Abstract

Background

Research suggests that substance abusers make more disadvantageous decisions on the simulated gambling task (SGT); such decisions are associated with deviance proneness and antisocial symptoms. This study examines decision-making on the SGT in young adults with alcohol dependence that are treatment-naïve (TxN).

Methods

116 subjects (58 controls, 58 TxNs) were tested on the SGT, where participants choose cards from 4 different decks that vary in terms of the magnitude of the immediate gain (large/small) and the magnitude of long-term loss (larger/smaller). Participants also were assessed on measures of externalizing symptoms, personality traits reflecting social deviance, neuropsychological function, and the density of the family history of alcoholism.

Results

TxNs did not differ from controls on measures of SGT decision-making. SGT performance was not associated with externalizing symptoms, social deviance proneness, or a familial density of alcoholism. Although, TxNs had higher levels of externalizing symptoms, social deviance and familial density of alcoholism compared with controls, these variables were only modestly elevated compared with previous samples of long-term abstinent alcohol dependent individuals who showed decision-making deficits on the SGT.

Conclusions

The results suggest that our sample of young adult TxN adults with alcohol dependence do not have global deficits in decision-making as measured by the SGT, and that their poor decisions regarding their alcohol consumption are more specific to drinking.

Keywords: simulated gambling task, alcoholism, cognition, decision-making

Introduction

Alcoholism and drug abuse are disorders in which people continue their use of harmful substances despite major negative consequences. Bechara and colleagues (1994) developed a simulated gambling task (SGT) that has been used in studies (Bechara et al., 2001; Grant et al., 2000) to examine the mechanisms that underlie the skewed decision-making style of substance abusers. The gambling task imitates real-life decision-making in that it requires an individual to weigh reward versus punishment in an atmosphere of uncertain outcomes. Subjects are asked to choose between decks of cards that have small positive gains associated with relatively small long-term negative consequences (the good decks), and decks of cards with large positive gains associated with large long-term negative consequences (the bad decks). Over the long run, choices from the good decks result in winning money, while choices from the bad decks result in losing money. We all continually weigh the short-term advantages against the long-term consequences of our behavior, but a hallmark of drug and alcohol abuse is persistence in a behavior (drinking) that returns short-term benefit (intoxication), but often leads to significant long-term negative consequences.

The SGT was initially developed to study patients with acquired sociopathy due to damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in an effort to model the global decision-making deficits that presumably contribute to the enduring pattern of disinhibited behavior observed in this population (Bechara et al., 1994; Bechara et al., 1997). Such patients often take part in risky behaviors that are immediately gratifying while ignoring negative future outcomes. It is thought that they cannot see beyond the short-term rewards of their behavior to its potential long-term consequences (Bechara et al., 1994). Compared with controls, when playing the SGT, patients with ventromedial prefrontal lesions consistently chose to draw more cards from decks with larger immediate rewards and larger long-term net losses, than from decks with smaller immediate rewards, smaller delayed punishments and long-term net gains (Bechara et al., 1994; Bechara et al., 1997). Although they performed poorly on the gambling task, such patients performed normally in other cognitive domains (Bechara et al., 1998). The cognitive domains assessed by Bechara and colleagues were verbal and performance IQ from the WAIS-R, memory and attention/concentration as measured by the Wechsler Memory Scale, visual retention measured by the Benton Visual Retention Test, and verbal ability from the COWAT. Additional tests conducted were the Wisconson Card Sorting Task, the Facial Recognition Task, and the Judgment of Line Orientation Task.

Ventromedial prefrontal dysfunction may predispose an individual to make disadvantageous personal choices possibly leading to socially inappropriate, or socially deviant behavior (Bechara et al., 1994; Bechara et al., 1997), or to drink excessively even when it leads to significant problems. As noted above, the SGT was initially developed to study patients with acquired sociopathy due to damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Since that time, Bechara and colleagues have extended their work to show that patients with amygdala damage also show SGT impairments (Bar-On et al., 2003; Bechara et al., 1999).

A number of factors may contribute to the poor decisions that alcoholics make with regards to their drinking, such as global problems in decision-making associated with neuropsychological deficits that predate, or are a consequence, of their alcoholism, specific contextual factors (alcohol cues) and past learning specifically associated with drinking environments (such as conditioned responses), or peer pressure (Fein et al., 2004; Finn and Hall, 2004; Finn et al., 2002). Bechara et al.’s (1994) SGT has been administered to substance abusers by a number of researchers to investigate evidence of global problems in decision-making. Studies show that on the SGT alcoholics (Bechara and Damasio, 2002; Bechara et al., 2001; Mazas et al., 2000) and drug abusers (Grant et al., 2000; Petry et al., 1998) have a pattern of disadvantageous decision making similar to that of ventromedial prefrontal lesion patients, characterized by favoring larger immediate rewards while disregarding long-term negative consequences. Clark and Robbins (2002) note the centrality of abnormal decision making to addictive behavior, and hypothesize that this association between addiction and impaired decision making underlies performance deficits on the gambling task in substance abusers.

