Abstract

Through studies in mammalian model systems, the orphan nuclear receptor Estrogen- Receptor Related (ERR) α has been shown to interfere with estrogen signaling and may therefore be an interesting pharmaceutical target in estrogen-related pathologies. ERRα is also involved in energy storage and consumption and its modulation may be of relevance in the treatment of obesity and diabetes. Recent data have also been published studying the effects of this receptor, as well as other members of the ERR family, in non-mammalian animal model systems. Besides indications concerning their mechanisms of action, this analysis demonstrated a role for ERRα in controlling cellular movements and suggested that ERR receptors may be implicated in a more subtle range of processes than originally envisioned.

Keywords: Animals; Brain; metabolism; Cell Differentiation; Cell Division; Drosophila melanogaster; Energy Metabolism; Gene Expression; Models, Animal; Muscles; metabolism; Receptors, Estrogen; antagonists & inhibitors; genetics; physiology

Keywords: orphan nuclear receptor, Estrogen-Related Receptor, non-mammalian models, comparative endocrinology

Introduction

Recent data have attracted attention to the ERRα orphan nuclear receptor in at least two scientific domains. First, ERRα has been shown to interact with estrogen signaling [1], a key factor in the promotion of breast cancer, itself the major cause of death by cancer among females. This has led various laboratories to analyze the expression of ERRα in human tumors (including those of mammary origin) in correlation to diverse anatomo-pathological criteria [2–5]. The long-term goal is to determine the roles played by ERRα in various aspects of cancer and, depending on these roles, to propose the receptor as a target for the design of new anticancer therapies. Second, ERRα has recently been implicated in the regulation of energy metabolism. Indeed, ERRα-defective mice are resistant to diet-induced obesity [6] and the receptor seems to participate in the regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis [7] and lipid storage and consumption [8–9]. As obesity and its associated disorders (including diabetes and cardiovascular diseases) have reached epidemic proportions in Western societies, one easily understands why any gene whose product may be involved at any level in the metabolic syndrome attracts attention as a potential target for pharmaceutical design.

The recent focus of studies into two main areas of ERRα biology (i.e. estrogen signaling/cancer and metabolism), however, does not diminish interest in investigating new aspects of regulatory function for ERRs. It is important to determine these roles for at least three reasons. First, modulating the expression/activity of ERRα as a therapy demands that we are able to predict the consequences of these modulations on other, non-intentional target tissues in order to avoid undesirable side-effects. Second, uncovering other functions of the receptor could lead to its implication in other diseases. Last, basic knowledge of the roles of a gene product per se cannot be neglected.

In addition, ERRα has two closely related paralogs in mammals (ERRβ and ERRγ), the roles of which are still poorly understood. When studying gene functions, non-mammalian models can offer a variety of advantages. These include genetic simplicity in invertebrates or experimental accessibility in fish early development. Given the frequent conservation of functions along evolution, the results gathered using these animals could lead us to envision new aspects of ERR activities in mammals. The purpose of this review is to summarize the data obtained with such nonmammalian model systems.

The ERR subfamily: an evolutionary view

The family of nuclear receptors (NRs) comprises 48 transcription factors in human (21 in Drosophila melanogaster; [10–11]) which all share a similar organization in terms of protein domains. Among NRs one finds proteins whose activity is regulated by the presence of a hydrophobic ligand and others, referred to as "orphan" receptors, for which no natural ligand has yet been described [12]. Based on phylogenetical analysis, six NR subfamilies have been described each of which have been proposed to have diversified by duplications of an orphan receptor [13–14]. Subfamily 3 is composed of three subgroups: NR3A (Estrogen Receptors [ERs]), NR3B (Estrogen-Receptor-Related receptors [ERRs]) and NR3C (Steroid Receptor [SRs]: Androgen- [AR], Glucocorticoid- [GR], Progesterone- [PR] and Mineralocorticoid- [MR] receptors).

