Summary

Lengsin is a member of the glutamine synthetase (GS) superfamily expressed in the vertebrate eye lens. While the GS homology domains of lengsin are well conserved in all species examined, the N-terminal domain shows evidence of dynamic evolutionary changes. Compared with zebrafish and chicken, most mammals have an additional exon in the lengsin gene corresponding to part of the N-terminal domain, however in human this is a non-functional pseudoexon. Lengsin belongs to the hitherto purely prokaryotic GS I branch of the GS superfamily. Cryo-EM and modeling studies of lengsin show a dodecamer structure with important similarities and differences with GS I structures. There are sequence changes in GS catalytic motifs of lengsin and in multiple enzyme assays recombinant mouse lengsin showed no activity. Like the taxon-specific crystallins, lengsin may be the result of the recruitment of an ancient enzyme to a different, non-catalytic role in the vertebrate lens. Genomics data show that protein-coding genes related to lengsin are present in the Sea urchin, suggesting that this branch of the GS I family has an ancient role in metazoans.

Introduction

Eyes have arisen independently many times in evolution [1]. In vertebrates and some other groups, a cellular lens is part of the image formation machinery of the eye. Such lenses are relatively recent evolutionary additions to the eye, predated by the photoreceptive retina. Many of the structural proteins of the vertebrate lens, most notably the highly abundant crystallins, arose by gene recruitment of proteins with pre-existing functions in the eye. Such proteins acquired greatly elevated expression in the lens and developed new functional roles [2–7]. In many cases, this multifunctionality has been maintained, so that proteins serving as crystallins in the lens are also expressed elsewhere in eye and in other tissues, often as enzymes or stress proteins. However, there are other examples of lens proteins, particularly of the cytoskeleton [8] and plasma membrane [9, 10], which, although they may have arisen by recruitment from proteins with wider roles in other tissues have, in the course of evolution, become highly specialized for the lens and are now tissue-specific.

Expressed sequence tag (EST) analysis of adult human lens for the NEIBank project for ocular genomics led to the discovery of an abundant, novel transcript in the lens [11–13]. The predicted protein product of this new gene had significant similarity to members of the glutamine synthetase superfamily and was consequently named lengsin, for LEns Glutamine SYNthetase-like [11]. Remarkably, lengsin is most similar to the GlnT (formerly known as class 3) group of the GS superfamily and consequently belongs on the GS I branch of the evolutionary tree that otherwise contains only prokaryotic proteins. Structures of prokaryotic GS I’s have been solved by X-ray crystallography and shown to assemble as dodecamers [14, 15]. Precise structures for eukaryotic GS II enzymes have been harder to determine [16]; however, recently the enzyme from a green bean has been shown by electron microscopy to have a tetramer/octomer assembly [17] whereas the enzyme from maize has been shown by crystallography to be a decamer [18]. A structure for a GS III enzyme has recently been reported and it forms dodecamers [19]

All known GS enzymes are involved in a key metabolic process: the fixation of ammonium and the synthesis of glutamine, an amino acid with a central role in many biosynthetic pathways in the cell. In humans and other species, the lens (like other tissues) expresses the familiar vertebrate (non-dodecameric) GS II enzyme, so the need for a second, tissue-specific enzyme is not obvious. What could the role of a second GS in the lens be? One possibility is that the avascular lens requires a specific mechanism for local detoxification of ammonia and perhaps lengsin could participate in fixing ammonia in a non-toxic form in a tissue that may not have an efficient urea cycle [20]. Lens proteins are also susceptible to posttranslational modification by carbamylation resulting from high levels of cyanate and urea in body fluids [21], so another possibility is that the lens has a specific need for a protective enzyme of nitrogen metabolism modified to handle urea or urea breakdown products. Thirdly, some lens crystallins exhibit specific patterns of deamidation, so there is yet another possibility that lens requires an enzyme with activity against glutamine and asparagine side chains [22, 23].

Alternatively, lengsin may have a non-enzymatic, structural or chaperone-like role in the lens similar to that of different crystallins [4, 24, 25]. Although its abundance at the protein level does not appear to rise to the very high levels achieved by those proteins that have been designated as crystallins (usually at least 1–5% of total lens protein), lengsin is moderately abundant in the whole lens and may have higher localized concentration in differentiating lens fiber cells (unpublished).

Here we show that lengsin exhibits evidence of a dynamic evolutionary history in the vertebrate lens including gain and loss of an exon and major changes in the length of the N-terminal domain. Image reconstruction by single particle image analysis using electron microscopy shows the protein adopts a dodecameric structure that is similar to that of prokaryotic class I GS proteins, but with significant differences. Critical residues for catalytic activity are not conserved in lengsin and recombinant mouse lengsin shows no evidence of enzymatic function. This suggests that the protein may have been re-engineered for a structural or binding role in the lens and may have been recruited to this new role in a way reminiscent of several taxon-specific enzyme crystallins [3].

Results

Lengsin Sequence and Evolution

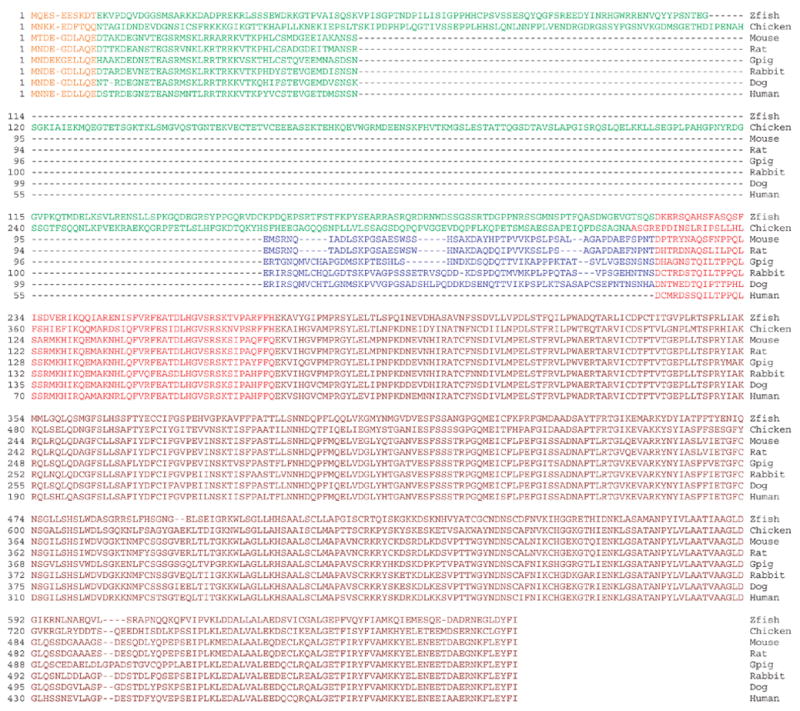

Full length cDNA clones for lengsin from human, mouse, rat, dog, guinea pig, rabbit, chicken and zebrafish were identified from NEIBank lens or whole eye cDNA libraries in expressed sequence tag (EST) analyses [11, 13, 26, 27] and complete sequences were assembled (Fig. 1). While N-terminal regions of the predicted open reading frames (ORF) showed considerable variability in sequence and length, the remainder of the sequence was well conserved across vertebrate evolution.

Figure 1. Lengsin protein sequences.

Aligned predicted amino sequences for vertebrate lengsins (with accession numbers); Zebrafish (zfish) [AAZ29482], Chicken [ABC40398], Mouse [AAN38298], Rat [AAP34385], Guinea pig (Gpig) [ABC59314], Rabbit [DQ885946], Dog [ABD74632], Human [AAF61255]. Sequences are colored to illustrate exon structure for each gene taken from publicly available genome sequences (for rabbit and guinea pig these are inferred from other species).