Evidence also suggests that these decision-making deficits are associated with diminished behavioral control, social deviance, and antisocial traits (Fein et al., 2004; Stout et al., 2005), known to predate and predict the development of alcoholism in prospective studies (Caspi et al., 1996; Chassin et al., 1999; Pulkkinen and Pitkanen, 1994). In fact, a number of studies suggest that global decision-making deficits assessed with laboratory tasks are observed only in those alcoholics who have a history of antisocial behavior (Finn et al., 2002; Mazas et al., 2000; Petry, 2002). Such deficits are either not present (Finn et al., 2002), or are much milder (Mazas et al., 2000; Petry, 2002), in non-antisocial alcoholics. The covariance of antisocial traits with decision-making deficits on laboratory tasks is consistent with the hypothesis that global decision-making deficits may predispose to alcoholism, although it also may be that long-term alcohol abuse might contribute to antisociality and global decision-making deficits.

In a recent paper on long-term abstinent alcoholics (abstinence duration ranging from 6 months to 13 years, with a mean abstinent duration of 6.7 years), we demonstrated that abstinent alcoholics were impaired on the SGT compared to age matched controls (Fein et al., 2004), and that impaired decision-making was associated with low levels of socialization. In a second paper (Harper et al., 2005), we showed that the same group of long-term abstinent alcoholics had reduced gray matter in the region of the amygdala, an area implicated in impaired gambling task performance (Bar-On et al., 2003; Bechara et al., 1999). Although we believe those results partly reflect the consequences of long-term alcohol abuse, we could not rule out the possibility that the results reflected a factor associated with the genetic vulnerability to alcoholism, and was in fact an antecedent rather than a consequence of alcoholism. In a third paper (Fein and Landman, 2005), we demonstrated that treated and treatment naïve individuals come from different populations in regards to their alcohol use. In that paper, we rejected the hypothesis that the treatment naïve alcoholics and the treated alcoholics have similar alcohol use trajectories over time, with the treatment naïve sample simply being observed earlier in their alcohol use histories. Instead we concluded that the two groups come from different populations with regard to alcohol use in the early years of abusive drinking (in fact, the treated alcoholics had alcohol doses over 50% higher than treatment-naïve alcoholics in the years just after they began drinking heavily). This suggests that results from studies of alcoholics in treatment or post-treatment (i.e., most studies of alcoholics) cannot be generalized to untreated individuals (who comprise the majority of alcoholics). If this holds true, one would not expect to see the same degree of decision-making impairments in treatment naïve samples as were observed in the long-term abstinent alcohol dependent sample.

The current study was designed to help address these issues. Previous studies have used either active alcoholics (Mazas et al., 2000), drug addicts (Grant et al., 2000), alcoholics just prior to treatment (Bechara, 2001; Bechara and Damasio, 2002), or substance abusers in treatment (Petry et al., 1998). In the current study, we examine performance on the SGT in treatment naïve alcohol dependent individuals compared to age and gender matched controls. We also examine the association of SGT performance with socially deviant, antisocial personality traits, performance in various cognitive domains, and with alcohol use variables. Further analyses were performed comparing the treatment naïve group and the long-term abstinent alcohol dependent sample from our previous paper (Fein et al., 2004).

Materials and Methods

Participants

The treatment naïve alcohol dependent group and the control group were age and gender matched, each consisting of twenty-four women and thirty-four men. All participants were recruited from the community by café postings, newspaper advertisements and a local Internet site. The inclusion criteria for the control group was a lifetime drinking average of less than 30 drinks per month with no periods of more than 60 drinks per month. Treatment naïve (TxN) participants needed to meet DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for current alcohol dependence. Exclusion criteria for both groups were 1) lifetime or current diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder, 2) history of drug (other than nicotine or caffeine) dependence or abuse, 3) significant history of head trauma or cranial surgery, 4) history of diabetes, stroke, or hypertension that required medical intervention, or of other significant neurological disease, or 5) clinical evidence of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. All participants were informed of the study’s procedures and aims, and signed a consent form prior to their participation. Subjects participated in four sessions that lasted from an hour and a half to three hours, which included clinical, neuropsychological, electrophysiological, and neuroimaging assessments. All participants were asked to abstain from using alcohol for at least 24 hours prior to any lab visits, and a Breathalyzer test was administered to all subjects prior to each session. We had no positive Breathalyzer test results Subjects who completed testing were paid for time and travel, and those who completed the entire study were also given a completion bonus.