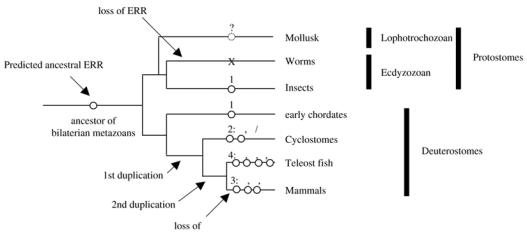

The phylogenetic relationship of ERRs to the two other subgroups is unclear. ERRs have been originally described as most closely related to the ERs (hence their name [14–15]). However this view has been challenged by recent analysis suggesting that ERRs are equally related to ERs and SRs [16], although this result is controversial [17]. Although the order of ER-ERR-SR divergence is still unresolved, it is clear that the ancestor of all bilaterian metazoans possessed one member of each subgroup (i.e. one ER, one ERR and one SR). Given the uncertainty about the phylogeny and the paucity of data concerning very early metazoa (e.g. Cnidarians and sponges), it is, to date, impossible to ascertain which gene was at the origin of the whole NR3 group. Gene loss has played an important role during the subsequent evolution of the subfamily. Indeed, if an ER gene has been found in the mollusk Aplysia californica [16], it is not present in D. melanogaster nor in Caenorhabditis elegans [10, 18], suggesting a loss in all ecdysozoans (comprising nematodes and arthropods). An ERR gene has been found in D. melanogaster and in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae but not in C. elegans [10, 17–18], suggesting a loss in the nematode genome which has been highly dynamic for nuclear receptors [19]. No ERR has yet been described in lophotrochozoa (e.g. Mollusks) although its presence is clearly implied by phylogenetical analysis (Figure 1).

Evolution of the ERR subfamily.

Ancestral ERR is predicted from phylogeny to have existed in the ancestor of bilaterian metazoans and may still be present in modern lophotrochozoans (such as mollusks). ERR (as well as other NR3 receptors) has been lost in worm phylum but maintained in insects. Position of global gene duplication events is indicated. Number and subtype of resulting ERR receptors (see text for details) are indicated. Insects include D. melanogaster (fruit fly) and Anopheles gambiae (malaria mosquito); cyclostomes include lampreys (where a β/γ fragment has been identified in Petromyzon marinus) and myxines; early chordates include Brachiostoma floridae (amphioxus), Ciona intestinalis and Herdmania curvata (two ascidians); teleost fish include D. rerio (zebrafish), Takifugu rubripes (fugu) and Tetraodon nigroviridis (tetraodon). Specific fish duplications are not represented.

From a single ancestral ERR, as still found in insects but also in non-vertebrate chordates (such as ascidians and amphioxus; [20–22]) to the three vertebrate ERRs [23], two waves of gene duplications were necessary. The first took place before the emergence of lamprey and resulted in the separation of ERRα from an ancestor of both ERRβ and ERRγ. Indeed, in mammals these two genes are more closely related to each other than to ERRα, and furthermore, a cDNA fragment equally resembling both ERRβ and ERRγ could be isolated from lamprey (P-L Bardet and J-M Vanacker, unpublished). Before the emergence of fish, another round of gene duplication took place, separating ERRβ from ERRγ, and also ERRα from an ERRδ, the latter being lost in mammals but maintained in some fish (such as fugu and zebrafish; [17, 24]). Additional gene duplications and losses took place specifically in various fish lines [17]. In mammals, ERRs have been cloned in bovine, mouse, rat and human [15, 25–27].

Molecular properties of ERRs

Apart from mammals, only ERRs originating from D. melanogaster, amphioxus and zebrafish have been studied for their molecular properties (Table 1). All ERRs studied to date bind to and activate transcription in a seemingly constitutive manner through the estrogen-response element (ERE) and the ERR-response element (ERRE), at least in transient transfection experiments [23].

Table 1.

