Abstract

Fluoride-based deprotection of silylated 2-alkynylbenzyl alcohol derivatives featuring carbonyl-substituted alkynes results in the direct synthesis of alkylidenephthalan vinylogous esters. The reaction is selective for the Z alkylidenephthalans in a thermodynamically controlled process. Similar compounds are also produced in the coupling of Fischer carbene complexes with 2-alkynylbenzoyl derivatives in an aqueous solvent system. Subsequent acid-catalyzed inter- or intramolecular Diels-Alder reactions lead to hydronaphthalene or hydrophenanthrene derivatives.

Introduction

Alkylidenephthalans (e.g. 1, Scheme 1) have proven to be very useful compounds for organic synthesis due to their equilibration with highly reactive isobenzofurans (2) upon protonation.1 Alkylidenephthalans that contain remote alkene functionality can undergo cyclization upon treatment with acid in a process involving formation of an isobenzofuran followed by intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction.2 Alkylidenephthalans are most often prepared through carbonyl olefination of phthalides.3 Other methods include oxidative carbonylation of o-alkynylbenzyl alcohols4 and coupling of Fischer carbene complexes with o-alkynylbenzoyl compounds.5

Scheme 1.

In several recent manuscripts, we have reported that net [5+5]-cycloaddition (coupling of 4 and 5 to produce either 10 or 11, Scheme 2) leading to the hydrophenanthrene ring system occurs when o-alkynylbenzoyl compounds couple with γ,δ-unsaturated Fischer carbene complexes.6 This process proceeds through a tandem process involving carbenealkyne coupling, followed by isobenzofuran formation, followed by intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction, followed by either ring opening to afford 10 or dehydration to afford 11.7 In the absence of a Diels-Alder trap, the formation of alkylidenephthalans (e.g. 14) has been observed in isolated examples.5 A serious limitation in this method is that in some cases the γ,δ-unsaturated carbene complexes are either difficult to synthesize or are too unstable to undergo thermal coupling with alkynes.8 As part of a program to develop alternatives to the carbene methodology, a parallel strategy for the formation of hydrophenanthrenes from o-substituted phenylacetylene derivatives was sought. This alternative strategy, depicted in Scheme 3, would involve an alkyne-based synthesis of alkylidenephthalans followed by the Diels-Alder strategy in Scheme 1. 9 In a preliminary examination of this synthetic route, it was noted that the silyl deprotection step resulted in the alkylidenephthalan. While this work was in progress, a similar cyclization of alkynylpurinyl benzyl alcohols was reported.10 This manuscript focuses on the development of this alkylidenephthalan vinylogous ester synthesis and subsequent inter- and intramolecular Diels-Alder reactions.

Scheme 2.

Scheme 3.

Results and Discussion

General synthetic routes to the 2-alkynylbenzyl alcohol derivatives used in this study are depicted in Scheme 4.11 The routes involve either Sonogashira coupling of known 2-iodobenzyl alcohol derivatives with propargyl alcohol derivatives followed by oxidation (eq 1), or a strategy that closely parallels the synthetic plan of Scheme 3 involving acylation of 2-ethynylbenzyl alcohol derivatives (eq 2).

Scheme 4.

Attempted deprotection of the silicon ether 26a (Scheme 5) with tetrabutylammonium fluoride led to a compound tentatively identified as alkylidenephthalan 27a as a Z:E mixture (predominantly Z). Despite separation and isolation of a compound corresponding to a unique TLC spot, the product always showed the appearance of an n-butyl group in the NMR spectrum. A pure compound free of contaminants was obtained when potassium fluoride in methanol was employed for the desilylation step of the reaction. Although the Z and E isomers have very different chromatographic properties, when the isomers were separated by chromatography the compounds corresponding to each spot appeared as identical 83:17 Z:E mixtures. This observation suggests that the isomers interconvert on silica gel.

Scheme 5.

