Abstract

The role of estrogen (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR) in breast cancer is well established. Identification of the second human estrogen receptor, the estrogen receptor β (ERβ), prompted us to evaluate its role in breast cancer. We studied the expression of ERβ by immunohistochemistry and mRNA in situ hybridization in 92 primary breast cancers and studied its association with ERα, PR, and various other clinicopathological factors. Sixty percent of tumors were defined as ERβ-positive (nuclear staining in >20% of the cancer cells). Normal ductal epithelium and 5 of 7 intraductal cancers were also found to express ERβ. Three-fourths of the ERα- and PR-positive tumors were positive for ERβ, whereas ERα and PR were positive in 87% and 67% of ERβ-positive tumors, respectively. ERβ was associated with negative axillary node status (P < 0.0001), low grade (P = 0.0003), low S-phase fraction (P = 0.0003), and premenopausal status (P = 0.04). In conclusion, the coexpression of ERβ with ERα and PR as well as its association with the other indicators of low biological aggressiveness of breast cancer suggest that ERβ-positive tumors are likely to respond to hormonal therapy. The independent predictive value of ERβ remains to be established.

Positive estrogen receptor (ER) status is a well established predictor of response to endocrine therapy in breast cancer. Addition of progesterone receptor (PR) measurements improves the predictive value further by defining the ER-positive/PR-negative tumor type, which is less likely to respond to therapy than tumors that are positive for both receptors. 1-3 In addition to the ability to predict the response to hormonal therapy, ER and PR also reflect the differentiation of the tumor, thereby aiding assessment of patient prognosis. 1-3 ER and PR assays have been routinely used in the selection of appropriate therapy for breast cancer patients for more than 20 years. 1-3

It is well known that up to 30 to 40% of breast tumors with positive hormone receptor status do not respond to endocrine therapy. 1 Reasons for the lack of response have remained poorly understood, although steroid-independent growth factor signaling (eg, via HER-2/neu), 4 functionally deficient splicing variants of the ER gene, 2 and heterogeneity of ER expression 5 may partly explain poor therapy outcome of ER-positive tumors. However, these mechanisms explain only a fraction of the hormone receptor-positive tumors that do not respond to endocrine therapy. Therefore, the search for alternative explanations continues.

The recent discovery of a second estrogen receptor, termed ERβ, 6,7 indicates that the mechanism of action of estrogens is far more complex than anticipated. Due to its recent discovery, relatively little is known about the ERβ at the moment. 7 Human ERβ has a structure highly homologous to the previously known human ER, now termed ERα. 8,9 Estrogens are known to bind ERβ with affinity similar to ERα 7 and the transcriptional activation via the estrogen response element (ERE) is identical for both receptor forms. 6,8,10 ERα and ERβ can also form biologically functional receptor heterodimers in the tissues in which they are coexpressed. 11-13 So far, only limited data are available on the activity and expression of ERβ in human neoplasms. Pilot studies have indicated that ERβ is expressed in breast cancer as its mRNA has been detected in breast carcinoma samples by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). 14-17 However, due to the small numbers of tumors studied, the role of ERβ has remained obscure. 14-17 Here we studied the expression of ERβ by immunohistochemistry and mRNA in situ hybridization in a set of unselected breast tumors. Expression of ERβ was correlated with ERα, PR, and known clinicopathological indicators of malignant potential to clarify the role of ERβ in the pathobiology of breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Tumors

We studied surgical biopsy specimens from a set of 92 female breast cancer patients whose tumor samples were sent for hormone receptor analysis to the Laboratory of Cancer Biology at Tampere University Hospital. The tumor material consisted of 79 invasive ductal carcinomas, 6 lobular, and 7 intraductal carcinomas, according to the WHO tumor classification. The median age of the patients was 58 years (range, 35–88). Patients were operated with segmental resection or mastectomy and had not received any preoperative chemo- or endocrine therapy. Tumor samples were snap-frozen in OCT tissue embedding medium (Tissue-Tek, Miles Inc., Naperville, IL) within 20 minutes of removal during surgery. Cryostat sections (5–7 μm) were cut for intraoperative diagnosis, hormone receptor analysis, and DNA flow cytometry. Extra sections were stored air-tight at −70°C until used in immunohistochemistry and mRNA in situ hybridization of ERβ. All histopathological diagnoses were re-evaluated and histopathological grading was performed according to the Bloom and Richardson system. 18

