobin; Centeon, Marburg, Germany) and separated in a positive selection column in a magnetic cell separator (Vario-MACS, Miltenyi).

The positive CD14-enriched fraction containing decidual DCs was analyzed by flow cytometry and used for subsequent analysis in a primary mixed leukocyte reaction or antigen uptake experiments or maturation experiments, respectively.

Cell Labeling and FACS

Flow cytometry of CD14-enriched decidual cells was performed with the monoclonal DC-SIGN (AZN-D1) antibody, with isotype control (mixture of mouse IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b; all from Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany) and with the following primary antibodies directly labeled with FITC: HLA-DR (TU36; Caltag, Hamburg, Germany), CD14 (UHCM1; Cymbus/Chemicon, Hofheim, Germany), CD25 (M-A251, Pharmingen), CD68 (Ki-M7, Caltag), and CD83 (HB15a, Caltag). All incubation steps were followed by a wash in cold PBS/0.1% fetal calf serum. In brief, aliquots of 2 to 5 × 105 isolated cells were resuspended in 20 μl of PBS/IgG. First, the DC-SIGN antibody (1:100) was added and incubated for 30 minutes on ice. After one wash, phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL) was incubated for another 15 minutes. After washing, unspecific Fc binding was then blocked with mouse IgG followed by a wash step. FITC-labeled antibodies (10 μl each) were added to the cell suspension and the preparation was then incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. CD68 was stained intracellularly using the Fix and Perm kit (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ICAM-3 staining on LGLs was performed following the above procedure but with CD14-depleted decidual cells stained for ICAM-3 (clone 186-269, T. Geijtenbeek) followed by PE-anti-mouse and CD56/FITC (NCAM16.2, Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). Cell suspensions were washed once, resuspended in 200 μl of PBS, and then analyzed in a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson). A total of 20,000 cells per sample were evaluated for specific staining. Results were analyzed using the WinMDI-software (Version 2.8, Joseph Trotter).

Generation and Maturation of Monocyte-Derived DCs (MoDCs)

For control purposes, DCs were generated from blood monocytes following standard procedures 17 in four cases. In brief, peripheral blood mononuclear cells derived from buffy coats of healthy volunteer donors were prepared by isolation over a Histopaque-1077 density gradient. After depletion of T cells with neuraminidase treated sheep erythrocytes (rosetting), the remaining non-T cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Seromed) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (PAN Biotech GmbH, Aidenbach, Germany) and 50 μg/ml of gentamicin (Seromed) (R10) and incubated at 5 × 106 cells/ml in a tissue-grade Petri dish to allow monocytes to adhere to the bottom. The nonadherent cells were removed after 1 hour. The adherent fraction was then cultured in R10/IL-4/GM that is R10 supplemented with GM-CSF (1000 U/ml; Sandoz, Basel, Switzerland) and IL-4 (800 U/ml; Strathmann Biotec AG, Hamburg, Germany) for 7 days. Half the volume of medium was replaced with fresh R10/GM-CSF/IL-4 at days 3 and 5. For mature MoDC culture, at day 7 in half of the culture dishes, half the volume of medium was replaced by fresh R10 supplemented with maturation cocktail to a final concentration of: IL-1β (1000 U/ml; Strathmann), tumor necrosis factor-α (1000 μ/mL; Strathmann), IL-6 (1000 μ/mL; Strathmann) and PGE2 (E2, 10−8 mol/L; Calbiochem-Novabiochem GmbH, Bad Soden, Germany). The remaining half of culture dishes was fed with R10/IL-4/GM without cocktail, resulting in immature MoDCs. At day 10 of culture, nonadherent cells with typical appearance of DCs were collected, and used in the mixed leukocyte reaction (only mature DCs) and antigen uptake experiments. FACS analysis confirmed cocktail-matured MoDCs to express HLA-DR in 85.7 ± 7.8% SD and CD83 in 67.8 ± 9.8% SD.

Analysis of Antigen Uptake

Antigen uptake was determined by incubating 1 × 105 cells with different amounts of FITC-conjugated chicken OVA/FITC (Isomer I and OVA protein, conjugated as previously described; 18 Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) for 1 hour at 37°C in R10. Incubated cells were washed extensively with ice-cold PBS, stained with PE-conjugated HLA-DR on ice, and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Control incubation was performed at 4°C. Dead cells and cell debris were excluded by propidium iodide labeling and forward and side scatter gating.

Mixed Leukocyte Reaction

Different amounts of decidual APCs (dAPCs) or MoDCs were co-cultured in triplicates for 5 days at 37°C in 5% CO2 with 9 × 104 allogeneic T lymphocytes (prepared by 0.8% NH4Cl lysis of neuraminidase-treated sheep red blood cell rosettes of peripheral blood mononuclear cells) in a final volume of 200 μl of R10 in round bottom 96-well plates (Falcon/Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). During the final 16 hours of co-culture, 1 μCi of [3H] thymidine (Amersham International, Arlington Heights, IL) per well was added and incorporated radioactivity was determined.