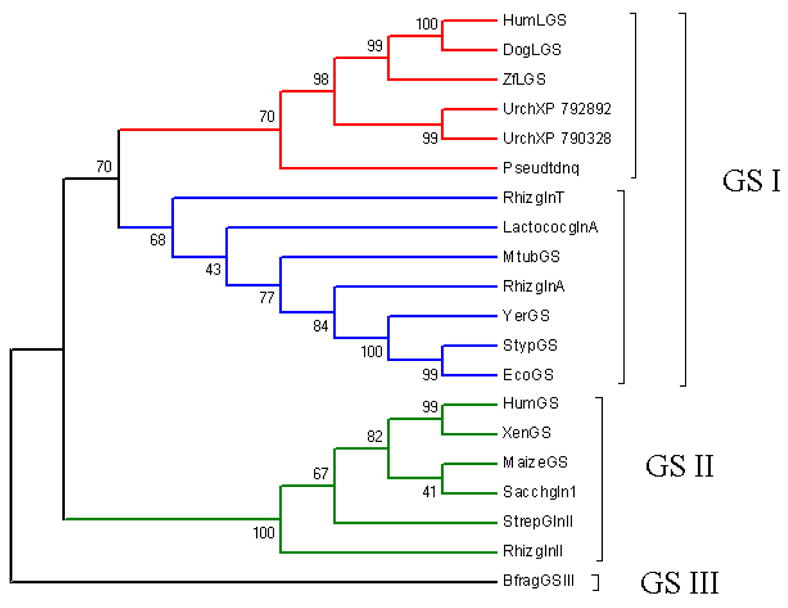

Sequence analysis shows that lengsin belongs to the glutamine synthetase (GS) superfamily [11] (Figs 2 and 3). This superfamily has two major branches, GS I and GS II. A sub-branch of prokaryotic GS proteins from Rhizobium were formerly known as class III but now referred to as GlnT [28] and the term GS III is now used to describe an even more distantly related group pf GS sequences, exemplified by the GS of B. fragilis [29]. All previously known members of the GS superfamily in eukaryotes belong to the GS II class, although the antiquity of the prokaryotic GS I class suggests that GS I could also be represented in eukaryotes [30]. Phylogenetic analysis clearly groups lengsin with the prokaryotic GS I proteins (Fig. 2). As such it is the first non-class II GS to be observed in eukaryotes. Furthermore, recent data from whole genome sequencing projects show that the Sea urchin genome contains multiple genes apparently related to lengsin and the phylogenetic position of two members of this family are shown in Fig.2. This suggests that GS I-like proteins have had a role in eukaryotes and metazoans, although in vertebrates only the lens-specific lengsin is retained.

Figure 2. Lengsin belongs to the prokaryotic branch of the GS superfamily.

Cladistic analysis of GS proteins shows the position of lengsin (LGS) (and related Sea urchin proteins) on the otherwise prokaryotic GS I branch of the superfamily. Sequences were aligned using Clustal W and the tree was drawn using the program MEGA3 with Maximum parsimony, pair-wise comparisons and bootstrapping options.

NCBI accession numbers are as follows. Vertebrate lengsins: human (HumLGS: AAF61255), dog (DogLGS: ABD74632) and zebrafish (Danio rerio) (ZfLGS: AAZ29482); Sea urchin lengsin-like proteins (Urch XP_792892 and Urch XP_790328); eukaryotic GS: human (HumGS: NP_001028216), Xenopus laevis (XenGS: P51121), maize (Zea mays) (MaizeGS: BAA03433), yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (Yeastgln1: P32288); prokaryotic GS: Pseudomonas putida (Pseudotdnq: BAA12805), Rhizobium leguminosarum glnT (RhizglnT: P31592), Lactococcus lactis glnA (LactocosglnA: AAX82489), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MtubGS: P0A590), Rhizobium leguminosarum glnA (RhizglnA: P09826), Yersinia pestis glnA (YerGS: AAS60306), Salmonella typhimurium glnA (StypGS: P0A1P6), Escherichia coli glnA (EcoGS: AAC76867), Streptomyces coelicolor glnII (StrepGlnII: NP_626461), Rhizobium leguminosarum glnII (RhizglnII: Q02154) Bacteroides fragilis glnIII (BfragGSIII: YP_210647).

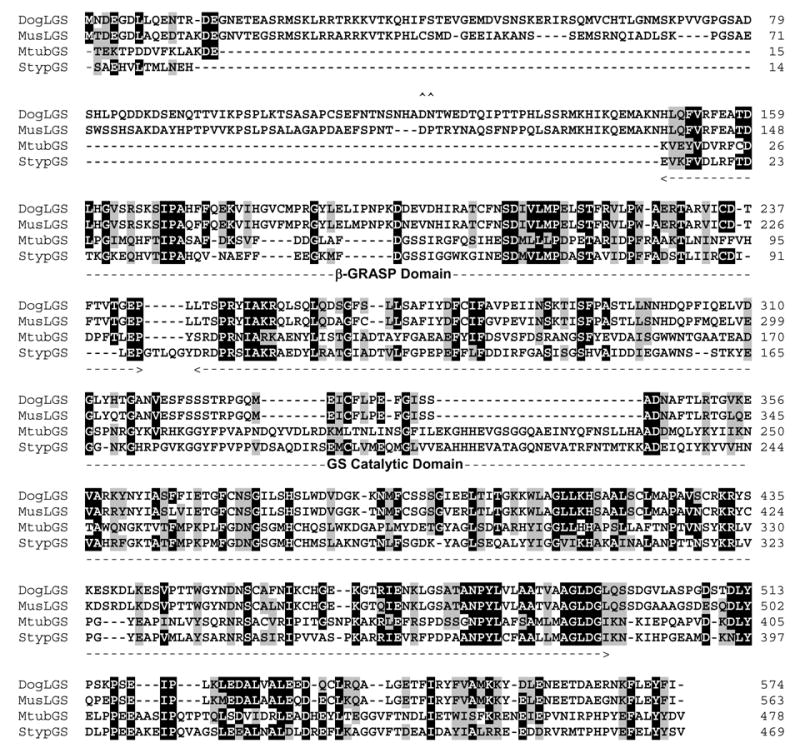

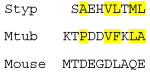

Figure 3. Comparison of lengsin and GS I sequences.

Alignment of two mammalian lengsin protein sequences (dog: ABD74632; mouse: AAN38298) with two GS I enzymes for which x-ray structures are known (Mycobacterium tuberculosis: P0A590, Salmonella typhimurium: P0A1P6). Sequences were aligned using ClustalW (with manual adjustment) in BioEdit. Conserved identical and similar residues are boxed and shaded. Extent of β-GRASP and GS catalytic domains are indicated. Bacterial sequences are numbered without the initiator methionine to correspond with the x-ray structures. the position of the Asp-Pro dipeptide that may be involved in cleavage of the N-terminal domain is indicated by ^^.

All three GS classes contain a homology region that consists of a β-grasp domain (PF03951) and a catalytic domain (PF00120) (Fig. 3, 4). GS Is have an additional sequence extension at the C-terminus, here referred to as the C-terminal domain. The combined β-grasp and GS catalytic domain of mouse lengsin has 25–30% sequence identity with various bacterial GS I sequences. Figure 3 shows the alignment of mouse and dog lengsin with two GS I proteins for which x-ray structures have been determined. In addition to the conserved GS regions, lengsin also has a long N-terminal domain that has no sequence similarity to GS enzymes and is also highly variable among vertebrates (Fig. 1).

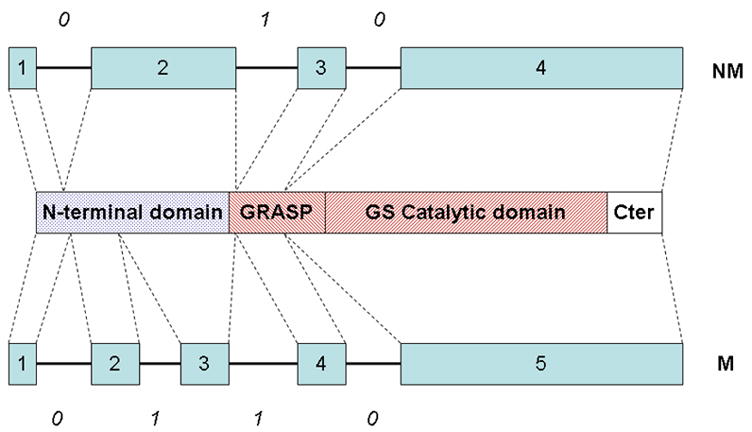

Figure 4. Gene and protein domain structure in lengsins.

Gene structure and domain structure in vertebrate lengsins. Gene structure for mammals (M) and non-mammals (NM) is shown with boxes representing exons and numbers in italics indicating the splicing phase of the introns. The domain structure of lengsin is shown schematically with N-terminal, GRASP, GS catalytic and C-terminal domains. The red striped domains constitute the GS homology region. NM shows the gene structure for lengsin in zebrafish and chicken genomes; M shows the structure for mammalian genes. In primates exon 3 is skipped. For both gene structures, the approximate correspondence of exons and protein domains in lengsin are indicated by dotted lines.

In zebrafish and chicken genomes, the gene for lengsin has four exons (Fig. 4). The first two exons encode the variable N-terminal region. The third corresponds to part of the highly conserved β-grasp domain, while the fourth exon encodes part of the β-grasp domain, the whole GS catalytic domain and the C-terminal domain. In contrast, in the genome of mouse and other mammals, the lengsin gene has five exons. Exons 1, 4 and 5 in mammalian lengsin genes are quite similar to exons 1, 3 and 4 of the non-mammalian genes and have the same splicing phase (Fig. 4). As shown in the schematic, the second exon in mammalian genes generally corresponds to the second exon in zebrafish and chicken, but is considerably shorter. Mammals also have an additional (third) exon that encodes part of the N-terminal domain. However, in spite of having the extra exon, the overall length of the N-terminal domain in mammals is significantly reduced (109 residues in mouse compared with 344 residues in chicken).

