Abstract

Studies with I125-labeled low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) have shown the presence of high-affinity LDL receptors on insulin-producing β cells but not on neighboring α cells. By using gold-labeled lipoproteins, we demonstrate receptor-mediated endocytosis of LDLs and very low-density lipoproteins in rat and human β cells. Specific for human β cells is the fusion of LDL-containing endocytotic vesicles with lipid-storing vesicles (LSVs; diameter, 0.6–3.6 μm), which are absent in rodent β cells. LSVs also occur in human pancreatic α and duct cells, but these sequester little gold-labeled LDL. In humans <25 years old, LSVs occupy 1% of the cytoplasmic surface area in β, α, and duct cells. In humans >50 years old, LSV surface area in β cells (11 ± 2% of cytoplasmic surface area) is fourfold higher than in α and duct cells and 10-fold higher than in β cells at younger ages (P < 0.001); the mean LSV diameter in these β cells (1.8 ± 0.04 μm) is larger than at younger ages (1.1 ± 0.2 μm; P < 0.005). Oil red O staining on pancreatic sections confirms that neutral lipids accumulate in β cells of older donors. We conclude that human β cells can incorporate LDL and very low-density lipoprotein material in LSVs. The marked increase in the LSV area of aging human β cells raises the question whether it is caused by prolonged exposure to high lipoprotein levels such as occurs in Western populations and whether it is causally related to the higher risk for type 2 diabetes with aging.

Type 2 diabetes is frequent in several aging populations. 1 A diagnosis of type 2 diabetes indicates that the pancreatic β cells are no longer capable of meeting metabolic demands for insulin. Nutritional factors in Western life style can contribute to this development by increasing the need for insulin and/or by reducing the functional reserve of the β cells. Fat consumption is an established risk factor. 2,3 Elevated fatty acid levels are responsible for reduced peripheral sensitivity to insulin. 4-6 They can also lead to reduced capacity of the β cells to maintain an adequate hyperinsulinemia in this condition. 7 Studies in diabetes-prone rodents have demonstrated that prolonged elevation of fatty acids can cause β-cell dysfunctions, as well as β-cell death by apoptosis. 8,9 The higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes in societies with a high fat intake also raises the question whether low-density lipoproteins (LDL) and very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) exert any direct effects on the pancreatic β cells. We therefore investigated the interactions of LDL and VLDL with normal β cells. It was first shown that both rat and human β cells express high-affinity LDL receptors that also bind VLDL and can internalize both lipoproteins. 10 In this study, we demonstrate that this internalization contributes to the marked lipid accumulation that is noticed in β cells of aging individuals.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Islet Cells

Adult male Wistar rats were housed according to the guidelines of the Belgian Regulations for Animal Care. The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experiments of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Rats were sedated and killed with CO2 followed by decapitation. Islets were isolated by collagenase digestion and dissociated in a calcium-free medium containing trypsin and DNase (both from Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). 11 Purified β and non-β cells were obtained by autofluorescence-activated cell sorting as described previously. 11 Cells were cultured in Ham’s-F10 medium supplemented with 2 mmol/L l-glutamine, 50 μmol/L 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 0.075 g/L penicillin, 0.1 g/L streptomycin, 10 mmol/L glucose, and 5 g/L charcoal-treated bovine serum albumin (fraction V, radioimmunoassay grade; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO).

Human islets were isolated from donor pancreas procured by European hospitals affiliated with Eurotransplant-Bioimplant Services (Leiden, The Netherlands) and β Cell Transplant, a multicenter program on islet cell transplantation in diabetes. 12 Islets were prepared in the central unit, Medical Campus, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Brussels, Belgium) using collagenase digestion and Ficoll gradient purification. The islet-enriched gradient interface was harvested, washed, and cultured in Ham’s-F10 medium supplemented as previously described. 13 After culture, the human islet cell preparations consisted of 55 to 65% β cells, 6 to 12% α cells, and 20 to 30% nongranulated cells, which have been identified as duct cells. 12,13 The cultured preparations were dissociated by the same trypsin treatment as described for rat islets.

Rat and human islet cell preparations were cultured for 48 hours in polylysine-coated (1 μg/ml, Sigma) wells (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at a density of 10 5 cells/ml before exposure to gold-labeled lipoproteins.