Immunohistochemistry

The frozen sections were fixed with Zamboni’s fluid for 15 minutes. Nonspecific antibody binding was blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 1.0% bovine serum albumin and 1.0% nonfat milk powder for 10 minutes at room temperature. ERβ was detected with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (PAI-313, Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO; dilution 5 μg/ml). The antigen used for immunization is a KLH-conjugated synthetic peptide corresponding to the C-terminal amino acid residues 467 to 485 of human ERβ. According to the manufacturer, the antibody reacts with human ERβ and displays no cross-reactivity with human ERα expressed in a baculovirus system. The primary antibody was incubated overnight at 4°C using Shandon Sequenza immunostaining coverplates (Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA). A streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex technique was used for visualization with diaminobenzidine as a chromogen (Histostain Plus kit, Zymed Inc., South San Francisco, CA). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Immunostainings were evaluated by light microscopy using a 25× objective by a researcher unaware of immunohistochemical or clinical data. The immunohistochemical controls included omission of primary and secondary antibodies, and a pre-absorption experiment, where the antibody was incubated with the concentration of 10 times excess of the peptide immunogen (PAI-313p, Affinity Bioreagents) for 1 hour at room temperature before applying to slides. Adjacent sections from the same tumors were immunostained normally for comparison.

ERα and PR were immunostained on adjacent Zamboni-fixed frozen sections using the ER-ICA and PR-ICA kits (Abbott Laboratories, Naperville, IL). Overexpression of c-erbB2 oncoprotein was detected by the monoclonal antibody CB-11 (Novocastra Laboratories, Newcastle, UK). Details of the ERα, PR, and c-erbB2 staining method have been shown in our previous studies. 19 DNA flow cytometry was performed using adjacent frozen sections 200 μm thick as starting materials, as previously described. 20

mRNA in Situ Hybridization

mRNA in situ hybridization was carried out as previously described. 6,19 Four different synthetic antisense oligonucleotide probes directed against ERβ mRNA (nucleotides 542–589, 1089–1136, 1326–1373, and 1384–1431) were labeled to specific activity of 1 × 10 9 cpm/mg at the 3′ end with 33P-dATP (DuPont-New England Nuclear Research Products, Boston, MA) using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK). A cocktail of similarly labeled irrelevant oligonucleotides was used as control. The hybridization was carried out by incubating unfixed and air-dried frozen sections in humidified boxes at 42°C for 18 hours with 5 ng/ml of the labeled probe in the hybridization mixture. The sections were then washed four times (15 minutes each) in 1× SSC at 55°C. In the final rinse, the sections were left to cool to room temperature (approximately 1 hour). The sections were dipped in Kodak NTB2 nuclear track emulsion and exposed for 90 days at 4°C. The sections were stained with cresyl violet and analyzed under bright-field and epipolarization conditions in a Nikon Microphot-FX microscope. Alternatively, autoradiograph films (Amersham β-max; Amersham) were overlaid on slides, exposed for 30 to 60 days, and developed using LX24 developer and AL4 fixative (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Irrelevant control probes of the same length, with similar GC content and specific activity, were used to ascertain the specificity of the hybridizations. Addition of 100 times excess of the unlabeled probe abolished all hybridization signals (data not shown).