Conserved molecular properties of ERR receptors

| Drosophila | Amphioxus | Mammalian | Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoforms | Single gene, alternate splicing | Single gene, alternate splicing | Three genes | [15, 18, 22, 26, 30] |

| DNA binding | ERRE, ERE | ERRE, ERE | ERRE, ERE | [1, 29, 30] |

| Dimerization | n.d. | ERRE: long isoform: monomer

short isoform: dimer ERE: dimer |

ERRα/ERRE: dimer induced by phosphorylation

ERE: constitutive dimer |

[23, 30, 32] |

| Transactivation | ERRE, ERE | Depends on dimerization | Depends on dimerization | [29, 30, 32] |

| Deactivation by OHT | Requires three mutations in the LBD | yes | ERRβ and ERRγ, not ERRα | [28–29] |

footnotes: n.d., not determined

Mouse ERRβ and ERRγ, but not ERRα, can be deactivated by high doses of 4-OH-tamoxifene (OHT) a mixed anti-estrogen [28]. This differential behavior is conserved in zebrafish where ERRγ and ERRδ, but again not ERRα, are sensitive to OHT [24]. D. melanogaster ERR requires the mutation of three amino acids in its ligand-binding domain, changing them to mammalian ERRβ/γ type, to react to OHT [29]. Transactivation by amphioxus ERR, in which these three positions are identical to mouse ERRβ/γ (but not to mouse ERRα) can also be inhibited by OHT (P-L Bardet and J-M Vanacker, unpublished).

Both D. melanogaster and amphioxus ERR are expressed as two isoforms differing by the presence or absence of an in-frame alternative exon at the beginning of the ligand-binding domain [18, 30]. Functional studies in the amphioxus have revealed that the resulting long ERR isoform behaves as a dominant negative transcription factor over the short isoform, but only through the ERRE [30]. On EREs, both the long and short isoforms activate transcription. Whether this is also true for D. melanogaster ERR has not been determined. However the fact that the size and insertion point of the alternative exon are roughly similar between amphioxus and D. melanogaster suggests functional conservation, despite obvious sequence divergence. In both animals the isoforms are differentially expressed during development, with the ratio of long/short mRNA progressively rising as development proceeds [30–31].

The dimeric vs. monomeric nature of the DNA binding by mammalian ERR proteins has been a subject of debate. The long amphioxus ERR isoform binds as a monomer on and does not activate transcription through ERRE sequences whereas it homodimerizes on and activates transcription through ERE sequences [30]. This observation suggests that dimerization is required for transactivation, a hypothesis that has recently been fueled [32]. Indeed Protein Kinase C (PKC) δ-driven phosphorylation shifts the binding of human ERRα on an ERRE site from a monomeric to a dimeric state. Correlatively, PKCδ also enhances transactivation exerted by ERRα on the single ERRE of the pS2 gene promoter. In contrast the ERRα gene promoter itself, which comprises multiple ERREs (altogether forming an ERE-like DNA stretch) is constitutively activated by ERRα (i.e. in a phosphorylation-independent manner).

Parallels can therefore be drawn between amphioxus and human ERR (at least for ERRα). In both experimental systems, evidence was obtained proposing that dimerization is necessary for transactivation. Regulation of dimerization (vs. monomer state) and consequently of transactivation is conspicuous on the ERRE but not on the ERE. The modalities of this regulation seem to differ, alternative splicing for amphioxus, phosphorylation in the human. These two events thus offer the possibility, with a single orphan ERR nuclear receptor, to finely regulate the transcription of certain target genes as a function of developmental and/or physiological state in the absence of a natural ligand.

Early developmental effects of ERR genes

Expression of the unique ERR gene in D. melanogaster is detectable very early after egg laying which indicates maternal transmission of its RNA [31] (Table 2). This transcript is rapidly degraded and reappears later under various alternatively spliced isoforms. Maternal transmission of ERR RNA was also observed in the zebrafish for ERRα but not for the other ERRs, which are expressed much later [24]. As no information is available concerning the mouse ERRs before blastocyst stage, it is not known whether they are maternally transmitted. However expression of ERRα and ERRβ in embryonic stem (ES) cells indicates an early requirement [25, 33]. In contrast, ERRγ is only detectable by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) experiments at eleven days post-coitum (E11) but not at E7 [34]. In the ascidian Herdmania curvata the unique ERR is among the earliest NRs detected by PCR experiments, at the 64-cell stage (well before gastrulation) although not at the 32-cell stage [21], rendering maternal transmission unlikely. In the amphioxus, ERR expression is first detected at a later (neurula) stage [22].

