Abstract

Background

Poor cognition and low body weight are independent predictors of hip fracture in older persons.

Objective

Examine the interactive effect of cognition and body weight on hip fracture.

Design

A 7-year (1993 – 2000) prospective cohort study.

Setting

Five southwestern states (Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and California).

Participants

Non-institutionalized Mexican Americans (n = 2,653) 65 years or older, hip fracture free at baseline interview.

Measurements

Incidence of hip fracture at 2-, 5- and 7-year follow-up interviews. Body weight and cognition were measured with the body mass index (BMI) and Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), respectively. Covariates included sociodemographics, self-reported medical conditions, visual acuity and Short Physical Performance Battery.

Results

A significant interaction between BMI and hip fracture was found in persons with cognitive impairment (HR = 0.91; 95% CI = 0.85 – 0.98; p = 0.02), after adjusting for covariates. In the lowest BMI category, the hip fracture rate in cognitively impaired subjects was more than four times the hip fracture rate for non-cognitively impaired subjects with the same BMI (34.6% vs. 8.7%). Hip fracture rates in the highest BMI category were similar in persons with and without cognitive impairment (9.3% versus 6.1%).

Conclusion

Low cognitive function increased the conditional association between BMI and hip fracture in Mexican American older adults. The relationship between BMI and cognition is potentially important in identifying persons at risk for hip fracture and support the need to include cognitive and anthropometric measures in the assessment of hip fracture risk into osteoporosis screening programs.

Keywords: aging, dementia, disability, fracture, minority health

Introduction

It is well-established that hip fractures increase with age. By age 90, one-third of women and one-sixth of men in the U.S. will experience a hip fracture.1 The incidence of hip fracture is projected to increase dramatically in the next 20 years (US Bureau of the Census, 2000). The increase will be most evident among persons 85 years and older. This is the fastest growing segment of the U.S. population.2 By 2040, the number of hip fractures will exceed 500,000.3

Less than 40% of patients experiencing a hip fracture recover their pre-fracture mobility.4 One-year mortality rates are also high, ranging from 15 to 20 percent5 and life expectancy is decreased by almost 2 years among those aged 80 or older.6 The estimated per patient cost of hip fracture ranges from $19,335 to $66,000 (1995 dollars).7

Risk factors for hip fracture include age, female gender, chronic medical conditions, heredity, smoking, medications and impaired visual function.8,9 These factors are associated with falls or loss of bone mineral density (BMD) in older adults. Weight loss and poor cognition are also predictors of hip fracture. In a prospective case-controlled study,10 a significant association between low body mass index (BMI) and hip fracture was found. An association has also been reported between low cognitive function and hip fracture. In a large community-based study of adults 75 and older, Guo and colleagues11 reported the risk of hip fracture was twofold higher among persons identified as cognitively impaired.

The possible interactive effect of BMI and cognition on hip fracture risk has not been examined. It is not known, for instance, if good cognitive function modulates the risk of hip fracture among underweight older adults. The purpose of this study was to examine evidence of an association between cognition and body weight on hip fracture risk using data from a large cohort of community-living Mexican American older adults. The aims were to determine the association between body weight and hip fracture, and examine whether cognition modified this association. We hypothesized that low BMI would be associated with increased risk of hip fracture in Mexican American older adults and this association would be moderated by cognitive function over a 7-year follow up.

Method

Sample

Data were obtained from the Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (H-EPESE), a longitudinal, population-based study of non-institutionalized Mexican Americans aged 65 and over, residing in five southwestern states: Texas, California, New Mexico, Colorado and Arizona.12 Individuals were selected by a multistage area probability cluster sample design that involved the selection of counties, census tracts and households. Initially, counties were selected if at least 6.6% of the population was Mexican American. In the second stage, census tracts from the 1990 U.S. census counts were selected with a probability proportional to the size of their older (age 65+) population. In the third stage, census blocks were randomized to obtain at least 400 households within each census tract. The sample represented approximately 500,000 Mexican Americans aged 65 and older living in the southwest. The Institutional Review Board of University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, granted approval of the study.