Results

Expression of ERβ in Ductal Epithelium and in Breast Cancer

Immunohistochemical staining using the polyclonal ERβ antibody showed strong nuclear immunoreaction and weak cytoplasmic and extracellular background staining (Figure 1) ▶ . Positive immunostaining was confined to the nuclei of carcinoma cells, whereas the stromal and inflammatory cells in the tumor stained always stained negative. When 20% of positively stained carcinoma cells was used as a cutoff point to classify tumors as ERβ-positive, 55 of 92 (59.8%) tumors were defined as ERβ-positive. The specificity of ERβ immunohistochemistry was confirmed by mRNA in situ hybridization (Figure 1) ▶ . Positive autoradiographic signals indicating presence of ERβ mRNA were obtained from immunohistochemically ERβ-positive tumors (Figure 2) ▶ . ERβ mRNA and immunoreactivity were found also in the normal ductal epithelium and immunoreactivity in intraductal carcinoma (Figures 1 and 2) ▶ ▶ . Immunostaining of ERβ was confirmed by pre-absorbing ERβ antibody with immunogen peptide (Figure 1) ▶ . Incubation of the ERβ antibody with the peptide abolished the nuclear immunoreaction completely from adjacent sections.

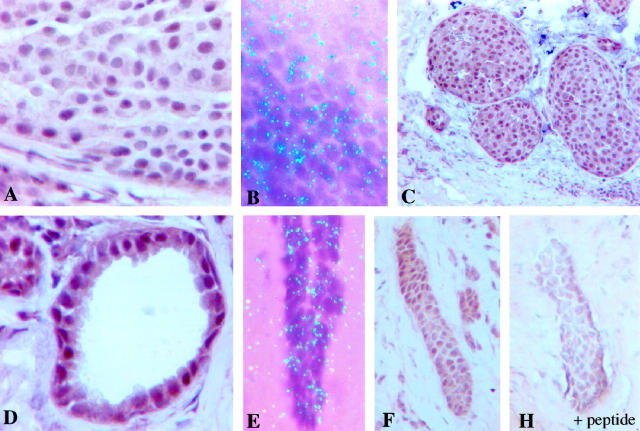

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical demonstration of ERβ in human breast cancer by immunohistochemistry (A) and mRNA in situ hybridization (B). ERβ is expressed also in intraductal carcinoma (C), and in normal ductal epithelium (D). The expression of ERβ in normal ducts was confirmed by mRNA in situ hybridization (E). F and H demonstrate the specificity control of the immunostaining. Adjacent tumor sections were immunostained with or without pre-absorption of the ERβ antibody by the immunogen peptide. The nuclear immunoreaction is completely abolished after pre-absorption.

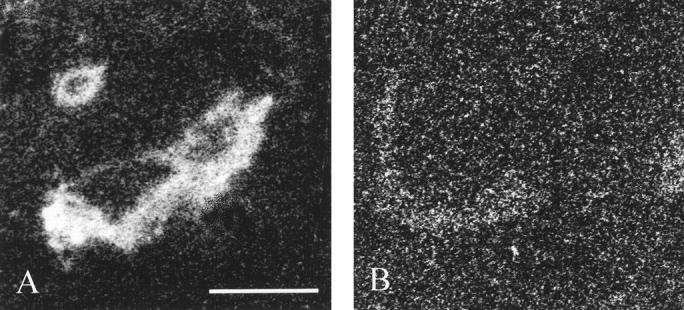

Figure 2.

Localization of ERβ mRNA by in situ hybiridization using a sensitive X-ray film autoradiography detection. A demonstrates hybridization of an immunohistochemically ERβ-positive tumor with a cocktail of five ERβ antisense oligonucleotides. The tumor area and a normal duct (upper left corner) are labeled, whereas no specific labeling can be seen with a cocktail of irrelevant oligonucleotides (B). Bar, 0.4 mm.

