Abstract

Many adhesion molecule pathways have been invoked as mediating leukocyte recruitment during immune complex-induced inflammation. However the individual roles of these molecules have not been identified via direct visualization of an affected microvasculature. Therefore, to identify the specific adhesion molecules responsible for leukocyte rolling and adhesion in immune complex-dependent inflammation we used intravital microscopy to examine postcapillary venules in the mouse cremaster muscle. Wild-type mice underwent an intrascrotal reverse-passive Arthus model of immune complex-dependent inflammation and subsequently, leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions and P- and E-selectin expression were assessed in cremasteric postcapillary venules. At 4 hours, the reverse-passive Arthus response induced a significant reduction in leukocyte rolling velocity and significant increases in adhesion and emigration. P-selectin expression was increased above constitutive levels whereas E-selectin showed a transient induction of expression peaking between 2.5 to 4 hours and declining thereafter. While E-selectin was expressed, rolling could only be eliminated by combined blockade of P- and E-selectin. However, by 8 hours, all rolling was P-selectin-dependent. In contrast, inhibition of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 had a minimal effect on leukocyte rolling, but significantly reduced both adhesion and emigration. These observations demonstrate that immune complex-mediated leukocyte recruitment in the cremaster muscle involves overlapping roles for the endothelial selectins and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

It is now well recognized that for leukocytes to gain entry into inflamed sites, they must first undergo a precise sequence of interactions with the endothelium lining the vasculature at the site of inflammation. Initially leukocytes must tether and roll along the endothelial surface, before undergoing adhesion in response to activating stimuli, and emigrating out of the vasculature. In general each of these steps is mediated by specific families of adhesion molecules expressed by both leukocytes and endothelial cells. The tethering and rolling steps are mediated by members of the selectin family (P- and E-selectin on endothelial cells, L-selectin on leukocytes) and the α4-integrin expressed on specific leukocyte populations. 1-5 Leukocyte adhesion is mediated by interaction of the leukocyte integrins including the β2 and α4 integrins, with their respective endothelial ligands, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1). 6 Although there is significant evidence supporting the overall basis of this paradigm, the precise combination of adhesion molecules used in each response is highly diverse, and varies according to the type of response and the tissue examined.

One type of inflammatory response in which the adhesion molecules responsible for leukocyte recruitment have not been fully characterized is immune complex (IC)-induced inflammation. ICs are thought to play critical roles in several immunological diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, and rheumatoid arthritis. One of the mechanisms whereby ICs induce tissue injury is via their potent ability to induce leukocyte recruitment. The molecular mechanisms of IC-induced leukocyte recruitment have been examined in diverse tissues such as the lung, skin, and kidney, with correspondingly diverse results. Blockade of leukocyte β2 integrins has been consistently observed to attenuate IC-induced leukocyte recruitment, presumably via inhibition of the adhesion step. 7-9 However, analysis of the molecules responsible for the initial contact between the leukocytes and endothelial cells, ie, tethering and rolling, has generated less consistent data. In the lung, reagents that inhibit E-selectin and L-selectin, but not P-selectin, are effective in reducing IC-induced leukocyte recruitment. 10-12 Conversely in the skin, all three (P-, E-, and L-) selectins have been implicated in the response, 10,13,14 and in the kidney in models of IC-mediated glomerulonephritis, a role has been observed for P-selectin but not E-selectin. 9,15 Finally, a recent study has raised the possibility that ICs themselves may be capable of initiating contact between leukocytes moving rapidly in flowing blood and activated endothelial cells lining the microvasculature. 16

In many of these studies, more than one molecule has been implicated as mediating leukocyte rolling, although it remains unclear how these multiple rolling molecules interact to mediate recruitment. The existing studies have been hampered by the lack of direct visualization of the affected microvasculature. As leukocyte-endothelial interactions occur under the dynamic conditions of microvascular blood flow and involve interactions between moving and static cell populations, to accurately define roles of individual molecules it is necessary to directly visualize these interactions in vivo under normal blood flow conditions. Therefore the aim of these studies was to examine the functional adhesion molecule pathways in IC-induced leukocyte recruitment, by directly examining the affected microvasculature. To achieve this aim we applied the well-characterized reverse-passive Arthus (RPA) response to the mouse cremaster muscle, and examined the affected microvasculature using intravital microscopy. Using this approach we observed P-selectin-dependent rolling consistently throughout the first 8 hours of the RPA response, in addition to a period of overlapping E-selectin-dependent rolling between 2 to 5 hours after initiation of the RPA response. Furthermore, we observed that VCAM-1 played a critical role in the subsequent steps of adhesion and emigration.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were bred in-house at Monash University or purchased from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Melbourne, Australia, and housed in conventional conditions. P-selectin−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background were supplied by The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, and housed in specific pathogen-free conditions.

Antibodies

The antibodies used in this study were polyclonal rabbit anti-OVA (anti-OVA) antibody (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO); RB40.34, an IgG1 mAb against murine P-selectin (20 μg/mouse; BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA); RME-1, an IgG1 mAb against rat and mouse E-selectin (100 μg/mouse); RMP-1 a mAb against rat and mouse P-selectin (100 μg/mouse); 6C7.1 a mAb against murine VCAM-1 (90 μg/mouse, hybridoma generously provided by Drs. Dietmar Vestweber and Britta Engelhardt, Max Planck Institut, Muenster, Germany); and A110-1 (IgG1) or A110-2 (IgG2) (20 to 100 μg/mouse; BD Biosciences), rat anti-keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) mAbs used as isotype control mAbs in intravital microscopy and adhesion molecule expression experiments. The doses of all function-blocking antibodies used have been shown previously to be effective in specifically blocking their respective target molecules in vivo. 3,17,18 RB6-8C5 (anti-Gr-1), FA-11 (anti-CD68), and KT3 (anti-CD3) were purified from hybridoma supernatants.

RPA Protocol

The RPA response was used as a model of IC-induced leukocyte recruitment. 19,20 Briefly, 500 μg of OVA (Sigma Chemical Co.), at 5 mg/ml in sterile saline, was injected intravenously via the tail vein. Immediately thereafter, 25 μl of polyclonal anti-OVA antibody (containing ∼100 μg IgG) (Sigma Chemical Co.) was injected intrascrotally in 200 μl of sterile saline, adjacent to the cremasteric microvasculature. Control animals were treated with intrascrotal injections of 100 μg of nonspecific rabbit IgG and intravenous OVA as for RPA mice (OVA/rabbit IgG). Responses were subsequently assessed at various stages up to 24 hours after induction of the RPA response.

Intravital Microscopy

Intravital microscopy of the murine cremaster muscle was performed as previously described. 17 Animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a cocktail of 10 mg/kg of xylazine (Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Pymble, NSW, Australia) and 200 mg/kg of ketamine hydrochloride (Caringbah, NSW, Australia). The left jugular vein was cannulated to administer additional anesthetic and antibodies. The animal was placed on a thermocontrolled-heating pad (Fine Science Tools, Vancouver, BC, Canada), regulating the core temperature to 37°C. The cremaster muscle was dissected free of tissues and exteriorized onto an optically clear viewing pedestal. The muscle was cut longitudinally with a cautery and held flat against the pedestal by attaching silk sutures to the corners of the tissue. The muscle was then superfused with bicarbonate-buffered saline, and covered with a coverslip held in place with vacuum grease (Dow Corning, ℅ Crown Scientific, Scoresby, Australia).

The cremasteric microcirculation was visualized using an intravital microscope (Axioplan 2 Imaging; Carl Zeiss Australia) with a ×20 objective lens (LD Achroplan 20X/0.40 NA, Carl Zeiss) and a ×10 eyepiece. A color video camera (Sony SSC-DC50AP, Carl Zeiss) was used to project the images onto a calibrated monitor (Sony PVM-20N5E) and the images were recorded for playback analysis using a videocassette recorder (Panasonic NV-HS950; Klapp Electronics, Prahran, Vic., Australia) as previously described. 21 One to four venules (25 to 40 μm in diameter) were selected in each experiment and to minimize variability, the same section of venule was observed throughout the experiment. Venular diameter and the number of rolling and adherent leukocytes were determined off-line during video playback analysis. Rolling leukocytes were defined as those cells moving at a velocity less than that of erythrocytes within a given vessel. Leukocyte rolling velocity was determined by measuring the time required for a leukocyte to roll along a 100-μm length of venule. Rolling velocity was determined for 20 leukocytes at each time interval. Leukocytes were considered adherent to the venular endothelium if they remained stationary for 30 seconds or longer. Leukocyte emigration was defined as the number of extravascular leukocytes visible per microscopic field centered on a postcapillary venule, and was determined by averaging data derived from four to five fields. Centerline red blood cell velocity (VRBC) was measured on-line using an optical Doppler velocimeter (Microcirculation Research Institute, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX) and mean red blood cell velocity (VMEAN) was determined as VRBC/1.6. Venular wall shear rate (γ) was calculated based on the Newtonian definition: γ = 8 (VMEAN/Dv). 22

Experimental Protocol

In the initial series of experiments, leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in the cremasteric microvasculature were examined 4, 8, and 24 hours after induction of the RPA response. These experiments revealed that peak levels of interactions were observed 4 hours after initiation of the response. Therefore to determine the roles of the endothelial selectins in mediating leukocyte rolling associated with this response, additional mice underwent the RPA protocol and were subsequently treated with function-blocking antibodies to P-selectin and E-selectin at various stages between 2.5 to 5 hours after initiation of the response. The effect of these treatments on leukocyte rolling was assessed. To reveal any P-selectin-independent leukocyte rolling throughout the first 5 hours of the response, in additional groups of mice P-selectin was inhibited continuously for the entire response, by intravenous dosing with 40 μg of RB40.34 at the same time as the OVA administration. Pilot experiments revealed that this treatment was effective in preventing rolling in cremasteric postcapillary venules in naïve mice for 4 to 5 hours. Some of these animals were also treated with RME-1 during the course of the experiment, to establish the role of E-selectin in mediating P-selectin-independent rolling in this response. An additional approach to assessing the role of P-selectin, E-selectin, and VCAM-1 in the RPA response was to examine P-selectin−/− mice under a range of conditions. P-selectin−/− mice were examined after undergoing the RPA response alone, or with RME-1, or RME-1 and 6C7.1 administered at the commencement of the response. Finally to assess the role of VCAM-1 alone, wild-type mice were treated with 6C7.1 at the commencement of the RPA response and examined 4 hours later.

