Abstract

Phytochemical-mediated modulation of p-glycoprotein (P-gp) and other drug transporters may give rise to many herb-drug interactions. Serial plasma concentration-time profiles of the P-gp substrate, digoxin, were used to determine whether supplementation with goldenseal or kava kava modified P-gp activity in vivo. Twenty healthy volunteers were randomly assigned to receive a standardized goldenseal (3210 mg daily) or kava kava (1227 mg daily) supplement for 14 days, followed by a 30-day washout period. Subjects were also randomized to receive rifampin (600 mg daily, 7 days) and clarithromycin (1000 mg daily, 7 days) as positive controls for P-gp induction and inhibition, respectively. Digoxin (Lanoxin®, 0.5 mg) was administered orally before and at the end of each supplementation and control period. Serial digoxin plasma concentrations were obtained over 24 hours and analyzed by chemiluminescent immunoassay. Comparisons of AUC(0–3), AUC(0–24), Cmax,, CL/F, and elimination half-life were used to assess the effects of goldenseal, kava kava, rifampin, and clarithromycin on digoxin pharmacokinetics. Rifampin produced significant reductions (p<0.01) in AUC(0–3), AUC(0–24), CL/F, T1/2, and Cmax, while clarithromycin increased these parameters significantly (p<0.01). With the exception of goldenseal’s effect on Cmax (14% increase), no statistically significant effects on digoxin pharmacokinetics were observed following supplementation with either goldenseal or kava kava. When compared to rifampin and clarithromycin, supplementation with these specific formulations of goldenseal or kava kava did not appear to affect digoxin pharmacokinetics, suggesting that these supplements are not potent modulators of P-gp in vivo.

Implementation of the 1994 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) sparked an upsurge in botanical supplement usage in the United States that continues to the present. Coincident with the influx of botanical supplements onto the marketplace are concerns regarding their interaction with conventional medications(Brazier and Levine, 2003). Herb-drug interactions may stem from the ability of various phytochemicals to modulate the activity of cytochrome P450 enzymes and/or drug transporters. The most noteworthy example to date is that of St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum). St. John’s wort reduces the effectiveness of many CYP3A4 and/or P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrates because one of its phytochemical components, hyperforin, is a potent ligand for the orphan nuclear receptor, PXR. Hyperforin-mediated activation of PXR upregulates both CYP3A4 and ABCB1, the respective genes for CYP3A4 and P-gp, leading to reduced bioavailability of many orally administered drugs(Dresser et al., 2003).

A number of in vitro studies suggest that botanical supplements other than St. John’s wort are capable of altering CYP activity(Foster et al., 2003; Strandell et al, 2004; Zou et al., 2002), yet results of human clinical studies have been less convincing. To date, only garlic oil(Gurley et al., 2002), goldenseal(Gurley et al., 2005), and possibly echinacea(Gorski et al., 2004) appear capable of significantly affecting human CYP activity in vivo. When compared to the number of reports addressing CYP-mediated herb-drug interactions, relatively few clinical studies have investigated the effects of botanical supplementation on P-gp substrate disposition. Those that have been conducted focus primarily on St. John’s wort and its effect on digoxin(Johne et al., 1999) or fexofenadine pharmacokinetics(Dresser et al., 2003). More recently the effects of hawthorn(Tankanow et al., 2003), milk thistle, and black cohosh(Gurley et al, 2006) on digoxin pharmacokinetics were tested, and found to be clinically insignificant. Due to the significant underreporting of drug interactions and adverse events associated with dietary supplements, more clinical studies are needed to better evaluate the interaction potential of botanical supplements with P-gp substrates.

Other popular botanicals that may pose a risk for P-gp-mediated herb-drug interactions include goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis) and kava kava (Piper methysticum). Goldenseal is a plant native to North America with a history of folk medicine use in the treatment of gastrointestinal disturbances, urinary disorders, hemorrhage, inflammation, and various infections. Often combined with echinacea, goldenseal-containing supplements currently rank among the top-selling botanicals in the United States. Recent in vitro studies have demonstrated that an isoquinoline alkaloid present in goldenseal, berberine, is a substrate for P-gp(Tsai and Tsai, 2004; Pan et al., 2002; Maeng et al., 2002) that exhibits disparate modulatory effects on P-gp-mediated drug efflux(Maeng et al., 2002; He and Liu, 2002; Efferth et al., 2002; Tsai et al., 2001; Lin et al, 1999a, 1999b). Kava kava has long been a traditional beverage consumed among South Pacific islanders to imbue psychotropic, hypnotic, and anxiolytic effects(Ulbricht et al, 2005). Since the 1990s, commercial kava extracts formulated as tablets and/or capsules have been marketed as dietary supplements for the alleviation of stress, anxiety, or insomnia(Ulbricht et al, 2005; Côté et al., 2004). The kavalactones (kavain, dihydrokavain, methysticin, dihydromethysticin, yangonin, desmethoxyyangonin), a collection of phytochemicals unique to kava, have also been shown to modulate P-gp activity in vitro(Weiss et al., 2005; Mathews et al, 2005).