A systematic study of the fluoride-induced cyclization reaction was conducted. The results are depicted in Table 1. In all of the cases employing a primary alcohol-derived silane, a good yield of alkylidenephthalan was obtained from the reaction with fluoride ion in methanol at 55 °C. Difficulty was encountered in secondary alcohol-derived silyl ether in Entry E. In this case the reaction was sluggish and lower yielding. Higher temperatures in the polar aprotic solvent DMF were required for this reaction process. Under these conditions, a significant amount of the retroaldol product 28 was observed. In all of the cases the Z alkylidenephthalan was obtained as the major isomer.

Table 1.

Preparation of alkylidenephthalans through treatment of silyl-protected o-ethynylbenzyl alcohols with fluoride ion.

| Entrya | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | Yield 27 | Z:E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Me | H | H | H | 74% | 83:17 |

| B | Ph | H | H | H | 80% | 91:9 |

| C | OMe | H | H | H | 98% | > 95:5 |

| D | NMe2 | H | H | H | 75% | 75:25b |

| Ec | Me | Me | H | H | 51% | > 95:5 |

| F | Me | H | OMe | OMe | 46% | 93:7 |

| G | Me | H | OMe | H | 74% | > 95:5 |

Table 1 Entry letters match substituent identifier letters for compounds 4 and 26-28.

In this cases the isomeric compounds can be separated.

In this case anhydrous KF in DMF was employed.

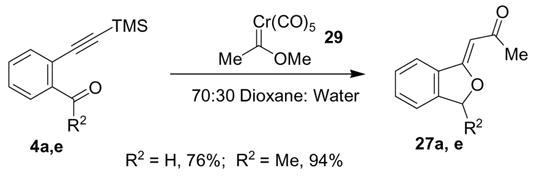

A comparison of the fluoride-based alkylidenephthalan synthesis in Table 1 with carbene complex-based alkylidenephthalan syntheses was also conducted (Scheme 6). Alkylidenephthalans were observed as side products in various failed examples of the [5+5]-cycloaddition reaction conducted in aqueous solvent systems, and these conditions were employed for the coupling of simple carbene complex 29 with alkyne-carbonyl compounds 4a and 4e.6 The carbene complex based synthesis was highly efficient in the two examples depicted, and afforded the alkylidenephthalans27a and 27e in the same E:Z ratio as the fluoride-based syntheses in Table 1. The carbene complex method is superior in that the 2-alkynylbenzaldehyde and analogous acetophenone derivatives are more readily available substrates. All of the silyl ether-based syntheses required a more lengthy synthesis from commercially-available chemicals.

Scheme 6.

Both the fluoride-induced and the carbene complex-based alkylidenephthalan syntheses afforded predominantly the Z isomer in all of the cases. The E configuration was assigned to the minor stereoisomer based on a distinctive feature in the proton NMR spectrum. The hydrogen labeled HA (see the picture in Table 2) appears at a very high chemical shift (δ 9.0 – 9.5) in all of the minor isomers. This observation has been noted by others for alkylidenephthalan vinylogous esters, and is supported in those cases through NOE studies.12 Other investigators noted a similar high chemical shift proton in a related compound where there is a purine ring in place of the ketone group, and attributed this observation to a hydrogen bonding interaction between HA and a nitrogen atom of the purine ring.10 An ab initio NMR calculation at the 6-311G* level predicts this unusually high chemical shift (see Table 2). This unusual chemical shift most likely arises from an anisotropic interaction with the carbonyl oxygen of the ketone group.13

Table 2.

Various experimental and theoretical data for the E and Z isomers of compound 27a.

| Observation | Value for Z | Value for E |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical shift of HA (observed) | 7.70–7.35 | 9.35 |