In Vivo Assessment of Immune Complex Formation

To examine the location and timing of IC formation, fluorochrome-conjugated OVA (Alexa 488 OVA; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and fluorochrome-conjugated anti-OVA (Alexa Fluor 594, conjugated according to the manufacturer’s instructions; Molecular Probes) were used to initiate the RPA response. In these animals, the response in the cremaster muscle was visualized via fluorescence microscopy. The tissue distribution of Alexa 488-conjugated OVA was determined by epi-illumination at 450 to 490 nm, with a 515-nm emission filter (Carl Zeiss filter set 09). Localization of Alexa 594-conjugated anti-OVA was assessed using a 530- to 585-nm excitation filter, with a 615-nm emission filter (Carl Zeiss filter set 00). In some animals, Alexa 488-conjugated OVA alone was used, to assess the distribution of systemically injected OVA in the absence of anti-OVA.

Tissues from these experiments were then snap-frozen in OCT embedding medium and prepared for confocal microscopy as previously described. 23 Cryostat sections (6 μm) were prepared and mounted in anti-fade fluorescence-mounting media (DAKO, NSW, Australia), in the absence of fixation. Confocal images were collected using a confocal inverted Nikon Diaphot 300 microscope (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) equipped with an air-cooled 25-mW argon/krypton laser (excitation at 488 and 586 nm), as previously described. 23 Digital images were collected using Bio-Rad Laser Sharp 2000 version 4.1 software.

Quantitation of Endothelial Adhesion Molecule Expression

Expression of P- and E-selectin was quantitated using a method adapted from Piccio and colleagues. 24 RMP-1 (anti-P-selectin) was conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In addition, as a nonspecific control IgG, anti-KLH antibody (BD Biosciences) was conjugated with Alexa 594. In microscopy experiments, Alexa 488/594-conjugated mAbs were visualized as for the similarly labeled molecules described above. Images were visualized using a SIT video camera (Dage-MTI VE-1000; Sci Tech Pty. Ltd., Preston South, Vic., Australia) on predefined gain and black level settings, and recorded for subsequent playback analysis using a videocassette recorder.

Mice underwent the RPA protocol as detailed above. At the end of the experimental period, mice were anesthetized, the right carotid artery and left jugular vein were cannulated, and the cremaster muscle prepared for microscopy. Recordings of background fluorescence detectable in the cremaster preparation were made for each of the excitation wavelengths, and these data were subtracted from all subsequent intensity readings. Then, to detect P-selectin expression, mice received 100 μg of RMP-1ALEXA 488 (a dose previously determined to saturate available receptors) and 20 μg of anti-KLHALEXA 594 intravenously. This ratio of binding mAb to nonbinding mAb is similar to that used in previous experiments examining selectin expression in vivo. 25 Despite the difference in the amount of each antibody administered, binding of the specific antibody to its target antigen throughout the animal reduces its concentration in the circulation meaning that the levels of the two mAbs in the plasma are relatively similar. Moreover, irrespective of the relative amounts of circulating antibody, the final level of accumulation of each mAb is expressed relative to its own initial loading within the microvasculature. The microcirculation was visualized 1 to 2 minutes after administration of the mAbs and recorded at each excitation wavelength, to determine the initial level of each fluorochrome-conjugated mAb in the circulation. Antibodies were allowed to circulate for 5 minutes, and then the mouse was exsanguinated via the carotid artery cannula with simultaneous perfusion of bicarbonate-buffered saline via the jugular vein. An additional 10 ml of buffer was subsequently backflushed through the carotid artery after severing the abdominal vena cava. The microcirculation was then revisualized to detect selectin expression.

P-selectin expression was quantitated in two ways. Firstly the length of vessel containing specific (RMP-1ALEXA 488) labeling in the absence of nonspecific (anti-KLHALEXA 594) labeling was determined for 10 to 15 sequential ×10 (Achroplan 10X/0.25 NA) fields. Individual video frames were captured from videotape as previously described, 26 and analyzed using Scion Image analysis software (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD). These data were expressed as mm-positive vessel/mm2 tissue area. Secondly, the intensity of staining in individual vessels was determined, using a ×20 objective lens (LD Achroplan 20X/0.40 NA, Carl Zeiss). To assess this parameter, the degree of nonspecific antibody accumulation was first determined by measuring the intensity of Alexa 594-associated fluorescence remaining after exsanguination, and expressing this as a percentage of the initial loading of this fluorochrome in the vessel. The intensity of Alexa 488-derived fluorescence (RMP-1) associated with the vascular wall was then measured. These data were then reduced by the percentage binding of the control antibody, to account for the contribution of nonspecific antibody accumulation, and the data expressed as intensity units. Previous experiments using radiolabeled antibodies to quantitate adhesion molecule expression in vivo have used a comparable approach to account for nonspecific accumulation of antibodies in the vasculature. 25,27 This technique revealed constitutive expression of P-selectin, in the cremasteric microvasculature in accord with previous observations. 25,28

Because the P-selectin experiments revealed that nonspecific antibody accumulation in this assay was minimal, E-selectin expression was assessed using a specific antibody only (RME-1ALEXA 594, 100 μg). Using this approach, constitutive expression of E-selectin was detectable in some dermal microvessels but absent in the cremaster muscle, in accord with previous observations. 28-30

Immunohistochemical Identification of Infiltrating Leukocytes and C3 Deposition

Leukocytes present in cremaster muscles after RPA challenge were identified using a three-layer immunoperoxidase technique according to a previously published technique. 31 Cremaster muscles were fixed in periodate/lysine/paraformaldehyde, cryoprotected in 7% sucrose/phosphate-buffered saline, and frozen over liquid nitrogen. Eight-μm sections were prepared on a cryostat, and individual sections stained using RB6-8C5 (anti-Gr-1) to demonstrate neutrophils, FA-11 (anti-CD68) for monocytes/macrophages, and KT3 (anti-CD3) to demonstrate T lymphocytes. 31 The level of recruitment of each of these cell types was assessed semiquantitatively, using a 0 to 3 scale. Similarly fixed sections were stained for C3 deposition by direct staining with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse C3 (Cappel Laboratories/ICN Biomedicals Australasia, Seven Hills, NSW, Australia). Sections were preincubated with 10% goat serum in 5% bovine serum albumin/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (10 minutes) then stained with anti-mouse C3 diluted 1:400 in 1% bovine serum albumin/PBS (30 minutes). Slides were washed in PBS and mounted in aqueous mounting medium. 13

Statistical Analysis

All data are displayed as mean ± SEM. Initial comparisons across three to four groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests. For comparisons involving only two groups, Student’s t-tests were used. Paired analysis was used for comparison between before and after antibody treatments. A value of P < 0.05 was deemed significant.

