Abstract

Intravascular ventricular defibrillation and intravascular atrial defibrillation have many similarities, some of which are as follows. An important factor influencing the outcome of the shock is the potential gradient field created throughout the ventricles or the atria by the shock. A minimum potential gradient is required throughout the ventricles and probably the atria to defibrillate. The value of this minimum potential gradient is affected by several factors including the duration, tilt, and number of phases of the waveform. For shock strengths near the defibrillation threshold, earliest activation following failed shocks arises in a region in which the potential gradient is low. The defibrillation threshold energy can be decreased by adding a third and even a fourth defibrillation electrode in regions where the shock potential gradient is low for the shock field created by the first two defibrillation electrodes and giving two sequential shocks, each through a different set of electrodes. However, the addition of more electrodes and sequential shocks complicates both the device and its implantation.

Since patients are conscious when the atrial defibrillation shock is given, they experience pain during the shock, which is one of the main drawbacks of intravascular atrial defibrillation. Unfortunately, the pain threshold for defibrillation shocks is so low that a shock of less than 1 Joule is uncomfortable and is not much less painful than shocks several times stronger. Therefore, even though electrode configurations exist that have lower atrial defibrillation threshold energy requirements than the atrial defibrillation threshold with standard defibrillation electrode configurations used in implantable cardioverter/defibrillators (ICDs) for ventricular defibrillation, they are not clinically practical because their shocks are almost as painful as with the standard ICD electrode configurations and they would cause the ICD to be more complicated and to take longer and be more difficult to implant.

Keywords: Internal atrial defibrillation

Introduction

Approximately 2.3 million Americans are currently diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (AF), making AF the most common cardiac arrhythmia. While less than 0.1% of patients < 55 years old are diagnosed with AF, it is diagnosed in approximately 9% of patients > 80 years old. As life expectancy increases and more people live into later years, the incidence of AF is expected to increase.1 AF is associated with a decreased quality of life and an increased incidence of stroke, heart failure, an all-cause mortality.2

While efficacy rates for external atrial defibrillation with high energy (up to 200 Joules) rectilinear biphasic waveform are reported to be 90–99%,3–8 high energy (up to 360 Joules) truncated exponential biphasic waveforms are likewise reported to be 95–99%.5–7, 9 Internal cardioversion may be required for some obese patients or patients with obstructive lung disease or asthma who are resistant to external defibrillation.10–13 Initial success rates of 95% have been reported with transvenous intracardiac defibrillation in patients that were refractory to external defibrillation attempts.14 Since internal defibrillation may be accomplished with much lower shock energies than with external defibrillation, internal defibrillation may be accomplished with mild sedation rather than general anesthesia, which may make internal defibrillation preferable for patients at high risk for anesthesia-related complications.15 Internal atrial defibrillation may also be performed during electrophysiologic procedures such as ablation or mapping when defibrillation catheters may be easily placed intravenously.16–18 During mapping and ablation procedures, aggressive atrial pacing or catecholamine administration may be used to increase focal activity and direct ablation procedures to the problematic areas. This may lead to persistent AF which must be terminated electrically rather than pharmacologically as to not change the antiarrhythmic substrate of the cardiac tissue. Atrial defibrillation may be required in 5–10% of cases treated in the electrophysiology laboratory.16

Large shocks associated with external defibrillation are more likely to interfere with ICDs, so patients with implanted devices may also be better served by internal defibrillation shocks. The high currents associated with external atrial defibrillation may be conducted along implanted electrodes and cause endocardial damage. Guidelines specify that programming of ICDs should be modified and/or verified before and after external defibrillation because programmed data may be altered during current surges.10, 11 Internal defibrillation shocks are not associated with these complications in ICD patients.11 While an implanted device was developed capable of defibrillating AF alone,19 all currently available implantable AF defibrillators are combined with VF defibrillation.

In both AF and ventricular fibrillation (VF), the normal conduction sequence of the cardiac tissue is disrupted and rapid, uncoordinated activation of the cardiac tissue results. With both AF and VF, an electrical shock can terminate fibrillation and return the heart to normal sinus rhythm. As discussed below, intravascular ventricular defibrillation and intravascular atrial defibrillation have many similarities.