Results

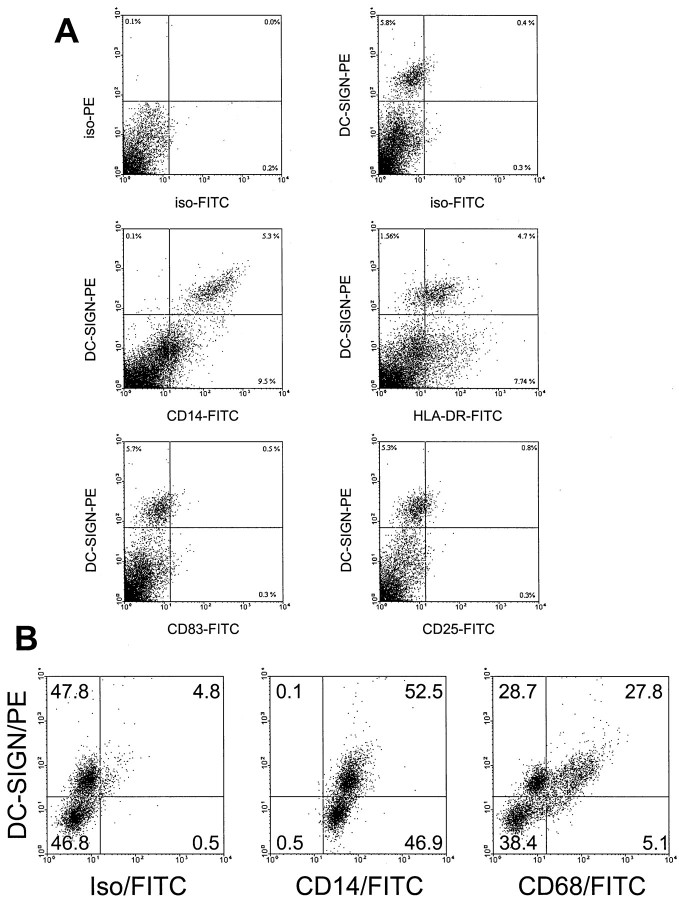

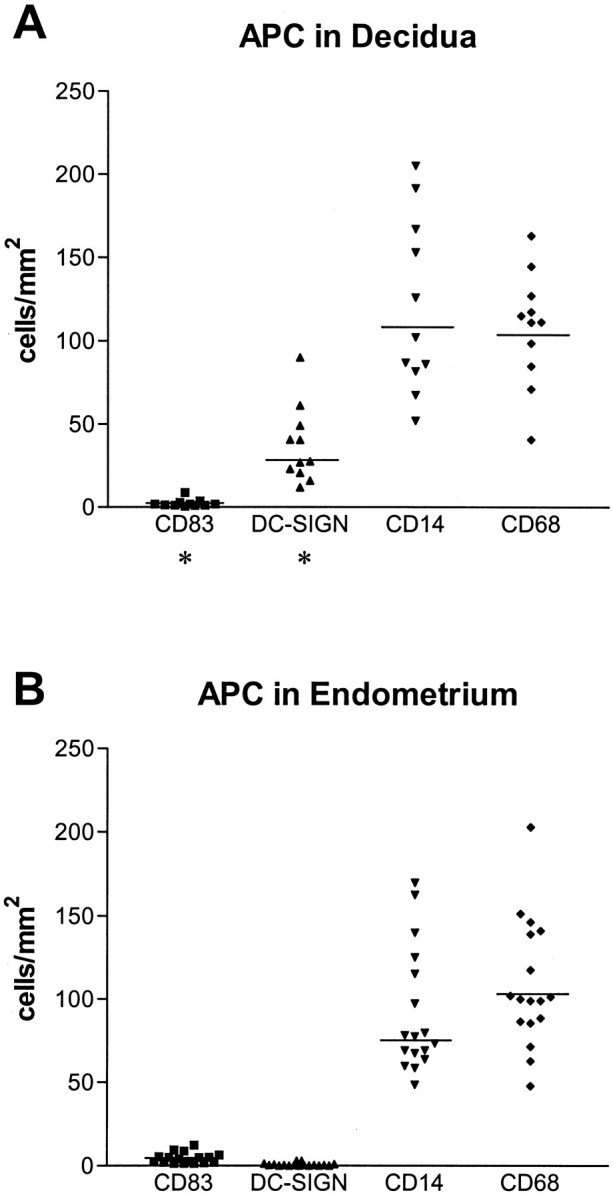

Decidua but Not Endometrium Contains DC-SIGN-Positive Cells

To quantify the cellular expression of monocyte/DC markers within endometrial and decidual tissue, morphometric analysis of immunohistochemically stained sections were performed. As shown in Figure 1 ▶ similar numbers of CD14 (91.46 ± 36.3 SD cells/mm2 in endometrium, 119.9 ± 52 SD CD14+ cells/mm2 in decidua)- and CD68 (108.2 ± 38 SD in endometrium, 107.6 ± 34 SD in decidua)-positive cells were found. Interestingly, a significantly higher amount of CD83+ cells was found in the endometrium (4.5 ± 3.2 SD compared to 2.4 ± 2.3 SD in decidua; P = 0.02. To our surprise, hardly any DC-SIGN+ cells were found in endometrium (0.7 ± 0.9 SD cells/mm2). However, in decidua, a remarkably large population of DC-SIGN+ cells was seen (36.9 ± 23 SD cells/mm2, P < 0.01, compared to endometrium). The overall number CD14+, CD68+, CD83+, and DC-SIGN+ cells did not change relative to the week of gestation in decidua and to the cyclic phase in endometrium (data not shown). The DC-SIGN+ cells were still found in high numbers in decidua of placental bed biopsies at term, indicating them to be stable in population during the whole pregnancy phase (not shown).