Results

Location of Immune Complex Formation during the RPA Response

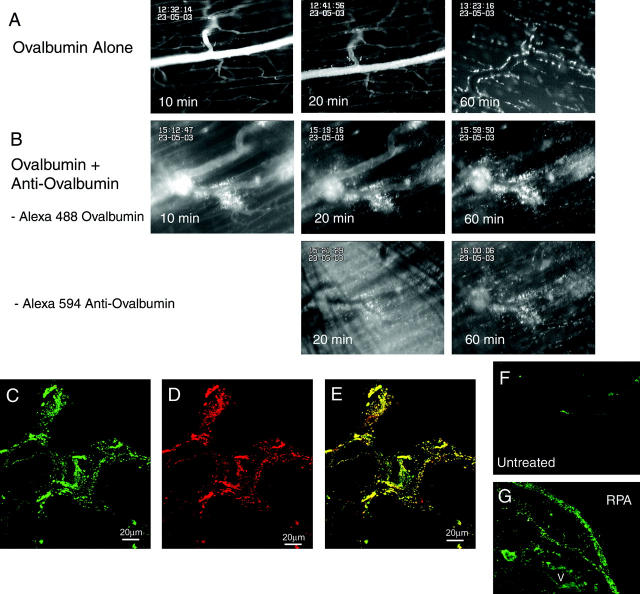

In initial experiments we examined the formation of ICs during the RPA response in the cremaster muscle using an in vivo fluorescence microscopy approach (Figure 1) ▶ . After intravenous injection of Alexa 488-conjugated OVA, OVA progressively exits the vasculature and distributes throughout the entire muscle. In the first 20 minutes, OVA is restricted to the perivascular area, in some cases in a localized pattern suggestive of cellular binding. However by 30 to 45 minutes after administration, OVA-derived fluorescence is widely distributed throughout the muscle tissue, apparently binding to cells throughout the muscle. Staining was excluded from muscle fibers (Figure 1A) ▶ . When Alexa 594-conjugated anti-OVA antibody was superfused over the tissue at the same time as intravenous OVA injection, a different response was observed (Figure 1B) ▶ . Within 10 minutes of OVA administration, large amounts of OVA were present in the perivenular tissue, suggestive of a rapid increase in vascular permeability. Indeed, whereas in the OVA-alone experiments, circulating OVA remained detectable in the vasculature for at least 40 minutes, in the presence of anti-OVA OVA was lost from the circulation much more rapidly. This is in accord with previous observations of a rapid increase in tissue edema in the initial stages of the RPA response. 8 We also examined the distribution of Alexa 594-conjugated anti-OVA during the same period. Initially the anti-OVA was evenly distributed across the tissue. However, 20 minutes after initiation of the response localized regions of intense Alexa 594-derived fluorescence were present in perivenular areas, co-localized with OVA (Figure 1B) ▶ . Examination of cryostat sections of these tissues via confocal microscopy revealed that 60 minutes after OVA administration, all OVA was co-localized with anti-OVA (Figure 1, C to E) ▶ . A similar staining pattern was observed 4 hours after OVA administration (data not shown). Examination of C3 deposition 4 hours after RPA revealed a very similar distribution of staining, with localized C3 staining present both in perivascular regions and throughout the tissue (Figure 1G) ▶ . Taken together, the co-localization of OVA and anti-OVA, as well as the spatially similar C3 deposition, suggest that ICs initially form in perivascular regions, associated with the initial exit of OVA from the vasculature. Subsequently ICs form throughout the tissue, both in perivascular regions, and at sites well away from the vasculature.

Figure 1.

Analysis of co-localization of Alexa 488-OVA and Alexa 594-anti-OVA during the RPA response in the cremasteric microvasculature. A and B: Intravital microscopy images of the cremaster muscle 10, 20, and 60 minutes after intravenous injection of Alexa 488-OVA. A: The progressive spread of OVA from within the vasculature to the extravascular compartment in the unperturbed microcirculation is illustrated. B: The rapid perivascular accumulation of OVA during the RPA response is illustrated. The top panels show OVA (excitation, 450 to 490 nm) and the bottom panels illustrate the simultaneous accumulation of anti-OVA (excitation, 530 to 585 nm), in the same region as the OVA. C–E: Illustrated are the confocal microscopy images of samples from B, 60 minutes after initiation of RPA. C: The distribution of Alexa 488-OVA, designated green; D: the distribution of Alexa 594-anti-OVA, designated red; and E: the merged images, with yellow staining indicative of co-localization. F and G: C3 deposition in cremaster muscle sections, demonstrated via direct staining with FITC-goat anti-mouse C3. F: Untreated muscle; G: muscle 4 hours after RPA. After RPA, C3 is deposited in the wall of a blood vessel (V), as well as spread throughout the tissue. Scale bars, 20 μm. (C–E). Original magnifications, ×200 (F and G).

Immune Complex-Induced Alterations in Leukocyte Trafficking

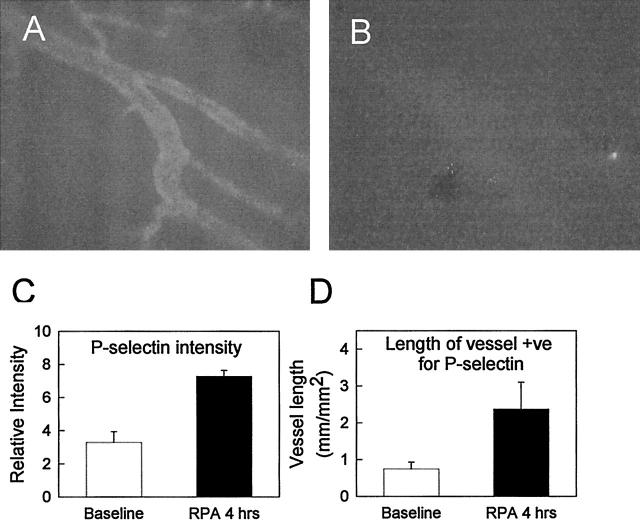

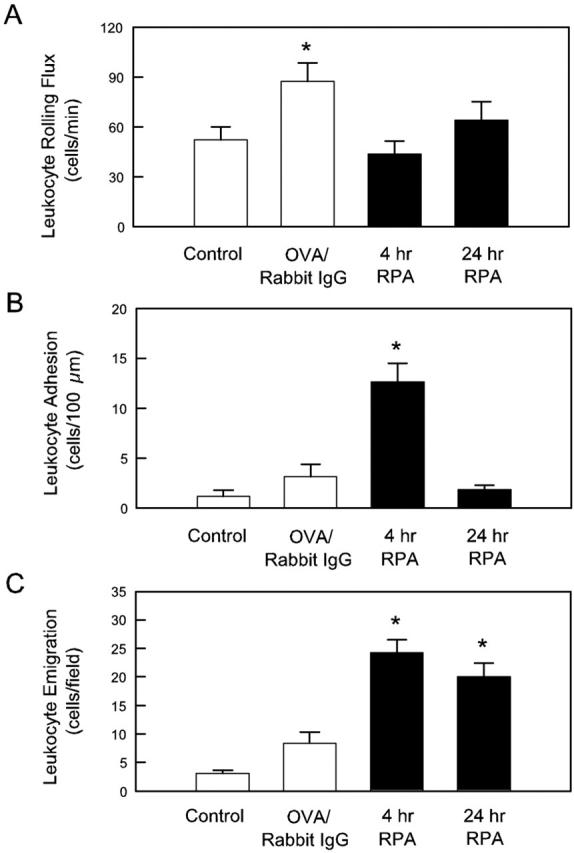

We next examined the alterations in leukocyte rolling, adhesion, and emigration in the cremasteric microvasculature induced by the RPA protocol. Table 1 ▶ shows venular diameters and microvascular shear rates in naïve, OVA/rabbit IgG, and RPA mice 4 hours after treatment. No significant differences were observed in these parameters. Four hours after initiation of the response, leukocyte rolling in OVA/rabbit IgG-treated mice was significantly elevated above levels in untreated mice (Figure 2A) ▶ . However, leukocyte rolling flux in RPA-treated mice was not different from levels in untreated mice. In contrast to rolling flux, leukocyte rolling velocity was dramatically reduced both in RPA mice, and to a lesser extent in OVA/rabbit IgG mice (Table 1) ▶ . Eight hours after RPA treatment, both leukocyte rolling flux and velocity returned to basal levels (data not shown) and remained at this level 24 hours after treatment. The most marked effects of the RPA treatment were discernable on examination of leukocyte adhesion and emigration. Four hours after RPA treatment, leukocyte adhesion and emigration were significantly elevated above levels in both untreated and OVA/rabbit IgG mice (Figure 2, B and C) ▶ . Emigration was ∼25 cells/field at 4 hours. As seen with the rolling response, the increase in leukocyte adhesion had abated by 8 hours (not shown) and remained at basal levels at 24 hours. However significant numbers of leukocytes remained present in the tissue at 24 hours (Figure 2C) ▶ . These observations indicated that this model of IC-induced inflammation was highly effective at inducing leukocyte recruitment into the cremaster muscle, as seen previously in other tissues.

Table 1.

Venular Diameter, Microvascular Shear Rates, and Leukocyte Rolling Velocities in Naïve, OVA/Rabbit IgG or RPA Mice 4 Hours after Initiation of Response

| Naïve | OVA/rabbit IgG | RPA 4 hours | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venular diameter, μm | 30.1 ± 1.4 | 32.3 ± 2.1 | 32.2 ± 0.8 |

| Shear rate, s−1 | 449 ± 34 | 513 ± 55 | 383 ± 38 |

| Leukocyte rolling velocity, μm/s | 68.6 ± 9.8 | 30.4 ± 5.4* | 10.7 ± 1.5* |

| (n) | (6) | (6) | (6) |

*P < 0.05 relative to control group.

Data are shown as mean ± sem of n observations.

Figure 2.

Leukocyte rolling (A), adhesion (B), and emigration (C) in cremasteric postcapillary venules of untreated mice, or mice after injection of OVA and nonspecific IgG (OVA/rabbit IgG), or the complete RPA protocol 4 and 24 hours after induction. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of six observations/group. *, P < 0.05 relative to control group.

Immunohistochemical analysis was used to identify the types of leukocytes recruited. Four hours after RPA, large numbers of Gr-1+ neutrophils were present, with FA-11+ cells, representing monocytes/macrophages, present in lower numbers. CD3+ leukocytes (T lymphocytes) were only rarely observed at this time point (Table 2) ▶ . At 24 hours, the numbers of Gr-1+ leukocytes remained at a high level, whereas the number of FA-11+ cells was increased relative to the earlier time point. In 50% of the animals examined, small numbers of T lymphocytes were also present at 24 hours.

