Abstract

We have used prostate cancer, the most commonly diagnosed noncutaneous neoplasm among men, to investigate the feasibility of performing genomic array analyses of archival tissue. Prostate-specific antigen and a biopsy Gleason grade have not proven to be accurate in predicting clinical outcome, yet they remain the only accepted biomarkers for prostate cancer. It is likely that distinct spectra of genomic alterations underlie these phenotypic differences, and that once identified, may be used to differentiate between indolent and aggressive tumors. Array comparative genomic hybridization allows quantitative detection and mapping of copy number aberrations in tumors and subsequent associations to be made with clinical outcome. Archived tissues are needed to have patients with sufficient clinical follow-up. In this report, 20 formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded prostate cancer samples originating from 1986 to 1996 were studied. We present a straightforward protocol and demonstrate the utility of archived tissue for array comparative genomic hybridization with a 2400 element BAC array that provides high-resolution detection of both deletions and amplifications.

Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) affords high-resolution quantitative information regarding DNA copy number changes within tumor genomes. Recurrent deletions and amplifications reveal loci encoding tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes, respectively, and their identification is now facilitated by completion of the human genome sequence. Moreover, it is increasingly evident that differing clinical behavior of histologically similar tumors is because of distinct and recurrent patterns of genomic alterations and that these may define distinct subsets of disease and thus be prognostic. 1-4 aCGH is ideally suited to delineating these genomic differences and for the development of biomarkers. However, the coupling of aCGH and clinical data for biomarker discovery and disease stratification requires patients with significant clinical follow-up, meaning that in most cases archived tumor material must be used to identify associations between copy number changes and clinical outcome.

In aCGH, microarrayed BAC DNA targets are co-hybridized with differentially fluorophore-labeled DNAs from normal reference and tumor test genomes. 5,6 Gene copy number along the genome is proportional to the ratio of the fluorescent intensities. In this study, we used a whole genome-scanning array containing DNA from 2460 BAC clones, which provides an average resolution of ∼1.4 Mb. 7 An advantage of this array is that all of the clones have been mapped on the UCSC genome assembly (http://genome.ucsc.edu/index.html) and thus can be computationally linked to the underlying and annotated genome sequence. Paraffin-embedded tissue has recently been reported to be suitable for aCGH; however the array in their study only consisted of 58 BACS containing known oncogenes. 8 In addition, their technique required degenerate oligonucleotide-primed polymerase chain reaction (DOP-PCR) amplification of the tumor material.

In this report, we show that archived prostate tissue can be used with a whole genome-scanning array without a probe amplification step, eliminating the possibility of introducing artifactual copy number gains and losses that can result from biased amplification. In contrast to the expensive and laborious method of laser microdissection, we demonstrate that the use of a bore coupled to a microscope for the dissection step works well. Our extraction procedure also includes a xylene treatment, RNase treatment, and protein precipitation in addition to the lysis step. Our method for aCGH on paraffin-embedded tissue allows the identification of DNA copy number changes at high resolution including detection of single copy losses and gains. These genome-wide copy number abnormalities (CNAs) in turn can provide valuable insight into critical genomic clones and genes that may serve as biomarkers. Detection of CNAs was confirmed through comparison to chromosome CGH (some previously published) 9,10 using the same tumor DNA and through use of quantitative microsatellite analysis (QuMA), a quantitative PCR technique related to TaqMan.

Materials and Methods

Specimens

Archival prostate cancer specimens were obtained between 1986 and 1996. Four metastases (two brain, one regional lymph node, and one bone metastasis; samples 1 to 4) and 16 primary tumors from patients who underwent radical prostatectomy alone (samples 5 to 20) were included in this preliminary study. The tumors were pathologically staged according to the pTNM classification 11 and graded according to the Gleason grading system. 12 Isolation of DNA from the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor material was performed as described by Alers and colleagues. 13 Briefly, the tissue blocks were counterstained in 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and placed under a fluorescence microscope, enabling a precise selection of the tumor area. Microdissection of the tumor areas was performed using a hollow bore coupled to the microscope. In the case of very small tumor areas, manual microdissection of the selected areas was performed by scraping successive hematoxylin-stained 10-μm tissue sections using a needle under a stereomicroscope. Lower boundaries were checked for the presence of tumor on 4-μm hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue sections. Isolation of DNA from the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded material was performed using the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, except that the DNA was hydrated with 25 μl of 10 mmol/L Tris, pH 8.

Arrays

Genomic target DNA was isolated from bacterial cultures and arrayed as described previously, 5 except chromium-coated slides were used (Nanofilm, Westlake Village, CA). Each array consists of 2460 BACS spotted in triplicate with ∼1.4 Mb average resolution. 7