Informed consent was obtained from participants and in-home interviews were completed in Spanish or English by trained, bilingual interviewers. The total number of individuals surveyed at baseline was 3,050, with 2,873 interviewed in person and 177 (5.8%) by proxy.13 The response rate at baseline (1993/1994) was 83%.

The current study included individuals who were interviewed in-person, with complete information on the primary variables of interest, and who did not report a physician diagnosis of hip fracture at the baseline interview (n = 2,653). At the end of the 7-year follow up, 1,525 subjects were re-interviewed, 434 (16.4%) subjects refused to be re-interviewed or were lost to follow up, and 694 (26.2%) subjects were confirmed dead through the National Death Index (NDI) and reports from relatives. Subjects who refused to be re-interviewed or were lost to follow up did not significantly differ from the current sample by sociodemographic characteristics including age, sex, marital status or years of schooling, or by number of medical conditions.

Measures

Outcome

Hip Fracture

Incidence of hip fracture was assessed over a 7-year follow up period. Individuals were asked if they had a physician diagnosis of hip fracture since the last interview. If the response was positive, follow-up questions were asked regarding hospitalization and related services. At the 2, 5, and 7-year follow-up assessment interview, 30, 31, and 47 first-time hip fractures were reported, respectively. Main Independent Variables

Cognitive Function

Cognition was assessed using the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE). The MMSE is one of the most frequently used cognitive screening measures in studies of older adults.14 The English and Spanish versions of the MMSE were adopted from the Diagnostic Interview Scale (DIS) used in previous community surveys.15 The MMSE has a potential range of 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating poorer cognitive status. The MMSE was used both as a continuous and categorical variable (< 21 and = 21), based on previously established cut-points in older Mexican Americans.16 Individuals with MMSE scores < 21 were classified as low cognitive status and those with MMSE scores = 21 as high cognitive status.

Body Mass Index

Body Mass Index (BMI) was computed by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. The BMI was used as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable, based on previously established criteria. Four BMI categories were created underweight (< 22 kg/m2), normal weight (22 to < 25 kg/m2), overweight (25 to < 30 kg/m2) and obese (= 30 kg/m2).17

Covariates

Baseline sociodemographic variables included age, gender, marital status (married and unmarried), smoking status (current, former, or never), and education (0 to 6, 7 to 11 and 12 or more years). The presence of various medical conditions was assessed with a series of questions asking subjects if they had ever been told by a doctor that they had diabetes, heart attack, stroke or arthritis. A summary scale was created by summing the four medical conditions (range 0–4). A modified Snellen test using directional Es assessed distant visual acuity.18 Four visual categories were created and included individuals who were functionally blind (> 20/200), severely impaired (> 20/60 to 20/200), moderately impaired (> 20/40 to 20/60), and those with adequate vision (≥ 20/40). Lower extremity function was tested using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), which is comprised of three lower-body activities, a timed 4-meter walk, rising from a chair 5 times, and a hierarchical standing balance task.19 Performance on each lower body activity was classified on a scale ranging from 0 to 4, and when summed, the overall summary performance measure was scored from 0 to 12, where higher scores represented better lower-extremity functioning. The reliability of the assessment has been established with inter-rater and test-retest values ranging from .84 to .96.19

Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic, health-related and functional status variables were examined using descriptive and univariate statistics. Chi-square analysis assessed the number and percent of individuals who experienced a hip fracture over the 7-year follow-up period. The BMI cognition interaction, in relation to hip fracture, was tested using Cox proportional hazard models with and without adjustment for relevant risk factors. Model assumptions for the survival analysis were tested and met. All analyses used the SAS statistical software package version 9.0. (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Of the 2,653 study participants, 57.90% were female, 56.5% were married, 41.3% were current smokers, 73.5% reported 0 to 6 years of schooling, and the mean age was 72.5 (± SD 6.3). Self-reported arthritis (39.5%) and diabetes (27.1%) were the most common medical conditions. Adequate distant vision was found in 85.4%. Mean SPPB score was 6.93 (± SD 3.19).