Figure 1.

Scatterplots of the density value of APCs in human first pregnancy decidua (A) and endometrium (B). Compared to endometrium the decidua contained significantly (P = 0.02) less CD83+ cells. Hardly any DC-SIGN+ cell was found in endometrium, whereas decidua displayed a remarkable population (P < 0.01). Bar, median of the columns; *, significant difference between endometrium and decidua.

Phenotypical Characterization of Decidual APCs in Situ

DC-SIGN+ Decidual Cells Exhibit the in Situ Phenotype HLA-DR+/CD14+/CD68(+/−)/CD4+/CD83−

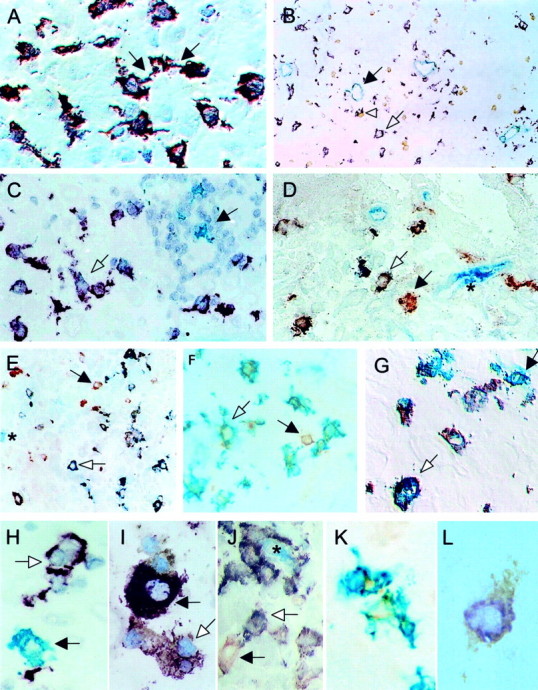

Immunohistochemistry staining on cryostatic sections of decidual tissue revealed DC-SIGN+ cells to exhibit a veiled shape with long, irregular dendritic protrusions (Figure 2A) ▶ and to be regularly scattered through the tissue, with a preference for the areas with clear visible spiral arteries (Figure 2B) ▶ . DC-SIGN+ cells could be clearly distinguished from mature DCs and were never found to be positive for CD83 (Figure 2, C and H) ▶ .

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemistry of decidual APCs in early human pregnancy. Violet, Vector VIP; brown, DAB; gray-blue, Vector SG; green, HistoGreen; red, AEC; blue, Vector APIII. A: DC-SIGN+ cells in decidua exhibit a DC-like veiled appearance with long dendrites extending into the surrounding tissue and connecting themselves in a network-like matter (violet, black arrows). B: Typical location of DC-SIGN+ cells (violet, white arrow) was in areas with spiral arteries (blue-gray, black arrow), but cells were also scattered throughout the tissue. DC-SIGN+ cells could often be seen in intimate contact to CD56+ LGLs (brown, white arrowhead). C: DC-SIGN+ cells (violet, white arrow) could be clearly distinguished by size and morphology from mature CD83+ DC (green, black arrow) that principally formed clusters with numerous lymphocytes. D: Co-staining of HLA-DR (red) and DC-SIGN+ (blue) demonstrated all DC-SIGN+ cells to express HLA-DR (purple, white arrow); single HLA-DR-positive cells were seen next to the double-positive cells (black arrow). Endogenous phosphatase activity stains vessels blue (*). E: Double staining with CD14 (red) revealed all DC-SIGN+ cells to express CD14+ (purple, white arrow); few CD14+ but DC-SIGN− cells could also be found (red, black arrow). F: All DC-SIGN+ cells co-stained with CD4 (green/brown, white arrow) next to a single CD4+ T cell (brown, black arrow). G: A high percentage of DC-SIGN+ cells (violet, white arrow) co-stained with CD68 (green) next to some single green-stained CD68+ macrophages (green, black arrow). H: DC-SIGN+ (violet, white arrow) and CD83+ DC (green, black arrow). I: HLA-DR+/DC-SIGN+ cells (violet/brown, white arrow) next to a HLA-DR+/DC-SIGN− cell (violet, black arrow). J: CD14+/DC-SIGN+ cells (purple, white arrow) surrounding a capillary vessel (blue, *) with one single CD14+ cell (red, black arrow). K: Two double CD4+/DC-SIGN+ decidual cells (green/brown). L: Perinuclear expression of CD68 (purple) in a DC-SIGN+ (brown) cell. Original magnifications: ×400 (A, C, D, F, G); ×160 (B); ×250 (E); ×1000 (H–L).

To further characterize the phenotype of DC-SIGN+ cells immunohistochemical double stainings were performed. All DC-SIGN+ cells in decidual tissue expressed HLA-DR (Figure 2, D and I) ▶ , CD14 (Figure 2, E and J) ▶ , and CD4 (Figure 2, F and K) ▶ . Most of them expressed CD68+ with a perinuclear pattern (Figure 2, G and L) ▶ . Next to the double-positive cells (HLA-DR+/DC-SIGN+, CD14+/DC-SIGN+, CD4+/DC-SIGN+, and CD68+/DC-SIGN+) some single-positive cells for HLA-DR, CD14, CD4, and CD68 were detected (Figure 2; D to F) ▶ , but not vice versa.