In this report we describe, for the first time in humans, the effects of goldenseal and kava kava supplementation on the pharmacokinetics of digoxin, a putative P-gp substrate that does not undergo extensive presystemic metabolism and exhibits a narrow therapeutic index. In addition, we compare supplement effects to those of rifampin, an inducer of P-gp expression(Greiner et al., 1999), and clarithromycin, an inhibitor of P-gp activity(Rengelshausen, et al., 2003), as a means of gauging the clinical relevancy of supplement-mediated interactions.

Methods

Study subjects

This study protocol was approved by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Human Research Advisory Committee (Little Rock, AR) and all participants provided written informed consent before commencing the study. Twenty young adults (10 females) (age, mean ± SD = 27.3 ± 5.7 years; weight, 77.3 ± 17.7 kg) participated in the study and all subjects were in good health as indicated by medical history, routine physical examination, electrocardiography, and clinical laboratory testing. All subjects were nonsmokers, ate a normal diet, were not users of botanical dietary supplements, and were not taking prescription (including oral contraceptives) or nonprescription medications. All female subjects had a negative pregnancy test at baseline. All subjects were instructed to abstain from alcohol, caffeine, fruit juices, cruciferous vegetables, and charbroiled meat throughout each two-week phase of the study. Adherence to these restrictions was further emphasized five days before digoxin administration. Subjects were also instructed to refrain from taking prescription and nonprescription medications during supplementation periods, and any medication use during this time was documented. Documentation of compliance to these restrictions was achieved through the use of a food/medication diary.

Supplements and supplementation/medication regimens

The effect of goldenseal, kava kava, rifampin and clarithromycin on digoxin pharmacokinetics was evaluated individually on four separate occasions in each subject. This was an open-label study randomized for supplementation/medication sequence. (“Supplementation/medication” refers to either goldenseal, kava kava, rifampin, or clarithromycin.) Each supplementation phase (goldenseal or kava kava) lasted 14 days while each medication phase (rifampin or clarithromycin) was of 7 days duration. Each supplementation/medication phase was followed by a 30-day washout period. This randomly assigned sequence of supplementation/medication followed by washout was repeated until each subject had received all four products. Single lots of goldenseal (lot # OI10184) and kava kava (lot #A10062504) were purchased from Nautre’s Resource Products, (Mission Hills, CA) and Gaia Herbs, Inc. (Brevard, NC), respectively. (Both companies are recognized leaders in the botanical supplement industry for providing products of high quality and consistency.) Rifampin (Rifadin®, Aventis Pharmaceuticals, Kansas City, MO.) and clarithromycin (Biaxin®, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) were utilized as positive controls for P-gp induction and inhibition, respectively. Product labels were followed regarding the recommended dosing of goldenseal root extract (1,323 mg, three times daily, standardized to contain 24.1 mg isoquinoline alkaloids per capsule); kava kava rhizome extract (1,227 mg, three times daily, standardized to contain 75 mg kavalactones per capsule); rifampin (300 mg, twice daily); and clarithromycin (500 mg, twice daily). Telephone and electronic mail reminders were used to facilitate compliance, while pill counts and supplementation usage records, were used to verify compliance. Due to recent concerns regarding kava kava use and hepatotoxicity(Ulbricht et al, 2005), clinical liver function indicies (i.e. AST, ALT, GGT, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, and serum albumin) were monitored on days 0, 7, and 14 of both supplementation phases.

Digoxin administration

Following an overnight fast, subjects reported to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences General Clinical Research Center for digoxin administration and blood sampling. Prior to digoxin administration subjects were weighed and questioned about their adherence to the dietary and medication restrictions. Female subjects were administered pregnancy tests and only those with negative test results were allowed to participate. Following the placement of a 20 gauge indwelling catheter into a peripheral vein of the forearm, an oral dose of digoxin (0.5 mg, Lanoxin®, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC) was administered with 240 ml of water. Throughout the study, digoxin doses were administered 24 hours before the start of each supplementation/medication phase (baseline) and again on the last day of each phase. Serial blood samples were obtained before and at 0.33, 0.67, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours after digoxin administration. Each subject’s blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration rate was monitored at 1, 2, and 6 hours post digoxin administration. Four hours after digoxin administration, subjects received identical meals consisting of a turkey sandwich, potato chips, carrot sticks, and water.

Determination of digoxin serum concentrations

Digoxin serum concentrations were determined by an automated chemiluminescent immunoassay system (ACS:180 Digoxin, Chiron Diagnostics Corp., West Walpole, MA). Calibrations were performed in the range of 0.1–5.0 ng/mL. Serum concentrations greater than 5 ng/mL were diluted and reassayed. The lower limit of quantitation was 0.1 ng/mL. The interday accuracy for digoxin at 0.58, 1.77, and 3.48 ng/mL was 5.4, 3.7, and 2.9%, respectively. The interday precision for digoxin at 0.49, 0.98, and 1.97 ng/mL was 7%, 6%, and 2% respectively.

