Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common childhood disease that can disrupt the lives of patients and their families and, in turn, affect their quality of life. The goal of treatment is the long-term control of AD by minimizing the frequency and severity of flares. Topical corticosteroids of various potencies have been the mainstay of pharmacologic treatment of AD flares. In the past few years, the introduction of topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) has provided physicians with an effective, well-tolerated alternative to topical corticosteroids. In January 2006, a boxed warning and a patient medication guide were added to TCI product labels in the United States after the US Food and Drug Administration raised concerns about their safety. These concerns were based on rare cases of skin malignancy and lymphoma, and a theoretical risk stemming from the systemic use of calcineurin inhibitors in animal studies and transplant patients. However, the boxed warning states that no causal link has been established between TCI use and malignancy. Pharmacokinetic studies have also shown that treatment with TCIs leads to only minimal systemic absorption. In addition, controlled, blinded studies have found no evidence of systemic immunosuppression and no causal relationship between the use of TCIs and the occurrence of lymphoma or other malignancies. Overall, TCIs have been shown to be an effective and valuable treatment option for AD.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic inflammatory skin condition that frequently develops in infancy or early childhood.[1] Epidemiologic studies have shown that AD affects between 10% and 20% of children and between 1% and 3% of adults.[2,3] In 85% of cases, the first signs and symptoms of AD appear before age 5 years.[4]

AD is characterized by episodic flares of pruritus, erythema, excoriation, and papulation that can be initiated by a variety of environmental and allergen triggers.[1,5] AD flares are classified as mild, moderate, or severe on the basis of the degree and severity of these common symptoms.[6] A severe flare, also referred to as a major flare, is characterized by severe pruritus, erythema, and excoriation, as well as by crusting and oozing in very severe cases. Patients with AD also appear to have an impaired skin-barrier function, which may lead to persistent xerosis and increased susceptibility to potential irritants, allergens, or infectious agents.[7] AD flares are a result of a cutaneous inflammatory response. More specifically, analysis of affected skin suggests that activated CD4-positive T cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of AD.[1,8]

AD management utilizes nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches to achieve long-term control of eczema. The approach that is chosen depends on accurate assessment of the extent, severity, and chronicity of symptoms.[9,10] Frequently, patients need to use several nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic agents to manage their disease. Although good skin care forms the basis of any AD treatment regimen, many patients require pharmacologic treatment to manage their disease. In most cases, treatment of AD is primarily topical. In recent years, topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs; tacrolimus ointment 0.03% and 0.1% [Protopic] and pimecrolimus cream 1% [Elidel]) have become mainstays in AD treatment.

However, the safety of topical corticosteroids and TCIs has been reevaluated. In October 2003, Pediatric Advisory Committee (PAC) meetings were conducted at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to discuss the risk for hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppression in children with AD treated with topical corticosteroids and to debate the malignancy risk in children with AD treated with TCIs. As a result of this and subsequent meetings with regard to TCIs, the FDA added a boxed warning and a patient medication guide to TCI product labels in January 2006. These changes were made to inform healthcare providers and patients about the Committee's concern of a theoretical skin malignancy and lymphoma risk associated with long-term use of TCIs. However, the warning states that neither long-term safety nor a causal relationship has been established.[11,12] The purpose of this review is to discuss the use of TCIs in the treatment of AD, with a particular focus on their safety profile.

TCIs for Treatment of AD

The safety and efficacy of TCIs have been studied extensively in children and adults with AD in short- and long-term trials.[13,14] TCIs target the underlying inflammatory pathogenesis of AD. They bind macrophilin-12 (FKBP-12) and inhibit calcineurin activity, preventing the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-activated T cells.[15] As a result, T-cell activation and the subsequent production and release of proinflammatory cytokines are inhibited.[15] In addition, TCIs have been shown to inhibit the release of proinflammatory mediators from mast cells.[15–17] This inhibition of the inflammatory response of AD reduces eczema symptoms, including pruritus.[13,14]