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical Analysis of Recruitment of Gr-1+, FA-11+, and KT3+ Leukocytes in the Cremaster Muscle of Individual Mice 4 and 24 Hours after Initiation of the RPA Response

| Time of RPA response | Gr-1+* | FA-11+ | KT3+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 hours (n = 4) | 2.4 (1.5–3) | 1.5 (1–2) | 0.25 (0–1) |

| 24 hours (n = 4) | 2.7 (2–3) | 2.2 (1.5–3) | 0.75 (0–1.5) |

*The degree of infiltration of Gr-1+, FA-11+, and KT3+ leukocytes in sections of cremaster muscle was scored on a scale of 0 to 3. Data are shown as mean (range) for n = four animals.

RPA Induces P-Selectin Up-Regulation and Expression of E-Selectin

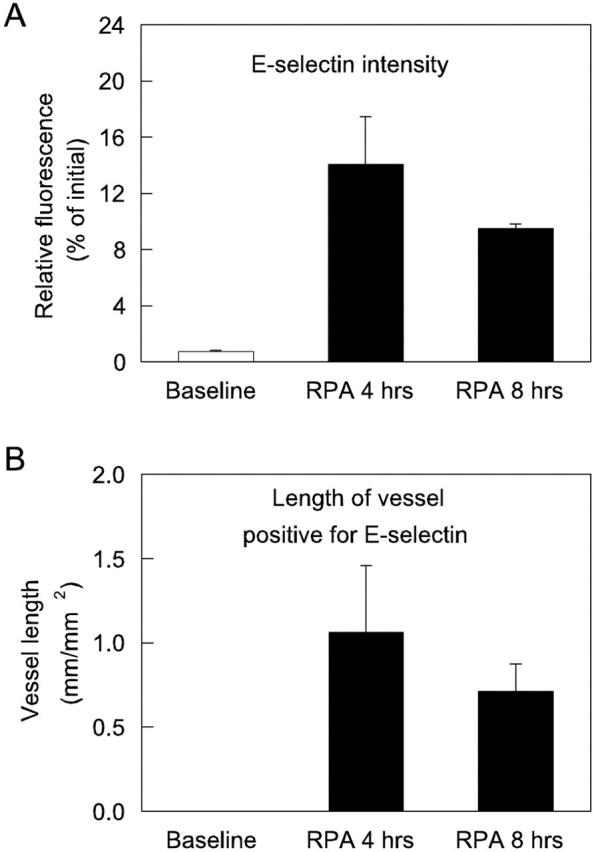

Given that previous studies have indicated a role for P- and E-selectin in IC-mediated leukocyte recruitment to other tissues, we next examined the effect of RPA treatment on expression of the endothelial selectins. P-selectin was expressed constitutively at low levels, in accord with our previous observations. 28 However, this expression was only detectable in a low proportion of venules in the untreated cremaster muscle. In contrast, 4 hours after RPA treatment, P-selectin expression markedly increased (Figure 3) ▶ . Direct analysis of the cremasteric microvasculature after labeling with RMP-1ALEXA 488 indicated that this increase in expression occurred as both an increase in the level of P-selectin expression in individual vessels (Figure 3C) ▶ , and an increase in the number of venules expressing P-selectin (Figure 3D) ▶ . A different pattern was observed for E-selectin expression. As previously documented, E-selectin was undetectable in untreated cremaster muscles. 28 However, 4 hours after initiating the RPA response, E-selectin was clearly expressed (Figure 4) ▶ , although the venular length found to be positive for E-selectin was ∼50% of that positive for P-selectin. After 8 hours, E-selectin expression had decreased, but remained detectable.

Figure 3.

P-selectin expression in the RPA-treated mouse cremaster muscle. A: Image of P-selectin expression 4 hours after RPA induction, as detected by labeling with RMP-1ALEXA 488, and fluorescence microscopy at 450 to 490 nm excitation. B: Accumulation of the nonbinding control mAb (anti-KLH ALEXA 594visualized at 530 to 585 nm excitation) was negligible. Image analysis was performed on multiple vessels per preparation in both untreated and RPA mice to determine average intensity of P-selectin expression in labeled venules (expressed as relative intensity) (C), and average length of positively stained vessel per field (expressed as mm-positive vessel/mm2 tissue area) (D). Data represent mean ± SEM of four mice per group.

Figure 4.

E-selectin expression in RPA-treated mouse cremaster muscle. Image analysis was performed on multiple vessels per preparation in both untreated and RPA mice to determine average intensity of E-selectin expression in labeled venules (expressed as a percentage of the initial loading of the fluorochrome in the vessel) (A), and average length of positively stained vessel per field (expressed as mm-positive vessel/mm2 tissue area) (B). Data represent mean ± SEM of two mice per group.

Overlapping roles for P-Selectin and E-Selectin in RPA-Induced Rolling

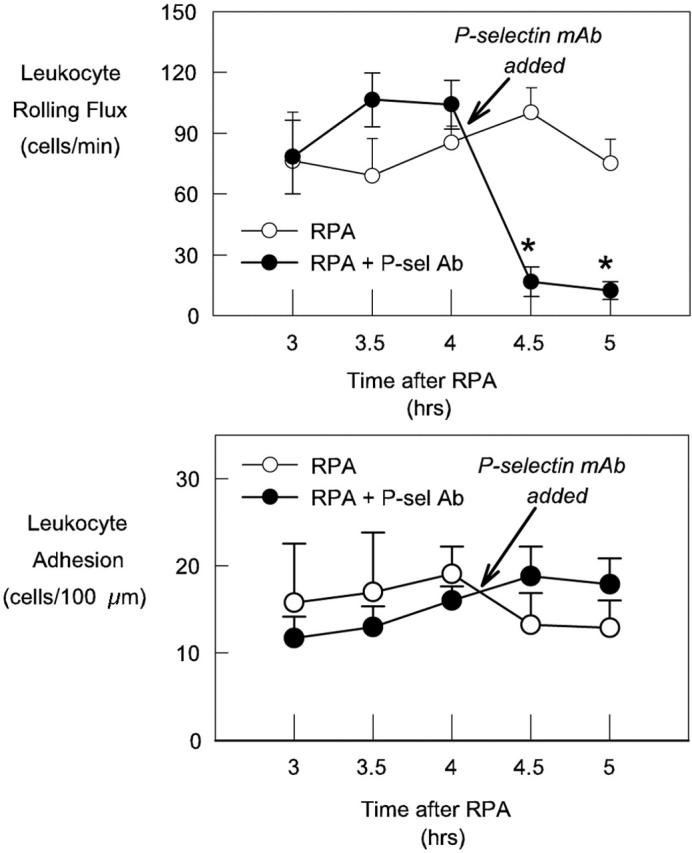

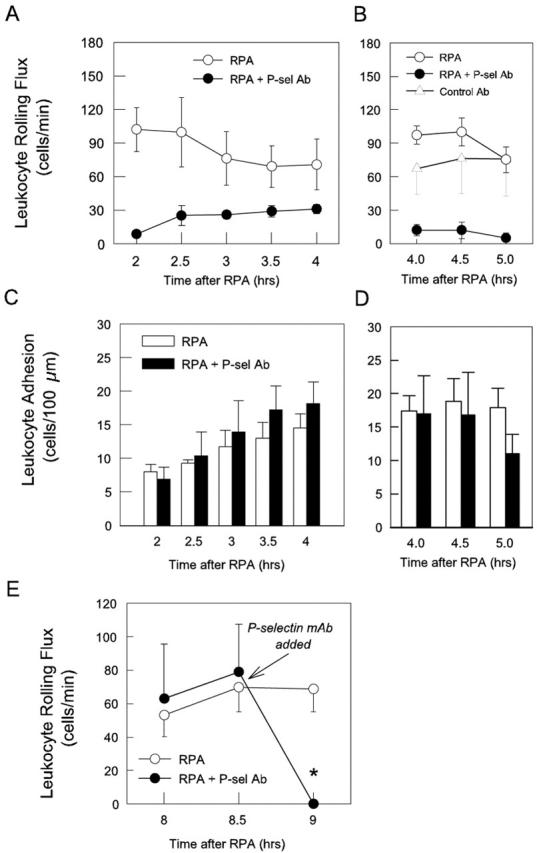

In the next series of experiments we used function-blocking mAbs to delineate the individual roles of the endothelial selectins in mediating leukocyte rolling after RPA. Administration of anti-P-selectin shortly after the 4-hour time point reduced leukocyte rolling by 80 to 90% (Figure 5A) ▶ . Administration of nonbinding control antibody at the same time point had no significant effect on leukocyte rolling flux (data not shown). The residual P-selectin-independent rolling revealed by this protocol persisted until at least 5 hours after RPA. However, P-selectin blockade had no significant effect on leukocyte adhesion throughout this time course (Figure 5B) ▶ . To clearly define the development of the P-selectin-independent leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions, we then examined the effect of P-selectin blockade throughout the entire RPA protocol. In RPA-treated animals, P-selectin antibody was administered intravenously at the same time as the OVA, at a dose shown in pilot studies to block leukocyte rolling in the cremaster muscle for at least 5 hours. Because it was not feasible to examine mice for longer than 2 hours, two groups of animals were examined: the first group covered the period between 2 to 4 hours after RPA, and the second were examined from 4 to 5 hours. These experiments revealed that significant P-selectin-independent rolling first developed ∼2 hours after RPA and increased to a peak of ∼25 to 30 cells/minute, between 2.5 to 4 hours (Figure 6A) ▶ . This rolling had declined to minimal levels 5 hours after initiation of the RPA response (Figure 6B) ▶ . In additional RPA-treated mice at 8 hours, P-selectin blockade eliminated leukocyte rolling, indicating that the P-selectin-independent rolling had ceased by this point (Figure 6E) ▶ . No reduction in rolling was observed in wild-type mice treated with control nonblocking antibody at either 2 to 4 hours (data not shown) or 4 to 5 hours (Figure 6B) ▶ . In contrast to the effect on rolling, leukocyte adhesion in mice undergoing continuous P-selectin blockade increased at the same rate as that observed in normal RPA-treated mice, indicating that the low level of P-selectin-independent rolling was sufficient to allow adhesion to reach levels achieved without P-selectin blockade (Figure 6, C and D) ▶ .