Supplement analysis

The phytochemical content of each supplement was independently analyzed for specific “marker compounds” by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Analytical standards of the isoquinoline alkaloids hydrastine and berberine as well as the kava lactones kavain, dihydrokavain, methysticin, dihydromethysticin, yangonin, and desmethoxyyangonin were purchased from ChromaDex, Inc. (Santa Ana, CA, USA). For goldenseal analyses, standard solutions of hydrastine and berberine were prepared in methanol:water (50:50, v/v) covering a range of 1–100 μg/mL and used for quantitative purposes. Isoquinoline alklaoid content of goldenseal was quantitated using a modification of a previously published HPLC method (Abourashed and Khan, 2001). Briefly, contents of twenty goldenseal capsules were weighed and placed in 100 mL volumetric flasks containing methanol:water (50:50, v/v). The contents of each vessel were agitated in an ultrasonication bath for 15 minutes. Aliquots of each sample were passed through a 0.45 μm PTFE syringe filter into HPLC autosampler vials. 20 μL were injected onto a Phenomenex Luna C18(2) column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5μm) (Phenomenex., Torrance, CA, USA) using a Thermo Separations Products component HPLC system (TSP, San Jose, CA, USA). Compounds of interest were eluted isocratically with a mobile phase of acetonitrile:0.1 M phosphate buffer (27:73, v/v) at a flow of 1.8 mL/min. Column effluent was monitored by ultraviolet absorbance detection at a wavelength of 235nm. Retention times for hydrastine and berberine were 3.3 and 5.7 minutes, respectively. The lower limit of quantitation for each analyte was 0.3 μg/mL. The interday accuracy and precision at 1, 10, and 50 μg/mL was < 3%.

Kava kava was analyzed for kavalactones using a modification of a reversed phase HPLC method described previously(Ganzera and Khan, 1999). Briefly, standard curves of individual kavalactones, each covering a range of 2–100 μg/mL, were prepared in acetonitrile. Six 100 mg samples of the proprietary kava extract were placed in 50 mL volumetric flasks and brought to volume with acetonitrile. Flasks were placed in an ultrasonic water bath for 60 minutes. 50 μL aliquots were filtered through a 0.45 μm PTFE syringe filter and placed in HPLC autosampler vials. Using a component Shimadzu HPLC system (Shimadzu Inc., Columbia, MD), 5 μL aliquots were injected onto an YMC J’sphere H80-ODS column (4.6 × 250 mm, 4 μm) (YMC Inc. Milford, MA) and kavalactones were eluted isocratically with a mobile phase of acetonitrile:2-propanol:0.1% phosphate buffer (20:16:64, v/v/v) at a flow of 1.0 mL/min and a column temperature of 40°C. Column effluent was monitored by ultraviolet absorbance detection at 246 nm. Retention times for methysticin, dihydromethysticin, kavain, dihydrokavain, yangonin, and desmethoxyyangonin were 13, 14, 17.3, 19, 19.9, and 21.8 minutes, respectively. Standard curves were linear over the range of 2 to 100 μg/mL (R2 > 0.999). Extraction recoveries exceeded 95% and relative standard deviations for interday accuracy and precision assessments were < 4%.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Digoxin pharmacokinetics were determined using standard noncompartmental methods with the computer program WinNonlin (version 2.1; Pharsight, Mountain View, CA). Area under the plasma concentration time curves from zero to 24 hours (AUC(0–24)) and zero to 3 hours (AUC(0–3)) were determined by use of the trapezoidal rule. Rifampin, clarithromycin, and other P-gp modulators have significant effects on digoxin pharmacokinetics during the absorption phase(Greiner et al., 1999; Rengelshausen et al., 2003), which was the reason for evaluating AUC(0–3). The terminal elimination rate constant (ke) was calculated using the slope of the log-linear regression of the terminal elimination phase. Area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from zero to infinity (AUC0–∞) was calculated using the log-linear trapezoidal rule up to the last measured time concentration (Clast) with extrapolation to infinity using Clast/ke. The elimination half-life was calculated as 0.693/ke. The apparent oral clearance of digoxin (Cl/F) was calculated as dose/AUC0–∞. Peak digoxin concentrations (Cmax) and the times when they occurred (Tmax) were derived directly from the data.

Disintegration tests

An absence of botanical-mediated effects on digoxin pharmacokinetics could stem from products exhibiting poor disintegration and/or dissolution characteristics. To address this concern, each product was subjected to disintegration testing as outlined in the United States Pharmacopeia 28(Annonymous, 2005). The disintegration apparatus consisted of a basket-rack assembly operated at 29–32 cycles per minute with 0.1 N HCl (37°C) as the immersion solution. One dosage unit (hard gelatin capsule) of each supplement was placed into each of the six basket assembly tubes. The time required for the complete disintegration of six dosage units was determined. This process was repeated with an additional six dosage units to assure accuracy. Since there are no specifications for the disintegration time of the botanical supplements used in this study, the mean of six individual dosage units was taken as the disintegration time for that particular product. A product was considered completely disintegrated if the entire residue passed through the mesh screen of the test apparatus, except for capsule shell fragments, or if the remaining soft mass exhibited no palpably firm core.

Statistical Analysis

A repeated measures ANOVA model was fit for each pharmacokinetic parameter using SAS Proc Mixed software (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, N.C., USA). Since pre-and post-supplementation/medication pharmacokinetic parameters were determined in each subject for all four study phases, a covariance structure existed for measurements within subjects. Sex, supplement/medication, and supplement/medication-by-sex terms were estimated for each parameter using a Huynh-Feldt covariance structure fit. If supplement/medication-by-sex interaction terms for a specific parameter measure were significant at the 5% level, the focus of the post-supplementation/medication minus pre-supplementation/medcation response was assessed according to sex. If the supplement/medication-by-sex interaction was not statistically significant, responses for both sexes were combined. Additionally, a power analysis was performed to estimate the ability to detect significant post- minus pre-supplementation/medication effects. All four models obtained at least 80% power at the 5% level of significance to detect a Cohen effect size of 1.32 to 1.71 standard deviation units(Cohen, 1988.)