Preparation of LDL

Human lipoproteins were prepared from serum of healthy volunteers after an overnight fast. The VLDL and LDL fractions were isolated by ultracentrifugation, 14 with one additional run for LDL. The electrophoretic mobility of LDL on 75% agarose exhibited an Rf of 0.24 ± 0.02 SEM (n = 7). All lipoprotein preparations were filtered through a 22-μm filter (Millipore, Molsheim, France) before use. Their protein concentration was determined with the Pierce BCA kit using bovine serum albumin as standard. Colloidal gold particles were conjugated to LDL by electrostatic surface adsorption of their negative charge. This was accomplished by rapid mixing of 1 ml of colloidal gold (20-nm particle size, British BioCell International, Cardiff, UK) per 100 μl of LDL (concentration, 100–150 μg LDL-protein/ml). 15 Conjugates were examined by negative-stain electron microscopy before use. A similar procedure was used for preparing gold-labeled VLDL.

Incubation of Cells with Lipoproteins

Experiments with gold-labeled LDL or VLDL were carried out at 4°C for studies on binding and at 37°C for studies on uptake. After incubation, cells were fixed in cacodylate-buffered glutaraldehyde (4.5%, pH 7.3), postfixed in osmium tetroxide (1%), and embedded in Spurr’s resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranylacetate and lead citrate and examined in a Zeiss EM 109 electron microscope.

Ultrastructural localization of acid phosphatase was performed using a modified Gomori reaction. 16 After incubation with the gold-labeled lipoprotein and short fixation of the cells, the reaction medium, containing 0.067 mol/L Tris-maleate, 0.36% β-glycerophosphate, and 0.11% lead nitrate, was added. After a 1-hour incubation at 37°C, cells were prepared for routine transmission electron microscopy, omitting the final uranylacetate-lead citrate staining step.

Characterization of Lipid-Storing Vesicles in Human β Cells

Morphometric analysis was conducted to determine the individual diameters and surface areas of vesicles containing large (diameter > 0.6 μm) electron-lucent droplets and a peripheral rim of electron-dense material. Isolated islet tissue was examined from donors of different ages. The surface area of these vesicles was expressed as total per cell and as percentage of cellular cytoplasmic surface area (CSA). For each donor preparation, we performed measurements in 20 to 50 cells per cell type and averaged them to one value per cell type. We then averaged these values per donor age group, choosing arbitrarily a young (<25 years) and an old (>50 years) age group. The results are expressed as means ± SEM. The statistical significance of differences was calculated by unpaired Student’s t-test, assuming equal variances.

Staining for Lipids in Intact Pancreatic Tissue

Pancreatic tissue was examined for the presence of neutral lipids by an oil red O reaction on frozen material. The sections were first briefly immersed in 60% isopropanol, then incubated at room temperature for 1 hour in an oil red O solution, 17 briefly discriminated in 60% isopropanol, and finally rinsed with water. The oil red O reaction was followed by hematoxylin staining. Consecutive sections were stained for insulin to localize the neutral lipids versus the endocrine tissue. Tissue was fixed for 10 minutes in 4% formaldehyde prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated for 15 minutes in 90% methanol–10% H2O2, washed again with PBS, and incubated for 30 minutes with 10% normal goat serum. The insulin antibody 11 was then applied at a final concentration of 1:5000 for an overnight incubation at 4°C. After washing with PBS, the biotinylated anti-guinea pig antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was added at a concentration of 1:1000 for a 30-minute incubation at room temperature. Positivity was visualized after reaction with diaminobenzidine. Insulin staining was also followed by a standard hematoxylin staining.

Results

Binding and Uptake of Gold-Labeled LDL by Rat β Cells

Incubation of rat β cells with gold-labeled LDL at 4°C for 2 hours resulted in an association of gold particles with the plasma membrane but not with the intracellular compartment. Single as well as clustered particles occurred along both coated and noncoated regions of the membrane and, occasionally, in coated pits. No membrane-associated particles were noticed when incubation was carried out in calcium-free medium or when unconjugated colloidal gold was used. Membrane binding of gold-LDL was also negligible in the presence of excess unlabeled LDL and was markedly lower after 24 hours of preincubation with 100 to 400 μg/ml LDL at 37°C. No membrane binding was seen in islet endocrine non-β cells that were incubated in parallel, not even after 4 hours.