Figure 5.

Effect of acute P-selectin blockade on leukocyte rolling (top) and leukocyte adhesion (bottom) in RPA-treated mice 3 to 5 hours after initiation of response. Examination of leukocyte trafficking commenced 3 hours after the start of the response, and was subsequently examined at 30-minute intervals to 5 hours. Shown are untreated RPA mice (n = 6) and RPA mice in which P-selectin mAb was administered at 4:15 (n = 8). Data represent mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 relative to pre-mAb data.

Figure 6.

Effect of continuous P-selectin blockade throughout the first 4 hours of the RPA protocol on leukocyte rolling (A and B) and adhesion (C and D) in cremasteric postcapillary venules, and acute P-selectin blockade on leukocyte rolling 8 hours after RPA (E). Separate groups of mice were examined 2 to 4 hours (A and C), 4 to 5 hours (B and D), and 8 hours (E) after initiation of the response. Shown in A–D are untreated RPA mice (2 to 4 hours, n = 6; 4 to 5 hours, n = 10), RPA mice treated with anti-P-selectin (RB40.34, 40 μg) at the commencement of the response (2 to 4 hours, n = 8; 4 to 5 hours, n = 5), and RPA mice treated with control antibody (A110-1, 40 μg,) at the start of the response (4 to 5 hours, n = 2; D). The RB40.34-treated groups reveal the time course of P-selectin-independent rolling in this response. E: Untreated RPA mice 8 to 9 hours after RPA initiation (n = 6), and RPA mice treated with anti-P-selectin 8.5 hours after initiation of the response (RB40.34, 20 μg, n = 4), illustrating that P-selectin-independent rolling had ceased at this time point. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 versus untreated RPA mice.

E-Selectin Mediates P-Selectin-Independent Rolling in the RPA Response

Given that the time course of P-selectin-independent rolling mirrored that of E-selectin expression, we next examined the role of E-selectin in the response. Acute E-selectin blockade in wild-type RPA mice had no effect on leukocyte rolling flux or adhesion (data not shown). Moreover, pretreatment of mice with RME-1 at the start of the RPA response did not significantly alter leukocyte entry into the inflamed cremaster muscle [4 hours emigration: wild-type, 35.9 ± 7.5 cells/field (n = 10) versus continuous E-selectin blockade, 43 ± 8.4 cells/field (n = 4)]. These findings indicate that under conditions in which P-selectin-dependent rolling is unimpeded during the first 4 hours of the RPA response, continual E-selectin blockade does not reduce the ability of leukocytes to enter the inflamed site.

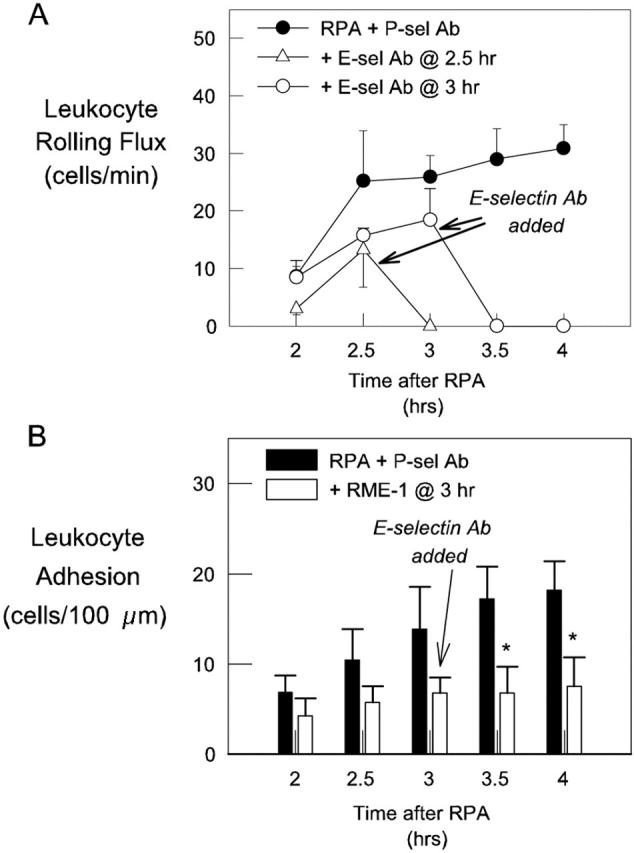

We next examined whether E-selectin mediated the P-selectin-independent rolling interactions seen in RPA-treated mice undergoing continuous P-selectin blockade. In these mice, E-selectin blockade at either 2.5 hours or 3 hours completely eliminated rolling. Furthermore, in P-selectin-inhibited mice treated with RME-1 at 3 hours, rolling continued to be completely inhibited at 4 hours (Figure 7A) ▶ . The absence of rolling in animals undergoing combined blockade of P- and E-selectin resulted in a significant reduction in leukocyte adhesion at 3.5 and 4 hours relative to animals in which P-selectin alone was inhibited (Figure 7B) ▶ . These findings demonstrate that the endothelial selectins combined to mediate all of the leukocyte rolling during this phase of the RPA response.

Figure 7.

Effect of E-selectin blockade on P-selectin-independent leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in RPA-treated mice. Mice received a blocking dose of anti-P-selectin mAb at the start of the RPA response and then subsequently were untreated (filled circles, n = 8), or received E-selectin mAb at either 2.5 hours (open triangles, n = 3) or 3 hours (open circles, n = 4). A: Leukocyte rolling 2 to 4 hours after initiation of the RPA response. B: Leukocyte adhesion throughout the same period in RPA mice treated with either P-selectin mAb alone (filled bars, n = 8) or P-selectin mAb plus E-selectin mAb at 3 hours (open bars, n = 4). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 versus continuous P-selectin blockade alone.