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the sample stratified by low and high MMSE score (< 21 and ≥ 21). Older age, unmarried, fewer years of schooling, visual impairment, stroke and lower SPPB score were significantly associated (p < .05) with lower MMSE score (< 21). Non-significant associations with MMSE score were found for gender, smoking status, and number of medical conditions.

Table 1.

Demographic and selected health characteristics by MMSE score (N = 2,653).

| MMSE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristic | Low (< 21) N (%) | High ( ≥ 21) N (%) | p-value |

| Overall | 389 (14.7) | 2264 (85.3) | |

| Age | |||

| 65–74 | 182 (10.1) | 1621 (89.9) | .0001 |

| 75–84 | 155 (21.9) | 552 (78.1) | |

| ≥85 | 52 (36.4) | 91 (63.6) | |

| Sex | .19 | ||

| Male | 152 (13.6) | 965 (86.4) | |

| Female | 237 (15.4) | 1299 (84.6) | |

| Marital Status | .0001 | ||

| Married | 163 (10.9) | 1335 (89.1) | |

| Unmarried | 226 (19.6) | 929 (80.4) | |

| Education (years) | .0001 | ||

| 0–6 | 345 (17.9) | 1583 (82.1) | |

| 7–11 | 27 (6.1) | 418 (93.9) | |

| ≥12 | 6 (2.4) | 244 (97.6) | |

| Smoking Status | .11 | ||

| Current | 175 (16.0) | 920 (84.0) | |

| Former/Non | 214 (13.7) | 1344 (86.3) | |

| Vision Scale | .0001 | ||

| Functionally blind | 63 (48.8) | 66 (51.2) | |

| Severely impaired | 36 (37.1) | 61 (62.9) | |

| Moderately impaired | 31 (18.1) | 140 (81.9) | |

| Adequate vision | 259 (11.5) | 1997 (88.5) | |

| Medical Conditions | .23 | ||

| 0 | 155 (14.1) | 944 (85.9) | |

| 1 | 153 (14.3) | 915 (85.7) | |

| ≥ 2 | 81 (16.7) | 405 (83.3) | |

| SPPB | .0001 | ||

| 0–3 | 135 (33.2) | 272 (66.9) | |

| 4–6 | 84 (13.5) | 538 (86.5) | |

| 7–9 | 112 (10.8) | 926 (89.2) | |

| 10–12 | 58 (9.9) | 528 (90.1) | |

MMSE = Mini Mental State Exam

SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery

Medical Conditions = heart attack, stroke, diabetes, and arthritis

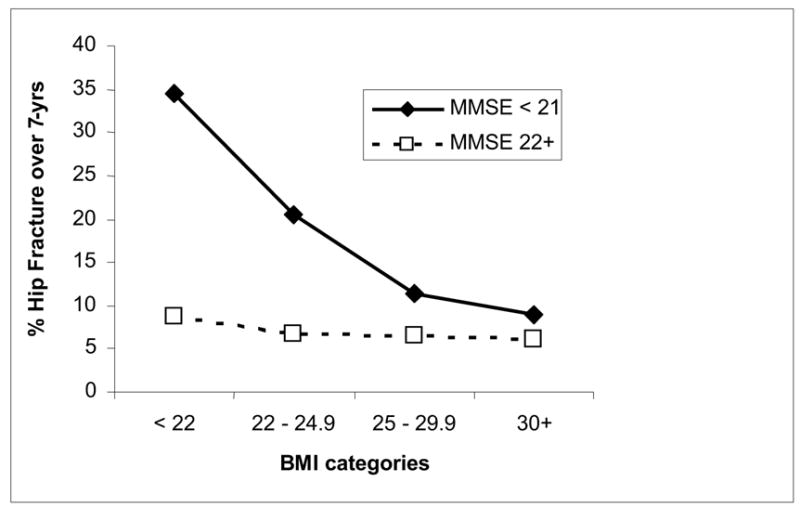

Next, the interaction effect between BMI and cognition on hip fracture was tested. Unadjusted results showed a significant interaction between the continuous BMI and MMSE variables (p = .02). Figure 1 shows the interaction between the 4-level BMI measure and low (< 21) and high (≥ 21) MMSE scores on hip fracture incidence. Low MMSE scores were associated with a higher risk of hip fracture across each of the 4 BMI levels. The largest difference was observed in the underweight (BMI < 22) category. For individuals classified with higher MMSE scores, the association between BMI and hip fracture was similar ranging from 8.7% in the underweight group (BMI < 22) to 6.1% in the obese group (BMI ≥ 30). For individuals classified with lower MMSE scores, the association between BMI and hip fracture was statistically significantly (p < .001), ranging from 34.6% in the underweight group to 9.3% in the obese group.