Tacrolimus Ointment 0.03% and 0.1%

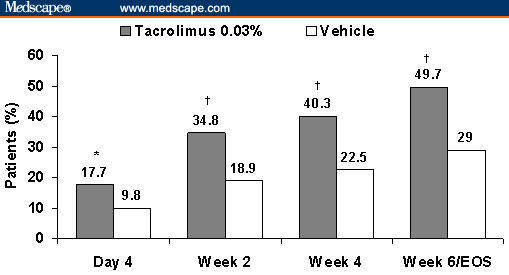

In the United States, tacrolimus ointment 0.03% and 0.1% is indicated for adults, whereas tacrolimus ointment 0.03% is indicated for children aged 2–15 years. The indication, which was revised in January 2006, states that tacrolimus should be used as second-line therapy for short-term and noncontinuous chronic treatment of moderate-to-severe AD in nonimmunocompromised adults and children aged ≥ 2 years who have failed to respond adequately to other topical prescription treatments or when those treatments are not advisable.[12] Several studies in children and adults have demonstrated that tacrolimus ointment effectively reduces the frequency of AD flares and treats the disease (measured by the Investigator's Global Assessment [IGA] score) as well as its accompanying symptoms (Figure 2).[18–23] A head-to-head comparison with topical corticosteroids showed comparable efficacy between tacrolimus ointment 0.1% and the midpotency corticosteroid hydrocortisone butyrate 0.1%.[24] A similar comparison in children showed that tacrolimus ointment (0.03% and 0.1%) was more effective than the over-the-counter corticosteroid hydrocortisone acetate 1%.[25]

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients achieving success of therapy (defined as “clear” or “almost clear” on the basis of the Investigator's Global Assessment) in 2 independent, randomized, double-blind studies of tacrolimus ointment 0.03% vs vehicle in the treatment of pediatric (2–15 years of age) and adult (≥ 16 years of age) patients with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis covering 2% to 30% of total body surface area (end of study; *P = .003, †P < .001). Reprinted with permission from J Am Acad Dermatol.[22] Copyright 2005, Mosby.

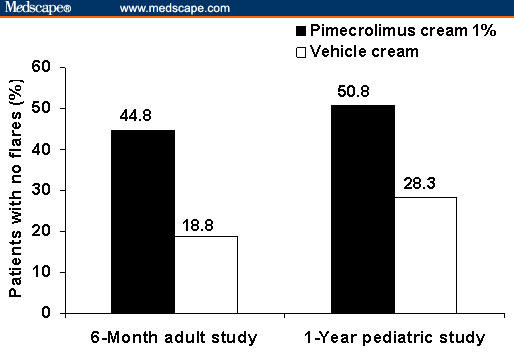

Pimecrolimus Cream 1%

Similarly, pimecrolimus cream 1% is indicated as second-line therapy for the short-term and noncontinuous chronic treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in nonimmunocompromised adults and children aged ≥ 2 years who have failed to respond adequately to other topical prescription treatments or when those treatments are not advisable.[11] In clinical trials, pimecrolimus cream 1% was significantly more effective in treating the symptoms of eczema compared with vehicle cream.[26–29] Clinical studies have also demonstrated that early treatment with pimecrolimus cream 1% significantly increases the time between flares (defined as disease that requires treatment with a topical corticosteroid), reduces the frequency of flares, and reduces the need for topical corticosteroids (Figure 3).[27,28] In head-to-head trials comparing pimecrolimus cream 1% with topical corticosteroids (eg, 0.1% betamethasone-17-valerate cream, 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide cream, or 1% hydrocortisone acetate), pimecrolimus was well tolerated and effectively treated AD symptoms.[30,31] Two studies by Luger and colleagues,[30,31] in patients with moderate-to-severe AD, showed that pimecrolimus cream 1% was not more effective than the topical corticosteroids, although pimecrolimus was an effective corticosteroid-sparing drug. In these studies, approximately 42% of patients who were treated with pimecrolimus were successfully maintained for 1 year without using topical corticosteroids.[30,31]

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients in a 6-month study in adults (N = 192) and a 1-year study in children aged 2–17 years (N = 713) who were treated with pimecrolimus cream 1% who had no flares throughout the entire study period compared with patients in the control group who were treated with vehicle cream. Adapted with permission from Dermatology and Pediatrics.[27,28] Copyright 2002, American Academy of Pediatrics. Copyright 2005, Karger.

Safety Profile of TCIs

TCIs have a favorable safety profile. The most common adverse events are mild-to-moderate application-site reactions, including skin burning, stinging, pruritus, and erythema (Table 1).[20,26,27,32] Generally, the overall adverse-event profiles of both TCIs and their vehicle are similar. Compared with topical corticosteroids, TCIs have not been found to induce skin atrophy or HPA axis suppression.[12,13,21,33,34] A single study showed a slight increase in total viral skin infections with pimecrolimus vs the control group; however, this did not reach statistical significance.[27] TCIs can be applied to all skin surfaces, including the neck and face (areas frequently affected in children with AD) and intertriginous areas, compared with midpotency to high-potency topical corticosteroids, which may have a higher level of absorption in these sensitive skin areas.