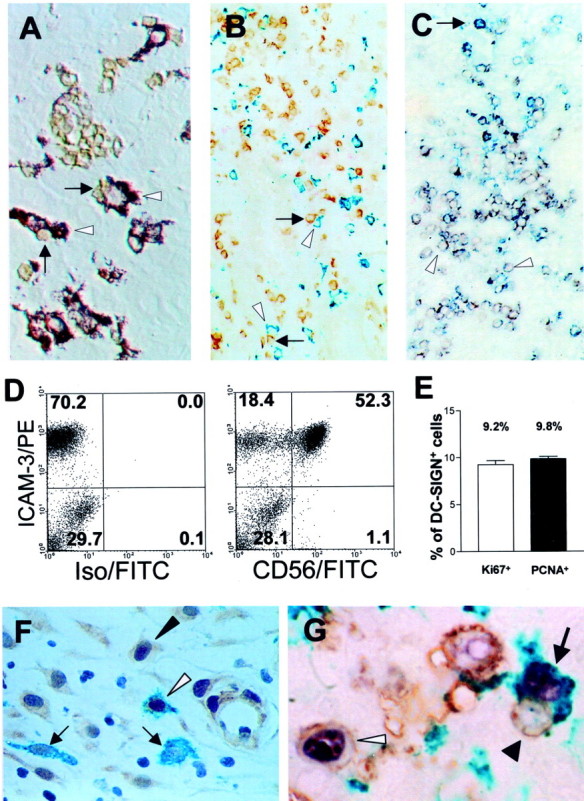

In contrast to the smaller CD83+ mature DCs, which were often found in clusters with CD3+ T cells, 1 DC-SIGN+ cells were only occasionally seen in clusters with more than three T cells (Figure 2C) ▶ . However, the majority of DC-SIGN+ cells was found in close contact to CD56+ LGLs (Figure 3A) ▶ . Quantification of LGL/DC-SIGN cell clusters revealed 52 ± 4.9% SD of DC-SIGN+ cells to be associated with one LGL, 9.6 ± 4.5% SD with two LGLs, and 1.9 ± 1.2% SD with three LGLs. Only very occasionally DC-SIGN+ cells were found in intimate contact with more than three LGLs. Co-staining of DC-SIGN+ with ICAM-3, a ligand for DC-SIGN, revealed, that many of ICAM-3-positive cells resembling LGLs were attached to the DC-SIGN+ cells (Figure 3B) ▶ . Indeed, double labeling clearly demonstrated all LGLs to be positive for ICAM-3 and only occasionally single cells to be ICAM-3+/CD56− (Figure 3C) ▶ . FACS analysis confirmed the immunohistological findings (Figure 3D) ▶ . Previously published data 19 has shown, that besides proliferating LGLs (7 to 23% Ki-67+) there are numerous Ki-67-positive CD68+ cells found in decidua. Immunohistochemical double staining (n = 10) confirmed that 9.3 ± 0.4% SD of all DC-SIGN+ cells co-expressed Ki-67 (Figure 3, E and G) ▶ . Additional double-immunohistochemical analysis using DC-SIGN/PCNA demonstrated 9.8 ± 0.3% SD of DC-SIGN+ cells to be PCNA+ (Figure 3, E and F) ▶ .

Figure 3.

Interaction of proliferating DC-SIGN+ cells with CD56+ LGLs. A: Interference contrast clearly demonstrated the intimate contact between DC-SIGN+ cells (violet, white arrowhead) with CD56+ LGLs (brown, black arrow). B: DC-SIGN+ cells (green, white arrowhead) together with ICAM-3-positive cells (brown, arrow) that resemble the morphology of LGLs. C: Double labeling of ICAM-3 (blue) with CD56 (red) demonstrated all CD56+ cells to be ICAM3+ (purple); one single ICAM3+/CD56− cell was seen (blue, black arrow). White arrowheads indicate examples of ICAM3+/CD56+ LGLs. D: FACS analysis of isolated decidual lymphocytes. Left: A high percentage of the cells express ICAM-3. Right: All CD56+ LGLs co-express ICAM-3, representing the largest population of all ICAM-3-positive cells. E: Bar chart of proliferating DC-SIGN+ cells detected by double staining with Ki-67 (white bar, ∼9.2% of all DC-SIGN+ cells) and PCNA (black bar, ∼9.8%). F: Immunohistochemistry shows clear double staining for DC-SIGN (green) and PCNA (brown, white arrowhead) some PCNA−/DC-SIGN+ cells were seen (black arrow) next to proliferating non-DC-SIGN+ cells (black arrowhead). G: Simultaneous staining for DC-SIGN (green), CD56 (brown), and Ki-67 (violet) revealed a proliferating DC-SIGN+ cell (arrow) next to a proliferating LGL (white arrowhead) and closely attached to a nonproliferating LGL (black arrowhead). Original magnifications: ×400 (A, F); ×160 (B, C); ×1000 (G).