| Chemical shift of HA (calculated) | 6.76 | 9.57 |

| Chemical shift of HB (observed) | 5.83 | 6.11 |

| Chemical shift of HB (calculated) | 5.28 | 5.61 |

| Energy Relative to E (Experimental) | −1.1 kcal/mol | 0 |

| Energy Relative to E (6-311G**) | +1.0 kcal/mol | 0 |

| Energy relative to E (6-31G*) | +1.1 kcal/mol | 0 |

| Energy relative to E (PM3) | +1.4 kcal/mol | 0 |

| Energy relative to E (MM-2) | −6.3 kcal/mol | 0 |

In general the E configuration is more stable for β-alkoxy enones due primarily to electronic reasons,14 however in our cases there is likely a steric interaction of the carbonyl group and HA disfavoring the E isomer. The E isomer is the product of most syntheses of alkylidenetetrahydofurans that proceed through intramolecular nucleophilic addition of an alkoxide to an electron-deficient alkyne. In one case a similar reaction process led to predominantly the Z isomer and was attributed to steric effects.15 The Z isomer was also the major isomer obtained in the alkynylpurinyl systems previously reported; this synthetic route was also based on fluoride-induced desilylation/cyclization, and alternate conditions employing acid led also to the Z isomer.10 Even though the Z and E isomers of the alkylidenephthalans appear as distinctive TLC spots, in most cases attempted separation never produced a pure isomer, thus suggesting that there is interconversion on either the chromatography column or in the slightly acidic NMR solvent, chloroform. In one case (Entry D) the isomers were separable and did not equilibrate on the chromatography column. Thus the Z isomer would appear to be the more stable (thermodynamic) product, or possibly both the kinetic and thermodynamic product. Calculations were performed to better understand the isomer distribution; the results are depicted in Table 2. The apparent 83:17 equilibrium ratio implies that the Z isomer is 1.1 kcal/mol more stable than the E isomer. Both ab initio16 and semiemprical calculations suggest that the E isomers is the more stable isomer, however this number is within the experimental error of the calculation. The less sophisticated MM2 analysis suggests that the Z isomer is more stable, however the observed number (Z more stable than E by 6.3 kcal/mol – error of 4.2 kcal/mol relative to experiment) reflects a bigger error from experiment than the ab initio calculations (E more stable than Z by 1.1 kcal/mol – error of 2.2 kcal/mol relative to experiment). In the MM2-minimized structure of the E isomer, the C=O and adjacent C=C groups are not coplanar (dihedral angle = 26°), which suggests that the electronic stabilization present in the vinylogous ester system is poorly recognized by this basis set. The Z isomer is also likely to be the kinetic product of the reaction based on the structure of the enolate intermediate 30. The enolate intermediate has a bent structure and protonation of the enolate intermediate obtained from the convex direction would afford the observed Z alkene. The carbene complex route also leads to the Z stereoisomer. In this case the Z stereochemistry can arise through hydrolysis of the enol ether generated through 1,7-hydrogen shift of the intermediate isobenzofuran (see interconversion of 12 and 13 in Scheme 2).17

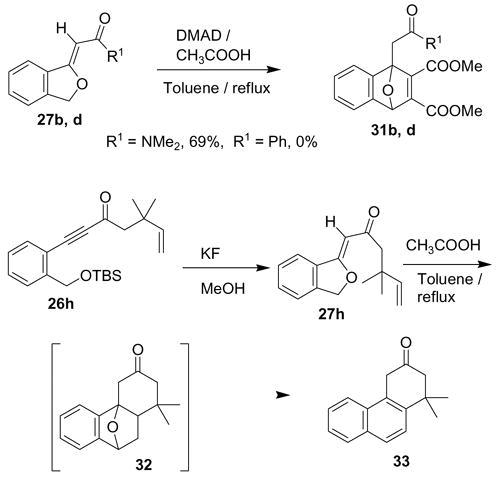

The alkylidenephthalan vinylogous esters readily underwent Diels-Alder reactions (Scheme 7). Simple treatment of alkylidenephthalan 27d and acetylenedicarboxylate (DMAD) with a catalytic amount of acetic acid in the presence of refluxing toluene led to the desired Diels-Alder adduct 31d. In the original publication on this reaction,2 DMAD was used as the reaction solvent, however under these conditions the separation of the Diels-Alder adduct from polymeric DMAD species was quite difficult. The reaction was not effective for cases where R1 is a phenyl group, likely due to the greater electron withdrawing power of this substituent. Although the Diels-Alder reaction was reported to fail for butenylketones (R1 = −CH2CH2CH=CH2), the reaction was highly efficient using the analogous compound 27h which features a gem dimethyl group in the chain. In this case the Diels-Alder adduct/dehydration product 33 was produced in 78% yield. The success in this case is likely due to the gem dialkyl effect,18 which introduces a conformational bias favoring the Diels-Alder reaction.