Table 1.

| Tacrolimus Ointment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tacrolimus Ointment | Vehicle | ||

| Application-Site Burning (%) | 0.03% | 0.1% | |

| 12-week pediatric trial (N = 351) | 42.7 | 33.4 | 29.0 |

| 12-week adult trial (N = 631) | 45.6 | 57.7 | 25.8 |

| Pimecrolimus Cream 1% | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pimecrolimus | Vehicle | |

| 6-week pediatric trial (N = 403) | 10.4 | 12.5 |

| 6-month adult trial (N = 192) | 10.4 | 3.1 |

The TCI label changes (revised indication and the addition of a boxed warning and patient medication guide) arose from the FDA's concern about a theoretical cancer risk. This concern is based on adverse-effect data from high-dose and prolonged use of oral calcineurin inhibitors for posttransplant immunosuppression, high-dose toxicology studies in animal models, and rare cases of lymphoma and skin malignancy reported in postmarketing surveillance. The FDA-approved boxed warning states that a causal relationship has not been established between the rare cases of malignancy reported and the use of TCIs. However, the label does reiterate that TCIs should not be used for continuous long-term treatment in any age group and that they are not indicated for use in children aged < 2 years. To date, no evidence suggests a causal link between TCI use and malignancy on the basis of extensive safety, pharmacokinetic and toxicology data, and clinical experience with millions of patients.[35,36]

Low Systemic Exposure to TCIs

Pharmacokinetic data showed that when TCIs are applied to the affected skin, systemic absorption is low compared with orally administered tacrolimus.[37–40] After oral administration of a 5-mg dose of tacrolimus in healthy volunteers, the mean maximum plasma concentration was 29.7 mg/mL.[41] In transplant recipients, even higher systemic levels may be seen after oral/intravenous administration, depending on dose and the type of transplant.[41] In contrast, topical tacrolimus has a low potential for systemic absorption. In 92% of blood samples taken from 39 children with moderate-to-severe AD, the tacrolimus concentration was < 1 ng/mL.[39] In adults with moderate-to-severe AD, 76% of patients had a maximum tacrolimus blood concentration < 1 ng/mL.[40] In pharmacokinetic studies, in patients who had detectable systemic levels of tacrolimus after topical administration, the highest area under the concentration-time curve (AUC0–24 h) was 20.4 nghour/mL in adult patients.[38,42] This value constitutes the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) for tacrolimus.

Likewise, low systemic absorption of topical pimecrolimus has also been observed in animal and human studies. In an animal model, small amounts of the applied dose of pimecrolimus were absorbed into the dermis, and most of this dose remained in the outermost layer of the skin, the stratum corneum. Only 0.2% of the applied molecule reached the dermis, and negligible amounts entered the systemic circulation.[37,38] In 67% of children with moderate-to-severe AD (up to 92% of body surface area affected), pimecrolimus blood levels were undetectable at < 0.5 ng/mL, and in 97%, levels were < 2.0 ng/mL.[37,38, 43–46] Among patients who had detectable systemic levels of pimecrolimus after topical administration, the MRHD (AUC0–24 h) was 37.6 ngh/mL and 22.8 ngh/mL for pediatric and adult patients, respectively.[38]

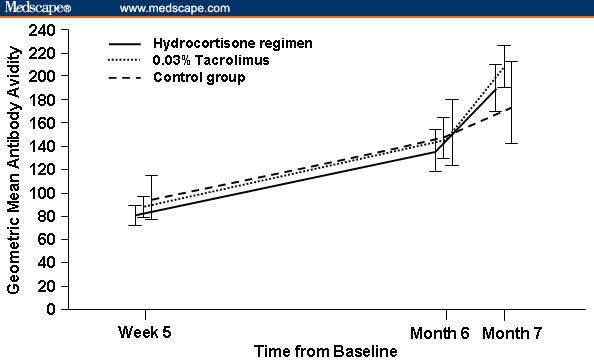

No Evidence of Systemic Immunosuppression With TCIs

Evidence of the absence of systemic immunosuppression by TCIs was based on several criteria. Studies with tacrolimus ointment showed no effect on cell-mediated immunity or antibody-mediated response to vaccination and no increased rate of cutaneous infection (Figure 4).[47–49] Similarly, no evidence of pimecrolimus affecting B-cell-mediated vaccine response or T-cell-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity and no increase in the rate of systemic infections have been reported in the medical literature (Table 2).[27,50,51] Systemic immunosuppression requires sustained levels of an immunosuppressive agent in the blood, which have not been observed in patients receiving TCIs. Considering that the level of systemic exposure of TCIs is very low and systemic immune function is preserved, it is not surprising that a causal relationship has not been established between use of TCIs and the development of any type of malignancy, including skin malignancy and lymphoma.

