Abstract

MEPE and DMP1 may play a role in mineralisation and demineralisation within the osteocyte microenvironment. Our earlier studies showed that DMP1 is mechanically responsive [Gluhak-Heinrich J, Ye L, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ, MacDougall M, Harris SE, et al. Mechanical loading stimulates dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) in osteocytes in vivo. J Bone Min Res 2003;18(5):807–17].

Objectives

To examine the effect of mechanical loading on the expression of MEPE using mouse tooth movement model, and compare this effect to that on DMP1.

Methods

In situ hybridisation and immunohistochemistry was performed on 38 treated and 38 control bone sites loaded 6–72 h. ImageJ was used for quantification of mRNA expression in osteocytes.

Results

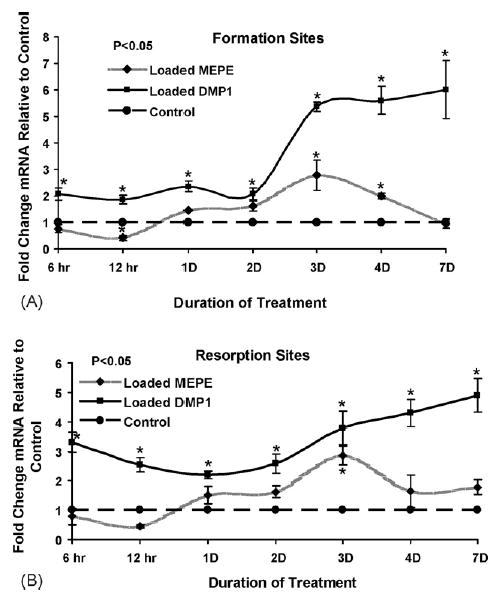

Alveolar osteocytes showed high basal level of MEPE that decreased during the first day of loading, followed by 2.8-fold stimulation at day 3, and returning to a control level by day 7.

Conclusion

The osteocyte specific mechanical stimulation of MEPE was delayed and different, compared to that of DMP1. This suggests a distinct role of MEPE and DMP1 in the response of osteocytes to mechanical loading in vivo.

Keywords: MEPE, Mechanical loading, Osteocytes, Tooth movement

1. Introduction

Osteocytes are mechanically responsive cells which send biochemical signals to other osteocytes within the osteocyte syncytium and to cells on the bone surface.2 These signals may be secreted into the bone fluid bathing the dendritic processes within the canaliculi, or may be transmitted from cell to cell through gap junctions.3–7 Osteocyte signalling induced by mechanical loading is poorly understood.

Matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE) regulator of bone mineralisation in comparison to the other related proteins such as DMP1 suggests an important role in response of osteocytes to mechanical loading modifying mineralisation within the osteocyte microenvironment. MEPE, also referred to as OF 45, was isolated and cloned from a TIO tumour cDNA library.8 The other rat and mouse homologous genes were independently isolated based on the ability of MEPE to regulate mineralisation.9 MEPE belongs to the same SIBLING family10 as dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1), which is mechanically responsive in the tooth movement model.1 Both MEPE and DMP1 are highly expressed in osteocytes compared to osteoblasts.11 These genes produce proteins that may directly modulate mineralisation within the osteocyte canalicular and lacunar walls, as suggested in the MEPE and DMP1 knockout models.12,13 Our earlier in vivo studies showed that expression of MEPE and DMP1 are regulated by mechanical loading using a mouse ulna model.14

In the present study, we examined effect of mechanical loading on temporal and spatial expression of MEPE mRNA and distribution of MEPE protein before and after loading using this mouse tooth movement model. Levels of MEPE mRNA expression before and after loading was compared and correlated to DMP1 expression during a 7-day time course of mechanical loading.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mechanical loading of alveolar bone and preparation of histological sections

2.1.1. Mechanical loading

Mechanical loading of alveolar bone, the calibration of appliance, and biomechanical characterisation of the model were conducted as described previously.15 Briefly, the mice were anaesthetised before insertion of the orthodontic appliance. The appliance consisted of a coil spring bonded directly to the incisors and maxillary first molar. A force (10–12 g) was applied continuously from 6 h to 7 days. Mechanically loaded and control alveolar bone sites adjacent to the palatal and disto-buccal roots of the molars were obtained for analysis. Manipulation and treatment of animals were performed according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee.