Figure 1.

Percent of hip fractures over seven years by MMSE score and BMI.

Table 2 shows the association between BMI and hip fracture by lower and higher MMSE scores, with adjustment for demographic and health factors. In Model 1, each 1-unit increase in BMI was associated with 9% decreased risk of hip fracture (HR = 0.91; 95% CI = 0.85 – 0.98) for persons with lower MMSE scores. In Model 2, a non-significant association was found between BMI and hip fracture (HR = 0.98; 95% CI = 0.94 – 1.03) for persons in the higher MMSE group.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis assessing risk of hip fracture, over a 7-year period, in cognitive and non-cognitive impaired older Mexican-Americans hip fracture free at baseline interview, adjusting for relevant risk factors (N = 2,653).

| Hip Fracture | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 MMSE < 21 (N = 389) Hip Fracture events = 28 | Model 2 MMSE ≥ 21 (N = 2,264) Hip Fracture events = 80 | |||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 0.91 | 0.85 – 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.94 –1.03 |

| Age (years) | 1.03 | 0.97 – 1.10 | 1.03 | 0.99 –1.07 |

| Female | 1.05 | 0.43 – 2.58 | 1.45 | 0.85 –2.49 |

| Unmarried | 1.39 | 0.59 – 3.28 | 0.90 | 0.55 –1.47 |

| Current Smoker | 1.20 | 0.53 – 2.71 | 0.81 | 0.49 –1.34 |

| Vision Scale | 1.05 | 0.74 – 1.49 | 1.08 | 0.74 –1.59 |

| SPPB (0 – 12) | 0.89 | 0.79 – 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.87 –1.02 |

| Medical conditions (0 – 4) | 0.82 | 0.47 – 1.41 | 1.30 | 1.00 –1.68 |

MMSE = Mini Mental State Exam

BMI = Body Mass Index

SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery

Medical conditions = heart attack, stroke, diabetes, and arthritis

HR = Hazard Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval

Discussion

We found cognition modified the association between BMI and hip fracture in a large cohort of community-living older Mexican Americans over a 7-year follow-up period. Though underweight (BMI < 22) individuals were at the greatest risk for hip fracture, the risk was greater among persons with lower MMSE (< 21) scores. For persons in the higher and lower MMSE groups, higher BMI was associated with a lower risk of hip fracture. Among those categorized as obese (BMI ≥ 30) the risk of hip fracture was approximately equal.