Procedure

All participants were assessed using a computerized psychiatric Diagnostic Interview Schedule (Robins et al., 1998) (c-DIS). Participants also were interviewed on their drug and alcohol use using the lifetime drinking history methodology (Skinner and Sheu, 1982; Sobell and Sobell, 1990; Sobell et al., 1988), completed questionnaires assessing social deviance proneness, family density of alcoholism, and were administered the SGT along with a neuropsychological assessment. Medical histories also were reviewed and liver functions tested.

Assessments

Personality and externalizing symptoms

The presence of personality traits indicative of deviance proneness and externalizing disorders were assessed using the Psychopathic Deviance Scale of the MMPI-2 (MMPI_Pd) (Hathaway, 1989) the Socialization Scale of the California Psychological Inventory (CPI_So) (Gough, 1969) and the sum of positive responses to the antisocial personality and conduct disorder questions on the c-DIS (externalizing symptoms).

Alcohol Use Variables

Based upon subject’s responses on the lifetime drinking history, alcohol use variables were defined. Alcohol lifetime duration refers to the number of months of alcohol consumption in the individual’s lifetime, while peak duration refers to the number of months of peak alcohol use. Alcohol lifetime dose is the average number of drinks per month of alcohol consumption over the subject’s lifetime, while peak dose is the number of drinks per month during their period of peak alcohol consumption. Age and level at first heavy use were also included as alcohol use variables.

Familial Drinking Density (FamDD)

The Family Drinking Questionnaire (Mann et al., 1985; Stoltenberg et al., 1998) was administered in the first session to assess the density of problem drinkers in the participant’s family. Participants were asked to rate the members of their family as being alcohol abstainers, alcohol users with no problem, or problem drinkers. Family Drinking Density 1 (FamDD_1) was defined as the total number of problem drinking 1st degree relatives divided by the total number of 1st degree relatives. FamDD_2 is the same as FamDD_1, except it addresses the proportion of 2nd degree relatives.

Neuropsychological measures

A neuropsychological assessment was also administered, covering the domains of attention, auditory working memory, verbal skills, abstraction/cognitive flexibility/executive functioning, immediate and delayed memory, motor and psychomotor skills, reaction time, and spatial processing. The tests used to assess each domain were: (1) Attention (Stroop Color (Golden, 1975), Micro-Cog (MC) Numbers Forward, MC Numbers Reversed, MC alphabet, MC Word List 1 (Powell et al., 1993), (2) Verbal Fluency (COWAT (Benton and Hamsher, 1983), AMNART (Grober and Sliwinski, 1991)), (3) Abstraction/Cognitive Flexibility (Short Categories (Wetzel, 1982), Stroop interference score (Golden, 1975), Trail Making Test B (Reitan and Wolfson, 1985), MC Analogies (Powell et al., 1993), MC Object Match A and B (Powell et al., 1993)), (4) Psychomotor (Trails A (Reitan and Wolfson, 1985), Symbol Digit (Smith, 1968)), (5) Immediate Memory (MC Story immediate 1 and 2 (Powell et al., 1993), Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure test - immediate recall (Osterrieth, 1944), MC Word List 2 (Powell et al., 1993)), (6) Delayed Memory (MC Story Delay 1 and 2 (Powell et al., 1993), MC Address delay (Powell et al., 1993), Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure test - delayed recall (Osterrieth, 1944)), (7) Motor Skills (Grooved Pegboard (Klove, 1963)), (8) Reaction Time (MC Timers 1 and 2 (Powell et al., 1993)), (9) Spatial Processing (MC Tic Tac 1 and 2, MC Clocks (Powell et al., 1993), Block Design (Wechsler, 1981)), and (10) Auditory Working Memory (PASAT at delays of 2.4, 2.0, 1.6, and 1.2 seconds (Gronwall, 1977)).

SGT Administration

The game begins with $2000 of ‘fake’ money. The participants’ task is to try to win as much money as possible. They are asked to select one card at a time from one of the four decks shown. Some cards will add money and some cards will subtract money from their running total. Participants are told that they can switch from one deck to another at any time and as often as they wish. Each deck has a total of 60 cards with the game ending after a total of 100 cards are selected. They are told that they will not know when the game will end, that they should continue to choose from whichever deck(s) they prefer until the game ends, that some decks are better than others, and that the computer does not change the order of cards after the game starts, make you loose at random, or make you loose money based on the last card chosen. The dependent variable for the gambling task is a measure of advantageous decision bias indexed as the number of cards chosen from the ‘good’ decks minus the number of cards chosen from the ‘bad’ decks.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS (SPSS Inc., 2004). Analysis of variance for unbalanced designs was carried out using the General Linear Models procedure. Pearson correlations were used to examine associations.