RESULTS

All twenty subjects completed each phase of the study. Neither spontaneous reports from study participants or their responses to questions asked by study nurses regarding supplement/medication usage revealed any serious adverse events. Two subjects exhibited elevated levels of AST (174 IU/L and 183 IU/L; normal range 0–40 IU/L) and ALT (55 IU/L and 97 IU/L; normal range 0–40 IU/L) after 14 days of goldenseal supplementation. These values returned to normal within 7 days of stopping goldenseal. No other liver function indices (e.g. GGT, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, serum albumin) were affected by goldenseal. No subjects exhibited any changes in liver function tests while taking kava kava. Nausea, indigestion, and complaints of a metallic taste were frequently noted during clarithromycin phases. Mild indigestion and reddish discoloration of the urine were common conditions reported with rifampin use. No clinically significant changes in blood pressure, heart rate, or respiratory rate were observed after digoxin administration. Examination of pill counts and food/medication diaries revealed no significant deviations from the study protocol.

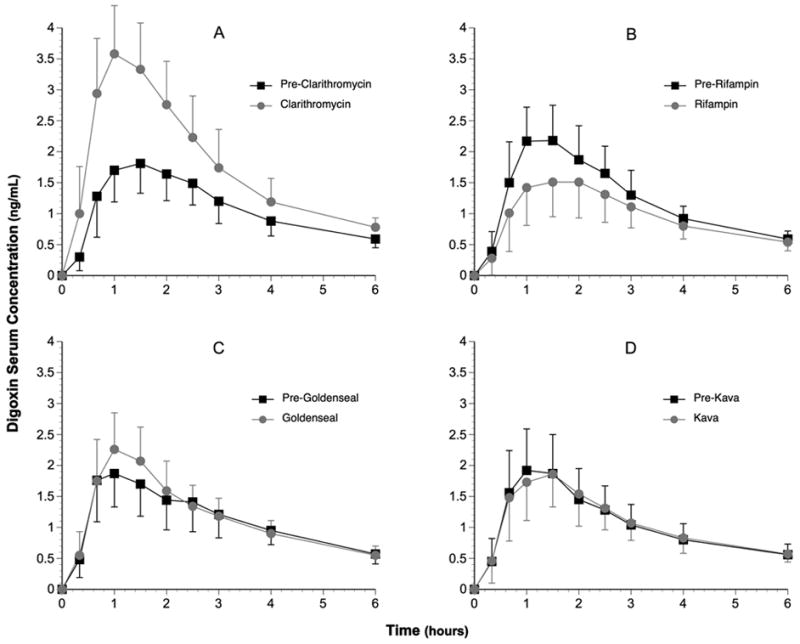

The effects of clarithromycin, rifampin, goldenseal, and kava kava on serum digoxin concentration versus time profiles are depicted in Figure 1. Statistically significant increases (p<0.001) in digoxin AUC(0–24) (57%), AUC(0–3) (83%), Cmax (95%) and elimination half-life (79%) were observed after 7 days of clarithromycin ingestion (Fig. 1; Table 1). Clarithromycin produced a 53% decrease in digoxin apparent oral clearance (Cl/F) (p<0.001) (Table 1). Statistically significant reductions (p<0.05) in digoxin AUC(0–24) (−16%), AUC(0–3)(−27%), and Cmax,(−28%) were noted following rifampin administration (Fig 1; Table 1). Rifampin increased the apparent oral clearance of digoxin by 33% and reduced digoxin elimination half-life by 16%. Apart from a 14% increase in digoxin Cmax following goldenseal, no other significant changes in digoxin pharmacokinetics were observed as a result of goldenseal or kava kava supplementation (Fig. 1; Table 1). Digoxin Tmax was not significantly affected by any of the treatments. In addition, no sex-related changes in digoxin pharmacokinetics were noted for any of the supplement/medication interventions.

Figure 1.

Digoxin concentration-time profiles (0–6 hours) before and after each supplementation/drug phase. (A) pre- and post-clarithromycin; (B) pre- and post-rifampin; (C) pre- and post-goldenseal; (D) pre and post-kava kava. Black squares = pre-experimental mean serum digoxin concentrations. Gray circles = post-experimental mean serum digoxin concentrations. Error bars = s.d.

Table 1.