Scheme 7.

Conclusions

In summary, simple desilylation of electron deficient silylated 2-alkynylbenzyl alcohol derivatives leads directly to alkylidenephthalan derivatives. The reaction is highly selective for formation of the Z stereoisomer, which is easily assigned due to the absence of the anisotropic interactions expected for the E isomer. The same alkylidenephthalan can also be prepared through the reaction of 2-alkynylbenzoyl derivatives with Fischer carbene-chromium complexes in aqueous solvent systems. The alkylidenephthalans readily undergo Diels-Alder reactions when treated with DMAD in the presence of acid, and undergo intramolecular Diels-Alder reactions in systems where conformational effects are favorable.

Experimental

General Procedure I - Preparation of alkylidenephthalans via fluoride-induced cyclization. A 0.05-0.10M solution of silyl-protected alkynol (1.0 eq) and potassium fluoride dihydrate (5 eq) in methanol was stirred at 55 °C until TLC analysis showed complete consumption of starting material (usually about 2 h). The solvent was removed on a rotary evaporator and then placed into a mixture of water and dichloromethane in a separatory funnel. The water layer was extracted two times with dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were washed with water and saturated aqueous sodium chloride solution, and then dried over sodium sulfate. The solvent was removed on a rotary evaporator and the residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel using hexane: ethyl acetate mixtures as the eluent.

Preparation of alkylidenephthalan-methyl ketone 27a. General Procedure I was followed using alkyne-methyl ketone 26a (0.285 g, 0.980 mmol) and potassium fluoride dihydrate (0.288 g, 3.06 mmol) in 20 mL of methanol. Final purification was achieved by flash chromatography on silica gel using 4:1 hexane: ethyl acetate followed by 2:1 hexane: ethyl acetate as eluent. A single compound identified as an 83:17 Z:E mixture of compound 27a was obtained (0.109 g, 63 % yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.70–7.35 (m, 4H), 5.83 (s, 1H), 5.58 (s, 2H), 2.46 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 197.6, 167.4, 141.8, 135.6, 132.0, 129.2, 121.8, 98.2, 77.0, 31.4; IR (neat): 1671 (m), 1624 (vs), 1590 (s) cm-1; Mass Spec (EI): 174 (M, 25), 159 (100), 131 (37), 103 (91), 77 (68); HRMS (EI): Calcd for C11H10O2 174.06808, found 174.06751. A minor isomer (18%) can be detected in the proton NMR spectrum and has been assigned as the E enol ether. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 9.35 (br d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz); 7.70–7.35 (peaks overlap with major isomer); 6.11 (s, 1H), 5.39 (s, 2H), 2.27 (s, 3H).

Preparation of alkylidenephthalan-phenyl ketone 27b. General Procedure I was followed using alkyne-phenyl ketone 26b (0.809 g, 2.31 mmol) and potassium fluoride dihydrate (1.090 g, 11.56 mmol) in 20 mL of methanol. Final purification was achieved by flash chromatography on silica gel using 4:1 hexane: ethyl acetate followed by 1:1 hexane: ethyl acetate as eluent. A single fraction identified as a 91:9 Z:E mixture of compound 27b was obtained (0.435 g, 80 % yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.11–7.93 (m, 2H), 7.82–7.70 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.63–7.35 (m, 6H), 6.65 (s, 1H), 5.65 (s, 2H), 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 187.8, 168.4, 141.4, 139.6, 132.8, 131.2, 128.1, 127.8, 127.7, 127.2, 127.1, 121.2, 121.0, 91.0, 76.5; IR: 1655 (s), 1599 (vs), 1571 (s) cm−1; Mass Spec (EI): 236 (M, 30), 159 (51), 131 (13), 105 (95), 77 (100); HRMS (EI): Calcd for C16H12O2 236.08373, found 236.08387. A trace amount of another isomer can be detected in the proton NMR spectrum and has been assigned as the E enol ether. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 9.41 (br d, 1H, j = 8.0 Hz); 8.11–7.93 (peaks overlap with major isomer), 7.63–7.35 (peaks overlap with major isomer), 6.79 (s, 1H), 5.60 (s, 1H), 5.39 (s, 2H).