Results

SGT Performance

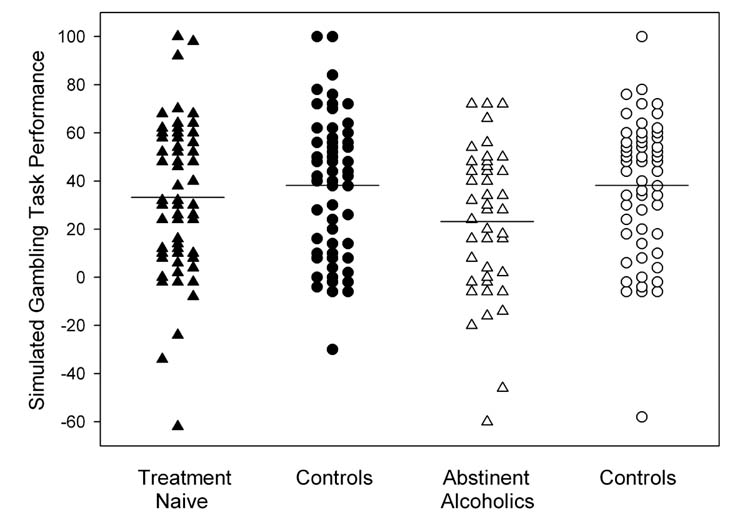

Treatment naïve individuals and controls did not differ in their performance on the simulated gambling task (F1, 112 = 1.04, p = 0.31). Additionally, there were no gender (F1, 112 = 0.002, p = 0.96) or group by gender interactions (F1, 112 = 0.785, p = 0.38). Figure 1 presents the raw gambling game scores for the TxN sample and the controls used in this analysis, as well as for the abstinent alcoholic group and controls from our previous study.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots of the raw SGT scores (number of cards drawn from the ‘good’ decks, minus the number of cards drawn from the ‘bad’ decks) for the TxN group (▲), the TxN’s controls (●), the abstinent alcoholics (△), and the abstinent alcoholic’s controls (○). The horizontal lines represent the mean for each of the groups. There were no group differences in regards to SGT performance between the TxN sample and either their controls or the abstinent alcoholic sample.

Alcohol Use, Family Drinking Density measures and SGT Performance

No significant correlations were observed within the treatment naïve sample between alcohol use variables and performance on the simulated gambling task. The TxN sample compared to controls showed a greater percentage of problem drinking 2nd degree relatives (F1, 112 = 7.93, p < 0.01) and a trend toward a greater percentage of problem drinking 1st degree relatives (F1, 112 = 2.97, p = 0.09). However, when examined as a covariate, neither of these Family Density measures was associated with gambling task performance, nor were there any interactions of either of these covariates with group, gender, or group by gender.

Externalizing symptoms, personality measures, and SGT Performance

The TxN group had more externalizing symptoms (F1, 112 = 11.89, p = 0.001) than the control group. The TxN group also had lower scores on the CPI_So scale (F1, 112 = 38.13, p < 0.001) and higher scores on the MMPI_Pd scale (F1, 112 = 13.56, p < 0.001), both indicating greater deviance proneness. No significant correlations were observed between gambling task performance and any of the above measures.