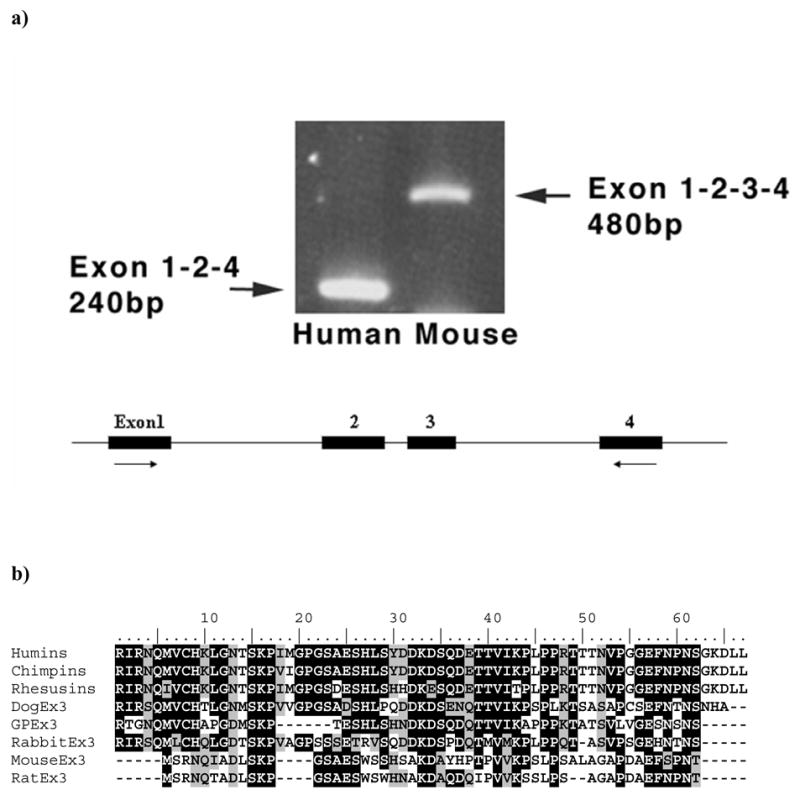

The mammal-specific third exon has a phase 1 splice junction (the intron position occurs after the first base of a codon), which is the same phase as exon 2. This means that exon 3 can be inserted or skipped without breaking the overall ORF of the protein. Indeed, although gene and protein structure is generally similar among mouse, rat, dog and guinea pig lengsin genes, most human lengsin cDNA clones resulting from EST analysis [11] lack sequences corresponding to the mammalian-specific exon 3. Exon skipping was confirmed by comparative PCR of human and mouse cDNA libraries (Fig. 5a) which showed that while exon 3 is quantitatively included in mouse transcripts it is undetected in human. In spite of this the EST analysis of human lens yielded a single alternatively spliced lengsin clone that was found to include sequences with low similarity to mouse exon 3. Subsequently it became clear that this alternative sequence is a much better match for the exon 3 sequences of other species, such as dog (Fig. 5b). When mapped on the human genome, the alternatively spliced sequence was found in intron 2 of the human lengsin gene.

Figure 5. Exon skipping in human lengsin.

a) Top panel shows the results for PCR using templates derived from human lens and mouse whole eye cDNA libraries. Positions of PCR primers relative to mouse gene exon structure are shown schematically. Mouse clones quantitatively include exon 3 which is efficiently skipped in human clones

b) Sequence alignment of exon 3 ORF amino acid sequences from mammalian lengsin genes. Predicted sequences of chimp and rhesus monkey exon 3 ORF are included for comparison, although the splice sites in these species have not yet been experimentally verified.

In the alternatively spliced human cDNA clone the lengsin open reading frame is disrupted by the inclusion of exon 3. While in other non-primate mammals the splice junction at the 3’ end of exon 3 is in phase 1 (following the first base of a codon), the splice site in the human gene is in phase 0, mismatching the frame of the downstream exon 4 acceptor site. Thus, if translated, the variant human transcript would essentially produce an isolated N-terminal domain with no GS-like sequence. It thus appears that exon 3 in humans is a pseudoexon. Examination of the draft chimp and rhesus monkey genomes shows that the exon 3 sequence is well conserved in primates. However it is not yet known whether either of these species skip exon 3. In the rhesus monkey lengsin gene there is a potential splicing lariat site 5’ to exon 3. However, in human and chimp, the critical base is changed from A to G, which would be nonfunctional and would explain loss of splicing in humans. If monkey lengsin transcripts incorporated exon 3, using the same splice sites as in the rare human variant cDNA, the lengsin reading frame would be broken. However, other potential splice sites exist at both ends of the exon and it is possible rhesus uses one of those to maintain frame. The evolutionary history of exon 3 in primates is under further investigation.

Although the exon 3 sequences of primates are well conserved, in spite of the exon being “pseudo” (at least in human), exon 3 sequences are quite variable among mammalian orders (Fig. 4). Thus, while dog lengsin exon 3 encodes a 62 amino acid sequence that is 66% identical to that encoded by the equivalent 67 amino acid human sequence, mouse exon 3 only encodes 53 residues and is only 38% identical to human over that range. Inspection of genome sequences suggests that the evolutionary differences in exon 3 size result from both in-frame slippage of splice sites at both ends of the exon and from deletions. Overall, sequences in the N-terminal region of lengsin appear to have been under dynamic evolutionary modification throughout the history of the vertebrate lens.

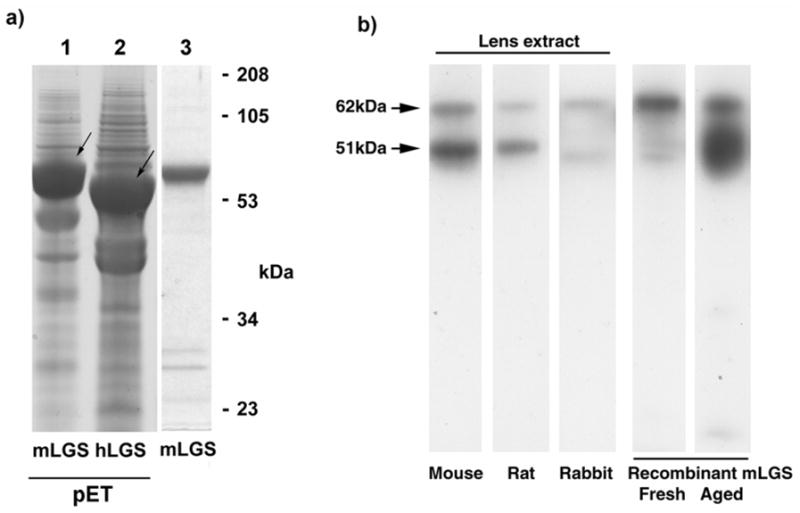

Recombinant Protein

Recombinant mouse and human lengsin were expressed in E.coli (Fig. 6a). The human protein expressed well as a single band of estimated size, 57kDa. However the protein was insoluble and efforts to solubilize have not yet been successful. In contrast, the recombinant mouse protein was soluble and was efficiently purified as a subunit with an estimated size of 62kDa, close to the calculated molecular mass of 62,032 Da. However, upon storage, the mouse protein exhibited a size change, with a 51kDa band appearing. Examination of the mouse sequence showed the presence of an Asp-Pro sequence (see Fig 3), known to be susceptible to non-enzymatic hydrolysis [31], close to the junction between the N-terminal domain and the remainder of the sequence which would lead to a truncated chain of calculated molecular mass of 50,496 Da.

Figure 6. Recombinant protein and western blotting for lengsin.

a) Expression of recombinant human and mouse lengsin in E.coli. First two lanes show SDS PAGE of whole cell extract of cells expressing mouse or human lengsin (arrowed) in the pET system. Third lane shows purified soluble mouse lengsin (from a separate gel).

b) Western blot of mouse, rat and rabbit lens soluble extracts and aged recombinant mouse lengsin shows two bands for lengsin. The upper band corresponds in size to full length lengsin while the lower band corresponds to the size of an N-terminal truncation.

Mass spectroscopic analysis of the 51kDa band located several tryptic peptides from the GS-homology domains, including one from close to the C-terminus, but none from the vertebrate specific N-terminal domain (Table 1). This suggests that the post-translational truncation of lengsin occurs through loss of the N-terminal domain.

Table. Legend:N-terminal truncation of lengsin.