Association of ERβ with ERα and PR

Three-fourths of the ERα-positive tumors (76%, 48/63) were positive for ERβ, whereas 7 of 29 (24%) ERα-negative tumors expressed ERβ (Table 1) ▶ . A similar strong association was identified between ERβ and PR status (Table 1) ▶ . Seventy-six percent of the PR-positive tumors were ERβ-positive (37/49), whereas 42% of the PR-negative breast tumors were ERβ-positive (18/43). When ERα and PR status were combined, 77% of ERα-positive/PR-positive tumors were found to be ERβ-positive, while almost as high precentage of the ERβ-positivity was identified in ERα+/PR- tumors (75%, Table 1 ▶ ). Although a majority of ERα-positive/PR-negative tumors (12/16) were positive for ERβ, only 22% of the tumors that were negative for both ERα and PR were positive for ERβ (Table 1) ▶ . Patterns of ERα and ERβ coexpression are illustrated in Figure 3 ▶ .

Table 1.

Association of ERβ with ERα, PR, and Receptor Status in 92 Breast Cancers

| ERβ-negative (%) | ERβ-positive (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERα | |||

| Negative | 22 (24) | 7 (8) | |

| Positive | 15 (16) | 48 (52) | <0.0001 |

| PR | |||

| Negative | 25 (27) | 18 (20) | |

| Positive | 12 (13) | 37 (40) | 0.0014 |

| ERα/PR status | |||

| ERα−/PR− | 21 (23) | 6 (7) | |

| ERα−/PR+ | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| ERα+/PR− | 4 (4) | 12 (13) | |

| ERα+/PR+ | 11 (12) | 36 (39) |

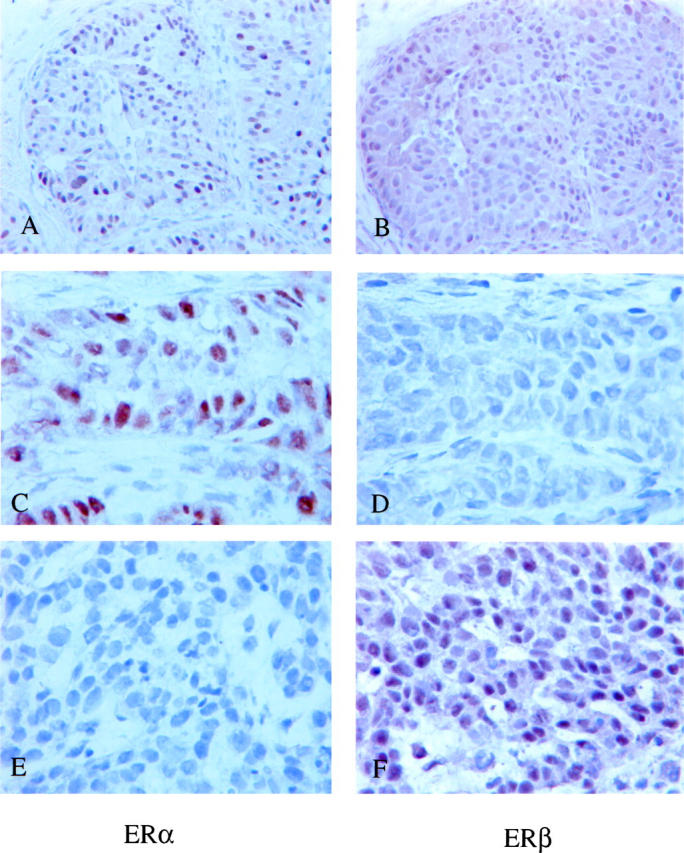

Figure 3.

Patterns of ERα and ERβ coexpression in breast cancer. A and B demonstrate a tumor expressing both ERα and ERβ. A tumor expressing ERα but not ERβ is shown in C and D, and a tumor expressing ERβ but not ERα in E and F, respectively. All stainings were done from adjacent frozen sections. Counterstained with hematoxylin.

