Abstract

Decorin is a small proteoglycan that binds to transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and inhibits its activity. However, its interaction with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), involved in arterial repair after injury, is not well characterized. The objectives of this study were to assess decorin-PDGF and decorin-PDGF receptor (PDGFR) interactions, the in vitro effects of decorin on PDGF-stimulated smooth muscle cell (SMC) functions and the in vivo effects of decorin overexpression on arterial repair in a rabbit carotid balloon-injury model. Decorin binding to PDGF was demonstrated by solid-phase binding and affinity cross-linking assays. Decorin potently inhibited PDGF-stimulated PDGFR phosphorylation. Pretreatment of rabbit aortic SMC with decorin significantly inhibited PDGF-stimulated cell migration, proliferation, and collagen synthesis. Decorin overexpression by adenoviral-mediated gene transfection in balloon-injured carotid arteries significantly decreased intimal cross-sectional area and collagen content by ∼50% at 10 weeks compared to β-galactosidase-transfected or balloon-injured, non-transfected controls. This study shows that decorin binds to PDGF and inhibits its stimulatory activity on SMCs by preventing PDGFR phosphorylation. Decorin overexpression reduces intimal hyperplasia and collagen content after arterial injury. Decorin may be an effective therapy for the prevention of intimal hyperplasia after balloon angioplasty.

Previous studies have shown that smooth muscle cell (SMC) activation and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition play important roles in intimal hyperplasia after balloon injury. 1,2 Coincident with an arterial injury, quiescent SMC are exposed to cytokines and growth factors that profoundly alter their behavior. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) is a potent growth factor produced by platelets, SMCs, and endothelial cells in the injured vessel wall. 3 It initiates a multitude of biological effects through the activation of intracellular signal transduction pathways that contribute to SMC proliferation, migration, and collagen synthesis. 3-5 The importance of PDGF in development of intimal hyperplasia has been established in arterial-injury models. 6,7

Decorin is a small proteoglycan that consists of a single glycosaminoglycan side chain linked to a core protein containing leucine-rich repeats of about 24 amino acids. 8,9 It is found in the ECM of a variety of tissues and cell types. 8,9 Decorin interacts with a variety of proteins that are involved in matrix assembly, 10 and in the regulation of fundamental biological functions such as cell attachment, 11 migration, 12 and proliferation. 13,14 Decorin inhibits cell proliferation in several cell types, including cancer cells. 13 It mediates its regulatory effects either directly by up-regulating cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors such as p21 and p27, or through its ability to interact with growth factors. 15,16 It is well established that decorin binds to TGF-β 17 and inhibits its biological activity in a number of cell types, including rat aortic SMCs. 16 However, it is not known whether decorin may also exert its regulatory effects by interacting with and modulating the activity of PDGF, another prominent growth factor involved in arterial repair. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to assess decorin-PDGF and decorin-PDGF receptor (PDGFR) interactions, the effects of decorin on PDGFR phosphorylation and PDGF-stimulated SMC functions in vitro, and effects of decorin overexpression on arterial repair in a rabbit carotid balloon-injury model that is characterized by PDGF up-regulation. 6,7

Materials and Methods

Decorin Binding to PDGF

Solid-solid-phase binding and affinity cross-linking assays were performed to assess PDGF and decorin interactions.

Solid-Phase Radioligand-Binding of 125I-PDGF to Decorin

Bovine articular cartilage decorin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was coated (1 μg/well) onto the surface of a 96-well plate (Nalge Nunc International, Denmark). 17 Nonspecific binding was blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in binding buffer for 3 hours at 37°C. Immobilized decorin was then allowed to bind to 4 × 10 4 cpm of 125I-PDGF-BB (Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ) in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of chondroitin sulfate (Sigma), BSA, or unlabeled PDGF-BB (R & D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN) as competitors. After a 6-hour incubation at 37°C, bound 125I-PDGF was solubilized in 0.3 mol/L NaOH, 1% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes and the radioactivity of each well was measured using a gamma counter (WALLAC, 1470 WIZARD). Nonspecific binding was determined by adding 100-fold excess unlabeled PDGF to the incubation mixture.

Affinity Cross-Linking of Decorin with PDGF and Immunoprecipitation Using Decorin Antibody

Decorin (1 μg) was mixed with PDGF-BB (0.01, 0.1, or 1.0 μg) in 200 μl of binding buffer 18 and incubated at 37°C for 3 hours. The proteins were then cross-linked with 0.3 mmol/L disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS; Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) at 37°C for 30 minutes and the reaction was terminated by adding TBS buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-base buffer, pH 8.0, 150 mmol/L NaCl). Cross-linked proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-decorin monoclonal antibody 6D6 19 (generous gift from Dr. Paul G. Scott, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta) using protein G sepharose (Amersham Biosciences Corp) at room temperature for 1 hour. The suspension was centrifuged and beads were washed four times with ice-cold TBS buffer. To recover specifically bound proteins, beads were suspended in 50 μl of 1X SDS-PAGE sample-loading buffer, mixed for 30 minutes at room temperature, and centrifuged. Proteins in 25 μl of supernatant were analyzed by 4 to 20% SDS and electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Decorin-PDGF complex was detected with anti-decorin and anti-PDGF antibodies as described below.

Immunoblotting of Decorin-PDGF Complex Using Decorin and PDGF Antibodies

The membrane was immunoblotted with anti-decorin monoclonal antibody 6D6. 19 Anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) was used for detection of primary antibody. The membrane was stripped and re-immunoblotted with goat anti-PDGF antibody (R & D Systems). Anti-goat IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz) was used for detection of primary antibody. Detection was performed using a chemiluminescence peroxidase detection system (Sigma) and exposure to BioMax film (Kodak).

In Vitro Studies

Cell Culture

Rabbit aortic SMC from passages 5 and 6 were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), supplemented with 2% penicillin-streptomycin and 10% fetal calf serum. For DNA synthesis and cell proliferation assays, cells were initially seeded at 5 × 10 4 per well into 24-well plates and at 10 4 per well into 96-well plates, respectively. For all other experiments, cells were grown to confluency. In each assay, cells were serum-starved for 48 hours and then pretreated for 30 minutes with the indicated concentration of decorin followed by treatment with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) for 24 hours.