2.1.2. Tissue preparation

Mouse maxillae were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. After demineralisation (15% EDTA and 0.5% paraformaldehyde) for 6 weeks, samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 6–8 μm thickness.

2.2. In situ hybridisation and mRNA level quantification

2.2.1. Preparation of probes

RNA antisense and sense probes for MEPE were prepared from a 1.4 kb mouse MEPE HindIII and EcoRI linearised Bluescript subclone and transcribed with T3 and T7 polymerase, respectively.8 DMP1 mouse antisense and sense RNA probes were prepared from a 623 bp mouse DMP1 XhoI and NotI linearised pCR-Script subclone and transcribed with T3 and T7 polymerase, respectively.16 RNA probes were transcribed in vitro in the presence of 32P-rUTP. All RNA probes were hydrolysed in 40 mM NaHCO3/60 mM Na2CO3, pH 10.2, for desired time at 60 °C. The probes were an average size of 200–300 nucleotides. Sizes of the RNA probes were confirmed by electrophoresis on 5% poly-acrylamide gels containing 15 M urea.

2.2.2. In situ hybridisation

The in situ hybridisation was performed using a modification of the procedure described in.1 Briefly, after deparaffinisation sections were treated with proteinase K. Hybridisation was performed at 55 °C overnight with 32P rUTP labelled MEPE and DMP1 RNA probes. After hybridisation, sections were incubated with RNase (40 mg/ml RNase A1 and 10 U/ml RNase T1) in buffer solution (0.3 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA) at 37 °C for 30 min. Consecutive 5 min washes at 57 °C were done with 2× SSC, 0.5× SSC, and 0.1× SSC. For autoradiography, slides were dipped in photographic emulsion (Kodak NTB 3) and exposed for 3 weeks.

2.2.3. Quantification of hybridisation signal in osteocytes

Intensity of hybridisation signal in osteocytes was measured using the ImageJ software. Osteocytes embedded in bone or osteoid within 200 μm of alveolar bone adjacent to the coronal 2/3 of the molar root were quantified.17 The intensity of hybridisation signal in osteocytes expressing MEPE and DMP1 mRNA was determined in selected areas in both mesial (resorption) and distal (formation) sites, by analysing intensity of silver grains on darkfield images. The intensity was normalised with average of three independent background values on the same slide. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of differences in hybridisation signal in osteocytes from loaded and control alveolar bone.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry of MEPE protein

Immunohistochemistry with polyclonal rabbit antibodies against MEPE, LF-155,18 was performed on sequential sections used for in situ hybridisation. After deparaffinisation and rehydration, retrieval of MEPE was performed with Vector demasking solution according to manufactures instructions. An Alkaline phosphatase (AP) kit for immunohistochemistry obtained from Vector laboratories was used to detect MEPE expression. Sections were then blocked in PBS containing 10% goat serum at room temperature for 1 h. The rabbit anti mouse-MEPE polyclonal antibody was added on sections at a dilution of 1:400 in PBS containing 1% BSA and 10% goat serum overnight at 4 °C. After washing the sections, AP anti-goat antibody (Vector) was added at a dilution of 1:200 and the sections were incubated at room temperature for 60 min. The sections were washed again and incubated with the ABC reagent (Vector) at room temperature for 30 min. Fast Red alkaline phosphatase substrate solution was used to visualise immunoreaction sites. The sections were mounted with 70% glycerol in PBS. Negative control was obtained by substituting the primary antibody with non-immune rabbit IgG (Fig. 4a and f). The secondary anti-goat antibody did not cross react with the primary antibody derived from rabbit.