Array Comparative Hybridization

One μg each of test and reference male (Promega, Madison, WI) genomic DNA was labeled by random priming using a Bioprime Labeling Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The manufacturer’s protocol was followed with the following concentration changes; 120 μmol/L of dATP, dGTP, and dCTP; 30 μmol/L of dTTP; and 40 μmol/L of CY3-dUTP or CY5-dUTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Random DNA octamers served as the primers (Invitrogen). Unincorporated nucleotides were removed using a Qiagen QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was eluted in 100 μl of EB buffer (provided with kit). Labeled test and reference DNAs were co-precipitated in the presence of Cot-1 DNA (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) with ethanol. The precipitated DNA was redissolved in a hybridization solution containing 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 2× standard saline citrate, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 10 μg/μl of yeast tRNA. The probes were denatured at 72°C for 10 minutes and then preannealed with a 1-hour incubation at 37°C. Each array was surrounded by a wall of rubber cement on the chromium-coated slide and then was cross-linked (Stratagene UV Stratalinker, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, 2600 × 100 μJ). The hybridization mixture (60 μl) was added to each array. A rubber gasket and a glass microscope slide fastened to the slide provided an enclosed chamber for the hybridization. A 48-hour hybridization at 37°C was performed on a unidirectional tilting platform (3 rpm) within an incubator. Slides were washed for 15 minutes in 50% formamide, 2× standard saline citrate, pH 7.0 at 45°C, 2× standard saline citrate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 20 minutes at 45°C, and once in 0.1 mol/L sodium phosphate buffer, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, pH 8, for 10 minutes. The array was counterstained with a 1 μg/μl of DAPI solution.

A charge-coupled device camera equipped with filters for CY3, CY5, and DAPI was used to capture the aCGH images. The imaging set up and custom software are described elsewhere. 5 Imaging processing was performed with SPOT version 1.2 and SPROC version 1.1.1 software packages. 14 Log2 ratios of either greater than or less than 0.5 were defined as chromosomal gains or losses, respectively.

Array validation was performed by hybridization with normal human female against normal reference human male DNA. The female DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded tissue as described in the subsection above entitled “Specimens.” The male reference was the same reference used in all experiments.

Comparative Genomic Hybridization

Tumor DNA with a fragment size of <1 kb was chemically labeled with biotin-universal linkage system (ULS) or fluorescein-ULS (Kreatech Diagnostics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Tumor DNA with larger DNA fragment sizes was labeled by nick translation with biotin (Nick Translation System; Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) or with green fluorescent nucleotides (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands). Likewise, male reference DNA (Promega) was labeled by nick translation with digoxigenin or red fluorescent nucleotides (both from Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). The reaction time and the amount of DNase were adjusted to obtain a matching probe size for reference and tumor DNAs. The labeled DNAs were hybridized onto normal male metaphase chromosomes (Vysis Inc., Downers Grove, IL), as described previously. 9,10,15,16 After washing of the slides, fluorescent detection of the biotin- and digoxigenin-labeled DNA probes was accomplished with avidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate and anti-digoxigenin rhodamine, respectively. CGH analysis was performed with Quips XL software version 3.1.1 (Vysis). Loss of DNA sequences was defined as chromosomal regions in which the mean green:red ratio was below 0.85, whereas gain was defined as chromosomal regions in which the ratio was more than 1.15. These threshold values were based on a series of normal controls (data not shown).

Quantitative Microsatellite Analysis (QuMA)

A QuMA assay was developed to cover the region spanning from the WWOX gene at 16q23.1 to the telomere at 16q24.3. The copy number of the test locus was assessed using quantitative, real-time PCR, and related to a pooled reference. Experimental design and procedure was performed as detailed in Ginzinger and colleagues. 17 Control primers were a pool of oligos designed to amplify loci in regions where CNA is not observed in prostate cancer (DG Ginzinger, unpublished results).