PDGFR Expression

Confluent monolayers of cells were incubated in serum-free medium containing PDGF-BB in the presence or absence of decorin. After 24 hours of incubation period, cells were washed with PBS and lysed in 1X SDS-PAGE sample-loading buffer. Samples containing 50 μg of proteins were separated by 4 to 20% SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were immunoblotted with goat anti-human PDGFR-α or -β antibodies (R&D Systems). Anti-goat IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz) was used for detection of primary antibody and revealed using chemiluminescence detection system followed by autoradiography.

PDGFR β Phosphorylation

Confluent monolayers of cells were incubated in serum-free medium containing PDGF-BB in the presence or absence of decorin for 1 hour at 4°C. Cells were extracted as previously described. 20 Lysates were incubated at 4°C for 6 hours with 2 μg of goat anti-human PDGFR-β antibody and then 30 μl protein of G Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech) was added and mixed at 4°C overnight. Immunoprecipitated receptors were released from protein G pellets by boiling for 5 minutes in 1X SDS-PAGE sample-loading buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol and separated by 8% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and immunoblotted with anti-phosphotyrosine 4G10 monoclonal antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). Goat anti-mouse secondary antibody was used for detection of primary antibody. The membrane was stripped and re-immunoblotted with goat anti-human PDGFR-β antibody. Detection was performed using chemiluminescence detection system followed by autoradiography.

Binding of 125I-PDGF to Cells or PDGF Receptors

Cell binding assay and affinity cross-linking were performed as described previously. 18 Briefly, monolayers of confluent cells were washed three times with cold binding buffer and incubated in binding buffer for 30 minutes at 4°C. Confluent cells were pretreated for 30 minutes with decorin (30 μg/ml) in binding buffer, followed by adding 125I-PDGF (0.1 nmol/L). 125I-PDGF was also added to two other groups that were not pretreated with decorin. One group was given unlabeled PDGF (10 nmol/L) as a competitor to show specificity of the binding while the other group (control group) did not receive unlabeled PDGF. All groups were incubated at 4°C for 4 hours. Cells were then washed four times with binding buffer. For binding assay, cells were solubilized with 1X SDS-PAGE sample- loading buffer. The radioactivity of aliquots of soluble fractions was measured using a gamma counter. For affinity cross-linking assay, cells were cross-linked with DSS (0.3 mmol/L) at 4°C for 15 minutes and lysed in 1X SDS-PAGE sample-loading buffer. Soluble fractions containing 50 μg protein were analyzed by 4 to 12% SDS-PAGE. The gel was dried followed by autoradiography using BioMax film.

Cell Necrosis and Apoptosis

Cells were incubated in serum-free medium containing 30 μg/ml of decorin for 24 hours. For cell necrosis, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was measured in the medium using CytoTox 96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For cell apoptosis, cells were washed with PBS, lysed in 1X SDS-PAGE sample-loading buffer and centrifuged. Supernatants containing 50 μg protein were analyzed by 4 to 20% SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was immunoblotted with rabbit polyclonal anti-caspase-3 (CPP32) Ab-4 (NeoMarker, Fremont, CA). Anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz) was used for detection of primary antibody. The membrane was then stripped and re-immunoblotted with anti-mouse monoclonal anti-β actin antibody (Sigma). Goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Sigma) was used. Detection was performed using chemiluminescence detection system (Sigma) followed by autoradiography.

Growth Assays

For DNA synthesis, 1.0 μCi/ml of 3H-thymidine (Amersham) was added to the cultures 24 hours after treating cells with PDGF-BB in the presence or absence of decorin and incubated at 37°C for 6 hours. DNA synthesis was measured as previously described. 16 For cell proliferation, cells were incubated with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) in the presence and absence of decorin (20 μg/ml) for the indicated time periods and cell density was determined as described by Hou et al 21 Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5% toluidine blue in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes. Cells were rinsed in water twice and solubilized with 100 μl of 1% SDS. Absorbance was measured in a microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices) at 595 nm.

Migration Assay

Neuro Probe 48-well microchemotaxis chambers (Costar, Corning Inc., Corning, NY) with PVP-free polycarbonate filter (8.0 μm pore size) were used. The bottom well of the Boyden chamber was filled with 250 μl of serum-free medium containing PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml). Quiescent cells were trypsinized and resuspended in serum-free medium with or without decorin and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells (2 × 104) were then added to the upper well of the microchemotaxis chamber and incubated for 5 hours at 37°C. Cells that migrated to the lower side of the filters were fixed and stained with the Diff-Quick staining kit (VWR Laboratory). The filters were mounted on glass slides and counted by light microscopy using ×100 magnification. The results were expressed as number of migrated cells per high power field (HPF).

Collagen Synthesis Assay

Ascorbic acid (50 μg/ml) and 14C-proline (5 μCi/ml) were added to the cultures 24 hours after treating cells with PDGF-BB in the presence or absence of decorin and incubated at 37°C for 6 hours. Collagen synthesis was measured in the culture medium using a bacterial collagenase digestion method. 22