Tryptic peptides identified by size from mass spectroscopic analysis of the post-translationally truncated form of recombinant mouse lengsin. Peptides corresponding to the C-terminus are present suggesting that truncation has occurred at the N-terminus.

| Peptide | Position |

|---|---|

| (K)VIHGVFMPR | 167–175 |

| (R) VLPWAER | 212–218 |

| (R) YNYIASLVIETGFCNSGILSHSIWDVGGK | 350–378 |

| (K) QALGETFIR | 528–536 |

| (K) YELENEETDAEGNKFLETFI | 544–563 |

The purified mouse protein was used to immunize rabbits and to produce a polyclonal antiserum. When used in western blots of mouse, rat and rabbit lens extracts this antibody detected two major bands very similar in size to the 62 and 51kDa species seen in aged samples of the recombinant mouse protein, suggesting that a similar post-translational modification may occur in vivo (Fig. 6b). This antibody does not detect human recombinant lengsin or lengsin bands in human or dog lens (not shown).

Enzymatic studies

Recombinant mouse lengsin was used in several assays for enzyme activity. The protein was tested for GS activity in both forward and back reactions with both glutamine and asparagine and with other possible amide donors, including urea, but no activity was detected. Another possible reaction involving nitrogen transfer is protein deamidation and some crystallins, notably γS-crystallin, are subject to deamidation in the lens [22, 23, 32]. Accordingly, lengsin was incubated with recombinant human γS and γD-crystallins to test for any protein deamidase activity, but no change in crystallin charge was observed.

Cryo-EM Structure analysis

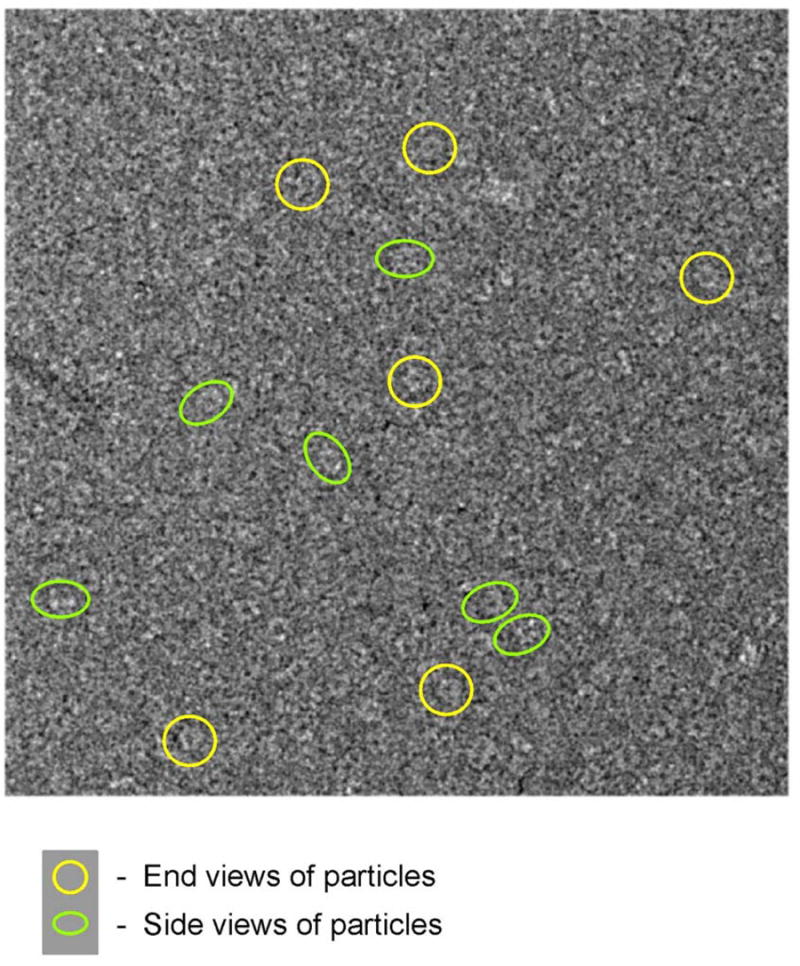

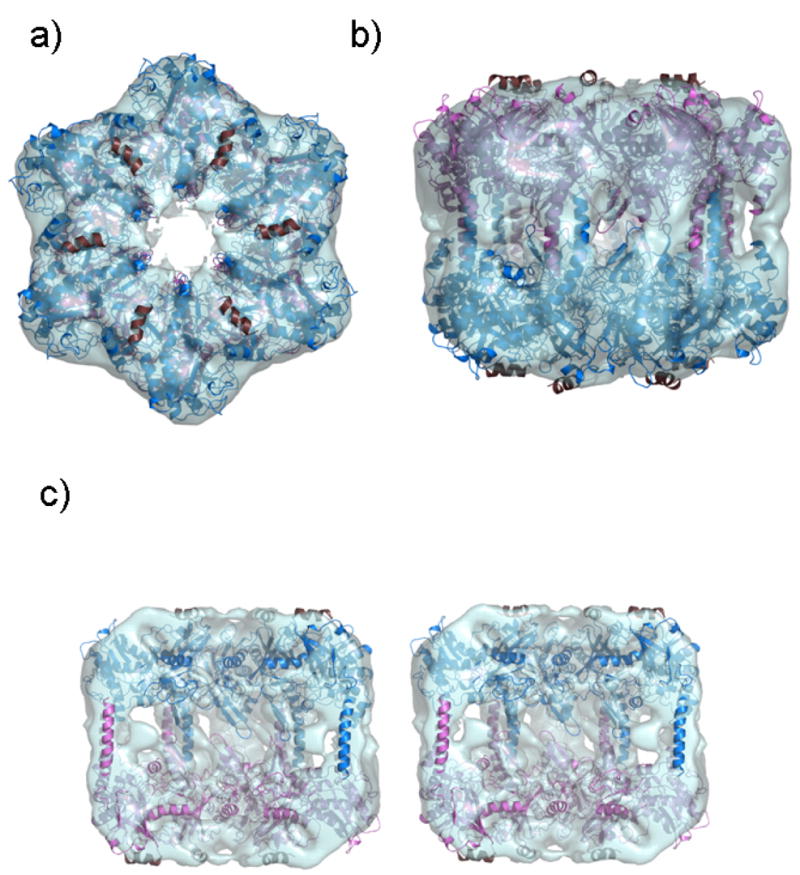

The 3D EM structure was derived from recombinant mouse lengsin containing both 62 and 51kDa species. A cryo-electron micrograph is shown in Figure 7. The symmetry of lengsin was examined by a statistical analysis that revealed clearly 6-fold rotational symmetry for the end views (Supplementary figure S1a). The analysis of side views along with the molecular mass of the assembly indicates that lengsin is a dodecamer with D6 (point group 622) symmetry (Fig. 8, and Supplementary figure S1a). The EM reconstruction (Supplementary figure S1b) shows that mouse lengsin has a similar assembly to the class I prokaryote GS. Lengsin consists of two hexameric rings packed back-to-back with overall dimensions of 140 Ǻ in diameter and ~ 100 Ǻ in height (Fig. 8). The lengsin chain has 563 amino acids with a calculated molecular weight per chain of 62,031 Da giving an oligomer size of 744,372 Da. However, the volume of the molecule is ~620 nm3 at 1σ threshold and can accommodate ~540 kDa of protein mass, assuming a protein density of 0.84 D/Ǻ3, which corresponds more closely to the truncated form of the protein of calculated molecular mass 605,952 Da (based on cleavage at Asp-Pro).

Figure 7. Cryo EM analysis of mouse lengsin.

A cryo-electron micrograph of mouse lengsin with some end views highlighted by yellow circles and side views by green ellipses.

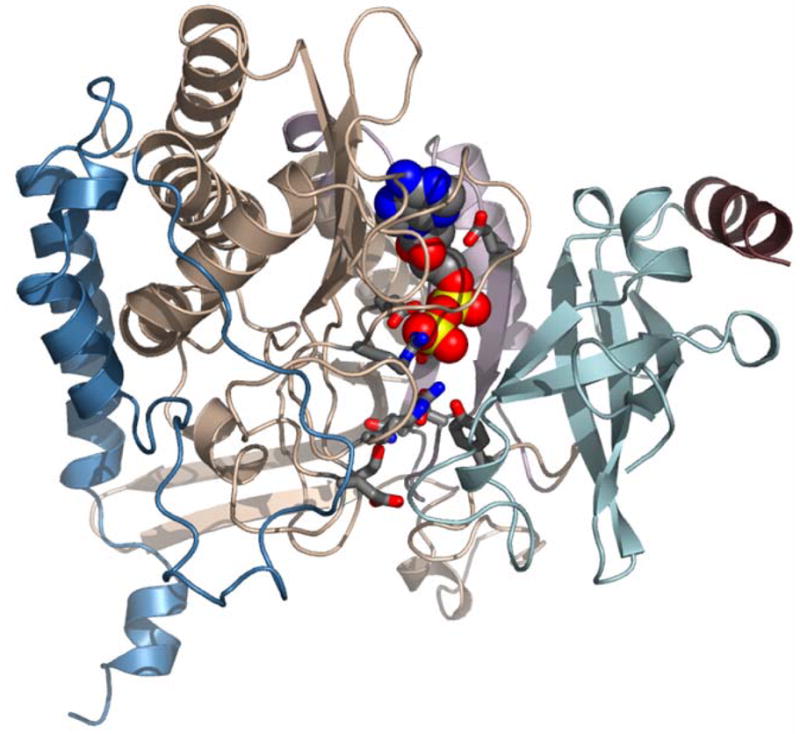

Figure 8. Cryo EM 3D structure and molecular modeling of mouse lengsin.