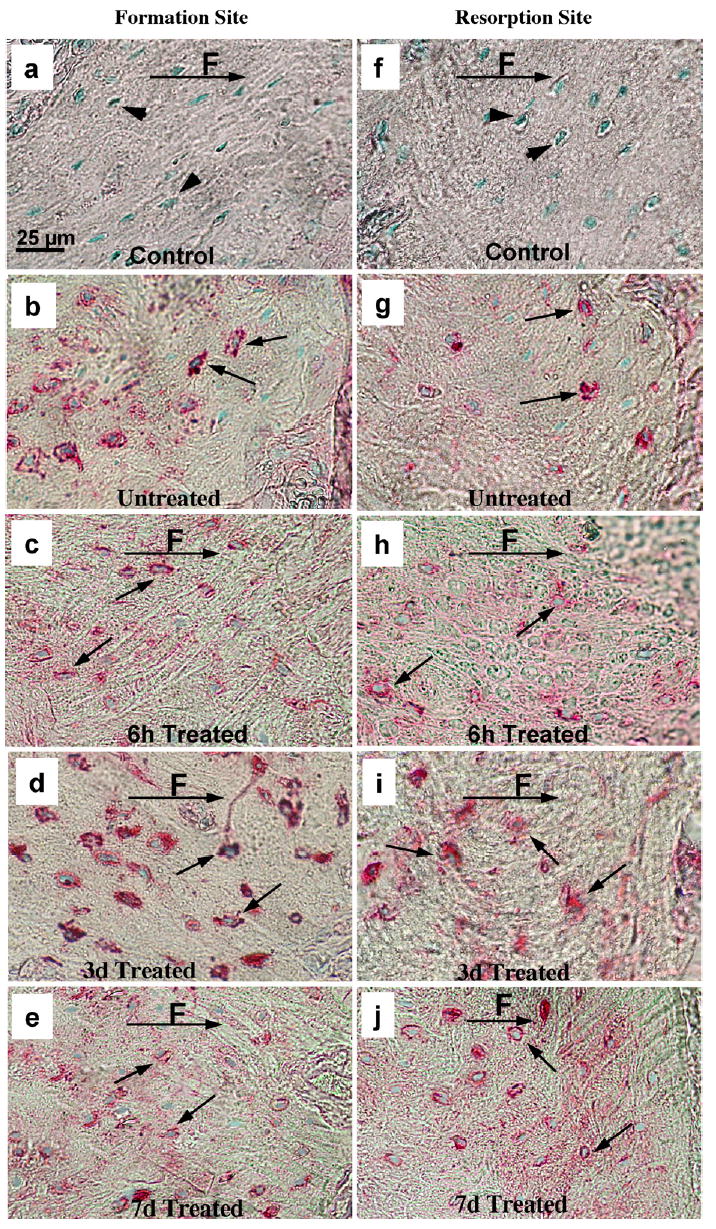

Fig. 4.

Immunocytochemistry of MEPE in periodontal osteocytes. The formation (a, b, c, d, e) and resorption (f, g, h, i, j) periodontal sites: 6 h (c, h), 3 days (d, i) and 7 days (e, j) after loading. The untreated, alveolar bone corresponding to formation and resorption sites is shown in (b) and (g). The black arrows indicate immunoreactivity in the lacunae of osteocytes, and the arrowheads indicate lack of immunostaining in control treated sections (a, f) where primary anti MEPE antibody was replaced with non-immune rabbit IgG. Note significant increase in MEPE staining after 3 days of treatment (d, i) and decrease, 6 h (c, h) and 7 days (e, j) after treatment. F, direction of applied force.