In Vivo Effects of Decorin Overexpression in Balloon-Injured Arteries

Carotid Artery Model

The animal experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines set out by the University of Toronto and approved by the St. Michael’s Hospital Animal Care Committee. A double-injury carotid artery model was done in 48 normolipemic male New Zealand White rabbits weighing 3.5 to 4.0 kg as previously described. 23 Both carotid arteries were injured with a 3.5-mm diameter balloon angioplasty catheter. At 3 weeks, a second balloon injury was performed. Immediately after second injury, the arteries were surgically exposed and the balloon-injured segments were temporarily isolated with ligatures. Gene transfer to these arterial segments was achieved using recombinant adenovirus vectors prepared by homologous recombination as previously described. 24 Briefly, a 1.5-kb rabbit decorin cDNA was cloned into the shuttle vector pCMVPLPA in which expression of the cDNA is driven by the CMV promoter. Recombination between this shuttle vector and the adenovirus 5 genomic vector pJM17 produced recombinant adenovirus encoding the decorin expression cassette. A control β-galactosidase encoding adenovirus was prepared similarly. In vivo gene transfer was achieved by injecting 10 9 pfu of adenovirus in a 100-μl volume into the vessel lumen to distend the balloon-injured arterial segment. Ligatures were positioned on either side of a 20-mm segment to prevent drainage and the volume was allowed to dwell for 20 minutes before repairing the arterial puncture and restoring perfusion. The contralateral artery was treated in a similar fashion. A third group underwent the two serial balloon injuries without gene transfection to serve as balloon-injured, non-transfected controls. The animals were sacrificed at three time points: 24 hours for transgene detection, 1 week for decorin immunostaining and cell proliferation, and 10 weeks for measurement of collagen content, intimal hyperplasia, and immunohistochemistry. At sacrifice, treated arteries were divided into two (15 mm and 5 mm) segments. The 15-mm segments were used for collagen measurement and the 5-mm segments were fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Arteries removed at 24 hours were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use.

Decorin Transgene Detection by PCR

DNA was extracted from rabbit carotid arteries using DNeasy Tissue kit (Qiagen Inc.). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mixture contained 35 pmol each of sense primer (GTA CGG TGG GAG GTC TAT AT) from the CMV promoter and antisense primer (CCA CTG AAC ACA GAT T) from the rabbit decorin gene. The inclusion of the CMV promoter sequence in the sense primer ensured specificity for identifying exogenous decorin cDNA. PCR was started by adding Master Mix (TaqPCR Master Mix kit, Qiagen, Inc) and carried out for 42 cycles with a denaturation step of 60 seconds at 94°C, an annealing step of 60 seconds at 57°C, and extension step of 105 seconds at 72°C. An aliquot of each sample was separated by 2.0% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Cell Proliferation

Proliferating cells in arteries at 1 week following balloon injury were identified by immunohistochemistry using anti-Mib-1 antibody 25 (1:500 dilution, DAKO Diagnostics). Mib-1-positive cells were counted in the intima, media, and adventitia of injured arteries using an image analysis system (Scion Image, Scion Corp) under ×20 magnification. Proliferation rates were expressed as total Mib-1-positive cells/arterial cross-section.

Assessment of Inflammation

Arterial cross-sections from both 1-week and 10-week animals were stained for the presence of neutrophils and macrophages. Mouse monoclonal antibodies against rabbit neutrophils (1:50 dilution, Serotec Inc., NC) and rabbit macrophages, RAM11 (1:50 dilution, Dako, CA) were used on paraffin-embedded sections and examined under light microscopy. The total number of neutrophils and macrophages were counted at ×40 magnification in two to three representative sections of each artery. The sections with the maximum number of neutrophils or macrophages were used for analysis.

Immunostaining for Decorin

Cross-sections from 1-week post-angioplasty arteries were immunostained with the anti-decorin antibody, at a dilution of 1:100.

Immunostaining for Fibronectin

Identification of fibronectin in 10-week post-angioplasty arteries was performed with a mouse monoclonal anti-human cellular fibronectin antibody (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, 1:50 dilution). Paraffin-embedded, formalin-fixed arterial cross-sections were treated by microwave heating for 10 minutes in citrate buffer and endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 0.6% hydrogen peroxide for 45 minutes. Large bowel was used as a positive control. Negative controls for the arterial sections were done with omission of the primary antibody. All slides were reviewed by one of the authors (J.B.) without knowledge of the treatment group. Each layer of the vessel wall was semi-quantitatively scored using a 0 (no staining) to 4 (intense staining) scale.

Morphometric Analysis

Serial cross-sections (four to five per vessel) were obtained from the treated arteries and stained with Movat-pentachrome stain. Computerized morphometry (Scion Image, Scion Corp) was performed to determine intimal cross-sectional area (CSA) and intimal thickness.

Collagen Content and Density Measurement

Collagen content was determined biochemically using a hydroxyproline assay as previously described. 2 Quantification of collagen density was performed in intima, media, and adventitia using picro sirius red staining and digital image microscopy with circularly polarized light as described by Sierevogel et al 26 In short, a picro sirius red image was converted into a gray value image. Regions of interest (ROI) were drawn to select the different arterial layers. The total amount of gray values in each layer was determined for collagen content. Collagen density, expressed as gray-values (arbitrary unit)/μm2, was calculated by dividing the collagen content in each layer by the cross-sectional area of this layer.

Statistical Analysis

All measurements are expressed as mean ± SD. Student’s t-test was used for comparison between two groups while analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for multiple comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