Digoxin pharmacokinetic parameters before and after supplementation/drug phases (mean ± s.d.)

| Supplement/Drug Phase | AUC (0–3) (ng x hr/mL) |

AUC(0–24) (ng x hr/mL) |

Cl/F (L/hr) | T1/2 (hours) | Cmax (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Clarithromycin | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 14.1 ± 2.7 | 18.8 ± 6.7 | 32.1 ± 9.4 | 2.1 ± 0.5 |

| Post-Clarithromycin | 7.3 ± 1.8*** | 22.1 ± 4.5*** | 8.4 ± 2.7*** | 57.5 ± 20.4*** | 4.1 ± 1.1*** |

| Pre-Rifampin | 4.8 ± 1.4 | 15.0 ± 4.1 | 19.0 ± 8.4 | 33.2 ± 12.8 | 2.5 ± 0.9 |

| Post-Rifampin | 3.5 ± 1.1*** | 12.6 ± 3.6*** | 25.3 ± 12.9* | 27.9 ± 9.2* | 1.8 ± 0.5** |

| Pre-Goldenseal | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 13.8 ± 3.4 | 22.1 ± 9.4 | 29.9 ± 12.0 | 2.1 ± 0.7 |

| Post-Goldenseal | 4.5 ± 1.3 | 14.0 ± 3.5 | 20.7 ± 8.1 | 32.4 ± 13.0 | 2.4 ± 0.8* |

| Pre-Kava kava | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 13.2 ± 2.6 | 22.6 ± 8.9 | 28.6 ± 8.6 | 2.2 ± 0.6 |

| Post-Kava kava | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 13.4 ± 3.0 | 23.8 ± 8.9 | 28.6 ± 10.5 | 2.1 ± 0.7 |

AUC = area under the concentration-time curve, Cl/F = apparent oral clearance, T1/2 = elimination half-life, Cmax = maximum serum concentration,

= p < 0.05;

= p < 0.01;

= p < 0.001

Results of phytochemical analyses and disintegration testing for goldenseal and kava are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effect of ABCB1 haplotype on digoxin AUC and Cmax at baseline and after clarithromycin and rifampin (mean ± s.d.)

| Haplotype | AUC (0–3)base (ng/hr/mL) † | AUC(0–24)base (ng/hr/mL) † | Cmax (base) (ng/mL) † | ΔAUC (0–3)Clarith (ng/hr/mL)‡ | ΔAUC (0–3)Rif (ng/hr/mL)‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC-GC (n = 9) | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 14.8 ± 2.9 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 2.4 | Δ1.1 ± 0.8 |

| GC-TT (n = 6) | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 13.0 ± 3.0 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 1.5 | Δ1.4 ± 1.6 |

| GC-GT (n = 4) | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 14.5 ± 4.6 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 2.3 | Δ1.2 ± 0.3 |

| TT-TT (n = 1) | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 11.0 ± 1.1 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 3.2 | Δ1.6 |

AUC(0–3)base = area under the curve from 0–3 hours at baseline; AUC(0–24)base= area under the curve from 0–24 hours at baseline; Cmax (base) = maximum digoxin concentration at baseline; ΔAUC(0–3)Clarith = change in area under the curve from 0–3 hours after clarithromycin; ΔAUC(0–3)Rif = change in area under the curve from 0–3 hours after rifampin; n = number of subjects exhibiting haplotype; GC-GC = G/G2677-C/C3435 (reference haplotype); GC-TT = G/T2677-C/T3435; GC-GT = G/G2677-C/T3435; TT-TT = T/T2677-T/T3435.

= means determined from four separate baseline values for each subject.

= means based on single determination for each subject.

DISCUSSION

Considerable evidence points to the goldenseal alkaloid, berberine, and the kavalactones as being substrates for P-gp. Following oral administration in the rat, berberine undergoes hepatobiliary excretion, the magnitude of which is altered by P-gp inhibitors(Tsai and Tsai, 2004). Also, using a rat recirculating intestinal perfusion model and in vitro transport systems, berberine absorption was significantly improved in the presence of the P-gp inhibitors, cyclosporine and quinidine(Pan et al, 2002). Accordingly, some authors have proposed that P-gp-mediated intestinal efflux may explain berberine’s poor oral bioavailability(Sheng et al, 1993; Zeng and Zeng, 1999). Still other in vitro studies point to berberine as a weak to moderate inhibitor of various P-gp substrates (Tsai et al, 2001; He and Liu, 2002; Efferth et al, 2002). Conversely, berberine has also been shown to induce P-gp expression in various cell lines(Lin et al, 1999a, 1999b; Maeng et al, 2002).

Like berberine, studies investigating the effects of kavalactones on P-gp function in vitro have yielded mixed results. Using the P-gp-overexpressing murine leukemia cell line, P388/dx, Weiss et al demonstrated that individual kavalactones were moderately inhibitory toward the P-gp-mediated efflux of calcein-acetoxymethylester, whereas crude kava extracts appeared to be more potent inhibitors(Weiss et al., 2005). Of the individual kavalactones tested, desmethoxyyangonin was the most potent; however, it was 9 times less inhibitory than quinidine and 28.5 times less potent than verapamil. In contrast, studies utilizing a baculovirus expression system showed that human P-gp ATPase activity increased 2 fold following incubation with desmethoxyyangonin, but was unaffected by kava extract or other individual kava lactones(Matthews et al, 2005).

Despite ample evidence for goldenseal alkaloids and kavalactones as modifiers of P-gp activity in vitro, our findings suggest that the goldenseal and kava formulations investigated in this study were not potent modulators of human P-gp activity in vivo, and therefore do not pose a significant interaction risk with digoxin. This interpretation is supported by the significant changes in digoxin pharmacokinetics observed following the administration of clarithromycin, a known P-gp inhibitor, and rifampin, a recognized inducer of P-gp expression. The slight, albeit statistically significant, increase (14%) in digoxin Cmax by goldenseal could be interpreted as P-gp inhibition; however, when compared to clarithromycin’s effect on Cmax (+95%), this is not likely to be clinically significant.