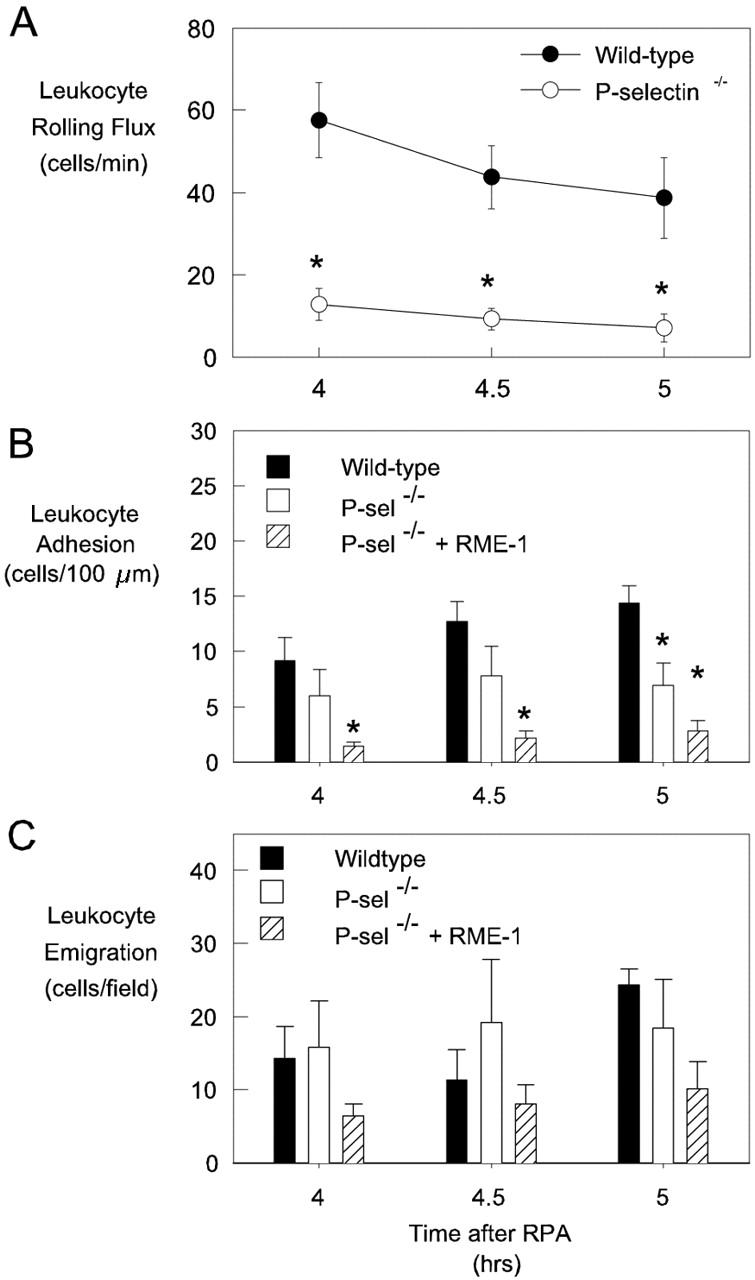

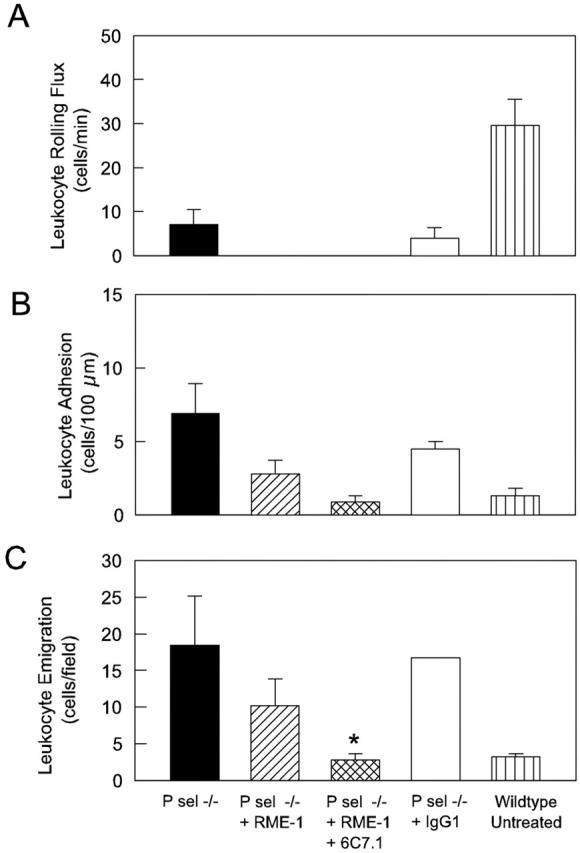

To confirm these observations we performed similar experiments in P-selectin−/− mice. These experiments revealed similar data in that a low level of P-selectin-independent rolling was apparent between 4 to 5 hours after RPA (Figure 8A) ▶ . Leukocyte adhesion, although not different from that in wild-type mice at 4 and 4.5 hours, was significantly reduced at 5 hours relative to levels in wild-type mice (Figure 8B) ▶ . Despite this reduction in adhesion, leukocyte emigration in P-selectin−/− mice reached a comparable level to that in wild-type mice (Figure 8C) ▶ . These observations confirm that P-selectin-mediated rolling was not required for leukocyte accumulation in the extravascular tissue to reach normal levels during the first 5 hours of the RPA response. To examine the combined role of P- and E-selectin throughout the entire course of the response, we treated P-selectin−/− mice with anti-E-selectin mAb at the initiation of RPA. These animals showed no detectable rolling between 4 to 5 hours. In addition this treatment resulted in a significant reduction in leukocyte adhesion at 4 and 4.5 hours, in contrast to the untreated P-selectin−/− animal. However even with this combined treatment, leukocyte emigration was not different from that in RPA-treated wild-type mice.

Figure 8.

RPA response in P-selectin−/− mice. Leukocyte rolling (A), adhesion (B), and emigration (C) in cremasteric postcapillary venules were examined in wild-type mice (filled bars), P-selectin−/− mice (open bars), and P-selectin−/− mice treated with RME-1 at the start of the response (hatched bars), between 4 to 5 hours after initiation of the RPA response. Data represent mean ± SEM of six observations per group. *, P < 0.05 relative to wild-type mice at the same time point.

VCAM-1 Is Required for Adhesion and Emigration in RPA-Treated Mice

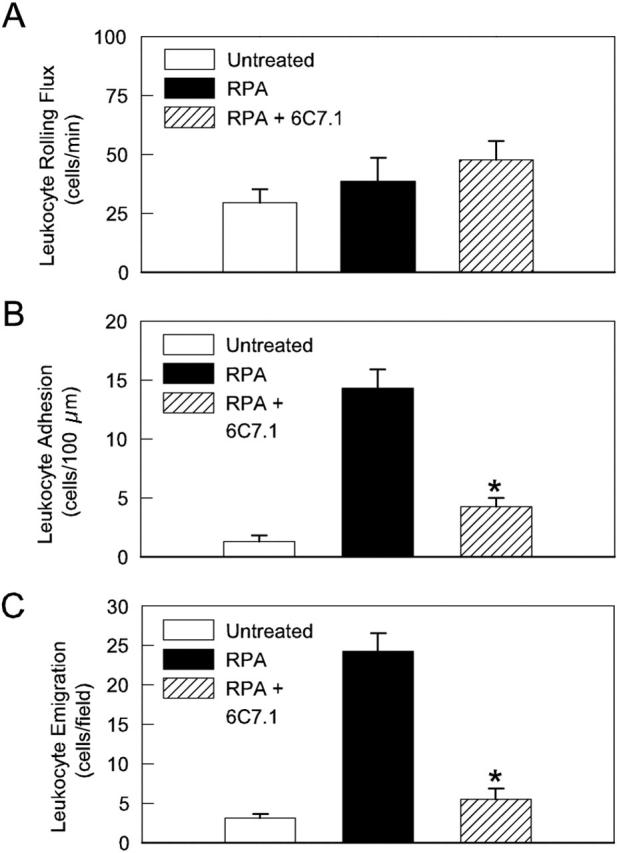

Given that adhesion and emigration continued to occur in RPA mice in which P-selectin was absent and E-selectin was inhibited, we investigated the role of VCAM-1 in mediating the ongoing adhesive interactions. Combined blockade of E-selectin and VCAM-1 in P-selectin−/− mice reduced adhesion to basal levels, and significantly reduced leukocyte emigration at 5 hours (Figure 9) ▶ . These findings suggested a key role for VCAM-1 in the RPA response. Therefore in a final series of experiments we examined the effect of inhibiting VCAM-1 alone in wild-type RPA mice (Figure 10) ▶ . VCAM-1 blockade throughout the entire response did not affect leukocyte rolling flux at 5 hours, although it did result in a significant increase in leukocyte rolling velocity at 4.5 hours (data not shown), indicating a possible role for VCAM-1 in supporting rolling. However, the most marked effects of this treatment were on leukocyte adhesion and emigration, both of which were significantly decreased after VCAM-1 blockade. Indeed, these parameters were reduced to such an extent that they were not different from levels in untreated mice. Control antibody treatment throughout the same time course had no discernable effect (shown in Figure 6B ▶ ). These data clearly illustrate that VCAM-1 plays a key role in mediating both adhesion and emigration in the RPA response.

Figure 9.

Comparison of RPA-induced leukocyte rolling (A), adhesion (B), and emigration (C) at 5 hours in P-selectin−/− mice in the absence of antibody treatment (n = 6), or after treatment with anti-E-selectin (RME-1, 100 μg, n = 6), anti-E-selectin + anti-VCAM-1 (6C7.1, 100 μg, n = 4), or control IgG1 (100 μg, n = 2). Data from untreated wild-type mice (n = 6) are shown as comparison. *, P < 0.05 versus emigration in wild-type RPA mice.

Figure 10.

Effect of continuous VCAM-1 blockade on RPA-induced leukocyte rolling (A), adhesion (B), and emigration (C) in wild-type mice 5 hours after initiation of the response. Data from untreated wild-type mice are shown as comparison. VCAM-1 blockade reduced adhesion and emigration to levels not different from those in untreated animals (n = 6 in all groups). *, P < 0.05 versus wild-type RPA mice.

Discussion

IC-induced leukocyte recruitment is implicated as having a key role in diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and glomerulonephritis. However, the existing data regarding the molecular mechanisms responsible for the leukocyte recruitment induced by these potent proinflammatory mediators is conflicting, particularly in the identification of the molecules responsible for initiation of the leukocyte recruitment cascade. Studies in various tissues have implicated each of the three selectins as being important in this process. To clarify this issue, we elected to directly visualize the microvasculature during the course of an IC-dependent response, thereby allowing the roles of individual adhesion molecules to be clearly identified. These experiments show that in postcapillary venules of the mouse cremaster muscle, the leukocyte rolling induced during the RPA response is mediated by a combination of P- and E-selectin. P-selectin was expressed constitutively, and increased during the RPA response, mediating leukocyte rolling at all time points examined. In contrast, E-selectin was not expressed in the absence of inflammatory stimulation but was up-regulated to functional levels 2.5 hours after initiation of the response, subsequently declining to be nonfunctional at 8 hours. The observation that the leukocyte adhesion that occurs throughout this period was only inhibited when both of these molecules were blocked indicated that each of these molecules alone is capable of mediating sufficient leukocyte rolling to allow the adhesion response to reach its normal level. However, even under conditions when both P- and E-selectin were either absent or inhibited, leukocyte adhesion remained elevated above basal levels, and entry of leukocytes into the tissue (emigration) continued unabated. In these animals, blockade of VCAM-1 prevented the IC-induced increase in adhesion and emigration. These findings indicate that even though the endothelial selectins were of key importance in mediating leukocyte rolling, VCAM-1 played an overriding role in mediating entry of leukocytes into the inflamed tissue.