Neuropsychological performance

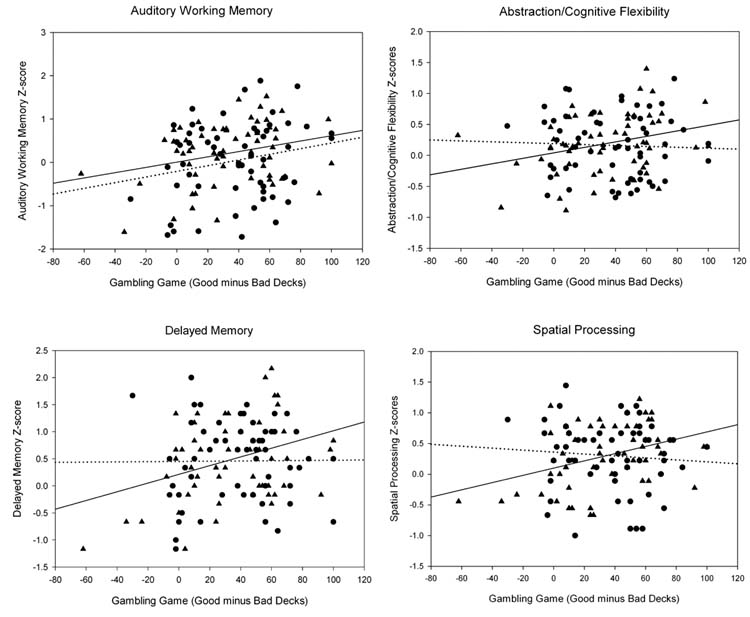

The two groups differed only in the attention domain, with the TxN group performing significantly better than controls (F1, 110 = 8.48, p < 0.01). Within the TxN group, gambling task performance was positively associated with Auditory Working Memory (r = 0.28, p < 0.05), Abstraction/Cognitive Flexibility (r = 0.30, p < 0.05), Delayed Memory (r = 0.35, p < 0.01), and Spatial Processing (r = 0.37, p < 0.01). No associations were found between gambling task performance and neuropsychological variables in the control group. These data are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Scatter plots and correlations between SGT performance and various neuropsychological (NP) domains. The TxN sample is represented by ▲’s, and the solid line represents their association between SGT performance and NP scores. The controls are represented by ●’s, and their association between SGT performance and NP scores are represented by a dotted line. Within the TxN group, gambling task performance was positively associated with Auditory Working Memory (p < 0.05), Abstraction/Cognitive Flexibility (p < 0.05), Delayed Memory (p < 0.01), and Spatial Processing (p < 0.01). Within the control group there were no significant associations.

Differences Between Long-Term Abstinent Alcoholics and the TxN Group, and between the Two Control Groups

As noted above, we previously reported impaired SGT performance in long-term abstinent alcoholics vs. normal controls (Fein et al., 2004). To try to make sense of the current result in the context of the prior findings, we examined how our current samples differed from the samples in the earlier study. The abstinent alcoholic sample was significantly older than the TxN sample, but this was to be expected given the nature of the sample (they had already been through treatment and achieved abstinence for a significant length of time). Age, however, did not appear to be an issue, given that the two control groups, who were age matched to the alcohol groups, had nearly identical performances on the gambling task. Furthermore, neither of the alcohol or control groups showed any significant associations between age and gambling task performance (all r’s < ±0.22, all p’s > 0.16). Overall, the abstinent alcoholic group demonstrated increased severity in terms of the alcohol use measures, a higher degree of FAM_DD, and increased deviance proneness and externalizing symptoms than that of the TxN sample. Table 1 presents a summary of these comparisons. The TxN and long-term abstinent alcoholic groups did not differ significantly in their performance on the simulated gambling task (F1, 97 = 1.94, p = 0.17). However, in regards to SGT performance, the TXN group’s scores were 13% lower than their controls, but 30% higher than the abstinent alcoholic’s scores; thus, their scores were much more similar to those of controls than to those of abstinent alcoholics. Power analysis was conducted in order to determine how large of a sample would be necessary to establish whether the TxN’s SGT performance is different from controls or from long-term abstinent alcohol dependent individuals. To achieve a power of 0.80 to establish that TxN performed worse than controls, there would need to be approximately 585 controls and TxN individuals in each group (780 for a power of 0.90). To achieve power of 0.80 to establish that TxN performed better than long-term abstinent alcohol dependent individuals, about 150 subjects in each group would be needed (200 in each group for a power of 0.90). The control groups from both of the studies performed comparably on the SGT, suggesting that TxN and long-term abstinent alcohol dependent samples can be compared directly, without the need for each sample to have its own age-comparable control sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participant Groups

| Tx Naïve Study | Abstinent Alcoholic Study | Effect Size (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tx Naïve (N=58) | Controls (N=58) | Abs. Alc (N=43) | Controls (N=58) | TxN vs. Controls | Abs. Alcs Vs TxN | Controls Vs Controls | |

| Variable | |||||||

| Age (years) | 31.1 ± 7.8 | 31.3 ± 7.9 | 46.5 ± 6.6 | 44.6 ± 6.6 | 0.0 | 53.9b | 46.0b |

| Years Education | 16.2 ± 1.5 | 16.5 ± 1.8 | 15.7 ± 2.1 | 16.2 ± 1.8 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 0.7 |

|

| |||||||

| Alcohol Use Variables | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Duration of Active Drinking (mos) | 181.2 ± 95.2 | 132.8 ± 98.3 | 260.6 ± 93.7 | 251.2 ± 130.3 | 5.9a | 15.7b | 19.6b |

| Average Lifetime Drinking Dose (std. drinks/mos) | 84.9 ± 43.3 | 6.6 ± 6.3 | 157.8 ± 131.8 | 6.8 ± 7.1 | 64.3a | 14.2*** | 0.2 |

| Duration of Peak Drinking (mos) | 55.6 ± 55.1 | 59.3 ± 90.9 | 74.4 ± 73.4 | 121.2 ± 136.8 | 0.0a | 2.6 | 7.3b |