Phenotypical Characterization of Decidual APCs in Vitro

Decidual DC-SIGN+ Cells Exhibit the Phenotype of Immature DCs

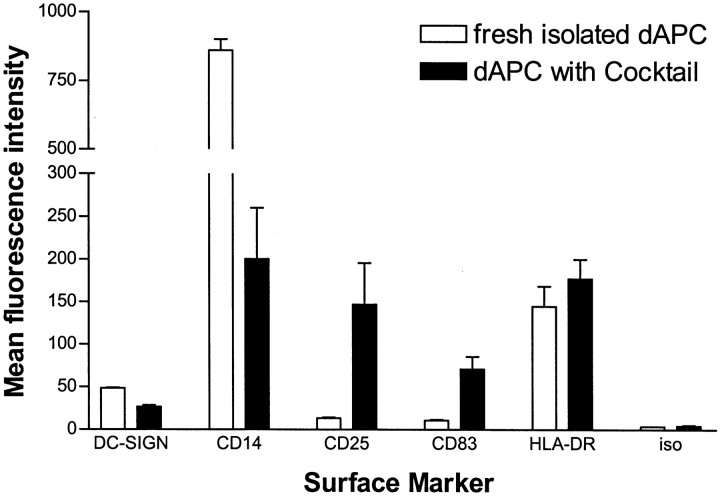

To further estimate the amount of DC-SIGN+ cells in the decidua FACS analysis was performed on freshly isolated decidual cells. As shown in Figure 4A ▶ , decidual cells contain 5 to 8% DC-SIGN+ cells. Double staining confirmed the immunohistological findings and revealed that all DC-SIGN+ cells were positive for CD14 and that the vast majority of the cells was positive for HLA-DR. DC-SIGN+ cells were clearly negative for CD83 and CD25. Intracellular staining performed with the CD14+-enriched decidual cell population revealed about 50% of the DC-SIGN+ cells to be positive for CD68 (Figure 4B) ▶ .

Figure 4.

Double-staining FACS analysis of the phenotype of decidual cells. A: Surface staining of complete cells directly after isolation: ∼6% of all decidual cells were positive for DC-SIGN (top right) and these co-stained with CD14 (middle left) and at low level with HLA-DR (middle right). DC-SIGN+ cells did not co-stain with CD83 (bottom left) and CD25 (bottom right) and were clearly different from mature DCs. B: Intracellular staining of CD14+-enriched decidual cells: ∼50% of the CD14+ cells expressed DC-SIGN+ (left and middle) and also ∼50% of the DC-SIGN+ cells expressed the macrophage marker CD68 (right).

Decidual DC-SIGN+ Cells Can Be Matured in Cell Culture into CD83+/CD25+ DCs

Analysis of APC surface marker expression by decidual CD14+ cells either freshly isolated or cultured for 3 days in the presence of a cocktail of inflammatory cytokines is shown in Figure 5 ▶ . In comparison to a slight increase in the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of HLA-DR-expression (144.9 ± 23.7 SEM on fresh cells versus 177.5 ± 22.8 SEM on cultured cells), the level of CD83 and CD25 strongly increased on culture. Although the MFI of CD83 increased sevenfold (from 10.8 ± 1.1 SEM on fresh cells to 70.9 ± 14.8 SEM on cultured cells), the MFI of CD25 increased dramatically (13.4 ± 0.9 SEM on fresh cells versus 146.9 ± 48.7 SEM on cultured cells). In contrast to the maturation markers, treatment of decidual CD14+ cells with cocktail resulted in a decrease of DC-SIGN and CD14. Whereas the MFI for DC-SIGN on cultured cells was reduced to half (48.7 ± 0.5 SEM to 26.7 ± 1.9 SEM), expression of the monocyte/macrophage marker CD14 dropped extensively (200.4 ± 60.0 SEM on cultured cells versus 860.0 ± 40.6 SEM on fresh cells).

Figure 5.

Bar charts of the comparison of APC surface marker expression on freshly isolated and cultured (15 hours in R10 with maturation cocktail) decidual CD14+ cells showing the mean of the fluorescence intensity (MFI, PE-channel). Whereas the MFI of DC-SIGN and CD14 were reduced to ∼50% (DC-SIGN) and to <20% (CD14) on maturation culture, the MFI of the maturation markers CD25 and CD83 dramatically increased, reflecting the capacity of the decidual CD14+ cells to efficiently mature into typical DCs. HLA-DR showed only a slight increase in the MFI and the isotype controls were negative in both populations.