Previous studies have reported an inverse relationship between body weight and risk of hip fracture.9,10,20 Ensrud et al.20 found a 10% loss in weight significantly increased the risk of hip fracture in persons over 65 years. In a study of older non-Hispanic white women, Grisso et al. (1991) found higher BMI significantly reduced the risk of hip fracture. These studies, however, did not analyzed whether cognition modulates the risk of hip fracture among underweight older adults.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the association between BMI and hip fracture. One hypothesis suggests that low weight may be a marker of underlying clinical conditions, including declining physical health status, frailty, subclinical disease or chronic inflammation, all of which may increase the risk of falls and fractures. Another hypothesis suggests that being underweight is associated with loss of bone mineral density, which in turn increases the risk of hip fracture. Numerous studies have found higher bone mineral density among heavier individuals; and conversely lower bone mineral density among those who are underweight.21,22

Our results confirm low BMI is a marker for hip fracture in older Mexican American adults; however, BMI may need to be considered in combination with other potential risk factors including cognitive ability, where the incidence of hip fracture, especially in older adults, is high. In a study of older women with poor cognition, the hip fracture rate was 70 per 1000 patient-years compared with a rate of 3 per 1000 patient-years for a reference population aged between 70 and 79 years.23 When we stratified our analysis by MMSE scores, a modest association was found between BMI and hip fracture for persons in the higher MMSE group. In contrast, a strong association between BMI and hip fracture was found among persons in the lower MMSE group.

Low cognition has been shown to compromise the adaptive and coping ability of older adults to environmental demands or medical stressors. This lack of ability to adapt may translate into less physical activity, poor adherence to treatment regimen, and poor motivation to engage in healthy lifestyles. Malnutrition, especially common in older cognitively impaired adults24, can lead to metabolic disturbances such as negative calcium balance and promote osteoporosis. On the other hand, our findings suggest that cognitively impaired older adults who maintain good mobility function may reduce their risk of hip fracture. This finding is of interest and warrants further study, as it offers the possibility that exercise intervention programs (e.g., balance or strength training) designed for underweight older adults in cognitive decline may protect against hip fracture.

The investigation has the following strengths. We collected longitudinal information from a large, well-defined sample representative of 500,000 Mexican Americans in the southwestern United States. The reliability and consistency of the data collection procedures in the Hispanic EPESE investigation are well established. Our sample included both men and women whereas, many previous studies on risk factors for hip fracture have focused on non-Hispanic white women.

There were limitations to the study, we did not have access to medical records or x-rays to confirm the occurrence of hip fracture; however, previous research has reported good validity for self-reported medical conditions confirmed by physician diagnosis.25 Because this was a community-based study, no information was available on institutionalized older Mexican Americans. The relation between low body weight and cognition may be particularly important for institutionalized individuals who are at highest risk for diminished cognition and also at high risk for hip fracture.26 Finally, no measure of falls was included in the first three waves of the H-EPESE database. Future studies are needed to examine the possible moderating effect falls may have on the association between BMI and hip fracture among those with declining cognitive abilities.

Our findings also suggest the need to look at predisposing factors in combination and to include cognitive and anthropometric measures in the assessment of hip fracture risk into osteoporosis screening programs. Additional research is necessary to verify these findings and to begin examining whether nutritional or other intervention programs can reduce the risk of hip fracture in older adults, particularly among those with reduced cognition.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure(s):

This research was supported by funds from the National Institute of Aging, National Institutes of Health, including R01 AG017638, K02 AG019736 (Ottenbacher), R01 AG024806, K01 HD046682 (Ostir), and R01 AG010939 (Markides).

Dr. Alfaro-Acha was a PAHO/WHO Collaborating Center on Aging and Health visiting scholar at the University of Texas Medical Branch, during the period this research was completed. There are no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions:

Ana Alfaro-Acha: Concept, analysis of data, interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript.

Glenn V. Ostir: Writing original and revising drafts of manuscript, contributed to data analysis and interpretation of data.

Kyriakos S. Markides: Contributed to revisions of manuscript, interpretation of data, and funding.

Kenneth J. Ottenbacher: Concept and hypothesis development, revising manuscript, and interpretation of data.