| Peak Drinking Dose (std. drinks/mo) | 150.9 ± 113.1 | 14.9 ± 13.6 | 317.4 ± 250.9 | 15.9 ± 18.0 | 41.9a | 17.5*** | 0.1 |

| Age First met Criteria for Heavy Use | 21.2 ± 4.9 | N/A | 23.5 ± 6.4 | N/A | N/A | 6.3* | N/A |

| Level at First Heavy Use | 135.9 ± 42.4 | N/A | 187.1 ± 117.5 | N/A | N/A | 9.1** | N/A |

|

| |||||||

| Family Drinking Density | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| cFamDD_1 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 2.6 | 14.5*** | 0.7 |

| dFamDD_2 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 6.6** | 2.0 | 0.7 |

|

| |||||||

| Deviance Proneness & Externalizing Symptoms | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| CPI Socialization Scale | 31.6 ± 5.4 | 37.2 ± 4.5 | 27.7 ± 5.9 | 37.1 ± 3.7 | 25.4*** | 10.4*** | 0.2 |

| MMPI Pd Scale | 18.7 ± 4.5 | 16.1 ± 3.2 | 22.0 ± 4.2 | 16.0 ± 3.6 | 10.8*** | 11.7*** | 0.0 |

| eExternalizing Symptoms (#) | 9.8 ± 7.7 | 5.6 ± 5.1 | 14.2 ± 7.4 | 4.7 ± 4.3 | 9.6*** | 9.1** | 0.0 |

|

| |||||||

| Gambling Game | 33.2 ± 31.7 | 38.2 ± 29.2 | 23.1 ± 30.3 | 38.2 ± 28.2 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.1 |

Measures are reported mean ± standard deviation. Effect is significance:

p≤0.05,

p≤0.01,

p≤0.001.

Statistical comparisons of the groups on alcohol use variables are not valid since alcohol use was part of the group selection criteria.

Statistical comparisons on age and variables associated with subject’s age are not appropriate since age was associated with the study selection criteria.

Total number of problem drinking 1st degree relatives divided by the total number of1st degree relatives.

Total number of problem drinking 2nd degree relatives divided by the total number of 2nd degree relatives.

Sum of antisocial personality disorder and conduct disorder symptoms from the DIS N/A: Not applicable; mos: months; std. drinks/mo: number of standard drinks per month

Discussion

Our sample of young-adult treatment-naïve individuals with alcohol dependence (TxN) did not show any evidence of deficits in decision-making on the SGT. SGT performance was not associated with externalizing symptoms, personality indicators of social deviance, or a family density of alcoholism, or measures of alcohol use. SGT performance was associated with measures of working memory capacity, abstraction, and spatial processing within the TxN group, but the TxN group did not show any evidence of overall neuropsychological deficits compared with controls. In fact, the TxN group performed better than controls on the attention domain. We do not know if this is a real finding (given that they performed better than controls on one of ten domains at p<.01, this result would not be significant if corrected for multiple comparisons); nevertheless, it is indicative of the finding that the TxN group does not evidence cognitive impairment. The TxN group had higher levels of externalizing symptoms and higher levels of deviance proneness than controls; however, the levels of externalizing symptoms and deviance proneness were not as high as that in our previous sample of long-term abstinent alcoholics, who had impaired decision-making in our earlier study using the SGT (Fein et al., 2004). It is not clear exactly why the TxN group did not make poor decisions on the SGT, but the results suggest that this sample does not have the global decision-making deficits that are likely to be detected by the SGT. While TxN individuals clearly make poor decisions in regards to their drinking habits, they do not make poor decisions on the SGT. This suggests that their poor decisions are more specific to their drinking, and do not reflect a global deficit in decision making. In addition, the results provide further evidence that alcohol dependence is not a uniform, homogeneous disorder, but a disorder that encompasses a number of distinct populations.

There are a number of possible explanations for our failure to find evidence of decision-making deficits in the TxN sample. First, it may be that the decision-making deficits observed on the gambling task in other samples are a reflection of the long-term consequence of chronic alcohol abuse and physiological dependence on alcohol. Our sample of young, treatment naïve alcoholics had less severe symptoms of alcohol abuse/dependence, and did not drink as heavily nor as long as our sample of abstinent alcoholics who showed evidence of decision-making deficits (Fein et al., 2004). It might be that physiological dependence on alcohol leads the individual to pay more attention in general to short-term outcomes, because the short-term outcome of significant withdrawal symptoms is so motivationally significant for severe alcoholics. In other words, as an individual becomes more and more physiologically dependent on alcohol, the individual becomes more and more concerned about the short-term outcome of withdrawal. As alcohol seeking and consumption behaviors begin to dominate their lives, they develop the habit of constantly making decisions that put far more weight on short-term outcomes. It is also possible that the impact of long-term exposure to alcohol and physiological dependence on brain structures, such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, results in a condition quite similar to that displayed by the patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions (Bechara et al., 1994) or amygdala lesions (Bar-On et al., 2003; Bechara et al., 2003).