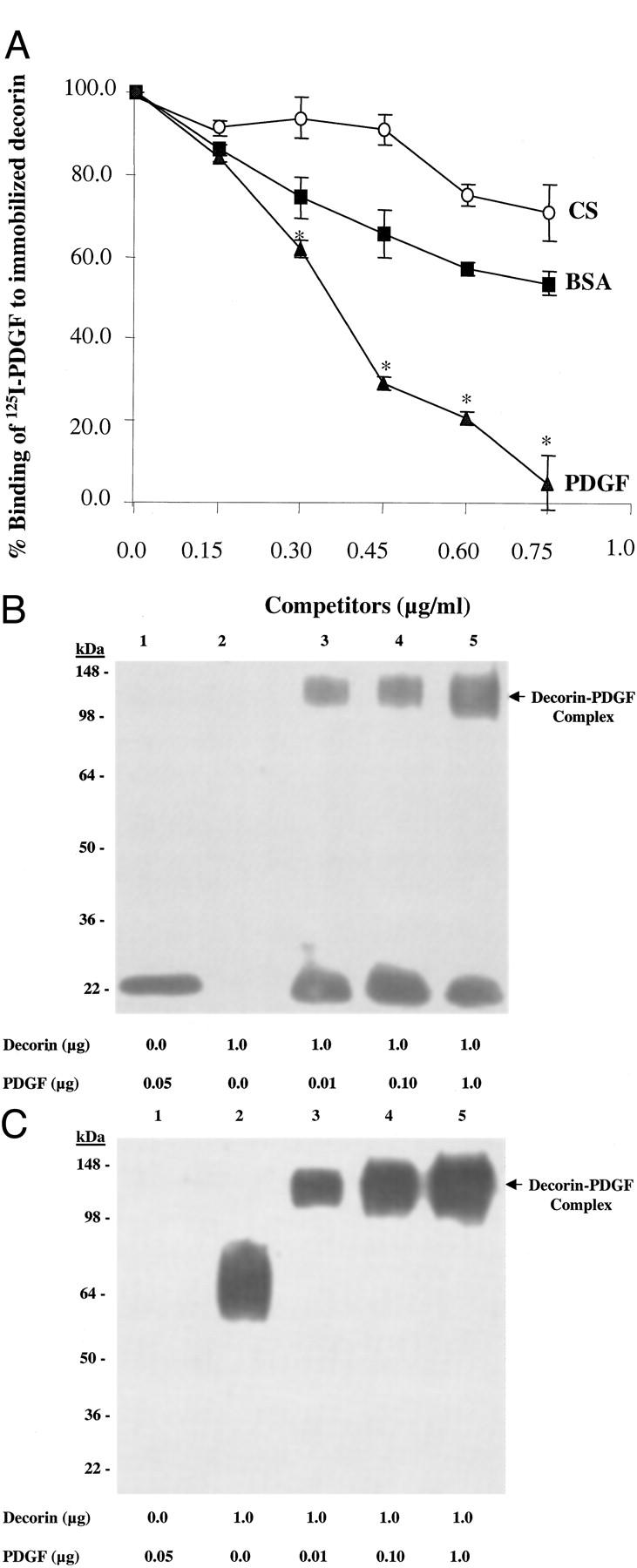

Decorin Binding to PDGF

In solid-phase binding assay, binding of 125I-PDGF to decorin was competed by chondroitin sulfate, BSA, and unlabeled PDGF (Figure 1A) ▶ . Unlabeled PDGF competed with labeled PDGF in a concentration-dependent manner, yielding half-maximal inhibitory concentration of about 0.37 μg/ml and displaced more than 95% of labeled PDGF at 0.75 μg/ml. In contrast, chondroitin sulfate or BSA did not reach half-maximal inhibition and at 0.75 μg/ml they displaced 20% and 40% of labeled PDGF, respectively. The higher binding affinity of PDGF for decorin indicates specificity of decorin binding to PDGF.

Figure 1.

A: Binding of 125I-PDGF to immobilized decorin. Data are mean ± SD of triplicate assays and are expressed as % binding of 125I-PDGF to immobilized decorin. In contrast to CS and BSA that did not reach half-maximal inhibition, unlabeled PDGF competed with 125I-PDGF dose dependently and reached half-maximal concentration of about 0.37 μg/ml indicating the specificity of decorin binding to PDGF. BSA, bovine serum albumin; CS, chondroitin sulfate. Experiments were repeated a minimum of three times. *, P < 0.01 versus CS and BSA. B and C: Western blot analysis of affinity cross-linked decorin with PDGF confirmed decorin-PDGF complex formation using PDGF (B) or decorin (C) antibody. A higher molecular weight band (arrow) which was only detected in the lanes with cross-linked proteins (B and C, lanes 3, 4, and 5), represents decorin-PDGF complex. The lower molecular weight bands in lane 1 of B and lane 2 of C correspond to PDGF and decorin only, respectively. Results were similar in three independent experiments.

SDS-PAGE of affinity cross-linked decorin with PDGF followed by immunoprecipitation using decorin antibody and detecting by Western blotting using PDGF (Figure 1B) ▶ or decorin (Figure 1C) ▶ antibody confirmed decorin-PDGF complex formation.

In Vitro Studies

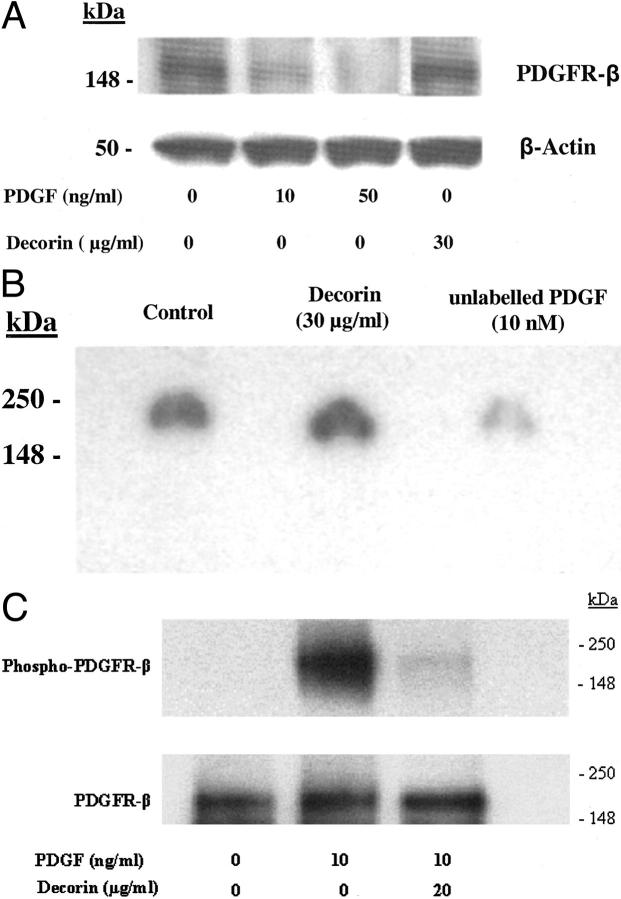

Effect of Decorin on PDGFR Expression

PDGFR-α was not detected in SMCs. PDGF down-regulated PDGFR-β expression in the presence or absence of decorin. Decorin did not affect PDGFR-β expression (Figure 2A) ▶ .

Figure 2.