Preparation of alkylidenephthalan-ester 27c. General Procedure I was followed using the alkyne-ester 26c (0.460 g, 1.51 mmol) and potassium fluoride dihydrate (0.711 g, 7.56 mmol) in 20 mL of methanol. Final purification was achieved by flash chromatography on silica gel using 9:1 hexane: ethyl acetate followed by 2:1 hexane: ethyl acetate as eluent. A single compound identified as a > 95:5 Z:E mixture of compound 27c was obtained (0.233 g, 98% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.58–7.34 (m, 4H), 5.53 (s, 2H), 5.48 (s, 1H), 3.76 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 168.4, 167.1, 141.8, 133.4, 131.7, 128.9, 121.9, 121.7, 86.1, 76.9, 51.3; IR (neat): 1710 (m), 1693 (s), 1634 (vs) cm−1. A trace amount of another isomer can be detected in the proton NMR spectrum and has been assigned as the E enol ether. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 9.41 (br d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz); 7.58–7.35 (peaks overlap with major isomer), 5.60 (s, 1H), 5.31 (s, 2H), 3.69 (s, 3H). The spectral data were in agreement with those previously reported for this compound.4

Preparation of alkylidenephthalan-amide 27d. General Procedure I was followed using the alkyne-amide 26d (0.450 g, 1.42 mmol) and potassium fluoride dihydrate (0.667 g, 7.10 mmol) in 20 mL of methanol. Final purification was achieved by flash chromatography on silica gel using 2:1 hexane: ethyl acetate as eluent. In the first experimental run, the Z and E isomers were not separated. Chromatography afforded a 75:25 Z:E mixture of compound 27d (0.207 g, 72 % yield). A more careful chromatography afforded a nearly baseline separation of two isomers. The major compound in the second fraction was identified as the Z isomer of 27d (0.207 g, 72 % yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.30 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.21–7.02 (m, 3H), 5.45 (s, 1H), 5.20 (s, 2H), 2.82 (br s, 3H), 2.76 (br s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 165.9, 162.8, 140.0, 132.6, 129.7, 127.4, 120.6, 120.1, 85.9, 74.9, 37.5 (broadened), 34.0 (broadened); IR: 1647 cm−1; Mass Spec (EI): 203 (12), 173 (29), 159 (100), 149 (15), 131 (36), 103 (61); HRMS (EI): Calcd for C12H13NO2 203.09463, found 203.09516. The minor compound in the first fraction was identified as the E enol ether. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.82 (dd, 1H, J = 8.0, 2.0 Hz), 7.45–7.25 (m, 3H), 5.82 (s, 1H), 5.30 (s, 2H), 3.17 (2 nearly coalesced singlets, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 167.4, 167.0, 142.9, 131.1, 130.6, 128.1, 127.7, 120.4, 91.9, 73.2, 38.2 (broadened), 35.5 (broadened).

Preparation of alkylidenephthalan-methyl ketone 27e. Dry potassium fluoride19 (0.176 g, 1.88 mmol) was added to a solution of the alkyne-methyl ketone 26e (0.190 g 0.625 mmol) in DMF (10 mL). The solution was then heated to 60 °C and stirred for 2 days under a nitrogen atmosphere. After the reaction had cooled to room temperature, water (10 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted two times with ether and washed with saturated aqueous sodium bicarbonate solution. Flash chromatography on silica gel using 4:1 hexane: ethyl acetate as eluent afforded several fractions. The product in the first fraction (0.030 g) was identified as predominantly recovered starting material. The product in the second fraction (< 0.005 g) was not identified. The product in the third fraction was identified as retroaldol product 28 was obtained, and the amount varied widely for different experimental runs. 1H NMR (CDCl3): 7.90-7.30 (m, 4H), 5.54 (q, 1H, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.62 (d, 3H, J = 6.8 Hz); IR (neat): 1765 cm−1. The spectral data were in agreement with those previously reported for this compound.20. The product in the fourth fraction was identified as the Z alkylidenephthalan 27e (0.060 g, 51% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.56 (d, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.50 (td, 1H, J = 7.6, 0.4 Hz), 7.41 (t, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.33 (dd, 1H, J = 7.6, 0.4 Hz), 5.79 (q, 1H, J = 6.7 Hz), 5.75 (s, 1H), 2.45 (s, 3H), 1.64 (d, 3H, J = 6.7 Hz); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 197.2, 165.9, 145.8, 132.8, 131.5, 128.7, 121.8, 121.0, 97.6, 84.5, 25.7, 20.9; IR (neat): 1651 (m), 1629 (s), 1605 (s) cm−1; Mass Spec (CI): 189 (M+1, 100), 173 (37).