Second, as suggested above, it also may be that our TxN sample comes from a different population of alcohol dependent individuals, who do not have either a high level of genetic vulnerability to alcoholism or a global decision-making deficit that predates their alcoholism. The TxN group had significantly fewer problem drinker family members compared with our treated alcoholics, which suggests that they have a lower genetic vulnerability to alcoholism. Our TxN subjects also did not show very high levels of deviance proneness or externalizing symptoms compared with other samples of alcoholics that demonstrate decision-making deficits, such as our sample of abstinent alcoholics (Fein et al., 2004) or the antisocial alcoholics in Mazas et al (2000) or in Finn et al (2002). It may be that the term “alcoholism” as commonly understood in our society refers only to the more virulent form of alcohol dependence that involves higher genetic vulnerability, SGT impairments, and more severe early alcohol use trajectories. The population studied here may have alcohol dependence that can remit as suggested by the work of Schulenberg et al., (1996), Sher & Gotham, (1999), or Dawson et al., (2005).

Deviance proneness and antisocial traits are typically associated with decision-making deficits in substance abusers (Fein et al., 2004; Finn et al., 2002; Mazas et al., 2000; Stout et al., 2005). In contrast, our data suggests that the decision-making problems in our TxN subjects may be specific to their drinking and not evident in other domains of their life. However, we did not carefully assess the decision-making of our TxN subjects in other contexts, or with regards to drinking itself. If we are to understand the nature of decision-making problems in the range of types, or degrees of severity, of alcoholism, then it is essential that researchers attempt to characterize the decision-making of alcoholics across different domains (i.e., behaviors) and contexts (e.g., drinking versus non-drinking contexts). Future research should attempt to examine how individual alcoholics, well-characterized in terms of personality, family history, cognitive abilities, and psychopathology, make decisions in domains such as alcohol consumption, sexual behavior, money-management (including purchasing behavior), work-related behaviors, eating behaviors, interpersonal conflict, emotion-provoking situations, and other contexts that are motivationally relevant to the individual. Furthermore, it is also very important that researchers assess the influence of the typical context in which the individual makes these sorts of decisions. Animal research suggests that context is an important influence in determining drug administration behavior and response (Robinson and Berridge, 1993). For instance, our TxN subjects might make impulsive decisions when at a bar, or typical drinking context, but not in other situations, such as at home with family members or in artificial laboratory environments. Finally, it may be that the decision-making deficits in TxN subjects are subtler or somewhat different than those of our long-term abstinent alcoholics or other samples of substance abusers that show deficits on the gambling task. Although the gambling task models real-life decisions that involve weighing short-term rewards and long-term consequences, it remains an artificial task and it may not be sensitive to more subtle deficits in decision-making, or to the influence of context on decision-making. Given these issues, it may not be the best measure of impaired decision-making in young alcoholics.