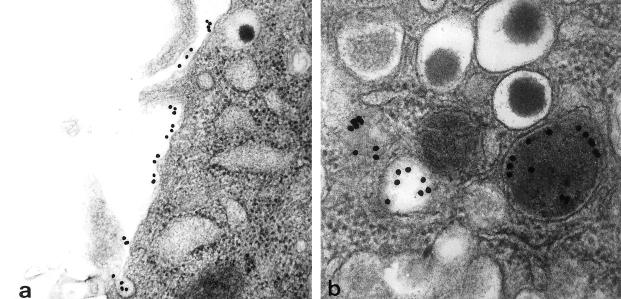

Incubation at 37°C resulted in a time-dependent increase in the number of intracellular gold particles. After 5 minutes, particles were still associated with the plasma membrane, but, compared with 4°C incubations, a larger proportion occurred in coated pits and coated vesicles (Figure 1a) ▶ . From 10 minutes on, increasing proportions of particles were found in uncoated vesicles, first as a rim at the inner vesicle membrane and, later on, dissociated from the membrane. The vesicles containing gold particles varied in size and in electron-lucent or electron-dense content (Figure 1b) ▶ . Some vesicles exhibited a positivity for acid phosphatase. The diameter of vesicles containing gold-labeled LDL was always smaller than 0.6 μm.

Figure 1.

Binding and uptake of gold-labeled LDL by purified rat β cells. a: After 5 minutes gold particles occur along the cell membrane and in coated pits (original magnification, ×30,000). b: After 3 hours of incubation, gold particles are found in electron-lucent and in electron-dense vesicles; these vesicles are smaller than 0.6 μm (original magnification, ×85,000).

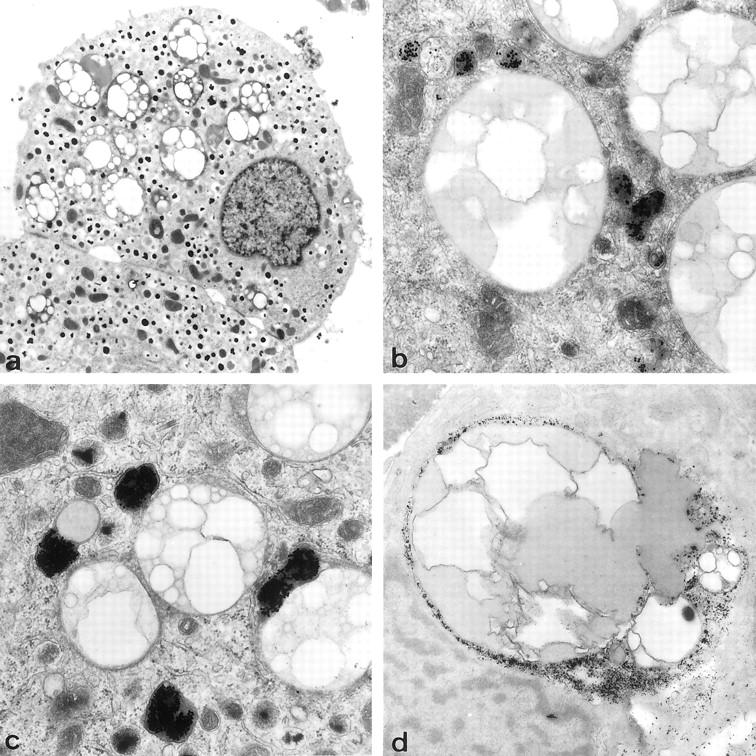

Binding and Uptake of Gold-Labeled Lipoproteins by Human β Cells

Incubation of human β cell preparations with gold-labeled LDL led to the same observations as with rat β cells, namely, association of gold particles with the plasma membrane at 4°C and their uptake in coated and uncoated vesicles at 37°C. After 3 to 6 hours, gold-containing vesicles appeared in the vicinity of larger (diameter > 0.6 μm) vesicles that contained both electron-lucent and electron-dense material, the latter often forming a peripheral rim under the vesicle membrane or delineating several spherical electron-lucent compartments within the same vesicle (Figure 2, a and b) ▶ . With longer incubation periods, gold-containing vesicles were found to fuse with these large vesicles (Figure 2c) ▶ . After incorporation, gold particles were mainly present in the peripheral rim of electron-dense material (Figure 2c) ▶ . At higher magnifications, this gold-containing dense material at the periphery was dispersed between two membranes, the outer one surrounding the large vesicle and the inner one surrounding an intravesicular compartment with mostly electron-lucent material (Figure 3) ▶ . Gold particles remained sequestered in these large vesicles during subsequent culture for 7 days. A similar uptake and fusion process was noticed with gold-labeled VLDL. Incubation with free gold particles did not result in their uptake and sequestration by the β cells. In non-β cells, only little uptake of gold-labeled LDL or VLDL was seen. The presence of rod-shaped granules in secretory vesicles 18 allows the identification of β cells from other endocrine islet cells, even when their relative proportion is decreased as a result of culture.