Preparation of alkylidenephthalan-methyl ketone 27f. General Procedure I was followed using alkyne methyl ketone 26f (0.130 g, 0.37 mmol) and potassium fluoride dihydrate (0.176 g, 1.87 mmol) in 20 mL of methanol. Final purification was achieved by flash chromatography on silica gel using 2:1 hexane: ethyl acetate as eluent. A single compound identified as a 93:7 Z:E mixture of alkylidenephthalan 27f was obtained (0.040 g, 46% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.97 (s, 1H), 6.87 (s, 1H), 5.68 (s, 1H), 5.48 (s, 2H), 3.93 (s, 3H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 2.41 (s, 3H). The spectral data agree with those previously reported for this compound.2 A trace amount of another isomer can be detected in the proton NMR spectrum and has been assigned as the E enol ether. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 9.41 (br s, 1H)), 6.97 (signal overlaps with peak for the major isomer), 6.86 (signal overlaps with peak for the major isomer), 5.93 (s, 1H), 5.30 (s, 2H), 2.23 (s, 3H).

Preparation of alkylidenephthalan-methyl ketone 27g. General Procedure I was followed using the alkyne-methyl ketone 26g (0.140 g, 0.44 mmol) and potassium fluoride dihydrate (0.206 g, 2.20 mmol) in 20 mL of methanol. Final purification was achieved by flash chromatography on silica gel using 2:1 hexane: ethyl acetate as eluent. A single compound identified as a > 95:5 Z:E mixture of compound 27g was obtained (0.067 g, 74 % yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.48 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.94 (dd, 1H, J = 8.8, 2.2 Hz), 6.87 (br s, 1H), 5.68 (s, 1H, 5.48 (s, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 2.39 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 196.8, 167.2, 163.0, 143.7, 125.4, 123.2, 116.0, 105.6, 96.3, 76.1, 55.7, 30.7; IR (neat): 1624 (s) cm−1; Mass Spec (EI): 204 (M, 31), 189 (100), 161 (19), 133 (30); HRMS (EI): Calcd for C12H12O3 204.07864, found 204.07835. A trace amount of another isomer can be detected in the proton NMR spectrum and has been assigned as the E enol ether. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 9.26 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.80–7.00 (signal overlaps with peaks for the major isomer), 5.95 (s, 1H), 5.30 (s, 2H), 3.85 (signal overlaps with major isomer), 2.23 (s, 3H).

General Procedure II. Carbene complex-based alkylidenephthalan synthesis. A mixture of carbene complex 2921 (1.3 eq) and alkynylphenylketone/aldehyde (1.0 eq) in 70:30 dioxane:water was heated to reflux for 12 h. The solution was cooled and filtered through Celite. The filtrate was poured into a mixture of water and ether in a separatory funnel. The organic layer was washed with water and with saturated aqueous sodium chloride solution, and then dried over sodium sulfate. The organic layer was filtered through a pad of silica gel and the solvent was removed on a rotary evaporator to afford the pure product. Use of excess carbene complex was a necessity, otherwise substantial amounts of unreacted alkyne were observed.

Preparation of alkylidenephthalan 27a via the carbene complex route. General Procedure II was followed using 2-trimethylsilylethynylbenzaldehyde22 (0.507 g, 2.50 mmol) and carbene complex 29 (0.815 g, 3.30 mmol) in 10 mL of 7:3 dioxane: water. A 90:10 Z:E mixture of compound 27a was obtained (0.331 g, 76% yield). The spectral data were in agreement with those reported for this compound prepared via the fluoride based route.