3. Results

3.1. MEPE mRNA expression

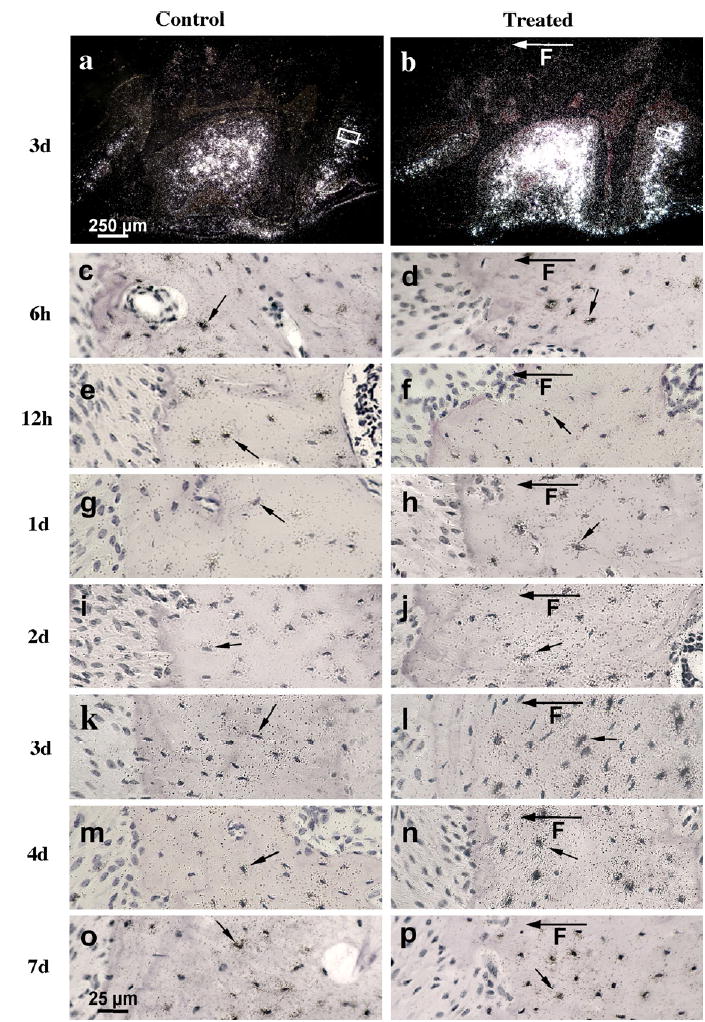

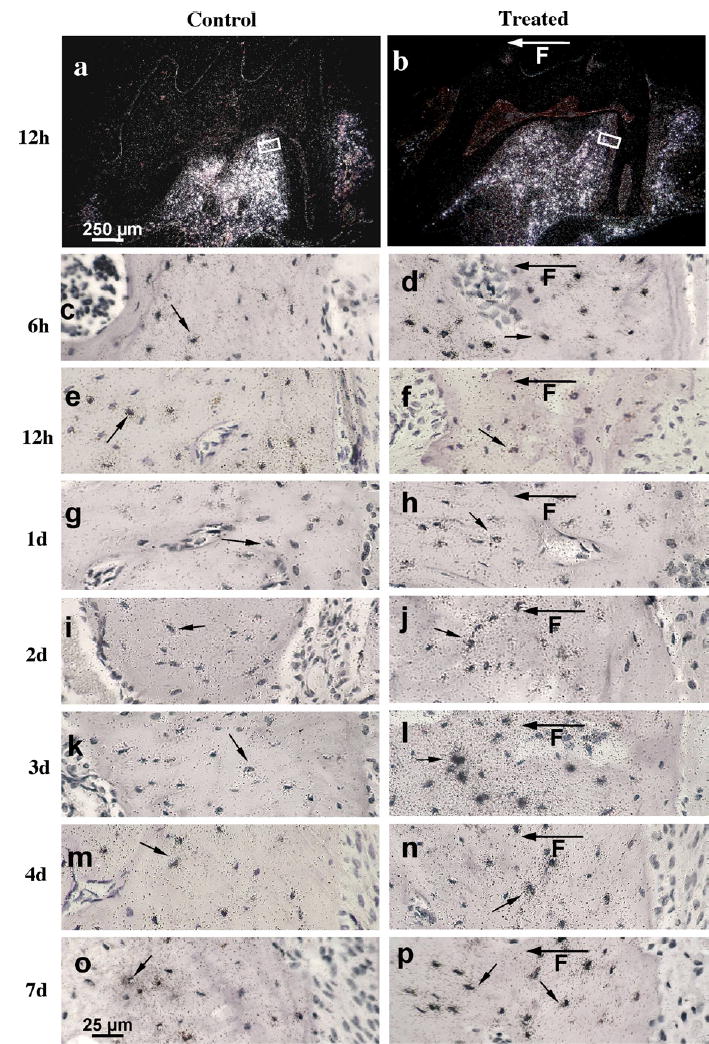

Compared to the controls (contra-lateral side without an appliance), MEPE mRNA expression in osteocytes significantly decreased during the first day of mechanical loading in both bone formation and resorption sites (Figs. 1c–f; 2a–f; 3). In contrast, our earlier results1 showed that DMP1 mRNA increased 2–3-fold in osteocytes during the first day of loading. However, by 3 days MEPE levels significantly increased 2.8-fold in the osteocytes on both the bone formation sites and the resorption sites (Figs. 1a, b, k, and l; 2k and l; 3A and B). At day 3 there was increased MEPE immunoreactivity as shown in Fig. 4b, d, g, and i. At 4 and 7 days following the onset of treatment, mechanically induced stimulation of MEPE expression was greatly reduced from the 3-day level in resorption sites and reached the control level at day 7 in formation sites (Figs. 1m–p; 2m–p; 3A and B). DMP1 mRNA levels, on the other hand, remained elevated five-fold above control levels during the entire time course up to 7 days (Fig. 3A and B).

Fig. 1.

