Abstract

Fewer than a hundred cases of paroxysmal dystonia have been described in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). Even fewer cases of hemidyskinesia triggered by repetitive movements (paroxysmal kinesigenic hemidyskinesia - PKD) have been reported in MS patients. We describe the case of a woman, age 18 years at the onset of MS, and a man age 35 years at the onset of MS, who presented with PKD as the initial symptom. Magnetic resonance images (MRI) of these patients showed different areas of acute lesions possibly related to PKD; MRI of one of the patients demonstrated 1 lesion in the subcortical parietal area and another in the thalamic region and showed 2 lesions in the cervical spinal cord in the other patient.

Introduction

Except for tremor, movement disorders are relatively rare in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).[1] Since the classic review of 83 cases of paroxysmal dystonia (PD) in MS described by Tanchant and colleagues in 1995,[1] fewer than 20 cases have been reported.

PD can be classified according to precipitating factors, phenomenology, duration of attacks, and etiology.[2] Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (PKD) consists of sudden attacks of involuntary movements precipitated by sudden or repetitive movements,[2] or startling noise.[1] These attacks are typically short-lasting (up to 5 minutes), frequent (up to 100 times per day), and usually unilateral. They may be disabling, interfering with walking, working, and daily activities.[3] Before the onset of these attacks, some patients report tingling or paresthesia in the affected limb. These phenomena are called “sensory aura,” and they led to an earlier theory that these were a form of partial epileptic seizure.[2]

PKD has been described in only a few patients with MS, and rarely as the presenting symptom of the disease.[1] PKD has not yet been associated with lesions in a definite area of the central nervous system. Indeed, the distribution of MS plaques in patients with PKD were as diverse as the cervical and thoracic spinal cord, midbrain, thalamus, periaqueductal region, internal capsule, and cerebral peduncle.[1]

We report 2 new cases of PKD as the presenting symptom of MS, with magnetic resonance image (MRI) showing plaques in different locations. Both cases were fully investigated in order to exclude other diagnoses, according to the protocol for Reference Centers on MS of the Ministry of Health in Brazil.

Case 1 Presentation

The first patient was a 35-year-old white man who worked as a manual laborer at a factory. Nine months before the initial consultation, the patient experienced several episodes of “painful cramps” in his right leg while walking fast. His right knee and elbow would then take on a flexed position which lasted roughly 1 minute. These attacks were diagnosed at another service as reflex partial epilepsy and the patient was prescribed carbamazepine 800 mg/day, with partial improvement. Brain computed tomography scan and electroencephalogram were normal. Five months later, while working with a pipe, performing a repetitive “rolling” movement of his wrists and hands, the painful cramp and flexed position of the right knee and elbow reappeared.

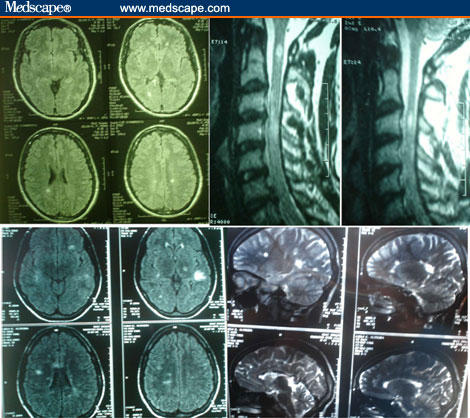

At no time in his history did he experience more than a couple of attacks in a day, and 2 to 3 days could pass without any attacks. When he was referred to our service, we performed MRI of the brain and spinal cord, and spinal fluid analysis. A few demyelinating lesions were observed in the brain (Figure, top), and 2 large lesions were seen in the cervical spinal cord (Figure, top). The spinal fluid showed elevated protein levels and a high percentage of gamma-globulin and IgG, with the presence of oligoclonal bands. The symptoms improved with pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone. The patient was started on glatiramer acetate and remained asymptomatic for 18 months. Subsequently, he developed blurred vision in the right eye, left hemiparesis, and severe dizziness. Another session of pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone led to complete remission of these symptoms. He has now been symptom-free for 8 months.

Case 2 Presentation

The second patient was an 18-year-old white woman who was a university student and soccer player. One month before the initial consultation in our service, the patient observed a very mild degree of weakness in her right leg while playing soccer. During the following few days she noted that any sudden movement, startling noise, or repetitive movements (such as brushing teeth or combing hair) could trigger attacks of a prickly sensation in her right arm and leg, followed by painful cramps in her right wrist, fingers, ankle, and toes. These attacks lasted approximately 2 minutes and occurred as often as 30 times a day, giving rise to difficulties in writing, sporting activities, walking, or performing any tasks that would involve repetitive or sudden movements. She occasionally was awakened by such attacks, although this was rare.

An MRI of her brain showed several demyelination plaques, with a particularly large one in the subcortical area of the parietal lobe with clear enhancement by gadolinium (Figure, bottom). Another plaque of possible interest for the case was detected in the left thalamic area (Figure, bottom). Her spinal fluid analysis showed normal protein levels, with elevated gamma-globulin and IgG. Oligoclonal bands were present.

We prescribed high does of oral prednisone, which resulted in complete remission of these symptoms within 10 days. After 50 days, the patient presented with hypoesthesia of the right side of her face and blurred vision in the left eye. Another session of oral prednisone rendered her asymptomatic within a week. She was prescribed glatiramer acetate and was symptom-free for 6 months. She then suffered another relapse of the disease, with right hemiparesis, dysphagia, dysarthria, and blurred vision in the left eye. Her MRI showed several new lesions in the subcortical, paraventricular areas, and in the cerebellum. We administered high-dose intravenous methylprednisonolone and changed her immunomodulatory treatment to high dose beta-interferon. She experienced a full recovery and has been asymptomatic for 3 months.