Preparation of alkylidenephthalan 27e via the carbene complex route. General Procedure II was followed using 2-trimethylsilylethynylacetophenone23 (0.444 g, 1.70 mmol) and carbene complex 29 (0.638 g, 2.55 mmol) in 10 mL of 7:3 dioxane: water. A 95:5 Z:E mixture of compound 27e was obtained (0.196 g, 94% yield). The spectral data were in agreement with those reported for this compound prepared via the fluoride based route.

General Procedure III. Diels-Alder reactions. A solution of alkylidenephthalan (1 eq), if necessary dimethylacetylene dicarboxylate (DMAD) (5 eq), and acetic acid (0.05 mL) in toluene was heated at reflux for a 3h period. After the reaction mixture had cooled to room temperature, the solvent was removed on a rotary evaporator. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on triethylamine-treated silica gel24 using hexane: ethyl acetate mixtures as eluents.

Diels-Alder reaction of alkylidenephthalan amide and DMAD. General Procedure III was followed using alkylidenephthalan amide 27d (0.080 g, 0.394mmo1), DMAD (0.280 g, 1.97mmol), and acetic acid (0.05 mL) in toluene (4 mL). The elution solvent in the chromatography was 2:1 hexane: ethyl acetate. A colorless oil identified as Diels-Alder adduct 31d was obtained. (0.094 g, 69% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.39–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.08–6.97 (m, 2H), 5.88 (s, 1H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 3.70 (s, 3H), 3.55 (d, 1H, J = 15.8 Hz), 3.30 (d, 1H, J = 15.8 Hz), 3.03 (s, 3H), 2.92 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 168.1, 164.2, 162.1, 153.4, 147.6, 147.3, 146.5, 125.7, 125.6, 120.5, 120.4, 92.6, 76.6, 51.8, 37.3, 35.1, 31.7; IR (neat): 1717 (s), 1651 (s) cm−1; Mass Spec (EI): 346 (M+1, 8), 345 (M, 9), 314 (6), 301 (5), 286 (16), 254 (13), 131 (24), 72 (100); HRMS (EI): Calcd for C18H19NO6 345.12124, found 345.12249.

Tandem alkylidenephthalan formation and intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction. General Procedure I was followed using alkyne-ketone 26h (0.369 g, 1.04 mmol), potassium fluoride (0.301 g, 5.20 mmol) in methanol (10 mL). The crude product before chromatography (0.250 g, 100% yield) was sufficiently pure for use in for the subsequent Diels-Alder reaction. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.58 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.50–7.35 (m, 2H), 7.23 (td, 1H, J = 8.0, 1.4 Hz), 6.00 (dd, 1H, J = 17.5, 11.5 Hz), 5.82 (s, 1H), 5.54 (s, 2H), 4.96 (dd, 1H, J = 17.5, 1.0 Hz), 4.90 (d, 1H, J = 11.5, 1.0 Hz), 2.65 (s, 2H), 1.16 (s, 6H). General Procedure III was followed using crude alkylidenephthalan (0.250 g, 1.04 mmol) and glacial acetic acid (0.05 mL) in toluene (5 mL). The reflux was continued for 12 h. Final purification was achieved by flash chromatography on silica gel using 9:1 hexane: ethyl acetate as eluent to afford a single compound identified as naphthalene-ketone 33 (0.180 g, 78% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.86 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.84 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.80 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.60 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.56 (tt, 1H, J = 8.0, 1.6 Hz), 7.50 (tt, 1H, J = 8.0, 1.6 Hz), 3.98 (s, 2H), 2.69 (s, 2H), 1.43 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 209.6, 141.8, 132.5, 131.7, 128.7, 127.7, 127.4, 126.9, 125.8, 123.1, 123.0, 54.3, 41.1, 38.6, 30.3; IR (neat): 1715 cm−1; Mass Spec (EI): 224 (M, 85), 209 (55), 195 (35), 181 (100), 165 (55); HRMS: Calcd for C16H16O 224.12011, found 224.12038.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the MARC and SCORE programs of NIH.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material Available: General experimental, syntheses of compounds 26a-h from known or commercially available chemicals, and photocopies of proton and C-13 NMR spectra for compounds 27a-e, 27f-g, 31d, and 33.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.For a mechanistic discussion, see: Friedrichsen W. Structural Chem. 1999;10:47–52. and references therein. For a review of isobenzofuran chemistry, see: Friedrichsen W. Adv Heterocycl Chem. 1999;73:1–96.