Association of ERβ with Clinicopathological Features

Expression of ERβ was significantly associated with several clinicopathological features of breast cancer. Positive ERβ status was more common in axillary node-negative than in node-positive tumors (P < 0.0001, Table 2 ▶ ), but no correlation was found with the size of the primary tumor (Table 2) ▶ . Expression of ERβ was more common in pre- and perimenopausal than postmenopausal patients (P = 0.04). There was no association between the histological type of the tumor and the ERβ expression, in that 46/79 invasive ductal carcinomas, 4/6 invasive lobular, and 5/7 intraductal carcinomas showed positive ERβ immunostaining. ERβ had strong association with histological grade (P = 0.0003), and ERβ-positive tumors were also characterized by diploid DNA content and lower S-phase fractions than ERβ-negative tumors (P = 0.03 and P = 0.002, respectively; Table 2 ▶ ). A nearly significant association was found between negative ERβ status and overexpression of ErbB-2 oncoprotein (P < 0.08, Table 2 ▶ ). For comparison, association of ERα with clinicopathological features was also determined. Similarly to ERβ, there was a correlation between the ERα and histological grade, DNA ploidy, S-phase fraction, ErbB-2 oncoprotein overexpression, and tumor size (Table 2) ▶ . No significant association was found between ERα and menopausal and nodal status of the tumor.

Table 2.

Association of ERβ with Various Clinicopathological Factors in 92 Breast Cancers

| ERβ-negative (%) | ERβ-positive (%) | Odds ratio (95% c.i.) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All tumors | 37 (40) | 55 (60) | ||

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≤2 cm | 12 (28) | 31 (72) | ||

| >2 cm | 18 (47) | 20 (53) | 0.43 (0.17–1.1) | 0.11 (0.0057) |

| Axillary node status | ||||

| Negative | 18 (27) | 48 (73) | ||

| Positive | 19 (73) | 7 (27) | 0.14 (0.05–0.48) | 0.0001 (0.08) |

| Histologic grade | ||||

| I | 6 (24) | 19 (76) | ||

| II | 14 (36) | 25 (64) | 0.0003 (<0.0001) | |

| III | 13 (87) | 2 (13) | ||

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Premenopausal | 7 (24) | 22 (76) | ||

| Postmenopausal | 30 (48) | 33 (52) | 0.35 (0.13–0.94) | 0.04 (0.99) |

| ErbB2 overexpression | ||||

| No | 25 (35) | 46 (65) | ||

| Yes | 12 (57) | 9 (43) | 0.41 (0.15–1.1) | 0.08 (0.03) |

| DNA ploidy | ||||

| Diploid | 11 (28) | 29 (72) | ||

| Nondiploid | 26 (50) | 26 (50) | 0.38 (0.16–0.92) | 0.03 (0.04) |

| S-phase fraction | ||||

| Below median† | 9 (22) | 32 (78) | ||

| Above median | 22 (56) | 17 (44) | 0.22 (0.08–0.58) | 0.002 (0.0006) |

*Fischer’s exact test (two-tailed). The P value for a similar association with ERα is shown in parentheses.

†Median = 8%.

Discussion

Our results indicate that ERβ is often coexpressed with ERα and PR in breast cancer. So far, the expression of ERβ has been studied by RT-PCR and only in a small number of breast carcinomas. 14-18 These two factors may relate to the difficulty of standardizing the results obtained by RT-PCR to detect ERβ transcript. 14-18 As the current hormone receptor status (ERα and PR) is currently recommended to be analyzed by immunohistochemistry, 21 we used it also to detect ERβ in frozen sections of breast cancer samples. Our attempts with paraffin-embedded material were unsuccessful despite the use of several different antigen retrieval methods as well as their modifications. The staining on frozen sections was found to be specific, according to the confirmatory mRNA in situ hybridizations and immunohistochemical pre-absorption experiments.