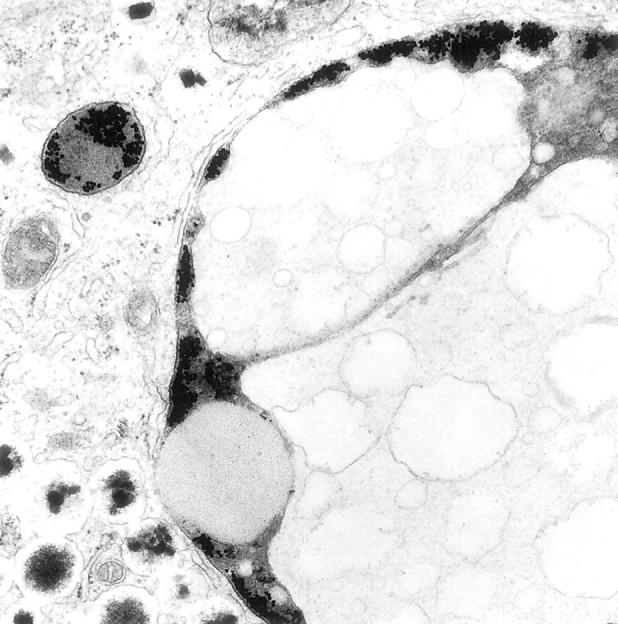

Figure 2.

Electron micrographs of β cells from a 52-year-old donor. a: Presence of large (1.1–2.6 μm diameter) lipid vesicles with electron-lucent and electron-dense content (original magnification, ×2700). b: After 3 hours of incubation with gold-labeled LDL at 37°C, gold-containing vesicles are found in the proximity of these lipid vesicles (original magnification, ×20,000). c: Fusion of both vesicles with localization of gold particles under the membrane of the lipid-containing vesicles (original magnification, ×20,000). d: Gomori reaction results in lead precipitation in the peripheral rim of some lipid vesicles, indicating acid phosphatase activity (original magnification, ×12,000).

Figure 3.

Electron micrograph of large LSV in human β cell that was exposed to gold-labeled LDL. Gold particles are sequestered in the peripheral electron-dense rim of the vesicle, between the outer membrane and the membrane that delineates electron-lucent material. Original magnification, ×32,000.

The large vesicles with which gold-containing vesicles can fuse are apparently filled with lipids because fixation without osmium caused large electron-lucent compartments; after fixation with osmium, they did not present a dense granulation or finger-print structures, suggesting absence of peroxidized lipofuscin. In some of them, the peripheral rim yielded a positive Gomori reaction, indicating the presence of acid phosphatase activity (Figure 2d) ▶ . The diameter of these membrane-bound vesicles varied widely, from 0.6 to 3.6 μm. Smaller lipid accumulations were occasionally found in the cytoplasm, closely associated with endoplasmic reticulum. These lipid accumulations in vesicles or cytoplasm were not detected in β cells isolated and/or cultured from adult (10-week-old) rats or mice (data not shown).