Previous data have used indirect techniques to implicate various combinations of the three selectin molecules in IC-induced leukocyte recruitment. In skin, either blockade of P-selectin alone or E-selectin alone has been shown to significantly reduce leukocyte entry. 10,13 In contrast in the lung, inhibition of either E-selectin or L-selectin but not P-selectin has been shown to reduce leukocyte recruitment induced by IC formation. 10-12,32 Finally, inhibition of P-selectin but not E-selectin has been shown to reduce IC-dependent leukocyte recruitment in models of glomerulonephritis believed to involve formation of ICs at the glomerular basement membrane. 9,15 Much of this disparity may be explained by differing adhesion molecule requirements in different tissues. Recent studies have clearly demonstrated that identical inflammatory responses can use different combinations of adhesion molecules in different tissues. 28,33,34 However the observations that in the skin, inhibition of either E-selectin or P-selectin alone dramatically reduces leukocyte recruitment raises the possibility that these two molecules are playing critical, yet nonoverlapping functions. Given that the types of leukocytes recruited by each of these molecules are similar, 35 the mechanism for these apparently nonoverlapping functions is not clear. Under these circumstances, the ideal way of unequivocally identifying the role of each molecule is to directly visualize the inflamed microvasculature, as performed in the present experiments. Our findings indicate that in the cremasteric microvasculature during the period of E-selectin expression, the two endothelial selectins have overlapping rather than independent roles; ie, inhibition of only one molecule is insufficient to reduce rolling to the extent that the number of adherent cells is significantly affected.

ICs have also been shown to be capable of inducing endothelial VCAM-1 expression both in vitro and in dermal microvessels in vivo. 36,37 However the present data further these observations by demonstrating a key functional role for VCAM-1 in leukocyte adhesion in the RPA response. Indeed, even in conditions in which selectin-mediated rolling was intact, VCAM-1 blockade reduced adhesion to levels not different from those in untreated animals, clearly indicating that VCAM-1 is of key importance in mediating adhesion to the endothelial lining in the RPA response. This decrease in adhesion was associated with a significant reduction in leukocyte emigration. This may be as a result of the reduction in adhesion, or alternatively it may indicate that the role of VCAM-1 extends to a direct involvement in mediating leukocyte exit from the vasculature. Given that neutrophils, which express only low levels of the VCAM-1 ligand the α4β1 integrin, are the dominant leukocyte population that enter the tissue, the prominent role for VCAM-1 may be difficult to explain. However there is a growing body of evidence that neutrophils can use α4β1 and VCAM-1 to adhere to the endothelial lining and emigrate into tissues. 38 Unstimulated murine neutrophils express functional α4 integrins and can adhere and transmigrate across activated cardiac endothelial cells using the α4β1/VCAM-1 pathway. 39,40 LPS-induced neutrophil infiltration to the liver is reduced by VCAM-1 blockade. 41 Indeed, comparable observations have also been made in a model of IC-induced neutrophil recruitment into the lung. 42 The current observations add weight to these observations suggesting that the ability of VCAM-1 to recruit neutrophils extends to IC-induced responses in striated muscle.

In this study we used a novel technique for quantitation of selectin expression in the inflamed microvasculature, based on the use of fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs, an approach previously used for qualitative assessment of adhesion molecule expression. 24,43 To render this technique more quantitative we co-perfused two antibodies labeled with nonoverlapping fluorochromes: one specific for the adhesion molecule of interest (with Alexa 488) and a control IgG (with Alexa 594). The control antibody was used as an index of nonspecific antibody accumulation remaining after the extensive exsanguination procedure. Using this approach we found that nonspecific antibody accumulation was minimal, occurring in the range of 1 to 5% of the initial vessel loading. The approach of using a nonbinding antibody to account for nonspecific accumulation has been successfully used previously in quantitative assays of adhesion molecule expression in whole tissues. 25,27 The results of the present experiments supported the predominant venular restriction of endothelial selectin expression previously observed in response to treatment with tumor necrosis factor-α. 44 Moreover these studies also demonstrated that in the case of P-selectin, not only did the level of P-selectin expression in individual vessels increase in response to the inflammatory stimulus, but the number of venules displaying detectable P-selectin also increased. It was also noteworthy that the number of vessels in which E-selectin was detectable at the peak of its expression was less than 50% that of P-selectin. These observations illustrate additional differences in the regulation of expression of the endothelial selectins during inflammatory responses.

These experiments also allowed us to examine the distribution and co-localization of OVA and anti-OVA during the development of the RPA response. Using fluorochrome-conjugated OVA we observed that, in the absence of an inflammatory response, OVA exits the vasculature and progressively distributes throughout the tissue. Given that the RPA response is initiated within minutes, this raises the possibility that ICs initially form in perivascular sites, immediately on OVA exiting the vasculature. This concept was supported by our observation of perivascular co-localization of the two proteins in the early stages of the RPA response. However, after 60 minutes, this co-localization was widespread, indicating that ICs subsequently form throughout the extravascular tissue. Furthermore, the exit of OVA from the vasculature appears to be accelerated during the RPA response as a consequence of an increase in leakage of plasma proteins from the microvasculature. This is clearly illustrated by the rapid preferential accumulation of OVA in perivenular sites early in the response, an event not observed in the absence of anti-OVA.

The identification of the site of IC formation in the RPA model raises the question of what is the most appropriate model of IC-induced inflammation. In systemic lupus erythematosus, the archetypal IC-mediated disease, autoantibodies circulate both bound to target antigen (ie, as IC), and as free antibody. However the most damaging effects mediated by ICs are believed to occur when they deposit in vascular beds such as renal glomeruli. Furthermore, some autoantibodies only form IC when they bind to an antigen in a fixed tissue location, eg, the glomerular basement membrane, thus localizing IC formation to a specific vasculature. An alternative to the RPA model for examination of the in vivo effects of ICs is the administration of preformed complexes into the circulation. Using this technique may mimic the circulation of ICs in systemic lupus erythematosus. However, variation in factors such as the size and charge of the IC may make it difficult to control the level of deposition in a specific vasculature. 45 In contrast, the RPA model is unlikely to result in significant levels of IC formation in the circulation. However, it does offer the advantage of control over the site of IC formation/deposition, enabling analysis of the effects on the microvasculature.

In recent work, Coxon and colleagues 16 demonstrated that immobilized ICs had the capacity of initiating attachment and rapid arrest of neutrophils under physiological flow conditions, in the absence of selectin-mediated tethering. This novel observation raised the possibility that IC-induced leukocyte recruitment would continue to occur even if all adhesion molecules were inhibited or absent. Our direct analysis of the RPA response indicated that VCAM-1 was the dominant molecule in mediating leukocyte adhesion in this response, suggesting that ICs present within the vasculature were not major contributors to leukocyte adhesion in this model. This finding would fit with our observation that OVA/anti-OVA co-localization appeared to occur in perivascular sites, but was not detected within the vasculature. These observations suggest that the putative mechanism of IC-mediated leukocyte capture did not play a significant role in this model of leukocyte recruitment. The absence of this mechanism in the present study may reflect differences between in vitro and in vivo approaches, particularly in the site of IC deposition. However, it is conceivable that in vascular beds such as the glomerulus, in which ICs may be present on the luminal aspect of the vasculature, IC-mediated capture may assume a greater role.

In conclusion, these studies have used direct analysis of the cremasteric microcirculation to demonstrate a dominant role for P-selectin and a transient role for E-selectin in mediating IC-induced leukocyte rolling, as well as a key role for VCAM-1 in mediating adhesion and leukocyte entry into tissue. Future experiments will aim to determine the cytokines responsible for expression of these key adhesion molecules.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Dietmar Vestweber and Dr. Britta Engelhardt, Max Planck Institut, Muenster, Germany, for their generous assistance in provision of the 6C7.1 hybridoma.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Michael J. Hickey, Ph.D., Centre for Inflammatory Diseases, Monash University Department of Medicine, Monash Medical Centre, 246 Clayton Rd., Clayton, Vic., 3168, Australia. E-mail: michael.hickey@med.monash.edu.au.

Supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia (project grant no. 236910).

MJH is a National Health and Medical Research Council RD Wright Fellow.