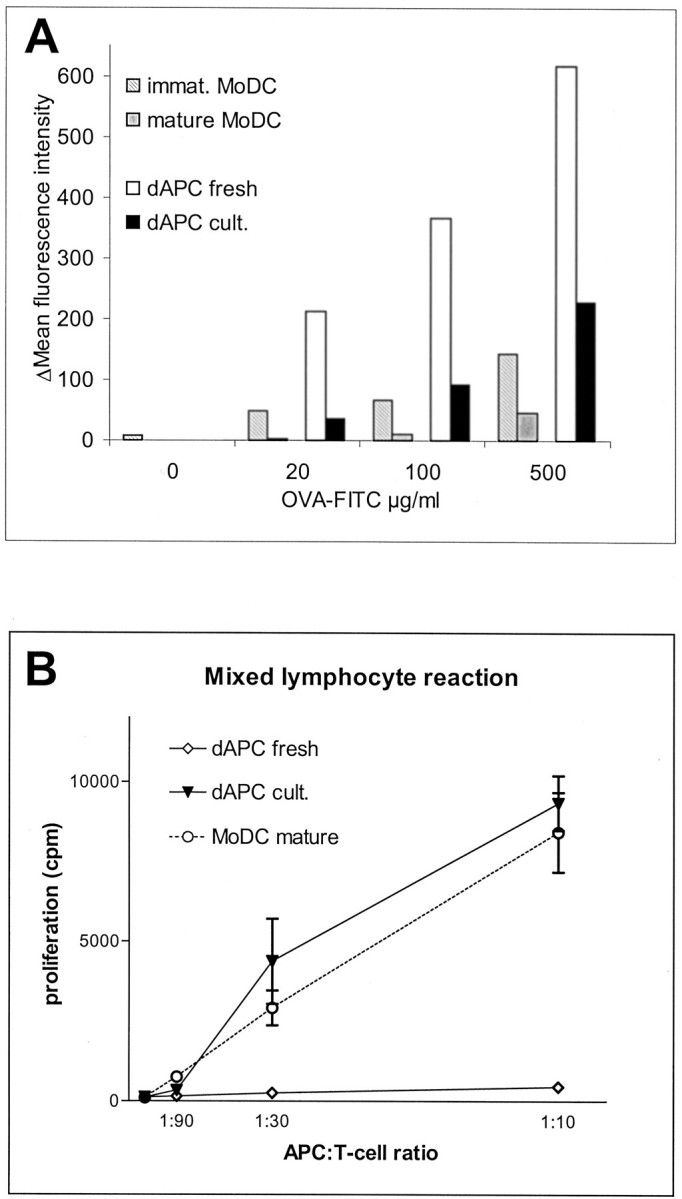

Functional Analysis of Fresh Isolated and Cocktail Matured Decidual APCs in Comparison to Monocyte-Derived DCs

Because of the fact that the DC-SIGN antibody blocks DC-T-cell interaction 13 and thereby inhibits T-cell proliferation in allogeneic T-cell proliferation assays, decidual DC-SIGN+ APCs were enriched by CD14 selection, resulting in a population of ∼80% HLA-DR+ cells containing 50 to 70% DC-SIGN+ cells.

To further analyze the maturation stage of these DC-SIGN+ APCs antigen uptake and allogeneic T-cell stimulation capacity assays were performed as shown in Figure 6 ▶ . In a dose-dependent manner, fresh CD14+ enriched dAPCs had a very high FITC-OVA uptake capacity (fourfold higher than immature MoDCs) that decreased on maturation to levels exhibited by immature MoDCs (Figure 6A) ▶ .

Figure 6.

Functional analysis of fresh (dAPC fresh) and cocktail matured (dAPC cult.) decidual CD14+ cells containing 50 to 70% DC-SIGN+ cells in comparison to monocyte-derived immature (MoDC immat.) and cocktail-matured (MoDC mature) DC. A: FITC-labeled ovalbumin (OVA-FITC) antigen uptake capacity by fresh dAPCs was fourfold higher than that of matured dAPCs, which displayed levels comparable to immature MoDC. B: Immunostimulatory activity of dAPC fresh and dAPC cult. in comparison to mature MoDC in a mixed lymphocyte reaction with MHC-mismatched responder T lymphocytes at the indicated ratios of APCs and T cells. Results are shown as the mean [3H]-thymidine uptake (proliferation) ± SEM for three samples each. [3H]-thymidine uptake of all APC and T-cell populations alone was <400 cpm and is not shown.

After cocktail maturation, decidual APCs stimulated allogeneic T cells as efficiently as cocktail matured MoDCs (Figure 6B) ▶ . Interestingly freshly isolated decidual APCs did not have any stimulatory capacity, even at the highest APC:T cell ratio no T-cell proliferation was apparent. Nevertheless, the allostimulatory capacity of cocktail matured dAPCs was in all cases slightly higher than those of the control MoDCs. These data reflect the particular ability of the isolated decidual APCs to efficiently mature into potent stimulators of allogeneic T cells on exposure to DC maturation stimuli such as a cocktail of inflammatory cytokines.

Discussion

Human decidual tissue appears to play an important role in the immune surveillance of the implanted embryo. Many features of the local maternal-fetal interaction in the uterus are related to the primitive innate immune systems. 20 Two of the immune cell types appearing early in ontogeny are phagocytes and natural killer cells, which seem to be the most primitive cytolytic cells. 21 Both, phagocytes and natural killer cells persist during ontogeny and can be found in the human decidualized endometrium (decidua), where the embryo implants. Compared with the uterine endometrium, early decidual tissue has been shown to contain a markedly increased number of granulated CD56+ natural killer cells. These LGLs are the predominant cell population during early human pregnancy. 22,23 CD14+ cells, generally described as decidual macrophages, constitute the second main cell population. 22 Here we report, that nonpregnant endometrium and decidua harbor macrophage/dendritic-like cells expressing CD4/HLA-DR/CD68/CD14, but only in the decidua do these APCs co-express the DC-SIGN antigen. DC-SIGN+ cells, however, were found in nonpregnant uterine samples in outer regions of the myometrium (not shown).