In situ hybridisation of MEPE in representative sections of 10-week-old mice maxillary first molars after 6 h to 7 days of loading. Dark-field autoradiographs represent control (a) and 3 days loaded (b) alveolar bone with first molar. The boxed areas in (a) and (b) represent positions and origins of higher magnification light-field figures showing 3 days control (k) and loaded (l) bone formation distal sites of alveolar bone tissue, respectively. The rest of control and loaded light-field autoradiographs of in situ hybridisation were taken at similar positions and represent distal control (c, e, g, i, k, m, o) and corresponding distal loaded (d, f, h, j, l, n, p) bone formation sites. The hybridisation signal was maximal 3 days after loading (b and l) compared to the control (a and k) in the bone formation sites. Note decrease of hybridisation signal 6 and 12 h after treatment in loaded bone formation site (d, f) compared to 6 and 12 h control bone site (c, e). The black arrows indicate expression of MEPE mRNA in the osteocytes and F with arrow is showing direction of applied force.

Fig. 2.

In situ hybridisation of MEPE in representative sections of 10-week-old mice maxillary first molars after 6 h to 7 days of loading. Dark-field autoradiographs represent control (a) and 12 h loaded (b) alveolar bone with first molar. The boxed areas in (a) and (b) represent positions and origins of higher magnification light-field figures showing 12 h control (e) and loaded (f) bone resorption mesial sites of alveolar bone tissue, respectively. The rest of light-field autoradiographs of in situ hybridisation were taken at similar positions and represent mesial control (c, e, g, i, k, m, o) and corresponding mesial loaded (d, f, h, j, l, n, p) bone resorption sites. The hybridisation was maximal 3 days after loading (l) compared to the control (k). Note decrease of hybridisation signal 12 h after treatment in loaded bone resorption site (b, f) compared to 12 h control bone site (a, e). The black arrows indicate expression of MEPE mRNA in the osteocytes and F with arrow is showing direction of applied force.

Fig. 3.

Effect of mechanical loading on the intensity of MEPE and DMP1 mRNA in periodontal osteocytes. The bone formation (A) and bone resorption (B) sites, total of 19 mice (ages of 9 and 11 weeks): Thirty-eight palatal and disto-buccal roots of the molar were obtained for analysis. The effect of loading is shown as the ratio of control and loaded intensity of MEPE and DMP1 mRNA expression in formation sites. Note the reciprocal response to loading during first day of treatment. Similar response of DMP1 and MEPE expression was found between 1 and 3 days of loading. Reciprocal courses of mRNAs expressions continue after 3 days of treatment.

The expression of MEPE mRNA was not detected in alveolar osteoblasts either before or after loading.

All the results listed above were obtained using antisense MEPE and DMP1 RNA probes; however the hybridisation signal obtained with sense MEPE and DMP1 probes was on the level of the background.

3.2. Localisation of MEPE protein

The MEPE protein in controls (contra-lateral side without an appliance) was detected in osteocytes as shown in Fig. 4b and g. MEPE protein expression in osteocytes followed a similar expression pattern as MEPE mRNA on both the bone formation and bone resorption sites. MEPE protein distribution was decreased as early as 6 h after mechanical loading (Fig. 4c and h). After 3 days of treatment, MEPE protein levels increased in matrix embedded osteocytes (Fig. 4d and i) similar to the RNA expression. MEPE immunoreactivity subsequently decreased at 7 days to the control level (Fig. 4e and j). At all time points, MEPE protein immunoreactivity was only seen in osteocytes. Thus the MEPE gene and its response to mechanical load is an excellent system to study osteocyte function as related to mechanical stimulation.

4. Discussion

MEPE is a member of acid phosphoproteins, that is expressed in teeth and bone.19,20 Recent reports show that MEPE mRNA is highly and selectively expressed in mineralised matrix embedded osteocytes and MEPE protein is localised along dendritic processes.10,21,22 Mechanical regulation of MEPE suggests a role in osteocyte response to mechanical loading. Another hypothetical role of MEPE could be mineralisation and mineral removal within the canalicular wall and within the osteocyte lacunae, since MEPE knockout mice have been shown to have accelerated mineralisation.12 It is known that cathepsin D or B can cleave MEPE, releasing the C-terminal ASARM region, a potent inhibitor of mineralisation in vitro.23,24 In contrast, fragments of MEPE containing RGD integrin binding sites have been shown to paradoxically stimulate mineralisation.25 These findings suggest that MEPE might have dual functions that depend on its proteolitic processing. This could have a dramatic effect on pressure and fluid dynamics within the canaliculi that, in turn, would modify how osteocytes receive and respond to further mechanical stimulation.