A: Western blot analysis of PDGFR-β. PDGF inhibited PDGFR-β expression. Decorin did not affect PDGFR-β expression. B: Autoradiograph of a gel loaded with extracts containing 50 μg of protein from cells incubated with 125I-PDGF in the presence or absence of unlabeled PDGF or decorin. Decorin did not affect binding of 125I-PDGF to PDGF receptor. Unlabeled PDGF competed with 125I-PDGF and prevented its binding to receptors indicating specificity of binding. C: Western blot analysis of phospho-PDGFR-β. Decorin inhibited PDGF-stimulated PDGFR-β phosphorylation (top). Immunoblotting with anti-PDGFR-β shows (bottom) that similar amounts of receptor were present in all samples. Results were similar in three independent experiments.

Effect of Decorin on PDGF Binding to SMCs, Receptors

Binding of 125I-PDGF to SMCs was similar in the presence (1081 ± 161 cpm/well) or absence (1015 ± 48 cpm/well) of decorin. Unlabeled PDGF that was used as a positive control competed with 125I-PDGF and reduced its binding (454 ± 64 cpm/well) to the cells. Similar results were obtained for cross-linking assay (Figure 2B) ▶ where decorin did not prevent 125I-PDGF binding to receptors whereas unlabeled PDGF competed with labeled PDGF and reduced its binding to receptors. These results suggest that decorin does not prevent PDGF binding to cells or receptors.

PDGFR-β Phosphorylation

PDGF stimulated PDGFR-β phosphorylation which was almost completely inhibited by decorin (Figure 2C) ▶ .

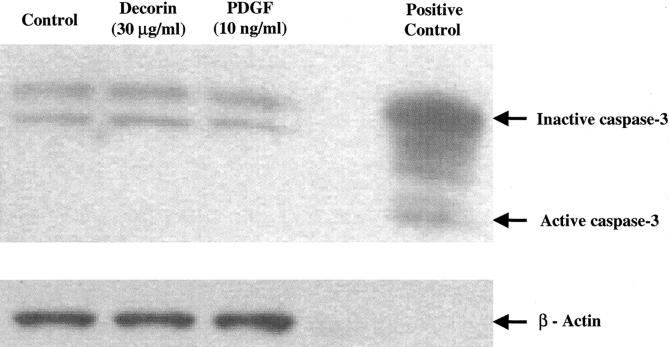

Effect of Decorin on Cell Necrosis and Apoptosis

LDH levels were similar in culture medium of decorin-treated cells and control non-treated or PDGF-treated cells (data not shown). There was also no evidence of active caspase-3 in decorin-treated, control non-treated or PDGF-treated cells in the cell apoptosis assay (Figure 3) ▶ .

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of caspase-3 after treating cells with decorin (30 μg/ml) or PDGF (10 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Each lane contains 50 μg of cellular proteins. Western blots were probed with anti-caspase-3 (top) or anti β-actin (bottom) to verify equal loading of protein in each lane. Positive control was from human Jurkat cells (tonsil). There was no evidence of cell apoptosis in decorin-treated cells as well as control non-treated or PDGF-treated cells. Results were similar in three independent experiments.

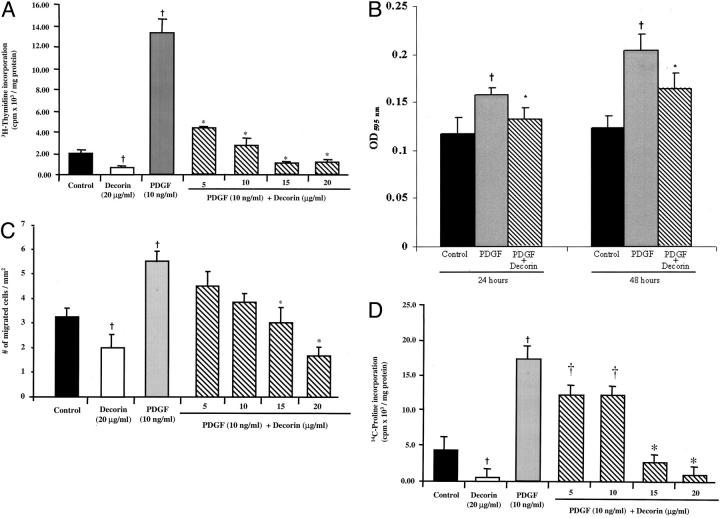

Effect of Decorin on DNA Synthesis and Cell Proliferation

Cells treated with PDGF showed a sixfold increase in DNA synthesis compared to control non-treated cells. Decorin inhibited PDGF-stimulated DNA synthesis in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4A) ▶ . To determine whether decorin had an effect on cell proliferation, the growth of SMCs were determined at 24 and 48 hours. Decorin significantly inhibited PDGF-stimulated cell proliferation at both time points (Figure 4B) ▶ .

Figure 4.

PDGF-stimulated (A) DNA synthesis, (B) cell proliferation, (C) cell migration, and (D) collagen synthesis were significantly inhibited by decorin in a dose-dependent manner. PDGF-stimulated cell proliferation was significantly inhibited by decorin at 24 hours and 48 hours. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated a minimum of three times. †, P < 0.01 versus control non-treated cells; *, P ≤ 0.02 versus PDGF-treated cells.

Effect of Decorin on Cell Migration

An approximately twofold increase was observed in cell migration for the PDGF-treated cells compared to control non-treated cells. Decorin caused a dose-dependent inhibition of PDGF-stimulated cell migration (Figure 4C) ▶ .

Effect of Decorin on Collagen Synthesis

A fourfold increase was observed in the rate of collagen synthesis for the PDGF-treated cells compared to control non-treated cells. Decorin caused a dose-dependent inhibition of PDGF-stimulated collagen synthesis (Figure 4D) ▶ .

In Vivo Studies

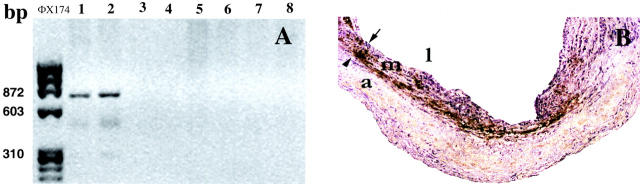

Detection of Decorin Transgene

At 24 hours following injury and gene transfection, a 870-bp decorin cDNA fragment was identified in the decorin-transfected arteries but not detected in injured β-gal-transfected, non-transfected injured or uninjured arteries (Figure 5A) ▶ .