Age-Dependent Accumulation of Lipid-Storing Vesicles in Human β Cells

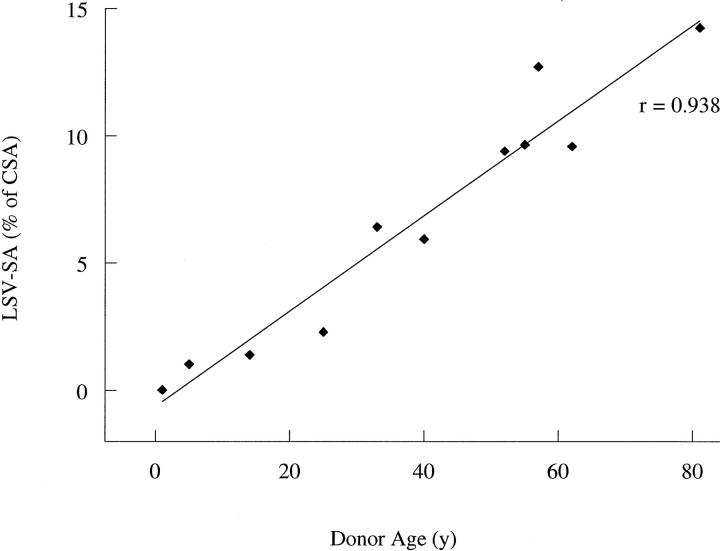

Electron microscopy of intact human pancreatic tissue demonstrated the presence of the same lipid-containing vesicles in the β cells, indicating that they were not formed as an artifact during the isolation or culture procedure. On routine examination of isolated human islets, we noticed that their abundance markedly increased with the age of the donor (Table 1) ▶ . No correlation was found with donor sex or body mass index. When the surface area of the lipid-storing vesicles (LSVs) was plotted against the age of the donors, a positive correlation was detected (Figure 4 ▶ ; r = 0.938; P < 0.001). We then arbitrarily selected the age limits for comparing morphometric parameters in young (<25 years) and older (>50 years) donors. In the donors of the younger age categories, LSV surface area occupied 0.9 ± 0.5 μm 2 per β cell, which corresponds to 1.2% of CSA (Table 2) ▶ . These absolute and relative surface areas were comparable to those measured in α cells and in nongranulated cells of the same preparations (Table 2) ▶ . In β cells from donors of the older age category (>50 years), LSV surface area was more than 10-fold higher (11.9 ± 1.2 μm2/β cell; P < 0.001), corresponding now to 11.1% of CSA (P < 0.001). Higher surface areas were also measured in α cells and in nongranulated cells from the older donors, but they remained, in both absolute and relative terms, 4- to 10-fold smaller than in the β cells (Table 2) ▶ . In β cells from the older donors, the mean diameter of these vesicles was larger than in β cells from the younger donors (1.8 ± 0.04 versus 1.1 ± 0.2 μm; P < 0.005). In view of their ultrastructural characteristics, these vesicles were denoted as lipid-storing vesicles.

Table 1.

Correlation Between Surface Area of LSVs and Clinical Characteristics of Donors

| Donor age (years) | Cause of death | Sex | Body mass index (kg/m2) | LSV-SA in β cells (% of CSA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Meningitis | M | 18.1 | 0.03 |

| 5 | Brain trauma | M | 20.7 | 1.03 |

| 14 | Brain trauma | M | 23.4 | 1.40 |

| 25 | Brain trauma | M | 21.9 | 2.29 |

| 33 | Brain trauma | M | 24.7 | 6.42 |

| 40 | Stroke | M | 24.6 | 5.94 |

| 52 | Stroke | F | 24.8 | 9.40 |

| 55 | Stroke | M | 23.5 | 9.65 |

| 57 | Brain hemorrhage | F | 22.5 | 12.72 |

| 62 | Brain hemorrhage | M | 26.1 | 9.58 |

| 81 | Brain hemorrhage | F | 23.0 | 14.24 |

Mean LSV surface area (LSV-SA) in β cells expressed as percentage of cytoplasmic surface area (CSA); none of the donors presented a history of diabetes mellitus or drug treatment for a particular disease. M, male; F, female.

Figure 4.

Correlation between donor age and the mean surface area of LSVs, expressed as percentage of the β cell CSA. By linear regression, a correlation coefficient r of 0.938 was calculated (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Surface Area of LSVs in Human Pancreatic Cells

| Donor age (years) | Cell type | Surface area per cell | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vesicles with lipid inclusions | Cytoplasm | |||

| Total (μm2) | % of cytoplasmic surface area | Total (μm2) | ||

| <25 | β | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 79 ± 5 |

| α | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 61 ± 7* | |

| Nongranulated | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 42 ± 7* | |

| >50 | β | 11.9 ± 1.2† | 11.1 ± 1.6† | 107 ± 14‡ |

| α | 2.3 ± 0.5*† | 2.8 ± 0.8*‡ | 83 ± 10‡ | |

| Nongranulated | 1.6 ± 0.4*‡ | 2.6 ± 0.6*† | 51 ± 5* |

Data are means ± SEM of measurements in islet tissue isolated from four donors younger than 25 years (body mass index, 18.1–23.4) and five donors older than 50 years (body mass index, 22.5–26.1). Statistical significance of differences is calculated by unpaired Student’s t test assuming equal variances: P for comparison with same cell type of donors <25 years old: †, P < 0.005; ‡, P < 0.05; P for comparison with β cells in same age category: *, P < 0.005.

In the older donors, the α and β cells exhibited larger CSAs than in donors younger than 25 years (P < 0.05; Table 2 ▶ ). In β cells, the increase (28 ± 10 μm2/cell) is 40% attributable to the increase in LSV area (increase of 11 ± 0.9 μm2/cell; Table 2 ▶ ). This is not the case in α cells, in which the increase in LSV surface area is marginal (1.9 ± 0.4 μm2/cell) to the increase in CSA (22 ± 8 μm2/cell). Higher age was not associated with a larger CSA in nongranulated cells (P > 0.05).