In the present study, we were comparing intensity of MEPE and DMP1 mRNA hybridisation signal in osteocytes using mouse tooth movement model. The data of DMP1 expression in the same model published earlier1 showed percent of osteocytes expressing DMP1 mRNA before and after loading rather than hybridisation signal intensity.

The present findings demonstrated significant changes of MEPE mRNA in osteocytes associated with externally applied mechanical loading of bone using tooth movement model. As early as 6 h after orthodontic treatment, there is a decrease in the level of MEPE mRNA expression and MEPE protein distribution in alveolar osteocytes within the regions stimulated to form and to resorb bone (Figs. 1 and 2). Similarly, we recently determined a decrease of MEPE mRNA in the proximal part of ulnae 1 day after mechanical loading using mouse ulna model.14 In the mouse tooth loading model, early bone matrix deposition (on bone formation sites) and the appearance of TRAP positive cells (on bone resorption sites) appear on the alveolar bone surface adjacent to periodontium 2 and 3 days after treatment.15,26 During this 3-day period of active bone formation and resorption, MEPE expression is not seen in the osteoblasts. These findings are supported with an recent study of human bone, where the highest and predominant MEPE expression was detected in bone matrix embedded osteocytes. Little MEPE expression was detected in the osteocytes within the osteoid, and no MEPE expression was detected in osteoblasts.22

After the initial decrease in MEPE expression during first day of loading, MEPE mRNA and protein levels were increased almost three-fold in bone embedded osteocytes. There is an extensive mineralisation period in the tooth movement model from days 4 to 7.15 MEPE mRNA and protein expression decreased to control levels by day 7, while DMP1 expression remained elevated five-fold compared to the controls. These results suggest that MEPE and DMP1 play different roles in mineralisation within the osteocyte lacunae and surrounding bone. These finding are consistent with studies showing significant bone mass increase and mineralisation of bone in MEPE knockout mice12 and low mineralised bone in DMP1 knockout mice.13

Significant changes of MEPE mRNA in osteocytes during early orthodontic treatment in the mouse tooth movement model, and earlier results from the mouse ulna model,14 support the hypothesis that MEPE has an important role in the response of osteocytes to mechanical loading of bone in vivo. MEPE protein can be processed to a C-terminal ASRAM peptide with potent demineralisation properties. MEPE N-terminal region, on the other hand, can signal through integrin pathway and play positive anti-apoptotic roles on osteocytes. In conclusion, these results suggest that during early (day 1) and late (days 4–7) mechanical loading, mechanical regulation of MEPE expression is different then that of DMP1. These results also suggest that MEPE and DMP1 gene products may have coordinated but distinct roles during mechanically induced bone remodelling, depending on the level of processing of these two mechanically responsive SIBLING proteins.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Health research grant NIDCR R03 DE16949 and AR46798. We thank Dr. Larry Fisher for allowing us to use their MEPE antibody in these studies.