Figure 5.

A: PCR of DNA from rabbit carotid arteries at 24 hours after transfection. Lanes 1 and 2: decorin-transfected arteries; lanes 3 and 4: β-gal-transfected arteries; lanes 5 and 6: injured non-transfected arteries; lanes 7 and 8: uninjured arteries and far left lane (ΦX174): DNA standards. In the decorin-transfected arteries, a 870-bp fragment was identified by using primers for the CMV promotor sequence and the rabbit decorin gene. B: Decorin (brown staining) demonstrated in medial layer by immunohistochemistry at 1 week after angioplasty and transfection. Arrowhead, external elastic lamina; arrow, internal elastic lamina; l, lumen; m, media; a, adventitia.

Decorin Immunostaining

At 1 week after balloon injury, decorin was detected in the media of decorin-transfected arteries (Figure 5B) ▶ , but not in β-gal-transfected, non-transfected injured or uninjured arteries.

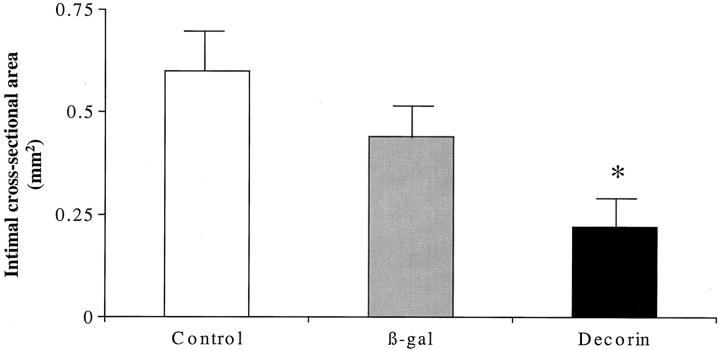

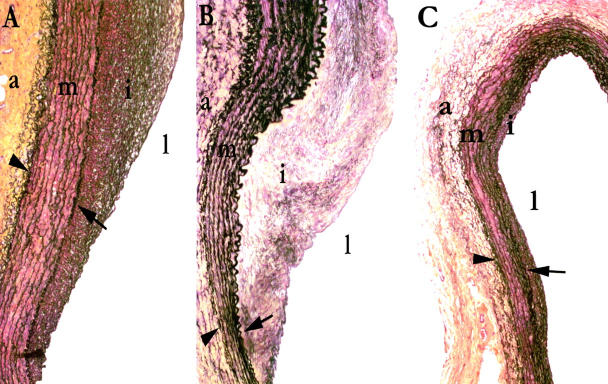

Intimal Hyperplasia

The intimal CSA was significantly reduced by ∼50% in decorin-transfected arteries (Figures 6 and 7) ▶ compared to β-gal-transfected and non-transfected injured control arteries (P < 0.04). Similarly, the maximum intimal thickness was also reduced by ∼50% in decorin-transfected (0.09 ± 0.03 mm) compared to β-gal-transfected (0.19 ± 0.15 mm) and non-transfected injured controls (0.17 ± 0.10 mm) (P < 0.04).

Figure 6.

Intimal cross-sectional area at 10 weeks after angioplasty. *, P < 0.04 versus β-gal and control.

Cell Proliferation

The cell proliferation rates at 1 week post-angioplasty were not significantly different between the three groups (decorin-transfected arteries: 10 ± 8; β-gal-transfected 14 ± 7; non-transfected injured: 9 ± 5 Mib-1-positive cells/arterial cross-section). In addition, the cellular proliferation rates were also similar for the three (intima, media, and adventitia) layers of the vessel wall between groups.

Inflammation and Cellular Infiltrate

Lack of active inflammation at both time points (1 week and 10 weeks) was evident by an absence of neutrophils or macrophages in the majority of treated arteries. In only one β-gal-transfected artery at 10 weeks, six macrophages were present. Four neutrophils were detected in one decorin-transfected artery at 1 week.

Collagen Content and Density

At 10 weeks, there was a significant decrease in collagen content in decorin-transfected arteries compared to β-gal-transfected and injured, non-transfected arteries, (228 ± 98 versus 343 ± 109 and 411 ± 331 μg hydroxyproline/arterial segment, respectively, P < 0.03). Based on the relationship between collagen content and intimal area, the decrease in collagen content in the decorin-treated arteries appeared to be proportional to the reduction in intimal area. This was supported by the collagen density data. There was no statistically significant difference in collagen density between the three groups in the adventitia (decorin: 101 ± 30 gray values/μm2; injured, non-transfected: 107 ± 23 gray values/μm2; β-gal: 97 ± 21 gray values/μm2) or the intima (decorin: 5.9 ± 1.9 gray values/μm2; injured, non-transfected: 5.7 ± 4.2 gray values/μm2; β-gal 7.7 ± 5.4 gray values/μm2).

Fibronectin Immunostaining

At 10 weeks, there was intense staining in the adventitia in all three groups with no or mild intimal staining in all three groups. There were no statistical differences in the intimal staining (decorin: 0.33±.55; injured, non-transfected 0.78±.83; β-gal: 0.92±.80).

Discussion

PDGF is released after arterial injury and plays an important role in regulating cellular and extracellular responses in vascular repair. 27 It has also been implicated in the development of intimal hyperplasia following angioplasty 3,27 and post-transplant arteriopathy. 28 Previous studies have shown that targeting PDGF with anti-PDGF antibody 29 or its receptor expression with antisense oligonucleotides 30 reduces intimal hyperplasia. We now report for the first time that decorin protein has a potent and dose-dependent inhibitory effect on PDGF stimulation of three major SMC functions including cell proliferation, migration, and collagen synthesis. Only one study 16 has examined the effects of decorin on PDGF-stimulated SMC proliferation and did not show a prolonged inhibitory effect. This discrepancy may be due to different experimental conditions and models used. We have also shown in an animal arterial balloon-injury model characterized by PDGF up-regulation that decorin significantly inhibited intimal hyperplasia and collagen accumulation. It seems reasonable to conclude that the inhibitory effects of decorin demonstrated in the in vivo study are at least in part due to decorin neutralization of PDGF activity.