Discussion

PKD is an uncommon presentation of MS, and we believe that the 2 cases presented here contribute to expansion of the body of knowledge presented in the literature. The relatively similar clinical presentations of these 2 cases with such different locations of the demyelinating lesions corroborate the 30-year-old hypothesis of Osterman and Wertenberg.[4] These authors suggested that PD in MS could be explained by nonsynaptic, ephaptic transmission of axons at any level of the motor pathway, a theory also supported by Tranchant and[1]

PKD can manifest as a consequence of a variety of clinical conditions, such as congenital dystonia, trauma, stroke,[3] arteriovenous malformation in the parietal lobe,[5] and cryptogenic myelitis.[6] The few cases of PKD in MS reported in the literature have shown several different lesion sites.[1,7–16] Neither we nor the previous authors are certain that the lesions identified by the MRI are indeed related to the symptoms, but we have been encouraged to report all cases of PD in MS patients.[1]

It is difficult to justify how the same symptom could be related to so many different lesion sites. Some have suggested that the proximity of the motor fibers could be an important underlying anatomical factor.[17] This would allow a single lesion to have an effect on a large population of axons, and would also favor radial spreading of ephaptic activation.[17] Perhaps preservation of the underlying pyramidal tract is essential for PKD to be manifested. This would allow the pathologic discharge to reach the peripheral effectors and generate PKD.[17]

The sites of the lesions in these 2 patients were unusual. The first presented with 2 lesions at a high level of the cervical cord, and the second presented with a subcortical parietal lesion and a thalamic lesion. A subcortical parietal lesion has only been described in a case of PKD associated with arteriovenous malformation;[5] thalamic lesions in MS with PKD have been described in 2 cases.[11,12] Again, one must be cautious and avoid conclusions regarding the site of the MS lesion and the manifested symptoms, but it is only by studying and reporting more cases of PD and MS that we can learn more.

Finally, our finding of different clinical characteristics of PKD (such as frequency and duration of attacks) could give rise to a debate on whether the different lesion sites of these MS patients could account for these clinical variations.

Figure.

MRI images of 2 cases. Top: Case 1. Male, 35 years old, with PKD as the initial manifestation of MS. Two prominent lesions in the cervical spinal cord. Few lesions in the brain. Bottom: Case 2. Female, 18 years old, with PKD as the initial manifestation of MS. Several lesions in the brain, including one in the deep left parietal area and another in the left thalamus.

Contributor Information

Yara Dadalti Fragoso, Department of Neurology, Universidade Metropolitana de Santos, SP, Brazil; email: yara@bsnet.com.br.

Mauro Gomes Araujo, Department of Neurology, Universidade Metropolitana de Santos, SP, Brazil.

Nilton Luiz Branco, Santos, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Tranchant C, Bathia KP, Marsden CD. Movement disorders in multiple sclerosis. Mov Disord. 1995;10:418–423. doi: 10.1002/mds.870100403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jankovic J, Demirkýran M. Paroxysmal dyskinesias: an update. Ann Med Sci. 2001;10:92–103. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demirkiran M, Jankovic J. Paroxysmal dyskinesias: clinical features and a new classification. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:571–579. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osterman PO, Westerberg CE. Paroxysmal attacks in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1975;98:189–202. doi: 10.1093/brain/98.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shintani S, Shiozawa Z, Tsunoda S, Shiigai T. Paroxysmal choreoathetosis precipitated by movement, sound and photic stimulation in a case of arterio-venous malformation in the parietal lobe. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1991;93:237–239. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(05)80011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonev VI, Gledhill RF. Paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis because of cryptogenic myelitis. Remission with carbamazepine and the pathogenetic role of altered sodium channels. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9:517–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honig LS, Wasserstein PH, Adornato BT. Tonic spasms in multiple sclerosis. Anatomic basis and treatment. West J Med. 1991;154:723–726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cosentino C, Torres L, Flores M, et al. Paroxysmal kinesigenic dystonia and spinal cord lesion. Mov Disord. 1996;11:453–455. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riley DE. Paroxysmal kinesigenic dystonia associated with a medullary lesion. Mov Disord. 1996;11:738–740. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yucesan C, Tuncel D, Akbostanci MC, Yucemen N, Mutluer N. Hemidystonia secondary to cervical demyelinating lesions. Eur J Neurol. 2000;7:563–566. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2000.t01-1-00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zenzola A, De Mari M, De Blasi R, Carella A, Lamberti P. Paroxysmal dystonia with thalamic lesion in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2001;22:391–394. doi: 10.1007/s100720100070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burghera JA, Catala J, Casanova B. Thalamic demyelination and paroxysmal dystonia in multiple sclerosis. Mov Disord. 1991;6:379–381. doi: 10.1002/mds.870060423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waubant E, Paul Alizé P, Tourbah A, Agid Y. Paroxysmal dystonia (tonic spasm) in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2001;57:2320–2321. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.12.2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minagar A, Sheremata WA, Weiner WJ. Transient movement disorders and multiple sclerosis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002;9:111–113. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(02)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blakeley J, Jankovic J. Secondary paroxysmal dyskinesias. Mov Disord. 2002;17:726–734. doi: 10.1002/mds.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan JC, Hughes M, Figueroa RE, Sethi KD. Psychogenic paroxysmal dyskinesia following paroxysmal hemidystonia in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;65:E12. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000170367.33505.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spissu A, Cannas A, Ferrigno P, Pelaghi AE, Spissu M. Anatomic correlates of painful tonic spasms in multiple sclerosis. Mov Disord. 2001;14:331–335. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199903)14:2<331::aid-mds1020>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]