Results and Discussion

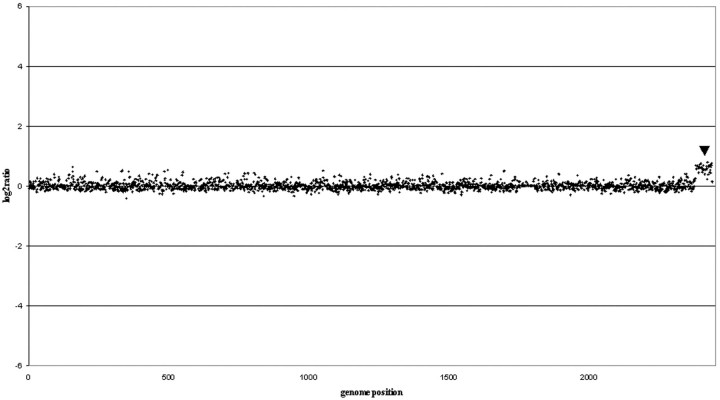

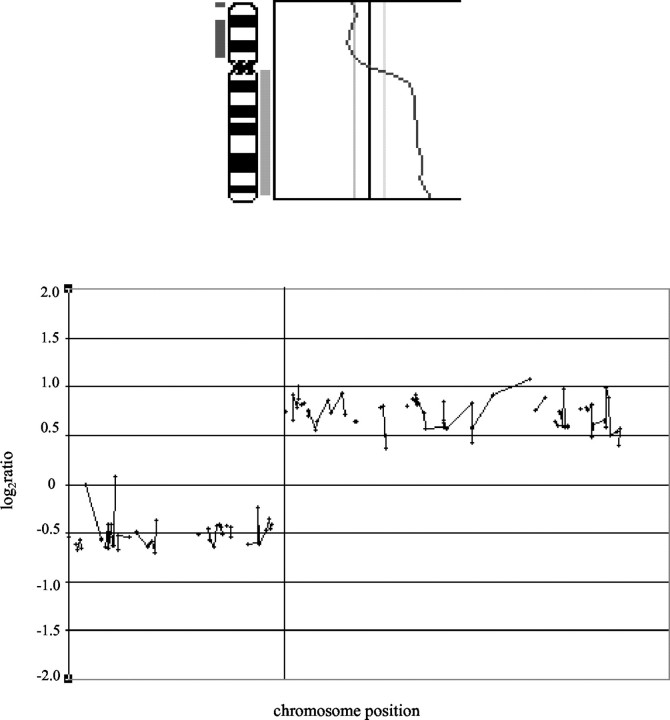

The aim of this study was to determine whether DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded prostate tumors (up to 16-years-old) could be used for mapping CNAs, both gains and losses, by aCGH. Hybridization of female DNA extracted from paraffin with the male reference DNA used in all of the experiments, detected as expected a gain of chromosome X (Figure 1) ▶ . Chromosome CGH profiles were available for the 20 tumors analyzed and these were directly compared to the aCGH copy number profiles. A graphical representation of one such comparison for chromosome 8 is presented in Figure 2 ▶ . Table 1 ▶ contains a list of CNAs found by both techniques.

Figure 1.

Array validation: female versus male. aCGH result using normal female DNA (from paraffin) versus normal male. The female tissue was from normal lymph nodes. The DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded tissue as described in Materials and Methods. The male reference was the same reference used in all experiments. Log2 ratios along the genome are depicted, showing a clear sex-mismatch for the X chromosome (denoted by arrowhead).

Figure 2.

Comparing CGH with aCGH for chromosome 8 in sample 2. A comparison of chromosomal CGH (top) with aCGH (bottom) for chromosome 8 in prostatic cancer sample 2. In the CGH figure, loss is displayed as a bar to the left of the chromosome 8 ideogram, gain is seen as a bar to the right. In the aCGH graph, a log2 scale is used, values below 0 signify loss, above 0 gain of DNA sequences. Note good concordance between the two CGH techniques.

Table 1.

CGH Results Compared to aCGH Findings*†

| Sample number | CGH results | aCGH results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Deletions | |||

| 1 | 1q31-qter, 5q11.2-q13, 6q12-q22, 8p11.2-pter | 1p36 (1), 1p32.1 (1), 1q31-q41, 1q43-44, 2p12-p13 (1), 5q11.2-q12, 5q22-23 (1), 5q31-q31.3, 6q12-15,7p21.1b (1), 8p12-p23, 10q22.3-q23, 15q11.2 (1), 16q22-q24, 18p11.31-p11.32, 20q11.2-12 (1), 21q22.2-q22.3, Xp11.3 (1) | |

| 2 | 4q24-q26, 5q11.2-q23, 6q14-q22, 8p11.2-pter, 9p13-p21, 10q21-qter, 12p11.2-p13, 12q23-qter Xq21-q22 | 4q25-26, 5q11-q34, 6q14-q22.3, 7q11.2 (1), 7q36.2-q36.3, 8p11.2-p23.3, 9p21.1-23, 10q21.1-q26.3, 11q13.5 (1), 12p11.2-13.3, 12q23-24.3, 13q12.1 (1), 16q22-24, 17p12 (1), 19p13.3 (1) | |

| 3 | 1q31-qter, 2q21-q22, 4q12-qter, 5q13-q23, 6q15-q22, 10q11.2-q22, 10q23-q24, 11p13-pter, 11q22-qter, 13q12-qter, 15q14-qter, 16q21-qter, 17p12-pter, Y | 1q21-22 (1), 1q32, 1q41, 4p16, 4q21-23, 5q13 (1), 5q21 (1), 5q23-31, 6q21-22.1, 7p21, 8q21.1 (1), 9q33, 10q22.3 (1), 10q26.3 (1), 11p12-p15.5, 11q22-q25, 13q14.1 (1), 13q21.1 (1), 13q31.1 (1), 13q34 (1), 15q11.2, 15q14-15, 15q21-q26.2, 16q13-24, 17p12-13, 18p11.31p11.32 (1), 18q22 (1), Xp21.1 (1), Yqter | |

| 4 | 2q14.2-q24, 5q12-q22, 6q12-q22, 13q13-q22 | 1p21-31, 2q22 (1), 2q24, 2q32 (1), 4p15 (1), 4q21-q23, 4q26-q31, 4q35, 5q12-q15, 5q21-q23, 5q32-q34, 6p12 (1), 6p22 (1), 6q11-q22, 7p21 (1), 8q21 (1), 8q24 (1), 9p21-p23, 10p11-p14, 10q21-q26, 11p12-p15, 11q14 (1), 11q22, 12q21-q22 (1), 13q13-q14, 13q21-q31, 14q22 (1), 18p11 (1), 19p11-q11 (1), 20p12-p13, 21q11 (1), 21q21, Xq21 | |

| 5 | 13q21 | 14q-tel | |

| 6 | 1p21-p22, 3q24-q25, 5q14-q21, 13q14-q31 | 3q24-q25, 5q12, 9p24 (1), 13q14-q31 | |