Importance of Potential Gradient Field in Defibrillation

An important factor influencing the outcome of the shock is the potential gradient field created throughout the ventricles or the atria by the shock. While the total defibrillation current delivered to the atria or ventricles is important, the distribution of the current through the mass of fibrillating cardiac tissue seems to be critical as well. Because the current passes through tissue with finite impedance, a potential gradient is established at each point in the cardiac tissue. If a constant resistivity is assumed in the cardiac tissue, the potential gradient for any section of tissue is directly proportional to the current density passing through the tissue. When transvenous catheters are used to deliver defibrillation shocks, high potential gradients are established near the shocking electrodes and lower potential gradients are established in areas of the heart that are farther from the electrodes. High potential gradient areas have been studied to determine the role of electroporation and stunning of cardiac tissue, but for shocks near the defibrillation threshold (DFT) the low potential gradient areas determine the success or failure of a defibrillation shock. A minimum potential gradient appears to be needed throughout the cardiac tissue to defibrillate. The value of this minimum potential gradient is affected by several factors including the duration, tilt, and number of phases of the waveform. In ventricular defibrillation studies, a typical monophasic truncated exponential waveform requires a minimum potential gradient of approximately 5.4 V/cm while a typical biphasic exponential waveform requires only approximately 2.7 V/cm.20

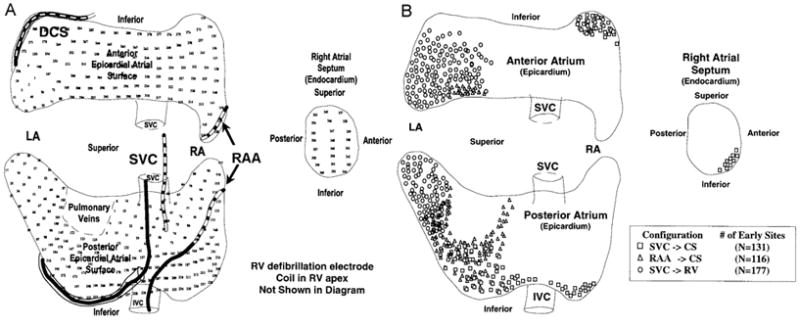

For shock strengths near the defibrillation threshold, earliest activation following failed shocks arises in the region in which the potential gradient is lowest. Cooper et al. conducted a study in sheep that demonstrated that the first activation location moved to the low field gradient area in the atrial tissue farthest from the defibrillation electrodes after failed near threshold shocks in response to the field established by a variety of electrode configurations.21 These investigators inserted defibrillation coils into the coronary sinus (CS), right atrial appendage (RAA), superior vena cava (SVC), and right atrial apex (RV), as shown in Figure 1A. They recorded activation electrograms from 360 electrodes (336 on the epicardial surface of both the right and left atria and 24 from the right atrial septum) immediately following near atrial defibrillation threshold (ADFT) strength shocks. Biphasic shocks were delivered from 3 electrode configurations (shown as anode→cathode for the first phase of the biphasic shock): 1) RAA→CS, 2) SVC→CS, and 3) SVC→RV. With each electrode configuration, first activation after failed shocks emerged from the region where the potential gradient field produced by the shock would be predicted to be low since they are most distant from the defibrillation electrodes. Figure 1B shows the first activation locations after failed shocks.

Figure 1.

A) Atria of sheep with the location of defibrillation electrodes and recording sites. Locations of defibrillation coils in the superior vena cava (SVC), right atrial appendage (RAA), and distal coronary sinus (DCS) are shown. Positions of the 336 epicardial recording sites covering the epicardial surface of both atria and 24 endocardial recording sites on the RA septum are indicated by the electrode number. B) Early activation sites after failed defibrillation shocks. Early sites clustered in the region of assumed low potential field gradient for the electrode configuration used for the shock. Adapted from Cooper et al.,21 with permission.

Alternate Electrode Locations and Sequential Shocks

Internal atrial defibrillation is typically performed on patients that have failed external cardioversion or who are undergoing other procedures in the electrophysiology laboratory.10–13, 16–18 Typical internal defibrillation shocks are delivered from a coronary sinus catheter to a right atrial catheter positioned along the lateral wall to minimize SA or AV nodal damage.16 This configuration is normally successful at energies of < 6–10 J.13 There is also evidence that the standard ventricular triad configuration (right ventricular coil to a superior vena cava coil electrically tied to the ICD can) successfully defibrillates at similar energy leves.22 However, shock levels used for internal defibrillation shocks with these electrode configurations are still too painful to be used without sedation or anesthesia, and research has continued to attempt to lower internal atrial defibrillation shock thresholds to levels that will be tolerated by conscious and unsedated patients.