In summary, our sample of young-adult treatment-naïve alcoholics did not show any evidence of deficits in decision-making on the SGT in comparison to controls. SGT performance was not associated with measures of antisocial symptoms or traits, which were not very elevated in the TxN alcoholics compared to other samples of alcoholics who do poorly on the SGT. In addition, SGT performance was not associated with externalizing symptoms, personality indicators of social deviance, family density of alcoholism, or measures of alcohol use habits. This suggests that the poor decisions of TxN participants are more specific to their drinking, and do not reflect global deficits in decision-making. Additional research is needed on the nature and mechanisms associated with specific and global decision-making deficits, and their relationship with long-term outcomes in alcoholic individuals.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants AA11311 (GF) and AA13659 (GF), both from the National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV-R: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On R, Tranel D, Denburg NL, Bechara A. Exploring the neurological substrate of emotional and social intelligence. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 8):1790–800. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. Neurobiology of decision-making: risk and reward. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2001;6(3):205–16. doi: 10.1053/scnp.2001.22927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio AR, Damasio H, Anderson SW. Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition. 1994;50(1–3):7–15. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H. Decision-making and addiction (part I): impaired activation of somatic states in substance dependent individuals when pondering decisions with negative future consequences. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40(10):1675–89. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR. Role of the amygdala in decision-making. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;985:356–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR, Lee GP. Different contributions of the human amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex to decision-making. J Neurosci. 1999;19(13):5473–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05473.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Anderson SW. Dissociation of working memory from decision making within the human prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 1998;18(1):428–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00428.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR. Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science. 1997;275(5304):1293–5. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Dolan S, Denburg N, Hindes A, Anderson SW, Nathan PE. Decision-making deficits, linked to a dysfunctional ventromedial prefrontal cortex, revealed in alcohol and stimulant abusers. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39(4):376–89. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher K. Multilingual aphasia examination. AJA Associates; Iowa City: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(11):1033–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, DeLucia C, Todd M. A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics: predicting young adult substance use disorders, anxiety, and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108(1):106–19. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Robbins T. Decision-making deficits in drug addiction. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6(9):361. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01960-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Huang B, Ruan WJ. Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001–2002. Addiction. 2005;100(3):281–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein G, Klein L, Finn P. Impairment on a Simulated Gambling Task in Long-Term Abstinent Alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(10):1487–91. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000141642.39065.9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein G, Landman B. Treated and treatment-naive alcoholics come from different populations. Alcohol. 2005;35(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Hall J. Cognitive ability and risk for alcoholism: short-term memory capacity and intelligence moderate personality risk for alcohol problems. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113(4):569–81. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Mazas CA, Justus AN, Steinmetz J. Early-onset alcoholism with conduct disorder: go/no go learning deficits, working memory capacity, and personality. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(2):186–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CJ. A group form of the Stroop color and word test. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1975;39:386–388. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa3904_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough HGPD. Manual for the California Psychological Inventory (So Scale) Consulting Psychological Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, Contoreggi C, London ED. Drug abusers show impaired performance in a laboratory test of decision making. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38(8):1180–7. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Sliwinski M. Development and validation of a model for estimating premorbid verbal intelligence in the elderly. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1991;13(6):933–49. doi: 10.1080/01688639108405109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronwall DM. Paced auditory serial-addition task: a measure of recovery from concussion. Percept Mot Skills. 1977;44(2):367–73. doi: 10.2466/pms.1977.44.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper C, Matsumoto I, Pfefferbaum A, Adalsteinsson E, Sullivan E, Lewohl J, Dodd P, Taylor M, Fein G, Landman B. The Pathophysiology of ‘Brain Shrinkage’ in Alcoholics - Structural and Molecular Changes and Clinical Implications. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(6):1106–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway JMS. MMPI-2: Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. The University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Klove H. Clinical neuropsychology. In: Forster FM, editor. The Medical Clinics of North America. Saunders; New York, NY: 1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann RE, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Pavan D. Reliability of a family tree questionnaire for assessing family history of alcohol problems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1985;15(1–2):61–7. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(85)90030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazas CA, Finn PR, Steinmetz JE. Decision-making biases, antisocial personality, and early-onset alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(7):1036–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterrieth PA. Le test de copie d’une figure complex. Archives de Psychologie. 1944;30:206–356. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Discounting of delayed rewards in substance abusers: relationship to antisocial personality disorder. Psychopharmacology. 2002;162(4):425–32. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1115-1. Berl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Bickel WK, Arnett M. Shortened time horizons and insensitivity to future consequences in heroin addicts. Addiction. 1998;93(5):729–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9357298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell DH, Kaplan EF, Whitla D, Weinstraub S, Catlin R, Funkenstein HH. MicroCog Assessment of Cognitive Functioning. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen L, Pitkanen T. A prospective study of the precursors to problem drinking in young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55(5):578–87. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. Neuropsychology Press; Tucson: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler L, Buckholz K, Compton W. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. Washington University School of Medicine; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18(3):247–91. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, Johnston LD. Getting drunk and growing up: trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57(3):289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gotham HJ. Pathological alcohol involvement: a developmental disorder of young adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11(4):933–56. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Sheu WJ. Reliability of alcohol use indices: The lifetime drinking history and the MAST. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1982;43(11):1157–1170. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. The symbol digit modalities test: A neuropsychological test of learning and other cerebral disorders. In: Helmuth J, editor. Learning Disorders. Special Child Publications; Seattle, WA: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Self-reports issues in alcohol abuse: State of the art and future directions. Behavioral Assessment. 1990;12:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Riley DM, Schuller R, Pavan DS, Cancilla A, Klajner F, Leo GI. The reliability of alcohol abusers’ self-reports of drinking and life events that occurred in the distant past. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1988;49(3):225–232. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. SPSS 13.0 for Windows. 13. SPSS Inc; Chicago IL: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenberg SF, Mudd SA, Blow FC, Hill EM. Evaluating measures of family history of alcoholism: density versus dichotomy. Addiction. 1998;93(10):1511–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931015117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout JC, Rock SL, Campbell MC, Busemeyer JR, Finn PR. Psychological processes underlying risky decisions in drug abusers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(2):148–57. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. The Psychological Corporation; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel L. Development of a short, booklet form of the category test: Correlational and validity data. University of Health Sciences/The Chicago Medical School; Chicago: 1982. [Google Scholar]