Figure 4.

No effect of treatment with tacrolimus 0.03% or hydrocortisone ointment on the immediate response or on T-cell-dependent antibody response after vaccination in children (2–11 years of age) with moderate-to-severe AD. Reprinted with permission from Arch Dis Child.[49] Copyright 2006, British Medical Association.

Table 2.

No Effect of Pimecrolimus Treatment on Delayed-Type Hypersensitivity. In a 1 Year Study, Response to Recall Antigens Was Not Significantly Different Between Control and Pimecrolimus-Treated Patients*

| Skin Antigen | Pimecrolimus n = 82 (%) | Control n = 30 (%) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetanus | 63.4 | 60.0 | .826 |

| Diphtheria | 42.7 | 23.3 | .079 |

| Streptococcus | 7.3 | 0.0 | .190 |

| Tuberculin | 17.1 | 13.3 | .776 |

| Candida | 13.4 | 3.3 | .176 |

| Trichophyton | 8.5 | 10.0 | .726 |

| Proteus | 18.3 | 6.7 | .151 |

| Negative control | 3.7 | 0.0 | .563 |

| 1 positive antigen | 73.0 | 67.0 | .820 |

Reprinted with permission from Pediatrics.[27] Copyright 2002, American Academy of Pediatrics

P value from time to first occurrence analysis (log-rank test)

Reports of Malignancies in Clinical Trials

As a class, TCIs have been studied extensively in clinical trials, and practitioners have broad clinical experience treating millions of patients. Overall, the rate of malignancy in patients who have been treated with TCIs is no more than what is expected in the general population, even when taking underreporting into account.[36] More specifically, in clinical trials of tacrolimus, there have been no reports of malignancy (lymphoma or skin cancer) or lymphoproliferative disease.[52] In the > 21,000 patients who were treated with pimecrolimus cream 1% in clinical trials, 2 malignancies have been reported (1 squamous cell carcinoma, 1 colon cancer). In contrast, 5 malignancies have been reported in the approximately 4000 patients in the control groups in these clinical trials. These malignancies included gastric cancer, melanoma, malignant histiocytosis, and leukemia in patients who received topical corticosteroids, and thyroid cancer in patients who received vehicle cream only.[37,38]

In clinical practice, it is estimated that > 11 million patients have been treated worldwide with tacrolimus ointment or pimecrolimus cream 1% since their approval in 2000 and 2001, respectively. Postmarketing surveillance has not revealed any increased risk for malignancy, including lymphoma and skin cancer, in patients treated with TCIs when compared with an analysis of data in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.[37,52] The age-adjusted incidence rate of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, with SEER cancer registries from 1973 to 2001, is 16.7 cases per 100,000 patient-years. Specifically, the total exposure in the United States with pimecrolimus cream 1% is > 733,000 person-years, with the most exposure time occurring in children.[37] It may be difficult to assess the true risk for malignancy with TCIs because it is difficult to quantify total TCI use, and there is also a potential for underreporting of cases. However, the trend indicates no link between TCI use and lymphoma.

Before the TCI label changes, an independent panel of experts (specialties included dermatology, epidemiology, and oncology) evaluated the lymphoma cases.[53] The panel concluded that there was “no clear link” between TCI use and lymphoma, partly because the reported cases of lymphoma do not match the type of lymphomas that have been seen with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD). The majority of lymphoma cases associated with PTLD present in unusual locations and have a polymorphic-related, B-cell-related, and Epstein-Barr virus-related pathology.[53] In addition, about half of all PTLD-related lymphomas regress after cessation of immunosuppressive therapy.[53] Also, it is important to note that due to an overlap in clinical presentation between cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and AD, reported cases of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in patients who have been treated with TCIs may represent a potential initial misdiagnosis.