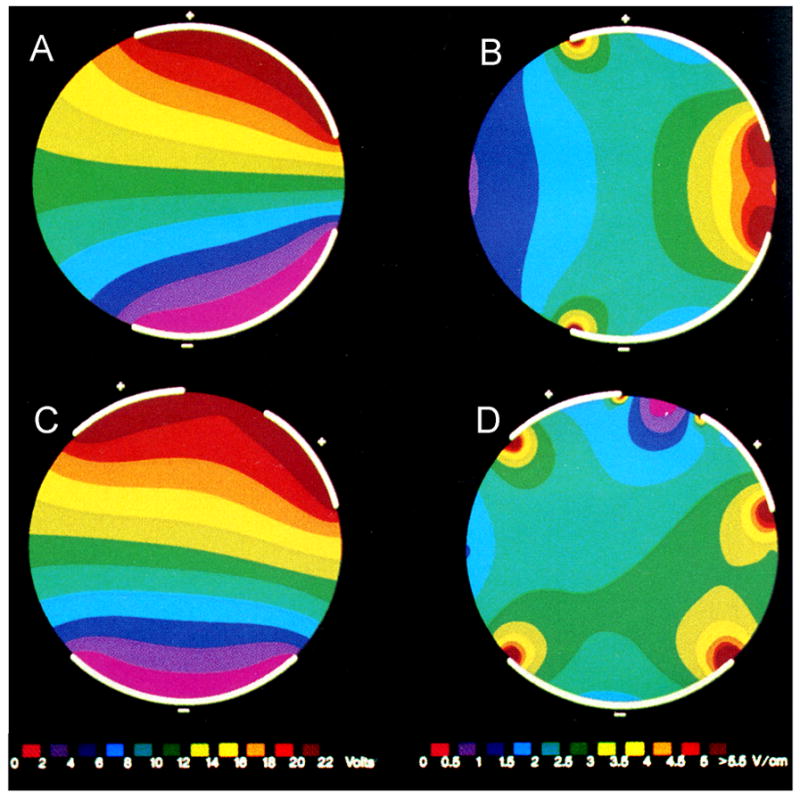

Since fibrillation reemerges from low gradient areas, investigators have lowered DFTs by placing additional defibrillation electrodes in these regions. The DFT energy can be decreased by adding a third and even a fourth defibrillation electrode in regions where the shock potential gradient is low with the first two defibrillation electrodes and giving two sequential shocks. Ideker et al. demonstrated with a simplified model that electrodes that were in direct contact with the heart tended to create areas of low potential gradient at locations distant from the electrodes (Figure 2A and B).23 When an additional electrode was placed in the low field gradient area, and was electrically tied to one of the other electrodes, potential gradient was low between the connected electrodes (Figure 2C and D). To minimize this area of low potential gradient between two connected electrodes, sequential shocks can be delivered so that the low potential gradient areas of the first pair of electrodes are eliminated by the field gradient created with the second pair of electrodes. Using sequential pulses eliminates the region of low field gradient created between two electrodes that are electrically tied together.

Figure 2.

Simplified model to illustrate the effects of changing electrode position and size. The figures on the left (A and C) show potentials established with the electrode configuration while the figures on the right (B and D) show potential gradient. Panel B demonstrates that electrodes placed asymmetrically about the heart show high potential gradient close to the electrodes (right hand side of circle), but low gradient regions at locations far from the electrodes (left hand side of circle). Panel D demonstrates that placing another electrode in the low gradient region reduces the size of the low gradient region on the left hand side of the circle, but that a low gradient region emerges between electrodes that share a common polarity. Adapted from Ideker et al.,23 with permission