Since plasma concentrations of berberine, hydrastine, and the kavalactones were not measured, their in vivo solubility and/or bioavailability status in this study remains unknown. To date, no assessment of the pharmacokinetics of goldenseal alkaloids, when administered as a dietary supplement, have been performed in humans. However, when congestive heart failure patients received 1.2 g/day of berberine hydrochloride orally for 14 days peak steady state plasma concentrations were less than 20 ng/mL(Zeng and Zeng, 1999), signifying poor bioavailability. Whether this is a function of inadequate dissolution, extensive drug efflux, extensive biotransformation, or a combination remains to be determined.

Little is known about kavalactone disposition in humans. Duffield et al noted that all seven major, and several minor kavalactones could be identified in the urine of male volunteers after ingesting a traditional aqueous extraction of kava(Duffield et al, 1989). The pharmacokinetic profile of kavain has also been studied in humans following its oral administration(Matthews et al, 2005). An 800 mg dose of racemic kavain produced free serum concentrations of 40 and 10 ng/mL at 1 and 4 hours, respectively. Higher concentrations of kavain metabolites, both free and conjugated, were noted in serum and urine indicative of significant biotransformation.

From the available data it appears that concentrations in excess of 10–30 μM of either goldenseal alkaloids or kavalactones are required to significantly modify P-gp activity in vitro. Clearly, plasma levels < 20 ng/mL are unlikely to cause significant modulation of the transporter in vivo. However, following oral application, the concentration of goldenseal alkaloids and kavalactones might be considerably higher in the gut wall. Assuming that the phytochemical contents determined for these two formulations (See Table 2) are consumed with a 240-mL volume of beverage, a rough estimation of the concentrations of goldenseal alkaloids and kavalactones, assuming complete dissolution, yields concentration ranges of 157–240μM and 132–417μM, respectively. From in vitro predictions, such concentrations should be sufficient to modulate P-gp activity within intestinal enterocytes. Our findings contradict these predictions and demonstrate that extrapolation of in vitro results to the in vivo situation remains speculative. Lack of correlation between in vitro and in vivo studies with botanical extracts is not unexpected given the myriad limitations recognized for in vitro models as predictors of drug interactions in vivo(von Moltke et al., 1998). Oftentimes, such discrepancies can be traced to basic pharmaceutics issues including inadequate dosage form disintegration and/or dissolution. In this study, however, both dosage forms disintegrated within 12 minutes or less leaving phytochemical solubility concerns and poor dissolution characteristics as more plausible rationales. Indeed berberine, hydrastine, and the kavalactones exhibit poor water solubility, a problem often addressed during in vitro studies through the addition of cosolvents like methanol or DMSO. Thus, it seems reasonable to suspect that while goldenseal alkaloids and kavalactones may be P-gp substrates, they either exhibit a weak affinity for the transporter, or concentrations achieved in vivo are insufficient to affect digoxin efflux.

Nevertheless, we recently reported that goldenseal supplementation inhibited human CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 activity in vivo while kava kava administration had no noticeable effect on these isoforms(Gurley et al, 2005). Evidently, the concentration of certain goldenseal components is sufficient to inactivate these enzymes in vivo. This inactivation by goldenseal likely stems from the formation of a stable heme adduct between the methylenedioxyphenyl moiety of berberine and hydrastine and the heme iron of the enzyme(Chatterjee and Fanklin, 2003). Interestingly, two kavalactones, methysticin and dihydromethysticin, are also substituted methylenedioxyphenyl compounds, yet they do not inhibit CYP3A4 or CYP2D6 in vivo.This may be the result of shorter, more flexible side chains attached to these methylenedioxyphenyl compounds since such substitutions are less inhibitory to CYP isoforms(Nakajima et al, 1999). Considerable overlap in the substrate selectivity, tissue localization, and coinducibility of CYP3A4 and P-gp, underscores the importance of assessing the effects of goldenseal and kava kava on human P-gp activity in vivo. The appropriateness of such an investigation was heightened by a recent report citing markedly elevated blood concentrations of cyclosporine (a CYP3A4 and P-gp substrate) in renal transplant recipients after berberine administration(Wu et al, 2005). In light of our current findings, it would appear that goldenseal’s mechanism for producing herb-drug interactions lies more with its ability to inhibit CYP isoforms than its effect on P-gp. Kava, on the other hand, appears to have little effect on either in vivo.

Product variability may also contribute to the observed discrepancies, not only with regard to vitro/in vivo comparisons, but among clinical studies as well. Commercially available goldenseal and kava formulations have been found to vary widely in their alkaloid content(Edwards and Draper, 2003; Ganzera and Khan, 1999; Côté et al, 2004). To date, no reports have examined the dissolution or phytochemical release characteristics of goldenseal or kava supplement formulations. Such information, especially that garnered from tests performed in simulated gastric or intestinal fluid, might be especially useful in explaining these inconsistencies.