At the time of the label changes, no cases of skin cancer had been reported in pediatric patients during postmarketing surveillance of TCIs; however, an increased risk for skin malignancy following sun exposure was noted in patients who have been treated with systemic calcineurin inhibitors (ie, cyclosporine A and tacrolimus).[54] Although this increased risk for skin malignancy is generally believed to be the result of systemic immune suppression by these agents, recent in vitro studies suggested that local effects (ie, inhibition of DNA repair and apoptosis) might also play a role.[55] This hypothesis was not supported by murine studies in which topically administered tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, pimecrolimus cream 1%, or vehicle protected against ultraviolet light-induced DNA damage.[54] In another study that evaluated the effects of topical tacrolimus on skin carcinogenesis, 117 mice were pretreated with 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) dissolved in acetone and/or 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), which are known tumor initiators. This study showed that subsequent treatment with topical tacrolimus ointment 0.1% increased the induction of skin tumors, particularly benign papillomas, not squamous cell carcinomas.[56] Additional long-term safety studies as well as patient registries are ongoing to further establish the safety profile of TCIs.

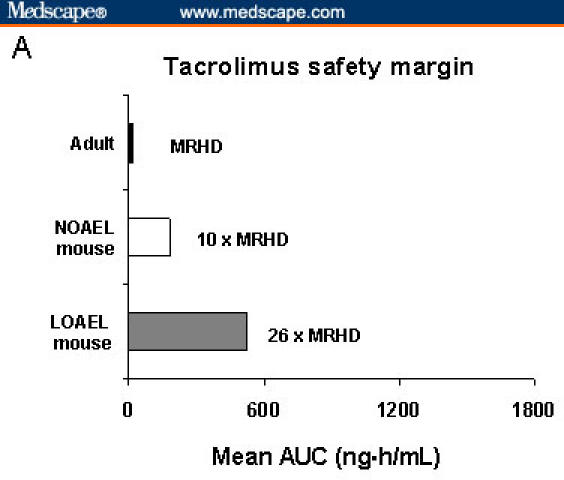

Toxicology of Calcineurin Inhibitors in Animal Models

In a 2-year dermal carcinogenicity study in mice that were treated with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% and 0.03%, the incidence of skin malignancies was minimal and topical application was not associated with skin-tumor formation.[12] In that same study, pleomorphic and undifferentiated lymphomas were noted in mice that were treated with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, at 26 times the MRHD, whereas no lymphomas were noted in mice that were treated with tacrolimus ointment 0.03%, which corresponds to 10 times the MRHD (Figure 5).[38,42]

Figure 5.

Mean area under the time-concentration curves of tacrolimus and pimecrolimus in animal and human studies. International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Guidelines: Maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) (highest mean exposure) of 25 times or greater represents an adequate safety margin. In murine toxicology studies, no malignancies were observed with exposure to tacrolimus ointment 0.03% at 10 times the MRHD; at 26 times the MRHD, lymphoma was seen with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.[12,37,57] NOAEL = no observed adverse-effect level; LOAEL = lowest observed adverse-effect level.

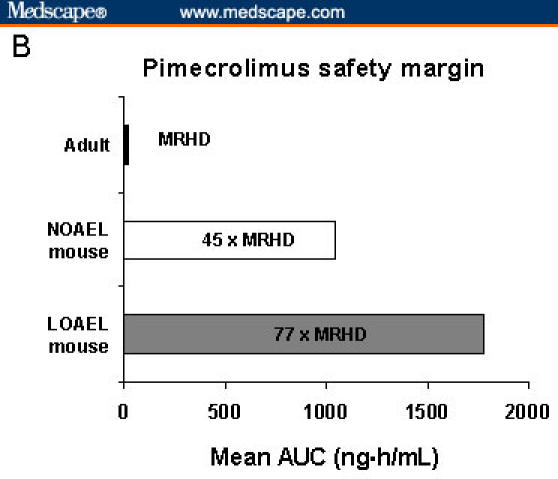

Carcinogenicity studies of pimecrolimus in mice have also failed to demonstrate an increased risk for malignancy. In a mouse dermal carcinogenicity study with pimecrolimus in an ethanolic solution, no malignancies were seen in mice that were exposed long term (2 years) at 27 times and 45 times the highest AUC that has ever been observed for pediatric and adult patients, respectively (Figure 6).[37,38,42] Lymphomas have been noted in mice exposed at 77 times the MRHD for pimecrolimus cream 1%, when dissolved in ethanolic solution to enhance penetration (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Mean area under the time-concentration curves (AUCs) of tacrolimus and pimecrolimus in animal and human studies. International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Guidelines: Maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) (highest mean exposure) of 25 times or greater represents an adequate safety margin. No malignancies were observed in mice that were treated for 2 years with exposure to pimecrolimus at 45 times the MRHD in adult patients; at 77 times the MRHD, lymphoma was seen.[12,37,57] NOAEL = no observed adverse-effect level; LOAEL = lowest observed adverse-effect level.