The mouse lengsin homology model fitted into the lengsin electron density map (transparent cyan) using URO, with the upper hexamer shown as blue ribbon and the lower hexamer in crimson viewed

(a) down the 6-fold rotation axis

(b) from a side view.

In StypGS [1f52] there is a 12 residue N-terminal helical lid patching the β-grasp domain. In MtubGS [2bvc] there are topologically equivalent hydrophobic packing residues in the N-terminal sequence (highlighted below in yellow) that are not conserved in mouse lengsin.

Although there is no sequence evidence for the equivalent helix in mouse lengsin, they are included here in the model, shown in dark brown ribbon, to indicate the likely position of hydrophobic grooves and the location of the N-terminal domains in the complete lengsin structure.

(c) A side view in stereo of the lengsin model in the electron density cut away to show the internal region.

Fitting of bacterial coordinates to the electron density maps

A dodecamer of glutamine synthetase from Salmonella typhimurium (StypGS PDB code: 1F52 [14]) manually fitted to the lengsin cryoEM map gave a reasonable fit when viewed along the 6-fold rotation axis. The position of one monomer was manually adjusted slightly in the density and the dodecamer regenerated. However, when side views and internal areas were inspected gross differences were found. The most obvious difference was two sets of additional density in the form of “pillars” on the outer region of the lengsin dodecamer (Fig. S2a). In addition there was a difference in the region of the β-hairpins (corresponding to residues Asp136-Asp153 of StypGS) that interdigitate between hexameric rings to form the central β-sheet collar of GS I dodecamers. Rigid body refinement in URO, a program that takes into account the experimental density and the fitted atomic structure [33], still left the “pillars density” unfilled.

An approximate homology model of mouse lengsin was built based on the sequence alignment of Fig. 3 (where two mammalian lengsins are aligned with two solved bacterial GS I sequences) using the coordinates of StypGS [1F52] as the initial template. This is a coarse model as the lengsin sequence has major insertions in the GS β-grasp domain and major deletions in the GS catalytic domain. However, the deletions and chain movements were performed with the 1F52 coordinates fitted to the cryo-EM map and thus were built with some constraints.

The region of the lengsin map with the largest discrepancy with the bacterial atomic structure is in the C-terminal domain. Analysis of the sequence alignment (Fig. 3) indicates one obvious region where the chain could change conformation and steer polypeptide chain into a “pillar of density”. This is the loop sequence AGGVFT (residues 430 and 435 in StypGS) between two long helical regions, colored green in Fig. S3. In the structure of StypGS (colored grey in Fig. S3) the region of the C-terminal domain from Phe434 onwards is directed towards the inside of the oligomer. In this loop region sequence in lengsins the two central residues are deleted and therefore in the lengsin homology model (colored maroon in Fig. S3) the shorter loop allowed re-orientation of the helical segment into one of the pillars of density. In StypGS the long terminal helical region is kinked due to prolines at residues 457 and 459 that are not conserved in lengsins. In the mouse lengsin homology model the entire region was built as an un-kinked helix: the long helix from one lengsin chain in one hexameric ring was fitted to one side of a pillar of density and running antiparallel with the corresponding helix from a chain in the other ring. This fitting procedure thus filled six of the outer pillars. In order to fill the other pillar of density the position of the preceding helix in the C-terminal domain was moved in to it. This was justified on the basis that its N-terminal connecting loop (Glu403 to Gly412 colored yellow in StypGS in Fig. S3) was markedly shortened in the lengsins due to deletions indicating the possibility of some re-organization in this region. In sum re-orientation of two helical regions in each C-terminal domain, outside of the GS homology region, allowed the filling of new electron density features in the outer regions of the lengsin dodecamer.

The coordinates for this homology model monomer were energy minimized to improve the stereochemistry in the regions where deletions had been made. The minimized model was fitted onto the un-minimized one using LSQKAB [34] and the fit to the density was checked visually. A dodecamer of mouse lengsin was then generated using D2 symmetry and two minimized monomers from this dodecamer are shown in Fig. S2b. The position of the dodecamer in the electron density was refined using URO [33] which resulted in the two rings being pushed further apart. The correlation coefficient for the fit of the StypGS [1F52] structure to the cryoEM map was 43.4% while that for the lengsin homology model after refinement was 51.7%.

The refined cryoEM structure of lengsin reveals a dodecamer that resembles a bacterial GS I assembly when viewed down the six-fold rotation axis (Fig. 8a). However, a side view shows that disposition of the GS I-specific C-terminal domain with respect to the GS homology region is different (Fig. 8b). Furthermore, the inner collar that binds the two rings together in the bacterial GS Is appears to have been disrupted (Fig. 8c and Fig. S2c). These structural differences have an impact on the hexamer-hexamer interaction in that the stabilization of the lengsin dodecamer appears to have shifted from the centre of the rings to the perimeter.

Comparison of the GS homology regions of bacterial and vertebrate GS I proteins

In the bacterial GS Is each of the 12 active site binding pockets lies between the β-grasp domain of one subunit and the catalytic domain of an adjacent subunit within a ring (Fig. 9), formed from an interaction between an edge β-strand of the β-grasp domain extending the curved β-sheet in the catalytic domain that cradles the bound nucleotide. As lengsins have major sequence differences in the GS homology region from the bacterial GS Is, this region of the lengsin homology model is coarse. Here we indicate in broad terms the likely impact of the sequence changes with reference to the ADP-bound coordinates of Styp, PDB code 1F52, and Mtub, PDB code 2BVC [15].

Figure 9. The interface active site of bacterial GS.

The atomic model of StypGS [1f52] showing that the interface between polypeptide chains adjacent within a hexameric ring (A and F depicted) form the active site binding pocket, shown here with bound ADP in cpk spacefill. The N-arm, residues 1–12 (maroon) and β-grasp domain residues 13-100 (powderblue) are from molecule A and the catalytic domain residues 101-184 and 232-383 (peachpuff) and the GSI specific C-terminal domain (steelblue) are from molecule F. The region colored thistle (pale mauve) in the catalytic domain has major deletions in lengsins. The side chains (in ball and stick, cpk colours) appended to the catalytic domain (Tyr179, Glu212, Glu207, Glu220, Gln218, Glu129, Asn264, Glu327, Arg339, Arg344, Arg359) are conserved in active GSI enzymes (where they line the binding pocket for nucleotide, substrate and metal ions) but are mutated in mouse lengsin.

The extensive active site pocket of a GS I binds nucleotide, glutamate and ammonium ion with structural contributions from the GS catalytic domain and the β-grasp domain. In lengsin there are major deletions in the sequence in the catalytic domain resulting in the deletion of key binding residues: Glu212 (219), Glu207 (214), Glu220 (227), Gln218 (225). In regions of the GS catalytic domain where the bacterial and vertebrate sequences are more conserved, lengsin retains Glu357 (366) and Arg321 (329) but there are point mutations to other key binding residues: Glu129 (133), Tyr179 (186), Asn264 (271), Glu327 (335), Arg339 (347), Arg344 (352), Arg359 (368) are replaced in lengsin by Ile, Ser, Ser, Lys, Asn, Asn and Lys respectively. These extensive sequence changes of the lengsin GS catalytic domain make it unlikely that the protein assembly has retained its catalytic function and are consistent with the absence of detectable activity in the recombinant protein.

In GS Is the β-grasp barrel fold is highly distorted from the prototype ubiquitin fold, presumably to make space for the active site pocket. In StypGS the N-terminal helix (colored brown in Fig. 9) lies across the top of the barrel patching the fold with a strip of hydrophobic residues: Ala2, Val5, Leu6, Met8, Leu9. The long axes of the β-grasp barrels lie parallel to the dodecamer six-fold, with the “lid” helices perpendicular to it lying flat on the large surface area like spokes in a wheel. In lengsin, the N-terminal sequence does not have this hydrophobic repeat and is unlikely to form a helix with the equivalent packing function.

Exon 5 of the mouse lengsin gene encodes the equivalent of the C-terminal domain, the entire GS catalytic domain, as well as the β-grasp domain, except for the first two β-strands, which are encoded by the 3’half of exon 4 (Fig. 9). In GS I structures, the second β-strand of the β-grasp domain H-bonds across the interface to the catalytic domain. Its partner strand is in the region of the catalytic site where lengsin has major deletions. In mouse lengsin the N-terminal sequence of 9(10) residues is precisely encoded in exon 1. This sequence does not have the pattern of hydrophobic residues required for completion of the β-grasp fold and there is no obvious equivalent packing motif in the first half of exon 4. The lengsin sequences may patch their β-grasp barrels with their longer N-terminal domain encoded in exons 2 and 3. Overall, it appears that the evolutionary changes in the vertebrate lengsin gene are associated with structural change to a complex region of the bacterial machine. However, truncation at the N-terminal region, removing protein sequence equivalent to exon 1, exon 2 and possibly the entire exon 3, may leave the flat surfaces of the dodecamer with exposed hydrophobic patches (Fig. 8).