| 7 | 6q14-q16 | 2q32.1, 4q28-q31 (1), 6q15, 7p13 (1), 7q11.1-q11.2 (1), 7q33, 9p21 (1), 11p15.4 (1), 21q22.2-q22.3 (1), 22q12 (1) | |

| 8 | 8p11.2-pter, 16q23-qter | 1q22-q23 (1), 3p14.3 (1), 3q13, 4q21, 5p15 (1), 7q11.22 (1), 8p12-p22, 9p24, 10p15 (1), 10q24 (1), 11q14 (1), 12q23 (1), 15q23 (1), 18q22 (1), 20q13.3 (1), 21q21 (1) | |

| 9 | 8p12-p22, 16q22-qter | 3p21.2 (1), 8p11-p23, 14q-tel (1), 16q23.1 (1), 16q24 (1), 21q11.1-q11.2, Xq27-28 (1) | |

| 10 | 4p12-p14, 5q11.2-q21, 10q23-q24, 13q21, 14q22-q24, 15q11.2-q21, 16q12.1-q22, 18, Xq21-q26 | 2p12-2p11.2 (1), 2q24.3, 4p12-p14, 4q32 (1), 5p15 (1), 5q14 (1), 6p21 (1), 7p12-p13 (1), 7q21, 7q33-35 (1), 9q31 | |

| 11 | 8p11.2-pter, 12p11.2-pter | 8p23.2, 8p22, 12p12 | |

| 12 | 8p11.2-pter, 18q11.2-qter | 8p23.1-p23.2, 18q12, 18q22 | |

| 13 | 13q21-q22 | 3p14, 6q26 (1), 16q23-q24 | |

| 14 | 6q16-q22 | 6q15-q16.1, 6q22.2-q22.3, 6q26 (1) | |

| 15 | 2q21-q22, 5q12-q13, 6q12-q21, 13q14-q21 | 2q21.2-q22, 4q27-q31.1, 6q15, 8p22-p23.2, 12p13.1 | |

| 16 | 8p12-pter, 17p11.2-p12 | 2q37.3, 6q21-q22.1, 8p21.2-p23.2, 8p11.2-p12, 16q23-q24, 17p12, 17q11.2, 18p11.21 | |

| 17 | 6q14-q22, 8p11.2-p21 | 5q21-q31, 6q14, 8p23.3, 8p12-p21.3, 10q23, 15q23-q24, 17p12 | |

| 18 | 2q21-q22, 13q14-q22 | 2q21.1-q23, 18q22, Xp11.3-p11.4 | |

| 19 | 5q15-q22, 6q13-q22, 8p11.2-pter, 11q14-q23, 12q15-q21, 13q14-q21 | 4q26-q28, 4q33, 5q21-q23, 6q12-q22, 8p12, 8p23, 10q24-q25, 11q21-q24, 12q21, 13q-q14, 13q21 | |

| 20 | 6q12-q24, 13q13-q32 | 4p15.1, 4q33, 6q12-q13, 6q22, 7q11.22, 7q31-q32, 9q21.3, 11q23, 13q14-q22, 13q31, 14q23, 16q21 | |

| B. Gains | |||

| 1 | 3q13.3-qter, 12q21-qter, 20q12-qter | 3p23-24 (1), 3q13.3 (1), 3q24-25, 3q26.1-26.2, 3q28, 3q29 (1), 8q12.1, 8q21.1-21.2, 8q22.2 (1), 12q21.1-q22, 12q23 | |

| 2 | 7p15-pter, 7q31-q34, 8q11.2-qter | 7p21.1-p22.1, 7q33-q35, 8q11-q24.2, 18p11.31-p11.32, 20p13 (1), 22q12-qtel | |

| 3 | 1q21-q22, 5p14-pter, 6p21.1, 7q31-qter, 11q12-q14, 17q11.2-qter | 1q12 (1), 1q21, 3p14.3 (1), 3q24-q25 (1), 3q26 (1), 3q28 (1), 4q28-q31 (1), 5p14.3-p15.3, 6p22 (1), 7q32 (1), 7q34-q35, 9p12-p13 (1), 9q23.3 (1), 9q32-q33 (1), 11p11.2-p13, 11q13-q14, 11q21 (1), 11q22 (1), 17p12 (1), 17q21-q25 | |

| 4 | 3p13-pter, 3q13.3-q21, 3q26.3-qter, 7pter-qter | 1p31 (1), 1p36, 1q12 (1), 1q25 (1), 2p25 (1), 2q35-q36, 3p21-p26, 3q13, 3q21 (1), 13q23-q25, 3q26 (1), 3q29 (1), 4q13-q21, 4q31-q32, 5ptel (1), 7p11-p15, 7p21-p22, 7q11 (1), 7q21-qtel, 9p13-p21 (1), 9q21 (1), 9q34 (1), 10p11.2 (1), 10q21-q23, 11p11-p15, 11q13.4 (1), 12p13 (1), 12q13 (1), 12q24 (1), 14q23 (1), 14q31-q32, 15q11.2 (1), 16q24 (1), 17p12-p13, 17q12-q21, 17q24-q25, 18q21, 20q11-q13, Xq11-q12 (1) | |