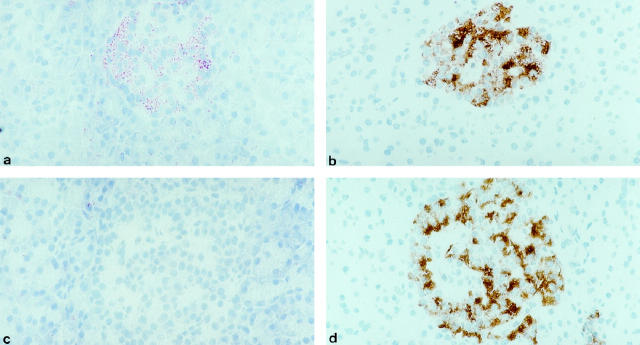

Lipid Accumulation in Pancreatic Islets from Older Donors

In cryostat sections of frozen pancreatic tissue, a positive oil red O staining was observed in the islets, as indicated by its colocalization with the insulin-positive regions (Figure 5, a and b) ▶ . This staining pattern was found in all sections from donors older than 50 years, but was absent in tissue from donors younger than 25 years (Figure 5, c and d) ▶ . No oil red O staining was noticed in rat or mouse pancreatic tissue, regardless of age (data not shown). When the oil red O staining was performed on human tissue that was embedded in paraffin before sectioning, no positive reaction was obtained, indicating that its positivity in frozen tissue was not caused by the presence of lipofuscin. 19

Figure 5.

Oil red O staining on pancreatic tissue from a donor aged 67 years (a) and a donor aged 6 years (c). Consecutive sections were stained for insulin (b, d). a: Presence of an oil red O-positive cell group, which is insulin-positive on a consecutive section (b). c: Absence of oil red O positivity in a 6-year-old donor, with insulin-positive cells shown in d. Original magnification, ×145.

Discussion

LDLs have been previously found to be taken up by pancreatic β cells but not by their neighboring α cells. 10 We have now used gold-labeled LDL to monitor the intracellular track of LDLs in rat and human β cells. This technique confirmed the presence of LDL-binding sites on the plasma membrane of β cells, with characteristics that were similar to those observed in the binding studies with I125-labeled LDL. Previous data characterized these sites as high-affinity receptors for LDL and VLDL but not for acetylated LDL. 10 Half-maximal binding was reached at 10 to 15 μg LDL/ml, a concentration that is comparable to the estimated interstitial LDL levels in the rat but is fivefold lower than those levels in humans with Western life styles. 20 In this latter condition, LDL receptors on β cells are thus expected to be down-regulated and saturated, mediating a steady uptake of LDL and VLDL. Uptake of LDL by β cells was first noticed during binding studies with I125-LDL. 10 It is now documented ultrastructurally as a receptor-mediated endocytosis, occurring in both rat and human β cells but negligible in α cells. From 30 minutes on, some of the gold-LDL-containing vesicles were positive for acid phosphatase, suggesting fusion of endocytotic vesicles with lysosomes. This process has been described for other cell types, 21 in which the lysosomes have been found to degrade the lipoprotein. 22

In human β cells, gold-LDL–containing vesicles were found to fuse with large (diameter >0.6 μm) lipid-containing vesicles. These large vesicles were not found in rat or mouse β cells. Their ultrastructure does not resemble the cytoplasmic triglyceride accumulations that have been described in steatosis, 19 nor do they present the features of lipofuscin accumulations. 19 They contain several electron-lucent compartments, often surrounded by a membrane, as well as electron-dense material, often forming a peripheral rim under the outer vesicle membrane. This peripheral rim sometimes exhibits a positivity for acid phosphatase, suggesting prior fusion with lysosomes. Because human β cells also presented smaller cytoplasmic lipid accumulations (data not shown), it is conceivable that the endoplasmic reticulum first envelops this cytoplasmic material and that this storage vesicle then fuses with lysosomes. A process of receptor-mediated endocytosis could deliver lipoproteins to this vesicle via secondary lysosomes. Accumulation of lipid-containing vesicles in human β cells could be the result of a prolonged imbalance between lipid uptake, processing, and consumption. To which extent inappropriate uptake of VLDL and LDL is responsible for the development and/or increase of this subcellular compartment is not known. However, the marked postnatal increase in human LDL levels 20 to concentrations that continuously saturate the LDL receptors in β cells makes lipoproteins candidate contributors to this process.