Table 2.

Conserved expressions and new hypothetical functions of ERR receptors

| Drosophila | Early chordates | Zebrafish | Mouse | Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early expression | Maternal; later: enhanced by ecdysone pulse | Ascidian: morula

Amphioxus: neurula |

ERRα: maternal, related to cellular movements | ERRα and β: ES cells

ERRβ expression drops upon differentiation |

[21–22, 24– 25, 31, 33, 37] |

| Nervous system | n.d. | Motoneurons segmented in posterior brain | ERRα, β and γ: motoneurons segmented in hindbrain | ERRα and γ: differentiating motoneurons | [22, 33, 44] |

| Muscular system | n.d. | Slow muscles | ERRα: slow muscles | ERRα: slow muscles, differentiating C2C12 cells | [22, 33] |

footnote: n.d., not determined

In the mouse, expression of ERRβ in the extra-embryonic ectoderm is necessary to the formation of the placenta [35]. However, the functions of ERR genes in embryonic tissues are poorly characterized. Early developmental functions of ERRα have been studied in the zebrafish [24]. Inhibiting the activities of ERRα from very early stages (1- to 4-cell stages), using a morpholino (an antisense oligonucleotide that specifically inhibits the translation of the targeted transcript [36]) or a dominant-negative strategy results in a dramatic delay in the cellular movements (occurring 6 to 9 hours later) that precede and are necessary to gastrulation [37]. In particular, the convergence of lateral cells toward the dorsal part of the zebrafish embryo is strongly reduced upon ERRα knockdown; as a consequence the antero-posterior axis appears broader in mutant animals. Conversely, overexpressing ERRα has no effect on the above-mentioned cell convergence, but results in the perturbation of the extension of the antero-posterior axis, which consequently appears shorter. Interestingly, this phenomenon occurs in the absence of any effect on tissue determination: specific gene expressions that are characteristic of a presumptive tissue remain unaltered. In mice the requirement of ERRα for normal embryonic development does not appear as crucial. Indeed mice knocked-out for ERRα are born without any gross alteration [6]. Whereas this could suggest that the functions of the receptor during early development are different between fish and mouse, this could also indicate that the loss of ERRα in knock-out mice is compensated for by some unknown mechanisms. However the above-mentioned results point to roles for ERRα in regulating cellular movements, a broadly observed phenomenon not only during development but also in the course of various physio-pathological phenomena, such as inflammation, atherosclerosis, wound healing or cancer metastasis. The mechanism through which zebrafish ERRα exerts its effects on cellular movements is presently unknown. However osteopontin, a transcriptional target of ERRα [38], could be a possible connective link. This protein acts as a chemotaxis factor in the recruitment of inflammatory cells during atherosclerosis or rheumatoid arthritis [39–40 and ref therein] and is likely involved in metastatic behavior [41–42]. If confirmed in mammals, this movement-regulating role of ERRα could open a brand new field of investigations.

ERRs in the brain

In zebrafish, ERR genes were found co-expressed in groups of neurons in the rhombomeres (which are repeated embryonic structures) of the hindbrain during development, in a temporal sequence of appearance: first ERRγ, then β and last α [22]. It is tempting to hypothesize a cross-regulation of the expression of these receptors as has been demonstrated in human cells where ERRγ up-regulates the expression of ERRα [43]. The unique amphioxus ERR was also found expressed in the homolog of the posterior brain during development [22]. Strikingly this expression also appeared in an iterated manner labeling regularly spaced motoneuron pairs along the antero-posterior axis, although no morphological segmentation is obvious in cephalochordates. ERR thus constitutes a conserved marker of cellular/molecular segmentation even when anatomical segmentation has not yet appeared in evolution. Expression of ERRs in mammalian rhombomeres has not been investigated.