Our study revealed that both ER receptors, α and β, are expressed in morphologically normal ductal epithelium, indicating that ERβ is likely to have a function in the normal mammary gland. More importantly, coexpression of ERα and ERβ was retained in a majority of breast cancers, suggesting that ERβ may be an equal target with ERα for hormone therapy. In this context, it is known that ERβ is equivalent to ERα in its binding affinity for natural estrogens as well for anti-estrogens. 7 ERα and -β can both activate gene transcription by binding either to the classical estrogen response elements (EREs) or the AP1 enhancer elements. 7,10,22 Anti-estrogens prevent gene transactivation via ERα through both EREs and AP1 elements. 10 Unlike ERα, the anti-estrogen-ERβ -complex inhibits gene transcription when bound to ERE, but works as an agonist when bound to AP1 elements. 10 It is, therefore, possible that anti-estrogens could have also agonistic effects in ERβ-positive breast tumors, which could decrease the effect of the hormone therapy. An alternative possibility is that ERα and -β are expressed in the form of the heterodimers. 11-13,22 As ERα and ERβ were coexpressed in most breast tumors, the heterodimers may also have a significant role in breast cancer. However, the presence and significance of ERα and ERβ heterodimers in breast cancer remains to be established.

Comparison of the ERα and ERβ expression with PR status may also shed light on the roles of ERα and ERβ in breast cancer. Transcription of the PR gene is enhanced and maintained by estrogens; thus, a positive PR status has long been regarded as a marker of a functional ER pathway. PR was positive in a majority of ERα-positive/ERβ-negative tumors (11/15, 73%), similarly to the situation in the ERα-positive/ERβ-positive tumors (36/48, 75%). The semiquantitative PR histoscores were not different in these groups (data not shown). Thus, ERβ does not seem to be an important factor defining the expression of PR in the breast cancer. This may indicate indirectly that ERβ has a smaller role in defining the responsiveness to hormonal therapy in breast tumors. From the therapeutic point of view, the most interesting receptor combination explaining the lack of response to hormone therapy in hormone-positive breast tumors is ERα-positive/ERβ-negative/PR-positive. In other words, it will be important to know whether lack of ERβ in ERα-positive/PR-positive tumors may lower the likelihood for response to anti-estrogen therapy. In our material ERβ was negative in 23% of the ERα-positive/PR-positive tumors, which is close to the proportion of ER-positive/PR-positive tumors that are known to respond poorly to tamoxifen. The predictive value of ERβ remains to established in forthcoming studies.

The correlation of ERβ with various clinicopathological factors revealed that ERβ is expressed predominantly in the well-differentiated, diploid, and slowly proliferating breast cancers. The correlations were similar to those obtained for ERα. These results indicate that the expression of both ERα and -β are lost in an identical manner during dedifferentiation of the tumor cells. However, two interesting differences were found in the clinicopathological associations of ERα and ERβ. First, ERβ was tightly associated with axillary lymph node status, whereas a less strong association was identified for ERα. This suggests that the loss of ERβ expression might be an indicator of a tumor phenotype with high metastatic potential. From the endocrinological point of view, it is worth noting that expression of ERβ was significantly more common in pre- and perimenopausal than in postmenopausal patients. This association usually goes in the opposite direction for ERα; in other words, ERα status is more often positive in postmenopausal patients. It is therefore possible that circulating estrogens favor ERβ as their primary target at the expense of ERα in premenopausal patients. After menopause the situation may then change. Obviously the endocrinological aspects of ERα/ERβ expression in breast cancer need to be studied with larger arrays of patient material, taking into account the use of oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, and the possible anti-estrogen therapy (for previous breast cancer).

In conclusion, we have shown that normal ductal epithelium and a majority of breast cancers express the second human receptor for estrogens, the ERβ. The ERβ-positive breast cancers tumors are predominantly ERα- and PR-positive, node-negative, well differentiated and slowly proliferating. The coexpression of ERβ with ERα and PR as well as its association with indicators of low biological aggressiveness suggest that ERβ-positive tumors are likely to respond to hormonal therapy. The independent predictive value of ERβ remains to be established.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. Sari Toivola and Mrs. Anne Luuri for skillful technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Prof. Jorma Isola, University of Tampere, Institute of Medical Technology, P.O. Box 607, FIN-33101 Tampere, Finland. E-mail: bljois@uta.fi.

Supported by the Tampere University Hospital Research Foundation, Pirkanmaa and Finnish Cultural Foundations, Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Farmos Research Foundation, and the Finnish Cancer Society (to T. J. and J. I.).