- 2.Meegalla SK, Rodrigo R. J Org Chem. 1991;56:1882–1888. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meegalla SK, Rodrigo R. Synthesis. 1989:942–944. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bacchi A, Costa M, Della Ca N, Fabbricatore M, Fazio A, Gabriele B, Nasi C, Salerno G. Eur J Org Chem. 2004:574–585. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang D, Herndon JW. Org Lett. 2000;2:1267–1269. doi: 10.1021/ol005691i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For the latest example, see: Li R, Zhang L, Camacho-Davila A, Herndon JW. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:5117–5120.

- 7.For the lastest example using this reaction pathway, see: Camacho-Davila A, Herndon JW. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6682–6685. doi: 10.1021/jo061053n.

- 8.Zhang Y, Herndon JW. J Org Chem. 2002;67:4177–4185. doi: 10.1021/jo011136y. A note concerning this observation appears in the supplementary material.

- 9.In reference 2, the one example of a tandem isobenzofuran generation/intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction incorporating a carbonyl group in the tethering chain was not successful.

- 10.Berg TC, Bakken V, Gundersen LL, Petersen D. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:6121. [Google Scholar]

- 11.See the Supplementary Material for detailed synthetic procedures for preparation of the silylated alkynylbenzyl alcohol derivatives from known or commercially available substances.

- 12.Fürstner A, Szillat H, Stelzer F. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6785 – 6786. doi: 10.1021/ja0109343. See also reference 4.

- 13.Friebolin H. Basic One- and Two-Dimensional NMR Spectroscopy. 2. VCH: Weinheim; 1993. pp. 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a. Taskinen E, Mukkala VM. Tetrahedron. 1982;38:613–616. [Google Scholar]; b. Taskinen E. Acta Chim Scand B. 1985;B39:489–494. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pflieger D, Muckensturm B. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:2031–2040. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Zakrzewski VG, Montgomery JA, Stratmann RE, Burant JC, Dapprich S, Millam JM, Daniels AD, Kudin KN, Strain MC, Farkas O, Tomasi J, Barone V, Cossi M, Cammi R, Menucci B, Pomelli C, Adamo C, Clifford S, Ochterski J, Petersson GA, Ayala PY, Cui Q, Morokuma K, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Cioslowki J, Ortiz JV, Stefanov BB, Liu A, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Gomperts R, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Gonzalez M, Callacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson BG, Chen W, Wong MW, Andres JL, Head-Gordon M, Replogle ES, Pople JA, editors. The program Gaussian03 was employed. Gaussian, Inc; Pittsburgh, PA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selected examples of thermal 1,7-hydrogen shifts. Lian JJ, Lin CC, Chang HK, Chen PC, Liu RS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9661–9667. doi: 10.1021/ja061203b.Hess BA., Jr J Org Chem. 2001;66:5897–5900. doi: 10.1021/jo010622i.Baldwin JE, Reddy VP. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:8051–8056.Okamura WH, Hoeger KJ, Miller KJ, Reischl W. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:973–974.

- 18.Jung ME, Gervay J. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:224–232. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The drying process was accomplished by placing the dihydrate in a test tube and heating with a Bunsen burner.

- 20.Knepper K, Ziegert RE, Brase S. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:8591–8603. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegedus LS, McGuire MA, Schultze LM. Org Synth. 1987;65:140–145. or Coll. Vol. 8, pp 216–221.

- 22.This compound was prepared from Sonogashira coupling of trimethylsilylacetylene and 2-bromobenzaldehyde according to a literature procedure. Acheson RM, Lee GCM. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1987:2321–2332.

- 23.This compound was prepared from Sonogashira coupling of trimethylsilylacetylene and 2-iodoacetophenone according to a literature procedure. Maeyama K, Iwasawa N. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:1928–1929.

- 24.This process involves slurry-packing the column using a 99:1 hexane:triethylamine solution.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.