DC-SIGN+ cells were recently described in placenta 24,25 and decidual tissue. 26 In line with our findings, Soilleux and colleagues 26 found co-expression of CD4 by DC-SIGN+ cells. The reported high number of CD4+ cells contrasts previous characterizations of leukocyte populations in human decidua 27,28 but can be explained by optimized immunohistochemical staining systems that allow the detection of even weak CD4 expression by DC-SIGN+ cells.

The appearance of DC-SIGN+ cells in the decidua is a pregnancy-associated event and may result from up-regulation of this surface marker on a subpopulation of endometrial macrophage/dendritic-like cells induced by signals related to the exogenous and endogenous tissue damage caused by invading trophoblasts. A candidate signal is IL-13 expressed at high levels in the placenta. 29 This Th-2-type cytokine has recently been shown in vitro to significantly up-regulate the DC-SIGN surface expression on macrophages. 26 Alternatively, with onset of pregnancy DC-SIGN+ cells of the myometrium or blood 15 might invade the decidua and then proliferate in situ. This hypothesis is supported by our finding of a remarkable number of proliferating Ki67+/DC-SIGN+ or PCNA+/DC-SIGN+ cells within the decidua (∼10%).

Because human endometrium appears to harbor DC-SIGN+ cells only during decidualization, these cells might play a crucial role for the local immune response at the barrier between immunity and tolerance. Of special interest seems to be the close topographical relationship of pregnancy-related DC-SIGN+ cells with ICAM-3-expressing LGLs. Corresponding to the high affinity of DC-SIGN for ICAM-3, 13 this intimate cell contact is likely mediated by DC-SIGN/ICAM-3 interactions. Hypothetically, binding of ICAM-3-positive LGLs to DC-SIGN+ decidual APCs may on one hand prevent the interaction of DC-SIGN+ cells with T cells, and furthermore impede maturation of DC-SIGN+ APCs into potent immunostimulatory DCs. Indeed, LGLs have been shown to produce a wide range of cytokines, 30 especially high local concentrations of GM-CSF 31 and IL-10 32 known as a potent inhibitor of DC maturation. On the other hand, interaction of DC-SIGN+ APCs with LGLs might result in activation of LGLs and even stimulate their proliferation. 19 Further studies on the interaction of these two pregnancy-related cell populations should help understanding how immune responses in human pregnancy are regulated.

Finally, we show that decidual DC-SIGN+ cells in situ and in vitro not only resemble immature DCs by phenotype and function, but in addition very effectively may be turned into potent immunostimulatory CD83+/CD25+ mature DC in vitro if maturation stimuli such as a cocktail of inflammatory cytokines are provided. From these data we conclude, that at least three different macrophage/DC populations do occur in human early pregnancy decidua: classical macrophages, 22 mature CD83+ DCs, 1 and DC-SIGN expressing immature DC-like APCs prone to mature into potent immunostimulatory DCs. Because macrophages and immature MoDCs principally are able to convert into one another until late stages of their respective differentiation/maturation process, 33,34 our DC-SIGN+ immature DC-like decidual cell may correspond to the transient differentiation cell type (the “veiled immediate DC precursors”) postulated by Palucka and colleagues. 33 It is tempting to speculate that the local cytokine environment and cellular interactions within the decidua may well constitute the final decision-making factors determining whether DC-SIGN+ APCs will acquire characteristics and functions of macrophages or mature DCs.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Ulrike Kämmerer, Ph.D., Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Josef-Schneider-Str. 4, D-97080 Würzburg, Germany. E-mail: frak057@mail.uni-wuerzburg.de.

Supported by grants from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01KS9603 to U. K. and 01KX9820/L to A. O. E.) and the Interdisciplinary Center of Clinical Research Würzburg (IZKF to U. K., A. O. E., A. D. M., and E. K.).