Additionally, toxicology studies of oral tacrolimus and pimecrolimus have been conducted in cynomolgus monkeys. In a tacrolimus study, one of the 4 cynomolgus monkeys that was treated with oral doses of 10 mg/kg/day of tacrolimus for 90 days developed malignant lymphoma.[58] In contrast, none of the 4 monkeys receiving 1 mg/kg/day of oral tacrolimus had evidence of lymphoma or any other biochemical or histopathologic changes.[58] Similarly, in pimecrolimus studies, 1 of 8 animals treated orally with 15 mg/kg/day (31 times the MRHD) for 39 weeks developed lymphoproliferative disease.[38] However, a partial recovery from lymphoproliferative disease was noted upon cessation of pimecrolimus administration.

Responses From the Medical Community

Since the March 2005 PAC meeting, physicians and professional societies, including the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI), and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI), have issued statements supporting the safety of TCIs after careful evaluation of the data.[35,36,53,59,60] In particular, the published report of the AAD Task Force (conducted before the TCI label changes) discussed relevant TCI safety data and the clinical impact of the FDA warnings.[35] The following list summarizes key conclusions and recommendations:[35]

- Negative effects of limiting TCI use

- Increased topical corticosteroid use and potential for increased adverse events

- Failure to treat/undertreatment may lead to recurrent infections and further diminish patient/caregiver quality of life

- Numerous clinical studies of TCIs support their efficacy and safety in children and adults

- Data from randomized clinical trials are at the top of the hierarchy of clinical evidence

Carcinogenicity data from animals, although high-quality, and case reports do not support a causal link between TCI use and malignancy

Follow the label guidelines as closely as possible while weighing the risks and benefits of TCI use for each patient (with these risks being effectively communicated to the patient)

Monitor patients who use TCIs for any adverse events (encourage enrollment in patient registries).

In response to the PAC meetings and Public Health Advisory for TCIs, the AAD Task Force met on July 21, 2005. This meeting was convened to review the data in regard to possible TCI side effects and provide a useful context for physicians and patients. Key points and recommendations of this report are summarized.[35]

Conclusions

AD is a common inflammatory disease that substantially affects patients' lives. To control AD, treatment is frequently multimodal, incorporating several nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches. Although topical corticosteroids have been the mainstay of treatment for AD, TCIs are an additional and valuable treatment option for long-term management. Clinical trials and in-practice experience have demonstrated that TCIs effectively treat AD symptoms and reduce the number of major AD flares. Despite recent concerns about the safety of TCIs, which were raised by the FDA, reports of malignancy in clinical trials and in postmarketing surveillance, along with pharmacokinetic and toxicology studies, have indicated that TCIs have not been causally associated with malignancy or systemic immunosuppression. However, ongoing analysis of TCIs in long-term safety studies, postmarketing surveillance, and patient registries will further establish their safety profile and evaluate any malignancy risk. As a class, TCIs will continue to be an integral part of the treatment armamentarium for patients with AD.

Figure 1.

Typical presentation of atopic dermatitis.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Embryon scientific staff, who assisted in the preparation of a first draft of this article on the basis of an author-approved outline and who also assisted in implementing author revisions. Embryon supports the Good Publications Practice Working Group guidelines on the role of medical writers in developing scientific publications (www.gpp-guidelines.org).

Contributor Information

Mark Lebwohl, Department of Dermatology, The Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY.

Tara Gower, Embryon, Somerville, New Jersey.