In mouse embryonic brain, ERRβ has been detected by PCR experiments [44], but its detailed expression pattern has not been documented. In contrast ERRα and ERRγ display a complex, partly overlapping expression pattern in this organ [33, 45]. ERRα is detected in the neural tube 10.5 post-coitum and its expression is enhanced when cells leave the proliferative (ventricular) zone for the intermediate zone where they differentiate into neurons. Though the roles of ERRα in the brain are unknown, one could hypothesize that ERRα is required for the cellular movements necessary to this process and/or in the control of proliferation/differentiation. ERRγ expression is also enhanced in differentiating motoneurons [45]. Altogether, ERR receptors are found in the brain in a broad range of chordate species. This should be a strong signal to investigate thoroughly their roles in this organ, which remain undetermined.

ERRs in muscles

Expression of ERRs in muscles has been demonstrated in various species. Indeed, amphioxus ERR is expressed in the dorsal parts of the somites, a population of cells that give rise to slow-twitch muscles [22]. Zebrafish ERRα is also present in the adaxial cells [24], which are also progenitors of slow-twitch muscles. In mouse, ERRα (and also ERRγ) is much more expressed in the soleus (slow-twitch) than in the vastus lateralis (fast-twitch) muscle [8]. There is thus a strong evolutionary conservation of the predominant expression of ERRα in slow vs fast muscles.

Use of lipids as a fuel and a high number of mitochondria are distinctive features of slow muscle fibers (for a review, see [46]). Mouse ERRα (acting together with its interacting partner, the coactivator PPARgammaCoactivator-1α [PGC-1α]) has been proposed to regulate lipid storage and/or consumption, as well as promoting mitochondrial biogenesis [7–9], functions that are likely to be conserved through evolution. The elevated ERRα expression in differentiating cells or their immediate precursors (adaxial cells in the zebrafish, dorsal somitic cells in the amphioxus) suggests an additional role for the receptor in differentiation, more specifically in the slow muscle lineage. This hypothesis is consistent with the demonstrated functions of PGC-1α in muscles [47]. Indeed, when overexpressed in transgenic mice, this coactivator converts fast muscles into slow ones, a phenomenon accompanied by an elevated number of mitochondria and by a corresponding switch in energy source. In addition to this, expression of amphioxus ERR in neurons appears in the same cells that innervate the slow fibers in which the receptor is also present [22]. It could thus be that amphioxus ERR not only influences the independent physiologies of slow muscles and motoneurons, but also the connections between these cell components, a hypothesis that remains to be tested.

Conclusions and future prospects

Although the molecular mechanisms of action of ERRs have recently gained understanding, the physio-pathological functions exerted by these receptors in mammals remain largely unidentified. Studies in non-mammals that include comparative analysis of expression patterns as well as determination of functions may provide clues as to which mammalian tissues/cells are targeted by the receptors. Such an “evolution-based” approach assumes that the functions of the receptor are conserved throughout the animal reign. It is tempting to propose that the near-exclusive expression of ERRα in slow- vs fast-twitch muscles in all chordates studied (amphioxus, zebrafish, mammals) provides a proof of principle to this assumption although the function of non-mammals ERR in energy homeostasis (a key function of mouse ERRα) has not been determined.

Strong (positive and negative) correlations have been observed between the expression of ERR receptors and cell proliferation and/or differentiation. In mouse, this not only includes neurons and muscle cells where expression of ERRα (and also of ERRγ in motoneurons) is elevated upon differentiation, but also ES cells in which ERRβ expression decreases upon differentiation-inducing retinoic acid treatment [25]. One or several ERR receptors acting either together or in an opposing manner may thus contribute to the regulation of proliferation and/or differentiation in different tissues. Another path to be explored originates from the demonstration, in the zebrafish, of an effect of ERRα on cellular movement. This general phenomenon is important in many physio-pathological processes that ERR receptors may thereby regulate. Whether this is also true for mammalian ERRα and/or extends to the other ERR paralogs remains to be determined, as well as the effector targets activated by these transcription factors.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Christian Jaulin and Karine Gauthier for critical reading of the manuscript. JMV wish to thank the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, the Ligue contre le Cancer, comité Drôme and Languedoc-Roussillon for funding work his lab. PLB is funded by the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer. VL thanks the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and Ministère délégué à l'Enseignement Supérieur et à la Recherche.