When the standard RAA→CS configuration was used, first activation tended to arise near the septum (Figure 1B). Therefore, it was proposed that adding a shocking coil in this region of low potential field gradient might lower ADFTs. Zheng et al.24 conducted a study in sheep in which defibrillation coils were inserted into the RAA, CS, and at the atrial septum (SP) near the region of low potential gradient. They demonstrated a reduction in ADFT energy of 68% (0.39±0.18 J vs. 1.27±0.67 J) as compared to a control configuration (RAA→CS) by sequentially shocking through the SP electrode to the RAA and CS electrodes (RAA→SP followed by CS→SP). They concluded that the ADFT of the standard RAA→CS control configuration is markedly reduced with an additional electrode at the atrial septum. Subsequent studies have confirmed the value of the SP electrode in lowering ADFTs substantially.25, 26 Sequential shocks where the first phases of each shock were delivered at a constant level (rather than unequal shocks from a single capacitor) lowered peak voltage and current even more.26

Studies in human patients have confirmed that additional shocking electrodes and sequential defibrillation pulses lower ADFTs. In 14 patients defibrillation electrodes were implanted in the RAA, distal coronary sinus (dCS), proximal coronary sinus (CSos), and the left subclavian vein (LSV). Sequentially pulsed defibrillation shocks that included two pathways (RA→dCS then CSos→LSV) reduced the ADFT by more than 50% in delivered energy compared to control shocks (RA→dCS).27

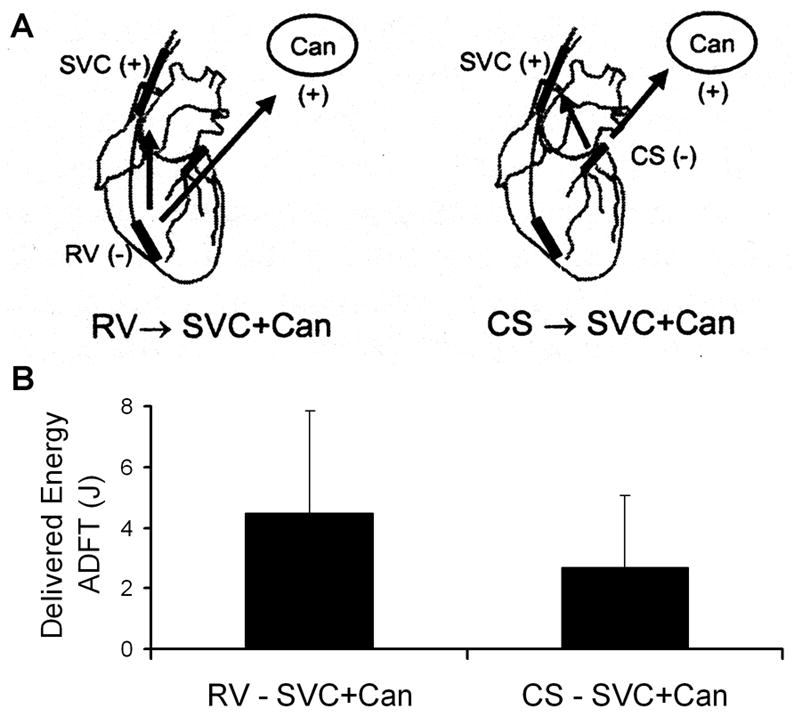

In an attempt to lower ADFTs with a clinically feasible, chronically implantable lead system, Benser et al. included a coronary sinus lead (CS) with RV, SVC, and subcutaneous can (Can) electrodes and tested various shocking configurations in sheep. They reported a reduction of 40% in ADFT by using a CS lead (CS→SVC+Can) in place of the RV lead (RV→SVC+Can), as shown in Figure 3.28 While use of a CS lead in animal models has been shown to lower ADFTs, the results of human trials have been mixed.22, 29, 30

Figure 3.

A) Diagram of the standard ventricular triad defibrillation configuration and an atrial triode electrode configuration B) Compared ADFT delivered energies for the configurations shown in A). Abbreviations are defined in the text. From Benser et al.,28 with permission.

Even though the addition of more electrodes and sequential shocks lowers the ADFT, the use of such strategies also complicates both the device and its implantation. Insertion of additional leads into the coronary venous system or other vascular approaches increase the risk of vascular perforation, clot formation, and other serious complications. Procedure time and hardware complexity also increase so that the benefits of lowering the ADFT must be substantial to justify the increased risk.