Recent reports linking kava use to liver toxicity prompted its withdrawal in Europe, Australia, and Canada(Ulbricht et al, 2005). In the United States the FDA issued a warning to consumers alerting them to possible hepatotoxic side effects associated with kava supplementation(Ulbricht et al, 2005). We observed no clinical evidence of kava-related hepatoxicity; however, moderate elevations in serum AST and ALT were noted in two subjects during the 14-day goldenseal supplementation period. This observation brings into question the safety of chronic goldenseal supplementation.

In conclusion, when compared to rifampin and clarithromycin, the botanical supplements goldenseal and kava kava produced no significant changes in the disposition of digoxin, a clinically recognized P-gp substrate with a narrow therapeutic index. Accordingly, these supplements appear to pose no clinically significant risk for P-gp-mediated herb-drug interactions. However, given the inter-product variability in phytochemical content and potency among botanical supplements, these results may not extend to regimens utilizing higher dosages, longer supplementation periods, or products with improved dissolution and/or bioavailability characteristics.

Table 3.

Phytochemical analysis and disintegration times for botanical dosage forms.

| Supplement (dosage form) | Compound | Content (mg/capsule) | Daily Dose) (mg) | Disintegration Time (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goldenseal (hard gelatin capsule) | Isoquinoline alkaloids | 3.5 | ||

| Hydrastine | 22.0 | 132.0 | ||

| Berberine | 12.8 | 76.8 | ||

| Total | 34.8 | 208.8 | ||

| Kava kava (softgel capsule) | Kava lactones | 12.0 | ||

| Kavain | 23.1 | 69.3 | ||

| Dihydrokavain | 19.8 | 59.4 | ||

| Methysticin | 9.9 | 29.7 | ||

| Dihydromethysticin | 13.1 | 39.3 | ||

| Yangonin | 11.4 | 34.2 | ||

| Desmethoxyyangonin | 7.2 | 21.6 | ||

| Total | 84.5 | 253.5 |

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- AUC

area under the curve

- Cmax

maximum serum concentration

- CL/F

apparent oral clearance

- CYP2D6

cytochrome P-450 2D6

- CYP3A4

cytochrome P-450 3A4

- ke = elimination rate constant P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- Tmax

time of maximum serum concentration

- T1/2

elimination half-life

Footnotes

This work is supported by the NIH/NIGMS under grant RO1 GM71322 and by NIH/NCRR to the General Clinical Research Center of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences under grant M01 RR14288.

References

- Abourashed EA, Khan IA. High-performance liquid chromatography determination of hydrastine and berberine in dietary supplements containing goldenseal. J Pharm Sci. 2001;90:817–822. doi: 10.1002/jps.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Disintegration and dissolution of dietary supplements, in The Pharmacopeia of the United States Twenty-eighth Revision, and the National Formulary. 23. United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc; Rockville: 2005. pp. 2778–2779. [Google Scholar]