| 5 | 3p14.3 (1), 7q36.3 (1), 9q34 (1), 11q12-q13 (1), 15q26.1 (1) | ||

| 6 | 6p21.1-p21.3, 14q24-qter, 20q11.2-qter | 1q34 (1), 3p13-p14 (1), 5q31 (1), 6p21.1-p21.3, 7q36 (1), 10p11.2-p12 (1), 11p13-p14 (1), 12q13 (1), 14q24.1 (1), 18p11.21, 20q13.3 (1), Xp22.3 (1) | |

| 7 | 17q23-q24 | 1p36 (1), 3p25 (1), 6p21.3 (1), 9q34 (1), 17p12 (1) | |

| 8 | 1p12 (1), 3p21.2 (1), 4q12 (1), 7q34 (1), 11p15.2-11p15.3 (1), 11p14 (1), 13q12 (1), 13q21.1, 21q22.1 (1) | ||

| 9 | 1p36 (1), 1q42-q43 (1), 2q35-q36 (1), 3p25 (1), 4q31.1 (1), 5q33.2 (1), 7p12 (1), 7p14, 7q21.12 (1), 7q36.3 (1), 8q22.2 (1), 9q34.2 (1), 10q26.2 (1), 11p14.1 (1), 11q23.2 (1), 12q13.2 (1), 12q21.3-q22 (1), 14q11.2 (1), 14q31-q32.1 (1), 18p11.21-p11.3, 18q11-12 (1), 18q23 (1), 19p13.3 (1), 22q13.1 (1), Xq26 (1) | ||

| 10 | 1q31-qter, 3p14-p21, 3q13.3-q21, 3q26.2-qter, 8q23-qter, 9q22-qter, 17q23-qter, 20q11.2-qter, Xp11.2-p22.2, Xq12-q13 | 1q41 (1), 3p22 (1), 3p26 (1), 3q21 (1), 4q21 (1), 4q31.3-4q32 (1), 5p13 (1), 5q21 (1), 7p12.2, 7p21.1 (1), 7q21.1 (1), 7q31, 7q36 (1), 8q21 (1), 11q12-q13 (1), 13q-tel (1), 15q26 (1), 17p12 1(1), 17p13 (1), 18q21(1), 20q13, Xp11-p22, Xq11-q13, Xq23(1) | |

| 11 | 2p22.1, 17q11.2 | ||

| 12 | 6p23 (1), 11p15.3-p15.4, 13q34 | ||

| 13 | 19p13.3-pter | 2q11.2, 2q35, 8p21.3, 11p15.3-p15.4, 11p13, 11q12-q13, 11q23.2, 14q11.2, 17qtel | |

| 14 | 2p21, 10q21.3-q22.1, 11p15.3-p15.4, 15q15, 17p13.3 | ||

| 15 | 20 | 4p13, 7q36, 11p13, 11q12-q13, 14q11.2, 17qtel, 20p11, 20q13.1 | |

| 16 | |||

| 17 | 3q26.2, 5q33.2, 10q26.2, 13q32, 13q34, 15q15 | ||

| 18 | 9q32-qter | ||

| 19 | 3q12-qter, 7p11.2-pter, 7q11.2-q31, 8q24.1-qter | 3q21-q29, 7p12-p14, 7p22, 7q11, 7q21-q31, 9q34, 10q26.3, 11p15.2 (1), 15q11.2, 18p11.21 | |

| 20 | 3q27-qter | 3q26.3-q27, 4p16.3, 9q31 | |

*Bolded text denotes regions found by both CGH and aCGH.

†(1) signifies that an isolated BAC, i.e. locus, showed gain or loss.

The first description of aCGH demonstrated its utility by measuring copy number changes along chromosome 20 in breast cancer cell lines and primary tumors. 5 Using an array spanning 7 Mb of chromosome 22 with 90% coverage, aCGH methodology has been shown to be useful for rapid and comprehensive detection of heterozygous and/or homozygous deletions as small as 40 kb at the NF2 locus. 18 Another report of the utility of the aCGH technology for the detection of gene amplifications in glioblastomas and nasopharyngeal carcinomas has recently been published. 19,20 The targets spotted on the array they describe were BAC clones containing 58 oncogenes commonly amplified in various human cancers compared to the array used in this study, which covers the whole genome.

In the first report of aCGH being used to analyze DNA from paraffin-embedded tissue, the DNA required amplification by DOP-PCR. 8 The arrays were similar to those used by Hui and colleagues, 19,20 consisting of oncogenes, and therefore not well suited for detection of deletions. We have established that in this tumor cohort direct random-prime labeling of DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded tissue yields quantitative data (ie, good signal to noise) and gives results comparable to established techniques such as CGH. This is important because it eliminates the expense and labor of PCR as well as eliminating the introduction of copy number artifacts resulting from amplification bias. A female-male control hybridization (Figure 1) ▶ only resulted in 0.3% false copy number calls (six false gains and zero false losses). The robustness of our labeling and extraction techniques is demonstrated here by our success with the analysis of prostate tissue that is inherently heterogeneous in nature (ie, comprised of normal, mixed grade tumor, and stroma). Additionally, we showed that these techniques work well on arrays that contain greater than 2000 BACs spanning the entire genome and we show that our technique allows detection of single copy number gains and losses.