Antiarrhythmic Drugs to Facilitate Electrical Cardioversion

Various drugs have been reported to lower the ADFT. Atrial defibrillation shocks delivered while patients were on Flecainide were reported to convert a higher percentage of patients to normal sinus rhythm, but study results differed as to whether Flecainide raised or lowered ADFT levels.31 Ibutilide (a class III antiarrhymic agent) and procainamide (a class IA agent) lowered ADFTs and increased the success rate of atrial defibrillation shocks.31 Amiodarone has been shown to increase the success rate of atrial defibrillation shocks, but raised ADFTs.32 The seemingly contradictory conclusion that Flecainide and Amiodarone may increase defibrillation success rates but also increase ADFT levels may be due to the higher levels of early recurrence of atrial fibrillation following defibrillation in unmedicated patients.

Some of these drugs require time for loading, and so could not be used for immediate defibrillation. In patients with AF that persisted less than 48 hours, chronic anticoagulation is not needed to prevent thromboembolism.33 If AF persists more than 48 hours, chronic anticoagulation is recommended to prevent blood clots from embolizing and causing other serious health problems.2

Patient Tolerance of Atrial Defibrillation Shocks

Rapid atrial defibrillation could reduce complications such as atrial remodeling and clot formation.2, 10, 33 To be able to defibrillate quickly after onset of AF, ICDs with atrial defibrillation capability have been developed. However, the patient is conscious, and he or she experiences pain during the atrial defibrillation shock, which is one of the main drawbacks of intravascular atrial defibrillation.

Unfortunately, the pain threshold for defibrillation shocks is so low that a shock of less than 1 Joule is uncomfortable and is not much less painful than shocks several times larger in energy. In a study of ICD patients, unsedated participants received shocks of 0.4 and 2 Joules in randomized order. Patients were unable to distinguish between the shock levels, and characterized both shocks as relatively uncomfortable, with the second shock perceived as the more painful than the first shock, regardless of the energy delivered.34 Perceived pain increases as the number of shocks increases, so limiting the shocks to one or two shocks increases the probability that such shocks will be tolerated.10

Therefore, even though defibrillation electrode configurations exist that have a lower ADFT energy than that with the standard defibrillation electrode configurations used in ICDs for ventricular defibrillation, they are not clinically advantageous because their shocks are almost as painful as with the standard ICD electrode configurations and they would cause the ICD to be more complicated and to take longer and be more difficult to implant.

Patient Control through Sedation or Nighttime Shocks

Investigators have attempted to reduce the pain associated with shocks for AF by means of sedation or timing shock delivery while the patient is asleep. The atrial defibrillator sedation assessment study (ADSAS) assessed the pain tolerance for patients receiving atrial defibrillation shocks from an implanted ICD when pre-medicated.35 Patients were given oral medication prior to receiving defibrillation shocks for sedation (midazolam elixir), analgesia (morphine sulphate), or combination sedation and analgesia therapy. Patients preferred the sedation option to the other two treatment options, but still described shocks as painful.

A follow-up study, ADSAS 2, tested the response of patients to three defibrillation procedures: 1) self-administered sedation with oral midzolam 30 minutes prior to a shock, 2) taking midzolam prior to bed when AF had been detected with the ICD administering a shock during the night while the patient was sedated, or 3) delivering shocks during the night while the patient was not sedated.36 Approximately 80% of the patients preferred the first treatment option, while 20% chose the second option. None of the patients chose automatic nighttime shocks without sedation. None of the patients reported sleep disturbances or nightmares while receiving shocks while sedated (whether treatment option 1 or 2), but of the patients that experienced nighttime shocks without sedation, 42% reported sleep disturbances and 8 % reported nightmares. Other studies have confirmed that sleep disturbances occur when shocks are given during sleep and that sedation increases patient tolerance for shocks.37, 38

Conclusion

If external cardioversion with biphasic shocks of 150 or 200 J fail, stepping up to 360 J is recommended. If 360 J external shocks fail, internal electrodes should be used. Intracardiac atrial defibrillation is also sometimes needed while performing atrial ablation or mapping. Various techniques including the addition of shocking electrodes, sequential shocks, and waveform improvements have lowered ADFTs significantly with internal shocks, but the pain associated with the shocks remains above tolerable levels for many patients. Since sedation must be used with intracardiac atrial defibrillation shocks, either the standard ventricular triad (RV→SVC+Can) configuration or catheters in the right ventricle and coronary sinsus (RA→CS) may be used. Pain associated with internal defibrillation shocks will need to be reduced to tolerable levels before ICDs with atrial defibrillation capability gain widespread acceptance.