U. K. and A. O. E. both contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Kammerer U, Schoppet M, McLellan AD, Kapp M, Huppertz HI, Kampgen E, Dietl J: Human decidua contains potent immunostimulatory CD83(+) dendritic cells. Am J Pathol 2000, 157:159-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart DN: Dendritic cells: unique leukocyte populations which control the primary immune response. Blood 1997, 90:3245-3287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinman RM: The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol 1991, 9:271-296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inaba K, Metlay JP, Crowley MT, Steinman RM: Dendritic cells pulsed with protein antigens in vitro can prime antigen-specific, MHC-restricted T cells in situ. J Exp Med 1990, 172:631-640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas R, Davis LS, Lipsky PE: Comparative accessory cell function of human peripheral blood dendritic cells and monocytes. J Immunol 1993, 151:6840-6852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buelens C, Willems F, Delvaux A, Pierard G, Delville JP, Velu T, Goldman M: Interleukin-10 differentially regulates B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) expression on human peripheral blood dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol 1995, 25:2668-2672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu L, Rich BE, Inobe J, Chen W, Weiner HL: Induction of Th2 cell differentiation in the primary immune response: dendritic cells isolated from adherent cell culture treated with IL-10 prime naive CD4+ T cells to secrete IL-4. Int Immunol 1998, 10:1017-1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piemonti L, Monti P, Allavena P, Sironi M, Soldini L, Leone BE, Socci C, Di CV: Glucocorticoids affect human dendritic cell differentiation and maturation. J Immunol 1999, 162:6473-6481 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alpan O, Rudomen G, Matzinger P: The role of dendritic cells, B cells, and M cells in gut-oriented immune responses. J Immunol 2001, 166:4843-4852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelsall BL, Strober W: Distinct populations of dendritic cells are present in the subepithelial dome and T cell regions of the murine Peyer’s patch. J Exp Med 1996, 183:237-247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maldonado-Lopez R, De Smedt T, Pajak B, Heirman C, Thielemans K, Leo O, Urbain J, Maliszewski CR, Moser M: Role of CD8alpha+ and CD8a. J Leukoc Biol 1999, 66:242-246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiner HL: The mucosal milieu creates tolerogenic dendritic cells and T(R)1 and T(H)3 regulatory cells. Nat Immunol 2001, 2:671-672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geijtenbeek TB, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Adema GJ, van Kooyk Y, Figdor CG: Identification of DC-SIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell 2000, 100:575-585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geijtenbeek TB, Krooshoop DJ, Bleijs DA, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Grabovsky V, Alon R, Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y: DC-SIGN-ICAM-2 interaction mediates dendritic cell trafficking. Nat Immunol 2000, 1:353-357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geijtenbeek TB, Kwon DS, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Middel J, Cornelissen IL, Nottet HS, KewalRamani VN, Littman DR, Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y: DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell 2000, 100:587-597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtis BM, Scharnowske S, Watson AJ: Sequence and expression of a membrane-associated C-type lectin that exhibits CD4-independent binding of human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein gp120. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992, 89:8356-8360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romani N, Reider D, Heuer M, Ebner S, Kampgen E, Eibl B, Niederwieser D, Schuler G: Generation of mature dendritic cells from human blood. An improved method with special regard to clinical applicability. J Immunol Methods 1996, 196:137-151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLellan AD, Heiser A, Sorg RV, Fearnley DB, Hart DN: Dermal dendritic cells associated with T lymphocytes in normal human skin display an activated phenotype. J Invest Dermatol 1998, 111:841-849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kammerer U, Marzusch K, Krober S, Ruck P, Handgretinger R, Dietl J: A subset of CD56+ large granular lymphocytes in first-trimester human decidua are proliferating cells. Fertil Steril 1999, 71:74-79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sacks G, Sargent I, Redman C: An innate view of human pregnancy. Immunol Today 1999, 20:114-118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herzenberg LA, Kantor AB, Herzenberg LA: Layered evolution in the immune system. A model for the ontogeny and development of multiple lymphocyte lineages. Ann NY Acad Sci 1992, 651:1-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bulmer JN, Pace D, Ritson A: Immunoregulatory cells in human decidua: morphology, immunohistochemistry and function. Reprod Nutr Dev 1988, 28:1599-1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starkey PM, Sargent IL, Redman CW: Cell populations in human early pregnancy decidua: characterization and isolation of large granular lymphocytes by flow cytometry. Immunology 1988, 65:129-134 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soilleux EJ, Morris LS, Lee B, Pohlmann S, Trowsdale J, Doms RW, Coleman N: Placental expression of DC-SIGN may mediate intrauterine vertical transmission of HIV. J Pathol 2001, 195:586-592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geijtenbeek TB, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y: DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1 receptor present in placenta that infects T cells in trans—a review. Placenta 2001, 22(Suppl A):S19-S23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soilleux EJ, Morris LS, Leslie G, Chehimi J, Luo Q, Levroney E, Trowsdale J, Montaner LJ, Doms RW, Weissman D, Coleman N, Lee B: Constitutive and induced expression of DC-SIGN on dendritic cell and macrophage subpopulations in situ and in vitro. J Leukoc Biol 2002, 71:445-457 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dietl J, Ruck P, Horny HP, Handgretinger R, Marzusch K, Ruck M, Kaiserling E, Griesser H, Kabelitz D: The decidua of early human pregnancy: immunohistochemistry and function of immunocompetent cells. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1992, 33:197-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vassiliadou N, Bulmer JN: Characterization of endometrial T lymphocyte subpopulations in spontaneous early pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod 1998, 13:44-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dealtry GB, Clark DE, Sharkey A, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith SK: Expression and localization of the Th2-type cytokine interleukin-13 and its receptor in the placenta during human pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol 1998, 40:283-290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saito S, Nishikawa K, Morii T, Enomoto M, Narita N, Motoyoshi K, Ichijo M: Cytokine production by CD16-CD56bright natural killer cells in the human early pregnancy decidua. Int Immunol 1993, 5:559-563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jokhi PP, King A, Loke YW: Production of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by human trophoblast cells and by decidual large granular lymphocytes. Hum Reprod 1994, 9:1660-1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rieger L, Kammerer U, Hofmann J, Sutterlin M, Dietl J: Choriocarcinoma cells modulate the cytokine production of decidual large granular lymphocytes in coculture. Am J Reprod Immunol 2001, 46:137-143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palucka KA, Taquet N, Sanchez-Chapuis F, Gluckman JC: Dendritic cells as the terminal stage of monocyte differentiation. J Immunol 1998, 160:4587-4595 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Randolph GJ, Beaulieu S, Lebecque S, Steinman RM, Muller WA: Differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells in a model of transendothelial trafficking. Science 1998, 282:480-483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]