References

- 1.Leung DY, Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2003;361:151–160. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kay J, Gawkrodger DJ, Mortimer MJ, Jaron AG. The prevalence of childhood atopic eczema in a general population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:35–39. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen FS, Hanifin JM. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2002;22:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudikoff D, Lebwohl M. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 1998;351:1715–1721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)12082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahuja A, Land K, Barnes CJ. Atopic dermatitis. South Med J. 2003;96:1068–1072. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000097884.29305.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI Evaluator Group. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10:11–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltrani VS, Boguneiwicz M. Atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung DY, Bhan AK, Schneeberger EE, Geha RS. Characterization of the mononuclear cell infiltrate in atopic dermatitis using monoclonal antibodies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983;71:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(83)90546-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanifin JM, Cooper KD, Ho VC, et al. Guidelines of care for atopic dermatitis, developed in accordance with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)/American Academy of Dermatology Association “Administrative Regulations for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines.”. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichenfield LF. Consensus guidelines in diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2004;59(suppl78):86–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals; 2006. Elidel [package insert] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deerfield, Ill: Astellas Pharma US, Inc.; 2006. Protopic [package insert] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breuer K, Werfel T, Kapp A. Safety and efficacy of topical calcineurin inhibitors in the treatment of childhood atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:65–77. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200506020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alomar A, Berth-Jones J, Bos JD, et al. The role of topical calcineurin inhibitors in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(suppl70):3–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grassberger M, Baumruker T, Enz A, et al. A novel anti-inflammatory drug, SDZ ASM 981, for the treatment of skin diseases: in vitro pharmacology. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:264–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hultsch T, Muller KD, Meingassner JG, Grassberger M, Schopf RE, Knop J. Ascomycin macrolactam derivative SDZ ASM 981 inhibits the release of granule-associated mediators and of newly synthesized cytokines in RBL 2H3 mast cells in an immunophilin-dependent manner. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998;290:501–507. doi: 10.1007/s004030050343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Paulis A, Cirillo R, Ciccarelli A, de Crescenzo G, Oriente A, Marone G. Characterization of the anti-inflammatory effect of FK-506 on human mast cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:4278–4285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapp A, Allen BR, Reitamo S. Atopic dermatitis management with tacrolimus ointment (Protopic) J Dermatolog Treat. 2003;14:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanifin JM, Ling MR, Langley R, Breneman D, Rafal E. Tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult patients: part I, efficacy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:S28–S38. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.109810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paller A, Eichenfield LF, Leung DY, Stewart D, Appell M. A 12-week study of tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:S47–S57. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.109813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang S, Lucky AW, Pariser D, Lawrence I, Hanifin JM. Long-term safety and efficacy of tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:S58–S64. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.109812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman MS, Schachner LA, Breneman D, et al. Tacrolimus ointment 0.03% shows efficacy and safety in pediatric and adult patients with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:S177–S185. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boguniewicz M, Fiedler VC, Raimer S, Lawrence ID, Leung DY, Hanifin JM. A randomized, vehicle-controlled trial of tacrolimus ointment for treatment of atopic dermatitis in children. Pediatric Tacrolimus Study Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:637–644. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reitamo S, Rustin M, Ruzicka T, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment compared with that of hydrocortisone butyrate ointment in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:547–555. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reitamo S, Van Leent EJ, Ho V, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment compared with that of hydrocortisone acetate ointment in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:539–546. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eichenfield LF, Lucky AW, Boguniewicz M, et al. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus (ASM 981) cream 1% in the treatment of mild and moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:495–504. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.122187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wahn U, Bos JD, Goodfield M, et al. Efficacy and safety of pimecrolimus cream in the long-term management of atopic dermatitis in children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e2. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meurer M, Folster-Holst R, Wozel G, Weidinger G, Junger M, Brautigam M. Pimecrolimus cream in the long-term management of atopic dermatitis in adults: a six-month study. Dermatology. 2002;205:271–277. doi: 10.1159/000065863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho VC, Gupta A, Kaufmann R, et al. Safety and efficacy of nonsteroid pimecrolimus cream 1% in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in infants. J Pediatr. 2003;142:155–162. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luger T, Van Leent EJ, Graeber M, et al. SDZ ASM 981: an emerging safe and effective treatment for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:788–794. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luger TA, Lahfa M, Folster-Holst R, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of pimecrolimus cream 1% and topical corticosteroids in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:169–178. doi: 10.1080/09546630410033781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soter NA, Fleischer AB, Jr, Webster GF, Monroe E, Lawrence I. Tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult patients: part II, safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:S39–S46. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.109817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reitamo S, Rissanen J, Remitz A, et al. Tacrolimus ointment does not affect collagen synthesis: results of a single-center randomized trial. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:396–398. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Queille-Roussel C, Paul C, Duteil L, et al. The new topical ascomycin derivative SDZ ASM 981 does not induce skin atrophy when applied to normal skin for 4 weeks: a randomized, double-blind controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:507–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Academy of Dermatology Association Task Force. The use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in dermatology: safety concerns. Report of the American Academy of Dermatology Association Task Force. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bieber T, Cork M, Ellis C, et al. Consensus statement on the safety profile of topical calcineurin inhibitors. Dermatology. 2005;211:77–78. doi: 10.1159/000086431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drug Regulatory Affairs. Elidel (pimecrolimus) Cream 1%. NDA 21-302 briefing document. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/05/briefing/2005-4089b2_03_04_Elidel%20Novartis%20Briefing%20Bookredacted.pdf Accessed January 25, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hultsch T, Kapp A, Spergel J. Immunomodulation and safety of topical calcineurin inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 2005;211:174–187. doi: 10.1159/000086739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harper J, Smith C, Rubins A, et al. A multicenter study of the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus ointment after first and repeated application to children with atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reitamo S, Wollenberg A, Schopf E, et al. Safety and efficacy of 1 year of tacrolimus ointment monotherapy in adults with atopic dermatitis. The European Tacrolimus Ointment Study Group. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:999–1006. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.8.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deerfield, Ill: Astellas Pharma US, Inc.; 2006. Prograf [package insert] [Google Scholar]