References

- 1.Gluhak-Heinrich J, Ye L, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ, MacDougall M, Harris SE, et al. Mechanical loading stimulates dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) in osteocytes in vivo. J Bone Min Res. 2003;18(5):807–17. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.5.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noble BS, Reeve J. Osteocyte function, osteocyte death and bone fracture resistance. Mol Cell Endo. 2000;159(1–2):7–13. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng B, Zhao S, Luo J, Sprague E, Bonewald LF, Jiang JX. Expression of functional gap junctions and regulation by fluid flow in osteocyte-like MLO-Y4 cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(2):249–59. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palumbo C, Palazzini S, Zaffe D, Marotti G. Osteocyte differentiation in the tibia of newborn rabbit: an ultrastructural study of the formation of cytoplasmic processes. Acta Anatomica. 1990;137(4):350–8. doi: 10.1159/000146907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palumbo C, Palazzini S, Marotti G. Morphological study of intercellular junctions during osteocyte differentiation. Bone. 1990;11(6):401–6. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(90)90134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowin SC. On mechanosensation in bone under microgravity. Bone. 1998;22(5 Suppl):119S–25S. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doty SB. Morphological evidence of gap junctions between bone cells. Calcif Tissue Int. 1981;33(5):509–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02409482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowe PS, de Zoysa PA, Dong R, Wang HR, White KE, Econs MJ, et al. MEPE, a new gene expressed in bone marrow and tumors causing osteomalacia. Genomics. 2000;67(1):54–68. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen DN, Tkalcevic GT, Mansolf AL, Rivera-Gonzalez R, Brown TA. Identification of osteoblast/osteocyte factor 45 (OF45), a bone-specific cDNA encoding an RGD-containing protein that is highly expressed in osteoblasts and osteocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(46):36172–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher LW, Fedarko NS. Six genes expressed in bones and teeth encode the current members of the SIBLING family of proteins. Conn Tissue Res. 2003;44(Suppl 1):33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Igarashi M, Kamiya N, Ito K, Takagi M. In situ localization and in vitro expression of osteoblast/osteocyte factor 45 mRNA during bone cell differentiation. Hist J. 2002;34(5):255–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1021745614872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gowen LC, Petersen DN, Mansolf AL, Qi H, Stock JL, Tkalcevic GT, et al. Targeted disruption of the osteoblast/ osteocyte factor 45 gene (OF45) results in increased bone formation and bone mass. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(3):1998–2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye L, MacDougall M, Zhang S, Xie Y, Zhang J, Li Z, et al. Deletion of dentin matrix protein-1 leads to a partial failure of maturation of predentin into dentin, hypomineralization, and expanded cavities of pulp and root canal during postnatal tooth development. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(18):19141–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gluhak-Heinrich J, Yang W, Harris MA, Bonewald LF, Robling AG, Turner CH, et al. Mechanically induced DMP1 and MEPE expression in osteocytes: correlation in mechanical strain osteogenic response and gene expression threshold. J Bone Min Res. 2005;20(Suppl 1):S24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavlin D, Gluhak-Heinrich J. Effect of mechanical loading on periodontal cells. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2001;12(5):414–24. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacDougall M, Gu TT, Luan X, Simmons D, Chen J. Identification of a novel isoform of mouse dentin matrix protein 1: spatial expression in mineralized tissues. J Bone Min Res. 1998;13(3):422–31. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavlin D, Magness M, Zadro R, Goldman ES, Gluhak-Heinrich J. Orthodontically stressed periodontium of transgenic mouse as a model for studying mechanically induced gene regulation in bone: the effect on the number of osteoblasts. Clin Orthod Res. 2000;3(2):55–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW. Expression of SIBLINGs and their partner MMPs in salivary glands. J Dent Res. 2004;83(9):664–70. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowe PS, Kumagai Y, Gutierrez G, Garrett IR, Blacher R, Rosen D, et al. MEPE has the properties of an osteoblastic phosphatonin and minhibin. Bone. 2004;34(2):303–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDougall M, Simmons D, Gu TT, Dong J. MEPE/OF45, a new dentin/bone matrix protein and candidate gene for dentin diseases mapping to chromosome 4q21. Conn Tissue Res. 2002;43(23):320–30. doi: 10.1080/03008200290000556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Argiro L, Desbarats M, Glorieux FH, Ecarot B. Mepe, the gene encoding a tumor-secreted protein in oncogenic hypophosphatemic osteomalacia, is expressed in bone. Genomics. 2001;74(3):342–51. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nampei A, Hashimoto J, Hayashida K, Tsuboi H, Shi K, Tsuji I, et al. Matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE) is highly expressed in osteocytes in human bone. J Bone Min Met. 2004;22(3):176–84. doi: 10.1007/s00774-003-0468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowe PS, Garrett IR, Schwarz PM, Carnes DL, Lafer EM, Mundy GR, et al. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) confirms that MEPE binds to PHEX via the MEPE-ASARM motif: a model for impaired mineralization in X-linked rickets (HYP) Bone. 2005;36(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bresler D, Bruder J, Mohnike K, Fraser WD, Rowe PS. Serum MEPE-ASARM-peptides are elevated in X-linked rickets (HYP): implications for phosphaturia and rickets. J Endo. 2004;183(3):R1–9. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashibara T, Hiraga T, Yi B, Nomizu M, Kumagai Y, Nishimura R, et al. A synthetic peptide fragment of human MEPE stimulates new bone formation in vitro and in vivo. J Bone Min Res. 2004;19(3):455–62. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gluhak-Heinrich J, Gu S, Pavlin D, Jiang JX. Mechanical loading stimulates expression of connexin 43 in alveolar bone cells in the tooth movement model. Cell Comm Adhes. 2006;13:115–25. doi: 10.1080/15419060600634619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]