Discussion

The major soluble proteins of the lens are the crystallins. Different classes of crystallins were derived by recruitment of various proteins with pre-existing functions at different stages in evolution [3, 4, 6]. The α-crystallins are small heat shock proteins [24, 35, 36]: α B-crystallin is abundant in lens but has heat shock functions in other tissues while gene duplication has produced the more eye-specific αA-crystallin. (Indeed, in zebrafish a second gene duplication has produced αB1 and αB2-crystallins in which additional specialization for expression and function is apparent [37].) The related β- and γ-crystallins have evolved and specialized from an ancestor thought to have a role in maintenance or control of cell structure [5, 27, 38]. Other crystallins have arisen more recently in vertebrate evolution and are restricted to specific lineages. Most of these taxon-specific crystallins are enzymes that maintain dual roles, although in the case of δ-crystallin/argininosuccinate lyase in birds and reptiles, gene duplication and specialization has also occurred [3, 39].

While not achieving crystallin-like levels of expression (which can range from a few percent to over 50% of soluble protein for individual proteins), lengsin is expressed abundantly in adult lens in all vertebrate species examined [13, 26, 27] and appears to be highly specific for differentiating lens fiber cells (in preparation). Lengsin is reminiscent of the taxon specific enzyme crystallins in that it is related to enzymes and presumably derived from an ancestor with catalytic function.

Lengsin is a member of the GS superfamily, a very widespread family now recognized to have three major branches, GS I, GS II and the more distantly related GS III [11, 28–30]. Sequence comparisons and cladistic analysis show that vertebrate lengsins belong to the GS I branch of the family. This is a remarkable observation since, hitherto, the only GS proteins observed in eukaryotes have been restricted to the GS II branch [30]. Very recently it has become apparent that other metazoans may also express GS I type proteins since the genome sequencing project for the Sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) has revealed as many as 17 predicted lengsin-like genes.

The similarity of lengsin to GS I enzymes is underscored by cryoEM structure analysis that shows a dodecamer structure generally similar to those determined for bacterial GS enzymes [40–42]. However, the experimentally derived 3D EM map of lengsin differed from the other GS Is, most strikingly in the presence of new features in the outer regions of the lengsin dodecamer that could be filled by reorganization of helices in the C-terminal domain. The C-terminal domain in the dodecameric GS I proteins thus appears to perform the role of stabilizing hexamer-hexamer interactions in a variety of ways.

The EM structure analysis of recombinant mouse lengsin is consistent with a subunit size that corresponds to an N-terminally truncated version of the protein, a post-translational modification that is observed both in vivo and also in vitro. Molecular modeling of lengsin, based on X-ray structures of bacterial GS I enzymes is consistent with this interpretation. The predicted structure shows a number of features similar to the active GS I enzymes and overall, the lengsin model fits the general conformation of the bacterial GS I structures. Differences in loop lengths and in local sequence require some reorientation of structural elements, such as in two C-terminal helical regions. However, there are also major differences in detailed structure, particularly around the catalytic center where deletions and changes in key catalytic or binding residues make it unlikely that lengsin retains the same catalytic activity as the bacterial enzymes.

While all known members of the GS superfamily are enzymes, the need for a tissue specific GS enzyme is not obvious, although we have considered several possibilities including a specific mechanism of nitrogen fixation or urea detoxification and even a role as a protein deamidase. A wide range of potential activities covering these and other possibilities were tested using recombinant mouse lengsin. However, consistent with the significant changes in important catalytic residues in the lengsin sequence, no activity of any kind was observed.

These observations suggest that rather than an enzymatic role in the lens, lengsin may instead be serving a structural role. This is believed to be true for the enzyme crystallins, whose abundance in lens exceeds any plausible metabolic role while in at least in the case of birds, δ1-crystallin enzyme activity has been lost after gene duplication and separation of functions [3, 39]. Since many enzymes are known to associate with cytoskeleton [43], one possibility under investigation is that lengsin could have a role in stabilization of structural elements of the highly specialized lens fiber cell. This might resemble the chaperone-like functions of the α-crystallins [24, 35, 36].

Although lengsin is conserved in all vertebrate species examined so far, from fish to birds and mammals, it also shows evidence of the same kind of dynamic evolutionary change that characterizes other aspects of the molecular composition of the vertebrate eye lens [3]. Zebrafish and chicken genes have four exons, presumably representing the ancestral structure. Although the mapping of domains and exons is not exact, the first two exons essentially correspond to the large N-terminal domain, the last two to the GS homology regions. The N-terminal domain is the location of most of the variation in lengsin sequence among vertebrates. This is reflected in the specific changes seen in mammals. It appears that in the ancestors of mammals, the second exon became truncated and a third, in phase exon was acquired. Even so, the N-terminal domain is significantly shortened in mammals compared with fish and bird. In the primate lineage this trend is exacerbated by loss of the mammal-specific exon 3 through exon skipping: although the ORF of the exon is well conserved, a frame shift at the 3’ end of the exon puts it out of frame with the GS homology domains. This is the second example of quantitative exon skipping and the consequent creation of a pseudoexon in a major human lens protein, the first being αA-crystallin [44]. Just as in lengsin, the skipped exon in αA-crystallin is an evolutionary innovation specific to the mammal lineage which has been abandoned in primates (and in the case of αA-crystallin, also in some non-primates [45]). Thus it seems that in the molecular evolution of the primate/human lens more than one ancestral mammal-specific adaptation has been reversed.

Furthermore, even in mammals (such as mice) that retain splicing of exon 3, evidence suggests that the N-terminal domain may be removed by post-translational modification. Western blots reveal two major lengsin size species in lens extracts of rodents and rabbit. Similar bands appear in blots of recombinant lengsin upon storage. Since the size difference corresponds to loss of the N-terminal domain, and since at least one tryptic peptide close to the C-terminus of the protein was detected by mass spectroscopy, it seems likely that the truncation involves cleavage of a peptide connecting the N-terminal domain to the C-terminal GS homology domains. Indeed, the cryoEM structure and molecular modeling of lengsin are consistent with the loss of the N-terminal domain leaving the flat surfaces of the dodecamer with exposed hydrophobic patches (Fig. 8) that could be involved in protein-protein interactions in the lens. Truncation of the N-terminal region, at the gene or protein level, may reflect a regulatory mechanism controlling lengsin function in the lens.

So the N-terminal domain is highly variable through vertebrate and mammalian evolution and may also be subject to post-translational loss. Poor conservation in evolution could mean that the structure is not subject to preservation through selection for an important function. However, it is also possible that the N-terminal domain is under strong diversifying selection to adapt the function of lengsin to the different requirements of the lens in different lineages.

The eye, perhaps more than most organs, is subject to great adaptive pressures from environment and habit. In the lens, protein content and concentration vary greatly as needs for accommodation, close focus, day/night, air/water vision have changed through vertebrate evolution [3]. In addition, the packing of lens fiber cells has also changed significantly among vertebrate species [46]. While a basic core structure of the lengsin GS homology domains is well conserved, other interactions or regulation of function may be under the control of the N-terminal domain and this has been subject to many episodes of modification and re-engineering during evolution.

Finally, the similarity of lengsin (and now also of the uncharacterized Sea urchin proteins) to bacterial forms of GS is remarkable since no protein of this class had been seen before in eukaryotes. While this could represent the lateral transfer of a GS I into an ancestor of metazoans from a non-eukaryotic source, the antiquity of the GS I class means it is quite possible that GS I enzymes were widely expressed in the ancestors of vertebrates and other metazoans [30]. Over time, GS I enzymes may have been eliminated from vertebrate genomes, supplanted by GS II, but not before one protein was saved through acquisition of a different, specialized role in the evolving eye lens.

Experimental Procedures

cDNA Analysis

Human, mouse and zebrafish cDNA libraries were produced as described previously [11, 26, 27]. Dog, rabbit and guinea pig lens libraries were made and analyzed following the same protocols and will be described in detail elsewhere. Sequence data are available through the NEIBank web site (http://neibank.nei.nih.gov).

Bioinformatics

Sequences were assembled using GRIST [47] and examined further using SeqMan (DNAstar, Madison WI) and BLAT [48] alignment onto genome sequences [http://genome.ucsc.edu/ and http://eyebrowse.cit.nih.gov]. Cladistic analysis was performed using MEGA3 [49]. Conserved domains were defined using Blastp (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and multiple sequence alignments for figures were performed using ClustalW in BioEdit [50]with manual adjustment to align defined domains.