Verification of CNAs with techniques such as CGH and QuMA is important because prostate tumors are inherently heterogeneous and we are using DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded tissue. The aCGH technology was able to reproduce and extend the findings from CGH. With our analytical criteria, we detected ∼80% of the CNAs found by CGH. On closer examination of the aCGH profiles, we were 90% concordant with the CGH results. For all of the discordant loci, the aCGH change fell below our log2 ratio cutoff value and also occurred in a region where few BACs were represented either because of poor printing on that array or a poor hybridization. A stringent log2 ratio cutoff value of 0.5 was intentionally, but arbitrarily selected (∼0.5 = gain of one copy and −1.0 = loss of one copy) to determine amplification or deletion of DNA.

A significant number of new CNAs were identified because of the very high resolution of aCGH (Table 1) ▶ . Some of these changes involved only single BAC clones implying an interval size of ∼1 Mb. Focal changes involving single BAC clones could be because of clone mismapping. Based on validation experiments, it has been estimated that less than 1% of clones on our array are mismapped. 7 These mismapped clones were not included in our analysis and therefore were not the reason for the focal changes. We are currently generating data on CNAs for a large cohort of samples to elucidate which aCGH changes are recurrent and therefore likely to contribute to tumor biology. However, it should be noted that some changes that were only observed for a single BAC (ie, locus) with aCGH in the present study had also been picked up by conventional CGH (for example, Table 1 ▶ , sample 3). Several of the focal changes correspond to loci that have been reported in the literature to be involved in prostate cancer, 6q26, 7q33, 13q12, 18q22, and Xq27-q28 (samples 13, 10, 2, 3, and 9, respectively). 9,21-24 Additionally, the log2 ratios for each BAC are calculated from signals from three separate spots on the array. Also, the fact that our protocol does not include amplification of tumor DNA means that artifactual signal is unlikely.

Genetic linkage mapping of a putative familial prostate cancer locus to 16q and the presence of deletions in ∼50% of prostate tumors at 16q23-qter suggests that this region harbors candidate gene(s) involved in prostate cancer. 25-27 Two of the samples in this study showing 16q loss by aCGH were analyzed with the QuMA assay for markers encompassing the 16q24-qter region. With QuMA, the copy number of a test locus is assessed using quantitative, real-time PCR, and related to a pooled reference to detect copy number gains or losses of DNA. 17 The results are shown in Table 2 ▶ . Both samples indeed show a decrease in copy number along the long arm of chromosome 16. Independent validation using the QuMA gave results concordant with the aCGH loss seen on the long arm of chromosome 16. This assay served as an additional tool to independently verify tumors that were identified by aCGH to have 16q loss.

Table 2.

QuMA Results

| Marker name | Relative loci copy number* | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | |

| D16S515 | 0.79 | 1.14 |

| D16S504 | 0.82 | 1.08 |

| D16S402 | 0.37 | 0.58 |

| WFDC1 3/4 exon | 0.80 | 1.03 |

| D16S3026 | 1.13 | 1.15 |

| Control primers | 2.0 | 2.0 |

*Values less than 1.25 signify loss. 17

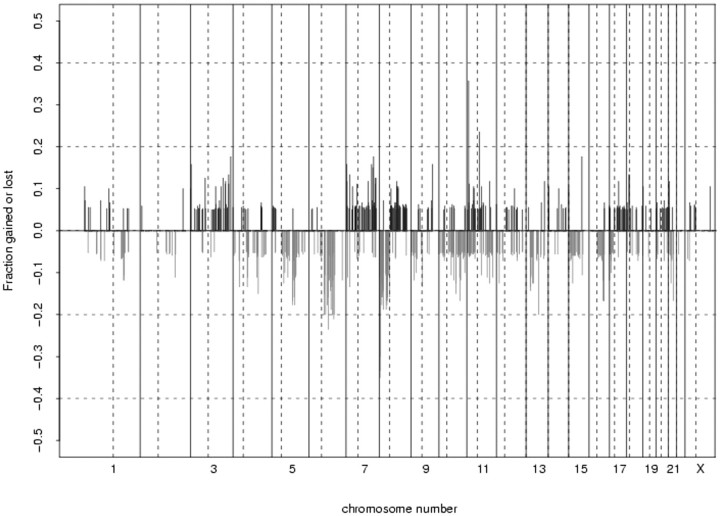

The changes in copy number for all samples are displayed as a frequency plot in Figure 3 ▶ . For each BAC clone on the array, the fraction of samples that showed either gain or loss was plotted as frequency with the log2 ratio threshold arbitrarily set at 0.5. Clones that were present in less than 50% of the samples were excluded. In this small set of tumors, recurrent amplifications included 3p25 and 8q22.2. A gene known as CHL1 (cell adhesion molecule) maps to 3p25 and the matrix metalloproteinase 16 gene (MMP16) maps to 8q22.2. The 6q15 locus was frequently deleted. There are currently no known genes mapping to this region; however, 6q16.3-q21 loss has been reported in prostate tumors. 28 The short arm of chromosome 8 was frequently deleted for this group of tumors, specifically 8p23.2. This region has been previously reported as being commonly deleted in prostate cancer. 9,29-31 8p harbors several putative tumor suppressor genes including DLGAP2 (8p23.2) and CSMD1 (8p23.2).