LSVs were not only noticed in human β cells, but also in adjacent α and duct cells. In donors under the age of 25 years, they occupied 1% of the CSA in each of these pancreatic cell types. In donors older than 50 years, their surface area was larger, reaching 2 to 3% of the CSA in α and duct cells and 11% in β cells. Increasing age thus causes lipid accumulation in β cells. It is conceivable that this process involves receptor-mediated uptake of LDL and VLDL and therefore is less pronounced in the adjacent non-β cells. Further work is needed to clarify the underlying mechanisms. This study strongly suggests that LSVs appear after birth. In our 1-year-old donor, only 7% of the β cells exhibited LSVs, with a mean diameter of 0.7 ± 0.3 μm. With increasing age, more β cells were found to contain LSVs, and the mean LSV diameter increased to 1.8 ± 0.04 μm in donors older than 50 years. As discussed earlier, these LSVs can incorporate LDL and VLDL that is taken up by receptor-mediated endocytosis. They might accumulate lipids if their clearance is saturated, as is conceivable with the high lipoprotein levels in Western society. Furthermore, β cells have a long life span, which gives them the time to accumulate products that are inappropriately cleared. Such a process is not necessarily specific for β cells. LDL receptors indeed occur in many other cell types, but a lower rate of uptake, a higher lipoprotein clearance, and/or a shorter cellular life span might result in absent or less pronounced accumulation of LSVs in a number of cell types.

That fat can accumulate in human islet tissue was already reported by Weichselbaum and Stangl at the beginning of this century. 23 This finding was even considered to be a characteristic of diabetes because diabetic patients showed more fat in the islets of Langerhans than age-matched nondiabetic controls. 23 In a subsequent paper, Weichselbaum described a vacuolization of the islets in 53% of diabetic patients. 24 Later reviews have questioned the specificity and frequency of this tissue alteration 25 and even warned that postmortem autolysis may be confused with the vacuolization. 26 These studies have not, however, always distinguished between fatty infiltration in islet tissue and fat accumulation in the endocrine islet cells. This work demonstrates that increasing age is associated with an accumulation of neutral lipids in human β cells but not in the surrounding exocrine cells. Analysis of the LSV content is now needed to directly demonstrate its lipid nature and identify the components. The scarcity of isolated human islet tissue will certainly be an obstacle for such subcellular fractionation and chemical characterization, but should be undertaken before speculations are made on the possible significance of these accumulations. We do not yet know whether they influence the functions of human β cells and their ability to respond to metabolic needs. Intracellular accumulation of lipids could chronically expose the β cells to elevated levels of free fatty acids, which, according to the lipotoxicity concept, 27 can impair the cellular responsiveness to secretory stimuli and even cause cell death. 9 Such a mechanism has been proposed for the development of obesity-related diabetes in rodent models, in which triglyceride deposits were formed in the pancreatic islets. 8,28 It should now be examined whether the lipid accumulations in aging human β cells bear functional consequences and could therefore explain, at least in part, the higher incidence of type 2 diabetes in aging humans. 29

Acknowledgments

We thank the personnel of the central unit of β Cell Transplant for providing quality-controlled human β cell preparations and the staff of the Diabetes Research Center for preparing rat islet cells. We acknowledge the helpful discussions with Professor Wisse (Department of Cell Biology, Universiteit Brussel) and the technical assistance of Jean Claude Hannaert.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to D. Pipeleers, Diabetes Research Center, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Laarbeeklaan 103, 1090 Brussels, Belgium. E-mail: dpip@mebo.vub.ac.be.

Supported by grants from the European Community (BMH-CT95–1561), the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International (JDF 995004), the Belgian

Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (F.W.O.G.0039.96 and G.0376.97), and the services of the Prime Minister (Interuniversity Attraction Pole P4/21). M. C. is Aspirant and A. G. is Postdoctoral Fellow of the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders (F. W. O.).