PCR methods

To examine incorporation of exon 3 sequences in human and mouse lengsin clones, template was produced by plasmid prep of aliquots of cDNA libraries from human lens and mouse whole eye [11, 27] representing at least 500,000 clones using reagents from QIAGEN (Valencia, CA). PCR primers were designed for equivalent regions of human and mouse lengsin. Specific primer for human exon 1: ATGAATAATGAAGAGGACCTTCTGCAG; mouse exon 1: ATGACCGACGAAGGGGACCTCGCACAG; common primer for exon 4: TCTGTTGCTTCAAATCGTACAAACTGG. Fragments were amplified using Taq polymerase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN).

Recombinant proteins

The coding sequence (cds) of mouse lengsin was amplified from cDNA using specific primers incorporating Nde I and Hind III restriction sites: MLGS5b: AACATATGACCGACGAAGGGGACCTCGC; MLGS3: CTCGAGCTATATAAAATACTCCAGGAATTTATTTCC. Human lengsin cds was cloned using Nhe I and Bam HI primers: LGS5: GCTAGCATGAATAATGAAGAGGACCTT CTG; LGS3: GGATCCTAAATAAAATACTCTAAGAATTTATTTC. Products were cloned into pCRII (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA), sequenced and subcloned into pET 17b (Novagen) for expression in E. coli BL21, codon plus, ril. Clones were picked into LB/Amp medium and were induced using lactose (final 2g/L) and grown overnight at 25°C. Cells were lysed in buffer containing MnCl2. Whole cell lysate was dialyzed against 25 mM malonic acid pH 6.0/1 mM DTT and separated using an SP-fast flow, 26/60, cationic exchange column on an AKTA Explorer 100 (GE Biosciences). Samples were eluted using a 0.3-1M NaCl gradient in 25 mM malonic acid pH 6.0/1 mM DTT.

Recombinant proteins were verified by mass spectroscopy. Bands from SDS PAGE were excised, destained and digested with trypsin (Sigma, St. Louis MO). Peptides were extracted in trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 5%, dried, reconstituted in 0.1% TFA and applied to C18 ZipTip columns (Millipore, Bedford MA). The eluted fraction was mixed with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic matrix in elution buffer, 10mg/ml and spotted. Data acquisition was performed on a Voyager DE-STR MALDI-TOF MS (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA) in the positive reflector mode. 100 spectra were collected and averaged. External calibration was performed using apo-myoglobin tryptic digest. Peak mass lists were searched using Mascot (Matrix Science, UK).

Antibody

Recombinant mouse lengsin was used to immunize rabbits (Spring Valley, Woodbine, MD). Sera were purified using protein A columns (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Mouse, rat and rabbit lenses were homogenized in TE buffer and soluble and insoluble fractions separated by micro-centrifugation. 10μg samples were separated by SDS PAGE (Novex) and tested by western blot.

Enzyme activity

Recombinant mouse lengsin was tested in several GS and related assays. Multiple GS assays were used in both the forward and backward reactions [28, 51, 52] and urea was tested as a possible nitrogen donor in a modified version of the GS assay [52] using 25 μg purified lengsin and 10–25 mM urea (substituted for hydroxylamine hydrochloride). Asparagine synthetase activity was also tested [53].

Lengsin was assayed for possible crystallin deamidation activity [23] by incubation with recombinant human γS- and γD-crystallin. 25 μg of lengsin was mixed with 10–25 μg of each γcrystallin in 6 mM HEPES, pH 7, with either ATP or ADP 5 mM in a final volume of 25 μl. The samples were incubated at 37°C overnight. Samples were separated by isoelectric focusing (pH 3-10) (Invitrogen) and examined for charge variants.

Electron microscopy

A 100 μl sample of recombinant mouse lengsin protein, at a concentration of ~0.3 mg/ml, was spun in a Vivascience Vivaspin 500, 5K MWCO, at 12000 g for 25 mins at 4°C and the volume reduced to 8 μl. Concentrated protein was diluted x 5 with 25 mM malonic acid, pH 6. Samples (5μl) of purified lengsin were applied to carbon-coated copper grids (400 mesh, freshly glow-discharged in air). After 2 min excess buffer was removed by blotting and specimens were stained twice with 5 μl 2% uranyl acetate for 1 min. Micrographs were recorded using a FEI Tecnai T10 transmission electron microscope with magnification of 44,000×. For cryo images samples were vitrified on holey carbon grids and data collected on an FEI 200kV FEG microscope at 50,000x magnification. Images were taken at low dose mode. A range of defocus settings (1.7–3.2 μm) was used to record data on Kodak SO163 film. Negatives were developed in Kodak full strength developer D-19 for 12 min and their quality was assessed by optical diffraction.

Image analysis

Initial images were analyzed from negatively stained samples. Seven micrographs were digitized on a Zeiss SCAi scanner at sampling of 1.59 Å/pixel. Cryo images were scanned with a step of 1.4 Å/pixel. All images were corrected for contrast transfer function by phase flipping. Around 4000 images were selected manually. Image analysis was performed using IMAGIC-5 [54]. Data sets were normalized to the same standard deviation and band-pass filtered: the low-resolution cut-off was ~100 Å to remove uneven background in particle images. Images were centered using rotationally averaged total sum of images. Images corresponding to the end views (along the rotational axis of symmetry) were extracted into a separate data set and analyzed for their symmetry using statistical analysis. This analysis revealed clear 6-fold symmetry. Taking into account the molecular weight of a dodecamer, in the following analysis we have used symmetry D6.

The model obtained from the negatively stained sample was used as a starting model to process lengsin images in ice. Seven negatives were analyzed from which ~ 3,000 images were selected. After centering and alignment, images were subjected to statistical analysis and classification. For the first 3D analysis 12 classes were used. The first model was reprojected and used as reference to improve alignment and classification. Angular orientation of classes was determined using angular reconstitution [55]. The final reconstruction was calculated out of 150 classes containing 8–15 images each. 3D maps were calculated using the exact-filter back projection algorithm [56, 57]. Resolution of the map was assessed using the 0.5 threshold of Fourier Shell Correlation [58, 59] which corresponds to17 Å.

Modeling and refinement

A homology model of mouse lengsin was built using the coordinates of StypGS [1F52] as the initial template. Manual rebuilding was performed to restore the polypeptide connections. Side chains were replaced using COOT [60] in areas of secondary structure whereas in other regions side chains were replaced with alanines. The coordinates for this homology model monomer were energy minimized after missing side chain atoms and hydrogens were added using the TLEAP program. Simulations were undertaken using the AMBER 8 [61] version of SANDER, using GBSA representation of solvent and using an 18A° non-bonded cut-off, an internal dielectric of 1.0 and an external dielectric of 78.5. Energy minimization of the protonated structure was undertaken to an rmsd of 0.01A°, for 5000 steps.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Andrew Purkiss for help with running Amber, Dave Houldershaw and Richard Westlake (Birkbeck) and James Gao and Patee Buchoff (NEI) for excellent computer support. OAB and CS gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Medical Research Council, London. Work at NEI was carried out under intramural project EY000433.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Keith Wyatt, Section on Molecular Structure and Functional Genomics, National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892-0703 USA.

Helen E. White, Department of Crystallography, Institute of Structural Molecular Biology, Birkbeck College, University of London, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HX, UK

Luchun Wang, Department of Crystallography, Institute of Structural Molecular Biology, Birkbeck College, University of London, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HX, UK.

Orval A. Bateman, Department of Crystallography, Institute of Structural Molecular Biology, Birkbeck College, University of London, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HX, UK

Christine Slingsby, Department of Crystallography, Institute of Structural Molecular Biology, Birkbeck College, University of London, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HX, UK.

Elena V. Orlova, Department of Crystallography, Institute of Structural Molecular Biology, Birkbeck College, University of London, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HX, UK

Graeme Wistow, Section on Molecular Structure and Functional Genomics, National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892-0703 USA.