Footnotes

Funding for this work has been provided by NIH NHLBI grants HL-42760, HL-67961, T32 HL07457-16

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–2375. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Halperin JL, Le Heuzey JY, Kay GN, Lowe JE, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Tamargo JL, Wann S, Smith SC, Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Hunt SA, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B, Priori SG, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Camm AJ, Dean V, Deckers JW, Despres C, Dickstein K, Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Morais J, Osterspey A, Zamorano JL. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006;114:e257–354. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mittal S, Ayati S, Stein KM, Schwartzman D, Cavlovich D, Tchou PJ, Markowitz SM, Slotwiner DJ, Scheiner MA, Lerman BB. Transthoracic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: comparison of rectilinear biphasic versus damped sine wave monophasic shocks. Circulation. 2000;101:1282–1287. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.11.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niebauer MJ, Brewer JE, Chung MK, Tchou PJ. Comparison of the rectilinear biphasic waveform with the monophasic damped sine waveform for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation and flutter. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1495–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alatawi F, Gurevitz O, White RD, Ammash NM, Malouf JF, Bruce CJ, Moon BS, Rosales AG, Hodge D, Hammill SC, Gersh BJ, Friedman PA. Prospective, randomized comparison of two biphasic waveforms for the efficacy and safety of transthoracic biphasic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim ML, Kim SG, Park DS, Gross JN, Ferrick KJ, Palma EC, Fisher JD. Comparison of rectilinear biphasic waveform energy versus truncated exponential biphasic waveform energy for transthoracic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1438–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neal S, Ngarmukos T, Lessard D, Rosenthal L. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of two biphasic defibrillator waveforms for the conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:810–814. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00888-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scholten M, Szili-Torok T, Klootwijk P, Jordaens L. Comparison of monophasic and biphasic shocks for transthoracic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Heart. 2003;89:1032–1034. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.9.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirchhof P, Monnig G, Wasmer K, Heinecke A, Breithardt G, Eckardt L, Bocker D. A trial of self-adhesive patch electrodes and hand-held paddle electrodes for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation (MOBIPAPA) Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1292–1297. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy S. Internal defibrillation: where we have been and where we should be going? J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2005;13 (Suppl 1):61–66. doi: 10.1007/s10840-005-1824-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Halperin JL, Le Heuzey JY, Kay GN, Lowe JE, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Tamargo JL, Wann S, Smith SC, Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Hunt SA, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B, Priori SG, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Camm AJ, Dean V, Deckers JW, Despres C, Dickstein K, Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Morais J, Osterspey A, Zamorano JL. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: full text: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation) developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2006;8:651–745. doi: 10.1093/europace/eul097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kistler PM, Sanders P, Morton JB, Vohra JK, Kalman JM, Sparks PB. Effect of body mass index on defibrillation thresholds for internal cardioversion in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:370–372. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boriani G, Biffi M, Camanini C, Luceri RM, Branzi A. Transvenous low energy internal cardioversion for atrial fibrillation: a review of clinical applications and future developments. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001;24:99–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasparini G, Bonso A, Themistoclakis S, Giada F, Raviele A. Low-energy internal cardioversion in patients with long-lasting atrial fibrillation refractory to external electrical cardioversion: results and long-term follow-up. Europace. 2001;3:90–95. doi: 10.1053/eupc.2001.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joglar JA, Kowal RC. Electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Cardiol Clin. 2004;22:101–111. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(03)00119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusumoto FM. Internal atrial and ventricular defibrillation during electrophysiology procedures. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2005;13 (Suppl 1):71–78. doi: 10.1007/s10840-005-0753-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karch MR, Schmieder S, Ndrepepa G, Schneider MA, Zrenner B, Schmitt C. Internal atrial defibrillation during electrophysiological studies and focal atrial fibrillation ablation procedures. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001;24:1464–1469. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.01464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau CP, Tse HF, Ayers GM. Defibrillation-guided radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation secondary to an atrial focus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1217–1226. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00691-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wellens HJ, Lau CP, Luderitz B, Akhtar M, Waldo AL, Camm AJ, Timmermans C, Tse HF, Jung W, Jordaens L, Ayers G. Atrioverter: an implantable device for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 1998;98:1651–1656. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.16.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou X, Daubert JP, Wolf PD, Smith WM, Ideker RE. Epicardial mapping of ventricular defibrillation with monophasic and biphasic shocks in dogs. Circ Res. 1993;72:145–160. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper R, Kenknight B. The role of waveforms and lead configurations for internal atrial cardioversion. Herzschr Elektrophys. 1998;9:76–82. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rashba EJ, Shorofsky SR, Scheiner A, Peters RW, Ma C, Gold MR. Coronary sinus electrode does not reduce atrial defibrillation thresholds. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:647–652. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.02.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ideker RE, Wolf PD, Alferness CA, Krassowska W, Smith WM. Current concepts for selecting the location, size, and shape of defibrillation electrodes. Pacing and Clin Electrophys. 1991;14:227–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1991.tb05093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng X, Benser ME, Walcott GP, Girouard SD, Rollins DL, Smith WM, Ideker RE. Reduction of atrial defibrillation threshold with an interatrial septal electrode. Circulation. 2000;102:2659–2664. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.21.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng X, Benser ME, Walcott GP, Ideker RE. Right atrial septal electrode for reducing the atrial defibrillation threshold. Circulation. 2001;104:1066–1070. doi: 10.1161/hc3501.093816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng X, Benser ME, Walcott GP, Smith WM, Ideker RE. Reduction of the internal atrial defibrillation threshold with balanced orthogonal sequential shocks. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:904–909. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper RA, Plumb VJ, Epstein AE, Kay GN, Ideker RE. Marked reduction in internal atrial defibrillation thresholds with dual- current pathways and sequential shocks in humans. Circulation. 1998;97:2527–2535. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.25.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benser ME, Walcott GP, Killingsworth CR, Girouard SD, Morris MM, Ideker RE. Atrial defibrillation thresholds of electrode configurations available to an atrioventricular defibrillator. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:957–964. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swerdlow CD, Schwartzman D, Hoyt R, Bailin SJ, Koehler JL, Warman EN. Determinants of first-shock success for atrial implantable cardioverter defibrillators. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:347–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tse HF, Timmermans C, Rodriguez LM, Lau CP, Wellens HJ. Effect of coronary sinus electrode on the optimal atrial defibrillation pathway for an atrioventricular defibrillator. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:32–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcus GM, Sung RJ. Antiarrhythmic agents in facilitating electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation and promoting maintenance of sinus rhythm. Cardiology. 2001;95:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000047335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Capucci A, Villani GQ, Marrazzo N, Piepoli M. The complimentary role of drug, ablation and device in electrical therapy of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J Supp. 2001;3:P47–P52. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weigner MJ, Caulfield TA, Danias PG, Silverman DI, Manning WJ. Risk for clinical thromboembolism associated with conversion to sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation lasting less than 48 hours. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:615–620. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-8-199704150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinhaus DM, Cardinal DS, Mongeon L, Musley SK, Foley L, Corrigan S. Internal defibrillation: pain perception of low energy shocks. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25:1090–1093. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell AR, Spurrell PA, Gerritse BE, Sulke N. Improving the acceptability of the atrial defibrillator for the treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation: the atrial defibrillator sedation assessment study (ADSAS) Int J Cardiol. 2004;96:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boodhoo L, Mitchell A, Ujhelyi M, Sulke N. Improving the acceptability of the atrial defibrillator: patient-activated cardioversion versus automatic night cardioversion with and without sedation (ADSAS 2) Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004;27:910–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haffajee CI, Chaudhry GM, Casavant D, Pacetti PE. Efficacy and tolerability of automatic nighttime atrial fibrillation shocks in patients with permanent internal atrial defibrillators. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:875–878. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fabian TJ, Schwartzman DS, Ujhelyi MR, Corey SE, Bigos KL, Pollock BG, Kroboth PD. Decreasing pain and anxiety associated with patient-activated atrial shock: a placebo-controlled study of adjunctive sedation with oral triazolam. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:391–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]