The inhibitory effect of decorin on PDGF-stimulated SMC functions was not due to cell apoptosis or necrosis. The novel mechanisms of decorin interactions with PDGF in our study were direct decorin binding to PDGF and acting as a potent inhibitor of PDGF receptor phosphorylation in response to PDGF. There was no effect on PDGF receptor-β expression. The specificity of decorin binding to PDGF was demonstrated by a solid-phase binding assay in which unlabeled PDGF competed with 125I-PDGF for binding to decorin. This was also confirmed by affinity cross-linking using both PDGF and decorin antibodies which indicated PDGF binding to decorin in a concentration-dependent manner.

Despite important regulatory effects on ECM deposition, decorin expression is not up-regulated in human coronary restenosis specimens 31 or after balloon injury in animal models, 32 a finding confirmed in the present study in the β-gal-transfected and the injured, non-transfected arteries. In decorin-transfected arteries, there was decorin expression evident at 1 week after transfection and a marked reduction in intimal cross-sectional area at 10 weeks. Since intimal area was reduced without a change in cell proliferation, reduced collagen content (50% compared to β-gal-transfected and 80% compared to injured non-transfected arteries) appears to be a mechanism responsible for the inhibition of intimal thickening by decorin. This conclusion is also supported by in vitro results that showed complete inhibition of collagen synthesis in SMCs. An anti-fibrotic effect of decorin has been previously demonstrated in experimental lung 33 and glomerulonephritis models. 34 This is the first report of an anti-fibrotic effect of decorin overexpression in a vascular-injury model. In a rat carotid balloon-injury model, Fischer et al 32 showed that cell-mediated decorin transfection decreased neointimal volume and increased intimal collagen density, based only on immunostaining. In contrast, our studies using a quantitative measurement of collagen content and collagen density showed decreased collagen content with no significant differences in collagen density in the intima or the adventitia. Moreover, we did not find any significant differences in fibronectin immunostaining in the intima between the three groups. This suggests that the intimal extracellular matrix is not qualitatively different between the decorin-transfected and the two control groups.

The mechanism by which decorin regulates ECM and exerts its anti-fibrotic effect is not clearly known. Previous studies have shown that decorin binds to TGF-β 17 and inhibits its activity in vitro 16 and in vivo. 33,35 Decorin-PDGF binding and inhibition of PDGFR phosphorylation by decorin reported in this study indicate an additional mechanism of ECM regulation by decorin. Decorin is also known to bind to collagen 36-38 and inhibit collagen fibrillogenesis. 39 These diverse effects of decorin make it an attractive therapeutic agent for several pathological arterial conditions characterized by intimal hyperplasia.

In conclusion, our study shows a novel interaction of decorin with PDGF, based on decorin-PDGF complex formation and inhibition of PDGF-stimulated PDGFR phosphorylation and SMC activities. Decorin overexpression significantly reduced both intimal hyperplasia and collagen content after balloon injury, demonstrating a potent beneficial anti-fibrotic effect for decorin.

Figure 7.

Movat-pentachrome-stained sections of injured carotid arteries at 10 weeks after angioplasty. A: Control (injured non-transfected). B: β-gal-transfected. C: Decorin-transfected. Marked inhibition of intimal hyperplasia seen in decorin-transfected arteries. Arrowhead, external elastic lamina; arrow, internal elastic lamina; l, lumen; i, intima; m, media; a, adventitia.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Bradley Strauss, Terrence Donnelly Heart Centre, Division of Cardiology, St. Michael’s Hospital, 30 Bond Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5B 1W8. E-mail: straussb@smh.toronto.on.ca.

Supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario and dedicated to the memory of Robyn Strauss Albert.