References

- 1.Locker GY: Hormonal therapy of breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 1998, 24:221-240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fugua SAW: Estrogen and progesterone receptors and breast cancer. Harris JR Lippman ME Morrow M Hellman S eds. Diseases of the Breast. 1996, :pp 261-270 Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allred DC, Harvey JM, Berardo M, Clark GM: Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Mod Pathol 1998, 11:155-168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross JS, Fletcher JA: HER-2/neu (c-erb-B2) gene and protein in breast cancer. Am J Clin Pathol 1999, 112:S53-S67 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuukasjärvi T, Kononen J, Helin H, Isola J: Loss of estrogen receptor in recurrent breast cancer is associated with poor response to endocrine therapy. J Clin Oncol 1996, 14:2584-2589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuiper GGJM, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J-Å: Cloning a novel estrogen receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:5925–5930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Enmark E, Gustafsson J-Å: Estrogen receptor β: a novel receptor opens up new possibilities for cancer diagnosis and treatment. Endocr Rel Cancer 1998, 5:213–222

- 8.Mosselman S, Pohlman J, Dijkema R: ERβ: identification and characterisation of a novel human estrogen receptor. FEBS Lett 1996, 392:49-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Grandien K, Fried G, Lagerkrantz S, Lagerkranzt J, Nordenskjöld M, Gustafsson J-Å: Human estrogen receptor β: gene structure, chromosomal localisation and expression pattern. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997, 82:4258–4265 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Paech K, Webb P, Kuiper GG, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J, Kushner PJ, Scanlan TS: Differential ligand activation of estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ at AP1 sites. Science 1997, 277:1508-1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowley SM, Hoare S, Mosselman S, Parker MG: Estrogen receptors α and β form heterodimers on DNA. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:19858-19862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pace P, Taylor J, Suntharalingam S, Coombes RC, Ali S: Human estrogen receptor β binds DNA in a manner similar to and dimerizes with estrogen receptor α. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:25832-25838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pettersson K, Grandien K, Kuiper GG, Gustafsson JA: Mouse estrogen receptor β forms estrogen response element-binding heterodimers with estrogen receptor α. Mol Endocrinol 1997, 11:1486-1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dotzlaw H, Leygue E, Watson PH, Murphy LC: Expression of estrogen receptor-β in human breast tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997, 82:2371-2374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vladusic EA, Hornby AE, Guerra-Vladusic FK, Lupu R: Expression of estrogen receptor β messenger RNA variant in breast cancer. Cancer Res 1998, 58:210-214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Speirs V, Parkes AT, Kerin MJ, Walton DS, Carleton PJ, Fox JN, Atkin SL: Coexpression of estrogen receptor α and β: poor prognostic factors in human breast cancer? Cancer Res 1999, 59:525-528 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dotzlaw H, Leygue E, Watson PH, Murphy LC: Estrogen receptor-β messenger RNA expression in human breast tumor biopsies: relationship to steroid receptor status and regulation by progestins. Cancer Res 1999, 59:529-532 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloom HJG, Richardson WW: Histological grading and prognosis in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1957, 11:359-377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Järvinen TAH, Kononen J, Pelto-Huikko M, Isola J: Expression of topoisomerase IIα is associated with rapid cell proliferation, aneuploidy, and c-erbB-2 overexpression in breast cancer. Am J Pathol 1996, 148:2073-2082 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kallioniemi O-P: Comparison of fresh and paraffin-embedded tissue as starting material for DNA flow cytometry and evaluation of intratumor heterogeneity. Cytometry 1988, 9:164-169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvey JM, Clark GM, Osborne CK, Allred DC: Estrogen receptor status by immunohistochemistry is superior to the ligand-binding assay for predicting response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999, 17:1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paige LA, Christensen DJ, Gron H, Norris JD, Gottlin EB, Padilla KM, Chang CY, Ballas LM, Hamilton PT, McDonnell DP, Fowlkes DM: Estrogen receptor (ER) modulators each induce distinct conformational changes in ER α and ER β. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:3999-4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]