- 42.US Food and Drug Administration, Pediatric Advisory Committee. Rockville, Md: US Food and Drug Administration; 2006. Discussion Topic: Risk Evaluation, Labeling, Risk Communication, and Dissemination of Information on Potential Cancer Risk Among Pediatric Patients Treated for Atopic Dermatitis With Topical Dermatological Immunosuppressants. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Leent EJ, Graber M, Thurston M, Wagenaar A, Spuls PI, Bos JD. Effectiveness of the ascomycin macrolactam SDZ ASM 981 in the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:805–809. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.7.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thaci D, Steinmeyer K, Ebelin ME, Scott G, Kaufmann R. Occlusive treatment of chronic hand dermatitis with pimecrolimus cream 1% results in low systemic exposure, is well tolerated, safe, and effective. An open study. Dermatology. 2003;207:37–42. doi: 10.1159/000070939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harper J, Green A, Scott G, et al. First experience of topical SDZ ASM 981 in children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:781–787. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allen BR, Lakhanpaul M, Morris A, et al. Systemic exposure, tolerability, and efficacy of pimecrolimus cream 1% in atopic dermatitis patients. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:969–973. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.11.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fleischer AB, Jr, Ling M, Eichenfield L, et al. Tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of atopic dermatitis is not associated with an increase in cutaneous infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:562–570. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.124603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stiehm ER, Roberts RL, Kaplan MS, Corren J, Jaracz E, Rico MJ. Pneumococcal seroconversion after vaccination for children with atopic dermatitis treated with tacrolimus ointment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:S206–S213. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hofman T, Cranswick N, Kuna P, et al. Tacrolimus ointment does not affect the immediate response to vaccination, the generation of immune memory, or humoral and cell-mediated immunity in children. Arch Dis Child. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.094276. 2006 June 23; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Papp KA, Werfel T, Folster-Holst R, et al. Long-term control of atopic dermatitis with pimecrolimus cream 1% in infants and young children: a two-year study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Papp KA, Breuer K, Meurer M, et al. Long-term treatment of atopic dermatitis with pimecrolimus cream 1% in infants does not interfere with the development of protective antibodies after vaccination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaracz E, Maher R, Simon D, Kristy R, Park S, Rico J. Safety profile of tacrolimus ointment: data from five years of post-marketing experience. Program and abstracts of the American Academy of Dermatology 64th Annual Meeting; March 3–7, 2006; San Francisco, California. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fonacier L, Spergel J, Charlesworth EN, et al. Report of the topical calcineurin inhibitor task force of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1249–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tran C, Lubbe J, Sorg O, et al. Topical calcineurin inhibitors decrease the production of UVB-induced thymine dimers from hairless mouse epidermis. Dermatology. 2005;211:341–347. doi: 10.1159/000088505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yarosh DB, Pena AV, Nay SL, Canning MT, Brown DA. Calcineurin inhibitors decrease DNA repair and apoptosis in human keratinocytes following ultraviolet B irradiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:1020–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Niwa Y, Terashima T, Sumi H. Topical application of the immunosuppressant tacrolimus accelerates carcinogenesis in mouse skin. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:960–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Food and Drug Administration. Protopic (tacrolimus) ointment. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Application Number NDA 50777. 2005:1–51. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/nda/2000/50777_protopic.htm Accessed September 27, 2006.

- 58.Wijnen RM, Ericzon BG, Tiebosch AT, Buurman WA, Groth CG, Kootstra G. Toxicology of FK506 in the cynomolgus monkey: a clinical, biochemical, and histopathological study. Transpl Int. 1992;5(suppl1):S454–S458. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77423-2_132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cockerell CJ. American Academy of Dermatology. President's message: Elidel and Protopic alert. March 2005. Available at: http://www.aad.org/aad/PresidentsMessage/ Accessed December 1, 2005.

- 60.Cockerell CJ. President's message: academy disappointed with restrictive new labeling for eczema medication, working to enhance dialogue with FDA. January 23, 2006; Available at: http://www.aad.org/professionals/AdvocacyGovRelSkin/tci_information.htm Accessed June 1, 2006.