Figure 3.

Frequency plot of copy number changes for all samples (n = 20) along the genome. For each BAC clone on the array, the fraction of samples that was either gained or lost was plotted (log2 ratio threshold set at 0.5). Clones that were present in <50% of the samples were excluded. Note various imbalances seen frequently in prostatic adenocarcinoma, such as loss of 6q, 8p, and 16q, or gain of 3q, 7pq, and 8q.

In this report, we have demonstrated the utility of archived tissue for aCGH in providing high-resolution detection of both deletions and amplifications using a straightforward protocol. Currently, we are pursuing copy number differences specific to clinical outcome by screening a cohort of 100 intermediate grade tumors for copy-number abnormalities using megabase resolution array CGH.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Colin Collins, Ph.D., UCSF Comprehensive Cancer Center, 2340 Sutter St., S-132, San Francisco, CA 94115. E-mail: collins@cc.ucsf.edu.

Supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grants EUR 97-1404 and DDHK 2002-2700) and the National Cancer Institute (Prostate Cancer SPORE CA89520).

The University of California at San Francisco and Erasmus Medical Center contributed equally to the study.

References

- 1.Bepler G, Gautam A, McIntyre LM, Beck AF, Chervinsky DS, Kim YC, Pitterle DM, Hyland A: Prognostic significance of molecular genetic aberrations on chromosome segment 11p15.5 in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2002, 20:1353-1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elo JP, Harkonen P, Kyllonen AP, Lukkarinen O, Vihko P: Three independently deleted regions at chromosome arm 16q in human prostate cancer: allelic loss at 16q24.1-q24.2 is associated with aggressive behavior of the disease, recurrent growth, poor differentiation of the tumor and poor prognosis for the patient. Br J Cancer 1999, 79:156-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kressner U, Inganas M, Byding S, Blikstad I, Pahlman L, Glimelius B, Lindmark G: Prognostic value of p53 genetic changes in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999, 17:593-599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sisley K, Rennie IG, Parsons MA, Jacques R, Hammond DW, Bell SM, Potter AM, Rees RC: Abnormalities of chromosomes 3 and 8 in posterior uveal melanoma correlate with prognosis. Genes Chromosom Cancer 1997, 19:22-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinkel D, Segraves R, Sdar D, Clark S, Poole I, Kowbel D, Collins C, Kuo W-L, Chen C, Zhai Y, Dairkee SH, Ljung B-M, Gray JW, Albertson DG: High resolution analysis of DNA copy number variation using comparative genomic hybridization to microarrays. Nat Genet 1998, 20:207-211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wessendorf S, Fritz B, Wrobel G, Nessling M, Lampel S, Goettel D, Kuepper M, Joos S, Hopman T, Kokocinski F, Dohner H, Bentz M, Schwaenen C, Lichter P: Automated screening for genomic imbalances using matrix-based comparative genomic hybridization. Lab Invest 2002, 82:47-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snijders AM, Nowak N, Segraves R, Blackwood S, Brown N, Conroy J, Hamilton G, Hindle AK, Huey B, Kimura K, Law S, Myambo K, Palmer J, Ylstra B, Yue JP, Gray JW, Jain AN, Pinkel D, Albertson DG: Assembly of microarrays for genome-wide measurement of DNA copy number. Nat Genet 2001, 29:263-264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daigo Y, Chin SF, Gorringe KL, Bobrow LG, Ponder BA, Pharoah PD, Caldas C: Degenerate oligonucleotide primed-polymerase chain reaction-based array comparative genomic hybridization for extensive amplicon profiling of breast cancers: a new approach for the molecular analysis of paraffin-embedded cancer tissue. Am J Pathol 2001, 158:1623-1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alers JC, Rochat J, Krijtenburg PJ, Hop WCJ, Kranse R, Rosenberg C, Tanke HJ, Schröder FH, van Dekken H: Identification of genetic markers for prostate cancer progression. Lab Invest 2000, 80:931-942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alers JC, Krijtenburg PJ, Vis AN, Hoedemaeker RF, Wildhagen MF, Hop WCJ, van der Kwast TH, Schröder FH, Tanke HJ, van Dekken H: Molecular cytogenetic analysis of prostatic adenocarcinomas from screening studies: early cancers may contain aggressive genetic features. Am J Pathol 2001, 158:399-406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermanek P, Hutter RVP, Sobin LH: TNM Atlas IUAC ed 4 1997. Springer, New York