N. N. and A. N. C. contributed equally to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Schwartz R, Holmes D, Topol E: The restenosis paradigm revisited: an alternate proposal for cellular mechanisms. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992, 20:1284-1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strauss BH, Chisholm RJ, Keeley FW, Gotlieb AI, Logan RA, Armstrong PW: Extracellular matrix remodeling after balloon-angioplasty injury in a rabbit model of restenosis. Circ Res 1994, 75:650-658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jawien A, Bowen-Pope DF, Lindner V, Schwartz SM, Clowes AW: Platelet-derived growth factor promotes smooth muscle migration and intimal thickening in a rat model of balloon angioplasty. J Clin Invest 1992, 89:507-511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang B, Yamamura S, Nelson PR, Mureebe L, Kent KC: Differential effects of platelet-derived growth factor isotypes on human smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration are mediated by distinct signaling pathways. Surgery 2000, 120:427-431432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amento EP, Ehsani N, Palmer H, Libby P: Cytokines and growth factors positively and negatively regulate interstitial collagen gene expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb 1991, 11:1223-1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyauchi K, Aikawa M, Tani T, Nakahara K, Kawai S, Nagai R, Okada R, Yamaguchi H: Effect of probucol on smooth muscle cell proliferation and dedifferentiation after vascular injury in rabbits: possible role of PDGF. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1998, 12:251-260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majesky M, Reidy M, Bowen-Pope D, Hart C, Wilcox J, Schwartz S: PDGF ligand and receptor gene expression during repair of arterial injury. J Cell Biol 1990, 111:2149-2158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hocking A, Shinomura T, McQuillan D: Leucine rich repeat glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix. Matrix Biol 1998, 17:1-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krusius T, Ruoslathi E: Primary structure of an extracellular matrix proteoglycan core protein deduced from cloned cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1986, 83:7683-7687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thieszen S, Rosenquist T: Expression of collagens and decorin during aortic arch artery development: implications for matrix pattern formation. Matrix Biol 1995, 14:573-582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merle B, Malaval L, Lawler J, Delmas P, Clezardin P: Decorin inhibits cell attachment to thrombospondin-1 by binding to a KKTR-dependent cell adhesive site present within the N-terminal domain of thrombospondin-1. J Cell Biochem 1997, 67:75-83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merle B, Durussel L, Delmas PD, Clezardin P: Decorin inhibits cell migration through a process requiring its glycosaminoglycan side chain. J Cell Biochem 1999, 75:538-546 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamaguchi Y, Ruoslahti E: Expression of human proteoglycan in Chinese hamster ovary cells inhibits cell proliferation. Nature 1988, 336:244-246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nash MA, Loercher AE, Freedman RS: In vitro growth inhibition of ovarian cancer cells by decorin: synergism of action between decorin and carboplatin. Cancer Res 1999, 59:6192-6196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Luca A, Santra M, Baldi A, Giordano A, Iozzo RV: Decorin-induced growth suppression is associated with up-regulation of p21, an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases. J Biol Chem 1996, 271:18961-18965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer J, Kinsella M, Levkau B, Clowes A, Wight T: Retroviral overexpression of decorin differentially affects the response of arterial smooth muscle cells to growth factors. Arterioscle Thromb Vasc Biol 2001, 21:777-784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hildebrand A, Romaris M, Rasmussen L, Heinegard D, Twardzik D, Border W, Ruoslahti E: Interaction of the small interstitial proteoglycans biglycan, decorin, and fibromodulin with transforming growth factor β. Biochem J 1994, 302:527-534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaname S, Ruoslahti E: Betaglycan has multiple binding sites for transforming growth factor-β 1. Biochem J 1996, 315:815-820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott P, Dodd C, Pringle G: Mapping the locations of the epitopes of five monoclonal antibodies to the core protein of dermatan sulfate proteoglycan II (decorin). J Biol Chem 1993, 268:11558-11564 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baxter RM, Secrist JP, Vaillancourt RR, Kazlauskas A: Full activation of the platelet-derived growth factor β-receptor kinase involves multiple events. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:17050-17055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou G, Mulholland D, Gronska MA, Bendeck MP: Type VIII collagen stimulates smooth muscle cell migration and matrix metalloproteinase synthesis after arterial injury. Am J Pathol 2000, 156:467-476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulik TJ, Alvarado SP: Effect of stretch on growth and collagen synthesis in cultured rat and lamb pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol 1993, 157:615-624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barolet AW, Nili N, Cheema A, Robinson R, Natarajan MK, O’Blenes S, Li J, Eskandarian MR, Sparkes J, Rabinovitch M, Strauss BH: Arterial elastase activity after balloon angioplasty and effects of elafin, an elastase inhibitor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001, 21:1269-1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giordano FJ, He H, McDonough P, Meyer M, Sayen MR, Dillmann WH: Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer reconstitutes depressed sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase levels and shortens prolonged cardiac myocyte Ca2+ transients. Circulation 1997, 96:400-403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aoyagi M, Yamamoto M, Wakimoto H: Immunohistochemical detection of Ki-67 in replicative smooth muscle cells of rabbit carotid arteries after balloon denudation. Stroke 1995, 26:2328-2331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sierevogel MJ, Velema E, van der Meer FJ, Nijhuis MO, Smeets M, de Kleijn DP, Borst C, Pasterkamp G: Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition reduces adventitial thickening and collagen accumulation following balloon dilation. Cardiovasc Res 2002, 55:864-869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leppanen O, Janjic N, Carlsson MA, Pietras K, Levin M, Vargeese C, Green LS, Bergqvist D, Ostman A, Heldin CH: Intimal hyperplasia recurs after removal of PDGF-AB and -BB inhibition in the rat carotid artery-injury model. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000, 20:E89-E95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Groot-Kruseman HA, Baan CC, Mol WM, Niesters HG, Maat AP, Balk AH, Weimar W: Intragraft platelet-derived growth factor-α and transforming growth factor-β1 during the development of accelerated graft vascular disease after clinical heart transplantation. Transpl Immunol 1999, 7:201-205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rutherford C, Martin W, Salame M, Carrier M, Anggard E, Ferns G: Substantial inhibition of neo-intimal response to balloon injury in the rat carotid artery using a combination of antibodies to platelet-derived growth factor-BB and basic fibroblast growth factor. Atherosclerosis 1997, 130:45-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sirois MG, Simons M, Edelman ER: Antisense oligonucleotide inhibition of PDGFR-β receptor subunit expression directs suppression of intimal thickening. Circulation 1997, 95:669-676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riessen R, Isner J, Blessing E, Loushin C, Nikol S, Wight T: Regional differences in the distribution of the proteoglycans biglycan and decorin in the extracellular matrix of atherosclerotic and restenotic human coronary arteries. Am J Pathol 1994, 144:962-974 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer J, Kinsella M, Clowes M, Lara S, Clowes A: Local expression of bovine decorin by cell-mediated gene transfer reduces neointimal formation after balloon injury in rats. Circ Res 2000, 86:676-683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giri S, Hyde D, Braun R, Gaarde W: Antifibrotic effect of decorin in a bleomycin hamster model of lung fibrosis. Biochem Pharmacol 1997, 54:1205-1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Border W, Noble N, Yamamoto T, Harper J: Natural inhibitor of transforming growth factor-β protects against scarring in experimental kidney disease. Nature 1992, 360:361-364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isaka Y, Brees D, Ikegaya K, Kaneda Y, Imai E, Noble N: Gene therapy by skeletal muscle expression of decorin prevents fibrotic disease in rat kidney. Nat Med 1996, 2:418-423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schonherr E, Hausser H, Beavan L, Kresse H: Decorin-type I collagen interaction: presence of separate core protein-binding domains. J Biol Chem 1995, 270:8877-8883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bidanset DJ, Guidry C, Rosenberg LC, Choi HU, Timpl R, Hook M: Binding of the proteoglycan decorin to collagen type VI. J Biol Chem 1992, 267:5250-5256 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keene DR, San Antonio JD, Mayne R, McQuillan DJ, Sarris G, Santoro SA, Iozzo RV: Decorin binds near the C terminus of type I collagen. J Biol Chem 2000, 275:21801-21804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neame PJ, Kay CJ, McQuillan DJ, Beales MP, Hassell JR: Independent modulation of collagen fibrillogenesis by decorin and lumican. Cell Mol Life Sci 2000, 57:859-863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]