References

- 1.Zimmet PZ, McCarty DJ, de Courten MP: The global epidemiology of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and the metabolic syndrome. J Diab Comp 1997, 11:60-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall JA, Hamman RF, Baxter J: High-fat, low-carbohydrate diet, and the etiology of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: the San Luis Valley Diabetes Study. Am J Epidemiol 1991, 134:590-603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall JA, Hoag S, Shetterly S, Hamman RF: Dietary fat predicts conversion from impaired glucose tolerance to NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1994, 17:50-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGarry JD: What if Minkowski had been ageusic? An alternative angle on diabetes. Science 1992, 258:766–770 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.McGarry JD: Disordered metabolism in diabetes: have we underemphasized the fat component? J Cell Biochem 1994, 55(suppl):29-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groop LC, Saloranta C, Shank M, Bonadonna RC, Ferrannini E, DeFronzo RA: The role of free fatty acid metabolism in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance in obesity and noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991, 72:96-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Y-P, Grill VE: Long-term exposure of rat pancreatic islets to fatty acids inhibits glucose-induced insulin secretion and biosynthesis through a glucose fatty acid cycle. J Clin Invest 1994, 93:870-876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y, Hirose H, Ohneda M, Johnson JH, McGarry JD, Unger RH: β-Cell lipotoxicity in the pathogenesis of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus of obese rats: impairment in adipocyte-β-cell relationships. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994, 91:10878-10882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimabukuro M, Zhou Y-T, Levi M, Unger RH: Fatty acid-induced β-cell apoptosis: a link between obesity and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95:2498-2502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grupping AY, Cnop M, Van Schravendijk CFH, Hannaert J-C, Van Berkel TJC, Pipeleers DG: Low density lipoprotein binding and uptake by human and rat islet β cells. Endocrinology 1997, 138:4064-4068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pipeleers DG, in’t Veld PA, Van De Winkel M, Maes E, Schuit FC, Gepts W: A new in vitro model for the study of pancreatic A and B cells. Endocrinology 1985, 117:806–816 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Keymeulen B, Ling Z, Gorus FK, Delvaux G, Bouwens L, Grupping AY, Hendrieckx C, Pipeleers-Marichal M, Van Schravendijk CFH, Salmela K, Pipeleers DG: Implantation of standardized β-cell grafts in a liver segment of IDDM patients: graft and recipient characteristics in two cases of insulin-independence under maintenance immunosuppression for prior kidney graft. Diabetologia 1998, 41:452-459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ling Z, Pipeleers DG: Prolonged exposure of human β cells to elevated glucose levels results in sustained cellular activation leading to a loss of glucose regulation. J Clin Invest 1996, 98:2805-2812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redgrave TG, Roberts DCK, West CE: Separation of plasma lipoproteins by density-gradient ultracentrifugation. Anal Biochem 1975, 65:42-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Handley DA, Arbeeny CM, Witte LD, Chien S: Colloidal gold-low density lipoprotein conjugates as membrane receptor probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1981, 78:368-371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Jong ASH: Mechanisms of metal-salt methods in enzyme cytochemistry with special reference to acid phosphatase. Histochem J 1982, 14:1-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramirez-Zacarias J, Castro-Munozledo F, Kuri-Harcuch W: Quantitation of adipose conversion and triglycerides by staining intracytoplasmic lipids with oil red O. Histochemistry 1992, 97:493-497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacy PE: The pancreatic β cell: structure and function. N Engl J Med 1967, 276:187-195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majno G: Symptoms of cellular disease: intracellular accumulations. Majno G Joris I eds. Cells, Tissues, and Disease: Principles of General Pathology. 1996, :pp 76-90 MA, Blackwell Science, Cambridge [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown MS, Goldstein JL: A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science 1986, 232:34-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paavola LG, Strauss JF, Boyd CO, Nestler JE: Uptake of gold- and [3H]cholesteryl linoleate-labeled human low density lipoprotein by cultured rat granulosa cells: cellular mechanisms involved in lipoprotein metabolism and their importance to steroidogenesis. J Cell Biol 1985, 100:1235-1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein JL, Brunschede GY, Brown MS: Inhibition of proteolytic degradation of low density lipoprotein in human fibroblasts by chloroquine, concanavalin A, and Triton WR 1339. J Biol Chem 1975, 250:7854-7862 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weichselbaum A, Stangl E: Wien klin Wchnschr 1902, 15:969–976

- 24.Weichselbaum A: Sitzungsber Akad Wssnsch Math Nat Kl 1910, 119:73–78

- 25.Warren S, LeCompte PM: The Pathology of Diabetes Mellitus. 1952:pp 53-55 Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia

- 26.Warren S: The Pathology of Diabetes Mellitus. 1938:pp 31-36 Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia

- 27.Unger RH: Lipotoxicity in the pathogenesis of obesity-dependent NIDDM. Diabetes 1995, 44:863-870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Man Z-W, Zhu M, Noma Y, Toide K, Sato T, Asahi Y, Hirashima T, Mori S, Kawano K, Mizuno A, Sano T, Shima K: Impaired β-cell function, and deposition of fat droplets in the pancreas as a consequence of hypertriglyceridemia in OLETF rat, a model of spontaneous NIDDM. Diabetes 1997, 46:1718–1724 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Halter JB: Effects of aging on glucose homeostasis. LeRoith D Taylor SI Olefsky JM eds. Diabetes Mellitus: A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 1996, :pp 484-491 Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]