Contributor Information

Pierre-Luc Bardet, Mammalian Development MRC, GB.

Vincent Laudet, Laboratoire de biologie moléculaire de la cellule CNRS : UMR5161, INRA, Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon, 46 Allée d'Italie 69364 LYON CEDEX 07,FR.

Jean-Marc Vanacker, Genotypes et Phenotypes Tumoraux INSERM : E229, Université Montpellier I, Crlc Val D'Aurelle - Paul Lamarque Parc Euromedecine 34298 MONTPELLIER CEDEX 5,FR.

References

- 1.Giguère V. To ERR in the estrogen pathway. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:220–225. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ariazi EA, et al. Estrogen-related receptor α and estrogen-related receptor γ associate with unfavorable and favorable biomarkers, respectively, in human breast cancer. Canc Res. 2002;62:6510–6518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki T, et al. Estrogen-related receptor α in human breast carcinoma as a potent prognostic factor. Canc Res. 2004;64:4670–4676. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavallini A, et al. OEstrogen receptor-related receptor alpha (ERRα) and oestrogen receptors (ERα and β) exhibit different gene expression in human colorectal tumour progression. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1487–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun P, et al. Expression of estrogen receptor-related receptors, a subfamily of orphan nuclear receptors, as new biomarkers in ovarian cancer cells. J Mol Med. 2005;83:457–467. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0639-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo J, et al. Reduced fat mass in mice lacking orphan nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor α. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7947–7956. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.7947-7956.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreiber SN, et al. The estrogen-related receptor α (ERRα) functions in PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α)-induced mitochondrial biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6472–6477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308686101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huss JM, et al. Estrogen-related receptor α directs peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α signaling in the transcriptional control of energy metabolism in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9079–9091. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.9079-9091.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mootha VK, et al. ERRα and Gabpa/b specify PGC-1α-dependent oxidative phosphorylation gene expression that is altered in diabetic muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6570–6575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401401101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams MD, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:2185–95. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson-Rechavi M, et al. How many nuclear hormone receptors are there in the human genome? Trends Genet. 2001;17:554–556. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giguère V. Orphan nuclear receptors: from gene to function. Endocrine Rev. 1999;20:689–725. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.5.0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Escriva H, et al. Ligand binding was acquired during evolution of nuclear receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6803–6808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laudet V. Evolution of the nuclear receptor superfamily: early diversification from an ancestral orphan receptor. J Mol Endocrinol. 1997;19:207–226. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0190207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giguère V, et al. Identification of a new class of steroid hormone receptors. Nature. 1988;331:91–94. doi: 10.1038/331091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thornton JW, et al. Resurrecting the ancestral steroid receptor: ancient origin of estrogen signaling. Science. 2003;301:1714–1717. doi: 10.1126/science.1086185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertrand S, et al. Evolutionary genomics of nuclear receptors: from twenty-five ancestral genes to derived endocrine systems. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1923–1937. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maglich JM, et al. Comparison of complete nuclear receptor sets from the human, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila genomes. Genome Biology. 2001;2:0029.1–0029.7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-8-research0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson-Rechavi M, et al. Explosive lineage-specific expansion of the orphan nuclear receptor HNF4 in nematodes. J Mol Evol. 2005;60:577–586. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dehal P, et al. The draft genome of Ciona intestinalis: insights into chordate and vertebrate origins. Science. 2002;298:2157–2167. doi: 10.1126/science.1080049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devine C, et al. Evolution and developmental expression of nuclear receptor genes in the ascidian Herdmania. Int J Dev Biol. 2002;46:687–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bardet PL, et al. Expression of estrogen-receptor related receptors in amphioxus and zebrafish: implications for the evolution of posterior brain segmentation at the invertebrate-to-vertebrate transition. Evol Dev. 2005;7:223–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2005.05025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horard B, Vanacker JM. Estrogen-receptor related receptors: orphan receptors desperately seeking ligands. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;31:349–357. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0310349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bardet PL, et al. Cloning and developmental expression of five estrogen-receptor related genes in the zebrafish. Dev Genes Evol. 2004;214:240–249. doi: 10.1007/s00427-004-0404-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettersson K, et al. Expression of a novel member of estrogen response element binding nuclear receptor is restricted to the early stages of chorion formation during mouse embryogenesis. Mech Dev. 1996;54:211–223. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong H, et al. Hormone-independent transcriptional activation and coactivator binding by novel orphan nuclear receptor ERR3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22618–22626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connor EE, et al. Chromosomal mapping and quantitative analysis of estrogen-related receptor alpha-1, estrogen receptors alpha and beta and progesterone receptor in the bovine mammary gland. J Endocrinol. 2005;185:593–603. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coward P, et al. 4-hydroxytamoxifen binds to and deactivates the estrogen-related receptor gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8880–8884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151244398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Östberg T, et al. A triple mutant of the Drosophila ERR confers ligand-induced suppression of activity. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6427–6435. doi: 10.1021/bi027279b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horard B, et al. Dimerization is required for transactivation by estrogen-receptor-related (ERR) orphan receptors: evidence from amphioxus ERR. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33:493–509. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan AA, Thummel CS. Temporal profiles of nuclear receptor gene expression reveal coordinate transcriptional responses during Drosophila development. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2125–2137. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barry JB, Giguère V. Epidermal growth factor-induced signaling in breast cancer cells results in selective target gene activation by orphan nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor α. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6120–6129. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonnelye E, et al. Expression of the estrogen-related receptor 1 (ERR-1) orphan receptor during mouse development. Mech Dev. 1997;65:71–85. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Süsens U, et al. Alternative splicing and expression of the mouse estrogen-receptor-related γ. Bioch Biophys Res Comm. 2000;267:532–535. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo J, et al. Placental abnormalities in mouse embryos lacking the orphan nuclear receptor ERRβ. Nature. 1997;388:778–782. doi: 10.1038/42022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nasevicius A, Ekker SC. Effective targeted gene 'knockdown' in zebrafish. Nat Genet. 2000;26:216–220. doi: 10.1038/79951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bardet PL, et al. The ERRα orphan nuclear receptor controls morphogenetic movements during zebrafish gastrulation. Dev Biol. 2005;281:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vanacker JM, et al. Activation of the osteopontin promoter by the orphan nuclear receptor ERRα. Cell Growth and Diff. 1998;9:1007–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruemmer D, et al. Angiotensin II- accelerated atherosclerosis in osteopontin-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1318–1331. doi: 10.1172/JCI18141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu G, et al. Role of osteopontin in amplification and perpetuation of rheumatoid synovitis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1060–1067. doi: 10.1172/JCI23273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rudland PS, et al. Prognostic significance of the metastasis-associated protein osteopontin in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3417–3427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mi Z, et al. Differential osteopontin expression in phenotypically distinct subclones of murine breast cancer cells mediates metastatic behavior. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46659–46667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu D, et al. Estrogen-related receptor γ and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α regulate estrogen-related receptor-α gene expression via a conserved multi-hormone response element. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;34:473–487. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitsunaga K, et al. Loss of PGC-specific expression of the orphan nuclear receptor ERR-β results in reduction of germ cell number in mouse embryos. Mech Dev. 2004;121:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hermans-Borgmeyer I, et al. Developmental expression of the estrogen receptor-related receptor γ in the nervous system during mouse embryogenesis. Mech Dev. 2000;97:197–199. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berchtold MW, et al. Calcium ion in skeletal muscle: its crucial role for muscle function, plasticity and disease. Phys Rev. 2000;80:1215–1265. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin J, et al. Trancriptional co-activator PGC-1α drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature. 2002;418:797–801. doi: 10.1038/nature00904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]