References

- 1.Land MF, Fernald RD. The evolution of eyes. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1992;15:1–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wistow GJ, Mulders JW, de Jong WW. The enzyme lactate dehydrogenase as a structural protein in avian and crocodilian lenses. Nature. 1987;326:622–624. doi: 10.1038/326622a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wistow G. Lens crystallins: gene recruitment and evolutionary dynamism. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:301–306. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90041-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wistow G. Molecular Biology and Evolution of Crystallins: Gene Recruitment and Multifunctional Proteins in the Eye Lens. Austin, TX: R.G. Landes Company; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimeld SM, Purkiss AG, Dirks RP, Bateman OA, Slingsby C, Lubsen NH. Urochordate betagamma-crystallin and the evolutionary origin of the vertebrate eye lens. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1684–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wistow GJ, Piatigorsky J. Lens crystallins: the evolution and expression of proteins for a highly specialized tissue. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:479–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.002403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piatigorsky J, Wistow G. The recruitment of crystallins: new functions precede gene duplication. Science. 1991;252:1078–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinlan RA, Sandilands A, Procter JE, Prescott AR, Hutcheson AM, Dahm R, Gribbon C, Wallace P, Carter JM. The eye lens cytoskeleton. Eye . 1999;13(Pt 3b):409–416. doi: 10.1038/eye.1999.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chepelinsky AB. The ocular lens fiber membrane specific protein MIP/Aquaporin 0. J Exp Zoolog Part A Comp Exp Biol. 2003;300:41–46. doi: 10.1002/jez.a.10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou L, Chen T, Church RL. Temporal expression of three mouse lens fiber cell membrane protein genes during early development. Mol Vis. 2002;8:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wistow G, Bernstein SL, Wyatt MK, Behal A, Touchman JW, Bouffard G, Smith D, Peterson K. Expressed sequence tag analysis of adult human lens for the NEIBank Project: over 2000 non-redundant transcripts, novel genes and splice variants. Mol Vis. 2002;8:171–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wistow G. A project for ocular bioinformatics: NEIBank. Mol Vis. 2002;8:161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wistow G. The NEIBank project for ocular genomics: data-mining gene expression in human and rodent eye tissues. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2006;25:43–77. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill HS, Eisenberg D. The crystal structure of phosphinothricin in the active site of glutamine synthetase illuminates the mechanism of enzymatic inhibition. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1903–1912. doi: 10.1021/bi002438h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krajewski WW, Jones TA, Mowbray SL. Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase in complex with a transition-state mimic provides functional insights. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10499–10504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502248102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenberg D, Gill HS, Pfluegl GM, Rotstein SH. Structure-function relationships of glutamine synthetases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:122–145. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llorca O, Betti M, Gonzalez JM, Valencia A, Marquez AJ, Valpuesta JM. The three-dimensional structure of an eukaryotic glutamine synthetase: Functional implications of its oligomeric structure. J Struct Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unno H, Uchida T, Sugawara H, Kurisu G, Sugiyama T, Yamaya T, Sakakibara H, Hase T, Kusunoki M. Atomic structure of plant glutamine synthetase: A key enzyme for plant productivity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29287–29296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Rooyen JM, Abratt VR, Sewell BT. Three-dimensional Structure of a Type III Glutamine Synthetase by Single-particle Reconstruction. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:796–810. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jernigan HM., Jr Urea formation in rat, bovine and human lens. Experimental Eye Research. 1983;37:551–558. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(83)90131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harding JJ, Dilley KJ. Structural proteins of the mammalian lens: A review with emphasis on changes in development, aging and cataract. Experimental Eye Research. 1976;22:1–73. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(76)90033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takemoto L, Boyle D. Increased deamidation of asparagine during human senile cataractogenesis. Mol Vis. 2000;6:164–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takemoto L. Deamidation of Asn-143 of gamma S crystallin from protein aggregates of the human lens. Curr Eye Res. 2001;22:148–153. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.22.2.148.5524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horwitz J. Alpha-crystallin. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00278-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bloemendal H, De Jong W, Jaenicke R, Lubsen NH, Slingsby C, Tardieu A. Ageing and vision: structure, stability and function of lens crystallins. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004;86:407–485. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vihtelic TS, Fadool JM, Gao J, Thornton KA, Hyde DR, Wistow G. Expressed sequence tag analysis of zebrafish eye tissues for NEIBank. Mol Vis. 2005;11:1083–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wistow G, Wyatt K, David L, Gao C, Bateman O, Bernstein S, Tomarev S, Segovia L, Slingsby C, Vihtelic T. gammaN-crystallin and the evolution of the betagamma-crystallin superfamily in vertebrates. FEBS J. 2005;272:2276–2291. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shatters RG, Liu Y, Kahn ML. Isolation and characterization of a novel glutamine synthetase from Rhizobium meliloti. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:469–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodman HJ, Woods DR. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens gene encoding a type III glutamine synthetase. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1487–1493. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-7-1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumada Y, Benson DR, Hillemann D, Hosted TJ, Rochefort DA, Thompson CJ, Wohlleben W, Tateno Y. Evolution of the glutamine synthetase gene, one of the oldest existing and functioning genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3009–3013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piszkiewicz D, Landon M, Smith EL. Anomalous cleavage of aspartylproline peptide bonds during amino acid sequence determinations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970;40:1173–1178. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90918-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lampi KJ, Ma Z, Hanson SR, Azuma M, Shih M, Shearer TR, Smith DL, Smith JB, David LL. Age-related changes in human lens crystallins identified by two-dimensional electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Exp Eye Res. 1998;67:31–43. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navaza J, Lepault J, Rey FA, Alvarez-Rua C, Borge J. On the fitting of model electron densities into EM reconstructions: a reciprocal-space formulation. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1820–1825. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902013707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bailey S. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quinlan R. Cytoskeletal competence requires protein chaperones. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2002;28:219–233. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56348-5_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Jong WW, Caspers GJ, Leunissen JA. Genealogy of the alpha-crystallin--small heat-shock protein superfamily. Int J Biol Macromol. 1998;22:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(98)00013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith AA, Wyatt K, Vacha J, Vihtelic TS, Zigler JS, Jr, Wistow GJ, Posner M. Gene duplication and separation of functions in alphaB-crystallin from zebrafish (Danio rerio) Febs J. 2006;273:481–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ray ME, Wistow G, Su YA, Meltzer PS, Trent JM. AIM1, a novel non-lens member of the betagamma-crystallin superfamily, is associated with the control of tumorigenicity in human malignant melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3229–3234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piatigorsky J, O'Brien WE, Norman BL, Kalumuck K, Wistow GJ, Borras T, Nickerson JM, Wawrousek EF. Gene sharing by delta-crystallin and argininosuccinate lyase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:3479–3483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gill HS, Pfluegl GM, Eisenberg D. Multicopy crystallographic refinement of a relaxed glutamine synthetase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis highlights flexible loops in the enzymatic mechanism and its regulation. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9863–9872. doi: 10.1021/bi020254s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liaw SH, Eisenberg D. Structural model for the reaction mechanism of glutamine synthetase, based on five crystal structures of enzyme-substrate complexes. Biochemistry. 1994;33:675–681. doi: 10.1021/bi00169a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamashita MM, Almassy RJ, Janson CA, Cascio D, Eisenberg D. Refined atomic model of glutamine synthetase at 3.5 A resolution. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17681–17690. doi: 10.2210/pdb2gls/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knull HR, Walsh JL. Association of glycolytic enzymes with the cytoskeleton. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1992;33:15–30. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-152833-1.50007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jaworski CJ, Piatigorsky J. A pseudo-exon in the functional human àA-crystallin gene. Nature. 1989;337:752–754. doi: 10.1038/337752a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Dijk MA, Sweers MA, de Jong WW. The evolution of an alternatively spliced exon in the alphaA-crystallin gene. J Mol Evol. 2001;52:510–515. doi: 10.1007/s002390010181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuszak JR, Zoltoski RK, Sivertson C. Fibre cell organization in crystalline lenses. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:673–687. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wistow G, Bernstein SL, Touchman JW, Bouffard G, Wyatt MK, Peterson K, Behal A, Gao J, Buchoff P, Smith D. Grouping and identification of sequence tags (GRIST): bioinformatics tools for the NEIBank database. Mol Vis. 2002;8:164–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kent WJ. BLAT--the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software for microcomputers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Y, Kahn ML. ADP-ribosylation of Rhizobium meliloti glutamine synthetase III in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1624–1628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kingdon HS, Hubbard JS, Stadtman ER. Regulation of glutamine synthetase. XI. The nature and implications of a lag phase in the Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase reaction. Biochemistry. 1968;7:2136–2142. doi: 10.1021/bi00846a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reitzer LJ, Magasanik B. Asparagine synthetases of Klebsiella aerogenes: properties and regulation of synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:1299–1313. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.3.1299-1313.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Heel M, Harauz G, Orlova EV, Schmidt R, Schatz M. A new generation of the IMAGIC image processing system. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:17–24. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Heel M. Angular reconstitution: a posteriori assignment of projection directions for 3D reconstruction. Ultramicroscopy. 1987;21:111–123. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(87)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Radermacher M. Three-dimensional reconstruction of single particles from random and nonrandom tilt series. J Electron Microsc Tech. 1988;9:359–394. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1060090405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harauz G, van Heel M. Exact Filters for General Geometry 3-Dimensional Reconstruction. Optik. 1986;73:146–156. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saxton WO, Baumeister W. Principles of organization in S layers. J Mol Biol. 1986;187:251–253. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Heel M, Harauz G. Resolution Criteria for 3-Dimensional Reconstruction. Optik. 1986;73:119–122. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Case DA, Cheatham TE, 3rd, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Jr, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.