Sponsor’s Role:

National Institutes of Health (NIH) had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The final, definitive version of this article has been published in the Journal of the American Geriatric Society, August 2006 - Vol. 54 Issue 8 Page 1169-1307 Copyright by The American Geriatrics Society and Blackwell Publishing. The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com’

References

- 1.Hochberg MC, Williamson J, Skinner EA, et al. The prevalence and impact of self-reported hip fracture in elderly community-dwelling women: the Women's Health and Aging Study. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:385–389. doi: 10.1007/s001980050079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popovic JR. National Hospital Discharge Survey: annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Stat. 1999;2001;13:i–206. doi: 10.1037/e309042005-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummings SR, Rubin SM, Black D. The future of hip fractures in the United States. Numbers, costs, and potential effects of postmenopausal estrogen. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;252:163–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koot VC, Peeters PH, de Jong JR, et al. Functional results after treatment of hip fracture: a multicentre, prospective study in 215 patients. Eur J Surg. 2000;166:480–485. doi: 10.1080/110241500750008808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Genant HK, Cooper C, Poor G, et al. Interim report and recommendations of the World Health Organization Task-Force for Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1999;10:259–264. doi: 10.1007/s001980050224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braithwaite RS, Col NF, Wong JB. Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:364–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brainsky A, Glick H, Lydick E, et al. The economic cost of hip fractures in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandler JM, Zimmerman SI, Girman CJ, et al. Low bone mineral density and risk of fracture in white female nursing home residents. JAMA. 2000;284:972–977. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.8.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girman CJ, Chandler JM, Zimmerman SI, et al. Prediction of fracture in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1341–1347. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenspan SL, Myers ER, Maitland LA, et al. Fall severity and bone mineral density as risk factors for hip fracture in ambulatory elderly. JAMA. 1994;271:128–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo Z, Wills P, Viitanen M, et al. Cognitive impairment, drug use, and the risk of hip fracture in persons over 75 years old: a community-based prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:887–892. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markides KS, Rudkin L, Angel RJ, et al. Health status of Hispanic elderly in the United States. In: Martin LJ, Soldo B, editors. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Health of Older Americans. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. pp. 285–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markides KS, Stroup-Benham CA, Black SA, et al. The health of Mexican American Elderly: selected findings from the Hispanic EPESE. In: Wykle ML, Ford AB, editors. Serving Minority Elders in the Twenty-first Century. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 1999. pp. 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bird HR, Canino G, Stipec MR, et al. Use of the Mini-mental State Examination in a probability sample of a Hispanic population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175:731–737. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198712000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ostir GV, Raji MA, Ottenbacher KJ, et al. Cognitive function and incidence of stroke in older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:531–535. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.6.m531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostir GV, Markides KS, Freeman DH, Jr, et al. Obesity and health conditions in elderly Mexican Americans: the Hispanic EPESE. Established Population for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. Ethn Dis. 2000;10:31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salive ME, Guralnik J, Christen W, et al. Functional blindness and visual impairment in older adults from three communities. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1840–1847. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31715-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ensrud KE, Lipschutz RC, Cauley JA, et al. Body size and hip fracture risk in older women: a prospective study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Am J Med. 1997;103:274–280. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrera G, Bunout D, Gattas V, et al. A high body mass index protects against femoral neck osteoporosis in healthy elderly subjects. Nutrition. 2004:769–771. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhee EJ, Oh KW, Lee WY, et al. Age, body mass index, current smoking history, and serum insulin-like growth factor-I levels associated with bone mineral density in middle-aged Korean men. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004;22:392–398. doi: 10.1007/s00774-003-0500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato Y, Kanoko T, Satoh K, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture among elderly patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Sci. 2004;223:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irving GF, Olsson BA, Cederholm T. Nutritional and cognitive status in elderly subjects living in service flats, and the effect of nutrition education on personnel. Gerontology. 1999;45:187–194. doi: 10.1159/000022085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, et al. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Doorn C, Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S, et al. Dementia as a risk factor for falls and fall injuries among nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1213–1218. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]