- Brazier NC, Levine MAH. Drug-herb interactions among commonly used conventional medicines: a compendium for health care professionals. Am J Ther. 2003;10:163–169. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee P, Franklin MR. Human cytochrome P450 inhibition and metabolic intermediate complex formation by goldenseal extract and its methylenedioxyphenyl components. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:1391–1397. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.11.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1988. pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Côté CS, Kor C, Cohen J, Auclair K. Composition and biological activity of traditional and commercial kava extracts. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2004;322:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresser GK, Schwartz UI, Wilkinson GR, Kim RB. Coordinate induction of both cytochrome P4503A and MDR1 by St. John’s wort in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;73:41–50. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2003.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffield AM, Jamieson DD, Lidgard RO, Duffield PH, Bourne DJ. Identification of some human urinary metabolites of the intoxicating beverage kava. J Chromatogr. 1989;475:273–281. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)89682-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dürr D, Stieger B, Kullak-Ublick GA, Rentsch KM, Steinert HC, Meier PJ, Fattinger K. St. John’s wort induces intestinal P-glycoprotein/MDR1 and intestinal and hepatic CYP3A4. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68:598–604. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.112240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DJ, Draper EJ. Variations in alkaloid content of herbal products containing goldenseal. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43:419–423. doi: 10.1331/154434503321831148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efferth T, Davey M, Olbrich A, Rucker G, Gebhart E, Davey R. Activity of drugs from traditional Chinese medicine toward sensitive and MDR1- or MRP1-overespressing multidrug-resistant human CCRF-CEM leukemia cells. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2002;28:160–168. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2002.0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster BC, Vandenhoek S, Hana J, Krantis A, Akhtar MH, Bryan M, Budzinski JW, Ramputh A, Arnason JT. In vitro inhibition of human cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of marker substrates by natural products. Phytomed. 2003;10:334–342. doi: 10.1078/094471103322004839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzera M, Khan IA. Analytical techniques for the determination of lactones in Piper methysticum Forst. Chromatographia. 1999;50:649–653. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski JC, Huang S-M, Pinto A, Hamman MA, Hilligoss JK, Zaheer NA, Desai M, Miller M, Hall SD. The effect of Echinacea (Echinacea purpurea root) on cytochrome P450 activity in vivo. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;75:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner B, Eichelbaum M, Fritz P, Kreichgauer H-P, von Richter O, Zundler J, Kroemer HK. The role of intestinal P-glycoprotein in the interaction of digoxin and rifampin. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:147–153. doi: 10.1172/JCI6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley BJ, Gardner SF, Hubbard MA, Williams DK, Gentry WB, Cui Y, Ang CYW. Cytochrome P450 phenotypic ratios for predicting herb-drug interactions in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:276–287. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.126913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley BJ, Gardner SF, Hubbard MA, Williams DK, Gentry WB, Khan IA, Shah A. In vivo effects of goldenseal, kava kava, black cohosh, and valerian on human cytochrome P450 1A2, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A4/5 phenotypes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley BJ, Barone GW, Williams DK, Carrier J, Breen P, Yates CR, Song P, Hubbard MA, Tong Y, Cheboyina S. Effect of milk thistle (Silybum marianum) and black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) supplementation on digoxin pharmacokinetics in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:69–74. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Liu G-Q. Effects of various principles from Chinese herbal medicine on rhodamine 123 accumulation in brain capillary endothelial cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2002;23:591–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johne A, Brockmoller J, Bauer S, Maurer A, Langheinrich M, Roots I. Pharmacokinetic interaction of digoxin with an herbal extract from St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) . Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;66:338–345. doi: 10.1053/cp.1999.v66.a101944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H-L, Liu T-Y, Wu C-W, Chi C-W. Berberine modulates expression of mdr1 gene product and the responses of digestive track cancer cells to paclitaxel. Br J Cancer. 1999a;81:416–422. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H-L, Liu T-Y, Wu C-W, Chi C-W. Up-regulation of multidrug resistance transporter expression by berberine in human and murine hepatoma cells. Cancer. 1999b;85:1937–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeng H-J, Yoo H-J, Kim I-W, Song I-S, Chung S-J, Shim C-K. P-glycoprotein-mediated transport of berberine across Caco-2 cell monolayers. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91:2614–2621. doi: 10.1002/jps.10268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JM, Etheridge AS, Valentine JL, Black SR, Coleman DP, Patel P, So J, Burka LT. Pharmacokinetics and disposition of the kavalactone kawain: interaction with kava extract and kavalactones in vivo and in vitro. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1555–1563. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.004317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Suzuki M, Yamaji R, Takashina H, Shimada N, Yamazaki H, Yoko T. Isoform selective inhibition and inactivation of human cytochrome P450s by methylenedioxyphenyl compounds. Xenobiotica. 1999;29:1191–1202. doi: 10.1080/004982599237877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G-Y, Wang G-J, Liu X-D, Fawcett JP, Xie Y-Y. The involvement of P-glycoprotein in berberine absorption. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;91:193–197. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.t01-1-910403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rengelshausen J, Goggelmann C, Burhenne J, Riedel K-D, Ludwig J, Weiss J, Mikus G, Walter-Sack I, Haefeli WE. Contribution of increased oral bioavailability and reduced nonglomerular renal clearance of digoxin to the digoxin-clarithromycin interaction. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;56:32–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng MP, Su Q, Wang H. Studies on the intravenous pharmacokinetics and oral absorption of berberine HCL in beagle dogs. Sin Pharmacol Bull. 1993;9:64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Song P, Shen L, Meibohm B, Gaber AO, Honaker MR, Kotb M, Yates CR. Detection of MDR1 single nucleotide polymorphisms C3435T and G2677T using real-time polymerase chain reaction: MDR1 single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping assay. AAPS PharmSci. 2002;4(4) doi: 10.1208/ps040429. article 29 ( http://www.aapspharmsci.org) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandell J, Neil A, Carlin G. An approach to the in vitro evaluation of potential for cytochrome P450 enzyme inhibition from herbals and other natural remedies. Phytomed. 2004;11:98–104. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tankanow R, Tamer HR, Streetman DS, Smith SG, Welton JL, Annesley T, Aaronson KD, Bleske BE. Interaction study between digoxin and a preparation of hawthorn (Crataegus oxyacantha) J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43:637–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai P-L, Tsai T-H. Hepatobiliary excretion of berberine. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:405–412. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai T-H, Lee C-H, Yeh P-H. Effect of P-glycoprotein modulators on the pharmacokinetics of camptothecin using microdialysis. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:1245–1252. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ, Schmider J, Wright CE, Harmatz JS, Shader RI. In vitro approaches to predicting drug interactions in vivo. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbricht C, Basch E, Boon H, Ernst E, Hammerness P, Sollars D, Tsourounis C. Safety review of kava (Piper methysticum) by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4:779–794. doi: 10.1517/14740338.4.4.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J, Sauer A, Frank A, Unger M. Extracts and kavalactones of Piper methysticum G. Forst (kava-kava) inhibit P-glycoprotein in vitro. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1580–1583. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Li Q, Xin H, Yu A, Zhong M. Effects of berberine on the blood concentration of cyclosporine A in renal transplanted recipients: clinical and pharmacokinetic study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:567–572. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0952-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Zeng X. Relationship between the clinical effects of berberine on severe congestive heart failure and its concentration in plasma studied by HPLC. Biomed Chromatogr. 1999;13:442–444. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0801(199911)13:7<442::AID-BMC908>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L, Harkey MR, Henderson GL. Effects of herbal components on cDNA-expressed cytochrome P450 enzyme catalytic activity. Life Sci. 2002;71:1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01913-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]