- 12.Gleason DF: Histologic grading of prostate cancer: a perspective. Hum Pathol 1992, 23:273-279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alers JC, Krijtenburg PJ, Rosenberg C, Hop WCJ, Verkerk AM, Schröder FH, van der Kwast TH, Bosman FT, van Dekken H: Interphase cytogenetics of prostatic tumor progression: specific chromosomal abnormalities are involved in metastasis to the bone. Lab Invest 1997, 77:437-448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain AN, Tokuyasu TA, Snijders AM, Segraves R, Albertson DG, Pinkel D: Fully automatic quantification of microarray image data. Genome Res 2002, 12:325-332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alers JC, Krijtenburg PJ, Hop WCJ, Bolle WABM, Schröder FH, van der Kwast TH, Bosman FT, van Dekken H: Longitudinal evaluation of cytogenetic aberrations in prostatic cancer: tumours that recur in time display an intermediate genetic status between non-persistent and metastatic tumours. J Pathol 1998, 185:273-283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alers JC, Rochat J, Krijtenburg PJ, van Dekken H, Raap AK, Rosenberg C: Universal linkage system (ULS): an improved method for labeling archival DNA for comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosom Cancer 1999, 25:301-305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ginzinger DG, Godfrey TE, Nigro J, Moore DH, Suzuki S, Pallavicini MG, Gray JW: Measurement of DNA copy number at microsatellite loci using quantitative PCR analysis. Cancer Res 2000, 60:5405-5409 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruder CE, Hirvela C, Tapia-Paez I, Fransson I, Segraves R, Hamilton G, Zhang XX, Evans DG, Wallace AJ, Baser ME, Zucman-Rossi J, Hergersberg M, Boltshauser E, Papi L, Rouleau GA, Poptodorov G, Jordanova A, Rask-Andersen H, Kluwe L, Mautner V, Sainio M, Hung G, Mathiesen T, Moller C, Pulst SM, Harder H, Heiberg A, Honda M, Niimura M, Sahlen S, Blennow E, Albertson DG, Pinkel D, Dumanski JP: High resolution deletion analysis of constitutional DNA from neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) patients using microarray-CGH. Hum Mol Genet 2001, 10:271-282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui AB, Lo KW, Yin XL, Poon WS, Ng HK: Detection of multiple gene amplifications in glioblastoma multiforme using array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Lab Invest 2001, 81:717-723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui AB, Lo KW, Teo PM, To KF, Huang DP: Genome wide detection of oncogene amplifications in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by array based comparative genomic hybridization. Int J Oncol 2002, 20:467-473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neville PJ, Conti DV, Paris PL, Levin H, Catalona WJ, Suarez BK, Witte JS, Casey G: Prostate cancer aggressiveness locus on chromosome 7q32–q33 identified by linkage and allelic imbalance studies. Neoplasia 2002, 4:424-431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nupponen NN, Hytinen ER, Kallioniemi AH, Visakorpi T: Genetic alterations in prostate cancer cell lines detected by CGH. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1998, 101:53-57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu W, Bubendorf L, Willi N, Moch H, Mihatsch MJ, Sauter G, Gasser TC: Genetic changes in clinically organ-confined prostate cancer by comparative genomic hybridization. Urology 2000, 56:880-885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu J, Meyers D, Freije D, Isaacs S, Wiley K, Nusskern D, Ewing C, Wilkens E, Bujnovszky P, Bova GS, Walsh P, Isaacs W, Schleutker J, Matikainen M, Tammela T, Visakorpi T, Kallioniemi OP, Berry R, Schaid D, French A, McDonnell S, Schroeder J, Blute M, Thibodeau S, Grönberg H, Emanuelsson M, Damber JE, Bergh A, Jonsson BA, Smith J, Bailey-Wilson J, Carpten J, Stephan D, Gillanders E, Amundson I, Kainu T, Freas-Lutz D, Baffoe-Bonnie A, Van Aucken A, Sood R, Collins F, Brownstein M, Trent J: Evidence for a prostate cancer susceptibility locus on the X chromosome. Nat Genet 1998, 20:175-179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Latil A, Cussenot O, Fournier G, Driouch K, Lidereau R: Loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 16q in prostate adenocarcinoma: identification of three independent regions. Cancer Res 1997, 57:1058-1062 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suarez BK, Lin J, Burmester JK, Broman KW, Weber JL, Banerjee TK, Goddard KA, Witte JS, Elston RC, Catalona WJ: A genome screen of multiplex sibships with prostate cancer. Am J Hum Genet 2000, 66:933-944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paris PL, Witte JS, Kupelian PA, Levin H, Klein EA, Catalona WJ, Casey G: Identification and fine mapping of a region showing a high frequency of allelic imbalance on chromosome 16q23.2 that corresponds to a prostate cancer susceptibility locus. Cancer Res 2000, 60:3645-3649 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srikantan V, Sesterhenn IA, Davis L, Hankins GR, Avallone FA, Livezey JR, Connelly R, Mostofi FK, McLeod DG, Moul JW, Chandrasekharappa SC, Srivastava S: Allelic loss on chromosome 6q in primary prostate cancer. Int J Cancer 1999, 84:331-335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cher ML, MacGrogan D, Bookstein R, Brown JA, Jenkins RB, Jensen RH: Comparative genomic hybridization, allelic imbalance, and fluorescence in situ hybridization on chromosome 8 in prostate cancer. Genes Chromosom Cancer 1994, 11:153-162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perinchery G, Bukurov N, Nakajima K, Chang J, Hooda M, Oh BR, Dahiya R: Loss of two new loci on chromosome 8 (8p23 and 8q12-13) in human prostate cancer. Int J Oncol 1999, 14:495-500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haggman MJ, Wojno KJ, Pearsall CP, Macoska JA: Allelic loss of 8p sequences in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and carcinoma. Urology 1997, 50:643-647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]