MUN and NCVDV contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Mayadas TN, Johnson RC, Rayburn H, Hynes RO, Wagner DD: Leukocyte rolling and extravasation are severely compromised in P-selectin-deficient mice. Cell 1993, 74:541-554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frenette PS, Mayadas TN, Rayburn H, Hynes RO, Wagner DD: Susceptibility to infection and altered hematopoiesis in mice deficient in both P- and E-selectins. Cell 1996, 84:563-574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanwar S, Bullard DC, Hickey MJ, Smith CW, Beaudet AL, Wolitzky BA, Kubes P: The association between α4-integrin, P-selectin, and E-selectin in an allergic model of inflammation. J Exp Med 1997, 185:1077-1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston B, Issekutz TB, Kubes P: The α4-integrin supports leukocyte rolling and adhesion in chronically inflamed postcapillary venules in vivo. J Exp Med 1996, 183:1995-2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hickey MJ, Granger DN, Kubes P: Molecular mechanisms underlying IL-4-induced leukocyte recruitment in vivo: a critical role for the α4-integrin. J Immunol 1999, 163:3441-3448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Springer TA: Traffic signals on endothelium for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration. Annu Rev Physiol 1995, 57:827-872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulligan MS, Wilson GP, Todd RF, Smith CW, Anderson DC, Varani J, Issekutz TB, Myasaka M, Tamatani T, Rusche JR, Vaporciyan AA, Ward PA: Role of β1, β2 integrins and ICAM-1 in lung injury after deposition of IgG and IgA immune complexes. J Immunol 1993, 150:2407-2417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teixeira MM, Fairbairn SM, Norman KE, Williams TJ, Rossi AG, Hellewell PG: Studies on the mechanisms involved in the inflammatory response in a reversed passive Arthus reaction in guinea-pig skin: contribution of neutrophils and endogenous mediators. Br J Pharmacol 1994, 113:1363-1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulligan MS, Johnson KJ, Todd RF, Issekutz TB, Miyasaka M, Tamatani T, Smith CW, Anderson DC, Ward PA: Requirements for leukocyte adhesion molecules in nephrotoxic nephritis. J Clin Invest 1993, 91:577-587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulligan MS, Varani J, Dame MK, Lane CL, Smith CW, Anderson DC, Ward PA: Role of endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule 1 (ELAM-1) in neutrophil-mediated lung injury in rats. J Clin Invest 1991, 88:1396-1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulligan MS, Watson SR, Fennie C, Ward PA: Protective effects of selectin chimeras in neutrophil-mediated lung injury. J Immunol 1993, 151:6410-6417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulligan MS, Miyasaka M, Tamatani T, Jones ML, Ward PA: Requirements for L-selectin in neutrophil-mediated lung injury in rats. J Immunol 1994, 152:832-840 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santos LL, Huang XR, Berndt MC, Holdsworth SR: P-selectin requirement for neutrophil accumulation and injury in the direct passive Arthus reaction. Clin Exp Immunol 1998, 112:281-286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaburagi Y, Hasegawa M, Nagaoka T, Shimada Y, Hamaguchi Y, Komura K, Saito E, Yanaba K, Takehara K, Kadono T, Steeber DA, Tedder TF, Sato S: The cutaneous reverse Arthus reaction requires intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and L-selectin expression. J Immunol 2002, 168:2970-2978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tipping PG, Huang XR, Berndt MC, Holdsworth SR: A role for P-selectin in complement-independent neutrophil-mediated glomerular injury. Kidney Int 1994, 46:79-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coxon A, Cullere X, Knight S, Sethi S, Wakelin MW, Stavrakis G, Luscinskas FW, Mayadas TN: Fc gamma RIII mediates neutrophil recruitment to immune complexes. a mechanism for neutrophil accumulation in immune-mediated inflammation. Immunity 2001, 14:693-704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickey MJ, Issekutz AC, Reinhardt PH, Fedorak RN, Kubes P: Endogenous interleukin-10 regulates hemodynamic parameters, leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions and microvascular permeability during endotoxemia. Circ Res 1998, 83:1124-1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vajkoczy P, Laschinger M, Engelhardt B: Alpha4-integrin-VCAM-1 binding mediates G protein-independent capture of encephalitogenic T cell blasts to CNS white matter microvessels. J Clin Invest 2001, 108:557-565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szalai AJ, Digerness SB, Agrawal A, Kearney JF, Bucy RP, Niwas S, Kilpatrick JM, Babu YS, Volanakis JE: The Arthus reaction in rodents: species-specific requirement of complement. J Immunol 2000, 164:463-468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hazenbos WLW, Gessner JE, Hofhuis FMA, Kuipers H, Meyer D, Heijnen IAFM, Schmidt RE, Sandor M, Capel PJA, Daeron M, van de Winkel JGJ, Verbeek JS: Impaired IgG-dependent anaphylaxis and Arthus reaction in FcγRIII (CD16) deficient mice. Immunity 1996, 5:181-188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hickey MJ, Sharkey KA, Sihota EG, Reinhardt PH, MacMicking JD, Nathan C, Kubes P: Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)-deficient mice have enhanced leukocyte-endothelium interactions in endotoxemia. FASEB J 1997, 11:955-964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.House SD, Lipowsky HH: Leukocyte-endothelium adhesion: microhemodynamics in mesentery of the cat. Microvasc Res 1987, 34:363-379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timoshanko JR, Kitching AR, Holdsworth SR, Tipping PG: Interleukin-12 from intrinsic cells is an effector of renal injury in crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001, 12:464-471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piccio L, Rossi B, Scarpini E, Laudanna C, Giagulli C, Issekutz A, Vestweber D, Butcher EC, Constantin G: Molecular mechanisms involved in lymphocyte recruitment in inflamed brain microvessels: critical roles for P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 and heterotrimeric Gi-linked receptors. J Immunol 2002, 168:1940-1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eppihimer MJ, Wolitzky B, Anderson DC, Labow MA, Granger DN: Heterogeneity of expression of E- and P-selectins in vivo. Circ Res 1996, 79:560-569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hickey MJ, Bullard DC, Issekutz A, James WG: Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions are enhanced in dermal postcapillary venules of MRL/faslpr (lupus-prone) mice: roles of P- and E-selectin. J Immunol 2002, 168:4728-4736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henninger DD, Panes J, Eppihimer MJ, Russell J, Gerritsen ME, Anderson DC, Granger DN: Cytokine-induced VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression in different organs of the mouse. J Immunol 1997, 158:1825-1832 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hickey MJ, Kanwar S, McCafferty D-M, Granger DN, Eppihimer MJ, Kubes P: Varying roles of E-selectin and P-selectin in different microvascular beds in response to antigen. J Immunol 1999, 162:1137-1143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weninger W, Ulfman LH, Cheng G, Souchkova N, Quackenbush EJ, Lowe JB, von Andrian UH: Specialized contributions by alpha(1,3)-fucosyltransferase-IV and FucT-VII during leukocyte rolling in dermal microvessels. Immunity 2000, 12:665-676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keelan ET, Licence ST, Peters AM, Binns RM, Haskard DO: Characterization of E-selectin expression in vivo with use of a radiolabeled monoclonal antibody. Am J Physiol 1994, 266:H278-H290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang XR, Holdsworth SR, Tipping PG: Evidence for delayed-type hypersensitivity mechanisms in glomerular crescent formation. Kidney Int 1994, 46:69-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulligan MS, Vaporciyan AA, Warner RL, Jones ML, Foreman KE, Miyasaka M, Todd RF, III, Ward PA: Compartmentalized roles for leukocytic adhesion molecules in lung inflammatory injury. J Immunol 1995, 154:1350-1363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong J, Johnston B, Lee SS, Bullard DC, Smith CW, Beaudet AL, Kubes P: A minimal role for selectins in the recruitment of leukocytes into the inflamed liver microvasculature. J Clin Invest 1997, 99:2782-2790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doerschuk CM, Winn RK, Coxson HO, Harlan JM: CD18-dependent and -independent mechanisms of neutrophil emigration in the pulmonary and systemic microcirculation of rabbits. J Immunol 1990, 144:2327-2333 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reinhardt PH, Kubes P: Differential leukocyte recruitment from whole blood via endothelial adhesion molecules under shear conditions. Blood 1998, 92:4691-4699 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lozada C, Levin RI, Huie M, Hirschhorn R, Naime D, Whitlow M, Recht PA, Golden B, Cronstein BN: Identification of C1q as the heat-labile serum cofactor required for immune complexes to stimulate endothelial expression of the adhesion molecules E-selectin and intercellular and vascular cell adhesion molecules 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:8378-8382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sunderkotter C, Seeliger S, Schonlau F, Roth J, Hallmann R, Luger TA, Sorg C, Kolde G: Different pathways leading to cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis in mice. Exp Dermatol 2001, 10:391-404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnston B, Kubes P: The alpha4-integrin: an alternative pathway for neutrophil recruitment? Immunol Today 1999, 20:545-550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pereira S, Zhou M, Mocsai A, Lowell C: Resting murine neutrophils express functional alpha 4 integrins that signal through Src family kinases. J Immunol 2001, 166:4115-4123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowden RA, Ding ZM, Donnachie EM, Petersen TK, Michael LH, Ballantyne CM, Burns AR: Role of alpha4 integrin and VCAM-1 in CD18-independent neutrophil migration across mouse cardiac endothelium. Circ Res 2002, 90:562-569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Essani NA, Bajt ML, Farhood A, Vonderfecht SL, Jaeschke H: Transcriptional activation of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 gene in vivo and its role in the pathophysiology of neutrophil-induced liver injury in murine endotoxin shock. J Immunol 1997, 158:5941-5948 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mulligan MS, Wilson GP, Todd RF, Smith CW, Anderson DC, Varani J, Issekutz TB, Miyasaka M, Tamatani T, Rusche JR: Role of beta 1, beta 2 integrins and ICAM-1 in lung injury after deposition of IgG and IgA immune complexes. J Immunol 1993, 150:2407-2417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mazo IB, Gutierrez-Ramos J-C, Frenette PS, Hynes RO, Wagner DD, Von Andrian UH: Hematopoietic progenitor cell rolling in bone marrow microvessels: parallel contributions by endothelial selectins and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. J Exp Med 1998, 188:465-474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jung U, Ley K: Regulation of E-selectin, P-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in mouse cremaster muscle vasculature. Microcirculation 1997, 4:311-319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joselow SA, Mannik M: Localization of preformed, circulating immune complexes in murine skin. J Invest Dermatol 1984, 82:335-340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]